Abstract

Craniofacial bone defects are one of the biggest clinical challenges in regenerative medicine, with secondary autologous bone grafting being the gold-standard technique. The development of new three-dimensional matrices intends to overcome the disadvantages of the gold-standard method. The aim of this paper is to put forth an in-depth review regarding the clinical efficiency of available 3D printed biomaterials for the correction of alveolar bone defects. A survey was carried out using the following databases: PubMed via Medline, Cochrane Library, Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE, and gray literature. The inclusion criteria applied were the following: in vitro, in vivo, ex vivo, and clinical studies; and studies that assessed bone regeneration resorting to 3D printed biomaterials. The risk of bias of the in vitro and in vivo studies was performed using the guidelines for the reporting of pre-clinical studies on dental materials by Faggion Jr and the SYRCLE risk of bias tool, respectively. In total, 92 publications were included in the final sample. The most reported three-dimensional biomaterials were the PCL matrix, β-TCP matrix, and hydroxyapatite matrix. These biomaterials can be combined with different polymers and bioactive molecules such as rBMP-2. Most of the included studies had a high risk of bias. Despite the advances in the research on new three-dimensionally printed biomaterials in bone regeneration, the existing results are not sufficient to justify the application of these biomaterials in routine clinical practice.

1. Introduction

Craniofacial defects can originate from an array of etiological factors including congenital malformations, trauma, infection, rejection or implant failure, infection of bone graft, osteomyelitis, or surgical removal of tumors [1,2,3]. The craniofacial bone can also be impacted by systemic conditions such as osteodegenerative illnesses such as osteoporosis and arthritis, other impactful conditions include osteogenesis imperfecta and bone fibrous dysplasia [4]. All these conditions will compromise functional aspects such as phonation, mastication, and swallowing, which in turn affect the patient’s quality of life [5,6]. The two most common craniofacial bone defects are cancer of the head and neck and cleft lip and palate (CLP) [5,6,7,8,9]. CLP is a multifactorial pathology with several genetic and epigenetic factors as well as environmental factors such as geographical location, socioeconomical factors, and race [10,11]. In an attempt to minimize anomalies resulting from CLP, multidisciplinary treatment is initiated from birth and carries on into adulthood in order to achieve optimal results [12].

During the mixed dentition stage, individuals with CLP may require a secondary alveolar bone graft. During this period, this approach can result in relevant improvements such as closure of oronasal fistulae, stabilization of the two maxillary segments, and enhanced support of the alar base, which, in turn, will improve nasal and labial symmetry [13,14]. The secondary alveolar bone graft was introduced by Boyne and Sands in 1972 and it is currently regarded as the gold standard with the iliac crest being the most frequently chosen donor location [13]. In order to assert the proper timing to perform this procedure, the upper canine should have two thirds of its root developed which usually occurs between the ages of 9 and 11 [13].

The autologous bone graft can present with a variety of setbacks including limited amount of grafted bone, immune response risks, procedure time, and heavy costs. Additionally, a year after the procedure, bone reabsorption will happen in 40% of cases creating the need for re-intervention [15,16]. The main donor sites of autologous bone in craniomaxillofacial surgery are iliac crest graft and calvarial graft, but intraoral graft is also a possibility [17]. Currently, regenerative medicine has been established as a viable alternative in treatment of bone defects including CLP [18,19,20,21]. This approach can modulate the bone regeneration process and inflammation and enhance the healing process. Various biomaterials have been developed with the intent of overcoming the limitations of conventional bone grafts [22], such as heterologous or homologous bone graft [23,24]. These substituting materials can be used on their own or combined with an autologous bone graft and/or matrices. The most recognized tissue regeneration approach in the literature in the treatment of alveolar bone defects is bone morphogenetic protein 2 [25,26]. This approach provides comparable outcomes concerning bone volume, filling, and height to the gold standard technique with the iliac crest bone graft [26].

