Abstract

For various reasons, many dielectric and electrochemical systems exhibit behavior described by a constant-phase element (CPE) instead of a pure capacitor. However, in many applications, it is desirable to determine the electrical capacitance of such systems as a physically meaningful quantity. For this purpose, models are developed that allow for the conversion of the parameters of the studied system into the so-called effective electrical capacitance of the system. This study aims to replace model-based effective capacitance estimation with an approach based on direct measurements using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). This approach utilizes the phenomenon of electrical resonance in the studied system. Using the described approach, the effective electrical capacitance of the coating system on steel was determined during over 300 h of exposure in Harrison’s solution. The CPE parameters were also determined during exposure. Using the Brasher–Kingbury equation, the kinetics of water absorption by the coating were compared using the obtained effective capacitance and the CPE parameter (pseudocapacitance). It was observed that using the effective capacitance yields significantly lower values of water content in the coating. The proposed method eliminates the uncertainty associated with speculative modeling and enables reliable tracking of the dielectric and electrochemical properties of systems, which is particularly important in batteries, supercapacitors, sensors, and protective coatings, where capacitance is a key indicator of performance and degradation.

1. Introduction

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful, non-destructive technique used to investigate both interfacial and bulk properties of electrochemical systems, including corrosion layers, battery electrodes, supercapacitors, and protective coatings [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Although ideal capacitive behavior is often assumed in such systems, most real materials exhibit frequency dispersion that departs significantly from ideality. This non-ideal capacitive response is commonly modeled using the so-called constant phase element (CPE) [12]. Its impedance is expressed as:

where

Z(ω) = 1/(Y0 (jω)n)

Z(ω) is the complex impedance;

Y0 is a pseudo-admittance (in units of S·sn);

ω is the angular frequency and ω = 2πf;

f is the frequency;

j is the imaginary unit;

n is the phase angle factor (dimensionless), with 0 ≤ n ≤ 1.

When n = 1, the CPE behaves as an ideal capacitor, while n = 0 corresponds to a pure resistor. For 0 < n < 1, the element represents a fractional capacitive behavior, indicating the presence of distributed processes such as surface roughness, porosity, heterogeneities in dielectric properties, or non-uniform current or ion distribution [13,14].

The physical meaning of the CPE and its parameters is not fully clear [15,16]. Because of the different units, Y0 cannot be directly considered as electrical capacitance. It is also not possible to directly represent the impedance of a CPE using a finite number of elements resistors (R), capacitors (C), and inductors (L). On the other hand, capacitance has a clear physical meaning, because it is the ability of a component to store electric charge when a voltage is applied across two conductive surfaces.

One of the most important practical applications of the CPE is in the characterization of organic anti-corrosion coatings on metallic substrates, particularly on carbon steel and galvanized steel. These coatings are widely used to protect the metal surface from corrosive environments such as marine atmospheres, industrial emissions, or aggressive electrolytes [8,17,18,19].

In EIS measurements, such organic coatings are often modeled using equivalent electrical circuits composed of resistive and capacitive elements. However, due to imperfections in coating structure, such as coating roughness, microvoids, water uptake, inhomogeneities in dielectric constant, or non-uniform adhesion to the substrate, the capacitive behavior of the coating deviates from ideal. This leads to the use of a CPE instead of a pure capacitor in the circuit model.

The capacitive response of an organic coating is generally associated with its dielectric properties and thickness. In practice, the use of a CPE enables more accurate fitting of impedance data, but complicates the extraction of physical parameters such as coating capacitance and water uptake, which are crucial for evaluating barrier performance and degradation over time. Changes in the CPE parameters, particularly a decrease in n and an increase in Y0, are often interpreted as indicators of coating degradation and increased heterogeneity due to the ingress of water and ions [19,20,21]. As a result, monitoring the evolution of CPE behavior over time has become a standard approach in assessing long-term protective performance of coatings on steel substrates.

However, the extraction of a physically meaningful effective capacitance from CPE parameters requires appropriate interpretation methods. Two of the most commonly used approaches were proposed by Hsu and Mansfeld [13] and Brug et al. [22], both offering mathematical transformations of the CPE parameters into an effective capacitance that can be tracked over time to study degradation processes.

In their study, Hsu and Mansfeld proposed a method for converting the CPE parameter Y0 into an effective capacitance Ceff, particularly in the context of corrosion studies. This model applies primarily to simple equivalent circuits like R-CPE, and it is used for systems with a distributed resistivity perpendicular to the surface, such as films that absorb water over time or develop gradient dielectric properties.

This method is based on the frequency fmax (or angular frequency ωmax) at which the imaginary part of the impedance reaches a maximum in a semicircular Nyquist plot. For a simple parallel R-CPE circuit, the effective capacitance Ceff can be estimated as [13]:

Ceff = (Y0R(1−n))1/n

On the other hand, the model proposed by Brug et al. [22] accounts for the presence of both solution resistance (Rs) and polarization resistance (Rp) in the system, making it more appropriate for analyzing more complex equivalent circuits. The Brug formula is often preferred when studying heterogeneous interfaces with lateral impedance variations, such as rough or porous coatings on metal substrates, where local current distributions dominate over vertical (through-film) phenomena.

This approach corrects for solution resistance and uses the Brug et al. formula [22]:

CBrug = Y01/n(Rs−1 + Rp−1)(n−1)/n

These estimations are especially valuable in organic coating studies, where changes in effective capacitance can be correlated with physical parameters such as water uptake (via the Brasher–Kingsbury relation [21,23]) or coating delamination.

A comparative study by Hirschorn et al. [24] explored these two models through both simulated and experimental impedance spectra.

