Abstract

Viruses are among the most infectious pathogens, responsible for the highest death toll around the world. Lack of effective clinical drugs for most viral diseases emphasizes the need for speedy and accurate diagnosis at early stages of infection to prevent rapid spread of the pathogens. Glycans are important molecules which are involved in different biological recognition processes, especially in the spread of infection by mediating virus interaction with endothelial cells. Thus, novel strategies based on nanotechnology have been developed for identifying and inhibiting viruses in a fast, selective, and precise way. The nanosized nature of nanomaterials and their exclusive optical, electronic, magnetic, and mechanical features can improve patient care through using sensors with minimal invasiveness and extreme sensitivity. This review provides an overview of the latest advances of functionalized glyconanomaterials, for rapid and selective biosensing detection of molecules as biomarkers or specific glycoproteins and as novel promising antiviral agents for different kinds of serious viruses, such as the Dengue virus, Ebola virus, influenza virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), influenza virus, Zika virus, or coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19).

Keywords:

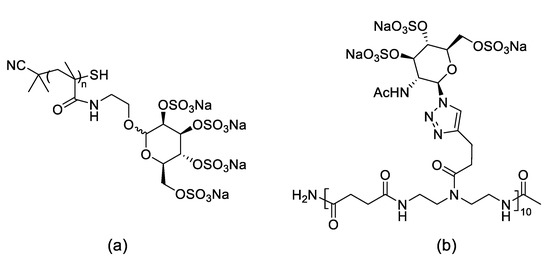

glycan; nanomaterial; glycoconjugates; nanoparticles; virus; coronavirus; SARS-CoV-2; biosensor; antiviral drug 1. Introduction

Viruses are among the most infectious pathogens, responsible for the highest number of deaths worldwide. Although the pathogenic mechanisms of viruses are diverse, all existing viruses need a host to maintain their existence [1]. The complex glycans attached on the surface of viral envelope proteins (up to half of the molecular weight of these glycoproteins) helps the pathogen elude recognition by the host immune system [2,3] altering the host’s ability to generate an effective adaptive immune response [4] or improving infectivity [5]. Although the innate immune system has evolved a range of strategies for responding to glycosylated pathogens, mutations in such proteins (virus variants) could impact by creating new or removing existing locations of the glycans (glycosites) on the surface antigens [6,7].

Viral infections result in millions of deaths and huge economic losses annually. In recent years, important examples are the viruses Ebola, Zika, SARS, MERS or recently the actual pandemic SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus (which have infected more than 140 million and killed more than 3 million people so far (data from 21 April 2021) [8].

This means that novel systems for rapid and efficient detection of viruses are critical to control the infection spread. From the last decade, nanotechnology has signified an important advance in the development of nanomaterials for detection devices [9,10,11,12]. The fabrication of biosensors based on antibodies, proteins, or biomolecules has been highlighted as a key element for detection of the virus [13].

Glycan molecules have been demonstrated to have a very important role in many biological recognition processes [14]. Indeed, different glycomolecules such as heparin derivatives or sialic acids derivatives have shown antiviral activity [15].

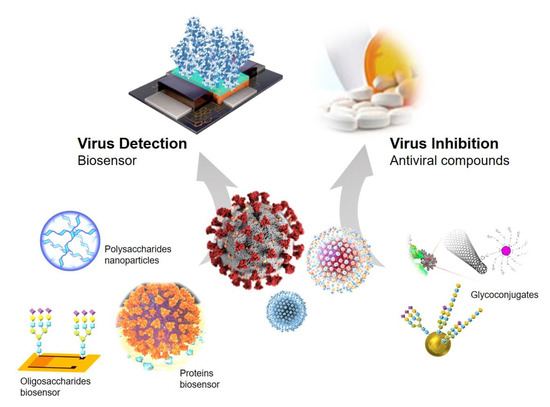

Therefore, in this review we summarized the recent advances in the fabrication of novel functionalized glyconanomaterials, evaluating the effect of different glycomolecules as biomarkers in the recognition of human viruses and the important role in the detection of viral glycoproteins in relevant cases such as the Dengue virus, Ebola virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), influenza virus, Zika virus, and coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 as well as their novel application as potential antiviral agents. Different sections will be focused on proteins, oligosaccharide-functionalized nanomaterials, and glyconanoparticles as biosensors for virus detection and glyconanoconjugates for virus inhibition (Figure 1). Another important kind of virus detection method namely antibody-based was described in a recent review article [16].

Figure 1.

Different glyconanomaterials strategies for application in viral diseases.

2. Proteins or Oligosaccharides Immobilized in Nanomaterials for Glycoprotein-Virus Detection

2.1. Proteins Immobilized in Nanomaterials

One of the most promising strategies for biosensor devices to detect viruses is based on protein-based biosensors [17,18,19,20].

