Abstract

Wooden cultural relics, as significant components of historical and cultural heritage, are persistently threatened by deterioration due to biological, environmental, and chemical factors. Addressing these issues is crucial not only for the conservation of cultural heritage but also for ensuring its sustainable transmission to future generations. This review systematically examines international research on the degradation and preservation of wooden cultural relics, outlining the temporal evolution, key contributing nations and research groups, major thematic focuses, and their interrelationships. We comprehensively summarize the mechanisms underlying wood degradation—including microbial attack, chemical degradation, and stress-induced deformation—and evaluate advanced techniques for detecting and assessing deterioration. Furthermore, we analyze the critical environmental and material variables that influence degradation rates. Building on this foundation, the paper surveys current mainstream conservation methodologies, such as physical and chemical reinforcement, desiccation, and drying treatments. Special emphasis is placed on emerging strategies that leverage novel materials and technologies, for instance, biomimetic hydrophobic coatings to prevent liquid water penetration and nanomaterial-based approaches for multifunctional surface treatment. Finally, we discuss persistent challenges and prospective research directions in the field, aiming to inform future scientific studies and advance practical conservation efforts for wooden cultural heritage.

1. Introduction

Wooden cultural relics, integral to the development of human civilization, have been employed extensively since the Neolithic Age in construction, tool-making, and shipbuilding, serving as a fundamental material that facilitated the rise of settled societies. Even following the advent of the Bronze Age, wooden cultural relics continued to serve as important sources of information about ancient technology, cultural practices, and artistry, owing to their skilled craftsmanship and abundance. Archeological findings worldwide underscore the remarkable formal and technical achievements embodied in ancient woodwork, while also preserving critical knowledge about timber use, finishing techniques, and inscribed records, thereby affirming their irreplaceable historical, artistic, and scientific significance (Figure 1) [1]. Unlike more durable inorganic materials such as metals or ceramics, wood is a porous, anisotropic organic polymer composed primarily of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. This complex structure renders it highly susceptible to environmental factors such as moisture, temperature fluctuations, microbial activity, and pollutants, leading to various forms of degradation [2]. Surveys on cultural heritage deterioration reveal that in humid climates, the incidence of damage in wooden cultural relics reaches as high as 41%, with severe degradation occurring more frequently than in cultural relics made from other materials. Principal degradation mechanisms include microbial decay, chemical degradation, and physical deterioration. In particular, post-excavation mishandling—such as improper drying or inadequate environmental control—can readily cause irreversible structural damage [3]. Thus, a mechanistic understanding of wood degradation across diverse environments, coupled with systematic analysis of the interplay among material composition, structure, and external factors, is essential for advancing in situ diagnostic techniques and designing effective conservation strategies. Such efforts are crucial to ensuring the scientific preservation and long-term stability of these invaluable cultural heritage objects.

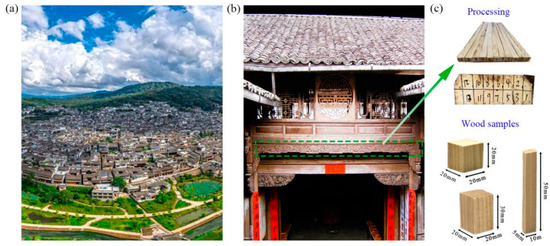

Figure 1.

(a) The overlooking view of the ancient town. (b) Location of collected wood components. (c) Wood component processing and test samples; the test includes surface composition, wettability characterization, and water uptake/moisture absorption measurement [1].

2. Global Research Statistics on Degradation and Protection of Wooden Cultural Relics

The phrases “wood relic degradation”, “wood relic corro*”, “wood relic protection”, “wood relic conservation”, “wood heritage corro*”, “wood heritage protection”, “wood heritage conservation”, “wood artifact corro*”, “wood artifact protection”, and “wood artifact conservation” were used as “Topic” (searches title, abstract, keyword plus, and author keywords) to search the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection on 10 November 2025. After excluding 1 paper from 2026, a total of 1005 papers on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics from 1987 to 2025 were obtained. The Citespace (6.2. R3) software was used to analyze data on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics papers.

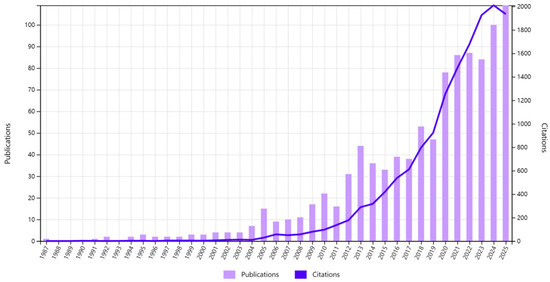

According to Figure 2, the earliest paper related to the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics was published in 1987. Before 2003, the annual number of publications remained below 5, showing a generally flat trend with minor fluctuations. After 2003, the overall research output demonstrated an upward trajectory, exceeding 100 articles in 2024 and reaching its peak in 2025. According to statistics from the Web of Science Core Collection, there are currently 1005 papers on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics, with a total of 14,927 citations. After 2012, the annual citation count grew rapidly, exceeding 1000 citations in 2020 with a total of 1253, and reaching its peak in 2024 at 2009 citations. This indicates that research topics related to the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics are attracting increasing attention from scholars.

