Effect of SRB on the Electrochemical Performance of Aluminum-Based Sacrificial Anodes in Marine Mud

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cultivation of Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria

2.3. Experimental Medium

2.4. Cathodic Protection Experiment

2.5. Surface Morphology and Compositional Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Macroscopic Corrosion Morphology of Sacrificial Anodes

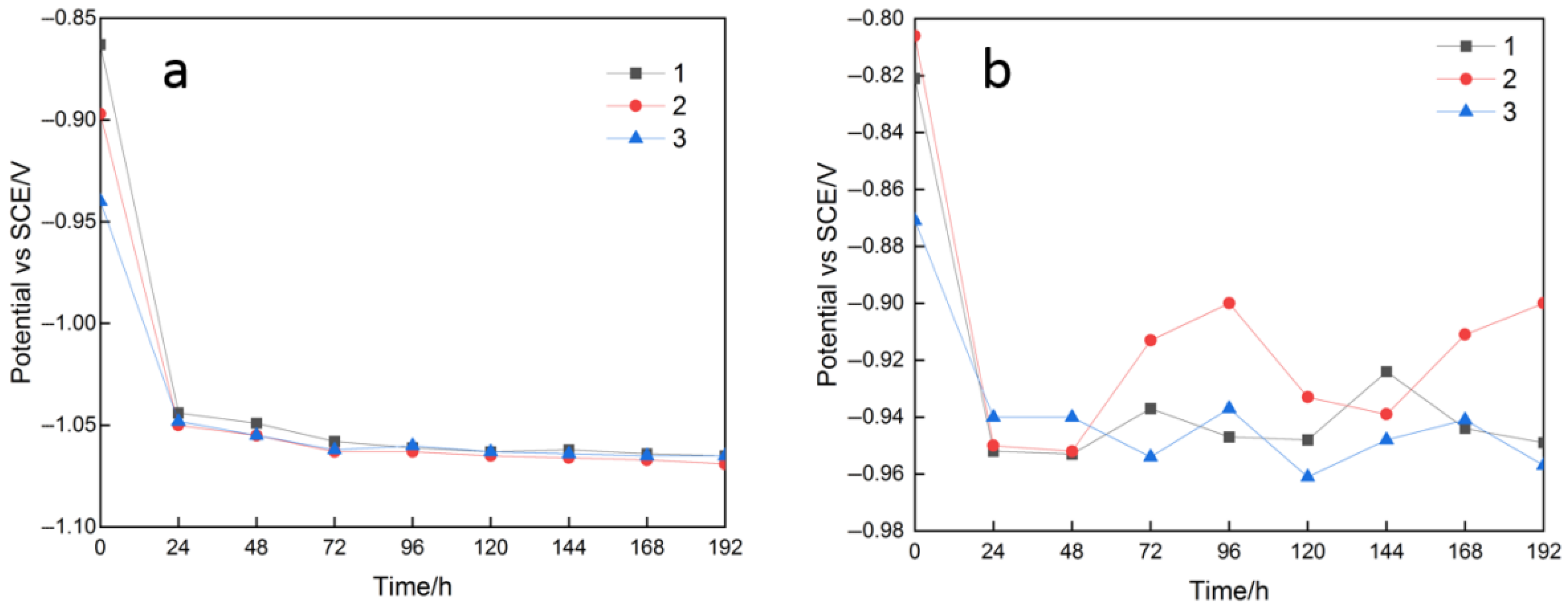

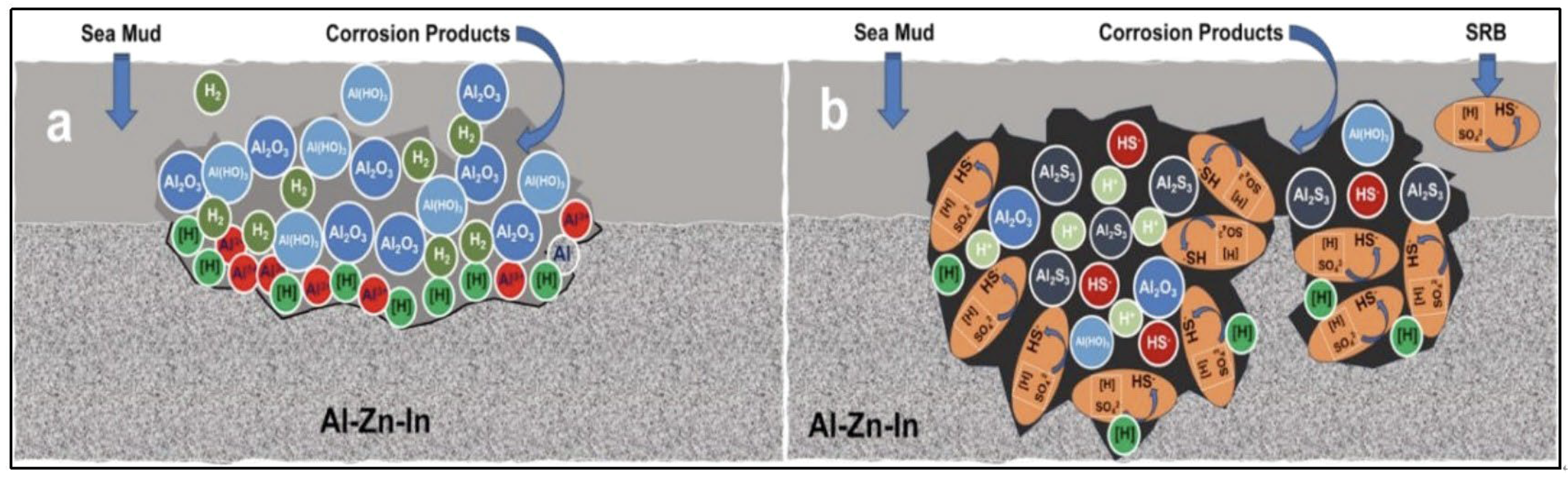

3.2. Sacrificial Anode Electrochemical Performance

3.3. Analysis of the Micro-Area Corrosion Morphology and Composition of Sacrificial Anodes

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grantz, W.C. Steel-shell immersed tunnels—Forty years of experience. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 1997, 12, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F. Research and Analysis on Key Technology of Immersed Tunnel Engineering. Master’s Thesis, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.; Chen, W.; Jin, W.; Liu, J. Shenzhong Channel Immersed Tunnel—The World’s First Large-Scale Immersed Tunnel Using Steel Shell-Concrete Composite Structure. Tunn. Rail Transit. 2020, 4, 64. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=7104169081#ByCouplingRelate (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Wang, C.L. Corrosion Behavior of Galvanic Corrosion in Multi-Material System in Marine Environment. Ph.D. Thesis, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.; Xu, L.; Fang, H. Anaerobic electrochemical corrosion of mild steel in the presence of extracellular polymeric substances produced by a culture enriched in sulfate-reducing bacteria. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 1720–1727. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/es011187c (accessed on 10 October 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.Z.; Wu, S.R.; Zhang, X.J.; Huang, G.Q.; Du, M.; Hou, B.R. Corrosion of carbon steel influenced by anaerobic biofilm in natural seawater. Electrochim. Acta 2008, 54, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, S.; Odagiri, M.; Ito, T.; Satoh, H. Succession of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria in the microbial community on corroding concrete in sewer systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashassi-Sorkhabi, H.; Moradi-Haghighi, M.; Zarrini, G. The effect of Pseudoxanthomonas sp. as manganese oxidizing bacterium on the corrosion behavior of carbon steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2012, 32, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, T.H.; Yoza, B.A.; Wang, L.; Masutani, S.M.; Li, Q.X. Biodegradation of biodiesel and microbiologically induced corrosion of 1018 steel by Moniliella wahieum Y12. