Abstract

Recent comprehensive research (2023–2024) on basalt fiber-reinforced composites (BFRCs) has meticulously documented significant progress across diverse applications, including protective coatings, high-performance concrete, reinforcement bars, and advanced laminates. The central theme of these developments revolves around innovative composite design strategies that strategically incorporate basalt fibers to markedly enhance mechanical properties, durability, and protective capabilities against environmental challenges. Key advancements in synthesis methodologies highlight that the integration of BFs substantially improves abrasion and corrosion resistance, effectively inhibits crack propagation through superior fiber-matrix bonding, and confers exceptional thermal stability, with composites maintaining structural integrity at temperatures of 600–700 °C and demonstrating short-term resistance exceeding 900 °C. The underlying mechanisms for this enhanced performance are attributed to both chemical modifications—such as the application of silane-based coupling agents which improve interfacial adhesion—and physical–mechanical interlocking between the fibers and the matrix. These interactions facilitate efficient stress transfer, leading to a breakthrough in the overall multifunctional performance of the composites. Despite these promising results, the field continues to grapple with challenges, particularly concerning the long-term durability under sustained loads and harsh environments, and a notable lack of standardized global testing protocols hinders direct comparison and widespread certification. This review distinguishes itself by offering a critical synthesis of the latest findings, underscoring the immense application potential of BFRCs in critical sectors such as civil engineering for seismic retrofitting and structural strengthening, the automotive industry for lightweight yet robust components, and advanced passive fireproofing systems. Furthermore, it emphasizes the growing, innovative role of simulation techniques like finite element analysis (FEA) in predicting and optimizing the performance and design of these composites, thereby providing a robust scientific foundation for developing the next generation of high-performance, sustainable structural components.

1. Introduction

The realm of composites has witnessed some significant advancements in recent years, with researchers exploring innovative approaches to enhance durability and performance [1,2,3,4]. Among these approaches, the incorporation of basalt fibers (BFs) into composites has gained considerable attention [5,6,7,8]. Unlike previous reviews that often focused broadly on material properties, this work provides a focused critical analysis of recent developments (2023–2024) in BF-reinforced composites, particularly in coatings, concrete, and rebars, highlighting their synergistic effects and application-specific performance. Composites are crucial for preserving the integrity and lifespan of various structures, from marine environments to industrial machinery. The constant evolution of composite technologies seeks to address challenges such as environmental degradation, high temperature and chemical exposure, and mechanical stress [9,10,11,12]. For instance, composite foam concrete with basalt reinforcing mesh has been successfully applied in the construction industry of Central Europe [13]. The integration of BFs represents a promising avenue for enhancing the robustness of composites.

Basalt fibers (BFs), derived from volcanic rock, possess exceptional mechanical and thermal properties. The decision to reinforce composites with BFs stems from their high tensile strength, resistance to chemical corrosion, and thermal stability [4,14,15]. Xie et al. reported that an appropriate BF content (0.39%) can effectively improve the tensile strength and crack resistance of concrete [16]. Wang et al. studied the mass loss and strength change in the BFs after being boiled in distilled water, sodium hydroxide, and hydrochloric acid, respectively, and found that the alkali resistance of the BF was better than acid resistance [17]. Cui et al. revealed that BFs could enhance the mechanical properties, flame retardancy, and thermal stability of polypropylene (PP) [18]. Given its far superior cost-effectiveness, glass fibers (GFs) maintain a dominant position in mass-market applications. In contrast, the underdeveloped supply chain for basalt fiber restricts its use primarily to niche, high-performance markets [19,20,21].

Although glass fibers (GFs) share a similar chemical composition with BFs, the latter have not been as widely applied. However, both glass and basalt fibers have been successfully used in constructing and rehabilitating asphalt pavements recently. Therefore, this paper provides a critical overview of recent developments in BF-reinforced composites, summarizing cutting-edge approaches to enhance their protective and mechanical properties. It emphasizes the integration of BFs and their impact on wear resistance, crack mitigation, and high-temperature resistance, exploring the chemical modification and mechanical interactions behind their superior performance. The review concludes by acknowledging the potential applications of BF-reinforced composites in diverse industries, showcasing their promising future in providing robust and durable solutions. It also critically examines the limitations regarding long-term durability and puts forward future prospects, including ongoing research and standardization, to expand the application of BFs and further prolong the service life of BF-based composites.

2. Properties of BF

2.1. Chemical Composition

BF possesses a unique chemical composition that contributes to its exceptional mechanical and thermal properties [22,23,24]. As shown in Table 1, the primary constituents of BFs are SiO2, Al2O3, MgO, CaO, and smaller amounts of other oxides. SiO2 is the predominant component in BFs, constituting a significant portion of the material’s chemical composition with about 47–55 wt.%. Al2O3 enhances the fibers’ mechanical strength and stability, making them suitable for various applications, including reinforcement in composites [25]. While the content of Fe2O3/FeO is relatively low, it can influence the fibers’ thermal and magnetic properties [26]. BFs may also contain minor amounts of CaO and other oxides. These components can influence specific properties of the fibers, such as their adhesion to matrices in composite materials.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of glass and basalt fibers [1,27].

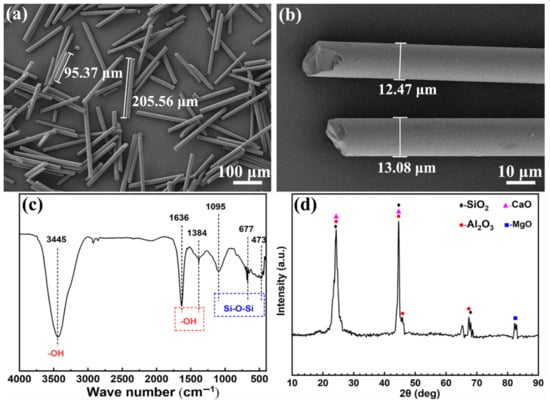

In the previous work [28], we found that the surface of the primitive BFs was smooth without foreign matter attachment, attached with inorganic groups such as -OH and Si-O-Si, and its surface material composition contained SiO2, CaO, Al2O3, MgO, and Fe2O3/FeO, as shown in Figure 1. The above discoveries about chemical and physical properties of BFs’ surface were consistent with previous reports by others [29,30,31].

Figure 1.

Surface morphologies of (a) basalt fibers at low magnification: 100× and (b) basalt fibers at high magnification: 1000×. (c) FT-IR spectrum of basalt fibers. (d) XRD spectrum of basalt fibers. Reprinted from Ref. [28] with permission from Elsevier.

