Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A scale inhibitor with 91.26% efficiency was identified through static tests.

- Effects of concentration and temperature on adsorption of inhibitor were unraveled.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- Adsorption behavior was investigated using molecular dynamics simulations.

Abstract

Based on static scale inhibition experiments and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, this study investigated the influence of concentration and temperature on the scale inhibition performance and adsorption behavior of the hydroxyphosphonic acid-based XCN scale inhibitor on calcite (104) surfaces. Experimental results demonstrate that XCN exhibits excellent inhibition efficiency against CaCO3 scale, achieving 91.26% at 30 ppm and 60 °C. Further increasing the concentration to 35 ppm improves the inhibition rate by only 0.52%, a marginal gain attributable to the threshold effect. Performance improves with decreasing temperature, increasing from 91.26% at 60 °C to 96.92% at 30 °C. MD simulations reveal that the adsorption energy between XCN and calcite peaks at a specific molecular count (9 molecules), indicating optimal surface coverage. Radial distribution function analyses confirm chemisorption via Ca-O and Ca-H interactions within 1–3.5 Å, inducing lattice distortion that inhibits crystal growth. However, increasing temperature weakens adsorption and promotes molecular desorption, reducing inhibition efficiency. These findings provide molecular-level insights into the threshold and thermal behaviors of phosphonic acid scale inhibitors, supporting the optimized application of XCN in oilfield operations.

1. Introduction

In oil and gas extraction, scale formation poses a significant threat to operational efficiency and integrity. Moreover, the thermodynamic instability and incompatibility of fluids often lead to scale deposition, which can severely block equipment and pipelines, resulting in substantial economic losses [1]. These scales are primarily composed of carbonates, sulfates, phosphates, and aluminosilicates [2,3,4]. Among operational challenges, scaling is one of the most difficult to manage. Effective scale control relies on a thorough understanding of scale composition, the selection of appropriate inhibitors, and early pretreatment.

Currently, the application of chemical scale inhibitors represents a highly effective and economical method for mitigating scale deposition. Those used in oilfields can be broadly categorized into four types: natural polymers (primarily including lignin, starch, and chitosan), polycarboxylic acids, organophosphorus compounds, and green environmentally friendly scale inhibitors. Natural polymers are characterized by their non-toxicity, ready biodegradability, and ease of recovery [5,6], while carboxylate-based ones achieve scale inhibition by chelating with metal ions such as Ca2+, Ba2+, and Mg2+ through their carboxyl groups [7]. Environmentally friendly scale inhibitors, such as acrylic acid-co-maleic acid and polyaspartic acid, have garnered widespread attention due to their biodegradability and eco-friendly properties, as they can inhibit the nucleation and growth rate of scale crystals [8]. The phosphonic acid groups of organophosphorus acid-based scale inhibitors exhibit advantages such as chemical stability, a wide pH application range, effective inhibition of bacterial and algal proliferation, and synergistic effects with various chemicals [9].

The scale inhibition mechanism of scale inhibitors is not only the key criterion for their screening but also the fundamental logic explaining differences in efficacy across various systems. Commonly used oilfield scale inhibitors primarily function through several mechanisms: dispersion, lattice distortion, complexation–solubilization, the threshold effect, and the regeneration-self-stripping film hypothesis. Dispersion: This mechanism works through the formation of an electrical double layer on micro-crystals by negatively charged ions from the scale inhibitor, which induces electrostatic repulsion to maintain a dispersed state, thus preventing agglomeration and retarding crystal growth [10]. Lattice Distortion: Scale inhibitors disrupt the regular order of crystal growth, leading to misaligned crystal structures. This misalignment increases internal lattice strain and reduces structural density, thereby creating voids and making the crystals porous and fragile [11,12]. These weakened crystals are then easily carried away by the fluid flow. Complexation–Solubilization: This mechanism involves the formation of stable complexes between the ionic groups of the dissolved scale inhibitor and scaling cations (e.g., Ca2+, Mg2+, Ba2+). By sequestering these cations, the inhibitor reduces their encounter frequency with carbonate and sulfate anions, thereby prolonging the induction period and enhancing their apparent solubility. Threshold Effect: For any scale inhibitor in a system, there is a critical concentration threshold [13]. Below this threshold, increasing the inhibitor concentration effectively suppresses crystal nucleation and growth. However, beyond this point, further increases in concentration yield only a minimal improvement, or even a decline, in the scale inhibition rate. Regeneration-Self-Stripping Film Hypothesis: In an aqueous solution, scale inhibitor molecules and metal cations can co-precipitate to form a film on a crystal surface. When this film reaches a certain thickness, it fractures and detaches. This self-stripping process prevents the inhibitor from being permanently incorporated into the scale lattice, thereby allowing it to be “regenerated” to inhibit further scaling.

