Abstract

Integrating artificial intelligence (AI) with wearable sensor technologies can revolutionize the monitoring and management of various chronic diseases and acute conditions. AI-integrated wearables are categorized by their underlying sensing techniques, such as electrochemical, colorimetric, chemical, optical, and pressure/stain. AI algorithms enhance the efficacy of wearable sensors by offering personalized, continuous supervision and predictive analysis, assisting in time recognition, and optimizing therapeutic modalities. This manuscript explores the recent advances and developments in AI-powered wearable sensing technologies and their use in the management of chronic diseases, including COVID-19, Diabetes, and Cancer. AI-based wearables for heart rate and heart rate variability, oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, and temperature sensors are reviewed for their potential in managing COVID-19. For Diabetes management, AI-based wearables, including continuous glucose monitoring sensors, AI-driven insulin pumps, and closed-loop systems, are reviewed. The role of AI-based wearables in biomarker tracking and analysis, thermal imaging, and ultrasound device-based sensing for cancer management is reviewed. Ultimately, this report also highlights the current challenges and future directions for developing and deploying AI-integrated wearable sensors with accuracy, scalability, and integration into clinical practice for these critical health conditions.

1. Introduction

Chronic conditions such as cancer, diabetes, and acute infectious diseases like COVID-19 place a tremendous burden on global healthcare systems. Cancer remains one of the leading causes of death globally, mainly due to late diagnosis and limited ability for continuous monitoring of disease progression and treatment response [1]. Conventional diagnostic methods, such as biopsies and imaging, often require multiple clinical visits and are invasive, costly, and time-consuming [2]. Diabetes, a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by persistent hyperglycemia, is another global health challenge. For effective management of diabetes, continuous monitoring of blood glucose levels is needed to avoid complications such as neuropathy, cardiovascular disease, and kidney failure. Traditional glucose monitoring methods, such as finger-prick tests, are invasive and provide only discrete data points [3]. The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the importance of rapid, remote, and scalable diagnostics techniques. Traditional testing approaches, such as RT-PCR and antigen tests, although they are accurate, are limited by sample collection procedures, processing time, and logistical challenges during large outbreaks [4].

Conventional diagnosis approaches for cancer, diabetes, and COVID-19 often involve periodic visits to healthcare providers, submitting the sample for analysis, which can result in delayed detection of disease progression or complications. It is time-consuming, expensive, and requires healthcare experts for sample collection and analysis. Late diagnosis of these diseases significantly impacts the quality of life for patients. Moreover, there is a high chance of death due to the severity of the disease [5].

In recent years, healthcare systems globally have undergone a tremendous transformation, driven by rapid progress in technology, especially wearable sensing devices and Artificial Intelligence (AI). Wearable sensing technologies have emerged as an outstanding tool for continuous, non-invasive health monitoring. AI can quickly process vast amounts of data, analyzing it, recognizing patterns, comparing it with a reference dataset, and identifying health conditions [6]. Hence, AI has been widely used in various fields such as environmental monitoring, healthcare, food, automobiles, electronics, and sports [7]. AI integration in wearable sensing technology leads to the development of technology capable of managing cancer, diabetes, and COVID-19 [4,5,8,9].

In cancer, AI-based wearable biosensors are promising alternatives, enabling real-time detection of biomarkers associated with tumor growth, metabolic changes, and therapeutic efficacy. AI-based wearables enable early cancer diagnosis, continuous monitoring, and enhanced patient compliance. All these can lead to better clinical outcomes [4]. In the case of diabetes, AI-based wearable sensing technologies enable continuous glucose monitoring, offering real-time data on glucose trends. Further, they provide predictive analytics, personalized insulin dosing, and real-time alerts for hypo- or hyperglycemic events [8]. All these enable better glycemic control and reduce patient effort. In the case of COVID-19, AI-based wearable sensing devices emerged as a key technology in pandemic management. They allow continuous monitoring of physiological parameters such as heart rate, oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, and body temperature. By leveraging machine learning models, these devices can detect subtle changes in vital signs that often precede the appearance of COVID-19 symptoms, enabling early detection, remote monitoring, and timely medical interventions while reducing the burden on healthcare systems [10].

Recently, AI-based wearable sensing technologies have made significant progress in the field of healthcare [11,12,13]. The most recent achievements in the field of AI-based wearable sensing technologies include wearable photonic wristbands for cardiorespiratory function analysis and biometric identification [14]. It has potential for non-invasive and regular monitoring. Hybrid AI-based, bio-inspired wearable sensors with AquaSense AI technology are used in multimodal health monitoring and rehabilitation in dynamic environments [15]. Liu et al. [16] We utilized supervised machine learning technology to analyze data from 40 patients’ smartwatches. It demonstrated excellent predictive accuracy for mortality in end-of-life cancer patients, achieving 93%. In another study, Torrente et al. [17] Utilized datasets comprising wearable data from 350 patients and clinical data from 5275 patients, applying multilayer neural network technology for cancer prognosis, risk stratification, and follow-up management. The AI successfully constructed risk profiles of patients.

Despite their vast potential, AI-based wearable sensing devices still face challenges, including sensor accuracy, limitations, data privacy and security concerns, high development costs, interoperability issues, and the need for rigorous clinical validation. However, advancements in materials science, data analytics, cloud computing, and machine learning are rapidly addressing these challenges, paving the way for their integration into everyday clinical practice.

This review comprehensively explores the state-of-the-art advancements in AI-based wearable sensing technologies for the management of cancer, diabetes, and COVID-19. It discusses the various sensing modalities, the role of AI in data interpretation, predictive modeling, and decision support, as well as current challenges and future directions. This work aims to provide an understanding of how AI-based wearable diagnostics are poised to transfer disease management into a more precise, efficient, and patient-centered paradigm.

2. Artificial Intelligence-Based Wearable Sensing Techniques

Traditional diagnostic techniques are time-consuming, inaccurate, unable to detect disease early, not reproducible, and delay treatment significantly due to a vast number of patients waiting and limited infrastructure for diagnosis. All these may lead to patients being put in unnecessary circumstances. A lack of adequate, dependable, and cost-effective identification and real-time supervision restricts the affordability of early diagnosis and therapy [18,19]. The success of diagnosing a disease depends on the ability to detect the disease at an early stage, the accuracy of detection, real-time monitoring, and sensitivity and selectivity. Towards this direction, wearable sensing technology has made significant advancements.

The wearable sensing technology market is an emerging segment of the flexible electronics market, which was valued at $1.5 billion in 2020 and is expected to grow at an annual rate of 10.7% through 2030, significantly impacting global health in unprecedented ways. Wearables are small electronic devices designed to be worn on the body. Sensors used in wearable technology can be of various types, including electrochemical, colorimetric, optical, and pressure/strain sensors. These sensors can collect multiple types of signals, including physical, chemical, and biochemical signals. Patients can wear devices directly on their skin, driving rapid advancements in wearable technology for human health monitoring and tracking. Wearable sensing technology provides real-time physiological parameters through flexible, user-friendly devices. The results are faster, eliminating the need for a medical expert and enabling more rapid decision-making for timely treatment [20]. The significant challenges associated with wearable sensing technology are processing, analyzing, and predicting, in real time and continuously, the patterns of data collected by wearable sensors across a range of analytes. One of the best technologies for handling massive datasets is AI.

Artificial intelligence is the most strategic and disruptive technology available today. It marks the beginning of a new era of scientific, technological, and industrial revolutions, bringing powerful empowerment that significantly impacts social progress, economic growth, and the creation of the metaverse environment. Significant developments have been made across various areas, including environments, medicine, healthcare, agriculture, and industrial automation, through the application of artificial intelligence (AI) systems.

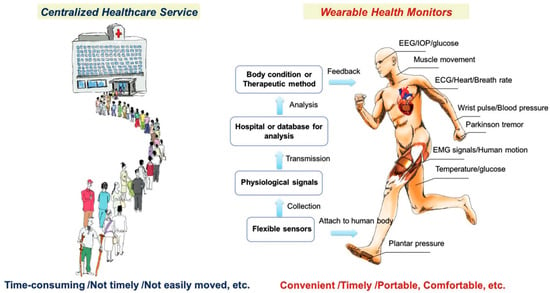

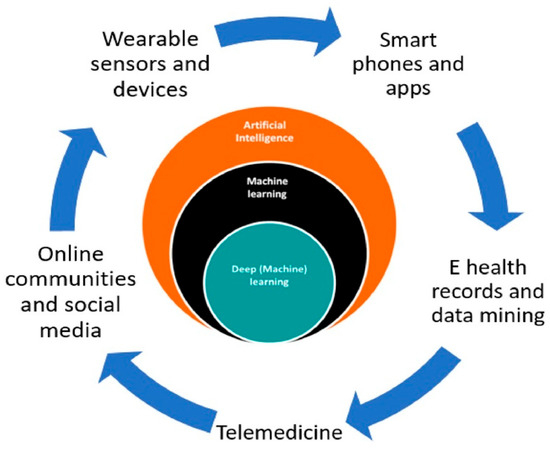

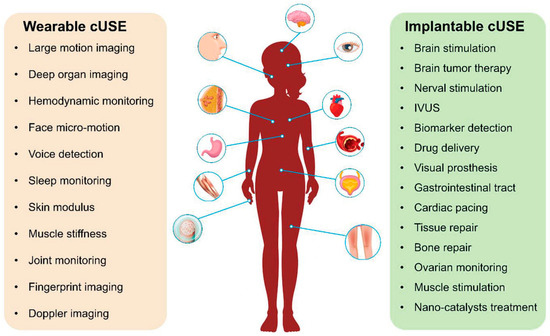

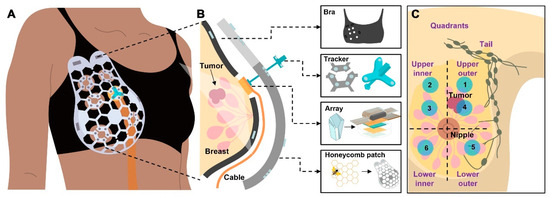

Integrating sensors and devices with AI empowers the development of AI in medical diagnosis and treatment, leveraging emerging sensing technologies. The significant advantages of wearable health sensing technologies over conventional healthcare services are depicted in Figure 1 [21]. Wearable devices can gather data, but machine learning (ML) algorithms address how this data can be used in sensing technology. The patterns derived from the collected data can be provided to healthcare providers to identify trends that can predict patient health outcomes. Suitable care can be provided based on the data analyzed [22]. Different diseases, such as Parkinson’s and multiple sclerosis, can be analyzed and treated using ML algorithms from a database [23]. Crucial information can be collected via these devices, which can facilitate considerable attention to continuous monitoring in non-clinical human health and fitness trials [21]. Saliva, sweat, and tears contain biomarkers found in body fluids, skin odor, breath, and pressure/strain monitoring, which can also be used in human wearable devices [24]. Heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen level, respiratory rate, and temperature are some signals that can be used in AI-powered wearable technology.

