Abstract

The rapid advancement of fifth-generation (5G) communication technologies has increased the demand for high-frequency circuits that offer high signal transmission rates and low latency. Traditional epoxy resin materials, characterized by their high dielectric constant (εr) and dielectric loss (tanδ), lead to significant signal attenuation and reflection in high-frequency applications, thus limiting their suitability for modern communication devices. Accordingly, reducing the dielectric constant and dielectric loss of epoxy resins has become a prominent research focus in materials science. This paper reviews various methods for developing low-dielectric epoxy resin composites, emphasizing strategies to reduce polarization and material density. It subsequently provides a concise analysis of the advantages and current challenges associated with each technique and offers insights into potential future research directions.

1. Introduction

Epoxy resins exhibit good mechanical properties, heat resistance, electrical insulating properties, and processability, making them widely employed in electronic components [1]. Meanwhile, the rapid advancement of the fifth-generation (5G) mobile communication technologies has created a growing demand for high-frequency circuits that offer high transmission rates and low latency [2]. Therefore, to meet the demands of these applications, more stringent requirements are being placed on the dielectric properties of polymer-based substrate materials such as epoxy resins.

In high-frequency circuits, the dielectric constant (εr) of the substrate material is a critical parameter that influences signal propagation delay and signal loss due to reflection [3]. According to the relationship v ≈ c/, a lower dielectric constant enables a faster signal propagation speed. Furthermore, a lower dielectric constant contributes to a higher characteristic impedance in the transmission lines, which facilitates better impedance matching between the substrate and signal lines [4]. Improved impedance matching minimizes signal reflection at the interface, thereby reducing signal loss. To achieve efficient high-speed transmission in high-frequency circuit boards, it is crucial for the substrate material to maintain a stable, low dielectric constant. The imperative to reduce signal propagation delay (or RC delay) by employing materials with a lower dielectric constant has been a long-standing driver in the evolution of microelectronics, particularly for interconnects and packaging [5]. With the advent of 5G and beyond, this requirement has become even more stringent, extending to the substrate and encapsulation materials themselves.

Dielectric loss in conductive circuits is primarily influenced by the dielectric constant (εr) and the loss tangent (tanδ) of the substrate material’s insulating [6]. This loss is directly proportional to both εr and tanδ, and it increases with the operating frequency. At higher frequencies, the dielectric loss becomes more pronounced, leading to greater signal attenuation during transmission through the substrate. Therefore, for efficient high-speed transmission in high-frequency circuit boards, it is essential to select substrate materials with low dielectric constant and loss tangent values. Additionally, other material properties, such as thermal stability and mechanical strength, must be considered to ensure overall performance and reliability [7].

Epoxy resins are widely used in electronic packaging, including the coating and encapsulation of printed circuit boards and discrete transistors [8]. However, their relatively high dielectric constant and loss tangent limit their application in high-frequency and high-speed communication technologies [9]. Materials with a ‘low’ dielectric constant are typically those with an εr significantly below 4.0 at GHz frequencies. For polymer-based substrates targeting advanced applications such as 5G/6G, the research frontier often aims for εr < 3.0, approaching the performance of benchmark materials like polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE, εr ≈ 2.1). This review adopts this performance-oriented perspective, focusing on strategies to reduce the εr of epoxy resins from their conventional range (3.5–4.5 for DGEBA) towards these lower targets. A comparative overview of the dielectric constants of relevant materials, providing concrete numerical benchmarks, is presented in Table 1. Therefore, developing methods to reduce the dielectric constant and loss of epoxy resins without significantly increasing cost constitutes a significant research focus.

Table 1.

Typical dielectric constant (εr) ranges of common materials at radio frequencies (~1–10 GHz).

Consequently, the development of low-dielectric epoxy composites is driven by stringent and multi-faceted requirements from advanced application fields. For instance [8], in 5G/6G communication infrastructure (e.g., RF front-end modules and mmWave antennas), materials must exhibit a stable and low dielectric constant (typically targeting εr < 3.2, with advanced goals approaching 2.5) and an extremely low loss tangent (tan δ < 0.005) across a broad frequency range (1–100 GHz) to ensure signal integrity. In high-performance computing and advanced packaging, alongside high-frequency performance, materials are required to maintain stable dielectric properties over a wide temperature range (e.g., −55 °C to 150 °C or beyond) and possess a high glass transition temperature (Tg) and dimensional stability to withstand reflow soldering and thermal cycling. For aerospace and defense electronics, materials face even more extreme conditions, including wider operational temperatures (−65 °C to 180 °C), high vacuum, and radiation resistance. This review will subsequently evaluate each preparation strategy not only by its efficacy in reducing εr and tan δ but also by its impact on these critical application-specific parameters (e.g., thermal stability, mechanical strength, moisture resistance), thereby linking material design to potential application scenarios. This review first summarizes the fundamental factors influencing dielectric properties, and then comprehensively reviews recent advances in the preparation of low-dielectric epoxy resins.

2. Influential Factors on the Dielectric Performance of Low-Dielectric Epoxy Resins

The dielectric properties of materials are typically characterized by two key parameters: the dielectric constant (εr) and the loss tangent (tan δ). Among these, the dielectric constant is a primary parameter for evaluating dielectric performance [10]. It indicates the degree of polarization a material undergoes when exposed to an electric field. Polarization is the process in which the positive and negative charge centers of the constituent microscopic particles (such as atoms, ions, and molecules) within the dielectric material are displaced under an external electric field, forming electric dipoles. Several factors influence the extent of polarization, including the material’s lattice structure, crystal orientation, electronegativity of atoms or functional groups, as well as external conditions such as temperature and pressure, among others.

The dielectric properties of materials are primarily characterized by the dielectric constant (εr) and the loss tangent (tan δ). The dielectric constant (εr) measures a material’s polarization—the displacement of positive and negative charge centers to form electric dipoles—under an applied electric field. The extent of this polarization depends on several intrinsic and extrinsic factors. For polymer materials like epoxy resins, key intrinsic factors include molecular polarizability, backbone flexibility, the polarity and density of functional groups, and free volume. Critical extrinsic conditions include temperature and the frequency of the applied electric field. A detailed understanding of these factors provides the foundation for designing low-dieconstant epoxy resins.

