Abstract

With the development of prefabricated buildings, the challenge of integrating fireproofing and anti-corrosion in steel structures has become increasingly prominent. Based on epoxy resin, we developed a multifunctional coating with high-flame retardant efficiency and corrosion resistance, which can be employed in the key parts of modular integrated construction (MiC), thereby enhancing the safety of the prefabricated buildings. Experimental data showed that the fire resistance limitation reached 124 min, the salt spray resistance 2540 h, and the adhesion grade 1. The limiting oxygen index (LOI) of the cured coating was 45%, corresponding to the V-0 classification in the vertical burning test from Underwriters Laboratories Inc. (Northbrook, IL, USA) (UL 94). Compared with the latest studies, the integrated formulation exhibits simultaneous gains in fire and corrosion protection, offering a promising single-layer solution for MiC.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of global industrialization and carbon neutrality goals, energy conservation, cost reduction, and green development have become core challenges in the construction industry. Prefabricated buildings, especially steel-structured MiC, have emerged as a key direction for industrial transformation due to their high assembly rate (>90%), low carbon emissions, and rapid construction. According to the Global Prefabricated Building Market Report 2024, the global prefabricated building market size exceeded USD 1.2 trillion in 2023, with MiC accounting for over 15% and growing at a CAGR of 8.5%. In regions such as Singapore and Japan, MiC has been widely applied in public housing and infrastructure projects, but its promotion is limited by the lack of efficient fireproof and anti-corrosion solutions for steel structures.

According to the China Steel Structure Industry Development Report (2021), for instance, Chinese steel structure output has exceeded 1.3 billion tons, accounting for over 50% of global production. The Chinese government requires “accelerating new-type building industrialization, vigorously developing prefabricated buildings, and promoting steel structure housing”, with especial emphasis on “actively advancing high-quality steel structure residential construction.” As a representative of steel structure prefabricated buildings, MiC has become a main direction for construction industrialization transformation due to its high assembly rate (over 90%), low-carbon features, and rapid construction advantages. However, MiC has significant challenges in coordinating fire resistance with anti-corrosion in practical applications. Traditional protection processes require layered coating of primer, intermediate paint, a fireproof layer, and a topcoat (4–5 working procedures). This involves conflicts between the prolonged construction cycles and material performance, the flammable corrosion-resistant resins, and acidic components, such as ammonium polyphosphate, which can accelerate steel corrosion. Additionally, the module gaps of MiC are prone to water infiltration and can serve as channels for fire spread during fire hazards. Statistical data showed that in the year 2021, steel structure buildings accounted for 27% of fire incidents caused by construction defects in China, with direct economic losses beyond 5 billion yuan.

Current MiC steel structure protection mainly relies on a layered coating of anti-corrosion and fireproof paints, respectively [1,2,3,4]. Anti-corrosion mechanisms based on galvanic cell principles typically use metal or metal oxide powders such as sacrificial anodes. However, corrosion rates multiply when coatings are locally damaged. As far as we know, fireproof coatings are normally categorized into intumescent and non-intumescent types. Intumescent coatings form carbonized insulation layers through thermal expansion but exhibit poor weather resistance and contain excessive inorganic fillers, such as aluminum hydroxide, which can reduce the coating adhesion. Non-intumescent coatings, such as cement-based thick coatings, require thick applications (≥15 mm), occupying space and easily delaminating, in spite of high fire resistance.

Global research on flame-retardant and corrosion-resistant synergistic coatings primarily focuses on filler modification and formulation optimization, with limited publications addressing integrated fire–corrosion protection through the coordination of self-flame-retardant resins and fillers [5,6]. Most intumescent fireproof coatings for steel structures employed the phosphorus–nitrogen intumescent flame retardants that reached high-efficiency fire protection by releasing inert gases in the gas phase and forming the carbonization layer in the condensed phase. However, these fireproof coatings suffered from insufficient corrosion resistance [7,8,9,10,11]. Recent advancements introduced nanomaterials, such as vermiculite and mica, into both intumescent and non-intumescent fireproof coating systems, enhancing their specific surface area and shielding effects. For instance, nano-vermiculite (50–100 nm) with lamellar structures can prolong corrosion medium penetration paths and enhance the salt spray resistance, while mica powder can improve mechanical stability by filling microcracks [12,13,14,15]. Anti-corrosion coatings typically incorporated zinc powder, zinc phosphate, or iron oxide additives into resins. Commercially available anti-corrosion coatings generally exhibit low oxygen index and lack fire resistance, being flammable during fires [16,17]. Current research on dual-functional fireproof and anti-corrosion coatings is largely limited to the laboratory scale, lacking engineering validation for MiC’s special structures, such as corrosion protection of connection nodes and the fireproofing of module gaps.

