Abstract

Zinc and its alloys have been regarded as an alternative option for biodegradable implant materials to magnesium and iron-based alloys due to their promising degradation rate. However, poor osseointegration with bone tissue limits their further clinical application. Considering the biofunction of strontium (Sr), namely promoting the formation of bone tissue, in this work, a ZnO-Sr composite coating was prepared on pure Zn via anodic oxidation to boost bioactivity. Surface morphology and composition of the layer were examined via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD). Electrochemical measurements were carried out to assess the corrosion behaviour. Long-term immersion tests in simulated body fluid (SBF) for up to 21 days were conducted to evaluate the in vitro bioactivity. Corrosion morphology and corrosion products were studied to reveal the corrosion mechanism. The results demonstrated that the Sr-ZnO coating optimized the corrosion rate and enhanced the bioactivity of the substrate, improving its potential for orthopedic applications.

1. Introduction

An ideal biodegradable metallic material is expected to offer adequate mechanical support throughout the tissue healing process [1,2,3]. It should be gradually absorbed in the physiological environment and completely degrade without leaving any residue [4]. In the realm of orthopedic applications requiring temporary implantation (for the time of healing), the implantation of biodegradable metallic materials can effectively circumvent the physical harm and economic burden imposed by secondary surgeries necessary for the removal of the implant when using high corrosion-resistant alloys [5]. In prior investigations, magnesium-based and iron-based biodegradable alloys have garnered substantial attention owing to their outstanding mechanical properties and biodegradability [6,7]. Nevertheless, through successive experiments, it has been revealed that the degradation rates and biocompatibilities of these two types of alloys require further optimization [8,9]. In comparison to magnesium-based and iron-based alloys, zinc and its alloys exhibit a more appropriate degradation rate, favourable biocompatibility, and the capacity to promote the regeneration of injured tissues [10,11]. As a result, they have emerged as an alternative to biodegradable metals. Zinc assumes a crucial role in bone growth, and mineralisation and can inhibit osteoclast resorption. Consequently, zinc and its alloys are anticipated to emerge as an alternative biodegradable metallic material for bone implants [12,13,14].

The surface characteristics of medical materials play a vital role in biocompatibility during the service process [3,15]. Nevertheless, metallic materials typically show inadequate biocompatibility with bone tissue. Although Zn is an essential trace element in cells and tissues and plays a critical role in metabolic processes, the released Zn2+ exhibits a biphasic effect on cytotoxicity: a low concentration enhances cell viability, and a high concentration shows the opposite effect [16,17,18].

Surface modification is the most effective approach to endow metallic materials with surface biological multifunctionality [19]. Anodic oxidation (anodization) is a straightforward technique for fabricating metallic oxide coatings on the metal surface [20]. Zinc oxide is the primary product of zinc anodic oxidation. Previous investigations have demonstrated that zinc oxide exhibits certain antibacterial properties and exerts a positive influence on bone conduction and bone tissue regeneration [21,22]. Li et al. prepared a strontium-enhanced calcium phosphate coating on the surface of a Zn alloy via hydrothermal treatment; this coating promoted degradation behaviour, biomineralisation capabilities, and cytocompatibility [23]. Huang et al. fabricated a strontium-doped hydroxyapatite coating on zinc to optimize its corrosion behaviour and biological compatibility via electrodeposition. The coating reduced the release of Zn ions and enhanced preosteoblasts (MC3T3-E1) cells differentiation; in addition, the coating showed favourable antibacterial effects [24]. Yücel et al. prepared Sr and Zn co-doped 45S5 bioglass; Sr and Zn improved the bioactivity and cytocompatibility of bioglass and showed potential advantages in orthopedic applications [25].

In this work, ZnO-Sr coatings with different Sr-contents were prepared on pure Zn via anodic oxidation. The surface morphology and composition of the coatings were systematically evaluated; moreover, electrochemical measurements and immersion tests were carried out to study the degradation behaviour of the coated samples. To the best of our knowledge, ZnO-Sr coatings formed by anodization on the surface of Zn have not been previously reported. The aim of this study, hence, is to explore the anodization route for the fabrication of such coatings and to study the effect of the Sr-ZnO composite coating on the corrosion rate and bioactivity of pure zinc.