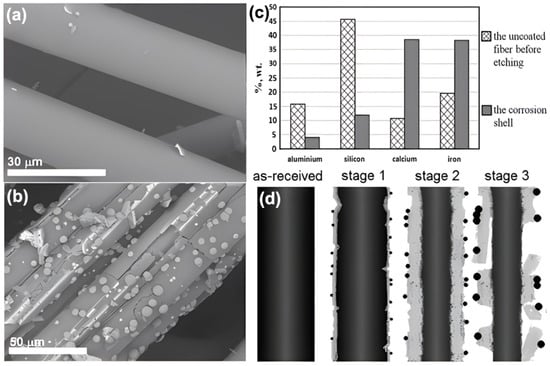

In the material composition of the BF surface, the mass ratio of acid oxide SiO2 is about 50 wt.%, which means that the BF surface could be eroded by alkali. Baklanova et al. [29] found that raw BFs could be eroded by alkali solution with concentration of 2.0 mol/L at ambient temperature during a definite period of time (8, 16, 32, and 64 days), and the main substance corroded off the BF surface was SiO2, where the corrosion went through three stages, which were corrosion of shell, mechanical stress concentration at the interface, and finally exfoliation of the broken-shell, as seen in Figure 2a,c,d. They have also concluded that zirconia coating could improve corrosion resistance of BFs in alkali solution, as seen in Figure 2b.

Figure 2.

The ZrO2 (0.4 mol/L sol)-coated basalt fiber etched in alkali solution for different periods of time: (a) 8 days and (b) 64 days. (c) EDS data on elemental composition of the corrosion shell. (d) Scheme of corrosion of basalt fiber in NaOH solution. Reprinted from Ref. [29] with permission from Elsevier.

2.2. Mechanical Properties

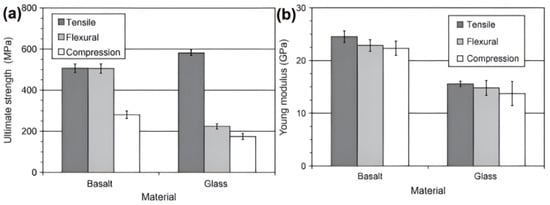

BFs’ mechanical properties make them a remarkable and sought-after material for various engineering applications [32,33,34]. BFs exhibit impressive tensile strength, making them suitable for applications where materials must endure significant pulling or stretching forces. The high tensile strength contributes to the reinforcement capabilities of BFs in composites and construction materials. They also demonstrate excellent flexural strength and stiffness, and rigidity, allowing them to withstand bending and deformation without compromising their structural integrity. Another widely used fiber, glass fiber (GF), has a similar material composition to BF, so it is necessary to compare the mechanical properties of the two fibers. As seen in Table 2, as compared with GFs, BFs perform the better mechanical properties, lower heat conductivity and higher melting, and show much less mass loss after being immersed in alkali and acid solutions because the surface of BFs have an equal ratio of acidic and basic oxides, while the surface of GFs have more acidic oxides, as seen in Table 1.

Table 2.

The properties of glass and basalt fibers.

As studied by Lopresto et al. [44], the ultimate strengths of BF and GF were slightly different only in the tensile data, where GF composites showed a better property, but for Young’s modulus, BF showed 35%–42% higher values compared to the tested GF counterpart, as shown in Figure 3. Among these, E-glass fiber is the most prevalent type of glass fiber, with the ‘E’ denoting its outstanding electrical insulation properties. Its classification as an “alkali-free” glass stems from a very low content of alkali metal oxides (e.g., K2O, Na2O), typically under 1%, which is essential for maintaining high chemical stability, mechanical strength, and electrical resistance. As the industry standard, E-glass fiber acts as the fundamental performance and cost benchmark against which new reinforcing fibers, such as basalt fiber, are routinely compared. Understanding these mechanical properties positions BFs as a versatile and reliable material for a wide range of applications, including reinforcing composites, manufacturing durable textiles, and enhancing the performance of various structural components [45,46,47]. The combination of high strength, rigidity, and resistance to environmental factors makes BFs an increasingly popular choice in engineering and construction contexts.

Figure 3.

Comparison of tensile, flexural, and compressive properties between basalt and E-glass fiber composites of (a) ultimate strength and (b) Young’s modulus. Reprinted from Ref. [44] with permission from Elsevier.

2.3. Thermal Properties

BFs exhibit notable thermal properties that contribute to their versatility and applicability in diverse industries [18,48]. As reported by the literature [31,40,41,42], BFs display low heat conductivity (0.03 w/m·k) and high melting point (1250 °C), which make BFs exhibit inherent fire resistance, adding to their appeal in applications requiring materials with excellent flame-retardant properties, which are crucial in sectors such as construction, where BFs can be incorporated into fire-resistant composites [49,50]. Also, Mhaske et al. [40] stated that BFs perform the low coefficient of thermal expansion, which could maintain stability at temperatures as high as 600 °C to 700 °C.

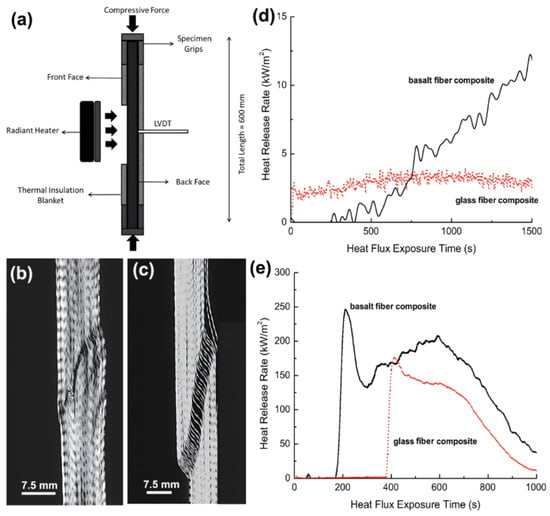

BFs have a high resistance to elevated temperatures, making them suitable for applications where exposure to heat is a concern, which is particularly advantageous in industries such as aerospace, automotive, and fire-resistant materials [49,50]. Mouritz et al. [51] studied the fire resistance and high temperature resistance of BF with the device in Figure 4a; the out-of-plane deflections of the samples were measured using a linear variable differential transformer (LVDT) attached to the back surface. The result found that the BF laminate released heat sooner and showed obviously higher values than the GF laminate, meaning that BF showed a bigger heat release rate, as seen in Figure 4d,e. And the rapid heat release ensured better structural stability of BF, showing slight buckling, as shown in Figure 4b,c. Overall, the impressive thermal properties of BFs make them a valuable material in various sectors, ranging from aerospace and automotive engineering to construction and manufacturing.

Figure 4.

(a) Schematic of the fire resistance test for basalt fiber-based composites. X-ray computed tomography images of compressive failure of the basalt laminate loaded to (b) 80% and (c) 20% of the room temperature Euler buckling load and exposed to the heat flux. Heat release rate of the laminates at the heat flux of (d) 25 kW/m2 and (e) 50 kW/m2. Reprinted from Ref. [51] with permission from Elsevier.

3. Effects in Composites

3.1. Traditional vs. Reinforced Composites

Comparing traditional composites with those reinforced with BFs reveals significant differences in performance, durability, and application versatility. Here are several breakdowns of the key distinctions between traditional composites and those enhanced with BFs.

3.1.1. Mechanical Strength

Traditional composites often rely solely on their inherent properties:

- (1)

- In traditional epoxy coatings, the corrosion protection and mechanical strength are primarily dictated by the cured epoxy resin itself, which is often brittle and possesses limited intrinsic resistance to crack propagation.

- (2)

- In plain concrete, the tensile strength and crack resistance are inherently low, dependent almost exclusively on the properties of the cement paste and aggregate, leading to a quasi-brittle failure mode.

