Electrode Materials and Prediction of Cycle Stability and Remaining Service Life of Supercapacitors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Scope and Objectives

3. Working Principle and Types of Supercapacitors

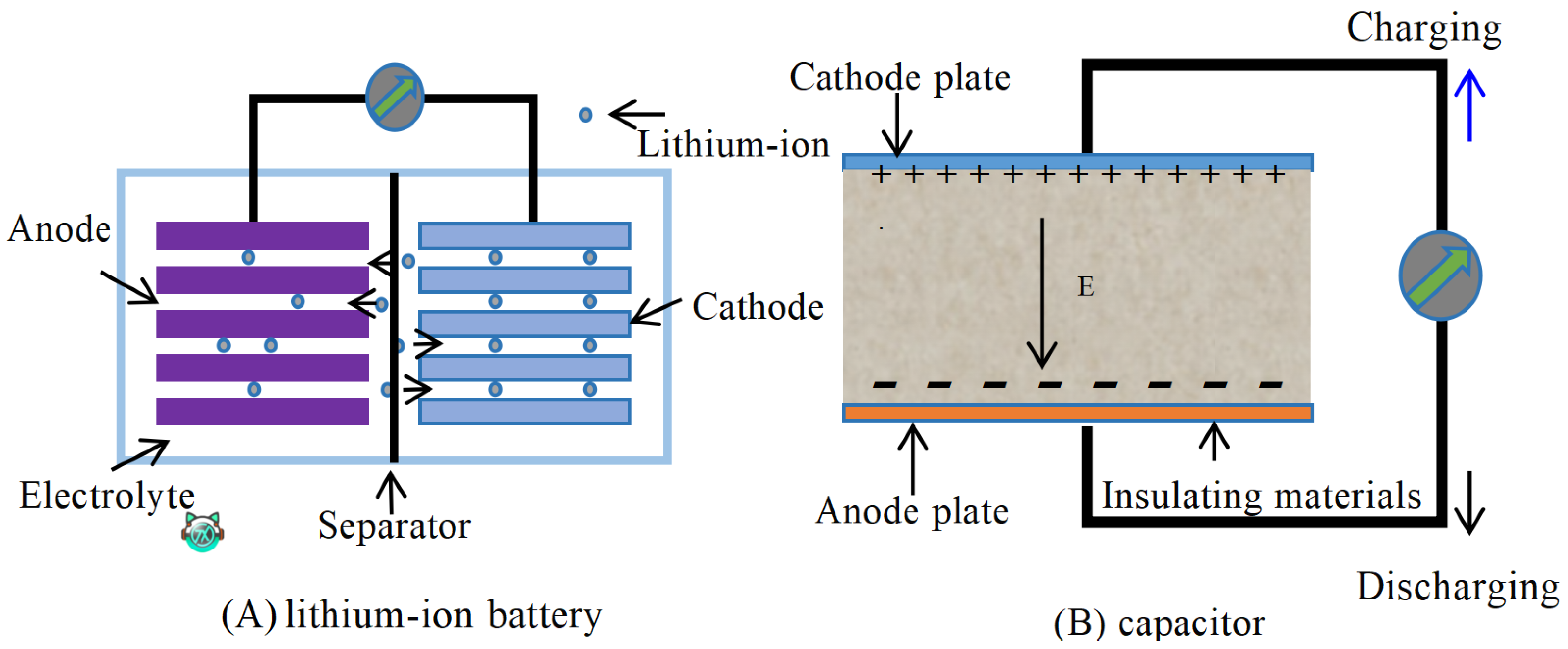

3.1. Structure and Working Principle

3.2. Classification of Supercapacitors

4. Supercapacitor Electrode Material and Service Life

4.1. Materials and Life of Supercapacitors

4.2. Carbon-Based Materials

4.3. Metal Oxides

4.4. Conductive Polymers

4.5. New Materials and Structures

5. Remaining Service Life of a Supercapacitor

5.1. Remaining Service Life of Supercapacitors

5.2. Prediction of Remaining Useful Life

6. Future Prospects

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, A.T.-G. The Political Economy of Global Mobility. Krit. Online J. Philos. 2021, 14, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Hu, Y.; Du, X.; Lu, J.; Li, Z.; Cao, N.; Zhang, S.; Du, H. Movable SiO2 reinforced polymethyl methacrylate dual network coating for highly stable zinc anodes. J. Energy Storage 2025, 132, 117752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Du, H.; Lu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Du, X. Interface synergistic stabilization of zinc anodes via polyacrylic acid doped polyvinyl alcohol ultra-thin coating. J. Energy Storage 2024, 87, 111444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhan, C.; Çil, M.A. A study on hydrogen, the clean energy of the future: Hydrogen storage methods. J. Energy Storage 2021, 40, 102676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Zhang, J.; Mu, X.; Zeng, F.; Wang, K. Innovative deep learning method for predicting the state of health of lithium-ion batteries based on electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and attention mechanisms. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2025, 19, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, K. Enhancing variational autoencoder for estimation of lithium-ion batteries State-of-Health using impedance data. Energy 2025, 337, 138739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Jiang, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, J.; Wang, K. Source-Load Coordinated Optimization Framework for Distributed Energy Systems Using Quasi-Potential Game Method. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2025, 10, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, D.; Byg, V.S.; Ioan, S.D. The development of machine learning-based remaining useful life prediction for lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 82, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xu, L.; Lin, X.; Pecht, M. Battery lifetime prognostics. Joule 2020, 4, 310–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, T.; Huang, G.; Wang, K.; Yan, R.; Zhang, Y. Softly collaborated voltage control in PV rich distribution systems with heterogeneous devices. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 39, 5991–6003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Gu, Z.; Zhang, Z. Lithium battery health degree and residual life prediction algorithm. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2023, 51, 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, S.; Yen, M.; Salinas, Y.S.; Palmer, E.; Villafuerte, J.; Liang, H. Machine learning-assisted materials development and device management in batteries and supercapacitors: Performance comparison and challenges. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 3904–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; Sonia; Phor, L.; Kumar, A.; Chahal, S. Electrode materials for supercapacitors: A comprehensive review of advancements and performance. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaffar, A.; Ahamed, M.B.; Deshmukh, K.; Thirumalai, J. A review on recent advances in hybrid supercapacitors: Design, fabrication and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubal, D.P.; Chodankar, N.R.; Kim, D.-H.; Gomez-Romero, P. Towards flexible solid-state supercapacitors for smart and wearable electronics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 2065–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhulet, A.; Miculescu, F.; Voicu, S.I.; Schütt, F.; Thakur, V.K.; Mishra, Y.K. Fundamentals and scopes of doped carbon nanotubes towards energy and biosensing applications. Mater. Today Energy 2018, 9, 154–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouchachvili, L.; Yaïci, W.; Entchev, E. Hybrid battery/supercapacitor energy storage system for the electric vehicles. J. Power Sources 2018, 374, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, K. Waste plastic triboelectric nanogenerators using recycled plastic bags for power generation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 13, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, L.