Cross-Sectional Survey on the Current Role of Clinical Pharmacists among Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in Catalonia: Much Ado about Nothing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design, Setting, and Participants

4.2. Survey Design

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paño-Pardo, J.R.; Padilla, B.; Romero-Gómez, M.P.; Moreno-Ramos, F.; Rico-Nieto, A.; Mora-Rillo, M.; Horcajada, J.P.; Ramón Arribas, J.; Rodríguez-Baño, J. Actividades de monitorización y mejora del uso de antibióticos en hospitales españoles: Resultado de una encuesta nacional. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2011, 29, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuts, E.C.; Hulscher, M.E.J.L.; Mouton, J.W.; Verduin, C.M.; Stuart, J.W.T.C.; Overdiek, H.W.P.M.; van der Linden, P.D.; Natsch, S.; Hertogh, C.M.P.M.; Wolfs, T.F.W.; et al. Current evidence on hospital antimicrobial stewardship objectives: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Paño-Pardo, J.R.; Alvarez-Rocha, L.; Asensio, Á.; Calbo, E.; Cercenado, E.; Cisneros, J.M.; Cobo, J.; Delgado, O.; Garnacho-Montero, J.; et al. Programas de optimización de uso de antimicrobianos (PROA) en hospitales españoles: Documento de consenso GEIH-SEIMC, SEFH y SEMPSPH. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2012, 30, 22.e1–22.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in Health-Care Facilities in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. A Practical Toolkit; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1, ISBN 9789241515481. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs; US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Karanika, S.; Paudel, S.; Grigoras, C.; Kalbasi, A.; Mylonakis, E. Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical and economic outcomes from the implementation of hospital-based antimicrobial stewardship programs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 4840–4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Lerma, F.; Grau, S.; Echeverría-Esnal, D.; Martínez-Alonso, M.; Pilar Gracia-Arnillas, M.; Pablo Horcajada, J.; Ramón Masclansa, J. A before-and-after study of the effectiveness of an antimicrobial stewardship program in critical care. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01825-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.J.; Chen, S.J.; Hu, Y.W.; Liu, C.Y.; Wu, P.F.; Sun, S.M.; Lee, S.Y.; Chen, Y.Y.; Lee, C.Y.; Chan, Y.J.; et al. The impact of antimicrobial stewardship program designed to shorten antibiotics use on the incidence of resistant bacterial infections and mortality. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, E.L.; Kuti, J.L.; Bearden, D.T.; Gallagher, J.C. The Essential Role of Pharmacists in Antimicrobial Stewardship. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2016, 37, 753–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado Sánchez, O.; Palomo, J.B.; Sora Ortega, M.; Moranta Ribas, F. Uso prudente de antibióticos y propuestas de mejora desde la farmacia comunitaria y hospitalaria. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2010, 28, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHP ASHP Statement on the Pharmacist’s Role in Antimicrobial Stewardship and Infection Prevention and Control. Am. J. Health Pharm. 2010, 67, 575–577. [CrossRef]