Figure 2.

Annual publication quantity and times cited for research on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics.

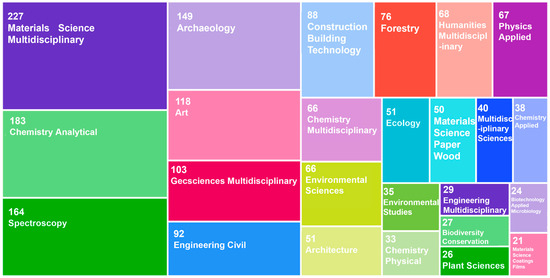

Figure 3 displays the top 25 publication quantities for research fields on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics. Based on statistics from the Web of Science Core Collection, the top 10 research fields in terms of the number of publications on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics were Materials Science Multidisciplinary, Chemistry Analytical, Spectroscopy, Archeology, Art, Geosciences Multidisciplinary, Engineering Civil, Construction Building Technology, Forestry, and Humanities Multidisciplinary. The first field is Materials Science Multidisciplinary with 227 papers, the second field is Chemistry Analytical with 183 papers, the third field is Spectroscopy with 164 papers, the fourth field is Archeology with 149 papers, the fifth field is Art with 118 papers.

Figure 3.

Top 25 publication quantity for research fields on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics.

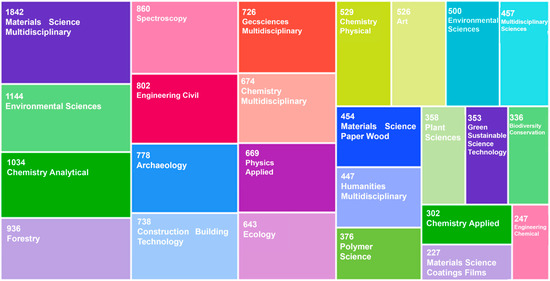

A total of 10,925 citing articles regarding the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics were identified in the Web of Science Core Collection. Figure 4 displays the top 25 citing articles for research fields on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics. Based on statistics from the Web of Science Core Collection, the top 10 research fields in terms of the number of citing articles on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics were Materials Science Multidisciplinary, Environmental Sciences, Chemistry Analytical, Forestry, Spectroscopy, Engineering Civil, Archeology, Construction Building Technology, Geosciences Multidisciplinary, and Chemistry Multidisciplinary. The first field is Materials Science Multidisciplinary with 1842 citing articles, the second field is Environmental Sciences with 1144 citing articles, the third field is Chemistry Analytical with 1034 citing articles, the fourth field is Forestry with 936 citing articles, the fifth field is Spectroscopy with 860 citing articles.

Figure 4.

Top 25 citing articles for research fields on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics.

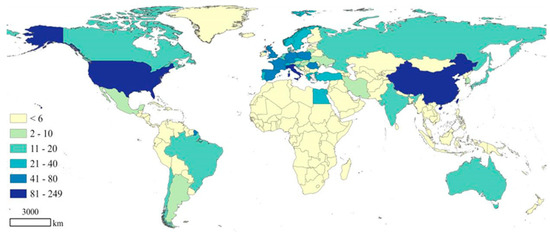

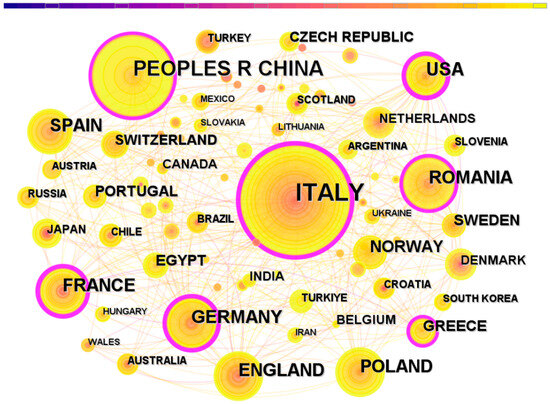

An analysis of the country distribution of publications on wooden cultural relics degradation and protection was conducted based on the aforementioned literature search. Figure 5 displays the contribution of different countries in degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics research. Figure 6 displays the network visualization among different countries (regions) that have published at least 6 papers on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics. The font size and circle area size represent the number of published papers while the circle area colors indicate the year, and the link lines among different countries (regions) indicate the collaboration activity. The top 10 countries (regions) that have published papers on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics were Italy, China, the USA, Romania, Germany, England, France, Poland, Spain, and Norway. Italy leads in the number of publications, with 249 papers on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics, while the second country was China with 147 papers. In addition, Italy, the USA, France, Germany, and China have many international collaborations with other countries or regions. This trend indicates a move towards increased international cooperation in the research on wooden cultural relic degradation and protection.

Figure 5.

The contribution of different countries in the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics research.

Figure 6.

Network visualization among different countries (regions) that have published at least 6 papers. (The color gradient from left to right represents the period from 1987 to 2025).

