Abstract

Calcium carbonate (CaCO3) whiskers are promising materials for the high-value utilization of calcium-based resources. Here, aragonite whiskers were synthesized at a carbonation temperature of 90 °C using carbide slag ammonium leachate as the calcium source and CO2 as the precipitant. The effects of control agents, carbonation temperature, Ca2+ solution feeding rate, CO2 flow rate, and stirring speed on whisker morphology and aspect ratio were systematically investigated. Characterization via SEM and XRD revealed that the optimal conditions—carbonation temperature of 90 °C, Ca2+ feeding rate of 1.2 mL∙min−1, ethanol addition of 2 mL, CO2 flow rate of 150 mL∙min−1, and stirring speed of 300 rpm—yielded uniform CaCO3 whiskers with an average length of ~10 μm, an aspect ratio of ~24, and an aragonite purity of 99.42%. TEM confirmed that the whiskers are single crystals growing preferentially along the [001] direction. Hydroxyl groups were found to suppress lateral growth on the (200) facet, favoring elongation along the c-axis and enabling high-aspect-ratio whisker formation. These findings provide useful guidance for the scalable synthesis and industrial application of aragonite whiskers.

1. Introduction

Carbide slag, a solid waste byproduct of acetylene generation, contains approximately 90% Ca(OH)2 (dry basis) and represents a valuable calcium-rich resource [1]. Calcium carbonate (CaCO3), an important inorganic filler, is extensively used in the plastics, rubber, and papermaking industries [2]. CaCO3 exists in three polymorphic forms—calcite, aragonite, and vaterite—with relative stabilities in order of calcite > aragonite > vaterite [3]. Calcite generally exhibits a blocky or granular morphology, aragonite typically forms needle- or rod-like crystals, while vaterite tends to adopt spherical or disc-like structures [4]. By carefully modulating crystallization conditions, CaCO3 with tunable morphologies can be synthesized. The synthesis of aragonite whiskers is of great interest due to their superior performance as functional reinforcing fillers. Their needle-like monocrystalline structure and high aspect ratio enable them to effectively transfer stress within composite matrices, significantly enhancing mechanical properties such as tensile strength, modulus, and impact toughness in polymers (e.g., plastics, rubber) and cement [5]. Beyond these applications, they are also utilized in coatings, friction materials, and as asphalt modifiers to improve wear resistance and stability [6]. Consequently, developing routes to produce high-value-added aragonite whiskers from low-cost sources like carbide slag presents significant practical and environmental merits.

Several synthetic strategies have been established for aragonite whiskers, with hydrothermal synthesis [7], double decomposition [8], and carbonation [9] being the most widely adopted. These approaches generally rely on the interaction between control agents and crystal facets, which influence nucleation kinetics, guide oriented growth, and thus tailor whisker morphology [10]. For instance, Le et al. [11] employed calcium dodecyl benzenesulfonate as a control agent in a microreactor system, obtaining CaCO3 whiskers with an average length of ~27 μm, an aspect ratio of ~58, and an aragonite purity above 98%. Hua et al. [12] utilized Mg2+ as a control agent in a gas-liquid contact system, producing whiskers with lengths of ~20 μm, aspect ratios of 15–20, and a purity of 99.38%. Similarly, Meng et al. [13] synthesized CaCO3 whiskers via electrochemical cathodic reduction using calcium chloride, sodium bicarbonate, and magnesium chloride, yielding products with an average length of 18.78 μm, an aspect ratio of 36.82, and a purity of 94.59%. While traditional methods for synthesizing aragonite whiskers are well-established, they often rely on high-purity reagents and energy-intensive processes. A promising and innovative direction involves the use of secondary calcium sources, which not only reduces costs but also aligns with the principles of the circular economy. This approach treats calcium-rich industrial wastes as valuable feedstocks. For instance, yellow phosphorus slag [14] has been successfully converted into high-purity aragonite whiskers, and dolomite [12] has been utilized as a raw material for whisker production. Similarly, Hu et al. [15] demonstrated a novel reversible reaction pathway that synthesizes aragonite directly from ground calcium carbonate (GCC) in a MgCl2 solution, bypassing the high-energy calcination of limestone. These studies underscore that utilizing alternative calcium sources is a viable and advanced strategy for sustainable materials synthesis. In this context, our work utilizes carbide slag, another abundant calcium-rich waste, as a novel feedstock for the efficient production of aragonite whiskers, representing a significant contribution to this emerging field.

Because aragonite is a metastable phase, it readily transforms into the thermodynamically stable calcite during synthesis [16]. As a result, most reported methods employ relatively low initial Ca2+ concentration (e.g., 0.1 mol∙L−1) and rely on precise control of system supersaturation to stabilize aragonite and regulate whisker morphology [17,18,19]. However, these conditions typically result in low single-pass yields and high production costs, which hinder their industrial applicability.

