Abstract

Water electrolysis using electricity generated from renewable sources is a promising approach for producing green hydrogen. However, this process requires the development of electrocatalysts that are not only highly active and durable but also low-cost. Considerable efforts are being directed toward discovering and optimizing such materials, and this study contributes to the ongoing research in this area. In this work, three novel LaMnO3 perovskite–graphene oxide hybrids—namely LaMnO3/GO, Ag-doped LaMnO3/GO, and Pd-doped LaMnO3/GO—were synthesized and investigated for their electrocatalytic activity in water electrolysis under strongly alkaline conditions. To the best of our knowledge, these hybrid materials have not been previously reported in the context of electrocatalytic water splitting. Among the electrodes fabricated and tested for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), the one based on a catalyst ink containing Pd-doped LaMnO3/GO mixed with carbon black showed the best performance, achieving a low overpotential of 0.385 V at a current density of −10 mA/cm2. It also demonstrated good stability in the alkaline electrolyte and exhibited a Tafel slope of 0.34 V. These findings highlight the potential of the studied materials as effective and previously unreported electrocatalysts for water splitting.

1. Introduction

In today’s world, fossil fuel reserves are dwindling, the environment is polluted, temperatures are rising, there is overcrowding, and a continuous increase in energy demand. These issues have led to political tensions, as well as a global energy and economic crisis [1]. The scientific community is making substantial efforts to find solutions to these urgent matters by focusing especially on their energy-related aspects [2,3]. The direction in which the research is advancing is towards finding alternatives to using fossil fuels as the main energy source that are also environmentally friendly [4]. Within this context, hydrogen has been singled out in recent decades as a promising energy carrier, having the potential to bring about a new energy infrastructure that is no longer based on the burning of fossil fuels [5]. Among other desirable properties, hydrogen has high gravimetric energy density and combusts without polluting the environment [6]. When generated using only renewable energy sources, it is known as green hydrogen, and water electrolysis is the usual method employed to obtain it [7]. This approach was initially reported in 1789 and involves two half-cell reactions, namely the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) unfolding at the cathode and the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) occurring at the anode [8]. The overall reaction is presented in Equation (1), while Equations (2) and (3) show HER and OER in basic electrolyte solutions [9].

2H2O → 2H2 + O2

4OH− → 2H2O + O2 + 4e−

4H2O + 4e− → 2H2 + 4OH−

The heavy reliance on water and its environmental friendliness make water electrolysis a very advantageous process with the potential to provide a sustainable alternative to the fossil fuel-dependent energy infrastructure. However, while the water splitting reaction can unfold at RT and atmospheric pressure, electrocatalysts are required to efficiently lower the H2 and O2 overpotential values [10]. This places major focus on the synthesis of highly active and long-term stable electrocatalytic materials. Currently, precious metals and precious metal-based materials such as Pt for HER and IrO2 and RuO2 for OER are regarded as the most active electrocatalysts, ensuring low overpotentials even at high current density values [11]. However, noble metals substantially increase the cost of the water electrolysis process, which is already relatively high due to the high electric power consumption [12]. While the latter issue can be addressed using electricity generated using renewable sources (wind power, tidal power, or solar energy), finding a suitable replacement for the noble catalysts has become a daunting task [13]. Furthermore, noble metals are scarce, which is another factor why they cannot be used in large-scale water splitting applications [14]. More affordable and earth-abundant materials are required for electrocatalyst synthesis. Catalysts with low noble metal content, chalcogenides containing transition metals, transition metal oxides, carbides, sulfides, phosphides, nitrides, alkoxides, hydroxides, carbon-supported single-atom catalysts, and other metal-free compounds have been studied regarding their water splitting electrocatalytic properties [9,15,16,17,18]. Oxide-based catalysts, such as ABO3 perovskite oxides, are attractive due to their specific physical–chemical and electronic properties. The flexibility of perovskite oxides allows their substitution at the A and B sites with most known elements, often with a rare-earth metal at the A site and a transition metal at the B site [19]. Furthermore, perovskites can also be doped and used as constituents of hybrid materials. For example, Sfirloaga et al. [20] reported the synthesis of two hybrid structures, namely polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) functionalized with Ag-doped LaMnO3 and Pd-doped LaMnO3, which were subsequently shown to exhibit OER activity in an alkaline environment.

The present study continues the search for materials based on doped ABO3 perovskites with potential application in the field of water electrolysis. Specifically, three LaMnO3 perovskite–graphene oxide hybrids were synthesized and evaluated in terms of their HER electrocatalytic activity in a strong alkaline electrolyte solution. These are undoped LaMnO3/GO (LMG), Ag-doped LaMnO3/GO (LMG-Ag), and Pd-doped LaMnO3/GO (LMG-Pd). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no previously reported studies have investigated LaMnO3/GO hybrids—either doped or undoped—for electrochemical water splitting applications. The results obtained herein, using electrodes modified with catalyst inks containing the hybrid electrocatalysts drop-casted on the surface of glassy carbon substrates, show that the electrode modified with LMG-Pd, in combination with carbon black, exhibits the lowest HER overpotential value.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

