Abstract

Glazed tiles are a common component of ancient buildings, typically used for roofs and walls, serving decorative, protective, and waterproofing purposes. Currently, they are severely damaged and urgently require protection. This study investigated the preservation and damage status of glazed tile components in ancient buildings throughout Shanxi Province. Temperature and humidity variations and acid rain corrosion simulation experiments were conducted to investigate the causes of glazed tile damage. By characterizing morphological changes and corrosion products, the damage process of glazed tiles under the influence of external temperature, moisture, and acid rain was explained. For damage phenomena such as powdering of the tile body, hydroxyl-terminated PDMS–OH/TEOS was selected as the coating materials, and ethanol was used as the solvent to reinforce the glazed tile body. By characterizing indicators such as color difference, water resistance, and mechanical properties, a suitable coating materials formulation was selected. The reinforcement mechanism was investigated using infrared spectroscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, and scanning electron microscopy. For glazed tiles with extremely severe damage, new glazed tiles with superior mechanical properties were fired by reducing the particle size of the raw material in the tile body to replace them.

1. Introduction

Glazed tiles, commonly known as lead-glazed products, are made using lead compounds as a flux and can be fired at temperatures between 800 °C and 900 °C. Architectural glazed tiles are a type of low-temperature lead glaze, with compositions similar to traditional low-temperature colored glazes like the Tang Sancai (three-colored pottery) [1].

A defining feature of lead-glazed products is their low melting point. During the Qing Dynasty, glazed components typically had a lead oxide content of over 50%, with the glaze melting between 750 °C and 950 °C under these conditions. The primary raw material for glazed tiles is coal gangue, with SiO2 content ranging from 37% to 68%, and Al2O3 content varying between 11% and 36%. To achieve sufficient sintering, the body is typically fired at temperatures exceeding 1000 °C [2,3,4]. The body’s high firing temperature and the glaze’s low melting point necessitate a two-stage firing process in the kiln. In the first stage, the body is fired above 1000 °C to achieve sintering. The second stage involves firing the glaze below 950 °C, where it melts and bonds with the body.

Glazed tiles were widely used in the construction of royal buildings throughout ancient China, predominantly in the northern part, such as palaces, temples, and other significant structures [5,6]. There are strict regulations governing the colours of glazed tiles, with common ones being yellow, green, blue, black, and purple. Yellow is the highest-grade color, reserved exclusively for the imperial palaces and tombs, such as the Forbidden City and the Ming Tombs in Beijing. Green and blue tiles were used in royal mansions or by senior officials (only by imperial decree), while purple and black were primarily used in royal gardens for pavilions and buildings.

As archaeological research has advanced, systematic studies of glazed tiles have become more prevalent. For instance, the process of firing yellow glazed tiles has been studied using modern analytical techniques; microscopic analysis has been conducted to examine the lead-to-tin ratio in yellow glazed tiles. Scholars have also conducted extensive studies on the laboratory preservation of glazed tiles, utilizing techniques like SEM and XRD to analyze the manufacturing processes of various colored tiles [7]. Green, yellow, and brown glazes are typical high-lead formulas, in line with ancient Chinese manufacturing recipes. High-lead ceramic building materials, along with the challenges they face are not exclusive to China. To take one example, scientific analysis of 19th-century high-lead ceramic tiles from Hungary revealed similar types of deterioration, such as surface deposits and acid salt corrosion, due to common material elements [8]. In addition, research on glazed tiles has also been carried out in regions like Northwestern Iran, Southeast Anatolia, Belgium, and Iznik Turkey, focusing on chemical composition and firing techniques from various historical periods.

Historically, materials such as Primal SF, Paraloid B72, and acrylates were widely used, as well as composite materials like Remmers 300. Additionally, hydrophobic nanomaterials like tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) and hydroxyl-terminated polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [9], combined with nonionic surfactants, have been applied to stone restoration Several types of modified ethyl silicate consolidants, organosilane consolidants, and copolymers of fluorinated acrylates, methacrylates, and vinyl ethers, as well as polyhydroxybutyrate and poly-L-lactide, have been used to create protective coatings for building surfaces. Moreover, new materials are also chosen by many conservators. To take one example, silicon-based materials containing fluorine (SIC-1 and SIC-2) and hydrophobic organic silicon resins (SIC-3) have been chosen to address glaze shedding and damage to glazed tiles in ancient buildings. However, these materials may degrade over time on the surface of glazed tiles, and if not cleaned promptly, can worsen the damage.

Tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) is one of the most widely used inorganic consolidants in stone and ceramic conservation and has been extensively applied in international heritage preservation for more than three decades. As a typical silicate precursor in sol–gel chemistry, TEOS undergoes hydrolysis and condensation in the presence of water and acidic catalysts, gradually forming a three-dimensional SiO2 gel network. This gel network is capable of penetrating the pore system of stone, ceramic, and glazed architectural materials, where it subsequently polymerizes in situ and bonds to the original silica-rich matrix through the formation of Si–O–Si linkages. Such chemical bonding enables TEOS to restore structural cohesion, improve mechanical integrity, and reduce microcrack propagation without significantly altering the substrate’s visual appearance. Numerous studies have demonstrated that TEOS exhibits good compatibility with quartz-based or silicate-based substrates, moderate permeability, and relatively low shrinkage during gelation, which make it suitable for calcareous stone, terracotta, and traditional architectural glazed components. However, pure TEOS consolidants also present certain limitations, including limited flexibility, susceptibility to cracking during aging, and modest hydrophobicity, which may compromise long-term durability under complex outdoor environments. Therefore, recent conservation research has focused on hybrid TEOS systems—such as those modified with PDMS–OH or organosilane copolymers—to enhance water repellency, improve elasticity, and reduce color alteration while maintaining consolidation performance. In this context, the TEOS/PDMS–OH hybrid coating system explored in this study represents a scientifically grounded evolution of conventional TEOS consolidants, offering improved physicochemical compatibility and better suitability for the protection of porous and environmentally stressed glazed architectural heritage. TEOS forms a silica network providing consolidation, while PDMS–OH improves hydrophobicity, reduces color alteration, enhances flexibility, and mitigates cracking during aging.

