Abstract

The reverse water–gas shift (RWGS) reaction serves as a highly flexible and critical pathway for converting CO2 into CO, with Pt-based catalysts having been widely investigated. Here, a series of platinum-rare earth (RE) subnanometric bimetallic clusters (SBCs) were successfully prepared on carbon support by the potassium vapor reduction method. Their structure and electronic properties, along with catalytic performance, were systematically characterized and evaluated. The Pt-RE SBC catalysts exhibited excellent catalytic activity, maintaining CO selectivity above 95% at high CO2 conversion levels and demonstrating stable operation over 100 h at 600 °C. Furthermore, the influence of different supports (carbon black and CeO2) on the catalytic performance was compared. It was found that Pt-Sc SBCs supported on the carbon exhibited better dispersion, smaller particle size, and superior catalytic performance relative to the CeO2 supported counterpart. This study provides new insights into the design of highly efficient and stable RWGS catalysts, highlighting the key role of the Pt-RE SBC interface synergistic effect and support selection, which is of great significance for the resource utilization of CO2.

1. Introduction

With the ongoing consumption of fossil fuels, atmospheric CO2 concentrations continue to increase, leading to increasingly serious global greenhouse effects and adverse outcomes such as ocean acidification [1,2]. Carbon capture and utilization (CCU) serves as an effective solution, aiming to mitigate the challenges associated with CO2 emissions. The core of CCU lies in converting captured CO2 into high-value-added products through chemical synthesis, thereby enabling carbon recycling and emission reduction [3,4]. Among the various approaches, the conversion of CO2 to CO via the reverse water–gas shift (RWGS) reaction represents a highly flexible and critical pathway [5]. The produced CO acts as a vital platform molecule, which can be further converted into high-value chemicals such as olefins and alcohol-based fuels through the Fischer–Tropsch (F-T) synthesis process. This integrated route holds significant importance for environmental improvement and transition of future energy systems, attracting widespread attention [6,7].

The high bond energy and thermodynamic stability of the C=O bond in a CO2 molecule necessitates substantial energy input for its direct activation, while the kinetic limitations further restrict the reaction rate. Therefore, it is very important to develop efficient catalysts [8]. Catalysts prepared by supporting active metals on inorganic oxides (e.g., SiO2 [9], Al2O3 [10], TiO2 [11], or CeO2 [12,13]) have demonstrated high efficiency. Based on the active metal, these catalysts can be classified into non-noble metals (e.g., Cu [14,15], Ni [16,17], Co [18]) and noble metals (e.g., Pt [9,19], Pd [20], Ru [21,22]). Among these active metals, Cu, Ni, and Co exhibit low CO desorption energy, which helps inhibit methanation to some extent. However, these catalysts often suffer from limited thermal stability under operating conditions with an appreciable CO2 conversion rate. In contrast, noble metal catalysts (e.g., Pt, Pd, Ru) achieve higher CO2 conversion at low temperature, yet their stronger CO adsorption energy tends to promote CH4 formation during the reaction [19,23,24]. Therefore, further study is still needed to improve CO selectivity and catalyst stability while maintaining high CO2 conversion rate.

Pt-based catalysts are widely employed in RWGS reactions due to their high conversion at low temperatures. Considerable efforts have been devoted to the design and preparation of Pt-based catalysts, with strategies such as improving metal dispersion [12], modifying supports via doping [25], and constructing alloy structures [26,27,28,29,30,31] proving effective in enhancing catalytic performance. Among these, the formation of Pt with other metals offers a promising approach to adjust the electronic properties, thereby significantly improving CO2 conversion and CO selectivity while maintaining excellent stability at high-temperature conditions. Compared with monometallic Pt/SiO2 catalysts, the Pt-In/SiO2 catalyst exhibited near 100% the CO selectivity and higher activity in the temperature range of 140–200 °C [26]. Li et al. [28] used density functional theory (DFT) and Kinetic Monte Carlo (KMC) simulations to demonstrate that supported Pt-Ni alloy nanostructures outperform their monometallic Pt or Ni counterparts during RWGS reactions. Zhang et al. [29] further explored the synergistic mechanism between Ni and Pt sites on Pt3Ni nanowires during RWGS reactions. They identified a unique Ni-Pt hybrid configuration at the edges of nanowires, which contributed to high catalytic activity. In a structural design study, a PtFe core–shell catalyst was prepared (Pt/Fe = 1:1) and its catalytic activity was 5.1 times higher than that of Pt nanoparticles, highlighting the effectiveness of bimetallic synergy core–shell architecture in thermal catalytic process [30]. Moreover, a dual-site catalyst comprising Pt and Fe atoms co-loading on the surface of CeO2 was reported [31]. In this system, Fe atoms not only act as electronic promoters to modulate the charge density of Pt but also suppress CO methanation, thereby enhancing the catalytic activity and stability.