Perovskite-type materials based on LaMnO3, both undoped and doped with noble metals (Pd and Ag), were functionalized with graphene oxide (GO) using an ultrasound-assisted method involving a sonotrode immersed in an aqueous medium. The preparation method of pristine LaMnO3 and 1% Ag- or Pd-doped LaMnO3 perovskites has been previously reported in detail in our published work [21]. Graphene oxide was employed as an aqueous dispersion with a concentration of 4 mL/mL, and the weight ratio between the perovskite material and GO was maintained at 10:1 for all samples. For each sample (LMG, LMG-Pd, and LMG-Ag), 0.1 g of perovskite powder was mixed with 2.5 mL of GO dispersion (corresponding to approximately 0.01 g GO) in a Berzelius beaker and further diluted with ultrapure distilled water. The mixtures were subjected to ultrasonic treatment for 30 min using a Sonics Vibra Cell ultrasonic processor (Artisan Technology Group, Champaign, IL, USA) equipped with a titanium probe immersed directly in the reaction medium. The ultrasonic parameters were as follows: total time = 30 min, pulse mode = 10 s ON/5 s OFF, controlled temperature = 70 °C, and amplitude = 89%. After sonication, the samples underwent separation and drying steps. Specifically, they were centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min and then dried in an oven at 90 °C for approximately 2 h. This procedure enabled the effective anchoring of graphene oxide onto the perovskite surfaces under controlled thermal and ultrasonic conditions, leading to the formation of hybrid nanomaterials with potential applications as electrocatalysts and advanced functional materials. Scheme 1 shows the stages of the functionalization procedure.

Scheme 1.

The stages of the functionalization procedure.

For the electrochemical experiments, glassy carbon (GC) pellets (8 mm in diameter) were acquired from Andreescu Labor & Soft SRL (Bucharest, Romania). Carbon Black-Vulcan XC 72 was procured from Sigma Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA), and Nafion® 117 solution was purchased from Fuel Cell Store (Bryan, TX, USA). KOH and KCl were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), while absolute ethanol (99.5%) was acquired from ChimReactiv (Bucharest, Romania). All reagents were used as received, and double-distilled water was utilized to prepare all electrolyte solutions.

2.2. Electrode Development Method

Catalyst inks were obtained by dispersing the powder hybrid materials in ethanol. The perovskite hybrids were added alone or in a mixture with carbon black. Homogeneous dispersions resulted from applying an ultrasonication treatment for 30 min. In the next stage of the electrode preparation process, a volume of 10 µL was taken from each electrocatalyst-containing suspension and drop-casted onto the surface of the GC pellets. The modified pellets were dried at 40 °C until solvent evaporation, resulting in the electrodes specified in Table 1.

Table 1.

Electrode names and the contents of the catalyst inks.

This method for obtaining modified electrodes has been previously reported in studies aimed at evaluating the water electrolysis properties of electrocatalysts [22,23]. The GC pellets served as conductive substrates, carbon black is known to improve charge transport, and Nafion acts as a binder by preventing the detachment of the deposited particles from the substrate [24,25].

2.3. Electrochemical Experiments

All water electrolysis experiments were performed with a potentiostat, type Voltalab, model PGZ 402, purchased from Radiometer Analytical (Lyon, France). Three electrodes were connected to this apparatus and immersed in the electrolyte solution added to a standard electrolysis cell. Each modified electrode served as the working electrode. Furthermore, an unmodified GC pellet and an electrode modified using a carbon black-based catalyst ink without any electrocatalyst were also prepared and used as working electrodes. The pellets were studied after being inserted into a polyamide support, which limited the geometrical surface in contact with the electrolyte solution to 0.28 cm2. The auxiliary electrode was a Pt plate with a geometric surface of 0.8 cm2, and an Ag/AgCl (sat. KCl) electrode was used as reference. The strongly alkaline electrolyte solution was 1 M KOH. It was deaerated by bubbling with high-purity nitrogen before each HER test. The recorded cathodic polarization curves were iR-corrected and were obtained at a scan rate v = 5 mV/s. Well-known equations were used to represent the electrochemical potential (E) values in terms of the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) and to determine the HER overpotential (ηHER), the Tafel slope, the capacitive current density (idl), the roughness factor (Rf), and the electrochemically active surface area (ECSA) for the tested samples [23].

2.4. Physical-Chemical Analyses

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed using an X’Pert Pro diffractometer (PANalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands) equipped with a Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5406 Å). Data were collected over a 2θ range of 10° to 80°, using continuous scan mode with a step size of 0.02° and a scan rate of 2°/min. The resulting diffraction patterns were analyzed using the HighScore Plus software Version: 2.2b (2.2.2) (PANalytical). Peak positions and intensities were further used to assess the phase purity and crystallinity of the hybrid materials.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) images were acquired using a MultiView 2000 scanner (Nanonics Imaging Ltd., Jerusalem, Israel), in intermittent mode and with a tip radius of 20 nm.

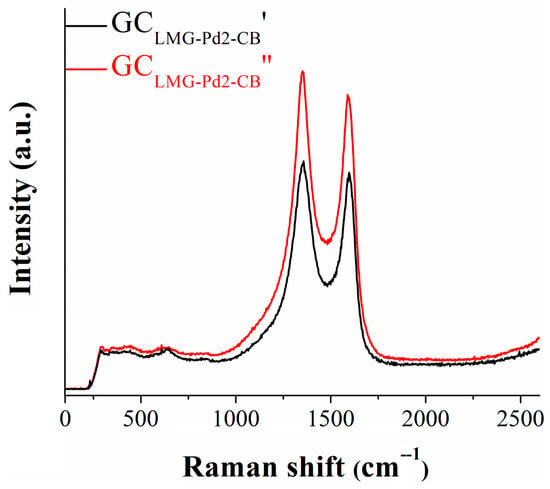

Raman analysis was performed on the most electrocatalytically active electrode identified during HER experiments, both before and after the electrochemical stability test. The spectra were recorded using a MultiView-2000 system (Nanonics Imaging Ltd., Jerusalem, Israel) with a Shamrock 500i spectrograph (Andor, Essex, UK). The excitation wavelength was 514 nm.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption measurements were carried out using a Quantachrome Nova 1200e analyzer (Quantachrome Instruments, Boynton Beach, FL, USA) at 77 K. Prior to analysis, the samples were degassed under vacuum at 40 °C for 12 h. The specific surface area was determined using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method, while the pore size distribution was calculated using the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method. The total pore volume was estimated from the amount of nitrogen adsorbed at the highest relative pressure on the adsorption branch of the isotherm.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. XRD and AFM Characterization of the Hybrid Materials