To address these limitations, the present study investigates the carbonation synthesis of CaCO3 whiskers from carbide slag at a higher initial Ca2+ concentration (0.625 mol·L−1). By strategically selecting control agents and systematically optimizing process parameters, large-scale synthesis of well-defined aragonite whiskers was achieved under mild conditions. The resulting products exhibit uniform morphology, with an average length of ~10 μm, an aspect ratio of ~24, and an aragonite purity of 99.42%.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The carbide slag used in the experiment was provided by a certain enterprise. Additional characterization of the carbide slag, including XRD, SEM/EDS, and DTA/TG analyses, can be found in Figures S1 and S2. Its major components and chemical composition are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Major components and chemical composition of carbide slag.

Ammonium chloride (NH4Cl, ≥99.5%), magnesium chloride (MgCl2, ≥98.0%), ammonium acetate (≥98.0%), aluminum chloride (AlCl3, ≥97.0%), anhydrous magnesium sulfate (MgSO4, ≥99.0%), zinc chloride (ZnCl2, ≥98.0%), sodium hexametaphosphate (≥95.0%), polyethylene glycol (PEG), tributyl phosphate (≥98.5%), pentaerythritol (≥98.0%), anhydrous ethanol (≥99.7%), triammonium phosphate (≥95.0%), sodium dodecyl sulfonate (SDS, ≥97.0%), glucose, triethanolamine, and ammonium bicarbonate (≥98.0%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. All reagents were not treated before use.

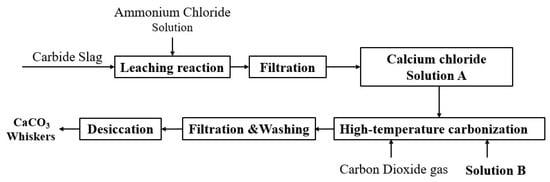

2.2. Preparation of CaCO3 Whiskers

The experimental procedure followed the technical route outlined in Figure 1. Briefly, 10 g of carbide slag was added to 100 mL of 2.9 mol∙L−1 NH4Cl solution and leached at 40 °C for 1 h. After filtering to remove insoluble impurities, the resulting mother liquor was diluted with deionized water to obtain a Ca2+ solution (Solution A, 1.0 mol∙L−1). A predetermined amount of control agent was dissolved in 30 mL of deionized water to obtain Solution B. Under controlled temperature and stirring conditions (magnetic stirring), 50 mL of Solution A was pumped at a specified feeding rate into Solution B, which was placed in a specially designed reactor with good sealing, while CO2 gas was continuously introduced at a defined flow rate. Upon completion of adding Solution A, the CO2 flow was stopped. The resulting suspension was then filtered, washed, and dried to yield a white powder product for subsequent characterization.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the preparation route of CaCO3 whiskers from carbide slag.

2.3. Characterization

The as-prepared CaCO3 products were characterized via scanning electron microscopy (SEM, SU8020, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) operated at an accelerating voltage of less than or equal to 5 kV and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEM-2100F, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) operated at an accelerating voltage of 60 kV. The X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku D/MAX-2500VL/PC, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) patterns obtained on a DMAX-γ X-ray diffractometer using Cu Ka radiation were used to determine the identity of the crystalline phase. The functional groups of the samples were analyzed via Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Nicolet 6700, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA, infrared spectrometer, mid-infrared-ATR attenuated total reflection method, scanning wavelength range: 500–4000 cm−1).

3. Results and Discussion

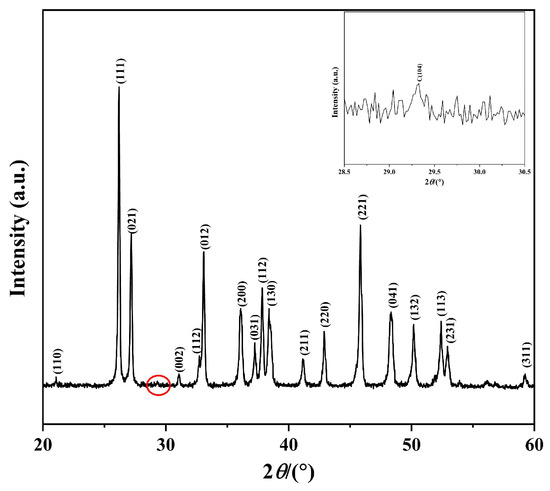

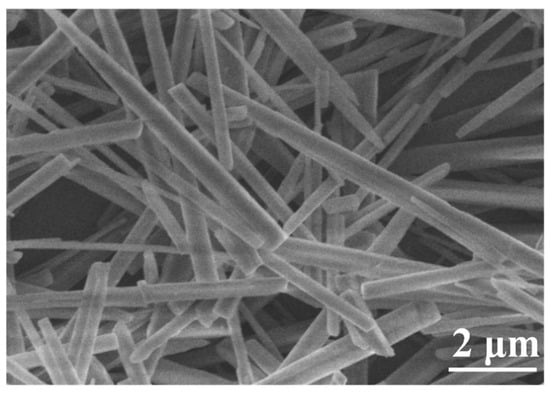

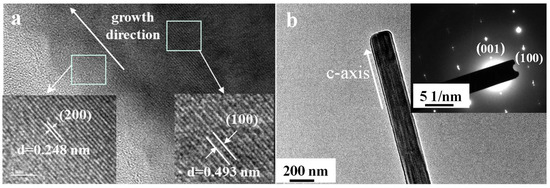

Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the XRD pattern, FE-SEM image, HR-TEM images, and FT-IR spectrum of CaCO3 samples prepared under the optimized synthesis conditions (carbonation temperature: 90 °C, Ca2+ solution feeding rate: 1.2 mL∙min−1, ethanol addition: 2 mL, CO2 flow rate: 150 mL∙min−1, stirring speed: 300 rpm).