Rare earth (RE) elements, are often referred to as “industrial vitamins”, play a vital role in various industrial applications. In catalysis, they have been widely utilized in processes such as propane dehydrogenation and ethane oxidative dehydrogenation (EOD) [32,33,34]. Pt-M (M = La, Y and Sc) nanoparticles supported on zeolite nanosponges were synthesized and evaluated in the oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane using CO2 as a soft oxidant [33]. Ryong Ryoo et al. [34] reported that PtY intermetallic compound nanoparticles formed within mesoporous zeolite serve as a highly active, selective and stable catalyst for propane dehydrogenation. Due to its unique electronic structure, rare earth alloys can improve the catalytic activity by regulating the electronic structure and d-band center of active metals [34,35,36]. Sun et al. [36] synthesized a series of Pt-Ru-RE ternary alloys exhibiting high activity and high stability. DFT calculations showed that rare earth atoms induce a downshift in the d-band center of Pt surfaces and promote an electron-rich state, and thereby catalytic performance. Moreover, the high formation enthalpy of Pt-RE alloys leads to strong bonding between Pt-RE, thus significantly enhancing the durability of the catalysts [37]. However, the low reduction potential (ranging from −2 V to −3 V) of rare earth elements poses a challenge for their synthesis [34,38,39]. Luo et al. [36,38,39] developed a universal synthesis route based on sodium vapor reduction, and successfully realized the controllable synthesis of a series of noble metal–rare earth alloy materials. However, this strategy still has some limitations when applied to platinum-based alloy systems. An ideal carbon support should not only stabilize highly dispersed metal nanoparticles but also, through fine-tuning of its physical structure and chemical properties, synergize with the metal to collectively promote the efficient and highly selective activation and conversion of CO2 molecules [40]. Sub-nanometer catalysts fundamentally alter the activation mode of CO2 molecules by maximizing the exposure of unsaturated active atoms, inducing abrupt changes in electronic structure due to quantum size effects, and forming strong, tunable electronic interactions with the support [41].

Inspired by these advances, this work introduces a potassium vapor reduction method for preparing Pt-RE SBCs catalysts for RWGS reaction. Seven different Pt-RE SBCs (RE = La, Nd, Gd, Ho, Dy, Yb, Sc) were synthesized on carbon support. Among them, Pt-Sc SBCs nanoparticles show the highest CO2 conversion and CO selectivity. It was observed that a rare earth oxide layer is formed on the surface of the Pt-RE SBCs catalyst, endowing the catalyst with high conversion, high selectivity, and remarkable stability at high temperatures. In addition, the effect of catalyst support was systematically investigated. Pt-Sc SBCs supported on CeO2 showed inferior performance compared to the carbon-support system, primarily due to the increase in particle size and non-uniform distribution of the SBC particles on the non-carbon support. This work provides valuable guidance for the design of more effective SBC catalysts for CO2 conversion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Chloroplatinic acid hexahydrate (H2PtCl6·6H2O, 99.9%) was purchased from Adamas Reagent Company, Shanghai, China, while the rare earth chloride salts hydrate (LaCl3·6H2O, NdCl3·7H2O, GdCl3·6H2O, DyCl3·6H2O, HoCl3·6H2O, YbCl3·6H2O, 99% ScCl3·6H2O) and the sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99.999%) were purchased from Aladdin Reagent (Shanghai, China). Analytically pure potassium metal (K) was purchased from Tianjin Bohua Chemical Reagent Company, Tianjin, China. Methanol (CH3OH) and isopropanol (C3H8O) were purchased from Aladdin Reagent Company. Carbon black BP 2000 (Black Perals 2000) was purchased from Cabot Company, Boston, MA, USA. Ce(NO3)2·6H2O was purchased from Adamas Reagent Company. The water used in the experiments was lab-prepared ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm).

2.2. Catalyst Preparation

To prepare the 1 wt% Pt-RE/C catalyst, 0.0103 mmol H2PtCl6·6H2O and 0.0428 mmol rare earth chloride salts (LaCl3·6H2O, NdCl3·6H2O, GdCl3·6H2O, DyCl3·6H2O, HoCl3·6H2O, YbCl3·6H2O, 99% ScCl3·6H2O) were dissolved in 20 mL of ultrapure water in a round bottom flask. Then, 200 mg of carbon black was added to the mixture, followed by sonication for 30 min, and stirring for 12 h. Following rotary evaporation and drying of the resultant mixture, the precursor powder was obtained. Within a glove box, the precursor was placed into a circular BN crucible, which was then sealed together with another BN crucible containing a K ingot inside a cuboid BN crucible. The sealed setup was heated at 600 °C (10 °C/min ramp) for 2 h in a Muffle oven. After naturally cooling to room temperature, the sample was transferred out of the glove box and washed sequentially with isopropanol, ethanol, and deionized water. To remove rare earth oxides, the sample was treated with 0.5 M H2SO4 and then vacuum dried at 60 °C for 12 h to obtain the Pt-RE/C catalyst.

