Abstract

Concrete structures in western saline soil regions are subjected to extreme environments with coupled dry-wet cycles and high concentrations of erosive ions such as Cl−, SO42−, and Mg2+, leading to severe degradation of mechanical properties. This study employed a simulated accelerated, high-concentration solution (Solution A, ~8× seawater salinity) similar to the composition of actual saline soil to perform accelerated dry-wet cycling corrosion tests on ordinary C40 concrete specimens for six corrosion ages (0, 5, 8, 10, 15, and 20 months). For each age, three replicate cube specimens were tested per property. The changes in cube compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, prism stress–strain full curves, and microstructure were systematically investigated. Results show that in the initial corrosion stage (0–5 months), strength exhibits a brief increase (compressive strength by 11.87%, splitting tensile strength by 9.23%) due to pore filling by corrosion products such as ettringite, gypsum, and Friedel’s salt. It then enters a slow deterioration stage (5–15 months), with significant strength decline by 20 months, where splitting tensile strength is most sensitive to corrosion. Long-term prediction models for key parameters such as compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, elastic modulus, peak stress, and peak strain were established based on grey GM(1,1) theory using the measured data from 0 to 20 months, achieving “excellent” accuracy (C ≤ 0.1221, p = 1). A segmented compressive constitutive model that considers the effect of corrosion time was proposed by combining continuous damage mechanics and the Weibull distribution. The ascending branch showed high consistency with the experimental curves. Life prediction indicates that under natural dry-wet cycling conditions, the service life of ordinary concrete in this region is only about 7.5 years when splitting tensile strength drops to 50% of initial value as the failure criterion, far below the 50-year design benchmark period. This study provides reliable theoretical models and a quantitative basis for durability design and life assessment of concrete structures in western saline soil regions.

1. Introduction

Western China (Qinghai Qaidam Basin, Gansu Hexi Corridor, Xinjiang Lop Nur, southern Xinjiang, etc.) is widely distributed with highly salinized soils, where the surface layer of 0–30 cm soil has Cl− content up to 108.64 g/L, SO42− up to 36.44 g/L, and total salt content up to 278.96 g/L, far exceeding seawater, making it one of the most severe salt-affected areas in the world [1,2]. Meanwhile, this region has typical dry-wet alternating climate characteristics, with dry and low rainfall in spring and winter, and concentrated rainfall in summer and autumn, causing soil salts to repeatedly crystallize-dissolve-recrystallize with water migration, producing strong coupled physical salt expansion and chemical corrosion damage. Extensive engineering surveys show that local highways, railways, transmission tower foundations, and industrial plants commonly exhibit severe cracking, spalling, and strength loss after only 5–10 years of service [3,4,5]. Their actual service life is far below the 50-year design benchmark, becoming a major technical bottleneck for infrastructure longevity along the “Belt and Road”.

Existing research on concrete durability in saline soil regions mostly focuses on single sulfate [6] or chloride [7] erosion, or continuous immersion conditions [8], while the most destructive in actual engineering is the coupled effect of “dry-wet cycles + multi-ion composite erosion”. Dry-wet cycles significantly accelerate capillary migration and crystallization expansion of salts into concrete, promoting rapid formation of corrosion products such as ettringite, gypsum, Friedel’s salt, and Mg(OH)2, generating huge expansion stresses and leading to early initiation and propagation of microcracks [9,10]. Tests show that under the same total salt content, dry-wet cycling can increase strength loss in concrete within 20 months by 30%–80% compared to full immersion [11]. Therefore, results based solely on continuous immersion or single salts fail to truly reflect the damage laws in western saline soil regions.

The selection of the grey GM(1,1) model for this study is based on the distinct characteristics of concrete degradation in saline soil environments under dry-wet cycles. First, the process involves complex, coupled physicochemical mechanisms (pore filling, crystallization pressure, decalcification) that shift over time, rendering purely mechanistic models difficult to formulate and calibrate without extensive, long-term data [12]. Second, while traditional statistical time-series methods (e.g., ARIMA, exponential smoothing) often require larger datasets and assume certain data distributions [13,14], the accelerated test here yields only a limited sequence of six observations. The GM(1,1) model is specifically designed for such “small-sample, poor-information” scenarios, requiring a minimum of only four data points to build a predictive model [15]. More importantly, it does not presume a fixed probability distribution or a pre-defined functional form (linear, exponential, etc.), allowing it to capture inherent non-monotonic trends—such as the initial strength increase followed by decay—that are often missed by conventional regression [16]. Its prior successful applications in modeling concrete carbonation, sulfate attack, and chloride ingress under data-limited conditions further support its appropriateness for the present multi-ion coupled corrosion problem [17,18,19].

Current research on the evolution laws of concrete stress–strain full curves and long-term constitutive relationships under dry-wet cycles + multi-ion composite erosion in western saline soil regions remains insufficient. Existing constitutive models are mostly based on non-corroded or single erosion environments and fail to reflect features such as significantly enhanced brittleness after corrosion, rapid post-peak drop, and sharp loss of residual bearing capacity [20]. Meanwhile, there is a lack of quantitative models combining grey prediction with damage mechanics that can extrapolate to natural environment service life, leading to an inability to accurately assess remaining life and formulate targeted protective measures at the design stage.

To this end, this paper takes C40 ordinary concrete as the object, using a solution similar to the chemical composition of typical saline soil in the Qaidam Basin for accelerated dry-wet cycling corrosion tests (immersion 15 days + drying 15 days) for 0, 5, 8, 10, 15, and 20 months, systematically studying the evolution laws of cube compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, prism stress–strain full curves, and microstructure; establishing long-term prediction models for strength and characteristic parameters based on grey GM(1,1) theory; proposing a segmented compressive constitutive model considering corrosion time combining continuous damage mechanics and Weibull distribution; and extrapolating to predict service life under natural environments. The research results can provide reliable theoretical basis and quantitative tools for durability design, remaining life assessment, and maintenance decisions of concrete structures in western saline soil regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

According to Chinese standard [21], the cement used is P.O 42.5R ordinary Portland cement, with density 3.15 g/cm3, specific surface area 384 m2/kg, standard consistency water requirement 26.8%, initial setting 240 min, final setting 390 min, 3d and 28d compressive strengths 24.8 MPa and 48.9 MPa, respectively. According to Chinese standard [22], fine aggregate is Zone II medium sand, fineness modulus 2.8, apparent density 2600 kg/m3; coarse aggregate is 5–20 mm continuous graded gravel, apparent density 2660 kg/m3, crushing index 8.7%. Mixing and curing water is ordinary tap water. Concrete design strength grade C40, mix ratio as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mix ratio of concrete (kg/m3).

The corrosion solution is prepared based on the ion composition of typical high-saline soil pore water in Qinghai Qaidam Basin (referred to as Solution A), with total salt content about eight times that of seawater, main ion mass concentrations shown in Table 1. Analytical pure grade chemicals, such as NaCl, MgCl2, Na2SO4, MgSO4, CaSO4, and KCl, were used and dissolved in deionized water. The pH was controlled between 7.0 and 7.5.

The composition of Solution A, with a total salt content of approximately 244 g/L (~8× typical seawater salinity of ~35 g/L), was selected to directly replicate the high-salinity pore water in the Qaidam Basin saline soils (Table 2), where Cl− and SO42− concentrations far exceed those in marine environments [1,2]. This elevated concentration accelerates ion diffusion and reaction rates, simulating the intense, coupled physical (crystallization expansion) and chemical (ettringite/gypsum formation, C-S-H decalcification) degradation observed in field surveys of western saline soil regions [3,4,5]. The literature supports the use of high-concentration solutions (5–10× ambient levels) in accelerated tests to compress long-term field exposure into manageable lab durations, as higher ionic gradients proportionally increase erosion kinetics in diffusion-limited processes [23,24]. For instance, studies on sulfate and chloride attack have employed 5–15% salt solutions to achieve acceleration factors of 4–8 relative to natural conditions, enabling prediction of decades-long degradation from months of testing [25,26].

Table 2.

Comparison of main ion concentrations in Solution A and Qaidam saline soil pore water (g/L).

2.2. Specimen Preparation and Test Methods

All specimens were prepared under standard laboratory conditions. For each corrosion age group (0, 5, 8, 10, 15, and 20 months), the following specimens were fabricated: cube specimens (100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm), with three cubes designated for compressive strength tests and another three separate cubes for splitting tensile strength tests; prism specimens (100 mm × 100 mm × 300 mm), with three prisms used for axial compression stress–strain full curve tests; and microstructural analysis specimens (40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm), which were prepared separately and exclusively for microstructural analysis (XRD and SEM). This approach ensured that the observed microstructure remained unaltered by prior mechanical loading. Following curing, the specimens intended for mechanical testing underwent the corrosion cycles and subsequent destructive tests, while the corresponding microstructural specimens were subjected to the same corrosion regimen but reserved solely for post-corrosion microanalysis.