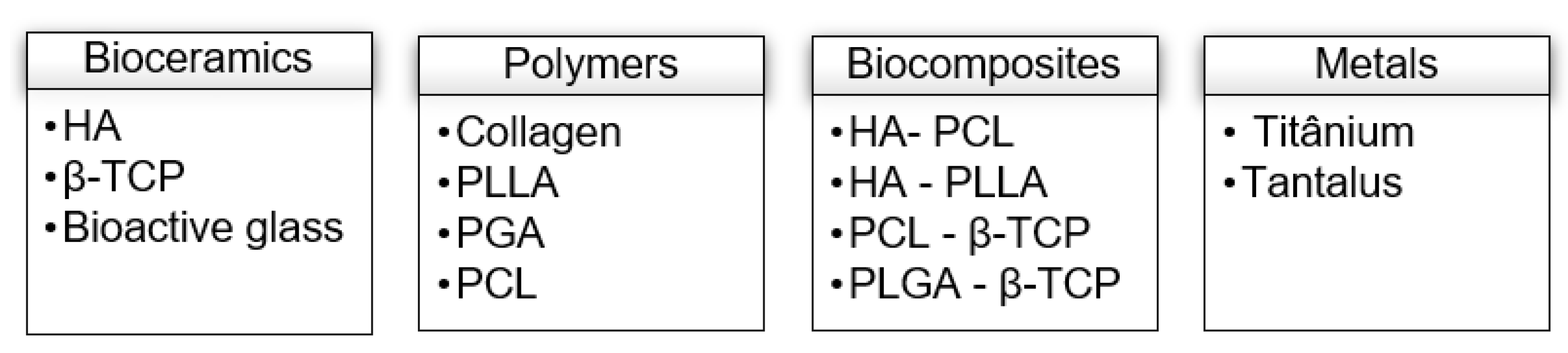

The matrices (Figure 1) are a subtract that allow for cell differentiation and proliferation. Their biocompatibility, biodegradability, osteoconduction, and mechanical properties are characteristics which can influence the success rate of the bone regeneration process [27].

Figure 1.

Most used matrices in bone regeneration. HA—Hydroxyapatite; β-TCP—β-tricalcicum-phosphate; PLLA—Polylactic acid; PGA—Glycolic acid; PCL—Polycaprolactone.

These matrices can be three-dimensional (3D) printed enhancing its adaptation to the bone defect. With the use of 3D technologies, these matrices can be created and adapted according to the specific needs of each patient by changing their internal and external structures whilst using different materials [27,28].

The most commonly used matrices in bone defect treatment are bioceramic and are usually made out of hydroxyapatite (HA) or β-tricalcicum-phosphate (β-TCP). These materials are highly biocompatible and with osteoinductive abilities while also promoting rapid bone formation [29]. Despite a general increase of interest regarding 3D printed biomaterials in recent years, a comprehensive study regarding the general effectiveness of these biomaterials is lacking. To clarify this, we conducted a scoping review to assess the effectiveness of 3D printed biomaterials in the treatment of alveolar defects, which would be helpful for readership since it synthesizes what we know and the best future clinical approach in a single paper. Moreover, this knowledge will allow sustaining the realization of new future clinical studies. The aim of this paper is to put forth an in-depth review regarding the clinical efficiency of available 3D printed biomaterials for the correction of alveolar bone defects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Research and Selection Strategy

Literature research was conducted on the PubMed data base via Medline, Cochrane Library, Web of Science Core Collection, EMBASE, and in gray literature. The last search was done, independently, on the 15th of August 2022 by two researchers.

A combination of Medical Subject Headings (Mesh) along with free text words were used in each of the databases (Appendix A). The following language filters were used: Portuguese, English, Spanish, and French. No filters were used regarding date of publication.

Two researchers initially scrutinized the articles independently by title and abstract. Subsequently, the articles were evaluated according to their full integral text; if doubts arose regarding the inclusion of a certain article, a third researcher was consulted.

The considered studies had to comply with the following inclusion criteria: in vitro, in vivo, ex vivo, and clinical studies; and studies that assessed bone regeneration resorting to 3D printed biomaterials. The exclusion criteria applied were as follows: non-clinical studies and every other type of research (editorials, academic books, and reports); case reports or descriptive studies; duplicated studies; studies with incomplete data; and studies that merely reported on the characterization of a new biomaterial without reporting on bone regeneration rates.

2.2. Data Extraction

After the eligibility process, the articles were sorted into different categories according to the type of study: in vitro, in vivo, ex vivo, or clinical. From each selected article, the following information was extracted: authors, date of publication, study design, experimental and control group, evaluation time, bone regeneration assessment method, results, and main conclusions.

2.3. Risk of Bias

The bias risk of the in vitro studies was obtained using the Faggion Jr. norms for pre-clinical studies regarding dental materials [30]. For the in vivo studies, the bias risk tool from the Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory Animal Experimentation (SYRCLE) was used.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

