Abstract

WS2 is considered as a potential anode material for lithium ion batteries (LIBs) with superior theoretical capacity and stable structure with two-dimensional which facilitates to the transportation and storage of lithium ion. Nevertheless, the commercial recognition of WS2 has been impeded by the intrinsic properties of WS2, including poor electrical conductivity and large volume expansion. Herein, a seaweed-liked WS2/reduced graphene oxide (rGO) composites has been fabricated through a procedure involving the self-assembling of WO42−, hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium ion with graphene oxide (GO) and the subsequent thermal treatment. The WS2/rGO nanocomposite exhibited the outstanding electrochemical property with a stable and remarkable capacity (507.7 mAh·g−1) at 1.0 A·g−1 even after 1000 cycles. This advanced electrochemical property is due to its seaweed-liked feature which can bring in plentiful active sites, ameliorate the stresses arisen from volume variations and increase charge transfer rate.

1. Introduction

Lithium ion battery, as a green energy storage device, is the alternative to current batteries most potential (for example, shows advanced energy density, which is about 4 times higher than nickel-cadmium battery and 1.6 times higher than nickel-metal hydride battery) [1,2,3]. However, the ever-lasting need for powerful energy storage equipment, especially for emerging industry (such as electric vehicle and smart grid), has spurred the evolution of the electrode material for LIBs [4,5,6,7]. Recently, tremendous researches are focus on transition metal oxides (TMOs) attributing to their highly specific capacity (almost 3 or 4 times higher than graphite). Nonetheless, the practical application of TMOs are hampered by their intrinsic property (e.g., poor ion conductivity, and low structural stability origin from the conversion reaction mechanism). To address these issues, two-dimensional (2D) inorganic transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) have been introduced, ascribing to their relative high electronic conductivity, superior specific capacity, marvelous structural stability and environment benignity [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

Tungsten disulfide (WS2), as an important component of the TMDs, has drawn extensive attention owing to its superior theoretical capacity and abundant reserves [16,17,18,19,20]. WS2 is a hexagonal crystal system, and the underlying crystal structure of WS2 is composed of three atomic layers connected by van der Waals forces, stacked in the manner of S–W–S, providing the channel for Li+ ions to be embedded and released [21,22,23,24,25]. Moreover, the large spacing of the WS2 adjacent layers is more favorable to the transport and the accumulation of lithium ions, which leads to the fact that the geometric structure of the WS2 can be preserved without an apparent variation during the corresponding electrochemical reaction [26,27,28]. However, the large-scale commercial application of WS2 has been impeded by the intrinsic properties of WS2, including weak electrical conductivity and volume expansion [12,29,30]. The intrinsic properties can cause the collapse of geometrical configuration in cycling processes, followed by a dramatic performance reduction. In this case, enhancing the conductivity of WS2 and improving structural stability are a potential approach to overcome these obstacles. Several reports have showed that combining WS2 with the conductive matrix is a promising means to enhance the electrochemical properties, as well as a potential way to alleviate the large volume expansion of the active material [28,31,32,33]. Graphene is a perfect compound material with advanced electrochemical characteristics and mechanical strength [34]. Li et al. successfully fabricated multi-slices WS2/rGO nanocomposites by hydrothermal synthesis method [35]. The composite could exhibit a capacity of ~337 mAh·g−1 at 2.0 A·g−1 after 100 cycles. In addition, multitudinous other various conductive matrix materials have been applied to address these limitations. Ren et al. reported the foam structure WS2/single-wall carbon nanotube nanocomposites delivers a reversible capacity (~688 mAh·g−1) for 1000 cycles at 0.1 A·g−1 [36]. Wu et al. designed WS2/carbon nanofiber composites via combining hydrothermal and electrospinning methods with the presence of a capacity of 545 mAh·g−1 at 0.5 A·g−1 [37], while Kong et al. prepared WS2/graphitic carbon nanotubes through combining electrospinning and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) with 570 mAh·g−1 at 0.2 A·g−1 [38]. Unfortunately, a variety of WS2 nanocomposites above have been synthesized for LIBs, either the preparation method is too complicated for large-scale production, or the long preparation period increases the production cost, or the cycling performance is slightly insufficient, hindering their further commercial application.