Among the most widely applied scale inhibitors in oilfields are phosphorus-containing organic compounds and their complexes. These phosphonates are mainly categorized into non-polymeric and polymeric phosphates, which are recognized for their ability to control crystal growth by inducing lattice distortion. Furthermore, they exhibit excellent chemical stability, function effectively over a wide pH range, demonstrate high resistance to hydrolysis, operate via a notable threshold effect, and effectively chelate metal ions to form stable complexes. However, the molecular-level mechanism underlying the influence of concentration and temperature on their adsorption behavior onto calcite (a typical scale-forming mineral) remains insufficiently clarified, particularly regarding the correlation between surface coverage, adsorption energy, and scale inhibition efficiency. Therefore, guided by static scale inhibition experiments, this study selected an effective phosphonic acid scale inhibitor. Given that calcite (CaCO3) is the most prevalent scale-forming mineral in oilfield operations [14,15], MD simulations were subsequently employed to investigate the effects of its concentration and temperature on the adsorption behavior onto a calcite (104) surface.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

All chemicals and reagents used in this study were of analytical grade and purchased from Kelong Reagent Company (Chengdu, China), including sodium chloride, sodium bicarbonate, calcium chloride, magnesium chloride, sodium sulfate, EDTA standard solution, and calcon carboxylic acid indicator.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Scale Inhibition Rate Test

The standard brine was prepared as per SY/T 5673-2020 [16], and its composition is listed in Table 1. A static scale inhibition test was then performed to assess the performance of the four inhibitors in preventing calcium carbonate scale. Each inhibitor was injected at a dosage of 30 ppm, and a blank control was included for comparison.

Table 1.

Composition of standard brine.

We measured out 100 mL of solutions A and B separately using a graduated cylinder and poured each into a 250 mL ground-neck conical flask. Then the flask was fitted with a two-holed stopper equipped with long and short glass tubes for gas inlet and outlet. The long tube was submerged near the flask bottom to ensure a continuous stream of saturated CO2 bubbles passes through the solution. We placed the flask in a constant-temperature water bath at 60 °C. After 30 min of CO2 purging, the flask was tightly sealed and weighed, checking if the weight loss exceeded 0.5 g. A quantity of CO2-saturated solution A was transferred to a new 250 mL conical flask, followed by the addition of 130 mL of distilled water and 2.5 mL of the selected scale inhibitor solution. After standing for 10 min, 50 mL of CO2-saturated solution B was added, and the mixture was diluted to the mark with distilled water. The flask was then tightly sealed, shaken to ensure homogeneity, and weighed. Subsequently, the flask was placed in a constant-temperature water bath set at 60 °C. After 30 min of incubation, the stopper was briefly opened to release pressure and then resealed tightly. The flask was maintained in the water bath at 60 °C for another 18 h. A blank experiment was conducted concurrently under identical conditions but without the addition of the scale inhibitor. After the 16 h incubation period, the conical flask was removed and allowed to cool to room temperature, followed by weighing. If the mass loss exceeded 0.5 g, an appropriate amount of distilled water was added to compensate for the loss. The solution was then filtered through filter paper. A 20 mL aliquot of the filtrate was pipetted into a 50 mL beaker. Subsequently, 10 mL of this solution was transferred via pipette into a 50 mL volumetric flask, which was then filled to the mark with distilled water. The flask was securely stoppered and shaken thoroughly to ensure complete mixing. Finally, a 25 mL aliquot of the treated solution was taken for the determination of calcium ion concentration according to the standard method GB/T 7476 [17]. The scale inhibition efficiency (E) against CaCO3 was then calculated using Equation (1).

In this formula:

E—Scale inhibition rate of CaCO3 scale (%);

M3—EDTA volume consumed for the solution with scale inhibitor added (mL);

M2—EDTA volume consumed for the solution without scale inhibitor added (mL);

M1—One-fifth of the EDTA volume consumed for the standard calcium ion solution (mL).

2.2.2. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are a computational technique based on classical mechanics, quantum mechanics, and statistical mechanics [18,19]. They involve numerically solving the classical equations of motion for molecular systems to generate trajectories, from which the structural characteristics and properties of the systems can be statistically analyzed. In this work, the Amorphous Cell and Forcite modules were employed.

