Abstract

A batch of drill pipe joints in a well cracked and failed due to hardbanding. In this study, various experiments were conducted to analyze the reasons for cracking failure, including data verification, macroscopic morphology analysis, mechanical properties, microstructure analysis, and micro-Vickers hardness of cracked areas, as well as macroscopic, metallographic, and energy spectrum analysis of the fracture surface after opening the cracked area. The results indicated that (1) the chemical composition, tensile strength, Charpy impact test, and Brinell hardness results of the joint met the requirements of the order technical conditions. (2) The hardbanding in the cracked area had multiple pores and cracks on its outer surface and inside. The maximum diameter of the internal porosity was about 3.4 mm, and the length of the internal crack was about 1 mm. (3) The main reason for the cracking of a batch of drill pipe joints due to hardbanding is a quality problem of the secondary repair welding of the hardbanding. The cracks in the failed drill pipe originated from the porosity and cracks in the hardbanding of the drill pipe box joint. Under the influence of alternating stress and high-pressure mud erosion underground, the cracks rapidly extended to the inner wall, and the porosity in the hardbanding accelerated crack propagation, ultimately causing the drill pipe to crack and fail.

1. Introduction

Friction and wear between the drill pipe and casing are inevitable during oil drilling operations and, in severe cases, can cause deformation or even collapse of the casing, leading to drill pipe fracture [1]. Based on the failure accidents and economic losses caused by friction and wear, deep hole drilling poses a challenge to the selection of drilling materials. Hard alloy and wear-resistant strip technology for drill pipe joints are currently ideal material choices for drilling [2].

A large number of scholars have studied new materials for drill pipe joints, as well as wear-resistant hard alloys, diamond-like carbon films, iron-based pre-alloy powders, and new composite materials to improve the wear resistance and friction performance of drill pipe joints. Xiaohua Zhu et al. studied the influence of rock debris particle content on the frictional behavior of Fe/DLC at casing and drill pipe joints and researched the detailed damage mechanism on the friction interface from an atomic perspective [1]. John Truhan et al. evaluated drill shaft cladding materials for optimum friction and wear behavior against well casing materials lubricated by a drilling mud slurry [2]. Ting Xue et al. presented the role of the binder phase in enhancing the properties and holding ability of WC-based diamond hardbanding matrix [3]. Kai Zhang et al. investigated the effects of Ni content on the microstructures and mechanical properties of WC-based diamond composites, attempting to seek the optimal Ni addition concentration and alloy type [4]. Kai Zhang et al. conducted a study on the material properties and tool performance of PCD-reinforced WC matrix composites for hardbanding applications [5]. Xiaojun Zhao et al. studied and analyzed the effect of Fe-based pre-alloyed powder on the microstructure and holding strength of impregnated diamond bit matrix [6]. Shiyi Wen et al. evaluated thermal conductivity of two-phase WC Ni composite materials through microstructure-based models and key experiments [7]. Wenhao Dai et al. derived mechanical properties and microstructural characteristics of nano-NbC reinforced WC-bronze-based impregnated diamond composites [8]. Dan Belnap et al. presented homogeneous and structured PCD/WC-Co materials for drilling [9]. Yunhai Liu et al. investigated the tribological behaviors of diamond-like carbon film in a water-based drilling fluid environment by varying normal loads [10]. Kouami Auxence Melardot Aboua et al. proposed the wear mechanism of DLC film when rubbed against a steel disk [11]. Adnan Tahir et al. simulated the effect of substrate roughness on the adhesive strength of WC-Co coatings by finite element modeling and experiments [12]. M.R. Fernández et al. studied the friction and wear behavior of spherical WC-reinforced NiCrBSi laser cladding coating [13]. Song Zhao et al. analyzed tribological behavior of PDC cutting tools prepared under high pressure and high temperature (HPHT) using WC particles/Ta-20Nb binder composite material for drilling applications [14]. Huiyong Rong et al. proposed the wear mechanism of hardmetal YG8B [15].

As seen from the above research, most scholars have studied the friction and wear properties of hard alloys, while a small number of scholars have studied the wear resistance of welded hardbanding to improve wear resistance. Lilia Fedorova et al. proposed improving drill pipe durability by surfacing of the drill joint of the drill pipe with cored wire (hardbanding) [16]. Zhiqiang Huang et al. studied the friction and wear mechanisms of three coatings, including welding hardbanding using oxyacetylene flame bead weld (BW) [17]. Jun Liu et al. studied microstructure and wear resistance performance of Cu–Ni–Mn-alloy-based hardfacing coatings reinforced by WC particles [18].