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2016, 108, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Han, E.H.; Wang, Z. Effect of tannic acid on corrosion behavior of carbon steel in NaCl solution. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhan-Sungur, E.; Cansever, N.; Cotuk, A. Microbial corrosion of galvanized steel by a freshwater strain of sulphate reducing bacteria (Desulfovibrio sp.). Corros. Sci. 2007, 49, 1097–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starosvetsky, D. Effect of iron exposure in SRB media on pitting initiation. Corros. Sci. 2000, 42, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda, H.; Benetton, X.D. SRB-biofilm influence in active corrosion sites formed at the steel-electrolyte interface when exposed to artificial seawater conditions. Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 1169–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, T.S.; Kora, A.J.; Anupkumar, B.; Narasimhan, S.V.; Feser, R. Pitting corrosion of titanium by a freshwater strain of sulphate reducing bacteria (Desulfovibrio vulgaris). Corros. Sci. 2005, 47, 1071–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Han, E.H.; Wang, X. Effects of SRB on Corrosion of Carbon Steel in Seamud. Corros. Sci. Prot. Technol. 2003, 15, 104–106. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=7714900&from=Qikan_Search_Index (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Xu, L.K.; Ma, L.; Xing, S.H.; Cheng, H. Review on Cathodic Protection for Marine Structures. Mater. China 2014, 33, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, F.; Duan, J.; Zhai, X.; Wang, N.; Zhang, J.; Lu, D.; Hou, B. Interaction between sulfate-reducing bacteria and aluminum alloys—Corrosion mechanisms of 5052 and Al-Zn-In-Cd aluminum alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 36, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.S.; Wang, Z.Y.; Qiu, Y.B.; Iftikhar, T.; Liu, H.F. “Electrons-siphoning” of sulfate reducing bacteria biofilm induced sharp depletion of Al-Zn-In-Mg-Si sacrificial anode in the galvanic corrosion coupled with carbon steel. Corros. Sci. 2023, 216, 111103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.X.; Wang, T.G.; Xu, P.; Feng, Z.Y. Sulfate