Dielectric loss [11] refers to the energy dissipated as heat within a dielectric material due to its lagging response to an alternating electric field. This response is characterized by a material-specific relaxation time. At low frequencies, the electric field oscillates slowly enough that the polarization can fully develop in phase with the field, resulting in minimal energy loss. At high frequencies, however, the field alternates too rapidly for the polarization to keep up, causing a phase lag between the polarization and the field. This phase lag, quantified by the loss tangent (tan δ), leads to significant energy dissipation. This fundamental mechanism causes the dielectric constant and loss to vary with frequency, a phenomenon known as “frequency dispersion.” The specific dispersion behavior is governed by the polarization mechanisms present in the material. In composite materials, additional dispersion can arise from interfacial polarization, which is often enhanced by specific morphologies such as sheet-like structures, anisotropic filler orientation, or high filler loadings.

The magnitudes of the dielectric constant (εr) and loss tangent (tan δ) for a material are primarily determined by its polarization mechanisms. In general, enhanced polarization leads to a higher dielectric constant and greater dielectric loss, a relationship classically described for polar materials by the Debye equation [12] (Equation (1)). However, the Debye model is an idealization, and real materials often exhibit more complex behavior that is more accurately described by distributions of relaxation times.

In Equation (1), εr represents the relative dielectric constant, ρ is the material density, and ε0 is the vacuum permittivity. This equation describes the combined contribution of different polarization mechanisms to the overall dielectric constant. The terms ae, ad, and (μ2/3kT) correspond to the electronic, ionic, and orientational polarizabilities of the material, respectively. Consequently, a reduction in the material’s density or in any component of its polarizability can lead to a decrease in its dielectric constant [13].

The electronegativity difference between two bonded atoms causes a shift of the electron cloud toward the more electronegative atom, which is a primary origin of ionic polarizability. Polarizability (α) is quantitatively defined as the ratio of the induced dipole moment (p) to the local electric field (E) that induced it, i.e., α = p/E [14]. Microscopically, the total polarizability arises from electronic, ionic, and orientational contributions. Therefore, reducing the material’s polarizability typically requires incorporating less-polarizable chemical groups and increasing bond strength, thereby minimizing the formation of induced dipoles under an applied electric field.

However, the Debye model is an idealization, and real materials often exhibit more complex behavior that is more accurately described by distributions of relaxation times. To quantitatively capture this non-ideal dielectric response, empirical models such as the Cole–Cole (CC) and Havriliak–Negami (HN) models are widely employed [15]. The CC model introduces a symmetric broadening of the relaxation peak, while the more general HN model accounts for both symmetric and asymmetric broadening through two shape parameters (α and β). These models provide a powerful phenomenological framework for analyzing the dielectric spectra of poly composites, especially in deconvoluting overlapping relaxation processes arising from dipole orientation, interfacial (Maxwell–Wagner–Sillars) polarization, and ionic conduction [16]. For instance, in a study on polyurethane/halloysite nanotube composites, the HN model successfully decoupled the interfacial polarization contribution from the polymer chain segmental relaxation, revealing how nanofiller loading and dispersion quality alter the relaxation time distribution and DC conductivity [17]. This analytical approach is crucial for guiding the design of epoxy composites with targeted dielectric loss characteristics across specific frequency ranges. The principles and modeling techniques exemplified here are directly applicable to the analysis and development of advanced low-dielectric epoxy resin systems.

To summarize, the design of low-dielectric epoxy resins hinges on manipulating these fundamental factors. Reducing polarizability (by introducing low-polarity groups or restricting dipole motion) directly lowers both εr and tan δ, enhancing signal integrity in high-speed transmission. Introducing tailored interfaces (e.g., via nanofillers) can dominate the dielectric response through interfacial polarization; when well-controlled, these interfaces trap charges and increase resistivity, crucial for electrical insulation reliability, but if mismatched, they become loss centers. Reducing density via porosity primarily decreases εr by volumetrically diluting polarizable matter, beneficial for lightweight and low-permittivity substrates, though often at a cost to mechanical strength. The following sections review specific strategies through this lens of targeted mechanism manipulation for desired functional outcomes.

In practical applications, tailoring material polarizability and density serves as an effective strategy for reducing both the dielectric constant and dielectric loss. For instance, introducing low-polarity groups or increasing free volume diminishes the material’s polarizability under an electric field, thereby lowering the dielectric constant. Furthermore, incorporating porous structures or hollow fillers reduces the material’s density, which also contributes to a reduction in dielectric loss.

3. Reducing Polarization Rate to Prepare Low-Dielectric Epoxy Resin

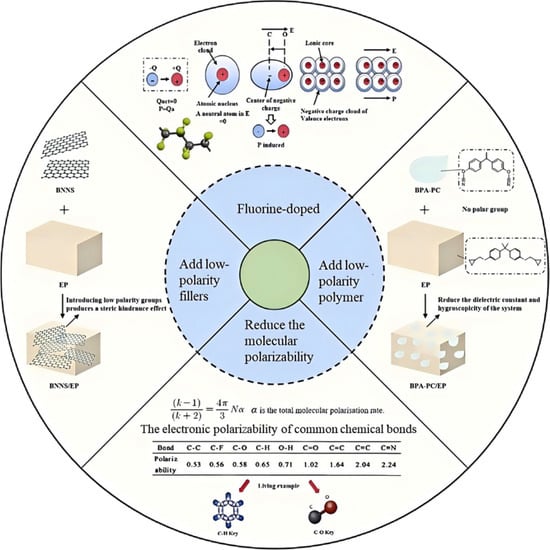

As established, reducing a material’s polarizability is an effective strategy for achieving a lower dielectric constant. As illustrated in Figure 1. This reduction can be achieved through two primary approaches: decreasing the number or strength of permanent dipoles within the material and increasing the binding energy of its constituent atoms’ electron clouds.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the approach for reducing the polarizability of the epoxy resin.

3.1. Preparation of the Low-Dielectric Epoxy Resin Through Fluorine Doping

Fluorine incorporation is a prominent strategy for reducing the polarizability of dielectric materials [18]. The high electronegativity of fluorine atoms withdraws electron density, which weakens intermolecular interactions and localizes charge distribution within the polymer matrix. In epoxy resins, the introduction of C–F bonds not only reduces electronic polarizability but also increases free volume due to steric constraints. These combined effects suppress the induced dipole moment under an applied electric field, thereby decreasing the overall polarizability. For instance, Sasaki et al. [19] synthesized a fluorinated anhydride curing agent for a bisphenol A-based epoxy resin. The resulting fluorinated epoxy system exhibited a dielectric constant of 2.7, whereas the analogous system cured with a non-fluorinated anhydride agent under identical conditions showed a value of approximately 3.2.

