Abstract

The temperature-dependent photoluminescence of CsPbBr3/SiO2 and CsPbI3/SiO2 nanocrystals was investigated to understand the thermal stability of SiO2 encapsulation. At increased temperature, intensity quenching, linewidth broadening, energy level shift, and decay dynamics were evaluated as quantified parameters. Comprehensive analysis of these parameters supports that CsPbI3/SiO2 nanocrystals show a stronger interaction with phonons compared with CsPbBr3/SiO2 nanocrystals. Despite SiO2 encapsulation, we conclude that trapping states are still present and the degree of localization can be characterized in terms of short-lived decay time and thermal activation energy.

1. Introduction

Lead halide perovskites have emerged as promising, high-performance semiconductor materials for optoelectronic applications such as solar cells [1,2,3], photodetectors [3,4,5], light-emitting diodes (LEDs) [3,6,7], lasers [8,9,10], and photocatalysts [11,12]. Because of their remarkable properties, including high photoluminescence (PL) quantum yield, narrow emission linewidth, long carrier diffusion length, and tunable band gap, they have been widely investigated for next-generation device applications. In particular, all inorganic CsPbX3 perovskites (X = Cl−, Br−, I−) have attracted considerable interest in recent years due to their robust thermal stability compared to their hybrid organic–inorganic counterparts [3,5,7]. However, CsPbX3 nanocrystals (NCs) still show structural, interfacial, and environmental degradation due to their soft ionic lattices and strong interactions with moisture and polar solvents [3,13,14]. In order to solve these problems, considerable effort has been devoted to improving stability such as compositional or surface engineering, matrix, and device encapsulation. In particular, the encapsulation of perovskite NCs with an appropriate inorganic protective layer such as SiO2 [14,15,16,17], Cs4PbBr6 [18,19], Al2O3 [14,20], TiO2 [21,22], and ZrO2 [23,24] has been a highly effective and straightforward strategy for improving their stability. Among them, SiO2 coating is particularly advantageous due to its excellent barrier properties against moisture and oxygen, which are the main causes of perovskite degradation. Moreover, its optical transparency across the visible spectrum ensures that they are less vulnerable to photo-degradation, making it highly suitable for optoelectronic applications [14,16,17].

For light harvesting applications, one of the most crucial optoelectronic properties of lead halide perovskite is their optical band gap. It is well known that the direct band gap of perovskites exhibits an atypical temperature dependence [25,26,27]. The conduction band minimum (CBM) of perovskites lies in the hybridized anti-bonding orbitals of the Pb 6p orbitals and the outer p orbitals of halide (5p for I, for Br, and for Cl), and the valence band maximum (VBM) lies in the hybridized anti-bonding states of the Pb orbitals and the same halide p-orbital as that for the CBM. Regarding these electronic structures, the temperature-dependent band gap shift of perovskites is explained in terms of electron–phonon interactions in the corner-sharing [PbX6]4− octahedra [28] as well as thermal expansion.

Temperature dependence in single-crystal hybrid perovskites is also considered a crucial issue for inverse temperature crystallization and device applications [29,30,31]. Beyond encapsulation strategies for nanocrystals and polycrystalline films, single-crystal perovskites have emerged as a particularly promising materials for enhanced stability and reproducibility because the absence or high reduction of grain boundaries can suppress defect-assisted degradation mechanisms and ion-migration-related instabilities. Rapid growth routes, such as inverse temperature crystallization [29], have enabled high-quality bulk single crystals with markedly improved optoelectronic quality, motivating stability-oriented device concepts based on single-crystalline forms. More recently, low-dimensional single-crystal perovskites (i.e., 2D single-crystal hybrids) have also been actively investigated, leveraging their ordered quantum-well-like structures and improved environmental tolerance [30]. Thus, the stabilizat/ion of perovskite NCs via inorganic encapsulants can be considered a complementary approach that traces the dominant surface-mediated degradation channels specific to nanoscale systems [31].

Despite the great deal of work on SiO2-coated CsPbX3 perovskite NCs [32,33,34,35], their temperature dependence of the PL spectrum has rarely been addressed [36,37]. Among the CsPbX3 perovskite family, most of the work has focused on green CsPbBr3 due to the outstanding quantum yield and thermal stability, and recent work has analyzed the PL spectrum of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs for increasing temperature [36]. However, the quantified parameters were not compared with other CsPbX3 perovskites. The quenching effect of CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs was observed in a limited temperature range (25∼253 °C), and only intensity suppression was discussed [38,39]. The PL spectrum of CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs has never been analyzed at low temperatures, and the decay dynamics remain unknown.