While experimental studies have been conducted, research on the specific forms of damage to glazed tiles in outdoor environments still remains insufficient [10,11,12]. This study will include a large-scale field survey in Shanxi, systematically identifying different types of damage to glazed tiles. The research will focus on real-world damage to glazed components, using visual observation and anthropological methods to analyze local use patterns, and provide a detailed discussion of the types of damage to these tiles.

2. Research Locations

Shanxi Province is one of the key regions in China known for its use of colored glaze in architecture. This is largely due to Shanxi’s abundant coal resources, as well as the presence of “ganzi soil,” found alongside the coal, which is essential for firing colored glaze. Notable examples of colored glaze architecture in Shanxi include the colored glaze complex in Jiexiu and the ancient city of Datong, both of which are renowned architectural sites. These ancient buildings, with their high construction standards, predominantly featured roofs made of colored glazed tiles. Additionally, many buildings included colored glaze screen walls and memorial arches, crafted from colored glaze components [13].

This study primarily examines the deterioration of colored glaze components in ancient buildings across Taiyuan, Jincheng, Datong, Jiexiu, Yangcheng, and other locations in Shanxi Province, encompassing the entire region. The detailed research locations are pointed in the following figure (Figure 1). All surveyed buildings are classified as National Key Protection Units, as shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Map of Research Locations in Shanxi.

Table 1.

Overview of Glazed Tile Components in Architectural Research.

3. Methods

As the surveyed colored glaze components are immovable cultural relics, in situ detection is necessary. In line with cultural heritage preservation principles, non-destructive testing methods are prioritized in this investigation. The on-site assessment of the colored glaze’s condition followed the GB/T 3810 standard [14] for domestic ceramic tiles. A scientific evaluation was performed to analyze surface defects, deterioration, as well as the hardness, gloss, and color variation in the colored glaze [15].

- (1)

- The colorful glaze was examined with a Dino-Lite AM3111 handheld microscope. With a magnification of tens to hundreds of times, this equipment is perfect for on-site inspection and enables close examination of glazing fractures and other deterioration events.

- (2)

- An environmental scanning electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific Quattro S) fitted with a Bruker QUANTAX EDS X-ray energy dispersive spectrometer was used to examine the materials’ microstructure and chemical makeup. The working distance was roughly 10 mm, the low vacuum was 50 Pa, and the accelerating voltage was set between 15 and 20 kV. The CBS backscattered electron mode was used to capture the images. After being immersed in epoxy resin, the cross-sectional sample was polished and ground.

- (3)

- A Renesas Vavia laser micro-focusing Raman spectrometer was used to examine the materials’ physical phase composition. A research-grade Leica microscope with a spatial resolution of less than 0.5 μm is attached to this device. An excitation wavelength of 532 nm, a laser power of 280 mW, a laser power density of 1.0%, a scan period of 10 s, and ten scans in total were the experimental parameters.

- (4)

- A Leeb hardness tester was used to gauge the hardness of the exposed body and the pigmented glaze. Despite the colored glaze’s relative hardness, caution must be used during the test to prevent additional damage. The test must be continuously monitored, and if damage is found, it must be halted right away.

- (5)

- A gloss meter was used to gauge the colored glaze’s gloss. A smaller measurement aperture is advised since some colored glazes may have curved surfaces. Additionally, a test angle of 60° is typically adequate because different gloss levels can result in some regions having good shine and others having absolutely no sheen at all [16].

A colorimeter was used to assess the color of the tinted glaze. The measurement was performed using the Lab value, which was developed by the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) based on human color perception. The representative value was determined by averaging the values of several test points. Within the same structure, components of various colors and positions were subjected to color difference testing. A certain degree of color change is acceptable; however, significant differences indicate discoloration caused by lesions.

4. On-Site Damage to the Glazed Tile Enamel

The deterioration of colored glaze can be classified into two categories: one arises from the production process, while the other is due to uncontrollable factors during usage, which both can significantly affect the integrity of colored glaze components [17].

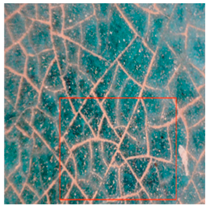

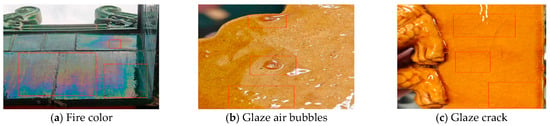

4.1. Inferior Glass Glaze Due to Production Process

A common production-related issue is “fire color,” which appears on the surface of colored glaze components during firing. This issue arises when excessive pressure inside the kiln forces flames towards lower-pressure areas [18], creating a fire flow that impacts the glaze surface and causes the formation of fire color in Figure 2a. During the firing process, the oxides in the clay body and thick glaze layer release gas at high temperatures, forming bubbles on the glaze surface. If the heat retention time is insufficient, the glaze will not have enough time to melt and smooth out, leading to the formation of “bubble pits” (Figure 2b). Glaze Cracking (Figure 2c) is another common issue in all colored glaze components. When fired, the glaze reaches a boiling state, and the glaze stone becomes liquefied. As the temperature decreases, the glaze’s thermal expansion coefficient exceeds that of the body, preventing the glaze from adhering properly and resulting in surface cracks, which creates a potential vulnerability for further deterioration during the components’ subsequent use [19].

Figure 2.

Deterioration of glass tiles due to the production process.

4.2. The Glass Glaze Used Naturally Is of Inferior Quality

The most common colored glaze components are glazed tiles, which are used on building roofs to protect the structure from rainwater damage [20,21]. However, when placed on roofs, vegetation can easily damage the colored glaze components (Table 2).

Table 2.

Vegetation-Related Deterioration.

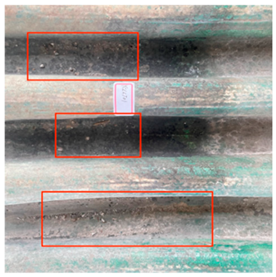

When colored glaze components are left outdoors for extended periods without cleaning, dust tends to accumulate in surface depressions, bonding tightly with the glaze (Table 3). Later, extreme weather conditions such as storms, heavy rain, or snow may wash away the accumulated dust, simultaneously causing the glaze surface to peel off.