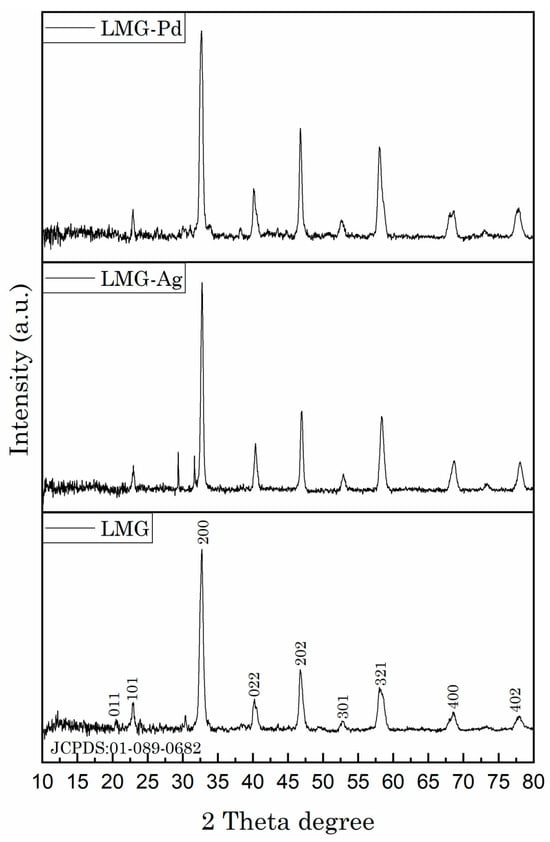

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Figure 1) was performed to comprehensively investigate the crystalline structure and phase composition of the synthesized hybrid materials. The diffraction patterns of the pristine perovskite (LMG) and the Ag- and Pd-doped samples (LMG-Ag and LMG-Pd) exhibit well-defined and sharp peaks at approximately 31°, 37°, 45°, 55°, 58°, 66°, and 74°. These reflections correspond closely to the characteristic planes of the perovskite crystal lattice, indicating that the fundamental perovskite structure is preserved despite the doping or functionalization processes [26]. Some small additional peaks are observed in the X-ray diffraction patterns, which originate from secondary phases introduced during the synthesis (e.g., NaOH, nitrates, and related byproducts) that were not completely removed during the washing process.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns for the LMG, LMG-Ag, and LMG-Pd materials.

The preservation of the perovskite phase after doping suggests that the incorporation of Ag and Pd ions into the lattice does not significantly disrupt the crystal framework. This observation is crucial, as it confirms the structural stability of the perovskite matrix and indicates successful doping without phase separation.

The characteristic reflections can be readily indexed to the (011), (101), (200), (022), (202), (301), (321), (400), and (402) planes, according to JCPDS card No. 01-089-0682, corresponding to an orthorhombic structure with space group Pnma (no. 62), and unit cell parameters: a = 5.72 Å, b = 7.67 Å, c = 5.53 Å, with α = β = γ = 90°.

Furthermore, subtle variations in peak intensities and slight shifts in peak positions among the samples suggest minor lattice distortions or changes in crystallinity. These changes can be attributed to the difference in ionic radii between the dopant ions (Ag+ and Pd2+) and the host lattice cations, which may induce local strain or defects within the crystal lattice [27]. Such modifications can influence the electrocatalytic properties of the material, highlighting the importance of controlled doping.

Regarding the graphene oxide (GO) functionalization, the typical broad and weak diffraction peak associated with the (001) plane of GO around 10–12° is not prominently observed, which could be due to the low GO content within the composite. The absence of a clear GO peak suggests a good dispersion and interaction between GO sheets and the perovskite particles, which is beneficial for enhancing the hybrid material’s surface area and electronic or catalytic properties [28].

In summary, the XRD analysis confirms that the perovskite structure remains largely intact following doping with Ag and Pd and functionalization with graphene oxide. The structural integrity, combined with the absence of phase segregation, supports the successful synthesis of hybrid materials with potentially enhanced functional properties.

The AFM investigation was performed on samples obtained using the same procedures as for the GCLMG, GCLMG-Ag, and GCLMG-Pd2 electrodes. The recorded AFM images are presented in Figures S1–S3 from the Supplementary Material file. The values of the AFM parameters obtained from the AFM images, namely the average roughness (Sa), mean square root roughness (Sq), maximum peak height (Sp), maximum valley depth (Sv), maximum peak-to-valley height (Sy), surface kurtosis (Sku), and surface skewness (Ssk), are shown in Table S1. The highest roughness values were found for the GCLMG-Pd2 sample (Sa = 184.2 nm and Sq = 233.6 nm), followed by the values found for the GCLMG-Ag sample (Sa = 62.82 nm and Sq = 77.77 nm) and for the GCLMG sample (Sa = 61.36 nm and Sq = 75.01 nm), respectively. In the case of the GCLMG-Ag and GCLMG samples, it is not just the values determined for the Sa and Sq parameters that were found to be similar, but also those for Sp, Sv, and Sy. However, GCLMG-Ag features more valleys, as suggested by the Ssk value and the slightly higher Sv value, indicative of a more porous surface. Morphologically, the surface of the GCLMG sample displays more clusters, whereas rounder and bigger shapes are observed on the surface of GCLMG-Ag, which may be a consequence of the Ag-doping. The GCLMG-Pd2 sample stands out in terms of both roughness and morphology. Apart from the higher Sa and Sq values, this is the only sample for which a positive Ssk value was found, indicating that its profile was skewed downward relative to the mean plane [29]. Lastly, Sku values < 3 were determined for all the samples, which are characteristic of surfaces with relatively few high peaks and low valleys [30].