In this work, we investigated the temperature-dependent PL spectrum of as-prepared CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs and CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs, which both show enhanced stability compared with the uncoated bare NCs. As the temperature increased from 4 K to 300 K, the PL spectrum was interpreted comprehensively by comparing intensity quenching, linewidth broadening, energy level shift, and decay dynamics with quantified parameters. These results enabled us to evaluate the trapped states, and the atypical temperature dependence was explained via thermal exciton dissociation, lattice expansion, and exciton–phonon interaction.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Material Preparation and Synthesis

We used the commercial products of Cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3, reagent Plus, 99%), 1-octadecene (ODE, technical grade, 90%), oleic acid (OA, technical grade, 90%), oleylamine (OAm, technical grade, 70%), toluene (anhydrous, 99.8%), (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES, 99%), lead iodide (PbI2, 99%), methyl acetate (MeAc, reagent Plus, 99%), and ethyl acetate (EtAc, ACS reagent, ≥99.5%) from SigmaAldrich (Schnelldorf, Germany), and lead bromide (PbBr2, 99.998% metals basis) from Alfa Aesar (Shanghai, China). All chemicals were used as purchased without further purification.

The Cs-oleate precursor was prepared by dissolving Cs2CO3 (0.18 g) and oleic acid (0.75 mL) in 1-octadesene (7.5 mL). The mixture was stirred under vacuum and degassed at 120 °C for 1 h until a clear solution was obtained. For the synthesis of CsPbBr3 NCs, PbBr2 (0.07 g), oleic acid (0.5 mL), and oleylamine (0.5 mL) were dissolved in 1-octadescene (10 mL) and degassed at 120 °C for 40 min. The reaction flask was then filled with nitrogen, and the temperature was increased to 150 °C. Subsequently, 0.5 mL of the as-prepared Cs-oleaste solution was rapidly injected. After injection, the reaction mixture was immediately quenched via cooling in an ice-water bath. CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs were synthesized using the same procedure as that for CsPbBr3 NCs, except that APTES were used to substitute oleylamine. For the synthesis of CsPbI3 NCs, PbI2 (0.087 g), oleic acid (1 mL), oleylamine (1 mL), and 1-octadecene (10 mL) were added to a three-neck flask and degassed under vacuum at 100 °C for 50 min. The temperature was then raised to 140 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere, followed by the rapid injection of 0.5 mL of the Cs-oleate solution. The reaction was terminated by cooling the flask in an ice-water bath. CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs were prepared following the same procedure as that for CsPbI3 NCs, with APTES substituted for oleylamine.

2.2. Characterization

UV-Vis absorption spectra were measured using a Spectramax M5 Microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), and energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS) compositional mapping images were also taken using a field emission transmission electron microscope (FETEM) operated at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were obtained. The temperature-dependent PL spectrum was obtained usinga closed-cycled cryostat (CCR), and time-resolved PL (TRPL) decay profiles were obtained using a time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) system with an instrument response function (IRF) of pulsed excitation (30 ps).

3. Results and Discussion

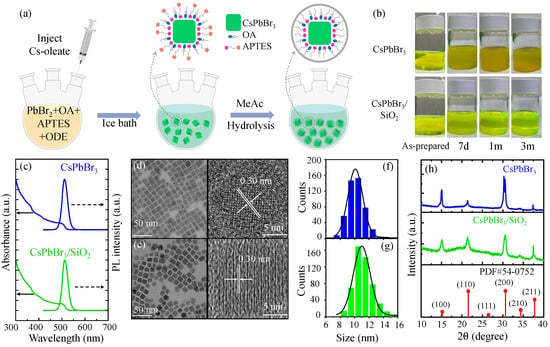

Figure 1a shows the three main processes involved in synthesizing CsPbBr3/SiO2 nanocrystals (NCs). Monodisperse CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs are prepared using a modified one-pot hot-injection approach, where (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES) is used as a substitution for oleylamine (OAm) and acted as the capping agent and SiO2 shell precursor [15,32,34]. With this method, the Cs-oleate precursor solution was quickly injected into a preheated mixture of PbBr2, oleic acid (OA), APTES, and 1-octadecene (ODE) at 150 °C in a three-neck flask. Upon injection, CsPbBr3 NCs nucleate and grow rapidly in solution. The reaction mixture is rapidly cooled to room temperature in order to stop further crystal growth and stabilize the NCs using an ice-water bath. For purification, the reaction mixture was washed with methyl acetate (MeAc), facilitating the interaction between APTES and the surface of the perovskite nanocrystals. Following this step, APTES underwent hydrolysis in the presence of moisture, where its ethoxy (-SiOC2H5) groups hydrolyzed into silanol (-SiOH) groups. Then, SiOH reacted with SiOC2H5 and/or other SiOH to form Si-O-Si cross-linked networks. This process resulted in the encapsulation of the NCs within a protective silica matrix, which enhanced their stability against environmental degradation [34]. For the synthesis of CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs, we followed a similar procedure with PbI2 substituting PbBr2. Minor variations, such as synthesis temperature and the number of APTES, were previously mentioned in the Section 2.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of the synthesis process of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs. (b) As-prepared CsPbBr3 and CsPbBr3/SiO2 toluene solution under day light following preservation in a refrigerator at 4 °C for 0 days, 7 days, 30 days (1 month), and 3 months. (c) PL and absorption spectrum of CsPbBr3 and CsPbBr3/SiO2. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of CsPbBr3 NCs (d) and CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs (e), and the corresponding high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images are also shown. (g) The size distribution histograms of CsPbBr3 NCs (f) and CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs. (h) X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of CsPbBr3 (blue) and CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs (green) compared with the standard pattern for cubic CsPbBr3 (PDF#54-0752).

