1. Introduction

The healthcare landscape in the United States faces a formidable and persistent challenge in the form of hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) and surgical site infections (SSIs). These infections represent a significant threat to patient safety, contributing to increased morbidity, prolonged hospital stays, and a substantial rise in healthcare costs [

1,

2]. Alarmingly, approximately one in 31 hospital patients in the U.S. is affected by at least one HAI [

3]. While recent data from 2023 indicate a positive trend with overall declines in several key HAIs compared to the previous year, including central line-associated bloodstream infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, and hospital-onset

Clostridioides difficile infections, the burden remains considerable [

4,

5]. Notably, surgical site infections following certain procedures, such as abdominal hysterectomy, have shown an increase, highlighting the ongoing need for targeted prevention strategies.

Adding to the complexity of this challenge is the escalating occurrence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), particularly among a group of highly adaptable bacteria known as the ESKAPE pathogens:

Enterococcus faecium,

Staphylococcus aureus,

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Acinetobacter baumannii,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and

Enterobacter sp. [

5,

6]. In 2019, ESKAPE pathogens accounted for 42.2% of bacterial species isolated from bloodstream infections in the U.S. [

1]. The broader impact of AMR is evident in the 35,000+ deaths and 2.8 million recorded cases annually in the United States. This is further underscored by global figures reported to reach nearly 5 million deaths associated with AMR in 2019, according to the World Health Organization [

7].

A critical factor contributing to the recalcitrance of HAIs and SSIs, especially those involving medical devices, is the formation of bacterial biofilms. Biofilms are intricate communities of microorganisms attached to a surface and encased within a self-produced matrix known as the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) [

8]. Medical devices, such as catheters and implants, provide ample surfaces for microbial colonization and subsequent biofilm development [

9,

10]. The formation of biofilms on these devices is a key driver of device-associated infections, which are notoriously difficult to eradicate [

10,

11].

Previously, a biodegradable polymer, poly(aspartic acid) (PAA), was discovered to help prevent

Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm establishment when utilized as an anionic surface coating used in concert with neutrophils and DNase treatments in contact lenses [

12]. Recently, work shows microbes such as

Sphingomonas sp. inhabiting biofilms with

P. aeruginosa in medical environments [

11,

13]. This is important, as

Sphingomonas sp. strains have been reported to produce polymer-degrading enzymes capable of hydrolyzing thermally synthesized PAA (tPAA) to monomeric aspartic acid [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Specifically, studies by Tabata and colleagues demonstrated that

Sphingomonas sp. KT-1 and

Pedobacter sp. KP-2 isolated from river water can degrade tPAA through the action of PAA hydrolases (PahZ1 and PahZ2), with complete degradation requiring 12–15 days of co-culture [

20,

21]. Since monomeric aspartic acid is a common supplement used in bacterial growth media, this information raises questions about the long-term stability of PAA in polymer-based biocidal surface treatments, particularly in environments where PAA-degrading organisms may be present.

Despite these biodegradability concerns, PAA offers several unique beneficial properties that justify its continued investigation for antimicrobial coating applications. These include low cytotoxicity compared to many antimicrobial agents and the ability to chelate divalent metal ions such as calcium to facilitate bone mineralization and growth post-surgery—properties that are highly desirable for orthopedic and dental implant coatings. [

22] Additionally, the extended timeframe required for PAA biodegradation (12–15 days for complete degradation under optimal conditions) suggests that PAA-based coatings may remain sufficiently stable for acute antimicrobial applications [

20,

21]. Notably, oleic acid does not readily polymerize into stable polymer forms suitable for surface coatings due to its unsaturated fatty acid chemistry, precluding poly(oleic acid) as an alternative coating material.

To address potential weaknesses associated with the administration of single compound coatings using PAA and its derivatives, it is necessary to investigate potential methods to improve antibacterial efficacy and retain the desirable characteristics associated with these compounds. It has been widely reported that oleic acid (OleA) has strong anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antibacterial capacities while also being a naturally occurring compound often found within a normal diet [

23,

24,

25]. Further, current research describes how OleA has the capacity to integrate with Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial membranes, facilitating increased membrane permeability and increased antibacterial activity via membrane disruption [

26]. OleA has also been reported to significantly alter the expression profile of proteins involved in glucose metabolism, amino acid synthesis, and oxidative stress response in

Candida albicans [

27]. These myriad qualities position OleA as a promising potential candidate for application alongside PAA-based coatings.

The present proof-of-concept study was designed to establish whether sequential application of tPAA and OleA coatings could produce enhanced antimicrobial activity compared to individual compounds, and to identify whether coating sequence affects efficacy. Using P. aeruginosa and E. coli as representative Gram-negative pathogens, we sought to characterize the antimicrobial and antibiofilm effects of these ordered coating systems, assess preliminary biocompatibility, and develop hypotheses regarding mechanisms of action that can guide future development efforts. As shown in this research, coatings including concomitant layers of both tPAA and OleA prove to be more effective than either compound alone, with P. aeruginosa planktonic growth and biofilm formation reduced by as much as 62% and 43%, respectively. By examining the limitations of tPAA alone and highlighting the enhanced activity of OleA and tPAA combinations, along with considerations for cytotoxicity and the biofilm microenvironment, this research establishes preliminary feasibility and identifies directions for future investigation into the development of combination coating strategies to combat biofilm-related infections in healthcare settings.

This proof-of-concept study was designed to establish the preliminary feasibility of ordered tPAA-OleA coating systems for antimicrobial applications. Experimental design prioritized: (1) systematic comparison of ordered vs. individual coating applications; (2) multi-parameter assessment including planktonic growth, biofilm development, and cytotoxicity; and (3) identification of testable mechanistic hypotheses. Strain selection focused on representative Gram-negative organisms, with P. aeruginosa ATCC 27855 chosen as a well-characterized ESKAPE pathogen and E. coli BL21(DE3) selected for its extensive use in microbiology research and documented growth characteristics. Future studies should expand to diverse clinical isolates and additional pathogens.

2. Materials and Methods

The overall experimental workflow is depicted in

Figure 1A, which shows the standardized four-step coating protocol: Step 1—coating development and application with tPAA solutions applied to 96-well plates followed by kiln drying; Step 2—primary bacterial inoculation and plate setup; Step 3—measurement of planktonic growth or biofilm staining with crystal violet; and Step 4—comprehensive data analysis including growth curve fitting and statistical evaluation.

2.1. Application of tPAA and OleA Surface Coatings

Stock solutions of 50 mg/mL tPAA in Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) and OleA in 95% ethanol were prepared and then diluted to final concentrations of either 0, 5, 10, or 15 mg/mL (200 μL/well in 96-well costar clear plates and 2 mL in Nunc 35 mm glass-bottom dishes). Plates were then kiln dried overnight at 50 °C to evaporate solvent. Multi-component coatings were applied sequentially: Ex.) On day one, tPAA was added to the plate and kiln dried, then oleic acid was added the following day and dried in the same way to evaporate solvent. This was then followed by sterilization via UV-C radiation prior to cell culture. Compound coatings were developed by using an ordered layering of either tPAA then OleA (tPAA:OleA) or OleA then tPAA (OleA:tPAA). Compound coatings were not applied concurrently due to solubility incompatibilities. This coating methodology was developed specifically for this study and represents a simple, accessible approach suitable for proof-of-concept investigations; formal optimization of coating parameters was not performed.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate unless otherwise noted. Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, with significance levels indicated as: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.0.

2.3. Quantification of tPAA Coatings by Ninhydrin Test

The presence of amino acids in tPAA coatings was determined by the ninhydrin test. A solution of 2% w/v ninhydrin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was prepared by dissolving 2.0 g of ninhydrin powder in 100 mL of absolute ethanol. A 1:5 dilution of ninhydrin solution and distilled water was then added to a glass test tube previously coated with either 0, 5, 10, or 15 mg/mL concentrations of tPAA using either H2O or PBS as a vehicle and then mixed by vortexing and incubated in a hot water bath at 60 °C for 10 min. Samples were then cooled to room temperature, and optical density was measured at 570 nm (Abs570) via a spectrophotometer; values were compared to the standard curve to quantify percent coating retention before and after washing with H2O or PBS. It should be noted that this ninhydrin assay cannot distinguish between tPAA that is directly exposed versus tPAA protected by an OleA overlayer in ordered coating configurations. Characterization of OleA coatings would require alternative analytical methods due to the hydrophobic nature of oleic acid.