Herein, for higher energy density and a high-rate capability, we synthesized a seaweed-liked WS2/rGO nanocomposites through a procedure involving the self-assembling of WO42−, hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium ion with GO and the subsequent thermal treatment. The seaweed-liked WS2/rGO nanocomposites, as an anode material, displays an ultralong cycling life and striking rate performance, it can provide a prominent reversible capacity of 507.7 mAh·g−1 after 1000 cycles at 1.0 A·g−1 and a specific capacity of 108 mAh·g−1 at 20.0 A·g−1, which shows a highly attractive as the electrode to next-generation LIBs.

2. Experimental

2.1. Preparation of Graphene Oxide (GO)

GO was prepared from flake graphite (325 meshes) via a modified Hummers’ method. Under the condition of ice bath, NaNO3 (2.5 g) and flake graphite (2.0 g) were added to 180 mL of concentrated sulphuric acid (H2SO4, 95%) while stirring. Subsequently, KMnO4 (15.0 g) was slowly added, and the temperature of the reaction in the process was controlled below 20 °C. Then, 180 mL of DI water was introduced after reaction for 24 h. Next, raise the temperature to 98 °C and maintain for ~1 h. When the temperature dropped to 70 °C, 80 mL of hydrogen peroxide aqueous solution (H2O2, 35%) was added. Continue to stir for 1 h after cooling to room temperature. Ultimately, the acquired GO was centrifuged several times with 5% dilute hydrochloric acid and DI water, and then freeze-dried for preservation. The resistance of the deionized (DI) water used for the reaction was ~18 MΩ cm−1.

2.2. Synthesis of WS2/rGO Composites

To fabricate WS2/rGO composite, GO (40 mg), cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) (0.364 g), ammonium tungstate (0.5 g) and thiourea (1.83 g) were subsequently dispersed in 25 mL DI water with violent stirring. After freeze-dried, the resulting mixture was heated to 500 °C and kept in an Ar flowing tube furnace for 3 h. The synthesis approach for bare WS2 were the same as the above composite without the addition of GO.

2.3. Characterization Measurements

The obtained samples were analyzed by the scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi S5500, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan); the field emission transmission electron microscope (FETEM, JEM-2100F, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan); the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Escalab 250, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, United States) with a focused monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486 eV); X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns (Rigaku MiniFlex 600 X-ray diffractometer, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) with Cu Kα (λKα = 1.5406 Å) as the radiation source, and laser confocal Raman microspectroscopy (Raman, Horiba Jobin-Yvon LabRAM HR800, Horiba Jobin-Yvon, Paris, France). The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were measured on a CHI660E (CH instrument, Shanghai, China) in the frequency range of 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz, with an amplitude of 10 mV.

2.4. Electrochemical Measurements

The resulting sample is assembled into the CR 2025 coin-type half cells in a glove box at Ar atmosphere for electrochemical performance testing. 1 M LiPF6 solution (EC/EMC/DEC = 1:1:1 v/v) as the electrolyte, Celgard 2400 membrane as the separator and the lithium metal as the counter/reference electrode. The working electrodes were made of the resulting sample (80 wt%), acetylene black (10 wt%) and polyvinylidene fluoride (10 wt%) dissolved in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone to form slurry. The obtained homogeneous paste were pasted on Cu foils with a thickness of ~20 µm and dried in vacuum oven at 90 °C for 12 h and then cut into a wafer with a diameter of 12 mm, each wafer possesses about 1.9 mg active material. The cyclic voltammetry (CV) (CHI660E electrochemical workstation) and galvanostatic charge/discharge cycles (Arbin battery test system, current rate = (0.1 − 20.0 A·g−1)) were tested within the 3.0–0.01 V voltage range. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were measured on a CHI660E in the frequency range of 105 Hz to 10−2 Hz, with an amplitude of 10 mV.

