Study on Mechanical Performance and Enhancement Effect of Steel-Polypropylene Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Concrete

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Raw Materials

2.2. Mixing Ratio

2.3. Specimen Design and Production

2.4. Test Methods

3. Results

3.1. Failure Process and Failure Mode

3.1.1. Compression

3.1.2. Splitting Tension

3.2. Analysis of Compressive Strength and Influencing Factors

3.3. Analysis of Splitting Tensile Strength and Its Influencing Factors

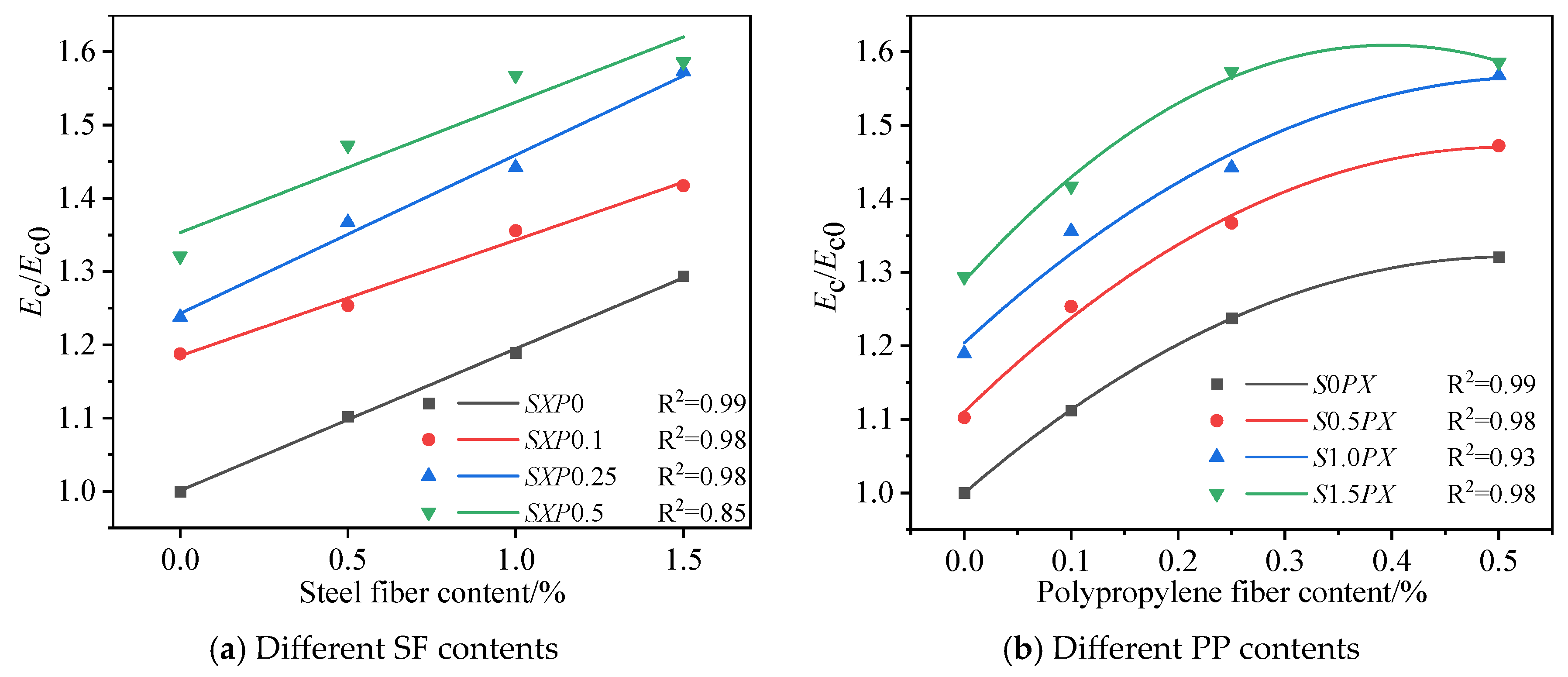

3.4. Elastic Modulus

3.5. Poisson’s Ratio

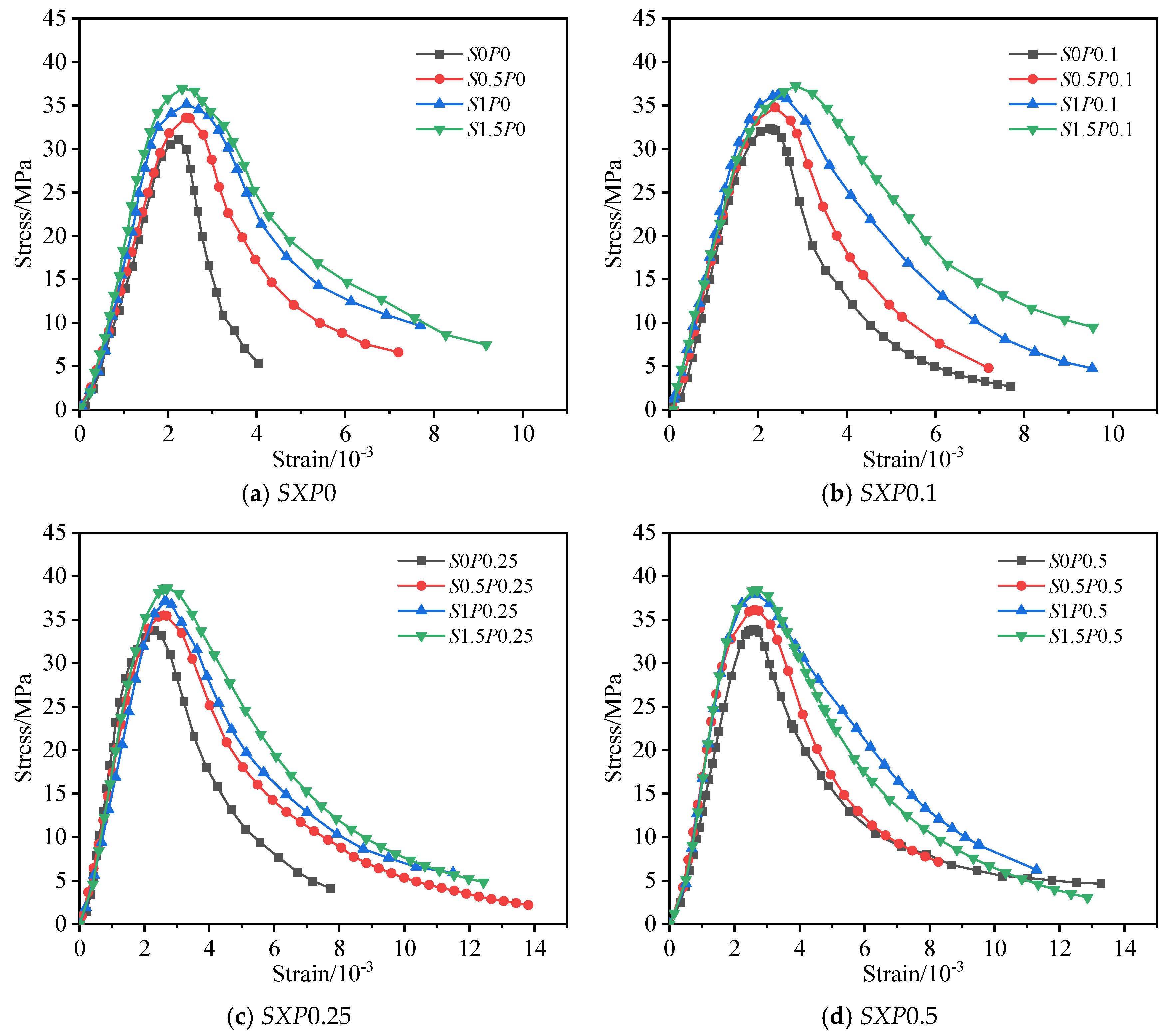

3.6. Stress–Strain Curve of the Whole Process