2.4. Cell Culture Methods

2.4.1. Bacterial Cell Culture

L.B. Miller broth (LB) was inoculated with frozen stocks of either Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27855) or BL21(DE3)pLysS Escherichia coli cells (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and incubated in a shaking incubator at 37 °C and 200 rpm until cultures reached mid-exponential phase between 0.4 and 0.6 optical density (O.D.) at 600 nm (OD600). Cultures were then diluted to 0.1 O.D. (OD600); cell densities of 3.45 × 107 CFU/mL (P. aeruginosa) and 7.1 × 107 CFU/mL (BL21-DE3) were used for seeding to 35 mm glass bottom dishes with 14 mm micro-well and #1.5 cover glass, where biofilms were allowed to develop for 24 or 72 h at 37 °C using a Carl Zeiss LSM 700 (Carl Ziess, Oberkochen, Germany) incubation module for subsequent imaging. For assays involving 96-well plates, micro-inoculates of 1 μL at concentrations of 3.45 × 107 CFU/mL (P. aeruginosa) and 7.1 × 107 CFU/mL (BL21-DE3), from 0.1 O.D. (OD600) stock solutions, were used. Cultures were then incubated at 37 °C in static culture for biofilm development or using a CLARIOstar® Plus plate reader (BMG Labtech, Ortenburg, Germany) under constant agitation between readings for planktonic growth.

2.4.2. Bacterial Growth Analysis

Bacterial cultures of either BL21-DE3 or

P. aeruginosa were seeded in accordance with cell culture methods mentioned above into wells of 96-well Corning™ Costar™ clear plates (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) and sealed to prevent contamination of cultures. Plates were then placed into a CLARIOstar

® Plus plate reader, where OD

600 was measured every 10 min under constant shaking at 200 rpm between readings for 12 h to measure planktonic growth. Lag phase duration calculations were determined using tools developed by Smug et al. [

28], where planktonic growth data was input for analysis.

2.5. Crystal Violet Biofilm Quantification

Ninety-six well plates were prepared according to the plate coating protocol described above for each respective coating condition. After seeding in accordance with the protocol listed above, cultures were incubated at 37 °C for either 24 or 72 h before gentle aspiration of liquid culture media, and plates were then inverted and allowed to dry overnight. A stock solution of 2% w/v Crystal Violet (C.V.) in 95% ethanol was prepared and then diluted to a 0.1% w/v solution in sterile H2O for staining of biofilms. A volume of 125 μL of the 0.1% C.V. solution was pipetted into each well and allowed to incubate at room temperature (RT) for 15 min before gentle aspiration and inversion to dry overnight. Quantification of biofilms was performed by pipetting 125 μL of 30% v/v glacial acetic acid to solubilize C.V. before measurement at OD600 using a CLARIOstar® Plus plate reader.

2.6. Mammalian Cytotoxicity (MTT) Assay

Mouse fibroblast (NIH/3T3) cells were cultured in Dulbecco Modified Eagle Media (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin, streptomycin, and glutamine at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After counting, cells were seeded to a density of 2 × 105 cells/mL in phenol-free DMEM at a volume of 99 μL per well in Corning® 96-well tissue culture treated polystyrene plates and allowed to adhere for two hours prior to addition of compounds. Aliquots of 1 μL of either tPAA, OleA, or tPAA and OleA from concentrated stock solutions were added to achieve final concentrations of 0, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 mg/mL for each compound in the appropriate wells, then incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 72 h. A volume of 20 μL of Thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Alfa Aesar, Holbrook, NY, USA) was then added to each well and allowed to incubate for 1 h. Medium was then removed, 100 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added, and samples were incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. Plates were then read on a CLARIOstar® Plus plate reader for absorbance (Abs. 570 nm).

2.7. Biofilm Immunostaining and Visualization via Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM)

Primary culturing of microbes was performed according to culture protocols mentioned previously, and cells were seeded into 35 mm glass-bottom dishes with 14 mm micro-well and #1.5 cover glass to incubate for 24 and 72 h prior to imaging utilizing the LSM 700 incubation module (Carl Ziess, Oberkochen, Germany) attached to the microscope. The samples were imaged using a Zeiss LSM700 confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Ziess, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4 Oil DIC M27 objective with images captured using ZEN Black (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and images analyzed by Fiji ImageJ software, version 2.17.0. Fluorescent labeling of nucleic acid structures was performed through immunohistochemical labeling with murine and rabbit monoclonal antibodies against B-DNA (Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA) and Z-DNA (Absolute Antibody, Newark, CA, USA), respectively. This was followed by treatment with AlexaFluor 405 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) goat anti-mouse and AlexaFluor 647 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) goat anti-rabbit labeled secondary antibodies for visualization via CLSM to distinguish between B-form and Z-form DNA. Antibody solutions were prepared in a 1 mL solution of 10% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) (Sigma) and 1.0 mM PMSF (VWR Life Science, Radnor, PA, USA) at a dilution factor of 2:1000.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Development of Stable Coating Methodology and Establishment of Baseline Antimicrobial Activities

Initial coating durability assessments revealed challenges with tPAA retention when applied using water as the vehicle. Ninhydrin-based quantification of amino acid content demonstrated coating retention of ~70%–90% when initially applied in H

2O. Coating loss occurred following standard washing procedures, with retention dropping to approximately 40%–70% across all tested concentrations (0–15 mg/mL) when water was used as the solvent (

Figure 1B). At the highest tPAA concentration, 15 mg/mL, 46 ± 14% of the applied tPAA was retained after a single wash step using H

2O. This reduction is consistent with the high water solubility of tPAA, which could compromise the long-term stability of antimicrobial coatings in aqueous environments.

To address these retention limitations, we evaluated phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as an alternative vehicle for tPAA application. Remarkably, PBS-based tPAA coatings demonstrated significantly enhanced retention characteristics, with coating stability approaching 100% at concentrations of 10 mg/mL and above (****

p < 0.0001) (

Figure 1B). The improved retention observed with PBS likely results from ionic interactions between the phosphate buffer system and the polyanionic tPAA backbone, creating more stable surface adherence. At 15 mg/mL concentrations, PBS-formulated coatings maintained 90 ± 5% retention compared to 46 ± 11% for water-based applications following wash procedures. These findings suggest that PBS is an optimal vehicle for tPAA coating applications in this proof-of-concept study and demonstrate that coating retention can be significantly enhanced through appropriate buffer selection.