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Z. Nitrogen-doped graphene for supercapacitor with long-term electrochemical stability. Energy 2014, 70, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, G.; Luo, H.; Liu, L.; Shen, M.; Yang, Y. A novel two-dimensional coordination polymer-polypyrrole hybrid material as a high-performance electrode for flexible supercapacitor. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 2547–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.; Huang, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, L.; Pang, J.; Li, L.; Wang, K. A thermally flexible and multi-site tactile sensor for remote 3D dynamic sensing imaging. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2020, 14, 1039–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yu, S.; Xu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lou, G.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, E.; Chen, H.; Shen, Z.; et al. Sustainable activated carbons from dead ginkgo leaves for supercapacitor electrode active materials. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 181, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wen, H.; Ma, M.; Wang, W.; Yang, L.; Wang, L.; Shi, X.; Cheng, X.; Sun, X.; Yao, Y. A self-supported hierarchical Co-MOF as a supercapacitor electrode with ultrahigh areal capacitance and excellent rate performance. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 10499–10502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandolfo, A.G.; Hollenkamp, A.F. Carbon properties and their role in supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 2006, 157, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Hägele, J. So wenig wie möglich und am besten nativ! Der Radiol. 2011, 51, 917–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xue, Y.; Zheng, X.; Qi, L.; Li, Y. Loaded Cu-Er metal iso-atoms on graphdiyne for artificial photosynthesis. Mater. Today 2023, 66, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Pang, L.; Wang, X.; Waclawik, E.R.; Wang, F.; Ostrikov, K.K.; Wang, H. Aqueous alkaline–acid hybrid electrolyte for zinc-bromine battery with 3V voltage window. Energy Storage Mater. 2019, 19, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; He, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhao, S. CoZn-ZIF and melamine co-derived double carbon layer matrix supported highly dispersed and exposed Co nanoparticles for efficient degradation of sulfamethoxazole. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 469, 144054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Guo, M.; Deng, R.; Zhang, Q. Recent progress of Ni3S2-based nanomaterials in different dimensions for pseudocapacitor application: Synthesis, optimization, and challenge. Ionics 2021, 27, 4573–4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.X.; Blackwood, D.J.; Chen, J.S. One-pot synthesis of self-supported hierarchical urchin-like Ni3S2 with ultrahigh areal pseudocapacitance. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 22115–22122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Guan, B.Y.; Lou, X.W.D. Construction of complex CoS hollow structures with enhanced electrochemical properties for hybrid supercapacitors. Chem 2016, 1, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Bao, S.; Yin, Y.; Lu, J. Three-dimensional porous carbon decorated with FeS2 nanospheres as electrode material for electrochemical energy storage. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 565, 150538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, B.; Punnoose, D.; Rao, S.S.; Subramanian, A.; Ramesh, B.R.; Kim, H.-J. Hydrothermal synthesis and pseudocapacitive properties of morphology-tuned nickel sulfide (NiS) nanostructures. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 2733–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.; Buchholz, D.; Passerini, S.; Weil, M. Life cycle assessment of sodium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 1744–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Hu, W.; Paek, E.; Mitlin, D. Review of hybrid ion capacitors: From aqueous to lithium to sodium. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 6457–6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.; Yang, H.; Wang, L.; Teh, B.K.; Zhong, J.; Chou, H.; Chen, L.; Chen, W.; Shen, Z.; Ruoff, R.S.; et al. Preparation of supercapacitor electrodes through selection of graphene surface functionalities. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 5941–5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Sun, G.; Su, F.; Guo, X.; Kong, Q.; Li, X.; Huang, X.; Wan, L.; Song, W.; Li, K.; et al. Hierarchical porous carbon microtubes derived from willow catkins for supercapacitor applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Kuila, T.; Mishra, A.K.; Rajasekar, R.; Kim, N.H.; Lee, J.H. Carbon-based nanostructured materials and their composites as supercapacitor electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, M.; Mokaya, R. Energy storage applications of activated carbons: Supercapacitors and hydrogen storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 1250–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.L.; Zhao, X. Carbon-based materials as supercapacitor electrodes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 2520–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongprayoon, P.; Chaimanatsakun, A. Revealing the effects of pore size and geometry on the mechanical properties of graphene nanopore using the atomistic finite element method. Acta Mech. Solida Sin. 2019, 32, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, G.; Zhang, L.; Liao, Y.; Shi, Y.; Xie, J.; Lei, F.; Fan, L. Multi-scale model for describing the effect of pore structure on carbon-based electric double layer. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 3952–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangari, M.; Pryor, T.; Jiang, L. Supercapacitors: Review of materials and fabrication methods. J. Energy Eng. 2013, 139, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iro, Z.S.; Subramani, C.; Dash, S.S. A brief review on electrode materials for supercapacitor. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2016, 11, 10628–10643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbizzani, C.; Mastragostino, M.; Soavi, F. New trends in electrochemical supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 2001, 100, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Yan, N.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, P.; Zhong, H.; Zheng, X.; Li, Y.; Hu, X. Fabrication based on the kirkendall effect of Co3O4 porous nanocages with extraordinarily high capacity for lithium storage. Chem. A Eur. J. 2012, 18, 8971–8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Feng, K.; Guo, J.; Wei, X.; Shao, Y.; Zhuang, J.; Lin, T. Effects of microstructure and electrochemical properties of Ti/IrO2–SnO2–Ta2O5 as anodes on binder-free asymmetric supercapacitors with Ti/RuO2–NiO as cathodes. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 17640–17650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Wei, T.; Liang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Qu, L.; Fan, Z. Vertically oriented graphene nanoribbon fibers for high-volumetric energy density all-solid-state asymmetric supercapacitors. Small 2017, 13, 1700371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Dong, H.; Sun, W.; Lv, L.; Yang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, F.; Wang, Y.; Chou, S.; et al. Progress and Perspective of High-Entropy Strategy Applied in Layered Transition Metal Oxide Cathode Materials for High-Energy and Long Cycle Life Sodium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2417258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xu, Y.; Wu, J.; Huang, J. Bio-inspired hierarchical nanoporous carbon derived from water spinach for high-performance supercapacitor electrode materials. Nanoscale Adv. 2022, 4, 1445–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qing, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, L.; Wu, Y. N-doped carbon fibers derived from porous wood fibers encapsulated in a zeolitic imidazolate framework as an electrode material for supercapacitors. Molecules 2023, 28, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, J.-K.; Zhang, H.-W.; Lei, Y.; Li, K.-Y.; Li, B.; Deng, H.-X.; Wang, H.; Zou, L. Buckwheat core derived nitrogen-and oxygen-rich controlled porous carbon for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Cent. South Univ. 2023, 30, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, S.K.; Hwang, Y.; Lee, H.-M.; Kim, B.-J.; Park, S. Porous activated carbon derived from petroleum coke as a high-performance anodic electrode material for supercapacitors. Carbon Lett. 2024, 34, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somaily, H. Development of Nd doped AlFeO3 electrode material for supercapacitor applications. J. Energy Storage 2024, 90, 111958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, R.; Lin, H.; Zhou, P.; Ying, Y.; Li, L. A novel P-doped Ni0.5Cu0.5Co2O4 sphere with a yolk-shell hollow structure for high-energy–density supercapacitor. Mater. Lett. 2023, 348, 134682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.A.; Patil, D.S.; Nandi, D.K.; Islam, M.M.; Sakurai, T.; Kim, S.