Abstract

Streptococcus agalactiae are bacteria that can cause a range of infections, some of them life-threatening. Currently, antimicrobial resistance has become a global problem that puts public health at risk. Despite the widespread use of β-lactams, penicillin remains the first-line antimicrobial for the treatment of invasive S. agalactiae infections. However, reduced susceptibility and resistance to penicillin have been identified in several countries. Penicillin-binding proteins, mainly PBP2X, have been associated with reduced susceptibility to β-lactams in streptococci. The aim of this review is to summarize currently published data on penicillin-binding proteins in S. agalactiae and penicillin susceptibility, highlighting the increasing number of strains with reduced susceptibility and resistance to penicillin commonly used in the prophylaxis and treatment of invasive infections by this pathogen. Data on invasive S. agalactiae strains with high levels of penicillin resistance have been found in Japan, the United States, Canada, and Africa. The data on antibiotic resistance are alarming and require increased monitoring of strains with reduced penicillin susceptibility, as well as preventive control measures to avoid the spread of resistant mutant strains.

1. Introduction

Streptococcus agalactiae (group B Streptococcus, GBS) is widely recognized as a leading cause of neonatal sepsis and invasive disease in the elderly or people with comorbidities [1]. Penicillin remains the first-line antibiotic for the treatment of S. agalactiae infections and is crucial for preventing vertical transmission to the newborn through intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) [2]. However, isolation of S. agalactiae presenting reduced penicillin susceptibility (RPS) has been reported since 2008 [3] and has become a matter of concern worldwide.

The emergence and progression of antimicrobial resistance constitute one of the most significant dangers to public health, as highlighted in clinical investigations supervised by the World Health Organization (WHO). RPS S. agalactiae strains are defined based on antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Both the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) and the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) provide standardized guidelines for performing antimicrobial susceptibility testing and for interpreting clinical breakpoints for S. agalactiae. EUCAST has established an epidemiological cut-off value (ECOFF) for penicillin in S. agalactiae of 0.125 mg/L, as well as zone diameter breakpoints of >18 mm [4]. According to CLSI, isolates of S. agalactiae with RPS are defined as those with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) > 0.12 µg/mL [5]. Isolates with MICs above this threshold are considered to have acquired resistance mechanisms.

In S. agalactiae, the RPS has been attributed to the acquisition of mutations in genes encoding the penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) [6,7], enzymes that catalyze the biosynthesis of bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan. These mutations result in the production of PBPs with reduced affinity for β-lactam binding. However, significant gaps remain in our understanding of the functional impact of individual or combined PBP mutations, therapeutic failure resulting from small increases in MIC, and the evolutionary dynamics that may drive the worldwide spread of RPS S. agalactiae strains.

Therefore, this review aimed to gather available epidemiological data and current knowledge on the most relevant PBP mutations associated with RPS and penicillin resistance (PR) in S. agalactiae strains, contributing to identifying priorities for future research and improving the clinical management of S. agalactiae infections.

2. Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBPs)

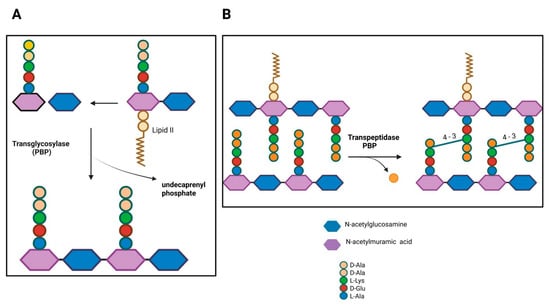

PBPs comprise two classes based on their molecular weight and enzymatic activity (glycosyltransferase and/or transpeptidase). Low molecular weight PBPs (LMM class C) are monofunctional enzymes, such as carboxypeptidases involved in peptidoglycan remodeling, while high molecular weight PBPs (HMM class A and B) are responsible for peptidoglycan polymerization and its insertion into the pre-existing cell wall [8]. The N-terminal domain of HMM PBPs class A is responsible for glycosyltransferase activity, catalyzing the elongation of non-crosslinked glycan chains. After lipid II (disaccharide-pentapeptide attached to the pyrophosphate-tethered undecaprenyl tail) is inverted to the periplasmic side, glycosyltransferases polymerize the sugar chains (Figure 1A), while the penicillin-binding C-terminal domain has transpeptidase activity, catalyzing the cross-linking of peptides between two adjacent glycan chains. PBP recognizes the terminal portion of D-alanine, catalyzing the attack of the carbonyl group of the penultimate D-alanine by the lateral amino group at position (3) of an adjacent chain (4–3 cross-link; Figure 1B). In class B, the N-terminal domain plays a role in cell morphogenesis through interaction with other proteins involved in the cell cycle [9].

Figure 1.

Penicillin-binding proteins in bacterial peptidoglycan synthesis. (A) PBPs with transglycosylase activity. (B) Transpeptidase PBP activity. D-Ala, D-alanine; L-Lys, L-lysine; D-Glu, D-glutamate; L-Ala, L-alanine. Figure created with BioRender.com.

PBPs possess a highly stable covalent complex through the serine in their active site, where penicillin and other β-lactams bind irreversibly, forming a stable acyl-enzyme intermediate that permanently inactivates the enzyme [10,11]. The catalytic serine attacks the carbonyl group of the β-lactam ring, promoting ring opening and the formation of a stable covalent acyl-enzyme complex that impairs transpeptidation, leading to peptidoglycan cross-linking failure and bacterial death [12]. Altered PBPs, resulting from multiple homologous recombination events between genes of closely related species (mosaic genes), combined with additional point mutations, have been described in pneumococci and oral streptococci, where amino acid substitutions represent more than 10% of the primary sequence [7]. Identifying the amino acid alterations involved in resistance, combined with structural information, will provide a better understanding of the enzymatic function of PBPs and the development of new inhibitors. However, mosaic sequences of pbp genes represent a challenge for classification and organization. Comparison of nucleotide sequences from susceptible strains reveals that these sequences exhibit levels of polymorphism similar to other loci, with one or two amino acid substitutions along the protein [6]. Mosaic pbp genes also exhibit sequence blocks that approximate the non-mosaic alleles in PBP2B, PBP1A, and PBP2X [6,13,14]. These blocks can encompass various regions of the transpeptidase domain or even a large part of the extracellular domain, the magnitude of which suggests that these divergent sequence blocks originate from other streptococcal species to escape protein selective pressure [6,15,16]. S. agalactiae produces three bifunctional class A PBPs (PBP1A, PBP1B and PBP2A) and two monofunctional class B PBPs (PBP2X and PBP2B) [17]. However, few studies report the biological functions and differences between PBPs in S. agalactiae. Therefore, to fill this gap, the general differences and biological functions of the PBPs analyzed in different microorganisms will be described.