In a related study, Zhiqiang Tao et al. [20] synthesized a novel fluorine-containing epoxy resin and investigated its curing behavior with two distinct agents, methylhexahydrophthalic anhydride (MHHPA) and diaminodiphenylmethane (DDM), with curing conducted at room temperature. Compared to a conventional bisphenol A epoxy resin cured under identical conditions, the fluorinated epoxy exhibited a lower dielectric constant: 3.3 versus 3.5 when cured with MHHPA, and 3.2 versus 3.6 when cured with DDM. Separately, J. R. Lee et al. [21] also employed DDM as a curing agent and reported that a fluorine-containing epoxy resin achieved a 15% reduction in dielectric constant—from approximately 3.8 to 3.2—across a frequency range of 10 Hz to 106 Hz at room temperature, relative to a standard DDM-cured bisphenol A epoxy system. Focusing on targeted molecular design, T. Na et al. [22] synthesized both a fluorinated epoxy monomer (3-(trifluoromethyl)phenylhydroquinone-based epoxy, 3-TFM EP) and a structurally complementary fluorinated curing agent (4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl benzimidazole, 4-TFM BI). The resulting fully fluorinated (all-fluorinated) 3-TFM EP/4-TFM BI system attained a dielectric constant of 3.38 measured at 107 Hz and room temperature.

The incorporation of intrinsically low-dielectric fillers, such as polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), represents an effective strategy for reducing both the dielectric constant and dielectric loss tangent of epoxy resins. PTFE, a prototypical material in this category, possesses a helical molecular structure that confers high symmetry to its C–F bonds, leading to the cancellation of the individual bond dipole moments [23]. This unique structural attribute is the origin of its intrinsically low dielectric constant and loss. For instance, S. J. Mumby et al. [24] demonstrated that incorporating 35.3 vol% of PTFE into an epoxy resin reduced both the dielectric constant and the dielectric loss tangent of the resulting composite by approximately 25% across a broad frequency range from 10 Hz to 1 GHz, relative to the neat epoxy resin.

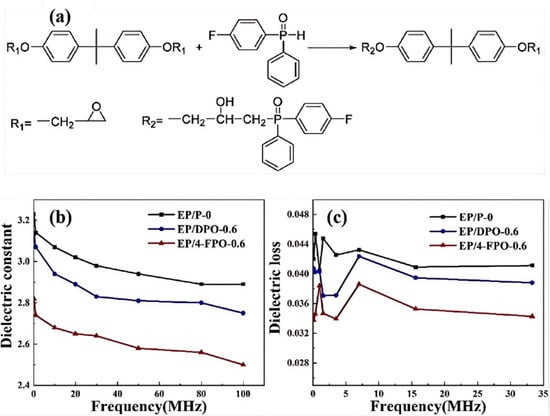

Duan et al. [25] developed a low-dielectric epoxy resin by incorporating (4-fluorophenyl)(phenyl)phosphine oxide (4-FPO) as a functional modifier (Figure 2a). The introduction of the 4-FPO moiety reduced the dielectric constant to 2.74 and substantially lowered the dielectric loss tangent at 1 MHz (Figure 2b,c). The authors primarily attributed this improvement to the low intrinsic polarizability of the C–F bonds. Moreover, the 4-FPO modification enhanced the material’s hydrophobicity, as indicated by a water contact angle of 100.1°, and consequently reduced its water absorption. Although the study primarily focused on dielectric properties, it also reported that the phosphorus-containing 4-FPO structure concurrently imparted flame retardancy.

Figure 2.

(a) Reaction of (4-fluorophenyl)(phenyl)phosphine oxide (4-FPO) with the diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A (DGEBA); (b) Dielectric constant of the modified epoxy resin; (c) Dielectric loss of the modified epoxy resin [25].

The dielectric performance of a material is characterized by two key parameters: the dielectric constant (εr) and the dielectric loss tangent (tan δ). The dielectric constant reflects the material’s polarization capability under an electric field, whereas the loss tangent represents the energy dissipated as heat. In high-frequency applications, a low dielectric constant is critical to minimize signal propagation delay, while a low loss tangent is essential to reduce signal attenuation, thereby collectively ensuring signal integrity. Consequently, the development of advanced dielectric materials focuses on the concurrent optimization of these two interdependent properties. The significant reduction in both εr and tan δ, coupled with enhanced hydrophobicity, positions fluorinated epoxy resins as prime candidates for critical passive components in mmWave front-end modules and high-frequency circuit substrates, where minimizing signal loss and environmental interference is paramount. However, the associated cost and synthesis complexity must be weighed against the performance requirements of the target application.

3.2. Preparation of the Low-Dielectric Epoxy Resin by Adding Low-Polarity Functional Modifiers to Epoxy Resin Matrices

3.2.1. Addition of Low-Polarity Nano-Fillers

The incorporation of low-polarity nanofillers into epoxy resin can reduce the material’s polarizability. The interfaces formed between the nano-components and the resin matrix exert a certain inhibitory effect on dipole polarization, while simultaneously generating a spatial shielding effect that effectively impedes the propagation of electric fields within the resin. This approach not only effectively lowers the dielectric constant but also enhances the mechanical properties of the resin [26]. For example, Jianwen Zhang et al. [27] improved the dispersion of silica nanoparticles by grafting them with carboxyl-terminated hyperbranched polyester. In the resulting composite, a loading of 5 wt% of these grafted silica nanoparticles yielded a dielectric constant of 2.45 at 104 Hz, which constitutes a 26% reduction compared to the neat epoxy resin. In a separate study, Z. Wang et al. [28] achieved a 21% reduction in the dielectric loss tangent at 106 Hz by incorporating 2 wt% of boron nitride nanosheets (BNNSs). It is noteworthy that better dispersion between the filler and the matrix can reduce the degree of polarization [29].

Montmorillonite (MMT) [30], a low-polarity layered aluminosilicate, is widely utilized in epoxy composites due to its potential for good dispersion, comparative ease of processing, and its capacity to simultaneously enhance mechanical and thermal properties. Illustrating this versatility, Qin et al. [31] employed a phosphonium bromide-modified organo-montmorillonite (DPAB-MMT)—synthesized via the intercalation of a DOPO-based phosphonium salt (DOPO-ATPB)—to concurrently improve the flame retardancy and dielectric performance of an epoxy resin. The incorporation of 8 wt% of this modified clay significantly reduced the dielectric loss (with the loss factor, ε″, decreasing from 0.080 to 0.052 at 100 Hz), increased the flexural strength by approximately 13%, and improved key flame-retardant metrics, including the limiting oxygen index (LOI) and the peak heat release rate (pHRR). In a related study that demonstrates the efficacy of low filler loading, Jun Lin et al. [32] reported that adding only 1 wt% of montmorillonite resulted in a dielectric constant of 3.26 and a dielectric loss tangent of 0.008 at 102 Hz, corresponding to reductions of 5% and 33.3%, respectively, compared to the neat epoxy resin.