First, all MD simulations were conducted within the Forcite module of Materials Studio under the NVT ensemble, justified as the pressure was non-critical. Initial velocities were generated via the Maxwell–Boltzmann method, and temperature was regulated with the Berendsen thermostat. For non-bonded interactions, the Ewald and Atom-based methods with a 15.5 Å cutoff were used for electrostatic and van der Waals terms, respectively. The system was evolved for 1000 ps (1.0 fs/step), with trajectories recorded every 2000 steps.

Second, the Amorphous Cell module is a tool that employs the Monte Carlo method to construct amorphous models. It can be utilized to build a variety of structures, including polymer blends, solution systems, composites with varying component ratios, and solid–liquid/gas interfaces. The Forcite module is primarily employed for molecular mechanics and molecular dynamics simulations. It supports a wide range of force fields and is applicable to diverse systems. Within this module, the Geometry Optimization task performs molecular mechanics calculations on the constructed models to obtain the minimum energy configuration. The Dynamics task conducts molecular dynamics simulations on the energy-minimized models. Finally, the Energy task computes energy parameters for systems such as solutions and solid surfaces. The adsorption energy of the scale inhibitor system can be determined using Equation (2) based on the output from this task [20,21].

In this formula:

Eads—Adsorption energy of the system (kJ/mol);

Etotal—Total energy in the system (kJ/mol);

Esi—Energy of the compound (kJ/mol);

Esf—Energy of the calcite crystal face (kJ/mol).

The specific procedures of MD simulations are presented as follows:

- 1.

- We drew 3D molecular models of the XCN scale inhibitor and water molecule using ChemDraw, and imported them into Gaussian for structural optimization. Subsequently, we imported the optimized models into Materials Studio and performed further geometry optimization using the Smart algorithm in the Forcite module.

- 2.

- We imported the calcite unit cell from the Materials Studio crystal database (lattice parameters: a = b = 4.99 Å, c = 17.061 Å, α = β = γ = 90°) and cleaved the calcite (104) surface using the Build Surface task. Then, we built a supercell via the Symmetry task in the Build module, with the calcite (104) supercell dimensions of 24.29 Å in length and 14.97 Å in width.

- 3.

- We constructed solution layers of scale inhibitor at varying concentrations using the Amorphous Cell module, with the same length and width as the iron surface model. Each layer contained 1, 3, 6, and 9 XCN scale inhibitor molecules, respectively, along with 500 water molecules. The scale inhibitor molecules were randomly placed using the Monte Carlo method, and structural optimization was performed using the Geometry Optimization task in the Forcite module.

- 4.

- To eliminate solvent effects on the inhibitor’s performance, an anhydrous adsorption model was constructed by representing the aqueous environment with a dielectric constant. A vacuum layer of 20 Å was added above the calcite (104) surface, and the system was geometry-optimized to obtain the lowest-energy configuration.

- 5.

- MD simulations were conducted under the COMPASS II force field.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Screening and Evaluation of Scale Inhibitors

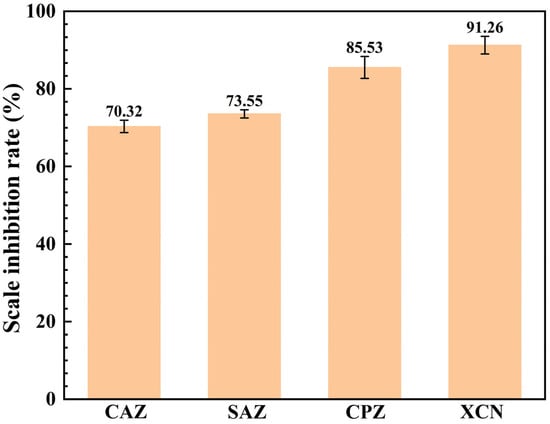

Static scale inhibition experiments were conducted on the four scale inhibitors in accordance with the method described in Section 2.2.1 to evaluate their scale inhibition performance against calcium carbonate. The experiments were carried out by adding the four corrosion inhibitors (30 ppm) separately, with a blank group set as the control. The experimental data are presented in Figure 1. For oilfield scale inhibitors, the performance requirement at 60 °C is a scale inhibition rate of ≥80% [10]. Among the tested scale inhibitors, the carboxylic acid-based CAZ and the ethylenediamine phosphonic acid-based SAZ exhibit relatively poor scale inhibition performance, with their scale inhibition rates both below 85%. In contrast, the aminophosphonic acid-based CPZ and the hydroxyphosphonic acid-based XCN exhibit superior scale inhibition performance, with their scale inhibition rates exceeding 85%. Notably, the scale inhibition rate of the hydroxyphosphonic acid-based XCN reaches as high as 91.26%.

Figure 1.