Figure 2.

XRD pattern of the prepared CaCO3 sample. (The inset shows an enlarged view of the red circle region between 25° and 35°).

Figure 3.

FE-SEM image of the prepared CaCO3 whiskers.

Figure 4.

HR-TEM (a) and SAED (b) images of the prepared CaCO3 whiskers.

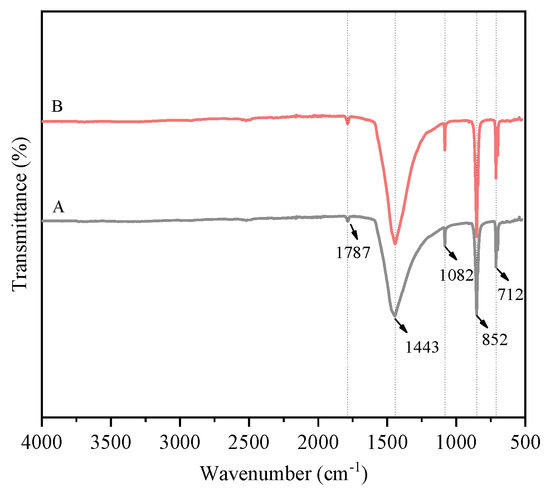

Figure 5.

FT-IR spectrum of the prepared CaCO3 whisker sample. A—without the addition of ethanol; B—with the addition of 2 mL ethanol.

As shown in Figure 2, the sharp diffraction peaks indicate the high crystallinity of the obtained CaCO3. All major diffraction peaks can be unambiguously indexed to orthorhombic aragonite CaCO3 (JCPDS 75-2230). Additionally, very weak reflections corresponding to the (104) facet of trigonal calcite CaCO3 (JCPDS 47-1743) are observed, as highlighted in the inset. Using Equation (1) [20,21], the aragonite content of the sample was calculated to be 99.42%.

where y (%) is the molar fraction of aragonite, IA is the integral intensity of the strongest (111) reflection of aragonite, and IC is the integral intensity of the strongest (104) reflection of calcite.

As observed in Figure 3, the CaCO3 whiskers exhibit smooth surfaces and well-defined morphologies, with an average diameter of ~200 nm and an aspect ratio of ~24.

The high-resolution TEM (HR-TEM) image (Figure 4a) reveals distinct lattice fringes with measured spacings of 0.248 nm and 0.493 nm (inset), corresponding to the (100) and (200) facets of aragonite, respectively (d200 = 0.24805 nm). This confirms that the lateral surfaces of the whiskers are dominated by the (200) facets. The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern displays sharp and regularly arranged diffraction spots, indicating the single-crystal nature of the whiskers with an orthorhombic structure and a preferred growth orientation along the [001] c-axis.

In Figure 5, the absorption band observed at 1787 cm−1 is assigned to the C=O stretching vibration. Peaks at 1443 cm−1 and 1082 cm−1 are attributed to the asymmetric and symmetric C–O stretching vibrations, respectively. The band at 852 cm−1 is attributed to the out-of-plane deformation vibration of the group, while the peak at 712 cm−1 arises from its in-plane deformation [22,23]. Comparison of spectra indicates no significant shifts or intensity changes in the absorption peaks with the addition of the control agent. Furthermore, no characteristic ethanol absorption bands were detected, likely due to its high solubility in water, low dosage, and effective removal during subsequent washing.

These results highlight that the appropriate selection of control agents, together with precise regulation of carbonation parameters, play a critical role in stabilizing aragonite formation and ensuring the morphological uniformity of the resulting whiskers.

3.1. Screening of Control Agents

Under the experimental conditions of a Ca2+ solution feeding rate of 0.9 mL∙min−1, carbonation temperature of 90 °C, control agent addition 3% (solid, relative to the theoretical yield of CaCO3 by mass) or 1 mL (liquid), CO2 flow rate of 100 mL∙min−1, and stirring speed of 200 rpm, the morphology and aspect ratio of CaCO3 samples prepared with different control agents are summarized in Table 2. The control agents listed in Table 2 were selected based on their reported influence on crystallization processes, including inorganic ions (e.g., Mg2+, PO43−), organic modifiers (e.g., glucose, triethanolamine), and polymers, to allow systematic investigation of their effects on CaCO3 morphology. Representative FE-SEM images of these samples are presented in Figure 6.

Table 2.

Morphology and aspect ratio of CaCO3 samples prepared with different control agents.