Recent international efforts have focused on inherently flame-retardant epoxy matrices. As far as we know, epoxy resin has high strength and rigidity, can withstand large pressure and impact, has a high surface hardness and good wear resistance, and has excellent corrosion resistance to acids, alkalis, salts, and other chemical substances. In addition, good thermal stability and excellent insulation features endow its use as various electronic components. More importantly, this kind of resin is also a recyclable material with low environmental pollution. As a result, the fireproofing of epoxy resin and the corresponding application have attracted great attention [18,19,20,21,22]. For instance, Rybyan et al. cured DER-331 with arylaminocyclotriphosphazenes, achieving a V-0 rating with only 6 wt % P [23]. A hyperbranched flame retardant SD containing P, N, and Si was successfully synthesized for the manufacture of high-performance, flame-retardant EP systems by Wang et al. [24]. However, in most studies on fireproof coatings, it is hard to find reports about resistance to neutral salt spray exceeding 2000 h. It can be seen that the design of synergistic resins/fillers that coordinate high barrier and carbon formation functions is highly necessary.

Current technologies present three major limitations: (1) single functionality failing to meet MiC’s complex operational requirements; (2) cumbersome construction processes with poor quality control; and (3) absence of systematic solutions for critical components, especially in connection nodes. To address these challenges, this study proposes a multifunctional coating technology based on modified epoxy resin, achieving integrated improvement in both fireproofing and anti-corrosion by virtue of molecular modification and multiscale synergistic design.

The present work departs from previous studies by (i) employing a self-crosslinking P-N epoxy that functions simultaneously as corrosion barrier and char former, (ii) replacing conventional multilayer practice (4–5 coats) with a single-layer direct-to-metal system, and (iii) validating performance on MiC-specific joints and module gaps rather than flat steel panels only. This innovation not only simplifies construction processes (60% procedure reduction) but also significantly reduces lifecycle maintenance costs, providing a groundbreaking solution for efficient protection of prefabricated buildings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Main Raw Materials

Matrix material: self-made resin modified from bisphenol A epoxy resin (EPON 828, HexionSpecialty Chemicals, Columbus, OH, USA), weight per epoxide 200–240 g/eq; viscosity at 25 °C 8000–12,000 mPas; n values for the epoxy oligomer were 4–8; exhibiting strong adhesion (≥4 MPa) and low curing shrinkage (<2%). Flame retardant: modified phosphorus–nitrogen flame retardant (self-developed). Nano-additives: nano-vermiculite (50–100 nm, Zhejiang Fenghong New Materials Co., Ltd., Huzhou, China), mica powder (1–5 μm, China National Nuclear Corporation, Shaoguan, China).

2.2. Preparation of Modified Resin

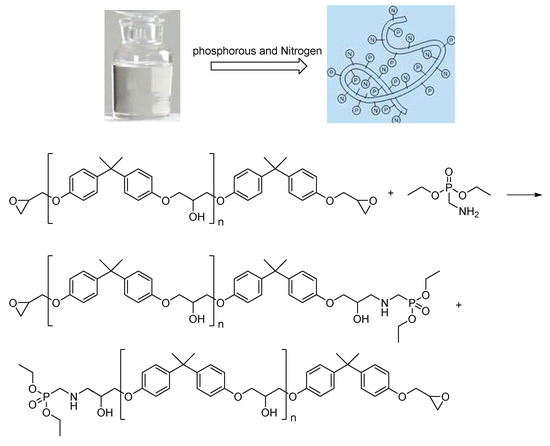

Ordinary bisphenol A epoxy resin lacks prominent flame-retardant properties and is typically used in anti-corrosion coatings with limited performance, heavily relying on the fillers for corrosion resistance. In this study, bisphenol A epoxy resin was chemically modified using phosphorus- and nitrogen-containing molecules to synthesize a hybrid polymeric resin, incorporating phosphorus and nitrogen elements in the modified resin. The phosphorus–nitrogen polymer inherently exhibited excellent flame retardancy, while the cured resin showed great adhesion to metal substrates. Figure 1 illustrated the synthetic design and reaction equations of the self-made modified resin.