Scale inhibition rate test results.

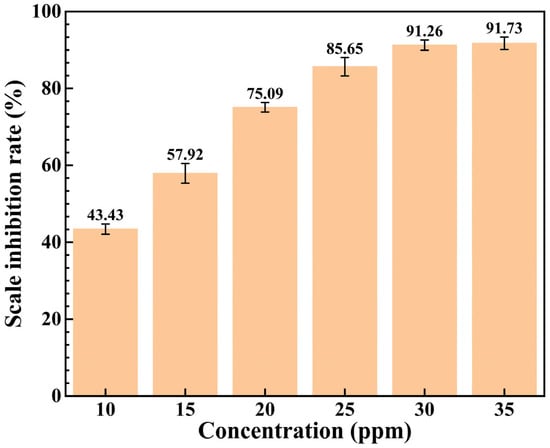

3.2. Effect of Concentration on Scale Inhibition Performance

To investigate the effect of different addition concentrations on the performance of the scale inhibitor, XCN was added at concentrations of 10 ppm, 15 ppm, 20 ppm, 25 ppm, and 35 ppm, respectively, and its scale inhibition rate was tested under each concentration. The test results are displayed in Figure 2. As the concentration increases, the scale inhibition efficiency of the inhibitor rises, reaching 91.26% at 30 ppm. However, when the concentration further increases to 35 ppm, the growth rate of the scale inhibition rate decreases significantly, indicating that the scale inhibitor has reached an adsorption saturation state at approximately 30 ppm. A further increase in the scale inhibitor concentration leads to no obvious improvement in the scale inhibition rate, which is attributed to the threshold effect of scale inhibitors. Each scale inhibitor in the system has a limiting value: as the concentration increases, the inhibitor inhibits crystal nucleation and growth. Once the limiting value is reached, a further increase in concentration results in a slow upward trend of the scale inhibition rate, or even a downward trend. Thus, it can be concluded that the scale inhibitor XCN reaches its threshold at 30 ppm.

Figure 2.

Scale inhibition rate of the scale inhibitor XCN at different concentrations.

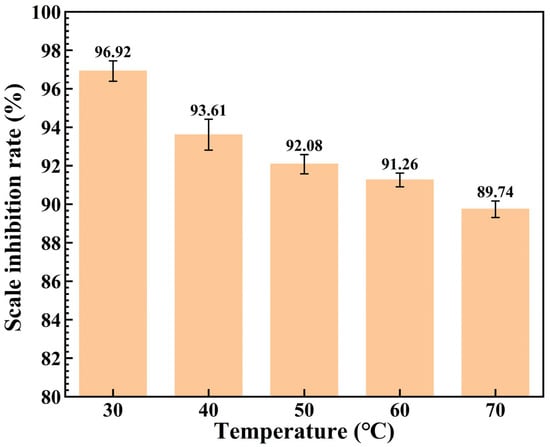

3.3. Effect of Temperature on Scale Inhibition Performance

To investigate the effect of different temperatures on the performance of the scale inhibitor XCN, 30 ppm of the inhibitor was added at 30 °C, 40 °C, 50 °C, 60 °C, and 70 °C, respectively, and its scale inhibition rate was tested at each temperature. The test results are presented in Figure 3. It can be observed that the scale inhibitor exhibits excellent performance at 30 °C, with a scale inhibition rate of 96.92%. However, as the temperature increases, the scale inhibition rate gradually decreases. This is because elevated temperature destabilizes calcium carbonate molecules and impairs the activity of scale inhibitor molecules, thereby reducing the interaction force between the scale inhibitor and calcium ions and leading to a decline in scale inhibition performance [22].

Figure 3.

Scale inhibition rate of the scale inhibitor XCN at different temperatures.

