Abstract

The output power of photovoltaic modules is significantly reduced by solar irradiance shading. To address this issue, innovative strategies for mitigating shading effects have been continuously explored. In this study, detailed research on the edge dust accumulation effect of modules has been conducted. It is found that under vertical installation, when the shading ratio reaches 50%, the output power of full-cell modules decreases by 42%, while that of half-cell modules drops by only 27%. Moreover, when the shading ratio reaches 100%, the output power of full-cell modules declines by nearly 99%. In contrast, half-cell modules are still able to maintain nearly 50% of their output power. These results demonstrate that half-cell modules exhibit significantly better resistance to shading compared to full-cell modules. On the other hand, under a horizontal layout, power degradation for both full-cell and half-cell modules is observed to be approximately 16% when the shading ratio is 25%, and around 36% when the coverage reaches 50%. Experimental results further revealed that shading under horizontal orientation leads to a multi-peak power output profile, which poses a risk of the PV inverter being trapped in local maxima. Overall, half-cell modules demonstrated better resistance to dust-induced shading under both layouts. Based on these findings, novel module design schemes are proposed to enhance resistance to dust accumulation effects. The proposed method can effectively reduce power losses caused by edge dust-induced shading and improve the annual power generation of PV modules, thereby offering technical support for effectively enhancing the operational stability of PV power generation systems.

1. Introduction

With the global energy structure transitioning toward low carbonization, PV power generation is playing an increasingly vital role in modern energy systems due to the characteristics of being clean, distributed, and scalable [1]. Enhancing the power generation capacity of both large-scale photovoltaic (PV) systems and small distributed PV power plants has long been a core objective pursued by the industry. Numerous existing studies have thoroughly investigated the physical mechanisms induced by partial shading of PV modules: For instance, Ge et al. [2] explored the hotspot mechanism caused by avalanche breakdown. Appelbaum et al. [3] analyzed shading losses resulting from building or inter-row shading. Ge et al. [4] proposed a low-resistance hotspot diagnosis and suppression strategy based on I-V characteristic analysis. Craciunescu [5] and El Iysaouy [6] separately conducted optimization studies on module configurations, MPPT algorithms, and array modeling under shading conditions. Kumari [7] experimentally analyzed the impact of single-cell shading on module performance and potential damage. Additionally, Alabdali [8] systematically summarized the effects of different shading sources (e.g., inter-row layout, clouds, trees, buildings) on I-V curves and power losses, as well as mitigation measures such as bypass diodes. Collectively, these studies indicate that shading can lead to current reduction, current mismatch, and even abnormal activation of bypass diodes or reverse bias, thereby decreasing module output power, shortening service life, and posing operational safety risks.

Focusing on the structural models of PV modules and their actual operating environments, namely exploring the theoretical and technical issues related to multi-factor shading and their coupling effects, including the shading effect of core components (e.g., cell electrodes), dust accumulation at module edges, adhesion of foreign objects such as bird droppings on surfaces, and building/environmental shading, has become a key research hotspot in PV technology. For example, Pareek et al. [9] compared the power generation performance of different interconnection schemes under partial shading, emphasizing the role of array interconnection structures in mitigating local shading and current mismatch. Ramezani [10] established a refined shading model capable of evaluating the impact of shading (caused by electrode shading, foreign object adhesion, and environmental shadows) on module I-V characteristics and power output. Sezgin Ugranlı [11] studied the regulatory effects of the number of bypass diodes and inverter efficiency curves on the global maximum power point (GMPP) and output power of systems under multi-factor shading conditions, reflecting the coupling effects of different shading factors. Özkalay et al. [12] analyzed local shading, shadow movement, and their long-term impacts on module reliability in built environments, revealing the risk of high-frequency hotspots. Al Mahdi et al. [13] reviewed the degradation and failure mechanisms of PV modules, including dust accumulation, surface foreign objects, hotspots, and encapsulation aging, reflecting the cumulative effects of multi-factors in long-term operating environments. Tummalieh et al. [14] comprehensively analyzed the impacts of shading, inhomogeneity, aging, and bypass diode failures on power output and annual yield through multi-physics modeling, quantifying the systemic effects of multi-factor coupling.

Therefore, the aforementioned studies collectively demonstrate that conducting research on the shading mechanisms of PV modules and optimizing module structures—with the aim of improving the power generation efficiency of PV systems and ensuring their safe long-term operation despite the inability to fully eliminate shading effects—hold significant scientific significance and engineering value.

In the industrialization process of pursuing grid parity for PV, large-size cells measuring 180 mm × 180 mm and 210 mm × 210 mm, along with their corresponding large-area modules, have emerged as mainstream products. For current leading solar cell structures such as TOPCon and HJT, the electrode design typically permits a shading area of around 10%, and a multi-busbar layout featuring uniform busbar width and elongated strip geometry is commonly employed [15].