Figure 1.

Self-made modified resin.

2.3. Experimental Procedure

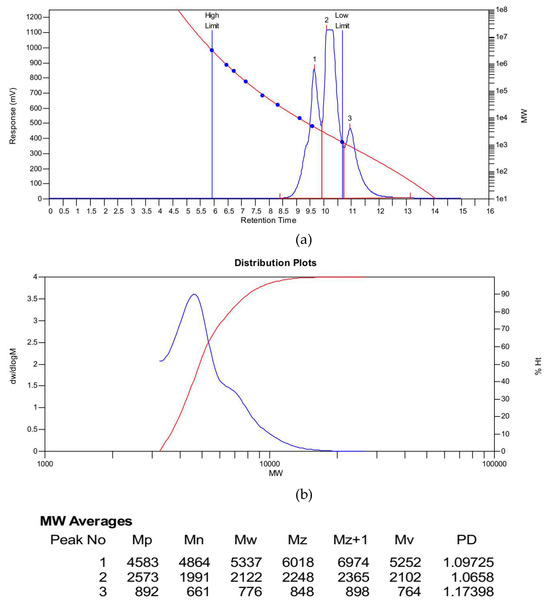

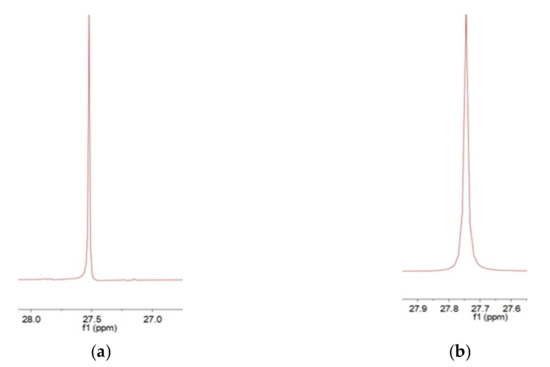

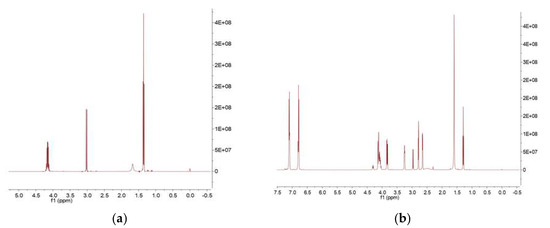

Under nitrogen protection, 100 g (0.25–0.26 mol) of bisphenol A epoxy resin (EPON 828), 0.5 mol% DBU catalyst (relative to epoxy resin, 0.12 g), 100 g xylene, and 100 g chloroform were added to a 500 mL three-neck flask and stirred at 300 rpm for 30 min. A mixed solution of 32.4 g (0.15 mol, 0.6 equivalent relative to epoxy groups) of diethyl aminomethyl phosphonate and 50 g chloroform was slowly added dropwise (2 h). After the addition, the mixture was heated to 60 °C and reacted for 8 h. The product was purified by vacuum distillation (temperature 60–80 °C, pressure 0.08–0.1 MPa) to remove solvents, yielding a viscous hybrid liquid (self-made modified resin) with a yield of 85%–90%. Upon reaction completion, vacuum distillation yielded a viscous hybrid liquid, designated as the self-made resin. The reaction pathway was shown in Figure 1. During the reaction, the amino group in diethyl aminomethyl phosphonate attacked the epoxide groups in the bisphenol A epoxy resin. By controlling the dosage of diethyl aminomethyl phosphonate to 0.6 equivalents, a product of epoxide ring-opening derivatives was obtained. The GPC figure was listed in Figure 2. The mean Mw of the self-made resin is about 4600. From the 31P NMR, it was found that the chemical shift was moved from 27.53 to 27.75 ppm. From the 1H NMR, it was found that diethyl aminomethyl phosphonate was bonded to the epoxy resin to give the phosphorous-containing resin, as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 2.

