Abstract

Simonkolleite (Zn5(OH)8Cl2·H2O), a layered double hydroxide, is used as a fast dry coating that can be applied onto different surfaces. Due to its rapid crystallization, some problems remain during its application, e.g., crack formation, low hardness, and limited compressive strength. To solve these challenges, we propose the harnessing of brown algae, a natural plague of the Caribbean, as a filler for Simonkolleite coatings. The influence of the addition of brown algae on the structural and morphological properties of the coatings was studied, with particular emphasis on their potential for improved durability and functional performance. The addition of the algae to the coatings favored microstructural compaction, resulting in a denser and mechanically more stable coating that exhibited higher hardness and compressive strength. Also, the presence of chlorophyll in the algae could promote light utilization for other emerging applications.

1. Introduction

Simonkolleite (Zn5(OH)8Cl2·H2O) is a layered double hydroxide (LDH) with a crystal structure composed of octahedral oxyhydrogen complexes centered on zinc tetrahedra of the ZnO3Cl complex, H2O molecules located between layers, and Cl atoms preferentially directed into the same interlayer space [1]. This LDH structure gives rise to interesting properties that have been explored in applications such as gas sensing [2], capacitors [3], corrosion protection of steel [4], photocatalysis [5], and even cytotoxicity against breast cancer cells [6]. However, most of these studies focus on bulk materials, while their application as coating has only been briefly investigated. Recently, our research group reported the fabrication of Simonkolleite coatings functionalized with photocatalytic nanoparticles for self-cleaning applications [7]. The results were promising; however, some challenges remain regarding the mechanical performance and stability of the Simonkolleite coatings, e.g., crack formation, low hardness, and limited compressive strength.

In general, there are several strategies to enhance the mechanical properties of coatings, such as grain size refinement [8], the addition of secondary phases [9], self-healing mechanisms [10], the control of residual stress [11], micro-arc oxidation [12], and fillers [13]. Common fillers used to improve coating hardness include carbon nanotubes, Al2O3, Si3N4 [14], AlN [15], WC, ZnO [16], TiO2 [7,17], and CaCO3 [18]. Additionally, organic fillers such as natural fibers [19], cellulose, chitin, and starch [20] can also be employed. In particular, the use of organic fillers derived from biomass waste has attracted increasing interest in recent decades due to their eco-friendliness, low cost, and favorable thermomechanical properties. These materials can be directly obtained from marine biomass, such as brown algae [21], which are considered invasive in certain regions of the Caribbean [22].

Brown algae such as Sargassum sp. have been used as a bio-filler in traditional building materials, e.g., Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), in different amounts (1%–20% wt.) [23,24,25,26]. In these reports, it was demonstrated that the load of algae is critical to maintain good mechanical performance and water absorption of the materials. Additionally, algae can act as a viscosity-enhancing agent [27], which promotes both self-sealing and self-healing of cracks. This phenomenon helps to mitigate chemical shrinkage because alginates (from the algae) can retain significant amounts of water, thereby supporting the hydration process and reducing early-age cracking. As a result, the mechanical strength of the material is improved. Thus, it is hypothesized that the addition of brown algae in SK systems could help address some challenges, e.g., crack formation. In a previous report, our group demonstrated that the addition of 5% wt. of Sargassum sp. and Lobophora sp. promoted the formation of a more compact microstructure that allows for maintaining the structural integrity of magnesium oxychloride (MOC) pastes [28]. Therefore, the use of brown algae as a filler for inorganic coatings like Simonkolleite represents a sustainable strategy to enhance their mechanical performance. Unlike conventional MOC binders, simonkolleite presents a layered crystalline structure and a characteristic plate-like morphology, which can interact uniquely with organic components from the algae, making SK potentially responsive to these natural biofillers; however, this interaction has not yet been studied. Thus, in this work, it is investigated if the addition of brown algae (Lobophora sp.) to SK coatings can promote densification, modify the hydration of pastes, or improve the water stability typically regarded as a limitation of chloride-based systems. This perspective has been absent from the existing literature and constitutes the main innovative contribution of the present research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fabrication of the Coatings

