Abstract

Background/Objectives: We investigated multimodal strategies to reduce neonatal ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and antimicrobial use across three periods: period 1 (2014–2017), environmental cleaning with sodium hypochlorite, installation of heat and moisture exchangers, elective high frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) as the primary invasive mode, and nasal HFOV after extubation; period 2 (2018–2020), oral care with maternal milk; and period 3 (2021–2024), nasal synchronized intermittent positive pressure ventilation after extubation. Methods: We conducted a quasi-experimental study of all neonates admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit in Thailand. We compared the trends in VAP and antimicrobial use rates using interrupted time-series analysis with segmented regression. Results: During the 11-year study period, 45.6% of neonates were intubated (2470/5414), and the ventilator utilization ratio was 0.19 (17,820 ventilator days/95,151 patient days). The overall VAP incidence was 4.55 per 1000 ventilator days. The yearly VAP incidence density ratio was significantly lower than in 2014. The baseline trend of VAP incidence and colistin use decreased significantly during period 1; nonetheless, the level and slope did not differ significantly between periods 1, 2, and 3. Conclusions: Tailored implementations, namely environmental decontamination, ventilator circuit care, elective HFOV, and nasal HFOV, reduced VAP and colistin use during period 1. Moreover, additive interventions, including oral care in period 2 and nasal synchronized intermittent positive pressure ventilation in period 3, achieved sustained VAP reduction and limited colistin prescriptions in period 1.

1. Introduction

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a common healthcare-associated infection in neonates attributable to immature respiratory centers and limited diaphragmatic strength. Neonatal VAP consequences include morbidity (bronchopulmonary dysplasia [BPD]), mortality, increased length of stay in the NICU and hospital costs [1]. VAP in neonates differs from pediatric and adult cases; neonates with respiratory failure are usually intubated with an uncuffed endotracheal tube. Additionally, daily oral hygiene with chlorhexidine mouth rinse or gel has been incorporated into routine neonatal care for intubated newborns.

The number of vulnerable preterm infants has increased with sophisticated care; nevertheless, they remain immunocompromised hosts and have underdeveloped organs which necessitate prolonged invasive device use and procedures during admission. According to the International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC), the ventilator utilization ratio (VUR) in neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) settings increased from 0.14 in 2004–2009 [2] to 0.23 in 2012–2017 [3]. The imperative for robust infection prevention and control (IPC) of VAP poses a formidable challenge in the NICU and in high multidrug-resistant (MDR) and resource-limited areas. Specifically, the IPC of neonatal VAP can be categorized into general and specific elements [1].

Bundle elements include stringent hand hygiene, improved nutrition and feeding, closed tracheal suction system, appropriate patient positioning, meticulous management of ventilator circuits (changes when visibly soiled), oral care with maternal milk [4,5], environmental cleaning, and daily assessment of readiness to extubate (early extubation) [1]. Ventilator bundle care is generally low-risk and intuitive; nonetheless, none of the specific elements are supported by substantial research or evidence in the neonatal population [6]. IPC for neonatal care differs from that for children or adults because of immature immunity, incubator use, and poor oral care. Notably, heat and moisture exchanger (HME) circuits may reduce condensate in ventilator circuits by offsetting the temperature difference between the NICU environment and the incubator. A previous meta-analysis reported that oral care with maternal milk reduces VAP incidence [7].

Key respiratory concepts for assisted ventilation include gentle ventilation (permissive hypercapnia [PaCO2 50–60 mmHg] and defined oxygen saturation targets [91–95%]) [8], early extubation (daily assessment and judicious minimization of invasive ventilation duration), and full support of noninvasive ventilation (NIV). Emerging NIV modes include nasal high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (nHFOV) [9,10] and nasal synchronized intermittent positive pressure ventilation (nSIPPV) [11]. Importantly, meta-analyses suggest that both nHFOV and n(S)IPPV reduce reintubation rates compared with nasal continuous positive airway pressure (nCPAP); nSIPPV may be the most effective post-extubation support mode. Nonetheless, current evidence is limited to small studies [12].

Acinetobacter baumannii, particularly carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii (CRAB), is a common VAP pathogen in both adults and neonates in Southeast Asia [13,14,15]. Most CRAB pathogens are colistin-susceptible. Intravenous colistin administration is an empirical antimicrobial therapy used in the NICU in highly endemic areas [16,17,18].