-H.; Shin, J.C. Cobalt-based metal oxide coated with ultrathin ALD-MoS2 as an electrode material for supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 435, 135066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Sun, M.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Liang, J.; Hao, J.; Wang, B.; Xu, H.; Wu, C.; Qin, W.; et al. Preparation of Manganese Cobalt-Based Binary Metal Oxide for High-Performance Quasi-Solid-State Supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 6945–6953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Hussain, T.; Shuaib, U.; Mubarik, F.E.; Tahir, M.; Toheed, M.A.; Hussnain, A.; Shakir, I. Solvothermally synthesized MnO2@ Zn/Ni-MOF as high-performance supercapacitor electrode material. Ionics 2025, 31, 3631–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Li, Y.; Yang, M.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, Y. Construction of hierarchical Mn2O3@ MnO2 core–shell nanofibers for enhanced performance supercapacitor electrodes. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 8190–8197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peringath, A.R.; Bayan, M.A.; Beg, M.; Jain, A.; Pierini, F.; Gadegaard, N.; Hogg, R.; Manjakkal, L. Chemical synthesis of polyaniline and polythiophene electrodes with excellent performance in supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73, 108811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Qin, Z. Polyaniline nanoarrays grown on holey graphene constructed by frozen interfacial polymerization as binder− free and flexible gel electrode for high− performance supercapacitor. Carbon 2024, 225, 119100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawade, A.K.; Tayade, S.N.; Dubal, D.P.; Mali, S.S.; Hong, C.K.; Sharma, K.K.K. Enhanced supercapacitor performance through synergistic electrode design: Reduced graphene oxide-polythiophene (rGO-PTs) nanocomposite. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 492, 151843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Dong, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, W.; Li, D.; Yu, F.; Chen, Y. α–α Coupling-dominated PPy film with a well-conjugated structure for superlong cycle life supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 7806–7818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syamsai, R.; Grace, A.N. Ta4C3 MXene as supercapacitor electrodes. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 792, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.; Yang, B.; Wen, F.; Xiang, J.; Li, L.; Wang, W.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, B.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Z.; et al. Flexible all-solid-state supercapacitors based on liquid-exfoliated black-phosphorus nanoflakes. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 3194–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, N.; Singh, S.; Malik, G.; Bhardwaj, S.; Sharma, S.; Tomar, A.; Issar, S.; Chandra, R.; Maji, P.K. Chemically tuned cellulose nanocrystals/single wall carbon nanosheet based electrodes for hybrid supercapacitors. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2024, 8, 3595–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Cheng, Y.; Du, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Nie, G. Molybdenum trioxide/carbon nanotubes/poly (5-carboxylindole)(MoO3/MWCNT-COOH/P5ICA) nanocomposites as an electrode material for high-performance hybrid supercapacitors. Synth. Met. 2024, 307, 117683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Sun, X.; Deng, X.; Yin, S.; Zhang, T. Cellulose aerogel-based copper oxide/carbon composite for supercapacitor electrode. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 6774–6782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Li, G.; Wu, X. Potassium gluconate-assisted synthesis of biomass derived porous carbon for high-performance supercapacitor. J. Porous Mater. 2023, 30, 2113–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Gao, M.; Xu, T.; Si, C. Wood-based hierarchical porous nitrogen-doped carbon/manganese dioxide composite electrode materials for high-rate supercapacitor. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2023, 6, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, H.; Lu, X.; Zhao, Y. Research on capacity life prediction model of supercapacitors. Chin. J. Power Source 2019, 49, 270–282. [Google Scholar]