Reducing Bacteria Corrosion of a 90/10 Cu-Ni Alloy Coupled to an Al Sacrificial Anode. Bioelectrochemistry 2025, 163, 108892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Guan, F.; Zhan, T.; Fan, K.; Sang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhai, X.; Duan, J. The Corrosion Mechanism of Q355Steel Electrically Connected to the Al-Zn-ln-Cd Sacrificial Anode: From Microbial Community to Corrosion Behavior Analysis. Bioelectrochemistry 2025, 165, 108990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Peng, J.; Zhang, X.; Wu, K. Electrochemical performance of Al-Zn-In-Si sacrificial anode in simulated seawater and sea mud environments. Surf. Technol. 2021, 50, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X. Effect of Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria on Electrochemical Performance of Aluminum-Based Sacrificial Anode in Marine Mud Environment; Sun Yat-sen University: Guangzhou, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.X.; Wu, M.L.; Li, H.; Zhang, W. Study on the Electrochemical Performance of Al-Zn-In-Si Sacrificial Anode in Sea Mud Environment with/without Sulfate Reducing Bacteria. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2024, 14, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNE-EN 12496; Galvanic Anodes for Cathodic Protection in Seawater and Saline Mud. Comite Europeen de Normalisation: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- NACE TM0190; Impressed Current Laboratory Testing of Aluminium Alloy Anodes. National Association of Corrosion Engineers: Houston, TX, USA, 2006.

- ASTM G97; Standard Test Method for Laboratory Evaluation of Magnesium Sacrificial Anode Test Specimens for Underground Applications. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1997.

- Liu, F.G.; Zhang, W. Design and Performance Study of New Sacrificial Anodes for Marine Engineering (IV)—Application Research on Cathodic Protection of Jacket Platforms. Equip. Environ. Eng. 2018, 15, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.L.; Zhang, J.; Sun, C.X.; Yu, Z.H.; Hou, B.R. The Corrosion of Two Aluminium Sacrificial Anode Alloys in SRB-Containing Sea Mud. Corros. Sci. 2014, 83, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DNVGL RP B401; Cathodic Protection Design. DNV. GL.: Høvik, Norway; Hamburg, Germany, 2017.

- GB/T 4948; Aluminum-Zinc-Indium Alloy Sacrificial Anode. General Administration of Quality Supervision: Beijing, China, 2002.