After compaction, the specimens were covered with plastic film. They were demolded after 24 h and subsequently cured in a standard curing room at (20 ± 2) °C and relative humidity ≥ 95% for 28 days. Upon completion of curing, the specimens were immersed in Solution A for 15 days (with the liquid level maintained approximately 30 mm above the specimen top), after which they were removed and allowed to dry naturally in the laboratory for 15 days. This process constituted a complete “immersion 15 days + drying 15 days” dry-wet cycle. Each cycle lasted 30 days, and the tests encompassed 0, 5, 8, 10, 15, and 20 months (corresponding to 0, 5, 8, 10, 15, and 20 cycles), resulting in six corrosion ages.

The selection of a 15-day immersion + 15-day drying cycle (totaling 30 days per cycle) allowed sufficient time for full specimen saturation during the wetting phase (facilitating deep ion penetration and product formation) and complete moisture evaporation during the drying phase (inducing crystallization stresses and microcracking). This regimen mimicked the seasonal dry-wet alternations characteristic of the Qaidam region, including dry/low-rainfall periods in spring and winter, and concentrated precipitation in summer and autumn [3]. Shorter cycles (e.g., 1–7 days) could have underestimated the erosion intensity per cycle due to incomplete reactions, whereas longer cycles (e.g., >21 days) typically exhibit diminishing additional damage, as evidenced by parametric studies on dry-wet periods under sulfate attack [27,28]. This cycle duration was consistent with established literature protocols for accelerated corrosion testing in saline or sulfate environments, where 15-day wet-dry cycles have effectively simulated tidal or seasonal exposures while maintaining experimental efficiency [29,30].

Once the specified corrosion duration was completed, the corresponding specimens were removed, and any surface floating salt was wiped off using a soft cloth. Macroscopic mechanical performance tests were then conducted immediately on these specimens, while the remaining small specimens had their hydration terminated with anhydrous ethanol and were stored in a vacuum drying oven for subsequent microstructural tests.

Cube compressive strength and splitting tensile strength tests were performed in accordance with GB/T 50081-2019 [31] using a 5000 kN pressure testing machine, with loading rates controlled at 0.5 MPa/s and 0.05 MPa/s, respectively. Axial compression stress–strain full curve tests on the prism specimens were conducted using a 1000 kN electro-hydraulic servo universal testing machine with a displacement control rate of 0.2 mm/min. To collect axial deformation data, 100 mm range displacement gauges (LVDT) were symmetrically attached to the mid-sides of the specimens, and strain gauges were pasted on the four mid-faces to monitor lateral deformation, thereby ensuring data reliability. Three preloads (equivalent to 30% of the estimated peak load) were applied for centering prior to formal loading.

For the microstructural tests, XRD analysis was conducted using a German Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany.) with a Cu target, a step size of 0.02°, and a scan range of 5–80°. SEM and EDS examinations were performed with a Japanese JEOL JSM-7900F field emission scanning electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at an acceleration voltage of 15 kV, equipped with an Oxford energy spectrometer (Oxford Instruments plc, Abingdon, UK) for morphology observation and elemental mapping. All microstructural samples were obtained from fresh fracture surfaces 5–10 mm below the specimen surface and observed after vacuum gold plating.

2.3. Grey Theory GM(1,1) Model

Among the various models in grey theory, the GM(1,1) model is the most fundamental. It has only one variable and a first-order grey differential equation, allowing it to predict future data change laws by analyzing existing data. The GM(1,1) model is characterized by low requirements for the size of the known dataset and does not necessitate determining the probability distribution characteristics of the known data, its specific calculation process is as follows [32]:

(1). Represent the original data as a sequence:

Generate the 1-AGO sequence from Equation (1):

Then, the 1-AGO sequence is:

(2). Use Equations (4) and (5) to check the smoothness of the original sequence. If the original data satisfies conditions (4), (5), the original sequence can be considered quasi-smooth.

(3). For

perform quasi-exponential law check, let

. If

, then determine that

satisfies quasi-exponential law and can establish the GM(1,1) model.

(4). Construct the immediate mean sequence

, where

(5). Establish parameter solving equation:

where

,

.

The parameters a and b are solved using the least squares method, where -a and b are defined as the development coefficient and driving coefficient, respectively.

(6). From the whitening equation:

, solve the time response function:

Thus obtain the basic form of GM(1,1) model:

The time response function of the model is:

(7). The simulated value of the accumulated sequence can be calculated by Equation (10), and the simulated value of the original sequence restored by:

(8). Perform model error check, residual expression:

Mean and variance of original data sequence:

Mean and variance of residuals:

Relative error

, posterior variance ratio

, small error probability

.

For evaluating the quality of a prediction model, smaller C is better, generally requiring C < 0.35, maximum not exceeding 0.65. Another indicator of prediction model accuracy is small error probability p; larger p is better, generally requiring p > 0.95, not less than 0.7. According to inspection indicators, model prediction accuracy can be divided into the following four grades [33], see Table 3.

Table 3.

Grey theory model accuracy grades.