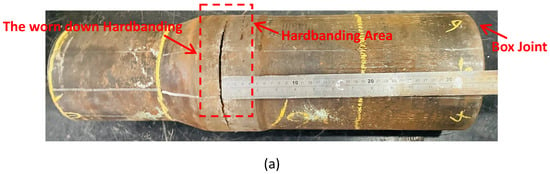

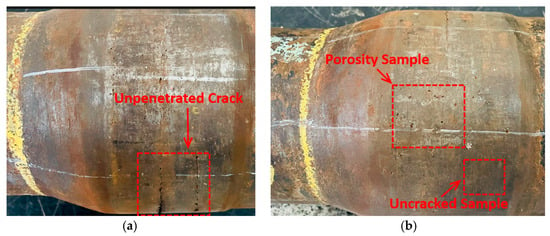

Few studies have focused on defects in hardbanding. Currently, only G.V.S. Murthy et al. has studied the main reason for the failure of hardbanding of a heavyweight drill pipe [19]. However, there are currently no reports on the failure of hardbanding caused by porosity and cracking issues, which are very essential for the hardbanding lifetime in service. In this study, during the tripping-out process, a batch of drill pipes in a well cracked and failed from the hardbanding near the internal thread joint. Further research on the causes of cracking in the hardbanding of this batch of drill pipes is of great significance for formulating preventive measures and preventing accidents from happening again. The morphology of site failed drill pipe is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Morphology of site failed drill pipe. (a) Cracking area of drill pipe, (b) morphology of cracking of hardbanding.

In order to find the main reason for cracking, data verification, macroscopic observation, physical and chemical inspection of the drill pipe, microstructure, properties, scanning electron microscopy, and energy spectrum analysis of the cracked area from hardbanding to the drill pipe body were carried out. The microstructure of the uncracked area from hardbanding to the drill pipe body was also analyzed. Finally, the failure reason for cracking was analyzed and the mechanism of crack initiation and propagation in the hardbanding zone was further studied, as well as the role of welding porosity and residual stress in generating cracks.

2. Data Verification

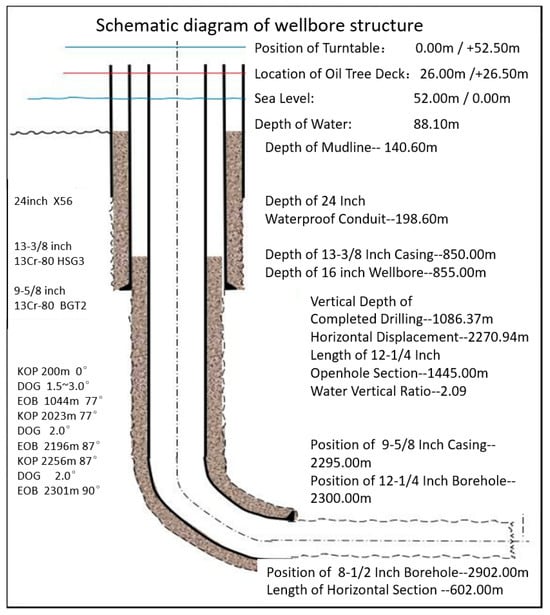

The schematic diagram of the service wellbore structure of the cracked drill pipe is shown in Figure 2. Drilling tool assembly for drilling 8-1/2″ holes is 8-1/2″PDCBit + 3/4″Xcel + 6-3/4″PeriScope + 6-3/4″EcoScope + 6-3/4″TruLink + 6-3/4″NMDC + 6-3/4″Filter Sub + 6-3/4″Float Sub + X/O (NC50 PIN × GPDS50 BOX) + 5″HWDP × 3 + X/O (GPDS50 PIN × NC50 BOX) + 6-1/2″Hydraulic JAR + X/O (NC50 PIN × GPDS50 BOX) + 5″HWDP × 5. Drilling parameters are WOB 5–8 klbs, FLW 2340–2370 L/min, SPP 1750–1910 psi, RPM 60–100 rpm, TQ19-34klbs·ft. The wellbore wall is trimmed twice after drilling one column. According to geological guidance requirements, the speed is controlled at ROP < 50 m/h.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of wellbore structure.

On 23 January 2024, from 00:00 to 06:15, directional drilling of the 8-1/2″ wellbore was completed from 2718 m to 2849 m. From 06:00~07:00, circulating cleaning of the wellbore was carried out, during which the pump pressure continued to drop to 9.2 MPa (1335 psi), the turbine speed decreased from 3720 rpm to 2810 rpm, the reflux was normal, and the circulation was stopped. From 07:00~11:45, top drive drilling from 2849 m to 2261.5 m inside the casing shoe was carried out. The drilling process was smooth and the grouting volume was normal. Before drilling, the overflow was monitored for 15 min without any overflow or leakage. When the drilling reached 2318 m, it was found that there was a 3/4 circumferential crack on the hardbanding of the drill pipe box joint on the 5-7/8″ drill pipe of the 52nd column, with a crack width of 1 cm and a length of 12 cm. From 11:45~18:15, drilling from 2261.5 m to 123 m was carried out. The grouting volume was normal during the drilling process. During the drilling process, it was discovered that there were multiple pores and cracks on the surface of the hardbanding of 10 5-7/8″ box joints (as shown in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Morphology of porosity and cracks in the hardbanding of drill pipe. (a) The porosity morphology of hardbanding, (b) the porosity and crack morphology of the hardbanding.