The GPC of the self-made resin. (a) Red line: calibration curve; Blue line: elution curve. (b) Red line: cumulative curve of molecular weight percentage; Blue line: Molecular weight distribution curve.

Figure 3.

(a) The 31P NMR of the diethyl aminomethyl phosphonate and (b) the 31P NMR of the self-made resin.

Figure 4.

(a) The 1H NMR of the diethyl aminomethyl phosphonate (b) the 1H NMR of the self-made resin.

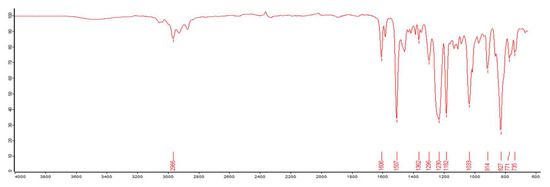

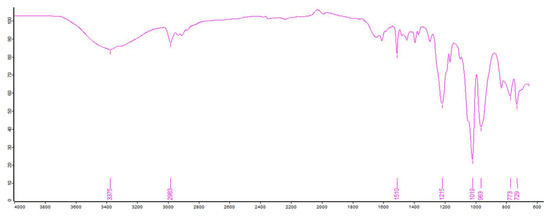

Also, the IR spectra indicated that there was a broad peak at 3375 cm−1 related to the stretching vibration of -OH. Compared to the original IR (Figure 5), the OH group was increased, implying that some of the epoxy groups were opened to form OH group. The peak around 2983–2893 cm−1 should be the stretching vibration absorption of -CH2-, and the absorptions at 1019 cm−1 can be ascribed to the P-O-C bending vibration. A characteristic peak of P=O stretching vibration should be 1215 cm−1, as shown in Figure 6. In terms of these data analysis, the self-made resin should contain the phosphorous functional groups.

Figure 5.

The IR spectrum of the original epoxy resin.

Figure 6.

The IR spectrum of the phosphorus-containing resin.

2.4. Paint Preparation

Specific preparation steps:

The scale of coating preparation is 1 kg. The coating formulation was listed in Table 1. The dispersion disk with an outer diameter of 100 mm was used, and the entire preparation process is carried out at 25 °C.

- (1)

- At room temperature, we added self-made resin and the corresponding solvent to the paint mixing tank. We started stirring at a speed of 800 rpm until a vortex appeared at the center of the liquid surface;

- (2)

- Dispersants, defoamers, wetting agents, and anti-settling agents were slowly added to a flask, while leveling agents and other additives were added into the preparation tank from step (1). Then, the modified phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant, carbonization agent, and foaming agent were added into the preparation tank. After the addition of these reagents, the reaction mixture was dispersed at a stirring speed of 1800 rpm for 35 min to ensure thorough mixing. Afterwards, the pigment filler was added to the mixing tank and dispersed at a stirring speed of 2200 rpm for 45 min. Finally, the mixture was further stirred and dispersed at a speed of 1800 rpm for 65 min.

- (3)

- The curing agent was added according to the actual required ratio, followed by thorough stirring and curing. Then, this mixture was filtered with a fine mesh strainer. The shelling-out can be carried out with a brush coating or an airless spray coating on the surface of the substrate. Before coating, the surface needed to be thoroughly polished to remove dust and rust. The treated surface should be kept clean and coated within 2 h.

Table 1.

Coating formulation (phr, parts per hundred resin by mass).

Table 1.

Coating formulation (phr, parts per hundred resin by mass).

| Material | Mass Fraction (Phr) | Material | Mass Fraction (Phr) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-made resin | 100 | Flame retardant | 40–65 |

| Dispersant | 0.5–1.5 | Charring agent | 22–35 |

| Defoamer | 0.5–1.5 | Blowing agent | 38–58 |

| Wetting agent | 0.5–1.5 | Color fillers | 22–40 |

| Anti-settling agent | 0.5–2.5 | Solvent | 50–100 |

| Leveling agent | 0.5–2.5 | Curing agent | 10–40 |

Note: Color fillers are a mixture of titanium dioxide and zinc phosphate (mass ratio 1:1); solvent is xylene or xylene/n-butanol (mass ratio 3:1–3:2); and curing agent is amine (diethylene triamine), polyamide (polyamide 650), or polyether amine (D230).

