Abstract

Impedance biosensors are manufactured on glass slides using a semiconductor process to monitor cell growth and cell–drug reactions in real time, and the results are compared with biological assay results to confirm the validity of impedance measurement method. Approximately 10,000 cells per well were cultured for 48 h, after which 6.67 μg/mL puromycin was injected to observe apoptosis over the following 48 h. A frequency sweep from 1 kHz to 1 MHz was performed to determine the optimal frequency range, identifying 367–440 kHz as the most sensitive for detecting impedance changes. Impedance was measured every 10 min for 96 h. Capacitance gradually increased during cell proliferation, while after drug administration, a transient increase occurred within 9 h, followed by a rapid decline, indicating cell death within 24 h. The sensor utilized Electrical Cell–substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) to detect real-time changes in cell status without the need for staining or destruction. Comparison with conventional biological assays such as MTS and FACS confirmed that the impedance biosensor provided higher sensitivity and quantitative accuracy in monitoring both cell proliferation and apoptosis. This study demonstrates that the developed biosensor enables label-free, non-invasive, and continuous monitoring of cellular behaviors with acceptable coincidence with 3 different biological assay results. Impedance biosensor presents a promising alternative to conventional biological assays and offers potential applications in drug screening, cytotoxicity evaluation, and real-time biological monitoring.

1. Introduction

Conventional methods for measuring cell growth and death involve staining cells and observing them directly under a microscope, allowing assessment of cell density and morphology [,]. In a study by Giaever and Keese in the late 20th century, cells at various densities were cultured on gold electrodes deposited via evaporation, and external electric fields were applied to measure overall impedance. Their results suggested that the measured impedance reflected changes in cell density and morphology []. Following this, researchers introduced the Cell–substrate Impedance Sensor (CIS) to observe cell behavior through electrical signals []. In the 1990s, a more advanced system called Electric Cell–Substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) was developed [,].

Traditional biological assays, MTT and Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) are widely used. These biological assays are well known and are used as reference methods for cell growth and drug reaction monitoring. However, they cannot provide real-time, continuous observation of living cells. Furthermore, these methods require multiple sample preparations, increasing the likelihood of measurement errors. Due to these limitations, ECIS is gaining attention as a promising alternative for a wide range of biological applications. Compared traditional biological assay, ECIS provides continuous and real-time monitoring of cell behavior.

Compared with our previous impedance biosensor studies, this work newly focuses on the systematic validation of the impedance-based measurements by directly benchmarking them against three standard biological assays (MTS, FACS and Annexin V) under the same experimental conditions. We show that the impedance biosensor provides label-free, continuous monitoring while maintaining acceptable coincidence with conventional assays, and in many cases reveals earlier apoptotic changes that are not captured by endpoint biological methods.

To position our approach within the existing literature, representative impedance-based studies on adherent cell cultures (refs. [,,,,]) were surveyed and are summarized in Table 1. These works cover ECIS type systems applied to cell proliferation, cytotoxicity testing, and barrier-function monitoring. While they clearly demonstrate the advantages of label-free, real-time impedance monitoring over conventional endpoint assays, most focus on qualitative impedance changes at a single or proprietary frequency index and rarely include systematic frequency-sweep analysis or direct, quantitative comparison with multiple biological assays. In contrast, the present study combines frequency-optimized impedance measurements with side-by-side validation against three independent biological assays under matched conditions, thereby providing an integrated assessment of the impedance method for cell growth and drug-reaction monitoring.

Table 1.

Representative impedance-based studies on adherent cell cultures and comparison with this work.

The ECIS analysis is a method of examining the cell state by observing the change in impedance according to the contact area and contact degree between the cell and the sensor electrode. Measured impedance values are strongly affected with the existence of cells. If there is no cell on the electrode, a current flow without any other interference. However, when cells are placed on the electrode, the cell membrane is a phospholipid double layer insulator, so current flows between the cells [,,]. The current measured through these various paths has a great influence on the measured impedance, so that the shape and condition of the cell can be observed by impedance change. In addition, ECIS methods are convenient and non-invasive by enabling the real-time monitoring of cell conditions with in vitro measurements [,,].

Extensive research and development using the ECIS method are currently underway, with numerous applications documented in recent studies. ECIS systems have been applied across various fields, including cancer research, virology, drug composition analysis, and food safety, as well as in cellular biology for analyzing cell behavior and cytotoxicity [,,,,,,,,]. Additionally, ongoing studies are exploring sensor structure optimization and advanced analysis techniques, contributing to a growing body of literature on real-time cell monitoring [,,].

In this study, the processes of cell growth and apoptosis were observed in real time, demonstrating high accuracy and sensitivity of the developed system. By comparing the electrical signals from the impedance biosensor with conventional biological measurements, we confirmed that the electrical signals accurately reflect biological changes such as cell proliferation and drug responses. An impedance biosensor was fabricated on a glass slide, and the growth of NIH/3T3 cells, as well as apoptosis induced by puromycin, was monitored electrically. These results were compared with a control sample containing only medium to verify that the observed signals originated from cellular activity. Repeated experiments were conducted to confirm the reproducibility of the results. After that, cell proliferation and death were assessed using MTS assays and FACS, allowing for comparative analysis. The findings demonstrated the superior sensitivity and quantification capability of the impedance biosensor relative to conventional biological methods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Manufacturing Processes of Impedance Biosensors