3. Strength Variation Laws and Mechanism Analysis

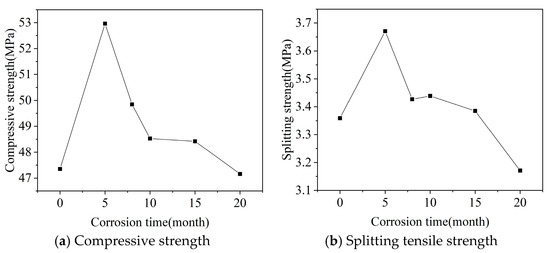

3.1. Cube Compressive Strength and Splitting Tensile Strength

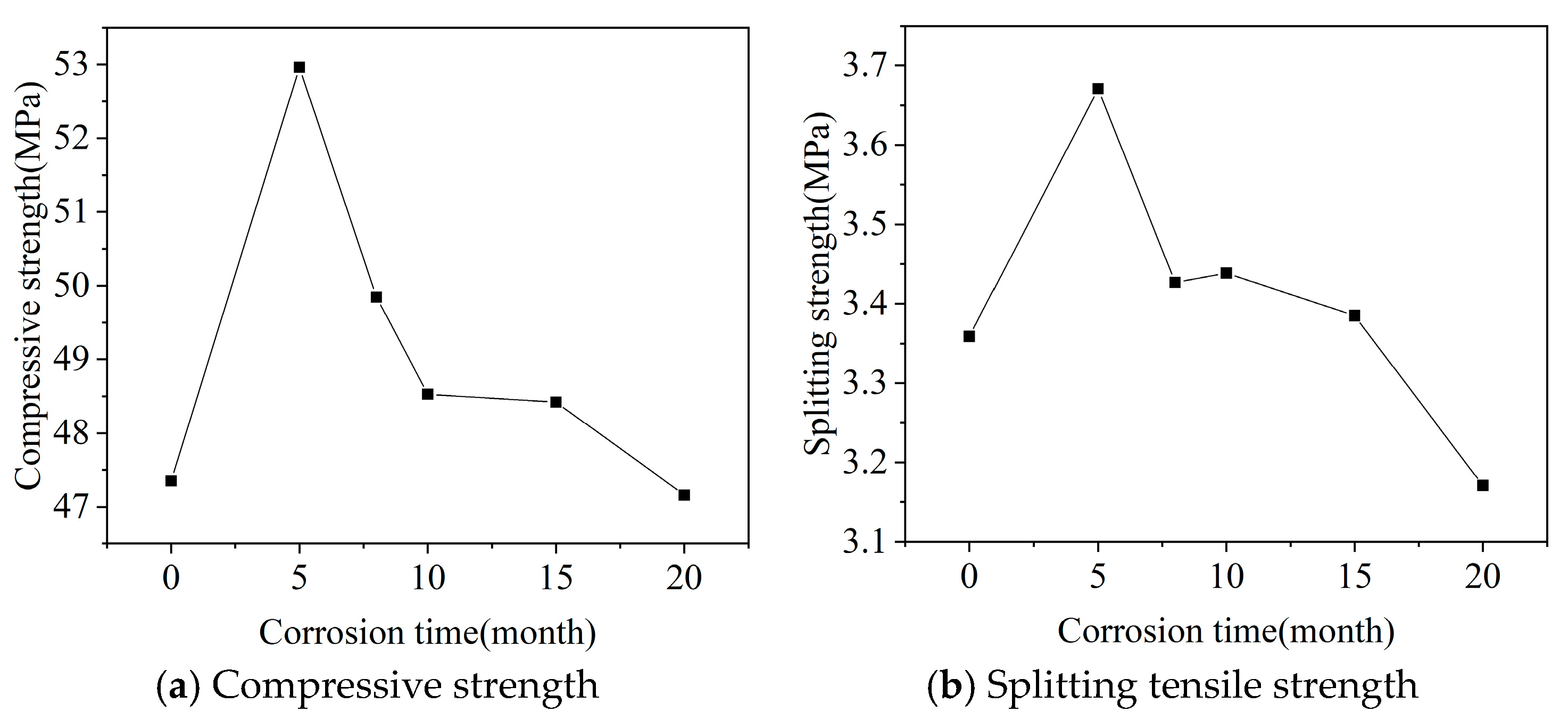

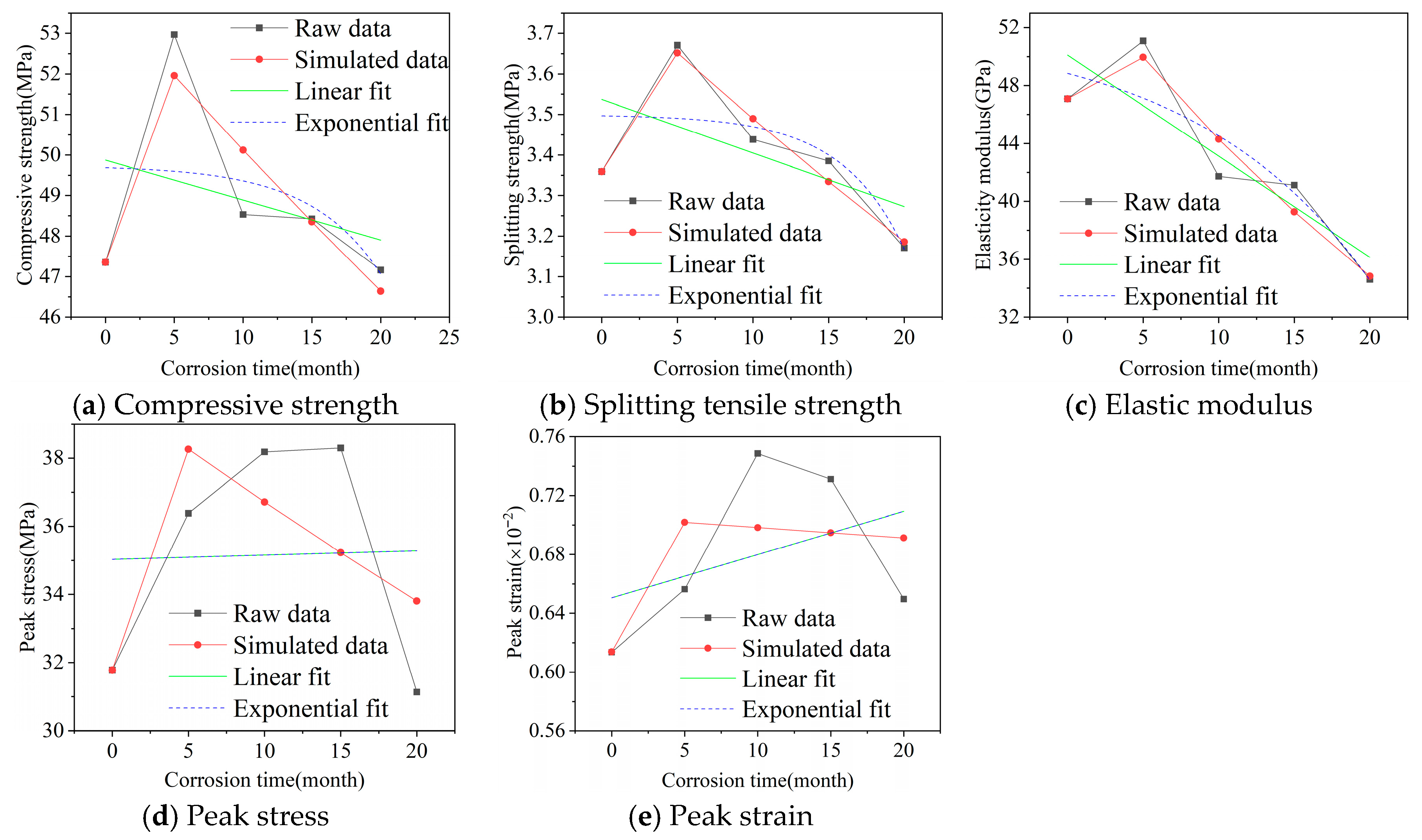

Cube compressive strength and splitting tensile strength of concrete after different dry-wet cycles are shown in Figure 1. From Figure 1a, it can be seen that the cube compressive strength of concrete generally shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing with the increase in dry-wet cycles. The compressive strength of uncorroded specimens is 47.35 MPa, reaching the peak at 5 months with an average strength of about 52.97 MPa, an increase of about 11.87% compared to uncorroded concrete. At 8 months, the compressive strength is 49.85 MPa, a decrease of about 5.89% from the peak; from 8 to 10 months, a decrease of about 2.61%; from 10 to 15 months, little change in strength; at 20 months, compressive strength is 47.16 MPa, a decrease of about 2.6% from 15 months.

Figure 1.

Cube compressive strength and splitting tensile strength of concrete after different dry-wet cycles.

From Figure 1b, it can be seen that the overall change trend of concrete splitting tensile strength with dry-wet cycles is first increasing then decreasing, basically the same as the compressive strength trend. The splitting tensile strength of uncorroded is 3.36 MPa, reaching the peak at 5 months dry-wet cycles, 3.67 MPa, an increase of 9.23% compared to uncorroded, lower than the increase in compressive strength at the same period; after the peak, strength begins to decline, decreasing about 6.54% at 8 months compared to 5 months, higher than the decrease in compressive strength at the same dry-wet cycle; between 8 and 15 months dry-wet cycles, concrete splitting tensile strength is in a stable period, with change amplitude about 1.17%; after 15 months dry-wet cycles, splitting strength shows a second obvious decline, decreasing about 6.49% at 20 months compared to 15 months, also higher than the decrease in compressive strength at the same dry-wet cycle, indicating that cube splitting tensile strength is more sensitive to saline soil environment than cube compressive strength.

