Abstract

This work presents a microstructural characterization methodology for Diamalloy 3001 metallic powders sprayed onto Inconel 718 substrates by flame combustion. Hence, two flame stoichiometric (acetylene/oxygen) rates and specified thermal spray distances were performed in order to study their effects on the developed microstructure of the sprayed coatings. The morphology and chemical composition of the developed coatings were evaluated with microscopy, and a comparison of microstructural quality was performed. The findings indicated that spray distance affected coating quality, which is composed of morphology-type lamellar with elongated features, while gravel-like morphologies related to semi-solid powder particles were observed. Moreover, X-ray diffraction analyses established that chemical content of phases rich in oxides increased proportionally with spray distance. Vickers hardness measures and three-point bending tests were correlated with the microstructure and spray distance. These characteristics show that cobalt-based coatings could be proposed for commercial applications requiring high mechanical resistance.

1. Introduction

High-tech structural components and equipment are in many times subjected to harsh environmental conditions, such as high pressure, high temperature, extreme fluids flow, sour services in the oil and gas industry, etc., which can cause corrosion, erosion, oxidation, abrasion, wear, hydrogen-induced cracking, or other damage mechanisms. However, the useful lifetime of such technologies can be extended with the application of hard coatings on the surfaces that will be exposed to such harsh environments. Hence, hard coatings can protect structural components against accelerated damage or failure mechanisms, ensuring structural integrity. This has been observed in subsea production systems in the oil and gas industry, as well as in jet turbine engines blades, pipelines, etc. [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. In the literature, there are several available processes to manufacture hard coatings: amongst them, the thermal spray high-velocity oxygen fuel (HVOF) technique presents healthy and safety issues. Therefore, this thermal spray process usually needs to be undertaken in a specialized thermal spray chamber with sound attenuation devices and dust extraction facilities [9,10,11,12,13,14].

Thermal spray HVOF equipment usually requires higher investment, compared with other thermal spraying processes, such as flame and arc spraying. And the deposition of hard coatings is very difficult to achieve in the internal surfaces of small cylindrical components or other types of small internal surfaces. These limitations have led to the selection of other attractive coating manufacturing alternatives, with potential application in the industry. To manufacture high-quality hard coatings and to protect high-tech mechanical components, with low costs, lower dusts, low fume levels, easy to transport, and fast and reliable application, it is sometimes needed to come back to traditional processes [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Thus, flame combustion spray, recently named the low-velocity oxygen fuel (LVOF) process, has been extensively employed to develop hard metallic coatings with alloy powders sprayed onto metallic surfaces by a thermal gun, where the powders are heated close to their melting point. The near-molten powders metallic are transported and accelerated by the mixture of gas stream of the thermal gun and projected onto the surface being coated [9,15]. During impact, the micropowder droplets principally flow like lamellas, which adhere to each other to develop the coating. The semi-molten powders interlock as they solidify, and the coating thickness is obtained by multiple passes over the material being coated. One advantage of this thermal spray process is that the coatings can be applied to surfaces without significant heating; therefore, the mechanical and microstructural properties of the substrate surface are maintained. The flame thermal spray process has been applied to repair and recoat damaged materials [1,3,4,5,6,7,8]; here, the developed coatings were capable of also being repaired during their manufacture and/or after their service life.

Despite the advantages of the LVOF coating process, one of the fundamental disadvantages is the incorporation of oxide phases in the coating, which can cause the diminution of all properties. Such oxide phases are directly related to the process parameters, amongst them, the spray distance and the acetylene-to-oxygen stoichiometric gas ratio. It is well known that flame temperature depends on the oxygen-to-fuel gas ratio, which is a key parameter to control the quality of coatings. Therefore, the optimization of these thermal spray parameters is fundamental in order to develop high-quality hard coating and to protect mechanical structures against corrosion [25,26,27,28,29]. In the literature, papers that examined the relationship between the microstructure and flame stoichiometry have been found [22,23]. However, very little work has been published focusing on the development of Co-based alloy by LVOF. It is also known that the acetylene-oxygen gas ratio could be employed to develop hard coatings [13,15,24]. It is well known that flame types can be classified as fuel, neutral, oxidizing, and super-oxidizing. A super-oxidizing flame refers to an excess of oxygen, for example, a 1:4 ratio, which includes 1 unit of acetylene and 4 units of oxygen. Nevertheless, the excess of oxygen can affect the quality of the coating microstructure. In a fuel flame, the amount of fuel (acetylene) is greater than that of the oxidizer (oxygen), whereas in a neutral flame, there is an equal molar amount of fuel and oxidizer. Meanwhile, in super-oxidizing flames, the amount of oxygen is higher.

Despite the beneficial mechanical properties and low-cost process, cobalt-based coatings have scarcely been manufactured by the LVOF process [13,15,24]. Therefore, in this work, the LVOF process was carried out in order to stablish the most accurate thermal spray conditions of Co-based powders, such as the spray distance and gas flow ratio, and their association with the formed microstructure and oxide species in the coatings. To start the work, the selection of spray distance range was based on previous research works [13]. The gas flow ratio was also chosen in order to optimize the stoichiometry that would reduce the formation of oxides in the coating. X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analyses were performed to establish the coating microstructure and crystal phase composition. Finally, Vickers hardness test and fractography behavior were associated with the cobalt-based microstructure in cross-section samples, and the fracture characteristics were identified as a function of the spray distance and gas ratio.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

For experimental work, a solid rod of Inconel 718 alloy (Maher Ltd. VD, UK, metal International; chemical composition: 54Ni, 18Cr, 18Fe, 5Nb, 3Mo, 1Ti, and 0.5Al (wt.-%)) was used to prepare the substrates, where the coatings were applied. The chemical composition of Inconel 718 alloy is similar to that employed as a structural material in turbine blades. Substrates with a diameter of 25 mm and a thickness of 3 mm were obtained. Then, the substrates were sanded with SiC # 1000 grit sandpaper before the application of the coatings. The sanded substrates were also degreased with acetone in order to ensure a better adherence of the coating. Commercially available metallic Diamalloy 3001 powders, obtained from SULZER LT Company, MX were employed to manufacture the coatings. The powders have the following chemical composition: Co-based, Mo 28.5, Cr 17.5, and Si 3.4 wt.%; the particles have a nominal size distribution between 45 ± 5.5 µm and macro hardness values between 50 and 55 HRC. To apply the coatings, an oxyacetylene Castolin Terodyne System 2000, MX gun was employed. Before cobalt-based powders were deposited, the substrates were pre-heated with the torch gun for about five seconds to reach a temperature of about 400 °C on substrate surfaces. Here, a pyrometer laser marc LT Lutron “instruments digital” model TM—949, MX was utilized to measure the temperature on Inconel 718 substrates. Then, the substrates were coated with Diamalloy 3001 cobalt-based powder, layer by layer, until the specified thickness was achieved. Cobalt-based coatings with a thickness of 150 μm were obtained in this work. Table 1 describes the LVOF parameters employed in the thermal spray of cobalt-based powders. In order to spray, the substrates were properly fixed on the rotor and sample substrate holding devices. To fix the gas ratio, the flame’s temperature range was analyzed for the different mixtures of acetylene/oxygen. Once the coatings were developed, the substrates and coatings were microstructurally characterized.

Table 1.

Tests matrix.

An image analysis software, Matrox Inspector 4.0, was used to analyze the porosity on the cross-section of the coatings. A Hitachi scanning electron microscope (SEM) with an EDS detector, normally in the range of 15 Kv, was used for microstructural analysis. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses were also performed using an X’PertPro (Bruker D8-ECO Advance) with a Bragg–Brentano setup, equipped with an X’Celeratrimina, a 2θ range of 20–80°, using a 0.21 step size, 2.0 s per step, and Cu-Kα radiation with a λ1/4 of 1.541 parameters to identify the phases of the coatings.