According to the preparation steps, we adjusted the ratio of each component in the formula to give the various formula PT1, PT2, PT3, PT4, and PT5 and the corresponding coatings separately, as shown in Table 2. The experimental results were listed as T1-T5 in Table 2. DT1, DT2, and DT3 were the control experiments. DT1 was a commercially available epoxy based fireproof coating, DT2 was a commercially available epoxy anti-corrosion paint, and DT3 was a clean self-made resin, i.e., the prepared resin without any flame retardants, carbonization agents, or foaming agents, while the other components were the same as those in T1. Table 3 presented the test standards and performance indicators, referring to Chinese standards and the corresponding ISO standards. The experimental results were shown in Table 4.

Table 2.

The control experimental groups with the variation in the components.

Table 3.

Test standards and performance indicators.

Table 4.

The control experimental results according to the various standards.

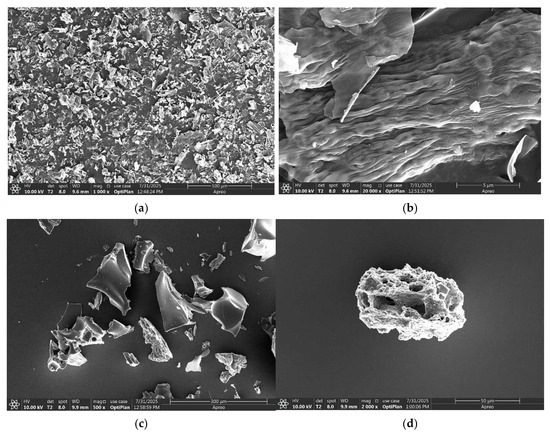

Also, the carbonized layers of T1 and DT3 after combustion were detected by SEM, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The morphologies of the carbonized layers of T1 and DT3 after combustion. (a) Scale bar 100 µm; (b) scale bar 5 µm; (c) scale bar 300 µm; (d) scale bar 50 µm.

3. Results and Discussion

As shown in Table 2, we initially screened flame retardants, charring agents, and foaming agents, focusing on the limiting oxygen index (LOI) of the coatings. The corresponding results were listed in Table 4. The cured film of DT-3, which was the self-made resin without flame retardants, charring agents, or foaming agents, presented a higher oxygen index of 28. Its flame resistance and neutral salt spray resistance were superior to those of the commercially available anti-corrosion paint DT-2. This indicated that the self-made resin inherently had flame-retardant capability. Moreover, this resin demonstrated excellent compatibility with various flame retardants, charring agents, and foaming agents, allowing various flame-retardant additives to be incorporated effectively. We assumed that the addition of flame retardants could further enhance the overall fire resistance of DT-3.

Next, we optimized dispersants, defoamers, wetting agents, anti-settling agents, and leveling agents. The experimental results indicated that the coatings exhibited sedimentation, sagging, excessive bubbles, and incomplete curing without these additives. After addition of these additives, all of these issues can be solved, which showed the necessity of additive incorporation with the modified resin. At the same time, the resin presented good compatibility with these additives. The additives listed in Table 2 were conventional additives, which were tailored for compatibility with those specific solid components in the coating.

Also, the morphologies of the carbonized layers of T1 and DT3 after combustion were detected by SEM. From the SEM pictures, it was found that the film of T1, which was the self-made resin with different optimized additives, such as flame retardants, charring agents, and foaming agents and so on, can give the integral carbonized layer to resist the heat propagation, as shown Figure 7a. The layer was constituted from small sheets (Figure 7b). In contrast, without the additives, the film of the pure self-made resin could not form integral carbonized layers and instead produced separated carbonized particles, as shown in Figure 7c,d, which consisted of different porous particles. This particle layer could not resist heat propagation.

Finally, the pigments, solvents, and curing agents were screened. After optimization, titanium dioxide and zinc phosphate were chosen as representative pigments across all test groups. Using amine- or polyamide-based curing agents, all coatings successfully cured into films and demonstrated outstanding flame retardancy and anti-corrosion performance. For instance, as shown in T1 in Table 3, the performances of the film showed an oxygen index 45, flame resistance time 124 min, adhesion grade 1, and the neutral salt spray resistance 2450 h.