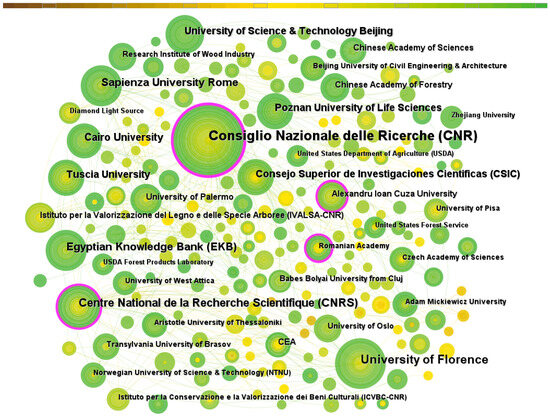

Figure 7 displays the network visualization among different institutions that have published at least 6 papers on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics. The top 7 institutions that have published papers on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics were Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR), University of Florence, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Sapienza University Rome, Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB), Cairo University, and the University of Science & Technology Beijing. Among them, the Chinese Academy of Forestry, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences were also among the most prolific institutions, ranking joint second among Chinese organizations. In addition, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR), Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Romanian Academy, and Alexandru Ioan Cuza University have many academic collaborations with other institutions.

Figure 7.

Network visualization among different institutions that have published at least 6 papers. (The color gradient from left to right represents the period from 1987 to 2025).

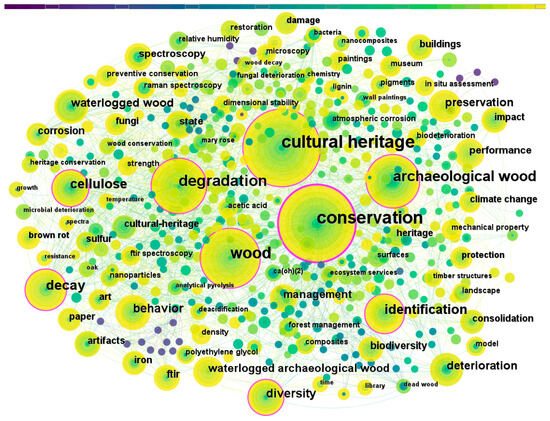

Figure 8 displays the network visualization among different keywords that have appeared in at least 5 papers on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics. From 1987 to 2025, the top 10 keywords were cultural heritage, conservation, wood, degradation, archaeological wood, decay, identification, cellulose, diversity, behavior. The word “cultural heritage” appears 136 times, “conservation” appears 125 times, “wood” appears 83 times, “degradation” appears 75 times, and “archaeological wood” appears 57 times, which means they are still the research hotspots. Among them, keywords such as conservation, wood, diversity, cultural heritage, degradation, archaeological wood, identification, and cellulose exhibit strong centrality, indicating that these keywords have significant research influence and that their related thematic studies have a broader reach. Particularly, research related to keywords such as conservation, wood, diversity, and cultural heritage constitutes the central theme of wooden cultural relic degradation and protection.

Figure 8.

Network visualization among different keywords that have appeared in at least 5 papers. (The color gradient from left to right represents the period from 1987 to 2025).

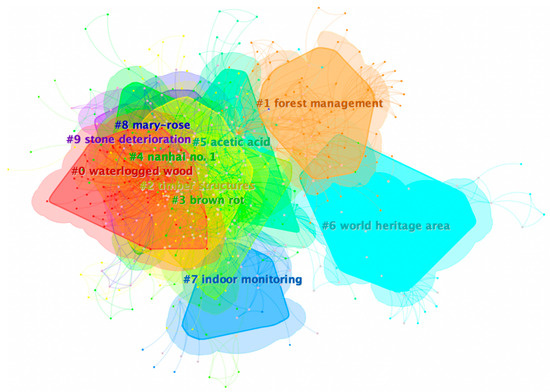

Figure 9 displays the keyword clusters derived from research papers on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics. By classifying the keywords and analyzing the related literature, the research on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics could generally be grouped into 15 categories. The first cluster is waterlogged wood with 86 keywords, including archaeological wood, decay, preservation, waterlogged wood, state, cultural relics. The second cluster is forest management with 82 keywords, including conservation, diversity, management, biodiversity, climate change, forest management, etc. The third cluster is timber structures with 74 keywords, including cultural heritage, behavior, consolidation, art, protection, damage, etc. The fourth cluster is brown rot with 60 keywords, including identification, ftir, cultural heritage, paper, fungi, brown rot, etc. The fifth cluster is Nanhai No. 1 with 53 keywords, including cellulose, performance, nanoparticles, temperature, density, heritage conservation, etc.

Figure 9.

Network visualization among the keyword clusters derived from research papers on the degradation and protection of wooden cultural relics.