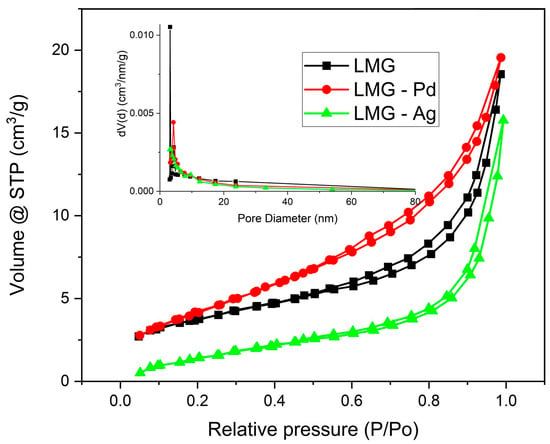

3.2. BET Analysis

The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of the hybrid materials are presented in Figure 2. The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of LaMnO3, Pd-doped LaMnO3, and Ag-doped LaMnO3 are type IV isotherms, characteristic of mesoporous materials, with a clear hysteresis loop associated with capillary condensation. This behavior indicates the presence of a well-developed mesoporous structure, typical for perovskite oxides synthesized via the sol–gel method.

Figure 2.

The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of LMG, LMG-Pd, and LMG-Ag.

Doping with Pd and Ag induces noticeable changes in the textural properties of LaMnO3. The doped samples show a higher nitrogen uptake at high relative pressures (P/P0 > 0.8) compared to pristine LaMnO3, suggesting an increased contribution of mesopores and a possible enhancement of the specific surface area and total pore volume. These textural modifications are expected to be beneficial for catalytic and photocatalytic applications by increasing the number of accessible active sites and improving mass transfer.

Table 2 shows the textural parameters data obtained from the N2 isotherms.

Table 2.

Textural parameters data obtained from the N2 isotherms.

The BET surface area values indicate that Pd doping slightly increases the specific surface area of LaMnO3 (15.7 m2/g) compared to the pristine sample (13.7 m2/g), which is beneficial for electrocatalytic applications in alkaline water electrolysis, as a higher surface area generally provides a larger number of accessible active sites. In contrast, Ag-doped LaMnO3 exhibits a lower surface area (8.3 m2/g), which may limit the density of electrochemically active sites and partially explain differences in electrocatalytic performance.

3.3. Water Electrolysis Study

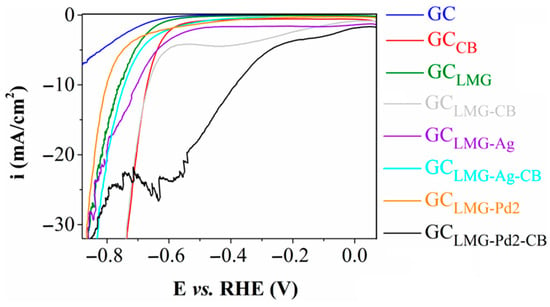

The cathodic polarization curves obtained on the modified electrodes are shown in Figure 3. It can be seen that the linear sweep voltammogram recorded on the GCLMG-Pd2-CB electrode stands out by reaching the −10 mA/cm2 current density at the lowest electrochemical potential value. The ηHER value corresponding to this current density is often determined and used to compare the electrocatalytic activities of different electrocatalysts [31]. Table 3 presents the ηHER values found for the studied electrodes.

Figure 3.

Cathodic polarization curves recorded on the GC, GCCB, GCLMG, GCLMG-CB, GCLMG-Ag, GCLMG-Ag-CB, GCLMG-Pd2, and GCLMG-Pd2-CB electrodes. Electrolyte solution: 1 M KOH. v = 5 mV/s.

Table 3.

HER overpotential values determined for the studied electrodes at i = −10 mA/cm2.

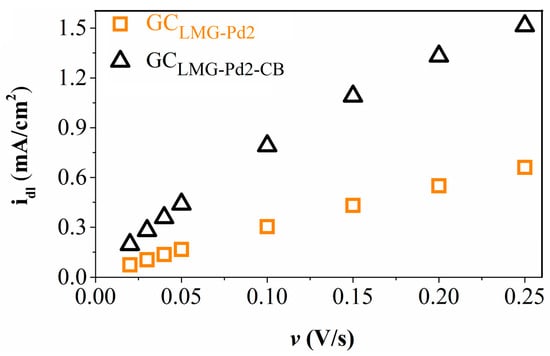

Since GCLMG-Pd2-CB shows the highest electrocatalytic activity, its electrochemical properties were further studied and compared to those of GCLMG-Pd2. The electrical double layer capacitance (Cdl), Rf, ECSA, and the Tafel slope were calculated based on the acquired experimental data, and their values are shown in Table 4. All the obtained values evidence the superior electrochemical properties of the GCLMG-Pd2-CB electrode. Importantly, the ECSA value is directly proportional to the number of electrocatalytically active sites involved in an electrocatalytic process [32]. The higher ECSA value of GCLMG-Pd2-CB helps to explain its higher electrocatalytic activity. Electrodes manufactured using carbon black can benefit from an increase in the number of their catalytic centers exposed to the electrolyte solution [33,34].

Table 4.

The electrochemical parameter values determined for the GCLMG-Pd2 and GCLMG-Pd2-CB electrodes.

