Abstract

In this study, a triisopropanolamine (TIPA)-modified polycarboxylate cement grinding aid was synthesized via a free radical polymerization reaction, and its effects on cement properties were investigated. The synthesized grinding aid was evaluated through cement grinding experiments, by comparing cement samples with and without the additive. The influences on particle size distribution, specific surface area, residue content, setting behavior, flowability, and mechanical strength were systematically evaluated. The results demonstrated that the modified polycarboxylate cement grinding aid significantly refined size distribution of particles, enlarged the specific surface area to 4900 cm2/g (27.9% increase), decreased 45 μm residue content to 0.8%, accelerated setting, and improved the flowability of the cement paste. Strength tests of cement mortar indicated that the additive improved both early and late compressive strength, with 3d and 28d strengths increasing by 6.5 MPa and 5.7 MPa, respectively, compared to the blank sample, providing strong theoretical support for its potential use in industrial cement production.

1. Introduction

Cement is an indispensable component of the modern construction industry, and its production scale and technological level directly influence the quality and efficiency of national infrastructure development. Although China’s cement production has declined slightly in recent years, it still remains the largest producer globally, with significant challenges such as high energy and resource consumption and severe environmental pollution [1,2,3]. Among the various production stages, grinding is a critical and energy-intensive step, accounting for 30%–40% of total energy consumption [4,5,6]. Therefore, improving grinding efficiency and reducing energy consumption while maintaining or enhancing cement performance are key challenges.

Since the 1930s, grinding aids have been widely applied in cement production as efficient chemical additives. By adsorbing onto particle surfaces, they reduce agglomeration, enhance grinding efficiency, optimize particle distribution, and improve powder flowability [7,8].

According to differences in chemical composition and mechanism of action, cement grinding aids can be divided into various types, each with different technical characteristics and application limitations, as shown in Table 1. Conventional grinding aids generally consist of low-molecular-weight compounds like, organic grinding acids, inorganic grinding aids, or composite grinding aids [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Organic grinding aids rely on polar groups (-OH, -NH2) adsorbing onto particle surfaces to reduce surface energy. They prevent agglomeration through steric hindrance or electrostatic repulsion. However, they are not only relatively expensive but also have limited contribution to the later strength development of some cements. Among them, triethanolamine (TEA) is known to increase the degree of the hydration of C3A, promote the formation of ettringite (Aft), and hinder the hydration of C3S. Its effect strongly depends on dosage: at 0.02% it acts as an accelerator, at 0.5% as a retarder, and at 1% as an accelerator again [18]. Triisopropanolamine (TIPA), however, exhibits poor compatibility with other admixtures, often resulting in reduced workability of concrete [19]. Inorganic grinding aids mainly improve grinding efficiency by introducing ions (such as Na+, Cl−, SO42−) to alter particle surface properties and the slurry environment. However, they have a single function, only serving as grinding aids, and their effectiveness is inferior to that of organic grinding aids. In addition, the introduced chloride salts (Cl−) can corrode steel bars, so they need to be strictly controlled. Composite grinding aids, on the other hand, are mixtures where each component performs its own role: organic components provide adsorption and dispersion, while inorganic components offer ion activation or lattice interference. However, there may be antagonism between components, requiring a large number of experiments to optimize the ratio and dosage. Polycarboxylate-based grinding aids have recently drawn attention due to their tunable molecular structure, high dispersing efficiency, and environmental compatibility [20,21,22]. Their molecular design allows introduction of hydroxyl, carboxyl, amino, and ether groups to improve dispersion, reduce agglomeration, and enhance hydration activity. As a result, both grinding efficiency and cement strength can be improved simultaneously.

Table 1.

Types, core components, mechanisms and key performance characteristics of cement grinding aid.

Although polycarboxylate-based grinding aids have attracted attention due to their structural adjustability, existing research has mostly focused on the regulation of groups such as carboxyl and ether groups. There is less research on introducing TIPA into the polycarboxylate molecular chain to synergistically improve grinding efficiency and hydration activity. Additionally, the problem of poor compatibility of TIPA when used alone with other admixtures has not been effectively solved through molecular structure modification. This study addresses this gap by designing and synthesizing TIPA-modified polycarboxylate-based grinding aids to enhance their polarity, exploring the correlation between their structure and performance, and providing a new approach for developing efficient and environmentally friendly cement grinding aids.

2. Materials and Experimental Methods

2.1. Materials

Triisopropanolamine (TIPA), acryloyl chloride, acrylic acid (AA), isopentenol polyoxyethylene ether (TPEG-2400), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), diethyl ether, ascorbic acid (VC), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), triethylamine, 3-mercaptopropionic acid, sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and gypsum were obtained from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The composition of the Portland cement clinker was analyzed using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) (AXIOS, PANalytical, Eindhoven, Netherlands), and the results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of cement clinker (%).