3. Degradation and Characterization of Wooden Cultural Relics

3.1. Degradation Mechanisms

The deterioration of wooden cultural relics arises from a complex interplay of microbial, chemical, and physical processes [4]. Microbial degradation is primarily mediated by fungi, bacteria, and actinomycetes, which employ specific enzymatic systems to break down wood constituents in a coordinated manner [5]. Brown-rot fungi predominantly target cellulose and hemicellulose, leading to significant strength loss. White-rot fungi selectively decompose lignin, resulting in a spongy wood texture. Soft-rot fungi colonize cell walls, forming characteristic cavities and erosion zones. In waterlogged environments, diverse bacterial communities contribute to structural disintegration through enzymatic and oxidative activities, while synergistic interactions within these microbiomes further accelerate wood decomposition. Certain microbial groups, including sulfate-reducing bacteria, also generate metabolic byproducts that induce secondary chemical damage [6]. Chemical degradation involves predominantly abiotic reactions. Under acidic conditions, hydrolysis readily cleaves glycosidic bonds in cellulose and hemicellulose, reducing their degree of polymerization. Metal ions such as Fe2+ can catalyze oxidative degradation via free-radical pathways, disrupting the structural integrity of lignin and cellulose. In specific burial contexts—such as marine shipwrecks—the formation and subsequent oxidation of iron sulfides present a particularly damaging scenario: sulfuric acid generated during this process promotes further acid hydrolysis, often manifesting as wood blackening and pulverization [7]. Additionally, transition metal ions can facilitate degradation through complexation reactions, while alkaline conditions may induce β-elimination in cellulose, collectively contributing to the breakdown of the wood’s chemical matrix. Beyond biological and chemical pathways, environmental stress plays a critical role in material aging [8]. Although not involving chemical alteration, physical degradation can markedly exacerbate other degradation mechanisms. Repeated humidity fluctuations induce microcracking due to anisotropic swelling and shrinkage. Soluble salts within wood pores exert crystallization pressure during phase transitions, mechanically fracturing cell walls. Variations in temperature generate internal stresses from differential thermal expansion among material components, promoting interfacial delamination. The microcracks formed through these processes serve as pathways for microbial colonization and chemical ingress, establishing a feedback loop that synergistically accelerates the loss of structural coherence in wooden cultural relics.

3.2. Factors Affecting Degradation

The degradation of wooden cultural relics is governed by intrinsic material composition and hierarchical structure. As a natural polymeric composite, wood’s resistance to degradation fundamentally depends on the content and spatial organization of its primary constituents—cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [9]. Cellulose forms a microfibril framework that provides tensile strength, while hemicellulose and lignin act as matrix and reinforcing phases, respectively, collectively contributing to mechanical integrity and chemical stability. In general, wood species with higher lignin content tend to exhibit greater natural durability. At the microscale, cell wall thickness, pit morphology and distribution, and the presence of extractives together constitute physicochemical barriers against corrosive agents [10]. Tannins and other bioactive compounds in certain species, for instance, can effectively suppress microbial colonization. During degradation, cellulose and hemicellulose are often preferentially broken down, leaving behind a lignin-rich residue that may retain structural form but suffers severe loss of mechanical strength. Environmental conditions serve as the principal external drivers of degradation. Moisture acts as a critical activator—not only participating directly in hydrolysis but also serving as a solvent and transport medium that sustains microbial life and facilitates ion mobility [11]. Soil properties, particularly pH and soluble salt concentrations (e.g., sulfate, chloride, and iron ions), strongly influence the pathways and intensity of deterioration. Acidic conditions catalyze polysaccharide hydrolysis, alkaline environments promote cellulose β-elimination, and salt ions can both accelerate oxidation and induce physical damage through crystallization pressure [12]. Temperature, oxygen availability, and light further modulate degradation kinetics: temperature governs reaction rates and microbial metabolism; oxygen supports aerobic microbial activity and oxidative reactions; and light primarily drives surface photodegradation. Notably, these environmental factors often interact synergistically with biological agents. Microbial metabolism can alter local pH, while coupled high temperature and humidity markedly accelerate multiple degradation pathways, leading to compounded structural and chemical decline.

3.3. Characterization of Degradation

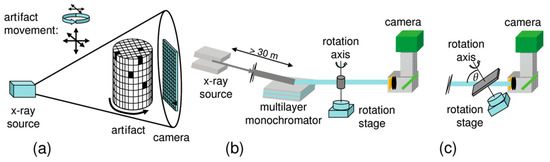

To comprehensively assess the degradation status of wooden cultural relics while adhering to the principle of minimal intervention, a variety of advanced non-destructive and micro-destructive testing technologies have been developed and applied in practice [13]. In the field of physical and mechanical property assessment, micro-destructive testing methods based on static thermomechanical analyzers (TMA) offer significant advantages: this approach requires only millimeter-scale micro-samples and, owing to its extremely high load and deformation resolution, can accurately determine the mechanical parameters of severely deteriorated waterlogged wood [14]. For example, when testing pine planks recovered from the “Nanhai No. 1” shipwreck, this method successfully revealed that their bending strength had decreased by more than 80% compared to healthy wood, thereby bridging the critical data gap between microscopic and macroscopic scales [15]. At the level of chemical composition analysis, non-destructive assessment technologies focus on probing the degradation mechanisms of wood at the molecular level. For instance, real-time direct analysis coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry enables accurate detection of wooden cultural relics in various moisture states without damaging the samples. Through constructed evaluation models, key chemical markers—such as lignin structural units, their oligomers, and polysaccharide degradation products—can be identified, effectively eliminating interference from inorganic deposits and providing molecular evidence for the precise determination of decay degree [16]. Furthermore, three-dimensional imaging and digital modeling technologies serve as powerful tools for elucidating the internal structure of cultural relics. Taking X-ray computed tomography (CT) as an example, this technique performs three-dimensional scanning and image reconstruction to non-destructively generate detailed digital models of internal structures (Figure 10) [17]. These models can be virtually sliced and analyzed, providing crucial 3D data support for internal defect localization, structural characterization, and subsequent conservation decision-making for cultural relics. Together, these complementary technologies constitute a comprehensive, multi-scale degradation diagnosis system for wooden cultural relics, spanning mechanical properties, chemical composition, and three-dimensional structure.