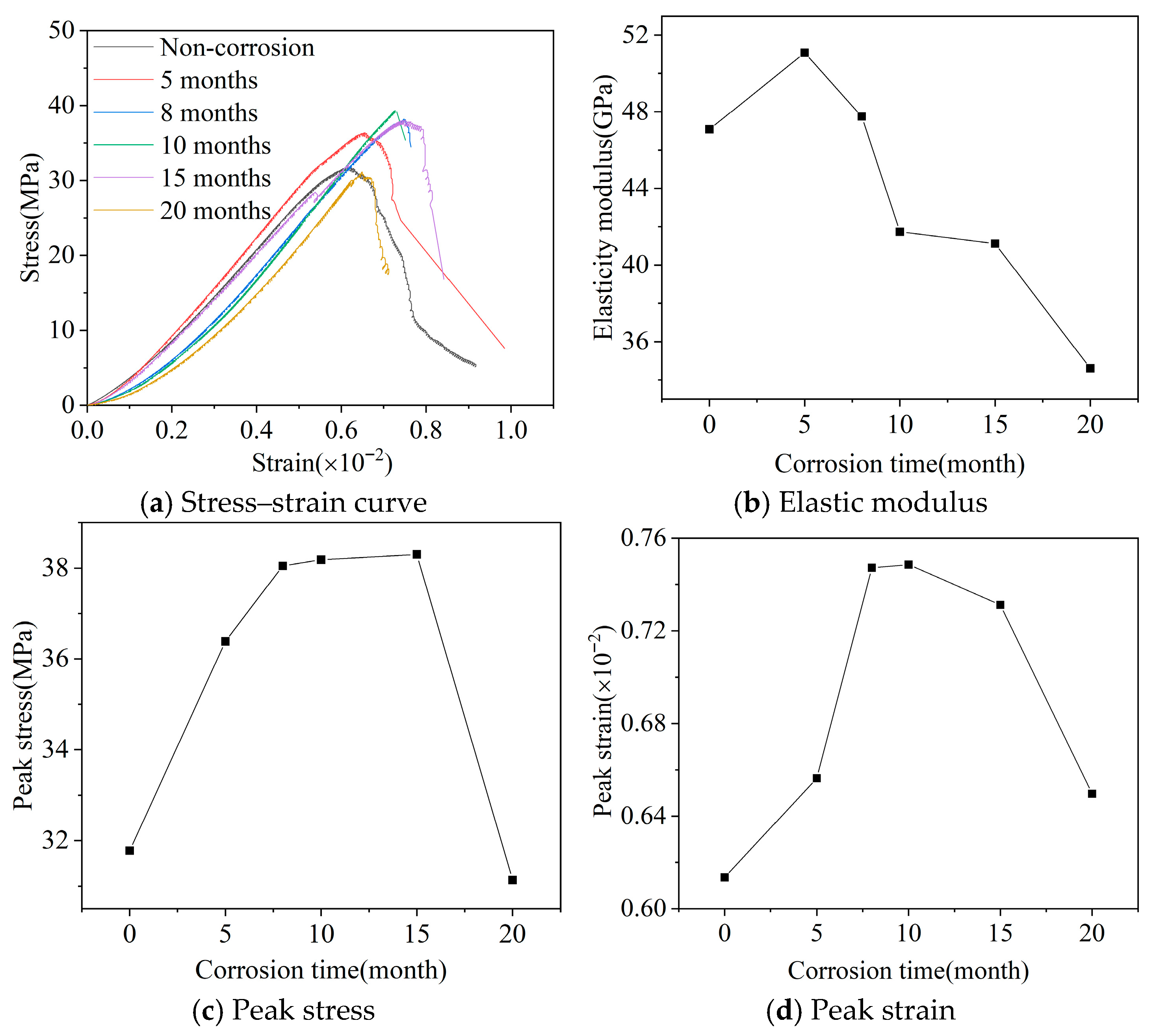

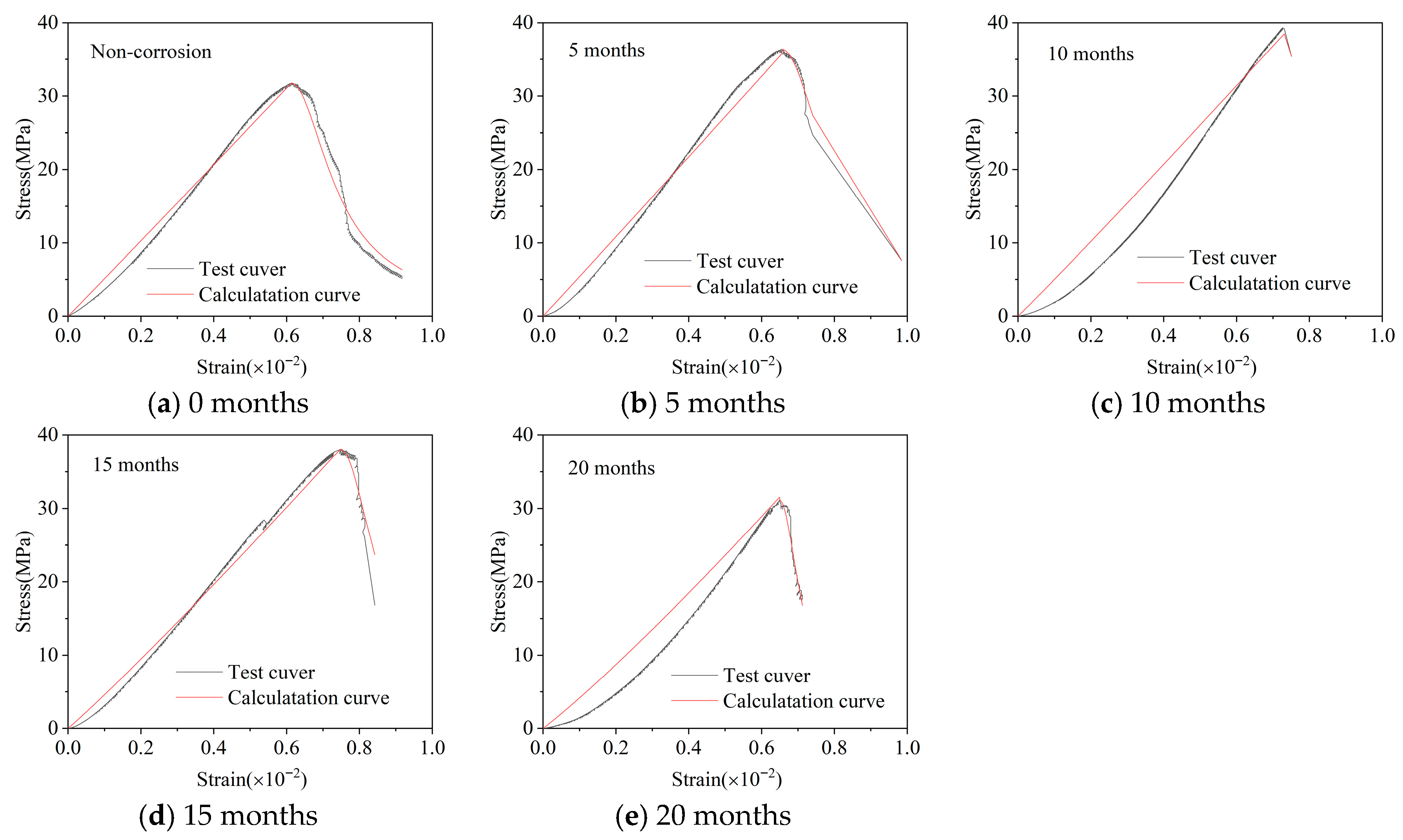

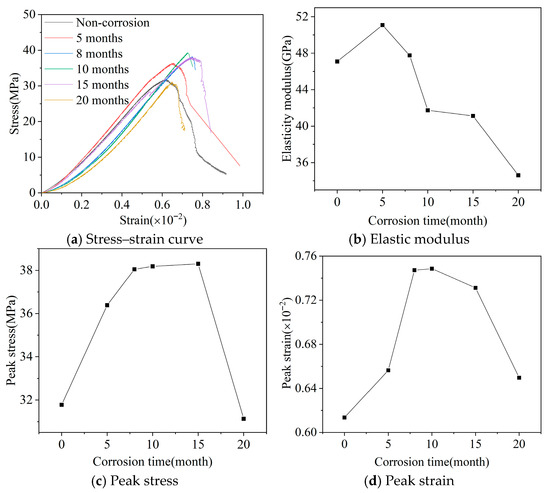

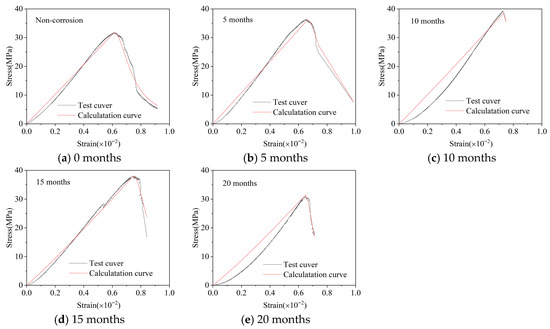

3.2. Prism Stress–Strain Curves and Characteristic Points

Figure 2 shows the stress–strain relationship curves and changes in characteristic points of concrete after different dry-wet cycles. According to the Chinese standard [34], the elastic modulus of concrete is calculated as the ratio of stress to strain at 0.4 times peak stress point, i.e., the secant modulus E from that point to the origin, as shown in Figure 2b. The maximum stress in the stress–strain curve is called peak stress, and the corresponding strain is called peak strain, as shown in Figure 2c,d, respectively.

Figure 2.

Stress–strain relationship curves and changes in characteristic points of concrete after different dry-wet cycles.

From Figure 2a, comparing the stress–strain curves of concrete after different dry-wet cycles with uncorroded specimens, at 5 months the strain value is less than that of uncorroded concrete at the same stress level, indicating that corrosion at this time has improved the concrete’s resistance to deformation to some extent; as dry-wet cycles increase, the degree of concrete corrosion gradually intensifies, and it can be clearly seen from the figure that after 8, 10, 15, and 20 months dry-wet cycles, the concrete’s resistance to deformation gradually decreases, with corroded strain values greater than uncorroded at the same stress level, and the gap between the two increases with dry-wet cycles. The reason is that under the action of external corrosion solution, many microcracks are generated inside the concrete due to the expansion of corrosion products, and the number of microcracks gradually increases with corrosion, leading to the need to pass a gradually increasing distance in the compaction process under compression as dry-wet cycle time increases at the same stress level, specifically manifested as gradually increasing concrete strain.

With the increase in dry-wet cycles, the initial slope of corroded concrete stress–strain curve gradually decreases. In the stress range of 0–5 MPa, the strain change amplitude of corroded concrete is gradually increasing. The reason is that after external corrosion salts enter the concrete, they react with internal substances to generate products with expansion effect. In the initial stage of corrosion, the corrosion products generated inside the concrete can fill the original pores of the concrete, which is beneficial to improving the compressive strength of concrete, but as corrosion intensifies, more microcracks are generated inside the concrete, damaging the concrete strength. In the initial loading stage, these microcracks close along the loading direction, macroscopically manifesting as small stress change and large strain change, and this phenomenon becomes more obvious with the extension of dry-wet cycles. Subsequently, the elastic modulus (secant modulus) shows a trend of first increasing then decreasing, indicating that the concrete’s resistance to deformation shows a trend of first increasing then decreasing with the increase in dry-wet cycles. Note that the measured elastic modulus values (ranging from approximately 44 to 52 GPa) are higher than those typically expected for C40 concrete, which may be attributed to the high-quality gravel aggregate used in this study, characterized by a low crushing index (8.7%) and high stiffness, leading to an enhanced overall modulus of the concrete mixture. The literature indicates that aggregate stiffness can increase concrete elastic modulus by up to 30% or more [35,36].

The peak stress generally shows a trend of first increasing then decreasing with the increase in dry-wet cycles, reaching the maximum at 15 months dry-wet cycles, a large increase compared to uncorroded concrete, with small change amplitude between 8 and 15 months, indicating that peak stress is less affected by corrosion in this stage, with a large decline from 15 to 20 months. The change trend of peak strain with the increase in dry-wet cycle time is basically the same as peak stress, also showing first increasing then decreasing, but the peak appears at 10 months.