4. Discussion

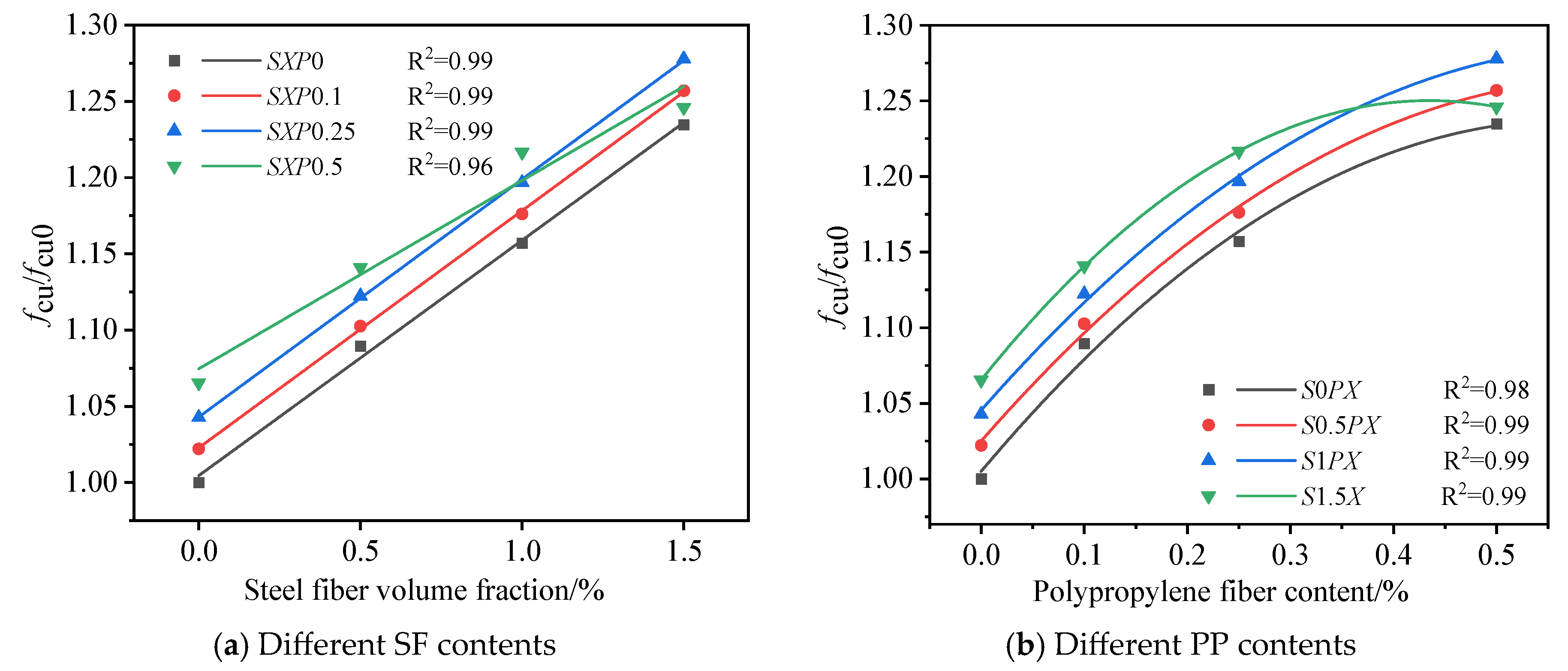

4.1. The Dependency of Compressive Strength on Fiber Content

4.2. The Correlation Between Fiber Content and Splitting Tensile Strength

4.3. Conversion Relationship of Strength Indices

4.4. The Calculation Equation of Elastic Modulus of SPFRC

4.5. Constitutive Relation Establishment and Universality Verification

4.6. The Enhancement Effect of SPF

4.6.1. The Reinforcing Effect of SPF

4.6.2. Crack Resistance of SPF

4.6.3. Toughening Effect of SPF

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Both single-doped (SF or PP) and hybrid fiber reinforcement significantly alter the failure mode of concrete. Concrete without fiber addition shows typical brittle failure, accompanied by severe specimen damage. In contrast, fiber-reinforced specimens display pronounced plastic deformation behavior and retain structural integrity after failure.

- (2)

- For specimens under single-parameter variation in SF, an SF content of 0.5% leads to the greatest enhancement in concrete’s mechanical performance. For specimens under single-parameter variation in PP, a PP content of 0.1% results in the most pronounced improvement in concrete’s mechanical performance. Moreover, single-doped fiber significantly enhances the elastic modulus of the specimens and concurrently reduces their Poisson’s ratio.

