Abstract

The impact and solidification of multiple molten droplets on a cold substrate critically influence the quality and performance of thermally sprayed coatings. We present a Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) model that couples fluid-solid interaction, wetting, heat transfer and phase change to simulate multi-droplet impact and freezing. The model is validated against benchmark cases, including the Young–Laplace relation, wetting dynamics, single-droplet impact and the Stefan solidification problem, showing good agreement. Using the validated model, we investigate two droplets—either centrally or off-centrally—impacting on a cold surface. Simulations reveal two distinct solidification patterns: convex pattern (CVP), which results in a mountain-like splat morphology, and concave pattern (CCP), which leads to a valley-like shape. The criterion for the two patterns is explored with two dimensionless numbers, the Reynolds number and the Stefan number . When , droplets tend to solidify in CVP; at higher Reynolds numbers , they tend to solidify in CCP. The transition between the two patterns is primarily governed by , with exerting a secondary influence. For example, when droplets have and , they tend to solidify in a convex pattern, whereas at and , they tend to solidify in a concave pattern. Also, the solidification state of the first droplet greatly influences the subsequent spreading and solidification of the second droplet. A parametric study on CCP cases with varying vertical and horizontal offsets shows that larger vertical offsets accelerate solidification and reduce the maximum spreading factor. For small vertical distances, the solidification time increases with horizontal offset by more than 29%; for large vertical distances the change is minor. These results clarify how droplet interactions govern coating morphology and thermal evolution during thermal spraying.

1. Introduction

Droplet solidification is a very common phenomenon in both natural and industrial settings and plays an important role in processes such as thermal spray [1], inkjet printing [2], welding [3], and additive manufacturing [4]. In thermal spray, molten droplets spread and rapidly freeze upon impact with a cold substrate, forming splats that determine coating microstructure and performance. The same physics also underlies icing phenomena on aircraft components, where supercooled droplets can pose safety risks [5].

Accurate prediction of splat formation requires resolving large free-surface deformations together with moving solidification fronts. Experiments typically rely on high-speed imaging and particle image velocimetry to capture surface morphologies and internal flow during freezing [6,7]. While experiments provide insights into the physical process, they are often challenging to conduct and observe, with results limited to a narrow parameter space.

Numerical simulation offers a complementary approach to studying droplet impact and solidification, enabling detailed analysis of fluid dynamics and thermal evolution under controlled conditions. Mesh-based interface-capturing approaches such as the volume-of-fluid (VOF) and level-set (LS) methods have been widely used to study freezing and rebound behaviors, often coupled with enthalpy-porosity or nucleation models to capture phase change.

Moussa Tembely et al. [8] developed a coupled VOF method and nucleation theory to simulate the impact and freezing of a supercooled droplet on a superhydrophobic surface, revealing how the solidification time evolves with the maximum spreading diameter of the droplet. Zhang Xuan et al. [9] used the VOF method to simulate the freezing process of droplets on an ultra-cold surface and discovered the scaling law between the maximum spreading factor of droplets and the effective Reynolds number. Li Wen et al. [10] combined the level-set method with an enthalpy–porosity model to investigate the rebound dynamics of supercooled water droplets on a cold superhydrophobic surface and discovered four different modes.

The lattice Boltzmann method (LBM), a mesoscopic approach based on kinetic theory, has been applied to multiphase flows with complex boundaries. Zhiyuan Ma et al. [11,12] used LBM to study droplet solidification on cold substrates, highlighting how surface roughness affects solidification morphology and dynamics. Yiqing Guo et al. [13] developed an LBM model that accounts for the solid–liquid density ratio influence on solidification behavior.

VOF schemes can exhibit numerical interface diffusion when handling complex, topology-changing interfaces, necessitating careful interface reconstruction to limit errors. Level-set methods handle topological changes more naturally but can suffer from mass non-conservation. The lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) offers advantages for complex boundaries at mesoscopic scales, though it is typically more computationally demanding.

Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) is a mesh-free, Lagrangian particle method originally developed for astrophysics [14,15] and subsequently adapted for fluid dynamics. Its Lagrangian nature makes SPH well suited to flows with large deformations and evolving free surfaces, so it has been widely applied to multiphase problems such as droplet impact and solidification.

Cui et al. [16] used SPH to study the solidification dynamics of supercooled large droplets on cold substrates. Lee et al. [17] simulated YSZ droplet impact in thermal spraying, highlighting the roles of impact velocity and substrate temperature on splat morphology. Subedi et al. [18] employed SPH with solidification and heat transfer models to show how a modified Biot number and thermal diffusivity affect freezing behavior. Bobzin et al. [19] demonstrated how substrate preheating and roughness alter splat shape and solidification in thermal-spray contexts.

However, most prior studies focus on single-droplet impact and freezing; interactions among multiple droplets—common in practical thermal spraying—remain relatively underexplored.

Here, an SPH model is developed to simulate droplet impact and solidification on cold substrates. The model is validated against benchmark problems, such as Young–Laplace, wetting dynamics, single-droplet impact and the Stefan problem. Then applied to study the solidification dynamics of multiple impacting droplets.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the numerical model, including SPH formulations, the fluid-solid interaction and wetting models, and the heat transfer and solidification treatments. Section 3 presents model validation against benchmark cases. Section 4 applies the model to simulate multiple-droplet impacts and analyzes the effects of droplet interactions. Section 5 concludes with the main findings and outlines directions for future work.