Ventilator bundle care is routine in neonatal care. Additionally, new NIV modes prevent reintubation and may reduce VAP rates and broad-spectrum antimicrobial use. We applied core elements of antimicrobial stewardship and addressed knowledge gaps through a multidisciplinary approach in a quasi-experimental study conducted over three periods in a NICU in Thailand. IPC practices in period 1 (2014–2017: environmental cleaning, installation of HME, HFOV as the primary mode, and nHFOV), period 2 (2018–2020: oral care with maternal milk), and period 3 (2021–2024: nSIPPV) were implemented to assess the effects of specific bundles on neonatal VAP and colistin use.

2. Results

Over 11 years, 5414 and 2470 neonates were admitted and intubated, respectively. The number of ventilator days (VD) was 17,820, and the median (interquartile range) duration of intubation was 4 (1–7) days. The baseline characteristics and outcomes during periods 1, 2, and 3 are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes during periods 1, 2, and 3.

The median gestational age (GA) in period 3 was higher than that in periods 1 and 2. Moreover, the percentages of respiratory distress syndrome and intubated neonates in period 3 were lower than those in periods 1 and 2. The overall antimicrobial use rate (AUR) was 29.1% (27,663 antimicrobial days/95,151 patient days). The percentage of composite outcomes (death or moderate-to-severe BPD) and number of neonates who received total antimicrobials, including 3rd-generation cephalosporins and colistin, decreased from periods 1 to 3.

Over 11 years, the percentage of intubated neonates, VUR, and VAP incidence were 45.6%, 0.19, and 4.55 per 1000 VDs, respectively. VAP incidences in periods 1, 2, and 3 were 8.67, 2.11, and 1.57 per 1000 VDs, respectively. The incidence density ratios of VAP were significantly lower in periods 2 and 3 than in period 1 (Table 2).

Table 2.

The number of intubated neonates, ventilator utilization ratio, and incidence density ratio of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) in each year and period.

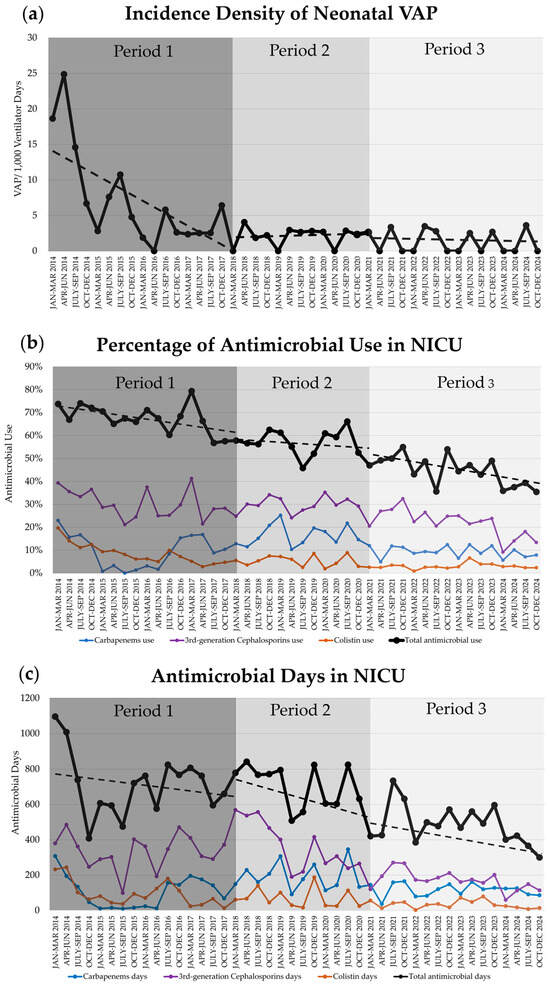

As displayed in Table 3 and Figure 1, the baseline trends of the incidence density of VAP, VUR, and colistin use significantly decreased during period 1. The baseline trend in period 2 and the change in slope in period 2, compared with those in period 1, of the use of 3rd-generation cephalosporins were significantly reduced.

Table 3.

Baseline trend, change in level, and change in slope for the incidence density ratio of ventilator-associated pneumonia, ventilator utilization ratio, and antimicrobial use.

Figure 1.

Trends (dashed line) of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and antimicrobial use during periods 1, 2, and 3 in neonatal intensive care unit (NICU): (a) Incidence density of neonatal VAP; (b) The percentage of neonates who used antimicrobial therapy (Black: 1 or more of any antimicrobials [total]; Purple: 3rd-generation cephalosporins; Blue: carbapenems; Orange: colistin); (c) The duration of accumulative antimicrobial days. NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia.