2.2. Synthesis Process

2.2.1. Synthesis of Acryloyl Chloride-Modified Triisopropanolamine Derivative

Triisopropanolamine (20 g) was dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 80 mL), after which 10 mL of triethylamine was introduced as an acid-binding agent. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere to remove residual moisture. Then, a separate solution of 15 mL acryloyl chloride in DMF (50 mL) was added dropwise to the TIPA–DMF solution. Following the addition, the ice bath was withdrawn, and the reaction proceeded for 6 h at ambient temperature with continuous stirring.

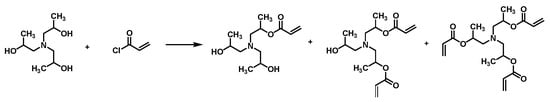

Next, the mixture was filtered to eliminate the triethylamine salt by-products, and the filtrate was subjected to reduced-pressure distillation at 65 °C for 2 h to remove most of the DMF solvent. The resulting solution was then slowly added to an ice-cooled diethyl ether solution under stirring. Following thorough mixing, the organic phase was decanted, and the precipitate was repeatedly washed with diethyl ether (three times). The final product was dried in a vacuum oven to obtain the acryloyl chloride-modified triisopropanolamine derivative (ACTA), the schematic structure of which is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the preparation of the acryloyl chloride-modified triisopropanolamine derivative.

2.2.2. Synthesis of the Modified Polycarboxylate Cement Grinding Aid

A typical synthesis procedure was as follows:

Acrylic acid (4.3 g) and the modified triisopropanolamine intermediate (1.8 g) were dissolved in 10 mL of deionized water to obtain Solution A. Separately, ascorbic acid (6.32 g) and 3-mercaptopropionic acid (14.74 g) were dissolved in 20 mL of deionized water to obtain Solution B.

TPEG-2400 (36 g) was introduced into a three-necked flask with 40 mL of deionized water and stirred until fully dissolved. Hydrogen peroxide (42.1 g, H2O2) was then added to the solution. Under continuous stirring, Solutions A and B were successively added dropwise to the flask over 3 h and 3.5 h, respectively. Upon completion of the additions, the mixture was kept at constant temperature and stirred for an additional 1 h to complete the reaction.

The reaction mixture was then tuned to pH 7 using a 40 wt% NaOH aqueous solution, yielding the target product, designated as grinding aid 1 (GA1). By varying the molar ratios of acrylic acid (AA), acryloyl chloride-modified triisopropanolamine derivative (ACTA), and TPEG as 3.5:1:1, 3:1.5:1, and 2.5:2:1, three additional products were synthesized and denoted as GA2, GA3, and GA4, respectively.

2.3. Experimental Methods

2.3.1. FTIR Spectra

FTIR spectra were obtained on a Nicolet 67 (Thermo Nicolet, Madison, WI, USA) spectrometer. About 1 mg of sample was thoroughly blended with 100 mg of spectroscopic-grade KBr, and the uniform mixture was pressed into a transparent pellet prior to spectral acquisition.

2.3.2. NMR Spectra

The 1H NMR spectrum of liquid hydrogen was measured using a 400 MHz superconducting nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer (AVANCE NEO 400, Bruker, Rheinstetten, Germany), with DMSO-d6 as the solvent.

2.3.3. GPC

The molecular weight of hyperbranched GA1-GA4 was measured by GPC apparatus (LC-20AD, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

2.3.4. Cement Grinding Experiment

A control mixture containing 95 wt% clinker and 5 wt% gypsum was prepared for the grinding experiments. Before grinding, clinker and gypsum were both crushed to a particle size less than 6–7 mm. Cement grinding experiments were conducted in the laboratory using a φ500 mm × 500 mm ball mill manufactured by Shanghai Jianyuan Instrument Factory (Shanghai, China). Steel balls served as the grinding medium with a rotational speed of 180 rpm and a grinding time of 30 min.

For each grinding test, a total feed of 5 kg was used, and the grinding duration was fixed at 30 min for all samples. The resulting cement samples included the blank cement (C-Blank) and those prepared with the four grinding aids, denoted as C-GA1, C-GA2, C-GA3, and C-GA4. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

2.3.5. Cement Characterization Methods

The fineness of cement was determined according to GB/T 1345-2005 [23], and the specific surface area was measured following GB/T 8074-2008 [24]. The standard consistency water requirement and setting times were tested according to GB/T 1346-2024 [25], whereas the flowability of cement mortar was evaluated in compliance with GB/T 2419-2005 [26]. Mechanical properties, including flexural and compressive strengths, were tested after curing 3 and 28 days based on GB/T 17671-2021 [27]. Particle size distribution was characterized using a Microtrac S3500 laser particle size analyzer (Microtrac Inc., Montgomeryville, PA, USA; 780 nm laser).