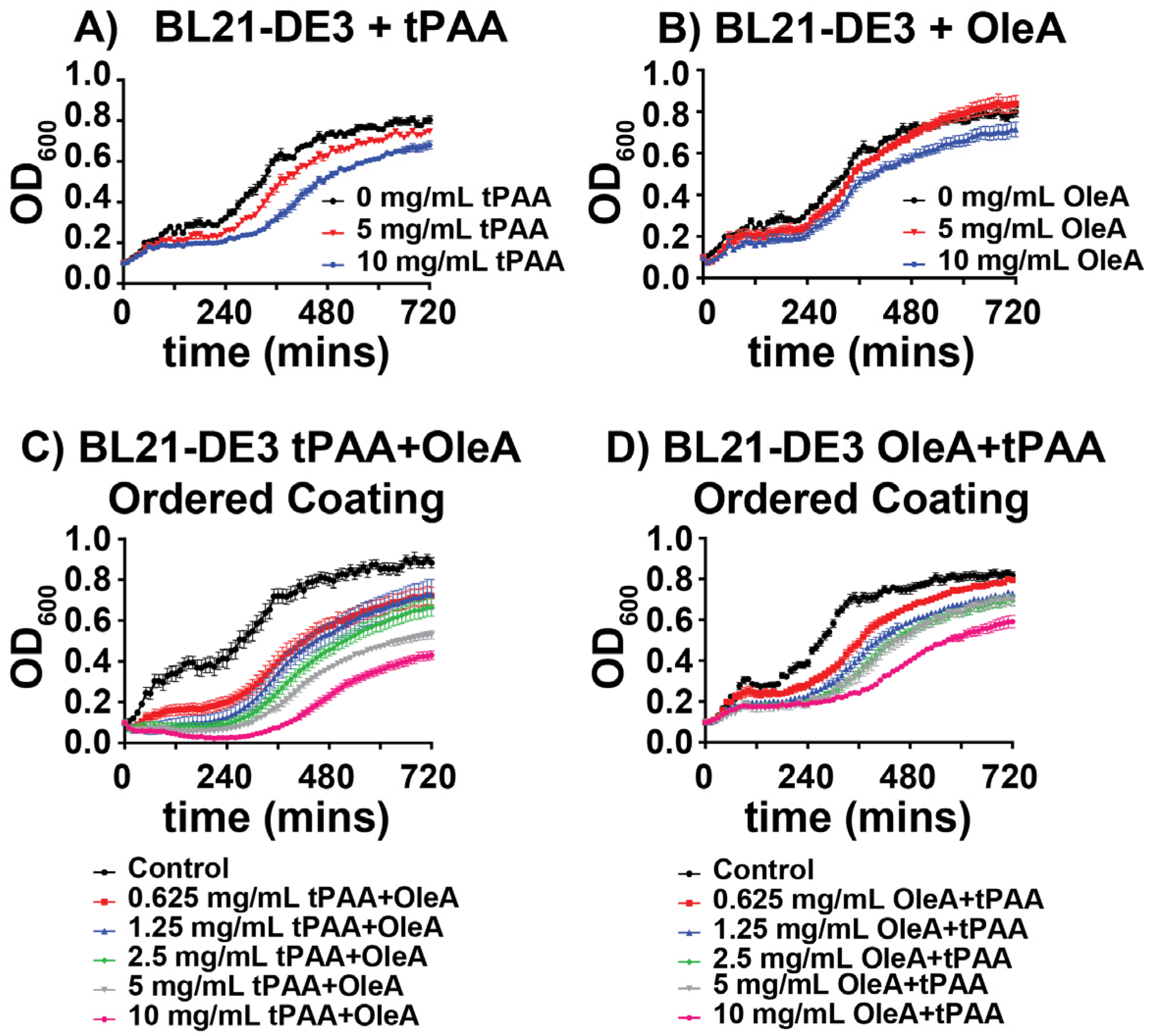

To establish baseline antimicrobial activities, we evaluated the individual effects of tPAA and OleA coatings on BL21(DE3) planktonic growth over a 12 h period. tPAA coatings demonstrated dose-dependent growth inhibition, with 5 mg/mL and 10 mg/mL concentrations reducing final optical density by ~7% and 15%, respectively, compared to untreated controls (

Figure 2A). The growth curves reveal that tPAA primarily affects the exponential growth phase, with treated cultures showing extended lag phase characteristics when compared to controls. OleA coatings exhibited similar antimicrobial activity when compared to tPAA alone, with 10 mg/mL concentrations producing an 11% reduction in final growth density (

Figure 2B). However, no significant impact on lag phase is observed. Taken together, these preliminary data suggest a role for tPAA in planktonic growth inhibition for BL21(DE3).

3.2. Ordered Coating Systems Reveal Sequence-Dependent Enhanced Activity

Due to the need for development of novel antibacterial compounds which address a constantly adapting microbiome, we investigated co-implementation of these individual coatings to establish the benefit, if any, of coordinated coating applications as compared to the single compound coatings mentioned above. The development of ordered coating systems revealed enhanced antimicrobial effects that appeared to exceed the individual activities of either compound alone. When applied as tPAA followed by OleA, notated as (tPAA + OleA), the combined coatings produced significant dose-dependent growth inhibition against BL21(DE3) (

Figure 2C). At the highest concentration tested (10 mg/mL, tPAA + OleA), the tPAA + OleA ordered coating reduced final cell density by ~50% compared to controls, representing an enhancement that cannot be explained by simple additive effects of individual compounds. For reference, tPAA alone at 10 mg/mL produced 15% inhibition, and OleA alone produced 11% inhibition, which would sum to approximately 26% if purely additive, less than the observed 50% inhibition with the ordered coating.

The reverse application order (OleA + tPAA) also demonstrated significant antimicrobial activity, though with notably different kinetic profiles (

Figure 2D). While the final growth inhibition was comparable to the tPAA + OleA configuration at lower concentrations (5.4% change at 0.625 mg/mL), the OleA + tPAA order produced more gradual growth suppression throughout the exponential phase rather than the sharp growth rate reduction observed with tPAA + OleA coatings. This difference in kinetic profiles suggests that the sequence of application may alter the mechanism of antimicrobial action, though direct mechanistic validation was beyond the scope of this proof-of-concept investigation. Importantly, the layer order affects which component is directly exposed to the aqueous bacterial culture: in tPAA + OleA configurations, the hydrophobic OleA overlayer may create a barrier that modulates bacterial access to the underlying tPAA, whereas in OleA + tPAA configurations, the hydrophilic tPAA is directly exposed while OleA is sequestered beneath. Coating integrity under the agitation conditions used for planktonic growth assays was not directly assessed and represents an important parameter for future investigation.

Quantitative analysis of final carrying capacities confirms that ordered coating systems provide enhanced antimicrobial efficacy compared to individual compound treatments (

Figure 3A). Individual tPAA coatings at 5 mg/mL and 10 mg/mL reduced final OD

600 values to 0.79 ± 0.04 (n.s.) and 0.67 ± 0.04 (*

p < 0.05), respectively, representing significant reductions compared to untreated controls (0.84 ± 0.02). OleA alone demonstrated similar trends, but was also met with less consistent results.

The ordered coating systems revealed striking concentration-dependent and sequence-dependent effects that exceeded individual compound activities. The tPAA + OleA configuration demonstrated superior antimicrobial performance, with the highest concentration (10 mg/mL) reducing carrying capacity to 0.43 ± 0.06, representing a 49% reduction compared to controls (**** p < 0.0001). In contrast, the OleA + tPAA configuration, while still effective, showed more modest reductions, with the 10 mg/mL treatment achieving a carrying capacity of 0.59 ± 0.09, corresponding to a 29% reduction.

Analysis of lag phase duration provides insights into how ordered coatings disrupt bacterial growth kinetics (

Figure 3B). Control cultures exhibited baseline lag phases of 83 ± 8 min and both ordered coating systems produced dose-dependent extensions of lag phase duration that correlate with their antimicrobial potency. The tPAA + OleA configuration at 10 mg/mL extended lag phase duration to 304 ± 18 min, representing a 365% increase compared to controls (****

p < 0.0001). The 5 mg/mL concentration produced a 237 ± 9 min lag phase, corresponding to a 284% increase. The OleA + tPAA configuration also significantly extended lag phases (matching the 5 mg/mL tPAA + OleA treatment lag time) with 10 mg/mL treatments producing 237 ± 21 min lag phases (381% increase).

The performance of these tPAA and OleA ordered coatings provides preliminary insights that can guide future mechanistic investigation. We propose that tPAA may function as a conditioning agent that could alter bacterial surface properties to potentially enhance OleA efficacy. The polyanionic nature of tPAA could neutralize positive surface charges on bacterial cell walls, creating electrostatic conditions that might facilitate OleA integration into membrane structures. Alternatively, tPAA binding may create conformational changes in membrane proteins or lipopolysaccharide structures that could enhance fatty acid accessibility to critical cellular targets. Conversely, when OleA is applied first, the hydrophobic coating may create a barrier that limits subsequent tPAA access to bacterial surface binding sites. However, these proposed mechanisms require direct experimental validation.