In summary, in the erosion initial stage, external solution enters the concrete and reacts with concrete to generate corrosion products that have a filling effect on pores in concrete, which is beneficial to improving concrete strength; the slow rising stage (8 to 15 months) is because the generated products gradually increase, slowly filling the internal pores of concrete, to some extent hindering the continued erosion of ions, so the amplitude of strength change is not large; by 20 months dry-wet cycles, the expansion substances generated inside the concrete have filled the pores, with continued increase and expansion of corrosion products causing concrete swelling and cracking, leading to large strength degradation.

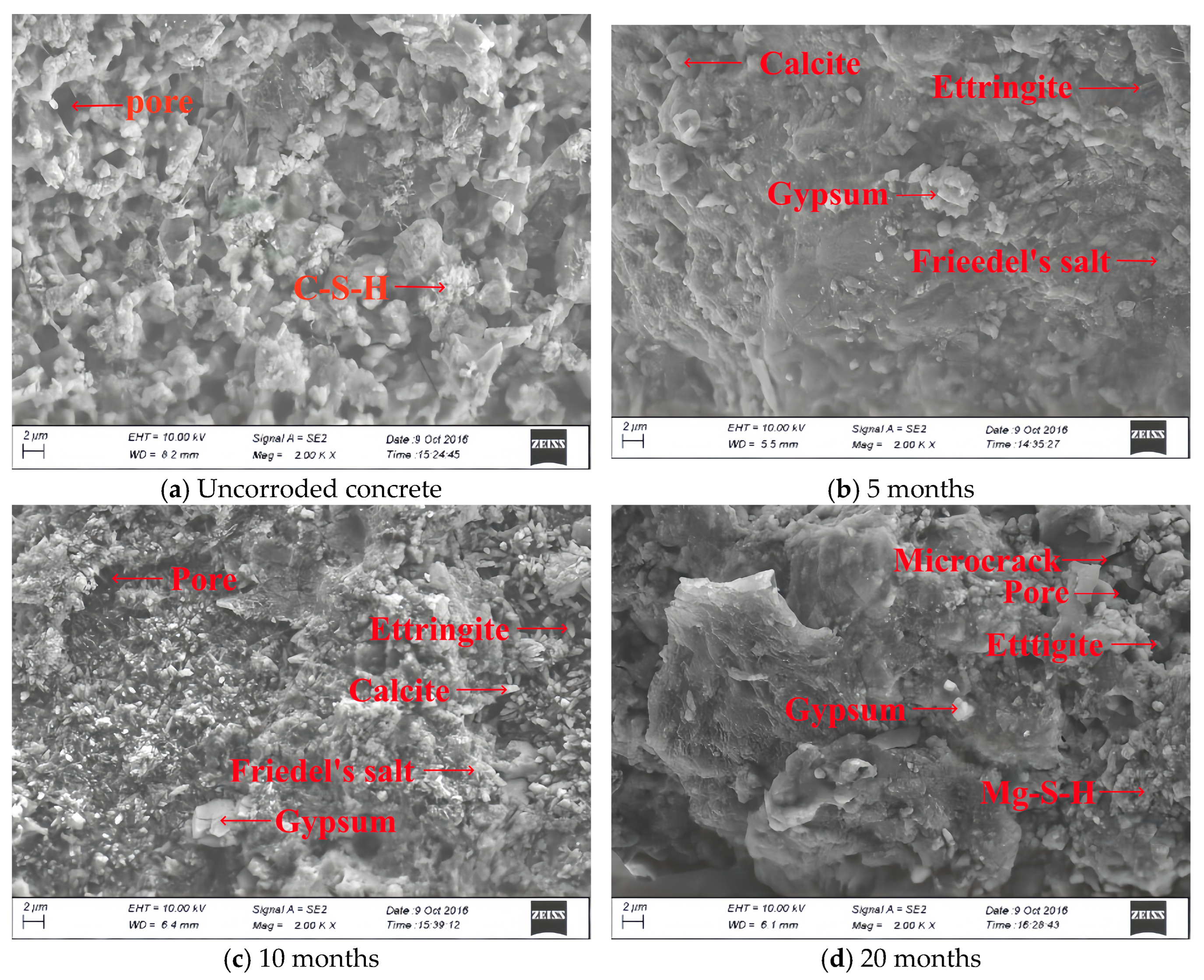

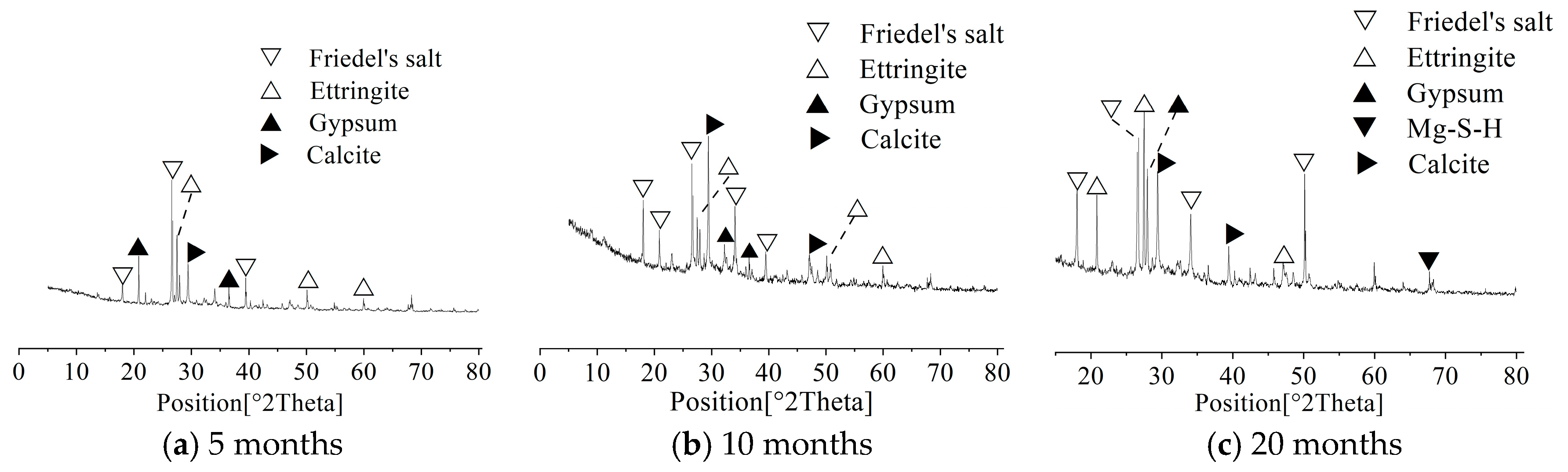

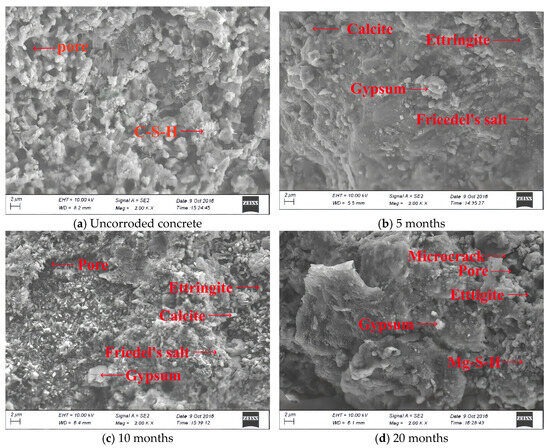

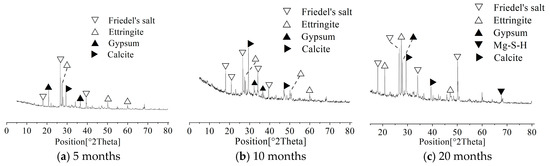

3.3. Mechanism Analysis

Figure 3 shows SEM images of concrete under different dry-wet cycles; Figure 4 shows XRD of concrete under different dry-wet cycles. From Figure 3a, it can be seen that uncorroded concrete SEM image has more pores, overall is more uniform and loose, and its constituent substances are mainly flocculent C-S-H. From Figure 3b, it can be seen that after 5 months of dry-wet cycles, the flocculent C-S-H gel appears less dominant in the microstructure, with pores increasingly occupied by crystalline formations. Combined with XRD analysis (Figure 4), these formations are identified as corrosion products such as ettringite, gypsum, and Friedel’s salt. This observation is consistent with the established understanding that multi-ion saline environments promote rapid formation of expansive sulfate- and chloride-bearing phases, thereby altering early-stage pore morphology [6,8]. The deposition of these corrosion products reduces pore size and increases matrix compactness, resulting in a macroscopic strength increase during the early corrosion stage.

Figure 3.

SEM of concrete under different dry-wet cycles.

Figure 4.

XRD of concrete under different dry-wet cycles.