Table 3.

Dust Accumulation Deterioration.

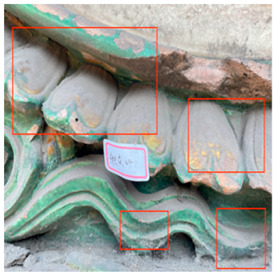

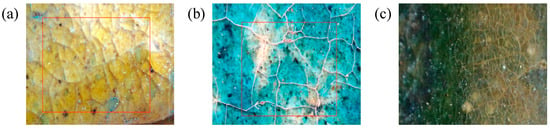

Cracking and loss of the glaze surface are common issues during the use of colored glaze components [19]. These issues often stem from crazing that occurred during production. During use, the colored glaze components expand and contract due to daily and seasonal temperature fluctuations, exacerbating the pre-existing cracks (Table 4). Observations using a handheld microscope reveal the progression and current state of these cracks, suggesting that the deterioration of the crazing-induced cracks during use is a primary cause of these issues. Additionally, salt crystals around the cracks suggest that the glaze deterioration is linked to the movement of soluble salts, driven by capillary action within the cultural relics.

Table 4.

Glaze Cracking Deterioration.

5. Analysis of the Causes of Degradation

5.1. Data and Environment

The ancient glazed tile fragments were collected from the legally approved restoration sites in Shanxi Province (Datong, Pingyao and Taiyuan). These fragments have been separated and classified by the local cultural heritage management department as restoration waste. Antique glazed tiles were purchased from traditional glazed tile workshops in Shanxi, and the clay and glaze formulas used in their production are consistent with those of the historical period. Laboratory-prepared models were only made in reduced particle size firing experiments, with the aim of systematically testing the influence of raw material fineness on mechanical strength. The environmental simulation conditions include a temperature range of: −10 °C → 25 °C → 60 °C. The heating rate: 2 °C per minute. The cooling rate: 2.5 °C per minute. The holding time for each platform: 120 min. The number of cycles: 30 times. Relative humidity (RH): 40% → 95% → 40%. Temperature: 25 °C. Change rate: 5% per minute of relative humidity. Each stage duration: 8 h. The number of cycles: 15 times. The soaking medium: deionized water (pH value 6.8–7.0). Soaking time: 72 h. Drying conditions: 40 °C, 12 h. Test cycle times: 10 times. In the initial design, a pH value of 1 was set as an accelerated corrosion condition, aiming to simulate long-term exposure to strong acid in a shorter laboratory period. According to the report of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, a realistic condition (pH value of 3.5) was added to reflect the typical acid rain situation in northern China. A sulfuric acid/nitric acid (4:1 ratio, simulating the ionic ratio of natural acid rain) solution was prepared. The actual condition’s pH value was 3.5. The pH value of the accelerated aging condition was 1. The soaking time was 48 h, followed by drying at 40 °C for 12 h. This process was repeated 5 times. This improvement enhanced the scientific completeness and environmental relevance.

5.2. The Effects of Temperature and Humidity Changes

The environmental requirements for the deterioration of glazed tiles were identified based on the examination of the climate and preservation environment of glazed tiles in Section 4 [22]. Temperature, wetness, and abrupt changes in the surroundings were among them; the experimental circumstances included abrupt shifts between high and low temperatures. These settings included 24 h of room temperature immersion followed by 8 h of low temperature immersion at −30 °C (WSLT) and 8 h at 150 °C followed by 24 h of warm water immersion (HTWS). Three parallel samples of glazed tiles measuring 2.5 cm by 3 cm by 2 cm were made for each group. Throughout the experiment, the appearance and functionality of the glazed tiles were periodically described, and any damage to the glaze and body of the glazed tiles was noted [23,24]. Sample WSLT displayed fractures and cracks in the body, as well as wider glaze cracks and small areas of glaze peeling; sample HTWS revealed no damage to the body but small areas of glaze peeling appeared at the borders. Figure 3 and Figure 4 depict the particular morphologies of samples HTWS and WSLT.

Figure 3.

The morphology of glaze peeling on the HTWS samples: (a) peeling at the edge of the yellow glaze; (b) peeling of the green glaze surface; (c) peeling of the green glaze surface.

Figure 4.

Crack morphology of WSLT samples: (a) Cracks in green glaze; (b) Cracks in yellow glaze; (c) Peeling off at the center of green glaze.

Although 150 °C does not correspond to ambient air temperature, previous conservation studies have demonstrated that the surface temperature of dark ceramic materials exposed to direct summer sunlight can exceed 120 °C due to solar radiation accumulation. Therefore, 150 °C was selected as an accelerated ageing temperature to simulate prolonged solar heating in a shorter timeframe. Likewise, the –30 °C setting reflects winter extremes recorded in high-altitude regions of northern Shanxi, where ancient architecture is located. These values thus represent accelerated but realistic boundary conditions designed to reproduce long-term seasonal stress within a condensed experimental period. Second, we clarified that 90 cycles were selected because preliminary tests showed that major deterioration phenomena—such as glaze cracking, tile-body powdering, and delamination—tended to stabilize after 80–100 cycles. Therefore, 90 cycles were adopted as a representative threshold at which degradation mechanisms became clearly observable without excessive over-aging.

Figure 3 illustrates the small patches of glaze peeling that developed on the surfaces of the HTWS sample’s green and yellow glazes after 90 testing cycles. Following glazing peeling, the exposed body has a porous structure and a high rate of water absorption. The glaze is more likely to continue peeling along the initial flaw locations because the link between the glaze and the body diminishes at the edges. Different levels of glazing and body degradation were visible in the WSLT sample [25]. Cracks damaged the link between the glaze and the body in addition to decreasing the density of the glaze surface. During the deterioration process, the tiny “ice cracks” connected to form large fissures that almost spanned the entire glaze surface, as shown in Figure 4.