Figure 1.

Illustration of differences between conventional healthcare services and wearable healthcare services. Reproduced with permission from ref. [21]. Copyright 2017 Wiley-VCH.

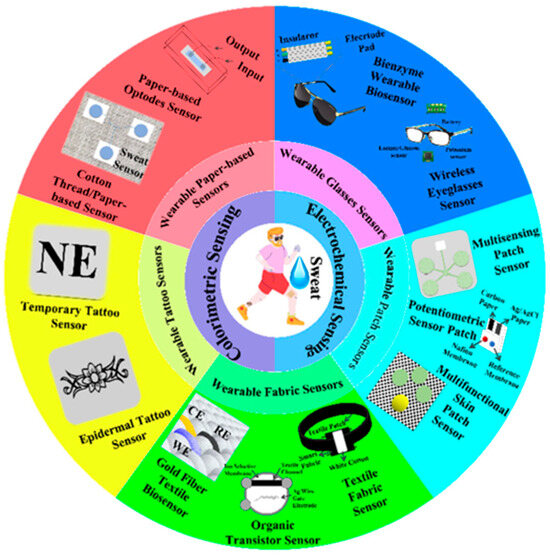

2.1. Artificial Intelligence-Based Wearable Electrochemical Sensing

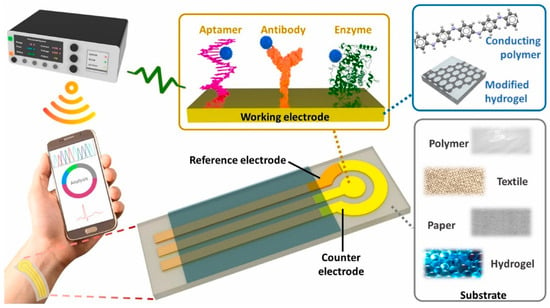

Electrochemical sensors detect analytes by translating biochemical interactions into electrical signals through mechanisms such as amperometry, potentiometry, or conductometry [25]. Electrochemical sensing techniques are widely used for glucose and lactate detection, as well as for biomarkers in sweat, saliva, or interstitial fluid. It further offers minimally invasive and continuous health monitoring [26]. Selectivity among potential biologically interacting chemicals and background noise in clinical samples are two significant biosensor problems that are unsolvable by traditional biosensing techniques. It remains unclear how embedded machine learning can be used to eliminate background interference, which is frequently present in complex matrices such as cerebrospinal fluid. Machine learning can be applied to sensors and devices to improve their ability to distinguish between different responses. Furthermore, incorporating these models into wearable electronics can enhance the use of point-of-care tools, ongoing surveillance, and evaluations of viral mutations [27]. Body fluids often have lower concentrations of biological analytes than blood. Therefore, several biosensor characteristics, including sensitivity, limit of detection, selectivity, and reaction time, must be optimized for consistent, reliable wearable monitoring. Smaller electronics and flexible materials are also necessary for portable point-of-care wearable designs [28]. The fundamental components of all body-worn electrochemical biosensors comprise various components such as (i) a substrate that maintains direct touch with the human body, (ii) electrochemical three-electrode systems compose of working (WE), counter (CE), and reference (RE) electrodes, (iii) immobilized bio-receptors or recognition elements that preferentially interact with the complementary analyte to cause a biochemical shift on the working electrode. The bio-signal is converted into an electrical signal by the transducer, which is then captured, processed, and displayed by (iv) amplifier circuits, (v) electrochemical analyzers, (vi) wireless communication modules, and (vii) software and displayers. The schematic of the wearable electrochemical sensing platform is depicted in Figure 2 [29].

Figure 2.

Schematic of wearable electrochemical biosensors with three electrode systems. Reproduced with permission from ref. [29]. Copyright 2024 Elsevier Open Access.

Sweat, urine, saliva, and tears are electrochemical sensing biomarkers for health monitoring, disease diagnosis, and health monitoring [30]. Impedance, current, potential, and conductance are the electrical signals that an electrochemical sensor generates due to the binding of a bioreceptor with a specific analyte [31]. Electrochemical wearable sensors are extensively utilized owing to their high performance, affordability, small size, and broad range of applications [32]. Electrochemical sensors developed using various nanomaterials, such as metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) [33], transition metal dichalcogenides [34], carbon nanomaterials [35,36], metal-oxides [37], and conducting polymers [38]. It delivers better performance than conventional electrochemical sensors. Electrochemical sensors use enzymes, antibodies, or other molecules as analytes. The barely detectable amount of several metabolites and minerals, including all necessary vitamins and amino acids, was measured using the NutriTrek electrochemical sensors. This biosensor is made up of graphene electrodes. Metabolite-targeted antibody-mimicking molecularly imprinted polymers and redox-sensitive nanoparticles applied for the electrode’s functionalization [32].

Sensors for wearable technology that detect biomarkers at trace levels are adaptable to living tissues and physiological movements, enabling accurate tracking of these biomarkers. Several innovative modification techniques have been devised to increase the sensitivity and flexibility of wearables. Recently, hydrogels have been used extensively as electrode modifiers in wearables owing to their outstanding stretchability and adaptability with human soft tissues [39]. Hydrogel-based wearable electrochemical biosensors do not damage living tissues, enabling extended supervision and high accuracy in identifying the desired biomarkers.

2.2. Artificial Intelligence-Based Wearable Colorimetric Sensing

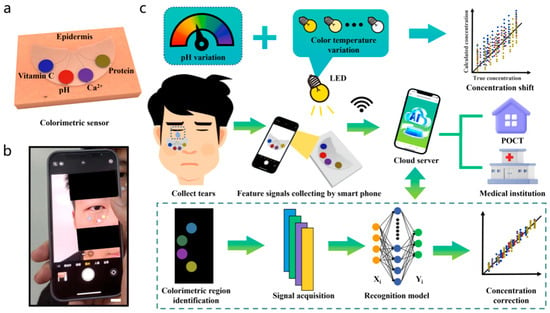

Colorimetric sensing is a robust, straightforward diagnostic technique that relies on visually perceptible color changes in response to physiological and biochemical stimuli. It is generally applied in paper-based test strips and patches. By integrating colorimetric sensing techniques into skin patches, textiles, and contact lenses, real-time monitoring of sweat, saliva, and tears is enabled [40]. Microfluidic colorimetric tear sensors visually represent variations in tear biomarker concentration by colorimetric reactions, in contrast to electrochemical tear sensors. It is crucial to precisely, simultaneously, and quickly identify biomarkers in human tears to monitor eye and overall body health. However, there are difficulties with the colorimetric sensor’s data gathering, interpretation, and sharing, which limit the technology’s usefulness [41]. To overcome the challenges of conventional colorimetric sensing technology, an AI-based cloud server data analysis system (CSDAS) integrated into an electronic device, such as a smartphone, provides color data capture, evaluation, self-adjustment, and visualization. Similarly, Wang et al. developed an AI-assisted wearable microfluidic colorimetric sensor (AI-WMCS). The working mechanism is depicted in Figure 3. Briefly, AI-WMCS is composed of a PDMS microfluidic patch that collects tears and directs them to a channel reservoir containing paper mounted with a chromogenic reagent. Using smartphones, they have captured the data and uploaded it to CSDAS, which quickly identifies colorimetric regions. Based on the results, it detects targeted biomarkers [42]. Further, they have built a CNN-GRU neural network model dataset through collecting a large number of color data for each concentration of biomarkers at different temperatures and pH. The self-learning process builds a calibration curve, thereby further boosting sensor sensitivity. It also helps avoid errors caused by changes in temperature or pH. Hence, such wearable sensing technology will be grateful for monitoring various analytes in tear samples with high sensitivity and selectivity, without error, at different temperatures and pH levels.

Figure 3.

AI-based wearable microfluidic colorimetric sensing technology. (a) microfluidic colorimetric sensing, (b) collection of color data by smartphone camera, and (c) colorimetric sensing of biomarkers in human tears using AI. Reproduced with permission from ref. [42]. Copyright 2024 Springer Nature Open Access.