3. Discussion

Multimodal interventions, including general and specific elements—environmental cleaning, HME circuit, elective HFOV, and nHFOV in period 1; oral care in period 2; and nSIPPV in period 3—can reduce the incidence of VAP and colistin use; the former decreased from 17.77 per 1000 VDs in 2014 to 1.13 per 1000 VDs in 2024. Moreover, baseline trends in VAP, VUR, and colistin use declined in period 1, and 3rd-generation cephalosporin use declined in period 2.

Invasive HFOV can be used either as an elective or rescue mode in neonates [19]. By assessing pulmonary function, HFOV minimizes ventilator-induced lung injury by using tidal volumes below the anatomical dead space [19] and reduced ventilator pressure. According to a meta-analysis, elective HFOV results in a reduction in the risk of BPD, death, and severe retinopathy of prematurity compared to conventional mechanical ventilation in preterm infants [20]. However, only one study investigated its utility in late preterm and term infants [21].

Previous studies have shown that the new NIV modes (both nHFOV and nSIPPV) in preterm infants reduce treatment failure and endotracheal ventilation as the primary mode [22] and lower the reintubation rates when used post-extubation [12,23,24] compared with nCPAP. In this study, they also reduced VAP incidence as a long-term outcome. Importantly, early or aggressive extubation may be difficult in routine practice unless full support for NIV is provided after extubation, especially in preterm infants. The VAP incidence density ratio decreased to 0.25 (four times from the reference) and 0.19 (five times from the reference) in periods 2 and 3, respectively, compared to period 1 (reference). nSIPPV may be superior to other NIV modes, reducing extubation failure (reintubation rate) [12] and improving ventilation (lower arterial PaCO2). Moreover, VAP incidence was low at the end of period 1; therefore, there was no significant change in period 2 (oral care) or period 3 (nSIPPV).

The gut-lung interaction may involve crosstalk between oral, intestinal, respiratory, and immune systems. Breast milk has the most protective and effective immunomodulatory activity owing to enrichment of immune-active factors. A previous meta-analysis reported that oral care with breast milk reduced VAP incidence (risk ratio = 0.41, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.23–0.75) and necrotizing enterocolitis (risk ratio = 0.54, 95% CI 0.30–0.95), while shortening invasive ventilation duration (mean difference = −0.45 days, 95% CI −0.73 to −0.18) and length of stay (mean difference = −5.74 days, 95% CI −10.39 to −1.10) in mechanically ventilated preterm infants [7]. Regular and meticulous oral hygiene is pivotal in preventing VAP in ventilated neonates.

Neonatal VAP incidence varies depending on the study design (retrospective vs. prospective) [13], resource setting (economic strata) [1], GA or birth weight (BW) category [3,25], and the sophistication of neonatal care [3]. Reported rates range from 1.4 to 7 episodes per 1000 VDs in developed countries and 16.1–89 episodes per 1000 VDs in developing countries [1]. The INICC reported pooled mean VAP rates of 9.5 and 7.5 episodes per 1000 VDs for 2007–2012 and 2012–2017, respectively, whereas VUR increased from 0.15 to 0.23 [3]. The National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) for level III NICUs during 2013 reported pooled means of neonatal VAP rate and VUR of 0.81 episodes per 1000 VDs and 0.15, respectively [25]. In a U.S. NICU, VAP incidence in extremely preterm (GA < 28 weeks) infants during 2000–2001 and very preterm (GA < 32 weeks) infants during 2015–2021 [26] were 6.5 and 7.8 per 1000 VDs, respectively. In a Thai NICU, VAP incidences in neonates with BW ≤ 750, 751–1000, and 1001–1500 g during 2014–2016 were 6.1, 2.0, and 0 per 1000 VDs, respectively [27]. Here, in 2014, VAP incidence was 17.77 per 1000 VDs, two times the INICC rate from 2012 to 2017. After tailoring the implementation interventions, VAP incidence was 1.13 per 1000 VDs, similar to the NHSN rate in 2013.

The AUR trends in this study declined during periods 1, 2, and 3 (31.5%, 32.8%, and 23.4%, respectively). The AUR varies by data year, level of neonatal care, and MDR area. In U.S. NICUs, the AUR declined from 37.4% to 19.2% (2009–2021; Premier Healthcare Database) [28], displaying values of 55.9% (2011–2012; level IV NICU, Children’s Medical Center of Dallas) [29], 34.2% (2011–2012; level IIIC NICU, Parkland Memorial Hospital) [30], 24.5% to 21.9% (2013–2016; 127 NICUs across California) [31,32], and 22.0% to 13.2% (2017–2022; Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center) [33]. In Chinese NICUs, the AUR was 44.1% (2015–2018; 25 tertiary NICUs) [34] and 79.1% to 46.6% (2017–2019 to 2019–2021; level IV NICU) [35].