The reference coating (SK) was fabricated using zinc oxide (Pqmovel, Ciudad de México, Mexico) and zinc chloride (ZnCl2·xH2O) (DEQ, Monterrey, Mexico), and distilled water as raw materials. The brown algae (Lobophora sp.) were collected in Cozumel, Quintana Roo, Mexico. The collected samples were dried in an oven at 60 °C for 12 h. Once dry, the algae were ground manually in a mortar and then pulverized in a Fritsh pulverisette ball mill (Idar, Germany) for 10 min at 500 rpm to obtain powders. The mean particle size of the algae was 709 nm, as was previously reported [28]. The elemental composition of the brown algae used included C, O, Ca, S, Cl, and Na.

The weight ratio used for the fabrication of the coatings was 1:1:0.4 (ZnO:H2O:ZnCl2). In addition, a second sample was fabricated by the incorporation of 5% wt. of brown algae (Lobophora Lp.) into the mixture (SKBA). This content was selected based on previous research on similar pastes [28], due to the similarity between M2+-chloride (M=Zn, Mg) systems, which share similar precipitation mechanisms. Also, preliminary trials performed during this study confirmed that this loading favored adequate dispersion of the algae, maintaining adherence and integrity. The freshly prepared pastes were applied onto pre-cleaned porous concrete substrates using a stainless-steel spatula, forming a uniform SK layer. The coated substrates were then left to cure at room temperature for 24 h.

2.2. Characterization

The crystal phase of the samples was characterized by X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) using a Bruker D8 diffractometer (Karlsruhe, Germany) with CuKα radiation. The functional groups were monitored by FTIR spectrophotometry in a Nicolet iS50 (Massachusetts, USA). The morphology was investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a JEOL microscope JSM-6490LV (Tokyo, Japan). The surface area of the samples was measured by the Brunauer–Emmet–Taller (BET) method in a Quantachrome Instrument model Nova 2000e. The surface hardness tests were carried out by nanoindentation test using a Fischerscope model HM2000-5 nanoindenter (Sindelfingen, Germany) in three different locations of the coatings. A Vickers diamond pyramid indenter with a face angle of 136° was used with a dwell time of 60 s. The indentation hardness (HIT) and Young’s modulus (EIT) were obtained from the average values of the measurements by the WIN-HCU® software. Compressive strength tests were performed on three cubic samples of 1 × 1 × 1 cm3 using a Shimadzu AGX-Plus universal compressive testing machine. The strain rate used for the assays was 0.00167/s. The water resistance of the coatings was evaluated by the softening coefficient (SC) (Equation (1)):

where R(x, n) represents the compressive strength after soaking in water for 7 d and R(A, 7) represents the compressive strength after curing for 7 d.

3. Results

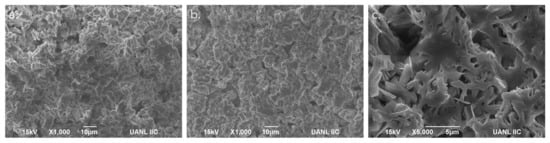

The incorporation of brown algae into the Simonkolleite coatings was investigated by different techniques to evaluate its effect on the physical and chemical properties of the resulting materials. Figure 1 shows the surface morphology of the reference Simonkolleite and the coatings modified with brown algae. At the same magnification (1000×), the images reveal a similarly compact morphology (Figure 1a,b); meanwhile, a closer analysis of the algae-modified sample shows morphological changes induced by its incorporation, including increased porosity at the micrometer scale and the formation of leaf-like features (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Micrographs of the (a). reference (SK) and (b,c). modified simonkolleite coatings with brown algae (SKBA).