The grade of the cracked 5-7/8″ drill pipe is S135, the outer diameter and inner diameter of the internal threaded joint of the failed drill pipe are 7″ and 4-1/4″, respectively, and the buckle type is XT57. The ordering technical condition is Quality Documentation Package. The hardbanding model is TCS Ti, which is made by secondary hardfacing.

3. Materials and Experimental Methods

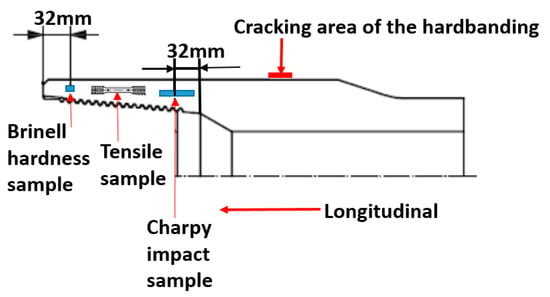

In order to analyze the cracking reason, a series of experiments were carried out. The chemical composition of the internal thread joint was analyzed using ARL 4460 direct reading spectroscopy according to ASTM A751-21 [20]. The round-bar tensile specimen with a gauge of Φ12.7 × 50 mm was intercepted longitudinally on the internal thread joint. The tensile properties were tested using an UTM5305 testing machine (produced by Shen Zhen Sens Test Instruments Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) according to ASTM A370-24 [21]. The Charpy impact energy of the internal thread joint was measured on a PIT302D impact tester (produced by Shen Zhen Sens Test Instruments Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) at −20 °C according to ASTM A370-24 [21]. The Brinell hardness of the internal thread joint surface and the Rockwell hardness of the full wall thickness of the internal thread joint were tested according to ASTM E10-18 [22] and ASTM E18-22 [23] standards, respectively. The sampling locations for tensile, Charpy impact, and Brinell hardness samples are shown in Figure 4. The microstructures, grain sizes, and non-metallic inclusions of the failed samples were analyzed. Subsequently, in accordance with ASTM E3-11 (2017) [24], ASTM E45-18a [25], ASTM E112-24 [26], and GB/T 34474.1-2017 [27], the low- and high-magnification morphologies of the cracked location were obtained. The unperforated crack sample, hardbanding porosity sample, and uncracked sample were taken for metallographic analysis. And a full wall thickness micro-Vickers hardness test was conducted on the hardbanding to the drill pipe joint substrate. The 3/4 circumferential crack on the hardbanding of the internal thread joint was mechanically opened. Then the fracture morphology and corrosion products were analyzed using VEGAI scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (produced by TESCAN, Ostrava, Czech Republic) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). The samples of the drill pipe box joint were taken from one of the cracked drill pipes of this batch, and the experimental conditions and parameters were according to standard requirements, representing the performance of the drill pipe joints of this batch.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of sampling locations for tensile, Charpy impact, and Brinell hardness.

4. Results

4.1. Macroscopic Observation

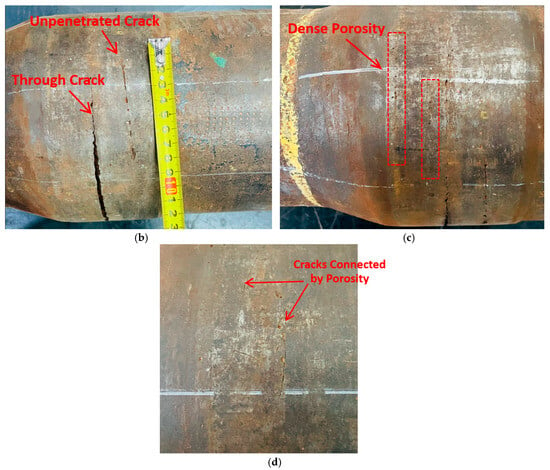

The hardbanding on the end of the internal threaded joint of the failed drill pipe has been worn down. There is a 3/4 circumferential crack on the hardbanding which is about 350 mm away from the internal thread end. There is a transverse crack of about 80 mm near the through crack, and there are multiple dense holes near the through crack of the hardbanding, which connect into the strip and form the crack. The maximum crack opening width along the length is 3 mm, and the geometry of the hardbanding wear zone is like a belt. It can be seen that the cracking starts from the outer surface of hardbanding of the box joint, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Morphology of the failed drill pipe. (a) The overall morphology of the failed drill pipe for inspection, (b) morphology of the through crack and unpenetrated crack, (c) dense porosity formed the strip morphology, (d) cracks connected by porosity.

As shown in Figure 6, after longitudinally cutting open the box joint, it is found that the inner wall coating is intact, and there is no obvious damage to the coating near the through crack, and the crack is filled with residual deposit inside.

Figure 6.

The inner wall morphology of the through crack.