- Yao, C.Q.; Wang, X.R.; Zhang, W.; Xia, W.T.; Chen, Z.W.; Han, B. Formation of calcareous deposits in the tidal zone and its effect on cathodic protection. npj Mater. Degrad. 2023, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 3274; Hot-Rolled Steel Plates and Strips for Carbon Structural Steels and Low-Alloy Structural Steels. General Administration of Quality Supervision: Beijing, China, 2017.

- ASTM D1141-98; Standard Practice for the Preparation of Substitute Ocean Water. American Society for TPSTesting and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- Liu, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.H.; Duan, J.Z.; Hou, B.R. Effect of sulphate reducing bacteria on corrosion of Al-Zn-In-Sn sacrificial anodes in marine sediment. Mater. Corros. 2012, 63, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, F.; Zhai, X.; Duan, J.; Zhang, M.; Hou, B. Influence of Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria on the Corrosion Behavior of High Strength Steel EQ70 under Cathodic Polarization. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, X.F.; Yang, Y.J.; Chen, X.L. Discussion on corrosion environment in the sea mud area of Huibieyang in the southern Hangzhou Bay. Mar. Bull. 2010, 29, 504–508. Available online: https://www.xueshu.com/hytb/201005/10579671.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Zhu, Y.Y.; Huang, Y.L.; Huang, S.D. Hydrogen permeation of 16Mn steel in sea mud with sulfate reducing bacteria. Corros. Sci. Prot. Technol. 2008, 20, 118–120. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, F.L.; Li, W.H.; Duan, J.Z.; Hou, B.R. Effect of sulfate-reducing bacteria in sea mud on corrosion of Zn-Al-Cd sacrificial anode. Acta Metall. Sin. 2010, 46, 1250–1257. Available online: https://www.ams.org.cn/CN/10.3724/SP.J.1037.2010.00201 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Reboul, M.C.; Gimenez, P.; Ramenuj, J. A proposed activation mechanism for aluminum anodes. Corrosion 1984, 40, 366–371. Available online: https://www.x-mol.com/paperRedirect/1372174186722050048 (accessed on 10 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.Y.; Li, Y.B. Activation behavior of aluminum sacrificial anodes in sea water. J. Chin. Soc. Corros. Prot. 2008, 28, 186–192. Available online: https://www.jcscp.org/EN/Y2008/V28/I3/186 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Xu, K.; Liu, X.; Guan, K.; Yu, Y.; Lei, W.; Zhang, S.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, H. Research progress in aluminum alloy sacrificial anode materials. Equip. Environ. Eng. 2018, 15, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.X. Handbook of Cathodic Protection Engineering; Chemical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kushkevych, I.; Dordević, D.; Vítězová, M. Analysis of pH dose-dependent growth of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Open Med. 2019, 14, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, O.J.; Chen, J.M.; Huang, L.; Buglass, R.L. Sulfate-reducing bacteria. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1996, 26, 155–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Tan, J.L.; Jin, P.; Blackwood, D.J.; Xu, D.K.; Gu, T.Y. Effects of biogenic H2S on the microbiologically influenced corrosion of C1018 carbon steel by sulfate reducing Desulfovibrio vulgaris biofilm. Corros. Sci. 2018, 130, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Huangfu, W.Z.; Liu, Z.Y.; Du, C.W.; Liu, X.G.; Song, D.D.; Cao, B. Influence of sea mud state on the anodic behavior of Al-Zn-In-Mg-Ti sacrificial anode. Ocean Eng. 2017, 136, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Composition | Mass Fraction (%) | Standard Mass Fraction (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Al | 94.5000 | 92.555~94.115 |

| Zn | 5.3100 | 5.500~7.000 |

| In | 0.0265 | 0.025~0.035 |

| Si | 0.0872 | <0.100 |

| Fe | 0.0467 | <0.150 |

| Ca | 0.0107 | <0.100 |

| Other | 0.0189 | <1.500 |

| Chemical Composition | Mass Fraction (%) |

|---|---|

| Fe | >99.9 |

| C | <0.010 |

| Si | <0.010 |

| Mn | <0.010 |

| S | <0.001 |

| P | <0.001 |

| Name | CAS | Brand | Purity | Concentration (g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl | 7647-14-5 | Macklin | AR | 24.53 |