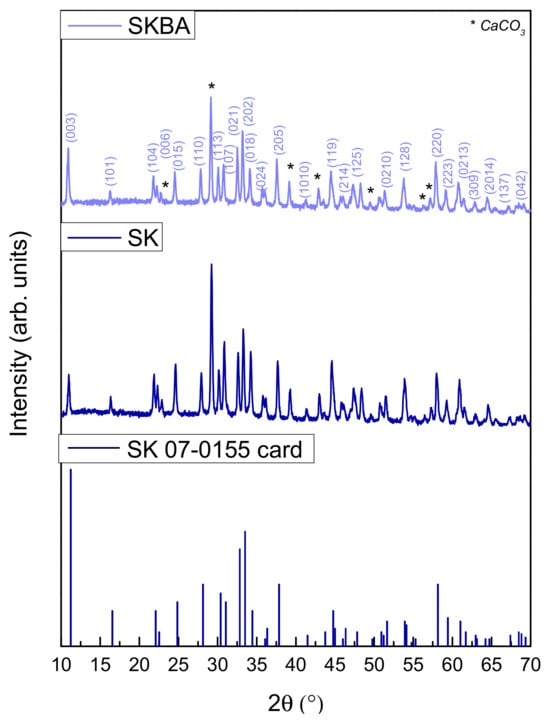

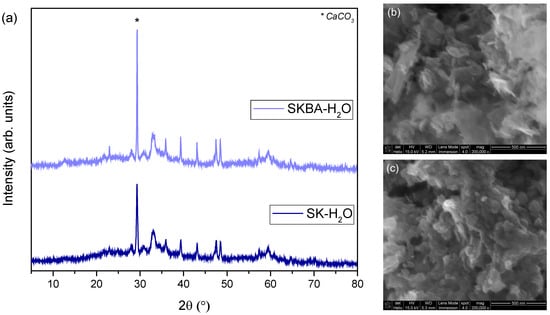

The effect of brown algae incorporation on the structural properties of the coatings was investigated by X-ray diffraction, the results of which are shown in Figure 2. As shown, both samples exhibited the characteristic diffraction pattern of the Simonkolleite, according to reference card No. 07-0155. However, noticeable differences were observed in the peak broadening of the SKBA sample compared to the reference. Crystallite size calculations based on the Scherrer equation indicated that the addition of brown algae resulted in a significant reduction in crystallite size in the (202) plane (from 48 to 31 nm), suggesting that the biofiller interfered with the crystal growth of Simonkolleite during synthesis. This decrease in the crystallite size could be associated with the presence of organic components or surface functionalities from the algae, which may act as nucleation sites or inhibit crystallite agglomeration. Furthermore, minor reflections corresponding to calcite (CaCO3), originating from the sample holder, are present in both diffractograms.

Figure 2.

X-ray diffraction patterns of the SK and SKBA coatings.

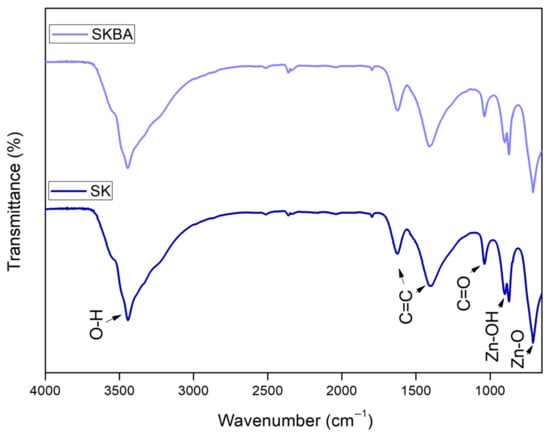

FTIR spectra of the SK and SKBA coatings are shown in Figure 3. Both spectra exhibit a broad absorption band around 3400 cm−1, attributed to O–H stretching vibrations, due to physically adsorbed water or hydroxyl groups [28]. Additional bands appear at 1630 and 1406 cm−1, corresponding to C=C stretching vibrations [29]. A small band around 1041 cm−1 is assigned to C=O stretching from organic moieties introduced by the algae or possibly to sample carbonation [30]. Furthermore, absorption bands below 1000 cm−1 in both spectra are attributed to Zn–OH and Zn–O vibrations [31] of the Simonkolleite phase. However, no significant differences were observed between the spectra.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of the SK and SKBA coatings.