- (3)

- In unreinforced thermoplastics like polypropylene (PP), the thermal stability and flame retardancy are intrinsic to the polymer, which typically softens at relatively low temperatures and is highly flammable. In contrast, BF-reinforced composites introduce a high-performance reinforcing phase that actively enhances and transcends these inherent limitations.

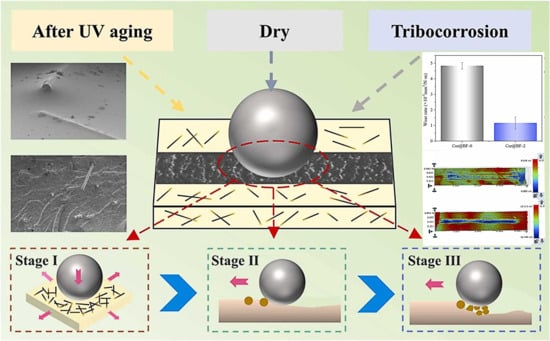

While they may provide a degree of protection, their mechanical strength may be limited. As for BF-reinforced composites, the incorporation of BFs significantly enhances mechanical strength. The fibers act as a reinforcement, improving the overall structural integrity of the composite, which makes BF-reinforced composites more robust and resistant to mechanical stresses [52,53]. As shown in Figure 5, Fan et al. [54] verified that evenly dispersed BFs can offer the interior/exterior enhancement under drying, corrosion, and UV aging, and the epoxy composite coating with 2 wt.% BFs performed the optimal tribological properties, in which the wear rate after friction in brine was reduced by 76.03% as compared with pure epoxy.

Figure 5.

The diagram of chopped basalt fibers to enhance the tribological properties of epoxy coating. Reprinted from Ref. [54] with permission from Elsevier.

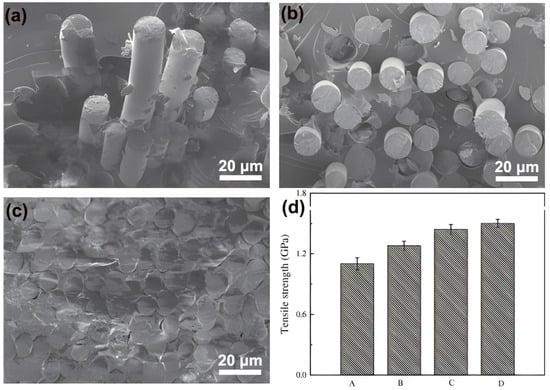

Wei et al. [55] studied the tensile strength of BF-reinforced epoxy composite coating and found that BF significantly improved the tensile strength of composite coating. However, the BFs without surface treatment were agglomerated inside the coating, as shown in Figure 6a, and the coating of SiO2 nanoparticles helped to improve the dispersion of the fibers and enhance the fiber/resin interface properties, as shown in Figure 6b,c. The increase in dispersibility and interfacial compatibility of the fiber further improved the tensile strength of the composites, as seen in Figure 6d.

Figure 6.

Fracture surface morphologies of basalt fiber-based coatings of (a) basalt fibers with coating not containing SiO2, (b) basalt fibers with coating containing untreated SiO2, and (c) basalt fibers with coating containing treated SiO2. (d) Tensile strength of basalt fibers of (A) untreated basalt fibers, (B) basalt fibers with coating not containing SiO2, (C) basalt fibers with coating containing untreated SiO2, and (D) basalt fibers with coating containing treated SiO2. Reprinted from Ref. [55] with permission from Elsevier.

3.1.2. Temperature Resistance

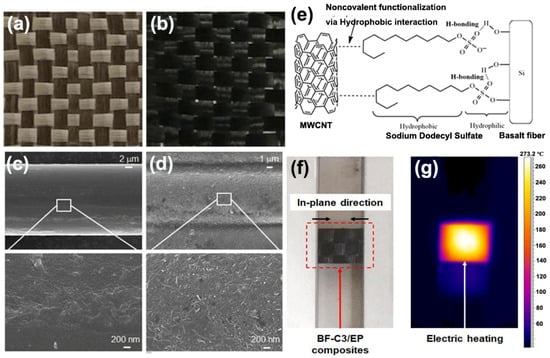

Traditional composites may have limitations in terms of temperature resistance. High temperatures can lead to degradation and reduced effectiveness of the composites [53]. BFs excel in high-temperature resistance. When integrated into composites, they contribute to the overall thermal stability of the systems, making BF-reinforced composites particularly suitable for applications where exposure to elevated temperatures is a concern [49,56]. Alaskar et al. tested the high temperature resistance of BF-reinforced concrete when exposed to elevated temperature and found that reinforced concretes with 0.25 wt.%, 0.5 wt.%, 0.75 wt.%, and 1.0 wt.% maintained the high strength and energy absorption when exposed to temperatures of up to 600 °C. At high temperature, the evaporation of bound water led to the additional stress and then micro-cracks inside the concrete, where the high-temperature resistant BFs could hold the location of the aggregate inside concrete and then prevent the expansion of cracks. Rhee et al. [57] and Jeong et al. [58] found that BFs were resistant to high temperature (>900 °C), so BFs could be utilized as excellent reinforcing components for fireproof fabrics for high-performance fiber-reinforced polymer composites, as seen in Figure 7a. Further, as shown in Figure 7b–g, Jeong et al. [58] investigated the deposition of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) on the surface of BFs and found that MWCNT-coated BFs composites showed excellent electrothermal response in terms of rapid temperature rise, high steady-state maximum temperature, and high thermal performance.

Figure 7.

Digital images of (a) basalt fibers and (b) MWCNT-coated basalt fibers. SEM images of the (c) raw and (d) MWCNT-coated basalt fiber. (e) Illustration of the interactions between basalt fibers and MWCNT. (f) Digital and (g) infra-red images of basalt fibers epoxy composite. Reprinted from Ref. [58] with permission from Elsevier.

3.1.3. Flexibility and Crack Resistance

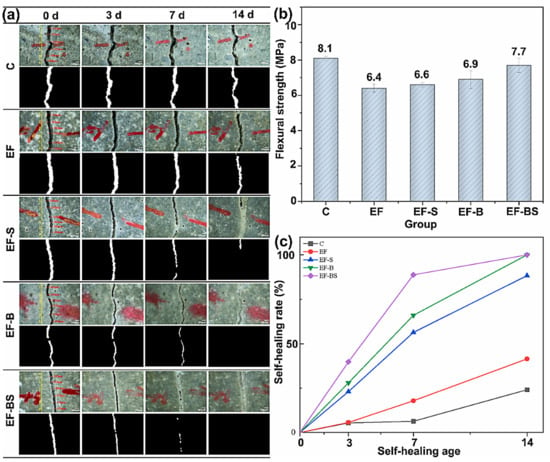

BFs enhance the flexibility of composites, making them more resistant to cracking, which is particularly advantageous in applications where flexibility and durability are crucial, such as in construction or infrastructure projects [59]. Wang et al. [60] reported that modifying the BFs with nano-SiO2 contributed to enhancing the interfacial compatibility between modified BFs and mortars, leading to BF-based mortars performing the obvious anti-cracking and even crack-healing abilities, as seen in Figure 8a,c. The experiment included five groups of mortar specimens, labeled C, EF, EF-S, EF-B, and EF-BS. C represents the control group of mortar specimens. The specimens with added expanded perlite and unmodified basalt fibers were named EF. In the EF-S specimens, expanded perlite and modified basalt fibers were added. EF-B represents specimens with added bacterial healing agents and unmodified basalt fibers. EF-BS indicates specimens with added modified basalt fibers and self-healing agents. All the mixtures had a water–cement ratio of 0.5 (W/C = 0.5). Also, the flexural strengths of BF-based mortars have increased with the help of tensile strength and elasticity modulus of BFs, as seen in Figure 8b.