In such cases, some of the main examples using nanomaterials involve the functionalization with lectins, proteins which specifically interact with glycans from glycoproteins. In particular, Concanavalin A (ConA) is a well-known lectin, which binds specifically α-D-mannosyl and α-D-glucosyl residues [21], which are found in the glycoproteins from the viral capsid.

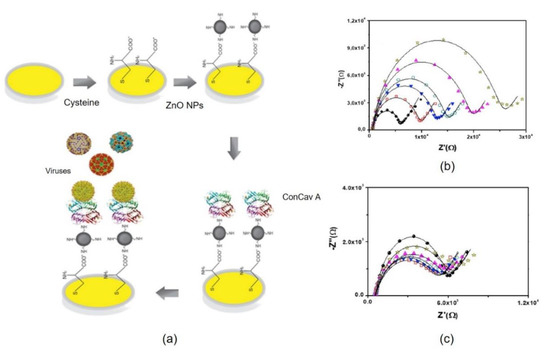

Thus, Oliveira and coworkers [18] developed a biosensor based on cysteine (Cys), zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs) and Concanavalin A lectin (ConA) to differentiate between arbovirus infections. These have become a major global health problem due to recurrent epidemics [22] and nonspecific clinical manifestations have been developed. The reproducibility, sensitivity and specificity of the sensor for Dengue virus type 2 (DENV2), Zika (ZIKV), Chikungunya (CHIKV), and Yellow fever (YFV) were evaluated.

Differences in viral envelope are an essential feature of immune response differentiation after arbovirus infection. The structural components of the viral envelope can be used to identify and differentiate arboviruses [23]. Therefore, the lectin ConA was used in this work for the identification and differentiation of carbohydrates in the viral cover. Atomic force microscopy measurements confirmed the modification of the electrode surface and revealed a heterogeneous topography during the biorecognition process (Figure 2). To characterize the biosensor, they used cyclic voltammetry (CV) and impedance spectroscopy (EIS), showing a linear response at different concentrations of the arboviruses studied. This study demonstrated that ConA recognizes the structural glycoproteins of DENV2, ZIKV, CHIKV, and YFV (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic representation of the surface modification. (b,c) Nyquist diagram of the sensor system (•) and serial dilutions of arboviruses 1:50 (□); 1:40 (∇): 1:30 (⋄); 1:20 (Δ); 1:10 (*) of the virus. (b) ZIKV, (c) DENV2. Figure adapted from ref. [18].

The degree of affinity of the sensor to the virus decreased from ZIKV > DENV2 > CHIKV > YFV. The sensor shows the highest response to ZIKV due to the interaction of ConA with specific carbohydrate residues present in the structural glycoprotein E of ZIKV (Figure 2b). Also, DENV2 showed a high interaction with ConA due to the presence of glucans on its surface (Figure 2c). This binding between ConA and viral glycoproteins reflects the interaction of the biomolecule with carbohydrate residues present in the glycan monomer Ans154 exposed on the surface of DENV2 and ZIKV Virus [24]. These results support the use of the proposed system for the development of biosensors for arbovirus infections.

Another approach in the design of protein-based biosensors focuses on the use of proteins mimicking the carbohydrate-binding receptor of the virus.