Paper-based analytical devices (PADs) that use colorimetric sensing and mobile photos have become increasingly popular in various sensing applications [43]. A combination of three image color spaces, RGB, HSV, and LAB, and four machine learning (ML) models: logistic regression, support vector machine (SVM), random forest, and artificial neural network (ANN) for their precision in predicting analyte concentrations. It is also further demonstrated that using the right models and color spaces together can be a powerful, quick, and low-cost method for field testing on many samples on colorimetric PADs. Cui et al. also reported an AI-assisted colorimetric biosensor for smartphones that detects harmful germs quickly and accurately in a visible manner [44]. Hyaluronic acid (HA) hydrogel loaded with β-galactosidase (β-gal) and loaded with β-D-galactopyranoside (CPRG) serves as the bioreactor and signal generator in the biosensor. Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria can be recognized by the biosensor, which can produce a report in less than 60 min with an ultra-low LoD of 10 CFU/mL [44].

Colorimetric tear-based sensors face challenges in reproducibility and precision. However, it can achieve quantitative accuracy by using standard color reference charts and digital color calibration, enabling consistent mapping of color intensity to accurately detect analyte concentration. Image processing algorithms integrated with smartphones and spectrometers reduce human error in color interpretation. Machine learning can enhance detection sensitivity by mitigating lighting variability, user handling, and background interference. Microfluidic channels equipped with advanced tear sensors may enable precise control over sample volume and reaction kinetics, thereby enhancing reproducibility. Quantitative tear sensor validation using gold-standard clinical assays can ensure accuracy in real-world use.

2.3. Artificial Intelligence-Based Wearable Chemical Sensing

Chemical sensing involves detecting target analytes, such as electrolytes, metabolites, and gases, in biofluids like sweat, saliva, and interstitial fluid using selective chemical recognition elements. It offers a physiological status and disease progression [45]. Chemical sensing based on nanomaterials is among the most popular sensors for analyte detection. Conductive inorganic nanomaterials, such as metal and carbon nanomaterials conjugated with ligands or functional groups, are commonly used in construction applications for sensors. Chemiresistor sensing behavior is influenced by two main mechanisms: (a) a three-dimensional swelling and/or aggregation of the film, which alters electrical resistance by changing the interparticle tunneling distance for charge transport to/from the conductive core upon analyte exposure; (b) a boost in the organic matrix’s permittivity, which decreases potential barriers between organic cores [46,47]. One challenge in creating wearables with chemical sensors for health monitoring is detecting and quantifying the targeted analyte. For example, ammonia (NH3) is present at 0.5–2 ppm in human exhaled breath.

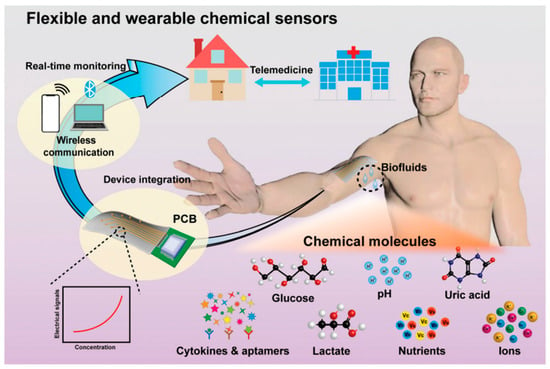

The concentration of biomarkers is also crucial to monitor for diagnosis. A higher concentration of biomarkers may suggest kidney or liver problems, whereas a lower concentration may suggest asthma symptoms [48]. Furthermore, not every disease has a known biomarker. Therefore, appropriate ML algorithms are being used to enhance the effectiveness of sensors in evaluating large volumes of acquired data, thereby sending timely notifications to achieve the central purpose of smart health supervising technology. The schematic of AI-based wearable chemical sensors for the detection of chemical molecules such as pH levels, glucose, lactate, uric acid, ion levels, cytokines, nutrients, and other biomarkers is depicted in Figure 4 [49].

Figure 4.

AI-based wearable chemical sensors. Reproduced with permission from ref. [49]. Copyright 2022 The Royal Society of Chemistry.

2.4. Artificial Intelligence-Based Wearable Optical Sensing

Optical sensing techniques rely on light–matter interactions, such as absorption, reflection, fluorescence, or scattering, to non-invasively analyze physiological parameters, including heart rate, oxygen saturation, glucose levels, and tissue perfusion [50]. Optical sensors are often integrated into smart watches, patches, and textile devices. Usually, they are user-friendly health monitoring devices. In recent decades, human beings have witnessed the profound impact of photoelectronic sensing technology on all aspects of human civilization, including massive data, cloud servers, closed-loop systems, intelligent IoT gateways, AI, blockchain, and metaverse. Functional optoelectronic devices made from various materials, including semiconductors, are a crucial component of the AI optoelectronic sensing method. A necessary part of electronic systems, the optoelectronic display (a display) projects text, pictures, and video data for easily understood visualization that supports human cognition. The use of wearable optical smart devices for real-time biomarker detection is growing. Future wearable technologies will rely heavily on optics and photonics to perform highly sensitive measurements of factors that would otherwise go undetected, providing valuable information about our environment and health. The increasing use of optical wearable technologies, such as glucose, blood pressure, and heart rate monitors, makes personalized medicine a reality by allowing users to create complex, multidimensional physiological and environmental data [51]. The functions of different kinds of optoelectronic sensors are often closely tied to any breakthroughs in AI optoelectronic sensing technology. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is concerned with finding solutions to problems involving machines that can see (word and image recognition), hear (machine translation, speech recognition, etc.), think (human–machine interface), and speech (human–machine communication, speech synthesis, etc.). These are the most pressing issues where AI is currently being integrated. Optoelectronic sensing technology is often used to address these issues. As the AI era develops, optoelectronic wearables are being incorporated into an increasing number of gadgets and products. Compact, digital, and intelligent sensors are becoming increasingly common and are revolutionizing our way of life. Photoelectric sensors, for example, translate an optical signal into an electrical signal.

Machine translation, speech recognition, picture and word recognition, and human–machine communication are the top challenges AI is currently addressing, and AI is focused on tackling these issues. An AI-based Optoelectronic detection system is frequently used to address these issues. AI optoelectronic sensing technology relies heavily on functional optoelectronic devices, which are made of a range of materials such as semiconductors, organic optoelectronic materials, and 2D materials [52]. The role of different kinds of optoelectronic sensors is often closely tied to advancements in AI optoelectronic sensing technology. The optoelectronic effect results from light shining on certain materials; electrons convert photon energy, triggering an electrical response [53].

2.5. Artificial Intelligence-Based Wearable Pressure/Strain Sensing

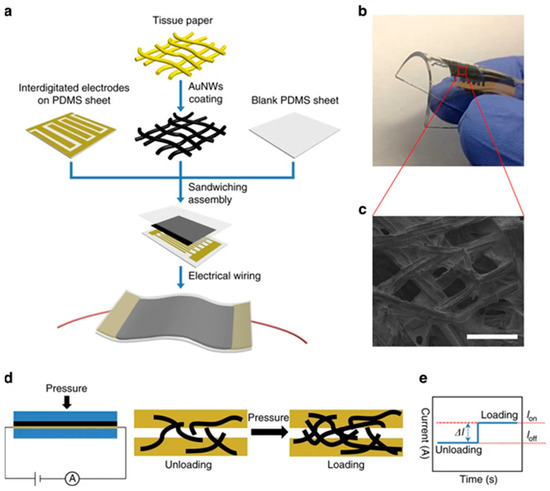

Due to their numerous applications in industrial monitoring and personal electronic devices, pressure sensors are appealing options for advancing AI-based wearable sensing technologies. Organic-material-based flexible pressure sensors, which offer the extraordinary benefits of affordability and flexibility, are a rapidly growing field due to their potential applications in wearable sensing technology and artificial intelligence systems. Large-scale movements, such as the motion of human joints, and small-scale pressures and motions, such as a faint touch or heartbeat, are detected by electromechanical sensors. Consequently, they fall within the category of strain and pressure sensors. Under desired force, pressure sensors can generate signals and act via a process known as signal transduction. This key characteristic enables pressure sensors to be successfully used in industrial production, artificial intelligence, and personal electronic devices [54,55]. Recently, the wearable, precise pressure sensor developed using ultrathin AuNW-coated tissue paper is depicted in Figure 5 [56]. They first fabricated AuNWs and coated them on Kimberly-Clark tissue through a dip-coating and drying approach. Then, the AuNW-coated tissue paper is sandwiched between a PDMS sheet and a PDMS-integrated electrode. The SEM image showed uniform deposition of AuNWs. The fabricated device is wearable and bendable. Then they fabricated pressure sensors that change current with loading or unloading. Strain sensors measure changes in capacitance or resistance to transform mechanical deformations into electrical signals [57,58]. Essential parts of e-skins, exceptionally responsive, adaptable, and stretchy pressure detectors, are also considered for wearable health-tracking devices [59]. Pressure sensors have various applications, including hearing aids, e-skin, daily activities, and measuring weight and height.

Figure 5.

The pressure sensor is based on the AuNW-coated tissue paper. (a) flexible sensor fabrication procedure, its (b) photograph exhibiting bendability, (c) SEM of AuNWs coated tissue fibers, (d) sensing mechanism, and (e) changes in current due to loading and unloading. Reproduced with permission from ref. [56]. Copyright 2024 Macmillan Open Access.