2.3.6. Hydration Heat Measurement

TAM AIR-08 multi-channel isothermal calorimeter (Waters Corporation, New Castle, DE, USA) was conducted to investigate the hydration heat of cement with GA. The test was conducted under controlled environmental conditions of (20 ± 1) °C and a relative humidity of not less than 90%. 1 g cement and deionized water (w/c = 0.5) were mixed and poured into a specific container under stirring. The heat release curve of cement hydration was calculated by computer.

2.3.7. SEM

The morphology of cement particles was investigated via field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JSM-7610F, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

3. Results and Discussion

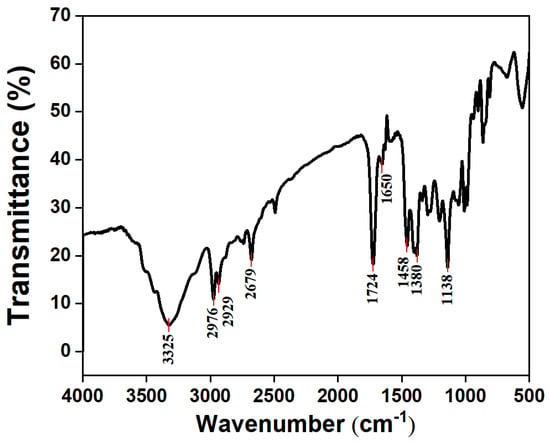

The FTIR spectrum of the acryloyl chloride-modified triisopropanolamine derivative (Figure 2) exhibits characteristic absorption bands at 3325 cm−1, corresponding to O–H stretching, and at 2976 cm−1 and 2929 cm−1, which are ascribed to the asymmetric stretching vibrations of CH3 and CH2 groups within the isopropyl chain. A strong peak at 1724 cm−1 represents the C=O vibration, while the band at 1650 cm−1 is assigned to C=C stretching. Additional absorptions at 1458 cm−1 and 1380 cm−1 arise from CH2 bending and CH3 symmetric deformation, respectively. The peak at 1138 cm−1 attributes to the C–O vibration.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of the acryloyl chloride-modified triisopropanolamine derivative.

The simultaneous presence of pronounced C=O and C=C bands confirms the formation of an ester bond between acryloyl chloride and triisopropanolamine, demonstrating the successful incorporation of the vinyl group into the triisopropanolamine framework [1,10]. These spectral features collectively substantiate the successful synthesis of the acryloyl chloride-modified triisopropanolamine derivative.

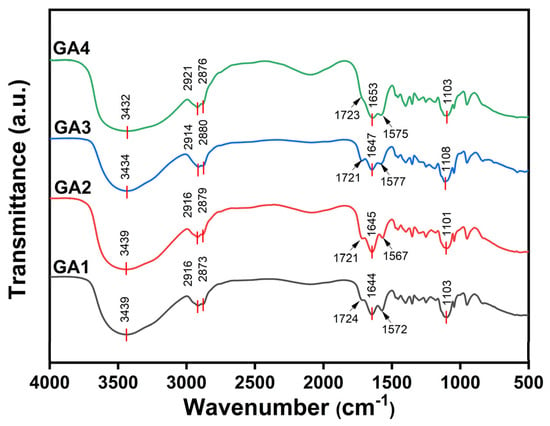

Figure 3 presents the FTIR spectra of the four synthesized grinding aids (GA1–GA4). The main spectral features are comparable among the samples. Taking GA1 as an example: the absorption peak at 3432 cm−1 corresponds to O–H stretching, indicating the presence of residual hydroxyl groups derived from the triisopropanolamine intermediate. The peaks at 2916 cm−1 and 2873 cm−1 arise from asymmetric stretching vibrations of CH3 and CH2 groups, typical of alkyl chains. The peak at 1724 cm−1 is ascribed to C=O stretching vibration, and the band at 1644 cm−1 corresponds to the C=C stretching mode, suggesting that some double bonds remain unreacted.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of the synthesized grinding aids GA1–GA4.

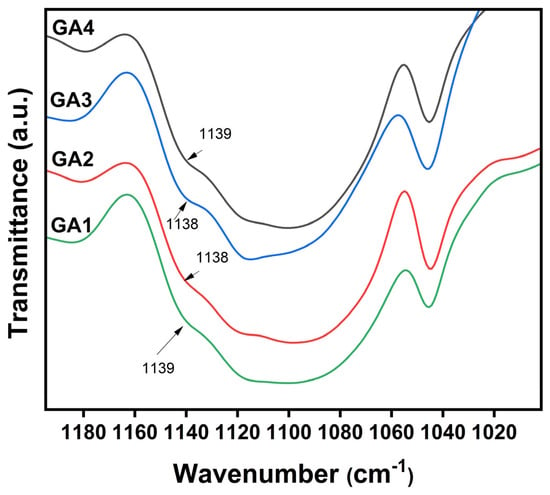

The band observed at 1572 cm−1 is characteristic of the asymmetric stretching of the carboxylate group (COO−), while the prominent absorption at 1103 cm−1 is ascribed to C–O–C vibrations associated with the polyether segments of TPEG. In the magnified spectra (Figure 4, 1000–1200 cm−1 region), the weaker C–O stretching peak near 1138 cm−1 suggests partial overlap with the strong ether absorption of TPEG, indicating successful incorporation of ester and ether functionalities within the polymer backbone.