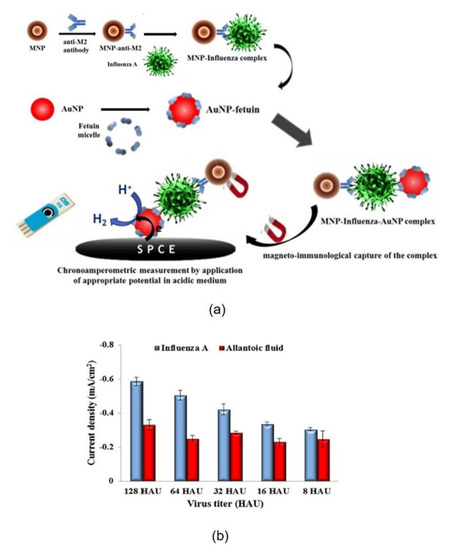

Fetuin-A (FetA, alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein) is a 64-kDa glycoprotein that is found in relatively high concentrations in human serum and recently has been used for the new selective nanobiosensor developed for influenza virus [19]. The strategy is based on a gold nanoparticle chronoamperometric magnetoimmunosensor for the influenza A H9N2 virus (Figure 3). This method is performed in two steps using two specific influenza receptors. The first, anti-matrix protein 2 (M2) antibody, was bound to magnetic iron nanoparticles (MNP) and used for the isolation of the virus from allantoic fluid. The second biomolecule, Fetuin A (alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein), was bound to an electrochemical detectable gold nanoparticle (AuNP) tag, and it was used to detect the adherence advantage of the virus from the fetuin A hemagglutinin interaction (Figure 3). The complex formed by MNP-Influenza virus-AuNP was isolated and treated with an acid solution, then the collected gold nanoparticles were deposited on a screen-printed carbon electrode (Figure 3a). AuNPs catalyze the reduction of hydrogen ions in an acid medium while applying an appropriate potential, and the current signal generated was proportional to the virus titer. Finally, the chronoamperometric detection of the virus was carried out indirectly by quantifying the AuNPs, allowing the rapid detection of influenza virus A (H9N2) with a titer of less than 16 HAU (Figure 3b). This detection system is able to distinguish between virus influenza A and B by taking advantage of the use of anti-M2 antibodies that specifically recognize influenza A virus.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic illustration of the strategy used to develop the gold nanoparticle-based chronoamperometric magnetoimmunosensor for influenza virus; (b) Diagrams correspond to the response of the magnetoimmuno assay to various influenza virus titers ranging from 8 HAU to 128 HAU (blue) and to various concentrations of non-infected allantoic fluid in 1M HCl solution (red). Reprinted with permission from reference [19]. Copyright 2018 Elsevier.

Therefore, this could be a potential diagnostic sensor for clinical applications, because of the advantages of speed, the use of very small sample volumes, and its suitability for the selective determination of the virus from complex real samples.

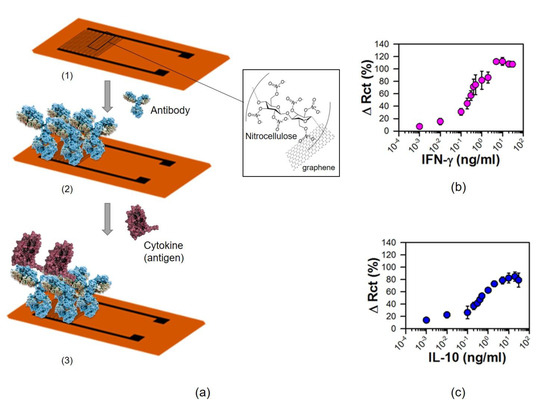

Another strategy for detection of viral infection involves the development of an imm unosensor capable of monitoring cytokines [20]. Cytokines (e.g., interferons, interleukins, etc.) are small proteins (5–20 kDa) important in cell signaling as immunomodulating agents, which are secreted by different immune cells for fighting off infections (Figure 4). Thus, the strategy developed by Hersam, Claussen, and coworkers [20] is based on a flexible graphene interdigitated electrode (IDE) printed with aerosol jet printed graphene (AJP) for electrochemical bioselection (Figure 4a). This system was developed to detect two different cytokines: interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and interleukin 10 (IL-10).

Figure 4.

(a) Schematic representation of fabrication and biofunctionalization of the IDE. (1) AJP graphene IDE on a polyimide (Kapton) sheet. (2) Antibodies selective to IL-10 or IFN-γ immobilized on functionalized graphene. (3) Incubation with antigen. (b,c) IFN-γ and IL-10 detection using graphene IDE sensors. Figure adapted from ref. [20].

A graphene-nitrocellulose ink was printed on a flexible polyimide film (Kapton) in an IDE pattern by aerosolizing graphene and depositing the aerosol mist in highly focused lines. The electrode was chemically modified to generate carboxylic groups as functional groups on the surface for covalent immobilization of anti-bovine antibody (IFN-γ or IL-10) which was then used for detecting the corresponding IFN-γ and IL-10 cytokines (Figure 4a). The system showed a very low detection threshold, with a detection limit of 25 pg/mL for IFN-γ and 46 pg/mL for IL-10 (Figure 4b,c). These detection ranges cover the detectable IFN-γ concentration ranges in the clinical disease stage and fit the newly infected stage to clinical disease (in case of IL-10 concentration ranges) for example of Johne’s disease (a chronic enteritis of ruminants caused by M. paratuberculosis). Furthermore, the biosensor was highly selective towards IFN-γ or IL-10 with negligible cross-reactivity with each other and similar cytokines (i.e, IL-6). Therefore, this example is an interesting example in term of application of glyconanomaterials which can be extended to other current diagnosis systems based on antibody-methods [16] for the indirect detection of different viruses such as HIV, coronavirus, or even other diseases [25].

2.2. Oligosaccharides Immobilized in Nanomaterials

Most viruses recognize glycans on glycoproteins and glycolipids of the mammalian cells as receptors [26], especially heparin sulfate or sialic acid containing oligosaccharides. Thus, novel nanobiosensors have focused on materials functionalized with these glycans [27,28]. In particular, heparin has been successfully used as analog of heparan sulfate in a biosensor as a biorecognition element in place of the traditional antibody for Dengue virus during infection of Vero cells and hepatocytes [29].