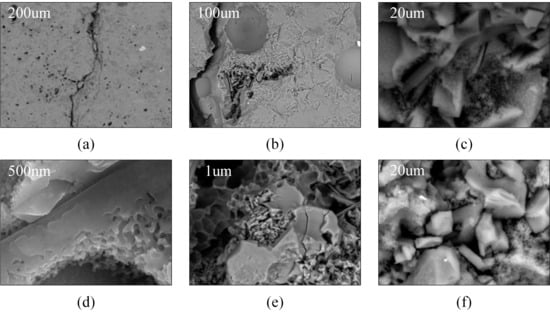

During the degradation process, microcracks initially appeared in the sample WSLT matrix. Then, as the deteriorating process progressed, the cracks’ length and width progressively expanded. As seen in Figure 5, the matrix finally broke due to a massive crack that developed throughout the whole matrix. During the deterioration process, the cracks mostly extended around the edges of big particles due to the inconsistent thermal expansion coefficients of the particles and the matrix [26]. Additionally, the pores were preferred locations for corrosion, and as the degradation process progressed, the pore area grew, creating tiny cracks along the pores’ borders. The cross-sectional particles became more porous once the matrix broke, making them more prone to break off during further deterioration. The outcomes of the experiment demonstrated that moisture played a significant role in the environmental breakdown process of glazed tiles. Glazed tiles were not significantly affected by abrupt temperature fluctuations or extremely hot or low temperatures. HTWS was primarily responsible for small-area peeling around the glaze’s margins on glazed tiles. The matrix cracked and broke, and the glaze cracks in glazed tiles widened as a result of the WSLT cycle.

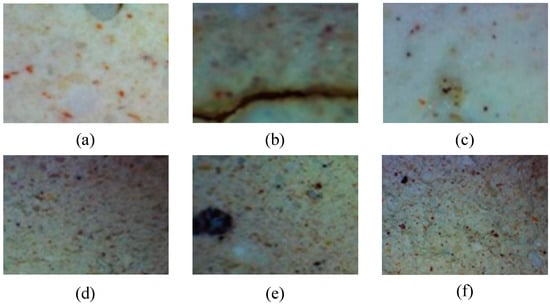

Figure 5.

Morphology of HTWS specimen carcass failure: (a–c) Morphology of cracks and large particles at cracks; (d) Morphology of cracks and pores; (e) Morphology of interwoven cracks; (f) Morphology of pores.

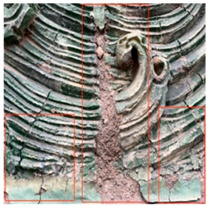

5.3. Changes in Glaze Morphology Before and After Acid Rain Corrosion

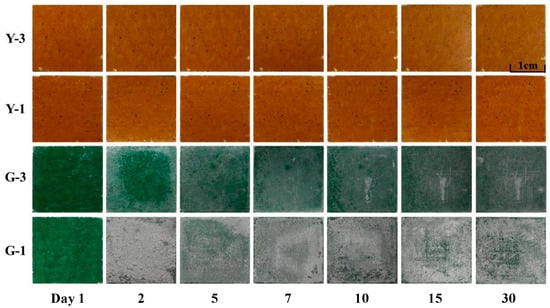

Macroscopic Morphology: Following 30 days of acid rain corrosion, Figure 6 depicts the macroscopic morphology of the glazed tile surface. Although Shanxi’s natural precipitation rarely reaches pH = 1, long-term monitoring reports indicate that local rainfall can fall to pH 3–4 in industrially influenced zones. Therefore, the pH = 1 solution was intentionally selected as an accelerated aging condition to simulate prolonged acid erosion within a shortened experimental timeframe, a method widely adopted in cultural heritage conservation research. Similarly, the extreme temperature cycling parameters were designed to replicate the significant temperature fluctuations characteristic of Shanxi’s continental climate, where seasonal temperature differences are large and freeze–thaw cycles occur frequently. Yellow and green glazed tiles showed distinct corrosion phenomena after being submerged in an acid rain solution for 30 days. The yellow glaze surface showed no discernible corrosion damage in acid rain simulations with pH values of 3 and 1. The green glazing surface’s corrosion morphology changed significantly, exhibiting distinct macroscopic morphologies in corrosion solutions with varying pH levels [27]. After one day of corrosion, white corrosion products stuck to the edges of the glaze in the pH = 3 corrosion solution. The corrosion product layer on the glazing surface became thicker and more stable after five days of corrosion. The corrosion product coating was comparatively dense and had good adherence until the 30th day of corrosion, making removal challenging. The quantity of surface corrosion products rose on the third and fifth days following removal, as seen in Figure 6. After then, during the 30-day corrosion process, the total change was negligible. Green and yellow glazed tiles exhibited different corrosion behavior under identical corrosion circumstances. While the green glaze was nearly entirely eroded, the yellow glaze had no overt indications of corrosion or damage.

Figure 6.

Changes in the macroscopic morphology of the glazed tile surface under acid rain corrosion over 30 days.

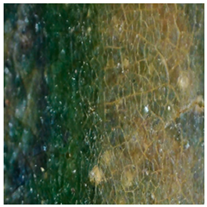

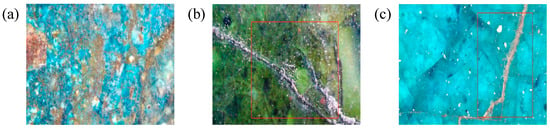

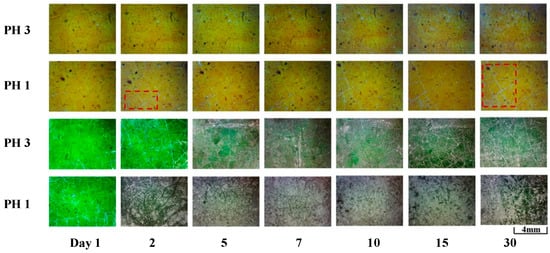

Video Microscopic Morphology: A microscope was used to examine the glaze’s morphology following corrosion in order to examine the microscopic morphology of the glazed tile surface. Figure 7 displays the outcomes. After 30 days of corrosion in a pH = 3 solution, yellow glazed tiles revealed no discernible surface alterations. A tiny quantity of white corrosion product particles were produced at the glaze’s fissures following a day of corrosion in a pH = 1 simulated corrosion solution [28]. As the corrosion period increased, the quantity of corrosion products progressively increased. Nearly all of the cracks in the field of view were enriched with corrosion product particles after 30 days of corrosion. After one day of corrosion in a pH = 3 solution, green glazed tiles had comparatively little glaze degradation. Corrosion products not only accumulated at the glaze’s fractures but also covered a significant portion of its surface. A significant amount of white, loose, granular corrosion products covered the glazing surface after one day of corrosion in a pH = 1 simulated corrosion solution. The corrosion morphology did not substantially alter after that.