Figure 4.

Enlarged FTIR spectra of GA1–GA4 in the 1000–1200 cm−1 region.

The presence of key characteristic peaks corresponding to C=O (ester), C–O–C (ether), and residual O–H groups confirms the successful synthesis of the target polycarboxylate-based grinding aids.

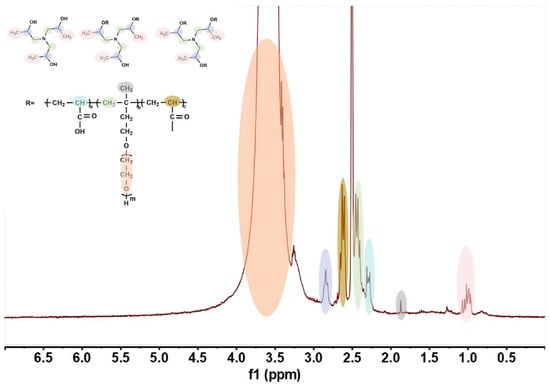

The structural characteristics of the synthesized triisopropanolamine-modified polycarboxylate cement grinding aid were further confirmed by 1H NMR, with GA3 taken as an example for explanation. As shown in Figure 5, δ = 0.97–1.07 ppm, the peak is assigned to the methyl group (-CH(CH3)2) of the isopropyl group in the ACTA unit; δ = 1.87 ppm, the peak is assigned to the methyl group (-C-CH3) of the main chain of TPEG; δ = 2.26–2.31 ppm, the peak is assigned to the α-CH of the acrylic acid unit (-CH(COOH)-); δ = 2.39–2.45 ppm, the peak is assigned to the -CH2- of the TPEG unit (connecting the main chain and PEO) and the N-CH2- of the ACTA unit; δ = 2.60–2.65 ppm, the peak is assigned to the α-CH of ACTA (-CH-COO-); δ = 2.84 ppm, the peak is assigned to the methylene group CH of the isopropyl group in ACTA (-CH(CH3)2); δ = 3.33 ppm, the peak is assigned to the residual water peak; δ = 3.50–3.60 ppm, the peak is assigned to the PEO chain (-OCH2CH2-)n of TPEG.

Figure 5.

1H NMR spectroscopy of GA3.

The molecular weight and molecular weight distribution of GA1–GA4 were determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC). The monomer ratio, molecular weight, and polydispersity index of GA1–GA4 are shown in Table 3. GA 1–GA 4 are all polymers, with actual GPC measured values ranging from 15,000 to 21,000. The molecular weight distribution is relatively narrow, between 1.29 and 1.39. This is due to the addition of chain transfer agents in the polymerization reaction, which enhances the chain transfer effect and narrows the molecular weight distribution. In addition, the branched structure of ACTA and the macromonomer characteristics of TPEG make the polymer chain length tend to be uniform. The reason why the molecular weight of GA4 is lower than that of GA3 may be due to the different radical polymerization reactivity ratios of AA, ACTA, and TPEG. The double bond activity of AA is higher than that of ACTA. In GA4, the proportion of AA decreases while the proportion of ACTA increases, leading to a reduction in the ratio of active monomers in the polymerization system. This weakens the driving force for chain growth reactions, making it difficult for molecular chains to extend sufficiently, and ultimately resulting in a lower degree of polymerization compared to GA3. ACTA molecules contain isopropyl branches, which create significant steric hindrance. Excess ACTA during polymerization hinders the migration and collision of free radicals, increasing the probability of chain termination reactions and limiting molecular chain length. In contrast, GA3 has a moderate proportion of ACTA, allowing the steric hindrance effect to be controlled, thus enabling more complete chain growth.

Table 3.

The ratio of monomer units, molecular weight and polydispersity index of grinding aids GA1–GA4.

The cement clinker, gypsum, and synthesized grinding aids were co-ground for 30 min, and the results were compared with those of the blank cement sample (without any additive) to evaluate the effects of the grinding aids on cement fineness and size distribution of particle. The selected dosage of the grinding aid (0.3%) aligned with our previous research on concrete admixtures, thereby facilitating direct comparison of related formulations [28]. As shown in Table 4, the residue on the 45 μm sieve significantly decreased after the addition of grinding aids, indicating a substantial reduction in coarse particles. Among the samples, the cement containing grinding aid GA-3 exhibited the lowest residue (0.8%), confirming that the additive effectively reduced the content of larger particles. Furthermore, the specific surface area of the cement is markedly increased with the addition of grinding aids, demonstrating their ability to enhance the degree of grinding. The specific surface area of GA-3 sample reached 4900 cm2·g−1, representing a 27.9% increase compared with the blank cement. These results collectively demonstrate that the synthesized polycarboxylate-based grinding aids significantly improve the grinding efficiency of cement.