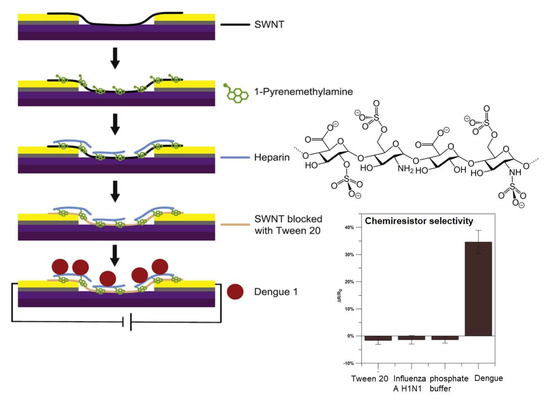

Thus, Yates and coworkers [27] developed a new electronic biosensor based on a single-walled carbon nanotube (SWNT) lattice chemoresistive transducer that is functionalized with heparin, for the rapid, ultrasensitive, and low-cost detection of the whole Dengue virus (DENV) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Glyconanomaterial chemiresistor for detection of Dengue virus. Figure adapted from ref. [27].

Carbon nanotubes were functionalized with pyrenemethylamine by π–π stacking interaction of the pyrene moiety and the SWNT. Then chemical modification was performed to incorporate heparin to the surface. This oligosaccharide is highly sulfated, having the highest negative charge density of any known biological macromolecule, whereas DENV envelope protein has positively charged β-strands located within a well-conserved binding pocket for electrostatic interaction with receptor sulfate groups. Therefore, interaction between the glycan and virus is detected by the resistance on p-type SWNTs. This method was highly selective since a functionalized sensor responded to the presence of DENV but not to influenza H1N1 (Figure 5). A limit of detection of ~8 DENV/chip was obtained with only 10-min incubation of a 10 μL sample.

However, actually the most important developments in glycan-sensors for virus detection have been focused on the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, responsible for the pandemic respiratory disease COVID-19 (starting in December 2019) [30], which to date has caused the death of more than 3 million people worldwide (up to 28 April 2021).

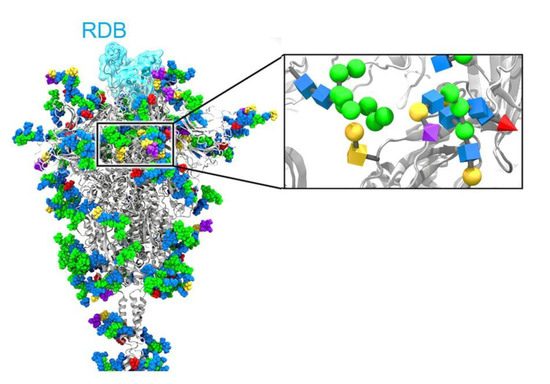

In this context, sialic acids were determined as a receptor (or recognition motif) for the glycoproteins from the coronavirus, especially the spike protein [31]. In SARS-CoV-2 virus, the spike protein is extensively glycosylated, with particular importance for mannose and sialic acid (Figure 6) [32].

Figure 6.

Glycosylated full-length model of the SARS-CoV-2 S protein in the open state where the RBD in the “up” state is highlighted with a transparent cyan surface. N-/O-glycans are shown in Van der Waals representation, where GlcNAc is colored in blue, mannose in green, fucose in red, galactose in yellow, and sialic acid in purple (Magnified view of the S protein stalk glycosylation). Reprinted with permission from reference [32]. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

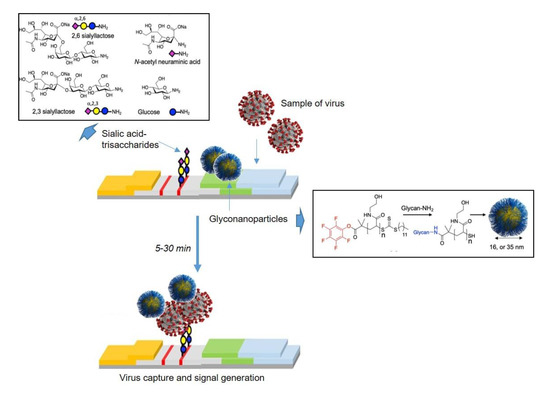

Thus, recently Gibson and coworkers [28] described the synthesis of a glyconanomaterial formed by polymer stabilized, multivalent gold nanoparticles bearing sialic acid derivatives for the interaction with the spike glycoprotein from SARS-CoV-2. They found that sialic acid (α,N-acetyl neuraminic acid) binds to the spike glycoprotein and subsequently they could exploit this interaction as the detection unit in a prototype lateral flow rapid diagnostic, which would not require centralized infrastructure. In this strategy, the glycan was immobilized (as a BSA-glycoconjugate) on the test strip and also in the mobile phase onboard gold nanoparticles, providing multivalence (and hence affinity) for dissecting SARS-CoV-2 binding and for the LFD (lateral flow device) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Design concept for glycolateral flow devices. Figure adapted from ref. [28].