4.2. Mechanical Performance Tests

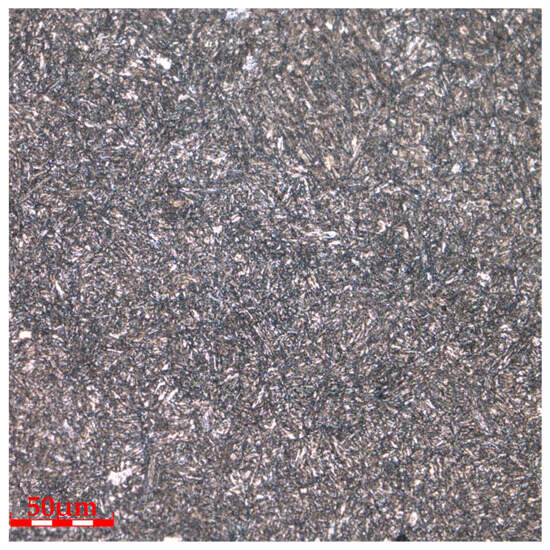

The chemical analysis, tensile test, Charpy impact test, Brinell hardness test, and Rockwell hardness test results of the failed box joint are shown in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. The chemical analysis, tensile test, Charpy impact test, and Brinell hardness test results of the failed drill pipe box joint are all in accordance with the requirements of Quality Documentation Package. The Rockwell hardness test results of the box joint indicate that its hardness is reasonable. From the metallographic analysis results, it can be seen that the microstructure of the failed drill pipe box joint is tempered sorbite, with small and uniform grain size, as shown in Table 6 and Figure 7.

Table 1.

Chemical analysis results of the failed drill pipe box joint (wt.%).

Table 2.

The tensile test results of the failed drill pipe box joint.

Table 3.

The Charpy impact test results of the failed drill pipe box joint.

Table 4.

Brinell hardness test result of the failed drill pipe box joint.

Table 5.

Rockwell hardness test result of the failed drill pipe box joint.

Table 6.

Microscopic analysis results of the failed drill pipe box joint.

Figure 7.

Metallurgical structure of the failed drill pipe box joint.

4.3. Metallographic Analysis of Three Locations

The unpenetrated crack sample, hardbanding porosity sample, and uncracked hardbanding sample are taken for metallographic analysis, and the schematic diagram of the samples’ locations is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of metallographic samples’ locations. (a) Unpenetrated crack sample, (b) porosity sample and uncracked sample.

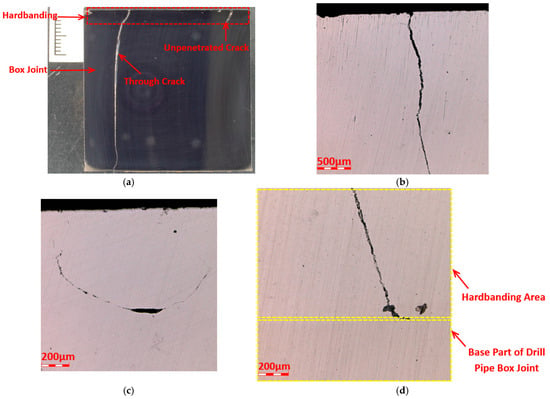

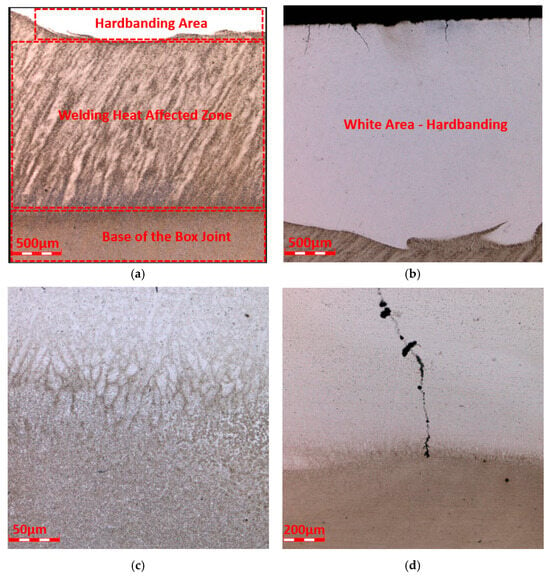

The cracked cross-section specimen was ground and polished, then the longitudinal section was observed. It can be seen that the unpenetrated crack next to the through crack extends from the surface of the hardbanding towards the base of the drill pipe box joint, with a depth of about 2.2 mm. In addition, there are many small cracks on the outer surface of the hardbanding, most of which extend radially towards the base of the drill pipe box joint, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Crack morphology of hardbanding. (a) Macroscopic morphology of through and unpenetrated crack sections, (b) surface microcrack morphology of hardbanding, (c) microscopic crack morphology inside the cross-section of hardbanding, (d) morphology of the crack extending from hardbanding to the base of the drill pipe box joint.