- Dionne, B.; Wagner, J.L.; Chastain, D.B.; Rosenthal, M.; Mahoney, M.V.; Bland, C.M. Which pharmacists are performing antimicrobial stewardship: A national survey and a call for collaborative efforts. Antimicrob. Steward. Healthc. Epidemiol. 2022, 2, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.; Muñoz, C.; Aguilera, C.; Alonso, M.; Sacristán, S.; Castillo, R.; Justo, C. AEMPS Informe Anual PRAN. Junio 2019–Junio 2020; Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS): Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Pérez-Moreno, M.A.; Peñalva, G.; Garnacho-Montero, J.; Pinto, C.; Salcedo, I.; Fernández-Urrusuno, R.; Neth, O.; Gil-Navarro, M.V.; Pérez-Milena, A.; et al. Outcomes of the PIRASOA programme, an antimicrobial stewardship programme implemented in hospitals of the Public Health System of Andalusia, Spain: An ecologic study of time-trend analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, P.; Pulcini, C.; Levy Hara, G.; West, R.M.; Gould, I.M.; Harbarth, S.; Nathwani, D. An international cross-sectional survey of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 70, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallen, M.C.; Binda, F.; ten Oever, J.; Tebano, G.; Pulcini, C.; Murri, R.; Beovic, B.; Saje, A.; Prins, J.M.; Hulscher, M.E.J.L.; et al. Comparison of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in acute-care hospitals in four European countries: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2019, 54, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weier, N.; Tebano, G.; Thilly, N.; Demoré, B.; Pulcini, C.; Zaidi, S.T.R. Pharmacist participation in antimicrobial stewardship in Australian and French hospitals: A cross-sectional nationwide survey. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulcini, C.; Morel, C.M.; Tacconelli, E.; Beovic, B.; de With, K.; Goossens, H.; Harbarth, S.; Holmes, A.; Howard, P.; Morris, A.M.; et al. Human resources estimates and funding for antibiotic stewardship teams are urgently needed. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 785–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doernberg, S.B.; Abbo, L.M.; Burdette, S.D.; Fishman, N.O.; Goodman, E.L.; Kravitz, G.R.; Leggett, J.E.; Moehring, R.W.; Newland, J.G.; Robinson, P.A.; et al. Essential Resources and Strategies for Antibiotic Stewardship Programs in the Acute Care Setting. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 1168–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spellberg, B.; Bartlett, J.G.; Gilbert, D.N. How to pitch an antibiotic stewardship program to the hospital C-suite. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2016, 3, ofw210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, M.H.; Nesbitt, W.J.; Nelson, G.E. Antimicrobial stewardship staffing: How much is enough? Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020, 41, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda, F.; Tebano, G.; Kallen, M.C.; ten Oever, J.; Hulscher, M.E.; Schouten, J.A.; Pulcini, C. Nationwide survey of hospital antibiotic stewardship programs in France. Med. Mal. Infect. 2020, 50, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuper, K.M.; Hamilton, K.W. Collaborative Antimicrobial Stewardship: Working with Information Technology. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 34, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckel, W.R.; Stenehjem, E.A.; Hersh, A.L.; Hyun, D.Y.; Zetts, R.M. Harnessing the Power of Health Systems and Networks for Antimicrobial Stewardship. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 2038–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badia, J.M.; Batlle, M.; Juvany, M.; Ruiz-De León, P.; Sagalés, M.; Pulido, M.A.; Molist, G.; Cuquet, J. Surgeon-led 7-vincut antibiotic stewardship intervention decreases duration of treatment and carbapenem use in a general surgery service. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, B.J.; Nisenbaum, R.; Brown, K.A.; Chan, A.; Downing, M. Antibiotics: Easier to start than to stop? Predictors of antimicrobial stewardship recommendation acceptance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 1638–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VINCat. Programa de Vigilància de les Infeccions Relacionades amb L’atenció Sanitària de Catalunya (VINCat): Manual VINCat, 5th ed.; Servei Català de la Salut: Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Total | Group 1 (≥500 Beds) | Group 2 (200–499 Beds) | Group 3 (<200 Beds) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of hospitals included | 49 | 7 | 16 | 26 | |

| Number of beds | 189.0 (131.0–365.0) | 723.0 (650–763) | 309.0 (212.5–395.0) | 134.0 (100.0–159.3) | <0.001 |

| Teaching hospital | 21 (42.9) | 6 (85.7) | 9 (56.3) | 6 (23.1) | 0.005 |

| Private hospital | 8 (16.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (12.5) | 6 (23.1) | 0.301 |

| Intensive care unit Number of beds | 32 (65.3) 12.0 (8.0–36.5) | 7 (100.0) 90.0 (38–117) | 15 (93.8) 12.0 (10–20) | 10 (38.5) 8.0 (5.5–9.3) | <0.001 <0.001 |

| Solid organ or bone marrow transplantation units | 9 (18.4) | 5 (71.4) | 1 (6.3) | 3 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| Onco-haematology units | 35 (71.4) | 6 (85.7) | 12 (75.0) | 17 (65.4) | 0.531 |

| Paediatric units | 33 (67.3) | 4 (57.1) | 13 (81.3) | 16 (61.5) | 0.344 |

| Others (cystic fibrosis, lung transplant) | 6 (12.2) | 3 (42.9) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (3.8) | 0.020 |

| ASP characteristics | |||||

| Number of years since ASP establishment | 5.0 (4.0–8.0) | 5.0 (3.0–7.0) | 6.0 (4.3–10.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.5) | 0.118 |

| Number of years since clinical pharmacists were incorporated into ASP | 5.0 (4.0–8.0) | 5.0 (3.0–7.0) | 6.0 (4.0–10.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.5) | 0.364 |