- Weigert, T.J.; Tian, Q.; Lian, K.K. Cycle life prediction of battery-supercapacitor hybrids using artificial neural networks. ECS Trans. 2010, 28, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, Y.; Pang, J.; Wang, K. Remaining useful life prediction for supercapacitor based on long short-term memory neural network. J. Power Sources 2019, 440, 227149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Kang, L.; Peng, F.; Wang, L.; Pang, J. Hybrid genetic algorithm method for efficient and robust evaluation of remaining useful life of supercapacitors. Appl. Energy 2020, 260, 114169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, M.; Hasan, M.N.; Qin, S. Early and robust remaining useful life prediction of supercapacitors using BOHB optimized Deep Belief Network. Appl. Energy 2021, 286, 116541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yi, Z.; Kang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K. A novel supercapacitor degradation prediction using a 1D convolutional neural network and improved informer model. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2024, 9, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Lin, W.; Lou, G. Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Supercapacitors Based on BO-BiLSTM. Adv. Technol. Electr. Eng. Energy 2023, 42, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

| Type | Charge Storage Mechanism | Disadvantages | Electrode Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical Double-Layer Capacitor (EDLC) | Non-Faradaic process (Electrical Double-Layer, EDL) | Low specific capacitance, low energy density | Carbon materials |

| Pseudocapacitor | Faradaic process (Redox reactions) | Relatively low-rate performance | Metal oxides or polymers |