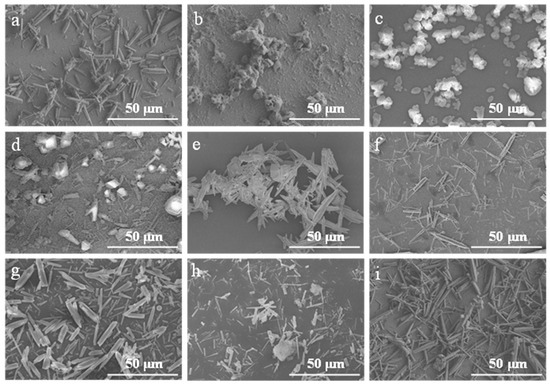

Figure 6.

FE-SEM images of CaCO3 samples prepared with different control agents. (a) Blank; (b) Sodium hexametaphosphate; (c) Sodium dihydrogen phosphate; (d) PEG; (e) Tributyl phosphate; (f) Ethanol; (g) MgCl2; (h) Ammonium acetate; (i) Triethanolamine.

As summarized in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 6, the CaCO3 samples synthesized without a control agent (Figure 6a) predominantly exhibited irregular, short rod-like morphologies. In contrast, the addition of various control agents led to notable changes in crystal morphology. Among them, the use of 1 mL ethanol (Figure 6f) yielded CaCO3 whiskers with elongated rod-like structures and improved dimensional uniformity. Quantitative analysis using Nano-Measure software (version 1.2) determined an average aspect ratio of ~13.5 for these whiskers. Based on these results, ethanol was identified as the most effective control agent under the present experimental conditions.

3.2. Effect of Carbonization Temperature and Ethanol Addition on the Crystal Phase of CaCO3

Carbonation temperature was a key parameter governing the crystalline phase of CaCO3 [24]. Even with constant synthesis conditions, variations in temperature can induce significant phase transformations. In this study, under fixed conditions (Ca2+ solution feeding rate: 0.9 mL∙min−1, CO2 flow rate: 100 mL∙min−1, stirring speed: 200 rpm), aragonite CaCO3 samples were synthesized at carbonation temperatures of 75, 80, 85, 90, and 95 °C, both without ethanol and with the addition of 1 mL ethanol. The results were summarized in Figure 7 and Figure 8.

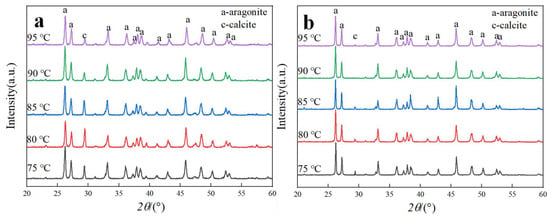

Figure 7.

XRD patterns of CaCO3 samples prepared at different carbonation temperatures with and without ethanol. (a) Without ethanol. (b) With 1 mL ethanol.

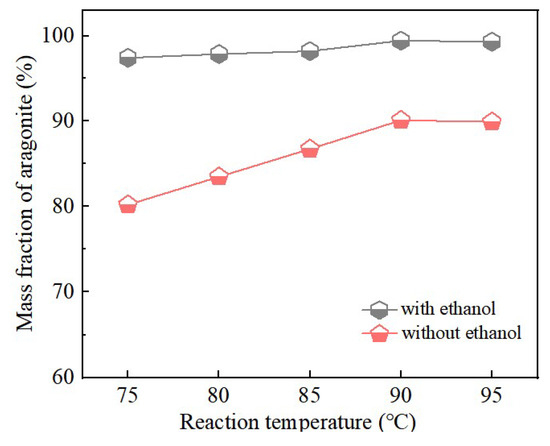

Figure 8.

Aragonite CaCO3 samples were prepared at different carbonation temperatures with and without ethanol.

Figure 7 and Figure 8 present the XRD patterns and aragonite content of CaCO3 samples synthesized at various carbonation temperatures, both in the absence and presence of ethanol. As shown in Figure 7, all samples within the investigated temperature range consisted of a mixture of aragonite and calcite, with aragonite constituting the predominant crystalline phase.

Figure 8 further demonstrated that the addition of ethanol markedly enhances aragonite formation compared with samples synthesized without ethanol. In the absence of ethanol, the aragonite content gradually increased with temperature up to 90 °C, where the maximum value was obtained. Further increases in carbonation temperature beyond 90 °C produced no substantial change in aragonite content. These results identify 90 °C as the optimal carbonation temperature under the present experimental conditions.

3.3. Effects of Operation Conditions on the Morphology of CaCO3

3.3.1. Ca2+ Solution Feeding Rate

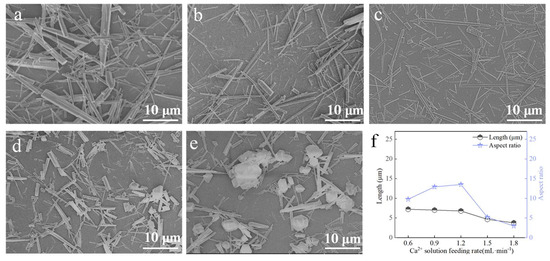

At a carbonation temperature of 90 °C, with 1 mL ethanol, a CO2 flow rate of 100 mL∙min−1, and a stirring rate of 200 rpm, the influence of Ca2+ solution feeding rate on the morphology of CaCO3 whiskers was investigated (Figure 9). When the feeding rate was 0.6 mL∙min−1, the products were mainly thick rods with irregular morphologies. As the feeding rate increased, whisker diameters decreased and aspect ratios increased. At 1.2 mL∙min−1, the maximum aspect ratio was achieved, accompanied by improved morphological uniformity (Figure 9c,f). Beyond this point, higher feeding rates led to a sharp decrease in aspect ratio, and the products shifted toward irregular rods and block-like particles. Therefore, 1.2 mL∙min−1 was identified as the optimal Ca2+ solution feeding rate.