The origin of sequence blocks in pbp mosaic genes is still unknown, with some exceptions for PBP2X. A study revealed that a family of mosaic pbp2x genes occurred in Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus oralis, demonstrating independent inter- and intraspecies recombination events [18]. These data gave rise to the hypothesis that commensal streptococci, such as S. mitis and S. oralis, acquired resistance through point mutations by exposure to β-lactam treatment for diseases, being subsequently exchanged between related streptococcal species. PBP2X depletion in S. pneumoniae promoted elongated and swollen cells with pointed ends [19]. Resolution 3D structured illumination microscopy (3D-SIM) showed the exceptional localization of PBP2X in the centers of septa in cells at intermediate to late stages of division, suggesting that the proteoglycan transpeptidase cross-linking activity of PBP2X has a biological function during septum formation and proteoglycan remodeling [20]. Phylogenetic analysis showed that S. pyogenes strains of the same emm type and the same amino acid substitution in PBP2X were clonally related by descent, indicating that strains with alterations in PBP2X can spread to new hosts and cause invasive infections [21].

PBP1A, also called PonA, and PBP1B proteins contain a non-catalytic domain involved in the regulation of glycosyltransferase and transpeptidase activities and are essential for cell viability in S. agalactiae and S. pneumoniae [10,17,22]. PBP1A is preferentially involved in proteoglycan synthesis during cell elongation and plays an important role in the resistance of S. agalactiae to antimicrobial peptides, potentially representing a widespread mechanism for evading the human innate immune response [23]. PBP1A was important for lung proliferation and resistance to killing by polymorphonuclear leukocytes and alveolar macrophages in a neonatal mouse model of S. agalactiae infection [24]. The mutant S. agalactiae strain ponA also showed reduced virulence in a murine sepsis model compared to the wild-type strain [25]. PBP1B is involved in septation, being found in high concentrations in the mid-cell region during cell constriction. FtsN, a divisome-specific protein, binds to PBP1B, stimulating its glycosyltransferase biosynthetic activity, contributing to the synthesis and overall regulation of septal peptidoglycan during cell division [26].

PBP2 is involved in cell division, particularly at its location in the septum. Certain bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), where the first crystal structure of a soluble form of PBP2A was published in 2002, acquire PBP2A [27]. Crystallographic analyses showed that PBP2A, the mecA gene product, could maintain transpeptidase activity and resist β-lactam binding, maintaining a closed conformation of the active site. Thus, interaction with a second molecule (e.g., muramic acid, peptidoglycan, or ceftaroline) at an allosteric site induced a conformational change, allowing the active site to open for catalysis [28]. The ability of ceftaroline, a β-lactam antibiotic, to stimulate the allosteric opening of the active site, leading to the inactivation of PBP2A by a second β-lactam, will allow future studies to obtain allosteric inhibitors based on the structure of PBP2A.

PBP2B is a class B specific to cell division with transpeptidase activity [29]. In S. agalactiae, researchers have identified that the polymerization of the glycan chain by the glycosyltransferase activity of RodA, a well-characterized SEDS (shape, elongate, and divide) family protein, is activated by PBP2B, generating the production of longer peptidoglycan fragments and faster depletion of the substrate lipid II [30].

Interestingly, Nishimoto and co-authors suggested that resistance to β-lactams in pathogenic streptococci is restricted to naturally competent species through intra- and interspecific recombination due to in vivo fitness trade-offs from de novo mutations in PBPs. The authors demonstrated that serially transformed recombinant strains efficiently integrate into the DNA of resistant oral streptococci, acquire resistance and tolerance to β-lactams, and maintain virulence in an in vivo model, indicating that de novo mutations are of primary relevance [31]. However, other components of the peptidoglycan synthesis machinery likely interact with PBPs directly or indirectly and may be modified in response to changes in the PBPs. All these facts contribute to the difficulties in experimentally verifying the impact of individual mutations within PBPs on penicillin resistance. The availability of larger amounts of genomic data for RPS and commensal streptococci will facilitate obtaining more information about the complex genetic network between species and will unravel mutations in components involved in the expression of penicillin resistance. These observations raise questions about the different roles that PBPs may play in cell wall formation and the possibility that their functions may vary slightly depending on the nature of the bacterium, the local environment of the cell, and the stage of the cell cycle.

3. Mutations in Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBPs)

Identifying amino acid substitutions relevant to the reduction in affinity for specific PBPs is a difficult task because, due to the recombination process, neutral substitutions were probably imported along with those that confer antibiotic resistance. However, the number of likely important substitutions was proposed based on their absence in susceptible strains, presence in many resistant strains, and proximity to catalytic motifs [32]. RPS or resistance to β-lactam antibiotics may be due to reduced access to PBPs, low binding affinity to PBPs, or β-lactamases that promote hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring [12,33]. PBPs contain three essential conserved sequences (SXXK, SXN, and KT(S)G) involved in the transpeptidation mechanism, crucial for bacterial cell wall synthesis. Alterations in these motifs or adjacent areas can decrease the binding affinity of PBPs to β-lactam antibiotics [34]. This resistance mechanism often arises through homologous recombination between related bacterial species in environments where antibiotic pressure is significant. In S. agalactiae, mutations in genes encoding PBPs have been associated with increased antibiotic resistance. Comparative phylogenetic studies have indicated that multiple RPS S. agalactiae genetic lineages have developed independently due to the accumulation of mutations, particularly in the pbp2x gene, which plays a significant role in reducing the organism’s susceptibility to β-lactams [3,34,35,36]. This understanding highlights the genetic adaptations in PBPs that contribute to antibiotic resistance, complicating the treatment of infections caused by S. agalactiae.

Several mutations have been identified in S. agalactiae, resulting in amino acid substitutions close to the conserved active site (Table 1), including V405A and/or Q557E of the PBP2X transpeptidase [35,37]. Four distinct classes (I–IV) have been proposed based on specific PBPs exhibiting different amino acid mutations. Important amino acid substitutions in the active site of PBP2x have been established by kinetic and structural studies. Mutation in two residues in the serine region downstream of the active site altered the orientation of the serine hydroxyl group, decreasing the affinity with β-lactams [38]. Furthermore, high-resolution analysis of PBP2X and multiple sequence alignments demonstrated an amino acid cluster lining a small water-containing cavity, presumably involved in PBP2X resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. Site-directed mutation in these amino acids significantly reduced the affinity for β-lactams [39].

Mutations and substitutions close to the active sites of the PBP2B, PBP1A, and PBP2A enzymes are also considered critical [40]. Deletion of pbp1a or pbp1b genes resulted in increased sensitivity to penicillin and ampicillin, suggesting that PBP1A and PBP1B play an important role in transpeptidation relative to PBP1A or PBP2B when S. agalactiae strains are under stress due to β-lactam antibiotics. Deletions in the pbp1a and pbp2b genes also promoted the growth of bacterial cells in significantly longer chains, suggesting that the mutant strains exhibited a defect in cell separation during the stationary phase [17]. The emergence of S. agalactiae isolates with reduced sensitivity or resistance to penicillin is concerning.

Table 1.

Reduced susceptibility to penicillin amongst Streptococcus agalactiae isolates and the amino acid substitutions in pbp genes.

Table 1.