Pressure sensors operate via different mechanisms, such as transduction, and there are several methods for converting tactile impulses into electrical signals, including piezo resistance, capacitance, and piezoelectricity [60,61]. Studying artificial intelligence, or human-like intelligence exhibited by computers and software, is crucial for the development of flexible pressure sensors [62]. Artificial intelligence technology has advanced significantly over the last decade. In interactive robots that utilize AI, the high-performance integration of compliant pressure-sensing devices is required. Blood pressure and pulse are continuously recorded to gather basic health data using highly pressure-sensitive sensors [63]. Monitoring blood pressure, heart rate, and pulse is essential for maintaining human health. Wearable smart bracelets have been widely used in recent years to monitor health in real time, attracting considerable attention. A carbon nanotube (CNT)–polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) composite is used to fabricate flexible, biocompatible dry electrodes for long, high-performance wearable electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring devices [64].

3. Artificial Intelligence-Based Wearable Sensing Technology for COVID-19 Management

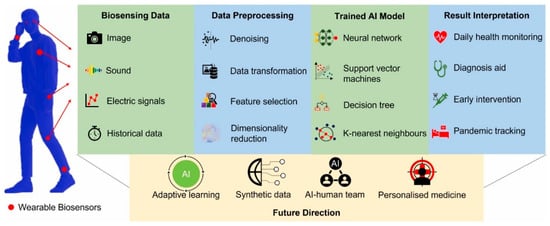

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has significantly transformed healthcare systems worldwide, underscoring the need to adopt various cutting-edge technologies to manage infectious diseases. The rapid spread of the virus and the emergence of its several mutations have made it difficult to diagnose the infection in its early stages and to track patients over time [65]. Conventional healthcare approaches, like hospital-based treatment and diagnostic tests, have not met the volume and urgency of prompt intervention needs. As a result, Artificial Intelligence and wearable sensing technologies have become essential tools for managing and monitoring various health conditions, including pandemics, in real-time [66]. Figure 6 depicts AI in biosensing data collection, processing, training algorithms, and result interpretation, as well as AI applications in future research directions, such as adaptive learning, synthetic data, AI–human team, and personalized medicine [67].

Figure 6.

Current Applications and future research directions of AI algorithms in the biosensing field. Reproduced with permission from ref. [67]. Copyright 2022 Elsevier Open Access.

Wearable health monitoring devices, notably smartwatches and intelligent clothing, can track vital physiological indicators like heart rate, body temperature, and oxygen saturation (SpO2), making them a prominent and indispensable part of the common man’s daily life [68]. When coupled with AI, these devices provide a more dynamic strategy for predictive diagnostics, remote health management, and symptom detection [69]. By evaluating massive amounts of data in real-time, providing individualized health insights, and identifying anomalies early, Artificial Intelligence (AI) significantly improves the effectiveness of wearable sensing systems. In the subsequent subsections, various AI-based wearable device research studies on COVID-19 management have been classified by sensing technology and relevant health parameters to facilitate an in-depth review.

3.1. Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Sensors

Heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV) sensors have been essential in detecting and treating COVID-19. They have enabled real-time, non-invasive monitoring of cardiovascular parameters by measuring myocardial damage. Since the onset of COVID-19, clinical research has shown that the virus affects the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, and alterations in HR and HRV are frequently the first indicators of infection-related physiological stress. Due to this, wearable technology has emerged as a vital and affordable tool for real-time HR monitoring in COVID-19 patients. Using wearable technology, including smartwatches and chest patches with photoplethysmography (PPG) sensors to measure patients’ vital signs continually, numerous studies have investigated the usefulness of these metrics in diagnosing and predicting COVID-19 infection [70]. Preliminary research on early-stage COVID-19 infection indicates that patients often exhibit a higher resting heart rate (RHR) and reduced heart rate variability (HRV) due to dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). Wearable technologies, such as the Apple Watch and Oura Ring, can continuously monitor minute variations in HR and HRV, enabling detection of deviations even before the onset of clinical symptoms, as interpreted by Chatterjee et al. [71]. Wearable devices equipped with piezoresistive sensors that provide real-time, high-accuracy heart rate monitoring are a suitable choice for managing COVID-19 patients. The potential of wearable devices in pre-symptomatic screening was highlighted by Mishra et al. [70], who demonstrated that monitoring changes in resting heart rate and heart rate variability may predict COVID-19 onset up to 9 days before symptoms. They used RHR-Diff and HROS-AD algorithms to monitor RHR, steps, and sleep duration using a smartwatch. They processed 5262 participants, including 32 COVID-positive individuals. This system detected 81% of COVID cases and 88% of cases before the symptoms. The real-time CuSum algorithm exhibited 63% sensitivity. Similar results were observed by Quer et al. [50], who discovered that the accuracy of early COVID-19 detection was significantly increased when HRV and temperature data from wearables were combined [72]. Shahshahani et al. [73], emphasize the accurate positioning of the sensors and created a wearable with an ultrasonic sensor for monitoring heart rate and ECG signals for providing care to COVID-19 patients. Using the Internet of Things, Bhardwaj et al. developed a health monitoring system that combines temperature, SpO2, and heartbeat sensors for remote COVID-19 patient care [74]. Additionally, researchers has demonstrated that HRV can predict illness severity, with lower HRV associated with worse clinical outcomes [68].

AI has improved early detection and predictive modeling capabilities by integrating with HR and HRV sensors. To identify patterns indicative of COVID-19 infection, machine learning techniques, such as neural networks, have been used to analyze HR and HRV data in real-time [66]. According to a study by Riaz et al., AI models evaluating HRV data from wearables identified probable COVID-19 instances with high accuracy [69]. Public health monitoring systems are increasingly integrating AI-driven algorithms that enable scalable, effective identification of COVID-19 in asymptomatic individuals, as reported by Hasasneh et al. [75]. Furthermore, as patients with prolonged COVID-19 frequently experience extended autonomic dysfunction, which can be monitored with wearable technology, continuous monitoring of HR and HRV metrics has been beneficial for managing these patients [76].

3.2. Oxygen Saturation (SpO2) Sensors

Furthermore, oxygen saturation (SpO2) sensors have become a vital tool in managing respiratory disorders, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, as they can non-invasively measure blood oxygen levels by quantifying the fraction of oxygen-saturated hemoglobin. SpO2 levels typically range from 95% to 100% in healthy people [77]. Further studies confirmed that patients with severe COVID-19 often have significantly lower resting SpO2 levels, indicating greater respiratory compromise. Pulse oximeters are the prominent devices for SpO2 monitoring and have become crucial during the pandemic in detecting “silent hypoxia”. It is a condition in which individuals show dangerously low oxygen levels without exhibiting symptoms [78]. Further, Costrada et al. suggested combining continuous SpO2 monitoring with other critical metrics, such as body temperature, to design a compact, low-power wearable SpO2-measuring device [79]. This makes continuous monitoring more feasible, particularly for home-based care. Phillip et al.’s wearable system combines heart rate variability (HRV) and SpO2 tracking, ensuring precision using a commercial wrist-worn pulse oximeter [80]. This device monitors COVID-19 patients recovering at home, identifies significant reductions in SpO2, and treats them immediately. Furthermore, the accuracy and adaptability of SpO2 monitoring have improved significantly with the incorporation of cutting-edge wearables, such as the Oxitone 1000M. With an error rate of less than 3% for SpO2 measurement, the Oxitone 1000M is the first FDA-approved wrist sensor pulse oximetry monitor in history [81]. This gadget offers patients with diverse demands flexibility because it can be worn on different regions of the body, such as the head and chest. These advancements are crucial for enhancing patient comfort and adherence, particularly in situations that require long-term monitoring, such as post-COVID-19 recovery management.

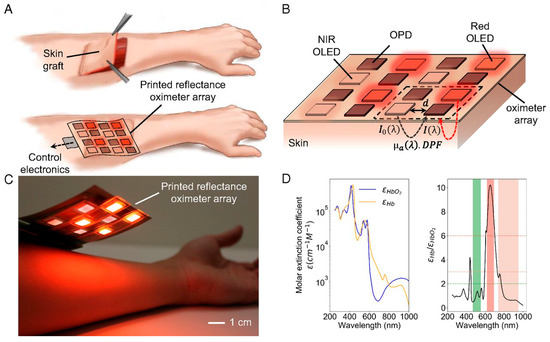

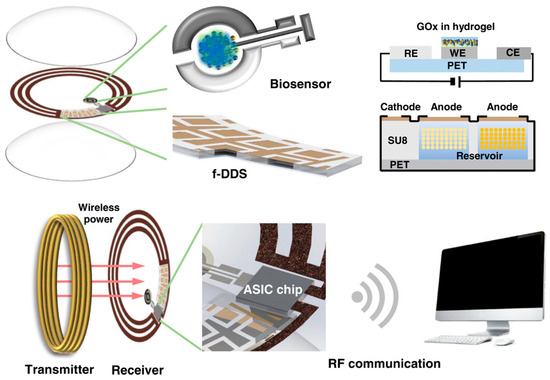

Painless oxygenation mapping efficacy plays a crucial role in post-surgery monitoring of wounds, tissues, and organs. Khan et al. reported A flexible organic reflectance oximeter array (ROA). The schematic and working mechanism are depicted in Figure 7. Briefly, the ROA sensor comprises a Red and NIR OLED array arranged in a checkerboard pattern. The OPD array is placed over the OLED array. OLED acts as a light emitter, and OPD collects diffused reflected light. By placing the ROA on a skin graft after surgery, it can perform oxygenation mapping. The absorption coefficients depend on the specific absorption coefficient and concentration of HbO2, Hb, and DPF, which are the differential pathlength factors [82]. A device for monitoring blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) was designed using organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) and organic photodiodes (OPDs), integrated into organic photoplethysmography (PPG) biosensor systems fabricated on flexible polymeric substrates. This device provides efficient, conformal human–machine interfaces that enable long-term monitoring of biochemical signals. Healthcare professionals can now remotely monitor patients using this device’s compact size, easily measurable features, and support for the Internet of Things (IoT). Similarly, Sarkar and Assaad [83]. Utilize photoplethysmography (PPG) and light spectroscopy to design a reflective mode polarized imaging-based PPG to measure non-contact heart rate and SpO2. They customized an image sensor with wire-grid polarizers that detects phase information from backscattered light.