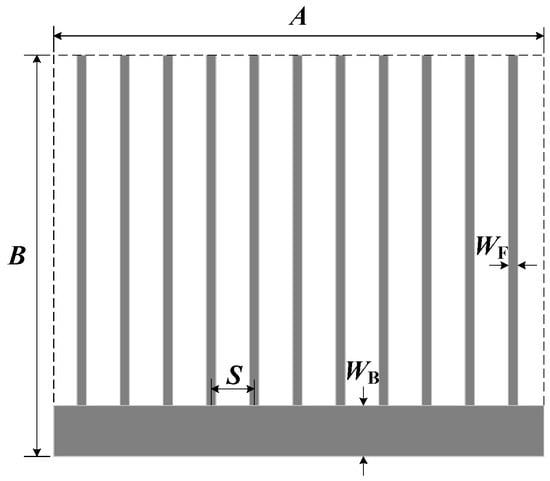

A solar cell is composed of multiple unit cells, with the structure of a typical unit cell illustrated in Figure 1. The busbar, with a width of WB and a length of A, serves to summarize current and interconnect battery cells to each other. The finger gird, having a width of WF and a length of B, is responsible for collecting current from corresponding micro-regions. The spacing between adjacent finger grids is denoted as S. The design of the cell electrodes is closely related to their fabrication process. The use of large-size solar cells can significantly improve their cost performance; however, large-size cells also introduce more severe electrode shading issues. One theoretical study indicates [15] that the power loss associated with the finger grid electrodes of the cell mainly depends on the cell materials and process technology, as shown in Equation (5). In contrast, the power loss of the busbar is directly related to the unit structure. When the length of the busbar electrode is A, the associated power loss is proportional to A, as shown in Equation (8). For the definitions of relevant parameters in Equations (1)–(8), refer to Reference [15].

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of a typical unit solar cell structure.

To mitigate electrode shading losses in large-size solar cells, a laser cutting technique has been developed in the industry. This process allows for the low-cost and high-quality division of cells into n equal parts, effectively reducing the unit cell length A and providing a technically favorable scheme to minimize the shading losses. Taking into account the fabrication complexity and factors, such as cost–performance, large-size half-cell modules have become the most advantageous solution under the current process constraints [16,17]. Compared with full-cell modules of the same size, the output power of half-cell modules can be increased by 8%–15%, which significantly reduces the output current loss caused by electrode shading of solar cells as cell size increases. With the development of novel process regimes for solar cells and improvement in PV module fabrication technologies, 1/3- to 1/6-cut-cell PV modules, tailored for more segmented application markets, will play a more effective role.

Shading caused by the front electrodes of solar cells is a type of regular shading, which can be anticipated and mitigated through corresponding countermeasures. However, the impact of irregular shading from external factors, such as dust accumulation, surface foreign object adhesion, and cloud shading, on PV modules cannot be ignored. Currently, the primary strategy for optimizing the structure of PV modules is the “half-cell module” solution. It adopts an internal electrical connection structure with two upper and lower strings connected in parallel, which not only facilitates the automated production but also effectively improves the power output of the module, making it a favorable compromise [18,19].

Since the large-scale application of photovoltaic, PV, modules, extensive attention has been paid to research on the impacts of shading on module performance and their underlying laws. For instance, studies have shown that building or environmental shading may induce hotspots and affect module reliability [12], while half-cell modules and different installation methods can effectively mitigate power losses caused by partial shading [18,20]. To address complex shading conditions, researchers have proposed various maximum power point tracking (MPPT) control strategies, including meta-heuristic optimization algorithms [21], generalized pattern search algorithms [22], improved PS-FW algorithms [23], hybrid MPPT techniques [24], comparisons of single/multi-MPPT structures [25], and optimized applications in grid-connected systems [26]. These studies demonstrate that there exists a significant coupling effect between module structure, installation method, and control strategy under shading conditions. Among these factors, the internal electrical interconnection scheme of the module is the core determinant of output performance and shading sensitivity, playing a crucial role in achieving systematic optimization, improving power generation efficiency, and enhancing long-term stability. In conventional full-cell modules, all cells are connected in a single series string; when a cell is shaded, the bypass diode may be activated, leading to a sharp drop in output voltage [27,28,29]. In contrast, half-cell modules incorporate two parallel circuits, which effectively suppress the negative effects of shading on output performance. Significant reductions in power loss and mitigation of hotspot effects have been observed in half-cell configurations under a wide range of shading scenarios [12,18]. In practical applications, the impact of installation direction on the performance of PV modules is also a critical research topic [17,20]. The effects of shading vary considerably between horizontal and vertical installations, exhibiting distinct impact patterns under different directions [30,31]. Academic and industrial communities have also conducted extensive explorations into multidimensional strategies such as multi-busbar cells, distributed bypass diodes in modules, and micro-inverters integrated with modules. For instance, shingled solar modules significantly enhance output under partial shading and reduce hotspot risks through series/matrix interconnection structures [30]. The design of low-cost, large-area bifacial interdigitated back-contact (IBC) solar cells with a front-floating emitter optimizes power losses under complex shading conditions [32]. Modeling of half-cell modules and analysis of bypass diode configurations have demonstrated effective mitigation of output mismatch in shading scenarios [33]. Module-Level Power Electronics (MLPE) systems have improved power distribution and system reliability under local shading conditions [31,34,35]. Distributed power electronics technologies (e.g., submodule-level converters) have almost completely suppressed the hotspot phenomenon [36]. The application of power optimizers in Building-Integrated Photovoltaic (BIPV) systems can significantly reduce shading-induced power losses [37]. Meanwhile, studies on micro-inverters and yield modeling have evaluated the overall system performance under different shading conditions [38].

The cleanliness level of PV module surfaces directly affects their power generation efficiency, with the edges of modules becoming dead zones for dust accumulation. Figure 2 illustrates real-world surface conditions of several PV modules. Even though large-scale PV power plants conduct regular manual or mechanical cleaning, extremely hard-to-remove dust remains on the edge areas. For small-scale PV systems without automatic cleaning, the surface cleanliness issue is even more prominent. For the long-uncleaned PV arrays (module strings) shown in Figure 2, their power generation capacity is severely impaired. However, there are few reported studies on the design and optimization of systematic experimental schemes targeting dust shading issues at the edges of modules with different structures.

Figure 2.

Some examples of dust accumulation on the corners and edges of the PV modules.