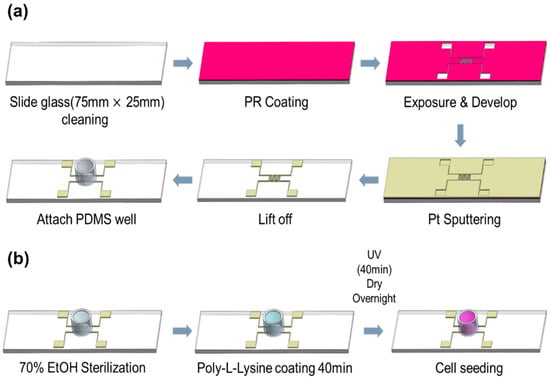

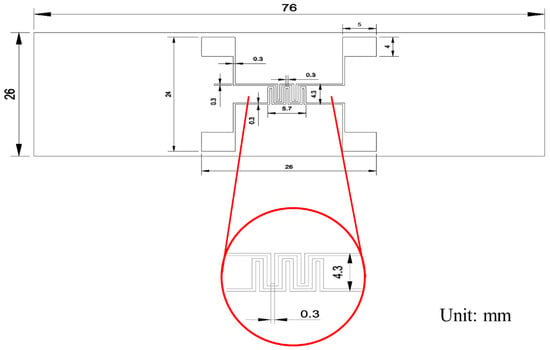

Figure 1a illustrates the fabrication process of the impedance biosensor. The biosensors were constructed on transparent slide glass substrates to allow microscopic observation of cell growth and apoptosis. An impedance pattern was manufactured on the slide glass for the monitoring of the variations in impedance with the growth and death of cells, and in this case, platinum (Pt target, e.g., 99.99%, Kojundo Chemical Laboratory Co., Ltd., Sakado, Japan) was used as an electrode to enable the growth of cells on the surface of sensor. The fabrication process involved photolithography for precise patterning. A photoresist (PR, AZ 5214E, Merck Performance Materials GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) was spin-coated at 4500 RPM for 35 s and soft-baked at 100 °C for 10 min. After aligning the mask, the exposed PR on the electrode region was developed. An 80 nm thick Pt layer was then deposited via sputtering. Prior to Pt deposition, a 5 nm chromium (Cr) adhesion layer was applied to improve bonding between the Pt and SiO2 substrate. Following metal deposition, the lift-off process was used to define the electrode pattern. To protect the electrode pads during electrical probing, a 2000 Å thick aluminum (Al) layer was deposited by thermal evaporation. A PDMS well was attached to the electrode area for cell seeding. The PDMS well, fabricated using a biopsy punch, had an inner diameter of 0.8 cm and an outer diameter of 1.0 cm. The complete process is depicted in Figure 1. The final electrode pattern had a line width of 0.3 mm and an inter-electrode spacing of 0.3 mm, as shown in Figure A1.

Figure 1.

(a) Process of manufacturing impedance biosensor (b) Environmental setting process for cell growth inside sensor well.

2.2. Creating a Cell Culture Environment Within PDMS Well

To prepare a suitable environment for cell culture, additional surface treatment was conducted on the sensors fabricated as described in Section 2.1, as illustrated in Figure 1b. First, the interior of the PDMS well where cell growth occurs was cleaned and sterilized with 70% ethanol. After that, a 0.01% solution of Poly-L-lysine is coated during 40 min for the attachment of cell, irradiated with ultraviolet (UV) about 40 min for sterilization, and dried overnight. Following this preparation, approximately 10,000 NIH/3T3 cells were seeded into each PDMS well and incubated for 48 h to allow for cell attachment and proliferation.

2.3. Principles of Impedance Biosensors

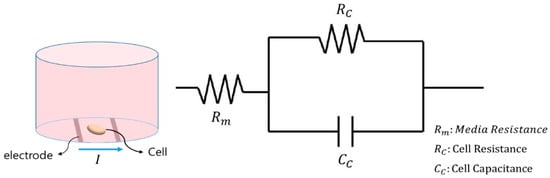

As noted in the introduction, impedance biosensors have been continuously developed through the implementation of the Electric Cell–substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) system, originating from the foundational work by Giaever and Keese in 1983. The ECIS system enables quantitative analysis of the shape and dynamic behavior of cultured cells. When cells and DMEM are introduced into the well containing the sensor electrodes, the cells settle and adhere to the electrode surface. As cells attach, they interfere with the current flow, leading to changes in the measured impedance []. Under the assumption that current is applied to measure individual cells, the system captures both the resistance of the medium and the resistance and capacitance of the cells. The electrical model of this system can be represented as shown in Figure A2.

This research introduces the ECIS system to manufacture an impedance biosensor through the processes of Section 2.1 and Section 2.2 and applies a constant AC between the electrodes. The outer and inner liquids of cells are composed of conductors, and the cell membrane is a phospholipid double layer that acts as an insulator, so electric charges accumulate at the interface between the cell membranes, and each cell acts like a capacitor. Therefore, an increase in the surface area of the cell or the number of cells due to cell growth causes a change in capacitance values [,,,]. The behavior of the cell can be quantitatively confirmed through a change in the capacitance value measured by the sensor.

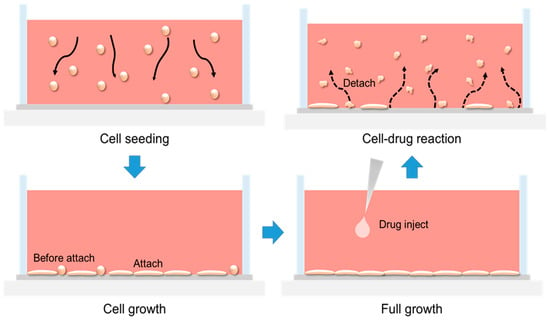

The mechanism occurring inside the impedance biosensor well is illustrated in Figure A3. When cells are seeded, they settle to the bottom of the well by gravity and adhere to the sensor surface. The NIH/3T3 cells used in this study are fibroblasts, which exhibit a round morphology immediately after seeding and gradually spread into a flat, elongated shape upon attachment [,]. Once the cells have proliferated and covered the sensor surface, puromycin is introduced to induce apoptosis. Puromycin, a naturally occurring amino nucleoside antibiotic, structurally resembles the 3′ end of aminoacyl-tRNA. During protein synthesis, it incorporates into the elongating peptide chain in place of tRNA, thereby inhibiting ribosomal catalysis and prematurely terminating translation [,]. Following puromycin treatment, the cells undergo apoptosis and gradually detach from the electrode surface.

2.4. Experimental Conditions and Materials

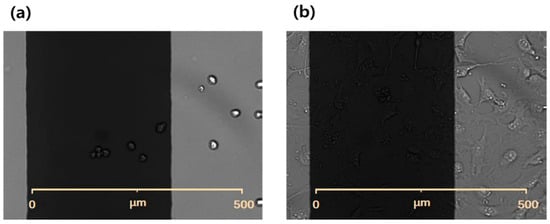

The cells used in this study were NIH/3T3 fibroblasts, originally derived from mouse embryonic tissue. These cells typically measure approximately 18 μm immediately after seeding, and can grow to over 100 μm in diameter as they proliferate and adhere to the culture substrate. Figure A4a shows the cells immediately after seeding, while Figure A4b shows their morphology after 24 h of incubation.

For cell culture, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Corning, Cat. No. 10-013-CV) containing 4.5 g/L glucose, L-glutamine, and sodium pyruvate was used, supplemented with 10% calf serum and 1% streptomycin. Puromycin (Gibco™, A11138-03, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) was diluted to a working concentration of 10 μg/mL in culture medium. The CO2 incubator was maintained at 37 °C with over 95% humidity and 5% CO2 concentration [].

Under these conditions, cells cultured on the sensor were monitored in real time using both microscopy and electrical measurements. After 48 h, the wells were fully populated with cells. Puromycin was then administered at a concentration of 6.67 μg/mL, and apoptosis was monitored in real time under the same conditions.

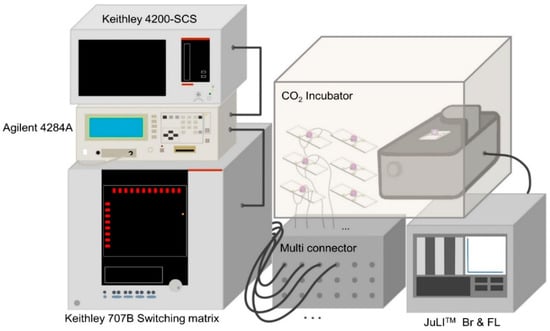

Impedance measurements were conducted using a Keithley 4200-SCS semiconductor (Keithley Instruments, Solon, OH, USA) characterization system connected to an Agilent 4284A LCR meter (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and a Keithley 707B switching matrix (Keithley Instruments, Solon, OH, USA), enabling the sequential measurement of up to six sensors. Real-time microscopic images were captured every 10 min using NanoEnTek’s live-cell imaging system (JuLI™ Br & FL, NanoEnTek Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea). Figure A5 presents a schematic of the measurement system used to simultaneously monitor cellular growth and death both electrically and optically.