Figure 7.

Illustration and mechanism of the printed reflectance oximeter array (ROA). (A) ROA using process, (B) ROA configuration, (C) picture of ROA over a person’s forearm, and (D) the molar extinction coefficients of HbO2, Hb, and their ratio. Reproduced with permission from ref. [82]. Copyright 2018 PNAS Open Access.

3.3. Temperature Sensors

The frequent presentation of fever as a primary sign of COVID-19 has made temperature sensing indispensable for its management. Real-time body temperature monitoring has been made possible by wearable, non-contact temperature sensors, such as thermistors and infrared (IR) sensors. These sensors provide a non-invasive method of early fever detection. In public places like airports and hospitals, infrared-based detectors that detect radiation emitted by the human body are frequently used for screening people; however, their accuracy can be affected by temperature and proximity to the skin [84]. New developments in infrared (IR) and IoT-based wearables, such as those created by Ahmed et al. [85], combine cloud technologies with continuous temperature monitoring to enhance real-time data availability and healthcare response. Wearable sensors based on thermistors have become increasingly common in remote healthcare settings. Devices like the iThermonitor have continuously monitored fever in COVID-19 patients to facilitate remote patient care. These devices broadcast real-time data to telemedicine systems [86]. Flexible thermistor sensors have also been incorporated into intelligent textiles to improve patient comfort during long-term monitoring [87]. Known for their remarkable mechanical and electrical capabilities, graphene-based conductive materials are being integrated into flexible sensors. The latest developments in graphene-based flexible sensors emphasize their electrical and thermal conductivity, tensile strength, and novel sensing techniques for temperature, gas, and strain detection [88]. Additionally, it investigates novel fabrication techniques that improve sensor performance. These devices use thin, flexible materials that mold to the skin to continuously capture data [89].

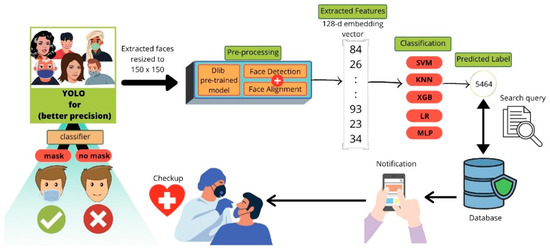

RFID-based temperature sensors have become valuable for non-contact monitoring in hospital settings. By integrating RFID with hospital management systems, they reduce the risk of cross-infection by remotely collecting and transferring temperature data for multiple COVID-19 patients [90]. AI integration has substantially improved the accuracy and usefulness of temperature sensors. The goal of the research conducted by Al-Humairi et al. is to create an artificial intelligence-powered smart helmet that can adapt to changing conditions, using thermal (Adafruit) and Pi (speed sensor) module cameras with embedded sensors [91]. It focuses on facial detection and real-time body temperature, both of which are calibrated using AI algorithms. These aspects are integrated into the system to provide adequate health monitoring. To identify potential COVID-19 cases in large crowds, Barnawi et al. developed an IoT-UAV-based system that analyzes thermal images using onboard thermal sensors. The thermal images recorded by the thermal camera were used to identify potential people in the pictures who may have COVID-19 based on the temperature recorded. Further, they integrated a face mask detection approach to determine whether a person is wearing a face mask. The workflow schematic of the designed COVID-19 notification system using face recognition is depicted in Figure 8. The schemes’ performance evaluation is performed using various machine learning and deep learning classifiers. It achieved an average accuracy of 99.5% across different performance metrics, strengthening its practical implications [92]. It employs a hybrid face recognition technique to detect and identify people with elevated body temperatures in real time. This technique improves the effectiveness of crowd monitoring for detecting COVID-19. The investigation conducted by Khaloufi et al. uses deep learning and smartphone-embedded MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems) sensors to make a preliminary COVID-19 diagnosis [93]. The proposed system extracts health-related features for early disease detection using a cutting-edge deep learning framework. It provides an easy-to-integrate, deployable smartphone screening solution that enables effective monitoring.

Figure 8.

The flow chart of face mask identification and COVID-19 notification. Reproduced with permission from ref. [92]. Copyright 2021 Elsevier.

3.4. Respiratory Rate Sensors

Respiration rate sensors have become essential for combating COVID-19, as the virus has severely affected the respiratory system. Monitoring is vital to preventing the development of severe complications like acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [94]. Abnormally high respiratory rates are a precondition for respiratory distress in patients. As a result, numerous technical developments have been made to ensure precise and instantaneous monitoring of respiration rates [95]. Wearable devices are among the most commonly used technologies for respiratory rate monitoring, particularly for COVID-19 patients who require continuous monitoring. A study by Troyee et al. designed a wearable device that measures respiratory rate with great precision using piezoelectric sensors [96]. Logistic regression is also used to perform binary classification between people with respiratory problems and those without. This system is ideal for real-time monitoring in clinical and residential settings. Wearable breast bands and chest bands have also been incorporated with fiber-optic sensors. The highly sensitive monitoring of chest wall movements, made possible by fiber optics, enables the early detection of respiratory failure [97].

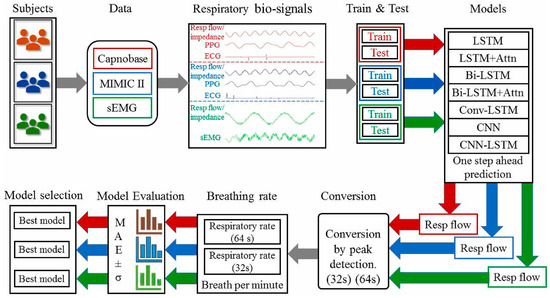

To facilitate caregivers with reduced risk of infection, a contactless device using infrared thermography has been designed by Jha et al. for respiration rate monitoring that can identify temperature changes associated with breathing [98]. This approach is highly accurate in controlled settings; however, external factors, such as ambient temperature, can affect its accuracy. Furthermore, radar-based technologies, such as the one proposed by Purnomo et al., use frequency-modulated continuous wave (FMCW) radar to track respiratory movements. This provides a non-invasive method of detecting minute chest motions, even under challenging circumstances [99]. Data analytics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence have improved respiratory rate monitoring. Kumar et al. presented convolutional neural networks (CNNs), a deep learning model, to interpret respiratory sensor data and enhance the detection of abnormal breathing patterns associated with COVID-19. The step-by-step process of detection and processing of the respiratory rate is depicted in Figure 9 [100]. They used data collected from contact-based sensors, ECG, PPG, and sEMG from different samples. ECG and PPG signals are vascular signals collected from blood vessel activity, whereas sEMG signals are collected from muscle activity. Datasets Capnobase and MIMIC-II include respiratory flow signals alongside PPG and ECG signals. In contrast, the sEMG dataset includes respiratory flow data alongside EMG during breathing and resting periods. The framework used PPG, ECG, respiratory flow, and EMG signals. The data is then split into test and training sets. A training set helps develop a model, whereas a test set helps evaluate it. They used deep learning models such as LSTM, LSTM + Attn, Bi-LSTM, Bi-LSTM + Attn, ConvLSTM, CNN, and CNN-LSTM. LSTM exhibited the best for one of the datasets, and Bi + LSTM showed the best for 2 of 3 datasets [100].

Figure 9.

Flowchart of respiratory rate evaluation and prediction. Reproduced with permission from ref. [100]. Copyright 2022 Elsevier.

The study conducted by Cannata et al. for respiration rate monitoring classifies X-ray images using sophisticated artificial intelligence algorithms to diagnose COVID-19 [101]. It utilizes the Vision Transformer and transfer learning on pre-trained convolutional neural networks (InceptionV3, ResNet50, Xception) to reduce computational complexity and enhance detection accuracy. This approach provides an automated, effective way to identify COVID-19 infections. Rohmetra et al. stated that these cutting-edge AI algorithms for data analytics ensure that medical professionals can react promptly to the first indications of respiratory trouble [102].

Telemedicine platforms incorporated with respiratory rate sensors have become prominent for remote patient monitoring. Palanisamy et al. have presented a cloud-based remote platform for monitoring respiration rate that collects data from wearable sensors. These systems utilize Bluetooth- and Zigbee-capable devices that transmit real-time data to the cloud, where machine learning algorithms analyze it to identify indicators of respiratory distress. This technology has decreased in-person visits, and COVID-19 patients receive continuous care [103]. Furthermore, respiratory rate sensors are integrated into commercial devices like Fitbit and Apple Watch to provide at-home monitoring [104]. These devices are valuable tools for individuals with mild to moderate COVID-19 symptoms. They offer basic respiratory monitoring capabilities outside clinical settings, though they primarily rely on photoplethysmography (PPG) to estimate respiratory rate. They are also widely available and easy to use.