To address the aforementioned research gap, this study designs multiple sets of controlled experimental schemes targeting the practical issue of edge dust accumulation on PV modules. Under laboratory conditions, the influence laws of different module structures and installation methods on the electrical performance of modules are systematically analyzed. The performance advantages of half-cell modules under typical edge dust shading and their internal current transmission characteristics are revealed, and it is found that horizontal installation may induce multi-peak power output, thereby affecting the stability of maximum power point tracking (MPPT). Based on experimental results and mechanism analysis, this study proposes engineering-oriented module structure optimization strategies, which provide operable design references for mitigating uneven shading losses caused by dust accumulation, while offering a scientific basis for future module structure innovation and on-site deployment strategies.

2. Experiment

2.1. Experimental Method

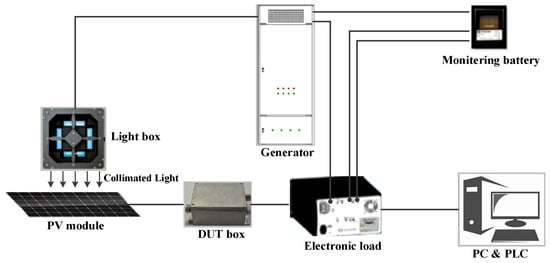

The experiment was carried out using the PASAN High LIGHT system developed by Meyer Burger. The irradiance was 1000 W/m2, the ambient temperature was 25 °C, the spectrum referenced the ASTM G173-03 standard [39], and the wind speed was 0 m/s for the experiment, which fully satisfy the STC testing standard. The layout of the testing system is illustrated in Figure 3. The system primarily comprises a light source chamber, light source power supply, electronic load, monitoring and control battery, device under test (DUT) test box, and programmable logic controller (PLC).

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of electrical characteristic testing system for PV module.

The system utilizes a xenon flash lamp as the light source and is designed in accordance with the IEC 60904-9 standard. Both illumination uniformity and spectral matching degree reach Grade A+, thus ensuring high accuracy in power measurement. The light source chamber simulates the AM1.5 spectrum through shading filters and spectral filters; the light source power supply uses a capacitor to adjust light intensity and drive the xenon lamp for flashing. Irradiance and temperature data are collected in real time by monitoring the cells and fed back to the control system through the electronic load, enabling closed-loop control of both irradiance and temperature. The electronic load applies a voltage scan to the module while synchronously collecting data on current, voltage, temperature, and light intensity. Moreover, the DUT test box provides a safe and reliable electrical interface between the photovoltaic module and the electronic load, and is equipped with switching and protection functions. The entire system is coordinated by a PLC, ensuring stable operation and full compliance with STC requirements.

Before testing, automatic calibration was carried out using a standard reference module. The output data of the reference module are compared with values certified by an accredited laboratory to calibrate the measurement and control parameters of the system. Subsequently, the PV module under testing is connected to the DUT port, after which the experiment is automatically carried out. A comprehensive test report is then generated, detailing parameters such as open-circuit voltage, short-circuit current, maximum power point (MPP), and the I-V characteristic curve.

2.2. Experimental Design

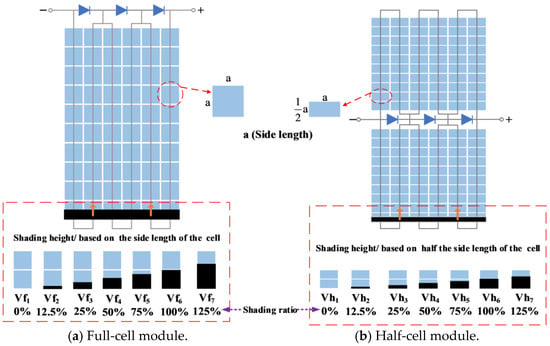

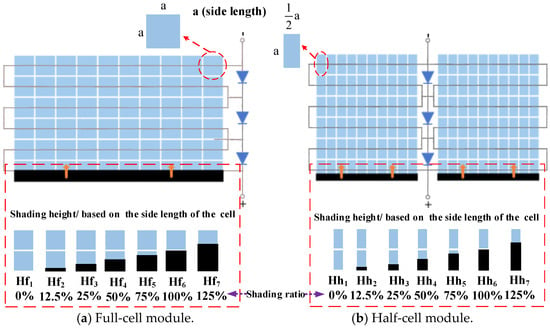

Both full-cell and half-cell modules were tested under two shading configurations—vertical shading (along the short edge) and horizontal shading (along the long edge)—simulating the edge shading effects caused by dust under different installation conditions. All tests were performed under STC, with only the shading configuration being varied. Shading strips with height ratios of 0%, 12.5%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 100%, and 125% were applied to the surface of the photovoltaic modules, resulting in seven distinct scenarios. The shaded area is completely opaque, meaning it receives no light. A shading ratio of 0% indicates no obstruction, while 12.5% corresponds to a shading height equal to 0.125 times the side length of the solar cell. The remaining cases follow the same proportional relationship. When there are no shading strips, the main electrical parameters of the tested full-cell and half-cell modules are listed in Table 1. The deviations from the nameplate values are within 3%, demonstrating good agreement between the test results and the nominal specifications provided by the manufacturer. The detailed layout and dimensions of the shading strips are illustrated in Figure 4 and Figure 5 and summarized in Table 2. In this study, the height of the shading strips is set based on the side length a of the full cell. For the half-cell, the length along the long side is a, while the length along the short side is a/2.

Table 1.

Electrical parameters of the PV module.

Figure 4.

Schematic of vertical shading layout case.

Figure 5.

Schematic of horizontal shading layout case.

Table 2.

Shading height of solar cell for different configurations.