2. Materials and Characterization

2.1. Materials and Anodic Oxidation

A pure zinc (99.99%) sheet with a thickness of 5 mm was used as a substrate and cut into a size of 15 × 15 mm2. The samples were polished with #2000 carborundum sandpaper to remove the oxide layer and then were ultrasonically cleaned with alcohol and dried in a hot air flow. Anodization was carried out in an O-ring cell at room temperature with an electrolyte consisting of sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 0.5M) and strontium acetate (Sr(C2H3O2)2) at different concentrations (0 g/L, 0.1 g/L, 0.3 g/L, and 0.6 g/L). Platinum foil and pure zinc were utilized as the cathode and anode, respectively. The oxidation voltage and time were set to 7 V and 15 min. These anodization conditions were selected after a screening of different voltages. Lower voltages led to incomplete coverage of the surface by the anodic layer, whereas microcracks were observed in the oxide layers formed at higher voltages. Therefore, 7 V represents the optimized voltage for anodization of this system. Subsequently, the specimens were cleaned with ultrapure water and alcohol three times. Finally, the samples were annealed in an oven at 350 °C for 2 h to remove the water.

2.2. Coating Characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi, SU8600, Chiyoda City, Japan) was utilized to reveal the surface morphology, and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) was carried out to determine the elemental composition. X-ray diffraction (Shimadzu, XRD-6000, Kyoto, Japan) was employed to examine the phase composition of the as-prepared samples. The scanning rate and the range were 5°/min and 20–80°, respectively. The surface chemical composition was analyzed with X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Scientific Nexsa, Waltham, MA, USA) via XPS survey spectra and high-resolution XPS spectra.

2.3. Electrochemical Corrosion Tests

Electrochemical measurements were carried out in simulated body fluid (SBF) at room temperature with an electrochemical workstation (PGSTAT302N, Auto-lab, Oss, The Netherlands). Table 1 shows the composition of SBF used in this work. The three-electrode system consisted of a platinum (Pt) foil as the counter electrode (CE), pure zinc and coated samples as the working electrodes (WEs), and Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl, saturated KCl) as the reference electrode (RE). Open circuit potential (OCP) was first measured for 15 min to stabilize the test system. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was conducted with a +/−10 mV perturbation in the frequency range of 10−1 to 105 Hz. Potentiodynamic polarization tests were performed from −400 mV vs. OCP to 800 mV vs. OCP with a scan rate of 1 mV/s.

Table 1.

The composition of SBF.

2.4. Immersion Tests

Immersion tests were carried out in SBF according to ISO23317 in an incubator at a temperature of 37 ± 0.5 °C [26]. The ratio of solution volume to sample surface area (V/A) was 50 mL/cm2 [27]. The medium was refreshed every 24 h. The immersion period lasted up to 21 days. After removal from solution, the samples were thoroughly rinsed with ultrapure water and then dried with a hot air stream. SEM, EDS, XRD, and XPS were conducted to characterize the surface morphology and corrosion products.