As shown in Figure 1b, photographs of CsPbBr3 and CsPbBr3/SiO2 NC solutions in toluene were taken to monitor their degradation over time. Both of the NC solutions were stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C. It is evident that both fresh perovskite solutions were transparent with a yellow-green color. However, after 7 days, the CsPbBr3 NC solution became opaque with significant aggregation. In contrast, the CsPbBr3/SiO2 solution remained transparent. Furthermore, after 30 days (1 month) and 3 months, the CsPbBr3/SiO2 solution was still transparent, while the CsPbBr3 solution continued to aggregate over time. The improved stability of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs can be attributed to the presence of the SiO2 shell, which passivates the perovskite NCs from the surface dangling bonds [16]. As a result, aggregation is suppressed, and solution stability is maintained over a long period.

Figure 1c shows the PL and absorption spectra of CsPbBr3 NCs and CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs, where the central PL wavelengths and linewidth (FWHM) of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs and CsPbBr3 NCs are observed to be 513 nm/511 nm and 28.4 nm/27.8 nm, respectively. A uniform size distribution was observed in both TEM images of CsPbBr3 NCs (Figure 1d) and CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs (Figure 1e), and the HRTEM images also show a clear lattice spacing of 0.30 nm, which corresponds to the (200) plane of cubic-phase CsPbBr3 [40]. These results indicate that the crystal integrity of CsPbBr3 NCs is well preserved after silica coating. Because the shapes of both CsPbBr3 NCs and CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs are rectangular rather than square, the diagonal length of the rectangles was measured to determine the size distribution. In Figure 1f and Figure 1g, the diagonal size distribution histograms of CsPbBr3 NCs (10.2 ± 1.1 nm) and CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs (11.3 ± 1.4 nm) are shown, respectively. Recent work observed a slight size expansion when CsPbBr3 NCs are coated with SiO2 [36,37]. Although the increased size causes a redshift as a result of the decreased confinement energy, the energy difference between CsPbBr3 NCs and CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs is barely seen.

To confirm the crystal structure of CsPbBr3 NCs and CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs, their X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were analyzed and compared with the standard PDF card, as shown in Figure 1h. The CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs exhibit strong diffraction peaks at 2 = 15.2°, 21.5°, 30.8°, 34.5°, and 37.8°, corresponding to the planes of (100), (110), (200), (210), and (211) in cubic CsPbBr3 (PDF#54-0752) [35], respectively. It is also noticeable that no structural phase transition was observed after silica shell coating, and this result indicates that the crystal integrity of CsPbBr3 NCs was well preserved. These XRD results are consistent with the high-resolution TEM images shown in the insets of Figure 1d,e, which confirm the structural stability of the CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs. Although the diffracted peak intensity of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs appears decreased compared with that of bare CsPbBr3 NCs, this is mainly attributed to the incorporation of an amorphous SiO2 fraction, which dilutes the crystalline perovskite content and increases diffuse background scattering. It is important that the unchanged peak positions and the absence of additional reflections confirm that the cubic CsPbBr3 crystal phase was preserved after encapsulation.

The atomic-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) images, which were acquired in a high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) mode (Figure S1 in the Supplementary Materials), revealed that CsPbBr3 NCs were embedded within the silica shell. Additionally, the soft edges observed in the TEM images of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs further indicated the presence of an ultrathin SiO2 shell [26]. The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum (Figure S2 in the Supplementary Materials) provided additional evidence for the core–shell structure of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs. The sharp peak at approximately 1128 cm−1 was attributed to the stretching vibration of the Si–O–Si bond [26]. Moreover, the peak at around 1033 cm−1 corresponded to the vibration of the Si–O–C bond. The detected peaks at approximately 2854 cm−1 and 2923 cm−1 were assigned to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of C–H, respectively.

As demonstrated in the case of CsPbBr3, SiO2 encapsulation contributed to improved stability. Given these promising results, CsPbI3 NCs were also encapsulated with SiO2 to examine whether a similar stabilization effect could be achieved. It is known that the ammonium ligands of CsPbI3 NCs are easily lost due to the weak acid–base interactions between I and oleylammonium, resulting in fast agglomeration and an undesired phase transformation from cubic to orthorhombic. Their thermodynamically unstable α-phase also causes rapid degradation. To revolve these unstable issues in CsPbI3 NCs, many strategies were known to improve its stability such as introducing organolead compound trioctylpho sphine-PbI2 (TOP-PbI2) as the reactive precursor [41], utilizing ZnI2 as a co-precursor and passivating agent in the synthesis [42].