2. Numerical Simulation Model

This section presents the governing SPH equations, solidification model, solid boundary treatment, surface tension model, time integration and implementation on GPU.

2.1. SPH Equations

The SPH method is a mesh-free Lagrangian particle method.

SPH approximates field quantities using a smoothing (kernel) function that replaces the Dirac function. By the reproducing property of the kernel, any scalar field may be written in integral form as

where and h correspond to the position vector and the smoothing length, is the domain where the function is nonzero, and is the variable of integration.

Replacing the integral by a summation over particles (the particle approximation) yields

where denotes the value of A at particle i, and denote the mass and density for the neighbor particle j around the particle i, respectively, and .

Let A represent the particle density; then,

This can be used as the continuity equation [20].

In this paper, the smoothing length for particle i is calculated as follows:

where is the spatial dimension of the simulation, and is the smoothing length coefficient.

The hyperbolic kernel function is chosen, which could make the particles distribute more uniformly, and avoid the particle tensile instability [21].

where , and is the normalization factor, equal to in 2D and in 3D.

The momentum equation is written as

where is the material derivative as , with local derivative and convection terms. The symbols , , , and denote velocity, gravity, surface tension, and shear viscosity for particle i, respectively. The pressure is given by a weakly compressible equation of state as

where is the reference density, which is set to the initial density, and c is the numerical speed of sound, which is much larger than the typical fluid velocity to be simulated, for example, ten times it. Note that the numerical speed of sound is not necessarily equal to the physical speed of sound.

The gradient of pressure is discretized using a symmetric scheme for particle i,

The viscous stress is discretized as

The energy equation, which considers the effects of thermal capacity, heat convection enduced by particle movement and heat conduction, is given by

where is the temperature, is the thermal conductivity, and is the internal energy per unit mass of particle i.

where is the specific heat capacity at constant volume. As in ref. [22], differences between solid and fluid particles in heat transfer modeling are neglected.

Thus, Equation (10) is discretized as

2.2. Solidification Model

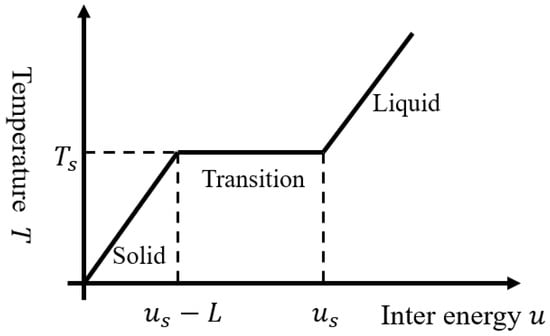

Figure 1 shows the relationship between the particle temperature and its internal energy during the solidification process, where the temperature remains constant but the internal energy continues decreasing. Neglecting the difference between the solid and liquid properties as well as the interfacial resistance, particles are fully solidified when they gradually lose all the latent heat of fusion L given by the system. Note that such an assumption does not consider the voids caused by changes in liquid and solid density. Also, it might overestimate the process of solidification, as there may exist a certain degree of supercooling at the liquid–solid solidification interface.

Figure 1.

The relation between temperature T and internal energy u during droplet solidification.

Although this method is simple, it is effective. Xiangda Cui also applied it to simulate the freezing process of supercooled large droplets [16]. Zhang enwei et al. used the same method to simulate droplet solidification on cold plates [23].

2.3. Solid Boundary

Ghost particles are placed outside the boundary. Their temperature is fixed to the user-specified value, while pressure and velocity are extrapolated from nearby fluid particles. For a ghost particle i, its velocity is updated from surrounding fluid particles as

and the pressure is determined by

2.4. Surface Tension Model

In the van der Waals equation of state, the negative pressure term corresponds to attractive intermolecular forces that contribute to surface tension [24,25]. Inspired by this, the negative pressure term i is introduced to model the surface tension term in Equation (6) in the simulation.

where a is an attraction coefficient.

Similarly to the discretization of pressure, the SPH form of the surface tension is

where the superscript H indicates that the smoothing radius of this kernel function is twice that of the others, which makes the computation more stable [25].

To simulate the contact angle, a color function is used [24]. It is initialized as

Then, only the color of the ghost particles will be updated, as follows:

where K is a coefficient corresponding to the attraction between solid and fluid, and is the critical value related to the contact angle.

Finally, the surface tension is updated in the following form:

2.5. Time Integration

The leap-frog scheme is used for time integration. It requires two stages per update. First, particle quantities at are calculated by

After updating and other physical quantities at , the method proceeds to the next stage,

For stability,

2.6. Implementation on GPU

In SPH, neighbor searches and particle interactions dominate the runtime, yet the computations for different particles are largely identical and independent since each particle interacts only with its neighbors. This parallelism allows the data to be distributed across many threads that execute the same operations concurrently, accelerating the simulation.

Graphics processing units (GPUs) are now standard in high-performance scientific computing because they efficiently handle massively parallel workloads. Leveraging NVIDIA’s Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA) harnesses thousands of GPU cores, enabling large-scale simulations to run efficiently on general-purpose workstations.