3. Results

3.1. Surface Morphology and Chemical Composition of Coating

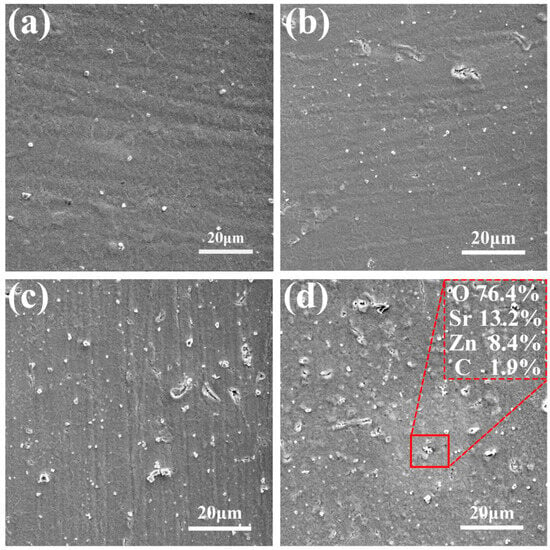

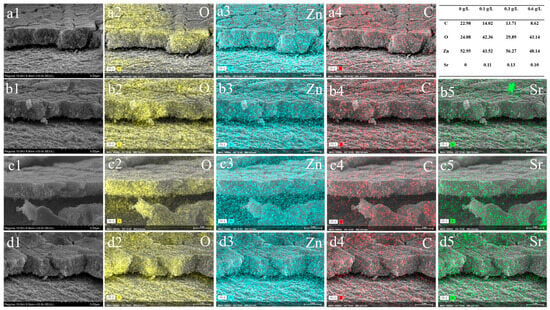

The SEM images and the EDS of samples with different concentrations of Sr(C2H3O2)2, shown in Figure 1, indicate a relatively smooth surface morphology of the anodically formed ZnO coating, with fine particles distributed on the surface. With the addition of the Sr precursor to the anodizing electrolyte, more particles were present on the surface, which also showed some aggregation. Simultaneously, more cracks and micro-pores were observed on the surface. The EDS presented in Figure 1d indicates that the coating consisted of C, Zn, Sr, and O. The coating was cut to expose the inner structure. Figure 2 shows the cross-section SEM image and the EDS mapping data of all samples. The thickness for both ZnO and ZnO-Sr coating was ca. 2 μm. The addition of strontium did not significantly alter the thickness of the coating. Cracks were observed on the surface. The coating exhibited a porous structure. The EDS data show that the coating consists of O, Zn, C, and Sr. Furthermore, strontium is uniformly distributed in the coating.

Figure 1.

SEM images of the Zn samples at 7 V in NaOH with increasing Sr content in the electrolyte: (a) 0 g/L, (b) 0.1 g/L, (c) 0.3 g/L, (d) 0.6 g/L, including EDS data.

Figure 2.

Cross-section SEM images and EDS mapping for oxygen, zinc, and carbon with different concentrations of Sr in the electrolyte: (a1–a4) 0 g/L, (b1–b5) 0.1 g/L, (c1–c5) 0.3 g/L, (d1–d5) 0.6 g/L.

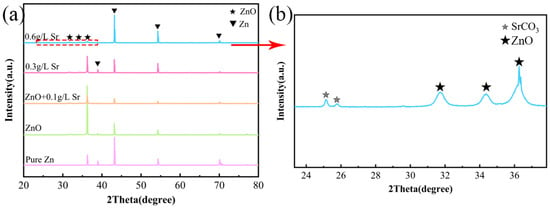

To reveal more information about the phase composition of the coating, XRD was carried out to analyze the crystal structure. Figure 3 shows the XRD patterns of pure Zn and the anodized samples with different concentrations of Sr in the electrolyte. Strong intensity peaks for pure Zn are indexed to zinc (JCPDS:04-0831). For the sample after the anodization process, the weak peaks detected at around 32° and 34.5° can be indexed to ZnO (JCPDS 36-1451) [20]. Moreover, the diffraction peaks detected at 25.2° and 25.8° can be indexed to the strontianite structure SrCO3 (JCPDS 05-0418). It has been frequently reported that ZnO is the main product of Zn anodization [28,29,30], which is consistent with this work. In the anodic region, it corresponds to the oxidation of Zn (Reaction (1)) and OH− in the alkaline environment (Reaction (2)). In our study, Sr(C2H3O2)2 was selected as a precursor; it forms Sr(OH)2(s) in sodium hydroxide solution (Reaction (3)). Small particles of Sr(OH)2 were embedded in/on the ZnO coating during the anodization process. Sr(OH)2 reacts with carbon dioxide in the air, thereby being converted into strontium carbonate (Reaction (4)).

Zn + 2OH− → ZnO + 2H2O + 2e−

2OH− → 1/2 O2 + H2O + 2e−

Sr(C2H3O2)2 + 2NaOH → Sr(OH)2(s) + 2CH3COONa

2Sr(OH)2 + CO2 → Sr2CO3 + 2H2O

Figure 3.

XRD patterns for: (a) pure Zn, ZnO, and ZnO with different Sr contents (0.1 g/L, 0.3 g/L, 0.6 g/L), (b) the magnified partial view of ZnO + 0.6 g/L Sr.