Reduced susceptibility to penicillin amongst Streptococcus agalactiae isolates and the amino acid substitutions in pbp genes.

| Author, Year [Reference] | Penicillin MIC | Mutations Identified | Country (Period) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pbp2x | pbp2a | pbp2b | pbp1a | |||

| Chu, 2007 [41] | 0.25 (n = 1) | ND | ND | ND | ND | Hong Kong (2005) |

| Kimura, 2008 [3] | 0.25 (n = 8) 0.5 (n = 5) 1.0 (n = 1) | Q557E, V405A | ND | ND | ND | Japan (1995–2005) |

| Nagano, 2008 [35] | 0.25 (n = 1) 0.5 (n = 6) 1.0 (n = 2) | S353F, A374V, F395L, V405A, A400V, R433H, H438Y, A514V, Q557E, G648A, T77I | E63K, T175I, L285F, Y236C | V80A, Y262N, G539E, T567I, G613R | L45P, N163K, Y470F, G527V, N723S | Japan (2003–2004) |

| Gaudreau, 2010 [42] | 0.25 (n = 1) | I377V, G627V, N575D | S453N, N682D | V625I, P278L | T526A | Canada (2004–2007) |

| Longtin, 2011 [43] | 0.5 (n = 1) | G371D | E636G, S644F, S676F | ND | T546P | Canada (2008) |

| Nagano, 2012 [44] | 0.25 (n = 10) | V405A, F395L, R433H, H438Y, G648A, I377V, V510I | NT | T567I | ND | Japan (2007) |

| Nagano, 2014 [45] | 0.5 (n = 2) | A400V, V405A | ND | Q557E, T567I | ND | Japan (2011–2012) |

| Seki, 2015 [46] | 0.25 (n = 19) 0.5 (n = 20) 1.0 (n = 6) | V405A, Q557E | NT | NT | NT | Japan (2012–2013) |

| Morozumi, 2016 [47] | 0.125 (n = 5) 0.25 (n = 3) 0.5 (n = 1) | K372E, I377V, G398A, V405A, Q412L, G429D, H438Y, D478A, E513Q, Q557E | NT | NT | NT | Japan (2010–2013) |

| Metcalf, 2017 [36] | 0.25 (n = 6) | I377V, G406D, Q557E | NT | NR | NR | USA (2015) |

| Sigaúque, 2018 [48] | 0.12 (n = 7) | G398A | ND | ND | ND | Mozambique (2001–2015) |

| Yi, 2019 [49] | 0.5 (n = 2) | G398A, V405A, Q557E | NT | NT | NT | South Korea (NI) |

| Van der Linden, 2020 [50] | 0.5 (n = 1) 1.0 (n = 1) | I377V, F395L, V405A, H438Y, V510I, Q557E | ND | V80A | A521V, del719–722, N723S, V726A, T526I | Germany (NI) |

| Li, 2020 * [51] | 2.0 (n = 1) | I377V, T720S | E63K | V80A, S147A, S160A | T701P V706A | Hong Kong (2014–2017) |

| McGee, 2021 [52] | 0.25 (n = 6) | I377V, G406D G398A, G627V V510I, I510V Q557E, L534S G627V | NT | NT | NT | USA (2015–2017) |

| Nishiyama, 2022 [53] | 0.25 (n = 5) 0.5 (n = 3) | G398A, V405A, Q557E, N575D, S295G, Q557E | NT | ND | G719A, R629H | Japan (2017–2018) |

| Koide, 2022 [54] | 0.25 (n = 7) 1.0 (n = 1) | V405A, G329V, G398A, G429D, I377V, F395L, R433H, H438Y, V510I, G648A, V405A, Q412L, Q557E | Defective | T567I | T587I, F524V, G719N | Japan (2008–2016) |

| Chu, 2007 [41] | 0.25 (n = 1) | ND | ND | ND | ND | Hong Kong (2005) |

| Ikebe, 2023 [55] | 0.25 (n = 6) 0.5 (n = 1) | I377V, G398A, Q412L, H438Y, V405A, Q557E, F395L, R433H, T473M, V510I, G329V, K372E, G429D | ND | T567I | T537P, F541V, N635-, G636-, A621V, A547V | Japan (2014–2021) |

| Ntozini, 2025 [56] | 0.25 (n = 1) | New types that are not yet assigned a number | ND | ND | ND | South Africa (2019–2020) |

| McGuire, 2025 [57] | 1.0 (n = 1) | I342V, V475I P160S, Y331H P140L, N540D | A27T, N741A V744A, V541I | V80A | K63E | England (2016) |

ND, not detected; NR, not reported; NT, not tested; NI, not informed. Substitutions strongly associated with penicillin-resistant S. agalactiae are shown in boldface. * Described mutation A95D in the pbp1b gene.

4. S. agalactiae with Reduced β-Lactam Susceptibility

The WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (PBPL, 2024) has been fundamental in guiding global policies, research and development, and investments to address the most urgent threats of antibiotic-resistant pathogens, being essential for public health in the prevention and control of antimicrobial resistance [58,59]. S. agalactiae is listed in the PBPL as a microorganism with a concerning increase in resistance to β-lactams. S. agalactiae is a major cause of pregnancy complications and neonatal morbidity and mortality worldwide, as well as invasive infections in elderly and non-pregnant adults with comorbidities [60]. However, current disease burden data from low- and middle-income countries are sparse, demonstrating that there is still little information on RPS S. agalactiae in these countries. The absence of official protocols from federal governments, insufficient funding, and difficulty of access to health facilities for pregnant women, lack of infrastructure, as well as barriers to data sharing may be responsible for the disparities in research publications in low- and middle-income countries.

Several publications have described S. agalactiae strains with PRS or resistance to β-lactams in Asia, North America, Africa, and Europe. However, there are no published reports of RPS or penicillin-resistant S. agalactiae strains in China—except in Hong Kong [41,51], India, and Central and South America. Detailed characterization of PRS S. agalactiae with reduced susceptibility to β-lactams related to mutations in the pbp2x was first reported in 2008 [3]. The same research group identified strains with other mutations in pbp2x, pbp2a, pbp2b, and pbp1a in the years 2008, 2012, and 2014 [35,44,45]. Also in Japan, other researchers have associated novel mutations in pbp2x and pbp1a with the reduced susceptibility of S. agalactiae strains to penicillin [46,47,53,54,55] (Table 1). These data obtained in Japan demonstrated a significant increase in RPS S. agalactiae strains, as well as the diversity of mutations described in various PBPs. It is necessary to monitor penicillin-resistant/reduced susceptibility strains in order to identify new mutations and multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains that could spread globally.