3.3. Species-Specific Antimicrobial Responses Reveal Enhanced Pathogen Susceptibility

To investigate the broader implications and potential efficacy of these treatments, the multi-drug-resistant ESKAPE pathogen

P. aeruginosa was chosen for susceptibility testing to these new antibacterial coatings.

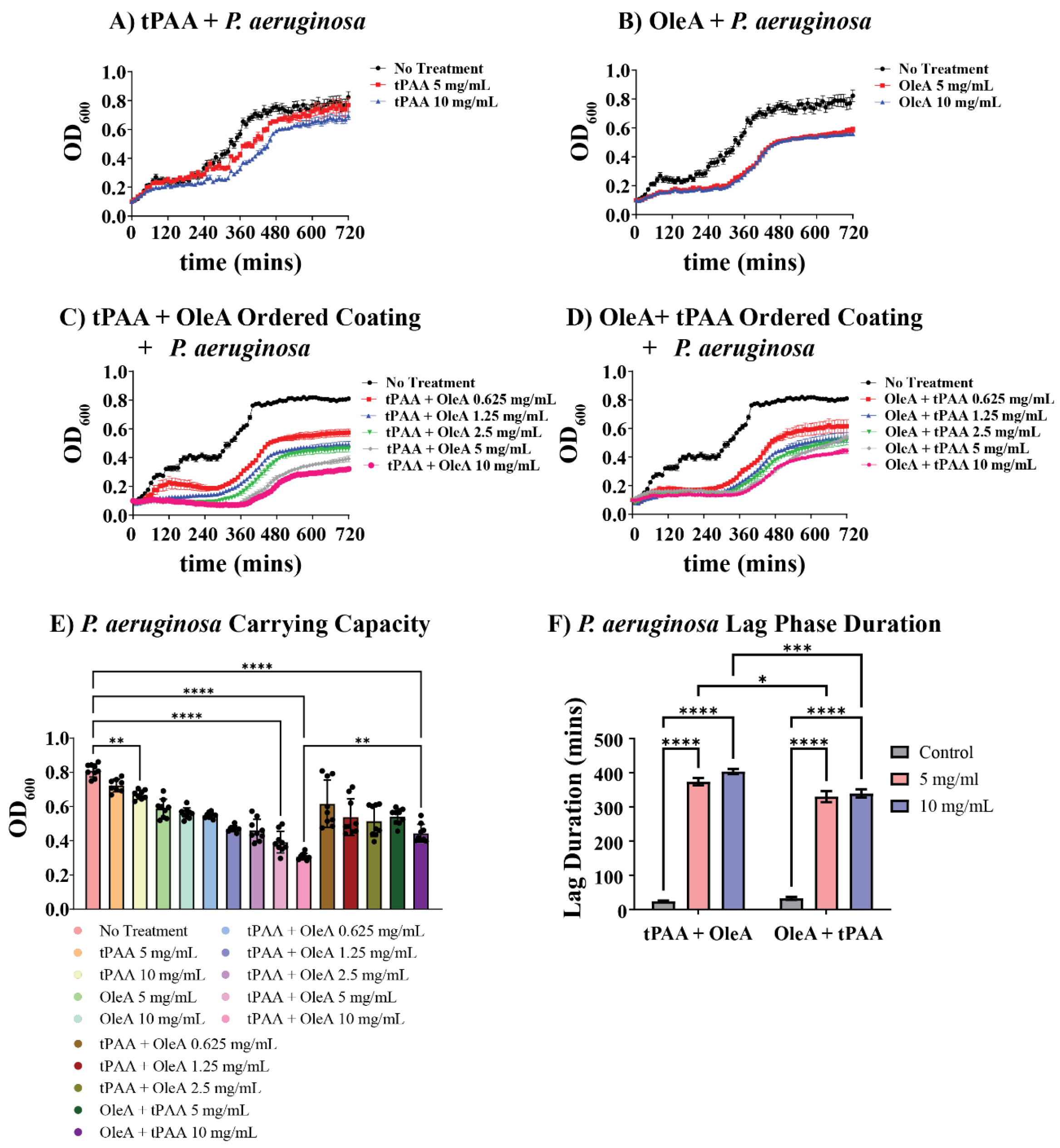

P. aeruginosa displayed markedly different susceptibility patterns compared to BL21-DE3, revealing important species-specific responses to both individual and combined coating treatments. Individual tPAA coatings showed minimal effects on

P. aeruginosa growth, with 5 mg/mL and 10 mg/mL concentrations producing only modest reductions in carrying capacity (

Figure 4A). The growth curves demonstrate that tPAA alone provides limited antimicrobial activity against this clinically relevant pathogen.

In contrast, OleA demonstrated potent antimicrobial activity against

P. aeruginosa, with dramatic effects on both growth kinetics and final cell yields (

Figure 4B). The 5 mg/mL OleA treatment reduced final carrying capacity to approximately 27% of controls, while 10 mg/mL concentrations achieved nearly 31% reduction. Notably, OleA treatments produced pronounced effects on growth curve shape, with treated cultures exhibiting extended lag phases and reduced exponential growth rates.

The ordered coating systems produced enhancement effects against

P. aeruginosa that far exceeded the activity observed with individual compounds (

Figure 4C,D). Both tPAA + OleA and OleA + tPAA configurations demonstrated progressive, concentration-dependent growth inhibition across the entire tested range (0.625–10 mg/mL). At the highest concentrations, tPAA + OleA ordered coatings reduced

P. aeruginosa carrying capacity to less than 38% of control values, representing some of the most potent antimicrobial effects observed in this study.

Carrying capacity analysis demonstrates that

P. aeruginosa is significantly more susceptible to ordered coating treatments than BL21-DE3 (

Figure 4E). Statistical analysis reveals significant differences between all treatment groups (****

p < 0.0001), confirming that ordered coatings provide superior antimicrobial efficacy compared to individual compounds. The tPAA + OleA configuration demonstrated a 62% reduction in carrying capacity at 10 mg/mL, while the OleA + tPAA sequence achieved a 45% reduction. Importantly, significant antimicrobial effects were observed at all concentrations for both ordered coating systems. Indeed, treatment with as little as 0.625 mg/mL for tPAA + OleA or OleA + tPAA yield 32% and 24% reductions in carrying capacity, respectively.

The differential susceptibility of

P. aeruginosa versus BL21-DE3 to individual and ordered coating treatments likely reflects differences in membrane composition, lipopolysaccharide structure, efflux pump expression, and stress response pathway activation between these species. A single mechanism cannot fully explain the differential responses observed; rather, species-specific responses may emerge from variations in: (1) outer membrane architecture and lipid composition, (2) cell surface charge distribution, (3) membrane fluidity and fatty acid incorporation capacity, and (4) activation of specific stress response pathways [

29]. These species-specific differences have important implications for clinical applications, as coating efficacy in polymicrobial infections may be complex and dependent on community composition. Future mechanistic studies should include comparative transcriptomic profiling to identify species-specific stress responses to coating exposure.

Lag phase duration analysis provides insights into the mechanisms underlying enhanced

P. aeruginosa susceptibility (

Figure 4F). Both ordered coating sequences produced concentration-dependent extensions of lag phase duration that exceeded 6 h at the highest concentrations tested. The tPAA + OleA configuration extended lag phases to 373 ± 10 min at 5 mg/mL and 403 ± 7 min at 10 mg/mL, representing increases that are ~17-fold compared to control cultures (23 ± 2 min).

The pronounced effects of ordered coatings on

P. aeruginosa growth kinetics, particularly the significant lag phase extensions, suggest that the combination of tPAA and OleA creates significant physiological stress for this pathogen. Two potential mechanisms may contribute to these effects: first, the polyanionic tPAA coating could interact with cationic components of the

P. aeruginosa outer membrane, potentially altering membrane permeability and facilitating secondary effects from oleic acid exposure [

30]. Second, the observed lag phase extensions may reflect disruption of early-stage cellular processes critical for growth initiation, such as membrane remodeling or metabolic pathway activation, which could be particularly sensitive to fatty acid exposure in

P. aeruginosa [

26]. However, these proposed mechanisms remain speculative. Future mechanistic studies should include membrane integrity assays (e.g., propidium iodide uptake, membrane potential measurements), lipid composition analysis, and comparative transcriptomic profiling to establish the specific molecular basis for the observed antimicrobial effects and any species-specific responses.