The reduction in dielectric loss (ε″) in this system can be attributed to two interrelated mechanisms: (1) The layered silicate structure acts as a barrier, physically impeding the migration and orientation of charge carriers and dipoles, thereby suppressing orientational polarization and conduction loss. (2) The organo-modification improves compatibility, leading to a well-dispersed, intercalated structure. This maximizes the filler–matrix interfacial area but minimizes large-scale charge accumulation, allowing for a more controlled interfacial polarization that contributes to permittivity modulation without excessively increasing loss. This synergy between suppressed dipole motion and managed interface polarization directly enhances the material’s performance in applications requiring low signal attenuation.

Silicon carbide (SiC) is an attractive filler for epoxy composites due to its chemical inertness, high thermal conductivity, excellent high-frequency electrical insulation properties, and cost-effectiveness. When incorporated into an epoxy resin, the interfaces surrounding the SiC nanoparticles can facilitate charge dissipation, potentially by creating pathways for charge carriers. This process reduces the strength of the internal electric field, the suppression of which directly diminishes interfacial polarization and thereby lowers the dielectric constant. As demonstrated by X. Chen et al. [33], a composite containing 1 wt% nano-SiC achieved a dielectric constant of 3.8 at 102 Hz, corresponding to a 9% reduction from the value of the neat epoxy resin (approximately 4.18).

These low-polarity fillers provide the significant advantage of concurrently reducing both the dielectric constant and loss tangent, often with enhanced cost-effectiveness. However, exceeding the optimal filler loading induces pronounced interfacial polarization, a phenomenon primarily arising from inadequate chemical compatibility and physical adhesion at the filler–matrix interface. This can paradoxically increase the composite’s dielectric constant and loss. Therefore, meticulous optimization of filler content and the implementation of strategies to enhance interfacial compatibility—such as surface modification—are critical for achieving superior and reliable dielectric performance in epoxy composites.

3.2.2. Incorporation of Low-Polarity Polymers

Copolymerization or blending with inherently low-polarity polymers represents an effective strategy for reducing the overall polarizability of epoxy resins [34]. This approach dilutes the concentration of polar groups within the material, effectively reducing the number of dipoles capable of reorienting under an electric field. Furthermore, the incorporation of bulky molecular segments or rigid conjugated structures introduces steric constraints that restrict the rotational mobility of intrinsic dipoles, particularly those associated with hydroxyl groups in the cross-linked network. This suppression of dipole motion thereby leads to a reduction in the system’s overall polarizability.

Polyphenylene Oxide (PPO) is a low-polarity engineering thermoplastic characterized by its high thermal stability, chemical resistance, and intrinsically low dielectric constant, which has led to its widespread use in 5G applications and makes it a promising candidate for advanced electronics [35]. However, the utilization of PPO in epoxy composites is challenged by its inherent high melt viscosity, poor flowability, and low notch impact strength [36], which often necessitate chemical modification or the formation of alloys to ensure compatibility and meet the performance requirements of the final composite material.

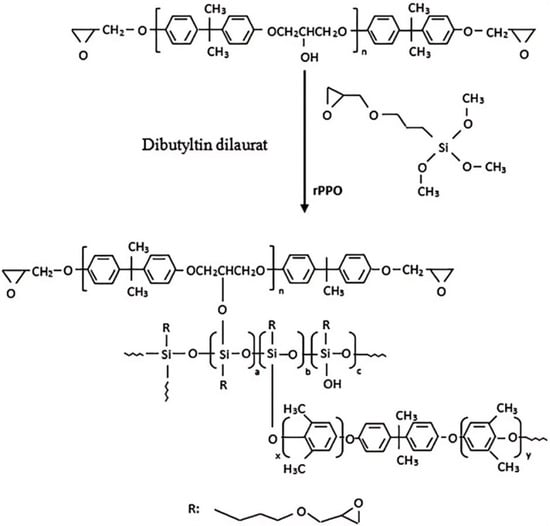

This modification strategy has been successfully implemented in several studies. For instance, H. J. Hwang et al. [37] synthesized a low-dielectric thermosetting system by curing a standard epoxy resin with a low-molecular-weight PPO oligomer containing a conjugated main-chain structure, which resulted in the formation of an interpenetrating polymer network (IPN). This IPN structure reduced the dielectric constant from 3.70 to 2.63 at 1 GHz. In a different approach, W. L. Weng et al. [38] prepared low-molecular-weight PPO (redistributed PPO, rPPO) via a redistribution reaction and blended it as a modifier into an epoxy resin (see Figure 3). The incorporation of rPPO significantly enhanced the overall material performance, yielding a dielectric constant of 3.76 and a dielectric loss tangent of 2.11 × 10−3 at 107 Hz, while also increasing the maximum thermal decomposition temperature to 421 °C.

Figure 3.

Reactions between rPPO and EP [38].

Cyanate ester (CE) is a low-polarity thermosetting polymer recognized for its low moisture absorption, high glass transition temperature (Tg), and low dielectric constant, making it attractive for high-frequency electronic applications [39,40]. In contrast, its widespread adoption is hindered by a high curing temperature, cost, and inherent brittleness [40]. Blending CE with epoxy resin represents a promising strategy to mitigate these limitations. This approach synergistically combines the low polarizability of CE with the superior processability and toughness of epoxies. The resulting hybrid systems exhibit a reduced overall concentration of polar groups, which serves to lower the dielectric constant and water absorption, while the incorporation of rigid CE-derived structures concurrently enhances thermal stability.

The efficacy of this strategy is demonstrated by the work of C. P. Li et al. [41], who showed that conventional DGEBA epoxy (dielectric constant, Dk > 3.5; loss tangent, tan δ > 0.3) is unsuitable for high-frequency packaging, whereas CE/epoxy hybrids exhibited markedly superior dielectric performance. For instance, one CE-cured BP epoxy formulation showed exceptional dielectric thermal stability: its dielectric constant remained below 3.2 at 150 °C after measuring 2.47 at −125 °C, tested at 10 kHz. Furthermore, these hybrid materials effectively suppressed dielectric loss, maintaining a tan δ below 0.04 across the evaluated temperature range, thereby significantly outperforming the neat DGEBA resin (tan δ > 0.3). The optimal BP/B10 (1:1) hybrid system achieved a dielectric constant of 2.66 at 150 °C with an extremely low loss factor of approximately 0.004. These results collectively confirm that CE modification effectively reduces both permittivity and energy dissipation, offering a clear performance advantage over conventional epoxy formulations.