Figure 10.

Principle of different variants of X-ray absorption-computed tomography: (a) fan-beam tomography (X-ray tube source), (b) parallel beam tomography (synchrotron source), and (c) laminography [17]. (Reprinted/adapted with permission from American Chemical Society, 2010).

4. Protection Strategies

During the large-scale excavation and preservation of wooden cultural relics, these materials, due to their organic, porous, and hygroscopic nature, continuously face severe challenges such as biological decay (including mold), cracking and warping, and chemical degradation. Considering the degradation mechanisms of wood, the core aspects of preservation are moisture control and protection against decay. As such, it is essential to employ scientific, compatible materials and techniques for effective intervention and conservation. Currently, mainstream protection methods include physical and chemical stabilization, structural reinforcement, and advanced surface coating technologies.

4.1. Stabilization, Reinforcement, and Dehydration-Drying Techniques

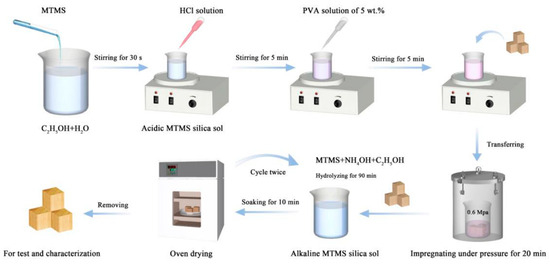

The stabilization and reinforcement of wooden cultural relics are essential steps in conservation work, aimed at addressing critical issues such as material disintegration and a decline in structural strength. These treatments are generally carried out in two stages: on-site temporary reinforcement and systematic laboratory reinforcement. In the on-site phase, physical support and environmental regulation are often employed to preserve the current state of the cultural relics and to create favorable conditions for subsequent, more refined conservation. Upon entering the laboratory reinforcement stage, material penetration methods become predominant, with polyethylene glycol (PEG) being a commonly used substance. The specific molecular weight of PEG should be selected based on the artifact’s condition and introduced using a gradient concentration method; the entire reinforcement cycle may last from 1 to 12 months [18]. Additionally, bio-based materials such as nanocellulose suspensions can be used to construct reinforcement networks within the wood cell walls through vacuum impregnation, effectively restoring the compressive strength of severely degraded wood [19]. Epoxy resin or composite sol has also attracted considerable attention due to its excellent permeability and aging resistance [1,20]. The acidic MTMS silica sol generated by hydrolysis of MTMS under acidic conditions is combined with PVA solution to form a treatment agent, and then the surface of the wood is treated by an impregnation process. The active components formed during this process can interact with the wood matrix, thereby enhancing surface protection and improving the stability of the wood, as shown in Figure 11. For wooden cultural relics exhibiting surface powdering, spraying with low-viscosity acrylic resin is commonly necessary to increase the surface bonding strength [21].

Figure 11.

Mechanism of PVA/MTMS–silica sol composite solution modified wood surface [1].

Dehydration and drying are core processes in the conservation of waterlogged wooden cultural relics, with the method chosen depending on factors such as wood moisture content, degree of degradation, and wood species. For cultural relics with only slight decay, natural drying may be employed by maintaining an ambient temperature of 20 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 65 ± 5%, allowing for gradual dehydration in a stepwise fashion. For moderately degraded wood, freeze-drying is commonly utilized: the sample is rapidly frozen to −30 °C and then dehydrated by sublimation in a vacuum environment, thereby stabilizing the material structure. Severely decayed wooden cultural relics often require supercritical drying. In this method, supercritical CO2 is used as the medium, which can prevent structural damage caused by liquid-phase surface tension, although the cost is relatively high [22]. Dehydration using PEG reagents through a staged immersion process with increasing concentrations is also a widely adopted approach, albeit one with a relatively long treatment cycle [23]. Furthermore, the trehalose method—which is characterized by low hygroscopicity and excellent biocompatibility—has been applied and validated in several landmark conservation projects, yielding outstanding results [24].