3.4. Differential Antibiofilm Efficacy and Preliminary Insights into Structural Disruption

To address the fact that these microbes primarily exist within the context of biofilms and less as planktonic individuals, we investigated the effects of these treatments on biofilm accumulation. It is important to note that our experimental design, which applied coatings before bacterial inoculation and assessed biofilm mass at discrete time points, cannot distinguish between inhibition of biofilm formation (reduced synthesis/attachment) and disruption of established biofilm structure. The data presented demonstrate reduced biofilm accumulation in the presence of coatings but do not establish whether this reflects prevention of biofilm formation, degradation of established biofilm, or a combination of both effects. Future studies employing coating application to pre-formed biofilms versus during biofilm initiation would be needed to distinguish these mechanisms.

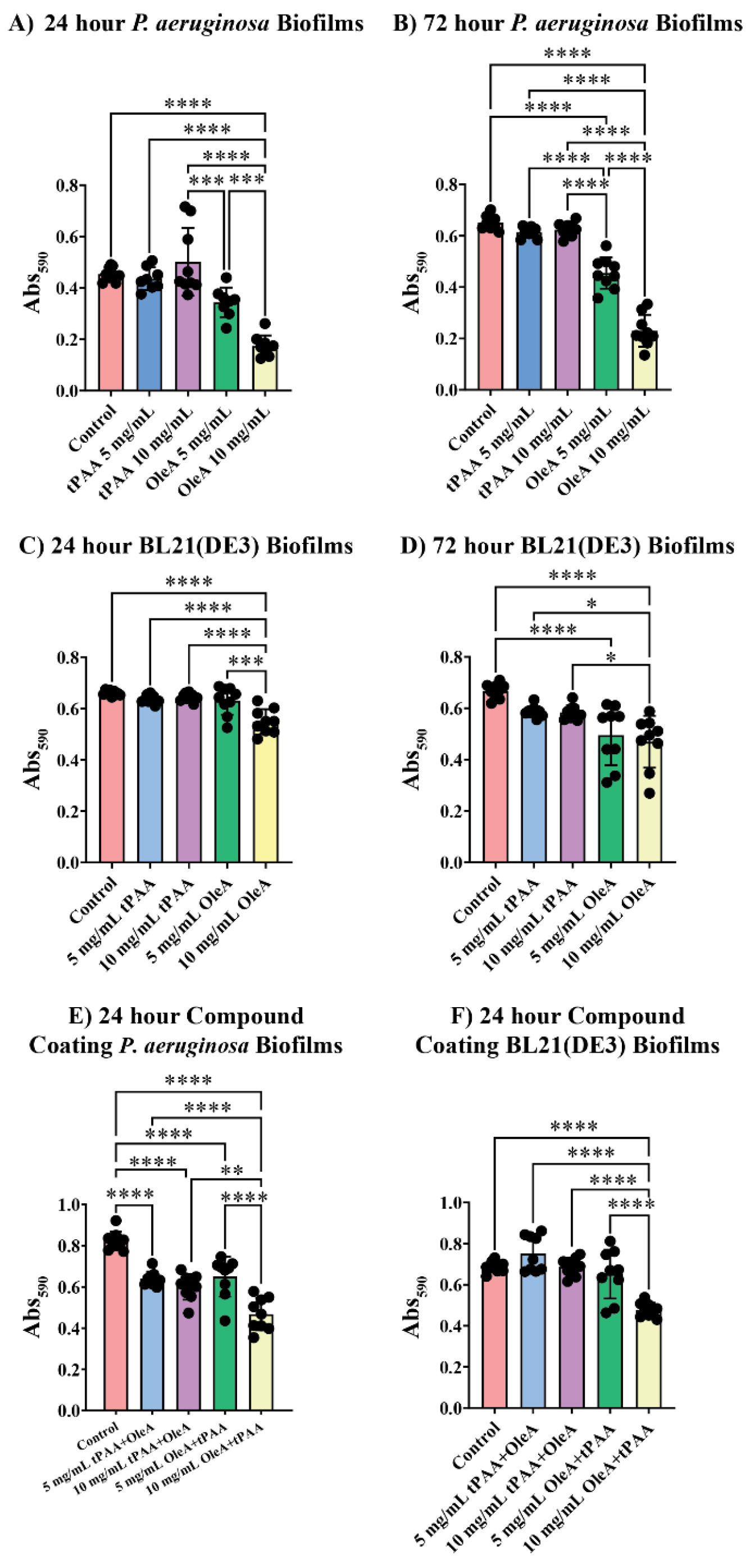

Biofilm quantification experiments revealed species-specific differences in antibiofilm susceptibility, with

P. aeruginosa showing compound-specific sensitivity compared to BL21(DE3) across all treatment conditions (

Figure 5A,B). At 24 h, tPAA treatments at 5 mg/mL and 10 mg/mL showed no significant reductions compared to controls, with a mean 590 nm absorbance equal to 0.46 ± 0.03. OleA demonstrated substantial antibiofilm activity, with 10 mg/mL treatments reducing biofilm mass to 0.17 ± 0.04, corresponding to a 62% reduction.

Antibiofilm effects became more pronounced with extended incubation periods. At 72 h, P. aeruginosa biofilms treated with 10 mg/mL OleA showed significant inhibition, maintaining biofilm mass at 0.22 ± 0.06 Abs590 units compared to controls at 0.65 ± 0.03 (**** p < 0.0001). This represents a 65% reduction, suggesting that the inhibitory effect is persistent throughout the biofilm maturation process.

In contrast to

P. aeruginosa, BL21(DE3) biofilms showed remarkable resistance to individual compound treatments, particularly at early time points (

Figure 5C,D). At 24 h, neither tPAA nor 5 mg/mL OleA treatments produced significant reductions in biofilm mass. Extended incubation to 72 h revealed statistically significant effects for OleA treatments, with 10 mg/mL OleA reducing biofilm mass by 30% to 0.47 ± 0.1 Abs

590 compared to controls at 0.67 ± 0.03 (****

p < 0.0001).

The ordered coating systems revealed the most dramatic antibiofilm effects, notably against

P. aeruginosa (

Figure 5E). Both tPAA + OleA and OleA + tPAA configurations at 10 mg/mL reduced

P. aeruginosa biofilm mass to 0.59 ± 0.06 and 0.47 ± 0.08 Abs

590 units, respectively, representing 27% and 43% reductions (***

p < 0.0001). The enhanced nature of ordered coating effects is evident when comparing individual compound activities to combination treatments.