| Number of pharmacists in ASP | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 0.122 |

| Number of hours dedicated by clinical pharmacists to ASP per week | 5.0 (2.0–10.0) | 10.0 (2.0–20) | 7.0 (5.3–10.0) | 3.0 (1.0–7.0) | 0.012 |

| Number of hours dedicated by clinical pharmacists to ASP per week/100 acute care beds | 2.3 (1.3–4.9) | 1.5 (0.3–2.5) | 2.6 (1.7–4.5) | 2.1 (1.2–6.3) | 0.130 |

| Full time equivalents | 0.15 (0.1–0.3) | 0.28 (0.1–0.5) | 0.21 (0.2–0.3) | 0.1 (0.04–0.2) | 0.003 |

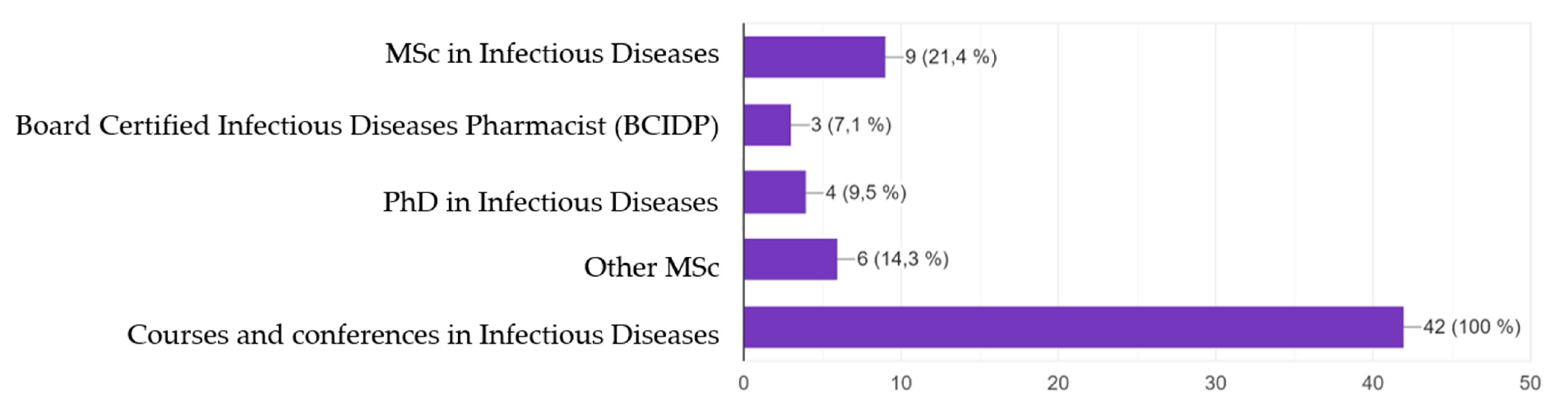

| ID Training MSc, PhD, BCIDP Courses and conferences | 42 14 (28.6) 28 (57.1) | 7 (100.0) 4 (57.1) 3 (42.9) | 15 (93.8) 6 (40.0) 9 (60.0) | 20/25 (80.0) 4 (20.0) 16 (80.0) | 0.240 0.158 0.254 |

| ASP computer tools | |||||

| Computer tools to perform ASP | 23 (46.9) | 4 (57.1) | 9 (56.3) | 10 (38.5) | 0.449 |

| Computer tool includes a specific section of recommendation for intravenous-to-oral switch | 5 (10.2) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (11.5) | 0.108 |

| Computer tool includes the need to prescribe the length of treatment at the time of prescription | 14 (28.6) | 3 (42.9) | 5 (31.3) | 6 (23.1) | 0.565 |

| Computer tool includes clinical decision support systems | 2 (4.1) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 0.206 |

| Computer tool includes time outs at 48–72 h of antimicrobial prescribing | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | 0.637 |

| Computer tool includes the need to include the diagnosis at the time of prescription | 7 (14.3) | 2 (28.6) | 5 (31.3) | 0 (0) | 0.010 |

| Computer tool includes defined daily doses automatic calculation | 8 (16.3) | 3 (42.9) | 3 (18.8) | 2 (7.7) | 0.078 |

| Computer tool includes days of treatment automatic calculation | 8 (16.3) | 2 (28.6) | 4 (25.0) | 2 (8.0) | 0.239 |

| Total (n = 48) | Group 1 (n = 7) | Group 2 (n = 16) | Group 3 * (n = 25) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASP activities | |||||

| Number of annual meetings | 6.0 (5.0–8.0) | 6.0 (5.0–12.0) | 12.0 (6.0–40.0) | 4.0 (4.0–31.5) | 0.088 |

| Revision of restricted antimicrobials | 42 (87.5) | 5 (71.4) | 16 (100.0) | 21 (84.0) | 0.121 |