Similarly, Harrington and Devine [25] applied both models to passive oxide films on titanium and nickel and found that the calculated charge carrier densities differed significantly, indicating that the model selection can directly affect the physical interpretation of EIS data.

The objective of this study is to propose an approach in which the determination of effective capacitance in electrochemical systems is based not on indirect calculations using mathematical models but on direct measurement of this quantity during impedance experiments. While these models are widely used and rely on theoretically justified assumptions, they remain approximate and speculative constructs, capturing only selected aspects of the physical processes occurring in real electrochemical systems.

The introduction of a direct measurement method for effective capacitance enables more reliable and unambiguous monitoring of system properties, particularly in cases where the functionality or condition of the system is directly related to its ability to store electrical charge. This is especially relevant for supercapacitors, but also electrochemical sensors and protective coatings on metals, and other systems in which changes in capacitance indicate degradation or changes in environmental conditions. The proposed concept thus represents a step toward reducing interpretive uncertainty in impedance data analysis and increasing the physical clarity and relevance of the obtained results.

2. Background

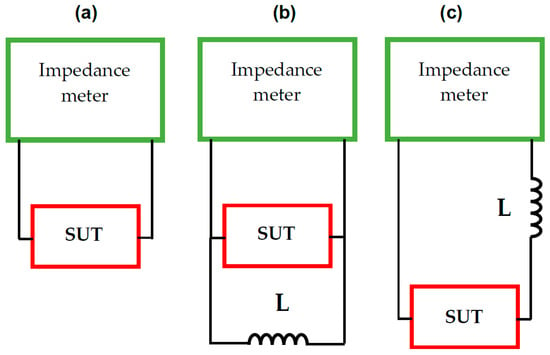

The proposed method for directly measuring the effective capacitance of systems exhibiting CPE behaviour is based on the phenomenon of electrical resonance [26]. To induce this phenomenon, an external inductance of known value is connected to the system under test (SUT), selected so that the resonance frequency falls within the frequency range of the measurement system used (Figure 1). It is possible to connect inductance L in parallel (Figure 1b) or in series (Figure 1c) to the SUT.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the concept of direct measurement of the effective capacitance of the system under test (SUT): (a) traditional measurement, (b) measurement with the parallel addition of an external inductance L, (c) measurement with the series addition of an external element with known inductance L.

The impedance ZR of the resistor R, the impedance ZL of the inductor L, and the impedance ZC of the capacitor C can be expressed by the following equations (based on [26]):

ZR = R

ZL = jXL = jωL

ZC = −jXC = −j 1/ωC = 1/jωC

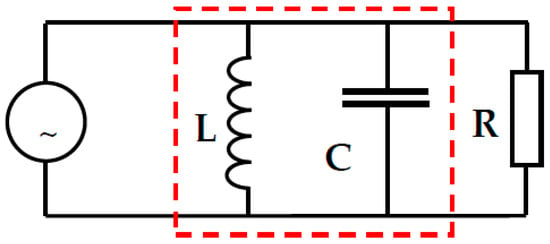

The total impedance Z for the parallel circuit (Figure 2) is:

1/Z = 1/ZR + 1/ZL + 1/Zc

Figure 2.

RLC parallel electrical circuit. The red dashed line indicates the elements that determine the occurrence of resonance.

Hence, after substituting Equations (4)–(6) into Equation (7) and transformations, we obtain:

Z(ω) = 1/(1/R + j(ωC − 1/ωL))

Electrical resonance in RLC circuits (containing resistors (R), inductors (L), and capacitors (C)) occurs when the inductive reactance (XL) and capacitive reactance (XC) cancel each other out, at a specific resonant frequency (Figure 2). This happens when in Equation (8) the following expression has the value 0, i.e.,

ωresC − 1/(ωres L) = 0

At the same time, it is worth noting that at the resonant frequency, the entire circuit reduces to pure resistance R:

Z(ωres) = R

Then, we get from Equation (9) the circular resonance frequency ωres or resonance frequency fres:

ωres = 1/√LC

fres = 1/(2π√LC)

Using Equation (11) or (12), the electric capacitance of a circuit element can be determined knowing the value of inductance L and the resonance frequency fres determined in the impedance measurement as the frequency of the maximum value of the impedance module for a parallel circuit or the frequency of the minimum value for a series circuit, leading to the formula:

C = 1/(4π2 L(fres)2)

An analogous analysis for the series circuit leads to identical Formulas (11)–(13) although the resonance phenomenon manifests differently in series and parallel circuits.