2.2. Flame Thermal Spray Coating Process

As explained above, the as-received Diamalloy powders were thermally projected by the gas stream onto Inconel 178 alloy substrates. The feeding of the powders was performed through the powder’s container, located in the upper part of the thermal gun. From the container, the powders descended by gravity and were transported through the core of the flame until they reached the substrate surface, which was preheated in order to avoid thermal shock with the powders. Hence, the mechanical adherence of the developed coatings will depend on the initial obtained layer, controlled by the parameters described in Table 1. Thus, during the thermal spray processes, microstructural surface features were developed, which have a significant influence on coating properties [30]. Once the substrates were preheated at about 400 °C for 5 s, a thermal spray shot for 15 s was applied, then the thermal gun was switched off for 5 s before the next thermal spray shot. Two thermal spray shot passes were performed in order to achieve more uniform coatings, as suggested in the literature [13,15].

Three thermal spray distances of 8 cm, 9 cm, and 11 cm were used, and two variations in acetylene/oxygen gas ratios of 50/35 and 55/40, along with three thermal sprays distances, were performed in order to promote a reducing atmosphere rich in unburned acetylene. To correlate the gas ratio with the temperature of flame combustion, the gas/ratio spectrum vs. the temperature reported in the literature was used [13,15]. This graph of temperature vs. the mixture of acetylene/oxygen (%) showed that the flame temperature increases with increasing oxygen increment up to approximately 3164 °C (at x = 1.42). Beyond this point, the temperature decreases with oxygen increases. Nonetheless, it is also observed that the temperature is still very high, even at an acetylene/oxygen ratio of 1:2.6 [17,18,24]. Moreover, to prove a reduced atmosphere, it can be estimated the theoretical volume of gas of acetylene in the gas ratio, for each reaction with oxygen to semi-melt Co-based powders mass, considering the atmospheric pressure under Mexico City conditions, as follows:

Also, regarding parameters, such as particle in-flight or particle dwell distance in the flame, for velocity particles < 105 m/s and particle diameters in the range of 10–90 µm, the thermal and mechanical interactions between the jet and particle stream can be characterized. The powder-to-jet mass flow ratio parameter (MF) can be defined by the following equation [24]:

where Mjet stream and Mpowder (g/min) are the mass flow of both acetylene and oxygen constituting the jet stream and the Diamalloy powder feed rate, respectively. It is frequently considered that for values of MF exceeding 4%, obtained at a given combination of deposition parameters, the jet stream thermal and flow properties cannot be considered independent from the powder stream (called the “loading effect”).

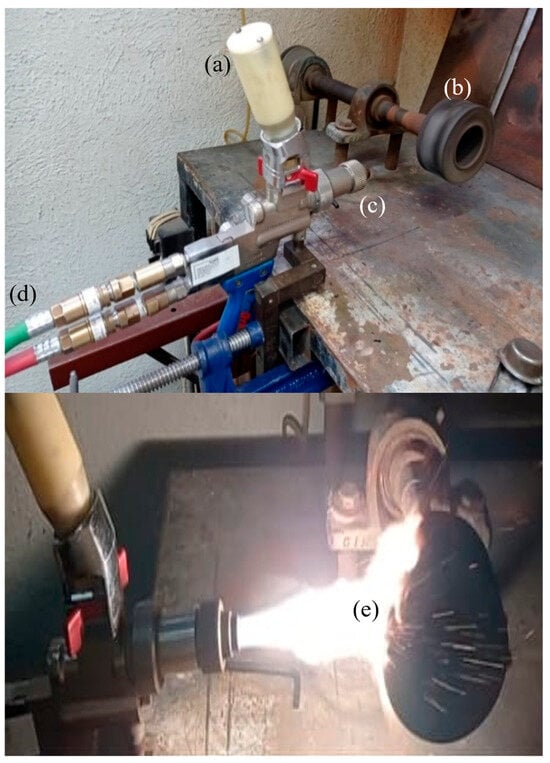

The employed thermal spray gun and other devices are shown in Figure 1, which has a powder container with Co-based superalloy powders, as observed in Figure 1a. To manufacture the thermal spray coatings, the Inconel 718 substrates were mounted on a rotary samples holder as observed in Figure 1b, which rotates at a speed of 300 rpm, with the aim to avoid overheating of the substrates and Diamalloy powders, during the thermal spraying process.

Figure 1.

Thermal projection system: (a) powder tank, (b) rotary sample holder, (c) thermal gun, (d) gases houses supplier, and (e) application of the coating.

Figure 1 also shows how the thermal gun is connected to the gauges of oxygen and acetylene gas supply. It can also be observed that the acetylene/oxygen gas mixture acts as a drag flow gas for the Co-based powders, which is beneficial for the thermal processes; when the flame is created, the particles are more likely to penetrate the core of the flame, allowing particle surfaces to obtain a semi-molten state and achieve a high spray velocity. Figure 1e shows the thermal spraying of Co-based powders onto Inconel 718 substrates.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructural Characterization

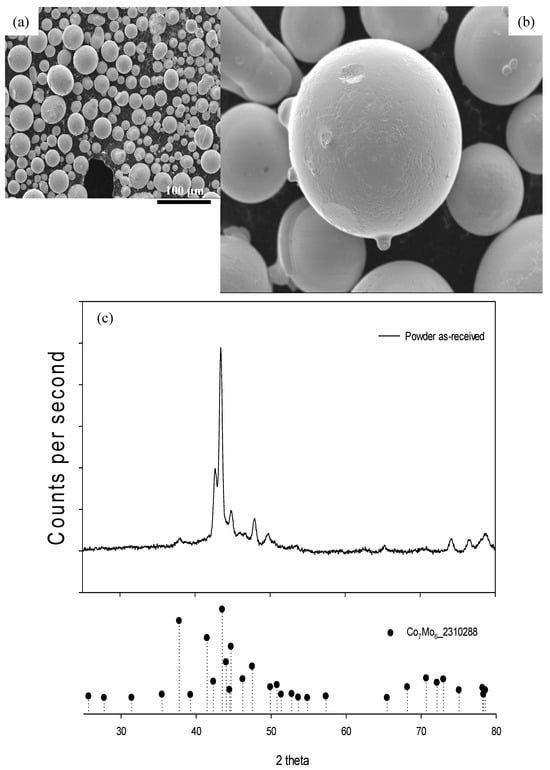

Figure 2a shows a micrograph of Co-based powders, which are composed of powders with sizes ranging from 5.5 µm to 45 μm. This size distribution can favor the development of compacted layers during coating build up. The spherical powders morphology would also favor the flux through the torch of the thermal gun. The micrographs also show a structuration of growth dendritic for the powder, as clearly observed in Figure 2b. And Figure 2c shows XRD analysis from Co-based powder, where a preferential Co7Mo6 phase can be indexed as ISCD 2310286. This phase has been reported by presenting a hexagonal structure with lattice parameters a = 4.7620 and c = 25.6150.

Figure 2.

Co-based powders: (a) SEM micrograph, (b) close-up of powders, and (c) XRD analysis, respectively.