Other classes of low-polarity polymers and resinous materials have similarly been explored as modifiers for epoxy resins. For example, F. Fu et al. [42] designed a benzocyclobutene-rosin-based modifier to enhance high-frequency dielectric performance. In this system, the benzocyclobutene component forms a highly cross-linked network upon curing, which restricts the mobility of polar groups, thereby lowering the overall polarization response. Concurrently, the bulky rosin structure introduces additional free volume. At 15 GHz, the modified epoxy exhibited a dielectric constant of 2.72, corresponding to an approximately 13% reduction from the value of the neat resin 3.12.

Beyond merely reporting reductions in εr and tan δ, a more impactful approach involves elucidating the causal link between specific structural modifications and the resulting dielectric response within targeted application contexts. For instance [17], as demonstrated in polyurethane systems reinforced with anisotropic halloysite nanotubes, the filler’s morphology and surface chemistry dictate interfacial polarization (Maxwell–Wagner–Sillars effect) and charge trapping, which in turn govern critical application metrics such as volume resistivity and dielectric stability under electric stress. This paradigm underscores that future development of low-dielectric epoxy composites should prioritize integrated design: tailoring filler morphology, interface engineering, and polymer architecture not only to achieve low permittivity but also to co-optimize a suite of properties (e.g., thermal conductivity, mechanical strength, environmental stability) required for the specific high-frequency or high-voltage applications discussed in the Introduction.

In conclusion, the three principal strategies for developing low-dielectric epoxy materials—fluorine incorporation, the addition of low-polarity nanofillers, and blending with low-polarity polymers—effectively suppress various polarization mechanisms, thereby reducing both the dielectric constant and loss tangent. This results in synergistic enhancements in electrical insulation, mechanical performance, thermal stability, and long-term reliability. Nonetheless, each strategy presents specific challenges: fluorination often entails higher material costs and synthesis complexity; nanofillers require meticulous control over loading and dispersion to mitigate detrimental interfacial polarization; and polymer blending is frequently limited by thermodynamic incompatibility, which can lead to phase separation and property degradation. Future research should therefore prioritize the optimization of filler dispersion and interface engineering, the development of novel compatibilization strategies, and the pursuit of cost-effective synthesis routes to facilitate the advancement of next-generation, high-performance epoxy-based dielectric composites.

4. Reduction in Material Density to Prepare Low-Dielectric Epoxy Resin

The reduction in material density in epoxy systems, often achieved through the introduction of porosity, is an effective strategy for lowering the dielectric constant. This approach operates on two primary mechanisms. Firstly, increased intermolecular spacing and reduced molecular packing density diminish the number of polarizable units per unit volume. Secondly, and more significantly, the created pores (with a dielectric constant of ~1) act as a low-polarizability phase within the higher-k epoxy matrix (k~3–4). According to effective medium theories, the overall dielectric constant of the porous composite is a volumetric average of its constituents, thereby leading to a reduction proportional to the porosity fraction [43]. Beyond this volumetric averaging effect, the introduced pores physically disrupt the continuity of the polarizable epoxy matrix. This disruption impedes the long-range correlation of dipole reorientation (hindered orientational polarization) and creates a multitude of polymer–air interfaces. While these interfaces can, in theory, give rise to interfacial polarization, the extremely low conductivity and polarizability of air typically make this contribution negligible. Consequently, the dominant effect is a reduction in the effective density of polarizable units and a confinement of polarization pathways, leading to a decrease in both εr and tan δ. Consequently, the deliberate introduction of controlled porosity provides a direct and viable route to concurrently achieve lightweight characteristics and a reduced dielectric constant in epoxy-based materials.

The introduction of porosity is a highly effective strategy for reducing the dielectric constant of epoxy resins, as it leverages the ultra-low dielectric constant of air (k ≈ 1). The significantly reduced dielectric constant observed in porous silica films (as low as 1.7), compared to that of dense silica (3.9), is attributed to their porosity [44]. This concept could be translated into epoxy composites through the incorporation of porous or hollow fillers, such as hollow glass microspheres (HGMs), mesoporous silica, and polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS). For instance, increasing the volume fraction of HGMs in an epoxy matrix progressively lowers the dielectric constant, with a loading of 51.3 vol% achieving a 28.6% reduction (to a value of 2.84) [45]. Similarly, an epoxy composite containing 3 wt% mesoporous silica exhibited a 9% reduction in dielectric constant at 106 Hz [46]. The unique advantage afforded by porosity is further elucidated by comparative studies. Yamashita et al. [47] reported that at a 20 wt% loading, both mesoporous silica (with 28% intrinsic porosity) and non-porous silica reduced the dielectric constant of the epoxy composite by 7% and 9%, respectively, across a broad frequency range (10 Hz to 107 Hz). The fact that the porous filler delivers a comparable dielectric reduction—despite its lower effective solid content within the composite—powerfully underscores the dominant role of the encapsulated air voids in lowering the overall permittivity.

In another approach, porous architectures can be engineered within thermoset matrices using sacrificial polymers, also known as pore-forming agents. A representative study by J. Jiang et al. [48] involved blending a low-molecular-weight, thermally labile polycarbonate into an epoxy resin prior to its cross-linking. Subsequent controlled thermal decomposition of the sacrificial polymer yielded a well-defined microporous structure in the cured epoxy. With a generated porosity of 22.3%, the material’s dielectric constant at 104 Hz was reduced from 3.865 for the neat resin to 2.83, corresponding to a substantial reduction of approximately 26.8%.

Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) features a distinctive cage-like architecture with internal free volume, resulting in low density and a low intrinsic dielectric constant, which renders it an attractive filler for developing low-dielectric epoxy composites [49]. Jiao et al. [50] designed a sophisticated hybrid filler (POSS-MPS) by covalently grafting glycidyl POSS (G-POSS) onto the surface of amino-functionalized mesoporous silica (NH2-MPS). In the resulting epoxy nanocomposite, the G-POSS units functioned as molecular caps, serving a dual purpose: they preserved the valuable mesoporous structure of the silica by mitigating excessive epoxy resin infiltration, and they simultaneously enhanced the chemical compatibility and adhesion at the organic–inorganic interface. This ingenious design, at a mere 5 wt% loading of POSS-MPS, yielded a comprehensive performance enhancement: the dielectric constant decreased from 4.03 to 3.66, and the loss tangent (tan δ) dropped from 0.031 to 0.017. Concurrently, the mechanical and thermal properties were substantially improved, with increases in tensile strength (23.8%), Young’s modulus (43.5%), elongation at break (159.8%), and glass transition temperature (59.8%). This suite of enhancements is attributed to a synergistic mechanism combining the preserved, low-k porosity with the drastically reinforced interface, unequivocally demonstrating the efficacy of molecular-level hybridization for creating high-performance epoxy composites with integrated dielectric, thermal, and mechanical properties.