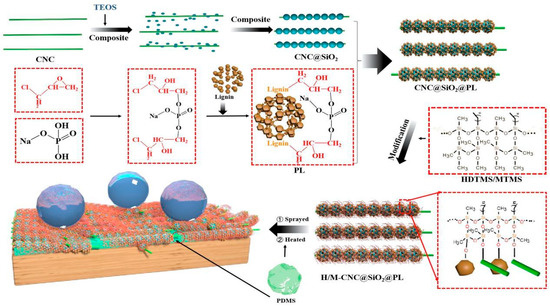

4.2. Biomimetic Hydrophobic Surface Protection

Due to their porous and hygroscopic nature, wooden cultural relics are highly susceptible to moisture intrusion, which can lead to a series of deterioration issues such as cracking, deformation, and mildew-induced decay. Therefore, constructing an effective hydrophobic surface protective layer to prevent environmental moisture infiltration provides a promising solution for prolonging the lifespan of these cultural relics. Traditional water-based polyacrylic (PA) coatings are widely used for their environmental friendliness, high transparency, and good reversibility [25]. However, their inherent deficiencies in water resistance and weatherability often result in whitening and failure of the coating under high-humidity conditions, severely limiting their long-term effectiveness in the conservation of cultural relics [26]. Inspired by naturally hydrophobic surfaces such as lotus leaves, imparting superhydrophobic properties to coatings through material modification has proven highly effective. For example, copolymerizing and introducing hydrophobic segments—such as the modification of polyacrylic with epoxy resin—can enhance water resistance. However, the introduced epoxy groups are prone to oxidation, which in turn weakens the weatherability of the coating [27]. Additionally, the incorporation of low surface energy chemical bonds can significantly reduce the surface energy of the coating. For example, Xu et al. combined titanium dioxide with fluorinated polymers to improve water resistance. However, due to the poor compatibility between inorganic and organic components, the wear resistance of the coating is reduced, making it unable to meet the requirements for long-term protection [28]. To address these challenges, a composite coating strategy has been proposed. Zhang et al. utilized the high mechanical strength of cellulose nanocrystals and the flexible deformation ability of PDOS to prepare a superhydrophobic wood coating using CNC@SiO2@PL composite rods. This coating not only achieved a high contact angle of 157.4°, but also significantly improved wear resistance (Figure 12) [29]. The application of this technology is expected to significantly reduce restoration risks, extend the protection cycle, and provide a safer and more reliable solution for the long-term stable preservation of wooden cultural relics.

Figure 12.

Preparation process demonstration and forming mechanism of CNC@SiO2@PL-based superhydrophobic wood, and possible chemical reactions during preparation [29].

4.3. Surface Functionalization Technology of Nanomaterials

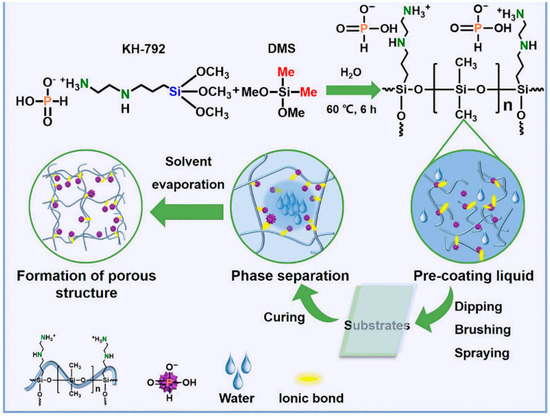

The deterioration of wooden cultural relics is a complex, multi-factor process involving not only biological damage caused by microorganisms but also risks such as fire and the decline of physical and chemical properties. Traditional protective materials often have single functions and, due to weak adhesion within the porous wooden structure, are susceptible to detachment, making it difficult to ensure long-term and comprehensive protection. Nanomaterials, thanks to their small particle size, large specific surface area, and high reactivity, offer new avenues for developing multifunctional, efficient, and durable protection technologies for wooden cultural relics. The core of nanomaterial surface functionalization technology lies in exploiting nanoscale effects to endow the wooden matrix with integrated properties that surpass those achieved by traditional methods. Metal and metal oxide nanoparticles are widely used as functional units. For example, silver nanoparticles possess broad-spectrum, highly effective antibacterial properties; their high specific surface area and strong penetrative ability enable them to easily disrupt microbial cell structures, effectively inhibiting and eliminating the fungi and bacteria that damage wooden cultural relics [30]. In addition to their antibacterial and anti-corrosive effects, nanotechnologies also show great promise in enhancing the flame-retardant properties of wooden cultural relics [31]. For instance, micron- or nanoscale structures formed through the self-assembly of heteropoly acids can facilitate the formation of dense and robust carbon layers on wood surfaces when heated, effectively isolating heat and oxygen and thereby significantly improving the thermal stability of cultural relics [32]. Furthermore, the construction of composite nanostructure systems can impart multifunctional properties to the materials. For example, silver nanoparticles combined with phosphotungstic acid through in situ self-assembly can form acidic nanospheres that achieve low-dose, uniform, and robust loading onto the pores of wood cell walls and internal surfaces [33]. As a result, the wood surface simultaneously exhibits antibacterial properties, accomplishing the goal of multi-effect protection. Zhang et al. developed a highly transparent flame retardant protective coating by designing a nanoporous structure inspired by the moth-eye effect and utilizing a phosphorus–nitrogen–silicon synergistic flame retardant mechanism. The coating achieved a visible light transmittance of over 97% and efficient fire resistance, providing long-term multifunctional protection for various substrates such as wood (Figure 13) [34]. By precisely designing and regulating material structure and function at the nanoscale, nanomaterial surface functionalization technology can establish an intelligent protective layer for wooden cultural relics. This technology not only demonstrates outstanding efficacy but also, due to its minimal dosage requirements and high durability, minimizes interventions to the original artifact and presents broad prospects for practical application.

Figure 13.

Schematic illustration of the preparation of the N-[3-(trimethoxysilyl) propyl]ethylenediamine (KH-792) and dimethoxy-dimethylsilane (DMS) mixed coating [34]. (Reprinted/adapted with permission from American Chemical Society, 2024).