To obtain the Cdl values from Table 4, cyclic voltammograms were recorded at increasing scan rate values. These are shown in Figure S4 from the Supplementary Material file (Figure S4a for GCLMG-Pd2 and Figure S4b for GCLMG-Pd2-CB). The acquired data were used to calculate the idl values, subsequently represented in the idl vs. scan rate plot from Figure 4. The Cdl values are the slopes of the curves in Figure 4 and were used to calculate the Rf and ECSA parameter values [23].

Figure 4.

The capacitive current density vs. scan rate plots obtained for the GCLMG-Pd2 and the GCLMG-Pd2-CB electrodes.

The catalytic kinetics at the interface between the electrodes and the electrolyte solution were also investigated. The Tafel and Nyquist plots are shown in Figure 5a and Figure 5b, respectively. Figure 5c presents the chronoamperometric curve recorded during the electrochemical stability test performed on GCLMG-Pd2-CB.

Figure 5.

(a) HER Tafel plots for the GCLMG-Pd2 and GCLMG-Pd2-CB electrodes in 1 M KOH solution. The current density (iECSA) is ECSA-normalized. (b) Nyquist plots of GCLMG-Pd2 and GCLMG-Pd2-CB obtained in 1 M KOH solution. The inset shows the equivalent circuit. (c) Chronoamperometric curve recorded on GCLMG-Pd2-CB in 1 M KOH solution and inset showing the cathodic polarization curves obtained on GCLMG-Pd2-CB before (GCLMG-Pd2-CB′) and after (GCLMG-Pd2-CB″) the electrochemical stability experiment (1 M KOH solution, scan rate = 5 mV/s).

A low Tafel slope value means faster reaction kinetics [35]. However, even though the value determined for GCLMG-Pd2-CB is lower than the one found for GCLMG-Pd2, it is still characteristic of electrocatalysts with sluggish HER kinetics. When the Tafel slope is in the 40 to 120 mV/dec, the HER is probably unfolding through a Volmer–Heyrovsky mechanism, but when the slope value is higher than 120 mV/dec, and the reaction takes place in a strong alkaline environment, the probable mechanism is a Volmer-limited one, with the Heyrovsky step slower than the Volmer step [36,37]. The Tafel slope is affected by the pH of the electrolyte solution, and at high pH values, most of the electrode’s surface becomes covered by hydrogen bubbles, which can cause the slope value to surpass 120 mV/dec [36,38].

The EIS spectra of GCLMG-Pd2 and GCLMG-Pd2-CB were recorded at the ηHER values corresponding to i = −10 mA/cm2. The electrodes were biased at 10 mV within the 105 to 10−2 Hz frequency range. The EIS measurements under HER conditions provide the charge transfer resistance (R2) of the two electrodes. A semicircle can be observed in both cases, the size of which is a quantitative indicator of R2 at the electrode/electrolyte interface during the HER [39]. The Nyquist plots were fitted with the Randles equivalent circuit (inset of Figure 5b), using ZView software (Version: 2.80, Scribner Associates Inc., Southern Pines, NC, USA). The simple circuit consists of the Ohmic resistance (R1), the constant phase element (CPE1), and the charge transfer resistance (R2). The small R1 values determined for the two electrodes (2.51 Ω for GCLMG-Pd2 and 2.38 Ω for GCLMG-Pd2-CB) point to a close contact between the electrocatalyst and the GC support. However, the R2 value obtained for GCLMG-Pd2 is smaller than the value found for GCLMG-Pd2-CB (43.68 Ω vs. 58.17 Ω). This suggests that the addition of carbon black did not have the intended effect of enhancing electrical conductivity. Still, it is probably responsible for GCLMG-Pd2-CB’s higher ECSA value.

The overall conclusion of the comparative evaluation of GCLMG-Pd2 and GCLMG-Pd2-CB regarding their electrochemical properties is that the latter electrode possesses superior characteristics and displays a higher HER water electrolysis activity.

The electrochemical stability of GCLMG-Pd2-CB was investigated during a 24 h chronoamperometric experiment at a constant potential value corresponding to i = −10 mA/cm2. After the first hour and until the end of the test, the recorded i-t curve (Figure 5c) shows shifts in current density, between −13 and −16 mA/cm2, indicating the relative stability of the studied electrode. The inset of Figure 5c presents the cathodic polarization curves obtained before (GCLMG-Pd2-CB′) and after (GCLMG-Pd2-CB″) the amperometric experiment. The ηHER value at i = −10 mA/cm2 increased by ~40 mV following the test. Because this difference is somewhat higher than the differences often observed when performing stability tests relevant to the water splitting domain [40,41,42], Raman analysis was used to verify the occurrence of any changes in the chemical structure of the electrocatalyst. The spectra recorded on the GCLMG-Pd2-CB electrode, before (GCLMG-Pd2-CB′) and after (GCLMG-Pd2-CB″) the stability test, are given in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Raman spectra obtained on GCLMG-Pd2-CB before (GCLMG-Pd2-CB′) and after (GCLMG-Pd2-CB″) the amperometric stability test.

The analyzed samples (GCLMG-Pd2-CB′ and GCLMG-Pd2-CB″) revealed the same structure since there were no visible changes in the 300–650 cm−1 specific LaMnO3 bands corresponding to the Mn-O bond [43]. However, the aforementioned bands were weak in comparison to the carbon-specific bands located in the 1350–1600 cm−1 region. The LaMnO3 bands appeared like “noise” in the Raman spectra. After the chronoamperometric experiment, there were no shifts of the carbon-specific bands (1358 cm−1 and 1601 cm−1), only slight width modifications, suggesting the presence of induced defects [44]. The changes in peak intensities were due to the defects that appeared after the chronoamperometric experiment as a consequence of the reduction of oxygenated surface functional groups. The application of a negative potential led to a decrease in oxygen-containing bonds, particularly C–O (epoxy) and C=O groups. As oxygen is removed, the intensity of sp3 C–C bonds increases, effectively restoring the sp2 carbon network of the material [45,46].