The entire testing process was strictly conducted in accordance with the predefined procedures. Baseline testing was first conducted on the modules without any shading strips, during which the corresponding data were automatically recorded by the system. The PV module was then removed and rearranged with the shading strip. On this basis, the procedure was repeated to collect the new experimental data. Tests were repeated twice at the same shading ratio, with data recorded separately. The data were validated only when the two measurements fell within the error range. To minimize the influence of external factors, the experimental system was automatically configured to compensate for fluctuations in illumination and temperature deviations, ensuring that the results were not affected by parameter variations. As a result, the experimental data were confirmed to be credible, reliable, and reproducible. All data were automatically stored by the testing system and systematically archived according to shading pattern (horizontal/vertical), module type, and shading ratio.

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

3.1. Vertical Shading Configuration

PV power stations are affected by the atmospheric environment over long periods. The accumulation of airborne catkins on the surface of solar cells has been found to significantly increase the adhesion of particulate matter. It is observed that the lower edges and corners of the cells are particularly prone to formation of dust that is difficult to remove. This accumulation substantially impairs the power generation performance of the modules, leading to the actual annual power output of PV power stations falling far below the estimated power output. In this experiment, the use of shading strips intuitively simulated this scenario, and the resulting data quantitatively demonstrated its impact. From the simulation results, it is found that the dust-induced shading is a key factor in the underperformance of PV power stations.

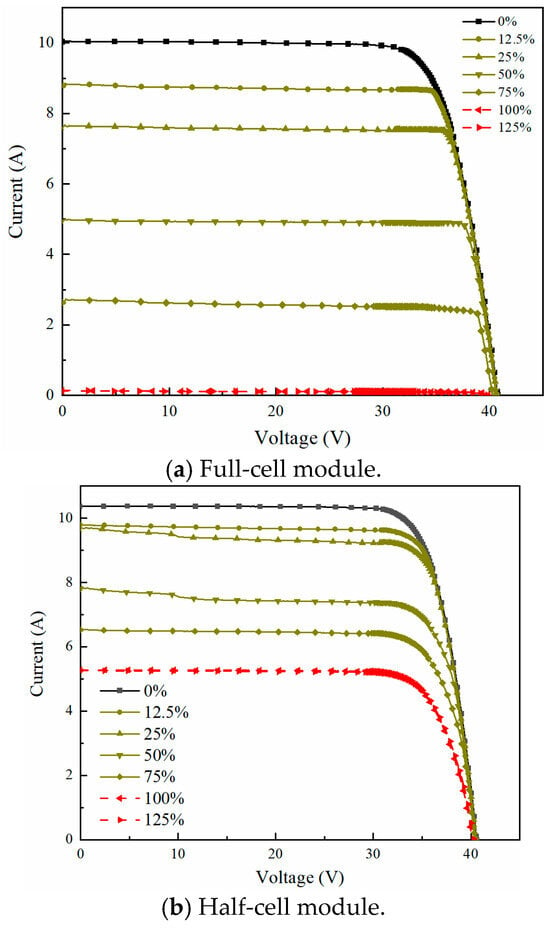

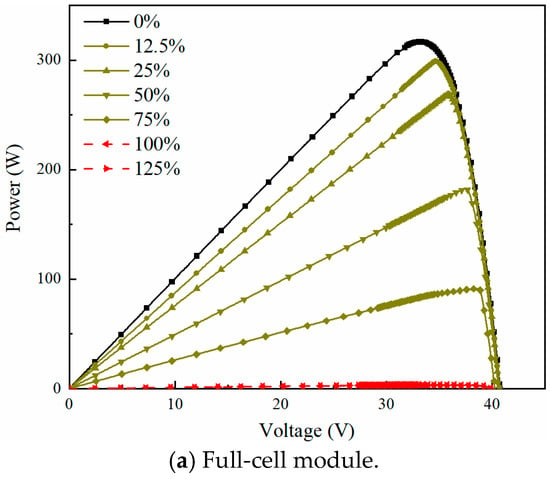

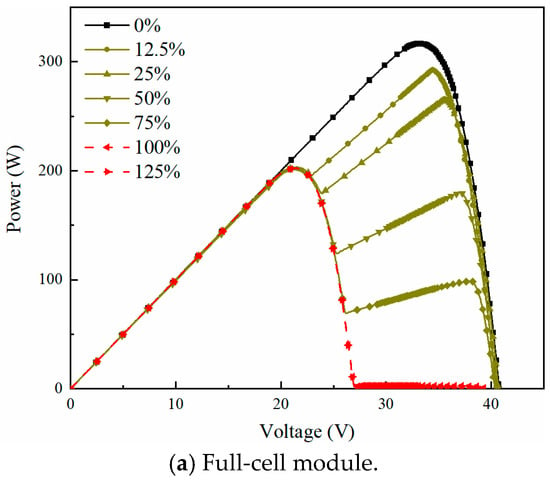

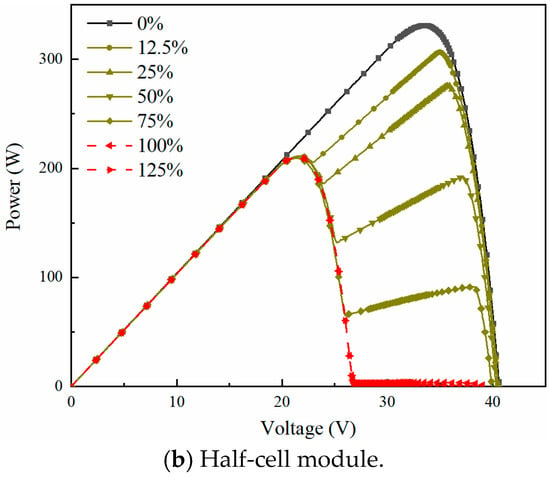

Table 3 summarizes the variations in voltage, current, and power near the maximum power point of the modules under the vertical shading layout. Figure 6 presents the variation trend of the I-V characteristics of the module. Figure 7 displays the curves of maximum power output under different shading ratios. As shown in Table 3, it is found that when the cells on the bottom row (100% shading ratio) of a full-cell module are shaded by the shading strip (the module is installed at a certain angle in practice), the maximum power output drops to only 3.65 W, which is merely 1.2% of the nominal value. This indicates an almost-complete loss of power generation capability. Under the same shading condition, the half-cell module still achieves a maximum power output of 166.96 W, accounting for 50.5% of its nominal value. Figure 6 and Figure 7 clearly illustrate the changes in the electrical output parameters of the modules resulting from variations in the shading strip size. Under high shading ratios, the superior power output performance of half-cell modules becomes particularly evident, which is a major factor contributing to their growing prevalence in the market.