2.5. Electrical Measurement Methods

To enhance the reliability of the impedance measurements, the results were compared with those obtained using a conventional biological method capable of assessing cell viability. For this purpose, a cell proliferation assay was conducted to validate cell growth. This assay evaluates the degree of proliferation or viability of living cells based on mitochondrial enzyme activity. Specifically, tetrazolium salts are reduced by mitochondrial enzymes into insoluble purple formazan crystals, and the resulting absorbance correlates with the number of viable cells [,,].

The assay was performed using the CellTiter 96® AQUEOUS One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). NIH/3T3 cells were seeded into five replicate wells at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h to ensure proper attachment. The culture medium was subsequently replaced with MTS reagent at different time points (4, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h after seeding), and cells were incubated for an additional hour. Absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The fold increase in absorbance over time was used to quantify cell proliferation relative to the initial measurement at 4 h.

2.6. FACS (Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting)

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) was employed to assess cell death. FACS is a quantitative method that distinguishes live and dead cells by staining them and analyzing light scattering and fluorescence signals. Specifically, forward scatter (FSC), side scatter (SSC), and fluorescence intensity are measured to evaluate cellular properties and viability. Among various analytical techniques available with FACS, cell cycle analysis was used in this study. This method enables the assessment of all four phases of the cell cycle using flow cytometry. The dead cells are classified as cells that deviate from the cell cycle because the cell cycle stops, and the percentage value of the dead cells among all cells can be confirmed. This approach allowed us to quantitatively monitor drug-induced apoptosis in NIH/3T3 cells after 48 h of culture, providing a complementary validation of the impedance-based measurements [,,].

NIH/3T3 cells were seeded in 6 well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well and treated with puromycin (GibcoTM) at a concentration of 6.67 μg/mL. At various time points between 4 and 45 h post-treatment, cells were harvested using trypsin, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Corning, New York, NY, USA), and fixed in 70% ethanol. For DNA staining, RNase (0.2 mg/mL) was added to the cell suspension and incubated for 30 min. Subsequently, Propidium Iodide (PI; 1 μg/mL, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) was added at room temperature for 15 min. Sub-diploid DNA content, indicative of apoptotic cells, was analyzed using flow cytometry with the FACS Calibur system (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

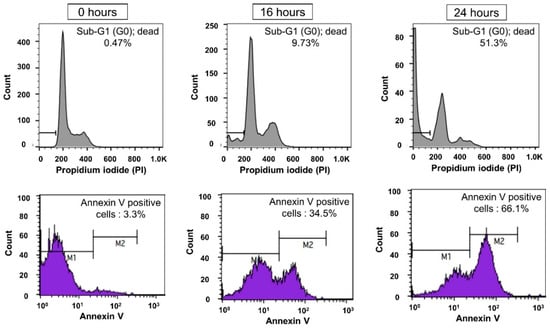

Based on FACS analysis with PI staining, cell cycle distribution was assessed to confirm cell death. To further validate apoptosis in NIH/3T3 cells induced by puromycin and to compare with PI-based results, Annexin V staining was subsequently performed. Annexin V detects early-stage apoptosis by targeting phosphatidylserine (PS), a phospholipid normally located inside the cell membrane. During apoptosis, membrane integrity is compromised, causing PS to translocate to the outside of the cell membrane and become exposed on the cell surface. In the presence of calcium ions, Annexin V specifically binds to this externalized PS, allowing the identification of apoptotic cells [,,].

Similarly to PI staining analysis, cells were cultured on a 6 well plate at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well to treat puromycin at a concentration of 6.67 μg/mL, and after drug treatment, cells were collected using cell scraper and washed with PBS. RNase (0.2 mg/mL) was added to the cell suspension for 30 min, and then 0.5 μg/mL Annexin V (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) was added at room temperature for 15 min. The presence of apoptosis was detected by genetic cytometry using FACS Calibur (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Measurement of Impedance Biosensor According to Frequency

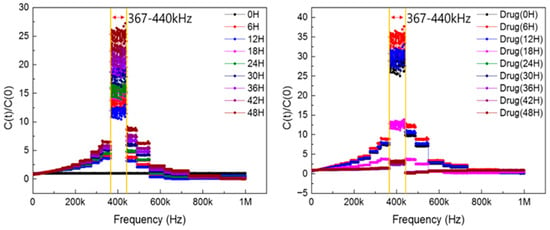

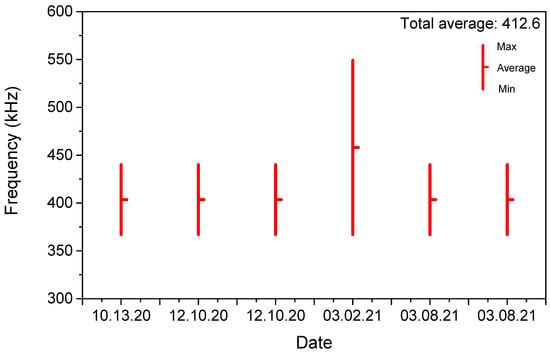

To identify the optimal frequency range for measuring the impedance of cells cultured on the sensor, capacitance and conductance were recorded at 1 h intervals across a frequency sweep. These measurements were performed under both cell proliferation and apoptosis conditions to observe how cell related impedance signals varied over time. The results enabled the identification of the frequency range most sensitive to changes in capacitance associated with cell behavior. Figure 2 shows the frequency-dependent variation in C(t)/C(0) for a representative sample, confirming that the most responsive region lies between 367 kHz and 440 kHz. We specify that Figure 2 is a representative single-sensor frequency map derived from full sweeps, and we state that the identified sensitive band was reproduced across all six sensors (see Figure 3d and Section 2 Materials and Methods). Based on the overall analysis, the highest-sensitivity band was identified as 350–550 kHz. To strengthen this frequency identification, we repeated full sweeps on six independent sensors measured on different dates; in all cases, the identified bands overlapped within 350–550 kHz, with the aggregate mean clustering near ~400 kHz. Summary statistics for the bands and the overall mean are provided in Appendix A.7 Figure A7, and between-sensor overlays at 400 kHz are shown in Figure 3d.

Figure 2.

Identification of the most sensitive frequency range in impedance biosensors.