3.5. Multi-Sensor Devices

AI-enhanced multi-sensor devices that provide continuous tracking and early symptom detection play a significant role in managing COVID-19. These devices combine data from several sensors, including temperature, heart rate, SpO2, and respiration rate [105]. AI algorithms use data to identify early infection symptoms and predict disease severity. The artificial intelligence (AI) models improve COVID-19 diagnosis accuracy and reliability by integrating physiological data from multiple sources, minimizing the likelihood of false negative results [106]. Wearable devices that leverage AI-based multi-sensor systems for real-time monitoring are among the significant advancements in this field. The use of AI models in conjunction with multi-sensor wearables that incorporate temperature, heart rate, and SpO2 sensors to efficiently anticipate COVID-19 symptoms before they worsen [107]. Similarly, Shanker et al. evaluated temperature and breathing rate data in wearable multi-sensor systems using deep learning networks to identify anomalies early in COVID-19 patients [108]. Various AI-based wearable sensing devices for COVID management and their features, including type of wearable device, type of AI, target analyte, limit of detection, detection range, selectivity, specificity, pros and cons, are summarized in Table 1.

AI is also essential for identifying “silent hypoxia”, a crucial sign in severe COVID-19 cases. Multi-sensor devices that combine infrared and photoplethysmography (PPG) can track heart rate and oxygen saturation. These readings are analyzed by AI algorithms, which then produce real-time notifications for medical intervention. Furthermore, Yi et al. provided evidence that cloud-based AI systems can gather information from wearable multi-sensor devices across demographics, facilitating effective large-scale COVID-19 monitoring [109]. AI-driven multi-sensor systems help manage long-term COVID and identify active infections. Zimmerling and Chen tracked the virus’s long-term impacts and provided individualized insights on patient recovery by integrating respiratory data and heart rate variability (HRV) into AI algorithms [110]. Despite the enormous potential of multi-sensor systems, several key issues, including interoperability, noise, and sensor accuracy, remain under investigation.

Table 1.

Summary of literature related to various AI-based wearable sensing technologies for COVID-19 management.

Table 1.

Summary of literature related to various AI-based wearable sensing technologies for COVID-19 management.

| Type of Wearable Sensor | AI/Algorithm Used | Target Analyte (Intended) | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Detection Range | Selectivity | Specificity (Reported) | Pros | Cons | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smartwatch/fitness tracker | Signal-processing + online detection algorithm; anomaly detection | Pre-symptomatic physiological signature of infection (COVID-19) | N/A | Human HR/activity dynamic range | Detects physiological deviation but not pathogen-specific | 63% pre-symptomatic detection in the cohort; 81% had alterations | Non-invasive, real-time, widely deployed, population scale | Not pathogen-specific; confounded by exercise/stress; device heterogeneity | [47] |

| Smartwatch + smartphone app (DETECT) | Multivariate classifier combining sensor metrics + symptoms (ML/statistical) | Distinguish symptomatic COVID+ vs. symptomatic COVID− | N/A | N/A | Improved discrimination when fusing sensor + symptom modalities | AUC = 0.80 (sensor+symptoms) vs. 0.71 (symptoms only) | Large cohort (30,529); scalable app-based collection | Self-report biases; device/platform heterogeneity | [50] |

| Biosensing wearable network (iPREDICT)—conceptual framework | Anomaly detection; Graph Neural Networks (GNNs); spatiotemporal models; federated learning (proposed) | Early outbreak/pandemic risk indicators | Conceptual; depends on underlying sensors | Population/spatiotemporal scale | Aims to improve selectivity via cross-user correlation and contextual data | Framework-level; specificity depends on model thresholds and context | Proactive outbreak detection: leverages crowd-sensed data and graph models | Requires standardized data, privacy-preserving infra, and broad adoption | [69] |

| Wearable biosensors + ICT (systematic review) | Surveyed ML/DL across studies (SVM, RF, CNN, ensemble, anomaly detection) | Patient deterioration, infection monitoring, remote triage | Varies by device/study; review-level | Device-dependent | Improved with multimodal fusion | Varied across included studies; heterogeneous reporting | Comprehensive mapping of ICT + wearable solutions; identifies effective strategies | Heterogeneous methods and metrics; variable evidence quality | [71] |

| IoT-based smart health monitoring system (prototype) | Rule-based alerts; proposed ML integration | Physiological indicators of infection/severity | Reported relative errors vs. commercial devices: HR 2.89%, Temp 3.03%, SpO2 1.05% | Clinical vital sign ranges | Good for gross physiological changes; limited pathogen specificity | Not explicitly quantified | Low-cost, suitable for rural deployment; cloud storage for longitudinal tracking | Requires connectivity; privacy/security and calibration concerns | [74] |

| Smartwatch + explainable unsupervised learning pipeline | Unsupervised clustering; validated with supervised classifiers; GPT-3 for interpretation | Physiological anomaly clusters indicating infection (COVID-19) | N/A (clustering/classification task) | N/A | Clusters capture anomalies but need clinical labels for disease specificity | Supervised validation: accuracy 0.884 ± 0.005; precision 0.80 ± 0.112; recall 0.817 ± 0.037 | Reduces reliance on labeled data; explainability aids clinician trust | LLM interpretation may introduce noise; cohort-dependent | [75] |

| 24 h Holter ECG (clinical-grade HRV monitoring) | Statistical analysis (no ML reported) | Autonomic dysregulation in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome (PCS) | N/A | 24 h monitoring window | HRV is sensitive to autonomic changes but not disease-specific | PCS patients showed significant HRV alterations vs. controls (after correction) | An objective clinical biomarker for autonomic dysfunction | Requires clinical equipment and interpretation; not a consumer wearable | [76] |

| Non-contact infrared thermometers (NCIT)—screening | ROC analysis and thresholding (no AI) | Fever detection as a proxy for infection | NCIT resolution ~0.1 °C | Skin temperatures ~30–40 °C | The neck site had the highest accuracy among the sites tested | Triple neck detection sensitivity up to 0.998; accuracy reduced at ambient < 18 °C | Fast, contactless, scalable for mass screening | Many infections are afebrile; ambient and site dependence; not pathogen-specific | [84] |

| IoT + Cloud + AI framework review for self-monitoring (5G enabled) | Survey of ML/AI approaches, cloud/edge analytics architectures | Physiological indicators associated with COVID-19/self-diagnosis | Device-dependent (review) | Varies with sensors | Multi-modal fusion is proposed to increase selectivity | Not experimentally quantified (review) | Comprehensive technology stack view; emphasizes low-cost cloud analytics and 5G benefits | Privacy, data security, deployment, and standardization challenges | [85] |

| UAV-mounted thermal camera (aerial thermal imaging) | Computer vision/deep learning classifiers for face detection, mask detection, temperature anomaly detection (hybrid ML/DL) | Fever screening/identify potentially febrile individuals in crowds (COVID-19 triage) | Thermal camera resolution dependent; not reported as concentration LOD (temperature resolution typical ~0.1 °C) | Up to drone operational range; system table: drone payload 2 kg, flight time 30–35 min (per paper) | Detects elevated skin temperature; not pathogen-specific; can include false positives (environmental effects) | Overall average accuracy reported ~99.5% for the proposed pipeline in test scenarios (paper reports high accuracy for detection tasks) | Rapid, contactless mass screening; can cover large crowds; includes mask detection | Skin temp not always reflective of core temp; environmental/ambient effects; cannot confirm infection | [90] |

| Smartphone onboard sensors (conceptual/app) | Deep learning frameworks (CNN/RNN/hybrid DL) for classification; proposed DL pipeline | Preliminary diagnosis/screening for COVID-19 | N/A (classification task); performance metric: reported overall accuracy ~79% using smartphone sensors | User-device range (onboard sensors) | Depending on features used; cough/audio may be confounded with other respiratory illnesses | Not universally reported; overall accuracy 79% reported in this study | Widely available, low-cost, quick-deployable screening without medical tests | Requires labeled data, user compliance, false positives/negatives, and variability across devices | [93] |

| Contact piezoelectric sensor (and ultrasonic non-contact) for respiration | Logistic regression for classification of respiratory disease from collected vitals (simple ML) | Respiratory rate monitoring and screening for respiratory disease | N/A (physiological metric); device accuracy reported: overall device accuracy 96.58% for RR measurement | Respiratory rates in the typical human range (~5–40 bpm)—device validated on patients | Detects abnormal respiratory rate patterns; not disease-specific | Logistic regression classifier achieved 88% accuracy (5-fold CV) for respiratory disease detection | Low cost, accurate RR measurement, suitable for continuous monitoring | Contact sensor required; placement sensitivity (best positions vary by BMI); may be uncomfortable for long-term use | [96] |

| FMCW radar (non-contact) | Stacked ensemble ML models (ensemble of MLR, DT, RF, SVM, XGB, LGBM, CatBoost, MLP) and proposed Neural Stacked Ensemble Model (NSEM) | Classify respiratory behavior/detect abnormal breathing patterns (COVID-19 supervision) | Not concentration-based; radar sensitivity to chest micro-displacement; not reported as LOD | Room-scale; can detect multiple subjects and AoA separation | Can separate multiple objects and breathing characteristics; robust to lighting/privacy issues compared to the camera | The best model (NSEM) achieved 97.1% accuracy in experiments | Non-contact, privacy-preserving, can monitor multiple subjects simultaneously, with high accuracy reported | Requires RF hardware, signal interference, and may need careful calibration and line-of-sight | [99] |

| Wearable biosignal sensors (ECG, PPG, sEMG) for RR prediction | Deep learning: LSTM, Bi-LSTM, Attention LSTM, CNN-LSTM, ConvLSTM; Bi-LSTM with Bahdanau attention best | Accurate respiratory rate prediction from biosignals | N/A (physiological regression task); MAE reported as performance metric (best MAE 0.24 ± 0.03 for PPG + ECG dataset) | Depends on dataset; models evaluated on clinical/public datasets | Model differentiates RR patterns effectively; sensor-dependent noise affects selectivity | Performance reported as MAE; no binary specificity since regression task | High accuracy RR prediction with deep models; works across ECG/PPG/sEMG data | Require quality biosignals; model complexity and computational needs; window length affects performance | [100] |

