Randomized, Negative-Controlled Pilot Study on the Treatment of Intramammary Staphylococcus aureus Infections in Dairy Cows with a Bacteriophage Cocktail

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Study Population and Enrollment

2.2. Farm 1—Tolerance Trial

2.3. Farm 2—Efficacy Trial

3. Discussion

Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethical Approval

4.2. Farms and Animals

4.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

4.4. Study Design and Treatment

4.4.1. Tolerability Assessment (Farm 1)

4.4.2. Efficacy Trial Design and Randomization (Farm 2)

4.4.3. Treatment Protocol

4.4.4. Sampling Timeline and Outcome Definitions

4.5. Microbiological Analyses/Laboratory Procedure

4.6. Bacteriophage Mixture

4.7. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zinke, C.; Cormier, L.; Shu, L.; Krömker, V. Zur Nachweishäufigkeit von methicillin-resistenten Staphylococcus aureus und methicillin-resistenten koagulase-negativen Staphylokokken spp. in ökologischen und konventionellen Milchviehbetrieben. In Proceedings of the Berlin-Brandenburgischer Rindertag, Berlin, Germany, 7–9 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pankey, J.W. Hygiene at milking time in the prevention of bovine mastitis. Br. Vet. J. 1989, 145, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woudstra, S.; Wente, N.; Zhang, Y.; Leimbach, S.; Kirkeby, C.; Gussmann, M.K.; Krömker, V. Reservoirs of Staphylococcus spp. and Streptococcus spp. Associated with Intramammary Infections of Dairy Cows. Pathogens 2023, 12, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenhagen, B.A.; Köster, G.; Wallmann, J.; Heuwieser, W. Prevalence of mastitis pathogens and their resistance against antimicrobial agents in dairy cows in Brandenburg, Germany. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 2542–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, J.J.; Pacan, J.C.; Carson, M.E.; Leslie, K.E.; Griffiths, M.W.; Sabour, P.M. Efficacy and pharmacokinetics of bacteriophage therapy in treatment of subclinical Staphylococcus aureus mastitis in lactating dairy cattle. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 2912–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönborn, S.; Krömker, V. Detection of the biofilm component polysaccharide intercellular adhesin in Staphylococcus aureus infected cow udders. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 196, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslantaş, Ö.; Demir, C. Investigation of the antibiotic resistance and biofilm-forming ability of Staphylococcus aureus from subclinical bovine mastitis cases. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 8607–8613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmenger, A.; Krömker, V. Characterization, cure rates and associated risks of clinical mastitis in Northern Germany. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sol, J.; Sampimon, O.C.; Snoep, J.J.; Schukken, Y.H. Factors associated with bacteriological cure after dry cow treatment of subclinical staphylococcal mastitis with antibiotics. J. Dairy Sci. 1994, 77, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sol, J.; Sampimon, O.C.; Snoep, J.J.; Schukken, Y.H. Factors associated with bacteriological cure during lactation after therapy for subclinical mastitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. J. Dairy Sci. 1997, 80, 2803–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingwell, R.T.; Leslie, K.E.; Duffield, T.F.; Schukken, Y.H.; DesCoteaux, L.; Keefe, G.P.; Kelton, D.F.; Lissemore, K.D.; Shewfelt, W.; Dick, P.; et al. Efficacy of intramammary tilmicosin and risk factors for cure of Staphylococcus aureus infection in the dry period. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deluyker, H.A.; Van Oye, S.N.; Boucher, J.F. Factors affecting cure and somatic cell count after pirlimycin treatment of subclinical mastitis in lactating cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkema, H.W.; Schukken, Y.H.; Zadoks, R.N. Invited Review: The role of cow, pathogen, and treatment regimen in the therapeutic success of bovine Staphylococcus aureus mastitis. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 1877–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall, S.; Clausen, L.M.; Hussein, H.M.; Compton, C.W.R. Therapy of Subclinical Mastitis during Lactation. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bragg, R.; van der Westhuizen, W.; Lee, J.Y.; Coetsee, E.; Boucher, C. Bacteriophages as potential treatment option for antibiotic resistant bacteria. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014, 807, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clokie, M.R.J.; Millard, A.D.; Letarov, A.V.; Heaphy, S. Phages in nature. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goode, D.; Allen, V.M.; Barrow, P.A. Reduction of experimental Salmonella and Campylobacter contamination of chicken skin by application of lytic bacteriophages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 5032–5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, J.E.; Oblinger, J.L.; Bitton, G. Recovery of Coliphages from Chicken, Pork Sausage and Delicatessen Meats. J. Food Prot. 1984, 47, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruttin, A.; Brüssow, H. Human volunteers receiving Escherichia coli phage T4 orally: A safety test of phage therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2874–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sarker, S.A.; McCallin, S.; Barretto, C.; Berger, B.; Pittet, A.C.; Sultana, S.; Krause, L.; Huq, S.; Bibiloni, R.; Bruttin, A.; et al. Oral T4-like phage cocktail application to healthy adult volunteers from Bangladesh. Virology 2012, 434, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titze, I.; Lehnherr, T.; Lehnherr, H.; Krömker, V. Efficacy of Bacteriophages Against Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Bovine Mastitis. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nale, J.Y.; McEwan, N.R. Bacteriophage Therapy to Control Bovine Mastitis: A Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sol, J.; Sampimon, O.C.; Barkema, H.W.; Schukken, Y.H. Factors associated with cure after therapy of clinical mastitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. J. Dairy Sci. 2000, 83, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinkels, J.M.; Cox, P.; Schukken, Y.H.; Lam, T.J. Efficacy of extended cefquinome treatment of clinical Staphylococcus aureus mastitis. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 4983–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinkels, J.M.; Krömker, V.; Lam, T.J. Efficacy of standard vs. extended intramammary cefquinome treatment of clinical mastitis in cows with persistent high somatic cell counts. J. Dairy Res. 2014, 81, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truchetti, G.; Bouchard, E.; Descôteaux, L.; Scholl, D.; Roy, J.P. Efficacy of extended intramammary ceftiofur therapy against mild to moderate clinical mastitis in Holstein dairy cows: A randomized clinical trial. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2014, 78, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ziesch, M.; Krömker, V. Factors influencing bacteriological cure after antibiotic therapy of clinical mastitis. Milchwissenschaft 2016, 69, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Krömker, V.; Friedrich, J.; Klocke, D. Ausscheidung und Nachweis von Staphylococcus aureus über Milch aus infizierten Milchdrüsenvierteln. Tierärztl. Prax. 2008, 6, 389–392. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, M.; Paduch, J.H.; Grieger, A.S.; Mansion-de Vries, E.; Knorr, N.; Zinke, C.; Teich, K.; Krömker, V. Heilungsraten chronischer subklinischer Staphylococcus aureus-Mastitiden nach antibiotischer Therapie bei laktierenden Milchkühen [Cure rates of chronic subclinical Staphylococcus aureus mastitis in lactating dairy cows after antibiotic therapy]. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 2013, 126, 291–296. (In German) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- EMEA (The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products). VICH Topic GL9 (GCP): Guideline on Good Clinical Practices; The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- EMA (European Medicines Agency); Committee for Veterinary Medicinal Products (CVMP). Guideline on the Conduct of Efficacy Studies for Intramammary Products for Use in Cattle; EMA/CVMP/344/1999-Rev.3, 21 February 2025; European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- German Veterinary Medical Association. Guidelines For the Control of Bovine Mastitis as a Herd Problem, 5th ed.; German Veterinary Association: Gießen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Heeschen, W.; Reichmuth, J.; Tolle, A.; Zeider, H. Die Konservierung von Milchproben zur bakteriologischen, zytologischen und hemmstoffbiologischen Untersuchung. Milchwissenschaft 1969, 24, 729–734. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, L.P.; Lemma, F.; Koylass, M.; Rogers, J.; Ayling, R.D.; Worth, D.; Klita, M.; Steventon, A.; Line, K.; Wragg, P.; et al. Evaluation of MALDI-ToF as a method for the identification of bacteria in the veterinary diagnostic laboratory. Res. Vet. Sci. 2015, 101, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