Table 3.

Electrical parameters at maximum power point under vertical shading layout.

Figure 6.

I-V characteristic curves under vertical shading layout.

Figure 7.

P-V characteristic curves under vertical shading layout.

Furthermore, when the shading strip height increases to 125%, the results remain largely consistent with those at 100%, showing only minor variations. In practical applications, the proportion of dust accumulation is less than 100%. These experimental results clearly indicate a significant strategy for enhancing the power generation efficiency of PV power stations: promptly removing dust buildup along the edges of the modules. In addition, the analysis indicates that in scenarios lacking mechanized regular cleaning, it is essential to use half-cell modules and to install the PV arrays in a vertical installation configuration.

3.2. Horizontal Shading Configuration

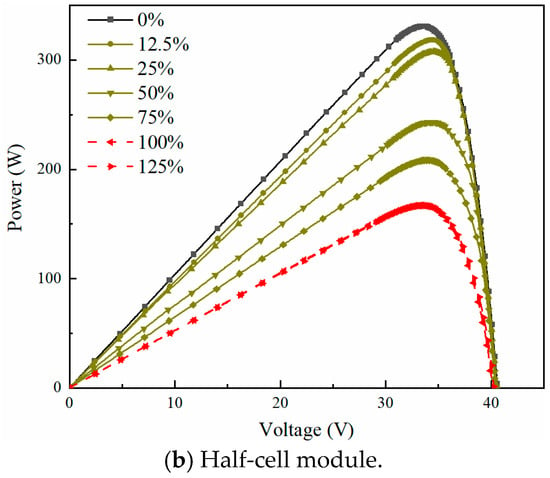

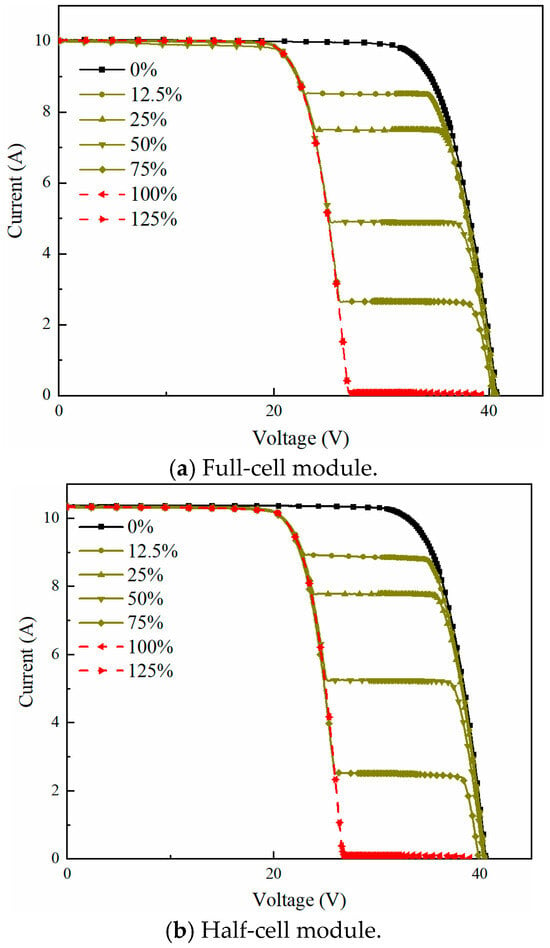

The actual layout of PV arrays is often constrained by factors such as available space, terrain, and land-use efficiency, which may necessitate horizontal installation configurations. For this installation configuration, a corresponding shading strip scheme was developed, as illustrated in Figure 5. The test results under this shading condition are summarized in Table 4 and Figure 8 and Figure 9. Without shading strips, the maximum output power of the full-cell and half-cell modules is 316.75 W and 330.88 W, respectively. When the shading ratio reaches 12.5%, the global maximum power drops to 292.48 W for the full-cell module and 306.33 W for the half-cell module, with power losses remaining within 8%. As the shading ratio increases to 25%, the output power further declines to 265.07 W and 275.76 W for the full-cell and half-cell modules, respectively, corresponding to an approximate attenuation of 16%.

Table 4.

Electrical parameters at local maximum power point under horizontal shading layout.

Figure 8.

I-V characteristic curves under horizontal shading layout.

Figure 9.

P-V characteristic curves under horizontal shading layout.