From Figure 3c, it can be seen that there are obvious pores and microcracks inside the concrete, and a certain number of needle-like and flocculent substances exist. From the corresponding XRD analysis results, these corrosion products are needle-like ettringite, gypsum, calcium carbonate, and flocculent Friedel’s salt, etc. The above corrosion products are the main reason for microcracks inside the concrete, and their existence has a certain blocking effect on the intrusion of external corrosion ions, so between 8 and 15 months dry-wet cycles, concrete compressive strength and splitting tensile strength change little, and reaction to corrosion damage not obvious. At the same time, the expansion of corrosion products generates tensile stress inside the concrete, superimposed with external splitting load, making concrete splitting tensile strength more sensitive to corrosion damage.

From Figure 3d, it can be seen that numerous pores and microcracks have developed inside the concrete, indicating that prolonged corrosion has caused significant damage to the internal structure. XRD analysis results show the existence of M-S-H. After magnesium ions enter the concrete, they react with C-S-H through ion exchange, displacing Ca2+ and restructuring the silicate chains to generate M-S-H (magnesium silicate hydrate) [8,37,38]. M-S-H exhibits lower structural integrity and mechanical strength than C-S-H, further contributing to the decline in concrete performance.

The factors affecting concrete strength are many, so the strength change in corroded concrete is more complex. On one hand, due to the continuous progress of cement hydration, concrete strength will increase; on the other hand, when concrete is eroded by corrosion salts, in the initial stage of erosion, corrosion salts react with cement hydration products to generate substances that have a filling effect on internal pores of concrete, which can improve the compactness of concrete, thus improving concrete strength, but as corrosion aggravates, the internal structure of concrete will undergo serious deterioration; as larger holes and expansion cracks are generated inside the concrete, concrete strength will gradually decline. Therefore, concrete strength overall shows a trend of first increasing then decreasing with the increase in dry-wet cycle time, which is consistent with the measured values of concrete strength under different dry-wet cycles in the test results.

4. Strength Prediction Model Based on Grey Theory

4.1. Models for Changes in Strength and Characteristic Points on Stress–Strain Curves

Based on the Grey GM(1,1) model described in Section 2.3, the long-term prediction models for the mechanical parameters were established and validated as follows. To analyze the change law of compressive strength of concrete in western saline soil regions with dry-wet cycles, we took compressive strengths at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20 months as original sequence

, established grey GM(1,1) prediction model by Equations (1)–(10), obtained the specimen response function of the model, and predicted the compressive strength change law after 20 months dry-wet cycles.

The original sequence of cube compressive strength is:

The accumulated sequence is obtained as:

The smoothness of the original sequence is checked:

Thus, the original sequence is a quasi-smooth sequence.

A quasi-exponential law test is performed on

:

Therefore, it is determined that

satisfies the quasi-exponential law, and a GM(1,1) model can be established.

From the accumulated sequence

, the immediate mean sequence

is obtained as:

The parameter equation is:

where

,

.

Using the least squares method, we obtain a = 0.0360, b = 54.6047.

From the whitening equation:

The GM(1,1) prediction model for concrete compressive strength is derived as:

where k represents the dry-wet cycle period, with an interval of 5 months.

The calculation process for the grey theory GM(1,1) prediction models of concrete’s splitting tensile strength, elastic modulus, peak stress, and peak strain on the stress–strain curve follows the same procedure as described above. Their respective prediction models are:

The grey theory GM(1,1) prediction model for cube splitting tensile strength is:

The grey theory GM(1,1) prediction model for elastic modulus is:

The grey theory GM(1,1) prediction model for peak stress is:

The grey theory GM(1,1) prediction model for peak strain is:

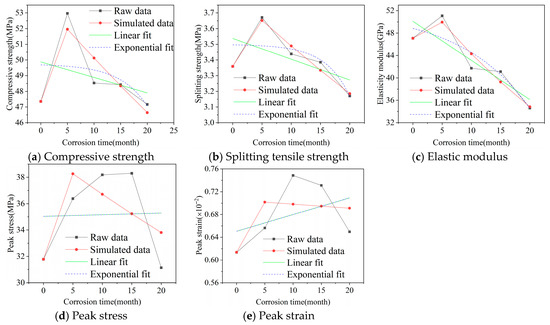

4.2. Model Accuracy Check for Concrete Strength and Characteristic Points

The comparison of simulated sequences and original sequences for concrete in western saline soil regions obtained by the model is shown in Figure 5. Taking Figure 5a compressive strength as example for model accuracy check and analysis, through analysis, the residuals are obtained as:

, residual sequence mean

, residual sequence variance

. Original data sequence mean

, original data variance

. Relative errors

, average relative error

. Posterior variance ratio

, small error probability

(since

). Determine p = 1. Based on accuracy verification results in Table 3, the cube compressive strength GM(1,1) prediction model for concrete in western saline soil regions reaches “excellent” accuracy standard (p = 1, C = 0.080).

Figure 5.

Comparison of simulated sequences obtained by GM(1,1) model and original sequences.

To further illustrate the value added by the grey GM(1,1) model, a comparative analysis with conventional regression models was conducted. Taking the cube compressive strength data as an example, a simple linear regression model failed to capture the non-monotonic trend, yielding a low coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.11) and predicting a physically unrealistic continuous decline from the initial state. An exponential decay model, while accounting for nonlinearity, could not represent the initial strength increase phase observed in the first 5 months. In stark contrast, the GM(1,1) model successfully characterized the complete “increase-then-decrease” degradation trajectory with excellent accuracy. This comparison underscores the superior suitability of the GM(1,1) model for predicting the nonlinear deterioration of concrete in saline soil environments, especially when working with limited sequential data.

The accuracy check processes for strength and characteristic points on stress–strain curves of concrete in western saline soil regions grey theory GM(1,1) prediction models are as above. The accuracy check table is Table 4. It can be seen that the GM(1,1) models constructed for strength and characteristic points all pass excellent accuracy checks (C < 0.35), confirming the universality of the model in characterizing performance of concrete in western saline soil regions, accurately characterizing nonlinear change laws of strength and characteristic points on stress–strain curves of concrete under saline soil environment in western regions.

Table 4.

Grey theory model check table for strength and characteristic points of concrete in western saline soil regions.

5. Constitutive Model and Life Prediction Based on GM(1,1)

5.1. Concrete Constitutive Model

In the extreme environment of coupled dry-wet cycling and multi-ion composite erosion in western saline soil regions, the degradation of concrete’s mechanical properties exhibits significant nonlinearity and damage accumulation. Its stress–strain relationship shows distinct characteristics compared to uncorroded concrete, such as markedly enhanced brittleness and a sharp drop in post-peak bearing capacity. Existing traditional constitutive models, based on non-corroded or single-erosion environments, struggle to accurately describe this complex evolution. Therefore, this section aims to establish a segmented constitutive model that considers the effect of corrosion time, providing a more realistic representation of the complete stress–strain behavior of corroded concrete under compression.

Based on the theoretical framework of continuum damage mechanics, the compressive failure of concrete in corrosive environments can be viewed as a process of continuous initiation, propagation, and eventual coalescence of internal micro-defects (e.g., microcracks) under load, leading to macroscopic performance deterioration. To quantify this irreversible damage evolution, a damage variable D (0 ≤ D ≤ 1) is introduced, where D = 0 represents intact material and D = 1 represents complete failure. Assuming elastic behavior [39], the stress–strain relationship for the damaged concrete can be expressed as:

where E is elastic modulus.

To define the evolution of the damage variable D with strain ε, the Weibull statistical distribution is adopted [40]. This distribution has a solid theoretical foundation for characterizing the strength and failure probability of brittle and quasi-brittle materials, and its form can effectively reflect the randomness of internal defect distribution. The damage evolution equation based on the Weibull distribution is expressed as:

where u is the scale parameter, related to the characteristic strain of the material; m is the shape parameter, controlling the shape of the damage accumulation curve and closely related to the brittleness of the material. Substituting Equation (23) into Equation (22) yields the damage-considered stress–strain relationship (ascending branch):

The model parameters m and u can be determined using key characteristic points on the stress–strain curve. These points include the peak point (

,

) and the boundary condition of zero tangent slope at that point (

). Solving these equations simultaneously yields the expressions for the parameters:

Substituting Equations (25) and (26) back into Equations (24) gives the constitutive equation for the ascending branch expressed in terms of measurable macroscopic parameters:

To enable the constitutive model to predict long-term corrosion processes, it is crucial to endow the parameters E,

, and

with time-dependent evolution capabilities. Therefore, this study incorporates the long-term prediction models (Equations (19)–(21)) established based on grey GM(1,1) theory in Section 4, which have been experimentally validated, into Equation (27). Thus, an explicit expression for the ascending branch of the stress–strain curve incorporating the dry-wet cycle corrosion time t (months) is obtained:

Here, the time-varying parameters E(t),

,

, and m(t) are calculated using Equations (19)–(21), and (25), respectively.