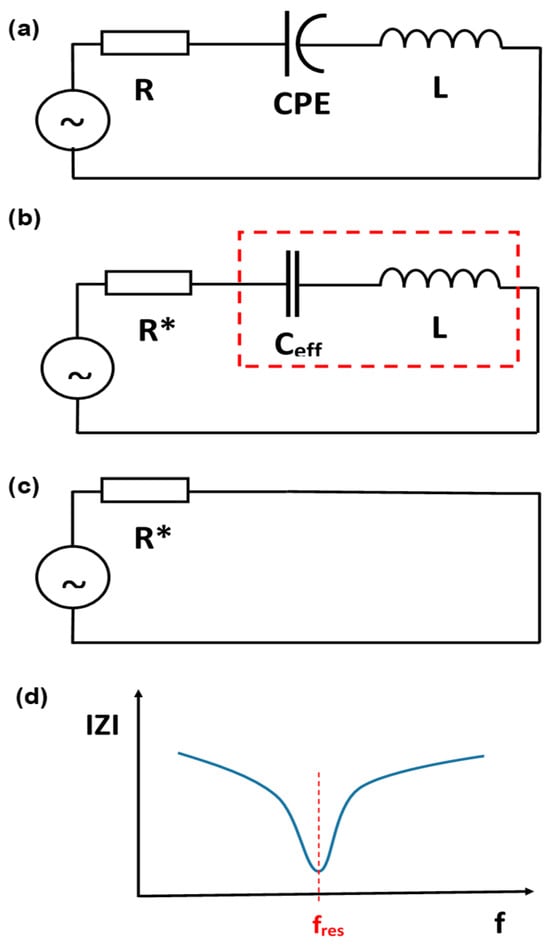

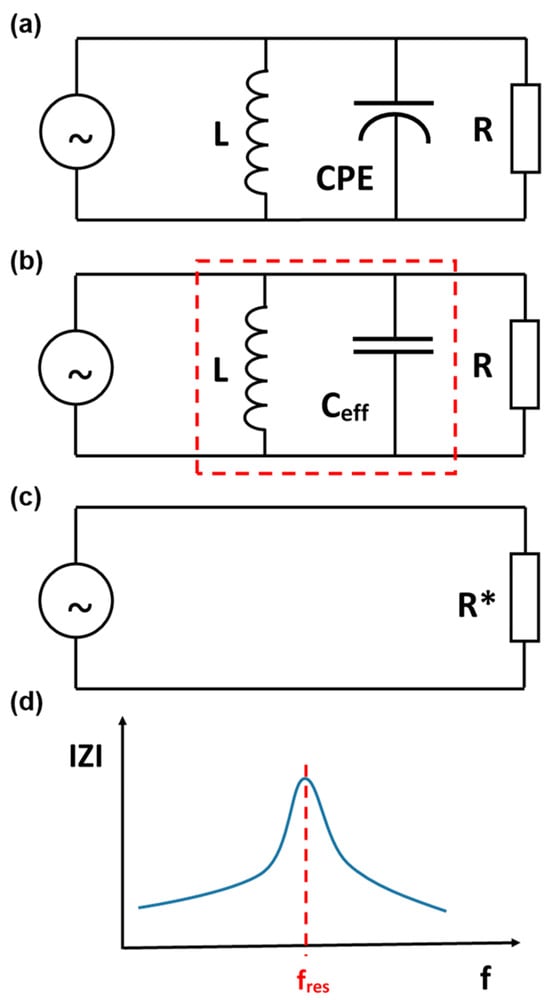

Conceptually, the situation will not change after replacing the ideal capacitance with the CPE. Resonance will still occur according to the presence of the effective capacitance (Figure 3 and Figure 4). From a physical perspective, electrical resonance is a state where the energy stored in a circuit oscillates back and forth between an inductor’s magnetic field and a capacitor’s electric field. When a capacitor is fully charged, it has maximum energy stored in its electric field. As the capacitor discharges, current flows through the inductor, transferring the energy into a magnetic field. Once the capacitor is fully discharged, the inductor’s magnetic field collapses. This induces a current that recharges the capacitor with the opposite polarity, returning the energy to the electric field. This cycle repeats, with energy continuously oscillating between the two components. The two branch currents are equal in magnitude and 180° out of phase with each other. Therefore, the two currents cancel each other out, and the total current is zero, and the input impedance of the circuit at resonance is equivalent to pure resistance (Figure 3c and Figure 4c). Under these conditions, the course of the impedance modulus IZI as a function of frequency f is as shown in Figure 3d (for the series circuit) and Figure 4d (for the parallel circuit).

Figure 3.

(a), A series RLC circuit supplied with a sinusoidal current source of variable frequency f; (b), at the resonance frequency fres (the marked fragment is reduced to 0); (c), the effective circuit in the resonance state at the resonance frequency fres; (d), a schematic diagram of the impedance modulus IZI as a function of frequency f—the minimum impedance value is observed for the resonance frequency fres.

Figure 4.

(a) A parallel RLC circuit supplied with a sinusoidal current source of variable frequency f; (b), at the resonance frequency fres (the marked fragment is reduced to 0); (c), the effective circuit in the resonance state at the resonance frequency fres; (d), a schematic diagram of the impedance modulus IZI as a function of frequency f—the maximum impedance value is observed for the resonance frequency fres.

3. Materials and Methods

Changes in the electrical capacity of anti-corrosion coatings on steel were investigated when immersed in a 10 times diluted Harrison solution (0.05% NaCl and 0.35% (NH4)2SO4/dm3). The coatings were applied as a two-layer system consisting of an epoxy primer and a polyurethane topcoat with a total thickness of 200 (±20) µm. DeFelsko PosiTector 6000 (DeFelsko Corporation, Ogdensburg, NY, USA) coating thickness gage was used to measure the thickness of coating layers and systems on steel. The coatings were sourced from a reputable commercial manufacturer. The coatings were applied to A4-sized metal substrates using a spray method, controlling the applied thickness. After application, the samples were cured for 4 weeks under laboratory conditions (22 ± 2 °C).

In this study, a parallel connection of the induction coil to the measuring cell or capacitors was used (Figure 1b). Impedance measurements were performed using a system consisting of a Schlumberger 1255 HF Frequency Response Analyzer (Solartron Analytical, AMETEK SI, Leicester, UK), and an Atlas 9181 Impedance Interface (Atlas-Sollich, Gdansk, Poland) in a two-electrode configuration in various frequency ranges from 1 MHz to 0.01 Hz with 99 frequency points. The working electrode was the substrate with the coating system applied, with a surface area of 12.5 cm2, separated by a glued PVC cylinder (Figure 5). The counter electrode was a platinum mesh in the form of a cylindrical lateral surface 5 cm high and 5 cm in diameter. According to the proposed methodology, a home-made Helmholtz coil was connected in parallel to the system under test. The coil used had an inductance of 21.6 mH, determined using a DE-5000U LCR Meter (DER EE, New Taipei, Taiwan) as the value obtained at a frequency of 100 kHz. During the measurement, the coating samples and the coil were placed in a grounded Faraday cage. The experiments were conducted on multiple cells to validate the findings and ensure their objective reproducibility (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Coated samples with Harrison’s solution-filled cylinders glued to them, for impedance measurements.