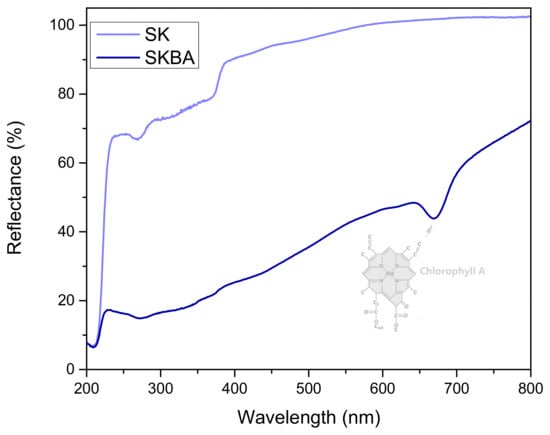

Diffuse reflectance spectra of the coatings are shown in Figure 4. The SK coating exhibits high reflectance throughout the visible region, indicating limited light absorption and a typical response for inorganic materials with low chromophoric content. In contrast, the SKBA coating presents a significantly lower reflectance, particularly in the visible region, suggesting enhanced light absorption due to the presence of brown algae. A notable absorption band occurs around 672 nm in the SKBA spectrum, which is consistent with the characteristic absorption of chlorophyll A [32], one of the main pigments found in brown algae. This evidence shows that the incorporation of photosensitive organic components may contribute to the photocatalytic or light-interacting properties of the modified coatings. The reduced reflectance of SKBA implies potential for improved solar light utilization, which could be advantageous in applications such as photocatalysis or solar coatings.

Figure 4.

Reflectance spectra of the SK and SKBA coatings.

N2 isotherms were obtained to determine the surface area of the coatings, the results of which are shown in Figure 5. Both samples exhibit Type III isotherms, which are associated with macroporous or non-porous materials [33]. In this case, sorbate molecules have a strong interaction with the surface due to the clustering of adsorbed molecules on the solid surface. The difference in the intermediate pressure range (0.2 < P/P0 < 0.8) indicates that SKBA has a less open porous structure, likely due to the partial aggregation of the organic filler. The surface area values of the samples were 28 m2/g for SK and 18 m2/g for SKBA. These results indicate that the incorporation of brown algae alters the porous architecture of the Simonkolleite coating, potentially increasing its compaction. This structural modification may be advantageous for enhancing mechanical performance and environmental durability.

Figure 5.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms of the SK and SKBA coatings.

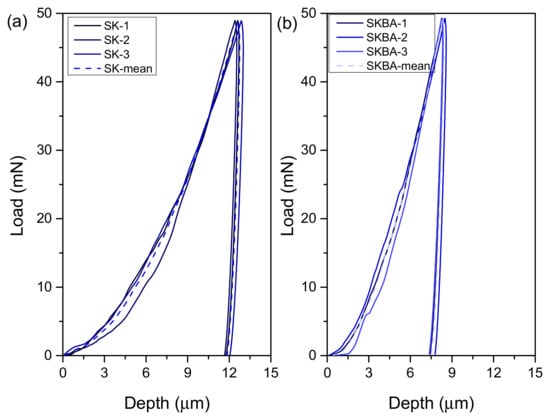

Figure 6 shows the force-depth curves obtained from nanoindentation tests on the coatings. Both samples exhibit typical loading and unloading behavior, with the SKBA coating requiring a higher force to reach the same indentation depth as the reference. These results confirm the enhanced mechanical resistance after the biofiller addition. Moreover, the SKBA sample shows a shallower maximum penetration depth under a similar applied force, suggesting increased hardness and improved elastic recovery. The mean values for the hardness of SK and SKBA were 13.5 and 32.6 MPa, respectively (Table 1). This improvement corresponds to more than a twofold increase compared to the reference coating without brown algae. Also, the Young’s modulus (EIT) increased from 1.1 to 1.7 GPa in SK and SKBA, respectively. The higher modulus in SKBA indicates improved stiffness and resistance to elastic deformation, while the increase in hardness reflects better resistance to plastic deformation. These improvements can be attributed to the influence of the biofiller on the compaction of microstructure, resulting in a denser and mechanically more stable coating. It is worth noting that “denser” in this context refers to the mechanical response, not necessarily to a reduction in global porosity visible in SEM.