Figure 9.

Effect of Ca2+ solution feeding rate on CaCO3 whiskers morphology ((a) 0.6 mL∙min−1; (b) 0.9 mL∙min−1; (c) 1.2 mL∙min−1; (d) 1.5 mL∙min−1; (e) 1.8 mL∙min−1) and the length/aspect ratio of the prepared whiskers (f).

3.3.2. Carbonation Temperature

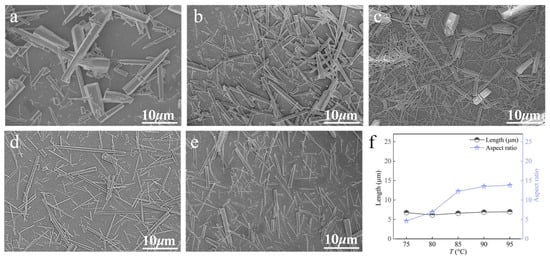

Carbonation temperature is the critical factor governing the crystal phase selection of the product, as it regulates the reaction kinetics and thermodynamics, the solution’s supersaturation, and even the crystal growth orientation [6,25]. At a Ca2+ solution feeding rate of 1.2 mL∙min−1, a CO2 flow rate of 100 mL∙min−1, and a stirring speed of 200 rpm, the influence of carbonation temperature was examined (Figure 10). When the temperature is below 90 °C, the products are mainly block-like and rod-like. As the temperature increases, whisker content in the product increases, their aspect ratio increases, and they become more uniform. When the temperature is further raised, no significant changes are observed in either the whisker content or the aspect ratio. Therefore, 90 °C is selected as the optimal temperature for the preparation of CaCO3 whiskers.

Figure 10.

Effect of carbonation temperature on CaCO3 whiskers morphology ((a) 75 °C; (b) 80 °C; (c) 85 °C; (d) 90 °C; (e) 95 °C) and the length/aspect ratio of the prepared whiskers (f).

3.3.3. Ethanol Addition

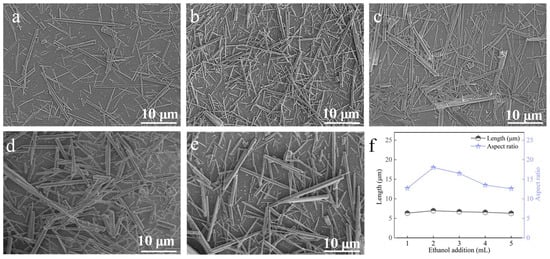

At a carbonation temperature of 90 °C, with a Ca2+ solution feeding rate of 1.2 mL∙min−1, a CO2 flow rate of 100 mL∙min−1, and a stirring speed of 200 rpm, the influence of ethanol dosage was examined (Figure 11). With 1 mL of ethanol, the sample contained numerous dispersed fine whiskers. Increasing the ethanol amount to 2 mL yielded whiskers with the highest aspect ratio and improved dimensional uniformity (Figure 11b,f). Further increases in ethanol addition resulted in thicker whiskers and reduced aspect ratios. Hence, 2 mL of ethanol was determined as the optimal addition.

Figure 11.

Effect of ethanol addition on CaCO3 whiskers morphology ((a) 1 mL; (b) 2 mL; (c) 3 mL; (d) 4 mL; (e) 5 mL) and the length/aspect ratio of the prepared whiskers (f).

3.3.4. CO2 Flow Rate

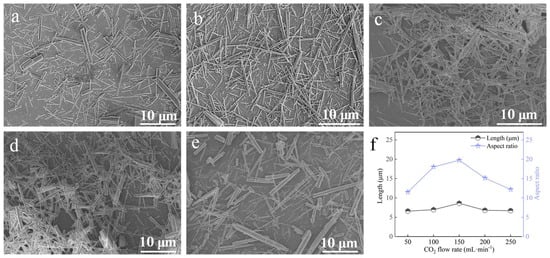

At a carbonation temperature of 90 °C, with a Ca2+ solution feeding rate of 1.2 mL∙min−1, ethanol addition of 2 mL, and a stirring speed of 200 rpm, the effect of CO2 flow rate was studied (Figure 12). At 50 and 100 mL∙min−1, the samples contained a high proportion of finer whiskers. Increasing the CO2 flow rate to 150 mL∙min−1 maximized the aspect ratio (Figure 12c,f). Further increases in flow rate caused whisker diameters to increase and aspect ratios to decrease. Therefore, 150 mL·min−1 was identified as the optimal CO2 flow rate.

Figure 12.