4. Results and Discussion

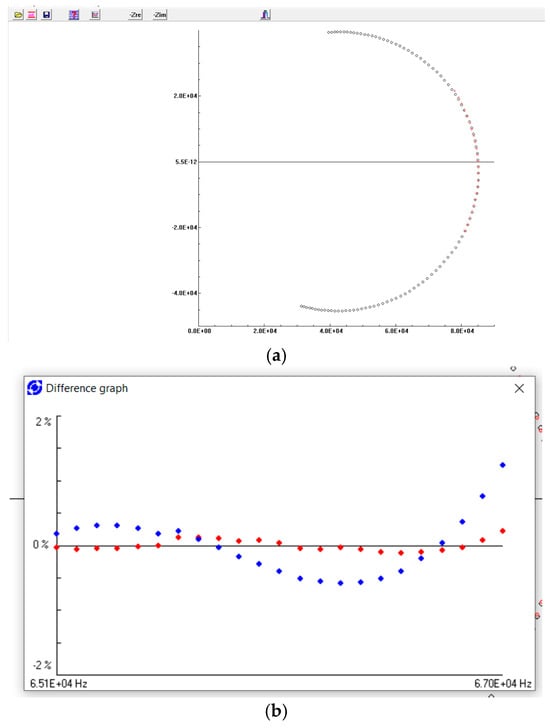

To validate the tested impedance data, the Kramers–Kronig (K-K) transformation was used, which addresses the causality, stability, and linearity of the complex response of materials. If the system satisfies the above characteristics, the real part and the imaginary part of the impedance are closely related, such that the imaginary part can be obtained by performing the K-K transformation through the real part, and vice versa. The method and the program “Kramers-Kronig test for Windows” proposed by Boukamp [27,28,29] were used; Figure 6. Fragments of the impedance spectrum around the resonance peaks were examined. Residual errors are a criterion characterizing the discrepancy between the measured data and the data transformed using the K-K relation. Figure 6b shows that the measured real part and imaginary part show good agreement with the calculated data (error below 0.5%).

Figure 6.

(a), Nyquist impedance spectrum obtained experimentally (blue points) and obtained using the Kramers–Kronig transform (red points). (b), Residual error as a function of frequency; the red points—real part differences, the blue points—imaginary part differences.

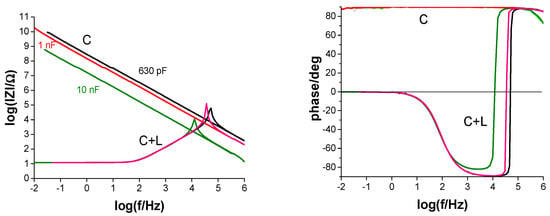

First, measurements were performed on capacitors (electronic components) with three different nominal capacitances (630 pF, 1 nF, 10 nF), which are similar to those observed for barrier coatings. Figure 7 shows the results of measurements without a connection (traditional) and with a parallel inductor. For the results with the inductance connected, maxima are obtained at different frequencies, depending on the capacitance. The electrical capacitances of the tested capacitors were determined using Formula (13), and the results are presented in Table 1. Commercial capacitors are characterized by a scatter of the actual electrical capacitance values, depending on the accuracy class, so the obtained results are reliable.

Figure 7.

Impedance spectra (in Bode format) of capacitors measured in the traditional configuration (C) and with an inductor connected (C + L).

Table 1.

Measurement results of capacitors (electronic components) using the resonance method (Figure 7).