Figure 8.

(a) Observed pictures of a series of basalt fiber-based composites of cracks at healing ages of 0, 3, 7, and 14 days. (b) Flexural strength after curing age of 28 days. (c) Crack self-healing rate during healing ages of 0, 3, 7, and 14 days. Reprinted from Ref. [60] with permission from Elsevier.

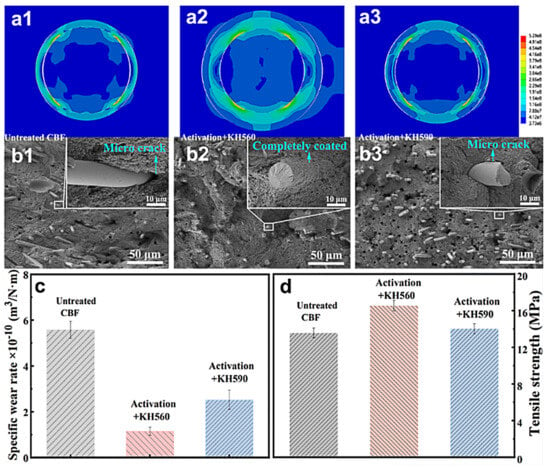

As shown in Figure 9, our team investigated the effects of surface modification on chopped basalt fiber (CBF)-reinforced waterborne epoxy (WEP) coatings [27]. The modification process involved activation followed by grafting with different silane coupling agents (SCAs), specifically KH550 (γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane), KH560 (γ-glycidyloxypropyltrimethoxysilane), KH570 (γ-methacryloxypropyltrimethoxysilane), and KH590 (γ-mercaptopropyltrimethoxysilane). We employed finite element analysis (FEA) to simulate the stress field distribution within the composites. Our results identified the KH560-modified layer as the most effective SCA, optimally enhancing crack resistance and reducing fiber debonding. The performance of the other SCAs followed the order KH570, KH550, and then KH590 [28].

Figure 9.

Investigation of various modified chopped basalt fiber-reinforced waterborne epoxy composites of (a1–a3) finite element analysis, (b1–b3) SEM of cross-section microstructures, (c) wear resistances, and (d) tensile strengths. Reprinted from Ref. [28] with permission from Elsevier.

In summary, the use of BF reinforcement in composites brings about notable improvements in mechanical strength, temperature resistance, chemical resistance, adhesion, and flexibility. These advantages position BF-reinforced composites as a technologically advanced and environmentally conscious alternative to traditional composites in various industrial applications.

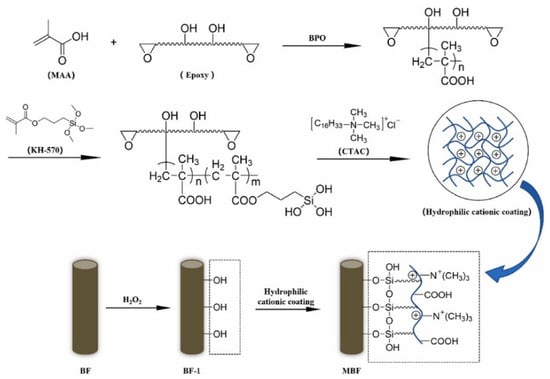

3.2. Integration with Composite Materials

The integration of BFs into various coating formulations, such as epoxy (EP), polyurethane, and acrylic systems, is a key aspect of their applications [53]. The integration process is crucial in maximizing the effectiveness of the BFs in enhancing the properties of the composites [52]. Uniform dispersion is critical because it ensures that every part of the coated surface benefits from the enhanced properties brought by the BFs, contributing to improved structural integrity and increased resistance to corrosion, which are vital for the longevity and durability of the coating [61]. Zhigang Peng et al. [62] employed a coating method to modify the surface of basalt fibers without damaging their inherent structure. The fibers were first treated with acetone to remove the surface wetting agent, followed by activation with hydrogen peroxide to enhance the reactivity of surface hydroxyl groups. The activated fibers were then immersed in a specially formulated hydrophilic cationic coating agent and dried to form the modified basalt fibers (MBFs). This coating agent significantly improved the surface charge and hydrophilicity of the fibers, thereby reducing fiber agglomeration and promoting a more uniform distribution within the cement matrix (Figure 10). As a result, the modified fibers more effectively transfer and disperse stress, leading to enhanced mechanical performance.

Figure 10.

A hydrophilic cationic coating agent was first synthesized through copolymerization and subsequently applied to surface-modified basalt fibers to produce the final modified product. Reprinted from Ref. [62] with permission from Elsevier.

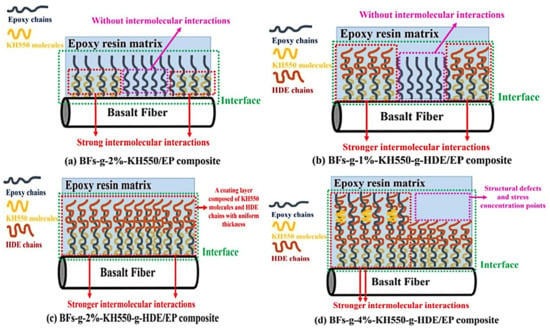

Furthermore, the good compatibility of BFs with various composite systems like epoxy, polyurethane, and acrylic is advantageous. The compatibility allows for a wide range of applications across different industries, from automotive to marine to construction [28,63,64]. The study of Wang et al. [60] explored the impact of modified fibers with nano-SiO2 on the interfacial compatibility of BFs and mortar, and confirmed that the nano-SiO2 coated on the surface of the BFs exhibited the pozzolanic reactivity and reacted with Ca2+ and OH− in the pore solution of the mortar to form stable C-S-H on the fiber surface, which improved the bonding strength of interface between the fibers and the cement slurry, and effectively improved the mechanical properties of the composites. As shown in Figure 11, Liu et al. [65] found that by grafting 3-amino-propyl triethoxysilane (KH550) molecules, BFs-KH550 had better compatibility with EP matrix, which not only promoted the infiltration between BFs and EP matrix, but also enhanced the intermolecular interaction between BFs and EP matrix and enhanced the interface adhesion.

Figure 11.

The illustration of interfacial adhesion between basalt fiber and epoxy matrix in composites. Reprinted from Ref. [65] with permission from Elsevier.