Figure 7.

Changes in the glaze surface morphology of glazed tiles under acid rain corrosion over 30 days (via video microscope). Red represents the highlighted area of the glaze surface color.

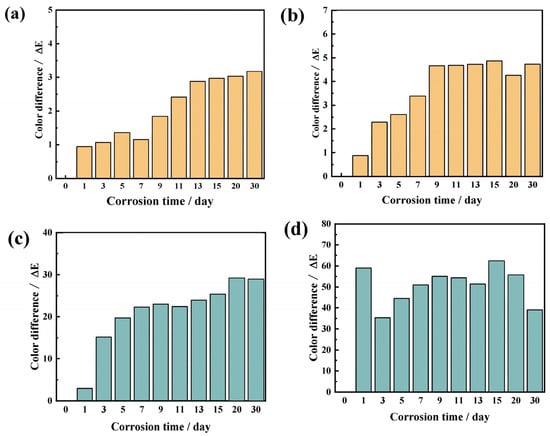

Color: The yellow and green glaze surfaces’ color difference values before and after corrosion varied considerably, which is consistent with the corrosion phenomenon (Figure 8). The yellow glaze surface’s color difference values were all within 5, with tiny values and minimal variation. This is due to the minimal quantity of corrosion products produced on the yellow glaze surface, which did not alter the glaze’s color macroscopically [29]. Green glazes typically contain Cu2+ ions, which are more susceptible to acidic attack compared with Fe3+ in yellow glazes, as acidic environments promote leaching of copper and accelerate surface degradation. In addition, green glazes often have lower firing temperatures, resulting in a less dense, more porous microstructure that increases the surface area exposed to acidic media, thereby enhancing corrosion rates. Moreover, green glazes may have lower silica content and higher lead solubility than yellow glazes, and the higher mobility of lead under acidic conditions contributes further to faster glaze dissolution. The yellow glazing surface’s color difference value progressively grew as the corrosion time increased in the pH = 3 simulated acid rain corrosion solution. Between the first and ninth days of corrosion, the glaze surface’s color difference value barely altered. The glazing surface’s color difference value increased dramatically throughout the ninth to thirty days of corrosion, reaching a very moderate discoloration level. After one day of corrosion, a significant amount of white corrosion products covered the sample surface in the acidic solution with pH = 1. As high as 60, which is regarded as serious discoloration, was the color difference value. The corrosion products on the glaze surface were removed before to immersion on the third day of corrosion in order to better observe the event. The total value was high, and the color difference value rose over time. The color difference test findings varied because the corrosion products on the glazing surface are loose and prone to falling off.

Figure 8.

Color difference in glazed tiles under acid rain corrosion over 30 days: (a) Yellow glaze, pH = 3; (b) Yellow glaze, pH = 1; (c) Green glaze, pH = 3; (d) Green glaze, pH = 1.

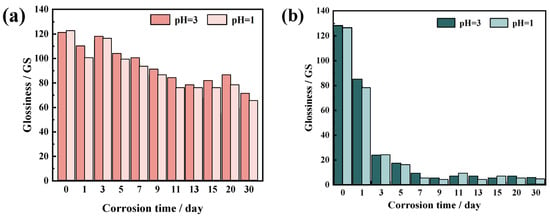

Gloss: After 30 days of corrosion in an acid rain simulation, Figure 9 illustrates how the gloss of glazed tile glazes changed. As corrosion time increased, the sheen of both green and yellow glazed tiles progressively diminished. The yellow glazed tiles’ shine decreased more in the pH = 1 corrosion solution than in the pH = 3 corrosion solution. The trend in Figure 9a shows that, beginning on day 9, the yellow glazed tiles’ decline in shine grew noticeably. The sample glazes showed significant gloss loss on day 30 of corrosion, with gloss loss rates of 46.58% (pH = 3) and 49.82% (pH = 1), respectively. Green-glazed tiles exhibited a greater reduction in shine during corrosion than yellow-glazed tiles. In the simulated acid rain corrosion solution at pH = 3, the gloss loss rate of the green glaze surface was 36.72% after one day of corrosion. The results indicate that under the same acidic corrosion conditions, the gloss loss rate of green glaze is significantly higher than that of yellow glaze.

Figure 9.

Changes in glaze gloss of glazed tiles under acid rain corrosion over 30 days: (a) yellow glaze; (b) green glaze.

6. Coating Materials of Glazed Tile Matrix by PDMS–OH/TEOS

According to field assessments, the majority of the glazed tiles found in existing old buildings have varied degrees of deterioration [10]. This study divides the locations of glazed tile damage into two categories: glaze layer and body, using temperature and humidity variations as well as acid rain corrosion simulation studies. Among these, glaze repair and glaze re-firing are the primary methods for protecting the glaze layer [29]. The protection of glazed tile bodies, specifically the materials used to safeguard existing glazed tile bodies, is the primary focus of this article. The service life of glazed tiles can be further increased by enhancing the body’s mechanical and waterproof qualities. Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) is the main coating materials. It is modified with hydroxyl-terminated polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS–OH). 10 mL TEOS was used, and PDMS–OH was added at a mass ratio of 1:4 (PDMS–OH:TEOS). PDMS–OH (Mw ≈ 5500 g/mol, OH content 0.8–1.2 wt%) supplied by the manufacturer. A 0.01 M HCl aqueous solution was used as the catalyst for TEOS hydrolysis; no surfactants were added in order to maintain material compatibility with the ceramic substrate. Ethanol is used as solvent to investigate the effects of PDMS–OH and ethanol content on the Coating effect. By comparing the water absorption rate, mechanical properties, and water resistance of the body after Coating, the formula with the best Coating effect is selected [30].