Table 4.

Effect of different grinding aids on cement fineness.

The size distributions of the five cement samples are summarized in Table 5. Since particle size distribution reflects the proportion of particles across different size ranges, it provides a more accurate measure of grinding efficiency than fineness or specific surface area alone. Previous studies have shown that particles in the 3–32 μm range have the most significant influence on cement hydration and performance [29,30]. As seen in Table 5, the proportion of fine particles (3–32 μm) in C-GA3 is the highest among all samples—36.1% higher than that of the blank cement—while its average particle size decreases by 12.76 μm. In contrast, the blank cement contains the largest proportion of coarse particles (>45 μm), whereas C-GA3 exhibits a substantial reduction in this fraction. These findings demonstrate that GA3 exhibits the highest grinding efficiency, producing finer and more uniformly distributed cement particles compared with other formulations.

Table 5.

Particle size distribution of cement powders.

By combining cement grinding fineness and particle size distribution, it can be known that GA3 performs best. Although GA4 has an increased ACTA content, its performance shows a deteriorating trend. This difference may be due to the synergistic or imbalanced effects of the ratio of functional groups and chain structure of the grinding aids. In the GA3 structure, carboxyl groups chelate with Ca2+ on the cement surface to inhibit particle agglomeration, while the hydrophilic nature of the carboxyl groups ensures the dispersibility of the polymer in the cement paste. Excessive hydrophilicity of the molecular chain can lead to adsorption saturation, which weakens the steric hindrance effect. The hydroxyl groups on the ACTA in its structure form hydrogen bonds with active sites on the cement mineral surface, enhancing the polymer’s adsorption to particles. Meanwhile, ACTA can also promote hydration. However, GA4, due to an excess of ACTA, has a reduced number of carboxyl groups in the molecular chain, resulting in insufficient chelation ability with Ca2+ on the cement particle surface and weakened electrostatic repulsion. Therefore, even though the adsorption effect of the ACTA group is enhanced, it cannot compensate for the weakened dispersing effect of the carboxylic acid. In addition, an increased amount of ACTA reduces the overall hydrophilicity of the polymer. The ACTA molecule has many polar groups; excessive addition leads to a sharp increase in the branching degree of the polymer main chain, intensify molecular chain entanglement, thereby reducing the dispersing effect.

The setting time, water demand, and flowability of the cement pastes were evaluated, and the relevant results are given in Table 6. As shown, all cements containing grinding aids (C-GA1–C-GA4) exhibited shorter initial and final setting times than the blank cement, confirming that the additives promoted cement hydration. The C-GA3 sample showed the most pronounced effect, reducing the initial and final setting times by 33 and 46 min, respectively. This behavior is attributed to the alkanolamine functionalities in the grinding aid, which enhance the cement minerals’ reactivity and accelerate hydration reactions, thus expediting the setting process.

Table 6.

Effect of grinding aids on the physical properties of cement.

The water requirement for standard consistency of the GA-containing cements was slightly lower than that of the blank sample, suggesting that the synthesized modified polycarboxylate grinding aids effectively adsorbed onto cement particle surfaces. This adsorption enhances particle dispersion and introduces steric hindrance effects, which prevent particle agglomeration [31].

Furthermore, the fluidity of all cements containing grinding aids was higher than that of the blank cement. Although the addition of grinding aids increased the specific surface area and shortened setting time—factors that might otherwise raise water demand—the polycarboxylate-based GAs exhibited excellent dispersibility. By adsorbing on the cement surface and inducing electrostatic repulsion between particles, they minimized aggregation. The balance between these effects led to a notable improvement in mortar flowability, demonstrating that the modified grinding aids contribute positively to the workability of cement systems.

The flexural and compressive strength results of the five cement mortars after 3-day and 28-day curing periods are presented in Table 7. As shown, all cements containing grinding aids (C-GA1–C-GA4) exhibited higher strengths than the blank cement at both ages. Among them, C-GA3 demonstrated the most significant improvement, with 3-day compressive strength increased by 6.5 MPa and the 28-day compressive strength increased by 5.7 MPa compared with the blank sample.

Table 7.

Effect of grinding aids on the mechanical properties of cement mortar.

This enhancement is considered to be attributed to the larger specific surface area of the GA3-modified cement, which facilitates more efficient contact between cement particles and water. The increased surface reactivity accelerates the hydration process, resulting in faster formation of hydration products and improved early strength development. Consequently, the modified polycarboxylate grinding aid GA3 not only enhances grinding efficiency but also contributes to both early and long-term mechanical performance of cement.