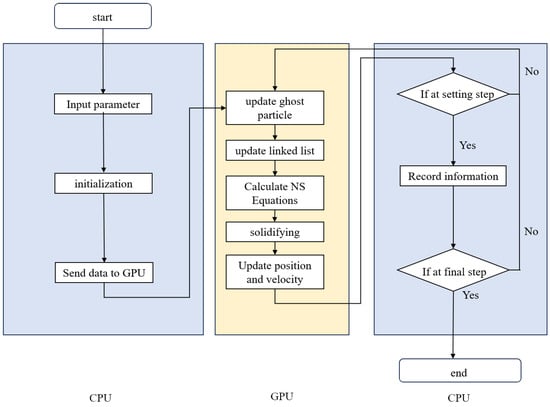

The SPH solver and the linked-list neighbor search are implemented in CUDA Fortran. The flowchart of the GPU-accelerated SPH method is shown in Figure 2. Generally, the procedure has 10 steps: (1) input parameters; (2) initialize on the CPU; (3) send data to the GPU; (4) update ghost particles; (5) search and update the linked list; (6) calculate the Navier–Stokes equations; (7) determine whether a particle has solidified; (8) update position and velocity; (9) if at an output/sampling step, send data back to the CPU and record information, otherwise repeat steps (4)–(8); and (10) finalize and output results.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the GPU-accelerated SPH method.

3. Model Validation

In this section, the numerical model is verified through several classic benchmark cases.

3.1. Surface Tension

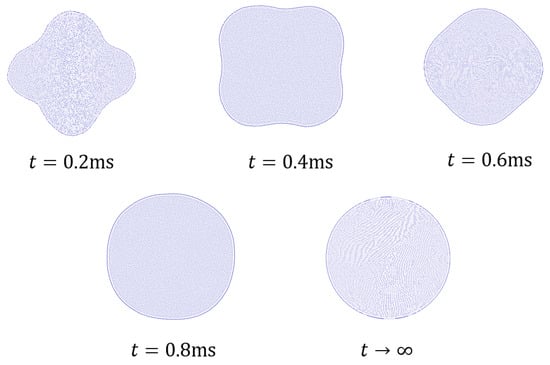

A square droplet is simulated to validate the surface tension model.

Surface tension drives the interface toward minimal surface area; in two dimensions, a circle yields the minimum perimeter for a fixed area. As shown in Figure 3, the droplet oscillates under surface tension and progressively relaxes to a circular shape, reaching a quasi-static state.

Figure 3.

The process of a square-shaped droplet gradually becoming round.

Surface tension induces a pressure jump across the droplet interface, described by the Young–Laplace relation,

where is the interior–exterior pressure difference, and are the principal curvatures of the interface at equilibrium, and is the surface tension. For a 3D spherical droplet, both principal curvatures equal , so

Following reference [26], the pressure jump inside the droplet can be computed as

where d is the spatial dimension, V the droplet volume, is the displacement from particle i to particle j, and .

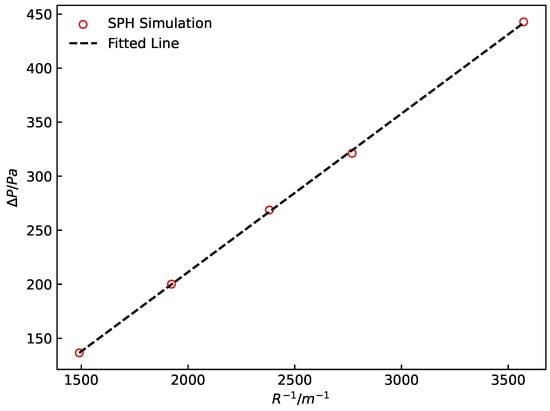

Droplets with various radii are simulated, and the pressure jump is computed using Equation (25). The results shown in Figure 4 are in good agreement with the Young–Laplace Equation (24) with a coefficient of determination using and , consistent with the surface tension of water at room temperature.

Figure 4.

The total pressure inside the droplet as a linear function of radius.

3.2. Wettability

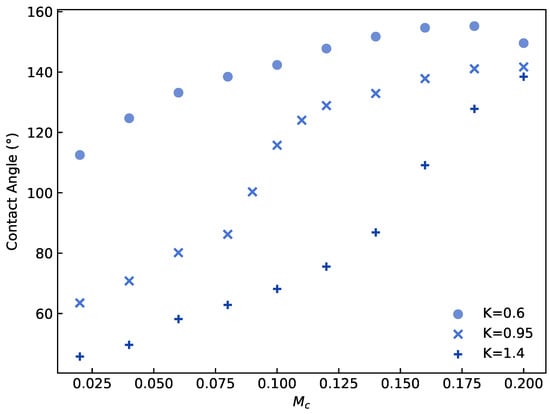

A circular droplet is placed on the bottom wall to validate the contact angle model. The droplet evolves to a quasi-static state with a well-defined contact angle.

As shown in Figure 5, for different K values, the contact angle varies with in Equation (18). For , the minimum contact angle exceeds , and the wall remains hydrophobic as varies from 0 to 0.2, reflecting weaker solid-fluid attraction than fluid-fluid attraction. For and , the wall’s hydrophilicity increases with , and the tunable range of contact angle at exceeds that at .

Figure 5.

Contact angle for different K and .

In all subsequent simulations, and are used.