Herein, the nanoparticle design is based on telechelic polymer tethers which conjugate the glycans (sialic acids), by the displacement of an ω-terminal pentafluorophenyl (PFP) group, and immobilization onto gold particles via an α-terminal thiol. In the next reaction step, poly (N-hydroxyethyl acrylamide), PHEA, was chosen as the polymer to give colloidally stable particles (Figure 7) [33].

In contrast, amino-glycans were synthesized by reduction of the anomeric azides and later conjugated to the PHEAs by displacement of the PFP group. Hereinafter, polymers were assembled onto citrate-stabilized gold nanoparticles. Characterization analysis revealed that 35 nm sialyl-lactose particles were the most stable ones and were selected to perform glycan-binding assays. This study replicated a lateral flow situation using protein expressed mammalian cells (HEK) to ensure glycosylation. The assays revealed that in this system sialic acid gave the strongest response and consequently was taken forward. With the successful identification of sialic acid as a target ligand, its application as the capture unit in lateral flow was examined. It is important to highlight that the performance does not only depend on the affinity of the capture ligand but also on the flow of the particles. For this reason, “half” lateral flow assays were established to optimize the particles. The negative test line was (commercial) 2,3-silyllactose-BSA, which the nanoparticle should not bind to (to avoid false positives). The positive control was immobilized SARS-CoV-2 and the sialic acid-AuNPs 35 nm nanoparticles flowed over them. The lateral flow devices could clearly detect the virus-like particles at a concentration of 5 µg/mL protein. Sialic acid particle system had a clear preference for SARS-CoV-2, demonstrating selectivity in this glyconanoparticle system. This data supports the notion that the terminal sialic acid is the key binding motif. Therefore, this system can detect the spike glycoprotein from SARS-CoV-2 virus under 30 min, thus being interesting for the creation of rapid point-of-care diagnostics in a format which requires no infrastructure and limited training.

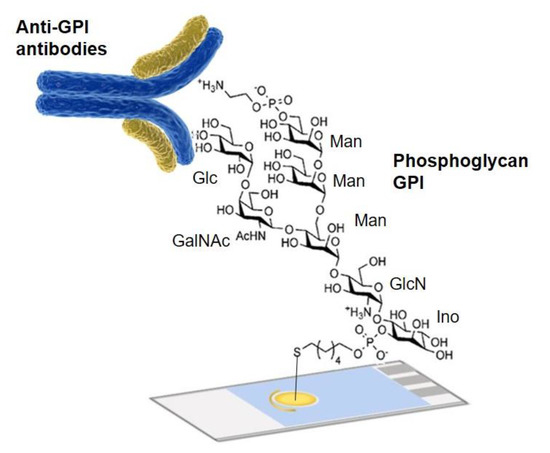

Other glycans with a relevant role in cell communication, signaling and adhesion, also acting as immuno-modulators during infectious diseases are phosphoglycans such as glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) [34]. This molecule has been successfully used for detection of malaria and other diseases [35], by detection of anti-glycan antibodies. This method also holds great potential for the detection of IgG antibodies related to other multiple medical conditions characterized by overexpression of antibodies, for example SARS-CoV-2 [36].

Thus, recently a glycobiosensor based on synthetic GPI was developed by Orozco and coworkers [37] (Figure 8). The system consists of a simple label-free electrochemical biosensor developed for monitoring anti-glycan IgG antibodies in serum from toxoplasmosis seropositive patients. The synthetic GPI consisted of a lipid, a phospho-myo-inositol (Ino), a glucosamine (GlcN), three mannoses (Man), and a phosphoethanolamine (PEtN) forming the EtNP-6Man-α-(1 → 2)-Man-α-(1 → 6)-Man-α-(1 → 4)-GlcN-α-(1 → 6)- Ino-phospholipid glycolipid, having an α-Glc-(1 → 4)-β-GalNAc side branch at the O4-position of the first mannose (Figure 8) [34,35,38].

Figure 8.

Glycosensor device based on immobilized phosphoglycan. Figure adapted from ref. [37].

This phosphoglycan (bioreceptor of T. gondii) was attached to screen-printed gold electrodes (SPAuEs) through a linear alkane thiol phosphodiester and the interaction with antibodies was detected and quantified by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). No significant increase in the Rct (charge transfer resistance) value was observed when the GPI-electrode was incubated with the non-reactive serum whereas an increase was clearly observed with the reactive serum.