Effect of CO2 flow rate on CaCO3 whiskers morphology ((a) 50 mL∙min−1; (b) 100 mL∙min−1; (c) 150 mL∙min−1; (d) 200 mL∙min−1; (e) 250 mL∙min−1) and the length/aspect ratio of the prepared whiskers (f).

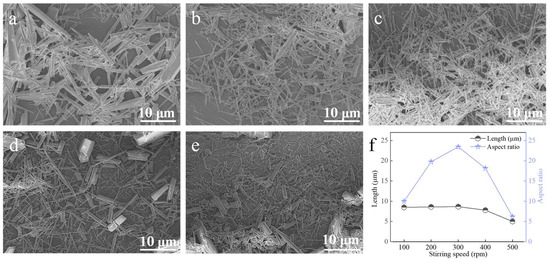

3.3.5. Stirring Speed (MAGNETIC Stirring)

At a carbonation temperature of 90 °C, with a Ca2+ solution feeding rate of 1.2 mL∙min−1, ethanol addition of 2 mL, and a CO2 flow rate of 150 mL∙min−1, the effect of stirring speed was investigated (Figure 13). When the stirring speed was below 300 rpm, the aspect ratio increased with increasing speed. At 300 rpm, the maximum aspect ratio was achieved (see Figure 13b,f). Further increases above 300 rpm reduced the aspect ratio. The observed trend can be explained by the interplay between mixing efficiency and shear stress. At stirring speeds below 300 rpm, the mass transfer rate is insufficient, leading to non-uniform mixing of Ca2+, CO2, and ethanol. This creates local concentration gradients that hinder the regular, oriented growth necessary for achieving a high aspect ratio. Consequently, the aspect ratio increases with improved mixing as the stirring speed rises to 300 rpm. Beyond this optimal point, however, excessive shear forces become dominant. These forces can fracture the elongated crystals or disrupt their directional alignment along the preferred crystallographic axis, thereby reducing the overall aspect ratio [26,27]. Therefore, 300 rpm was determined as the optimal stirring speed.

Figure 13.

Effect of stirring speed on CaCO3 whiskers morphology ((a) 100 rpm; (b) 200 rpm; (c) 300 rpm; (d) 400 rpm; (e) 500 rpm) and the length/aspect ratio of the prepared whiskers (f).

4. Formation Mechanism of Aragonite Whiskers

According to Ostwald’s rule of stages, crystallization occurs via two successive steps: nucleation and crystal growth. Nuclei first form in a supersaturated solution, after which ions continuously deposit onto these nuclei in accordance with crystallographic symmetry, replicating the unit cell structure and facilitating crystal growth [28,29]. Based on present experimental results, the formation mechanism of aragonite whiskers can be understood from two aspects.

4.1. Formation of Aragonite

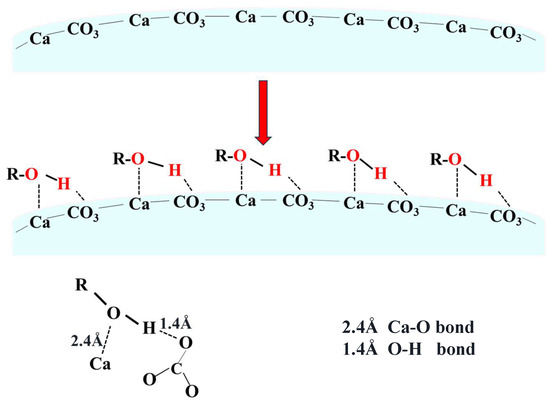

The crystallization of aragonite is governed by the interplay of thermodynamic and kinetic factors. As a metastable phase, aragonite typically requires external intervention to compete against the thermodynamically favored calcite [30]. In this context, both carbonation temperature and ethanol addition play pivotal roles. As illustrated in Figure 7 and Figure 8, elevating carbonation temperature facilitates the transition from calcite to aragonite, indicating that temperature modulates the kinetics and supersaturation of CaCO3 polymorphs, thereby influencing phase selection. Concurrently, ethanol molecules act as an effective control agent by selectively adsorbing on specific crystallographic planes. This adsorption is mediated by the alcoholic hydroxyl (–OH) functional group, which binds to the calcite (104) facet through a dual mechanism: hydrogen bonding between the –OH group and oxygen atoms of surface , and coordination of the ethanol oxygen lone pairs with exposed Ca2+ ions [31,32,33]. Together, these interactions form a stable and ordered adsorption layer that inhibits the nucleation and growth of calcite, thereby favoring the alternative formation of aragonite.

The critical role of the hydroxyl group and the influence of molecular structure are further supported by control experiments with alternative additives. Molecules bearing multiple, accessible hydroxyl groups within a compact and rigid structure—such as triethanolamine and pentaerythritol—exhibited efficacy comparable to ethanol in promoting aragonite whiskers. In contrast, the long-chain and flexible polyethylene glycol (PEG) proved ineffective, yielding mostly aggregated particles (as shown in Figure S3). This contrast highlights that effective polymorph control requires not only the presence of hydroxyl groups but also a molecular geometry conducive to forming a dense, well-ordered inhibitory layer on the specific calcite surface.