3. Results and Discussion

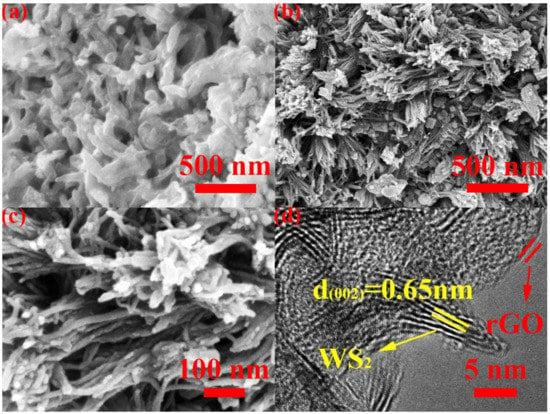

The morphological characteristics of the two prepared nanomaterials were researched by observing the images of SEM and TEM (Figure 1). The WS2/rGO nanocomposites was fabricated with a procedure involving the self-assembling of WO42−, CTA+ with GO and the subsequent thermal treatment. The obtained WS2/rGO sample exhibits a uniform seaweed-liked morphology in Figure 1b. There is no sight of nanosheets from rGO. Since CTA+ facilitates to reduce the innate charge incompatibility between negatively charged GO and WO42−, ascribing to the electrostatic interaction, there is no conspicuous interfacial structure between rGO and WS2 (synthesis from the subsequent calcination with the presence of thiourea) in Figure 1c. The high magnification of WS2/rGO can be seen in Figure 1c. In contrast, the bare WS2 without GO just form short rod shape in Figure 1a, which illustrates that GO plays an indispensable role in the production of the seaweed-liked nanostructures. To further investigate the structure of WS2/rGO nanocomposite, Figure 1d displays the TEM images of WS2/rGO nanocomposite. The spacing of the clear lattice fringe is 0.65 nm, corresponding to the d-spacing of (002) plane of the c-axis of hexagonal WS2. The thin rGO is attached to the surface of the few layer WS2 nanosheets as shown in Figure 1d. The added GO is reduced to rGO during the calcining phase and formed stable seaweed-liked composite with WS2, not only providing an efficient conductive path for electron transport, but also avoiding a structure collapse of the electrode, owing to the huge volume expansion. Which is consistent with the XRD patterns shown in Figure 2a.

Figure 1.

(a) SEM images of bare WS2 and (b–c) SEM, (d) TEM images of WS2/rGO composites.

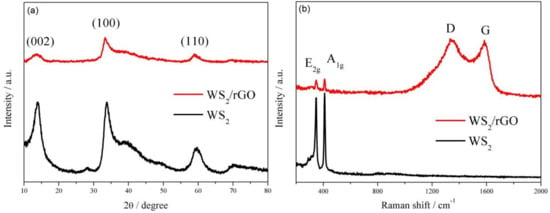

Figure 2.

(a) XRD patterns and (b) Raman spectra of WS2 and WS2/rGO.

Figure 2a shows X-ray diffraction patterns of the two samples. All conspicuous diffraction peaks (at 2θ = 13.52°, 33.81°, 59.28°) can be easily linked to the 2H-WS2 without the existence of other phases or impurities, demonstrating the high purity of the obtained WS2 (Figure 2a). Furthermore, a few-layered structure of WS2 can be certified by the presence of (002), (100) and (110) reflections. Since the existence of the rGO diminishes the intensity of incoming and reflected X-ray light, the reduction of the diffraction peaks intensity of WS2/rGO can be clearly observed. The similar attenuation also can be observed in Raman spectra (Figure 2b), where the intensity of the characteristic Raman signature of WS2 (located at 346 and 409 cm−1 correspond to the E2g and A1g modes, respectively) in WS2/rGO shows obviously weaker than that of bare WS2. Moreover, Raman spectrum of WS2/rGO shown in Figure 2b also can certify the existence of rGO attributing the emergence of two prominent peaks D (relate to the symmetric k-point phonon pattern of A1g) and G (ascribing to the E2g phonon of C sp2 atoms).