Antimicrobial use also declined in this study, the percentages of neonates who received total antimicrobials in periods 1, 2, and 3 were 67.5%, 57.1%, and 44.7%, respectively. In previous studies, the percentages were 23.3% (656/2813; 51 U.S. NICUs, 2017) [36], 51.6% (208/403; 8 NICUs in India, 2016–2017) [37], 88.4% (21,736/24,597; 25 NICUs in China, 2015–2018) [34], and 96.2% (483/502; Iran, 2023–2024) [38].

Antimicrobial stewardship in the neonatal period is a formidable challenge in NICUs caring for critically vulnerable and fragile neonates. Empirical antimicrobial therapy in a neonate often begins when a baby develops clinical signs of “not looking well.” Prolonged antimicrobial use may be prescribed owing to the immunocompromised host and a high device utilization ratio. High AUR drives high MDR colonization pressure in the NICU environment. MDR organisms, including CRAB, are common pathogens in neonatal VAP [13,14]. Specifically, empirical treatment of VAP in high-CRAB settings often involves combination antimicrobials and colistin (intravenous or aerosolized routes) [39,40]. CRAB may be susceptible only to colistin. Nevertheless, colistin therapy is off-label in the neonatal period and requires monitoring for hypomagnesemia and acute kidney injury [41,42,43].

The strength of this study lies in its longitudinal assessment of new interventions implemented in a NICU with an initially high VAP incidence. New modes of NIV, including nHFOV and n(S)IPPV, significantly lowered reintubation rates than compared with nCPAP during short-term follow-up. Moreover, these new NIV modes represent elements of ventilatory care that reduces neonatal VAP. However, results should be interpreted with caution owing to some limitations. First, this study employed a quasi-experimental design, applying bundled IPC measures over an extended period. Long-term secular trends in VAP outcomes were analyzed across 11 years. A limitation of this approach is that the causation derived from multiple simultaneous interventions within each period, and the specific therapeutic outcome of each individual bundle element, could not be assessed independently. To mitigate bias and confounding variables (e.g., GA, BW, and mode of delivery), randomized controlled trials are warranted. Second, VAP incidence varies worldwide; therefore, VAP outcomes of ventilatory bundle care depend on VAP incidence in each NICU. Wherever a NICU has a high VAP, VUR, or AUR incidence, the new multimodal implementation described in this study may be an IPC strategy. Third, the absence of a standardized, neonate-specific VAP definition [44]. The study mitigated this by consistently applying the NHSN guidelines developed for infants less than one year of age across all time points. This adherence to a stable definition throughout the study period ensured consistency in case identification. Fourth, the absence of a standardized, protocol-driven approach to NIV weaning, the process relied on local guidelines and the clinical judgment of the attending staff. Furthermore, the role of staffing or environmental pressures on patient outcomes could not be adequately assessed, thus restricting the scope of our findings and reproducibility. Finally, the precise data regarding the duration of respiratory support modalities (nHFOV or nSIPPV) for individual neonates were not available for analysis. The absence of documentation on compliance with each IPC bundle element further restricts the interpretation of our findings. Furthermore, although antimicrobial utilization trends were documented, this analysis was limited by its inability to disentangle the effects of concurrent changes (e.g., evolving clinical practices, admission patterns, stewardship policies, or COVID-19 pandemic) that may have independently influenced prescribing behaviors.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Setting and Period

This study was conducted in the NICU of the Songklanagarind Hospital, a teaching hospital affiliated with the Prince of Songkla University in Thailand. The number of inborn neonates was 2500–3500 live births, with 400–550 inborn and outborn neonates admitted to the level IV NICU annually. The study protocol was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Prince of Songkla University (Approval No.: 68–532–1–1). The study domain comprised all neonates admitted to the NICU of Songklanagarind Hospital between 1 January 2014, and 31 December 2024.

This quasi-experimental study divided care practice into three periods following each specific IPC strategy: period 1, a 4-year multimodal strategies period (2014–2017); period 2, a 3-year oral care period (2018–2020); and period 3, a 4-year nSIPPV period (2021–2024).

4.2. General and Specific IPC Strategies

General IPC elements were similar over the three study periods, and all healthcare personnel and visitors strictly adhered to the hand hygiene protocol before and after neonatal care. The patient-to-nurse ratio was 1–2:1 throughout the study. The head elevation of the bed ranged from 15° to 30°. Healthcare workers were encouraged to participate in targeted training programs and continuous professional development initiatives to prevent VAP. Intravenous aminophylline and oral caffeine were administered, when full enteral feeding has been administered to preterm infants with a BW less than 1250 g [45,46,47] or intubated neonates. We provided comprehensive training and education on VAP prevention techniques to staff and visitors.