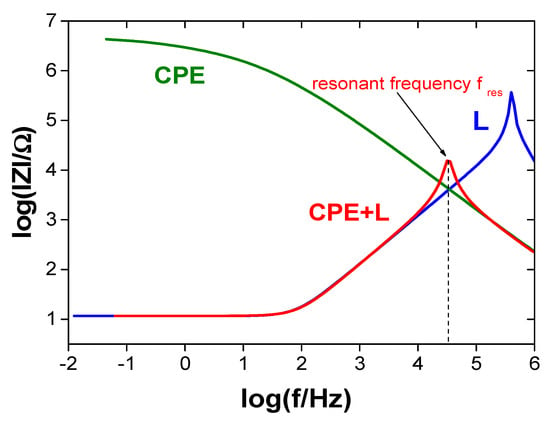

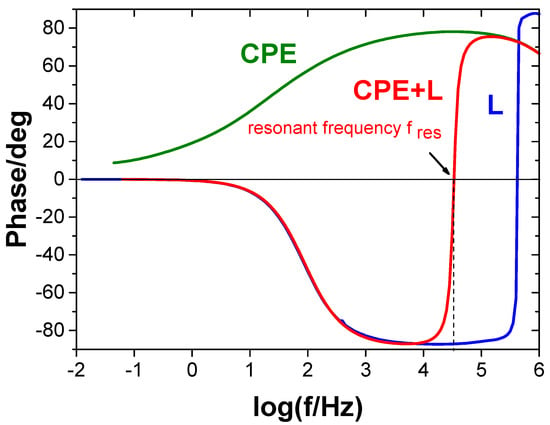

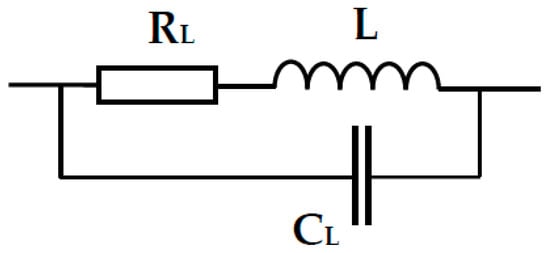

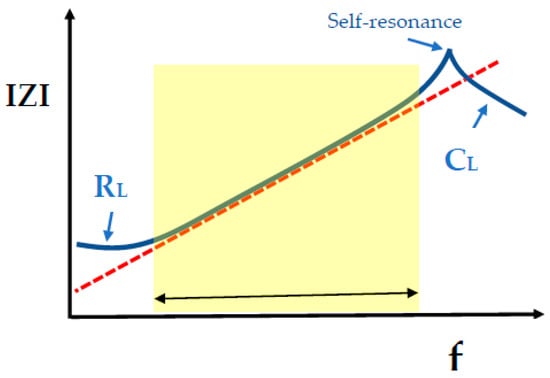

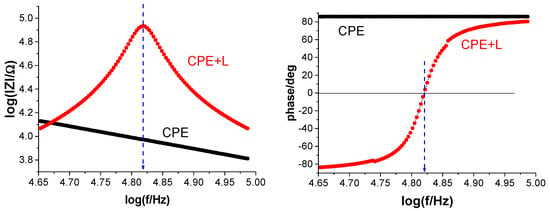

Figure 8 shows an example impedance diagram of a protective coating exhibiting the behavior described by CPE (with and without an inductor) and of the inductor itself. Similarly to capacitors (Figure 7), the effective capacitance of the coating can be determined based on the resonance peak frequency. The impedance spectrum of the inductor itself also exhibits a resonance peak, indicating that the inductor has self-capacitance resulting from the capacitance of the coil turns. This self-capacitance is detectable at high frequencies. The inductor also has relatively low ohmic resistance (resistance of the coil wire) at low frequencies. Figure 9 shows the equivalent electrical circuit of the real inductor. Coils with parameters such that the resonance frequency falls within the range where the coil behaves as an ideal inductor should be selected for measurements (this range is marked with a double-headed arrow in Figure 10).

Figure 8.

Impedance spectra of a coating exhibiting CPE behavior without an inductor attached (CPE), a coating with an inductor attached (CPE + L), and an inductor alone (L).

Figure 9.

Electrical equivalent circuit of a real inductor with inductance L; RL—the resistance component of a wound wire, CL—the electrical capacitance of the coil wire turns.

Figure 10.

Schematic spectra of the impedance modulus IZI for an ideal inductor (red dashed line) and a real inductor (blue continuous line) as a function of frequency f. The frequency region in which the real inductor behaves as an ideal inductor is marked.

It should also be noted that the resonance frequency can be determined not only from the peak frequency of the maximum impedance modulus but also from the frequency at which the phase angle (phase) is 0. This is because under resonance conditions, there is only resistance in the circuit (Figure 3c and Figure 4c).

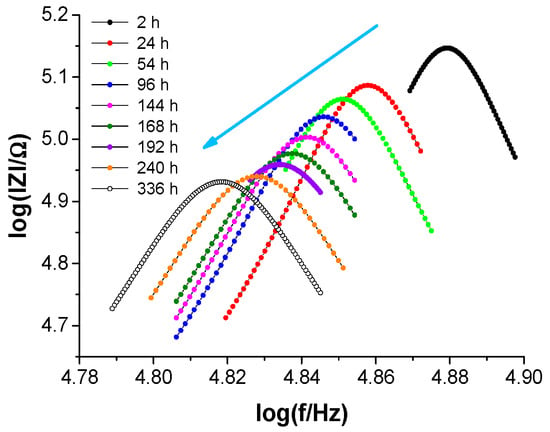

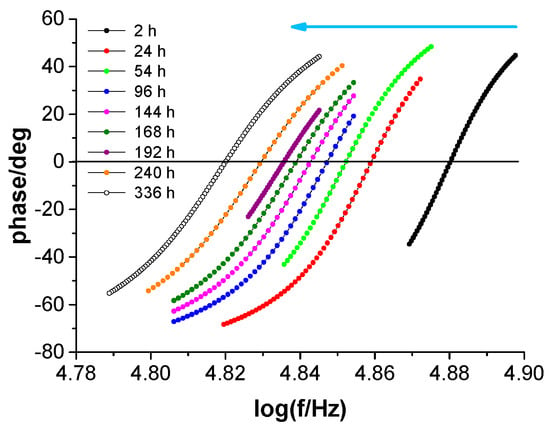

Water uptake by a protective coating on steel was studied by measuring the coating’s electrical capacitance during immersion in diluted Harrison’s solution. Figure 11 presents selected impedance spectra within a narrowed frequency range to shorten the measurement time and increase the accuracy of determining the resonant frequency (assuming a constant number of measurement points offered by the impedance meter).

Figure 11.

Selected impedance spectra (in Bode format) in a narrowed frequency range around the resonance frequency as a function of immersion time of the coating system on steel in Harrison’s solution. The arrow indicates subsequent spectra with increasing immersion time.