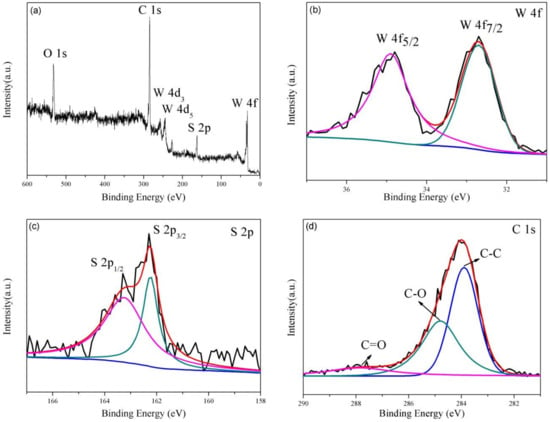

XPS analyses were applied to identify the chemical composition of the WS2/rGO sample (Figure 3). The presence of W, S, C and O (originate from the unreduced oxygeneous groups of the rGO) in the WS2/rGO composite is certified by survey spectrum shown in Figure 3a. The distribution of the W 4f peaks on WS2 can be testified through two obviously peaks at 34.9 and 32.7 eV (in Figure 3b), corresponding to the W 4f5/2 and W 4f7/2 spin peaks of WS2, respectively. Meanwhile, the high-resolution spectrum of S (Figure 3c) illustrates two characteristic peaks at 162.0 and 163.0 eV that stemmed from the S2− typical of WS2. The high-resolution spectral of C 1s is presented in Figure 3d, where three different components (in 287.8, 284.8 and 284.1 eV) can be observed, corresponding to the C=O, C–O and C–C bonds of rGO, respectively, which in line with the previously reports [39,40,41].

Figure 3.

(a) broad XPS scan spectrum of WS2/rGO composites; the high-resolution spectrum of (b) W 4f; (c) S 2p; (d) C 1s.

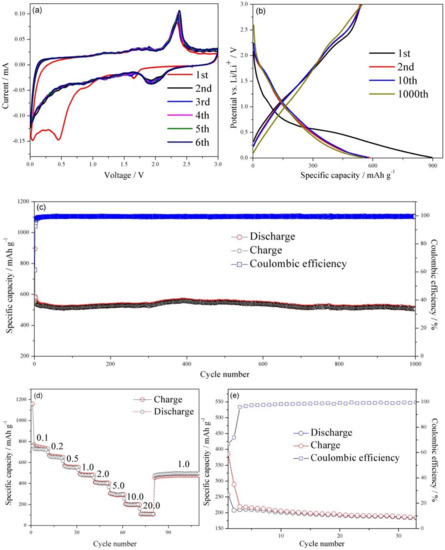

The electrochemical process of the WS2/rGO composite electrode in charge-discharge cycling was investigated by the initial six cycles cyclic voltammogram (CV) at 0.01 mV·s−1 in Figure 4a. As shown in Figure 4a, the reduction peak at 1.65 V and oxidation peak at 2.35 V can be observed clearly in the first cycle, which was caused by the insertion/extraction reaction of Li+ in the WS2 interlayer space (WS2 + xLi+ + xe− ↔ LixWS2). Another obvious reduction peak can be seen at 0.45 V that arises from the reduction of WS2 (WS2 + 4Li+ + 4e− → W + 2Li2S), and accompanying by non-aqueous electrolyte decomposition and adverse reactions between Li+ and the residual oxygen-containing functional groups. In the second cycle onwards, reduction peaks at 1.65 and 0.45 V no longer can be observed, meanwhile, a new reaction at 1.75–2.18 V can be visualized. This change could be accounted by the production of gel-liked solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) film [42]. Moreover, those cyclic voltammograms were nearly fully superimposable, indicating the excellent reversibility and cycle stability of the WS2/rGO nanocomposites.

Figure 4.

(a) CV curves of the WS2/rGO composite at 0.01 mV·s−1 in the 0.01 to 3.0 V voltage window. (b) Charge/discharge voltage profiles of WS2/rGO at 1.0 A·g−1. (c) The cycle stabilities of the WS2/rGO at 1.0 A·g−1. (d) The rate capacities of WS2/rGO at 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0, 10.0 and 20.0 A·g−1. (e) The cycle stabilities of the bare WS2 at 1.0 A·g−1.