For the descending branch, due to the pronounced brittleness of corroded concrete, the curve exhibits a steep decline, and the experimental data show increased scatter. For practical purposes, the following empirical formula, derived from regression analysis of the experimental data, is used to describe the descending branch:

Substituting different corrosion times (t = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20 months) into Equations (28) and (29) yields the corresponding theoretical complete curves. As shown in Figure 6, the model-calculated curves compare well with the experimental results. The ascending branch shows high agreement with the test curves at all corrosion ages, indicating that the model accurately captures the stiffness degradation law of concrete caused by corrosion. Although the experimental data for the descending branch show some scatter due to increased material brittleness and damage accumulation, the empirical Formula (29) still reasonably reflects the overall trend of rapid loss of bearing capacity, achieving satisfactory accuracy within an engineering-acceptable range.

Figure 6.

Comparison of experimental stress–strain curves and calculated curves.

The descending branch in Equation (29) employs the empirical rational function form, where b is a dimensionless coefficient determined via regression of the experimental stress–strain data. Physically, b governs the curvature and steepness of the post-peak stress decay: a larger value of b results in a more rapid decline in normalized stress, corresponding to increased material brittleness and reduced ductility. This aligns with the corrosion-induced microstructural changes observed in our study, such as extensive microcracking, pore coarsening, and C-S-H decalcification, which diminish the concrete’s ability to sustain plastic deformation post-peak. In our model, b is related to the corrosion time t, quantitatively reflecting the progressive embrittlement over extended dry-wet cycles.

This empirical form is not unique to our study but is a standard representation in concrete mechanics, notably adopted in the Chinese code GB 50010-2010 for the compressive constitutive behavior of various concrete grades, where a similar coefficient

(analogous to b) is calibrated based on strength class and controls the energy dissipation in the softening regime [34]. The literature confirms its robustness across diverse mixtures, including high-strength concrete, fiber-reinforced concrete, and those under different environmental exposures (e.g., sulfate attack or freezing-thawing), provided the coefficient b is refitted to account for variations in mix design parameters like water–cement ratio, aggregate type, or admixtures [41,42,43]. For instance, in high-performance concretes with silica fume, the form holds but with lower b values indicating enhanced ductility [41]. Thus, while derived from our C40 ordinary Portland cement concrete, the equation is expected to apply to other mixtures through recalibration of b using mixture-specific tests, though direct validation is advised for substantially different compositions to ensure accuracy.

In summary, the segmented constitutive model established in this section, which integrates grey long-term prediction and Weibull damage distribution, can accurately describe the complete stress–strain behavior of concrete evolving with corrosion time in western saline soil environments. This model provides a reliable theoretical tool for assessing the damage state and nonlinear mechanical response of corroded concrete structures.

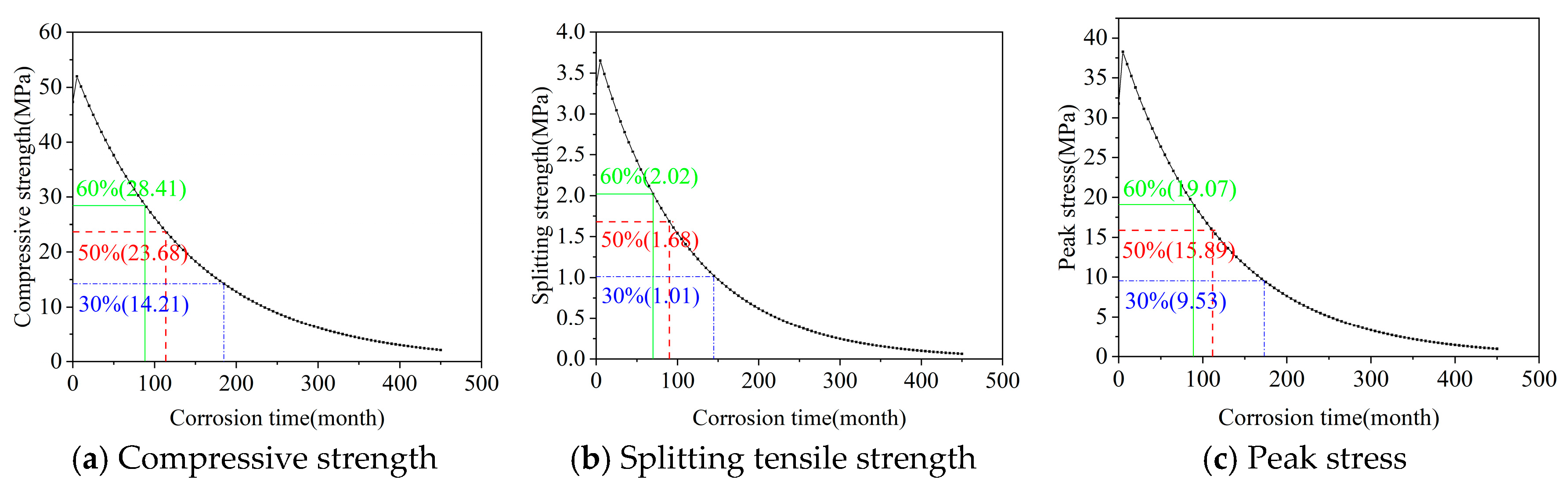

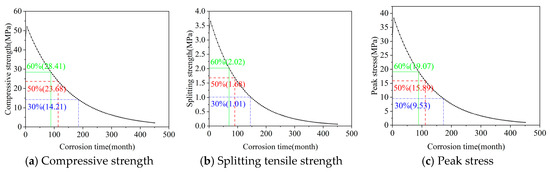

5.2. Concrete Life Prediction

Figure 7 shows the prediction results based on grey GM(1,1) model for compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, and peak stress of concrete in western saline soil regions under long-term dry-wet cycles. The three strength curves all show obvious nonlinear decay characteristics: faster decline rate in early stage, gradually slowing in later stage, consistent with the physical-chemical mechanism of intense reaction in initial saline soil erosion, slower deterioration rate in later stage due to partial pore filling by corrosion products.

Figure 7.

Strength prediction curves for concrete in western saline soil regions.

From prediction results, splitting tensile strength’s sensitivity to dry-wet cycling environment in saline soil is significantly higher than compressive strength and peak stress. When dry-wet cycles reach 200 months, compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, and peak stress decline to 26.9%, 18.5%, and 24.0% of initial values, respectively, with largest decay amplitude for splitting tensile strength. Taking 50% of design strength as bearing capacity critical threshold (compressive strength 23.68 MPa, splitting tensile strength 1.68 MPa, peak stress 15.89 MPa), three strengths reach this threshold at about 115 months, 90 months, and 112 months respectively. Controlled by most unfavorable indicator, the service life of ordinary concrete in western saline soil regions under natural dry-wet cycles and salt erosion coupled environment is only about 90 months (7.5 years), far below the 50-year design benchmark period required by code. This result is highly consistent with engineering surveys of severe salt erosion cracking, spalling, etc., in built concrete structures within 5–10 years in areas like Qinghai Qaidam Basin, Gansu Hexi Corridor, verifying the accuracy and applicability of the model.

The selection of 50% residual splitting tensile strength as the failure criterion is justified by its widespread use in concrete durability assessments, particularly in aggressive environments where tensile strength governs serviceability limits due to cracking, spalling, and loss of structural integrity [44,45]. This threshold represents a conservative point at which corrosion-induced damage typically compromises the structure’s ability to withstand service loads. It is also supported by literature indicating that approximately 50% strength loss is a common indicator of advanced corrosion in reinforced concrete, beyond which repair or replacement is often required to prevent failure [46].

To evaluate sensitivity, we used the GM(1,1) model for splitting tensile strength to recalculate the service life under natural dry-wet cycling conditions for thresholds of 60% and 30% residual strength. For a 60% threshold (indicating earlier intervention for less severe degradation), the predicted life is approximately 5.8 years (70 months), a 22.7% reduction compared to 7.5 years for 50%. For a 30% threshold (allowing more degradation before failure), the life extends to approximately 12 years (144 months), a 60% increase. These results highlight the model’s responsiveness to threshold variations, with higher thresholds yielding shorter conservative life estimates to prioritize safety, while lower ones extend life but risk greater structural compromise.

Combining analyses of Figure 6 and Figure 7, the segmented constitutive model established in this paper based on grey theory GM(1,1) predicting key parameters and continuous damage mechanics can not only describe stress–strain full curves of concrete at different corrosion ages with high accuracy (ascending branch almost coincides with test, descending branch accurately reflects brittleness enhancement feature), but also can further extrapolate to achieve strength long-term prediction and life assessment. Research shows that under the extreme environment of coupled saline soil and dry-wet alternation in western regions, tensile performance of concrete is the weakest link, and rapid microcrack expansion and interface transition zone deterioration dominate the structural failure process.

Therefore, for concrete structures in western saline soil regions, we must abandon traditional “strength meeting standard is enough” design concept, and urgently need to take targeted durability enhancement measures from the material level (such as adding high-quality mineral admixtures, selecting low water–cement ratio, using corrosion-resistant reinforcement, applying efficient surface protective coatings, etc.), or implement zoned protection and regular maintenance strategies from the structural level, to extend actual service life to design requirement level, avoid high early maintenance and reconstruction costs. The constitutive model and life prediction method proposed in this paper provide a reliable theoretical basis and quantitative tools for durability design, remaining life assessment, and maintenance decisions of concrete structures in this region.