Viral infections are associated with around 12% of cancers. Indeed, viruses such as Hepatitis B and C viruses, and human papilloma virus have been shown to contribute to the development of human cancers [39]. Viruses may induce sustained disorders of host cell growth and survival through the genes they express, or may induce DNA damage response in host cells, which in turn increases host genome instability. Moreover, they may induce chronic inflammation and secondary tissue damage favoring the development of oncogenic processes in host cells.

Therefore, another strategy associated with detection of immunoresponses involves the fabrication of oligosaccharide nanoparticles in antitumor therapy [40,41]. Dextran modified glyconanoparticles have been developed in this sense. Nanoparticles such as chitosan cationic nano/microspheres were reported by Pyrc, Szczubiałka and coworkers [42] for selective adsorption of viral particles from aqueous suspensions, which can be useful for the removal of coronaviruses and water purification. N-(2-hydroxypropyl)-3-trimethyl chitosan (HTCC) cationic nano/microspheres were prepared by crosslinking of chitosan with genipin, followed by reaction with glycidyltrimethyl-ammonium chloride (GTMAC). After cytopathic and PCR analyses, these glycoparticles adsorbed in a strong and selective way human coronavirus NL63 (HCoV-NL63).

4. Conclusions

This review emphasized the most recent advances in the design and application of different glyconanomaterials for the detection and inhibition of human viruses. This nanotechnological approach, in which it combines the power of nanomaterials, for example nanoparticles—which have been demonstrated in the last decade to be an important tool for biomedical applications—with glycan molecules—which have a key role in biological recognition systems—opens up timely a future way forward in biomedicine. Advantages of this methodology are for example high sensitivity and efficiency, whereas a potential disadvantage in the case of therapy application is the possible cytotoxicity of these nanomaterials.

Novel systems using tailor-made oligosaccharides or particular proteins were emphasized with their highly sensitive, rapid, and economic features for potential industrial diagnosis kits, in particular of high relevance in the case of the actual pandemic (SARS-CoV-2 virus detection).