Figure 4b illustrates the charge-discharge curves of WS2/rGO material at 1st, 2nd, 100th and 1000th cycles under 1.0 A·g−1, respectively. The voltage plateau appears in the first discharge curve around 0.55 V, which may be ascribed to WS2 being reduced to metallic W at the same time that Li2O is generated. The first discharge/charge capacity of the WS2/rGO composites comes to 895.8 mAh·g−1 and 546.3 mAh·g−1, causing a high premier Coulombic efficiency of 60.9%. The nonreversible loss of the first cycle is probably ascribed to the adverse reactions between Li+ and the residual oxygen-containing functional groups on the WS2/rGO composites, and the formation of SEI film during lithium ion intercalation process [43,44,45,46,47], which makes the following discharge curves exhibit a totally different voltage plateau at 2.0 V, in conformity to the aforementioned CV curves, suggesting the superior electrochemical property of the WS2/rGO composites. This was also explained by the similarity between the 2nd, the 10th and the 1000th charge/discharge profiles of the WS2/rGO (Figure 4b) and their near coulombic efficiency after the first several cycles in Figure 4c. Furthermore, the WS2/rGO composites electrodes present a marvelous cycle stability at 1.0 A·g−1 (Figure 4c). Even after 1000th cycle, the WS2/rGO composites electrode still have a charge capacities of 505.6 mAh·g−1 and a discharge capacities of 507.7 mAh·g−1. Compared with the capacities of another WS2-based anode materials report previously, the stable reversible capacity of the WS2/rGO composites is much higher, suggesting the superiority of using the WS2/rGO composites as an anode material for LIBs [12].

To further study the advanced electrochemical characteristics of the WS2/rGO composites electrode, rate capability also has been evaluated (Figure 4d). As the current density increases from 0.1 to 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 5.0 A·g−1, the different discharged capacities of 720, 650, 554, 479, 402 and 300 mAh·g−1 are delivered, respectively. The reversible capacities of the WS2/rGO electrode with 199 and 108 mAh·g−1 still can be achieved while the current density increases to 10.0 and 20.0 A·g−1, respectively. Significantly, after returning to 1.0 A·g−1, the capacity of WS2/rGO composites immediately recovered to 508.5 mAh−1, demonstrating the excellent electrode conductivity and fast Li+ diffusion.

For in-depth reveal the role of rGO in the WS2/rGO electrode, the circulation property of the bare WS2 electrode has been assessed. The capacity of bare WS2 is only ~200 mAh·g−1 in Figure 4e, far lower than that of the WS2/rGO composites. In addition, the bare WS2 electrode suffers a sustaining capacity fading after the first few cycles, manifesting the prominent cycling property of the WS2/rGO on the side. The result is consistent with the conclusion of the morphology of the two materials in Figure 1a and Figure 1b. The rGO is formed stable seaweed-liked composite with WS2, avoiding a structure collapse of the electrode owing to the huge volume expansion and providing a highly conductive path for electron transport. Besides, the seaweed-liked structure materials will provide much more active sites, ameliorate the stresses arisen from volume variations and increase charge transfer rate to further improve lithium storage capacity and ionic conductivity [48].

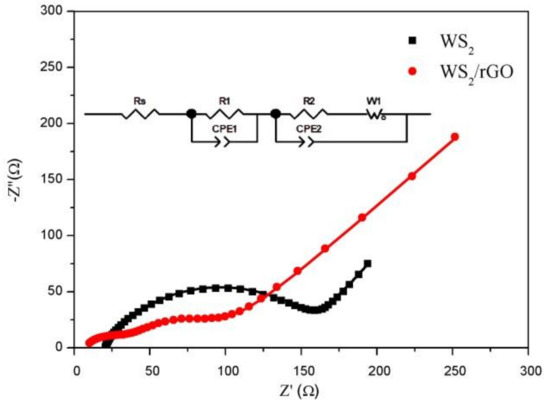

An EIS measurement was conducted for two samples to further research the electrochemical behavior in Figure 5. The tests in this survey were achieved after 100 cycles. Generally, the impedance spectra was composed of semicircle and a skew line, which were related to the charge transfer resistance and ion diffusion process, respectively [46]. It can be seen that the semicircle size of the WS2/rGO is much smaller than that of the bare WS2. The Rs and Rc of the bare WS2 and the WS2/rGO composites can be extracted by using equivalent circuit shown in the inset of Figure 5, which are 20.9, 116.4, 7.2 and 27.5 Ω, respectively, suggesting the faster charge transfer speed of WS2/rGO. Therefore, the addition of rGO can effectively enhance the conductivity performance of WS2 and greatly decrease charge transfer resistance, which is consistent with the expectation.