Figure 6.

The load–displacement curves of the (a) SK and (b) SKBA coatings.

Table 1.

Summary of mechanical properties 1 of the SK and SKBA coatings.

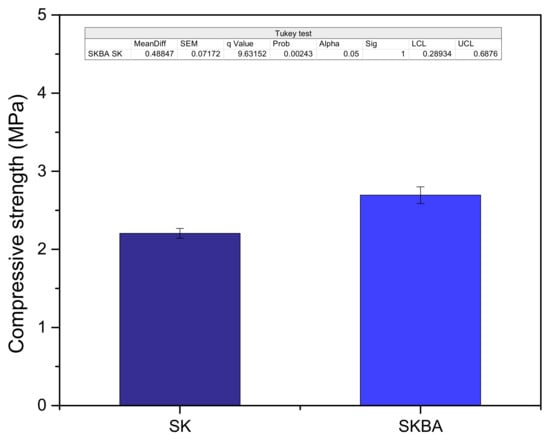

Compressive strength of a ceramic coating is an important parameter for the design of functional coatings because it determines its ability to resist different forces, ensuring durability, structural integrity, and overall performance [34]. This property was evaluated in the studied coatings, and the mean values are presented in Figure 7 and in Table 1. As shown, the SKBA coating exhibited a slightly higher compressive strength compared to the reference (2.7 vs. 2.2 MPa). Although the difference may appear modest, it was confirmed as statistically significant through a Tukey analysis (Sig = 1 and p-value < 0.05), as shown in Figure 7. These findings indicate that the incorporation of brown algae into SK coatings can enhance load distribution, which helps to hinder crack propagation and extend the service life of the coatings in demanding environments, such as urban areas with high levels of pollution. Also, it can be noted that the larger increase observed in hardness compared to compressive strength highlights the dominant role of local microstructural densification induced by the brown algae in the SK coatings.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the compressive strength values of the SK and SKBA coatings.

Mechanical Stability of the Coatings in Water

The mechanical stability of the coatings was evaluated after immersion in water for 7 d at room temperature. Afterward, hardness and compressive strength were measured to assess changes in the structural stability of the coatings.

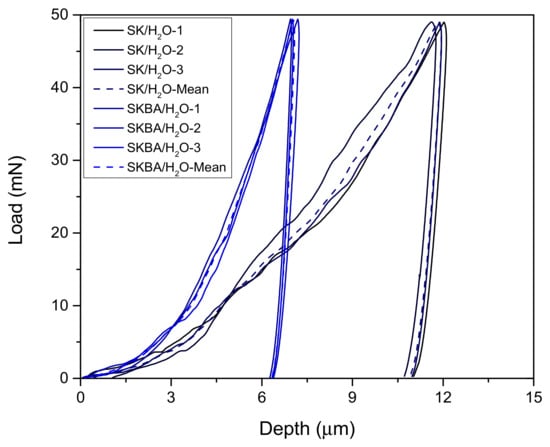

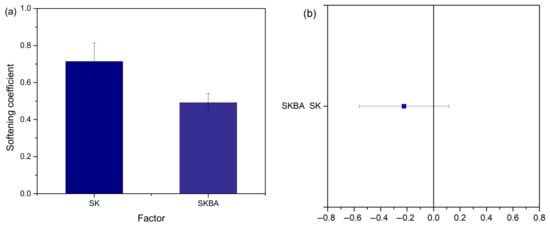

The load–displacement curves of the SK and SKBA coatings after water immersion are shown in Figure 8. Both materials retained their characteristic indentation profiles; however, a reduction in the maximum load and displacement was observed compared to the values obtained before immersion (Figure 6). This decrease suggests that prolonged exposure to water induces partial softening of the coatings, likely due to hydration or microstructural changes in the Simonkolleite phase. To quantify this effect, the softening coefficient was calculated (Figure 9a). The SK coating exhibited an average coefficient of 0.7, while SKBA showed a lower value of 0.5, indicating a higher sensitivity of the algae-modified system to water immersion. Despite this reduction, the statistical analysis using the Tukey test confirmed that the differences between SK and SKBA remained non-significant (p-value > 0.05) (Figure 9b). These results reveal that, although both coatings experience a certain loss of hardness after water immersion, the incorporation of brown algae still provides a beneficial effect in terms of structural reinforcement prior to exposure. However, the lower softening coefficient of SKBA suggests that organic fillers may increase water uptake, which in turn accelerates the weakening of the coating matrix.