3.2. Electrochemical Measurements: Degradation Behaviour

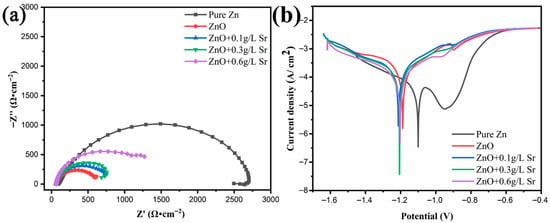

Figure 4 shows the results of the electrochemical measurements for both pure Zn and the anodized samples with different concentrations of Sr precursor in the electrolyte. The EIS Nyquist plots (Figure 4a) demonstrate the lowest degradation rate for pure zinc. Somewhat surprisingly at first glance, anodization leads to the acceleration of corrosion compared with the Zn substrate. It is possible that upon open-circuit exposure of Zn in the electrolyte, protective corrosion products are formed on the Zn surface that are not present for the anodized samples. The anodized layer is possibly less protective than the corrosion product layers due to the presence of microcracks. These findings are in agreement with earlier studies by Liu et al. [31] and Zheng et al. [32] on ZnO coatings fabricated via the microarc oxidation process on Zn; the results demonstrate that coatings increase the corrosion rate compared with the substrate. With the addition of Sr, the semi-circle radius somewhat increased, indicating enhanced corrosion resistance. The ZnO-Sr composite coating, however, shows a limited protective effect. Due to the solubility of Sr(OH)2, considering the risk of forming cracks and pores, a higher concentration of Sr precursor was not further studied.

Figure 4.

Electrochemical measurements of pure Zn, ZnO-coated, and ZnO-Sr-coated samples in SBF: (a) EIS Nyquist plots, (b) polarization curves.

Figure 4b shows the potentiodynamic polarization curves of all the samples; a passivation zone, presented as a decrease in the current density, was observed in the anodic branch for pure zinc. Both ZnO and ZnO-Sr coatings restrain the formation of this protective layer. Table 2 summarizes the corrosion potential, corrosion current density, and corrosion rate determined from Figure 4b via Tafel extrapolation. The corrosion current density increased after anodization treatment as compared with pure zinc. Table 2 also includes corrosion rates as mm/year, calculated from the corrosion current densities under the assumptions that the corrosion rate would remain constant with time and that dissolution would be uniform over the surface; therefore, the values should be considered with care and not taken as absolute values. In terms of corrosion rate, ZnO coating enhanced the degradation process; nevertheless, with the addition of Sr precursor in the anodization electrolyte, the corrosion rate again decreased to some extent. According to the specific design constraints for biodegradable orthopedic fixation devices, the benchmark for corrosion rate has been considered to be 0.5 mm year−1 [33]; moreover, Bowen et al. found that pure zinc remained ca. 70% integrity after 4 months of animal testing [34]. Bone healing time is much shorter than this; for instance, the distal radius fracture healing time is 3–4 weeks [4]; thus, it may be necessary to accelerate the degradation rate of zinc in bone fixation device applications. According to our results, the ZnO-Sr coating enhanced the corrosion process of pure Zn in the physiological environment.

Table 2.

Corrosion rates of different Sr amounts.

3.3. Immersion Tests

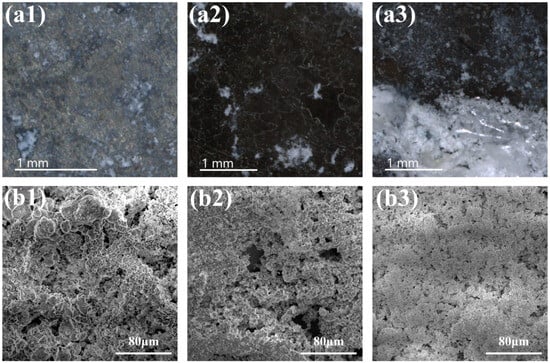

In order to investigate the precipitation ability of Ca-phosphate, immersion tests were carried out in SBF at different intervals. Pure zinc, the anodization sample, and the Sr composite sample (0.6 g L−1) were immersed for up to 21 days at 37 °C in the incubator. Figure 5 shows the surface morphology after immersion for 3 days. The surface was partially corroded, and white precipitates or corrosion products were distributed alongside the corrosion zone. For the ZnO-coated sample, a uniformly distributed white precipitation was also observed on the surface. Interestingly, more white precipitation was detected on the surface of the Sr-containing sample. Figure 5(b1)–(b3) shows the high-magnification SEM images of precipitation from each sample. The Sr-containing sample shows a compact layer morphology.

Figure 5.

Surface morphology after a 3-day immersion test: (a1,b1) pure Zn, (a2,b2) ZnO, (a3,b3) ZnO-Sr-0.6 g/L.