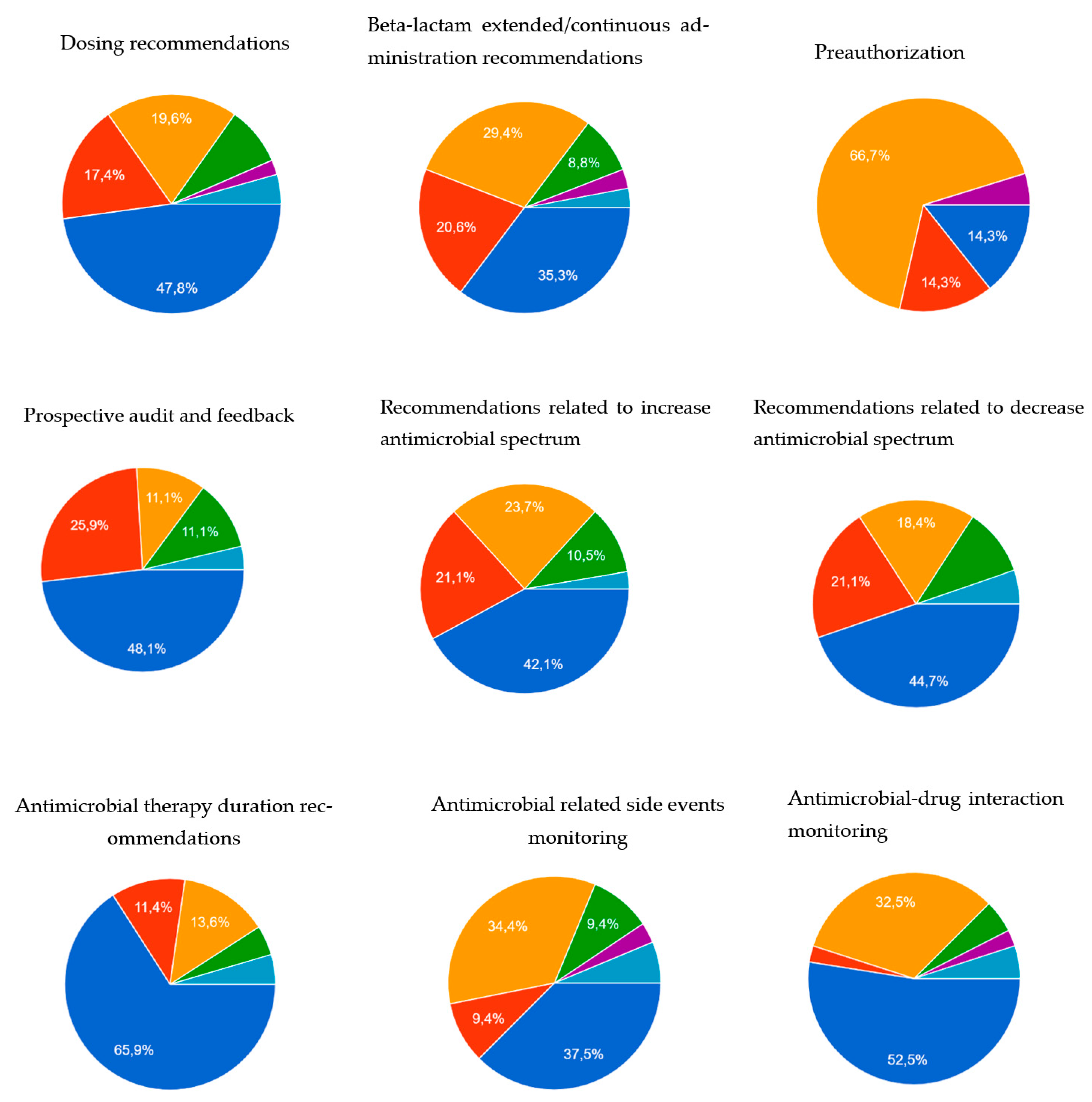

| Dosing recommendations | 46 (95.9) | 7 (100.0) | 16 (100.0) | 23 (92.0) | 0.383 |