As shown in Table 4 and Table 5, the most notable difference in output characteristics compared to the vertical configuration is the occurrence of both a local maximum and a global maximum in the output parameters. Theoretical analysis suggests that this phenomenon results from the parallel orientation of the cell interconnections and the shading strips, making it an inevitable outcome. In current PV modules, the internal cells are divided into three groups, each connected in reverse and parallel with a bypass diode. When half of the cells in one group are shaded and the shading ratio exceeds 12.5%, that group becomes short-circuited. Consequently, one-third of the cells are bypassed, and the voltage across them approaches zero, resulting in an approximate 33% reduction in output voltage. From Figure 9, it is also observed that, for both full-cell and half-cell modules, the local maximum output power remains nearly constant when the shading ratio varies between 12.5% and 125%. The variation pattern of the global maximum power is generally consistent with that observed under the vertical shading configuration. When the shading ratio reaches 100%, the maximum output power drops to zero. Theoretical analysis and experimental results under this condition demonstrate that the half-cell modules fail to perform effectively, and dust accumulation can severely compromise power generation efficiency. This scenario should be avoided whenever possible. It is strongly recommended that such an installation configuration not be used for half-cell modules.

Table 5.

Electrical parameters at maximum power point under horizontal shading layout.

In conclusion, the multi-peak characteristic of PV modules is observed in the horizontal shading experiment. This characteristic increases the difficulty of maximum power point tracking (MPPT) in PV power stations, potentially leading the system to settle on a local power maximum instead of the global maximum power point. Furthermore, the vertical shading experiment revealed that dust shades the full-cell module, resulting in a more substantial power reduction. By contrast, half-cell modules display superior capabilities of power maintenance in both shading scenarios, with a notable advantage under vertical shading conditions. The experiment also indicates that half-cell modules can significantly enhance the power generation capacity and operational robustness of PV power stations under complex lighting environments. While mainstream half-cell modules mitigate the shading effect to some degree, their dust shading resistance performance can be further improved through optimization of the module structure.

4. Exploration of Structural Optimization of PV Modules

Obviously, dust shading will lead to a sharp decline in the power generation capacity of PV modules, which is the most important reason for the actual power generation of some PV power stations with severe dust shading being seriously lower than the expected value. For small-scale distributed rooftop PV systems, due to limited location space and more difficult surface cleaning, PV modules cannot be cleaned for a long time, and long-term dust accumulation will paralyze the power generation capacity of PV modules. In order to weaken the dust shading effect, various targeted measures have been proposed. However, due to the inertia of industrial production, this issue has not received the attention it deserves.

The division of PV power generation application fields is becoming increasingly refined, and the targeting of module characteristics is becoming stronger. For rooftop distributed PV power stations, the dust shading at the lower end of vertically installed full-cell components will cause a severe drop in the output power, making full-cell components increasingly infeasible for rooftop PV power stations. Therefore, it is essential to develop novel PV modules with superior performance. Based on the results of this experimental investigation and long-term experience, two novel types of PV modules were designed.

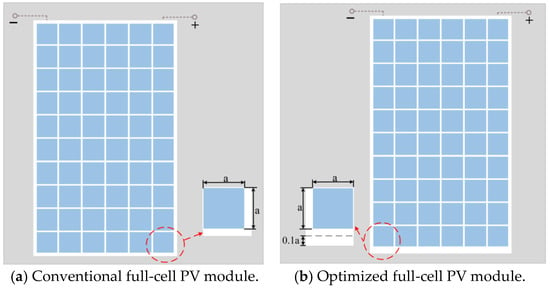

4.1. Asymmetric Structure of Full-Cell Module Is Worth Promoting

The main improvement measure is to increase the length of the long side of the PV module by about 0.1 times the side length of the solar cell. The specific layout is shown in Figure 10. Although no solar cells are installed in this increased area and it has no power generation function, it can play an important role in practical applications: the accumulation of dust in this area will not cause a shading effect on the PV system. This measure essentially provides a shading buffer zone. For PV modules with such a buffer zone, when installed vertically with the buffer zone placed at the bottom, the actual shaded height of cells is only 0.125 a when the accumulated dust reaches a height of 0.225 a. The corresponding power reduction is merely around 5%, which is much lower than the 10% observed in modules without this buffer zone. It can be anticipated that this solution will bring considerable increases in power generation, while the additional cost of module production is minimal. Its cost-effectiveness is remarkably prominent, and the product will have a viable market. It is recommended to promote this design and application in existing low-end products.

Figure 10.

Front-view schematic for the structure of the full-cell photovoltaic modules.

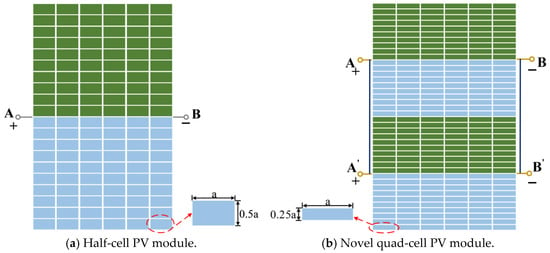

4.2. Development of Novel Quad-Cell Module

The experimental research in this paper shows that, in the vertical installation scenario, when the shading strip width reaches 100%, the entire component almost loses its power generation capacity, while the half-cell module retains 50% of its power. The most intuitive explanation for this phenomenon is that the half-cell module is divided into two completely identical subunits, where the lower subunit is affected by the shading strip and its power drops to zero, while the upper subunit is not subject to shading restrictions and its power can be fully output. The sum of the two results in retaining half of the power. We can divide the solar cell into four long strips, where the long side of each sub-cell becomes a, and the short side becomes 0.25a. These sub-cells are then connected in series to form four submodule units, and then the four submodule units are connected in parallel to form a novel quad-cell module. The specific layout is shown in Figure 11. Theoretical analysis reveals that, under the same shading conditions, its power will remain above 75% of the maximum power, and the efficiency enhancement results will be very significant.

Figure 11.

Front-view schematic for the structure of the half-cell and quad-cell PV modules.

Moreover, the layout of this novel quad-cell structure module is very conducive to the implementation of an automated production line for the module. The increase in production processes is not significant, and the increase in product cost is also very limited. However, for small-scale distributed PV power stations lacking cleaning conditions, the effects of power reduction and loss prevention will be very obvious. This novel structural module has been granted a national authorization patent, and we believe that this module is worthy of large-scale promotion and application.