5. Prospect

The literature analysis presented in this study highlights potential directions for future research. For instance, differences in research output between countries may be closely related to their forest resource endowments, the quantity of wooden cultural heritage, and unique historical backgrounds. Future studies could consider developing more sophisticated models that integrate forestry data, economic indicators, and historical records. By employing normalized indicators such as research output per unit of forest area or per capita quantity of cultural heritage, researchers can conduct a more in-depth analysis of the driving factors. This approach would help to more accurately reveal the underlying mechanisms shaping the global landscape of research on wooden cultural heritage. In addition, although significant progress has been made in the research on the deterioration and conservation technologies of wooden cultural relics, multiple challenges remain. Currently, the coupled kinetics of microbial community succession and chemical degradation under wet-dry cycling conditions are still unclear, and there is a lack of systematic evaluation regarding the long-term interfacial stability and reprocessing properties of nanocellulose in decayed wood. To address these issues, future research should focus on the following directions: At the mechanistic level, it is necessary to conduct quantitative studies on the multi-factor coupled mechanisms of deterioration and to elucidate the synergistic or antagonistic effects among different deterioration factors. This can be achieved through humidity–temperature–microorganism multi-field coupling experiments and model construction, thereby providing a theoretical basis for predictive conservation. In terms of detection technology, efforts should be made to develop in situ diagnostic and early warning methods for the early stages of deterioration. For example, technologies such as fluorescence probes based on molecular markers and terahertz imaging can be used to improve sensitivity to early-stage damage. With respect to conservation materials, new environmentally friendly options should be developed. The application of bio-based materials, organosilicon resins, and smart responsive materials for reinforcement and dehydration treatments should be explored, while their long-term performance should be systematically evaluated through accelerated aging experiments. For microbial deterioration, ecological prevention and control strategies based on quorum sensing inhibition may be developed, or beneficial microorganisms can be introduced to competitively inhibit corrosive microbial populations, achieving green protection. Finally, with respect to technological integration, an intelligent monitoring and digital conservation platform should be constructed. By combining IOT, multi-sensor fusion, and artificial intelligence algorithms, a real-time monitoring and diagnostic system can be established for the deterioration of cultural relics. Additionally, digital twin technology can be used to enable virtual simulation and optimization of the conservation process. In summary, the future conservation of wooden cultural relics should emphasize the interdisciplinary integration of materials science, microbiology, environmental engineering, and information technology. Efforts should shift from mere description of deterioration phenomena to mechanistic analysis, advancing conservation technology from empirical approaches to precise and intelligent solutions, thereby ultimately ensuring the sustainable preservation and continued value of wooden cultural relics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. and C.Y.; methodology, L.Z.; software, L.Z. and C.Y.; validation, C.Y. and L.Z.; formal analysis, C.Y.; investigation, Y.G.; resources, L.Z.; data curation, L.Z. and C.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Z. and Y.G.; writing—review and editing, C.Y. and Y.G.; visualization, C.Y.; supervision, C.Y.; project administration, L.Z., Y.G. and C.Y.; funding acquisition, L.Z., Y.G. and C.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Social Science Foundation of Fujian Province (Lingling Zhang, FJ2024BF046); the Innovation Strategy Research Program of Fujian Province (Lingling Zhang, 2025R0059); Startup Fund for Advanced Talents of Putian University (Lingling Zhang, 2024154).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zheng, S.J.; Tang, W.; Tong, J.H.; Cao, K.H.; Yu, H.J.; Xie, L.K. Innovative Treatment of Ancient Architectural Wood Using Polyvinyl Alcohol and Methyltrimethoxysilane for Improved Waterprooffng, Dimensional Stability, and Self-Cleaning Properties. Forests 2024, 15, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, D.N.S. Weathering and photochemistry of wood. In Wood and Cellulosic Chemistry; Hon, D.N.S., Shiraishi, N., Eds.; Marcel Dekker Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 512–546. [Google Scholar]