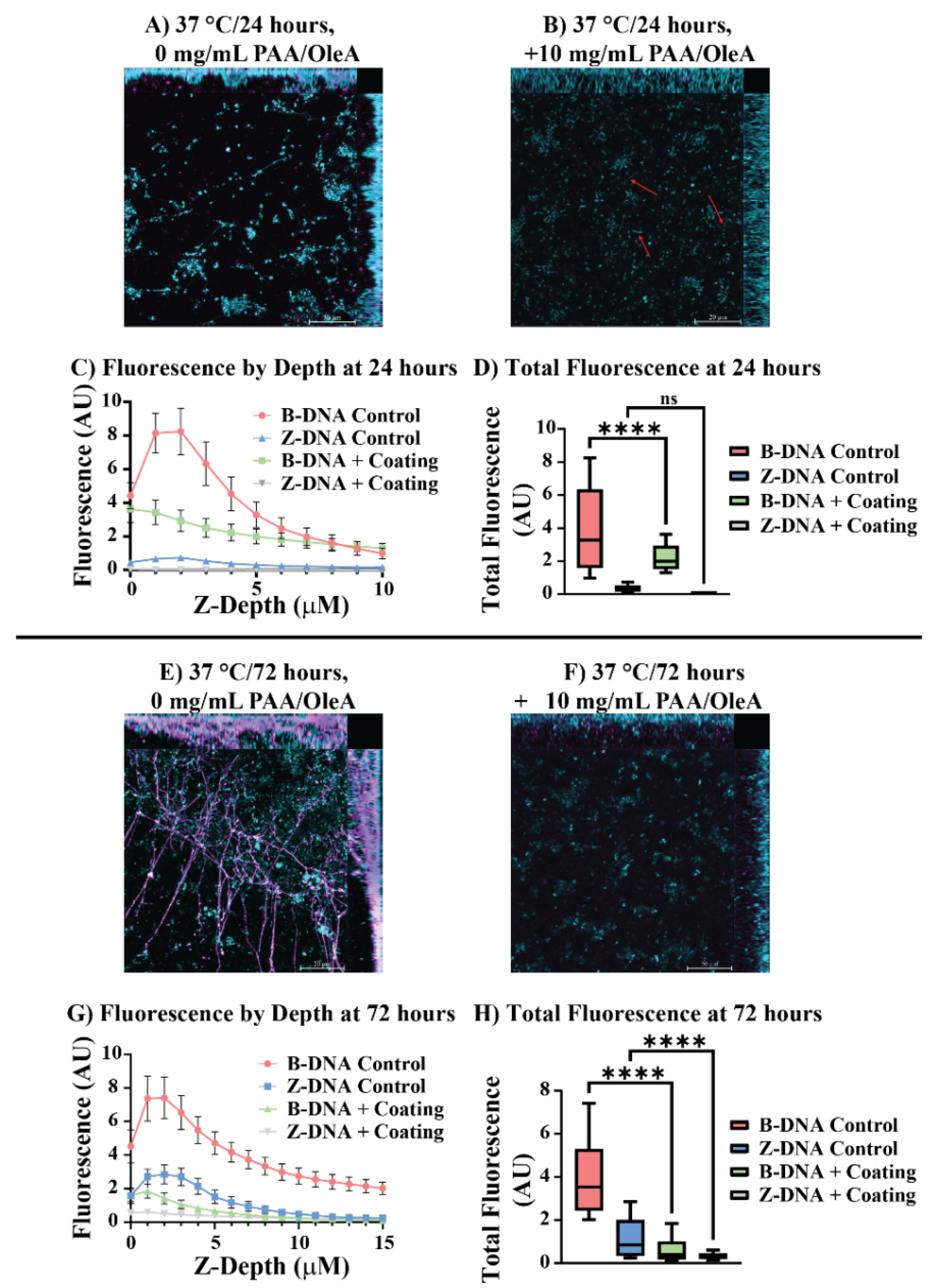

Confocal laser scanning microscopy with immunohistochemical labeling of B-form and Z-form DNA structures provided preliminary insights into how ordered coating systems affect

P. aeruginosa biofilm architecture at the molecular level (

Figure 6). Control biofilms at 24 h displayed characteristic biofilm features, including extracellular DNA (eDNA) networks distributed throughout the biofilm matrix primarily composed of B-DNA (

Figure 6A). The blue fluorescence corresponding to B-DNA labeling reveals interconnected structures that form the scaffolding typical of established

P. aeruginosa biofilms.

Treatment with 10 mg/mL tPAA + OleA ordered coatings produced structural alterations visible even at the macroscopic level (

Figure 6B). The treated biofilms showed markedly reduced B-DNA fluorescence intensity and disrupted spatial organization, with red arrows highlighting regions where extracellular B-DNA structures are notably diminished or absent. Depth-resolved fluorescence analysis at 24 h revealed striking differences in eDNA distribution between control and treated biofilms (

Figure 6C). Control biofilms exhibited robust B-DNA fluorescence that peaked at approximately 8 arbitrary units (AU) near the surface, while ordered coating treatment produced dramatic reductions in B-DNA fluorescence across all measured depths, with peak intensities reduced to approximately 3.5 AU. As expected for an immature biofilm, Z-DNA is not a major component for either condition at 24 h.

Total fluorescence quantification confirmed the visual observations, with tPAA + OleA treatment reducing total B-DNA fluorescence from 3.9 AU to 2.2 AU, representing a 43% reduction (****

p < 0.0001) (

Figure 6D). The 72 h confocal analysis revealed even more dramatic differences (

Figure 6E,F). Control biofilms developed extensive, complex three-dimensional structures with prominent eDNA networks that are hallmarks of mature biofilm development and are further evidenced after 72 h incubations as B-form eDNA is converted to the Z-form [

31]. Fluorescence quantification by depth of treated biofilms for 72 h reveals a strong reduction in eDNA lattice development that is consistent with confocal imaging; biofilms treated with ordered coatings remained significantly underdeveloped even after 72 h of incubation. Total fluorescence quantification at 72 h showed that treated biofilms maintained suppressed B-DNA (0.63 AU) and Z-DNA levels (0.33 AU), representing a 84% and 72% respective reduction compared to controls (****

p < 0.0001) (

Figure 6G,H).

The observed reduction in extracellular DNA fluorescence correlates with reduced biofilm development, though the causal relationship between coating application and eDNA reduction requires further investigation. eDNA serves critical structural and functional roles in

P. aeruginosa biofilms, acting as both a scaffold for cell attachment and a reservoir for horizontal gene transfer [

32,

33]. Several mechanisms could potentially explain the observed eDNA reduction. The polyanionic nature of tPAA may directly interact with eDNA through electrostatic mechanisms, potentially causing precipitation or aggregation that removes DNA from the biofilm matrix. Alternatively, the membrane-disrupting effects of OleA could interfere with the controlled lysis processes that

P. aeruginosa uses to release DNA into the biofilm matrix [

25,

26,

34]. Future work should employ eDNA-deficient mutants or DNase-treated biofilms to establish whether eDNA reduction is a primary mechanism of coating action or a secondary consequence of bacterial death.

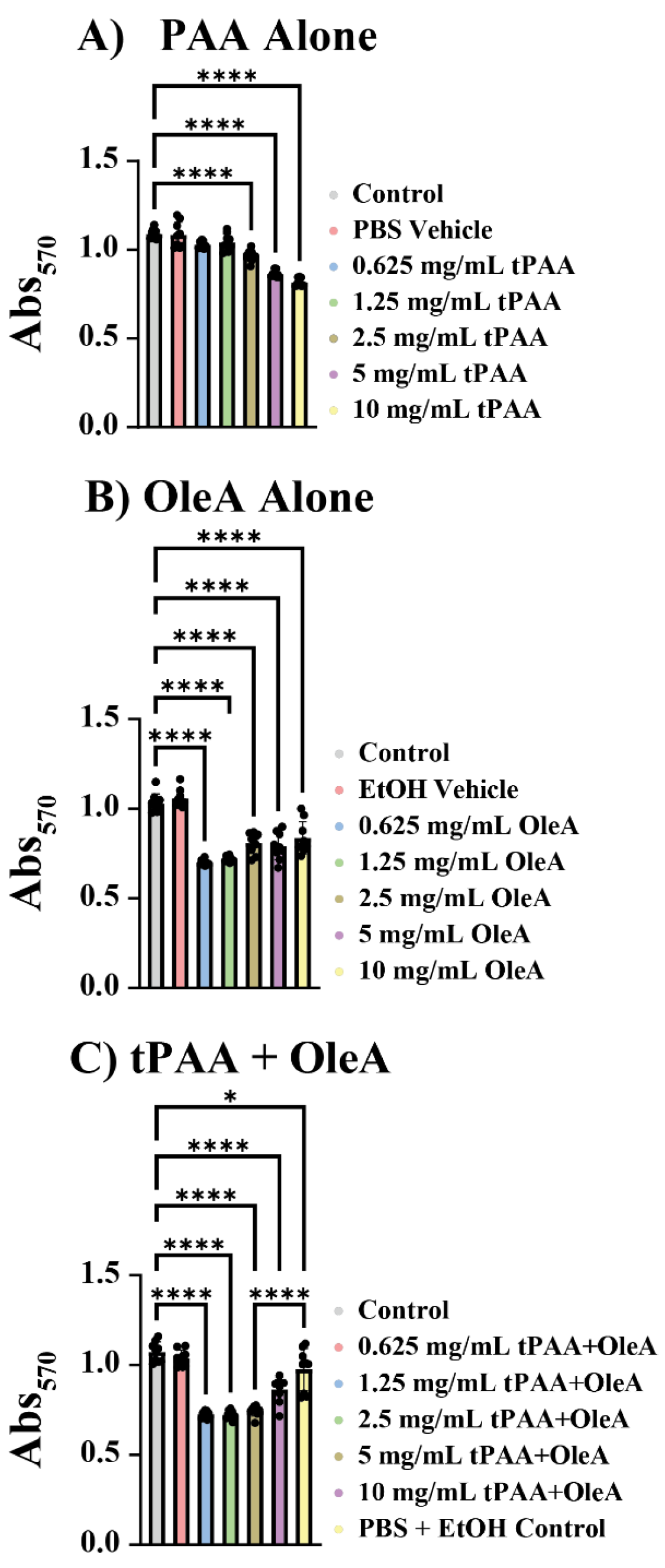

3.5. Cytotoxicity Assessment Reveals Preliminary Therapeutic Windows

To evaluate the biocompatibility of antimicrobial coating components for potential medical device applications, we assessed cytotoxicity against 3T3 murine fibroblasts using the MTT viability assay. tPAA demonstrated a dose-dependent cytotoxic profile with relatively modest effects across the tested concentration range (