In summary, the successful integration of BFs into different composite formulations is a testament to their versatility and effectiveness. The meticulous mixing process that ensures uniform dispersion is key to unlocking the full potential of these fibers in improving the structural integrity and corrosion resistance of composites. The integration not only extends the lifespan of the composites but also broadens the scope of their applicability in various industries, offering a reliable solution for protecting a wide range of materials [53].

4. Applications in Industries and Limitations

4.1. Applications in Industries

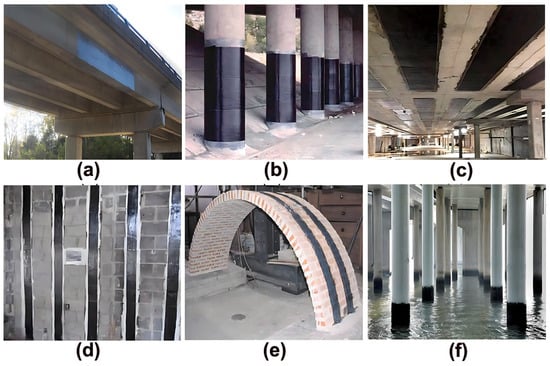

Industries across various sectors have recognized and embraced the substantial advantages offered by BF-reinforced composites. The unique properties of BFs contribute to enhanced performance, longevity, and protection in diverse applications. Here, we have explored several key industries that could significantly benefit from the application of BF-reinforced composites. In civil engineering field, the BF-based materials in the form of sheets or laminates have been used for retrofitting and strengthening the structures in concrete and masonry [33]. As shown in Figure 12a,b,e,f, on the outdoor engineering structure, such as the deck and pier of the bridge, the BF-based sheets and laminates can enhance the bearing capacity of the engineering structure and isolate the damage of the corrosive environment to the structure. However, the indoor engineering structures not only have load-bearing capacity, but also fire-resistant properties. For example, the masonry wall and roof of an underground garage (as seen in Figure 12c,d) and the interior silo of a ship have strict requirements on the fire-proof properties of the materials used in these spaces, according to ISO 5659 [66], ISO-1182, and ISO 9705-1 [67,68], so the BF-based materials with excellent fire resistance are more suitable for the structural enhancement of the indoor space environment. In the harsh and corrosive environment of marine and offshore structures, BF-reinforced composites play a pivotal role in providing robust protection against saltwater corrosion, abrasion, and impact [53,69]. Ship hulls, offshore platforms, and marine infrastructure benefit from the superior adhesion strength and durability imparted by these composites, leading to extended service life and reduced maintenance costs. BF-reinforced composites have emerged as a highly effective solution for protecting marine structures exposed to the corrosive elements of seawater. In demanding marine environments, where structures like piers, offshore platforms, and ship components are constantly subjected to saltwater corrosion, these composites offer unparalleled durability and resistance [53,70]. Also, the transportation industries, including automotive, aerospace, and railway applications, could benefit from BF-reinforced composites due to their exceptional impact resistance and flexibility. These composites enhance the durability of vehicle surfaces, protect against stone chips, and contribute to the longevity of components exposed to varying environmental conditions and mechanical stresses [49,50]. In oil and gas exploration and production, where equipment is exposed to corrosive environments and extreme temperatures, BF-reinforced composites offer a reliable solution. These composites provide durable protection against chemical corrosion and mechanical wear, enhancing the integrity of pipelines, tanks, and other components crucial to the industry. The oil and gas industry stands to gain substantial advantages from the adoption of BF-reinforced composites, particularly in the context of enhanced corrosion resistance and mechanical durability. Pipelines, which form the backbone of oil and gas transportation networks, are susceptible to corrosive forces due to the nature of the substances they convey and the environments they traverse. BF-reinforced composites act as a formidable defense against corrosion, providing a robust protective layer that shields the pipeline surfaces from the corrosive effects of transported fluids, soil conditions, and external elements [71,72] (Table 3).

Figure 12.

Applications of basalt fiber-based-reinforced polymer laminates and sheets in civil engineering of (a) bridge, (b) column, (c) interior architectures, (d) masonry wall, (e) masonry arches, and (f) pier. Reprinted from Ref. [33] with permission from Elsevier.

Table 3.

Summary of industrial applications of basalt fiber.

In summary, the versatility and superior performance of BF-reinforced composites make them invaluable across a spectrum of industries. Whether protecting maritime structures, transportation vehicles, energy infrastructure, or critical civil engineering projects, these composites consistently deliver enhanced durability, corrosion resistance, and mechanical strength, thereby contributing to the overall efficiency and longevity of diverse industrial applications.

4.2. Limitation of Long-Term Durability

The long-term durability of BF-reinforced composites remains a subject of ongoing research, highlighting the need for a comprehensive understanding of aging mechanisms and performance degradation over extended service periods. Investigating these aspects is crucial for accurately predicting and enhancing the composites’ lifespan, ensuring their sustained effectiveness in diverse applications [62]. In the realm of BF-reinforced composites, researchers are actively engaged in studying how these materials evolve over time under various environmental conditions and stressors. Aging mechanisms, including exposure to UV radiation, fluctuating temperatures, and mechanical stresses, are subjects of particular interest [73,74,75]. The work of Jumahat et al. [76] provided the insight on the effect of accelerated weathering, i.e., the combination of ultraviolet (UV) exposure and water spraying, on the visual and mechanical properties of BF-reinforced composites, and found that UV exposure and water absorption could reduce the tensile and flexural strengths. Zhu et al. [77] investigated the effectiveness of alkalinity on the durability of BF-reinforced bars to address their durability in the alkaline environment of seawater sea sand concrete (SWSSC) and found that degradation of interface of BF-reinforced bars embedded in lower alkalinity SWSSC was greatly mitigated by the reduction in alkalinity. By comprehensively assessing these parameters, researchers aim to provide insights into the long-term performance and reliability of these composites in real-world conditions. Predicting the lifespan of BF-reinforced composites requires not only an understanding of material behavior but also the development of models that can simulate aging processes over time.

5. Modeling and Simulation Advances

Computational modeling has become an indispensable tool that complements experimental studies in BF composite research, providing deeper insights into material behavior and enabling predictive design. This section reviews key developments in this area.

At the micro-mechanical scale, research has primarily focused on understanding stress transfer and failure mechanisms at the fiber–matrix interface. Finite element analysis (FEA) has proven particularly valuable for this purpose. In previous work [28], FEA successfully simulated stress field distribution in chopped BF-reinforced epoxy coatings, demonstrating how different silane coupling agents affect stress concentration and interface performance. This approach confirmed KH560 as the most effective modification for reducing stress concentrations and minimizing debonding risk. Other researchers have similarly employed micro-mechanical models to analyze how fiber orientation, volume fraction, and interfacial strength influence composite properties and damage initiation [78,79].

At the macro-mechanical scale, modeling efforts focus on predicting the behavior of BF composite structures under various loads. Classical laminate theory (CLT) has been applied to predict stiffness and strength of BF-reinforced polymer laminates [80], while progressive damage models with failure criteria (e.g., Tsai-Hill and Tsai-Wu) are being developed to simulate non-linear response and ultimate failure [81]. In civil engineering applications, numerical models in commercial FE software can reasonably predict the behavior of BF-reinforced concrete elements [82].