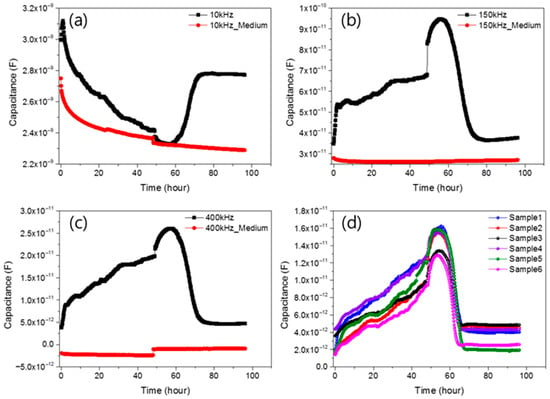

Figure 3.

3 displays representative impedance profiles measured at (a) 10 kHz, (b) 150 kHz, (c) 400 kHz, and (d) reproducibility of six different impedance biosensor samples along with a control graph (red) representing a sensor with only medium (DMEM) and no cells.

3.2. Cell Growth and Drug Response in Impedance Biosensors with Time

In order to confirm the measurement result of the change in capacity according to the frequency sweep, the change in capacity and conductance over time was measured. Both the low and high frequency range were measured to further increase the reliability of the C(t)/C(0) frequency graph. The frequencies were 1 kHz, 3 kHz, 10 kHz, 50 kHz, 100 kHz, 150 kHz, 300 kHz, 400 kHz, 500 kHz, 600 kHz, 700 kHz, and 800 kHz, and measurements were performed in a total of 12 frequency. First, after seeding 10,000 cells in the well of the sensor, the cell growth was measured every 10 min for 48 h to observe the cell condition. After that, the death of cells grown by injecting drugs was measured and observed every 10 min. As a result, in the case of capacitance, the change in value was not stable up to 50 kHz, and it was confirmed that the normal graph shape was gradually found until the range of 100 kHz. It was confirmed that the shape of the graph appeared stably in a higher frequency range than after 300 kHz. Looking at the graph in Figure 3, the impedance graphs measured at (a) 10 kHz, (b) 150 kHz, (c) 400 kHz are shown along with the control graph (the impedance result measured only by the medium, red).

To verify reproducibility, measurements were repeated on six sensors, with results shown in Figure 3d at 400 kHz. While the extent of signal change varied slightly due to differences in cell growth and death, all samples followed the same overall trend. Capacitance values at initial seeding and after complete cell death were nearly identical across samples, confirming consistency.

To confirm that capacitance changes were due to cell growth, control sensors without cells were measured under identical conditions. These showed minimal variation during incubation and after drug treatment, indicating that observed changes originated from cellular activity. At 400 kHz, capacitance increased rapidly within the first 4 h after seeding, then gradually over the next 48 h. This reflects initial cell settling, followed by progressive growth and attachment on the sensor surface. Capacitance increased as cells proliferated over 48 h. After puromycin injection, a drug-induced response was monitored for an additional 48 h. Immediately after drug administration, a distinct capacitance shift was observed initially rising for approximately 9 h, then decreasing sharply. This transient increase is attributed to osmotic swelling from drug−cell interactions []. The subsequent drop in capacitance indicates cell death. To verify reproducibility, measurements were repeated on six sensors, with results shown in Figure 3d at 400 kHz. While the extent of signal change varied slightly due to differences in cell growth and death, all samples followed the same overall trend. Capacitance values at initial seeding and after complete cell death were nearly identical across samples, confirming consistency.

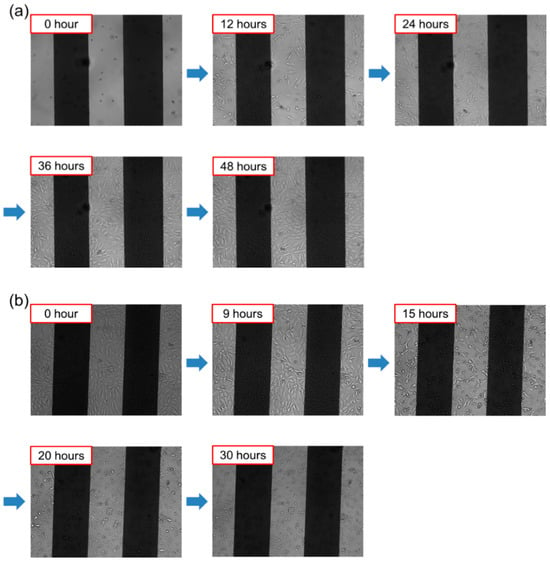

3.3. Process of Cell Growth Within the Impedance Biosensor Well

Figure A6a shows real time images captured by JuLI™ Br & FL during cell growth and death. Images taken every 12 h illustrate gradual cell proliferation, with the well reaching full confluence by 48 h. At this point, puromycin (6.67 μg/mL) was added. In Figure A6b, little change is observed during the first 9 h post-injection, but rapid cell death becomes evident between 9 and 24 h, as shown in 5 h interval images.

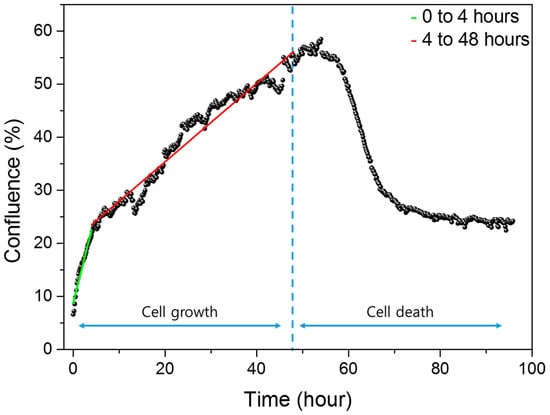

3.4. Intra-Sensor Cell Share in Images Observed by Microscope

Cell growth and death were analyzed using NanoEnTek’s JuLI™ Br & FL, which generated confluence graphs representing the percentage of area occupied by cells. As shown in Figure 4, confluence increased rapidly during the initial hours after seeding, reflecting the settling of cells to the bottom of the well. After about four hours, the confluence gradually increases as the cells completely sink and divide as they adhere to the floor. This shift in growth rate is evident from the change in slope before and after 4 h. To quantify this, curve fitting was performed separately for the periods of 0–4 h and 4–48 h. The resulting fitted curves are shown in green (early phase) and red (later phase), with the respective equations provided.

Figure 4.

Confluence data quantifying the area occupied by cells in the electrodes in the well with microscopic images during cell growth and death.

In our previous study [], we characterized the differences in cellular growth behavior between the early and late phases and demonstrated that these phase-specific behaviors were distinctly reflected in the impedance signals. These biological distinctions were consistently mirrored in the impedance measurements, with reproducible signal patterns corresponding to each growth stage. This correlation confirms that the phase-specific characteristics of cell behavior can be reliably captured through impedance measurements, thereby enhancing the interpretability and validity of image-based confluence analysis within our impedance biosensor platform.

The confluence graph from 0 to 4 h reflects cell morphology changes and settling behavior, as cells sink and attach to the sensor surface. From 4 to 48 h, the graph represents gradual cell proliferation.