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Under dry-wet cycling environment in western saline soil, mechanical properties of ordinary concrete show typical three-stage characteristics of “initial enhancement—mid-term slow—late sharp decline”, compressive strength and splitting tensile strength increase by 11.87% and 9.23%, respectively, at 5 months corrosion, drop to near initial value at 20 months, with splitting tensile strength most sensitive to corrosion.

- (2)

- Microscopic analysis shows that early strength enhancement originates from filling pores by ettringite, gypsum, Friedel’s salt, etc., mid-term strength stability benefits from blocking effect of corrosion products on erosive ions; late sharp strength decline dominated by Mg2+ induced C-S-H decalcification generating non-cohesive Mg-S-H and Mg(OH)2 as well as expansive crack expansion.

- (3)

- Established grey GM(1,1) prediction models for key parameters such as cube compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, elastic modulus, peak stress, and peak strain achieve “excellent” fitting and prediction accuracy (posterior variance ratio C ≤ 0.1221, small error probability p = 1), verifying their applicability in characterizing nonlinear laws of saline soil corrosion under small data conditions.

- (4)

- The proposed segmented compressive constitutive model combining grey prediction and Weibull damage distribution can describe stress–strain full curves of concrete at different corrosion ages with high accuracy (ascending branch almost coincides with test, descending branch accurately reflects brittleness enhancement feature).

- (5)

- Extrapolation life prediction shows that under natural dry-wet cycling conditions, ordinary concrete in western saline soil regions with tensile strength drop 50% as failure criterion, service life is only about 7.5 years; targeted durability enhancement measures from material (mineral admixtures, low water-cement ratio, anti-corrosion coatings) and structural (zoned protection, regular maintenance) levels are urgently needed.

Author Contributions

D.Y.: Writing—original draft, Funding acquisition. T.S.: Methodology, Funding acquisition. B.L.: Data curation, Funding acquisition. X.M.: Supervision, Funding acquisition. F.D.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research reported in this paper was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (Grant No. ZR2023ME113, ZR2024QE218, ZR2025MS802, ZR2022QD053), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52309137), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2024M751866), the Scientific Innovation Project for Young Scientists in Shandong Provincial Universities (Grant No. 2024KJH017), the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia, China (Grant No. 2025MS05007), and Keju Plan of Inner Mongolia University of Science and Technology (Grant No. KJJH2024967).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Han, J. Study of the durability of partially-exposed concrete in chloride saline soil areas of Qinghai Province. J. Hefei Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 2015, 38, 804–808. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z. Effect of physical and chemical sulfate attack on performance degradation of concrete under different conditions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 745, 137254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, R.; Xue, Y.; Wang, X.; Dou, X.; Song, Y. Damage evolution and life prediction of concrete in sulfate corrosion environments in Northwest China. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Li, J.; Shi, M.; Fan, H.; Cui, J.; Xie, F. Degradation mechanisms of cast-in-situ concrete subjected to internal–external combined sulfate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 248, 118683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kheetan, M.J.; Jweihan, Y.S.; Rabi, M.; Ghaffar, S.H. Durability enhancement of concrete with recycled concrete aggregate: The role of nano-ZnO. Buildings 2024, 14, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Li, F.; Niu, D. Study on the deterioration of concrete performance in saline soil area under the combined effect of high low temperatures, chloride and sulfate salts. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 150, 105531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Yan, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Li, J. Chloride threshold value and initial corrosion time of steel bars in concrete exposed to saline soil environments. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 267, 120979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gao, J.; Tang, L.; Li, X. Resistance of concrete against combined attack of chloride and sulfate under drying–wetting cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 106, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Guo, J.; Yang, L. Effect of dry–wet cycle on the physical salt attack of concrete in sulfate environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 302, 124418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Dong, Y.; Sun, X.; Jin, W. Damage mechanism of concrete deteriorated by sulfate attack in wet–dry cycle environment. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Eng. Sci.) 2012, 46, 1255–1261. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Liu, H.; Qin, D.; Doh, S.I. Study on the mechanical properties of desert sand concrete under dry–wet cycles with sulfate erosion. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2025, 138, 103852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Chen, C.; Zhang, M. Modeling of concrete deterioration under external sulfate attack and drying–wetting cycles: A review. Materials 2024, 17, 3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G.E.P.; Jenkins, G.M.; Reinsel, G.C.; Ljung, G.M. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control, 5th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed.; OTexts: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Xie, N.; Forrest, J. New progress of grey system theory in the new millennium. Grey Syst. Theory Appl. 2016, 6, 2–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J. Introduction to grey system theory. J. Grey Syst. 1989, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Liao, X. The study about prediction model of concrete carbonation depth. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Electric Technology and Civil Engineering (ICETCE), Lushan, China, 22–24 April 2011; pp. 2792–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Tian, W.; Gao, J.; Gao, Y. Performance evaluation and lifetime prediction of steel slag coarse aggregate concrete under sulfate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 344, 128203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, H.; Liu, H. Multiscale modeling of compressive strength degradation in manufactured sand concrete: Linking pore structure evolution to salt freeze-thaw damage. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R. Modeling constitutive relationship of sulfate-attacked concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 260, 119902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 175-2007; Common Portland Cement. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2007. (In Chinese)

- JGJ 55-2011; Specification for Mix Proportion Design of Ordinary Concrete. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011. (In Chinese)

- Mohamad, J.; Othman, Q.M.; Marc, Q.; Véronique, B.B. A Critical Review of Existing Test-Methods for External Sulfate Attack. Materials 2022, 15, 7554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amoudi, O.S.B. Attack on plain and blended cements exposed to aggressive sulfate environments. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2002, 24, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanam, M.; Cohen, M.D.; Olek, J. Sulfate attack research—Whither now? Cem. Concr. Res. 2001, 31, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, J.; Lv, Y.F.; Wang, D.; Ye, J. Study on the expansion of concrete under attack of sulfate and sulfate–chloride ions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 39, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Gao, J.; Qi, B.; Shen, D. Deterioration mechanism of plain and blended cement mortars partially exposed to sulfate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 154, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Sun, W.; Scrivener, K. Mechanism of expansion of mortars immersed in sodium sulfate solutions. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 43, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.S.; Kim, J.G.; Lee, K.M. Corrosion behavior of steel bar embedded in fly ash concrete. Corros. Sci. 2006, 48, 1733–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esselami, R.; Wilson, W.; Hamou, A.T. An accelerated physical sulfate attack test using an induction period and heat drying: First applications to concrete with different binders including ground glass pozzolan and limestone filler. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 345, 128046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Concrete Physical and Mechanical Properties. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- Bo, Z.; Ma, X.; Shi, J. Modeling Method of the Grey GM(1,1) Model with Interval Grey Action Quantity and Its Application. Complexity 2020, 6514236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, H. Calculation and realization of new method grey residual error correction model. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50010-2010; Code for Design of Concrete Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010. (In Chinese)

- Bentz, D.P.; Arnold, J.; Boisclair, M.J.; Jones, S.Z.; Rothfeld, P.; Stutzman, P.E.; Tanesi, J.; Kim, H. Influence of aggregate characteristics on concrete performance. In NIST Technical Note 1963; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Neville, A.M. Properties of Concrete, 5th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, E.; Lothenbach, B.; Cau-Dit-Coumes, C.; Chlique, C.; Dauzères, A.; Pochard, I. Magnesium and calcium silicate hydrates, Part I: Investigation of magnesium incorporation in C–S–H and calcium incorporation in M–S–H. Appl. Geochem 2018, 89, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lothenbach, B.; Nied, D.; L’Hôpital, E.; Achiedo, G.; Dauzères, A. Magnesium and calcium silicate hydrates. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 77, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Xu, J.; Bai, E. Dynamic stress-strain relationship of concrete subjected to chloride and sulfate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 165, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Meng, S.; Shi, Z.; Tao, S.; Zhu, D. A statistical damage constitutive model based on the Weibull distribution for alkali-resistant glass fiber reinforced concrete. Materials 2019, 12, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sima, J.F.; Roca, P.; Molins, C. Cyclic constitutive model for concrete. Eng. Struct. 2008, 30, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Mondal, P. Micro- and nano-scale characterization to study the thermal degradation of cement-based materials. Mater. Charact. 2014, 92, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, W.; Fan, Y.; Huang, X. An overview of study on recycled aggregate concrete in China (1996–2011). Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 31, 364–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.K.; Monteiro, P.J. Concrete: Microstructure, Properties, and Materials, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini, L.; Elsener, B.; Pedeferri, P.; Redaelli, E.; Polder, R. Corrosion of Steel in Concrete: Prevention, Diagnosis, Repair, 2nd ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Imam, A.; Mishra, S.; Bind, Y.K. Review study towards corrosion mechanism and its impact on durability of concrete structure. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2018, 5, 276–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.