Before period 1, routine neonatal care pre-interventions included: (1) reused ventilator circuits, with heated humidifiers and a heated wire in the inspiratory limb only, and a water trap in the expiratory limb, cleaned by pasteurization; (2) 0.5% sodium hypochlorite (10% sodium hypochlorite diluted with tap water at 1:19, equal to 5000 ppm) to clean the NICU environment (walls and rails) and the vacuum-suction base; (3) inline suctioning for intubated neonates, with NIV after extubation such as nCPAP or biphasic CPAP; and (4) daily oral hygiene was not standard practice.

During period 1, the multimodal intervention included: (1) use of HMEs with dual heated wires and the permeable microcell technique for all ventilated neonates (RT 265, Evaqua2 Infant Breathing Circuits, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, Auckland, New Zealand); (2) use of 0.05% sodium hypochlorite (10% sodium hypochlorite diluted with tap water at 1:199, equal to 500 ppm) for 30 s cleaning of the neonatal environment (inside and outside the incubator and the radiant warmer), followed by clean, dry linens, and 0.5% sodium hypochlorite to clean the NICU environment [48]; (3) elective HFOV initiated as the primary mode after intubation, and nHFOV (medinCNO, medin Medical Innovations GmbH, Olching, Germany) used as the new NIV mode for post-extubation support; and (4) oral care with sterile water every 3–4 h when possible.

During period 2 (oral immune therapy), very low birth weight (BW < 1500 g) infants were randomized to oral care with maternal milk or sterile water. Bedside nurses administered 0.1 mL of maternal milk (fresh or refrigerated) or sterile water into each buccal pouch every 3 h until oral feeding (breastfeeding or bottle feeding) began [5]. After the trial, oral care with maternal milk was practiced routinely.

During Period 3, post-extubation neonates were randomized into NIV between nHFOV and nSIPPV [49]. During this period, the nHFOV and nSIPPV modes were provided by an SLE6000 infant ventilator (SLE, Croydon, United Kingdom), a Dräger Babylog VN500 (Dräger, Lübeck, Germany), a Fabian HFO (Acutronic, Bubikon, Switzerland), and a Maquet Servo N (Getinge, Göteborg, Sweden). Moreover, other NIV techniques, including nCPAP, biphasic CPAP, and high- or low-flow cannulas, were used for post-extubation or weaning from nHFOV or nSIPPV.

4.3. Definitions

Since 2014, VAP diagnosis has followed the NHSN guidelines for infants aged less than 1 year old [44]. Small, appropriate, and large for GA were defined as BW below the 10th, 10th–90th, and above the 90th percentiles for GA. Surfactant therapy was administered to preterm neonates diagnosed with moderate or severe respiratory distress syndrome who required a fraction of inspired oxygen exceeding 0.3 while on NIV or mechanical ventilation via endotracheal intubation. Moderate or severe BPD was defined as oxygen supplementation for at least 28 days with continued need for supplemental oxygen and/or positive pressure respiratory support at 36 weeks of postmenstrual age or at discharge, whichever came first [50].

The incidence density of VAP was calculated by dividing the number of new VAP events by the total number of VDs. Total antimicrobial use was defined as the total number of neonates exposed to one or more parenteral antimicrobial agents per 100 NICU-admitted neonates and was expressed as a percentage. The AUR is the total number of patient-days in which infants were exposed to one or more parenteral antimicrobial agents per 100 patient-days in the reporting NICU, expressed as a percentage [31,33,34]. The 3rd-generation cephalosporins comprise cefotaxime, ceftazidime, and cefoperazone plus sulbactam. Carbapenems included imipenem and meropenem. VUR is the ratio of VDs per patient-day.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

The R program (version 4.5.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria [51]), encompassing EpiCalc packages (version 4.1.0.1; Epidemiology Unit, Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai, Thailand [52]), was used to analyze the data. Categorical variables are presented and compared using percentages and χ2 test. Parametric and non-parametric continuous variables were presented as mean and median and compared using the analysis of variance F-test and the Kruskal–Wallis test, respectively.