Following 48 h of growth, puromycin was administered, and confluence decreased as apoptosis progressed. At 48 h, the confluence value was 55.39%, not approaching 100%, due to dark electrode regions in the image that hinder cell detection. Similarly, at the onset of cell death, the initial confluence was 53.98%. Minor fluctuations in the graph are attributed to image analysis variability caused by cell movement.

3.5. Biological Measurements According to Cell Growth and Drug Reaction

To compare electrical signals from impedance biosensors with biological data, cell growth and death were also evaluated using MTS assay and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). MTS assay was used to assess cell proliferation and viability, while FACS provided a clearer analysis of the apoptosis process.

3.5.1. Cell Proliferation Analysis

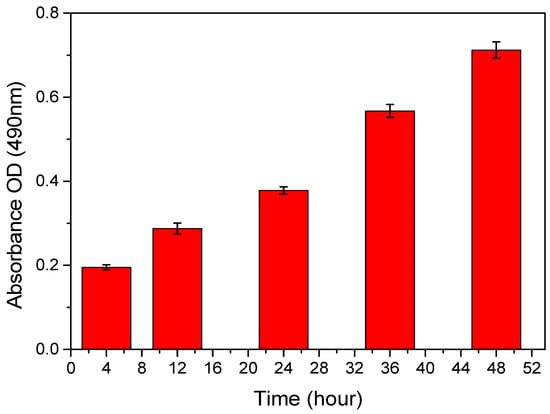

Cell proliferation of NIH/3T3 cells was evaluated using the MTS assay, which measures the reduction in the tetrazolium compound MTS into formazan by mitochondrial enzymes in viable cells []. As shown in Figure A8, absorbance increased from 0.1877 to 0.7265 over time, indicating time-dependent cell growth. Compared to the initial value, cell proliferation increased by 1.44 times at 12 h, 1.96 times at 24 h, 2.95 times at 36 h, and 3.87 times at 48 h.

3.5.2. Cell Death Analysis After Puromycin Treatment

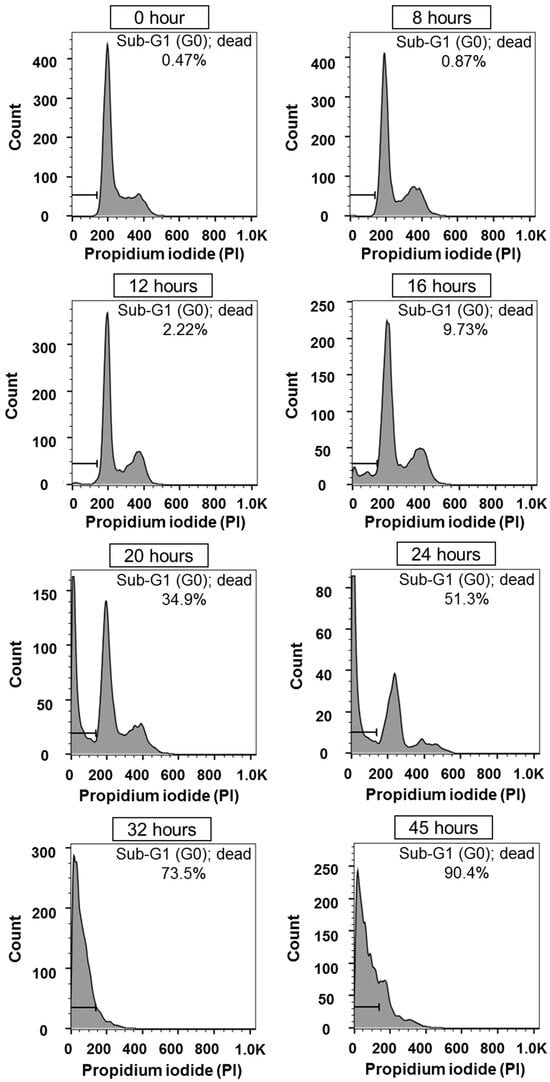

Puromycin, a 3′-terminal analog of aminoacyl-tRNA, incorporates non-specifically into elongating polypeptide chains, leading to premature termination of translation and induction of apoptosis [,]. During apoptosis, endonuclease activation causes DNA fragmentation, which can be detected using intercalating dyes such as Propidium Iodide (PI) []. To assess the extent of apoptosis induced by puromycin, DNA content was analyzed via flow cytometry. At 0 h, NIH/3T3 cells displayed a typical cell cycle distribution with G1 (2n), S (2n–4n), and G2/M (4n) phases, and The area of sub-G1 (less than 2n) is only 0.47%, meaning that most cells are alive at 0 h. However, the sub-G1 population increased progressively, reaching 90.4% at 45 h after puromycin treatment.

Flow cytometry results for cell death are presented in Figure A8. Data were collected every 4 h up to 32 h, then at 6–7 h intervals as most cells had undergone apoptosis beyond that point. The figure highlights key transitions in cell death progression. Apoptotic cells, detected in the sub-G1 region (absorbance range: 0–180 on the x-axis), represent cells that have exited the normal cell cycle. From 0 to 8 h post-treatment, minimal changes were observed. A leftward shift in the graph began at 12 h, indicating early apoptosis. A significant increase in apoptotic cells occurred between 16 and 20 h, with a rapid shift continuing through 24 h.

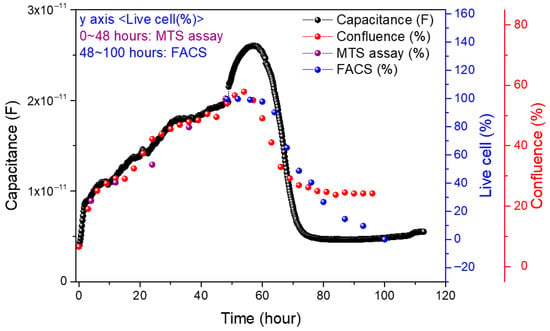

3.6. Comparison of Impedance Biosensors and Biological Measurements

Figure 5 compares cell growth and death trends measured by impedance biosensors, confluence analysis, and MTS assay. The three datasets show highly consistent growth patterns, demonstrating the reliability of impedance-based measurements. MTS assay results begin at 4 h post-seeding due to the time required for cell attachment and growth. In contrast, impedance biosensors can detect cellular changes immediately after seeding, capturing capacitance increases from 0 to 4 h as cells settle and contact the sensor surface. This early sensitivity is also reflected in the confluence data, where the rate of increase is steeper in the initial hours. These findings indicate that impedance biosensors can sensitively detect subtle changes in cell behavior from the earliest stages of attachment and proliferation.

Figure 5.

Comparison of impedance biosensor measured electrical signals with MTS assay and FACS data.

In the cell death phase, data from impedance biosensors, confluence analysis, and FACS were compared, as shown in Figure 5. Among the three, impedance biosensors demonstrated the highest sensitivity in detecting early apoptotic changes. Unlike confluence and FACS, which showed delayed responses, impedance signals captured cell state changes immediately following drug administration. While confluence values decreased to about half the level observed during growth, impedance measurements showed a complete return to baseline (0 h value) once all cells had died. This discrepancy arises because confluence measures the surface area occupied by cells, while impedance reflects both cell attachment and viability. Comparison with FACS further supports this finding. Microscopy and impedance data indicated near-complete cell death by 20 h and total death by 24 h post-injection. However, FACS still showed 49% viable cells at 24 h, suggesting that impedance biosensors detect apoptosis with greater sensitivity than optical staining-based methods.