Before Coating, the glazed tiles were subjected to a simulated degradation treatment based on the simulation results in Section 5. The TEOS/PDMS–OH mixture was magnetically stirred for 30 min to obtain a homogeneous hybrid coating solution. For three hours, the sample substrate was dried in an oven set at 105 °C. It was immediately removed and submerged for three hours in a pH-3 acid rain simulation solution. Lastly, it was frozen for three hours at −18 °C. Specific masses of TEOS, PDMS–OH, and ethanol were weighed and carefully combined using an analytical balance. The glazed tile substrate sample was covered with equal amounts of coating materials. The sample was put in a fume hood to allow the coating materials to fully penetrate after making sure all surfaces were sufficiently moistened. Finally, it was placed in a 35 °C vacuum drying oven for 12 h and then left at room temperature for 3–4 days before various performance tests were conducted.

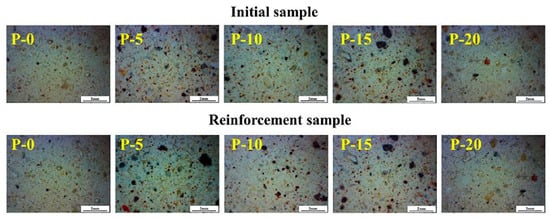

6.1. Color Difference Compatibility Analysis

The principle of consistent style should be followed in the restoration and preservation of cultural artifacts, and samples should have similar colors before and after treatment. Figure 10 displays the samples’ morphology both before and after the coating materials was applied. The samples’ appearance was barely altered by the coating materials. The penetration effect was good and the reinforcing agent did not solidify significantly on the surface. Figure 11 illustrates how the samples’ surface colors changed after being treated with the coating materials. The surface color difference value of the sample with added PDMS–OH was slightly higher than that of the sample reinforced with pure TEOS, and it gradually increased with the increase in PDMS–OH content. However, the overall change was not large and the color difference value was in the range of 1.5~3, which was a very slight discoloration degree, and it was within the acceptable color difference range compared with the original glazed tile body [31].

Figure 10.

Comparison of morphology before and after coating materials.

Figure 11.

Color difference values of tile matrix reinforced with different PDMS–OH contents.

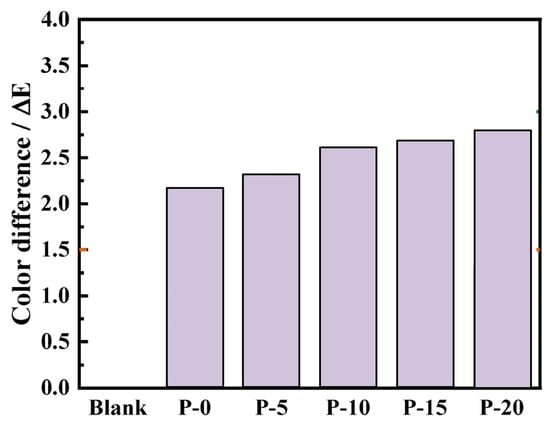

6.2. Hardness

The shore hardness values of the TEOS and PDMS–OH/TEOS-coating materials specimens are displayed in Figure 12a. The Shore D hardness indenter load is 44.5 Newtons, with a holding time of 3 s. The type of the Rockwell hardness equipment is D, the impact energy is 11 millijoules, the measurement angle is 90 degrees, and the average value of five repeated readings is taken. The unreinforced specimens’ shore hardness values varied from 79.8 HD to 80.5 HD. The TEOS-reinforced specimens had a shore hardness value of 80.7 HD, which was marginally greater than the unreinforced specimens’ 80.2 HD. Following the addition of PDMS–OH, a similar trend was noted. The main purpose of shore hardness testing is to describe how hard the tile matrix surface is. After reinforcement, the surface hardness value of the reinforced specimens did not change appreciably, suggesting that the coating materials had high general permeability and did not collect unduly on the surface [32].

Figure 12.

Shore hardness, Leeb hardness, and rate of change in the matrix of samples with different PDMS–OH contents: (a) Shore hardness; (b) Leeb hardness.

Figure 12b shows the Leeb hardness values of the TEOS and PDMS–OH/TEOS-reinforced specimens. The Leeb hardness values of the tile matrix before and after coating materials were tested for each specimen. The rate of change was calculated and analyzed based on the unreinforced specimens [33]. The Leeb hardness value of the TEOS-reinforced specimens increased by 18.63%, while the Leeb hardness value of the specimens after the addition of PDMS–OH showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. Among the samples, P-10 showed the highest growth rate, with a 21.4% increase in Leeb hardness after reinforcement, followed by a 21.1% increase. The lowest growth rate was observed in P-20, at 12.3%. Leeb hardness testing primarily characterizes the overall reinforcement effect of the samples. The coating materials PDMS–OH/TEOS significantly improved the mechanical properties of the tile matrix. PDMS–OH addition levels of 10% and 15% yielded better results.

6.3. Fetal Permeability Analysis

The porous structure of the glazed tile matrix facilitates the penetration of coating materialss. To evaluate the penetration effect of ethanol on the coating materialss, the penetration depth of each coating materials was tested, and the results are shown in Figure 13 and Table 5. The penetration depth of the TEOS-reinforced sample was approximately 3 mm. After adding PDMS–OH, the penetration depth reached 6 mm, equivalent to twice that of the TEOS sample. In the PDMS–OH/TEOS coating materials, the penetration depth of the samples showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing after adding ethanol. The maximum penetration depth, 9.5 mm, was achieved when the ethanol addition was 10%, approximately 3.2 times that of the TEOS sample and 1.6 times that of the E-0 sample. When the ethanol addition exceeded 15%, the decreasing trend in penetration depth became very obvious. The experiment shows that the addition of PDMS–OH and ethanol is beneficial to improving the penetration depth of the TEOS coating materials [34], but the ethanol addition should not exceed 15%. In the PDMS–OH/TEOS reinforcement system, the penetration effect was best when the addition amount was 10%. The experimental results on water absorption, surface water resistance, and mechanical properties also show that the reinforcement effect is better at this amount of addition.