- (3)

- Appropriate hybrid fiber can notably improve the mechanical performance of concrete. When the SF content is 1.5% and the PP content is 0.25%, cube compressive strength, axial compressive strength, and split tensile strength achieve their peak values. When the SF content is 1.5% and the PP content is 0.5%, the elastic modulus experiences the most significant increase, and the Poisson’s ratio shows the most substantial decrease.

- (4)

- For concrete specimens with single-type SF, as the fiber content increases, the gradient of the ascending branch of the stress–strain curve progressively rises. Moreover, the downward section of this curve is gentler than that of plain concrete specimen (S0P0). For concrete specimens with hybrid fiber, PP shows little impact on the slope of the ascending segment, yet it can make the curve’s descending segment more gradual.

- (5)

- By considering the influencing factors of SF and PP, the stress–strain curve equation for SPFRC is developed. Validation shows that the calculated curve agrees well with the experimentally measured curve.

- (6)

- Through the analysis of the effects by which SPFs improve the strengthening, crack-resistance, and toughening of concrete under static loads, the calculation methods for the strengthening, crack-resistance, and toughening effects of SF and PP on concrete specimens are developed.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheng, S.T.; He, H.X.; Cheng, Y.; Sun, H. Flexural behavior of RC beams enhanced with carbon textile and fiber reinforced concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 70, 106454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.L.; Chen, Z.Q.; Wang, M.; Bai, J.; Qin, Z.; Xiao, T.; Meng, N.; Liu, J.; Gai, Y.; Nan, H. Fracture characteristics and fracture interface buckling mechanism of cantilever rock mass under non-uniformly distributed load. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.L.; Ren, W.S.; Chen, Z.Q.; Wang, M.; Bai, J.; Meng, N.; Qin, Z.; Liu, J.; Yao, T.; Gai, Y. Pressure Reduction Effectiveness Evaluation of Entry Under Longwall Mining Disturbance: A Case Study. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, G.M.; Enfedaque, A.; Gálvez, C.J.; Álvarez, C. Using Polyolefin Fibers with Moderate-Strength Concrete Matrix to Improve Ductility. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2019, 31, 04019170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F.Y.; Kazmi, S.M.S.; Hu, B.; Wu, Y.-F. Mitigating the brittle behavior of compression cast concrete using polypropylene fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 440, 137435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, M.; Yan, M.; Jiang, Z. Persistence of Strength/Toughness in Modified-Olefin-Fiber- and Hybrid-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. J. Test. Eval. 2017, 45, 2071–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslani, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. Flexural and toughness properties of NiTi shape memory alloy, polypropylene and steel fibers in self-compacting concrete. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2020, 31, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Zheng, H.B.; Ju, H.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, C.; Jia, J. Early-Age Cracking Resistance of Multiscale Fiber-Reinforced Concrete with Steel Fiber, Sisal Fiber, and Nanofibrillated Cellulose. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 35, 04023065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Ding, Y. Experimental study on the compressive fatigue performance of nano-silica modified recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 447, 138161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, G.F.; Zheng, Y.X. Effect of fiber type on the mechanical properties and durability of hardened concrete. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 16063–16088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.T.; He, H.X.; Lan, B.J. Uniaxial Compression Test and Performance Analysis of Multiscale Modified Concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2024, 36, 13688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumarana, T.; Arachchi, M.; Somarathna, H.; Raman, S. A review on the variation of mechanical properties of carbon fiber-reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 366, 130173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.K.; Rad, M.M. Limited optimal plastic behavior of RC beams strengthened by carbon fiber polymers using reliability-based design. Polymers 2023, 15, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Lu, Z.; Wang, D. Working and mechanical properties of waste glass fiber reinforced self-compacting recycled concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 439, 137172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassew, S.T.; Lubell, A.S. Mechanical properties of glass fiber reinforced ceramic concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 51, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.G.; Niu, J.X.; Xu, P.; Deng, D.; Fan, Y. Investigation on eccentric compression performance of basalt fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete-filled square steel tubular columns. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 18, 100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.G.; Shen, Y.C.; Fan, Y.H.; Gao, X. Experimental study on the triaxial compression mechanical performance of basalt fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete after exposure to high temperature. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Zheng, S.; Huang, L.Z.; Yang, C.; Du, X. Experimental study on the properties of internal cured concrete reinforced with steel fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 393, 132046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.G.; Zhu, Y.N.; Shen, Y.C.; Wang, J.; Fan, Y.; Gao, X.; Huang, Y. Compressive mechanical performance and microscopic mechanism of basalt fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete after elevated temperature exposure. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.G.; Zhu, Y.N.; Fan, Y.H.; Zhou, G.; Huang, Y.; Li, M.; Shen, W. Experimental study on impact resistance and dynamic constitutive relation of steel fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Yang, K.H. Compressive and flexural toughness indices of lightweight aggregate concrete reinforced with micro-steel fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 401, 132965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.G.; Zhu, Y.N.; Wang, J.B.; Zhou, G.; Huang, Y. Analysis of impact crushing characteristics of steel fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete based on fractal theory. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Wu, J.; Wang, J.G. Experimental and numerical analysis on effect of fiber aspect ratio on mechanical properties of SRFC. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 24, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.; Soliman, M.A.; Nehdi, L.M. Exploring mechanical and durability properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating various steel fiber lengths and contents. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 75, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.X.; Zang, S.J.; Yang, F. Synergism of steel fibers and polyvinyl alcohol fibers on the fracture and mechanical properties of ultra-high performance concrete. Mag. Concr. Res. 2024, 76, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Ali, I.; Room, S.; Khan, S.A.; Ali, A. Enhanced mechanical properties of fiber reinforced concrete using closed steel fibers. Mater. Struct. 2019, 52, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, S.; Douba, A.; Abdullahi, O.; Farrag, S. Mechanical and durability evaluation of fiber-reinforced self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 121, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.H.; Hu, G.W.; Zhou, K.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X. Study on early-age cracking resistance of multi-scale polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete in restrained ring tests. J. Sustain. Cem. Based Mater. 2024, 13, 1050–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.H.; You, X.F.; Cao, G.J.; Liu, X.; Zhong, Z. Effect of multi-scale polypropylene fiber hybridization on mechanical properties and microstructure of concrete at elevated temperatures. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2021, 24, 1985–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akid, A.S.M.; Hossain, S.; Munshi, M.I.U.; Elahi, M.M.A.; Sobuz, M.H.R.; Tam, V.W.; Islam, M.S. Assessing the influence of fly ash and polypropylene fiber on fresh, mechanical and durability properties of concrete. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 2023, 35, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.L.; Jia, Y.M.; Wang, J. Experimental study on mechanical and durability properties of glass and polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete. Fibers Polym. 2019, 20, 1900–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, M.R.; Biricik, O.; Aghabaglou, A.M. Effect of the addition of polypropylene fiber on concrete properties. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2021, 36, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneti, S.B.; Wee, T.H.; Thangayah, S.T. Effect of polypropylene fibers on the shrinkage cracking behaviour of lightweight concrete. Mag. Concr. Res. 2011, 63, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherzadeh, R.; Sadeghi, A.; Latifi, M. Utilizing polypropylene fibers to improve physical and mechanical properties of concrete. Text. Res. J. 2012, 82, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.H.; You, X.F.; Yan, R.; Miao, Q.; Liu, X. Experimental investigation on the mechanical properties of polypropylene hybrid fiber-reinforced roller-compacted concrete pavements. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2022, 16, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.K.; Hadi, N.A.; Rad, M.M. Experimental and numerical analysis of ssteel-polypropylene hybrid fibre reinforced concrete deep beams. Polymers 2023, 15, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; He, X.; Wang, H.; Wu, C.; He, J.; Wei, B. Mechanical properties and microstructure of ITZs in steel and polypropylene hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 415, 135119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.M.; Xie, W.; Wan, J.