All of these performance experiments revealed the technical advantages of the self-made resin as below.

- Excellent solubility and dispersibility: The resin kept stable in various polar solvents, such as xylene and alcohols. Moreover, the resin can be cured into a film with high integrity through simple processing.

- Controllable crosslinking: Retained epoxy groups in the resin enable the controlled crosslinking reactions with diverse curing agents, affording larger and more complex polymer networks that enhance water and salt spray resistance.

- Superior interfacial adhesion: The film demonstrated Grade 1 adhesion with cross-cut tests. The salt spray tests indicated that corrosion resistance can exceed that of traditional epoxy zinc-rich anti-corrosion coatings.

- Synergistic flame-retardant effects: Phosphorus–nitrogen structures in the resin backbone, combined with various flame retardants, produce significant synergy, meeting the requirements of the GB14907-2018 national standard.

Figure 8 showed a sample of a fireproof and anti-corrosion integrated coating, which was used for prefabricated building, tested in a salt spray machine after undergoing 2540 h neutral salt spray resistance tests in terms of GB 10125-2012. From the figure, we observed that the coating is basically intact, without obvious damage, such as bulging, cracking, or peeling, which indicated that the T1 film had great anti-corrosion capabilities.

Figure 8.

The coated steel plate prepared from T1 in Table 2.

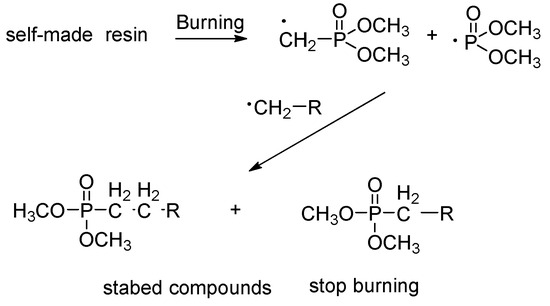

As for the mechanism of fire resistance, we assumed that the phosphorous-containing resin can give various phosphorous radicals at high temperatures. These radicals can catch the carbon radicles to form the stable compounds, resulting in the radicle propagation and extinguishing the flame, as shown Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

The proposed fire-resistant mechanism.

4. Conclusions

A fireproofing and anti-corrosion integrated coating was developed for prefabricated buildings, which has an oxygen index of 45, a fire resistance limit of 124 min, and a salt spray resistance of 2540 h. The comprehensive performance of this kind of coating is significantly better than that of most of current coatings. The coating has a wide application in MiC structural construction, which can effectively reduce the bearing capacity of connection nodes and the water leakage of module gaps, overcoming the shortcomings in MiC construction. In the future, we will focus on researching the weather resistance of coatings, such as UV aging and freeze–thaw cycles, to promote the development of industry standards and meet the advanced requirements for high-quality prefabricated buildings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W.; methodology, Z.W.; software, Q.S. and K.L.; validation, S.L., J.G. and Z.M.; formal analysis, S.L. and Q.S.; investigation, S.L.; resources, S.L. and Q.S.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.W.; visualization, S.L.; supervision, Z.W.; project administration, Z.W.; funding acquisition, Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “Research on Integrated Fire Protection and Anti-Corrosion Protection of Modular Steel Structure Buildings Based on Nano-Epoxy Multifunctional Coatings, China State Construction International Holdings Limited’s 2022 Annual Science and Technology Research and Development Plan”, grant number “CSC1-2022-Z-11”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Song Liu, Jun Guan and Zhiheng Ma were employed by China State Construction International Engineering Limited. The remaining authors were employed by University of Science & Technology of China and Institute of Advanced Technology, University of Science and Technology of China. No any conflict of interest among these affiliations.