A Poisson regression model was employed to analyze VAP incidence rates across years, with ventilator-days serving as the offset variable, comparing each year’s rate to the baseline year of 2014 (Table 2). A time-series model was developed to analyze the trends of the variables over 11 years. We conducted trend analysis using an interrupted time-series design with segmented regression, grounded in generalized linear model principles, to assess the overall trajectory of outcome changes over the study period (Table 3). All p-values were 2-tailed, with p < 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

5. Conclusions

Tailoring implementation interventions using a multimodal approach to prevent VAP in the NICU is crucial and requires strict IPC, including rigorous hand hygiene, environmental disinfection, careful ventilator device use, aggressive extubation with new NIV modes, and oral care with maternal milk, especially when VAP incidence is high. Further randomized trials for each element are warranted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M., A.T., P.C., P.P., M.P. and S.D.; methodology, A.T., S.K. and A.A.; formal analysis, G.M., A.T., P.C., P.P., M.P. and S.D.; data curation, A.T., S.K. and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, G.M., A.T., P.C., P.P., M.P. and S.D.; writing—review and editing, G.M., A.T., P.C., P.P., M.P., S.D., S.K. and A.A.; visualization, G.M. and A.T.; supervision, A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University (REC. 68–532–1–1; date of approval: 21 November 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was not required owing to the retrospective study design.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUR | Antimicrobial use rate |

| BPD | Bronchopulmonary dysplasia |

| BW | Birth weight |

| CPAP | Continuous positive airway pressure |

| CRAB | Carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii |

| GA | Gestational age |

| HFOV | High-frequency oscillatory ventilation |

| HME | Heat and moisture exchanger |

| INICC | International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium |

| IPC | Infection prevention and control |

| IPPV | Intermittent positive pressure ventilation |

| nCPAP | Nasal continuous positive airway pressure |

| nHFOV | Nasal high frequency oscillatory ventilation |

| NICU | Neonatal intensive care unit |

| NHSN | National Healthcare Safety Network |

| NIV | Noninvasive ventilation |

| nSIPPV | Nasal synchronized intermittent positive pressure ventilation |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| VAP | Ventilator-associated pneumonia |

| VD | Ventilator days |

| VUR | Ventilator utilization ratio |

References

- Rangelova, V.; Kevorkyan, A.; Raycheva, R.; Krasteva, M. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in the neonatal intensive care unit-incidence and strategies for prevention. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, V.D.; Bijie, H.; Maki, D.G.; Mehta, Y.; Apisarnthanarak, A.; Medeiros, E.A.; Leblebicioglu, H.; Fisher, D.; Alvarez-Moreno, C.; Khader, I.A.; et al. International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) report, data summary of 36 countries, for 2004–2009. Am. J. Infect. Control 2012, 40, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal, V.D.; Bat-Erdene, I.; Gupta, D.; Belkebir, S.; Rajhans, P.; Zand, F.; Myatra, S.N.; Afeef, M.; Tanzi, V.L.; Muralidharan, S.; et al. International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) report, data summary of 45 countries for 2012–2017: Device-associated module. Am. J. Infect. Control 2020, 48, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, M.; Liu, C.; Mei, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Song, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xin, C. Intervention effect of oropharyngeal administration of colostrum in preterm infants: A meta-analysis. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 895375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatrimontrichai, A.; Surachat, K.; Singkhamanan, K.; Thongsuksai, P. Long duration of oral care using mother’s own milk influences oral microbiota and clinical outcomes in very-low-birthweight infants: Randomized controlled trial. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2023, 42, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alriyami, A.; Kiger, J.R.; Hooven, T.A. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in the neonatal intensive care unit. Neoreviews 2022, 23, e448–e461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Lin, L.; Peng, Y.; Chen, L.; Lin, Y. Effect of breast milk oral care on mechanically ventilated preterm infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 899193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalish, W.; Sant’Anna, G.M. Optimal timing of extubation in preterm infants. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023, 28, 101489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, D.; Centorrino, R. Nasal high-frequency ventilation. Clin. Perinatol. 2021, 48, 761–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ognean, M.L.; Bivoleanu, A.; Cucerea, M.; Galiș, R.; Roșca, I.; Surdu, M.; Stoicescu, S.M.; Ramanathan, R. Nasal high-frequency oscillatory ventilation use in Romanian neonatal intensive care units-the results of a recent survey. Children 2024, 11, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, C.; Gizzi, C. Synchronized nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation. Clin. Perinatol. 2021, 48, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, V.D.; Rüegger, C.M. Optimising success of neonatal extubation: Respiratory support. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023, 28, 101491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thatrimontrichai, A.; Rujeerapaiboon, N.; Janjindamai, W.; Dissaneevate, S.; Maneenil, G.; Kritsaneepaiboon, S.; Tanaanantarak, P. Outcomes and risk factors of ventilator-associated pneumonia in neonates. World J. Pediatr. 2017, 13, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatrimontrichai, A.; Techato, C.; Dissaneevate, S.; Janjindamai, W.; Maneenil, G.; Kritsaneepaiboon, S.; Tanaanantarak, P. Risk factors and outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia in the neonate: A case-case-control study. J. Infect. Chemother. 2016, 22, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaruno, S.; Jaroenmark, T.; Wani, A.; Dangchuen, T.; Binyala, W.; Morapan, N.; Vattanavanit, V. Epidemiology of sepsis and septic shock in the medical intensive care unit after implementing the national early warning score for sepsis detection. J. Health Sci. Med. Res. 2025, 43, 20251181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakwan, N.; Chokephaibulkit, K.; Imberti, R. The use of colistin for the treatment of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections in neonates and infants: A review of the literature. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2019, 38, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakwan, N.; Usaha, S.; Chokephaibulkit, K.; Villani, P.; Regazzi, M.; Imberti, R. Pharmacokinetics of colistin following a single dose of intravenous colistimethate sodium in critically ill neonates. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2016, 35, 1211–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakwan, N.; Chokephaibulkit, K. Can intravenous colistin effectively treat ventilator-associated pneumonia in the pediatric and neonatal patients? Eur. J. Pediatr. 2011, 170, 1355–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, B.W.; Klotz, D.; Hentschel, R.; Thome, U.H.; van Kaam, A.H. High-frequency ventilation in preterm infants and neonates. Pediatr. Res. 2023, 93, 1810–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools, F.; Offringa, M.; Askie, L.M. Elective high frequency oscillatory ventilation versus conventional ventilation for acute pulmonary dysfunction in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD000104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson-Smart, D.J.; De Paoli, A.G.; Clark, R.H.; Bhuta, T. High frequency oscillatory ventilation versus conventional ventilation for infants with severe pulmonary dysfunction born at or near term. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 2009, CD002974. [Google Scholar]