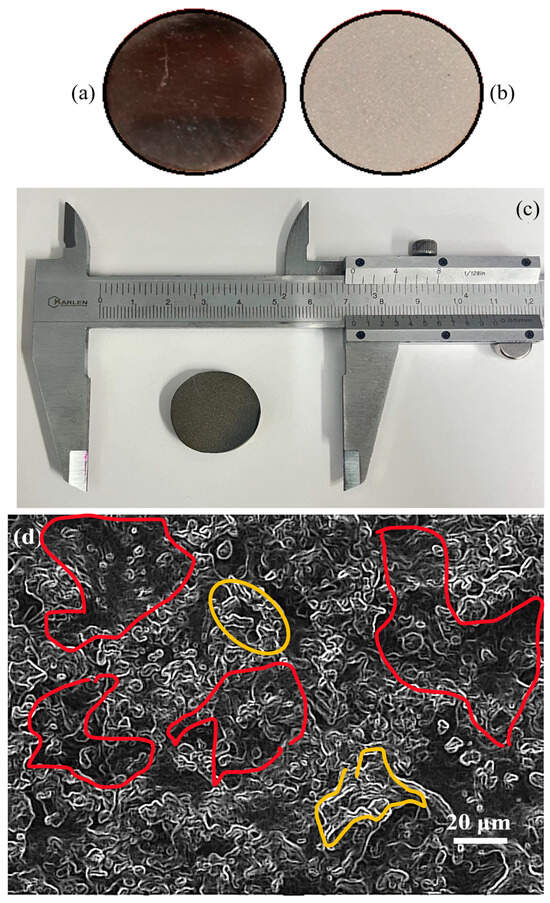

The surface of the Inconel 718 substrate before the spray process is shown in Figure 3a. Figure 3b shows the surface of the Inconel 718 substrate after sanding with # 1000 grit sandpaper, where the roughness formed by ridges and valley zones can be observed. After the spray process, the obtained coating is shown in Figure 3c,d, where typical features of splat coatings are observed. To assess the performance of each sprayed coating condition, a contrasted image process was utilized for each micrograph, as depicted in Figure 3d. Hence, a micrograph obtained at a magnification of 500× is shown, where two main zones are observed, corresponding well to less-rough (yellow marks) and high-rough (red marks) surfaces, respectively. These zones can be differently composed of un-molten, semi-molten, agglomerated particles, and molten powders (splats), respectively. These typical features have also been reported in the literature [31,32,33].

Figure 3.

Inconel 718 substrates: (a) without sanded surface, (b) after sanded process, (c) with Co-based coating, and (d) contrasted image for the analysis of splat morphology (colored borders will mean like-features surfaces).

In addition, to classify splat morphology, Fauchais et al. reported various splat features, focusing on their historical solidification conditions [31]. Hence, four types of morphologies of splash, rugged, gravel-mounted, and disk splats, can be classified in the manufactured coatings [32,33]. Therefore, in this work, each formed microstructure was compared in the coatings developed at each thermal spray condition. From here, better LVOF process conditions to develop high-quality Co-based coatings was established. Splash and disk splats were mainly developed from semi-melted powders, while rugged and gravel-mounted morphologies were obtained from agglomerated powders. Gravel-mounted morphologies were observed from only hollow spherical powders, and rugged morphologies were observed in semi-melted powders at high temperature. Hence, it was found that the ratio of splat morphology changes with the different thermal spray conditions. Consequently, coating performance was assessed based on the morphology of each surface coating and the spraying condition. Furthermore, measurements of roughness were carried out for each sample and associated with the microstructure of the coatings.

3.2. Microstructural Performance of the Coating Deposited Using 50/35 Oxyacetylene Flame Stoichiometry

3.2.1. SEM Coating Analysis for Gas Ratio of 50/35 and Thermal Spray Distance of 8 cm

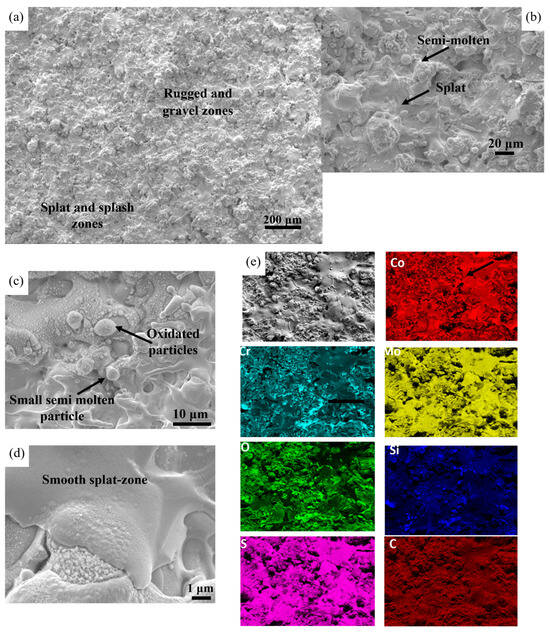

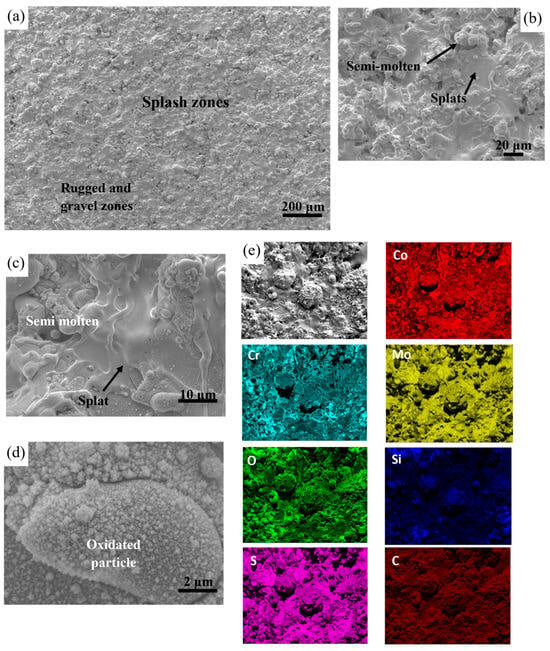

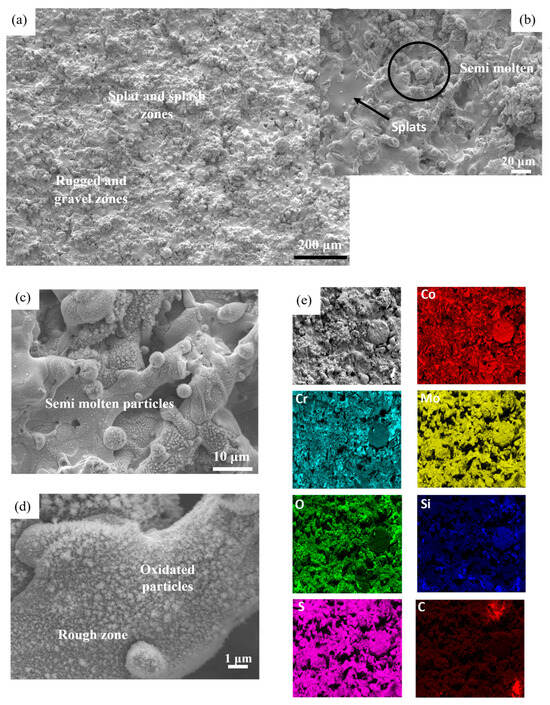

Figure 4a–d show micrographs of the coating developed at a thermal spray distance of 8 cm. From these figures, it can be observed that the microstructure is formed by rugged and splat regions. The figures also show small satellite spherical particles. Figure 4e shows the EDS mapping elemental analysis, which shows a homogeneous elemental distribution of Co and Cr, followed by Mo and S, and a less uniform distribution of Si and C. The presence of high contents of Cr and O suggests the formation of oxides of chrome. Moreover, the presence of a large number of molten particles and very few, or no, semi-molten particles was observed. This observation can signify that an atmosphere rich in oxygen was promoted at a high flame temperature during the spray process, consequently leading to the formation of oxides.

Figure 4.