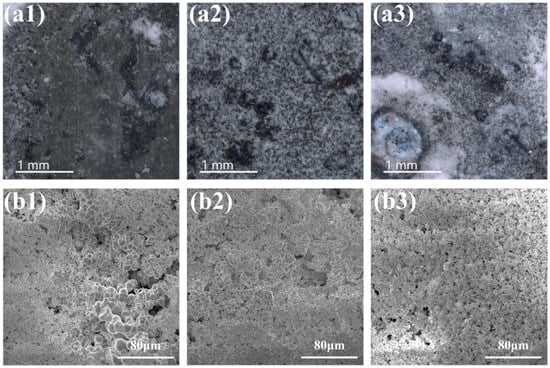

Figure 6 presents the surface morphology after immersion for 21 days. More corrosion and precipitations were observed for pure zinc as compared with 3 days of immersion. Meanwhile, the anodized sample was fully covered with white precipitates, exhibiting better Ca-phosphate precipitation ability than pure zinc. It should be noted that the Sr-containing sample was fully covered by precipitations and also formed a flocculent layer on the top. Table 3 shows the EDS data for each sample group after immersion for different intervals. It is obvious that with the prolongation of the immersion period, more Ca-phosphate was detected for sample groups. With the same soaking time, more calcium phosphate was observed on the Sr-containing sample surface, confirming it had the best Ca-phosphate precipitation ability among the samples.

Figure 6.

Surface morphology after a 21-day immersion test: (a1,b1) pure Zn, (a2,b2) ZnO, (a3,b3) ZnO-Sr.

Table 3.

EDS element contents in different samples for different soaking days.

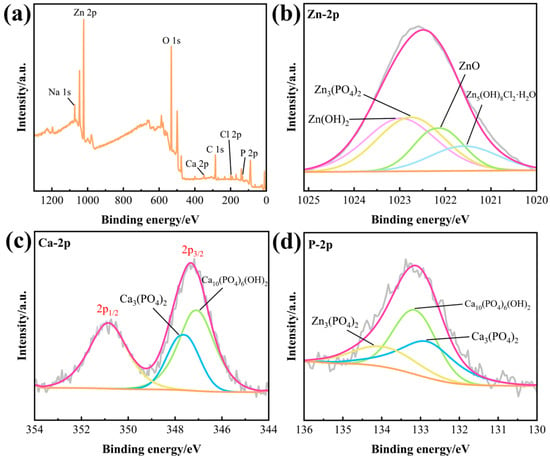

XPS tests were conducted to study the composition of degradation products. Figure 7a depicts the XPS survey spectra of the Sr-containing sample after a 21-day immersion test. The signals for C, O, Cl, P, Na, Zn, and Ca were present after the immersion test. Figure 7b–d shows the high-resolution XPS spectra of zinc, calcium, and phosphate. The Zn2p spectrum from 1025 eV to 1020 eV was fitted with Zn(OH)2 at 1022.8 eV, Zn3(PO4)2, at 1022.5 eV, Zn5(OH)8Cl2·H2O at 1021.8 eV, and ZnO at 1022 eV [6,13]. The signal of Ca2p can be deconvoluted to Ca3(PO4)2 at 347.6 eV and Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2 at 347.1 eV [35]. The P2p spectrum from 136 eV to 130 eV corresponds to Zn3(PO4)2 at 133.9 eV, Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2 at 133.2 eV, and Ca3(PO4)2 at 132.9 eV [36,37].

Figure 7.

XPS survey spectra after a 21-day immersion test (a) and high resolution XPS spectra for Zn2p (b), Ca2p (c), and P2p (d).

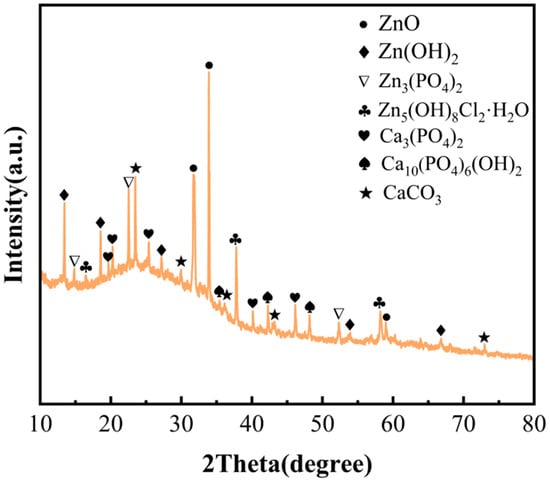

XRD measurements were employed to further study the phase composition of corrosion products and precipitation. Figure 8 shows the XRD spectra of the Sr-containing sample after immersion for 21 days. The corrosion products were collected from the sample and dried before measurement. The phase composition included, CaCO3, Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2, Ca3(PO4)2, Zn3(PO4)2, Zn5(OH)8Cl2∙H2O, Zn(OH)2, and ZnO.

Figure 8.