- Derbyshire, H.; Miller, E.R. Photodegradation of wood during solar irradiation. Holz. Roh-Werkst. 1981, 39, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, W.C.; Hon, D.N.S. Chemistry of weathering and protection. In The Chemistry of Solid Wood; Rowell, R.M., Ed.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1984; pp. 401–451. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Liu, H. Research progress of wood cell wall modification and functional improvement: A review. Materials 2022, 15, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, M.; Cooper, P. Exterior wood coatings. In Wood in Civil Engineering; Concu, G., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017; pp. 145–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Shen, D.W.; Zhang, Z.G.; Kang, H.L.; Ma, Q.L. Comparison of iron deposits removing material from the marine archaeological wood of Nanhai I shipwreck. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 66, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.J.; Schroeder, L.R.; Lai, Y.Z. Impact of Residual Extractives on Lignin Determination in Kraft Pulps. J. Wood. Chem. Technol. 2005, 24, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Kuang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Burgert, I.; Keplinger, T.; Gong, A.; Li, T.; Berglund, L.; Eichhorn, S.J.; Hu, L. Structure–property–function relationships of natural and engineered wood. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 642–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjostrom, E. Wood Chemistry: Fundamentals and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Willems, W. Heuristic study on the interaction between heat exchange and slow relaxation processes during wood moisture content changes. Holzforschung 2021, 75, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melro, E.; Filipe, A.; Sousa, D.; Valente, A.J.M.; Romano, A.; Antunes, F.E.; Medronho, B. Dissolution of kraft lignin in alkaline solutions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 148, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.K.; Zhang, Q.H.; Li, X.; Li, S.F.; Xu, C.J.; Li, L.T.; Zhu, L.P.; Gao, Y.; Yin, J.X.; Xie, L.; et al. Nanoparticle-enabled rapid detection of microbial threats to Sanxingdui ancient ivories. J. Cult. Herit. 2025, 73, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.T.; Han, X.N.; Yin, Y.F.; Xi, G.L.; Zhang, Z.G.; Sun, J.; Chen, G.; Zhang, L.T.; Han, L.Y. Multi-property prediction of waterlogged archaeological wood based on Wasserstein GAN-augmented tree models. J. Cult. Herit. 2025, 76, 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z.F.; Wu, M.R.; Han, X.N.; Han, L.Y. A new non-destructive method for flexural strength testing of waterlogged archaeological wood. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 2023, 35, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, S.Q.; Chen, X.Q.; Chen, S. Application of photoluminescent materials in cultural relics protection. Rsc. Adv. 2025, 15, 37074–37089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, K.; Dik, J.; Cotte, M.; Susini, J. Photon-Based Techniques for Nondestructive Subsurface Analysis of Painted Cultural Heritage Artifacts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Wang, X.X.; Chen, W.X.; Zhu, L.G.; Zhang, B.J. Environmental stimulant-responsive hydrogels based on polyethylene glycol-derived polymer for underwater bonding and extraction of fragile wooden relics: Synthesis, characterization, and preliminary application. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2024, 131, 103651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zeng, Y.; Zhou, L.; Feng, N.; Li, C.; Sheng, L.; Li, Y.; Sun, J. Consolidation of waterlogged archaeological woods by reversibly cross-linked polymers. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2024, 57, 104675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.Q.; Wen, M.Y.; Shi, J.Y.; Park, H.; Zuo, H.W.; Ren, Y.N.; Lv, L.X.; Zhao, X.F.; Du, H.S.; Yang, X.J.; et al. Nanocomposite based ceramicizable functional coating with simultaneous flame retardancy and UV resistance for wood building material protection. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 492, 143016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.J.; Tian, M.L.; Wang, X.; Pan, M.W.; Pan, Z.C. Adaptive microgel films with enhancing cohesion, adhesion, and wettability for robust and reversible bonding in cultural relic restoration. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2025, 693, 137558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, I.; Bartoletti, A.; Viana, C.; Cardoso, I.P.; Casimiro, T.; Ferreira, J.L. Dense carbon dioxide technologies applied to the conservation of cultural heritage: A review. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2025, 229, 106821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, B.J.; Hu, Y.N. Acomparative study of reinforcement materials for waterlogged woodrelics in laboratory. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 36, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzner, I.; Stelzner, J.; Fischer, B.; Hamann, E.; Zuber, M.; Schuetz, P. A multi-technique and multiscale comparative study on the efficiency of conservation methods for the stabilisation of waterlogged archaeological pine. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Liu, T.; Zhang, B. The preservation damage of hydrophobic polymer coating materials in conservation of stone relics. Prog. Org. Coat. 2013, 76, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Tsavalas, J.G.; Sundberg, D.C. Water whitening of polymer films: Mechanistic studies and comparisons between water and solvent borne films. Prog. Org. Coat. 2017, 105, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Mao, X.; Zhu, H.; Lin, A.; Wang, D. Water and corrosion resistance of epoxy–acrylic–amine waterborne coatings: Effects of resin molecular weight, polar group and hydrophobic segment. Corros. Sci. 2013, 75, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munekata, S. Fluoropolymers as coating material. Prog. Org. Coat. 1988, 16, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ren, C.; Sun, Y.; Miao, Y.; Deng, L.; Wang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Huang, J. Construction of CNC@SiO2@PL Based Superhydrophobic Wood with Excellent Abrasion Resistance Based on Nanoindentation Analysis and Good UV Resistance. Polymers 2023, 15, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, R.; Parida, D.; Borgstädt, J.; Lehner, S.; Jovic, M.; Rentsch, D.; Gaan, S. In-situ phosphine oxide physical networks: A facile strategy to achieve durable flame retardant and antimicrobial treatments of cellulose. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 417, 128028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pączkowski, P.; Puszka, A.; Miazga-Karska, M.; Ginalska, G.; Gawdzik, B. Synthesis, characterization and testing of antimicrobial activity of composites of unsaturated polyester resins with wood flour and silver nanoparticles. Materials 2021, 14, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumont, A.; Wipff, G. Ion aggregation in concentrated aqueous and methanol solutions of polyoxometallates Keggin anions: The effect of counterions investigated by molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6940–6953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.L.; Wang, Z.W.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.Q. Enhancing durable fire safety and Anti-corrosion performance of wood through controlled In-Situ Self-Assembly synthesis of Ag-PW nanospheres. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 475, 145227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, A.N.; He, M.S.; Zheng, G.Q.; Zeng, F.R.; Wang, Y.Z.; Liu, B.W.; Zhao, H.B. Biomimetic Nanoporous Transparent Universal Fire-Resistant Coatings. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 19519−19528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).