Comparative studies highlight the significant impact of chemical functionalization on the efficacy of POSS fillers in reducing the dielectric constant of epoxy resins. For instance, S. Nagendiran et al. [51] reported a 29.2% reduction at 1 MHz using 20 wt% of aminophenyl-POSS. In a notable contrast, Wang et al. [52] achieved a comparable reduction of 28.5% at the same frequency with only 10 wt% of a fluorine-functionalized epoxy POSS incorporated into a UV-curable system. The attainment of a similar dielectric reduction at half the filler loading strongly suggests a marked enhancement in efficiency, which is likely attributable to the combined effects of the low polarizability of the fluorine groups and potentially improved compatibility and dispersion within the epoxy matrix afforded by the specific functionalization.

Beyond serving as a standalone approach, the introduction of porous structures can be strategically integrated with other dielectric-reduction strategies to achieve synergistic enhancements. This combination leverages both the density reduction from porosity and the polarizability suppression from other modifications. For instance, porous structures can act as a host or scaffold for low-polarity fillers (e.g., fluorinated compounds or silica) or polymers, improving their dispersion and maximizing interfacial effects while simultaneously lowering the overall material density. Jiang et al. [53] study demonstrated that creating nanoporosity (30 vol%) in an epoxy matrix reduced the dielectric constant from 3.78 to 2.76. Subsequent hydrophobic treatment of the pore walls with hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) further decreased both the dielectric constant and loss tangent, illustrating how porosity management combined with surface chemistry modification can optimize dielectric performance. This aligns with the broader framework categorizing low-dielectric epoxy design into polarity reduction and density modulation, where porous architectures primarily address the latter but can be effectively coupled with strategies from the former category [54]. The key challenge in such combinatorial approaches lies in balancing the porosity characteristics (size, distribution, connectivity) with the integration of secondary modifiers to avoid detrimental effects on mechanical integrity and to control interfacial polarization, which can otherwise increase dielectric loss.

In summary, the introduction of porous structures into epoxy resins is a highly effective strategy for reducing both the dielectric constant and loss. The primary mechanisms involve a reduction in material density and a lower volumetric concentration of polarizable groups, complemented by the incorporation of air—a medium with a dielectric constant of ~1—which leads to a lower effective permittivity according to mixing rules. Additional benefits can include an increased specific surface area and enhanced thermal insulation properties. From a manufacturing perspective, many porous filler-based approaches offer comparatively straightforward processing requirements. However, this strategy is not without its challenges: a high volume fraction of pores or hollow fillers can lead to an excessive reduction in the composite’s viscosity and potentially undermine mechanical integrity. Furthermore, the extensive internal surface area of porous materials can exacerbate interfacial compatibility issues if not properly managed. Therefore, the precise engineering of pore content, size distribution, and morphology is paramount to achieving an optimal balance between low dielectric performance, adequate mechanical strength, and long-term reliability.

5. Summary of Dielectric Performance for Representative Strategies

The previous sections systematically covered four preparation strategies for low-dielectric epoxy resins: fluorination modification, low-polarity nanofiller doping, polymer blending, and porous/density reduction modification. We clarified how each strategy regulates polarization mechanisms and impacts dielectric properties. To clarify the “modification strategy-polarization mechanism-dielectric property-application scenario” correlation (and aid material design/process optimization), Table 2 summarizes these strategies’ core details, regulatory mechanisms, pros and cons.

Table 2.

Summary of dielectric properties of epoxy composites under different modification strategies.

To provide a concrete, quantitative overview of the dielectric performance achievable by the strategies discussed, Table 2 summarizes representative data from key studies cited in this review. This compilation highlights the range of dielectric constants (εr) and loss tangents (tan δ) attainable, along with the typical testing frequencies and filler loadings. It is important to note that these values represent optimized or reported peak performance under specific conditions; the actual performance in a given application will depend on detailed formulation, processing, and composite microstructure.

This review has systematically analyzed strategies to prepare low-dielectric epoxy resins by targeting polarizability and density. As quantitively compared in Table 2, each approach can successfully reduce the dielectric constant (εr) to below 3.0–4.0, with certain fluorinated or porous systems even achieving εr < 2.8. However, the accompanying loss tangent (tan δ), optimal loading levels, and impacts on other properties vary significantly, underscoring the critical trade-offs involved.

6. Conclusions

This review systematically outlines strategies for developing low-dielectric epoxy resins by modulating two fundamental material parameters: molecular polarizability and bulk density. The discussed methodologies are categorized into three primary approaches:

- Molecular Architecture Design: This involves tailoring the polymer network through the introduction of short side chains, flexible linkages, or bulky substituents. These modifications increase free volume, restrict chain mobility and intermolecular interactions, and dilute the concentration of polar groups, collectively leading to reduced polarizability.

- Incorporation of Low-Polarity Components: This strategy focuses on embedding inherently low-polarity atoms (e.g., fluorine) or chemical moieties into the epoxy matrix. These components induce steric constraints and possess low intrinsic polarizability, which synergistically suppresses dipole orientation and electronic polarization.

- Density Reduction through Porosity Engineering: This method entails compositing epoxy with porous or hollow micro-/nanofillers to decrease its effective density. The introduction of air-filled pores (k ≈ 1) directly lowers the composite’s permittivity according to effective medium theories, often concurrently reducing the dielectric loss and material cost.

In summary, the strategies of molecular architecture design, incorporation of low-polarity components, and density reduction through porosity engineering provide versatile pathways to tailor the polarization behavior and density of epoxy resins. The choice of strategy must be guided by the specific performance envelope required for the target application, which includes not only the dielectric constant and loss tangent at operational frequencies but also thermal stability, mechanical robustness, processability, and long-term reliability under environmental stressors. Future research should therefore prioritize the co-optimization of this multidimensional property set for well-defined application scenarios, moving beyond the reporting of isolated dielectric properties.

The ongoing deployment of 5G communication and the Internet of Things (IoT) necessitates advanced electronic materials that meet stringent high-frequency performance criteria. While traditional epoxy resin composites remain the workhorse for many electronic components, their inherent limitations in dielectric properties pose a significant challenge for next-generation applications. To bridge this performance gap, future research efforts should be directed along three pivotal pathways:

- Developing cost-effective, scalable low-dielectric epoxy resins compatible with industrial manufacturing processes.

- Conducting a systematic study on the influence of filler morphology and size on the dielectric properties of epoxy composites.