Author Contributions

N.L.-G., C.G.-S. and A.A. writing Section 2: proteins or oligosaccharides immobilized in nanomaterials for glycoprotein-virus detection. T.V.-T. writing Section 3: glyconanoconjugates as novel antiviral drugs. J.M.P. for conceiving topic of review article, planning content of review, coordinating overall content and writing, writing the introduction, abstract and conclusions, revising text and content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Spanish Government the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) by Project 201980E081. This work was also sponsored by the Spanish Government (Project No. AGL2017-84614-C2-2-R, AEI/FEDER).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The Authors would like to acknowledge networking support by the COST Action CA18132 (GlycoNanoProbes).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, S.-L.; Wang, Z.-G.; Zhang, Z.-L.; Pang, D.-W. Tracking single viruses infecting their host cells using quantum dots. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 45, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grant, O.C.; Montgomery, D.; Ito, K.; Woods, R.J. Analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein glycan shield reveals implications for immune recognition. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tate, M.D.; Job, E.R.; Deng, Y.-M.; Gunalan, V.; Maurer-Stroh, S.; Reading, P.C. Playing Hide and Seek: How Glycosylation of the Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin Can Modulate the Immune Response to Infection. Viruses 2014, 6, 1294–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baum, L.G.; Cobb, B.A. The direct and indirect effects of glycans on immune function. Glycobiology 2017, 27, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigerust, D.J.; Shepherd, V.L. Virus glycosylation: Role in virulence and immune interactions. Trends Microbiol. 2007, 15, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, M.O.; Angel, M.; Košík, I.; Trovão, N.S.; Zost, S.J.; Gibbs, J.S.; Casalino, L.; Amaro, R.E.; Hensley, S.E.; Nelson, M.I.; et al. Human Influenza A Virus Hemagglutinin Glycan Evolution Follows a Temporal Pattern to a Glycan Limit. mBio 2019, 10, e00204-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Q.; Wu, J.; Nie, J.; Zhang, L.; Hao, H.; Liu, S.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Nie, L.; et al. The impact of mutations in SARS-CoV-2 spike on viral infectivity and antigenicity. Cell 2020, 182, 1284–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization COVID-19 Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Draz, M.S.; Vasan, A.; Muthupandian, A.; Kanakasabapathy, M.K.; Thirumalaraju, P.; Sreeram, A.; Krishnakumar, S.; Yogesh, V.; Lin, W.; Yu, X.G.; et al. Virus detection using nanoparticles and deep neural network–enabled smartphone system. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabd5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.S.; Thomas, M.R.; Budd, J.; Mashamba-Thompson, T.; Herbst, K.; Pillay, D.; Peeling, R.W.; Johnson, A.M.; McKendry, R.A.; Stevens, M.M. Taking connected mobile-health diagnostics of infectious diseases to the field. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 566, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Draz, M.S.; Lakshminaraasimulu, N.K.; Krishnakumar, S.; Battalapalli, D.; Vasan, A.; Kanakasabapathy, M.K.; Sreeram, A.; Kallakuri, S.; Thirumalaraju, P.; Li, Y.; et al. Motion-Based Immunological Detection of Zika Virus Using Pt-Nanomotors and a Cellphone. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 5709–5718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-J.; Wang, S.; Xia, L.; Lv, C.; Tang, H.-W.; Liang, Z.; Xiao, G.; Pang, D.-W. Lipid-Specific Labeling of Enveloped Viruses with Quantum Dots for Single-Virus Tracking. mBio 2020, 11, e00135-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Henríquez, L.; Brenes-Acuña, M.; Castro-Rojas, A.; Cordero-Salmerón, R.; Lopretti-Correa, M.; Vega-Baudrit, J.R. Biosensors for the Detection of Bacterial and Viral Clinical Pathogens. Sensors 2020, 20, 6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varki, A. Biological roles of glycans. Glycobiology 2017, 27, 3–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Su, H.; Luo, Q.; Ye, J.; Tang, N.; Zhang, W.; Chen, W.; Ko, B.C.; et al. Heparin sulphate d-glucosaminyl 3-O-sulfotransferase 3B1 plays a role in HBV replication. Virology 2010, 406, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, L.; Hao, Y.; Deng, D.; Xia, N. Nanomaterials-Based Colorimetric Immunoassays. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alhalaili, B.; Popescu, I.N.; Kamoun, O.; Alzubi, F.; Alawadhia, S.; Vidu, R. Nanobiosensors for the detection of novel c coronavirus 2019-nCoV and other pandemic/epidemic respiratory viruses: A Review. Sensors 2020, 20, 6591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, E.P.; Silva, D.B.; Cordeiro, M.T.; Gil, L.H.; Andrade, C.A.; Oliveira, M.D. Nanostructured impedimetric lectin-based biosensor for arboviruses detection. Talanta 2020, 208, 120338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayhi, M.; Ouerghi, O.; Belgacem, K.; Arbi, M.; Tepeli, Y.; Ghram, A.; Anik, Ü.; Österlund, L.; Laouini, D.; Diouani, M.F. Electrochemical detection of influenza virus H9N2 based on both immunomagnetic extraction and gold catalysis using an immobilization-free screen printed carbon microelectrode. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 107, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parate, K.; Rangnekar, S.V.; Jing, D.; Mendivelso-Perez, D.L.; Ding, S.; Secor, E.B.; Smith, E.A.; Hostetter, J.; Hersam, M.C.; Claussen, J.C. Aerosol-Jet-Printed Graphene Immunosensor for Label-Free Cytokine Monitoring in Serum. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 8592–8603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loris, R.; Hamelryck, T.; Bouckaert, J.; Wyns, L. Legume lectin structure. Biochim. Biophys. Act. (BBA) Prot. Struct. Mol. Enzym. 1998, 1383, 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Murray, N.E.A.; Quam, M. Epidemiology of dengue: Past, present and future prospects. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013, 5, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuno, G.; Chang, G.-J.J. Biological Transmission of Arboviruses: Reexamination of and New Insights into Components, Mechanisms, and Unique Traits as Well as Their Evolutionary Trends. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 18, 608–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sirohi, D.; Chen, Z.; Sun, L.; Klose, T.; Pierson, T.C.; Rossmann, M.G.; Kuhn, R.J. The 3.8 A resolution cryo-EM structure of Zika virus. Science 2016, 352, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carinelli, S.; Martí, M.; Alegret, S.; Pividori, M.I. Biomarker detection of global infectious diseases based on magnetic particles. New Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.J.; de Vries, R.; Paulson, J.C. Virus recognition of glycan receptors. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2019, 34, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasik, D.; Mulchandani, A.; Yates, M.V. A heparin-functionalized carbon nanotube-based affinity biosensor for dengue virus. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 91, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.N.; Richards, S.-J.; Guy, C.S.; Congdon, T.R.; Hasan, M.; Zwetsloot, A.J.; Gallo, A.; Lewandowski, J.R.; Stansfeld, P.J.; Straube, A.; et al. The SARS-COV-2 Spike protein binds sialic acdis and enables rapid detection in a lateral flow point of care diagnostic device. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 2046–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okemoto-Nakamura, Y.; Someya, K.; Yamaji, T.; Saito, K.; Takeda, M.; Hanada, K. Poliovirus-nonsusceptible Vero cell line for the World Health Organization global action plan. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Situation Report—71. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). WHO, 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int (accessed on 11 April 2020).