| Beta-lactam extended/continuous administration recommendations | 34 (70.8) | 4 (57.1) | 14 (87.5) | 16 (64.0) | 0.187 |

| Didactic education | 26 (55.3) | 5 (71.4) | 10/15 (66.7) | 11 (44.0) | 0.245 |

| Preauthorization | 21 (43.8) | 3 (42.9) | 10 (62.5) | 8 (32.0) | 0.158 |

| Prospective audit and feedback | 28 (58.3) | 4 (57.1) | 13 (81.3) | 11 (44.0) | 0.062 |

| Antimicrobial spectrum-related recommendations | 38 (80.9) | 6 (85.7) | 14 (87.5) | 18/24 (75.0) | 0.579 |

| Antimicrobial therapy duration recommendations | 44 (91.7) | 5 (71.4) | 16 (100) | 23 (92.0) | 0.074 |

| Antimicrobial-related side events monitoring | 32 (68.1) | 5 (71.4) | 12 (75.0) | 15 (62.5) | 0.693 |

| Antimicrobial–drug interaction monitoring | 41 (85.4) | 7 (100.0) | 15 (93.8) | 19 (76.0) | 0.145 |

| Antimicrobial desensitisation Number of desensitisations | 12 (25.0) 5.0 (4.5–5.0) | 2 (28.6) 24.5 (0–49.0) | 6 (37.5) 4.0 (1.0–5.0) | 4 (16.0) 1.5 (1.0–15.5) | 0.292 0.262 |

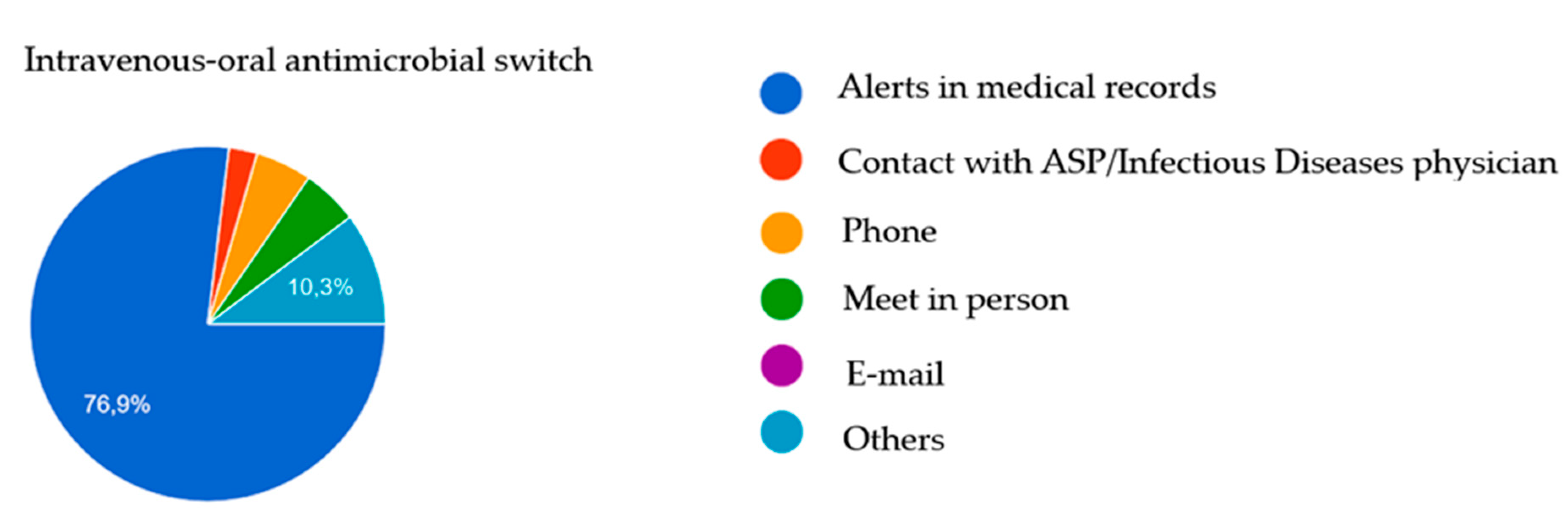

| Intravenous-to-oral antimicrobial switch | 39 (81.3) | 6 (85.7) | 14 (87.5) | 19 (76.0) | 0.621 |