FACS analysis using PI staining showed that 49% of NIH/3T3 cells remained viable 24 h after puromycin treatment, based on cell cycle profiles. To further validate these results, Annexin V staining was performed. As shown in Figure A9 and Figure A10, the PI-based sub-G1 analysis indicated 49% viability at 24 h, while Annexin V staining revealed 34% of cells still alive at the same time point. In contrast, microscopic images confirmed that nearly all cells had died and exhibited a shrunken morphology by 24 h. Similarly, impedance biosensor data reflected complete cell death. These findings suggest that impedance biosensors can detect apoptosis more sensitively and efficiently than conventional methods, enabling real-time monitoring of cell viability under live incubation conditions.

4. Discussion

This work establishes an impedance-based biosensing platform that captures the full timeline of NIH/3T3 growth and drug-induced apoptosis in a label-free, non-destructive, and continuous manner. Three results are central. First, a broad sweep (1 kHz–1 MHz) revealed a high-sensitivity band centered at ~367–440 kHz (overall 350–550 kHz). Second, time-lapse measurements at 12 discrete frequencies confirmed that the low-frequency response (≤10 kHz) is governed by electrode polarization and bulk medium conductivity, so cell-dependent variations are largely masked; cell-specific features emerge near 100–150 kHz and trajectories become stable and reproducible at ≥200 kHz. This trend is consistent with ECIS/electrochemical-impedance theory, in which low-f behavior is interfacial-dominated whereas mid–high-f signals (β-dispersion) report cell–substrate coupling and membrane capacitance [,]. Third, at a representative 400 kHz, capacitance captured the entire biological sequence—rapid rise over the first 4 h, gradual increase during 48 h, a transient post-drug rise (~9 h), and a sharp decline to baseline within ~24 h—providing an interpretable electrical fingerprint of apoptosis-driven detachment.

A key methodological decision was to emphasize the capacitance component rather than total impedance or resistance alone. Capacitance is directly modulated by membrane permittivity, cell–substrate sealing, spreading area, and junctional reorganization, making it particularly responsive to early morphological/physiological changes that precede overt death. The transient increase after puromycin—a feature that could be averaged out in scalar impedance—was consistently observed and is plausibly explained by osmotic swelling and adhesion changes during the early drug–cell interaction phase. Component-level interpretation thus improves both sensitivity and biological specificity of ECIS-type readouts.

Orthogonal measurements support these interpretations. Medium-only controls exhibited minimal drift during incubation and after drug addition, indicating that the observed electrical changes originate from cellular activity rather than bath artifacts. Microscopy-based confluence tracked the same phases: a steeper early slope (0–4 h; settling/adhesion) followed by slower growth (4–48 h) and a decline after drug exposure. Small offsets in absolute confluence (e.g., <100% at 48 h) are attributable to dark electrode regions in the field of view; this explains why confluence may plateau above zero even when impedance has returned to its baseline. Biological assays further contextualized the timeline. MTS reported monotonic proliferation consistent with capacitance increases during growth. During the death phase, flow cytometry revealed a delayed trajectory relative to impedance and imaging: PI-based sub-G1 analysis indicated ~49% viability at 24 h, while Annexin V staining indicated ~34% viability at the same time. In contrast, impedance and microscopy had already reached near-complete death by ~20–24 h. This divergence is reasonable: PI/Annexin V reflect intracellular DNA content or externalized phosphatidylserine under fixed assay conditions, whereas impedance responds immediately to loss of adhesion and sealing, enabling earlier detection of apoptotic progression under live incubation.

The frequency dependence observed here is also informative. Below ~50 kHz, electrode polarization, double-layer capacitance, and stray impedances reduce biological contrast, explaining the instability and poorer reproducibility in this band. Above ~300 kHz, the current paths become increasingly sensitive to cell coverage and membrane capacitive effects, yielding stable, sample-to-sample-consistent trajectories. Identifying a narrow operational window (e.g., 367–440 kHz; representative 400 kHz) thus streamlines acquisition, facilitates cross-study comparison, and enables practical deployment where a single frequency (or a small set) is preferred.

This study has limitations. It focuses on one cell type (NIH/3T3) and one cytotoxic compound (puromycin). Extending to additional cell lines (epithelial, immune, cancer) and drug classes (targeted agents, anti-inflammatory compounds, membrane-active antibiotics) will test generalizability. The observation window (96 h) captures acute cytotoxicity; longer monitoring could uncover delayed or adaptive responses. Finally, while we used imaging and standard biochemical assays for validation, integrating molecular readouts (e.g., caspase activity, or transcriptomics) would deepen mechanistic interpretation of the transient and decline phases.

In sum, by pinpointing an optimal operating band and leveraging capacitance-centric analysis, this work shows that impedance biosensing can detect drug-induced apoptosis earlier and with higher temporal fidelity than conventional endpoint assays, while remaining label-free and non-destructive. The approach is well-suited for quantitative screening, cytotoxicity profiling, and longitudinal monitoring, and it provides a tractable foundation for multimodal workflows that couple real-time electrical sensing with high-content imaging and molecular readouts.

5. Conclusions

In this study, an impedance biosensor capable of measuring cell conditions was manufactured and conditions for cell growth in the sensor were set. Cell growth and death were observed through the manufactured sensor. At this time, frequency sweeps were performed to identify areas that sensitively capture cell state changes according to frequencies. As a result, it was confirmed that the signal was the most sensitive between 367 and 440 kHz. Therefore, in order to determine how the cell state appears from low frequencies to high frequencies, a total of 12 frequencies were targeted, namely 1 kHz, 3 kHz, 10 kHz, 50 kHz, 100 kHz, 150 kHz, 300 kHz, 400 kHz, 500 kHz, 600 kHz, 700 kHz, and 800 kHz, and the results were measured. NIH/3T3 cells were grown in a CO2 incubator for 48 h and then puromycin was injected at a concentration of 6.67 μg/mL and observed for 48 h. It was confirmed that almost all cells died after 24 h of drug injection. As a result of measuring the cell state through an impedance biosensor, it was confirmed that the electrical signal had a greater influence on the medium than the cell state in the low frequency range of 1–10 kHz. From the 100–150 kHz area, it was confirmed that the electrical signal of the impedance biosensor reflected the cell state, and from 300 kHz to 800 kHz, the sensor signal stably appeared. At this time, the impedance biosensor electrical signals at 400 kHz corresponding to the most sensitive frequency range obtained as a result of the experiment were verified and compared with various biological analysis methods such as MTS assay, FACS, and microscopic image confluence. As a result, it was confirmed that cell measurement with impedance biosensors can be monitored more easily, efficiently, and sensitively compared to conventional biological analysis methods. Therefore, the impedance biosensor manufactured in this study shows the possibility to be used as a cell growth and drug reaction monitoring method.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.; methodology, M.J.; validation, G.L., Y.K. and S.-k.K.; investigation, S.-k.K., G.L., Y.K. and D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.L.; writing—review and editing, S.-k.K.; supervision, M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted with the support of the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) grant funded by the Korea Government (MOTIE) (RS-2023-KI002684, HRD Program for Industrial Innovation) of the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology and the Basic Research Support Project (No. 1711198009) of the National Research Foundation of Korea.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Figure A1.