Figure 13.

Penetration morphology of coating materialss.

Table 5.

Penetration depth of each coating materials.

6.4. Micromorphological Analysis

The microstructure and morphology of the samples are shown in Figure 14. The glazed tile matrix has a porous structure with numerous pores on its surface and inside. After environmental degradation, the pores gradually increase in both size and number, and particle connectivity decreases. Not only are there large pores, but also smaller pores within the network structure between particles [35]. SEM–EDS analysis further shows that the degraded areas exhibit a noticeable reduction in alkali and lead elements, accompanied by a relative increase in Si-rich residues, indicating selective leaching during acid and moisture exposure. This elemental redistribution is consistent with the weakened bonding and the formation of a more friable surface layer. The weakened peaks associated with Q3 and Q2 units reflect depolymerisation of the glassy phase, confirming that environmental ageing disrupts the Si–O framework and enhances structural fragility. These spectroscopic observations correspond well with the SEM morphology, jointly revealing that chemical leaching and network breakdown are key drivers of pore enlargement and particle detachment.

Figure 14.

Microstructure of Blank, P-0, and E-10 samples: (a,b) Blank sample; (c,d) P-0 sample; (e,f) E-10 sample.

After reinforcement, the pore size of samples P-0 and E-10 was significantly reduced. The coating materials filled part of the pore network, and the matrix surface became smoother. This is consistent with SEM–EDS results showing a more uniform Si distribution after treatment, indicative of the TEOS-derived inorganic network penetrating and stabilising the degraded areas. The water absorption rate of the reinforced samples was significantly reduced, supported by the observed decrease in open porosity in the microstructural images. The main reasons are as follows: first, the matrix surface becomes hydrophobic, making it more difficult for water to penetrate. Second, the coating materials adheres to particles and fills internal pores. After reinforcement, the matrix porosity decreases, the structure becomes denser, and mechanical properties are significantly improved.

In summary, PDMS–OH/TEOS coating materialss substantially improve the water resistance and mechanical properties of glazed tiles. The coating materials fills internal pores and binds matrix particles [36], reducing porosity while increasing overall density. The inorganic network generated from TEOS hydrolysis copolymerizes with the terminal hydroxyl groups of PDMS–OH to form Si–O–Si bonds, increasing the proportion of silicate bridging structures and strengthening the matrix. Meanwhile, the introduction of organic groups enhances surface hydrophobicity, further reducing water absorption.

7. Conclusions

This study systematically analyzed and experimentally investigated the degradation mechanism and protection technology of glazed tile components in ancient buildings in Shanxi Province. Through a comprehensive investigation of the preservation status and damage types of glazed tiles in typical ancient buildings, the formation mechanism of a series of degradation processes, including glaze cracking, body powdering, and salt corrosion, caused by external environmental factors, was revealed. Based on this, this study used a hydroxyl-terminated PDMS–OH/TEOS reinforcement system with ethanol as a solvent to conduct reinforcement experiments on damaged bodies. Through systematic testing of color difference, water resistance, and mechanical properties, a suitable formula was selected. Furthermore, for glazed tile components that were severely damaged and beyond repair, this study successfully fired new glazed tiles with better mechanical properties by optimizing the particle size of the body raw materials, providing a feasible path for replacing irreversibly damaged components. By adjusting the reinforcement formulation according to local material composition, the proposed PDMS–OH/TEOS-based conservation strategy can be applied as a generalizable approach for safeguarding glazed components in diverse heritage environments.

Although this study has achieved preliminary results in the analysis of degradation mechanisms and the selection of coating materials, some limitations remain. For example, simulated environmental experiments cannot fully reproduce the complex processes of natural weathering over many years. The long-term weather resistance, UV aging behavior, and interfacial stability of the coating materials still require further verification. The durability of new glazed tiles and their compatibility with historical materials under long-term coexistence conditions also lack systematic evaluation. Future work will involve constructing a long-term accelerated aging system that more closely approximates actual exposure environments to assess the durability of the reinforcement effect. Advanced micro-area analysis and in situ tracking technologies will be combined to deepen our understanding of the degradation mechanism of glazed tiles. In terms of protective materials, we will explore more novel inorganic–organic hybrid systems with low intervention and high stability.