XRD patterns of the Sr-containing sample.

4. Discussion

SBF was developed to evaluate the apatite-forming ability on the surface of the sample [38]. It has the same concentration of inorganic ions as the physiological environment, which is buffered by the HCl/Tris system. The function of SBF has been disputed by many articles, but it remains the fundamental method for assessing the biological activity of bone implant materials. SBF is a supersaturated system, which becomes thermodynamically stable via precipitating apatite. With the formation of critical-size nuclei and growth of the crystal, the sample provides a surface with a low interfacial energy, and apatite forms on the surface. In this work, ZnO and Sr-doped coating provided more nucleation sites for precipitation; it is noteworthy that the Sr-doped sample showed superior nucleation ability (Figure 5 and Figure 6). In the later stage of the immersion test, calcium-phosphate is converted into a thermodynamically more stable phase—hydroxyapatite—in an alkaline environment after a long-term immersion period in SBF [39].

According to the above results, the corrosion of pure zinc in SBF can be described as follows: initially, Zn is dissolved (Reaction (5)), while oxygen reduction reaction occurs as a cathodic reaction (Reaction (6)) [40]. The pH increases with the generation of OH−, Zn2+ transforms into Zn(OH)2 (as a precipitation in the solution) (Reaction (7)), and Zn(OH)2 partially dehydrates and forms ZnO (Reaction (8)) [35]. Moreover, anodization treatment also forms ZnO on the surface. With the elongation of the soaking period, low solubility products deposit on the surface (Reactions (9) and (10)). The ZnO and Sr-containing coating provided more nucleation sites for precipitation; it is noteworthy that the Sr-containing sample showed superior nucleation ability. Simultaneously, the presence of Cl− facilitates the formation of Zn5(OH)8Cl2 (Reaction (11)) [41]. However, CaCO3 is not detected in the high-resolution XPS spectra. This may be due to the high surface sensitivity of XPS; CaCO3 is not present on the uppermost surface of corrosion products. In the final stage, calcium-phosphate is converted into a thermodynamically more stable phase—hydroxyapatite—in an alkaline environment after a long-term immersion period in SBF [39].

Zn → Zn2+ + 2e−

O2 + H2O + 4e− → 4OH−

Zn2+ + 2OH− → Zn(OH)2

Zn(OH)2 → ZnO + H2O

3Zn2+ + 2PO43− → Zn3(PO4)2

3Ca2+ + 2PO43− → Ca3(PO4)2

5Zn2+ + 2Cl− + 9H2O → Zn5(OH)8Cl2∙H2O+ 8H+

5. Conclusions

In this work, the ZnO and Sr-containing coating was fabricated on pure zinc by anodic oxidation. The thickness of the as-prepared coating was ca. 2 μm. Sr is present in the coating as strontium carbonate. According to electrochemical measurements, the corrosion rate for the pure zinc, anodization sample, and ZnO-Sr (0.6 g/L) was 0.21 mm/a, 0.83 mm/a, and 0.38 mm/a, respectively. The anodization coatings increased the corrosion rate of Zn (possibly by preventing the formation of a well-protecting corrosion product layer). The addition of Sr improved the corrosion resistance of the anodization sample to some extent. This shows potential for optimizing the degradation rate, for instance, in short-term bone fixation devices. Long-term immersion tests in SBF demonstrated that the Sr-containing coating showed superior Ca-phosphate precipitation ability, which provides an alternative option for surface modification of zinc-based alloys.