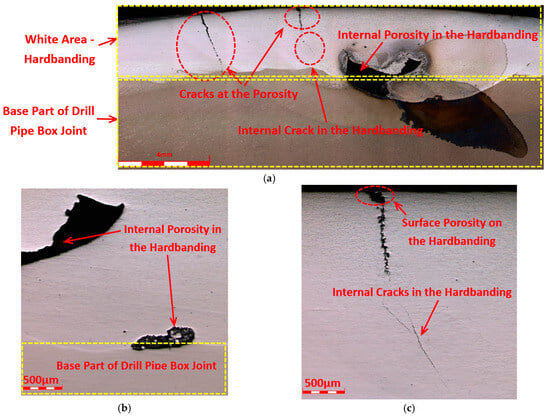

From the metallographic cross-section sample with hardbanding porosity, it can be found that there are multiple pores and cracks on the outer surface and inside of the hardbanding. The maximum diameter of the pores is about 3.4 mm, and the length of the internal crack is about 1 mm. According to clause 16.0 of the TCS Ti hardbanding acceptance criteria provided by the client, the size of pores is limited to no greater than 1.6 mm in diameter. There are cracks on the outer surface porosity of the hardbanding, which extend radially to the base of the drill pipe box joint, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Porosity and cracks of the hardbanding. (a) Macroscopic morphology of porosity and cracks on the surface and interior of hardbanding, (b) microscopic morphology of internal porosity in the hardbanding, (c) microscopic morphology of surface porosity, cracks, and internal cracks in the hardbanding.

In areas where porosity appears densely, there is an average of one hole every 3 mm, the diameter of these small holes is approximately 1 mm to 2 mm, and they formed a strip, as shown in Figure 5c. The porosity on the hardbanding is caused by gas entrapment from various contaminant or impurity sources during the weld. If there are pores during the welding of hardbanding, the strength of the material around the pores will decrease, becoming a stress concentration point, which can easily cause a sudden increase in local stress and expansion under stress. If there are cracks or burrs at the edge of the hole, it will further weaken the material strength and cause the stress area to rapidly expand. During the service of the drill pipe, dynamic impact force is generated at the joint, and the hole will accelerate crack propagation, especially in the case of a large aperture. Stress waves absorb more energy, leading to more severe damage. From this, it can be inferred that these strip-shaped holes are further subjected to force and can easily form cracks.

From the cross-section of the uncracked sample, the image analysis shows that the microstructure of the drill pipe box joint is divided into three areas. The external surface area is the bright white layer on top, which is the hardbanding after service, with a thickness of about 2 mm. The middle area is the welding heat-affected zone. The third area is the base of the box joint. Many small cracks are also found on the sample, and some cracks have directly extended from the surface of the hardbanding to the base of the box joint, as shown in Figure 11. Once the crack extends to the base of the drill pipe joint, under service stress, without the protection of hardbanding, the crack of the drill pipe joint will further propagate until it completely cracks.

Figure 11.

Full wall thickness section microstructure and crack morphology of uncracked samples. (a) Three areas of microstructure with full wall thickness, (b) hardbanding morphology, (c) microstructure morphology of heat-affected zone and base of drill pipe joint, (d) crack morphology extending from hardbanding to base of drill pipe joint.

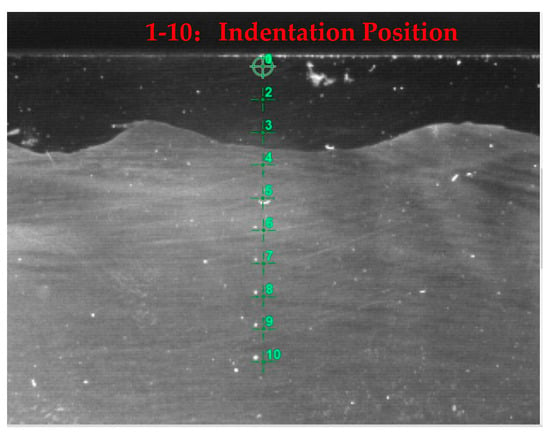

4.4. Micro-Vickers Hardness Test for the Full Wall Thickness of Drill Pipe Joint

A micro-Vickers hardness test was performed on a cross-section of the full wall thickness of the drill pipe joint in accordance with ASTM E384-17. The distribution diagram of the hardness test locations is shown in Figure 12, and the test results are reported in Table 7. These results show that the Vickers hardness on the outer surface of the hardbanding reaches 712HV0.5 and the micro-Vickers hardness of the hardbanding near the heat-affected zone is 585HV0.5.

Figure 12.

Schematic diagram of indentation position in micro-Vickers hardness test.

Table 7.

Results of micro-Vickers hardness test (HV0.5).

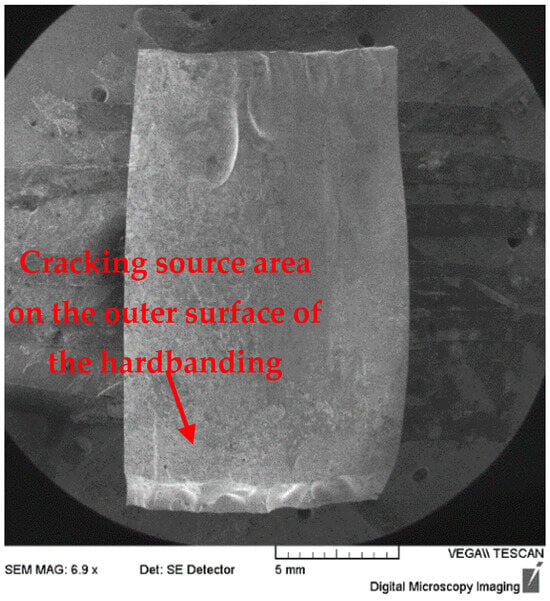

4.5. Fracture Analysis of Through Crack

The through crack was mechanically opened, and the macroscopic morphology of the fracture surface is shown in Figure 13. The fracture surface with river pattern morphology is formed by high-pressure mud erosion after the crack is penetrated, and the surface is relatively smooth and flat. There are still some brown corrosion products remaining on the fracture surface. From the macroscopic fracture morphology, it can be inferred that the crack arises from the outer surface of the hardbanding. After the crack propagated to the inner wall and penetrated, the joint was subjected to high-pressure mud erosion and various external stresses, and the crack propagation was relatively rapid and smooth.