Author Contributions

Y.C. was responsible for the initial draft. N.W. was responsible for collecting experimental materials. L.Y. was responsible for data analysis. L.Q. and S.Z. were responsible for the experiments. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Project of the Key Laboratory of Culture and Tourism for Traditional Thermal Forming Craft and Digital Design: Digital Information Resource Organization and Translation of Ceramic-Glass Fusion Methods, Project No.: TK2022032207 and Guangzhou Philosophy and Social Sciences “14th Five-Year Plan” Project: Compilation and Research on the Series of Images of the Baiyue “Feathered Figures in Boat Races”, Project No.: 2025GZQN43.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Klesner, C.E. The Regional Production, Consumption, and Trade of Glazed Ceramics in Medieval Central Asia. Doctoral Dissertation, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kaliyannan, G.V.; Rathanasamy, R.; Gunasekaran, R.; Sivaraj, S.; Kandasamy, S.; Rao, S.K.; Ceramics, P.O. Defects Engineering in Electroceramics for Energy Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 53–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Shang, S.; Wang, X.; Hu, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Non-firing Synthesis for Oxides: From Natural to Synthetic Forms with Energy-Efficient and Sustainable Processes. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 33, 11411–11437. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Hu, S.; Peng, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yu, J.; Yuan, L. Thermal shock resistance of WC–Cr3C2–Ni coatings deposited via high-velocity air fuel spraying. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 487, 131034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, F.; Jia, W.; Guo, Y. Study on the Surface Coating Techniques of Furniture in the Long’en Hall of Qing Changling Mausoleum. Coatings 2025, 15, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, M.; Jin, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Sun, M.; Cao, M.; Cui, J. Application of smalt in building glazed tiles from Yuanmingyuan Park, Beijing’in Qing dynasty. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 282. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Zhang, H.; Tu, Y.; Sun, S.; Li, Y.; Ding, H.; Bai, M.; Chang, L.; Zhang, J. Preparation and Application of Apatite–TiO2 Composite Opacifier: Preventing Titanium Glaze Yellowing through Pre-Combination. Materials 2024, 17, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, H.A.; Şahin, R. Radon, concrete, buildings and human health—A review study. Buildings 2024, 14, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Esteves, A.C.C.; Yang, J.; Zhou, S. Zwitterion-bearing silica sol for enhancing antifouling performance and mechanical strength of transparent PDMS coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 191, 108415. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, L. The Non-Destructive Testing of Architectural Heritage Surfaces via Machine Learning: A Case Study of Flat Tiles in the Jiangnan Region. Coatings 2025, 15, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malet-Damour, B.; Bigot, D.; Rivière, G. Experimental and Numerical Analysis on a Thermal Barrier Coating with Nano-Ceramic Base: A Potential Solution to Reduce Urban Heat Islands? Eng 2023, 4, 2421–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francke, B.; Kula, D.; Koda, E. Analysis of the Durability of Thermal Insulation Properties in Inverted Foundation Slab Systems of Single-Family Buildings in Poland. Buildings 2025, 15, 3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Wang, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, Z. Deciphering and Preserving the Landscape Genes of Handicraft Villages from the Perspective of Production–Living–Ecology Spaces (PLESs): A Case Study of YaoTou Village, Shaanxi Province. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 3810.12-2016; Test Methods of Ceramic Tiles—Part 12: Determination of Frost Resistance. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Abdelmoniem, A.M. Preserving the wooden heritage of the National Police Museum: Challenges and conservation strategies. J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resil. 2025, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Azad, M.M.; Kim, H.S.; Yoon, Y.; Lee, H.; Choi, K.S.; Yang, Y. A review on traditional and artificial intelligence-based preservation techniques for oil painting artworks. Gels 2024, 10, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradell, T.; Molera, J. Ceramic technology. How to characterise ceramic glazes. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.J.; Tulyaganov, D. Traditional ceramics manufacturing. In Ceramics, Glass and Glass-Ceramics: From Early Manufacturing Steps Towards Modern Frontiers; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 75–118. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, E.; Mostafa, N.; Khoury, J.; Merhej, T.; Lteif, R. Glaze surface defects causes and prevention controls. J. Ceram. Sci. Technol. 2023, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mourou, C.; Zamorano, M.; Ruiz, D.P.; Martín-Morales, M. Characterization of ceramic tiles coated with recycled waste glass particles to be used for cool roof applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 398, 132489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balliana, E.; Caveri, E.M.C.; Falchi, L.; Zendri, E. Tiles from Aosta: A peculiar glaze roof covering. Colorants 2023, 2, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijerathne, D.T.; Wahala, S.B.; Asmone, A.S. Advancing environmental sustainability of ceramic tile production: A cradle-to-gate life cycle assessment case study from Sri Lanka. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1654253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawryluk, M.; Marzec, J. Problems related to the operation of machines and devices for the production of ceramic roof tiles with a special consideration of the durability of tools for band extrusion. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2024, 25, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corregidor, V.; Ruvalcaba-Sil, J.L.; Prudêncio, M.I.; Dias, M.I.; Alves, L.C. Ion Beam-Induced Luminescence (IBIL) for Studying Manufacturing Conditions in Ceramics: An Application to Ceramic Body Tiles. Materials 2024, 17, 5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritti, N.; Power, R.M.; Graves, A.; Huisken, J. Image restoration of degraded time-lapse microscopy data mediated by near-infrared imaging. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 311–321. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, S.; Luo, Q.; Lu, Z.; Wang, F.; Shi, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, J. A novel thermal-tailored strategy to mitigate thermal cracking of cement-based materials by carbon fibers and liquid-metal-based microencapsulated phase change materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 428, 136338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Es-Soufi, H.; Berdimurodov, E.; Sayyed, M.; Bih, L. Nanoceramic-based coatings for corrosion protection: A review on synthesis, mechanisms, and applications. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 16978–17004. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Li, K.; Li, M.; Dopphoopha, B.; Zheng, J.; Wang, J.; Du, S.; Li, Y.; Huang, B. Pushing radiative cooling technology to real applications. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2409738. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Ma, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, N.; Song, S. Corrosion of glaze in the marine environment: Study on the green-glazed pottery from the Southern Song “Nanhai I” shipwreck (1127–1279 AD). Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 134. [Google Scholar]

- Macedo, M.F.; Vilarigues, M.G.; Coutinho, M.L. Biodeterioration of glass-based historical building materials: An overview of the heritage literature from the 21st century. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanaszek-Tomal, E. Microorganisms in Red Ceramic Building Materials—A Review. Coatings 2024, 14, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliwa, K.; Kozub, B.; Łoś, K.; Łoś, P.; Korniejenko, K. Assessment of durability and degradation resistance of geopolymer composites in water environments. Materials 2025, 18, 3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Xu, J.; Ji, Y.; Fan, H.; Li, L.; Meng, M. Tensile strength and deformation properties of fiber-reinforced loess: Laboratory and numerical investigation. Acta Geotech. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, N.H.A.; Ismail, W.N.W.; Yusop, H.M.; Zulkifli, N.F.M. Synthesis of a water-based TEOS–PDMS sol–gel coating for hydrophobic cotton and polyester fabrics. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 933–950. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, M.A.; Aghighi, M.; Barralet, J.; Gostick, J.T. Pore network modeling of reaction-diffusion in hierarchical porous particles: The effects of microstructure. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 330, 1002–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njindam, O.; Njoya, D.; Mache, J.; Mouafon, M.; Messan, A.; Njopwouo, D. Effect of glass powder on the technological properties and microstructure of clay mixture for porcelain stoneware tiles manufacture. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 170, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).