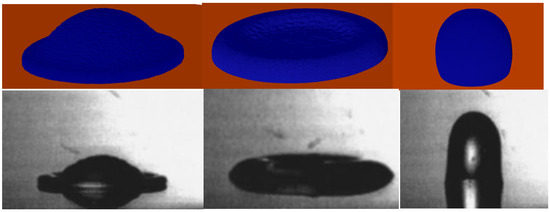

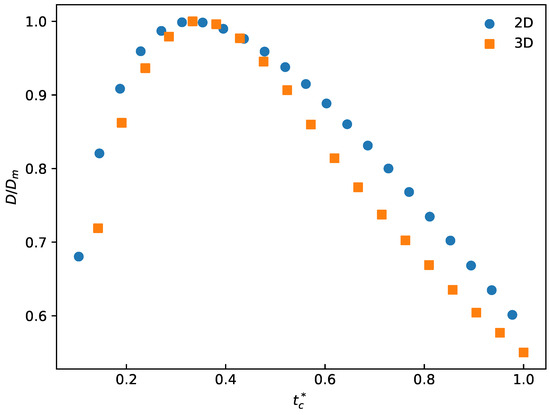

3.3. Droplet Collision

The SPH solver is used to simulate the dynamics of a droplet impacting a wall; heat transfer is neglected in this test. The numerical results are compared with experiments to assess model accuracy.

Figure 6 shows a 2.8 mm-diameter droplet impacting the wall at 1.56 m/s. Because the wall and droplet have the same temperature, no solidification occurs during impact. The simulation agrees well with the experimental data of Kim et al. [27].

Figure 6.

Comparison of simulation results with experimental data.

Differences between 2D and 3D simulations are analyzed. In Figure 7, is defined as , where is the contact time of the droplet with the wall. is the maximum spreading diameter of the droplet after impact. Compared with 3D simulations, 2D simulations show the same trend but somehow differ in absolute values; the maximum difference is about 10.2%. Due to limitations of computational resources, 2D simulations are used in this paper. It should be noted that 2D simulations can qualitatively capture the spreading and solidification behavior of droplets. However, 2D simulation might overestimate the droplet spreading ratio due to its less spreading degrees of freedom.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the droplet’s maximum radius in 2D and 3D.

3.4. Stefan Problem

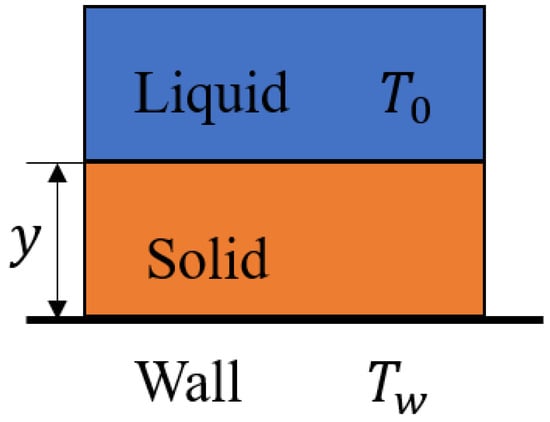

The heat transfer and solidification model is validated against the classical Stefan problem. Following reference [28], temperature is non-dimensionalized with respect to the critical temperature.

The simulation setup is shown in Figure 8: the bottom solid boundary is maintained at a constant temperature of , periodic boundary conditions are applied to the left and right boundaries, and the top boundary is open. Initially, all particles except ghost particles are fluid, with their temperature set to . Under heat conduction, particles solidify once they have released their latent heat L and their temperature falls below . The computational domain has length l and width h.

Figure 8.

Simulation settings for the Stefan problem.

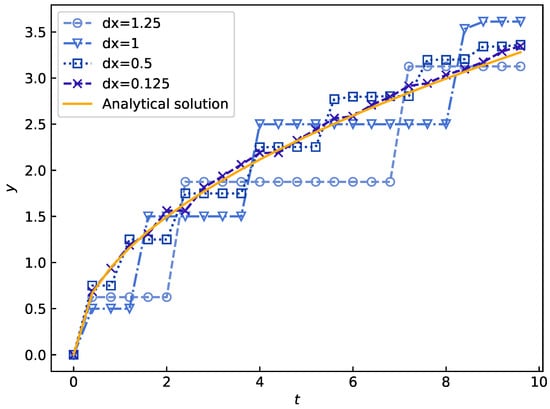

The same Stefan problem is simulated with different particle spacings. As shown in Figure 9, the numerical results converge toward the analytical solution as particle resolution increases. For the case with an initial SPH particle spacing of , the root-mean-square error is 0.04526.

Figure 9.

Analytical solution and SPH simulations of the solidification front position with varying particle spacings for the Stefan problem.

4. Results

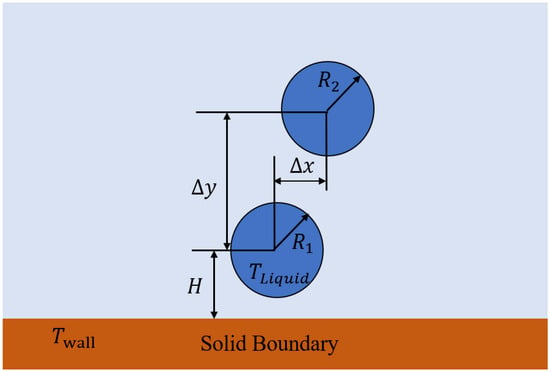

The numerical setup is illustrated in Figure 10. Two droplets, modeled in 2D, are placed in a sufficiently large simulation domain with vertical and horizontal separations of and , respectively. A low-temperature solid wall is located at the bottom.

Figure 10.

Numerical simulation setup.