Figure 13.

Macroscopic morphology of the fracture surface of the through crack.

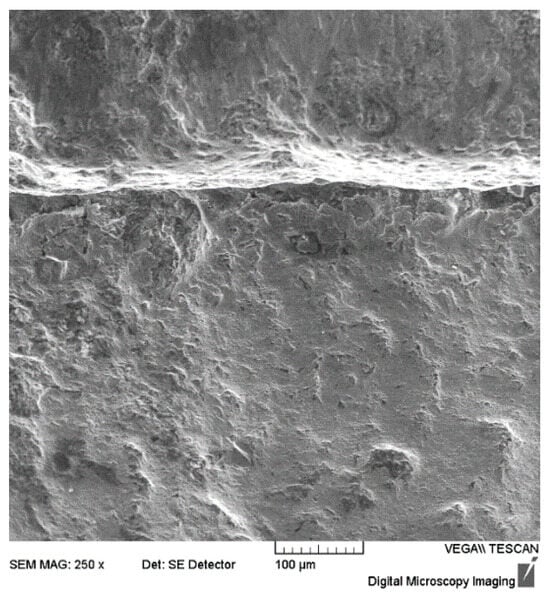

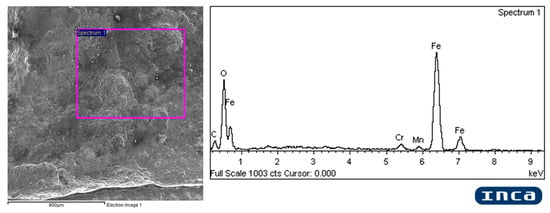

As shown in Figure 14 and Figure 15, the morphology of the fracture surface is observed using scanning electron microscopy. Due to the erosion, its original morphology has been covered by corrosion products. The residual deposition at the fracture site is mainly formed by the deposition of environmental materials after cracking. And then the corrosion products on the fracture surface are analyzed using an energy spectrometer. The analysis results are shown in Figure 16. It turns out that the primary elements of the corrosion products are Fe, C, and O, simultaneously accompanied by a small amount of Mn and Cr.

Figure 14.

Scanning electron microscope sample.

Figure 15.

Scanning electron microscope photo of the fracture surface.

Figure 16.

The curve of corrosion products and the position of the energy spectrum analysis.

4.6. Line Scanning Analysis of Hardbanding Area

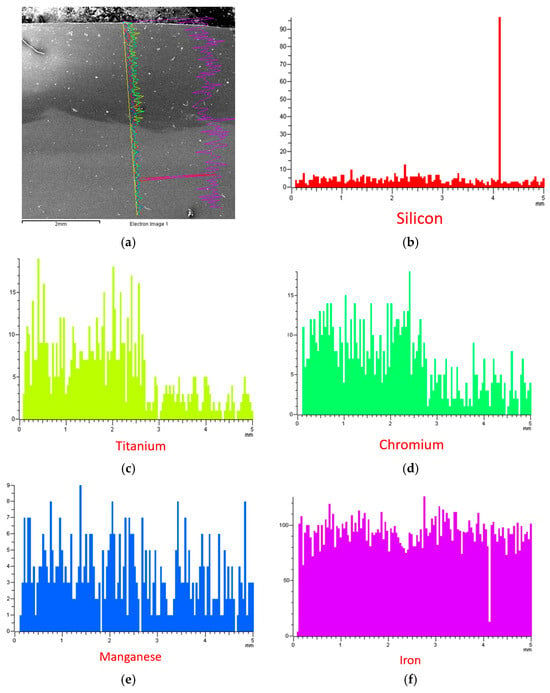

The distribution trend of elements from the surface of the hardbanding to the base of the drill pipe joint was analyzed using line the scanning energy spectrum analysis method, and the analysis results are shown in Figure 17. It turns out that the main components of the hardbanding are Si, Ti, Cr, and Mn.

Figure 17.

Line scanning analysis results of the hardbanding to the base of the drill pipe joint. (a) Scanning position and scanning image, (b) scanning curve of Si, (c) scanning curve of Ti, (d) scanning curve of Cr, (e) scanning curve of Mn, (f) scanning curve of Fe.

5. Analysis and Discussion

5.1. Material Factor of Drill Pipe

According to the performance test results of the drill pipe box joint, it can be concluded that there are no defects in the material of the failed joint. From this, it can be seen that the key role for the cracking failure of the drill pipe joint is played by welding defects in the hardbanding in the absence of obvious deviations in the base material and service overload operations.