5. Conclusions

Dust accumulation on PV modules significantly impairs the annual power generation of PV systems. Effectively addressing the dust accumulation effect has become a critical link in achieving “cost reduction and efficiency improvement” that cannot be overlooked. In this study, a large-scale engineering test system was employed to systematically investigate the influence laws of edge shading on full-cell and half-cell modules for the first time. The key conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- When shading strips are vertically placed on the modules and the shading height reaches 50% of the solar cell side length, the power of full-cell modules decreases by approximately 42%, while that of half-cell modules only drops by 27%. When the shading ratio reaches 100%, the output power of full-cell modules declines by about 99%, almost losing their power generation capacity, whereas half-cell modules can still maintain nearly 50% of their rated power. These results demonstrate that the dust accumulation resistance of half-cell modules is significantly superior to that of full-cell modules.

- (2)

- When shading strips are horizontally placed on the modules, the power attenuation trends of full-cell and half-cell modules are similar. At shading ratios of 25% and 50%, the power attenuation is approximately 16% and 36%, respectively.

- (3)

- When PV modules are installed horizontally, their output power exhibits multi-peak characteristics. This poses a dilemma for PV inverters, as they may become trapped in local maxima, which significantly degrades system performance and operational stability. Therefore, horizontal installation is not recommended for PV arrays.

- (4)

- Based on experimental results and theoretical analysis, two novel module designs are proposed: asymmetric full-cell modules and quad-cell PV modules. These designs can effectively reduce power losses caused by edge dust accumulation, improve the annual power generation of PV modules, and provide theoretical and technical support for the stable operation of PV systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. (Jicheng Zhou); Methodology, J.Z. (Jicheng Zhou); Software, X.Z. and J.Z. (Jicheng Zhou); Validation, L.H. and A.Y.; Formal analysis, L.H. and J.Z. (Jicheng Zhou); Investigation, X.Z., A.Y. and J.Z. (Jicheng Zhou); Resources, G.Z. and J.Z. (Jicheng Zhou); Data curation, X.Z., A.Y., J.Z. (Jianyong Zhan) and G.Z.; Writing—original draft, L.H., X.Z., X.Y. and J.Z. (Jicheng Zhou); Writing—review & editing, J.Z. (Jianyong Zhan) and J.Z. (Jicheng Zhou); Supervision, J.Z. (Jicheng Zhou); Project administration, J.Z. (Jicheng Zhou); Funding acquisition, J.Z. (Jicheng Zhou). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dongguan Science and Technology of Social Development Program (Grant no. 20231800940252), Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant no. 2022JJ60059), and Natural Science Project of Guangdong University of Science and Technology (Grant no. GKY-2024KYZDK-4, GKY-XJ2024009601).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baumgartner, F.; Allenspach, C.; Özkalay, E.; Berwind, M.; Heimsath, A.; Bucher, C.; Joss, D.; Golroodbari, S.M.; van Sark, W.; Granlund, A.; et al. Performance of Partially Shaded PV Generators Operated by Optimized Power Electronics; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, H.; Li, X.; Guo, C.; Luo, W.; Jia, R. The Mechanism of Hot Spots Caused by Avalanche Breakdown in Gallium-Doped PERC Solar Cells. Energies 2023, 16, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, J.; Peled, A.; Aronescu, A. Wall Shading Losses of Photovoltaic Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 5089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Li, Z.; Sun, Z.; Xu, J.; Long, H.; Sun, T. Low Resistance Hot-Spot Diagnosis and Suppression of Photovoltaic Module Based on IU Characteristic Analysis. Energies 2022, 15, 3950. [Google Scholar]

- Craciunescu, D.; Fara, L. Investigation of the partial shading effect of photovoltaic panels and optimization of their performance based on high-efficiency FLC algorithm. Energies 2023, 16, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Iysaouy, L.; Lahbabi, M.; Bhagat, K.; Azeroual, M.; Boujoudar, Y.; El Imanni, H.S.; Aljarbouh, A.; Pupkov, A.; Rele, M.; Ness, S. Performance enhancements and modelling of photovoltaic panel configurations during partial shading conditions. Energy Syst. 2023, 16, 1143–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, N.; Singh, S.K.; Kumar, S.; Jadoun, V.K. Performance analysis of partially shaded high-efficiency mono PERC/mono crystalline PV module under indoor and environmental conditions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21587. [Google Scholar]

- Alabdali, Q.A.; Bajawi, A.M.; Nahhas, A.M. Review of recent advances of shading effect on PV solar cells generation. Sustain. Energy 2020, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Pareek, S.; Ansari, F.; Khurana, N.; Nezami, M.; Alharbi, S.S.; Alharbi, S.S.; Krishan, G.; Dahiya, R.; Khan, M.J. Performance comparison of interconnection schemes for mitigating partial shading losses in solar photovoltaic arrays. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, F.; Mirhosseini, M. Shading impact modeling on photovoltaic panel performance. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 212, 115432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin-Ugranlı, H.G. Photovoltaic System Performance Under Partial Shading Conditions: Insight into the Roles of Bypass Diode Numbers and Inverter Efficiency Curve. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkalay, E.; Valoti, F.; Caccivio, M.; Virtuani, A.; Friesen, G.; Ballif, C. The effect of partial shading on the reliability of photovoltaic modules in the built-environment. Epj Photovolt. 2024, 15, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Al Mahdi, H.; Leahy, P.G.; Alghoul, M.; Morrison, A.P. A review of photovoltaic module failure and degradation mechanisms: Causes and detection techniques. Solar 2024, 4, 43–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummalieh, A.; Mittag, M.; Reichel, C.; Protti, A.; Neuhaus, H. Holistic Analysis for Mismatch Losses in Photovoltaic Modules: Assessing the Impact of Inhomogeneity from Operational Conditions and Degradation Mechanisms on Power and Yield. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2025, 0, 1–21, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.C. Principles of Photovoltaic Cells; Chemical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2021; Volume 7, p. 193. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.; Kang, Y. Reliability study on the half-cutting PERC solar cell and module. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Tobar, A.; Dolara, A.; Leva, S.; Mazzeo, D.; Ogliari, E. Comparative analysis of half-cell and full-cell PV commercial modules for sustainable mobility applications: Outdoor performance evaluation under partial shading conditions. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 71, 103981. [Google Scholar]