- Tortorici, M.A.; Walls, A.C.; Lang, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Koerhuis, D.; Boons, G.-J.; Bosch, B.-J.; Rey, F.A.; De Groot, R.J.; et al. Structural basis for human coronavirus attachment to sialic acid receptors. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019, 26, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Casalino, L.; Gaieb, Z.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hjorth, C.K.; Dommer, A.C.; Harbison, A.M.; Fogarty, C.A.; Barros, E.P.; Taylor, B.C.; McLellan, J.S.; et al. Beyond Shielding: The Roles of Glycans in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 1722–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götze, S.; Azzouz, N.; Tsai, Y.H.; Groß, U.; Reinhardt, A.; Anish, C.; Seeberger, P.H.; Silva, D.V. Diagnosis of toxo-plasmosis using a synthetic glycosylphosphatidyl-inositol glycan. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 13701–13705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Anilkumar, A.A.; Mayor, S. GPI-anchored protein organization and dynamics at the cell surface. J. Lipid Res. 2016, 57, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsai, Y.-H.; Liu, X.; Seeberger, P.H. Chemical Biology of Glycosylphosphatidylinositol Anchors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11438–11456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D.L.; Gildersleeve, J.C. Abnormal antibodies to self-carbohydrates in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. Europe PMC. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverri, D.; Garg, M.; Silva, D.V.; Orozco, J. Phosphoglycan-sensitized platform for specific detection of anti-glycan IgG and IgM antibodies in serum. Talanta 2020, 217, 121117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, T.; Fujita, M.; Maeda, Y. Biosynthesis, remodelling and functions of mammalian GPI-anchored proteins: Recent progress. J. Biochem. 2008, 144, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashiro, H.; Brenner, M.K. Immunotherapy against cancer-related viruses. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wannasarit, S.; Wang, S.; Figueiredo, P.; Trujillo, C.; Eburnea, F.; Simón-Gracia, L.; Correia, A.; Ding, Y.; Teesalu, T.; Liu, D.; et al. A virus-mimicking pH-responsive acetalated dextran-based membrane-active polymeric nanoparticle for intracellular delivery of antitumor therapeutics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1905352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, D.; Hobernik, D.; Konhäuser, M.; Bros, M.; Wich, P.R. Surface modification of polysaccharide-based nano-particles with PEG and dextran and the effects on immune cell binding and stimulatory characteristics. Mol. Pharm. 2017, 14, 4403–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciejka, J.; Wolski, K.; Nowakowska, M.; Pyrc, K.; Szczubiałka, K. Biopolymeric nano/microspheres for selective and reversible adsorptionof coronaviruses. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 76, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, C.; Thompson, C.D.; Roberts, J.N.; Müller, M.; Lowy, D.R.; Schiller, J.T. Carrageenan Is a Potent Inhibitor of Papillomavirus Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2006, 2, e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Soria-Martinez, L.; Bauer, S.; Giesler, M.; Schelhaas, S.; Materlik, J.; Janus, K.A.; Pierzyna, P.; Becker, M.; Snyder, N.L.; Hartmann, L.; et al. Prophylactic Antiviral Activity of Sulfated Glycomimetic Oligomers and Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 5252–5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesener, D.A.; Dugan, A.; Kiessling, L.L. Recognition of microbial glycans by soluble human lectins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2017, 44, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baribaud, F.; Doms, R.W.; Pöhlmann, S. The role of DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR in HIV and Ebola virus infection: Can potential therapeutics block virus transmission and dissemination? Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2002, 6, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, L.; Ramos-Soriano, J.; Pérez-Sánchez, A.; Illescas, B.M.; Muñoz, A.; Luczkowiak, J.; LaSala, F.; Rojo, J.; Delgado, R.; Martín, N. Nanocarbon-Based Glycoconjugates as Multivalent Inhibitors of Ebola Virus Infection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9891–9898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compostella, F.; Pitirollo, O.; Silvestri, A.; Polito, L. Glyco-gold nanoparticles: Synthesis and applications. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 1008–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

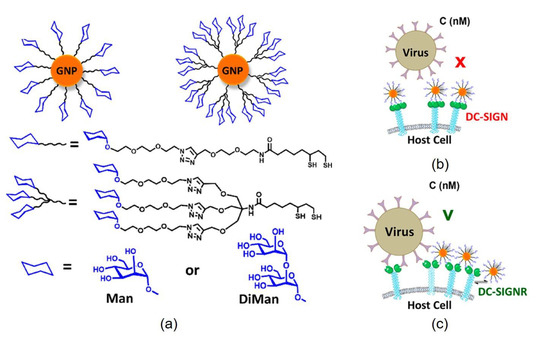

- Budhadev, D.; Poole, E.; Nehlmeier, I.; Liu, Y.; Hooper, J.; Kalverda, E.; Akshath, U.S.; Hondow, N.; Turnbull, W.B.; Pöhlmann, S.; et al. Glycan-Gold Nanoparticles as Multifunctional Probes for Multivalent Lectin–Carbohydrate Binding: Implications for Blocking Virus Infection and Nanoparticle Assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 18022–18034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).