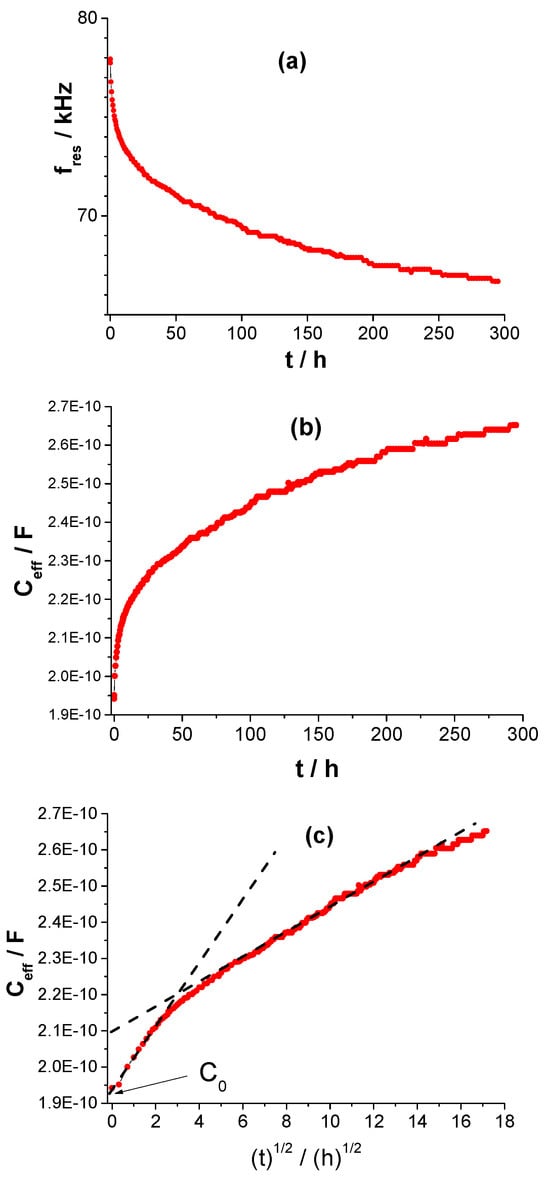

From the obtained spectra, resonant frequencies were determined for successive immersion times. Figure 12a shows the changes in the resonant frequency, fres, as a function of immersion time for an example sample. After conversion according to Equation (13), the coating’s electrical capacitance was determined as a function of immersion time (Figure 12b) and as a function of the square root of immersion time t (Fickian format, Figure 12c).

Figure 12.

Changes in the resonance frequency as a function of immersion time t; (a), effective capacitance as a function of immersion time t; (b), as a function of the square root of immersion time t; (c) for the tested coating sample on steel.

The performance and durability of protective coatings are strongly influenced by their ability to resist water uptake [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Water absorption not only alters the physical and mechanical properties of polymeric films but also facilitates processes such as plasticization, swelling, and ionic transport, which can ultimately compromise corrosion protection. To quantitatively describe water ingress into coatings, Brasher and Kingsbury [23] developed an equation that relates the change in dielectric properties of a coating to its water content.

Using the Brasher–Kingsbury equation [23], the kinetics of water absorption by the coating can be determined. The underlying principle is based on the high dielectric constant of water (approximately 80 at room temperature) compared to typical organic polymer coatings, whose dielectric constants lie in the range of 2–5. As water molecules diffuse into the polymer matrix, the effective dielectric constant of the coating increases measurably. By monitoring this change over time, one can estimate the fractional water uptake. The equation is:

where

ϕt = log(Ct/C0)/log(εw)·100%

Φt—the percentage by volume of water uptake at time t;

εw—the relative water permittivity (the dielectric constant) − (~80 at 20 °C);

Ct—the measured capacitance at time t;

C0—the measured capacitance at zero time.

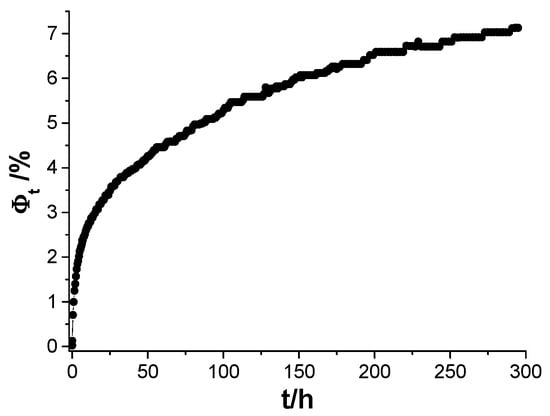

The C0 value was determined by approximation to time 0 through the equation of the line describing the initial exposure period in the Fickian format (Figure 12c). The obtained result is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Water absorption kinetics determined using the Brasher–Kingsbury equation, and effective electrical capacity values, obtained by the resonance method.