3.4. Effect of Concentration on the Adsorption of Scale Inhibitors

3.4.1. Determination of System Equilibrium

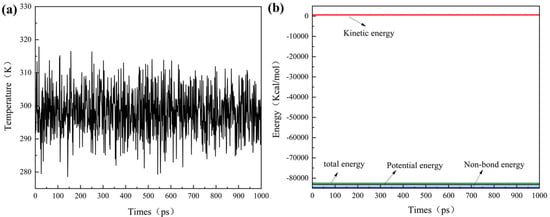

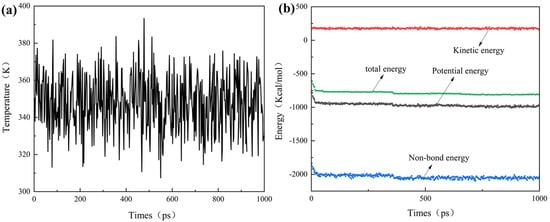

Figure 4a,b display the temperature and energy profiles during the MD simulations of the adsorption system with nine XCN scale inhibitor molecules. The system temperature fluctuates throughout the entire adsorption simulation process. The temperature fluctuation amplitude is relatively large within the range of 0–700 ps, while after 700 ps, the temperature fluctuates within ±15 K, as depicted in Figure 4a. Meanwhile, the energy profile in Figure 4b indicates that the system energy remains stable after 700 ps. Therefore, the system reaches equilibrium in both temperature and energy after 700 ps. The temperature and energy profiles of all other systems are similar, and all systems reached a state of equilibrium.

Figure 4.

Evolution of (a) temperature and (b) energy over time from MD simulation of a system containing 9 XCN molecules adsorbed on the calcite (104) surface, performed at 298 K.

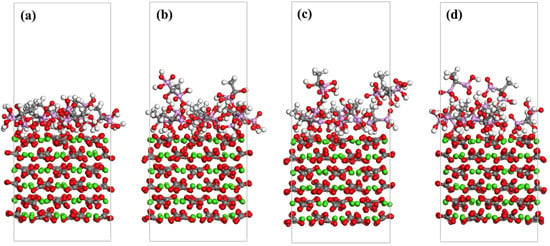

3.4.2. MD Simulation Results

As shown in Figure 5, after MD simulations, a distinct state of disorder is observed inside calcite. This indicates that XCN molecules induce lattice growth distortion of CaCO3 scale crystals, rendering the internal structure of CaCO3 scale crystals loose and prone to fracture, thereby inhibiting the growth of CaCO3. When the number of XCN molecules is three or six, all XCN molecules adsorb onto the calcite (104) surface. As the number of molecules increases to nine, individual XCN molecules fail to adsorb onto the Calcite (104) surface. With a further increase to 12, the number of XCN molecules free in the solution layer increases significantly.

Figure 5.

MD simulation results of systems with different numbers of scale inhibitor molecules on the calcite (104) surface: (a) 3 XCN molecules, (b) 6 XCN molecules, (c) 9 XCN molecules, (d) 12 XCN molecules. Red represents oxygen atoms, white represents hydrogen atoms, pink represents phosphorus atoms, gray represents carbon atoms, and green represents calcium ions.

Table 2 shows that the interaction energy between XCN molecules and the Calcite (104) surface is negative, indicating that the interaction process is exothermic. With the increase in the number of XCN molecules, Eads first increases and then decreases. When the number of XCN molecules is nine, the bonding energy of the system reaches the maximum value of 437.0067 kJ/mol, and a further increase in the number of scale inhibitor molecules leads to a decrease in bonding energy instead. The MD simulation results demonstrate that an increase in the concentration of scale inhibitor molecules can enhance the scale inhibition performance. However, when the concentration exceeds the threshold value, a further increase in the scale inhibitor results in reduced scale inhibition performance, indicating that the threshold effect influences the scale inhibition efficiency.

Table 2.

Energy calculation results (kJ/mol) of different numbers of XCN scale inhibitor molecules on the calcite (104) surface. Standard deviation values are derived from three independent MD runs with distinct initial velocity seeds generated via the Maxwell–Boltzmann method.