Despite these advances, significant challenges remain. Most current models are primarily descriptive and calibrated to specific experimental data, lacking robust predictive capability across diverse conditions. Accurate representation of the complex interface and random fiber distribution in short-fiber composites remains particularly challenging.

The future outlook points toward developing high-fidelity, multi-scale models that integrate molecular dynamics for interface properties, sophisticated RVE models with realistic fiber distributions, and homogenization techniques to bridge micro- and macro-mechanics. Such an integrated computational materials engineering framework would substantially reduce experimental dependencies and accelerate the design of next-generation BF composites.

6. Conclusions

This review has systematically analyzed advancements in basalt fiber (BF)-reinforced composites through a multi-dimensional framework encompassing material architecture, performance enhancement, and technological maturity. The findings demonstrate BFs’ evolution from simple reinforcement to a platform for developing high-performance, multi-functional composites. Their integration into various matrices consistently improves mechanical properties, crack resistance, thermal stability (up to 700–900 °C), and corrosion durability, establishing BF composites as robust solutions for demanding applications in construction, transportation, and marine engineering. The paradigm shift from basic reinforcement to interface-engineered functionalization represents the field’s most significant advancement. Strategic surface modifications using nano-SiO2 coatings and silane coupling agents have proven crucial for optimizing stress transfer and enabling novel functionalities like self-healing and electrothermal response. Concurrently, the emergence of simulation-guided design, particularly micro-mechanical FEA, marks a critical transition from empirical approaches toward predictive material design.

Several critical research gaps require attention:

- Long-term durability data under combined environmental stressors;

- International standardization beyond current regional standards;

- Predictive multi-scale modeling capabilities;

- Comprehensive sustainability assessments and recycling strategies.

Future research should prioritize the following:

- 5.

- Developing multi-functional hierarchical interfaces;

- 6.

- Establishing integrated computational materials engineering frameworks;

- 7.

- Qualifying materials for extreme environmental applications;

- 8.

- Implementing circular economy principles through recycling technologies and bio-based matrices.

In conclusion, while BF composites present a compelling pathway for modern engineering, realizing their full potential necessitates addressing these challenges through targeted interdisciplinary research and international collaboration.

7. Future Prospects

7.1. Ongoing Research and Innovations

Ongoing research endeavors are focused on continuously optimizing BF properties, composite formulations, and manufacturing processes [83]. The goal is to enhance the overall performance of BF-reinforced composites, making them even more competitive in various applications. By fine-tuning the composition of the composites and tailoring them to specific environmental conditions, researchers seek to maximize their effectiveness and durability. In the previous work [28], we proposed to use finite element technology to study the stress field distribution of chopped BFs in composite coatings and feedback the optimal addition amount of BFs and the optimal surface modification technology through the simulated stress field data. These innovations not only contribute to the composites’ performance improvements but also foster their acceptance as sustainable and high-performing alternatives in the broader composites industry.

7.2. Standardization Efforts

After searching on the internet, we only found four Chinese standards of basalt fiber, which are GB/T 25045-2010, GB/T 38111-2019, HG/T 6136-2022, and HG/T 6135-2022 [84,85,86,87]. Establishing the industry standards for BF-reinforced composites is critical to ensuring continued quality and performance across a variety of applications. Standardization involves a collaborative effort between researchers, manufacturers, and regulators to determine parameters, specifications, and test methods that can be universally applied. These standards are critical to providing a framework to guide the development, production, and evaluation of BF-reinforced composites. They help create a common language within the industry that enables stakeholders to communicate effectively and transparently about product specifications and performance expectations. In the field of BF-reinforced composites, the standardization process includes all aspects of material properties, test procedures, and quality control measures. The definition of these standards ensures that manufacturers adhere to an agreed set of guidelines to promote consistency in product characteristics and behavior. Collaboration between researchers, manufacturers, and regulators is essential for the successful establishment and development of these standards. Researchers use their expertise to develop scientifically sound standards, while manufacturers provide practical information about production challenges and capabilities. Regulators play a key role in ensuring that standards are harmonized with safety, environmental, and industry regulations. Ongoing industry dialog and collaboration can help raise standards over time. As technology advances and new knowledge becomes available, industry standards can be updated to reflect the latest knowledge, ensuring that BF-reinforced composites continue to meet or exceed performance expectations. Ultimately, the implementation of BF-reinforced composites industry standards not only improves quality and reliability, but also increases the confidence of end users, architects, and engineers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and L.L.; Data curation, B.P. and W.S.; Formal analysis, Y.Z. (Yanliang Zhang) and Z.G.; Investigation, Y.Z. (Yulong Zhang); Writing—Original Draft, Y.Y.; Writing—Review and Editing, J.W.; Methodology, J.Z.; Software, R.W.; Supervision, C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: [Elsevier, Taylor & Francis].