In Canada, different mutations from those described in Japan were identified in pbp2x, pbp2a, pbp2b, and pbp1a of RPS S. agalactiae strains [42,43]. A total of 28,269 isolates of invasive S. agalactiae infections, collected over 20 years in the United States and identified with reduced sensitivity to β-lactams, were detected across all Active Bacterial Core surveillance sites. The results revealed the emergence of first-step pbp2x mutations conferring reduced susceptibility to β-lactams among S. agalactiae causing invasive disease in the United States [61]. In Mozambique [48], South Korea [49], and Northwest Ethiopia [62], mutations were also identified exclusively in pbp2x. In contrast, in England, mutations were identified in all four PBPs-encoding genes, while in Germany they were found in pbp2x, pbp2b, and pbp1a among RPS S. agalactiae strains (Table 1).

In Hong Kong, China, the first report of RPS S. agalactiae occurred in 2007 [41], and in 2020, a second strain of RPS S. agalactiae was isolated [51], exhibiting mutations in five PBPs-encoding genes produced by S. agalactiae (pbp1a, pbp1b, pbp2a, pbp2b, pbp2x; Table 1). In South Korea, a 24-year study assessed trends in penicillin non-susceptibility in S. agalactiae and demonstrated a statistically significant increase in both the isolation rate of S. agalactiae and penicillin non-susceptibility over time [63]. Data from South Africa in the period 2019–2020 identified one PRS S. agalactiae strain. However, the authors were unable to detect the mutation in the pbp2x gene due to insufficient sequence quality at the PBP2x locus [56]. Continuous exposure to β-lactam antibiotics can contribute to the accumulation of additional mutations, leading to higher levels of resistance. Therefore, elderly individuals and people with comorbidities, who are at higher risk of invasive disease caused by S. agalactiae, should be monitored for increased MIC values to prevent invasive disease caused by PRS S. agalactiae. Furthermore, it is necessary to monitor prior antibiotic exposures to avoid increasing the proportion of RPS S. agalactiae strains and prevent dissemination in hospital and community settings. Surveillance should be continuous, as strains with reduced sensitivity to β-lactams exhibit a high level of successful adaptation to the selective pressure of these antibiotics.

In addition to the S. agalactiae strains identified with reduced susceptibility to β-lactams in different countries, a significant percentage of these bacterial strains also showed resistance to other classes of antimicrobials, being classified as MDR. A pattern of MDR in RPS S. agalactiae isolated from pregnant women receiving prenatal care in Ethiopia in 2021 showed a high frequency of 26.7% for resistance to 3 classes of antimicrobials (penicillin, erythromycin, vancomycin) and 6.7% for resistance to 4 classes of antimicrobials (penicillin, erythromycin, vancomycin, and ceftriaxone) [62]. Results in Japan also showed a significant association between RPS and non-susceptibility to fluoroquinolones and macrolide resistance in clinical isolates of S. agalactiae [37]. MDR S. agalactiae strains were also identified for resistance to β-lactams, tetracycline, fluoroquinolone, vancomycin, and clindamycin in the United States [52]; for penicillin, levofloxacin, erythromycin, clindamycin, and tetracycline in Korea [64]; and for penicillin, erythromycin, clindamycin, and tetracycline [41], in addition to fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides, in Hong Kong [51]. These data demonstrate a limited repertoire of medications for the effective treatment of RPS S. agalactiae infections, highlighting the need for careful drug selection for medical treatment in clinical practice. Therefore, epidemiological research on RPS S. agalactiae strains is urgently needed to improve the clinical management of invasive infections caused by this pathogen. Furthermore, invasive RPS S. agalactiae isolates carry important virulence and resistance genes, demonstrating the need for population-based genomic surveillance to deepen the understanding of the clinical relevance of these invasive S. agalactiae isolates. MDR PRS S. agalactiae isolates retained a core virulence gene repertoire (bibA, fbsA, fbsB, fbsC, cspA, cfb, hylB, scpB, lmb, and the cyl operon), supporting an invasive ability similar to that of the other invasive S. agalactiae penicillin-susceptible [54].

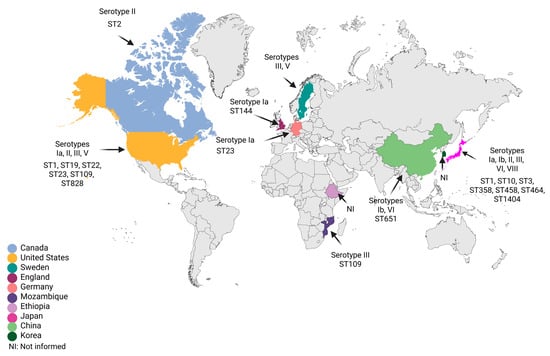

The main publications on S. agalactiae strains with reduced susceptibility to β-lactams performed capsular typing and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) assays to identify the circulating type sequences (STs) in the region. Epidemiological and molecular analyses showed a high diversity of genetic lineages among RPS S. agalactiae isolates. Thus, the map of the main capsular types and STs described to date is represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of reduced susceptibility to penicillin in Streptococcus agalactiae strains with available serotypes and sequence types. Figure created with BioRender.com.

In Japan, there was a predominance of RPS isolates belonging to capsular types Ia, Ib, II, III, VI, and VII, classified within ST1, ST3, ST10, ST358, ST458, ST464, and ST1404 [27,28,29]. In Hong Kong, types Ib/ST651 and VI [41,51]; Mozambique, type III/ST109 [48]; Sweden, types III and V [65]; England, type Ia/ST144 [57]; Germany, type Ia/ST23 [50]; Canada, type II/ST2 [42]; and the United States, types Ia/ST23, II/ST22, III/ST19, III/ST109, III/ST828, and V/ST1 [36,52]. Collectively, we found that RPS S. agalactiae isolates were frequently detected in adults, mainly belonging to serotype III described in North America, Europe, Asia, and Africa, followed by serotype Ia identified in North America, Europe, and Asia. A genomic study of invasive RPS isolates in Japan confirmed the close genomic relationship of RPS isolates of serotype Ia/ST1, as well as the persistence of these isolates at the site of infection for more than 3 weeks, increasing the risk of sepsis in the elderly [34]. The emergence of evolutionary lineages of invasive RPS isolates of serotypes Ia/ST1 and III/ST1 has also been investigated. Some invasive RPS isolates showed the acquisition of mobile genetic elements associated with the antibiotic resistance gene mefA-msrD or aac(6′)-aph(2′′), confirming the increasing trend in the occurrence of RPS among S. agalactiae isolates from various clinical sources [54].