Lastly, the HER electrocatalytic activity of GCLMG-Pd2-CB was compared to that of other perovskite oxide-based electrodes reported in the scientific literature and also studied in a 1 M KOH electrolyte solution. The results are presented in Table S2 from the Supplementary Material file. They show that the ηHER value of 0.385 V is lower than most of the values mentioned for the identified electrodes. Out of the 35 values from published literature studies, 22 are higher than the value found in the present investigation. Furthermore, some of the remaining values are comparable to it. These observations position the GCLMG-Pd2-CB electrode relatively high among perovskite oxide-based electrodes previously investigated regarding their water splitting electrocatalytic activity.

4. Conclusions

In this work, a new class of noble metal-doped LaMnO3/graphene oxide (GO) hybrid materials was successfully synthesized and evaluated as electrocatalysts for alkaline water electrolysis. Ultrasonic functionalization enabled effective anchoring of GO onto pristine and Ag- or Pd-doped LaMnO3 surfaces, while preserving the perovskite crystalline structure, as confirmed by XRD. BET analysis revealed that Pd doping increased the specific surface area from 13.7 m2/g for pristine LaMnO3 to 15.7 m2/g, while Ag doping decreased it to 8.3 m2/g. Total pore volume also increased slightly upon Pd doping (0.0303 cm3/g) compared to pristine LaMnO3 (0.0288 cm3/g), indicating improved mesoporosity. AFM measurements showed that Pd-doped LaMnO3/GO exhibited the highest surface roughness. Electrochemical tests demonstrated that the GCLMG-Pd2-CB electrode obtained using the Pd-doped LaMnO3/GO hybrid in combination with carbon black achieved the lowest HER overpotential of 0.385 V at −10 mA/cm2, outperforming the other electrodes. This study represents the first report on LaMnO3/GO hybrids, both undoped and noble metal-doped, as electrocatalysts for alkaline water electrolysis. Future work will focus on improving the Tafel slope by employing advanced electrode modification techniques such as pulsed laser deposition (PLD).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nano16020107/s1. Figure S1. 3D AFM image (a) and AFM profile image of selected area (b) obtained for the GCLMG sample; Figure S2. 3D AFM image (a) and AFM profile image of selected area (b) obtained for the GCLMG-Ag sample; Figure S3. 3D AFM image (a) and AFM profile image of selected area (b) obtained for the GCLMG-Pd2 sample; Figure S4. (a) Cyclic voltammograms recorded on GCLMG-Pd2 in the −250–100 mV range, at increasing scan rate values (20, 30, 40, 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 mV/s). (b) Cyclic voltammograms recorded on GCLMG-Pd2-CB in the −250–100 mV range, at increasing scan rate values (20, 30, 40, 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 mV/s). Electrolyte solution: 0.1 M KCl; Table S1. The values of the AFM parameters; Table S2. The HER activity of the GCLMG-Pd2-CB electrode and of other perovskite oxide-based electrodes in 1 M KOH solution. The ηHER values are read at i = −10 mA/cm2. References [19,38,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60] are cited in the Supplementary Material file.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S. (Paula Sfirloaga); methodology, P.S. (Paula Sfirloaga); formal analysis, P.S. (Paula Sfirloaga), B.-O.T., P.S. (Paula Svera), M.P., D.B.; investigation, P.S. (Paula Sfirloaga), B.-O.T., P.S. (Paula Svera), M.P., D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S. (Paula Sfirloaga), B.-O.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the PNRR-III-C9-2023 I8, CF 39/28.07.2023: “Selective resource recovery from kitchen waste by integrated Dark Fermentation-Microbial electrolysis cell and ion substitution electrodialysis” project.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Daniel Ursu from the National Institute of Research and Development for Electrochemistry and Condensed Matter (Timisoara, Romania) for his help with the EIS analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kazemi, A.; Manteghi, F.; Tehrani, Z. Metal electrocatalysts for hydrogen production in water splitting. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 7310–7335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.; Gui, M.M.; Robertson, P.K.J. The environmental emission and climate change impact of hydrogen fuel derived from photocatalysis water-splitting reaction. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2025, 6, 2400337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. Minireview on perovskite oxide-based materials toward enhanced electrocatalytic nitrate reduction for ammonia synthesis: Advances and perspectives. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 20129–20143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megía, P.J.; Vizcaíno, A.J.; Calles, J.A.; Carrero, A. Hydrogen production technologies: From fossil fuels toward renewable sources. A mini review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 16403–16415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatenet, M.; Pollet, B.G.; Dekel, D.R.; Dionigi, F.; Deseure, J.; Millet, P.; Braatz, R.D.; Bazant, M.Z.; Eikerling, M.; Staffell, I.; et al. Water electrolysis: From textbook knowledge to the latest scientific strategies and industrial developments. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 4583–4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B. Liquid hydrogen carriers: Linking renewable energies for a carbon-neutral future. Innov. Energy 2024, 1, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Lim, H. An overview of water electrolysis technologies for green hydrogen production. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 13793–13813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Troostwijk, A.P.; Deiman, J.R. Lettre à M. de la Mètherie, sur une manière de dècompose l’eau en air inflammable et en air vital. J. Phys. Chim. Hist. Nat. 1789, 35, 369–378. [Google Scholar]