Micrographs of the surface of Co-based coating on Inconel 718 substrate at a spray distance of 8 cm and a 50/35: (a) rugged and gravel zones, (b) splat close-up from (a), (c) oxides, (d) smooth zone, and (e) EDS mapping spectroscopy.

3.2.2. SEM Coating Analysis for Gas Ratio of 50/35 and Thermal Spray Distance of 9 cm

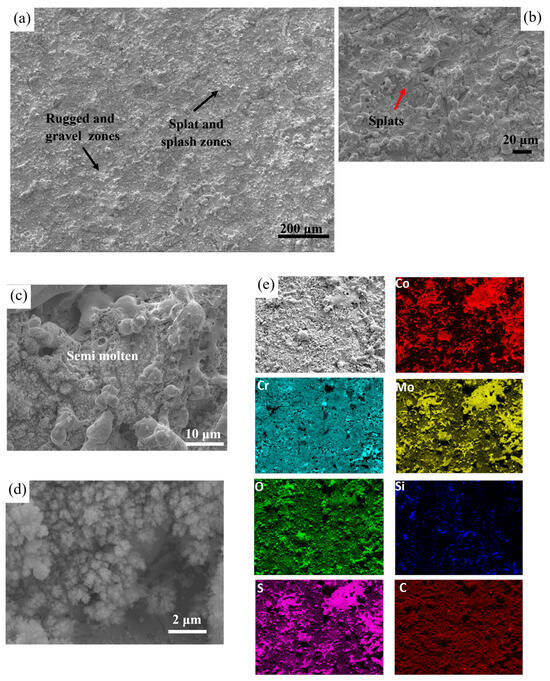

Figure 5a–d show the micrographs of the coating developed at a thermal spray distance of 9 cm. In the figures, rugged and splat regions, as well as some semi-spherical particles (gravel) and splat zones are clearly observed.

Figure 5.

Surface of Co-based coating on Inconel 718 substrate at a spray distance of 9 cm and 50/35: (a) splash, rugged, and gravel zones, (b) splats, (c) semi-molten particles, (d) oxides, and (e) EDS mapping spectroscopy elemental maps at spray distance of 9 cm.

Figure 5e shows the EDS mapping spectroscopy elemental distribution of Co, Cr, and Mo, followed by S and O, with smaller zones containing a distribution of Si and C. Both micrographs and EDS maps showed the effect of the 50/35 gas ratio on the development and coating quality. Nevertheless, a high content of Cr and O on a splat surface (molten powder) was also observed, suggesting the formation of oxides during the present spray distance. The presence of a number of semi-molten particles was also observed, likely created from agglomerates due to the large spray distance of 9 cm and long-time exposure to the flame during the spray process.

From the above results, it is possible to observe improvements of the microstructural features on the manufactured coatings. It can also be observed that these thermal spray parameters promoted the formation of larger splash areas and smaller rough coating regions. Furthermore, it was found that both the number and size of semi-melted particles were considerably small, while the creation of a major stacking of splats occurred due to the molten deposition of the powders.

3.2.3. SEM Coating Analysis for Gas Ratio of 50/35 and Thermal Spray Distance of 11 cm

Figure 6a–d show micrographs taken from the coatings developed at a thermal spray distance of 11 cm. In this condition, similar to the previous conditions, rugged and splats regions were developed on the coating, and semi-spherical particles were created, as observed in Figure 6d. A close view from a rugged region showed that the powders did not create homogeneous surfaces due to the presence of a higher number of semi-molten powders that impacted the substrate. The X-ray mapping elemental distribution analysis observed in Figure 6e shows a uniform and homogeneous elemental distribution for Co, followed by Mo, S, and O, with less uniformity for Si and C elements.

Figure 6.

Surface of Co-based coating on Inconel 718 substrate at spray distance of 11 cm and 50/35: (a) splats, splash, rugged and gravel zones, (b) splats, (c) semi-molten particles, (d) very small semi-molten particles, and (e) EDS mapping spectroscopy elemental maps sprayed at 11 cm.

Both micrographs and EDS mapping analyses showed the effect of the spray distance in the developed coatings. The microstructure was composed of splats of size in the range beyond 40 µm, with smooth morphology (stacking splats). Moreover, the presence of a high number of semi-molten particles was also observed, forming agglomerates with a size of several microns. In addition, a high content of Cr, O, and Mo suggests the formation of oxides. This last observation would signify the presence of a high ratio of acetylene/oxygen in the flame. At this spray distance, semi-spherical particles of small size with a flower-like morphology (as observed in Figure 6) was also observed. Therefore, this last thermal spray condition showed that a spray distance of 11 cm produced a heterogenous microstructure. Nonetheless, the spray distance of 9 cm and a 50/35 gas ratio produced better results in terms of homogeneous microstructure.

3.3. Microstructural Performance of the Coating Deposited Using 55/40 Oxyacetylene Flame Stoichiometry

3.3.1. SEM Coating Analysis for Gas Ratio of 55/40, and Thermal Spray Distance of 8 cm

Figure 7a–d show the micrographs of the coating, developed at a thermal spray distance of 8 cm. From these figures, it can be observed that the surface of the developed coating, is composed principally of rough and splats regions. A close view from the figures, shows some semi spherical particles and a high number of molten particles of large size. Similarly, to previous conditions, it was also observed that semi-molten powders, correspond to molten agglomerates composed by chromium oxide, as observed in Figure 7. It is worth to note the absence of cracking on the splats, contrary to previous observation, which can be attributed to the preserved control during the heating conditions, of the powders through the LVOF process. Figure 7e shows the EDS elemental mapping analysis, where it was identified uniform and homogeneous elemental distribution for Co, Si, Mo, S, which were followed with less homogenous of Cr and O, this resulted from the possible formation of oxides.

Figure 7.

Surface of Co-based coating on Inconel 718 substrate, at spray distance of 8 cm and 55/40 gas ratio: (a) splats and splash zones, (b) semi-molten particles, (c) semi spherical particles, (d) oxides, (e) EDS mapping spectroscopy elemental maps, spray distance at 8 cm.

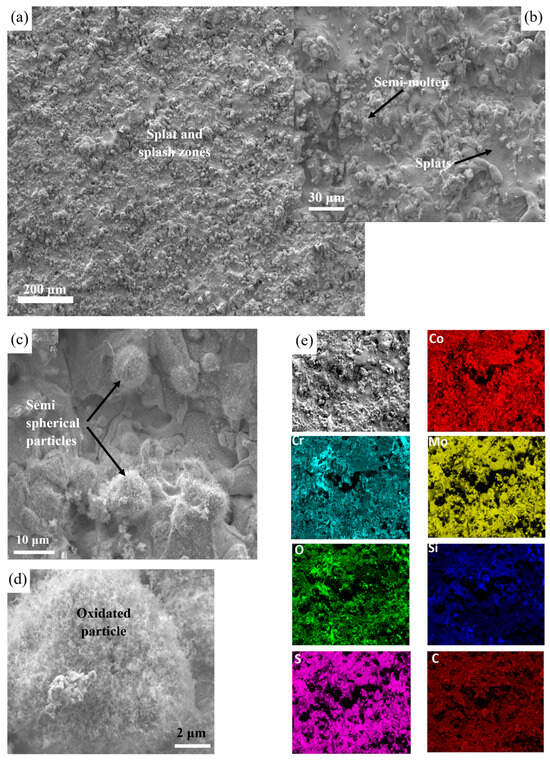

3.3.2. SEM Analysis Coating for Gas Ratio of 55/40 and Thermal Spray Distance of 9 cm

Figure 8a–d show micrographs taken from the coating developed at a thermal spray distance of 9 cm. A close view of these figures shows splats and rough regions, along with small spherical particles. Figure 8e shows the EDS mapping elemental analysis for the thermal spray distance of 9 cm, with uniform and homogeneous elemental distribution for Co, Si, and Mo, followed by S and C, but less uniform for Cr and O. From the figures, it was possible to observe quality improvements of microstructure coatings. At this thermal spray distance, large splash areas were obtained with less rugged zones, and the number and size of semi spherical particles decreased. These particles formed a fine microstructure composed of splats of around 40 µm in size. Nonetheless, semi-molten powders on the surface, large agglomerates, and cracking splats were not observed. Therefore, this thermal spray distance and gas ratio conditions correspond to better conditions of the LVOF process on Inconel 718 substrates. Although the EDS analysis revealed the presence of Cr-O elements, these likely originate from smalls aggregates found around the splats.