References

- Shi, C.Q.; Su, J.H. Application of Functional Architectural Coatings in Assembled Steel Structures. China Coat. 2020, 35, 25–28+37. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L.Y. Experimental Analysis of Synergistic Flame Retardant Modification of Acrylic Resin Fire Retardant Coating for Prefabricated Building. Adhesion 2020, 43, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.D.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.C.; Xu, K.; Yu, F. Research of Waterborne Heavy-Duty Anti-Corrosion Coatings for Fabricated Steel Structures. Paint Coat. Ind. 2021, 51, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.M. The Application and Improvement of Anti-corrosion and Fireproof Technologies in Prefabricated Steel Structure Buildings. Foshan Ceram. 2024, 34, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Fan, G.D.; Li, D.B.; Chen, X.Y.; He, Y.P. Development of High Solid Organic Siloxane Hybrid Anticorrosive and Fireproof Coating. Guangzhou Chem. Ind. 2022, 50, 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.Z. A Kind of Anti-Corrosion and Fireproof Coating and Its Preparation Method. China Patent 113354988A, 7 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.Y.; Yang, H.Q.; Yuan, Y. Development of N-P-C water and flame retarding coating. Electroplat. Finish. 2001, 20, 51–53+68. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.S. Application of Star -Shaped Unimolecular Intumescent Flame Retardant in Fireproof Coatings. Paint Coat. Ind. 2014, 44, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Weil, E. Weil Fire-Protective and Flame-Retardant Coatings—A state-of-the-Art Review. J. Fire Sci. 2011, 29, 59–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.G.; Sun, Y.M.; Wang, X.T.; Xu, J. Effect of Matrix Resin on Performance of Waterborne Ultra-Thin Intumescent Fireproof Coatings. Coat. Prot. 2024, 45, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.P.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Tian, A.Q.; Cao, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.H. Research Progress on the Intumescent Fire Retardant Coatings for Steel Structure. Paint Coat. Ind. 2024, 54, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Xuan, P.F.; Jiang, J.C. Study on Performance of Waterborne Fire Retardant Coatings Modified with Inorganic Clays. Paint Coat. Ind. 2014, 44, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W. The influence of different factors on the adhesion and fire resistance performance of fireproof coatings. Fire Sci. Technol. 2019, 38, 850–853. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, D.; Guo, J.; Fan, G.D.; Li, D.B.; Chen, X.Y.; He, Y.P. Development and Application of Quick-drying Waterborne and Environmental Friendly Lightweight Fire-retardant Damping Coatings. Paint Coat. Ind. 2022, 52, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.M.; Li, X.; Xiong, X.L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.X. Mechanical properties and fire resistance of non-intumescent fireproof paint: A case study. Electroplat. Finish. 2023, 42, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.-Q.; Chen, H.-Q. Prospects for the Development of Pigment and Fillers in Anti-corrosion Coatings. Paint Coat. Ind. 2003, 33, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.H.; Zhang, B.X.; Pei, Y.; Zhang, P. Preparation of Waterborne Acrylic Primer for Light Anticorrosion of Steel Structures. Guangzhou Chem. Ind. 2022, 50, 96–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, M.; Cui, J.; Zhao, Z.; Li, R.; Guan, H.; Liu, L.; Jiao, C.; Chen, X. Solvent-free intumescent fire protection epoxy coatings with excellent smoke suppression, toxicity reduction, and durability enabled by a micro/nano-structured P/N/Si-containing flame retardant. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 183, 107762–107777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yu, Q.; Yu, B.; Zhou, F. New Progress in the Application of Flame-Retardant Modified Epoxy Resins and Fire-Retardant Coatings. Coatings 2023, 13, 1663–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, F.; Sun, R.-Y.; Song, F.; Wang, Y.-Z. Solvent-free epoxy coatings with enhanced cross-linking networks towards highly-efficient flame retardancy, water resistance and anticorrosion. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 197, 108835–108844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, M.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Q. Recent progress on flame-retardant bio-based epoxy resins: Preparation methods and performance evaluation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 327, 147069–147109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasirzadeh, M.; Ebrahimi, M.; Zahedi, S. Enhancing the durability of fire-retardant epoxy coatings through an eco-friendly self-stratification approach. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2025, 22, 1699–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybyan, A.; Bilichenko, J.V.; Kireev, V.V.; Kolenchenko, A.A.; Chistyakov, E.M. Curing of DER-331 Epoxy Resin with Arylaminocyclo- triphosphazenes Based on o-, m-, and p-methylanilines. Polymers 2022, 14, 5334–5344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Huo, C.; Wang, G.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, P.; Song, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, A. P/N/Si-containing hyperbranched flame retardant for improving mechanical performances, fire safety, and UV resistance of epoxy resins. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 193, 108562–108571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).