Electrode pattern of impedance biosensor.

Appendix A.2

Figure A2.

Impedance measurement circuit model for one cell.

Appendix A.3

Figure A3.

The growth and death process of cells occurring inside the well of the impedance biosensor.

Appendix A.4

Figure A4.

(a) Cell growth immediately after NIH/3T3 cell seeding (b) 24 h after cell seeding.

Appendix A.5

Figure A5.

Measurement of cell growth and death with impedance biosensor.

Appendix A.6

Figure A6.

(a) The growth of cells and (b) the process of apoptosis of cells after drug treatment as observed under the JuLITM Br & FL microscope.

Appendix A.7

Figure A7.

Sensitive frequency bands and their average frequencies according to frequency sweep results of several samples.

Appendix A.8

Figure A8.

Cell growth MTS assay experimental results for 48 h.

Appendix A.9

Figure A9.

FACS measurement results using propidium iodide (PI) for 52 h after drug injection.

Appendix A.10

Figure A10.

Comparison of FACS experimental results of PI and Annexin V.

References

- Kari, S.; Subramanian, K.; Altomonte, I.A.; Murugesan, A.; Yli-Harja, O.; Kandhavelu, M. Programmed cell death detection methods: A systematic review and a categorical comparison. Apoptosis 2022, 27, 482–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.-M.; Li, Z.-X.; Lin, R.-H.; Shan, J.-Q.; Yu, Q.-W.; Wang, R.-X.; Liao, L.-S.; Yan, W.-T.; Wang, Z.; Shang, L.; et al. Guidelines for Regulated Cell Death Assays: A Systematic Summary, A Categorical Comparison, A Prospective. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 634690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaever, I.; Keese, C.R. Monitoring fibroblast behavior in tissue culture with an applied electric field. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 3761–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keese, C.; Giaever, I. A whole cell biosensor based on cell-substrate interactions. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1–4 November 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaever, I.; Keese, C.R. Micromotion of mammalian cells measured electrically. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 7896–7900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiruppathi, C.; Malik, A.B.; Del Vecchio, P.J.; Keese, C.R.; Giaever, I. Electrical method for detection of endothelial cell shape change in real time: Assessment of endothelial barrier function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 7919–7923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.H.; Zeng, C.; Boitano, S.; Field, J.A.; Sierra-Alvarez, R. Cytotoxicity assessment of gallium- and indium-based nanoparticles toward human bronchial epithelial cells using an impedance-based real-time cell analyzer. Int. J. Toxicol. 2020, 39, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendecka-Wróbel, M.; Pigoń-Zając, D.; Jaszek, M.; Matuszewska, A.; Stefaniuk, D.; Opielak, G.; Piotrowska, K.; Rahnama-Hezavah, M.; Małecka-Massalska, T. Electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) as a convenient tool to assess the potential of low molecular fraction derived from medicinal fungus Cerrena unicolor in action on L929 and CT-26 cell lines. Molecules 2022, 27, 6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, R.; Kalkal, A.; Jindal, S.; Packirisamy, G.; Manhas, S. Four electrode-based impedimetric biosensors for evaluating cytotoxicity of tamoxifen on cervical cancer cells. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallarero, A.; Batista-González, A.E.; Hiltunen, A.K.; Liimatainen, J.; Karonen, M.; Vuorela, P.M. Online measurement of real-time cytotoxic responses induced by multi-component matrices, such as natural products, through electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 27044–27057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Duan, M.; Gao, J.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Wu, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, S.; Ma, X.; Wu, M.; et al. ECIS-based biosensors for real-time monitor and classification of the intestinal epithelial barrier damages. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 915, 116334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.-C.; Chen, W.-L.; Lai, Y.-T.; Hung, Y.-H.; Lo, C.-M. Cell–Electrode Models for Impedance Analysis of Epithelial and Endothelial Monolayers Cultured on Microelectrodes. Sensors 2024, 24, 4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kociubiński, A. Electric Cell-substrate Impedance Sensing in Biocompatibility Research. J. Electr. Bioimpedance 2021, 12, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Liu, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, T.; Kiya, R.; Yang, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Li, M.; Hosokawa, Y.; et al. Assessment of the electrical penetration of cell membranes using four-frequency impedance cytometry. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2022, 8, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, A.S.; Ebrahim, T.; Kani, H.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Carion, T.W.; Berger, E.A. Functional optimization of electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) using human corneal epithelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghtaderi, H.; Sadeghian, G.; Abiri, H.; Khan, F.; Rahman, M.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Rahman, S.M. Electric cell-substrate impedance sensing in cancer research: An in-depth exploration of impedance sensing for profiling cancer cell behavior. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2024, 7, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C.; Chiu, S.-C.; Chao, S.-C.; Liao, H.-Y.; Lee, S.-P.; Huang, C.-C.; Cho, D.-Y. Real-Time Monitoring of the Cytotoxic and Antimetastatic Properties of Cannabidiol in Human Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells Using Electric Cell-Substrate Impedance Sensing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, E.; Yao, J.; Aymond, A.; Chrisey, D.B.; Nieman, G.F.; Bates, J.H.T.; Gaver, D.P. Electric Cell-Substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) as a Platform for Evaluating Barrier-Function Susceptibility and Damage from Pulmonary Atelectrauma. Biosensors 2022, 12, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennington, M.R.; Van de Walle, G.R. Electric Cell-Substrate Impedance Sensing to Monitor Viral Growth and Study Cellular Responses to Infection with Alphaherpesviruses in Real Time. mSphere 2017, 2, e00039-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes-Vélez, S.; Fagoonee, S.; Sanginario, A.; Gallo, V.; Riganti, C.; Pizzi, M.; Altruda, F.; Demarchi, D. Impedance-based drug-resistance characterization of colon cancer cells through real-time cell culture monitoring. Talanta 2021, 222, 121441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahid, A.; Campbell, C.E.; Fong, K.S.; Barnhill, J.C.; Washington, M.A. An evaluation of the impact of clinical bacterial isolates on epithelial cell monolayer integrity by the electric Cell-Substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) method. J. Microbiol. Methods 2020, 169, 105833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.; Oh, S.-W. Electrochemical impedimetric biosensors for food safety. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, L.; Hofmann, K.; Geiger, F.; Dietrich, A. Electrical cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) in lung biology and disease. Appl. Res. 2024, 3, e202400059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.; Linne, K.; Bulfone, T.C.; Hossain, T.; Ibn Sina, A.A.; Bickler, P.L.; Fry, B.G.; Lewin, M.R. Electrical Cell Impedance Sensing (ECIS): Feasibility of a Novel In Vitro Approach to Studying Venom Toxicity and Potential Therapeutics. Toxins 2025, 17, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, A.; Joseph, E.; Clement, P.; Alvarez, G.; Crogman, H.T. Biophysical Analysis of EGCG’s Protective Effects on Camptothecin-Induced Oxidative Stress in Bone-like Cancer Cells Using Electric Cell-Substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS). Biophysica 2024, 4, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, P.; Serrano, J.A.; Olmo, A. 3D-Printed Sensors and Actuators in Cell Culture and Tissue Engineering: Framework and Research Challenges. Sensors 2020, 20, 5617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Jiang, D.; Gu, C.; Qiu, Y.; Wan, H.; Wang, P. 3D microgroove electrical impedance sensing to examine 3D cell cultures for antineoplastic drug assessment. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2020, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, X.; Liu, K.; Lan, T.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Z. Recent Advances in Electrical Impedance Sensing Technology for Single-Cell Analysis. Biosensors 2021, 11, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasiviswanathan, U.; Poddar, S.; Kumar, C.; Jit, S.; Mahto, S.K.; Sharma, N. A portable standalone wireless electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) system for assessing dynamic behavior of mammalian cells. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimenko, T.; Nikulin, S.; Zakharova, G.; Poloznikov, A.; Petrov, V.; Baranova, A.; Tonevitsky, A. Impedance Spectroscopy as a Tool for Monitoring Performance in 3D Models of Epithelial Tissues. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 7, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, K.; Varma, M.; Sen, P. Double-peak signal features in microfluidic impedance flow cytometry enable sensitive measurement of cell membrane capacitance. Lab A Chip 2020, 20, 4296–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, T.; Lim, K.; Sultan, T.; Lee, J.S.; Park, J.; Ju, H.W.; Park, C.; Jang, M. The real-time monitoring of drug reaction in HeLa cancer cell using temperature/impedance integrated biosensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 291, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Jeong, J.; Kim, Y.; Kang, D.; Shin, S.; Lee, J.; Jeon, S.H.; Jang, M. Growth and Drug Interaction Monitoring of NIH 3T3 Cells by Image Analysis and Capacitive Biosensor. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1248–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, R.; Nishida, K.; Matsumoto, H.; Murakami, D.; Kobayashi, S.; Anada, T.; Tanaka, M. Attachment and Growth of Fibroblast Cells on Poly (2-Methoxyethyl Acrylate) Analog Polymers as Coating Materials. Coatings 2021, 11, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, S.; Peruško, D.; Mimidis, A.; Kavatzikidou, P.; Kovač, J.; Ranella, A.; Novaković, M.; Popović, M.; Stratakis, E. Response of NIH 3T3 Fibroblast Cells on Laser-Induced Periodic Surface Structures on a 15×(Ti/Zr)/Si Multilayer System. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chang, S.T.-L.; Ward, F.R.; Cate, J.H.D. Selective inhibition of human translation termination by a drug-like compound. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviner, R. The science of puromycin: From studies of ribosome function to applications in biotechnology. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1074–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kang, D.; Kim, S.; Hong, E.; Jang, M. Capacitance Contribution of NIH/3T3 Cells Existing on and between Electrodes of an Impedance Biosensor. Biosensors 2023, 13, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi, M.; Turnbull, T.; Sebastian, S.; Kempson, I. The MTT Assay: Utility, Limitations, Pitfalls, and Interpretation in Bulk and Single-Cell Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Dai, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, L.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, S.; Zhou, L. Cimifugin Inhibits Inflammatory Responses of RAW264.7 Cells Induced by Lipopolysaccharide. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Liu, R.; Hu, M.; Rong, X.; Bai, L.; Xu, L.; Mao, Y.; Hasimu, H.; Sun, Y.; He, J. JAX2, an ethanol extract of Hyssopus cuspidatus Boriss, can prevent bronchial asthma by inhibiting MAPK/NF-κB inflammatory signaling. Phytomedicine 2019, 57, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.-Y.; Song, J.-D.; Liang, Z.-Y.; Oskouei, K.; Xiao, X.-Q.; Hou, W.-Z.; Li, J.-T.; Yang, Y.-S.; Wang, M.-L.; Murbach, M. Apoptotic Effect of 1800 MHz Electromagnetic Radiation on NIH/3T3 Cells. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, Z.; Fang, J.; Xu, A.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z. H19-derived miR-675 contributes to bladder cancer cell proliferation by regulating p53 activation. Tumor Biol. 2015, 37, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xing, H.; Li, S.; Yu, J.; Li, H.; Liu, S.; Tian, Z.; Tang, K.; Rao, Q.; Wang, M.; et al. Up-regulated A20 promotes proliferation, regulates cell cycle progression and induces chemotherapy resistance of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Leuk. Res. 2015, 39, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwicker, V.E.; Yeo, J.H.; Fraser, S.T.; New, E.J.; Jolliffe, K.A. Chapter Fourteen—Detection of cell-surface phosphatidylserine using the fluorogenic probe P-IID. Methods Enzymol. 2020, 640, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Chipot, C.; Scheuring, S. Annexin-V stabilizes membrane defects by inducing lipid phase transition. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Han, Y.; Ye, Y.; Wei, X.; Li, G.; Jiang, W. Atmospheric fine particulate matter (PM2.5) induces pulmonary fibrosis by regulating different cell fates via autophagy. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 923, 171396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asphahani, F.; Thein, M.; Wang, K.; Wood, D.; Wong, S.S.; Xu, J.; Zhang, M. Real-time characterization of cytotoxicity using single-cell impedance monitoring. Analyst 2012, 137, 3011–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.; Kim, Y.; Lee, G.; Choi, J.; Yang, J.; Jang, M. Single-cell capacitance analysis of NIH/3T3 cells using an impedance biosensor. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2023, 83, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellini, F.; Tani, A.; Zecchi-Orlandini, S.; Giannelli, M.; Sassoli, C. In Vitro Evidences of Different Fibroblast Morpho-Functional Responses to Red, Near-Infrared and Violet-Blue Photobiomodulation: Clues for Addressing Wound Healing. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gsottberger, F.; Meier, C.; Ammon, A.; Parker, S.; Wendland, K.; George, R.; Petkovic, S.; Mellenthin, L.; Emmerich, C.; Lutzny-Geier, G.; et al. Targeted inhibition of protein synthesis renders cancer cells vulnerable to apoptosis by unfolded protein response. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abasi, S.; Aggas, J.R.; Garayar-Leyva, G.G.; Walther, B.K.; Guiseppi-Elie, A. Bioelectrical Impedance Spectroscopy for Monitoring Mammalian Cells and Tissues under Different Frequency Domains: A Review. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2022, 2, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowell, L.L.; Yakisich, J.S.; Aufderheide, B.; Adams, T.N.G. Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy for Monitoring Chemoresistance of Cancer Cells. Micromachines 2020, 11, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).