Figure 5.

The Nyquist plots of bare WS2 and WS2/rGO composite range from 105 Hz to 10−2 Hz after 100 cycles.

4. Conclusions

In summary, the seaweed-liked WS2/rGO nanocomposites was fabricated by a procedure involving the self-assembling of WO42−, CTA+ with GO and the subsequent thermal treatment. The WS2/rGO material as the anode material for LIBs exhibited ultralong cycling life and striking rate performance with a stable and remarkable capacity of 507.7 mAh·g−1 at 1.0 A·g−1 after 1000 cycles. Furthermore, it was worth nothing that its capacities of 108 mAh·g−1 could still be maintained while the current density increases to 20.0 A·g−1. Noteworthily, after returning to 1.0 A·g−1, the capacity of WS2/rGO composites immediately recovered to 508.5 mAh−1. The superior electrochemical property could depend on the synergy of WO42−, CTA+ and GO. The added GO is reduced to rGO during the calcining phase and formed stable seaweed-liked composite with WS2, not only providing an efficient conductive path for electron transport, but also avoiding a structure collapse of the electrode owing to the huge volume expansion. Moreover, the seaweed-liked structure would provide much more active sites, ameliorate the stresses arisen from volume variations and increase charge transfer rate to further improve lithium storage capacity and ionic conductivity. The seaweed-liked WS2/rGO nanocomposites show great promise for other energy storage devices (e.g., sodium-ion battery).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Y. and H.T.; methodology, Y.J. and X.Y.; formal analysis, X.Z., X.D. and W.X.; resources, Y.Z. and X.Y.; data curation, Y.H. and Y.J.; writing-original draft preparation, Y.H. and Y.J.; writing-review & editing, Z.M., Y.J. and X.Y.