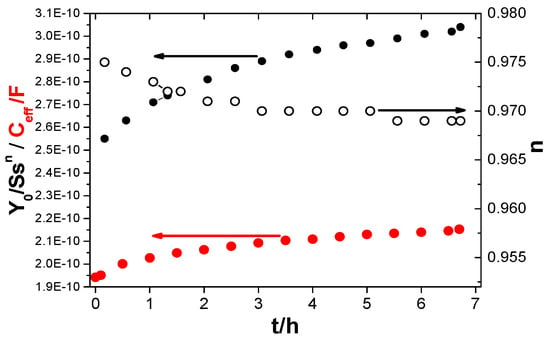

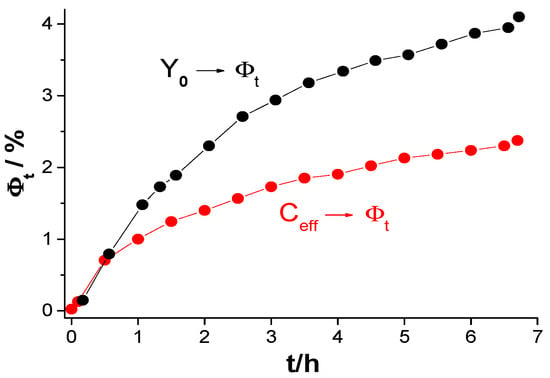

Although it is commonly utilized, its precision has been challenged, as research indicates that it frequently overestimates water absorption when compared to gravimetric measurements. However, other parameters are often used instead of true capacitance, such as the Y0 parameter of a CPE or capacitance values determined based on models using CPE parameters. The effect of using the Y0 parameter instead of the effective capacitance determined by the proposed resonance method was investigated. Resonance frequency measurements were taken every 0.5 h (with an induction coil connected to the tested steel coating), and immediately after this measurement (after less than 4 min), a measurement was performed without the induction coil (disconnected) on the same sample, obtaining a graph from which the Y0 and n parameters were determined. Examples of both measurements are shown in Figure 14. Figure 15, on the other hand, presents the obtained values as a function of immersion time t. As can be seen from the graph, the Y0 parameter has significantly higher values for the same exposure times. This indicates that the obtained water uptake values will also be overestimated, which is a common observation when comparing results obtained using the gravimetric method and those based on electrochemical parameter analysis [21,30]. Figure 16 shows the differences in water uptake determined using the effective capacitance, measured by means of the proposed method, and the CPE parameter Y0. It can therefore be assumed that this may be one of the most important reasons for the observed discrepancies.

Figure 14.

Example of impedance spectrum in Bode format measured with inductance L attached (red line) and without inductance L attached (black line) at almost the same moment of immersion.

Figure 15.

CPE parameters: Y0 and n, and effective capacity Ceff as a function of immersion time t for the same sample.

Figure 16.

Percentage of water volume in the coating system on steel determined using the Brasher–Kingsbury equation based on the Y0 parameter and the effective capacity Ceff.

When using the resonance method to determine the effective capacitance of a SUT, several practical and theoretical limitations arise. Key limitations include:

- Real circuits contain resistance that broadens the resonance peak, making the resonant frequency harder to measure accurately.

- Stray capacitance in cables, connectors, switches, or the inductor itself can add to the unknown capacitance.

- Parasitic inductances in wiring and fixtures disturb the intended resonant condition.

- The method requires a known, stable inductor value.

- Any tolerance or frequency-dependent variation in inductance directly affects the computed capacitance.

- Magnetic core inductors can change inductance with temperature, current, and frequency.

- Accurate determination of the resonant frequency requires precise instrumentation.

- At very high frequencies: parasitic reactances, skin effect, and component self-resonance limits accuracy.

- At very low frequencies: inductor size becomes impractical, and resonance may be too weak to measure.

- Very small capacitances require extremely high resonant frequencies, making measurement error-prone.

- Very large capacitances require bulky inductors or very low frequencies.

The resonance method is simple but is limited by damping, parasitic elements, component tolerances, measurement precision, and frequency-dependent behaviors. It still has many advantages:

- Resonance frequency can be measured very precisely with modern instruments.

- In low resistance systems, the resonance peak is sharp, allowing very accurate determination of resonant frequency, and therefore effective capacitance.

- Simple and straightforward measurement procedure-only the resonant frequency needs to be measured.

- Requires only one known component (the inductor)-reduces the need for complex calibration or multiple known standards.

- Suitable for a wide range of frequencies.

- The SUT is not subjected to high voltage or high current stress during testing–non-destructive method.

- Small capacitances produce high resonant frequencies, which can be measured very precisely.

- Can be implemented with impedance meter or simple instruments.

The resonance method is accurate, simple, inexpensive, versatile, and especially effective for low-loss systems with small-value capacitive properties. It requires minimal equipment while offering high precision when properly implemented.

5. Conclusions

A new method for directly determining the effective capacitance of a system exhibiting constant-phase element (CPE) behavior was presented. The proposed method utilizes the phenomenon of electrical resonance, which allows for determining the effective capacitance after connecting an inductor of known inductance to the system under test (in parallel or series) and measuring the resonant frequency.

A typical impedance measurement setup is used for this purpose without any changes. The proposed method was tested on protective barrier coatings, determining changes in the coating’s electrical capacitance as a function of immersion time in an aqueous solution. The results obtained using the proposed method were compared with those using the CPE parameter Y0, demonstrating that the differences can explain the overestimation of water uptake observed using different electrochemical results compared to those determined by the gravimetric method.

Future Perspectives:

- Although traditionally dominated by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), emerging resonant techniques offer advantages such as higher sensitivity to dielectric changes, reduced measurement time, and potential for in situ structural health monitoring. Future developments are expected to significantly enhance their applicability in both laboratory and industrial contexts.

- One major direction involves the integration of high-frequency resonant sensors, capable of detecting subtle variations in dielectric properties associated with early water uptake, plasticization, or microdefect formation.

- Another important perspective concerns the use of machine learning to interpret resonant frequency shifts. Because dielectric behavior in polymer coatings is inherently non-linear and influenced by complex physicochemical processes, data-driven models may provide more reliable correlations between resonance features and coating capacitance than traditional analytical formulas.