2.3. Catalytic Performance Testing

The catalytic performance was tested in a fixed bed reactor under atmospheric pressure. A 20 mg sieved sample (20–40 mesh) was mixed with 500 mg inert SiO2, and loaded into a quartz tube. Prior to the reaction, the catalyst was pretreated with 5% H2/Ar (30 mL/min) at 600 °C for 0.5 h. The temperature of the catalyst was decreased to room temperature, and the gas flow was switched to RWGS reaction gas mixture (23% CO2, 69% H2, 8% N2) at a gas hourly space velocity (GHSV) of 200,000 mL·gcat−1h−1. The reaction was maintained for at least 1 h at each target temperature. Catalyst stability was assessed under continuous flow at 600 °C using the same GHSV and reaction atmosphere over an extended period. The outlet products were analyzed by an online gas chromatograph equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). The gas flow rate was determined by the internal standard method, with N2 as the internal standard. The CO2 conversion and the CO selectivity were calculated according to the following formula.

where is the concentration of CO2 in the reaction gas, and is the concentration of CO2 in the outlet gas. and refer to the chromatographic peak area of CO2 and N2 in the inlet gas, respectively, and refer to the chromatographic peak area of CO2 and N2 in the outlet gas respectively. The chromatographic peak area of each component is proportional to the concentration of each component.

The calculation process of CO selectivity is as follows:

where and indicate the concentration of CO and CH4 in the gas, respectively. and are the relative correction coefficients of CO to N2 and CH4 to N2, respectively, which are calibrated by standard gas. and are the chromatographic peak areas of CO and CH4 detected by TCD in the outlet gas.

2.4. Catalyst Characterization

The crystalline phase and structure of the material were characterized by X-ray diffractometer (XRD) on a Rigaku Smart Lab diffractometer using Cu Kɑ radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) operated at 40 kV and 40 mA. Data were collected in the 2θ range of 10° to 90° with a scanning speed of 8° min−1. The morphology and microstructure of the material were obtained using a transmission electron microscope (TEM) on a JEM-2800 instrument and spherical aberration corrected TEM on JEM-ARM200F instrument, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan. For TEM analysis, the sample was dispersed in ethanol and ultrasonicated for 15 min. A drop of the resulting suspension was then deposited onto a copper grid and dried at ambient temperature prior to observation. The surface chemical states and electronic structure of the catalysts were investigated using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). XPS measurements were conducted on a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a monochromatic Al Kɑ X-ray source (hʋ = 1486.6 eV).

3. Results and Discussion

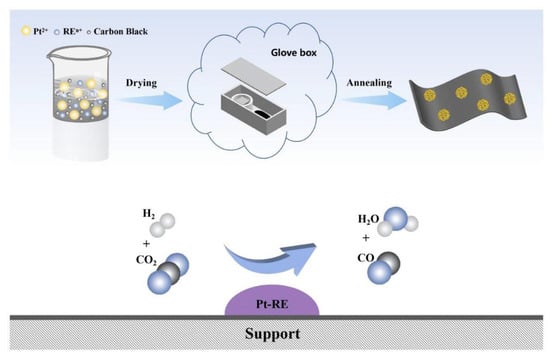

A series of Pt-RE SBCs supported on carbon were synthesized by a potassium vapor-assisted method. Figure 1 shows the schematic of the synthetic procedure for Pt-RE SBCs and the RWGS reaction process.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the synthetic procedure for Pt-RE SBCs and the diagram of RWGS reaction process.