Figure 7A). At concentrations up to 1.25 mg/mL, tPAA showed minimal cytotoxicity with cell viabilities remaining above 95% of untreated controls. However, higher concentrations produced statistically significant reductions in cell viability, with 5 mg/mL and 10 mg/mL treatments reducing viability to 79% ± 0.02 and 75% ± 0.02, respectively (****

p < 0.0001).

OleA exhibited a more complex cytotoxicity profile characterized by pronounced effects at intermediate concentrations (

Figure 7B). Unexpectedly, the highest cytotoxic effects were observed between 0.625 mg/mL and 2.5 mg/mL concentrations, which reduced cell viability to 69% ± 0.01, 72% ± 0.02, and 80% ± 0.06 of control values, respectively (****

p < 0.0001). Remarkably, the 10 mg/mL OleA treatment showed significantly reduced cytotoxicity compared to intermediate concentrations (***

p ≤ 0.001), with cell viability recovering to 83% ± 0.09 of control values.

The non-linear cytotoxicity profile observed with OleA suggests that the compound’s surfactant properties and critical micelle concentration (CMC) may play important roles in determining cellular toxicity. At intermediate concentrations, OleA likely exists primarily as free fatty acid molecules that can readily interact with cellular membranes, potentially causing membrane disruption and cytotoxicity [

23]. However, at higher concentrations exceeding the CMC, OleA may form micelles that could sequester the cytotoxic free fatty acid molecules, reducing their availability for membrane interaction [

25]. The most intriguing findings emerged from the analysis of combined tPAA + OleA treatments (

Figure 7C). At the highest tested concentration of 10 mg/mL, the combined treatment showed significantly reduced cytotoxicity, with a cytotoxic effect of less than 10% compared to tPAA and OleA alone at 25% and 18%, respectively (****

p < 0.0001).

It should be noted that the MTT assay, while widely used and validated for cytotoxicity screening, represents one of several approaches for assessing biocompatibility. Alternative assays such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release (for membrane integrity), ATP-based luminescence (for metabolic activity), or live/dead fluorescence imaging (for spatial distribution of viable cells) could provide complementary mechanistic information about cytotoxic effects. The MTT assay was selected for this proof-of-concept study due to its established use and suitability for screening applications, but more comprehensive cytotoxicity profiling would be appropriate for subsequent development stages.

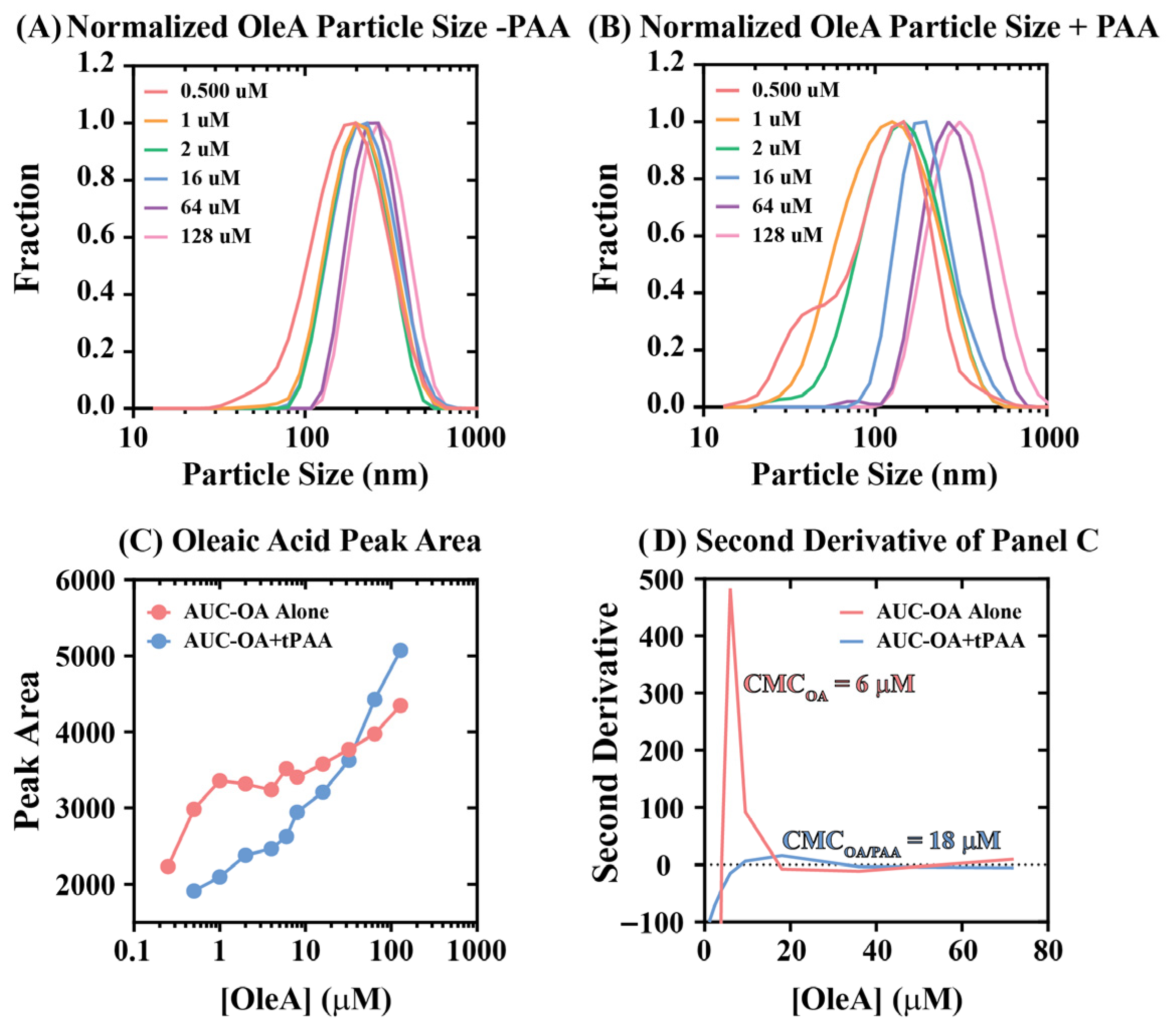

3.6. Preliminary Physicochemical Basis for Coating Interactions in Cytotoxicity

The unique cytotoxicity behaviors for coatings involving OleA alone or tPAA + OleA presented in

Figure 7C demonstrate that intermediate treatment concentrations yield greater cytotoxicity relative to high concentrations. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that OleA self-assembles to form micellar structures in a concentration-dependent manner with a critical micelle concentration of approximately 6 μM. To assess whether this explanation accounts for the observed cytotoxicity trends, dynamic light scattering (DLS) experiments were performed to report average particle size as a function of [OleA] (

Figure 8A,B).

In the absence of tPAA, oleic acid demonstrated characteristic surfactant aggregation behavior with relatively narrow particle size distributions that shifted from ~146 nm to ~267 nm across [OleA] from 0.25 to 128 μM. The addition of tPAA altered oleic acid aggregation patterns, with particle size distributions shifting from ~146 nm to ~310 nm across the same concentration range.