| Imaging (chest X-ray) based diagnostic tool (hospital imaging) | Deep learning: transfer learning with CNNs (InceptionV3, ResNet50, Xception) and Vision Transformer (ViT) | Automatic COVID-19 detection and classification from CXR images | N/A (imaging classification) | Image-level classification, dependent on dataset quality and radiographic features | ViT showed superior ability to distinguish four classes vs. CNNs | Vision Transformer achieved a test accuracy of 99.3% (reported), outperforming ResNet50 (85.58%) in their experiments | High diagnostic accuracy reported (on their dataset); rapid automated triage potential | Requires clinical imaging equipment; dataset biases and limited generalizability; high accuracy may not generalize to diverse populations | [101] |

| Various wearables + smartphone/camera-based approaches (review) | Survey of ML/DL methods: CNN, RNN, image/signal processing, anomaly detection, explainable AI | Remote monitoring of vital signs for COVID-19 screening and monitoring | Varies by modality; review summarizes methods rather than specific LODs | Device-dependent; many methods are suitable for smartphone deployment | Varies; methods may struggle to be disease-specific, but useful for anomaly detection | Varied across studies; review discusses strengths and limitations (no single specificity value) | Enables remote, low-cost monitoring using ubiquitous devices; discusses practical deployment challenges | Heterogeneous literature; privacy and data-quality concerns; not yet clinical-grade across the board | [102] |

| Wearable IoT sensors for remote patient activity monitoring (multi-sensor wearables) | Proposed CNN-UUGRU deep model (convolution + updated gated recurrent units) for activity recognition | Activity recognition, remote patient monitoring, and detection of confinement breaches for quarantined patients | N/A (activity recognition/vital signs) | Wearable/device dependent; remote cloud connectivity via IoT | High for activity classes (model accuracy reported) | Reported performance: accuracy 97.7%, precision 96.8%, F-measure 97.75% on evaluated datasets | Integrated IoT-stack with high activity classification accuracy; cloud alerts and GPS tracking enable quarantine monitoring | Privacy concerns, connectivity needs, sensor calibration, and battery constraints | [103] |

4. Artificial Intelligence-Based Wearable Sensing Technology for Diabetes Management

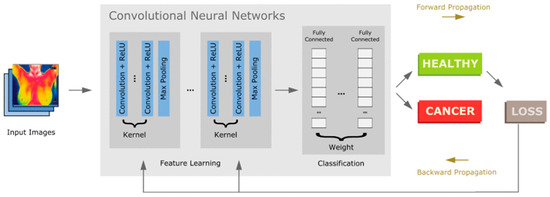

Diabetes, which affects millions of people worldwide, is a chronic metabolic disease marked by the body’s failure to control blood glucose levels. This can be attributed to either insulin resistance (Type 2) or insufficient insulin production (Type 1) [111]. As a vital tool for managing diabetes, Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) systems designed with the help of wearable sensing technology allow real-time surveillance of blood sugar levels with little need for manual intervention [112]. Based on electrochemical, optical, microneedle, and innovative sweat-based sensing technologies, etc., these devices offer a more sophisticated and practical substitute for conventional finger-stick glucose monitoring methods [113]. Their accuracy and user comfort have increased drastically, providing a more comprehensive approach to diabetes management. Wearable technology also progressively incorporates sensors for other physiological information, such as heart rate and physical movement [114]. Integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) with these wearable devices to perform complex data evaluation and forecasting models has revolutionized diabetes management (Figure 10) [115]. AI algorithms, such as ML and DL, process large volumes of real-time data from wearables to forecast glucose trends, identify abnormalities, and propose personalized insulin dosage [116]. Closed-loop insulin administration systems have also benefited from the deployment of AI-driven models, which automate insulin adjustments and enhance glycemic control with minimal human intervention. This review highlights recent progress in wearable sensing technologies using artificial intelligence (AI) for managing diabetes, emphasizing sensing technology in subsequent subsections [117].

Figure 10.

Use of AI in diabetes care. Reproduced with permission from ref. [115]. Copyright 2020 Elsevier.

4.1. Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) Devices

4.1.1. Electrochemical Sensors

Electrochemical sensors are crucial for continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems due to their high sensitivity and real-time glucose detection. These sensors measure glucose oxidation in interstitial fluid and produce electrical signals proportional to the amount of glucose present [112]. The simplicity and comfort of continuous monitoring for diabetes patients have improved over time as these sensors have become smaller and integrated into wearable devices [113]. However, the sheer amount of data these sensors generate makes real-time analysis and interpretation more difficult. To address this, Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven control algorithms, such as machine learning (ML) and reinforcement learning models, have been integrated with electrochemical sensors to process data and predict glucose trends. These AI models provide sophisticated insights into glucose changes that may not be evident in conventional monitoring systems, assisting in the early diagnosis of hypo- and hyperglycemic episodes and helping track insulin changes [118]. AI’s ability to estimate glucose levels up to 60 min in advance has dramatically improved the accuracy and therapeutic utility of these systems, giving diabetes patients more effective and individualized management options [119]. This integration enables automated, data-driven decision-making for more efficient glucose management, representing a significant advancement in diabetes treatment.

There is a challenge in determining which AI technique best mitigates the confounding effects of temperature drift in wearable electrochemical glucose sensors [120]. Calibration models using ML, such as support vector regression and random forests, are widely used to model the nonlinear relationship between sensor output and temperature variation. The second approach is a deep learning method, such as convolutional neural networks and recurrent neural networks, which can understand the temporal patterns of glucose signals in conjunction with temperature fluctuations, thereby enhancing robustness in dynamic real-world environments. This is a sensor fusion framework that integrates AI techniques to combine multisensory data, helping to disentangle the effect of temperature using multimodal neural networks. Adaptive algorithms, such as online learning and adaptive filtering, enable real-time correction of temperature drift by continuously updating the model with new data from the individual wearer. Among all, Deep learning, especially CNN-LSTM hybrid models with sensor fusion, has great potential in recent studies to mitigate the temperature drift confounding effect while maintaining real-time performance [121].

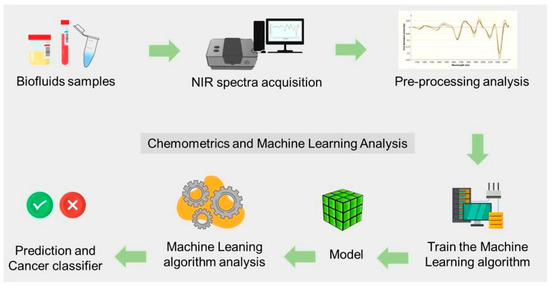

4.1.2. Optical Sensors

Optical sensors can measure glucose levels by detecting how light is scattered or absorbed by biological tissues. This capability has made them a viable and prominent non-invasive tool for glucose monitoring. Techniques like fluorescence, Raman spectroscopy, and near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy serve as the building blocks of optical sensors. These techniques can minimize the discomfort associated with invasive methods like standard finger-prick testing [122]. These sensors can provide continuous monitoring by evaluating variations in the optical characteristics of skin or interstitial fluids and correlating them with glucose concentrations. However, the primary concern in using optical sensors is reducing interference from other physiological factors, such as temperature, tissue heterogeneity, and motion artifacts [123].

Here, artificial intelligence (AI) models can also be incorporated to handle the complex data generated by optical sensors and improve their performance. Artificial intelligence models aid in noise reduction and interference compensation, providing more precise glucose measurements. For instance, light sources spanning 18 wavelengths from 410 to 940 nm can improve glucose detection sensitivity and selectivity in aqueous solutions. Errors arising from variations in blood and tissue components across individuals can be mitigated by using multiple wavelength measurements. Five ML techniques are investigated for glucose prediction: regression analysis, k-nearest neighbors, decision trees, and neural networks [124]. Pal et al. proposed a blood glucose sensing model that uses a digital camera, a magnetic field, and records speckle patterns from a finger using a laser [125]. ML and DNN techniques are used to preprocess and evaluate recorded video patterns to identify glucose levels. AI models trained on optical sensor data have been used to accurately estimate glucose levels, even in the presence of tissue scattering and skin pigmentation [126]. AI has shown promise in real-time glucose monitoring and in minimizing the need for invasive procedures when combined with wearable optical sensors. This connection enables more accurate, continuous, and user-friendly glucose management, a significant advancement in the field.