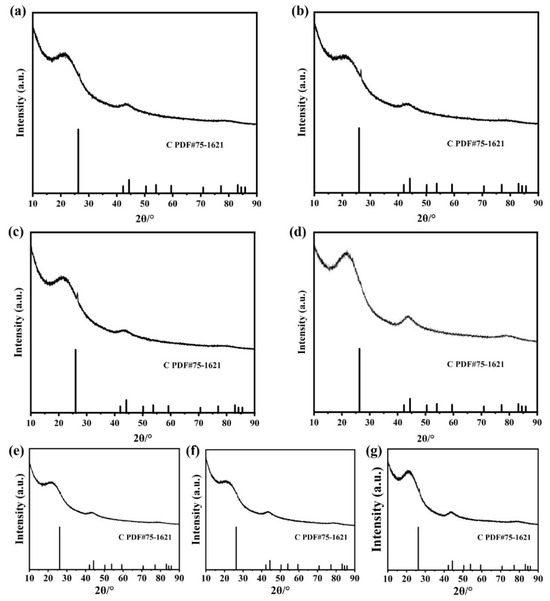

As shown in the XRD patterns (Figure 2), no detectable diffraction peaks corresponding to Pt-La, Pt-Nd, Pt-Gd, Pt-Dy, Pt-Ho, Pt-Yb, or Pt-Sc alloy phase were detected in any of the Pt-RE/C samples (Figure 2a–g). This suggests that the Pt-RE SBCs species are highly dispersed on the carbon support. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping (Figure S1a–g) further confirms the homogeneous distribution of Pt and the respective rare earth elements within individual clusters, supporting the formation of SBCs structures.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of (a) Pt-La/C, (b) Pt-Nd/C, (c) Pt-Gd/C, (d) Pt-Dy/C, (e) Pt-Ho/C, (f) Pt-Yb/C, and (g) Pt-Sc/C.

To investigate the influence of the support on the catalytic behavior of Pt-RE alloys, Pt-Sc alloys supported on CeO2 were also prepared. Figure S2 shows the XRD patterns of Pt-RE SBCs on different supports, which showed that no obvious diffraction peak was observed in the XRD pattern of Pt-Sc/C and Pt-Sc/CeO2, due to the low content and highly dispersed nature of Pt-Sc clusters/nanoparticles. EDS mapping (Figure S3d–i) further verifies the uniform co-distribution of Pt and Sc in both Pt-Sc/C and Pt-Sc/CeO2 catalysts.

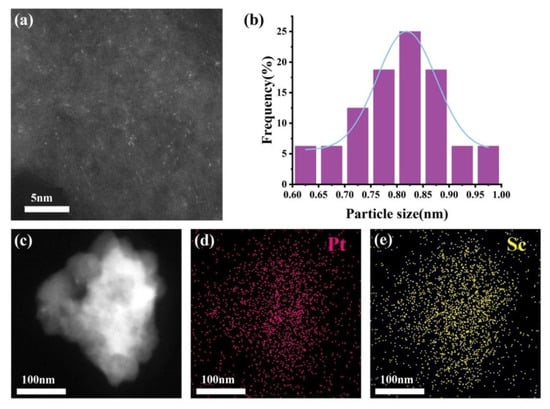

The morphology and cluster size distribution of the Pt-Sc SBCs catalyst was analyzed by TEM (Figure 3). The catalyst exhibits uniform dispersion of clusters on the carbon support without notable agglomeration, underscoring the efficacy of the synthetic approach. The cluster size distributions are narrow, predominantly falling in the range of 0.6–1.0 nm, with all particles being below 1 nm. The high dispersion an ultra-small size of the Pt-RE SBCs are advantageous for catalytic performance, as they provide a high density of active sites and facilitate strong metal–support interactions. The EDS spectra (Figure 3c–e) clearly show the uniform distribution of Pt and Sc elements in the catalyst.

Figure 3.

(a) STEM images of Pt-Sc/C, (b) the size distribution of Pt-Sc/C, (c–e) and the EDS elemental mapping images of Pt-Sc/C.

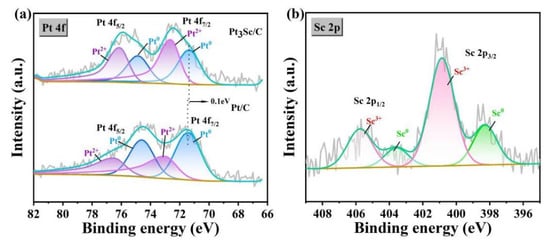

The electronic structure of Pt and Sc in Pt-Sc SBCs was studied by XPS to elucidate the electronic interaction between the two elements and its effect on catalytic performance. Figure 4a displays the Pt 4f XPS spectra and corresponding deconvolution results of Pt-Sc and Pt/C. The fitting reveals that binding energy of the Pt 4f7/2 in the metallic state of Pt-Sc is approximately 0.1 eV lower than that of in Pt/C, indicating electron transfer from Sc to Pt in the SBCs. The presence of both metallic and oxidized states of Sc further supports the occurrence of electron transfer from Sc to Pt. This charge redistribution can be attributed to the significant electronegativity difference between Pt (2.28) and Sc (1.36), which weakens the electron binding in the Pt 4f orbital. Such electronic modulation is likely to lower the d-band center of Pt, potentially enhancing its catalytic activity.

Figure 4.

(a) Pt 4f XPS spectra of Pt-Sc/C and Pt/C, (b) Sc 2p XPS spectra of Pt-Sc.