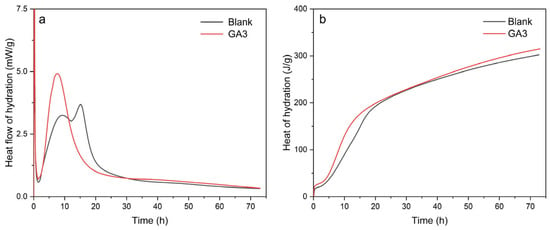

Cement hydration is a complex physicochemical process, and the energy changes during this process can be intuitively presented through hydration heat detection. Given the close relationship between the rate of hydration heat release and hydration kinetics, this indicator can directly reveal the time nodes, heat release intensity, and total heat of hydration peaks (induction period, acceleration period). These thermodynamic parameters are closely related to the setting time and early strength development of cement. Based on this, this study measured the heat flow and heat of hydration using a TAM-Air isothermal calorimeter. As shown in Figure 6a, it can be seen that blank cement exhibits a distinct exothermic peak during the initial hydration stage (approximately 0–10 h), followed by a gradual decline, indicating that the hydration reaction is more intense initially and then becomes milder. In contrast, cement with the grinding aid GA3 shows a more pronounced exothermic peak and a higher peak value during the initial stage (approximately 0–10 h), suggesting that GA3 accelerates the early hydration reaction of cement. Subsequently, the rate of decline is similar to that of blank cement, but the overall rate remains slightly higher. As shown in Figure 6b, with the passage of time, the cumulative hydration heat of blank cement gradually increases and eventually stabilizes. This indicates that the hydration reaction of cement is a continuous process, but the reaction rate gradually slows down over time. Meanwhile, cement with the grinding aid GA3 shows faster growth in cumulative hydration heat during the initial stage (approximately 0–20 h), demonstrating that GA3 promotes the early hydration reaction. Thereafter, the trend of cumulative hydration heat growth is similar to that of blank cement, but the total cumulative amount is slightly higher. Based on the test results of hydration heat, the addition of grinding aid GA3 significantly accelerates the early hydration reaction of cement, as evidenced by the significant increase in heat release rate and cumulative hydration heat during the initial stage. However, as time progresses, the hydration reaction trends of both become consistent, indicating that the grinding aid mainly affects the early hydration process.

Figure 6.

Heat flow and heat release of cement hydration. (a) Hydration heat release rate curve. (b) Hydration heat release curve.

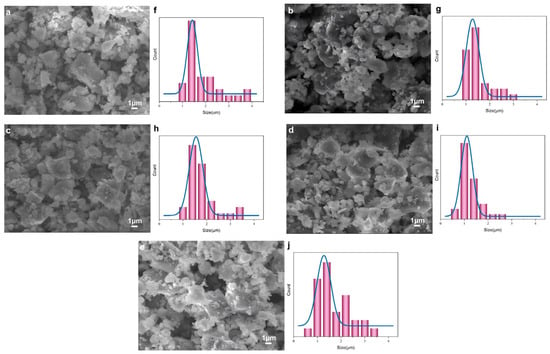

Figure 7 indicates the SEM results of cement samples (a–e) and their corresponding particle size distribution histograms (f–j). The blank cement without the modified polycarboxylate grinding aid exhibits large and irregularly distributed particles in its SEM image (a), and its particle size distribution (f) shows a relatively broad range—collectively indicating poor dispersion. In contrast, the cements incorporating the modified grinding aids (C-GA1–C-GA4, corresponding to b-e, respectively) display finer and more uniformly distributed particles in their SEM images; meanwhile, their particle size distributions (g–j) present narrower peaks, which reflects better size uniformity. Among them, C-GA3 presents the most homogeneous and refined particle morphology in SEM image (e), and its particle size distribution (j) shows the most concentrated peak, confirming the optimal dispersion effect. This improvement is mainly attributed to the carboxyl (-COOH) groups in the modified polycarboxylate molecules, which can chelate with Ca2+ ions on the surface of cement particles to form a stable double electric layer structure. The resulting electrostatic repulsion effectively inhibits particle agglomeration. Meanwhile, the long polyether chains of TPEG provide an additional steric hindrance effect, further enhancing particle dispersion [20]. These combined mechanisms confirm that all synthesized grinding aids improved the size distribution of particle and uniformity of cement, with GA3 showing the most pronounced effect.

Figure 7.

SEM images and corresponding particle size distribution histograms of cement samples: (a,f) blank cement; (b,g) C-GA1; (c,h) C-GA2; (d,i) C-GA3; (e,j) C-GA4.