- Enhancing the dielectric stability of epoxy resins under high-temperature and variable-frequency conditions while simultaneously minimizing the dielectric constant and loss.

Addressing these scientific and technological challenges is therefore imperative. The concurrent development of high-performance, low-loss epoxy resins tailored for high-frequency operation, alongside the adoption of sustainable synthesis and processing routes, is poised to not only expand their application boundaries but also serve as a key enabler for the ongoing evolution of next-generation electronic technologies.

7. Research Prospects and Application Prospects

The development of low-dielectric epoxy resins is driven by the escalating demands of 5/6G communication, Internet of Things (IoT), automotive radar, and high-performance computing. To bridge the gap between laboratory research and industrial deployment, the following directions are recommended:

- Multi-scale Simulation-Guided Design: Computational modeling of polarization mechanisms, interface interactions, and pore morphology can accelerate the discovery of optimal compositions and structures, reducing experimental trial-and-error.

- Multifunctional Hybrid Systems: Future composites should aim to integrate low dielectric loss with high thermal conductivity, mechanical toughness, and environmental stability. For example, epoxy composites incorporating aligned boron nitride nanosheets within a porous matrix could achieve anisotropic dielectric and thermal management.

- Sustainable and Scalable Processing: Developing water-based, solvent-free, or UV-curable formulations with bio-derived modifiers (e.g., plant oil epoxies, lignin derivatives) will address environmental concerns while maintaining low dielectric performance.

- Frequency- and Temperature-Stable Materials: Systematic studies on the dielectric behavior under extreme conditions (e.g., −196 °C to 300 °C, up to THz frequencies) are essential for aerospace, quantum computing, and next-generation RF devices.

- Integration with Additive Manufacturing: 3D printing of low-dielectric epoxy composites enables the fabrication of geometrically complex, lightweight components for phased-array antennas, embedded passives, and high-density interconnections.