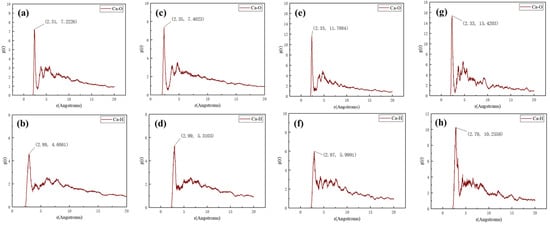

The bond length between scale inhibitor molecules and CaCO3 scale crystals serves as a key parameter for evaluating the interaction strength and identifying the inhibition mechanism [23]. The radial distribution function (RDF) between oxygen (O) and hydrogen (H) atoms in XCN and calcium ions (Ca2+) in calcite was analyzed to elucidate the interaction mechanism. Typically, the first peak in the RDF falling within the range of 1–3.5 Å indicates chemisorption, whereas a peak beyond 3.5 Å suggests physisorption [24,25]. This distinction arises from the fact that interactions in the 1–3.5 Å range typically involve chemical bonds or hydrogen bonding, those between 3.5 Å and 10 Å are dominated by Coulombic and van der Waals forces, and interactions beyond 10 Å are considered non-bonding in nature [26,27]. As shown in Figure 6, the first peaks of the radial distribution functions (RDFs) for all four concentration gradients fall within the range of 1–3.5 Å, indicating the presence of chemisorption between XCN molecules and CaCO3 scale crystals. Specifically, chemical bonding and hydrogen bonding interactions exist between Ca2+ ions and the H and O atoms of XCN. Several weaker peaks beyond 3.5 Å suggest the presence of Coulomb and van der Waals interactions at longer distances. The interaction between calcium ions and oxygen atoms is significantly stronger than that between calcium ions and hydrogen atoms, which can be attributed to the three oxygen atoms in the phosphonate groups of XCN, each carrying a unit negative charge. These highly electronegative oxygen atoms readily form strong electrostatic interactions with calcium ions on the CaCO3 surface, leading to significant distortion of the crystal structure and thereby inhibiting further growth and CaCO3 deposition [28]. With an increasing number of scale inhibitor molecules, the intensity of the first peak also rises, suggesting that higher surface coverage of XCN on the CaCO3 crystal enhances the interaction between the inhibitor and the crystal surface.

Figure 6.

Calculation results of Ca-O and Ca-H radial distribution functions in MD simulations with different numbers of scale inhibitors: (a,b) 3 XCN molecules, (c,d) 6 XCN molecules, (e,f) 9 XCN molecules, (g,h) 12 XCN molecules.

An increase in scale inhibitor concentration generally enhances the direct interaction between inhibitor molecules and Ca2+ ions, thereby improving inhibition performance. However, once the inhibitor concentration exceeds a certain threshold, further addition may lead to a reduction in effectiveness. Consequently, in static scale inhibition tests, the inhibition rate increases with rising concentration until the threshold is reached, beyond which further enhancement becomes marginal.

3.5. Effect of Temperature on the Adsorption of Scale Inhibitors

3.5.1. Determination of System Equilibrium

Figure 7a,b show the temperature and energy profiles, respectively, obtained from the MD simulations of the scale inhibitor adsorption system at 348 K. Throughout the simulation, the temperature exhibits continuous fluctuations. As illustrated in Figure 7a, during the initial 0–600 ps period, the temperature fluctuates significantly, while beyond 600 ps, the fluctuations are confined to within ±15 K. Concurrently, the energy profile in Figure 7b stabilizes after 600 ps, indicating that the system reaches equilibrium in both temperature and energy beyond this point. Similar equilibrium behavior is observed in the other simulated systems.

Figure 7.

Evolution of (a) temperature and (b) energy over time from MD simulation of a system containing 9 XCN molecules adsorbed on the calcite (104) surface, performed at 348 K.

3.5.2. MD Simulation Results

Following MD simulations, evident disorder is observed within the calcite structure, as shown in Figure 8, attributed to lattice distortion induced by XCN molecules during crystal growth of CaCO3 scale. At 328 K, all XCN molecules maintain interactions with the calcite (104) surface. However, at 338 K, individual XCN molecules are observed to detach from the surface. As the temperature increases further, the number of desorbed XCN molecules rises, indicating that elevated temperatures reduce the interaction between XCN molecules and the calcite (104) surface. Furthermore, as shown in Table 3, the interaction energy (Eads) between the XCN scale inhibitor molecules and the calcite (104) surface is negative, indicating an exothermic process. As the temperature increases, the Eads initially rises and then declines, reaching a maximum value of 425.80 kJ/mol at 328 K and decreasing to 332.42 kJ/mol at 358 K. This trend demonstrates that elevated temperatures weaken the interaction between the inhibitor molecules and the calcite surface, thereby reducing the scale inhibition efficiency.

Figure 8.

MD simulation results of 9 XCN scale inhibitor molecules on the calcite (104) surface at different temperature: (a) 328 K, (b) 338 K, (c) 348 K, (d) 358 K. Red represents oxygen atoms, white represents hydrogen atoms, pink represents phosphorus atoms, gray represents carbon atoms, and green represents calcium ions.

Table 3.

Energy calculation results (kJ/mol) of 9 XCN scale inhibitor molecules on the calcite (104) surface at different temperatures. Standard deviation values are derived from three independent MD runs with distinct initial velocity seeds generated via the Maxwell–Boltzmann method.