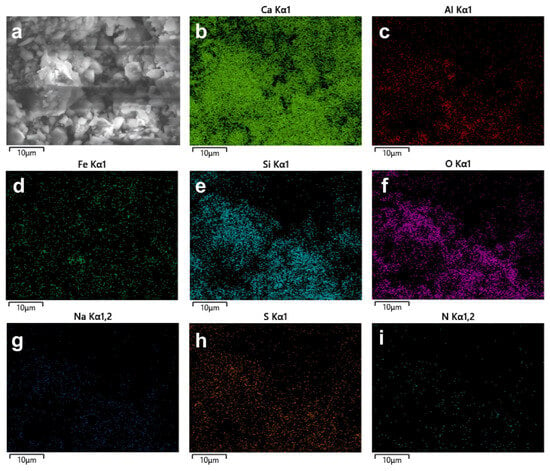

To further investigate the effect of C-GA3 on the distribution of cement chemical phases, EDS area scan analysis was conducted (Figure 8b–i). The results show that the distribution of major elements such as Ca, Si, and Al exhibits high uniformity. The elemental signals are continuously distributed throughout the field of view, with no obvious element segregation or enrichment clusters observed. This uniform elemental distribution characteristic indicates that the C-GA3 grinding aid promotes the dispersion and mixing of different mineral phases at the microscale through its surface activity. Combining SEM and mapping results, it can be known that C-GA3 molecules adsorb on the particle surface, reducing the particle surface energy. This not only prevents the re-agglomeration of fine powders (thus obtaining finer particles) but also makes the components distribute more uniformly in space, which is conducive to the uniform progress of subsequent hydration reactions.

Figure 8.

SEM images of (a) C-GA3, (b) Ca elemental mapping images of C-GA3, (c) Al elemental mapping images of C-GA3, (d) Fe elemental mapping images of C-GA3, (e) Si elemental mapping images of C-GA3, (f) O elemental mapping images of C-GA3, (g) Na elemental mapping images of C-GA3, (h) S elemental mapping images of C-GA3 and (i) N elemental mapping images of C-GA3.

4. Conclusions

Based on the results and discussions above, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- (1)

- A modified polycarboxylate grinding aid was successfully synthesized via a free-radical polymerization reaction, and its performance in cement grinding was systematically investigated.

- (2)

- The addition of modified polycarboxylate grinding aid significantly improved the grinding efficiency of cement. Compared with the blank cement, the optimal sample GA-3 (with AA:ACTA:TPEG molar ratio of 3:1.5:1) reduced the residue on the 45 μm sieve to 0.8%, increased the specific surface area by 27.9% (reaching 4900 cm2/g), and increased the proportion of particles in the beneficial size range of 3–32 μm by 36.1%.

- (3)

- The grinding aid optimized the particle size distribution of cement. SEM and particle size analysis showed finer and more uniform particles. It also improved cement paste properties, with a slight reduction in water requirement for standard consistency, increased fluidity, and significantly shortened setting times (GA-3 reduced initial and final setting times by 33 and 46 min, respectively).

- (4)

- Mechanical property tests showed that all cement samples containing grinding aids exhibited higher strengths at both 3-day and 28-day ages compared to the blank sample. GA-3 performed best, with 3-day and 28-day compressive strengths increased by 6.5 MPa and 5.7 MPa, respectively, confirming the dual functions of this grinding aid in both grinding efficiency improvement and strength enhancement.

- (5)

- In this study, triisopropanolamine was modified with acryloyl chloride and introduced into the polycarboxylate molecular chain, successfully resolving the poor compatibility issue of TIPA when used alone, while synergistically enhancing grinding efficiency and hydration activity. This provides theoretical and technical support for developing high-performance and environmentally friendly cement grinding aids.

This study is basic research conducted under laboratory conditions, aiming to verify the fundamental principles and potential application value of new compounds, and to provide theoretical support for industrial applications. However, the synthesis process of this grinding aid is complex and requires strict process control, which may restrict large-scale production. The next key task is to carry out pilot-scale amplification and factory site testing. Under the premise of ensuring stable product performance, process amplification issues need to be addressed to promote the transformation of laboratory achievements into industrial applications.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, Y.Y. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, L.W., Y.L. and L.Z.; supervision, H.W. and C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the science and technology development project of Jilin province, China (No. 20230508059RC).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical support provided by Jilin Xipu Cement Grinding Aid Co., Ltd., & Baotou Steel North-West Pioneer Construction Co., Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

Yu Liu was employed by Jilin Xipu Cement Grinding Aid Co., Ltd. and was employed by Jilin Xipu Cement Grinding Aid Co., Ltd. Liping Zhang was employed byBaotou Steel North-West Pioneer Construction Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TIPA | triisopropanolamine |

| TEA | triethanolamine |

| Aft | ettringite |

| AA | acrylic acid |

| TPEG | isopentenol polyoxyethylene |

| DMF | N,N-dimethylformamide |

| VC | ascorbic acid |

| H2O2 | hydrogen peroxide |

| NaOH | sodium hydroxide |

| GA | grinding aid |

| GPC | gel permeation chromatography |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectra |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