- A further promising direction lies in the development of multi-modal hybrid methods, in which resonant measurements are combined with EIS, gravimetry, or spectroscopic techniques. Such integrated approaches could correct for limitations inherent to each technique, enabling more accurate estimation of coating properties under varying environmental conditions. This is particularly relevant for systems exposed to cyclic humidity, temperature fluctuations, or mechanical stress.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Macdonald, J.R. Impedance Spectroscopy: Emphasizing Solid Materials and Systems; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfeld, F. Use of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy for the study of corrosion protection by polymer coatings. J. Appl. Electrochem. 1995, 25, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsoukov, E.; Macdonald, J.R. (Eds.) Impedance Spectroscopy: Theory, Experiment, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Miszczyk, A.; Darowicki, K. Multivariate analysis of impedance data obtained for coating systems of varying thickness applied on steel. Prog.Org. Coat. 2014, 77, 2000–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogihara, N.; Itou, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Takeuchi, Y. Impedance Spectroscopy Characterization of Porous Electrodes under Different Electrode Thickness Using a Symmetric Cell for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 4612–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammatikos, S.A.; Ball, R.J.; Evernden, M.; Jones, R.G. Impedance spectroscopy as a tool for moisture uptake monitoring in construction composites during service. Compos. Part A 2018, 105, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadhva, P.; Hu, J.; Johnson, M.J.; Stocker, R.; Braglia, M.; Brett, D.J.L.; Rettie, J.E. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy for All-Solid-State Batteries: Theory, Methods and Future Outlook. ChemElectroChem 2021, 8, 1930–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozda, M.; Miszczyk, A. Selection of Organic Coating Systems for Corrosion Protection of Industrial Equipment. Coatings 2022, 12, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazanas, A.C.; Prodromidis, M.I. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy A Tutorial. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2023, 3, 162–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizpour, A.; Bagovic, N.; Ploumis, N.; Mylonas, K.; Hoxha, D.; Kienberger, F.; Al-Zubaidi-R-Smith, N.; Gramse, G. Electrochemical Analysis of Carbon-Based Supercapacitors Using Finite Element Modeling and Impedance Spectroscopy. Energies 2025, 18, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlarski, G.; Stoeva, D.; Dechev, D.; Ivanov, N.; Ormanova, M.; Mateev, V.; Marinova, I.; Valkov, S. Review on Metal (-Oxide, -Nitride, -Oxy-Nitride) Thin Films: Fabrication Methods, Applications, and Future Characterization Methods. Coatings 2025, 15, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, K.S.; Cole, R.H. Dispersion and absorption in dielectrics I. J. Chem. Phys. 1941, 9, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Mansfeld, F. Technical note: Concerning the conversion of the constant phase element parameter Y0 into a capacitance. Corrosion 2001, 57, 747–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasia, A. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy and Its Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA; Heidelberg, Germany; Dordrecht, The Netherland; London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lasia, A. The Origin of the Constant Phase Element. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gateman, S.M.; Gharbi, O.; de Melo, H.G.; Ngo, K.; Turmine, M.; Vivier, V. On the use of a constant phase element (CPE) in electrochemistry. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2022, 36, 101133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendig, M.; Scully, J. Basic Aspects of Electrochemical Impedance Application for the Life Prediction of Organic Coatings on Metals. Corrosion 1990, 46, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierwagen, G.P. Evaluation of organic coatings with EIS: Problems and possibilities. J. Coat. Technol. 1996, 68, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.; Hubbard, J.B.; Miller, D.J. Understanding the degradation of organic coatings through impedance measurements. J. Coat. Technol. 2002, 74, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Deflorian, F.; Fedrizzi, L.; Rossi, S. Use of EIS to evaluate water uptake in organic coatings on metals. Electrochim. Acta 1999, 44, 4243–4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miszczyk, A.; Darowicki, K. Water uptake in protective organic coatings and its reflection in measured coating impedance. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 124, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brug, G.J.; van den Eeden, A.L.G.; Sluyters-Rehbach, M.; Sluyters, J.H. The analysis of electrode impedances complicated by the presence of a constant phase element. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1984, 176, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasher, D.M.; Kingsbury, A.H. Electrical measurements in the study of immersed paint coatings on metal. 1. Comparison between capacitance and gravimetric methods of estimating water-uptake. J. Appl. Chem. 1954, 4, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschorn, B.; Orazem, M.E.; Tribollet, B.; Vivier, V.; Musiani, M.; Diard, J.P. Determination of effective capacitance and film thickness from constant-phase-element parameters. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 6218–6227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, D.A.; Devine, T.M. Analysis of passive films on metals using capacitance models: A comparison. Corrosion 2008, 64, 222–229. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, J. Electrical and Electronic Principles and Technology, 6th ed.; Routledge; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boukamp, B.A. A Linear Kroning-Kramers Transform Test for Immitance Data Validation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1995, 142, 1885–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukamp, B.A. Electrochemical Impedance spectroscopy in Solid State Ionics; Recent Advances. Solid State Ion. 2004, 169, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukamp, B.A. Kramers-Kronig Test for Windows. Available online: https://www.utwente.nl/en/tnw/ims/publications/downloads/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Li, S.; Bi, H.; Weinell, C.E.; Dam-Johansen, K. Non-destructive evaluations of water uptake in epoxy coating. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e54777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosgien Lacombre, C.V.; Bouvet, G.; Trinh, D.; Mallarino, S.; Touzain, S. Water uptake in free films and coatings using the Brasher and Kingsbury equation: A possible explanation of the different values obtained by electrochemical Impedance spectroscopy and gravimetry. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 231, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xing, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S. A Comprehensive Review on Water Diffusion in Polymers Focusing on the Polymer–Metal Interface Combination. Polymers 2020, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castela, A.; Simoes, A. An impedance model for the estimation of water absorption in organic coatings. Part I: A linear dielectric mixture equation. Corros. Sci. 2003, 45, 1631–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeloos, A.J.; Attar, M.M. The diffusion and adhesion relationship between free films and epoxy coated mild steel. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 179, 107561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabet-Bokati, K.; Plucknett, K. Water-induced failure in polymer coatings: Mechanisms, impacts and mitigation strategies—A comprehensive review. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 230, 111058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Du, Y.; Lin, Z.; Liu, Z.; Gu, L. Effect of Water Uptake, Adhesion and Anti-Corrosion Performance for Silicone-Epoxy Coatings Treated with GLYMO on 2024 Al-Alloy. Polymers 2022, 14, 3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoseinpoor, M.; Prošek, T.; Babusiaux, L.; Mallégol, J. Simplified approach to assess water uptake in protective organic coatings by parallel plate capacitor method. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 26, 101858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).