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, C.; Luo, X. Experimental investigation on mechanical properties of steel-polypropylene hybrid fiber engineered cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 426, 136122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroughsabet, V.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Mechanical and durability properties of high-strength concrete containing steel and polypropylene fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 94, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwesabi, E.A.H.; Abu Bakar, B.H.; Alshaikh, I.M.H.; Abadel, A.A.; Alghamdi, H.; Wasim, M. An experimental study of compressive toughness of steel-polypropylene hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete. Structures 2022, 37, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaeian, M.; Khaloo, A.; Joshaghani, A.; Hajibandeh, E. Experimental investigation on effects of hybrid fibers on rheological, mechanical, and durability properties of high-strength SCC. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 147, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.K.; Rai, B. Assessment of synergetic effect on microscopic and mechanical properties of steel-polypropylene hybrid fiber reinforced concrete. Struct. Concr. 2021, 22, 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Tao, J.L.; Chen, Y.; Li, D.; Jia, B.; Zhai, Y. Effect of steel and polypropylene fibers on the quasi-static and dynamic splitting tensile properties of high-strength concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 224, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Chi, Y.; Xu, L.H.; Shi, Y.; Li, C. Experimental investigation on the flexural behavior of steel-polypropylene hybrid fiber reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 191, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.C.; Kong, X.Q.; Fu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zheng, Z. Experimental investigation on the mechanical properties and microstructure of hybrid fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 261, 120488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwesabi, E.A.H.; Abu Bakar, B.H.; Alshaikh, I.M.H.; Akil, H.M. Experimental investigation on mechanical properties of plain and rubberised concretes with steel-polypropylene hybrid fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 233, 117194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslani, F.; Nejadi, S. Self-compacting concrete incorporating steel and polypropylene fibers: Compressive and tensile strengths, moduli of elasticity and rupture, compressive stress-strain curve, and energy dissipated under compression. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 53, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.M.; Du, H.; Liu, Y.H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Wei, Y. Experimental study and mesoscale finite element modeling of elastic modulus and flexural creep of steel fiber-reinforced mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 363, 129875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksawang, N.; Wtaife, S.; Alsabbagh, A. Evaluation of Elastic Modulus of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. Aci Mater. J. 2018, 115, 239–249. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.X.; Lv, X.M.; Hu, S.W.; Zhuo, J.; Wan, C.; Liu, J. Mechanical properties and durability of steel fiber reinforced concrete: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 82, 108025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematzadeh, M.; Hasan-Nattaj, F. Compressive stress-strain model for high-strength concrete reinforced with forta-ferro and steel fibers. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2017, 29, 04017152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.Y.; Liu, X.R.; Yang, X.; Liang, N.; Yan, R.; Chen, P.; Miao, Q.; Xu, Y. A study of tensile and compressive properties of hybrid basalt-polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete under uniaxial loads. Struct. Concr. 2021, 22, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Reinforced Concrete Structure Theory; Construction Industry Press: Beijing, China, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J. Dynamic Constitutive Model and Finite Element Method of Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete. Doctoral Dissertation, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z. Strength and Deformation of Concrete [Experimental Basis and Constitutive Relation]; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Alhozaimy, A.M.; Soroushian, P.; Mirza, F. Mechanical properties of polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete and the effects of Pozzolanic materials. Cem. Concr. Compos. 1996, 18, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Y. Experimental study on hybrid fiber-reinforce concrete subjected to uniaxial compression. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2014, 26, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romualdi, J.P.; Batson, G.B. The mechanics of crack arrest in concrete. Proc. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1963, 89, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiber-Reinforced Concrete; Zou, C., Translator; Railway Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1985. [Google Scholar]