In all simulations, the Reynolds number is defined as

where denotes the droplet impact velocity, R is the droplet radius, is the fluid density, and is the shear viscosity of the fluid. In Section 4.1 and Section 4.2, two-droplet collision and solidification process is distinguished as convex pattern (CVP) or concave pattern (CCP), depending on their final splat morphologies. Here, we use two typical Reynolds numbers of Re = 9.9 or Re = 19.8 for CVP and CCP, respectively, with the same Stefan number of . The Stefan number is defined as

where is the fluid specific heat capacity, is the temperature difference between the droplet and the wall, and L is the latent heat of the fluid.

4.1. Convex Pattern

Reynolds number is set to , vertical distance , and horizontal distance .

In Figure 11, denotes the dimensionless time, where . Figure 11 presents the collision and solidification process for the CVP. After solidification, the droplet exhibits a convex, mountain-like morphology.

Figure 11.

Convex pattern (CVP) of two-droplet collision and solidification.

Before collision, the leading droplet completes spreading and begins to recoil. Upon impact by the trailing droplet, deformation initiates near the peak of the leading droplet. Due to the asymmetric initial offset, only the right side of the deformed droplet initially contacts the substrate. Driven by surface tension, the left deforming region retracts toward the peak, whereas the right region solidifies more rapidly owing to a larger temperature difference with the substrate.

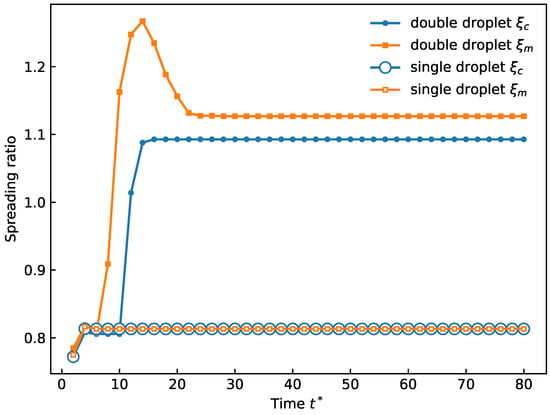

As shown in Figure 11, two kinds of spreading diameters are defined: the maximum diameter of the merged droplet , and the contact diameter , which is the diameter of the region in contact with the substrate. Thus, two kinds of spreading ratios are defined:

where is the initial diameter of a single droplet.

Figure 12 shows Two-droplet spreading ratios in CVP compared with a single droplet. Before collision, the spreading ratios of the two droplets coincide with that of a single droplet. At impact, the maximum spreading ratio rises sharply as deformation develops. The contact spreading ratio remains unchanged initially because the bottom region solidifies first. Once the deformed region meets the substrate, increases abruptly. Subsequent recoil of the upper portion reduces before complete solidification. After the bottom region solidifies, both and remain nearly constant.

Figure 12.

Two-droplet spreading ratios in CVP compared with a single droplet.

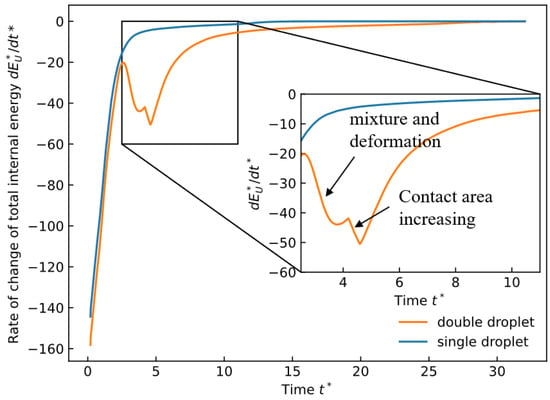

On the other hand, the temporal evolution of the internal energy change rate is investigated and compared with the single-droplet case. Figure 13 plots the dimensionless internal energy change rate for both the two-droplet and single-droplet cases. is defined as , where is the total internal energy at any time and is the initial total internal energy.

Figure 13.

Internal energy change rate of CVP compared with a single droplet.

According to Fourier’s law of heat conduction and Gauss’s theorem, the internal energy change rate of the droplet can be expressed as

where A is the area of the droplet surface in contact with the substrate. The negative sign indicates that the droplet releases heat to the substrate.

Prior to the collision of the second droplet, the internal energy of the two-droplet system is consistent with that of the single droplet. Upon the second collision, the internal energy change rate surges abruptly because of mixing, which elevates the droplet temperature and the temperature difference with the substrate; consequently, the temperature gradient is augmented, which boosts the heat release rate. As solidification advances and the droplet temperature declines, the temperature gradient lessens and the internal energy change rate correspondingly decreases. When liquid deformation continues, the contact area A keeps expanding, leading to a transient increase in the internal energy change rate, but it then diminishes again as solidification continues and the temperature difference reduces.

4.2. Concave Pattern

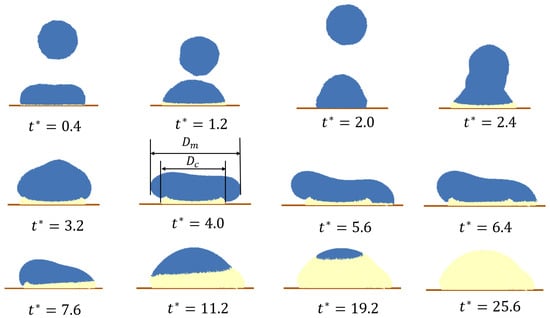

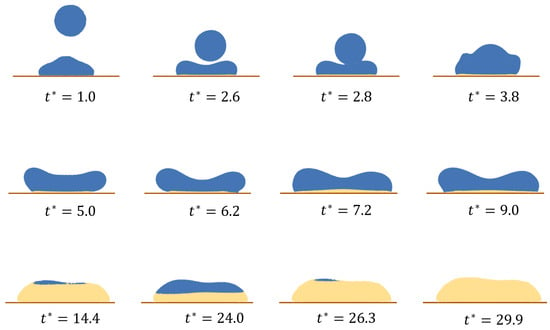

In this case, the Reynolds number is set to , and the remaining parameters match those of the convex pattern. This pattern arises when the leading droplet spreads before collision. After solidification, the morphology is concave, resembling a valley with two flanking peaks of different heights.