| Antimicrobial guidelines development | 47 (97.9) | 7 (100.0) | 16 (100.0) | 24 (96.0) | 0.625 |

| Recommendations to perform cultures or swabs | 16 (33.3) | 1 (14.3) | 9 (56.3) | 6 (24.0) | 0.052 |

| Investigation Number of hours in a month | 12 (25.0) 4.0 (5.0–27.5) | 4 (57.1) 4.0 (2.5–31.0) | 5 (31.3) 5.0 (3.0–30.0) | 3 (12.0) 2.0 (0–2.0) | 0.040 0.381 |

| Teaching | 20 (41.7) | 5 (71.4) | 10 (62.5) | 5 (20.0) | 0.006 |

| Therapeutic drug monitoring Recommendations are made by ASP pharmacists | 34 (70.8) 18 (52.9) | 7 (100.0) 2 (28.6) | 13 (81.3) 10 (76.9) | 14 (56.0) 6 (42.9) | 0.041 0.073 |

| ≥15% of Time (n = 26) | <15% of Time (n = 22) * | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of hospital | 0.005 | ||

| Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 | 5 (19.2) 13 (50.0) 8 (30.8) | 2 (9.1) 3 (13.6) 17 (77.3) | |

| Number of annual meetings | 11.0 (4.8–40.0) | 5.0 (4.0–12.0) | 0.124 |

| Revision of restricted antimicrobials | 26 (100.0) | 16 (72.7) | 0.006 |

| Dosing recommendations | 26 (100.0) | 20 (90.9) | 0.205 |

| Beta-lactam extended/continuous administration recommendations | 24 (92.3) | 10 (45.5) | <0.001 |

| Didactic education | 19/25 (76.0) | 7 (31.8) | 0.003 |

| Preauthorization | 14 (53.8) | 7 (31.8) | 0.153 |

| Prospective audit and feedback | 21 (80.8) | 7 (31.8) | 0.001 |

| Antimicrobial spectrum related recommendations | 24/25 (96.0) | 14 (63.6) | 0.008 |

| Antimicrobial therapy duration recommendations | 26 (100.0) | 18 (81.8) | 0.038 |

| Antimicrobial related side events monitoring | 22 (84.6) | 10/21 (47.6) | 0.011 |

| Antimicrobial–drug interaction monitoring | 24 (92.3) | 17 (77.3) | 0.223 |

| Antimicrobial desensitisation Number of desensitisations | 7 (26.9) 4.0 (1.5–5.0) | 5 (22.7) 1.0 (1.0–34.5) | 1.000 0.841 |

| Intravenous-to-oral antimicrobial switch | 25 (96.2) | 14 (63.6) | 0.007 |

| Antimicrobial guidelines development | 26 (100.0) | 21 (95.5) | 0.458 |

| Recommendations to perform cultures or swabs | 11 (42.3) | 5 (22.7) | 0.221 |

| Investigation Number of hours in a month | 10 (38.5) 4.5 (3.0–17.5) | 2 (9.1) 1.0 (0–1.0) | 0.023 0.030 |

| Teaching | 16 (61.5) | 4 (18.2) | 0.003 |

| Therapeutic drug monitoring Recommendations are made by ASP pharmacists | 21 (80.8) 13 (61.9) | 13 (59.1) 5 (38.5) | 0.122 0.291 |

| MSc, BCIDP, PhD (n = 14) | Courses and Conferences (n = 28) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of hospital | 0.158 | ||

| Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 | 4 (28.6) 6 (42.9) 4 (28.6) | 3 (10.7) 9 (32.1) 16 (57.1) | |

| Number of annual meetings | 10.0 (4.5–40.0) | 6.0 (4.0–36.0) | 0.742 |

| Revision of restricted antimicrobials | 13 (92.9) | 25 (89.3) | 1.000 |

| Dosing recommendations | 14 (100.0) | 27 (96.4) | 1.000 |

| Beta-lactam extended/continuous administration recommendations | 12 (85.7) | 19 (67.9) | 0.283 |

| Didactic education | 10 (71.4) | 15/27 (55.6) | 0.501 |

| Preauthorization | 7 (50.0) | 13 (46.4) | 1.000 |

| Prospective audit and feedback | 10 (71.4) | 15 (53.6) | 0.331 |

| Antimicrobial spectrum related recommendations | 13/13 (100.0) | 20 (71.4) | 0.040 |