The realization of such advanced materials will not only enhance signal integrity, reduce power loss, and enable miniaturization in high-frequency circuits but also contribute to energy-efficient and sustainable electronics.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52303073, 52377002, 12202088).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Eyann, L.; Fatah Muhamed Mukhtar, M.A.; Saad, A.A.; Jaafar, M. Epoxy molding compounds for high-performance electronic packaging: A review on recent studies. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2025, 197, 109665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.Z.; Fu, Y.; Deb, H.; Hasan, M.K.; Dong, Y.; Shi, S. Polymer-based low dielectric constant and loss materials for high-speed communication network: Dielectric constants and challenges. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 200, 112543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Kobayashi, N.; Wang, C.; Takahashi, S.; Maekawa, S.; Masumoto, H. Novel Dielectric Nanogranular Materials with an Electrically Tunable Frequency Response. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2023, 9, 2201218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Y.; Kong, J.; Liu, T.; Gu, J. Polymer matrix wave-transparent composites: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 75, 225–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treichel, H. Low Dielectric Constant Materials. J. Electron. Mater. 2001, 30, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Deng, J.; Shi, J.; Jiang, Z.H.; Hong, W. An optically transparent, broadband, and highly efficient dual-mode Huygens’ transmit-array antenna based on a single-layer low-loss dielectric substrate. Mater. Des. 2025, 113982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Papageorgiou, D.; Zhang, H.; Yan, H.; Reece, M.; Yang, M.; Bilotti, E. Review of enhancing thermal conductivity in polymer-based dielectrics as passive components. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2025, 169, 102025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.L.; Li, X.; Park, S.J. Synthesis application of epoxy resins: A review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Liu, X.; Lou, Y. Materials and micro drilling of high frequency and high speed printed circuit board: A review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 100, 827–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaš, D.; Šíma, K.; Kadlec, P.; Polanský, R.; Soukup, R.; Řeboun, J.; Hamáček, A. FFF 3D printing in electronic applications: Dielectric and thermal properties of selected polymers. Polymers 2021, 13, 3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Cheng, W.; Zou, J.; Zhao, D. Progress on polymer composites with low dielectric constant and low dielectric loss for high-frequency signal transmission. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 774843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maex, K.; Baklanov, M.R.; Shamiryan, D.; Lacopi, F.; Brongersma, S.H.; Yanovitskaya, Z.S. Low dielectric constant materials for microelectronics. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 93, 8793–8841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Du, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Cao, Z.; Ye, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wei, J.; Wei, S.; Meng, X.; Song, L.; et al. Ultralow-Dielectric-Constant Atomic Layers of Amorphous Carbon Nitride Topologically Derived from MXene. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2301399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Lii, J.H.; Allinger, N.L. Molecular polarizabilities and induced dipole moments in molecular mechanics. J. Comput. Chem. 2000, 21, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, M. A physical interpretation of Cole–Cole equations and their ambiguous time constants for induced polarization models. Geophys. J. Int. 2025, 243, ggaf362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwakil, A.S.; Al-Ali, A.A.; Maundy, B.J. Extending the double-dispersion Cole–Cole, Cole–Davidson and Havriliak–Negami electrochemical impedance spectroscopy models. Eur. Biophys. J. 2021, 50, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardoň, Š.; Kúdelčík, J.; Janek, M.; Baran, A.; Kozáková, A.; Dérer, T. Halloysite nanotube enhanced polyurethane nanocomposites for advanced electroinsulating applications. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2025, 14, 20250248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.O.; St.Clair, A.K. Fundamental insight on developing low dielectric constant polyimides. Thin Solid Film. 1997, 308–309, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, S.; Nakamura, K. Syntheses properties of cured epoxy resins containing the perfluorobutenyloxy group, I. Epoxy resin cured with perfluorobutenyloxyphthalic anhydride. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Chem. Ed. 1984, 22, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Yang, S.; Ge, Z.; Chen, J.; Fan, L. Synthesis and properties of novel fluorinated epoxy resins based on 1,1-bis(4-glycidylesterphenyl)-1-(3′-trifluoromethylphenyl)-2,2,2-trifluoroethane. Eur. Polym. J. 2007, 43, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.R.; Jin, F.L.; Park, S.J.; Park, J.M. Study of new fluorine-containing epoxy resin for low dielectric constant. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2004, 180–181, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, T.; Jiang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhao, C. Preparation properties of novel fluorinated epoxy resins cured with 4-trifluoromethyl phenylbenzimidazole for application in electronic materials. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 100, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddle, B.; Baker-Jarvis, J.; Krupka, J. Complex permittivity measurements of common plastics over variable temperatures. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2003, 51, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumby, S.J.; Johnson, G.E.; Anderson, E.W. Dielectric properties of some PTFE-reinforced thermosetting resin composites. In Proceedings of the 19th Electrical Electronics Insulation Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 25–28 September 1989; pp. 263–267. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, H.; Xu, X.; Leng, K.; Zhang, S.; Han, Y.; Gao, J.; Yu, Q.; Wang, Z. A (4-fluorophenyl)(phenyl)phosphine oxide-modified epoxy resin with improved flame-retardancy, hydrophobicity, and dielectric properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 50792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Sheng, M.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, H.; Lin, X.; Pei, Y.; Zhang, X. Thermal and dielectric properties of epoxy-based composites filled with flake and whisker type hexagonal boron nitride materials. High Perform. Polym. 2020, 33, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, L.; Zuo, W.; Zhou, L.; Hu, X.; Bao, D. Effect of Terminal Groups on Thermomechanical and Dielectric Properties of Silica–Epoxy Composite Modified by Hyperbranched Polyester. Polymers 2021, 13, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Meng, G.; Wang, L.; Tian, L.; Chen, S.; Wu, G.; Kong, B.; Cheng, Y. Simultaneously enhanced dielectric properties and through-plane thermal conductivity of epoxy composites with alumina and boron nitride nanosheets. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, X. Effect of interface polarization on dielectric properties in nanocomposite compounded with epoxy and montmorillonite. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Solid Dielectrics (ICSD), Bologna, Italy, 30 June–4 July 2013; pp. 840–842. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidou, S.; Papaspyrides, C.D. A review on polymer–layered silicate nanocomposites. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2008, 33, 1119–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, R. Synthesis of novel phosphonium bromide-montmorillonite nanocompound and its performance in flame retardancy and dielectric properties of epoxy resins. Polym. Compos. 2021, 42, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, Z.; Yang, W.; He, S.; Bian, X. Preparation and Electrical Properties of Organic montmorillonite/Epoxy Composites. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 2nd International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), Beijing, China, 4–6 November 2018; pp. 625–628. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Q.; Huang, X.; Awais, M.; Paramane, A.; Ren, N. Investigation of Electrical and Thermal Properties of Epoxy Resin/Silicon Carbide Whisker Composites for Electronic Packaging Materials. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 12, 1109–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Bao, F.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Mu, K.; Wang, M.; Zhu, C.; Xu, J. Preparation of fluorinated polyimides with low dielectric constants and low dielectric losses by combining ester groups and triphenyl pyridine structures. Polym. Chem. 2024, 15, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.Y.; Park, S.-D.; Yoo, M.J.; Yang, H. Graft Architectured Poly(phenylene oxide)-Based Flexible Films with Superior Dielectric Properties for High-Frequency Communication Above 100 GHz. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 4708–4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.Y.; Ruan, W.H.; Zhang, M.Q.; Weihao, L. Improving the Dimensional Stability of Polyphenylene Oxide without Reducing Its Dielectric Properties for High-Frequency Communication Applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 7007–7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.J.; Hsu, S.W.; Chung, C.L.; Wang, C.S. Low dielectric epoxy resins from dicyclopentadiene-containing poly(phenylene oxide) novolac cured with dicyclopentadiene containing epoxy. React. Funct. Polym. 2008, 68, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang XLiu, L.; Zhang, H. Synthesis and properties of cured epoxy mixed resin systems modified by polyphenylene oxide for production of high-frequency copper clad laminates. Polym. Compos. 2018, 39, E2334–E2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Dai, C.; Jiang, S. Thioetherimide-Modified Cyanate Ester Resin with Better Molding Performance for Glass Fiber Reinforced Composites. Polymers 2019, 11, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Gu, A.; Liang, G.; Zhuo, D.; Yuan, L. Liquid crystalline epoxy resin modified cyanate ester for high performance electronic packaging. J. Polym. Res. 2011, 18, 1441–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.P.; Chuang, C.M. Thermal and Dielectric Properties of Cyanate Ester Cured Main Chain Rigid-Rod Epoxy Resin. Polymers 2021, 13, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Zhou, X.; Shen, M.; Wang, D.; Xu, X.; Shang, S.; Song, Z.; Song, J. Preparation of Hydrophobic Low-k Epoxy Resins with High Adhesion Using a Benzocyclobutene-Rosin Modifier. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 5973–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrubesh, L.W.; Keene, L.E.; Latorre, V.R. Dielectric properties of aerogels. J. Mater. Res. 1993, 8, 1736–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Boyd, I.W. Low dielectric constant porous silica films formed by photo-induced sol-gel processing. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2000, 3, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, K.; Zhu, B.; Yue, T.; Xie, C. Preparation and properties of hollow glass microsphere-filled epoxy-matrix composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wang, X. Preparation, microstructure, and properties of novel low-κ brominated epoxy/mesoporous silica composites. Eur. Polym. J. 2008, 44, 1414–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Y.; Kurimoto, M.; Kato, T.; Funabashi, T.; Suzuoki, Y. Specific gravity and dielectric permittivity characteristics of mesoporous-silica/epoxy composites. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Electrical Insulation and Dielectric Phenomena (CEIDP), Des Moines, IA, USA, 19–22 October 2014; pp. 760–763. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Phillips, O.; Keller, L.; Kohl, P.A. Porous Epoxy Film for Low Dielectric Constant Chip Substrates and Boards. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 68th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), San Diego, CA, USA, 29 May–1 June 2018; pp. 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Thirukumaran, P.; Parveen, A.S.; Sarojadevi, M. Synthesis of eugenol-based polybenzoxazine-POSS nanocomposites for low dielectric applications. Polym. Compos. 2015, 36, 1973–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Wang, L.; Lv, P.; Cui, Y.; Miao, J. Improved dielectric mechanical properties of silica/epoxy resin nanocomposites prepared with a novel organic–inorganic hybrid mesoporous silica: POSS–MPS. Mater. Lett. 2014, 129, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nagendiran, S.; Alagar, M.; Hamerton, I. Octasilsesquioxane-reinforced DGEBA and TGDDM epoxy nanocomposites: Characterization of thermal, dielectric and morphological properties. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 3345–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Z.; Chen, W.Y.; Yang, C.C.; Lin, C.L.; Chang, F.C. Novel epoxy nanocomposite of low Dk introduced fluorine-containing POSS structure. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2007, 45, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Keller, L.; Kohl, P.A. Low-Dielectric Constant Nanoporous Epoxy for Electronic Packaging. J. Electron. Packag. 2019, 142, 011006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Xu, Y.; Shen, M.; Xu, X.; Liu, H. Strategies for developing low dielectric epoxy materials. Eur. Polym. J. 2025, 240, 114355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.