Figure 14 depicts the collision and solidification process for the concave pattern. Before the collision of the trailing droplet, the leading droplet of the two-particle case spreads in a manner similar to that of a single droplet case. Upon being impacted by the trailing droplet, significant deformation and mixing take place. Partial solidification at the bottom of the leading droplet restricts the expansion of the contact area until the deformed region makes contact with the substrate. As the collision is off-center, the deformation is asymmetric. In this instance, despite the trailing droplet being offset only by 0.25R to the right, the final morphology of the merged mass shifts significantly to the right, showing a greater height and a larger radius at the left than the right. At the end of the solidification process, the highest pool on the left eventually solidifies due to its relatively long distance from the cold substrate.

Figure 14.

Concave pattern (CCP) of two-droplet collision and solidification.

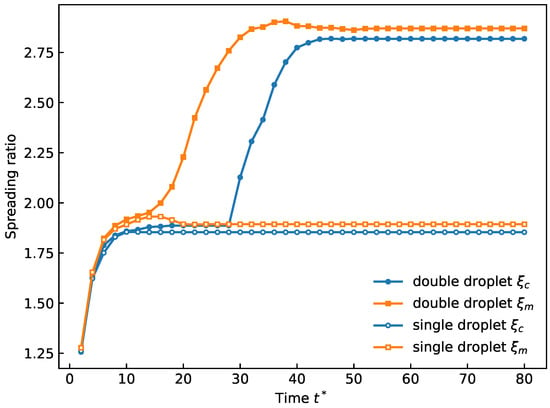

As illustrated in Figure 15, during the initial stage the spreading behavior under continuous droplet impact is similar to that of a single droplet impact. The maximum spreading ratio increases substantially because of severe collision-induced deformation. In contrast, the contact spreading ratio increases only after the deformed portion touches the substrate, as the bottom layer solidifies earlier. Because the upper region does not solidify completely, shrinkage can occur, slightly reducing the maximum spreading ratio, while the contact spreading ratio remains approximately constant after reaching its final value.

Figure 15.

Two-droplet spreading ratios in CCP compared with a single droplet.

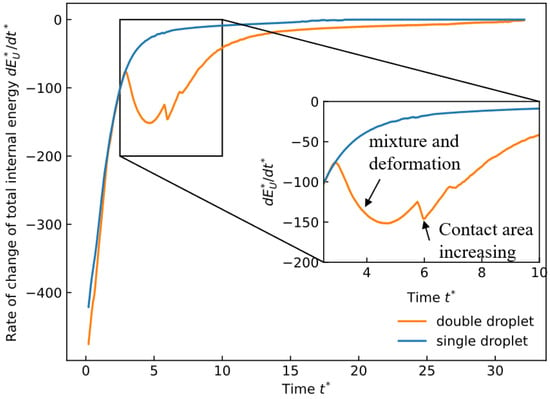

In Figure 16, a negative value indicates heat release from the droplet. When the two droplets do not collide, the internal energy change rate follows single-droplet solidification behavior. Once the trailing droplet collides with the leading droplet, deformation accompanies heat transfer between the droplets. Because the trailing droplet is hotter, mixing raises the mixed-droplet temperature, increasing the temperature difference with the substrate, steepening the temperature gradient , and enhancing the internal energy change rate. As temperature decreases, the rate diminishes. When the deformed region later contacts the substrate, the contact area increases and the rate rises again. After the bottom part solidifies and the contact area stabilizes, the rate decreases as the temperature difference diminishes.

Figure 16.

Internal energy change rate of CCP compared with a single droplet.

4.3. Category of CVP and CCP

A concise table that summarizes the key differences between CVP and CCP is presented in Table 1. the comparison between these two patterns becomes clear when examining the characteristics of CVP and CCP. CCP exhibits a higher Reynolds number, which is an important dimensionless quantity in fluid dynamics used to predict flow patterns in different flow situations. Furthermore, CCP shows a valley-like splat morphology, while CVP displays a mountain-like shape. In addition, CCP has a larger final maximum spreading ratio, indicating that it spreads more extensively in the end compared with CVP. Moreover, CCP demonstrates stronger mixing capabilities, suggesting that the internal components involved in CCP are more thoroughly blended than those in CVP.

Table 1.

Key differences between CVP and CCP regimes.

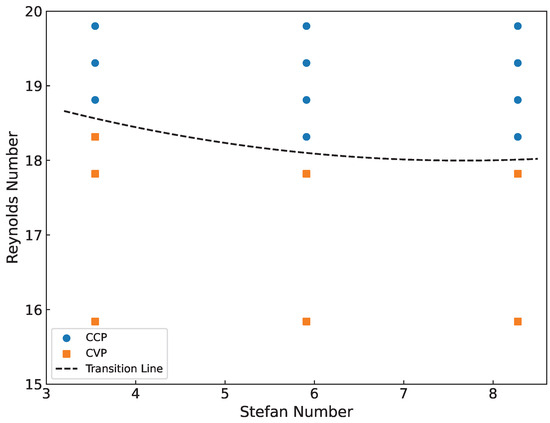

Figure 17 presents a detailed category that illustrates the various patterns of droplet solidification under different conditions. At relatively low Reynolds numbers (), solidification predominantly occurs in the CVP mode. As the Reynolds number increases (), the preferred mode shifts to CCP.