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Jiadong Li, Lin Lan, Baofeng Pan, Zhanyu Gu, Yulong Zhang, Yongbo Yan, Jia Wang and Jianwei Zhou were employed by the company Sinopec Southwest Oil & Gas Branch. Author Yanliang Zhang was employed by the company Changqing Oilfield Branch Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Deák, T.; Czigány, T. Chemical composition and mechanical properties of basalt and glass fibers: A Comparison. Text. Res. J. 2009, 79, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarayu, K.; Gopinath, S.; Ramachandra, M.A.; Iyer, N.R. Structural stability of basalt fibers with varying biochemical conditions- A invitro and invivo study. J. Build. Eng. 2016, 7, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiming, Y.; Jinxu, L.; Xinya, F.; Shukui, L.; Yuxin, X.; Jie, R. Investigation on mechanical properties and failure mechanisms of basalt fiber reinforced aluminum matrix composites under different loading conditions. J. Compos. Mater. 2018, 52, 1907–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Li, M.; Wang, S.; Peng, X.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, J. Effect of interlaminar basalt fiber veil reinforcement on mode I fracture toughness of basalt fiber composites. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 4985–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xu, S.; Song, Q. Study of eco-friendly fabricated hydrophobic concrete containing basalt fiber with good durability. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 65, 105759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, V.; Karimipour, H.; Taheri-Behrooz, F.; Shokrieh, M.M. Corrosion behaviour and crack formation mechanism of basalt fibre in sulphuric acid. Corros. Sci. 2012, 64, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ögüt, R.; Demir, A. The Effect of the Basalt Fiber on Mechanical Properties and Corrosion Durability in Concrete. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 5097–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybin, V.A.; Utkin, A.V.; Baklanova, N.I. Corrosion of uncoated and oxide-coated basalt fibre in different alkaline media. Corros. Sci. 2016, 102, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, S.; Ma, C.; Shi, T.; Qi, W.; Yang, H. Nano-SiO2 based anti-corrosion superhydrophobic coating on Al alloy with mechanical stability, anti-pollution and self-cleaning properties. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 9469–9478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Xu, X.; Xie, Y.; Bei, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Yu, H.; Sun, D. Microstructural evolution and anti-corrosion properties of laser cladded Ti based coating on Q235 steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 477, 130383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; De Silva, K.; Jones, M.; Gao, W. Cr-Free Anticorrosive Primers for Marine Propeller Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, L. 2D Nanomaterials Reinforced Organic Coatings for Marine Corrosion Protection: State of the Art, Challenges, and Future Prospectives. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2312460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decky, M.; Hodasova, K.; Papanova, Z.; Remisova, E. Sustainable Adaptive Cycle Pavements Using Composite Foam Concrete at High Altitudes in Central Europe. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gué, L.; Davies, P.; Arhant, M.; Vincent, B.; Verbouwe, W. Basalt fibre degradation in seawater and consequences for long term composite reinforcement. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 179, 108027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, H.; Zeng, L.; Yuan, Z.; Li, T.; Tao, L.; Yang, C.; Li, H.; Liu, C. The Effect of Heat Treatment Methods on the Structural Characteristics of Basalt Glass. Silicon 2024, 16, 2853–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xie, H.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, F.; Lin, C.; Fang, S. Acoustic emission characteristics and crack resistance of basalt fiber reinforced concrete under tensile load. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 312, 125442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Sun, Z. Chemical Durability and Mechanical Properties of Alkali-proof Basalt Fiber and its Reinforced Epoxy Composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2008, 27, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhong, J.; Gu, Y.; Li, G.; Cui, J. Mechanical properties, flame retardancy, and thermal stability of basalt fiber reinforced polypropylene composites. Polym. Compos. 2020, 41, 4181–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Guan, J.-W.; Chen, H.-M.; Liu, Y.-T. Study on Durability and Compression Behaviors of BFRP Bars under Seawater Deterioration and Constraint Condition. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2024, 36, 04023619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Ding, L.; Niu, F.; Jiang, K.; Wang, H.; Wu, Z. Effects of basalt fiber reinforced polymer minibars on the flexural behavior of pre-cracked UHPC after chloride induced corrosion. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 82, 108382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Lu, Z.; Liang, J.; Xie, J. Durability of carbon/basalt hybrid fiber reinforced polymer bars immersed in alkaline solution. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 4743–4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olhan, S.; Behera, B.K. Development of GNP nanofiller based textile structural composites for enhanced mechanical, thermal, and viscoelastic properties for automotive components. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2024, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wang, Q.; Ji, D.; Li, L.; Tan, J.; Wu, Q.; Lyu, Y.; Zhang, M. Nacre-Inspired Aramid Nanofibers/Basalt Fibers Composite Paper with Excellent Flame Retardance and Thermal Stability by Constructing an Organic–Inorganic Fiber Alternating Layered Structure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 4045–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, M.; Xing, Y.; Tian, J.; Liang, M.; Zhou, S.; Zou, H. Improving the ablative performance of epoxy-modified vinyl silicone rubber composites by incorporating different types of reinforcing fibers. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 4725–4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Larsson, S.; Benzerzour, M.; Maherzi, W.; Amar, M. Effect of basalt fiber inclusion on the mechanical properties and microstructure of cement-solidified kaolinite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 241, 118085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farouk, M.; Soltan, A.; Schlüter, S.; Hamzawy, E.; Farrag, A.; El-Kammar, A.; Yahya, A.; Pollmann, H. Optimization of microstructure of basalt-based fibers intended for improved thermal and acoustic insulations. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 34, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demina, N.M.; Tikhomirov, P.L. Comparative Study of the Impregnability of High-Strength Glass and Basalt Fibers. Glass Ceram. 2016, 73, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Lin, B.; Zhang, H.; Khalaf, A.H.; Tang, J. Investigation of optimal mechanical and anticorrosive properties of silane coupling agents modified chopped basalt fiber reinforced waterborne epoxy coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 487, 131023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybin, V.A.; Utkin, A.V.; Baklanova, N.I. Alkali resistance, microstructural and mechanical performance of zirconia-coated basalt fibers. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 53, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.; Fang, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Li, W.; Yuan, J.; Tan, L.; Wang, S.; Wu, Z. Surface modification of basalt with silane coupling agent on asphalt mixture moisture damage. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 346, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Liu, Z.; Tong, X.; Guo, L.; Miao, S.; Jiang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, C. Effects of raw material homogenization on the structure of basalt melt and performance of fibers. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 11998–12005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.; Verbouwe, W. Evaluation of Basalt Fibre Composites for Marine Applications. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2018, 25, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaldo, E.; Nerilli, F.; Vairo, G. Basalt-based fiber-reinforced materials and structural applications in civil engineering. Compos. Struct. 2019, 214, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Jamshaid, H.; Alshareef, M.; Alharthi, F.A.; Ali, M.; Waqas, M. Exploring the Potential of Alternate Inorganic Fibers for Automotive Composites. Polymers 2022, 14, 4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, V.; Di Bella, G.; Valenza, A. Glass–basalt/epoxy hybrid composites for marine applications. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 2091–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, B.A. Processing, structure, and properties of carbon fibers. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 91, 262–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertekin, M. 7—Aramid fibers. In Fiber Technology for Fiber-Reinforced Composites; Seydibeyoğlu, M.Ö., Mohanty, A.K., Misra, M., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizilkanat, A.B.; Kabay, N.; Akyüncü, V.; Chowdhury, S.; Akça, A.H. Mechanical properties and fracture behavior of basalt and glass fiber reinforced concrete: An experimental study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 100, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, M.; Yang, J.; Wu, Z. Study on Mechanical Properties of Basalt Fibers Superior to E-glass Fibers. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhaske, P.B.; Rathi, D.V.R. Performance of glass fiber, basalt fiber: Subjected to fire. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2022, 10, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xie, K.; Yang, Z.; Dai, H. The advantages of basalt glass flake coating for marine anticorrosion. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 332–334, 1619–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshaid, H.; Mishra, R.; Militky, J. Thermal and mechanical characterization of novel basalt woven hybrid structures. J. Text. Inst. 2016, 107, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, J.J.; Dai, J.X.; Li, J.; Wei, Z.Q.; Hausherr, J.M.; Krenkel, W. Influence of thermal treatment on thermo-mechanical stability and surface composition of carbon fiber. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 274, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopresto, V.; Leone, C.; De Iorio, I. Mechanical characterisation of basalt fibre reinforced plastic. Compos. Part B Eng. 2011, 42, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeesh, P.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S. Basalt fibers: An environmentally acceptable and sustainable green material for polymer composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 436, 136834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccarello, B.; Bongiorno, F.; Militello, C. Basalt Fiber Hybridization Effects on High-Performance Sisal-Reinforced Biocomposites. Polymers 2022, 14, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Qin, R.; Chow, C.L.; Lau, D. Bond integrity of aramid, basalt and carbon fiber reinforced polymer bonded wood composites at elevated temperature. Compos. Struct. 2020, 245, 112342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poornima, C.; Uthamballi Shivanna, M.; Sathyanarayana, S. Influence of basalt fiber and maleic anhydride on the mechanical and thermal properties of polypropylene. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Chen, M.; Lei, L.; Wu, Z. Effect of SiO2, Al2O3 on heat resistance of basalt fiber. Thermochim. Acta 2018, 660, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.J.; Cui, X.F.; Zou, W.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, H.B.; Yang, H.; Yan, J. Basalt/Polyacrylamide-Ammonium Polyphosphate Hydrogel Composites for Fire-Resistant Materials. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2021, 306, 2000582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, T.; Kandare, E.; Gibson, A.G.; Di Modica, P.; Mouritz, A.P. Compressive softening and failure of basalt fibre composites in fire: Modelling and experimentation. Compos. Struct. 2017, 165, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, H.; Jia, T. Improving mechanical properties of wood composites using basalt glass powder and basalt fiber. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 1048, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, J.-W.; Lee, S.-Y.; Park, S.-J. Interfacial Behaviors of Basalt Fiber-Reinforced Polymeric Composites: A Short Review. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2022, 4, 1414–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Cai, M.; He, C.; Si, C.; Li, L.; Fan, X.; Zhu, M. Basalt fiber as a skeleton to enhance the multi-conditional tribological properties of epoxy coating. Tribol. Int. 2023, 183, 108390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Song, S.; Cao, H. Strengthening of basalt fibers with nano-SiO2–epoxy composite coating. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 4180–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Liu, H.; Rao, L. Research on fire-resistant fabric properties of basalt fiber. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 217–219, 1151–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, G.; Rhee, K.Y.; Mišković-Stanković, V.; Hui, D. Reinforcements in multi-scale polymer composites: Processing, properties, and applications. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 138, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, T.-W.; Park, S.-M.; Jeong, Y.G. Structures, electrical and mechanical properties of epoxy composites reinforced with MWCNT-coated basalt fibers. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 123, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Xiao, P.; Kang, A.; Kou, C.; Wu, B.; Ren, Z. Innovative design of self-adhesive basalt fiber mesh geotextiles for enhanced pavement crack resistance. Geotext. Geomembr. 2024, 52, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-Z.; Liu, C.; Cheng, P.-F.; Li, Z.; Han, Y.; Wang, X.-Y. Enhancing the interfacial compatibility and self-healing performance of microbial mortars by nano-SiO2-modified basalt fibers. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 152, 105650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-Y.; Xu, L.; Lee, E.-H.; Choa, Y.-H. Magnetic Silicone Composites with Uniform Nanoparticle Dispersion as a Biomedical Stent Coating for Hyperthermia. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2013, 32, E714–E723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Zhang, H.; Feng, Q.; Zheng, Y. Improvement of basalt fiber dispersion and its effect on mechanical characteristics of oil well cement. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulus, H.; Kaybal, H.B.; Eskizeybek, V.; Avcı, A. Enhanced Salty Water Durability of Halloysite Nanotube Reinforced Epoxy/Basalt Fiber Hybrid Composites. Fibers Polym. 2019, 20, 2184–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cao, N.; He, J.; Du, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, G. Mechanical and anticorrosion properties of furan/epoxy-based basalt fiber-reinforced composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhong, T.; Xu, Q.; Su, Z.; Jiang, M.; Liu, P. The effects of chemical grafting 1,6-hexanediol diglycidyl ether on the interfacial adhesion between continuous basalt fibers and epoxy resin as well as the tensile strength of composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 323, 126563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 5659-2:2017; Plastics—Smoke Generation—Part 2: Determination of Optical Density by a Single-Chamber Test. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 1182; Reaction to Fire Tests for Products, Non-Combustibility Test. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- ISO 9705-1; Reaction to Fire Tests, Room Corner Test for Wall and Ceiling Lining Products, Part 1: Test Method for a Small Room Configuration. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Li, Z.; Wu, S.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, L. Influence of surface properties on the interfacial adhesion in carbon fiber/epoxy composites. Surf. Interface Anal. 2014, 46, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Rhee, K.Y.; Park, S.J. Plasma treatment and its effects on the tribological behaviour of basalt/epoxy woven composites in a marine environment. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2011, 19, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Amir, N.; Ahmad, F.; Ullah, S.; Jimenez, M. Effect of basalt fibers dispersion on steel fire protection performance of epoxy-based intumescent coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 122, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Chen, H.; Cui, G.; Qi, Y. Preparation of new conductive organic coating for the fiber reinforced polymer composite oil pipe. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 412, 127017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczewski, M.; Aniśko, J.; Piasecki, A.; Biedrzycka, K.; Moraczewski, K.; Stepczyńska, M.; Kloziński, A.; Szostak, M.; Hahn, J. The accelerated aging impact on polyurea spray-coated composites filled with basalt fibers, basalt powder, and halloysite nanoclay. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 225, 109286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Hu, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, J. Effect of PVA fiber and basalt fiber on residual mechanical and permeability properties of ECC after elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 433, 136610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Ding, L.; Jiang, K.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Wu, Z. Spalling resistance and mechanical properties of ultra-high performance concrete reinforced with multi-scale basalt fibers and hybrid fibers under elevated temperature. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 77, 107435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, U.R.; Jumahat, A.; Jawaid, M.; Dungani, R.; Alamery, S. Effects of Accelerated Weathering on Degradation Behavior of Basalt Fiber Reinforced Polymer Nanocomposites. Polymers 2020, 12, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Zhu, D.; Rahman, M.Z.; Shuaicheng, G.; Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Shi, C. Tensile properties deterioration of BFRP bars in simulated pore solution and real seawater sea sand concrete environment with varying alkalinities. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 243, 110115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agwu, N.; Ozoegwu, C.G. Critical investigation on the effect of fiber geometry and orientation on the effective mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced polymer composites. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2023, 30, 3051–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkazaz, E.; Crosby, W.A.; Ollick, A.M.; Elhadary, M. Effect of fiber volume fraction on the mechanical properties of randomly oriented glass fiber reinforced polyurethane elastomer with crosshead speeds. Alex. Eng. J. 2020, 59, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Sun, G.; Meng, M.; Jin, X.; Li, Q. Flexural performance and cost efficiency of carbon/basalt/glass hybrid FRP composite laminates. Thin-Walled Struct. 2019, 142, 516–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, R.M. Failure criteria for fiber composite materials, the astonishing sixty year search, definitive usable results. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 182, 107718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushanab, A.; Alnahhal, W.; Farraj, M. Structural performance and moment redistribution of basalt FRC continuous beams reinforced with basalt FRP bars. Eng. Struct. 2021, 240, 112390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yu, L.; Wang, C.; Cui, Z. Effect of Polyurethane Treatment on the Interfacial and Mechanical Properties of Basalt Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composite. Fibers Polym. 2024, 25, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 25045-2010; Basalt Fiber Roving. Federation, C.B.M.: Beijing, China, 2010.

- GB/T 38111-2019; Classification, Gradation and Designation of Basalt Fiber. Federation, C.B.M.: Beijing, China, 2019.

- HG/T 6135-2022; Non-Metallic Chemical Equipment-Basalt Fiber Reinforced Plastics Pipe and Fittings. China Plastic and Rubber Products Industry Association: Shanghai, China, 2022.

- HG/T 6136-2022; Non-Metallic Chemical Equipment-Basalt Fiber Reinforced Plastics Tank. China Plastic and Rubber Products Industry Association: Shanghai, China, 2022.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).