References

- Zhang, T.; Gao, J.; Hu, J. Preparation of polymer-based cement grinding aid and their performance on grindability. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 75, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Y.; Kobya, V.; Mardani, A. Evaluation of fresh state, rheological properties, and compressive strength performance of cementitious system with grinding aids. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, S.; Ishak, K. A study of different grinding aids for low-energy cement clinker production. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2023, 123, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altun, O. Energy and cement quality optimization of a cement grinding circuit. Adv. Powder Technol. 2018, 29, 1713–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasvand, E.; Ramezanianpour, A. Effect of grinding method and particle size distribution on long term properties of binary and ternary cements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 134, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakalakis, K.G.; Stamboltzis, G.A. Correlation of the Blaine value and the d80 size of the cement particle size distribution. ZKG Int. 2008, 61, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, H. Preparation and analysis of a polyacrylate grinding aid for grinding calcium carbonate (GCC) in an ultrafine wet grinding process. Powder Technol. 2014, 254, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramasivam, R.; Vedaraman, R. Effects of the physical properties of liquid additives on dry grinding. Powder Technol. 1992, 70, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prziwara, P.; Kwade, A. Grinding aid additives for dry fine grinding processes–Part II: Continuous and industrial grinding. Powder Technol. 2021, 394, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, G.; Yang, W. Effect of polycarboxylic grinding aid on cement chemistry and properties. Polymers 2022, 14, 3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, Y. Study on structure-performance relationship and action mechanism of organic chemicals in cement grinding aids. Mater. Lett. 2024, 364, 136365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Weibel, M.; Müller, T. Energy-effective grinding of inorganic solids using organic additives. Chimia 2017, 71, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njiru, N.E.; Muthengia, W.J.; Munyao, M.O. Review of the Effect of Grinding Aids and Admixtures on the Performance of Cements. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2023, 2023, 6697842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsioti, M.; Tsakiridis, P.E.; Giannatos, P. Characterization of various cement grinding aids and their impact on grindability and cement performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 1954–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Мирюк, O.A. Phase composition of belite cements of increased hydraulic activity. Mag. Civ. Eng. 2022, 112, 11201. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Y. The fractal characteristics of cement-based materials with grinding aid via BSE image analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, D.; Yan, P.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, D. Particle characteristics and hydration activity of ground granulated blast furnace slag powder containing industrial crude glycerol-based grinding aids. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 104, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wang, K.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y. Mechanism of triethanolamine on Portland cement hydration process and microstructure characteristics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 93, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, G.; Shi, P. Effects of polycarboxylate-based grinding aid on the performance of grinded cement. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol.-Mater. Sci. Ed. 2021, 36, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Plank, J.; Sun, Z. Investigation on the optimal chemical structure of methacrylate ester based polycarboxylate superplasticizers to be used as cement grinding aid under laboratory conditions: Effect of anionicity, side chain length and dosage on grinding efficiency, mortar workability and strength development. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 224, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, S.; Luo, Q.; Liu, W.; Xu, M. Influence of PCE-type GA on cement hydration performances. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 302, 124432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Y.; Şahin, H.G.; Mardani, N.; Mardani, A. Influence of Grinding Aids on the Grinding Performance and Rheological Properties of Cementitious Systems. Materials 2024, 17, 5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 1345-2005; The Testing Sieving Method for Fineness of Cement. Standardization Administration of PRC: Beijing, China, 2005.

- GB/T 8074-2008; Testing Method for Specific Surface of Cement-Blaine Method. Standardization Administration of PRC: Beijing, China, 2008.

- GB/T 1346-2024; Test Methods for Water Requirement of Standard Consistency, Setting Time and Soundness of the Portland Cement. Standardization Administration of PRC: Beijing, China, 2024.

- GB/T 2419-2005; Test Method for Fluidity of Cement Mortar. Standardization Administration of PRC: Beijing, China, 2005.

- GB/T 17671-2021; Test Method of Cement Mortar Strength (ISO Method). Standardization Administration of PRC: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Wang, H.; Zhao, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Du, Q.; Yan, Y. Maltitol-Derived Sacrificial Agent for Enhancing the Compatibility between PCE and Cement Paste. Materials 2023, 16, 7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobya, V.; Kaya, Y.; Mardani-Aghabaglou, A. Effect of amine and glycol-based grinding aids utilization rate on grinding efficiency and rheological properties of cementitious systems. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 47, 103917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yang, H.; Shui, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Ji, Y.; Hu, K.; Luo, Q. Preparation of polycarboxylate-based grinding aid and its influence on cement properties under laboratory condition. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 127, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchikawa, H.; Hanehara, S.; Sawaki, D. The role of steric repulsive force in the dispersion of cement particles in fresh paste prepared with organic admixture. Cem. Concr. Res. 1997, 27, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).