- Mukerji, A.; Shah, P.S.; Kadam, M.; Borhan, S.; Razak, A. Non-invasive respiratory support in preterm infants as primary mode: A network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 7, CD014895. [Google Scholar]

- Razak, A.; Shah, P.S.; Kadam, M.; Borhan, S.; Mukerji, A. Postextubation use of non-invasive respiratory support in preterm infants: A network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 7, CD014509. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, R.; Saha, B.; Sk, M.H.; Sahoo, J.P.; Gupta, B.K.; Shaw, S.C. Noninvasive high-frequency oscillation ventilation as post- extubation respiratory support in neonates: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudeck, M.A.; Edwards, J.R.; Allen-Bridson, K.; Gross, C.; Malpiedi, P.J.; Peterson, K.D.; Pollock, D.A.; Weiner, L.M.; Sievert, D.M. National Healthcare Safety Network report, data summary for 2013, device-associated module. Am. J. Infect. Control 2015, 43, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Cayabyab, R.; Cielo, M.; Ramanathan, R. Incidence, risk factors, short-term outcomes, and microbiome of ventilator-associated pneumonia in very-low-birth-weight infants: Experience at a single level iii neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2024, 43, 1083–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thatrimontrichai, A.; Janjindamai, W.; Dissaneevate, S.; Maneenil, G.; Kritsaneepaiboon, S. Risk factors and outcomes of ventilator-associated pneumonia from a neonatal intensive care unit, Thailand. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2019, 50, 537–545. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery, D.D.; Zevallos Barboza, A.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Wade, K.C.; Gerber, J.S.; Shu, D.; Puopolo, K.M. Antibiotic use among infants admitted to neonatal intensive care units. JAMA Pediatr. 2023, 177, 1354–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipp, K.D.; Chiang, T.; Karasick, S.; Quick, K.; Nguyen, S.T.; Cantey, J.B. Antibiotic stewardship challenges in a referral neonatal intensive care unit. Am. J. Perinatol. 2016, 33, 518–524. [Google Scholar]