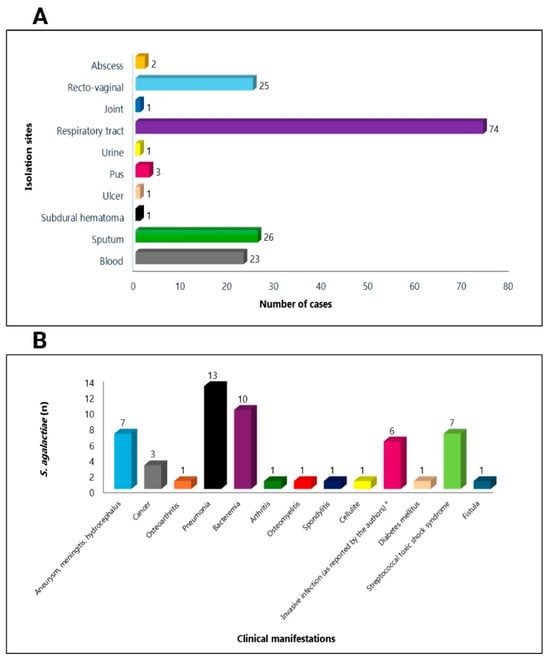

Although there are few studies worldwide that cite the isolation sites and clinical manifestations of PRS S. agalactiae strains, we can verify that the most frequent isolation sites were the respiratory tract [37,44,46], followed by recto-vaginal [62,66], sputum [3,49,53], blood [37,43,47,48,52,54], pus [42,44,47], abscess [50], joint [47], urine [43], ulcer [34], subdural hematoma [35], and wound [51] (Figure 3A). Regarding the clinical manifestations reported in the publications, we observed bacteremia [47,54], pneumonia [44,47,49,53], aneurysm, meningitis, hydrocephalus [34,44,48], invasive infections [36], cancer [44,53], osteomyelitis [43], arthritis, cellulitis and spondylitis [47], diabetes mellitus [53], streptococcal toxic shock syndrome [55], and fistula [52] as the most frequent (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Distribution of the main isolation sites (A) and clinical manifestations (B) of reduced-penicillin susceptibility of Streptococcus agalactiae strains recovered from humans * [36]. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Current guidelines recommend IAP for pregnant women at risk of transmitting S. agalactiae to their newborns, as well as for the treatment of invasive infections in the elderly and adults with comorbidities. The rise in RPS S. agalactiae strains will have a direct impact on clinical medicine, leading doctors to adopt alternative antibiotics, such as clindamycin or erythromycin, which have also shown high resistance rates in S. agalactiae, as well as increased resistance to fluoroquinolones. Furthermore, hospitals and laboratories may need to improve monitoring of S. agalactiae resistance patterns, making changes to treatment protocols based on local resistance trends. Health surveillance programs should track the prevalence of reduced penicillin sensitivity in S. agalactiae, with implications for vaccine development and infection control strategies. Increased awareness among healthcare professionals regarding the emergence of resistant strains is crucial for timely diagnosis and treatment, ensuring patient safety, particularly in high-risk populations and in low- and middle-income countries.

However, important questions remain unanswered. Why have countries with large geographic areas, such as China and India, considered important world economies, not yet identified RPS S. agalactiae strains, while other countries, also with large geographic areas and important world economies, such as the United States and Canada, have already identified RPS S. agalactiae? Similarly, Brazil, as an emerging country, has not yet identified RPS S. agalactiae. The core of this issue may be the screening for S. agalactiae through official protocols implemented in the countries. The United States has implemented the guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) for the identification of S. agalactiae in pregnant women, while in China, there are no standardized guidelines on S. agalactiae screening and prevention [67]. Similarly, Brazil does not have any official protocol for screening pregnant women for S. agalactiae through the public health system [68]. Although the Indian national guidelines for Infection Prevention and Control in Healthcare Facilities, adapted from the WHO, recommend a risk-based approach for S. agalactiae infection prophylaxis, routine antibiotic administration during labor is not recommended [69]. Furthermore, other problems can greatly contribute to the lack of information on RPS S. agalactiae in different countries. Insufficient funding and a lack of research culture mean that many low- and middle-income countries do not prioritize research in their national budgets, and the lack of infrastructure, limited access to equipment, and lack of data archives and computational resources hinder data collection and management, which together are responsible for disparities in information, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

In conclusion, these findings indicate that the isolation rate of PRS S. agalactiae has been rapidly increasing, particularly in Japan. Furthermore, isolation rates of multidrug-resistant RPS S. agalactiae were found to be quite high among all clinical isolates of S. agalactiae. Given the emergence of multidrug-resistant S. agalactiae strains, susceptibility testing and interdisciplinary collaboration between microbiologists and clinicians are crucial for guiding effective antimicrobial therapy and preventing S. agalactiae infections in neonates and adults.

5. Future Perspectives

The increasing isolation of PRS S. agalactiae strains is concerning. Thus, the effectiveness of β-lactams may be compromised, making it necessary to inquire about the validity of PBPs in future therapies against this pathogen. β-lactams mimic the substrates of PBPs; therefore, understanding how the natural substrates of PBPs or partner proteins maintain reactivity at the catalytic site, even in PBPs from resistant bacteria, may provide relevant information for the development of new compounds [11]. Additionally, new molecules may act as adjuvants to restore or maintain the reactivity of PBPs to traditional β-lactams. The next major challenges will involve describing the mechanisms of how PBPs are activated and regulated, as well as identifying protein partners that will help clarify important questions.

Several substances have been analyzed as non-β-lactam PBP inhibitors. Peptidomimetic boronic acid inhibitors have been studied using S. pneumoniae PBP1B as a model enzyme, obtaining promising results. The antibacterial activity of boronates has also shown good results against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA; IC50 = 6.9 μM) [70]. Moreover, xeruborbactam, a cyclic boronic acid β-lactamase inhibitor, was able to bind to PBP1A/PBP1B, PBP2, and PBP3 of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae with IC50s in the range of 40 to 70 μM [71]. Additionally, fragment-based computational strategies have been used to find molecules that non-covalently bind to the catalytic site of PBPs. Molecular docking analyses suggested that quinolones were promising candidates for binding [72]. The creation of a β-peptide oligomer library, through synthetic fermentation, using α-ketoacid-hydroxylamine with a mixture of α-ketoacids and isoxazolidine monomers, led to the identification of peptide 62. Peptide 62 was able to inhibit the growth of Bacillus subtilis with a MIC of 5.7 ug/mL and low toxicity (IC50 above 100 ug/mL) [73].

Another strategy is to use inhibitors against other proteins involved in peptidoglycan synthesis. MraY is an integral membrane protein essential for bacterial growth, responsible for catalyzing the first step in the synthesis of membrane-associated peptidoglycan [74]. Different classes of natural inhibitors have targeted MraY with antibacterial activity, such as capuramycin and tunicamycin, in the search for new inhibitors [75]. Future research should also aim to elucidate the functional consequences of the identified pbp mutations, including their effects on PBP structure, β-lactam binding affinity, and bacterial fitness. Expanded genomic surveillance across underrepresented regions will be essential to determine whether these mutations arise through independent evolutionary events or clonal dissemination. Moreover, it is important to assess the potential progression from first-step mutations to higher levels of β-lactam resistance. Additional studies should also evaluate the impact of these mutations on the activity of other β-lactams, as well as their possible association with virulence determinants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.N.F. and P.E.N.; methodology, L.N.F. and B.A.P.H.; validation, L.S.d.S. and P.E.N.; formal analysis, L.N.F. and P.E.N.; investigation, L.N.F. and B.A.P.H.; resources, B.A.P.H. and L.S.d.S.; data curation, L.S.d.S. and P.E.N.; writing—original draft preparation, L.N.F.; writing—review and editing, L.S.d.S. and P.E.N.; visualization, L.N.F., B.A.P.H. and L.S.d.S.; supervision, P.E.N.; project administration, P.E.N.; funding acquisition, P.E.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors and their work were supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) E-26/210.373/2024, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) 301267/2025-1, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001, and CAPES-PrInt/UERJ 88881.311598/2018-01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| S. agalactiae | Streptococcus agalactiae |

| GBS | Group B Streptococcus |

| IAP | Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| PBPs | Penicillin-binding proteins |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| HMM | High molecular weight |

| LMM | Low molecular weight |

| RPS | Reduced penicillin susceptibility |

| D-Ala | D-alanine |

| L-Lys | L-lysine |

| D-Glu | D-glutamate |

| L-Ala | L-alanine |

| PBPL | Bacterial Priority Pathogens List |

| MDR | Multidrug resistant |

| MLST | Multilocus sequence typing |

| STs | Sequence type |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| KAHA | α-ketoacid-hydroxylamine |