Figure 8.

The load–displacement curves of the SK and SKBA coatings after being immersed 7 d in water.

Figure 9.

(a) Softening coefficient of the SK and SKBA coatings after being immersed for 7 d in water, (b) Means comparison using Tukey test (α = 0.05).

In addition, X-ray diffraction analysis was carried out to verify the stability of the crystal phase after water immersion. The diffraction patterns of both samples after the treatment confirmed that the main crystalline phase (Simonkolleite) remained, with no evidence of secondary or decomposition phases (Figure 10a). However, the crystallinity of the Simonkolleite decreased after water immersion and the signal from the sample holder (CaCO3) was more evident, particularly in the SKBA sample due to the presence of algae. In summary, these results indicate that the immersion in water did not significantly alter the crystalline structure of the coatings, and that the observed mechanical softening was mainly associated with microstructural changes (e.g., pore evolution) rather than phase transformations. Therefore, the Simonkolleite phase exhibits good chemical stability under aqueous conditions in the presence of brown algae, reinforcing its potential for applications where long-term exposure to humidity or water is expected. In addition, SEM micrographs show the characteristic lamellar morphology of SK, which confirms that the primary crystalline phase is preserved after water immersion (Figure 10b); meanwhile, SKBA exhibits densely stacked aggregates (Figure 10c). These features suggest a local refinement of the microstructure rather than the formation of interconnected porosity.

Figure 10.