5.2. Welding Quality of the Hardbanding

The hardbanding model is TCS Ti, which is made by secondary hardfacing. The microstructure of the drill pipe joint from the outer surface to the inner surface of the hardbanding is as follows: bright white layer of the hardbanding with a thickness of about 2 mm, welding heat-affected zone, and drill pipe joint matrix microstructure (as shown in Figure 11).

The outer surface of the hardbanding has multiple pores, which are connected in a strip shape and form cracks. Multiple pores and microcracks are also found inside the hardbanding. The maximum diameter of the internal porosity is about 3.4 mm, and the length of the internal crack is about 1 mm. Even on the macroscopic uncracked hardbanding, there are also many cracks, and most cracks have extended from the hardbanding to the base of the drill pipe joint. The reason for the formation of microcracks inside the hardbanding is that the hardbanding has undergone secondary hardfacing, resulting in high residual stress and the formation of microcracks.

The porosity of the hardbanding includes pores formed during the welding process. According to clause 16.0 of the TCS Ti hardbanding acceptance standard provided by the client, the porosity in the hardbanding is unacceptable and needs to be repaired. And during the welding process, its size is limited to 1.6 mm, and once worn and used, its size is limited to 3.2 mm.

The possible reasons for the porosity in the hardbanding are the following factors caused by secondary hardfacing.

(1) The surface of the hardbanding after the first welding is not cleaned or not cleaned properly. The base material needs to be cleaned thoroughly. If there is oil, soil, or paint on it, it needs to be removed, otherwise porosity will be generated during welding.

(2) The welding wire is affected by damp. Welding wire that is damp or rusted is more prone to porosity.

(3) Whether the gas purity meets the standard requirements. Based on on-site service experience, it is found that impure gas is one of the main reasons for porosity in welding.

(4) The welding gun nozzle should be kept at the specified technical distance from the base material according to the operating procedures, as a distance that is too large or too small can easily cause porosity.

(5) The angle and swing distance of the welding gun should also be according to the operating procedures, otherwise it will affect the welding quality.

(6) The current and voltage during the welding of the hardbanding should strictly comply with the recommended standards of the welding wire manufacturer.

The micro-Vickers hardness of the hardbanding from the outside to the inside is 712HV0.5, 634HV0.5, and 585HV0.5, respectively. There are two reasons for the higher micro-Vickers hardness on the outer surface of the hardbanding compared to its interior. Firstly, the outer surface of the hardbanding has undergone secondary hardfacing, and the micro-Vickers hardness of this area is higher than that of the first welding area. In addition, the outer surface of the hardbanding undergoes repeated friction during underground service, resulting in a higher micro-Vickers hardness on the outer surface.

5.3. The Wellbore Environment

No corrosive substances were detected in the service well of the drill pipe. CO2 is the most common associated gas of natural gas, which may not have been detected due to its low gas concentration. And drilling fluid contains a small amount of chloride ions. The aggressive environment with CO2 could accelerate crack growth and reduce the time to failure. The presence of chloride ions can also accelerate the rate of corrosion. The corrosion products on the surface of the crack fracture also indicate the corrosive environment.

5.4. Causes and Mechanism of Drill Pipe Joint Cracking

Based on the above analysis, it can be concluded that the main reason for the cracking of a batch of drill pipe joints on the hardbanding is the welding quality problems of the secondary repair welding of the hardbanding, which resulted in welding porosity and microcracks under residual welding stress in the hardbanding area. During underground service, a large number of pores connect into a strip and form the crack. Under the action of alternating stress and high-pressure mud erosion underground, the cracks continue to expand from the outside of the hardbanding to the base of the drill pipe joint, penetrating the entire thickness of the drill pipe joint, forming 3/4 circumferential cracks, and ultimately causing cracking and failure of the drill pipe box joint.

6. Conclusions and Suggestions

(1) The chemical analysis, tensile properties, Charpy impact test, and Brinell hardness results of the drill pipe joint met the requirements of the order technical conditions. The microstructure of the failed drill pipe box joint is tempered sorbite, with 9.0 grain size.

(2) There are a large amount of porosity and cracks on the surface and inside of the hardbanding. The maximum diameter of the internal porosity is about 3.4 mm, and the length of the internal crack is about 1 mm, which is unacceptable for TCS Ti hardbanding standards.

(3) The main cracking reason for the batch of drill pipe joints on the hardbanding is the welding quality problems of the secondary repair welding of the hardbanding. The cracking originated from the porosity and cracks of the hardbanding of the drill pipe box joint. Under the action of alternating stress and high-pressure mud erosion underground, the cracks rapidly extended to the inner wall, and the porosity in the hardbanding accelerated the cracks’ propagation, ultimately causing the drill pipe to crack and fail. This is based on the analysis of this batch of drill pipes and specific operating conditions, while other types of hardbanding and operating modes require additional research.