References

- Raabe, V.N.; Shane, A.L. Group B Streptococcus (Streptococcus agalactiae). Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.Y.; Silverman, N.S. Group B Streptococcus in Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 50, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, K.; Suzuki, S.; Wachino, J.; Kurokawa, H.; Yamane, K.; Shibata, N.; Nagano, N.; Kato, H.; Shibayama, K.; Arakawa, Y. First Molecular Characterization of Group B Streptococci with Reduced Penicillin Susceptibility. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 2890–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters Version 15.0, Valid from 2025-01-01. Available online: https://aurosan.de/images/mediathek/servicematerial/EUCAST_RefStaemme_Sollwerte.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 35th ed.; CLSI Supplement M100; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Laible, G.; Spratt, B.G.; Hakenbeck, R. Interspecies Recombinational Events during the Evolution of Altered PBP 2x Genes in Penicillin-resistant Clinical Isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 1991, 5, 1993–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvez, P.; Breukink, E.; Roper, D.I.; Dib, M.; Contreras-Martel, C.; Zapun, A. Substitutions in PBP2b from β-Lactam-Resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae Have Different Effects on Enzymatic Activity and Drug Reactivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 2854–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goffin, C.; Ghuysen, J.-M. Multimodular Penicillin-Binding Proteins: An Enigmatic Family of Orthologs and Paralogs. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998, 62, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvage, E.; Terrak, M. Glycosyltransferases and Transpeptidases/Penicillin-Binding Proteins: Valuable Targets for New Antibacterials. Antibiotics 2016, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazos, M.; Peters, K. Peptidoglycan; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 127–168. [Google Scholar]