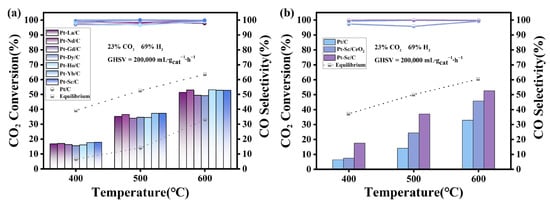

The catalytic performance of the synthesized Pt-RE SBC series was evaluated to determine the effect of SBCs. Figure 5a shows the CO2 conversion and CO selectivity. The Pt-RE SBC catalysts exhibit excellent catalytic performance in the RWGS reaction. Compared with the conventional Pt/C, the CO2 conversion of Pt-RE catalysts occurs approximately at 500 °C, while maintaining ultra-high CO selectivity between 96% and 100%. Among them, Pt-Sc showed the best performance, achieving a CO2 conversion of 37.28% with a CO selectivity of 99.97%. The electronegativities of Pt and Sc are 2.28 and 0.95, respectively. Due to the significant difference in electronegativity, electron transfer from Sc to Pt occurs in Pt-Sc clusters. As indicated by XPS, the lower Pt 4f7/2 binding energy in Pt-Sc and the presence of both metallic and oxidized Sc suggest electron transfer from Sc to Pt. The electron transfer process induced by the electronegativity difference effectively modulates the charge density and local electronic structure of the Pt active center, typically resulting in a downshift of its d-band center [42]. This modulates the charge density of Pt atoms, reducing the bond energy between the catalyst surface and adsorbates, thereby increasing CO2 conversion and CO selectivity [35,36]. The presence of oxidized Sc on the surface also introduces a Pt-Sc2O3 interface, which promotes CO2 activation and dissociation (C-O bond cleavage). This interface effect not only improves CO2 conversion, but also directs the reaction pathway to favor CO production, significantly suppressing methane formation by inhibiting over-hydrogenation [12,19]. Under the reaction conditions of 500 °C, the synthesized series of Pt-RE SBCs exhibit slightly different CO2 catalytic conversion performance, and the order is as follows: Pt-Sc (37.28%) > Pt-Yb (37.24%) > Pt-Nd (36.51%) > Pt-La (35.29%) > Pt-Ho (34.58%) > Pt-Dy (34.45%) > Pt-Gd (33.97%).

Figure 5.

(a) The CO2 conversion and CO selectivity of the catalysts were investigated. (b) The CO2 conversion and CO selectivity of Pt-RE on different carriers.

To examine the effect of support on Pt-RE SBCs catalysis, Pt-Sc was synthesized on different supports and tested by in RWGS reaction. Figure 5b compares the CO2 conversion and CO selectivity of Pt-Sc on different supports. Both Pt-Sc/CeO2 and Pt-Sc/C show improved CO2 conversion compared to Pt/C, along with high CO selectivity (95–100%), underscoring the beneficial role of Sc doping in Pt-based catalysts. However, Pt-Sc/CeO2 exhibits lower CO2 conversion than Pt-Sc/C. Figure S3b,c shows the particle size distribution of Pt-Sc/C and Pt-Sc/CeO2, respectively. Statistical analysis indicates that when CeO2 is used as the support, the Pt-Sc nanoparticles exhibit a larger average size and a broader size distribution. The increased particle size likely reduces the number of active sites and lowers the surface energy, thus affecting the catalytic performance. Although the oxygen storage/release capacity of CeO2 may facilitate CO2 activation, the larger particle size (15.95 nm) limits the number of active sites, which may be the main reason for the lower activity enhancement for Pt-Sc/CeO2. Moreover, larger metal particles are more prone to sintering, which can further compromise catalytic activity and stability.