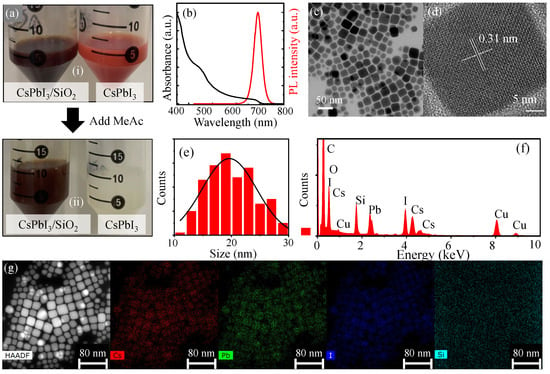

As shown in Figure 2a, two solutions were prepared: a brown-colored CsPbI3/SiO2 NC solution and a burgundy-colored pristine CsPbI3 NC solution. To remove excess ligands and byproducts from the reaction, both solutions underwent a purification step using methyl acetate. During this process, the pristine CsPbI3 NC solution was found to show rapid degradation and changed color from burgundy to white, indicating structural instability. In contrast, the CsPbI3/SiO2 NC solution retained its original brown color, demonstrating that the SiO2 shell effectively prevented degradation (Figure S6 in the Supplementary Materials). However, CsPbI3 NCs exhibited a distinct behavior compared to CsPbBr3 NCs, undergoing rapid PL quenching upon purification. This inhibits comparative studies on their optical properties.

Figure 2.

(a) A total of 5 mL of as-prepared CsPbI3 and CsPbI3/SiO2 pristine solution (i), and the two pristine perovskite solution after adding 5 mL methyl acetate into 5 mL (ii), where the insets are photographs of CsPbI3/SiO2 toluene solution under day light, respectively. (b) PL and absorption spectra of CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs. Given TEM (c) and HRTEM (d) images of CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs, the size distribution histogram was obtained (e) as well as the lattice spacing. (f) The energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrum of CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs. (g) For an STEM-HAADF image of CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs, the elemental mapping images of Cs, Pb, I, and Si were compared.

The stability of CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs was further confirmed, as no noticeable quenching was observed over time. To investigate their optical properties, the absorption and PL spectra of CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs were measured as shown in Figure 2b. The absorption spectrum exhibited two prominent peaks near 680 nm and 450 nm. The PL spectrum showed a peak centered around 690 nm with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 39 nm, which is broader than that of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs (28.4 nm). The relatively narrow FWHM value also indicates a uniform size distribution of CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs. This observation was further supported by the TEM image in Figure 2c, which visually confirms the uniform morphology of the nanocrystals. The HRTEM image in Figure 2d also shows clear lattice fringes of CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs, indicating their high crystalline quality. The measured lattice spacing distance of 0.31 nm corresponds to the (200) planes of cubic-phase CsPbI3, further confirming the structural integrity of the encapsulated NCs. The corresponding size distribution analysis reveals that the CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs have an average size of approximately 20.3 nm with a standard deviation of ±4.4 nm, as shown in Figure 2e.

Figure 2f shows the energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrum of CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs, while Figure 2g displays the STEM-HAADF image and elemental mapping images, confirming the successful formation of the silica shell around CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs. For further verification of a core–shell structure, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was performed (Figure S2 in Supplementary Materials), revealing strong peaks at 1037 cm−1 and 1070 cm−1, which correspond to the stretching vibrations of Si-O-Si [39] and Si-O-C [43] bonds, respectively. To assess the effect of the silica shell on the crystal structure of CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs, X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were conducted and compared with the reference pattern from ICSD no. 181288 (Figure S4 in the Supplementary Materials). The XRD peaks of CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs closely match those of ICSD no. 181288 within the range of 2 = 10 °–40°, confirming that CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs retain a cubic phase.

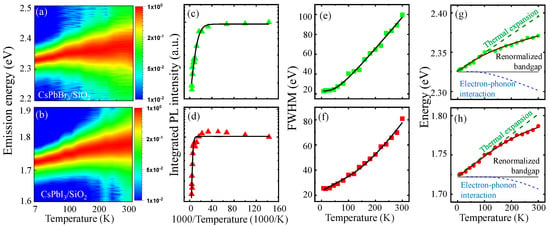

Although the temperature-dependent PL spectrum in perovskites NCs was extensively investigated [25,26,27,28,36,37,38], a systematic study of the core–shell perovskite NCs is still necessary. In Figure 3a,b, the PL intensity of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs and CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs was obtained for spectrum and temperature, respectively. The integrated PL intensity of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs (Figure 3c) and CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs (Figure 3d) is also shown for reciprocal temperature (1000/T) to evaluate thermal activation. With increasing temperature, thermally activated non-radiative recombination processes, leading to a gradual decrease in PL intensity. For quantitative evaluation, a model with the Arrhenius equation was utilized [26]:

where and are the integrated PL intensity at temperature T and 0 K, respectively. Regarding the relative intensity quenching with , it is plausible that an activation energy in the Boltzmann factor can be obtained with a fitting constant A, which is associated with thermal dissociation. In the case of CsPbI3/SiO2, a high meV was obtained, which is comparable to its exciton binding energy. This result suggests that thermal exciton dissociation is a dominant mechanism of PL quenching. Moreover, a low meV was obtained in CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs. Therefore, the presence of additional non-radiative processes is expected, such as trap-assisted carrier recombination, exciton delocalization, and phonon-mediated scattering. Hence, CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs are vulnerable to non-radiative losses, and this may explain the significant difference between Figure 3a,b.