- Han, N.; Race, M.; Zhang, W.; Marotta, R.; Zhang, C.; Bokhari, A.; Klemes, J.J. Perovskite and related oxide based electrodes for water splitting. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 318, 128544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babar, P.; Patil, K.; Mahmood, J.; Kim, S.-J.; Kim, J.H.; Yavuz, C.T. Low-overpotential overall water splitting by a cooperative interface of cobalt-iron hydroxide and iron oxyhydroxide. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2022, 3, 100762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christy, M.; Rajan, H.; Subramanian, S.S.; Choi, S.; Kwon, J.; Patil, S.A.; Lee, K.; Park, H.B.; Song, T.; Paik, U. Tuning the surface chemistry of La0.6Sr0.4CoO3-δ perovskite via in-situ anchored chemical bonds for enhanced overall water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Cao, P.; Chen, W.; Ezeh, C.I.; Chen, Z.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, H.; Rui, Z.; Gao, S.; et al. Electrocatalysis enabled transformation of earth-abundant water, nitrogen and carbon dioxide for a sustainable future. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 1359–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.T.; Tran, P.K.L.; Malhotra, D.; Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, T.T.A.; Duong, N.T.A.; Kim, N.H.; Lee, J.H. Current status of developed electrocatalysts for water splitting technologies: From experimental to industrial perspective. Nano Converg. 2025, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, J.; Shi, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, P.; Xiao, M.; Liu, C.; Xing, W. Development of noble metal-free electrocatalysts towards acidic water oxidation: From fundamental understanding to state-of-the-art catalysts. eScience 2025, 5, 100295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hota, P.; Das, A.; Maiti, D.K. A short review on generation of green fuel hydrogen through water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Kitiphatpiboon, N.; Feng, C.; Abudula, A.; Ma, Y.; Guan, G. Recent progress in transition-metal-oxide-based electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction in natural seawater splitting: A critical review. eScience 2023, 3, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Mehran, M.T.; Naqvi, S.R.; Khoja, A.H.; Mahmood, K.; Shahzad, F.; Hussain, S. Role of perovskites as a bi-functional catalyst for electrochemical water splitting: A review. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alom, S.; Kananke-Gamage, C.C.W.; Ramezanipour, F. Perovskite oxides as electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 7444–7451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, Z.; Su, C.; Liu, M.; Shao, Z. A perovskite electrocatalyst for efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 6442–6448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cata, A.; Taranu, B.-O.; Ienascu, I.M.C.; Sfirloaga, P. New PVP–Ag or Pd-doped perovskite oxide hybrid structures for water splitting electrocatalysis. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfirloaga, P.; Ivanovici, M.-G.; Poienar, M.; Ianasi, C.; Vlazan, P. Investigation of Catalytic and Photocatalytic Degradation of Methyl Orange Using Doped LaMnO3 Compounds. Processes 2022, 10, 2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfirloaga, P.; Bognar, S.; Taranu, B.-O.; Vlazan, P.; Poienar, M.; Merkulov, D.S. Co- and Sn-doped YMnO3 perovskites for electrocatalytic water-splitting and photocatalytic pollutant degradation. Coatings 2025, 15, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranu, B.-O.; Svera, P.; Buse, G.; Poienar, M. Insights into the electrocatalytic activity of mixed valence Mn3+/Mn4+ and Fe3+/Fe4+ transition metal oxides materials. Solids 2025, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappan, K.; Alagarsamy, S.; Chen, S.-M.; Sakthinathan, S. Fabrication of ZnWO4/carbon black nanocomposites modified glassy carbon electrode for enhanced electrochemical determination of ciprofloxacin in environmental water samples. Materials 2023, 16, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakati, N.; Anderson, L.; Li, G.; Sua-an, D.M.; Karmakar, A.; Ocon, J.D.; Chuang, P.-Y.A. Indispensable Nafion ionomer for high-efficiency and stable oxygen evolution reaction in alkaline media. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 55559–55569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Fernandez, M.; Pinero, J.C.; Alcantara, R.; Gallardo, J.J.; Navas, J. Emission properties of Pd-doped CsPbBr3 perovskite nanocrystal: Infrared emission due to the Pd-doping. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Moon, K.; Shoaib, M.; Thapa, P.; Sun, R.; Yang, S.; Heo, J.-M.; Seong, S.; McCracken, J.; Gong, X.; et al. Deterministic structural distortion in Mn2+-doped layered hybrid lead bromide perovskite single crystals. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 26920–26931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, D.R.; Park, S.; Bielawski, C.W.; Ruoff, R.S. The chemistry of graphene oxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, M.; Stefaniuk, T.; Pniewski, J. The technique of measurement of intraocular lens surface roughness using atomic force microscopy. Interdiscip. J. Eng. Sci. 2014, 2, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlacek, M.; Gregorcic, P.; Podgornik, B. Use of the roughness parameters Ssk and Sku to control friction—A method for designing surface texturing. Tribol. Trans. 2016, 60, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lu, A.; Zhong, C.-J. Hydrogen production from water electrolysis: Role of catalysts. Nano Converg. 2021, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Zaman, W.Q.; Sun, W.; Cao, L.M.; Tariq, M.; Yang, J. Cultivating crystal lattice distortion in IrO2 via coupling with MnO2 to boost the oxygen evolution reaction with high intrinsic activity. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudgeon, D.P.; Li, X. Enhanced surface area carbon cathodes for the hydrogen–bromine redox flow battery. Batteries 2022, 8, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Lian, G.J.; Parker, J.; Ge, R.; Sadan, M.K.; Smith, R.M.; Cumming, D. Effect of carbon blacks on electrical conduction and conductive binder domain of next-generation lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2024, 592, 233916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.S.; Madhu, R.; Karmakar, A.; Kundu, S. From theory to practice: A critical and comparative assessment of Tafel slope analysis techniques in electrocatalytic water splitting. ACS Mater. Lett. 2024, 6, 3112–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, F.; Kemppainen, E.; Dorbandt, I.; Bors, R.; Xi, F.; Schlatmann, R.; van de Krol, R.; Calnan, S. Understanding the hydrogen evolution reaction kinetics of electrodeposited nickel-molybdenum in acidic, near-neutral, and alkaline conditions. ChemElectroChem 2021, 8, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Y.; Hu, B.C.; Wu, P.; Liang, H.W.; Yu, Z.L.