| MgCl2 | 7786-30-3 | HUSHI | AR | 5.20 |

| Na2SO4 | 7757-82-6 | HUSHI | AR | 4.09 |

| CaCl2 | 10043-52-4 | Macklin | AR > 96% | 1.16 |

| KCl | 7447-40-7 | Macklin | AR | 0.695 |

| NaHCO3 | 144-55-8 | Macklin | 99.99% metal basis | 0.201 |

| KBr | 7758-02-3 | Macklin | 99.9% metal basis | 0.101 |

| H3BO3 | 10043-35-3 | HUSHI | AR | 0.027 |

| SrCl2 | 10025-70-4 | Aladdin | ACS | 0.025 |

| NaF | 7681-49-4 | Macklin | PT | 0.003 |

| Material | CAS | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| K2HPO4 | 7758-11-4 | 0.5 g/L |

| NH4Cl | 12125-02-9 | 1.0 g/L |

| CaCl2 | 10043-52-4 | 0.06 g/L |

| (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 | 10045-89-3 | 0.2 g/L |

| Yeast extract | 8013-01-2 | 1.0 g/L |

| MgSO4·7H2O | 10034-99-8 | 0.06 g/L |

| Sodium citrate | 68-04-2 | 0.3 g/L |

| Sodium lactate | 312-85-6 | 6 mL/L |

| Ascorbic acid | 50-81-7 | 0.1 g/L |

| Size (Mesh/Inch) | Aperture Size (mm) | Mass Fraction (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 3.860 | 6.48 |

| 20 | 0.900 | 60.44 |

| 80 | 0.200 | 26.67 |

| 400 | 0.038 | 6.13 |

| >400 | <0.038 | 0.28 |

| Number | Environment | pH |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aseptic sea mud environment | 6~7 |

| sea mud environment with SRB | 3~4 | |

| 2 | Aseptic sea mud environment | 6~7 |

| sea mud environment with SRB | ≈3 | |

| 3 | Aseptic sea mud environment | ≈6 |

| sea mud environment with SRB | 3~4 |

| Environment | Number | Electrochemical Capacity/(A·h·kg) | Electrochemical Efficiency/% | Work Potential (vs.SCE)/V | Open Circuit Potential (vs.SCE)/V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sea mud without SRB | 1 | 2065.30 | 72.25 | −1.034 | −1.041 |

| 2 | 1997.37 | 69.87 | −1.054 | −1.061 | |

| 3 | 1855.84 | 64.92 | −1.051 | −1.052 | |

| σ | 87.25 | 3.05 | 0.009 | 0.009 | |

| Sea mud without SRB | 1 | 1299.45 | 45.46 | −0.970 | −1.086 |

| 2 | 1335.31 | 46.71 | −0.933 | −1.086 | |

| 3 | 1209.08 | 42.30 | −0.951 | −1.089 | |

| σ | 65.05 | 2.27 | 0.015 | 0.0014 |

| Region | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | Average Value | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | Average Value | S5 | S6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 67.2 | 67.8 | 67.6 | 54.8 | 64.4 | 94.8 | 90.5 | 89.9 | 93.9 | 92.3 | 70.7 | 84.5 |

| Zn | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 4.8 | 3.8 | 1.7 | 3.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Quan, W.; Huang, H.; Lin, Z. Effect of SRB on the Electrochemical Performance of Aluminum-Based Sacrificial Anodes in Marine Mud. Coatings 2026, 16, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010026

Zhou B, Zhang W, Zhang X, Quan W, Huang H, Lin Z. Effect of SRB on the Electrochemical Performance of Aluminum-Based Sacrificial Anodes in Marine Mud. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Baocheng, Wei Zhang, Xinwen Zhang, Weiyin Quan, Hua Huang, and Zhifeng Lin. 2026. "Effect of SRB on the Electrochemical Performance of Aluminum-Based Sacrificial Anodes in Marine Mud" Coatings 16, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010026

APA StyleZhou, B., Zhang, W., Zhang, X., Quan, W., Huang, H., & Lin, Z. (2026). Effect of SRB on the Electrochemical Performance of Aluminum-Based Sacrificial Anodes in Marine Mud. Coatings, 16(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010026