Figure 8.

Surface of Co-based coating on Inconel 718 substrate at spray distance of 9 cm and 55/40: (a) rugged, gravel, splat, and splash zones, (b) semi-molten particles, (c) smooth zone, (d) oxides, and (e) EDS mapping spectroscopy elemental maps.

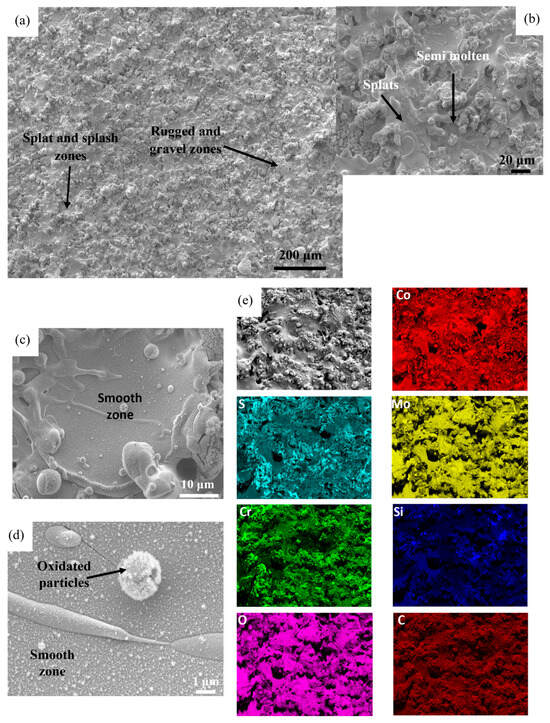

3.3.3. SEM Analysis Coating for Gas Ratio of 55/40 and Thermal Spray Distance of 11 cm

Figure 9a–d show the surface of the developed coating, illustrating examples of rough and splat regions developed on the coating manufactured at a thermal spray distance of 11 cm. Based on these micrographs, it was observed that a spray distance of 11 cm and gas ratio of 55/40 showed predominance of rugged areas, with large agglomerates, and smaller splat areas. It was also observed that this thermal spray condition promoted the cooling of the superalloy powders during the deposition. At this spray distance, a large number of semi-spherical particles, and the formation of flower-like splat features, was observed. Figure 9e shows the EDS mapping elemental analysis for the thermal spray distance of 11 cm. It also shows a uniform and homogeneous elemental distribution for Co, Si, and Mo, followed by S, and with less uniformity for Cr and O chemical elements. The formation of chromium oxides was also identified. Upon the microscopy characterization of the coatings produced by LVOF, it was observed that the employed gas ratio allowed to obtain semi-fusion states of Co-based powders.

Figure 9.

Surface of Co-based coating on Inconel 718 substrate at a spray distance of 11 cm and 55/40 cm: (a) splats, splash, rigged, and gravel zones, (b) semi-molten particles, (c) semi-molten zone, (d) oxides, and (e) EDS mapping spectroscopy elemental maps.

Hence, the resulting coating microstructures were composed mainly of morphologies of splats and rugged zones. However, the presence of agglomerates, semi-molten particles, and small powders evidenced heterogenous features on the coating. In summary, it can also be observed that a spray distance of 11 cm promoted the formation of agglomerates (gravel-mounted) with size of around 100 µm. And small spray distances promote the formation of rugged zones. In the same sense, a high gas ratio allowed melting and the formation of large splash zones, with chemical composition of enriched zones in Cr-O elements. These zones are present around edge splats for each gas ratio. Nevertheless, the formation of cracking of the splats in the coating was not observed, indicating that the developed coatings were not damaged. Thus, rugged and gravel-mounted splats would affect the presence of porosity in the bulk coatings. Moreover, between layered splats, in the first splat-substrate layer, inter-splat pores can exist. In this sense, the contact region between layered splats determines coating properties, such as thermal conductivity and Young’s modulus. On the other hand, adhesive strength would increase with the increase in a ratio of disk splats.

3.4. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

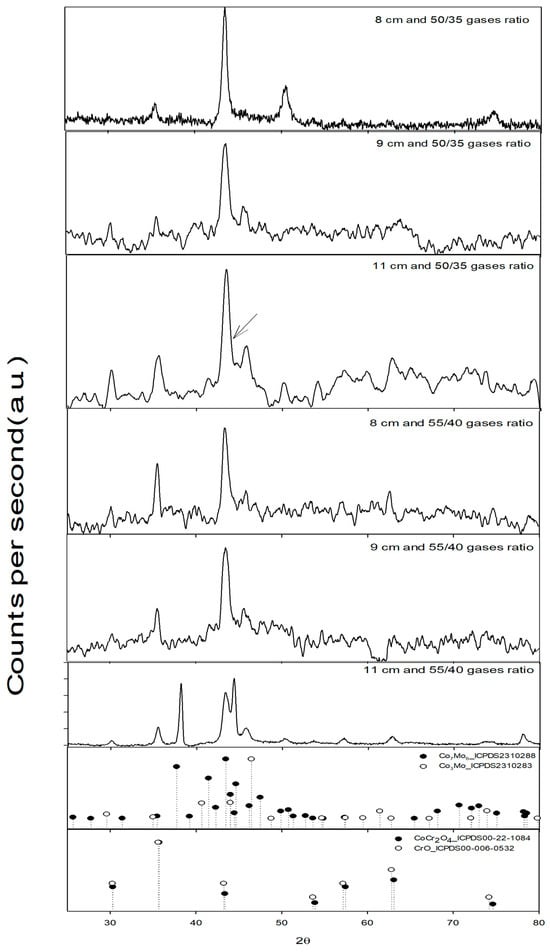

X-ray diffraction analyses were also performed in order to identify the crystal structure of the developed hard coatings for the different gas ratios and spray distances of the LVOF process. Figure 10 shows the X-ray analysis for thermal spray distances of 8, 9, and 11 cm and gas ratios of 50/35 and 55/40, respectively. From Figure 10, the crystallographic composition was observed for spray distances of 8 cm, 9 cm, and 11 cm, with a gas ratio of 35/50. In these figures, two cobalt phases Co7Mo6 and Co3Mo were mainly identified, with ICSD indexed patterns 03-065-8115 and 23-102-83, respectively.

Figure 10.

X-ray diffraction patterns for projection distances of 8 cm, 9 cm, and 11 cm and gas ratios of 50/35 and 55/40, respectively.

These phases correspond well to the matrix composition, as it was also indexed for Co-based powders. Nevertheless, two oxide phases of CoCr2O4, and CrO were identified, with ICSD 00-22-1084 and 00-006-0532 patterns indexed, respectively. These oxide phases evidenced the degree of oxidation that presented Co-based powders when exposed to a gas ratio of 55:35 acetylene/oxygen. Figure 10 also shows the X-ray analysis for the thermal spray distances of 8 cm, 9 cm, and 11 cm, with a gas ratio of 55/40 (acetylene/oxygen).