Author Contributions

H.D.: writing the original draft, J.Z., J.S. and S.H., investigation, data curation, X.Z., resources, review and editing, S.V.: Methodology, Visualization, writing, review, and editing, Y.W.: review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by Jiangsu University of Science and Technology (Grant No. 1062932214). and Jiangsu Provincial Department of Science and Technology (Grant No. BY20240675).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data cannot be shared as the data also forms part of an ongoing study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Hongzhou Dong was employed by the company Postdoctoral Research Station, Jiangsu Jinling Special Coatings Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Virtanen, S. Biodegradable Mg and Mg Alloys: Corrosion and Biocompatibility. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2011, 176, 1600–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, X.; Wu, Y.; Ju, J.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J.; Hu, Z.; Bai, J.; Xue, F. Recent Progress of Novel Biodegradable Zinc Alloys: From the Perspective of Strengthening and Toughening. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 17, 244–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Xia, D.; Wu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Guan, Z.; Rau, J.V. A Review on Current Research Status of the Surface Modification of Zn-Based Biodegradable Metals. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 7, 192–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Gu, X.N.; Witte, F. Biodegradable Metals. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2014, 77, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Escobar, D.; Champagne, S.; Yilmazer, H.; Dikici, B.; Boehlert, C.J.; Hermawan, H. Current Status and Perspectives of Zinc-Based Absorbable Alloys for Biomedical Applications. Acta Biomater. 2019, 97, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Lin, F.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Virtanen, S. Corrosion Behavior of Biodegradable Metals in Two Different Simulated Physiological Solutions: Comparison of Mg, Zn and Fe. Corros. Sci. 2021, 182, 109278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, D.; Lamaka, S.V.; Gonzalez, J.; Feyerabend, F.; Willumeit-Römer, R.; Zheludkevich, M.L. The Role of Individual Components of Simulated Body Fluid on the Corrosion Behavior of Commercially Pure Mg. Corros. Sci. 2019, 147, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasitha, T.P.; Krishna, N.G.; Anandkumar, B.; Vanithakumari, S.C.; Philip, J. A Comprehensive Review on Anticorrosive/Antifouling Superhydrophobic Coatings: Fabrication, Assessment, Applications, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 324, 103090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, D.; Lamaka, S.V.; Lu, X.; Zheludkevich, M.L. Selecting Medium for Corrosion Testing of Bioabsorbable Magnesium and Other Metals—A Critical Review. Corros. Sci. 2020, 171, 108722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupillo, D.; Di Franco, F.; Iannucci, L.; Grassini, S.; Virtanen, S.; Santamaria, M. Following Zn Corrosion during Long Term Immersion Test in Physiological Solutions to Establish the Potential of Zinc as Biodegradable Prosthetic Material. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 531, 146411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, X.; Huang, T.; Huang, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, G.; Qiao, Y.; Jiang, J.; Ma, A.; et al. Strengthening Zn–Ag alloys with Mg addition. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2025, 32, 2641–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojtěch, D.; Kubásek, J.; Šerák, J.; Novák, P. Mechanical and Corrosion Properties of Newly Developed Biodegradable Zn-Based Alloys for Bone Fixation. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 3515–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Virtanen, S. Influence of Bovine Serum Albumin on Biodegradation Behavior of Pure Zn. J. Biomed. Mater. Res.—Part B Appl. Biomater. 2022, 110, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhuo, X.; Qiao, Y. Ultrafine-grained Zn-Mn-Mg alloy with ultrahigh strength obtained through room temperature equal channel angular pressing. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1049, 185370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Xue, Z.; Li, P.; Yang, S.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, S.; Guan, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.N. Surface Modification on Biodegradable Zinc Alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 3670–3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Cockerill, I.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Chang, L.; Zheng, Y. Zinc-Based Biomaterials for Regeneration and Therapy. Trends Biotechnol. 2018, 37, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Zhu, D. Endothelial Cellular Responses to Biodegradable Metal Zinc. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2015, 1, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockerill, I.; Su, Y.; Sinha, S.; Qin, Y.X.; Zheng, Y.; Young, M.L.; Zhu, D. Porous Zinc Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications: A Novel Additive Manufacturing and Casting Approach. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 110, 110738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.S.; Loffredo, S.; Jun, I.; Edwards, J.; Kim, Y.C.; Seok, H.K.; Witte, F.; Mantovani, D.; Glyn-Jones, S. Current Status and Outlook on the Clinical Translation of Biodegradable Metals. Mater. Today 2019, 23, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhou, J.; Virtanen, S. Fabrication of ZnO Nanotube Layer on Zn and Evaluation of Corrosion Behavior and Bioactivity in View of Biodegradable Applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 494, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felice, B.; Sánchez, M.A.; Socci, M.C.; Sappia, L.D.; Gómez, M.I.; Cruz, M.K.; Felice, C.J.; Martí, M.; Pividori, M.I.; Rodríguez, A.P.; et al. Controlled Degradability of PCL-ZnO Nanofibrous Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering and Their Antibacterial Activity. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 93, 724–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roknian, M.; Fattah-alhosseini, A.; Omid, S. Study of the Effect of ZnO Nanoparticles Addition to PEO Coatings on Pure Titanium Substrate: Microstructural Analysis, Antibacterial Effect and Corrosion Behavior of Coatings in Ringer’s Physiological Solution. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 740, 330–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, X.; Qin, X. Enhancing Zinc Alloy Performance with Strontium-Doped Calcium Phosphate Coating for Orthopedic Implants. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 724, 137467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Jia, F.; Bian, A.; Wang, K.; Xie, L.; Yan, K.; Qiao, H.; Lin, H.; et al. Electrodeposited Dopamine/Strontium-Doped Hydroxyapatite Composite Coating on Pure Zinc for Anti-Corrosion, Antimicrobial and Osteogenesis. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 129, 112387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özel, C.; Çevlik, C.B.; Özarslan, A.C.; Emir, C.; Elalmis, Y.B.; Yücel, S. Evaluation of Biocomposite Putty with Strontium and Zinc Co-Doped 45S5 Bioactive Glass and Sodium Hyaluronate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.N.; Su, Y.; Lu, X.; Kuo, P.H.; Du, J.; Zhu, D. Bioactive Glass Coatings on Metallic Implants for Biomedical Applications. Bioact. Mater. 2019, 4, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, D.; Wang, C.; Lamaka, S.V.; Zheludkevich, M.L. Clarifying the Influence of Albumin on the Initial Stages of Magnesium Corrosion in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillory, R.J.; Sikora-Jasinska, M.; Drelich, J.W.; Goldman, J. In Vitro Corrosion and in Vivo Response to Zinc Implants with Electropolished and Anodized Surfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 19884–19893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhyar, M.; Kiat, C.; Adnan, R.; Amirrul, M. Preparation and Characterization of Zinc Oxide Nanoflakes Using Anodization Method and Their Photodegradation Activity on Methylene Blue. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 86, 2041–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Liu, Z.; Dong, J.; Ariyanti, D.; Niu, Z.; Huang, S.; Zhang, W.; Gao, W. Self-Organized ZnO Nanorods Prepared by Anodization of Zinc in NaOH Electrolyte. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 72968–72974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Sun, W.; Shen, J.; Lu, T.; Song, Z.; Liu, H. Corrosion and Biocompatibility of Pure Zn with a Micro-Arc-Oxidized Layer Coated with Calcium Phosphate. Coatings 2021, 11, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Li, B.; Chen, D.; Zhu, D.; Han, Y.; Zheng, Y. Formation Mechanism, Corrosion Behavior, and Cytocompatibility of Microarc Oxidation Coating on Absorbable High-Purity Zinc. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venezuela, J.; Dargusch, M.S. The Influence of Alloying and Fabrication Techniques on the Mechanical Properties, Biodegradability and Biocompatibility of Zinc: A Comprehensive Review. Acta Biomater. 2019, 87, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, P.K.; Guillory, R.J.; Shearier, E.R.; Seitz, J.M.; Drelich, J.; Bocks, M.; Zhao, F.; Goldman, J. Metallic Zinc Exhibits Optimal Biocompatibility for Bioabsorbable Endovascular Stents. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 56, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wu, W.; Su, Y.; Qiao, L.; Yan, Y. Insight into the Corrosion Behaviour and Degradation Mechanism of Pure Zinc in Simulated Body Fluid. Corros. Sci. 2021, 178, 109071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, D.; Dong, C.; Yan, Y.; Volinsky, A.A.; Wang, L.N. Initial Formation of Corrosion Products on Pure Zinc in Saline Solution. Bioact. Mater. 2019, 4, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Meng, Y.; Volinsky, A.A.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L. Influences of Albumin on in Vitro Corrosion of Pure Zn in Artificial Plasma. Corros. Sci. 2019, 153, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokubo, T.; Takadama, H. How Useful Is SBF in Predicting in Vivo Bone Bioactivity? Biomaterials 2006, 27, 2907–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamesh, M.I.; Wu, G.; Zhao, Y.; McKenzie, D.R.; Bilek, M.M.M.; Chu, P.K. Electrochemical Corrosion Behavior of Biodegradable Mg-Y-RE and Mg-Zn-Zr Alloys in Ringer’s Solution and Simulated Body Fluid. Corros. Sci. 2015, 91, 160–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Meng, Y.; Dong, C.; Yan, Y.; Volinsky, A.A.; Wang, L. Initial Formation of Corrosion Products on Pure Zinc in Simulated Body Fluid. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 2271–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Maitz, M.F.; Chen, M.; Zhang, H.; Mao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, N.; Wan, G. Comparative Corrosion Behavior of Zn with Fe and Mg in the Course of Immersion Degradation in Phosphate Buffered Saline. Corros. Sci. 2016, 111, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.