Figure 17.

Category of droplet solidification patterns.

Relative to the pronounced effect of the Reynolds number on the solidification mode, the Stefan number has a much weaker influence. Low Stefan numbers lead to slower solidification speed and greater retraction, making CVP more likely than at high Stefan numbers. This slightly reduces the critical Reynolds number for the transition between CCP and CVP. Nevertheless, it should be noted the effect is minor and does not materially alter droplet solidification behavior.

4.4. Effect of and

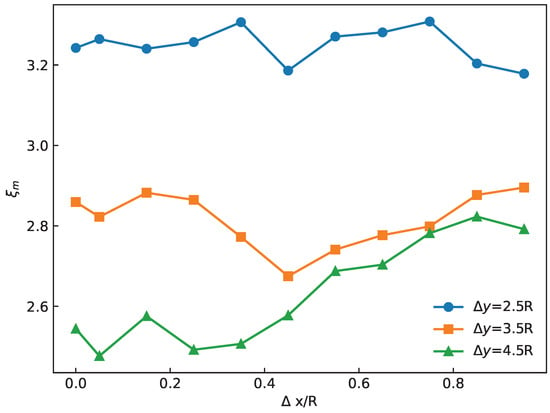

The effects of horizontal distance and vertical distance between two droplets on spreading and solidification in CCP are investigated, since mixing is stronger in CCP than in CVP.

Figure 18 shows how varies with horizontal distance at different vertical distances . When , exceeds that of the other two cases for all and remains nearly constant. For , is smaller at but becomes larger at . For , increases with , reaching about 9.75% above the center collision case.

Figure 18.

Maximum spreading ratio versus horizontal offset at different vertical offsets .

Theoretically, a greater drop height increases gravitational potential energy and thus kinetic energy at impact, which promotes spreading. However, a larger vertical distance also allows the leading droplet more time to solidify before collision, leaving less liquid available to spread at impact. Thus, spreading and solidification exhibit a competitive relationship. This explains why the case yields the smallest spreading ratio in our simulations.

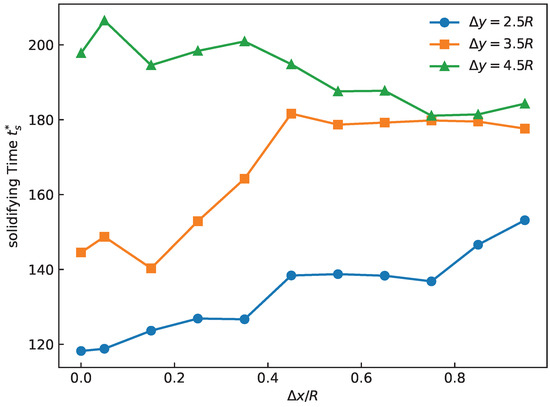

Figure 19 shows that the dimensionless total solidification time varies with horizontal distance at different vertical distances . The is defined as , where is the dimensional total solidification time of the two droplets, and .

Figure 19.

Total solidification time versus horizontal distance at different vertical distances .

When , the total solidification time is the shortest and increases with ; in this case, the maximum solidification time exceeds the minimum by about 29.55%. For , the total solidification time remains nearly constant for , with a maximum about 29.45% larger than the minimum. For , the total solidification time is the longest because the trailing droplet takes longer to fall from a higher position; in this case, the solidification time decreases with because larger yields a larger contact area and faster solidification.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a SPH model is developed to simulate the dynamics of multiple droplets impacting and solidifying on a cold surface.

The simulations revealed that droplet interactions significantly influence solidification patterns, highlighting the complex competitive relationship between thermal and fluid-dynamic effects.

Two distinct solidification patterns are observed. For and , droplets tend to solidify in a convex pattern; for and , they tend to solidify in a concave pattern. When , droplets tend to solidify in CVP; at higher Reynolds numbers (), they tend to solidify in CCP. An increase in the Stefan number slightly decreases the critical Reynolds number for the CCP-CVP transition, but the effect is minor.

Relative to single-droplet impact and solidification, the spreading and heat transfer behavior of two droplets is strongly affected by mixing and spreading, exhibiting multi-stage characteristics. When the two droplets are horizontally offset, the trailing droplet’s spreading substantially influences the overall spreading factor. The mixing effect is more pronounced in the concave pattern and competes with solidification, thereby altering the spreading factor under different vertical offsets. In our simulations, at shorter vertical distances, the solidification time increases with horizontal offset by more than 29%, whereas at longer vertical distances the solidification time decreases slightly. These findings provide insights into droplet solidification behavior in applications such as thermal spraying.