- Miyachiro, M.M.; Contreras-Martel, C.; Dessen, A. Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBPs) and Bacterial Cell Wall Elongation Complexes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 273–289. [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby, M.-A.W.; Dokla, E.M.E.; Serya, R.A.T.; Abouzid, K.A.M. Penicillin Binding Protein 2a: An Overview and a Medicinal Chemistry Perspective. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 199, 112312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.; Sibold, C.; Hakenbeck, R. Relatedness of Penicillin-Binding Protein 1a Genes from Different Clones of Penicillin-Resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae Isolated in South Africa and Spain. EMBO J. 1992, 11, 3831–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.M.; Klugman, K.P. Alterations in Penicillin-Binding Protein 2B from Penicillin-Resistant Wild-Type Strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995, 39, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowson, C.G.; Hutchison, A.; Spratt, B.G. Extensive Re-modelling of the Transpeptidase Domain of Penicillin-binding Protein 2B of a Penicillin-resistant South African Isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 1989, 3, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, J.; Beall, B.; Linse, S.; Lindahl, G. Extreme Sequence Divergence but Conserved Ligand-Binding Specificity in Streptococcus pyogenes M Protein. PLoS Pathog. 2006, 2, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yerramilli, P.; Pruitt, L.; Mishra, A.; Olsen, R.J.; Beres, S.B.; Waller, A.S.; Musser, J.M. Functional Insights into the High-Molecular-Mass Penicillin-Binding Proteins of Streptococcus agalactiae Revealed by Gene Deletion and Transposon Mutagenesis Analysis. J. Bacteriol. 2021, 203, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, F.; Nolte, O.; Bergmann, C.; Ip, M.; Hakenbeck, R. Crossing the Barrier: Evolution and Spread of a Major Class of Mosaic Pbp2x in Streptococcus pneumoniae, S. mitis and S. oralis. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 297, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, B.; Duchêne, M.-C.; Haustenne, G.L.; Pérez-Núñez, D.; Chapot-Chartier, M.-P.; De Bolle, X.; Guédon, E.; Hols, P.; Hallet, B. PBP2b Plays a Key Role in Both Peripheral Growth and Septum Positioning in Lactococcus lactis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsui, H.T.; Boersma, M.J.; Vella, S.A.; Kocaoglu, O.; Kuru, E.; Peceny, J.K.; Carlson, E.E.; VanNieuwenhze, M.S.; Brun, Y.V.; Shaw, S.L.; et al. Pbp2x Localizes Separately from Pbp2band Other Peptidoglycan Synthesis Proteins during Later Stages of Cell Division of Sreptococcus pneumoniae D39. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 94, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musser, J.M.; Beres, S.B.; Zhu, L.; Olsen, R.J.; Vuopio, J.; Hyyryläinen, H.-L.; Gröndahl-Yli-Hannuksela, K.; Kristinsson, K.G.; Darenberg, J.; Henriques-Normark, B.; et al. Reduced In Vitro Susceptibility of Streptococcus pyogenes to β-Lactam Antibiotics Associated with Mutations in the Pbp2x Gene Is Geographically Widespread. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e01993-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamsås, G.A.; Restelli, M.; Ducret, A.; Freton, C.; Garcia, P.S.; Håvarstein, L.S.; Straume, D.; Grangeasse, C.; Kjos, M. A CozE Homolog Contributes to Cell Size Homeostasis of Streptococcus pneumoniae. mBio 2020, 11, e02461-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A.; Popham, D.L.; Carl, D.J.; Lauth, X.; Nizet, V.; Jones, A.L. Penicillin-Binding Protein 1a Promotes Resistance of Group B Streptococcus to Antimicrobial Peptides. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 6179–6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.L.; Mertz, R.H.; Carl, D.J.; Rubens, C.E. A Streptococcal Penicillin-Binding Protein Is Critical for Resisting Innate Airway Defenses in the Neonatal Lung. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 3196–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.L.; Knoll, K.M.; Rubens, C.E. Identification of Streptococcus Agalactiae Virulence Genes in the Neonatal Rat Sepsis Model Using Signature-tagged Mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2000, 37, 1444–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boes, A.; Kerff, F.; Herman, R.; Touze, T.; Breukink, E.; Terrak, M. The Bacterial Cell Division Protein Fragment EFtsN Binds to and Activates the Major Peptidoglycan Synthase PBP1b. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 18256–18265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.; Strynadka, N.C.J. Structural Basis for the β Lactam Resistance of PBP2a from Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002, 9, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji-Olulana, A.F.; Wacnik, K.; Lafage, L.; Pasquina-Lemonche, L.; Tinajero-Trejo, M.; Sutton, J.A.F.; Bilyk, B.; Irving, S.E.; Portman Ross, C.J.; Meacock, O.J.; et al. Two Codependent Routes Lead to High-Level MRSA. Science 2024, 386, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjodt, M.; Brock, K.; Dobihal, G.; Rohs, P.D.A.; Green, A.G.; Hopf, T.A.; Meeske, A.J.; Srisuknimit, V.; Kahne, D.; Walker, S.; et al. Structure of the Peptidoglycan Polymerase RodA Resolved by Evolutionary Coupling Analysis. Nature 2018, 556, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohs, P.D.A.; Buss, J.; Sim, S.I.; Squyres, G.R.; Srisuknimit, V.; Smith, M.; Cho, H.; Sjodt, M.; Kruse, A.C.; Garner, E.C.; et al. A Central Role for PBP2 in the Activation of Peptidoglycan Polymerization by the Bacterial Cell Elongation Machinery. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimoto, A.T.; Dao, T.H.; Jia, Q.; Ortiz-Marquez, J.C.; Echlin, H.; Vogel, P.; van Opijnen, T.; Rosch, J.W. Interspecies Recombination, Not de Novo Mutation, Maintains Virulence after β-Lactam Resistance Acquisition in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapun, A.; Contreras-Martel, C.; Vernet, T. Penicillin-Binding Proteins and β-Lactam Resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauvage, E.; Kerff, F.; Terrak, M.; Ayala, J.A.; Charlier, P. The Penicillin-Binding Proteins: Structure and Role in Peptidoglycan Biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 234–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, N.; Kimura, K.; Nagano, Y.; Yakumaru, H.; Arakawa, Y. Molecular Characterization of Group B Streptococci with Reduced Penicillin Susceptibility Recurrently Isolated from a Sacral Decubitus Ulcer. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009, 64, 1326–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, N.; Nagano, Y.; Kimura, K.; Tamai, K.; Yanagisawa, H.; Arakawa, Y. Genetic Heterogeneity in Pbp Genes among Clinically Isolated Group B Streptococci with Reduced Penicillin Susceptibility. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 4258–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, B.J.; Chochua, S.; Gertz, R.E.; Hawkins, P.A.; Ricaldi, J.; Li, Z.; Walker, H.; Tran, T.; Rivers, J.; Mathis, S.; et al. Short-Read Whole Genome Sequencing for Determination of Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms and Capsular Serotypes of Current Invasive Streptococcus agalactiae Recovered in the USA. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 574.e7–574.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, K.; Nagano, N.; Nagano, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Wachino, J.; Shibayama, K.; Arakawa, Y. High Frequency of Fluoroquinolone- and Macrolide-Resistant Streptococci among Clinically Isolated Group B Streptococci with Reduced Penicillin Susceptibility. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesnel, L.; Pernot, L.; Lemaire, D.; Champelovier, D.; Croizé, J.; Dideberg, O.; Vernet, T.; Zapun, A. The Structural Modifications Induced by the M339F Substitution in PBP2x from Streptococcus pneumoniae Further Decreases the Susceptibility to β-Lactams of Resistant Strains. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 44448–44456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouz, N.; Gordon, E.; Di Guilmi, A.-M.; Petit, I.; Pétillot, Y.; Dupont, Y.; Hakenbeck, R.; Vernet, T.; Dideberg, O. Identification of a Structural Determinant for Resistance to β-Lactam Antibiotics in Gram-Positive Bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 13403–13406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, K.; Nagano, N.; Arakawa, Y. Classification of Group B Streptococci with Reduced β-Lactam Susceptibility (GBS-RBS) Based on the Amino Acid Substitutions in PBPs. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 1601–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.W.; Tse, C.; Tsang, G.K.-L.; So, D.K.-S.; Fung, J.T.-L.; Lo, J.Y.-C. Invasive Group B Streptococcus Isolates Showing Reduced Susceptibility to Penicillin in Hong Kong. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 60, 1407–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreau, C.; Lecours, R.; Ismail, J.; Gagnon, S.; Jette, L.; Roger, M. Prosthetic Hip Joint Infection with a Streptococcus agalactiae Isolate Not Susceptible to Penicillin G and Ceftriaxone. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 594–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longtin, J.; Vermeiren, C.; Shahinas, D.; Tamber, G.S.; McGeer, A.; Low, D.E.; Katz, K.; Pillai, D.R. Novel Mutations in a Patient Isolate of Streptococcus agalactiae with Reduced Penicillin Susceptibility Emerging after Long-Term Oral Suppressive Therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 2983–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, N.; Nagano, Y.; Toyama, M.; Kimura, K.; Tamura, T.; Shibayama, K.; Arakawa, Y. Nosocomial Spread of Multidrug-Resistant Group B Streptococci with Reduced Penicillin Susceptibility Belonging to Clonal Complex 1. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagano, N.; Nagano, Y.; Toyama, M.; Kimura, K.; Shibayama, K.; Arakawa, Y. Penicillin-Susceptible Group B Streptococcal Clinical Isolates with Reduced Cephalosporin Susceptibility. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 3406–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki, T.; Kimura, K.; Reid, M.E.; Miyazaki, A.; Banno, H.; Jin, W.; Wachino, J.; Yamada, K.; Arakawa, Y. High Isolation Rate of MDR Group B Streptococci with Reduced Penicillin Susceptibility in Japan. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 2725–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morozumi, M.; Wajima, T.; Takata, M.; Iwata, S.; Ubukata, K. Molecular Characteristics of Group B Streptococci Isolated from Adults with Invasive Infections in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 2695–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigaúque, B.; Kobayashi, M.; Vubil, D.; Nhacolo, A.; Chaúque, A.; Moaine, B.; Massora, S.; Mandomando, I.; Nhampossa, T.; Bassat, Q.; et al. Invasive Bacterial Disease Trends and Characterization of Group B Streptococcal Isolates among Young Infants in Southern Mozambique, 2001–2015. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, A.; Kim, C.-K.; Kimura, K.; Arakawa, Y.; Hur, M.; Yun, Y.-M.; Moon, H.-W. First Case in Korea of Group B Streptococcus With Reduced Penicillin Susceptibility Harboring Amino Acid Substitutions in Penicillin-Binding Protein 2X. Ann. Lab. Med. 2019, 39, 414–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, M.; Mamede, R.; Levina, N.; Helwig, P.; Vila-Cerqueira, P.; Carriço, J.A.; Melo-Cristino, J.; Ramirez, M.; Martins, E.R. Heterogeneity of Penicillin-Non-Susceptible Group B Streptococci Isolated from a Single Patient in Germany. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Sapugahawatte, D.; Yang, Y.; Wong, K.; Lo, N.; Ip, M. Multidrug-Resistant Streptococcus agalactiae Strains Found in Human and Fish with High Penicillin and Cefotaxime Non-Susceptibilities. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, L.; Chochua, S.; Li, Z.; Mathis, S.; Rivers, J.; Metcalf, B.; Ryan, A.; Alden, N.; Farley, M.M.; Harrison, L.H.; et al. Multistate, Population-Based Distributions of Candidate Vaccine Targets, Clonal Complexes, and Resistance Features of Invasive Group B Streptococci Within the United States, 2015–2017. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, N.; Kinjo, T.; Uechi, K.; Parrott, G.; Nakamatsu, M.; Tateyama, M.; Fujita, J. Clinical and Bacterial Features of Group B Streptococci with Reduced Penicillin Susceptibility from Respiratory Specimens: A Case–Control Study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, S.; Nagano, Y.; Takizawa, S.; Sakaguchi, K.; Soga, E.; Hayashi, W.; Tanabe, M.; Denda, T.; Kimura, K.; Arakawa, Y.; et al. Genomic Traits Associated with Virulence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Invasive Group B Streptococcus Isolates with Reduced Penicillin Susceptibility from Elderly Adults. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00568-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikebe, T.; Okuno, R.; Uchitani, Y.; Takano, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Otsuka, H.; Kazawa, Y.; Fujita, S.; Kobayashi, A.; Date, Y.; et al. Serotype Distribution and Antimicrobial Resistance of Streptococcus agalactiae Isolates in Nonpregnant Adults with Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome in Japan in 2014 to 2021. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e04987-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntozini, B.; Walaza, S.; Metcalf, B.; Hazelhurst, S.; de Gouveia, L.; Meiring, S.; Mogale, D.; Mtshali, S.; Ismail, A.; Ndlangisa, K.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Invasive Group B Streptococcus in South Africa, 2019–2020. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 231, e697–e707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, E.; Ready, D.; Ellaby, N.; Potterill, I.; Pike, R.; Hopkins, K.L.; Guy, R.L.; Lamagni, T.; Mack, D.; Scobie, A.; et al. A Case of Penicillin-Resistant Group B Streptococcus Isolated from a Patient in the UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization WHO Bacterial Priority List, 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Sati, H.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Hansen, P.; Garlasco, J.; Campagnaro, E.; Boccia, S.; Castillo-Polo, J.A.; Magrini, E.; Garcia-Vello, P.; et al. The WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024: A Prioritisation Study to Guide Research, Development, and Public Health Strategies against Antimicrobial Resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J. Group B Streptococcus: Virulence Factors and Pathogenic Mechanism. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; McGee, L.; Chochua, S.; Apostol, M.; Alden, N.B.; Farley, M.M.; Harrison, L.H.; Lynfield, R.; Vagnone, P.S.; Smelser, C.; et al. Low but Increasing Prevalence of Reduced Beta-Lactam Susceptibility Among Invasive Group B Streptococcal Isolates, US Population-Based Surveillance, 1998–2018. Open Forum. Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofaa634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemayehu, G.; Geteneh, A.; Dessale, M.; Ayalew, E.; Demeke, G.; Reta, A.; Kiros, M. High Prevalence of Penicillin-Resistant Group B Streptococcus among Pregnant Women in Northwest Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Whang, D.H.; Um, T.-H.; Cho, C.R.; Chang, J. Increase in Penicillin Non-Susceptibility in Group B Streptococci Alongside Rising Isolation Rates—Based on 24 Years of Clinical Data from a Single University Hospital. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; So, M.-K.; Kim, Y.-H.; Chung, H.-S. Characterization of Penicillin-Non-Susceptible, Multidrug-Resistant Streptococcus agalactiae Using Whole-Genome Sequencing. Curr. Microbiol. 2025, 82, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, E.; Berg, S.; Bergseng, H.; Bergh, K.; Valsö-lyng, R.; Trollfors, B. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Invasive Group B Streptococcal Isolates from South-West Sweden 1988–2001. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 40, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burcham, L.R.; Spencer, B.L.; Keeler, L.R.; Runft, D.L.; Patras, K.A.; Neely, M.N.; Doran, K.S. Determinants of Group B streptococcal virulence potential amongst vaginal clinical isolates from pregnant women. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Deng, Q.; Huang, L.; Chang, C.-Y.; Zhong, H.; Xie, Y.; Guan, X.; Liu, H. Diagnostic Performance of Various Methodologies for Group B Streptococcus Screening in Pregnant Woman in China. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 651968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, B.A.D.S.; Lannes-Costa, P.S.; Viana, A.S.; Santos, G.D.S.; Leobons, M.B.G.P.; Ferreira-Carvalho, B.T.; Nagao, P.E. Molecular Characterization, Antimicrobial Resistance and Invasion of Epithelial Cells by Streptococcus agalactiae Strains Isolated from Colonized Pregnant Women and Newborns in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 135, lxae200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghia, C.; Rambhad, G. Disease Burden Due to Group B Streptococcus in the Indian Population and the Need for a Vaccine—A Narrative Review. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, 20499361211045253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Martel, C.; Amoroso, A.; Woon, E.C.Y.; Zervosen, A.; Inglis, S.; Martins, A.; Verlaine, O.; Rydzik, A.M.; Job, V.; Luxen, A.; et al. Structure-Guided Design of Cell Wall Biosynthesis Inhibitors That Overcome β-Lactam Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). ACS Chem. Biol. 2011, 6, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Tsivkovski, R.; Pogliano, J.; Tsunemoto, H.; Nelson, K.; Rubio-Aparicio, D.; Lomovskaya, O. Intrinsic Antibacterial Activity of Xeruborbactam In Vitro: Assessing Spectrum and Mode of Action. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e00879-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Daniel, P.I.; Peng, Z.; Pi, H.; Testero, S.A.; Ding, D.; Spink, E.; Leemans, E.; Boudreau, M.A.; Yamaguchi, T.; Schroeder, V.A.; et al. Discovery of a New Class of Non-β-Lactam Inhibitors of Penicillin-Binding Proteins with Gram-Positive Antibacterial Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3664–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepek, I.A.; Cao, T.; Koetemann, A.; Shimura, S.; Wollscheid, B.; Bode, J.W. Antibiotic Discovery with Synthetic Fermentation: Library Assembly, Phenotypic Screening, and Mechanism of Action of β-Peptides Targeting Penicillin-Binding Proteins. ACS Chem. Biol. 2019, 14, 1030–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrakala, B.; Shandil, R.K.; Mehra, U.; Ravishankar, S.; Kaur, P.; Usha, V.; Joe, B.; deSousa, S.M. High-Throughput Screen for Inhibitors of Transglycosylase and/or Transpeptidase Activities of Escherichia coli Penicillin Binding Protein 1b. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, H.; Ben Othman, R.; Le Corre, L.; Poinsot, M.; Oliver, M.; Amoroso, A.; Joris, B.; Touzé, T.; Auger, R.; Calvet-Vitale, S.; et al. New MraYAA Inhibitors with an Aminoribosyl Uridine Structure and an Oxadiazole. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.