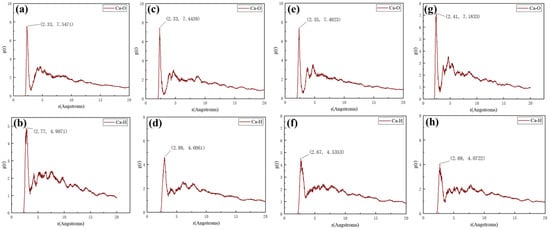

As displayed in Figure 9, the first peaks of the RDFs for Ca-O and Ca-H pairs at different temperatures are all concentrated within the range of 1–3.5 Å, which indicates the presence of chemisorption between XCN molecules and CaCO3 scale crystals, with specific chemical bonding interactions between Ca atoms and H/O atoms of XCN. Weaker secondary peaks beyond 3.5 Å indicate the existence of Coulombic and van der Waals interactions at longer distances. As the temperature increases, the intensity of the first peak gradually decreases, reflecting a gradual weakening of the chemical bonding interaction between XCN molecules and the calcite (104) surface. This trend further confirms that elevated temperatures reduce the scale inhibition effectiveness of XCN, which is consistent with the observed decline in inhibition efficiency in static scale inhibition tests at higher temperatures.

Figure 9.

Calculation results of Ca-O and Ca-H radial distribution functions in MD simulations at different temperature: (a,b) 328 K, (c,d) 338 K, (e,f) 348 K, (g,h) 358 K.

4. Conclusions

In this study, an XCN scale inhibitor with excellent scale inhibition performance was screened out via static scale inhibition experiments. Meanwhile, the effects of concentration and temperature on its adsorption behavior were investigated using MD simulations. The research results are presented as follows:

- (1)

- At 60 °C, the scale inhibition rate of the XCN scale inhibitor reaches a threshold of 91.26% at a concentration of 30 ppm. A further increase in concentration to 35 ppm results in only a marginal improvement in rate.

- (2)

- The XCN scale inhibitor demonstrates excellent performance at 30 °C, achieving 96.92% rate at a concentration of 30 ppm. However, the results from static tests conducted across a temperature range of 30–60 °C show a consistent decline in inhibition rate with increasing temperature.

- (3)

- The MD simulation results identify an optimal concentration for XCN’s scale inhibition. The bonding energy to calcite peaks at 437.0067 kJ/mol with nine molecules, after which it decreases, suggesting a saturation threshold. This non-monotonic trend points to competing effects: while increased concentration strengthens the collective interaction of O/H atoms with surface Ca2+ (as confirmed by RDF analyses), an excess leads to less favorable adsorption configurations. The primary inhibitory mechanism is attributed to chemical adsorption that induces severe lattice distortion and structural weakening.

- (4)

- The MD simulation results also demonstrate that elevated temperatures compromise the scale inhibition performance of XCN. While the inhibitor functions by lattice distortion and exhibits near-complete adsorption at 328 K, a temperature increase to 338 K triggers significant desorption. This is corroborated by RDF analyses, which shows a weakening of the Ca-O and Ca-H interactions critical for adsorption. The findings suggest that beyond its optimal bonding energy threshold (peaking at 437.0067 kJ/mol for nine molecules), thermal energy promotes desorption, likely due to entropic effects, leading to reduced scale inhibition efficiency.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, H.W.; methodology, B.Z. and Y.Y.; formal analysis, T.S.; Conceptualization, supervision, writing—review and editing, S.Z. and G.X.; validation, Z.Y.; data curation, K.H. and J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Hongjun Wu, Bao Zhang, Yi Yang, Tao Sun, Zhongwu Yang, Kun Huang, and Jiaxin Tang were employed by PetroChina Tarim Oilfield Company and the R&D Center for Ultra-deep Complex Reservoir Exploration and Development, CNPC. Author Shiling Zhang was employed by CNPC Engineering Technology R&D Company Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, J.; Tang, M.; Ye, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Y. Scale formation and control in oil and gas fields: A review. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2017, 38, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soprych, P.; Czerski, G. The Use of Biomass Ash as a Catalyst in the Gasification Process—A Review. Energies 2025, 18, 5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Jiu, B.; Yan, D.; Hao, R.; Hao, H. Mineralogy and Geochemistry of Rare Earth Elements in Carboniferous-Permian Coals at the Eastern Margin of the Ordos Basin. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 32481–32501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, M.S.; Hussein, I.; Mahmoud, M.; Sultan, A.S.; Saad, M.A. Oilfield scale formation and chemical removal: A review. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 171, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husna, U.Z.; Elraies, K.A.; Shuhili, J.A.B.; Elryes, A.A. A review: The utilization potency of biopolymer as an eco-friendly scale inhibitors. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2022, 12, 1075–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, D.; Behera, D.; Pattnaik, S.S.; Behera, A.K. Advances in natural polymer-based hydrogels: Synthesis, applications, and future directions in biomedical and environmental fields. Discov. Polym. 2025, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Feng, Q.; Guo, P.; Shi, L.; Zhang, Y. DL-Methionine-Mediated PET-RDRP: A Route to Low-Molecular-Weight Polyacrylic Acid for Effective Scale Inhibition. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 143, e58014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peronno, D.; Cheap-Charpentier, H.; Horner, O.; Perrot, H. Study of the inhibition effect of two polymers on calcium carbonate formation by fast controlled precipitation method and quartz crystal microbalance. J. Water Process. Eng. 2015, 7, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khormali, A.; Ahmadi, S. Trends in using organic compounds as scale inhibitors: Past, present, and future scenarios. In Industrial Scale Inhibition: Principles, Design, and Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 188–205. [Google Scholar]