4.1.3. Microneedle Sensors

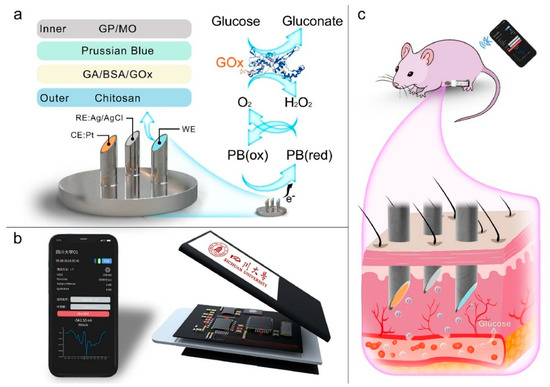

Microneedle sensors can access interstitial fluid just beneath the skin’s surface without causing discomfort, and their minimally invasive nature has made them a popular choice for continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). Compared to conventional finger-prick methods, these sensors use microscopic needles to puncture the skin, offering constant and real-time glucose monitoring with greater precision [127]. Microneedles are perfect for wearable applications in managing diabetes since they are frequently combined with electrochemical sensing technologies to measure glucose concentrations in interstitial fluid. Li et al. reported a microneedle-based CGM platform developed using a three-electrode electrochemical biosensor and evaluated the sensing efficacy (Figure 11). Incorporating PB, Gox, and chitosan enables the formation of a stable 3D network that exhibits a sensing range of 0.25 to 35 mM, high sensitivity, and anti-interference properties. They have performed in vivo analysis using the diabetes rate to evaluate therapeutic efficacy. More interestingly, it provided accurate real-time glucose, which is further consistent with commercial meters [128]. A biomimetic microneedle theragnostic platform (MNTP) uses microneedle arrays for simultaneous glucose and ion monitoring and on-demand skin penetration to provide accurate diabetes treatment [129]. Utilizing hybrid carbon nanomaterials to functionalize the epidermal sensor allowed for the detection of oxygen-rich interstitial fluid. In an innovative approach to manufacturing microneedle sensors, 3D printing, microfabrication, electrodeposition, and enzyme immobilization were employed to create a PMMA-based microneedle detector for glucose. In vitro evaluation revealed that the sensor had an excellent selectivity and repeatability, a linear range of 1.5 to 14 mM, a sensitivity of 1.51 µA mM−1, and a detection limit of 0.35 mM [130].

Figure 11.

(a) Wearable microneedle-based sensing system for CGM, (b) illustration of profile structure and program control interface, and (c) concept of wearable CGM system on a Sprague Dawley rat. Reproduced with permission from ref. [128]. Copyright 2023 Elsevier.

Microneedle CGM patches can maintain sterility for a week of wear because they are generally fabricated under aseptic conditions and packaged in sterile, single-use formats, thereby reducing the risk of contamination. Biocompatible polymers, hydrogels, and coatings infused with antibacterial agents further reduced microbial colonization during prolonged skin contact. The interface between the microneedle and the skin forms shallow, self-sealing microchannels after removal, reducing the risk of infection. Further CGM patches are integrated with protective adhesive films, which act as a barrier against dust, sweat, and external microbial entry [131]. Week-long sterility and safety have been validated in several pilot and clinical studies, with low irritation and infection rates observed. Hence, CGM patches are ideal for long-term applications.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has improved data processing and predictive accuracy, greatly expanding the potential of microneedle sensors. He et al. discussed how analyzing the continuous data produced by microneedle sensors enables machine learning (ML) models, such as support vector machines and neural networks, to predict glucose trends and aid in the more efficient management of glucose fluctuations [132]. To maximize fluid collection, the physical parameters of microneedle (MN) designs were optimized by integrating machine learning (ML) models with finite element methods (FEMs) [133]. ML algorithms were trained on FEM simulations with varying geometric parameters, and the best predictions were obtained with decision tree regression (DTR). Machine learning techniques can optimize MN designs for targeted drug delivery and point-of-care diagnostics in wearable devices. The accuracy of glucose readings can be further improved by using AI-based algorithms that can adjust for changes in the sensor environment, such as skin condition and body movement [134]. Diabetes-related wounds are difficult to heal because of inflammation and poor tissue regeneration. Xue et al. discovered that a wound-healing drug, Trichostatin A (TSA), targets histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) for diabetes treatment using AI-assisted bioinformatics [135]. A novel, minimally invasive therapeutic strategy was developed using a microneedle (MN)-mediated patch loaded with TSA, which reduced inflammation, improved tissue regeneration, and suppressed HDAC4.

4.2. AI-Driven Insulin Pumps and Closed-Loop Systems

Artificial intelligence (AI)-driven insulin pumps and closed-loop devices, also known as artificial pancreas, have become groundbreaking tools for improving diabetes care. These systems use intelligent algorithms, such as machine learning (ML) and deep learning, to autonomously adjust insulin delivery via insulin pumps based on real-time data from continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). Advanced control algorithms, including fuzzy logic, model predictive control (MPC), and proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controllers, provide the foundation of these systems’ technological architecture to balance current insulin dosage with historical trends [136]. Zhou and Isaacs stated that, based on the patient’s physiological feedback, these algorithms aim to keep blood sugar levels between 70 and 180 mg/dL, avoiding hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia [137]. According to the study conducted by Guzman Gomez et al., Artificial Intelligence techniques can further improve these control strategies, providing insulin more precisely and promptly while reducing the risk of hypo- and hyperglycemia [138].

Maintaining a balance between safety and efficiency is a significant challenge in AI-driven insulin delivery. To provide a solution for this, Zarkogianni et al. designed and evaluated a personalized insulin infusion advisory system (IIAS) that uses insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors to provide real-time insulin rate estimations for patients with Type 1 diabetes [139]. Recurrent neural network and compartmental models are utilized along with a tailored glucose-insulin metabolism model and a nonlinear model-predictive controller (NMPC). The predictions were made based on patient data, including food consumption, glucose readings, and insulin infusion rates. Similarly, Ahmed et al. conducted a comprehensive study to ensure that AI systems must deliver the right amount of insulin to the patient, considering his/her food and metabolic activities like stress, physical activity, food consumption, etc. [140]. Basal insulin and high-concentration pre-meal injections are insufficient for adequate blood glucose management in diabetes because they may not provide long-term stability. Adaptive learning techniques also allow the system to learn from prior glucose trends, improving predicted accuracy and lowering the frequency of sensor recalibration [141]. A system that combines a pumping module, glucose sensor, and decision unit has recently been designed [142]. The decision unit utilizes artificial intelligence (AI) to analyze glucose data and determine the optimal insulin dosage. This method prolongs the time that blood glucose levels stay within a healthy range and improves insulin delivery. Researchers have investigated using Reinforcement Learning (RL) supported by the Markov Decision Process (MDP) model to modify insulin administration tactics in response to real-time glucose level feedback [143].

Although rule-based algorithms were the mainstay of early iterations of these systems, more recent developments have brought hybrid AI-driven models that integrate data-driven and control-theoretic methodologies. Boughton and Hovorka studied how these hybrid models better control blood glucose levels over time [144]. Additionally, AI-powered devices are increasingly customized, personalizing insulin administration protocols according to each user’s unique physiological requirements and lifestyle choices [145]. Nimri et al. conducted a non-inferiority test on an extensive dataset of 108 participants over six months to compare the insulin prescription levels of medical practitioners using traditional clinical methods with those prescribed by an automatic AI system [146]. The results reveal that predictions from AI-based glucose monitoring and insulin prediction systems are as accurate as those from medical experts, while being faster and more economical.

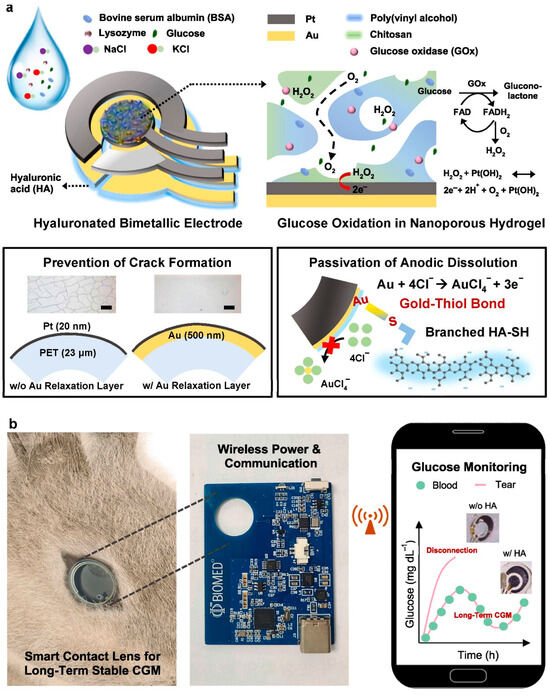

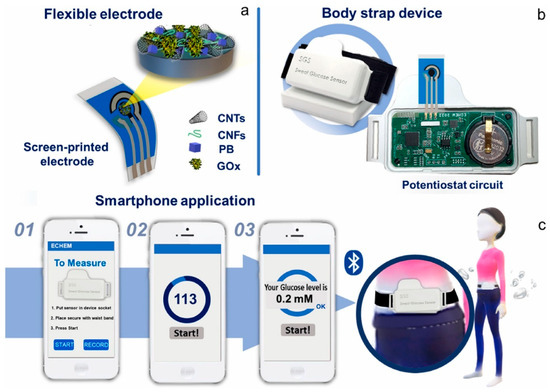

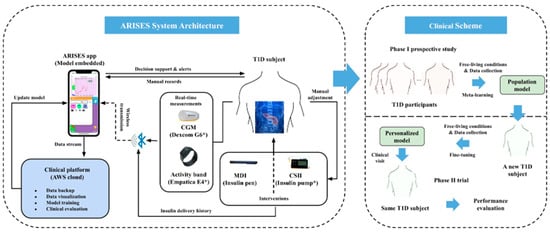

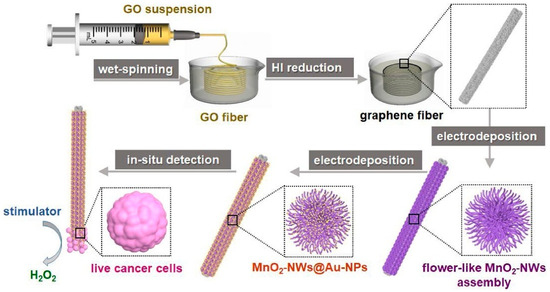

4.3. Non-Invasive Glucose Monitoring Wearables

4.3.1. Smart Contact Lenses