Figure 3.

(a,b) Given the temperature-dependent PL spectrum of CsPbBr3/SiO2 and CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs, which are normalized to the peak intensity for clarity, spectrally integrated PL intensity (c,d), linewidth (e,f), and peak energy (g,h) are plotted with regard to temperature, respectively.

Enhanced phonon scattering for temperature leads to a linewidth broadening of the PL spectrum, and this can be described by the following equation [25,26]:

where is the inhomogeneous linewidth independent of temperature, caused by variations in the size, shape, and composition of NCs. The linear term () is attributed to the acoustic–phonon interaction with the acoustic–phonon coupling coefficients (). The third nonlinear term is described in terms of the coupling coefficient () and the energy () of optical phonons, which are associated with the Bose–Einstein distribution.

In Figure 3e,f, the temperature-dependent linewidth of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs and CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs is fitted with Equation (2), where the fitting parameters are summarized in Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials. With increasing temperature from 7 K to 300 K, the linewidth becomes broadened by 76.96 meV and 55.43 meV in CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs and CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs, respectively. The inhomogeneous linewidths of CsPbBr3/SiO2 ( meV) and CsPbI3/SiO2 ( meV) are significantly narrow compared to the recent results of uncoated CsPbBr3 NCs (40.04 ± 0.45 meV) and CsPbI3 NCs (52.12 ± 0.71 meV). This result indicates that the size homogeneity and surface passivation are improved in CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs and CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs. We found that the optical phonon interaction of the third term is dominant compared with the acoustic interaction of the second term (), and the of CsPbBr3/SiO2 (15.516 ± 6.102 meV) and CsPbI3/SiO2 (55.106 ± 17.151 meV) were comparable to the LO phonon energy [36].

As temperature increases, the band gap shift can be observed. The renormalized band gap Eg(T) can be described by the following equation [25,27]:

where the thermal lattice expansion effect results in a linear dependence for temperature (∼) with the thermal expansion coefficient , and the electron–phonon interaction of the third term leads to a nonlinear temperature dependence with the phonon coupling strength and the average optical phonon energy . Given the band gap at K, the thermal lattice expansion effect causes a blueshift of the band gap, but the electron–phonon interaction gives rise to an opposite redshift. Given the PL peak energy of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs (Figure 3g) and CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs (Figure 3h), Equation (3) was fitted (solid line), and the parameters are shown in Table S2 of the Supplementary Materials. This model enables us to separate the two effects of thermal lattice expansion and electron–phonon interaction (dotted lines). At low temperatures, the band gap shift is dominated by the thermal lattice expansion. In the case of typical semiconductors, the thermal lattice expansion results in a band gap decrease (. In contrast, we obtained positive for CsPbI3/SiO2 (0.23 ± 0.03 meV/K) and CsPbBr3/SiO2 (0.26 ± 0.02 meV/K). In the case of perovskite (CsPbX3 NCs, the anti-bonding nature of the interaction between Pb 6s and halide p orbitals becomes significant, and this leads to a distinctive thermal expansion effect of the [PbX6]4− octahedral framework.

At high temperatures, sufficient thermal energy excites large energy phonon states, and the Bose–Einstein distribution in the third term of Equation (2) becomes significant due to the activated optical phonon modes. This effect was quantified in terms of the phonon coupling strength () and the average optical phonon energy (). A large meV was obtained in CsPbI3/SiO2 compared with the small meV in CsPbBr3/SiO2. The large in CsPbI3/SiO2 (66.6 meV) can also explain why the electron–phonon interaction effect remains suppressed at low temperatures. However, the small in CsPbBr3/SiO2 (29.3 meV) provides a relatively lower temperature threshold to activate optical phonons.

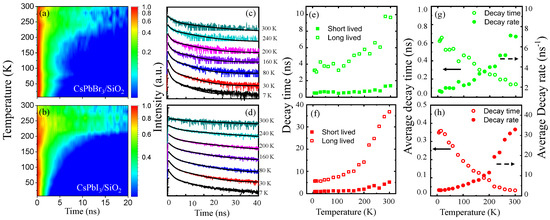

In Figure 4, the time-resolved PL intensity of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs (a,c) and CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs (b,d) is plotted for temperature, which were selected at the dominant PL energy, respectively. For quantitative analysis, two kinds of decay times in CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs (Figure 4e,g) and CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs (Figure 4f,h) were obtained at various temperatures using a bi-exponential model,

where and are the short- and long-lived decay time, and and are the corresponding amplitudes, respectively. For increasing temperature, we found that barely changes with decreased . However, both and show a significant increase for temperature. These results are associated with thermally activated carriers and phonons. At low temperatures, excited carriers are initially trapped in localized states. However, thermal activation suppresses the non-radiative trapping. Exciton recombination time can also be elongated as the interaction with phonons becomes pronounced. While the former mechanism alters the relative weight of and , the latter enhances the dark exciton states and the exciton dissociation. Recent work has reported a similar evidence in the strong exciton–phonon coupling in CsPbX3 perovskite structures [44]. Interestingly, for increasing temperature from 7 K to 300 K, of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs increases from 4ns to 10ns, but the change in in CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs is more significant: 40 ns at K. This result is also consistent with the high meV of CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs compared with that of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs ( meV).