Second derivative analysis of the peak area data presented in

Figure 8C enabled estimation of critical micelle concentrations for both OleA alone and OleA + tPAA combinations (

Figure 8D). The analysis revealed that OleA alone exhibits a CMC of approximately 6 μM, consistent with literature values for oleic acid under physiological conditions. Remarkably, tPAA addition shifted the effective CMC to approximately 18 μM, representing a threefold increase in the concentration required for micelle formation. This CMC shift provides a plausible mechanistic hypothesis for understanding the cytotoxicity effects observed in

Figure 7. Below the CMC, fatty acids exist primarily as monomers that readily insert into cellular membranes causing cytotoxicity. Above the CMC, fatty acids are sequestered into micelles where they become less available for membrane interaction. While this provides a plausible explanation for the observed cytotoxicity patterns, future work should establish causal relationships through direct membrane interaction studies and concentration-dependent cytotoxicity mapping at higher resolution.

The polyanionic nature of tPAA may facilitate this CMC shift through electrostatic interactions with oleic acid carboxylate head groups, effectively raising the concentration threshold required for complete micelle assembly. The result may be a broader concentration range where OleA exists in intermediate aggregation states that retain antimicrobial activity while exhibiting reduced cytotoxicity. Together, these findings suggest that enhancement effects of ordered tPAA + OleA coatings may extend beyond simple additive antimicrobial activities to encompass modulation of fatty acid physical chemistry that could enhance both efficacy and safety profiles, though this hypothesis requires additional experimental validation.

4. Limitations and Future Directions

While this proof-of-concept study demonstrates that ordered tPAA-OleA coatings can produce enhanced antimicrobial effects relative to individual compounds, several important limitations must be acknowledged and should guide future investigation. These limitations are described below.

4.1. Limited Strain Diversity and Sample Size

This study examined one strain of P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27855) and one laboratory strain of E. coli (BL21-DE3). Clinical translation would require testing against diverse clinical isolates, including multiple ESKAPE pathogens, and strains with varying resistance profiles. The use of BL21(DE3), a laboratory strain optimized for protein expression, may not fully represent the behavior of pathogenic E. coli strains in clinical settings. Additionally, all experiments were performed in triplicate, which, while standard practice for preliminary microbiological studies, represents a modest sample size. Future validation studies should incorporate larger sample sizes to confirm reproducibility and enable more precise effect size estimation.

4.2. PAA Biodegradability Concern

As noted in the introduction, certain bacteria such as Sphingomonas sp. produce enzymes (PahZ1/PahZ2) capable of degrading thermally synthesized PAA. While Sphingomonas sp. have been reported in hospital environments and can co-inhabit biofilms with P. aeruginosa, the present study did not assess whether PAA-degrading organisms would compromise coating efficacy over extended periods or in polymicrobial biofilms. Future work should: (1) test coating stability in the presence of known PAA-degrading organisms, (2) assess performance in mixed-species biofilm models, and (3) evaluate whether either P. aeruginosa or E. coli develop PAA-degrading capabilities. If PAA degradation proves problematic, chemical modifications to create non-degradable PAA analogs may be necessary.

4.3. Mechanistic Uncertainty

While we propose mechanisms involving bacterial membrane disruption, surface charge modification, and extracellular DNA interaction, direct experimental validation of these mechanisms was not performed in this initial study. This limitation reflects our experimental design choices appropriate for a proof-of-concept investigation, which prioritized establishing whether enhanced antimicrobial effects could be achieved through ordered coating application, rather than inherent limitations of the coating concept itself. The reduction in extracellular DNA observed by confocal microscopy is consistent with disrupted biofilm development but does not establish whether this is a primary mechanism of action or a downstream consequence of bacterial death. Additionally, our biofilm assays cannot distinguish between inhibition of biofilm formation versus disruption of established biofilm; experiments applying coatings to pre-formed biofilms would be needed to establish this distinction.

4.4. In Vitro Limitations

All experiments were conducted under static culture conditions that do not replicate the flow dynamics present on medical devices such as catheters or implants. Flow cells or CDC biofilm reactors would provide more clinically relevant conditions. Additionally, biofilm quantification relied primarily on crystal violet staining, which measures total biomass rather than cell viability. Planktonic growth was monitored using OD600 measurements, which enable continuous kinetic monitoring but do not directly enumerate viable cells. Future work should incorporate CFU enumeration to confirm that observed OD600 reductions correspond to reductions in viable cell numbers rather than changes in cell morphology or aggregation state.

4.5. Polymicrobial Infection Considerations

The differential susceptibility of P. aeruginosa versus E. coli to our coating systems has important implications for clinical applications. Healthcare-associated infections frequently involve polymicrobial biofilms, and coating efficacy in such contexts may be complex and dependent on community composition. Organisms with lower susceptibility to coating treatments could potentially be selected for in treated environments, altering infection dynamics. Testing against polymicrobial biofilm models is an essential direction for future investigation to establish coating efficacy in more clinically realistic scenarios.

4.6. Clinical Application Considerations

The coating methodology described here could potentially be applied to various medical device surfaces, including wound dressing materials that contact surgical sites, suture materials (coated during manufacturing), surgical implants or prosthetic devices, and catheter surfaces. It is important to note that direct application of these coatings to open wound tissue is not the intended application; rather, the coatings would be applied to medical device surfaces that subsequently contact tissue. Translation to specific medical device applications would require device-specific optimization of coating parameters, stability testing under relevant use conditions, and appropriate regulatory evaluation that are beyond the scope of this proof-of-concept work.

4.7. Coating Characterization Limitations

Several important coating characteristics were not assessed in this proof-of-concept study and should be addressed in future development work. Coating thickness was not measured; profilometry or cross-sectional electron microscopy would be required for accurate thickness determination. Coating stability under continuous liquid exposure was not systematically assessed beyond the wash retention studies; extended exposure studies with periodic sampling would better characterize long-term stability. The hydrophilic/hydrophobic nature of the final coating surface was not directly characterized, though the hydrophobic nature of OleA and hydrophilic nature of tPAA suggest that surface properties depend on coating order (i.e., OleA-terminated coatings would be expected to be more hydrophobic than tPAA-terminated coatings). Layer-specific exposure of coating components to bacterial cultures was inferred from coating order but was not directly verified. These characterization parameters are essential for understanding coating behavior and should be incorporated into future optimization studies.

5. Conclusions

This proof-of-concept investigation demonstrates that ordered tPAA-OleA coating systems can produce enhanced antimicrobial effects compared to individual compounds against P. aeruginosa and E. coli under laboratory conditions. The observation that tPAA-first application produces superior efficacy compared to OleA-first application suggests that coating sequence is an important parameter for optimization. The species-specific efficacy profiles, particularly the notable effects against P. aeruginosa, including up to 62% reductions in carrying capacity and 43% biofilm reduction over 24 h, suggest these coating systems warrant continued investigation.

The cytotoxicity assessment revealed potentially favorable protective interactions between tPAA and OleA, with combined treatments showing reduced toxicity compared to OleA alone at equivalent concentrations. Dynamic light scattering analysis provided a plausible physicochemical explanation for this observation through tPAA-mediated modulation of oleic acid critical micelle concentration, though causal validation of this mechanism is needed. However, several important limitations must inform the interpretation of these findings. This study examined only single strains of two bacterial species under static culture conditions, did not assess coating stability in the presence of PAA-degrading organisms, and did not provide direct mechanistic validation of proposed modes of action. Clinical translation would require substantial additional work, including (1) testing against diverse clinical isolates and ESKAPE pathogens; (2) validation under flow conditions relevant to medical devices; (3) assessment of coating stability and performance in polymicrobial biofilms; (4) comprehensive mechanistic studies using membrane integrity assays and transcriptomics; (5) biocompatibility testing with primary human cells; and (6) in vivo efficacy and safety evaluation.

Within the context of these limitations, this work establishes proof-of-concept that ordered tPAA-OleA coating systems represent a promising direction for future antimicrobial coating development. The findings provide both preliminary evidence of enhanced antimicrobial activity and specific hypotheses regarding mechanisms that can guide future investigation toward the goal of developing coating technologies for preventing medical device-associated infections.