- Jafar Mazumder, M.A. A review of green scale inhibitors: Process, types, mechanism and properties. Coatings 2020, 10, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yao, Q.; Chen, H.; Liu, B. Scale inhibitors with a hyper-branched structure: Preparation, characterization and scale inhibition mechanism. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 92943–92952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Ren, D.; Liu, T.; Wang, Z.; Ruan, M.; Xu, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Gong, X.; Chen, W. Research on the Mechanism of Scale Inhibitors and Development of Enhanced Scale Inhibition Technology. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e57652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-L.; Ruan, Z.; Han, Y.; Cao, Z.-W.; Zhao, L.; Xu, Y.-Q.; Cao, Z.-Y.; Shi, W.-Y.; Xu, Y. Controllable synthesis of polyaspartic acid: Studying into the chain length effect for calcium scale inhibition. Desalination 2024, 570, 117080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Gao, G.; Ai, Q.; Chen, M.T.; Weng, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, B. Temperature-Responsive Polymer Grafted Carbon Nanotubes for Active Control of Mineral Scaling. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 21506–21514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalab, R.; Saad, M.A.; Hussein, I.A.; Onawole, A.T. Calcite scale inhibition using environmental-friendly amino acid inhibitors: DFT investigation. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 32120–32132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SY/T 5673-2020; General Technical Conditions of Scale Inhibitor for Oil Fields. The Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- GB/T 7476-1987; Water Quality–Determination of Calcium–EDTA Titrimetric Method. The Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 1987.

- Bahlakeh, G.; Ramezanzadeh, B. A detailed molecular dynamics simulation and experimental investigation on the interfacial bonding mechanism of an epoxy adhesive on carbon steel sheets decorated with a novel cerium–lanthanum nanofilm. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 17536–17551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahlakeh, G.; Ramezanzadeh, B.; Saeb, M.R.; Terryn, H.; Ghaffari, M. Corrosion protection properties and interfacial adhesion mechanism of an epoxy/polyamide coating applied on the steel surface decorated with cerium oxide nanofilm: Complementary experimental, molecular dynamics (MD) and first principle quantum mechanics (QM) simulation methods. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 419, 650–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, S.; Ying, Y.; Wang, M.; Xiao, H.; Chen, Z. Theoretical and experimental studies of structure and inhibition efficiency of imidazoline derivatives. Corros. Sci. 1999, 41, 1911–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tian, N.; Huang, X.; Shang, W.; Wu, L. Synergistic inhibition of carbon steel corrosion in 0.5 M HCl solution by indigo carmine and some cationic organic compounds: Experimental and theoretical studies. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 22250–22268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hu, J.; Yang, Z.; Yin, Z.; Xiong, Q.; Zhong, X. The study of a highly efficient and environment-friendly scale inhibitor for calcium carbonate scale in oil fields. Petroleum 2021, 7, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, E.; Abd-El-Khalek, D.; Fawzy, M.; Soliman, K.A.; Abdel-Gaber, A.; Anwar, J. Innovative application of green surfactants as eco-friendly scale inhibitors in industrial water systems. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmaz, R.; Salci, A.; Dogrubas, M.; Dursun, Y.A.; Kaya, S.; Berisha, A.; Kardas, G. Comprehensive experimental and theoretical study on the adsorption and corrosion inhibition efficiency of Pyronin B for mild steel protection in HCl solution. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 21809–21825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Yao, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, E. Alkyl pyridine ionic liquid as a green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic medium. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 27369–27387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzar, A.; Chandler, D. Effect of environment on hydrogen bond dynamics in liquid water. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 76, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. The compatibility of polylactic acid and polybutylene succinate blends by molecular and mesoscopic dynamics. Int. J. Smart Nano Mater. 2020, 11, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Shen, Y.; Liu, W.C.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Y. Mechanisms of Calcium Carbonate Scaling Regulated by Single and Multi-Ion Interactions: Insights from Experiments and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.