Figure 4.

(a,b) Given time-resolved PL intensity of CsPbBr3/SiO2 and CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs for increasing temperature, the PL intensity decay were fitted by the bi-exponential model at various temperatures (c,d), respectively. This enables us to obtain short- and long-lived decay time for temperature (e,f), whereby the corresponding average decay time and average decay rate were also obtained for temperature (g,h).

To obtain a representative quantity of the decay feature, the average decay time () was also obtained using the four parameters in the bi-exponential model as

In Figure 4g,h, the and 1/ of CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs and CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs are shown for increasing temperature, respectively. Compared with bare CsPbBr3 NCs, CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs are known to show a prolonged PL decay time [36]. The overall feature was correct, but the monotonic model was not enough to define a representative decay time. It is noticeable that the amplitudes ( and ) were also considered to obtain the average decay time. At low temperatures, shows a gradual increase, but a dramatic increase occurs at a critical temperature (K). This critical phenomenon is significant in CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs and is consistent with the strong phonon interactions with the high and . Therefore, is useful to evaluate the degree of localization and thermal activation.

As an additional remark, CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs can be an attractive material system for optical devices. In particular, they are suitable for LED and phosphor-converted color conversion, where their band gap tunability and narrow emission linewidths enable spectrally pure red emission for wide-color-gamut displays and high-brightness solid-state lighting. At the same time, these favorable optical characteristics are also useful in photodetector and photo-conductive architectures, in which strong absorption coefficients and well-defined band edges facilitate efficient photo-carrier generation. Nevertheless, these applications are constrained by temperature-activated non-radiative recombination pathways and phase instability, which are often exacerbated under operational conditions. In this context, it is important to understand how encapsulation-induced stabilization translates into temperature-resilient optical behavior.