- Siow, C.H.; Tan, R.H.G.; Babu, T.S. Modeling and comparative study of half-cut cell and standard cell photovoltaic modules under partial shading conditions. In Performance Enhancement and Control of Photovoltaic Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Pratama, B.A.; Hiendro, A.; Marpaung, J.; Yusuf, M.I.; Imansyah, F. Effect of Shading on Half-Cut Solar Panels Power Output. Telecommun. Comput. Electr. Eng. J. 2023, 1, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merodio, P.; Martínez-Moreno, F.; Lorenzo, E. Experimental determination of the structure shading factor and mismatch losses for bifacial photovoltaic modules on variable-geometry, single-axis trackers. Sol. Energy 2025, 291, 113400. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, M.H.; Khan, N.M.; Mirza, A.F.; Mansoor, M.; Akhtar, N.; Qadir, M.U.; Khan, N.A.; Moosavi, S.K.R. A new meta-heuristic optimization algorithm based MPPT control technique for PV systems under complex partial shading condition. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 47, 101367. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, M.Y.; Murtaza, A.F.; Ling, Q.; Qamar, S.; Gulzar, M.M. A new MPPT design using generalized pattern search for partial shading. Energy Build. 2016, 133, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, L.G.K.; Gopal, L.; Juwono, F.H.; Chiong, C.W.; Ling, H.-C.; Basuki, T.A. A new global MPPT technique using improved PS-FW algorithm for PV system under partial shading conditions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 246, 114639. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, S.; Javed, M.Y.; Jaffery, M.H.; Arshad, J.; Rehman, A.U.; Shafiq, M.; Choi, J.-G. A new hybrid MPPT technique to maximize power harvesting from PV system under partial and complex partial shading. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 587. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, A.R.; Hefny, M.M.; Ali, A.I.M. Investigation of single and multiple MPPT structures of solar PV-system under partial shading conditions considering direct duty-cycle controller. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19051. [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi, A.; Abo-Khalil, A.G.; Sayed, K.; Albagami, N. MPPT for a PV grid-connected system to improve efficiency under partial shading conditions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worku, M.Y.; Hassan, M.A.; Maraaba, L.S.; Shafiullah; Elkadeem, M.R.; Hossain, I.; Abido, M.A. A comprehensive review of recent maximum power point tracking techniques for photovoltaic systems under partial shading. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Meng, F.; Liu, Z. Experimental investigation of the shading and mismatch effects on the performance of bifacial photovoltaic modules. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2019, 10, 296–305. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov, P.N.; Abd, A.L.M.; Kuvshinov, V.V.; Issa, H.A.; Mohammed, H.J.; Al-Bairmani, A.G. Investigation of the losses of photovoltaic solar systems during operation under partial shading. J. Appl. Eng. Sci. 2020, 18, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klasen, N.; Weisser, D.; Rößler, T.; Neuhaus, D.H.; Kraft, A. Performance of shingled solar modules under partial shading. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2022, 30, 325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Afridi, M.Z.U.A. Module Level Power Electronics and Photovoltaic Modules: Thermal Reliability Evaluation. Ph.D. Thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Song, Y.; Qiao, S.; Liu, D.; Ding, Z.; Kopecek, R.; Chen, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, M. Design, realization and loss analysis of efficient low-cost large-area bifacial interdigitated-back-contact solar cells with front floating emitter. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2022, 235, 111466. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan, M.A.S. Modeling Half-Cut Photovoltaic Modules with Bypass Diodes Under Various Shading Conditions. Master’s Thesis, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, S.; Javed, M.Y.; Jaffery, M.H.; Ashraf, M.S.; Naveed, M.T.; Hafeez, M.A. Modular level power electronics (MLPE) based distributed PV system for partial shaded conditions. Energies 2022, 15, 4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakshinamoorthy, M.; Sundaram, K.; Murugesan, P.; David, P.W. Bypass diode and photovoltaic module failure analysis of 1.5 kW solar PV array. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2022, 44, 4000–4015. [Google Scholar]

- Olalla, C.; Hasan, N.; Deline, C.; Maksimović, D. Mitigation of hot-spots in photovoltaic systems using distributed power electronics. Energies 2018, 11, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eum, J.; Park, S.; Choi, H.J. Effects of power optimizer application in a building-integrated photovoltaic system according to shade conditions. Buildings 2023, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinapis, K.; Tzikas, C.; Litjens, G.B.M.A.; van den Donker, M.; Folkert, W.; van Sark, W.G.J.H.M.; Smets, A. Yield modelling for micro inverter, power optimizer and string inverter under clear and partially shading shaded conditions. In Proceedings of the 31st European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference, Hamburg, Germany, 14–18 September 2015; pp. 1587–1591. [Google Scholar]

- GB2760-2014; Standard Tables for Reference Solar Spectral Irradiances: Direct Normal and Hemispherical on 37° Tilted Surface. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).