Characterization of the coatings after being immersed for 7 d in water by (a) XRD and SEM for (b) SK and (c) SKBA samples.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully demonstrates that the incorporation of 5 wt.% of the brown algae Lobophora sp. as a filler into Simonkolleite coatings enhances their microstructural and mechanical properties. The algae addition acted as a structural filler, reducing the crystallite size and promoting the formation of a denser coating. This effect led to an improvement in mechanical performance, with the hardness and Young’s modulus of the modified coating more than doubling compared to the pure sample. A statistically significant increase in compressive strength was also observed, attributed to improved load distribution. Furthermore, the algae in the coatings promoted the development of functional properties, such as enhanced light absorption due to chlorophyll, which suggests potential for applications in photocatalysis or solar coatings. The Simonkolleite phase exhibited good chemical stability in water; however, both coatings experienced a reduction in mechanical strength after water exposure, probably to the continuous water uptake by the algae. The lower softening coefficient of the system that contains the algae was not significantly different from the reference. These results evidence that the harnessing of a plague-derived biomass (brown algae) represents a sustainable and effective strategy for reinforcing SK coatings, improving their hardness and stiffness without compromising compressive strength, while also adding light-harvesting functionality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: E.L.-H. and L.M.T.-M. Methodology: E.L.-H., E.A.M.-L., and L.I.I.-R. Software: L.I.I.-R. Validation: L.M.T.-M. Formal analysis: E.L.-H. and L.I.I.-R. Investigation: E.L.-H., L.M.T.-M. Resources: L.M.T.-M., E.L.-H., and L.I.I.-R. Data curation: E.A.M.-L., E.L.-H. Writing—original draft preparation: E.L.-H. and L.I.I.-R. Writing—review and editing: L.M.T.-M. Visualization: E.L.-H. and E.A.M.-L. Supervision: L.M.T.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI) through the Project Investigadores por México 1060.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Miguel Esneider and Victor Luna (CIMAV) for their support with compressive strengths measurements. Also, to Luis A. de la Fuente Rodríguez (UANL) for his help with the hardness assays.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Qu, S.; Hadjittofis, E.; Malaret, F.; Hallett, J.; Smith, R.; Campbell, K.S. Controlling simonkolleite crystallisation via metallic Zn oxidation in a betaine hydrochloride solution. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 2437–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sithole, J.; Ngom, B.D.; Khamlich, S.; Manikanadan, E.; Manyala, N.; Saboungi, M.L.; Knoessen, D.; Nemutudi, R.; Maaza, M. Simonkolleite nano-platelets: Synthesis and temperature effect on hydrogen gas sensing properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 7839–7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamlich, S.; Mokrani, T.; Dhlamini, M.S.; Mothudi, B.M.; Maaza, M. Microwave-assisted synthesis of simonkolleite nanoplatelets on nickel foam–graphene with enhanced surface area for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 461, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.D.; Volovitch, P.; Aal, A.A.; Allely, C.; Ogle, K. The effect of an artificially synthesized simonkolleite layer on the corrosion of electrogalvanized steel. Corros. Sci. 2013, 70, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, M.I.; Ali, M.E.M.; Ghaly, M.Y.; El-Missiry, M.A. Mesoporous simonkolleite—TiO2 nanostructured composite for simultaneous photocatalytic hydrogen production and dye decontamination. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2015, 94, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.A.; Silva, M.J.B.; Rocha, A.A.; Costa, M.P.C.; Marinho, J.Z.; Dantas, N.O. Synergistic effect of simonkolleite with zinc oxide: Physico-chemical properties and cytotoxicity in breast cancer cells. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 266, 124548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Espinosa, I.; Torres-Martínez, L.M.; Luévano-Hipólito, E. Photoactive self-cleaning zinc oxychloride coatings. Results Surf. Interf. 2024, 17, 100350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; He, C.; Tian, C.; Liu, J.; Fan, X.; Lv, Y.; Cai, G. Optimisation of mechanical and tribological properties of thermally sprayed ceramic coatings: An investigation of innovative in-situ doping strategies with carbon and resin. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 707, 163621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, P.; Nagaraju, D. The effect of electroless Ni–P-coated Al2O3 on mechanical and tribological properties of scrap Al alloy MMCs. Int. J. Metalcast. 2023, 17, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Wang, M.; Lu, X. UV-curable self-healing, high hardness and transparent polyurethane acrylate coating based on dynamic bonds and modified nano-silica. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 172, 107051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoos, M.; Bose, B.; Rawal, S.; Arif, A.F.M.; Veldhuis, S.C. The influence of residual stress on the properties and performance of thick TiAlN multilayer coating during dry turning of compacted graphite iron. Wear 2020, 454–455, 203342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, H.; Liu, Q.; Hao, Z.; Xu, D.; Chen, X.; Cui, D.; Xu, L.; Feng, Y. Review of Preparation and Key Functional Properties of Micro-Arc Oxidation Coatings on Various Metal Substrates. Coatings 2025, 15, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, P.; Han, R.; Ren, J.; Li, L.; Han, N.; Xing, F.; Zhu, J. A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2019, 8, 628–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkhalaf, M.; Sarvestani, H.Y.; Yang, Q.; Jakubinek, M.B.; Ashrafi, B. A comparative study of nano-fillers to improve toughness and modulus of polymer-derived ceramics. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robakowska, M.; Gierz, Ł.; Mayer, P.; Szcześniak, K.; Marcinkowska, A.; Lewandowska, A.; Gajewski, P. Influence of the addition of sialon and aluminum nitride fillers on the photocuring process of polymer coatings. Coatings 2022, 12, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M.E. The effect of filler type (tungsten carbide, zinc oxide) and content on the mechanical and wear behavior of jute/flax reinforced epoxy hybrid composites: Experimental and artificial neural network analysis. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 8700–8719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazan, C.; Enesca, A.; Andronic, L. Synergic effect of TiO2 filler on the mechanical properties of polymer nanocomposites. Polymers 2021, 13, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiyantoro, C.; Sosiati, H.; Kamiel, B.P.; Fikri, M.L.S. The effect of CaCO3 filler component on mechanical properties of polypropylene. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 432, 012043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aredla, R.; Dasari, H.C.; Kumar, S.S.; Pati, P.R. Mechanical properties of natural fiber reinforced natural and ceramic fillers for various engineering applications. Interactions 2024, 245, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.K.; Parameswaranpillai, J.; Krishnasamy, S.; Begum, P.M.S.; Nandi, D.; Siengchin, S.; George, J.J.; Hameed, N.; Salim, N.V.; Sienkiewicz, N. A comprehensive review on cellulose, chitin, and starch as fillers in natural rubber biocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantasrirad, S.; Mayakun, J.; Numnuam, A.; Kaewtatip, K. Effect of filler and sonication time on the performance of brown alga (Sargassum plagiophyllum) filled cassava starch biocomposites. Algal Res. 2021, 56, 102321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulatier, M.; Duchaudé, Y.; Lanoir, R.; Thesnor, V.; Sylvestre, M.; Cebrián-Torrejón, G.; Vega-Rúa, A. Invasive brown algae (Sargassum spp.) as a potential source of biocontrol against Aedes aegypti. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Pinto, C.A.; Cruz, J.C.; Escobar, B.; García-Uitz, K.; Nahuat-Sansores, J.R.; Alvarez, T.; Gurrola, M.P. Development of Sargassum spp. ash as filler material on cement composites with low carbon dioxide production. Mag. Concr. Res. 2025, 77, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Díaz, F.; Martínez Arreguin, A.; Hernández, J.C.; Juárez-Alvarado, C.A.; Galindo-Rodríguez, S.A.; García-Hernández, D.G. Compatibility study of sargassum-based aggregate in Portland cement-based cementitious matrix. J. Constr. 2025, 24, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyra, G.P.; Colombo, A.L.; Duran, A.J.F.P.; Parente, I.M.S.; Bueno, C.; Rossignolo, J.A. The use of Sargassum spp. ashes as a raw material for mortar production: Composite performance and environmental outlook. Materials 2024, 17, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauta, J.; Vaca-Medina, G.; Raynaud, C.D.; Simon, V.; Vandenbossche, V.; Rouilly, A. Development of a binderless particleboard from brown seaweed Sargassum spp. Materials 2024, 17, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugappan, V.; Muthadhi, A. Studies on the influence of alginate as a natural polymer in mechanical and long-lasting properties of concrete—A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 65, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado-Lira, E.A.; Luévano-Hipólito, E.; Torres-Martínez, L.M. Brown algae: Sargassum sp. and Lobophora sp. incorporation in magnesium oxychloride cement. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 44, 101969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sosa, L.B.; Alvarado-Flores, J.J.; Corral-Huacuz, J.C.; Aguilera-Mandujano, A.; Rodríguez-Martínez, R.E.; Guevara-Martínez, S.J.; Alcaraz-Vera, J.V.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G.; Zárate-Medina, J.; Ávalos-Rodríguez, M.L.; et al. A prospective study of the exploitation of pelagic Sargassum spp. as a solid biofuel energy source. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalakshmi, S.; Hema, N.; Vijaya, P.P. In vitro biocompatibility and antimicrobial activities of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) prepared by chemical and green synthetic route—A comparative study. BioNanoScience 2020, 10, 112–121. [Google Scholar]

- Balogun, S.W.; James, O.O.; Sanusi, Y.K.; Olayinka, O.H. Green synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles using bashful (Mimosa pudica) leaf extract: A precursor for organic electronics applications. Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, R.J.; Sma-Air, S. Using integrating sphere spectrophotometry in unicellular algal research. J. Appl. Phycol. 2020, 32, 2947–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, P.-X.; Xu, J.-J.; Li, H.-Y.; Luo, J.-P.; Shi, Q. Sorption mechanism, hygroscopic agents, and application of passive water evaporative cooling technology—A review. Chem. Thermodyn. Therm. Anal. 2025, 18, 100166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, D.; Fan, Z.; Ma, J.; Liang, C.; Chen, X. Comparative study on compressive strength of coated particles prepared in a Wurster fluidized bed using different coating materials. Powder Technol. 2025, 457, 120928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.