Funding

This work was financially supported by National Science Foundation of China (51472034 and 21701115), and Science and technology capacity innovation project (7010902404).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Youn, D.H.; Jo, C.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.S. Ultrafast synthesis of MoS2 or WS2-reduced graphene oxide composites via hybrid microwave annealing for anode materials of lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 295, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Mu, C.; Xiang, J.; Wen, F.; Su, C.; Hao, C.; Hu, W.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Z. Carbon-encapsulated Co3O4@CoO@Co nanocomposites for multifunctional applications in enhanced long-life lithium storage, supercapacitor and oxygen evolution reaction. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 220, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhao, R.; Liu, W.; Zhang, X.; Shen, X.; Li, W.; Diao, G.; Chen, M. In-depth nanocrystallization enhanced Li-ions batteries performance with nitrogen-doped carbon coated Fe3O4 yolk−shell nanocapsules. J. Power Sources 2017, 344, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raccichini, R.; Varzi, A.; Passerini, S.; Scrosati, B. The role of graphene for electrochemical energy storage. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Feng, Z.; Zai, J.; Ma, Z.-F.; Qian, X. Incorporation of Co into MoS2/graphene nanocomposites: One effective way to enhance the cycling stability of Li/Na storage. J. Power Sources 2018, 373, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwieters, T.; Evertz, M.; Mense, M.; Winter, M.; Nowak, S. Lithium loss in the solid electrolyte interphase: Lithium quantification of aged lithium ion battery graphite electrodes by means of laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry and inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy. J. Power Sources 2017, 356, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.H.; Kim, D.S.; Kim, M.; Park, M.S.; Lee, Y.-C.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, I.T.; Hur, J.; Lee, S.G. Investigation of electrochemical performance on carbon supported tin-selenium bimetallic anodes in lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 266, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, R.; Wu, Q.; Li, W.; Shen, C.; Ni, L.; Yan, H.; Diao, G.; Chen, M. Petal-like MoS2 nanosheets space-confined in hollow mesoporous carbon spheres for enhanced lithium storage performance. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 8429–8436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Feng, C.; Chen, X.; Guo, Z. Synthesis and Performance of Tungsten Disulfide/Carbon (WS2/C) Composite as Anode Material. J. Electron. Mater. 2018, 47, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, T.; Li, Z.; Olsen, B.; Mitlin, D. Lithium ion battery applications of molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) nanocomposites. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Tan, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, H. Solution-Processed Two-Dimensional Metal Dichalcogenide-Based Nanomaterials for Energy Storage and Conversion. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 6167–6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Pei, C.; Chen, W.; Feng, L. 2 dimensional WS2 tailored nitrogen-doped carbon nanofiber as a highly pseudocapacitive anode material for lithium-ion battery. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 272, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, S.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, W. MoS2 nanobelts with (002) plane edges-enriched flat surfaces for high-rate sodium and lithium storage. Energy Storage Mater. 2018, 15, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minakshi, M.; Mitchell, D.R.; Baur, C.; Chable, J.; Barlow, A.J.; Fichtner, M.; Banerjee, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Ahuja, R. Phase evolution in calcium molybdate nanoparticles as a function of synthesis temperature and its electrochemical effect on energy storage. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manickam, M.; David, M.; Reddy, M.A.; Barlow, A.J.; Maximilian, F. New insights into the electrochemistry of magnesium molybdate hierarchical architectures for high performance sodium devices. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 13277–13288. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S.; Patil, S.A.; Memon, A.A.; Vikraman, D.; Naqvi, B.A.; Jeong, S.H.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, H.-S.; Jung, J. CuS/WS2 and CuS/MoS2 heterostructures for high performance counter electrodes in dye-sensitized solar cells. Sol. Energy 2018, 171, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.S.; Choudhary, N.; Jung, Y.; Thomas, J. Recent advances in two-dimensional nanomaterials for supercapacitor electrode applications. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.W.; Sadhasivam, T.; Wang, A.Y.; Chen, T.Y.; Lin, J.Y.; Shao, L.D. Ternary Composite Nanosheets with MoS2/WS2/Graphene Heterostructures as High-Performance Cathode Materials for Supercapacitors. ChemElectroChem 2018, 5, 1024–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zhai, C.; Fujitsuka, M.; Majima, T. Noble metal-free near-infrared-driven photocatalyst for hydrogen production based on 2D hybrid of black Phosphorus/WS2. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 221, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Guo, R.; Luo, Y.; Li, F.; Liu, Z.; Meng, L.; Yang, Z.; Luo, H.; Wan, Y. Innovative N-doped graphene-coated WS2 nanosheets on graphene hollow spheres anode with double-sided protective structure for Li-Ion storage. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 290, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Frindt, R. Li-intercalation and exfoliation of WS2. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1996, 57, 1113–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yebka, B.; Julien, C. Studies of lithium intercalation in 3R-WS2. Solid State Ion. 1996, 90, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhowalla, M.; Shin, H.S.; Eda, G.; Li, L.-J.; Loh, K.P.; Zhang, H. The chemistry of two-dimensional layered transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voiry, D.; Yamaguchi, H.; Li, J.; Silva, R.; Alves, D.C.; Fujita, T.; Chen, M.; Asefa, T.; Shenoy, V.B.; Eda, G. Enhanced catalytic activity in strained chemically exfoliated WS2 nanosheets for hydrogen evolution. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Ahluwalia, P. Electronic transport and dielectric properties of low-dimensional structures of layered transition metal dichalcogenides. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 587, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Ma, J.; Li, H.; Zeng, R.; Guo, Z.; Liu, H. Synthesis of molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) for lithium ion battery applications. Mater. Res. Bull. 2009, 44, 1811–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Ji, G.; Ding, B.; Ma, Y.; Qu, B.; Chen, W.; Lee, J.Y. In situ nitrogenated graphene—Few-layer WS2 composites for fast and reversible Li+ storage. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 7890–7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Fu, C.; Niu, C. WS2 nanoflowers on carbon nanotube vines with enhanced electrochemical performances for lithium and sodium-ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 766, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Ding, Z.; Ma, C.; Wu, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, L.; Ivey, D.G.; Wei, W. Hierarchical nanocomposite of hollow N-doped carbon spheres decorated with ultrathin WS2 nanosheets for high-performance lithium-ion battery anode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 18841–18848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.Z.; Ansari, S.A.; Parveen, N.; Cho, M.H.; Song, T. Lithium ion storage ability, supercapacitor electrode performance, and photocatalytic performance of tungsten disulfide nanosheets. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 5859–5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Yang, Z.; Liu, G.; Qiao, Q. Facile synthesis of MoS2/MWNT anode material for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 1921–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ju, Y.; Qiu, H.; Wei, Y.; Liu, B.; Zou, B.; Du, F.; Chen, G. Improved Lithium-Ion and Sodium-Ion Storage Properties from Few-Layered WS2 Nanosheets Embedded in a Mesoporous CMK-3 Matrix. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 7074–7080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Huang, Z.; Wu, G.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, G.; He, C.; Qi, X.; Zhong, J. A novel WS2/NbSe2 vdW heterostructure as an ultrafast charging and discharging anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 17040–17048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, D.K.; Sen, U.K.; Choudhury, D.; Mitra, S.; Sarkar, S.K. Atomic layer deposited MoS2 as a carbon and binder free anode in Li-ion battery. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 146, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yu, K.; Fu, H.; Guo, B.; Lei, X.; Zhu, Z. Multi-slice nanostructured WS2@rGO with enhanced Li-ion battery performance and a comprehensive mechanistic investigation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 29824–29833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, F.; Ren, R.-P.; Lv, Y.-K. Freestanding 3D single-wall carbon nanotubes/WS2 nanosheets foams as ultra-long-life anodes for rechargeable lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 267, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zeng, X.; He, P.; Chen, L.; Wei, W. Flexible WS2@CNFs Membrane Electrode with Outstanding Lithium Storage Performance Derived from Capacitive Behavior. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 5, 1701080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Qiu, X.; Wang, B.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Guo, R.; Gao, Y.; Yang, Q.-H.; Zhi, L. WS2 nanoplates embedded in graphitic carbon nanotubes with excellent electrochemical performance for lithium and sodium storage. Sci. China Mater. 2018, 61, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Jiang, Z.-J.; Maiyalagan, T.; Manthiram, A. Cobalt oxide-coated N-and B-doped graphene hollow spheres as bifunctional electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution reactions. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 5877–5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, R.; Sundaram, M.M. A biopolymer gel-decorated cobalt molybdate nanowafer: Effective graft polymer cross-linked with an organic acid for better energy storage. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 2863–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Yan, X.; Xiao, W.; Tian, M.; Gao, L.; Qu, D.; Tang, H. Co3O4-graphene nanoflowers as anode for advanced lithium ion batteries with enhanced rate capability. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 710, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiva, K.; Matte, H.R.; Rajendra, H.; Bhattacharyya, A.J.; Rao, C. Employing synergistic interactions between few-layer WS2 and reduced graphene oxide to improve lithium storage, cyclability and rate capability of Li-ion batteries. Nano Energy 2013, 2, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuniga, L.; Agubra, V.; Flores, D.; Campos, H.; Villareal, J.; Alcoutlabi, M. Multichannel hollow structure for improved electrochemical performance of TiO2/Carbon composite nanofibers as anodes for lithium ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 686, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agubra, V.A.; Zuniga, L.; Flores, D.; Campos, H.; Villarreal, J.; Alcoutlabi, M. A comparative study on the performance of binary SnO2/NiO/C and Sn/C composite nanofibers as alternative anode materials for lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 224, 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.D.; Zhang, F.; Gan, X.F.; Huang, Q.A.; Tang, W.M. Electrochemical characteristics of amorphous silicon carbide film as a lithium-ion battery anode. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 5189–5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Shao, C.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y.; Wu, Q.H.; Yang, Y. SiC Nanofibers as Long-Life Lithium-Ion Battery Anode Materials. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Yan, X.; Mei, P.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, W.; Tang, H. Electrochemical reconstruction induced high electrochmical performance of Co3O4/reduced graphene oxide for lithium ion batteries. developments in nanostructured anode materials for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 764, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Lin, Z.; Alcoutlabi, M.; Zhang, X. Recent developments in nanostructured anode materials for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 2682–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).