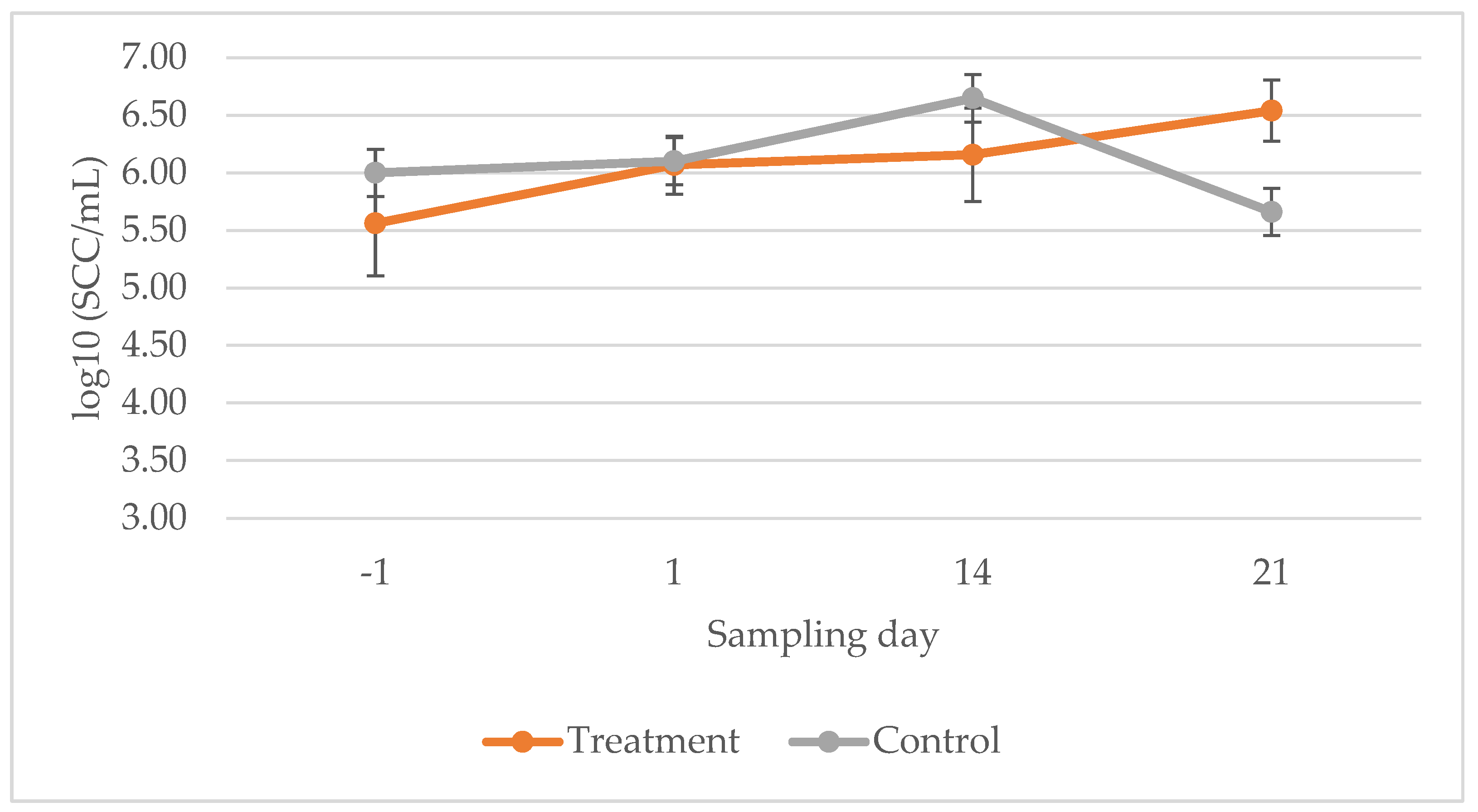

| Sampling Day | −1 1 | 1 2 | Cured | 14 3 | 21 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | 5.56 ± 0.22 4 | 6.07 ± 0.18 | Yes | 6.08 ± 1.23 | 6.63 ± 0.27 |

| No | 5.86 ± 0.80 | 6.50 ± 0.45 | |||

| Control | 6.00 ± 0.46 | 6.10 ± 0.25 | Yes | 7.18 ± 0.16 | 7.00 ± 0.01 |

| No | 6.02 ± 0.33 | 5.66 ± 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Krömker, V.; Leimbach, S.; Tellen, A.; Wente, N.; Schmidt, J.; Lehnherr, H.; Nankemann, F. Randomized, Negative-Controlled Pilot Study on the Treatment of Intramammary Staphylococcus aureus Infections in Dairy Cows with a Bacteriophage Cocktail. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010032

Krömker V, Leimbach S, Tellen A, Wente N, Schmidt J, Lehnherr H, Nankemann F. Randomized, Negative-Controlled Pilot Study on the Treatment of Intramammary Staphylococcus aureus Infections in Dairy Cows with a Bacteriophage Cocktail. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrömker, Volker, Stefanie Leimbach, Anne Tellen, Nicole Wente, Janina Schmidt, Hansjörg Lehnherr, and Franziska Nankemann. 2026. "Randomized, Negative-Controlled Pilot Study on the Treatment of Intramammary Staphylococcus aureus Infections in Dairy Cows with a Bacteriophage Cocktail" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010032

APA StyleKrömker, V., Leimbach, S., Tellen, A., Wente, N., Schmidt, J., Lehnherr, H., & Nankemann, F. (2026). Randomized, Negative-Controlled Pilot Study on the Treatment of Intramammary Staphylococcus aureus Infections in Dairy Cows with a Bacteriophage Cocktail. Antibiotics, 15(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010032