This study encompasses several limitations that probably need attention in future research: (1) The material density change and shrinkage during solidification are neglected, thus requiring an analysis of their influence on coating porosity. (2) Some complex non-equilibrium phenomena during solidification are neglected for simplicity, such as supercooling and nucleation. (3) The effect of wettability on spreading and solidification demands further investigation. (4) Substrate melting and oxidation might be incorporated. (5) Three-dimensional simulation is needed when computational efficiency and storage are improved. These aspects will be addressed in our future research to improve the model accuracy and result reliability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.X.; methodology, H.X. and Q.W.; software, L.Y. and Q.W.; validation, L.Y.; formal analysis, L.Y.; investigation, L.Y.; resources, L.Y.; data curation, L.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Y.; writing—review and editing, H.X.; visualization, L.Y.; supervision, H.X.; project administration, H.X.; funding acquisition, H.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11972321).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Qichao Wang was employed by the company Zhefu Holding Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Qadir, D.; Sharif, R.; Nasir, R.; Awad, A.; Mannan, H.A. A review on coatings through thermal spraying. Chem. Pap. 2024, 78, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.A.; Lee, D.G.; Lee, B.Y.; Hur, S. Classifications and Applications of Inkjet Printing Technology: A Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 140079–140102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, Z.; Liu, H.; Babkin, A.; Lee, B.; Chang, Y. Research progress on transition behavior control of welding droplets. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 120, 1571–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Liu, J.; Deng, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y. A review on droplet-based 3D printing with piezoelectric micro-jet device. Smart Mater. Struct. 2024, 33, 073003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetteh, E.; Loth, E.; Neuteboom, M.O.; Fisher, J. In-Flight Gas Turbine Engine Icing: Review. AIAA J. 2022, 60, 5610–5632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Wang, F.; Tao, Q.; Chen, L.; Rubinstein, S.M.; Deng, D. Frozen patterns of impacted droplets: From conical tips to toroidal shapes. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2020, 5, 081601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerstrom, E.; Ljung, A.L. Internal flow in freezing and non-freezing water droplets at freezing temperatures. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 234, 126100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tembely, M.; Attarzadeh, R.; Dolatabadi, A. On the numerical modeling of supercooled micro-droplet impact and freezing on superhydrophobic surfaces. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 127, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, K.; Zhu, Z.; Fang, W.Z.; Zhu, F.Q.; Yang, C. Droplet impact and freezing dynamics on ultra-cold surfaces: A scaling analysis of central-concave pattern. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 239, 122135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, J.; Tian, L.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, N. Numerical investigation on rebound dynamics of supercooled water droplet on cold superhydrophobic surface. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 239, 122007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Xiong, W.; Cheng, P. 3D Lattice Boltzmann simulations for water droplet’s impact and transition from central-pointy icing pattern to central-concave icing pattern on supercooled surfaces. Part I: Smooth surfaces. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 171, 121097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Xiong, W.; Cheng, P. 3D Lattice Boltzmann simulations for water droplet’s impact and transition from central-pointy icing pattern to central-concave icing pattern on supercooled surfaces. Part II: Rough surfaces. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 172, 121153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Wu, X.; Min, J. Lattice Boltzmann simulation of droplet solidification processes with different solid-to-liquid density ratios. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2024, 198, 108881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucy, L. Numerical Approach to Testing the Fission Hypothesis. Astron. J. 1977, 82, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gingold, R.; Monaghan, J. Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics—Theory and Application to Non-Spherical Stars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1977, 181, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Habashi, W.G. A dendritic freezing model for in-flight supercooled large droplets impingement and solidification. Comput. Fluids 2023, 254, 105778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Subedi, K.K.; Huang, G.W.; Lee, J.; Kong, S.C. Numerical Investigation of YSZ Droplet Impact on a Heated Wall for Thermal Spray Application. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2022, 31, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, K.K.; Kong, S.C. Particle-based approach for modeling phase change and drop/wall impact at thermal spray conditions. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2023, 165, 104472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobzin, K.; Heinemann, H.; Jasutyn, K.; Jeske, S.R.; Bender, J.; Warkentin, S.; Mokrov, O.; Sharma, R.; Reisgen, U. Modeling the Droplet Impact on the Substrate with Surface Preparation in Thermal Spraying with SPH. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2023, 32, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigalotti, L.D.G.; Troconis, J.; Sira, E.; Pena-Polo, F.; Klapp, J. Diffuse-interface modeling of liquid-vapor coexistence in equilibrium drops using smoothed particle hydrodynamics. Phys. Rev. E 2014, 90, 013021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, M.; Peng, S. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics modeling of viscous liquid drop without tensile instability. Comput. Fluids 2014, 92, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Hoenig, S.; Chen, C.H.; Neti, S.; Romero, C.; Vermaak, N. Efficient modeling of phase change material solidification with multidimensional fins. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 115, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Liu, H.; Li, H. Model of moving solid-liquid phase change interface of a droplet following impact on a cold plate. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 2024, 165, 105809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.B.; Zhang, C.Y.; Yu, Z.S. Multiphase SPH modeling of water boiling on hydrophilic and hydrophobic surfaces. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 130, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, S.; Posch, H. Liquid drops and surface tension with smoothed particle applied mechanics. Phys. Rev. E 2000, 62, 4968–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigorina, E.; Kordilla, J.; Tartakovsky, A.M. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics study of the roughness effect on contact angle and droplet flow. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 96, 033115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y.; Chun, J.-H. The recoiling of liquid droplets upon collision with solid surfaces. Phys. Fluids 2001, 13, 643–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Wang, Q.; Yuan, L.; Liang, J.; Lin, J. Modeling and Experiments of Droplet Evaporation with Micro or Nano Particles in Coffee Ring or Coffee Splat. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.