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, Y.R.; Li, Z.; Yu, S.H. Mo2C nanoparticles embedded within bacterial cellulose-derived 3D N-doped carbon nanofiber networks for efficient hydrogen evolution. NPG Asia Mater. 2016, 8, e288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfirloaga, P.; Taranu, B.-O.; Poienar, M.; Vlazan, P. Addressing electrocatalytic activity of metal-substituted lanthanum manganite for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Surf. Interfaces 2023, 39, 102881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Sun, H.; Wang, H.; Rong, F.; He, L.; Lou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Du, M. CoOx/CoNy nanoparticles encapsulated carbon-nitride nanosheets as an efficiently trifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting and Zn-air battery. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 279, 119407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadeer, M.A.; Zhang, X.; Farid, M.A.; Tanveer, M.; Yan, Y.; Du, S.; Huang, Z.-F.; Tahir, M.; Zou, J.-J. A review on fundamentals for designing hydrogen evolution electrocatalyst. J. Power Sources 2024, 613, 234856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Du, M.; Tian, K.; Yan, J. Recent development of electrodes construction for HER in electrocatalytic water splitting. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202400847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveendran, A.; Chandran, M.; Dhanusuraman, R. A comprehensive review on the electrochemical parameters and recent material development of electrochemical water splitting electrocatalysts. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 3843–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Carrón, L.; de Andrés, A. Melting of the cooperative Jahn-Teller distortion in LaMnO3 single crystal studied by Raman spectroscopy. Eur. Phys. J. B 2001, 22, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dychalska, A.; Popielarski, P.; Franków, W.; Fabisiak, K.; Paprocki, K.; Szybowicz, M. Study of CVD diamond layers with amorphous carbon admixture by Raman scattering spectroscopy. Mater. Sci.-Pol. 2015, 33, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quezada-Renteria, J.A.; Ania, C.O.; Chazaro-Ruiz, L.F.; Rangel-Mendez, J.R. Influence of protons on reduction degree and defect formation in electrochemically reduced graphene oxide. Carbon 2019, 149, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Zeng, R.; Zhuo, Y.; Lu, M.; Shi, G.; Gu, H. Tailoring oxygen-containing groups on graphene for ratiometric electrochemical measurements of ascorbic acid in living subacute Parkinson’s Disease mouse brains. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 16598–16607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junita, J.; Jayalakshmi, D.; Rodney, J.D. Combustion-derived BaNiO3 nanoparticles as a potential bifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 14287–14298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmad, Q.; Khan, U.M.; Baig, M.M.; Hassan, M.; Butt, F.A.; Khoja, A.H.; Liaquat, R.; Khan, Z.S.; Anwar, M.; Muhammed Ali, S.A. Praseodymium-doped Sr2TiFeO6-δ double perovskite as a bi-functional electrocatalyst for hydrogen production through water splitting. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranu, B.-O.; Vlazan, P.; Svera, P.; Poienar, M.; Sfirloaga, P. New functional hybrid materials based on clay minerals for enhanced electrocatalytic activity. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 892, 162239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Xie, Y.; Hao, X.; Xia, T.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Huo, L.; Zhao, H. Addressing electrocatalytic activity and stability of LnBaCo2O5+δ perovskites for hydrogen evolution reaction by structural and electronic features. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 297, 120403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, S.B.; Andriotis, A.N.; Menon, M.; Ramezanipour, F. Bifunctional water-splitting electrocatalysis achieved by defect order in LaA2Fe3O8 (A = Ca, Sr). ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 12063–12066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alom, M.S.; Ramezanipour, F. Layered oxides SrLaFe1-xCoxO4-δ (x=0–1) as bifunctional electrocatalysts for water-splitting. ChemCatChem 2021, 13, 3510–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Liu, C.; Yao, Y.; Luo, L.; Wang, W.; Chen, Z. Cerium substitution in LaCoO3 perovskite oxide as bifunctional electrocatalysts for hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 9952–9959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Pan, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Ge, L.; Jiang, S.P.; Shao, Z. From scheelite BaMoO4 to perovskite BaMoO3: Enhanced electrocatalysis toward the hydrogen evolution in alkaline media. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 198, 108214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hona, R.K.; Karki, S.B.; Ramezanipour, F. Oxide electrocatalysts based on earth-abundant metals for both hydrogen- and oxygen-evolution reactions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 11549–11557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Tan, K.; Gong, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, H.; Zhao, L. Coupling amorphous cobalt hydroxide nanoflakes on Sr2Fe1.5Mo0.5O5+δ perovskite nanofibers to induce bifunctionality for water splitting. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 9048–9057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Chen, Z.; Zuo, F.; Hua, B.; Zhou, H.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Sun, Y. Enhancing perovskite electrocatalysis through synergistic functionalization of B-site cation for efficient water splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 401, 126082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Q.A.; Majee, R.; Bhattacharyya, S. Bimetallic nanoparticle decorated perovskite oxide for state-of-the-art trifunctional electrocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 19453–19464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Dai, Z.; Tan, S.; Chen, D. Promoting hydrogen-evolution activity and stability of perovskite oxides via effectively lattice doping of molybdenum. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 312, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, N.K.; Kim, C.; Lee, J.; Kwon, O.; Choi, Y.; Jung, G.Y.; Lim, H.Y.; Kwak, S.K.; Kim, G.; Park, H. In-situ local phase-transitioned MoSe2 in La0.5Sr0.5CoO3-δ heterostructure and stable overall water electrolysis over 1000 hours. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.