| Hybrid Capacitor | Pseudocapacitance + EDL | Structurally complex | Oxidation–reduction reactions of materials and carbon materials |

| Electrode Material/Material System | Specific Capacitance | Cycling Stability | Cycle Number | Electrolyte | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nd-AlFeO3 | 1326 F·g−1 @ 1 A·g−1 | 91% | 5000 | 6 M KOH | [54] |

| P-Ni0.5Cu0.5Co2O4 | 1570.2 F·g−1 @ 1 A·g−1 | 78% | 5000 | 3 M KOH | [55] |

| NiCo2O4-MoS2 | 2445 mF·cm−2 | — | — | 2 M KOH | [56] |

| Mn-Co Oxide | 4.48 F·cm−2 @ 10 mA·cm−2 | 85% | 4000 | PVA-KOH Gel | [57] |

| MnO2@Zn/Ni-MOF | 1537 F·g−1 @ 2 A·g−1 | 89% | 4000 | 6 M KOH | [58] |

| MACNC/CNT | 1389.2 mF·cm−2 @ 0.02 A·cm−2 | 74.6% | 12,000 | — | [66] |

| PANI/HG-10 | 793.7 @ 1 A·g−1 | 90.5% | 5000 | 1 M H2SO4 (Gel State) | [60] |

| rGO-PTs nanocomposite | 293 @ 0.5 A·g−1 | 99.4% | 3000 | 2 M HCl + PVA Gel | [60] |

| N-doped wood fiber carbon | 270.7 @ 0.5 A·g−1 | 98.4% | 10,000 | 6 M KOH | [69] |

| Buckwheat-derived porous carbon | 660 mF·cm−2 (≈300 F·g−1) | Excellent | >5000 | 6 M KOH | [52] |

| Petroleum coke-activated carbon | 470 @ 0.5 A·g−1 | 98% | 15,000 | 3–6 M KOH | [53] |

| ZIF-8-derived porous carbon | 130–250 | Excellent | — | 6 M KOH | [51] |

| Model | Input Features | Dataset Source | Performance Metrics | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrhenius Model | Temperature, current intensity, cycle number | Experimental data (25–55 °C) | Error < 3% | [71] |

| 3-layer BPNN | Short-term charge–discharge curve, voltage | Battery–supercapacitor hybrid experimental data | Error < 4% | [72] |

| LSTM Network | Charge–discharge cycle number | Supercapacitor degradation experimental data | — | [73] |

| GA–LSTM | Temperature, voltage, cycle number | Steady-state and HPPC experimental data | RMSE = 0.0161–0.0264 | [74] |

| DBN + BOHB | — | — | Prediction speed ↑ 77%, training data ↓ to 6% | [75] |

| 1D CNN + Improved Informer | Voltage, current, temperature (normalized data) | — | RMSE ↓ 32.71%, MAE ↓ 28.50%, R2 ↑ 4.79% | [76] |

| BO–Bist | Historical capacity data | Supercapacitor experimental data | RMSE = 2.16%, AEP = 0.59% | [77] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, W.; Wang, J.; Guo, R.; Wang, J.; Song, J.; Wang, K. Electrode Materials and Prediction of Cycle Stability and Remaining Service Life of Supercapacitors. Coatings 2026, 16, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010041

Jiang W, Wang J, Guo R, Wang J, Song J, Wang K. Electrode Materials and Prediction of Cycle Stability and Remaining Service Life of Supercapacitors. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010041

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Wen, Jingchen Wang, Rui Guo, Jinwei Wang, Jilong Song, and Kai Wang. 2026. "Electrode Materials and Prediction of Cycle Stability and Remaining Service Life of Supercapacitors" Coatings 16, no. 1: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010041

APA StyleJiang, W., Wang, J., Guo, R., Wang, J., Song, J., & Wang, K. (2026). Electrode Materials and Prediction of Cycle Stability and Remaining Service Life of Supercapacitors. Coatings, 16(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010041