(4) It is recommended to inspect and study inspection methods and measures and strengthen the welding quality of the hardbanding to prevent similar accidents from occurring. The following approaches are suggested. ① Ensure that the surface of the hardbanding is clean before the secondary hardfacing. ② Keep the welding wire dry to prevent it from getting damp. ③ Adjust welding conditions to achieve a good weld effect. ④ Strictly implement the acceptable porosity levels during repairs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and D.L.; methodology, J.Z.; formal analysis, D.L. and F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z.; writing—review and editing, L.W.; project administration, F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Foundation of China National Petroleum Corporation Limited.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Jinlan Zhao, Dejun Li, and Feng Cao were employed by the company CNPC Tubular Goods Research Institute. Author Li Wang was employed by the company Bohai Petroleum Equipment Fujian Steel Pipe Co., Ltd. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zhu, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, B.; Mao, D. Effect of cuttings particle content on the tribological behavior of Fe/DLC at casing and drill pipe joints: A molecular dynamics study. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 396, 124006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truhan, J.; Menon, R.; LeClaire, F.; Wallin, J.; Qu, J.; Blau, P. The friction and wear of various hard-face claddings for deep-hole drilling. Wear 2007, 263, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Sun, L. Role of binder phase on properties and holding ability of WC based diamond hardbanding matrix. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2025, 131, 107184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, B.; Wang, Z. Effect of Ni content and maceration metal on the microstructure and properties of WC based diamond composites. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2020, 88, 105196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Y. Material properties and tool performance of PCD reinforced WC matrix composites for hardbanding applications. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2015, 51, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Duan, L.; Tan, S.; Fang, X. Effect of Fe-based pre-alloyed powder on the microstructure and holding strength of impregnated diamond bit matrix. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2019, 79, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Du, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tan, J.; Long, J.; Lou, M.; Chang, K.; Qiu, L.; Tan, Z.; Yin, L.; et al. Manipulation of the thermal conductivity for two-phase WC-Ni composites through a microstructure-based model along with key experiments. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 895–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Yue, B.; Chang, S.; Bai, H.; Liu, B. Mechanical properties and microstructural characteristics of WC-bronze-based impregnated diamond composite reinforced by nano-NbC. Tribol. Int. 2022, 174, 107777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belnap, D.; Griffo, A. Homogeneous and structured PCD/WC-Co materials for drilling. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2004, 13, 1914–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, T.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, X. Probing the tribological behaviors of diamond-like carbon film in water-based drilling fluid environment by varying normal loads. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2022, 130, 109552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboua, K.A.M.; Umehara, N.; Kousaka, H.; Deng, X.; Tasdemir, H.A.; Mabuchi, Y.; Higuchi, T.; Kawaguchi, M. Effect of carbon diffusion on friction and wear properties of diamond-like carbon in boundary base oil lubrication. Tribol. Int. 2017, 113, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, A.; Li, G.-R.; Liu, M.-J.; Yang, G.-J.; Li, C.-X.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Li, C.-J. Improving WC-Co coating adhesive strength on rough substrate: Finite element modeling and experiment. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 37, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.; García, A.; Cuetos, J.; González, R.; Noriega, A.; Cadenas, M. Effect of actual WC content on the reciprocating wear of a laser cladding NiCrBSi alloy reinforced with WC. Wear 2015, 324–325, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Li, C.; Davoodi, D.; Soltani, H.M.; Tayebi, M. Tribological behavior of PDC-cutter including cemented carbide and polycrystalline diamond composites produced by HPHT for drilling applications. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2024, 123, 106756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, H.; Peng, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wang, C.; Yue, W.; Fu, Z.; Lin, X. Dependence of wear behaviors of hardmetal YG8B on coarse abrasive types and their slurry concentrations. Wear 2011, 271, 1156–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, L.; Fedorov, S.; Ivanova, Y.; Voronina, M.; Fomina, L.; Morozov, A. Improving drill pipe durability by wear-resistant surfacing. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 30, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Yin, Z.; Wu, W. Experimental research on improving the wear resistance and anti-friction properties of drill pipe joints. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 2021, 73, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Xia, W.; Jiang, X.; Gui, C. Microstructure and wear resistance performance of Cu–Ni–Mn alloy based hardfacing coatings reinforced by WC particles. J. Alloy Compd. 2016, 654, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, G.; Das, G.; Das, S.K.; Parveen, N.; Singh, S. Hardbanding failure in a heavy weight drill pipe. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2011, 18, 1395–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM A751-21; Standard Test Methods and Practices for Chemical Analysis of Steel Products. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM A370-24; Standard Test Methods and Definitions for Mechanical Testing of Steel Products. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- ASTM E10-18; Standard Test Method for Brinell Hardness of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM E18-22; Standard Test Methods for Rockwell Hardness of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM E3-11 (2017); Standard Guide for Preparation of Metallographic Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM E45-18a; Standard Test Methods for Determining the Inclusion Content of Steel. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM E112-24; Standard Test Methods for Determining Average Grain Size. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- GB/T 34474.1-2017; Determination of Banded Structure of Steel-Part 1: Micrographic Method Using Standards Diagrams. China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2017.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.