4. Conclusions

Compared with the bare NCs of CsPbBr3 and CsPbI3, we confirmed that SiO2 encapsulation improves the stability of the core–shell structures. Although the core crystal structures remain unaffected in the presence of a SiO2 shell, we found that trapping states are still present. Their degree of localization can be quantified in terms of a short-lived decay time and thermal activation energy, as well as the vibration modes of the Si–O–Si and Si–O–C bonds. From our comprehensive analysis of the intensity, linewidth, energy level shift, and decay time of PL spectrum at increased temperature, we concluded that CsPbI3/SiO2 NCs show a stronger interaction with phonons compared with CsPbBr3/SiO2 NCs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nano1010000/s1, Figure S1: STEM-HAADF image for CsPbBr3/SiO2; Figure S2: FTIR spectrum; Figure S3: The as-prepared CsPbBr3 and CsPbBr3/SiO2 toluene solution under day light; Figure S4: XRD pattern; Figure S5: The as-prepared CsPbI3 and CsPbI3/SiO2 toluene solution; Figure S6: Visualization of RGB color evolution of CsPbI3 and CsPbI3/SiO2 toluene solution; Table S1: Fitting parameters for PL FWHM; Table S2: Fitting parameters for PL peak energy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W.H. and K.K.; methodology, M.M., G.E.C. and S.L.; software, M.K.; validation, M.K., M.M. and K.K.; formal analysis, M.K., M.M. and S.H.P.; investigation, M.M. and W.C.; resources, S.W.H.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K., M.M. and K.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K., R.A.T. and K.K.; visualization, M.K.; supervision, K.K.; project administration, K.K.; funding acquisition, K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the BrainLink program (RS-2023-00236798), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT through the National Research Foundation of Korea, as well as by the Korean Government (MSIT) (No. 2022R1A5A8023404, RS-2025-25421510) and by the RISE program, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Busan Metropolitan City (2025-RISE-02-004-202511980001-01).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ma, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, P.; He, W.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, J.; Ma, M.; Wan, M.; Yang, Y.; et al. One-step dual-additive passivated wide-bandgap perovskites to realize 44.72%-efficient indoor photovoltaics. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 1637–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Johnston, M.B.; Snaith, H.J. Efficient planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells by vapour deposition. Nature 2013, 501, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, W.; Deng, N.; Yan, Z.; Sun, W.; Kang, X.; Ni, J. Progress in the preparation and application of CsPbX3 perovskites. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 4053–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gong, W.; Xiang, F.; Li, Y.; Guo, H.; Hao, F.; Niu, X. High-Performance Self-Powered Photodetectors with Space-Confined Hybrid Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2022, 11, 2202215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, K.; Gu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, C.; Yi, N.; Xiao, S.; Song, Q. Solution-Phase Synthesis of Cesium Lead Halide Perovskite Microrods for High-Quality Microlasers and Photodetectors. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2017, 5, 1700023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Xing, J.; Quan, L.N.; de Arquer, F.P.G.; Gong, X.; Lu, J.; Xie, L.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, D.; Yan, C.; et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiency exceeding 20 per cent. Nature 2018, 562, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Lin, K.; Li, W.; Xiao, X.; Lu, J.; Yan, C.; Liu, X.; Xie, L.; Tian, C.; Wu, D.; et al. Efficient all-inorganic perovskite light-emitting diodes enabled by manipulating the crystal orientation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 11064–11072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaklee, K.L.; Leheny, R.F. Direct Determination of Optical Gain in Semiconductor Crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1971, 18, 475–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarinov, D.A.; Anoshkin, S.S.; Tsibizov, I.A.; Sheremet, V.; Isik, F.; Zhizhchenko, A.Y.; Cherepakhin, A.B.; Kuchmizhak, A.A.; Pushkarev, A.P.; Demir, H.V.; et al. High-Quality CsPbBr3 Perovskite Films with Modal Gain above 10 000 cm−1 at Room Temperature. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2023, 11, 2202407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Leaños, A.L.; Cortecchia, D.; Folpini, G.; Srimath Kandada, A.R.; Petrozza, A. Optical Gain of Lead Halide Perovskites Measured via the Variable Stripe Length Method: What We Can Learn and How to Avoid Pitfalls. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2021, 9, 2001773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Chang, W.J.; Lee, C.W.; Park, S.; Ahn, H.-Y.; Nam, K.T. Photocatalytic hydrogen generation from hydriodic acid using methylammonium lead iodide in dynamic equilibrium with aqueous solution. Nat. Energy 2016, 2, 16185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.F.; Yang, M.Z.; Chen, B.X.; Wang, X.D.; Chen, H.Y.; Kuang, D.B.; Su, C.Y. A CsPbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dot/Graphene Oxide Composite for Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5660–5663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protesescu, L.; Yakunin, S.; Bodnarchuk, M.I.; Krieg, F.; Caputo, R.; Hendon, C.H.; Yang, R.X.; Walsh, A.; Kovalenko, M.V. Nanocrystals of Cesium Lead Halide Perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, and I): Novel Optoelectronic Materials Showing Bright Emission with Wide Color Gamut. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 3692–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Lin, J. An overview on enhancing the stability of lead halide perovskite quantum dots and their applications in phosphor-converted LEDs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 310–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ruan, C.; Yin, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yu, W.W. Efficient and Stable White LEDs with Silica-Coated Inorganic Perovskite Quantum Dots. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 10088–10094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Cao, M.; Hu, H.; Yang, D.; Chen, M.; Li, P.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Q. One-Pot Synthesis of Highly Stable CsPbBr3@SiO2 Core-Shell Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 8579–8587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, M.; Han, Z.; Liu, P.; Fang, F.; Chen, W.; Hao, J.; Wu, D.; Pan, R.; Cao, W.; Wang, K. Silica encapsulation of metal perovskite nanocrystals in a photoluminescence type display application. Nanotechnology 2019, 30, 395702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yan, L.; Si, J.; Huo, T.; Hou, X. Strongly luminescent and highly stable CsPbBr3/Cs4PbBr6 core/shell nanocrystals and their ultrafast carrier dynamics. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 946, 169272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, J.Y.; Ma, J.P.; Xuan, T.T.; Guo, S.Q.; Yong, Z.J.; Wang, J.; Kuroiwa, Y.; et al. Cs4PbBr6/CsPbBr3 Perovskite Composites with Near-Unity Luminescence Quantum Yield: Large-Scale Synthesis, Luminescence and Formation Mechanism, and White Light-Emitting Diode Application. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 15905–15912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loiudice, A.; Saris, S.; Oveisi, E.; Alexander, D.T.L.; Buonsanti, R. CsPbBr3 QD/AlOx Inorganic Nanocomposites with Exceptional Stability in Water, Light, and Heat. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 10696–10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.J.; Hofman, E.; Li, J.; Davis, A.H.; Tung, C.H.; Wu, L.Z.; Zheng, W. Photoelectrochemically Active and Environmentally Stable CsPbBr3/TiO2 Core/Shell Nanocrystals. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 28, 1704288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; He, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Synthesis of Asymmetrical CsPbBr3/TiO2 Nanocrystals with Enhanced Stability and Photocatalytic Properties. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tan, Y.; Cao, M.; Hu, H.; Wu, L.; Yu, X.; Wang, L.; Sun, B.; Zhang, Q. Fabricating CsPbX3-Based Type I and Type II Heterostructures by Tuning the Halide Composition of Janus CsPbX3/ZrO2 Nanocrystals. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 5366–5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Yao, R.; Shen, P.; Fang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, H. Quantum Dots Encapsulated by ZrO2 Enhance the Stability of Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 8, 2100776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Xu, Z.; Chen, R.; Zheng, X.; Cheng, X.; Jiang, T. Temperature-dependent excitonic photoluminescence excited by two-photon absorption in perovskite CsPbBr3 quantum dots. Opt. Lett. 2016, 41, 3821–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, B.; Liu, C.; Deng, Z.; Wang, J.; Han, J.; Zhao, X. Low temperature photoluminescence properties of CsPbBr3 quantum dots embedded in glasses. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 17349–17355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saran, R.; Heuer-Jungemann, A.; Kanaras, A.G.; Curry, R.J. Giant Bandgap Renormalization and Exciton–Phonon Scattering in Perovskite Nanocrystals. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2017, 5, 17000231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yu, S.; Shang, X.; Chen, X. Temperature Dependence of Bandgap in Lead-Halide Perovskites with Corner-Sharing Octahedra. Adv. Photonics Res. 2022, 4, 2200193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidaminov, M.I.; Abdelhady, A.L.; Murali, B.; Alarousu, E.; Burlakov, V.M.; Peng, W.; Dursun, I.; Wang, L.; He, Y.; Maculan, G.; et al. High-quality bulk hybrid perovskite single crystals within minutes by inverse temperature crystallization. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demontis, V.; Durante, O.; Marongiu, D.; De Stefano, S.; Matt, S.; Simbula, A.; Capello, C.R.; Pennelli, G.; Quochi, F.; Saba, M.; et al. Photoconduction in 2D Single-Crystal Hybrid Perovskites. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2025, 13, 2402469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bttula, R.K.; Sudakar, C.; Bhyrappa, P.; Veerappan, G.; Ramasamy, E. Single-Crystal Hybrid Lead Halide Perovskites: Growth, Properties, and Device Integration for Solar Cell Application. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 10, 6338–6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wei, L.; Zeng, P.; Liu, M. Formation of highly uniform thinly-wrapped CsPbX3@silicone nanocrystals via self-hydrolysis: Suppressed anion exchange and superior stability in polar solvents. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 9813–9819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Yao, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Shen, Q.; Luo, W.; Zou, Z. Super stable CsPbBr3@SiO2 tumor imaging reagent by stress-response encapsulation. Nano Res. 2020, 13, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, C.K.; Lee, H.; So, M.G.; Lee, C.L. Synthesis of Chemically Stable Ultrathin SiO2-Coated Core-Shell Perovskite QDs via Modulation of Ligand Binding Energy for All-Solution-Processed Light-Emitting Diodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 29798–29808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Yang, W.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y. Highly stable and luminescent silica-coated perovskite quantum dots at nanoscale-particle level via nonpolar solvent synthesis. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 407, 128001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, R.; You, D.; Wang, W.; Xu, C.; Dai, J. Exciton photoluminescence of CsPbBr3@SiO2 quantum dots and its application as a phosphor material in light-emitting devices. Opt. Mater. Express 2020, 10, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, Q. The photothermal stability study of silica-coated CsPbBr3 perovskite nanocrystals. J. Solid State Chem. 2022, 311, 123086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Liu, L.; Yi, F.; Zhao, J. Significantly improving the moisture-, oxygen- and thermal-induced photoluminescence in all-inorganic halide perovskite CsPbI3 crystals by coating the SiO2 layer. J. Lum. 2019, 216, 116722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Zhao, X.; Ruan, L.J.; Qin, C.; Shu, A.; Ma, Y. A universal synthesis strategy for stable CsPbX3@oxide core–shell nanoparticles through bridging ligands. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 10600–10607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, W.; Wang, W.; Xu, B.; Wu, D.; Hao, J.; Cao, W.; Fang, F.; Li, Y.; Zeng, Y.; et al. Halide-Rich Synthesized Cesium Lead Bromide Perovskite Nanocrystals for Light-Emitting Diodes with Improved Performance. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 5168–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, C.; Kobayashi, S.; Izuishi, T.; Nakazawa, N.; Toyoda, T.; Ohta, T.; Hayase, S.; Minemoto, T.; et al. Highly Luminescent Phase-Stable CsPbI3 Perovskite Quantum Dots Achieving Near 100% Absolute Photoluminescence Quantum Yield. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 10373–10383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xiao, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, D.; Sun, J.; Chen, D.; Tang, B.; Wang, S.; Portniagin, A.; Vighnesh, K.; et al. Pure-red electroluminescence of quantum-confined CsPbI3 perovskite nanocrystals obtained by the gradient purification method. Mater. Taday Energy 2024, 41, 101533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Zhu, X.; Xu, T.; Xie, Q.; Chen, H.; Xu, F.; Lin, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y. Highly Stable CsPbI3 Perovskite Quantum Dots Enabled by Single SiO2 Coating toward Down-Conversion Light-Emitting Diodes. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, K.; Meggiolaro, D.; Trinh, M.T.; Joshi, P.P.; Mosconi, E.; Jones, S.C.; De Angelis, F.; Zhu, X.Y. Large polarons in lead halide perovskites. Sci. Mater. 2017, 3, e1701217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.