| Antimicrobial therapy duration recommendations | 13 (92.9) | 26 (92.9) | 1.000 |

| Antimicrobial-related side events monitoring | 13 (92.9) | 17 (60.7) | 0.036 |

| Antimicrobial–drug interaction monitoring | 14 (100.0) | 24 (85.7) | 0.283 |

| Antimicrobial desensitisation Number of desensitisations | 6 (42.9) 4.5 (2.5–38.0) | 6 (21.4) 1.0 (1.0–8.8) | 0.169 0.171 |

| Intravenous-to-oral antimicrobial switch | 13 (92.9) | 22 (78.6) | 0.392 |

| Antimicrobial guidelines development | 14 (100.0) | 27 (96.4) | 1.000 |

| Recommendations to perform cultures or swabs | 5 (35.7) | 10 (35.7) | 1.000 |

| Investigation Number of hours in a month | 5 (35.7) 8.0 (3.5–45.0) | 6 (21.4) 3.0 (1.5–6.3) | 0.459 0.126 |

| Teaching | 9 (64.3) | 11 (39.3) | 0.192 |

| Therapeutic drug monitoring Recommendations are made by ASP pharmacists | 11 (78.6) 5 (45.5) | 19 (67.9) 11 (57.9) | 0.485 0.707 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of importance of performed ASP activities | Didactic education and guidelines development: 21.7 Antimicrobial spectrum-related recommendations: 13.0 | Antimicrobial spectrum-related recommendations: 28.3 Antimicrobial duration-related recommendations: 19.6 Beta-lactam administration: 13.0 | Antimicrobial duration: 37 Intravenous-to-oral switch: 15.2 Antimicrobial spectrum: 13.0 | TDM: 17.4 Antimicrobial duration: 15.2 Guidelines development and antimicrobial spectrum: 13.0 | Didactic education: 18.8 Antimicrobial spectrum: 16.7 Guidelines development: 14.6 |

| Time required for ASP activities | Guidelines development: 25.6 Didactic education: 23.3 Investigation/teaching: 20.9 | TDM: 18.2 Didactic education: 15.9 Guidelines development: 13.6 | Guidelines development: 34.1 Beta-lactam administration, TDM, didactic education, side-events monitoring: 11.4 | Didactic education: 22.7 TDM: 13.6 Antimicrobial spectrum: 11.4 | Antimicrobial duration: 20.5 TDM: 13.6 Investigation/teaching, side-events monitoring: 11.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Echeverria-Esnal, D.; Hernández, S.; Murgadella-Sancho, A.; García-Paricio, R.; Ortonobes, S.; Barrantes-González, M.; Padullés, A.; Almendral, A.; Tuset, M.; Limón, E.; et al. Cross-Sectional Survey on the Current Role of Clinical Pharmacists among Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in Catalonia: Much Ado about Nothing. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040717

Echeverria-Esnal D, Hernández S, Murgadella-Sancho A, García-Paricio R, Ortonobes S, Barrantes-González M, Padullés A, Almendral A, Tuset M, Limón E, et al. Cross-Sectional Survey on the Current Role of Clinical Pharmacists among Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in Catalonia: Much Ado about Nothing. Antibiotics. 2023; 12(4):717. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040717

Chicago/Turabian StyleEcheverria-Esnal, Daniel, Sergi Hernández, Anna Murgadella-Sancho, Ramón García-Paricio, Sara Ortonobes, Melisa Barrantes-González, Ariadna Padullés, Alexander Almendral, Montse Tuset, Enric Limón, and et al. 2023. "Cross-Sectional Survey on the Current Role of Clinical Pharmacists among Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in Catalonia: Much Ado about Nothing" Antibiotics 12, no. 4: 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040717

APA StyleEcheverria-Esnal, D., Hernández, S., Murgadella-Sancho, A., García-Paricio, R., Ortonobes, S., Barrantes-González, M., Padullés, A., Almendral, A., Tuset, M., Limón, E., Grau, S., & on behalf of the Catalan Infection Control Antimicrobial Stewardship Programme (VINCat-ASP). (2023). Cross-Sectional Survey on the Current Role of Clinical Pharmacists among Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in Catalonia: Much Ado about Nothing. Antibiotics, 12(4), 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040717