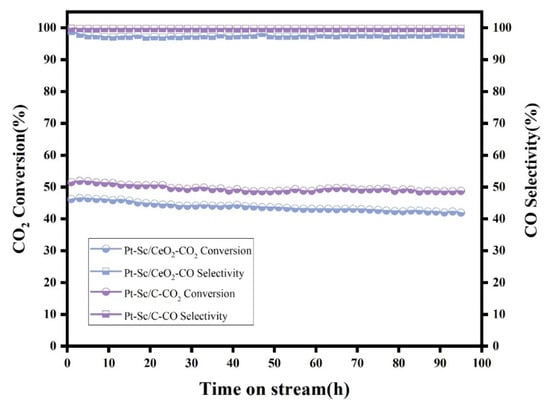

The stability of the catalysts was evaluated at 600 °C, and the results are presented in Figure 6. Both Pt-Sc/C and Pt-Sc/CeO2 show excellent stability. The CO selectivity of both samples remained nearly unchanged over 100 h, while the CO2 conversion remained relatively stable. After 100 h, the CO2 conversion of Pt-Sc/C decreased by approximately 3.3%, and that of Pt-Sc/CeO2 decreased by about 4.3%. The high stability of Pt-Sc SBCs can be attributed to the strong metal–metal bond energy between Pt and Sc induced by the high formation energy of the Pt-Sc alloy. Due to the high thermal stability of noble metal–rare earth alloys, it can maintain structural integrity in the reaction environment at 600 °C, thus directly inhibiting the migration and agglomeration of clusters. The rare earth component optimizes the electronic structure of Pt through electronic effects and directly participates in the anchoring and activation of oxygen atoms in CO2 via its inherent Lewis acidity or oxygen storage/release capacity. This bifunctional or multifunctional synergy enables the originally inert linear CO2 molecule to undergo bending and dissociation with a lower energy barrier, thereby being efficiently converted into the target product [42]. The role of platinum lies primarily in efficiently initiating H2O dissociation, mediating the redox cycle, and optimizing the adsorption equilibrium of reaction intermediates through its tunable electronic structure [43]. The incorporation of rare earth elements primarily strengthens the adsorption of CO2 molecules on Pt and enhances the direct cleavage of C=O bonds through electronic and geometric effects, rather than shifting toward the formate pathway requiring sequential hydrogenation. These clusters tend to occupy high-energy defect sites on the support surface. This interaction resembles “atomic pinning,” anchoring the metal atoms at specific locations, which significantly increases the activation energy for their surface migration and prevents their movement and aggregation even under high-temperature conditions. Highly conductive carbon materials can donate a small number of electrons to Pt, forming electron-enriched Pt. This helps weaken CO adsorption and prevents CO poisoning.

Figure 6.

Stability test of Pt-Sc/C and Pt-Sc/CeO2 at 600 °C for 100 h.

In bimetallic catalyst systems, the reaction mechanism primarily depends on either “spatial functional separation and coupling” or “electronic and structural modulation at the atomic level.” Both are effective strategies for enhancing the RWGS performance of Pt-based catalysts, yet they correspond to fundamentally different characteristics of active sites, microscopic reaction pathways, and principles of catalyst design. In practical investigations, these two mechanisms may even coexist or compete on the same catalyst [44,45].

4. Conclusions

In this study, a series of Pt-RE SBCs catalysts with high activity, selectivity, and stability were successfully developed for a RWGS reaction. The introduction of rare earth elements effectively regulates the electronic structure of Pt, leading to enhanced CO2 conversion and suppression of CO methanation. The influence of different supports on the catalytic performance of Pt-RE SBCs was also investigated. Compared with CeO2, carbon supports promote more uniform dispersion and the formation of ultra-small SBCs, thereby improving catalytic performance. This work provides new insights into the design of efficient and stable RWGS catalysts, highlighting the key role of the synergistic effect at the Pt-RE SBC interface and importance of support selection in CO2 utilization. Rare earth resources are limited and precious. Therefore, a key research objective is to reduce the usage of rare earth elements without compromising catalytic performance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nano16010077/s1, Figure S1: The EDS elemental mapping images of the catalysts (a–c) Pt-La/C, (d–f) Pt-Nd/C, (g–i) Pt-Gd/C, (j–l) Pt-Dy/C, (m–o) Pt-Ho/C, (p–r) Pt-Yb/C used in this study; Figure S2: XRD patterns of Pt-Sc/C and Pt-Sc/CeO2; Figure S3: TEM images of (a) Pt/C, (b) Pt-Sc/C with illustrations of size distribution, (c) Pt-Sc/CeO2 with illustrations of size distribution. EDS elemental spectra of the catalysts (d–f) Pt-Sc/C, (j–i) Pt-Sc/CeO2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L. and F.L.; methodology, Z.L. and Q.L.; software, Z.L. and C.S.; validation, Z.L., C.S. and S.S.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, Z.L., C.S. and S.S.; resources, Z.L., C.S. and S.S.; data curation, Z.L. and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L. and Q.L.; visualization, Z.L. and S.S.; supervision, Q.L. and F.L.; project administration, Q.L. and F.L.; funding acquisition, Q.L. and F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA1601004) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (B250201099).

Data Availability Statement

All data needed to support the conclusions in the paper are presented in the manuscript and/or the Electronic Supplementary Material. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