- Cantey, J.B.; Wozniak, P.S.; Sánchez, P.J. Prospective surveillance of antibiotic use in the neonatal intensive care unit: Results from the SCOUT study. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2015, 34, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Dimand, R.J.; Lee, H.C.; Duenas, G.V.; Bennett, M.V.; Gould, J.B. Neonatal intensive care unit antibiotic use. Pediatrics 2015, 135, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Profit, J.; Lee, H.C.; Dueñas, G.; Bennett, M.V.; Parucha, J.; Jocson, M.A.L.; Gould, J.B. Variations in neonatal antibiotic use. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20180115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.P.; Wilkinson, S.; Kamran, S. Decreasing antibiotic use in a community neonatal intensive care unit: A quality improvement initiative. Am. J. Perinatol. 2024, 41, e2767–e2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yan, W.; Li, S.; Han, J.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, Y.; Lee, S.K.; Cao, Y. Antibiotic use in neonatal intensive care units in China: A multicenter cohort study. J. Pediatr. 2021, 239, 136–142.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Yang, S.; Han, J.; Nie, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Pei, J.; et al. Reduction of antibiotic use and multi-drug resistance bacteria infection in neonates after improvement of antibiotics use strategy in a level 4 neonatal intensive care unit in southern China. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 42, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, H.J.J.; Dantuluri, K.L.; Thurm, C.; Griffith, H.; Grijalva, C.G.; Banerjee, R.; Howard, L.M. Variation in antibiotic use among neonatal intensive care units in the United States. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2022, 43, 1945–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandra, S.; Alvarez-Uria, G.; Murki, S.; Singh, S.K.; Kanithi, R.; Jinka, D.R.; Chikkappa, A.K.; Subramanian, S.; Sharma, A.; Dharmapalan, D.; et al. Point prevalence surveys of antimicrobial use among eight neonatal intensive care units in India: 2016. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 71, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hematian, F.; Aletayeb, S.M.H.; Dehdashtian, M.; Aramesh, M.R.; Malakian, A.; Aletayeb, M.S. Frequency and types of antibiotic usage in a referral neonatal intensive care unit, based on the world health organization classification (AwaRe). BMC Pediatr. 2025, 25, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, K.; Salat, M.S.; Ambreen, G.; Mughal, A.; Idrees, S.; Sohail, M.; Iqbal, J. Intravenous vs intravenous plus aerosolized colistin for treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia—A matched case-control study in neonates. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2020, 19, 1641–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.H.; Tsai, C.M.; Wu, T.H.; Wu, H.Y.; Chung, M.Y.; Chen, C.C.; Huang, Y.C.; Liu, S.F.; Liao, D.L.; Niu, C.K.; et al. Colistin inhalation monotherapy for ventilator-associated pneumonia of Acinetobacter baumannii in prematurity. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2014, 49, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, T.B.; Sürmeli Onay, Ö.; Aydemir, Ö.; Tekin, A.N. Ten-year single center experience with colistin therapy in NICU. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2024, 43, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alan, S.; Yildiz, D.; Erdeve, O.; Cakir, U.; Kahvecioglu, D.; Okulu, E.; Ates, C.; Atasay, B.; Arsan, S. Efficacy and safety of intravenous colistin in preterm infants with nosocomial sepsis caused by Acinetobacter baumannii. Am. J. Perinatol. 2014, 31, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seanglaw, D.; Morasert, T. Development of a prediction model for acute kidney injury after colistin treatment for multidrug-resistant acinetobacter baumanii ventilator-associated pneumonia: A pilot study. J. Health Sci. Med. Res. 2023, 41, e2022891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC and NHSN. Pneumonia (Ventilator-Associated [VAP] and Non-Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia [PNEU]) Event. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/6pscvapcurrent.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Schmidt, B.; Roberts, R.S.; Davis, P.; Doyle, L.W.; Barrington, K.J.; Ohlsson, A.; Solimano, A.; Tin, W. Caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2112–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, B.; Roberts, R.S.; Davis, P.; Doyle, L.W.; Barrington, K.J.; Ohlsson, A.; Solimano, A.; Tin, W. Long-term effects of caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 1893–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mürner-Lavanchy, I.M.; Doyle, L.W.; Schmidt, B.; Roberts, R.S.; Asztalos, E.V.; Costantini, L.; Davis, P.G.; Dewey, D.; D’Ilario, J.; Grunau, R.E.; et al. Neurobehavioral outcomes 11 years after neonatal caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20174047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thatrimontrichai, A.; Pannaraj, P.S.; Janjindamai, W.; Dissaneevate, S.; Maneenil, G.; Apisarnthanarak, A. Intervention to reduce carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a neonatal intensive care unit. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020, 41, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phatigomet, M.; Thatrimontrichai, A.; Maneenil, G.; Dissaneevate, S.; Janjindamai, W. Reintubation rate between nasal high-frequency oscillatory ventilation versus synchronized nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation in neonates: A parallel randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Perinatol. 2024, 41, 1504–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobe, A.H.; Bancalari, E. Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 163, 1723–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R-4.5.1 for Windows. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Chongsuvivatwong, V. Epicalc: Epidemiological Calculator. Available online: https://medipe.psu.ac.th/epicalc/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.