| Fiber Type | Density (g/cm3) | Length (mm) | Diameter (mm) | Breaking Elongation (%) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF | 7.85 | 13 | 0.2 | – | 2965 | 55 | 2.1 |

| PP | 0.91 | 12 | – | 25 | 560 | 5.18 | – |

| Specimen Number | W/B | Sand Ratio/% | Water | Cement | Fly Ash | Coarse Aggregate | Fine Aggregate | Steel Fiber | Polypropylene Fiber | Water Reducer | Slump/mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0P0 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 0 | 0 | 2.13 | 167 |

| S0P0.1 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 0 | 0.91 | 2.13 | 151 |

| S0P0.25 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 0 | 2.28 | 2.13 | 136 |

| S0P0.5 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 0 | 4.55 | 2.13 | 121 |

| S0.5P0 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 39 | 0 | 2.13 | 154 |

| S0.5P0.1 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 39 | 0.91 | 2.13 | 137 |

| S0.5P0.25 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 39 | 2.28 | 2.13 | 121 |

| S0.5P0.5 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 39 | 4.55 | 2.13 | 106 |

| S1P0 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 78 | 0 | 2.13 | 141 |

| S1P0.1 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 78 | 0.91 | 2.13 | 120 |

| S1P0.25 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 78 | 2.28 | 2.13 | 102 |

| S1P0.5 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 78 | 4.55 | 2.13 | 87 |

| S1.5P0 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 117 | 0 | 2.13 | 132 |

| S1.5P0.1 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 117 | 0.91 | 2.13 | 109 |

| S1.5P0.25 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 117 | 2.28 | 2.13 | 91 |

| S1.5P0.5 | 0.47 | 32 | 200 | 355 | 71 | 1206.3 | 567.7 | 117 | 4.55 | 2.13 | 76 |

| Specimen Number | Specimen Number | Specimen Number | Specimen Number | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0P0 | 2.23 | S0.5P0 | 2.26 | S1P0 | 2.31 | S1.5P0 | 2.57 |

| S0P0.1 | 2.4 | S0.5P0.1 | 2.42 | S1P0.1 | 2.59 | S1.5P0.1 | 2.64 |

| S0P0.25 | 2.41 | S0.5P0.25 | 2.45 | S1P0.25 | 2.62 | S1.5P0.25 | 2.67 |

| S0P0.5 | 2.64 | S0.5P0.5 | 2.67 | S1P0.5 | 2.71 | S1.5P0.5 | 2.71 |

| Specimen Number | R1 | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0P0 | 35.27 | 28.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| S0P0.1 | 41.10 | 60.55 | 0.17 | 1.16 |

| S0P0.25 | 46.47 | 79.67 | 0.32 | 1.84 |

| S0P0.5 | 45.36 | 119.87 | 0.29 | 3.27 |

| S0.5P0 | 43.71 | 73.82 | 0.24 | 1.63 |

| S0.5P0.1 | 48.89 | 77.39 | 0.39 | 1.76 |

| S0.5P0.25 | 54.48 | 109.95 | 0.54 | 2.91 |

| S0.5P0.5 | 55.80 | 126.93 | 0.58 | 3.52 |

| S1P0 | 48.09 | 100.37 | 0.36 | 2.57 |

| S1P0.1 | 50.88 | 116.30 | 0.44 | 3.14 |

| S1P0.25 | 53.27 | 136.60 | 0.51 | 3.86 |

| S1P0.5 | 57.93 | 149.26 | 0.64 | 4.31 |

| S1.5P0 | 56.84 | 118.06 | 0.61 | 3.20 |

| S1.5P0.1 | 58.18 | 138.27 | 0.65 | 3.92 |

| S1.5P0.25 | 61.08 | 151.93 | 0.73 | 4.41 |

| S1.5P0.5 | 62.14 | 162.52 | 0.76 | 4.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Huo, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Niu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, S.; Shi, L. Study on Mechanical Performance and Enhancement Effect of Steel-Polypropylene Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. Coatings 2026, 16, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010046

Zhang X, Huo J, Zhang X, Wang J, Niu J, Zhou Q, Zhang S, Shi L. Study on Mechanical Performance and Enhancement Effect of Steel-Polypropylene Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xianggang, Junke Huo, Xuanxuan Zhang, Junbo Wang, Jixiang Niu, Qin Zhou, Shengli Zhang, and Lei Shi. 2026. "Study on Mechanical Performance and Enhancement Effect of Steel-Polypropylene Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Concrete" Coatings 16, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010046

APA StyleZhang, X., Huo, J., Zhang, X., Wang, J., Niu, J., Zhou, Q., Zhang, S., & Shi, L. (2026). Study on Mechanical Performance and Enhancement Effect of Steel-Polypropylene Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. Coatings, 16(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010046