A schematic representation of this hydroxyl-mediated interaction is illustrated in Figure 14. This mechanism is consistent with the quantitative results in Figure 8, where the aragonite content in ethanol-assisted samples is significantly higher than in samples synthesized without ethanol, confirming the selective inhibition of calcite by hydroxyl-functionalized molecules.

Figure 14.

Schematic diagram of ethanol interaction with the calcite (104) facet (Ca-O and O-H bonds).

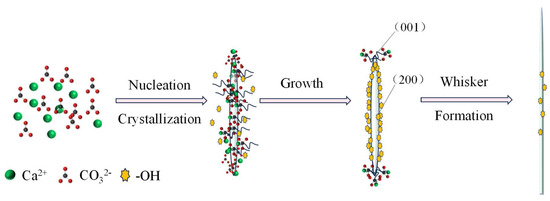

4.2. Formation of CaCO3 Whiskers

Crystal growth is inherently anisotropic, with preferential extension along specific crystallographic orientations, giving rise to distinct morphologies [34]. In this study, ethanol plays a decisive role in directing the anisotropic growth of aragonite whiskers.

As illustrated in Figure 15, hydroxyl groups from ethanol are dynamically adsorbed onto the low-energy (200) facets, which correspond to the lateral surfaces of the whiskers (Figure 4). This adsorption inhibits lateral growth, while Ca2+ and ions preferentially deposit on the higher-energy (001) facet, promoting elongation along the c-axis. This anisotropic deposition drives preferential extension along [001], resulting in whiskers with high aspect ratios and uniform morphologies.

Figure 15.

Schematic diagram of the ethanol-mediated growth mechanism of aragonite whiskers.

5. Conclusions

Aragonite whiskers were successfully synthesized via a carbonation route at 90 °C using carbide slag as the calcium source, ammonium chloride as the leaching agent, and CO2 as the precipitant. The effects of carbonation temperature, ethanol addition, Ca2+ solution feeding rate, CO2 flow rate, and stirring speed on whisker morphology and aspect ratio were systematically evaluated. The optimal conditions were determined as 90 °C, 2 mL ethanol, a Ca2+ solution feeding rate of 1.2 mL∙min−1, a CO2 flow rate of 150 mL∙min−1, and a stirring speed of 300 rpm.

The results indicate that these parameters strongly influence whisker morphology and dimensional uniformity. Mechanistic analysis indicates that ethanol plays a decisive role in stabilizing aragonite and directing anisotropic growth. Ethanol molecules selectively adsorb onto the (104) facet of calcite, suppressing its growth, while hydroxyl groups adsorb on the (200) facet of aragonite whiskers, inhibiting lateral growth. This facet-selective adsorption promotes elongation along the c-axis, enabling the formation of aragonite whiskers with a high aspect ratio.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nano15241894/s1, Figure S1. SEM/EDS image of carbide slag. Figure S2. XRD pattern and DTA/TG image of carbide slag. Figure S3. FE-SEM images of CaCO3 samples prepared with (a) Triethanolamine; (b) pentaerythritol; (c) PEG.

Author Contributions

R.W.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft. Z.X.: Validation, Investigation. B.Y.: Methodology, Writing—Review and Editing. B.W.: Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hefei Cement Research and Design Institute Co., Ltd. (NO. 202203a05020030).