All support for our work is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, W.; Sun, J.; Wang, H.; Cui, X. Recent Advances in Hydrogenation of CO2 to CO with Heterogeneous Catalysts Through the RWGS Reaction. J. Chem. Asian 2024, 19, e202300971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.; Villen-Guzman, M.; Rodriguez-Maroto, J.; Paz-Garcia, J. Comparing CO2 Storage and Utilization: Enhancing Sustainability through Renewable Energy Integration. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A.; Ali, M.; Patil, S.; Aljawad, M.; Mahmoud, M.; Al-Shehri, D.; Hoteit, H.; Kamal, M.S. Comprehensive review of CO2 geological storage: Exploring principles, mechanisms, and prospects. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2024, 249, 104672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Haupt, J.; Werra, M.; Gernuks, S.; Wiegel, M.; Rueggeberg, M.; Cerdas, F.; Herrmann, C. Life cycle assessment of carbon dioxide removal and utilisation strategies: Comparative analysis across Europe. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 2024, 211, 107837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoy, N.; Steubing, B.; Guinée, J. Ex-ante life cycle assessment of polyols using carbon captured from industrial process gas. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 5526–5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamkeng, A.; Wang, M.; Hu, J.; Du, W.; Qian, F. Transformation technologies for CO2 utilisation: Current status, challenges and future prospects. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 409, 128138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Ding, X.; Sun, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y. Safe and efficient catalytic reaction for direct synthesis of CO from methylcyclohexane and CO2. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmanpour, A.; Signorile, M.; Kröcher, O. Recent progress in syngas production via catalytic CO2 hydrogenation reaction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 295, 120319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, X.; Xie, H.; Chen, S.; Zhang, G.; Xu, B.; Zhou, G. Highly dispersed mesoporous Cu/γ-Al2O3 catalyst for RWGS reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 14884–14895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liang, L.; Yuan, H.; Liu, H.; Wu, P.; Fu, M.; Wu, J.; Chen, P.; Qiu, Y.; Ye, D.; et al. Reciprocal regulation between support defects and strong metal-support interactions for highly efficient reverse water gas shift reaction over Pt/TiO2 nanosheets catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 298, 120507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, M.; Ma, P.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, K.; Kuang, Q.; Xie, Z. Atomically dispersed Pt/CeO2 catalyst with superior CO selectivity in reverse water gas shift reaction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 291, 120101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goguet, A.; Meunier, F.; Breen, J.; Burch, R.; Petch, M.; Ghenciu, A. Study of the origin of the deactivation of a Pt/CeO2 catalyst during reverse water gas shift (RWGS) reaction. J. Catal. 2004, 226, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cheng, W.; Lin, S. Study of reverse water gas shift reaction by TPD, TPR and CO2 hydrogenation over potassium-promoted Cu/SiO2 catalyst. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2003, 238, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, L.; Chen, Z.; Wen, J.; Zhong, W.; Zou, S.; Fu, M.; Chen, L.; Ye, D. Highly efficient Cu/CeO2-hollow nanospheres catalyst for the reverse water-gas shift reaction: Investigation on the role of oxygen vacancies through in situ UV-Raman and DRIFTS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 516, 146035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Pang, S.; Sulmonetti, T.; Su, W.; Le, J.; Hwang, B.; Jones, C. Synergy between Ceria Oxygen Vacancies and Cu Nanoparticles Facilitates the Catalytic Conversion of CO2 to CO under Mild Conditions. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 12056–12066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, A.; Irankhah, A.; Aghamiri, S. Catalytic activity of rare earth and alkali metal promoted (Ce, La, Mg, K) Ni/Al2O3 nanocatalysts in reverse water gas shift reaction. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2019, 45, 5125–5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Kawamoto, K. Preparation of mesoporous CeO2 and monodispersed NiO particles in CeO2, and enhanced selectivity of NiO/CeO2 for reverse water gas shift reaction. Mater. Res. Bull. 2014, 53, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wu, T.; Xie, H.; Zheng, X. Effects of structure on the carbon dioxide methanation performance of Co-based catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 10012–10018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattel, S.; Yan, B.; Chen, J.; Liu, P. CO2 hydrogenation on Pt, Pt/SiO2 and Pt/TiO2: Importance of synergy between Pt and oxide support. J. Catal. 2016, 343, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.; Kovarik, L.; Szanyi, J. Heterogeneous catalysis on atomically dispersed supported metals: CO2 reduction on multifunctional Pd catalysts. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 2094–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duyar, M.; Ramachandran, A.; Wang, C.; Farrauto, R. Kinetics of CO2 methanation over Ru/γ-Al2O3 and implications for renewable energy storage applications. J. CO2 Util. 2015, 12, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Zhu, Z.; Li, C.; Xiao, M.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Chu, M.; Genest, A.; et al. Ru-Catalyzed Reverse Water Gas Shift Reaction with Near-Unity Selectivity and Superior Stability. ACS Mater. Lett. 2021, 3, 1652–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, T.; Saju, S.; Raveendran, S. Survey of heterogeneous catalysts for the CO2 reduction to CO via reverse water gas shift. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 12, 281−316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Tang, X.; Qiu, S.; Wang, L.; Hao, L.; Yu, Y. Stable CuIn alloy for electrochemical CO2 reduction to CO with high-selectivity. Mater. Today Phys. 2023, 33, 101050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Park, G.; Arshad, M.; Zhang, C.; Kim, S.; Kim, S. Active and selective reverse water-gas shift reaction over Pt/Na-Zeolite catalysts. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 66, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Bao, R.; Sun, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, C. Silica-supported Pt-In intermetallic alloy for low-temperature reverse water-gas shift reaction. Mol. Catal. 2025, 574, 114890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yu, Y.; Chen, L.; Cheng, T.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Harada, M.; Ishihara, A.; Wang, Y. Indium oxide supported Pt-In alloy nanocluster catalysts with enhanced catalytic performance toward oxygen reduction reaction. J. Power Sources 2020, 446, 227332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Nuzzo, R.; Frenkel, A.; Liu, P.; Gersappe, D. Revealing Intermetallic Active Sites of PtNi Nanocatalysts for Reverse Water Gas Shift Reaction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 22067–22075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Frenkel, A.; Liu, P. Rationalization of promoted reverse water gas shift reaction by Pt3Ni alloy: Essential contribution from ensemble effect. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 154, 014702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Yu, H.; Li, K.; Li, H.; Yin, H. Pt-Fe Bimetallic Nanoparticles Confined in Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanoshells as a Catalyst for the Reverse Water-Gas Shift Reaction. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 10315–10325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Bootharaju, M.; Kim, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, R.; Xu, J.; Hyeon, T.; Wang, X.; et al. Synergistic Interactions of Neighboring Platinum and Iron Atoms Enhance Reverse Water-Gas Shift Reaction Performance. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 2264–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, N.; Wang, H.; Zhang, T. Synthesis of Pt-Rare Earth Metal Alloys and Their Applications. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202402750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Numan, M.; Sudalai, A.; Jo, C.; Park, S. Ethane Oxidative Dehydrogenation over Pt-Rare Earth Intermetallic Compounds with CO2 as Soft Oxidant. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 10382–10390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, R.; Kim, J.; Jo, C.; Han, S.; Kim, J.; Park, H.; Han, J.; Shin, H.; Shin, J. Rare-earth–platinum alloy nanoparticles in mesoporous zeolite for catalysis. Nature 2020, 585, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanady, J.; Leidinger, P.; Haas, A.; Titlbach, S.; Schunk, S.; Schierle-Arndt, K.; Crumlin, E.; Wu, C.; Alivisatos, A. Synthesis of Pt3Y and other early–late intermetallic nanoparticles by way of a molten reducing agent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5672−5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Z.; Li, Q.; Du, Y.; Liu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Luo, F. Activating PtRu with rare earth alloying for efficient electrocatalytic methanol oxidation reaction. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2025, 15, 2473–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacrida, P.; Escudero-Escribano, M.; Verdaguer-Casadevall, A.; Stephensa, I.; Chorkendorff, I. Enhanced activity and stability of Pt-La and Pt-Ce alloys for oxygen electroreduction: The elucidation of the active surface phase. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 4234–4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, B.; Sun, C.; Sun, X.; Li, Z.; Du, Y.; Liu, J.; Luo, F. Enhanced Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution Reaction via Electronic Structure Regulation: Activating PtRh with Rare Earth Tm Alloying. Small 2024, 20, 2400662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Sun, C.; Fu, H.; Zhang, S.; Sun, X.; Liu, J.; Du, Y.; Luo, F. Enhanced Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution Reaction through Lanthanide-Modified Rhodium Intermetallic Catalysts. Small 2024, 20, 2307052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidales, A.; Omanovic, S.; Li, H.; Hrapovic, S.; Tartakovsky, B. Evaluation of biocathode materials for microbial electrosynthesis of methane and acetate. Bioelectrochemistry 2022, 148, 108246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Corma, A. Metal Catalysts for Heterogeneous Catalysis: From Single Atoms to Nanoclusters and Nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 4981–5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero-Escribano, M.; Malacrida, P.; Hansen, M.; Vej-Hansen, U.; Velázquez-Palenzuela, A.; Tripkovic, V.; Schiotz, J.; Rossmeisl, J.; Stephens, I.; Chorkendorff, I. Tuning the activity of Pt alloy electrocatalysts by means of the lanthanide contraction. Science 2016, 352, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidales, A.; Semai, M. Platinum nanoparticles supported on nickel-molybdenum-oxide for efficient hydrogen production via acidic water electrolysis. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1290, 135956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szamosvölgyi, A.; Pitó, A.; Efremova, A.; Baán, K.; Kutus, B.; Suresh, M.; Sápi, A.; Szenti, I.; Kiss, J.; Kolonits, T.; et al. Optimized Pt–Co Alloy Nanoparticles for Reverse Water–Gas Shift Activation of CO2. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 9968–9977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Kim, D.; Hong, S.; Kim, T.; Kim, K.; Park, J. Bimetallic Synergy from a Reaction-Driven Metal Oxide-Metal Interface of Pt-Co Bimetallic Nanoparticles. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 13777–13785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.