From these patterns, a crystallographic composition corresponding to cobalt phases and Co alloy matrix was observed. In the case of Figure 10, the X-ray analysis for thermal spray distance of 11 cm and a gas ratio of 35/50 is also shown. A Co2Mo3 phase can also be observed, and once again, the formation of CoCr2O4, and CrO oxide phases was identified. From the different thermal spray distances and gas ratios performed in the present section, the presence of oxide phases for all thermal spray conditions was also observed. Then, these oxides were preferentially presented for a spray distance of 11 cm for all gas ratios. Rietveld analysis was also performed on all coatings. Here, the CrO2 pattern was selected to assess the increase in oxide phase relations presented in each coating. Therefore, for all gas ratios employed in the present study, the formation of a Co-based coating in a reduced atmosphere resulted in a better splat morphology and lower oxide formation, as observed for a gas ratio of 55/40 and thermal spray distance of 9 cm.

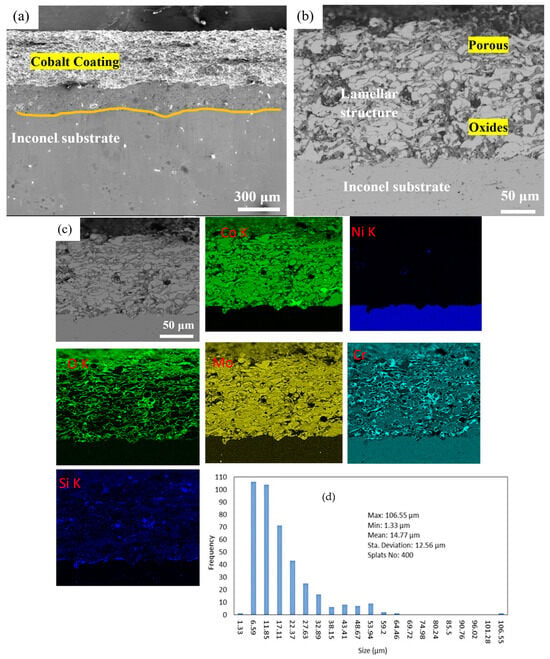

3.5. Cross-Section Analysis of the Co-Based Coating

Following microstructural surface analyses, cross-section analyses of Co-based coatings were performed. For the coatings developed with a gas ratio of 55/40 and thermal spray distances of 9 cm and 11 cm were selected, as these distances were identified as the better thermal spray distance conditions. These thermal spray conditions were associated with the best coating microstructure performance.

Figure 11 shows micrographs of the cross-section of the coating sprayed at 9 cm, and from the figure, the presence of lamellas, homogeneously distributed through the thickness of the coating, is clearly observed. The formation of porosity, with a value of 15% and constituting of small pores located between the lamellas with acicular morphology, was also observed. Moreover, the presence of round morphologies, which are the resultant of semi-molten powders, was observed, but these are scarcely present through the complete thickness of the coating. In addition, the performed EDS mapping analysis showed Co, Mo, Ni, O, and Cr elemental distribution through the thickness of the coating, as clearly observed in Figure 11c.

Figure 11.

(a) Coating sprayed with a gas ratio of 55/40 and a thermal projection distance of 9 cm; (b) transversal-section detailed SEM analysis; (c) EDS mapping analysis; (d) size distribution of lamellar structures.

The performed EDS analysis additionally showed the presence of zones rich in oxygen associated with rich zones of Cr chemical element, corresponding well to the location of oxidized species formed through the thickness of the coating. The formation of these oxide phases was evidenced by the X-ray analysis. It has been observed that the real interface between the lamellas and the substrate, previously deposited inside lamellar layers, presented strong adherence to the substrate due to the preheating temperature being above the transition temperature, which also increased the adhesion properties of the coatings.

Thus, this preheating has been carefully controlled to limit as much as possible the development of oxide layers on the alloy substrate surface. The BSEM observed in Figure 11c shows that the EDS analysis did not show the presence of any oxide layer. Figure 11d shows the size distribution of the formed splats in the coatings. Hence, the proper performance of the coatings can be clearly associated with the formation of their characteristic microstructure.

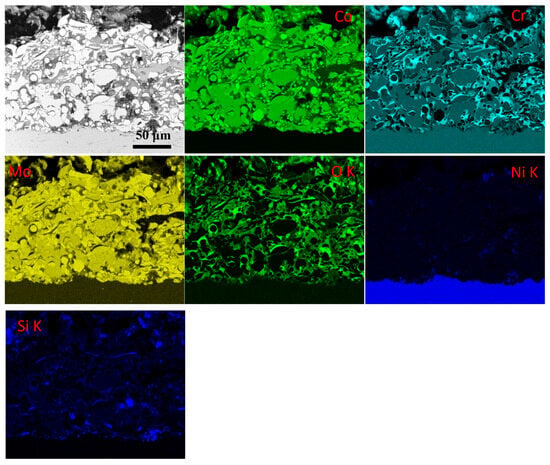

Figure 12 shows the elemental mapping analysis of the coatings. In the figure, the segregation of Cr and O chemical elements is clearly observed in the performed EDS mapping analysis, which can be associated with the formation of oxidized species, along with the presence of phases riche in Co and Mo. Figure 12 also shows a coating developed with a gas ratio of 55/40 and a thermal projection distance of 11 cm. From the figure, two zones, appearing in gray and white with sizes of several microns, were also identified, with the acicular zones corresponding to oxides and the round forms attributed to semi-molten spherical powders.

Figure 12.

EDS mapping analysis of a coating sprayed at a gas ratio of 55/40 and a thermal projection distance of 11 cm.

In addition, inter-lamellar flat pores were observed as thin voids orthogonal to the spray direction, filling spaces between the lamellas. These inter-lamellar pores correspond to the coating porosity, with thickness ranging from a few hundredths to a few tenths of microns. Figure 12 also shows the interface of layered lamellar with Inconel 718 substrate, highlighting the inter-lamellar contacts.

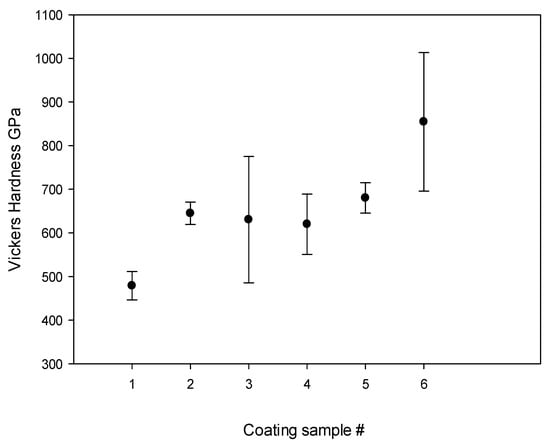

3.6. Vickers Hardness Tests

In this section, micro-hardness tests were carried out to measure the hardness properties of the developed Co-based coatings on substrates of Inconel 718. In order to perform the tests, the tester machine was revised to be calibrated, and it was verified that the hardness test machine was recently calibrated according to ISO-6507 standards [34].

In Vickers micro-hardness testing, a mass of two kilograms was applied to create the diamond indentation, characteristic of this type of tests. For the tests, a Mitutoyo model AVK-C2 micro-hardness tester machine was employed. The tests were carried out following the standard recommendations reported in the literature [34,35]. The results showed high scatter in terms of Vickers hardness values for each coating condition. Figure 13 shows the measured Vickers hardness values for the different coatings developed with the flame thermal spray process. From the figure, it can be observed that the Vickers hardness values did not present a great variation, which can be attributed to the calibrated process conditions of the gas ratio and spray distance during the application of the coatings. Therefore, during the Vickers hardness tests, the test machine tested regions with quite similar hardness values, as observed in Figure 13. Therefore, the present thermal spray process allowed to obtain homogeneous coating microstructure with homogeneous mechanical properties.