Data Availability Statement

All experimental datasets supporting the findings of this study are fully available within the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this study received funding from Hefei Cement Research and Design Institute Co., Ltd. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Gong, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Cao, J.; Wang, C. Recycling and utilization of calcium carbide slag—Current status and new opportunities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, K.; Furukawa, R.; Shirakawa, Y.; Shimosaka, A.; Hidaka, J. Effect of surface properties of calcium carbonate on aggregation process investigated by molecular dynamics simulation. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 49, 1724–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkiss, K. Variations in the Crystalline Form of Calcium Carbonate precipitated from Artificial Sea Water. Nature 1964, 201, 492–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Pulido, G.; Nash, M.C.; Anthony, K.R.N.; Bender, D.; Opdyke, B.N.; Reyes-Nivia, C.; Troitzsch, U. Greenhouse conditions induce mineralogical changes and dolomite accumulation in coralline algae on tropical reefs. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, P.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Mei, K.; Gao, Q.; Cheng, X. Study on the effect of CaCO3 whiskers on carbonized self-healing cracks of cement paste: Application in CCUS cementing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 321, 126368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liendo, F.; Arduino, M.; Deorsola, F.A.; Bensaid, S. Factors controlling and influencing polymorphism, morphology and size of calcium carbonate synthesized through the carbonation route: A review. Powder Technol. 2022, 398, 117050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Dong, C.; An, C. Large-Scale Growth of Tubular Aragonite Whiskers through a MgCl2-Assisted Hydrothermal Process. Materials 2011, 4, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, C.; Thenepalli, T.; Huh, J.-H.; Ahn, J.W. Precipitated Calcium Carbonate Synthesis by Simultaneous Injection to Produce Nano Whisker Aragonite. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 2016, 53, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhao, X.; Sheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Deng, Y.; Ma, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z. Biomimetic synthesis of dendrite-shaped aragonite particles with single-crystal feature by polyacrylic acid. Colloids Surf. A 2007, 297, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, B.; Tang, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, B. High-yield synthesis of vaterite CaCO3 microspheres in ethanol/water: Structural characterization and formation mechanisms. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 5540–5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Luo, G. Growth of Aragonite CaCO3 Whiskers in a Microreactor with Calcium Dodecyl Benzenesulfonate as a Control Agent. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 7131–7140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, S.-Y.; Zheng, Q.; Yu, F.; Qi, T.-Y.; Ma, Y.-L.; Jia, S.-Y.; Fan, T.-B.; Li, X. Preparation and Mechanism of Calcium Carbonate Whiskers from DoLOMITE Refined Solution. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2024, 59, 2300305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, G.; Xu, J.; Cheng, R.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, P.; Zhang, L. Controllable synthesis and characterization of high purity calcium carbonate whisker-like fibers by electrochemical cathodic reduction method. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 342, 130923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Ding, W.; Peng, T.; Sun, H. Synthesis and characterization of calcium carbonate whisker from yellow phosphorus slag. Open Chem. 2020, 18, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Shao, M.; Cai, Q.; Ding, S.; Zhong, C.; Wei, X.; Deng, Y. Synthesis of needle-like aragonite from limestone in the presence of magnesium chloride. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2009, 209, 1607–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Xuan, D.; Lu, J.; Zhang, S.; Poon, C.S. Production of aragonite whiskers by carbonation of fine recycled concrete wastes: An alternative pathway for efficient CO2 sequestration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 173, 113079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, H.; Nanri, Y.; Kitamura, M. Effect of NaOH on aragonite precipitation in batch and continuous crystallization in causticizing reaction. Powder Technol. 2003, 129, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogo, M.; Suzuki, K.; Umegaki, T.; Kojima, Y. Control of aragonite formation and its crystal shape in CaCl2-Na2CO3-H2O reaction system. J. Cryst. Growth 2021, 559, 125964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zou, H.K.; Shao, L.; Chen, J.F. Controlling factors and mechanism of preparing needlelike CaCO3 under high-gravity environment. Powder Technol. 2004, 142, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Deng, Y. Supersaturation control in aragonite synthesis using sparingly soluble calcium sulfate as reactants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 266, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xiang, L. Controllable synthesis of calcium carbonate polymorphs at different temperatures. Powder Technol. 2009, 189, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minakshi, M.; Mujeeb, A.; Whale, J.; Evans, R.; Aughterson, R.; Shinde, P.A.; Ariga, K.; Shrestha, L.K. Synthesis of Porous Carbon Honeycomb Structures Derived from Hemp for Hybrid Supercapacitors with Improved Electrochemistry. ChemPlusChem 2024, 89, e202400408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minakshi, M.; Samayamanthry, A.; Whale, J.; Aughterson, R.; Shinde, P.A.; Ariga, K.; Kumar Shrestha, L. Phosphorous—Containing Activated Carbon Derived From Natural Honeydew Peel Powers Aqueous Supercapacitors. Chem.—Asian J. 2024, 19, e202400622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Agudo, C.; Cölfen, H. Exploring the Potential of Nonclassical Crystallization Pathways to Advance Cementitious Materials. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 7538–7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biasin, A.; Segre, C.U.; Strumendo, M. CaCO3 Crystallite Evolution during CaO Carbonation: Critical Crystallite Size and Rate Constant Measurement by In-Situ Synchrotron Radiation X-ray Powder Diffraction. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 5188–5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szterner, P.; Biernat, M. Effect of reaction time, heating and stirring rate on the morphology of HAp obtained by hydrothermal synthesis. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 147, 13059–13071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeder, R.K.; Converse, G.L.; Leng, H.; Yue, W. Kinetic Effects on Hydroxyapatite Whiskers Synthesized by the Chelate Decomposition Method. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 89, 2096–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vekilov, P.G. The two-step mechanism of nucleation of crystals in solution. Nanoscale 2010, 2, 2346–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthika, S.; Radhakrishnan, T.K.; Kalaichelvi, P. A Review of Classical and Nonclassical Nucleation Theories. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 6663–6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Dai, Z.; Shang, D.; Yin, C.; Du, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Yin, C. Ultrahigh purity CaCO3 whiskers derived from the enhanced diffusion of carbonate ions from a larger liquid–gas interface through porous quartz stones. CrystEngComm 2020, 22, 6407–6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovet, N.; Yang, M.; Javadi, M.S.; Stipp, S.L. Interaction of alcohols with the calcite surface. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 3490–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand, K.K.; Yang, M.; Makovicky, E.; Cooke, D.J.; Hassenkam, T.; Bechgaard, K.; Stipp, S.L.S. Binding of Ethanol on Calcite: The Role of the OH Bond and Its Relevance to Biomineralization. Langmuir 2010, 26, 15239–15247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, D.J.; Gray, R.J.; Sand, K.K.; Stipp, S.L.S.; Elliott, J.A. Interaction of Ethanol and Water with the {} Surface of Calcite. Langmuir 2010, 26, 14520–14529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liz-Marzán, L.M.; Grzelczak, M. Growing anisotropic crystals at the nanoscale. Science 2017, 356, 1120–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).