Figure 13.

Vickers values for each coating sample: 1–3 for 50/35 gas ratio; 4–6 for 55/40 gas ratio.

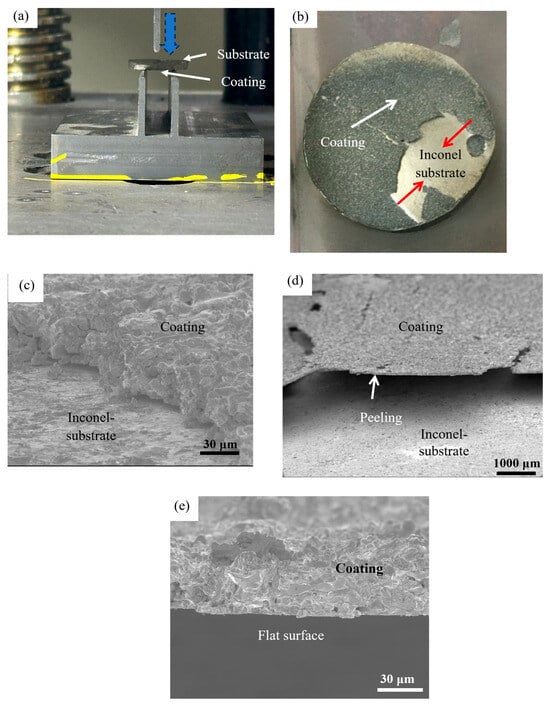

Bend tests were also performed to analyze the fracture mechanisms of the coatings. Figure 14a shows the experimental setup for bending tests of coating-substrate samples, with a coating manufactured at a gas ratio of 55/40 and a thermal spray distance of 11 cm. Figure 14b depicts a sample after the bending test was carried out. The figure also shows the coating and Inconel substrate after flexion, the detachment of the coating from the substrate, and coating rupture with a small level of plasticity. This can be associated with the hard properties of the coating and thickness size. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the detached coating from Inconel 718 substate did not present cracking. Nonetheless, the presence of oxides promoted coating failure. Figure 14c–e show micrographs with large magnification of substrate interface regions, and a close view showed that some coating splats remained on the substrates, confirming the good adherence properties of the developed coatings. The figure also shows that Inconel 718 substrate experienced higher plastic deformation, compared with the coating, which occurred because the hardness of the coatings is higher. It is also important to observe that the unattached coating seems to be axisymmetric with the center line, taken at the symmetry axis. And when the distance between the position and the central part is long enough, no spallation initiates with the applied load (as shown in Figure 14b). A cross-section of a coating developed at a gas ratio of 55/40 and at a thermal spray distance 11 cm after the bending test is shown in Figure 14c. The figure depicts how the substrate coating was bended, and it also shows the thickness of the coating, which is 50 µm. During bend testing, it was observed that the coating presented some level of plastic deformation under three-point bending load (3PB) and cracks at the center of the cross-section, which ran and broke the coating. The rupture of the coating in several pieces is shown in the figure, attributed to the extreme pressure that occurred in the lower grips region of the testing machine, as can be clearly observed by the red marks in Figure 14b.

Figure 14.

Micrographs of Co-based coating-substrate in flexion test for 55/40 gas ratio and 11 cm: (a) bend testing setup (blue arrow indicating direction of the pushing movement), (b) coating cracking, and (c–e) fracture mechanisms.

3.7. Fractography Analysis of the Cross-Section of Co-Based Coating

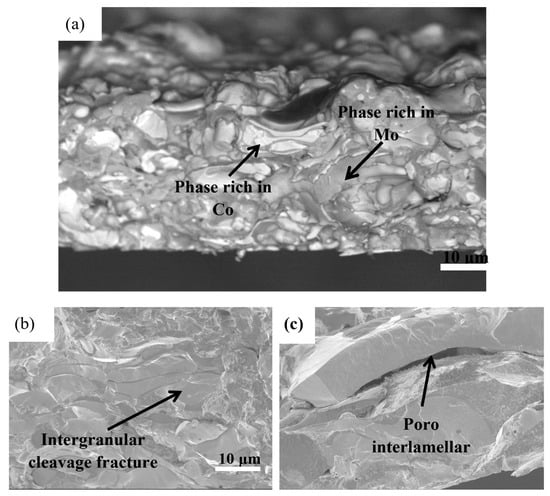

Horizontal spallation initiated at the substrate/bonding interface, and the coating eventually failed at the central part of the substrate/coating interface. From the cross-section figure of the coating-substrate, obtained at a gas ratio of 55/40 and at a thermal spray distance 11 cm, as shown in Figure 15a, some microcracks perpendicularly to the coating were observed.

Figure 15.

Micrographs of Co-based cross-section coating-substrate sample at a 55/40 gas ratio and 11 cm spray distance: (a) after bending testing, showing zones rich in Co and Mo, (b) cleavage fracture, and (c) porous beneath the cleavage zone.

A short-sized microcrack was also found near the coating surface. Therefore, it can be assumed that microcrack nucleation occurred during bending, at the substrate/coating interface. Therefore, a competition between the porosity and microcracks, under some level of plasticity in the coating, is involved during the break process. Figure 15b shows crack propagation through the lamella’s microstructure. A distortion zone of fracture morphology is shown in Figure 15c, which can show that Co-based coatings experience microcrack nucleation under low plastic deformation, followed by propagation. Additionally, lamellas cracking was observed in regions rich in Co, suggesting that lamellas with flat morphology and rich in cobalt microparticles, can cleavage the coating’s microstructure. Nonetheless, some molten zones showed a quasi-ductile behavior, with small dimples or pool morphologies. Nevertheless, because the analysis of fracture nucleation and propagation mechanisms are not the object of the present work, the fracture behavior of Co-based powders coatings will be studied in a future work and submitted for publication.

4. Conclusions

This work presented a parametric analysis on the development of hard coatings with Diamalloy 3001 metallic superalloy powders through a calibrated LVOF process. The effects of both stoichiometric gas ratio and spray distances were analyzed and linked to the microstructure and oxide species formed in the thermally sprayed coatings. Thus, a spray distance of 9 cm was identified as the best thermal spray condition to spray the Co-based powders, resulting in a more homogeneous coating microstructure.

- The performed EDS and X-ray diffraction analyses showed decrement of oxidized species when a neutral gas ratio was used, with a fixed thermal spray distance of 9 cm. For this last condition, the coatings presented better morphologies such as splat powders with an average size of 50 µm, although a rugged surface with a slight oxide species decrease was observed.

- The coatings developed had a thickness of 500 µm and were constituted by a lamellar morphology, with lamella sizes in the range 20 µm and small presence of oxides rich in Co. Small pores with acicular morphologies, with a size of 10 µm and corresponding to about 15% of the matrix microstructure, were presented in all the coatings. The measured Vickers hardness values were in the range of 900 Hv, which showed quite homogeneous values and provided a homogenous coating microstructure.

- The bending tests showed that the coatings presented a quasi-brittle behavior, and some level of plasticity was required to created microcracks before catastrophic propagation. In the cross-section of the coating, microcracks were also observed perpendicular to the overlay coating after bending tests, along the coating-substrate interface. And crack propagation was observed to run through the lamella’s microstructure and regions with chemical composition of oxidized species rich in Cr, which are hard. Finally, it can be observed that the developed hard coatings on Inconel 718 substrates, produced via the calibrated LVOF process, presented good microstructural and mechanical properties, which were achieved by the proper calibration of the gas ratio, thermal spray distance, pre-heating temperature, and the defined time of each thermal spray shot.

Author Contributions

Methodology, F.J.-L.; Validation, Á.d.J.M.-R.; Formal analysis, R.C.-M.; Investigation, M.V.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Comisión de Fomento de Actividades Académicas COFAA; Estimulo al Desempeño de los Investigadores (EDI); Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI); and, especially, México Postdoctoral Stays 2022 (3) No. I1200/320/2022 for the provided support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Farhat, H. Operation, Maintenance, and Repair of Land-Based Gas Turbines; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; ISBN 978-0-12-821834-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, R.K.; Thomas, J.; Srinivasan, K.; Nandi, V.; Bhatt, R.R. Investigation of HP turbine blade failure in a military turbofan engine. Int. J. Turbo Jet Engines 2015, 34, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Classification Society. Guidelines for Certification of Subsea Production System; China Classification Society: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- American Bureau of Shipping. Guide for Classification and Certification of Subsea Production Systems Equipment and Components; The American Bureau of Shipping: Spring, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ce, N.; Paul, S. thermally sprayed aluminum coatings for the protection of subsea risers and pipelines carrying hot fluids. Coatings 2016, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blink, J.; Farmer, J.; Choi, J.; Saw, C. Applications in the nuclear industry for thermal spray amorphous metal and ceramic coatings. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2009, 40, 1344–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannuzzi, M.; Barnoush, A.; Johnsen, R. Materials and corrosion trends in offshore and subsea oil and gas production. Mater. Degrad. 2017, 1, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermetico. Depositing Alloyed HVAF Coatings onto Complex Surfaces of Manifolds, Kermetico HVAF and HVOF Thermal Spray Equipment, 2024. Available online: https://kermetico.com/applications/h2s-resistant-coating-vessel-corrosion (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Amin, S.; Panchal, H. A review on thermal spray coating processes. Int. J. Curr. Trends Eng. Res. 2016, 2, 556–563. [Google Scholar]

- Lirong, L.; Ying, C.; Xiaofeng, Z. Thermal barrier coatings. In Strategies for Improving the Lifetime of Air Plasma Sprayed Thermal Barrier Coatings, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 325–360. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y. Characterization and Mechanical Properties for Diamalloy 3001 and Diamalloy 3002NS Thermally Sprayed Coatings. Master’s Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Munagala, V.N.V.; Alidokht, S.A.; Sharifi, N.; Makowiec, M.E.; Stoyanov, P.; Moreau, C.; Chromik, R.R. Room and elevated temperature sliding wear of high velocity oxy-fuel sprayed Diamalloy3001 coatings. Tribol. Int. 2023, 178, 108069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanicchia, F.; Maeder, X.; Ast, J.; Taylor, A.A.; Guo, Y.; Polyakov, M.N.; Michler, J.; Axinte, D.A. Residual stress and adhesion of thermal spray coatings: Microscopic view by solidification and crystallization analysis in the epitaxial CoNiCrAlY single splat. Mater. Des. 2018, 153, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Kamnis, S. Bonding mechanism from the impact of thermally sprayed solid particles. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2009, 40, 2664–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuamatzi-Meléndez, R.; Juárez-López, F.; Morales-Ramírez, Á.d.J.; Rivas-Robles, F.G. Cobalt-Base/Molybdenum/Chromium/Silicon Superalloys Coatings on Pipeline Steel Substrates, Microstructural, Bonding and Mechanical Properties Characterization. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2025, 34, 3476–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Mendoza, M.; Morado-Rueda, C.E.J.; Sánchez, A.M.; López, F.J. Thermal cyclic oxidation of NiCoCrAlYTa coatings manufactured by combustion flame spray. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 25, 101617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, E.C.; Velásquez, C.P.; Galvis, F.V. Estudio de llamas oxiacetilénicas en la proyección térmica. Rev. Colomb. Mater. 2016, 9, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- ESAB Company. Oxy-Fuel Torch Preheat and Its Proper Adjustment; ESAB: North Bethesda, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, M.Y.F.; Téllez, C.M.M.; Galvis, F.V. Recubrimientos de Circonia y Alúmina por Proyección Térmica con Flama; Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia: Tunja, Colombia, 2018; Editorial UPTC ISBN-13. [Google Scholar]

- Idir, A.; Delloro, F.; Younes, R.; Bradai, M.A.; Sadeddine, A.; Benabbas, A. Microstructure and tribological behaviour of NiWCrBSi coating produced by flame spraying. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2022, 123, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idir, A.; Delloro, F.; Younes, R.; Bradai, M.A.; Sadeddine, A.; Benabbas, A. Microstructure analysis and mechanical characterization of NiWCrBSi coatings produced by flame spraying. Metall. Res. Technol. 2022, 119, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idir, A.; Delloro, F.; Younes, R.; Bradai, M.A.; Sadeddine, A.; Benabbas, A. Tribological performance of thermally sprayed NiWCrBSi alloy coating by two different oxyacetylene flame stoichiometries. Trans. IMF 2021, 99, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idir, A.; Delloro, F.; Younes, R.; Bradai, M.A.; Sadeddine, A.; Marginean, G. Comparative study of corrosion performance of LVOF-sprayed Ni-Based composite coatings produced using standard and reducing flame spray stoichiometry. Materials 2024, 17, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanicchia, F.; Axinte, D.A.; Kell, J.; McIntyre, R.; Brewster, G.; Norton, A.D. Combustion flame spray of CoNiCrAlY & YSZ. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 315, 546–557. [Google Scholar]

- Boakye, G.O.; Geambazu, L.E.; Ormsdottir, A.M.; Gunnarsson, B.G.; Csaki, I.; Fanicchia, F.; Kovalov, D.; Karlsdottir, S.N. Microstructural properties and wear resistance of Fe-Cr-Co-Ni-Mo-based high entropy alloy coatings deposited with different coating techniques. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hango, S.I.; Cornish, L.A.; van der Merwe, J.W.; Chown, L.H.; Kavishe, F.P. Corrosion behaviour of cobalt-based coatings with ruthenium additions in synthetic mine water. Results Mater. 2024, 21, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branzoi, F.; Mihai, A.M.; Zaki, M.Y. Anticorrosion Protection of New Composite Coating for Cobalt-Based Alloy in Hydrochloric Acid Solution Obtained by Electrodeposition Methods. Coatings 2024, 14, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Le, H.; Fu, T.; Zhu, D. Effect of carbides on the electrochemical dissolution behavior of solid-solution strengthened cobalt-based superalloy Haynes 188 in NaNO3 solution. Corros. Sci. 2023, 220, 111270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Mehta, A.; Vasudev, H.; Samra, P.S. A review on the design and analysis for the application of Wear and corrosion resistance coatings. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. (IJIDeM) 2024, 18, 5381–5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauchais, P.L.; Heberlein, J.V.; Boulos, M.I. Thermal Spray Fundamentals from Powder to Part; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; p. 2013956523. ISBN 978-0-387-28319-7/978-0-387-68991-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauchais, P.; Vardelle, A.; Vardelle, M. Knowledge concerning splat formation: An invited review. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2004, 13, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, R.; McDonald, A.G.; Chandra, S. Predicting splat morphology in a thermal spray process. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2007, 201, 7789–7801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, N. Notomi Proceedings paper, The splat morphology of plasma sprayed particle and the relation to coating property. In Proceedings of the International Thermal Spray Conference, Montreal, Canada, 8–11 May 2000; pp. 753–758. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 6507-1; Metallic Materials-Vickers Hardness Test-Part 1: Test Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997.

- ASTM E 92-82; Standard Test Method for Vickers Hardness of Metallic Materials. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1997.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.