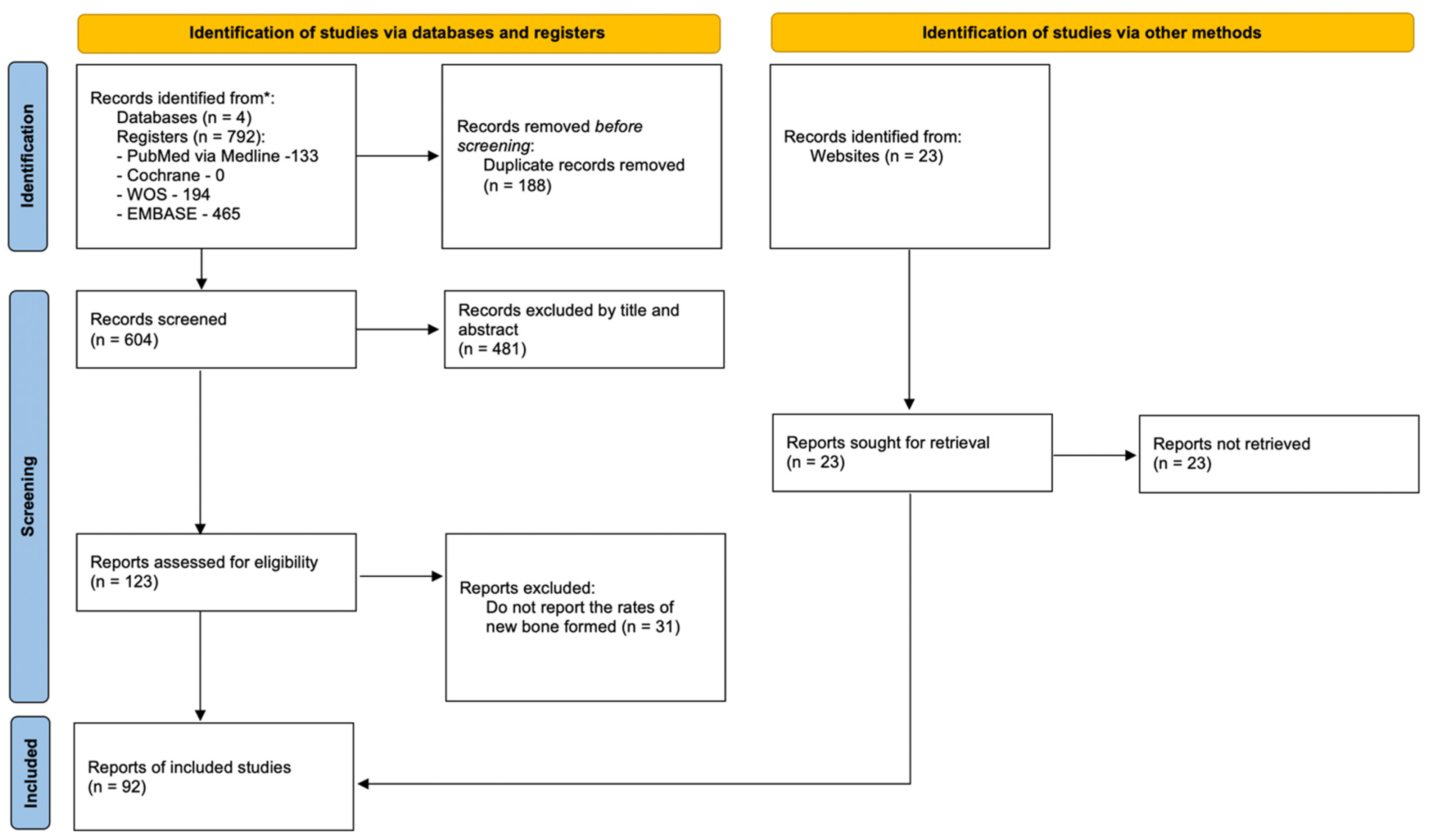

The initial search, performed on the previously mentioned databases, gathered 792 studies. After removing duplicates, 604 studies were scrutinized according to title and abstract. Afterwards, all references deemed irrelevant for this systematic review were excluded, resulting in 123 potentially relevant studies. Given that 31 articles did not report bone regeneration rates, only 92 references were included in the final sample. The identification, screening and eligibility process is summarized in the flow chart (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart.

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2.1. In Vitro Studies

Fifty-one articles analyzed the properties of biomaterials in vitro. The year of publication ranged from 2015 to 2022, with the exception of one study conducted in 2006 [31]. The most commonly used biomaterial in the control group was PCL matrix, followed by β-TCP and PLLA. Osteogenic activity through alkaline phosphatase was the most widely used method to assess bone regeneration, having been described in 26 articles. Seventy- two studies evaluated bone regeneration through the expression of osteogenesis-related genes. Only one study [32] reported the release rate of growth factors. On the other hand, one study [33] evaluated the porosity of the matrix and found that the presence of nanotubes is associated with more favorable results for osteogenesis when compared to larger pores. Table 1 summarizes the results of the in vitro studies included in this systematic review.

Table 1.

Characteristics of in vitro studies.

3.2.2. In Vivo Studies

In vivo bone regeneration was evaluated in 75 articles, published between 2015 and 2022, in various animal species, such as New Zealand rabbits, beagle dogs, and rat models. The number of animals used in each study ranged from 3 to 120, with seven articles not reporting the sample size [30,31,82,83,84,85].

The most commonly used biomaterial in the control group was β-TCP matrix, followed by PCL matrix. Regarding the evaluation method, microcomputerized tomography was the most used followed by histology. Other methods used were real-time polymerase chain reaction [42,86] and immunohistochemistry [87].

The most refracted matrices were PCL, β-TCP, and HA. In seven articles, the matrix of the experimental group contained bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) [28,42,45,49,88,89]. Bone regeneration was superior in all experimental groups, with the exception of three articles [90,91,92], which found similar values between the control and experimental group. Regarding secondary outcomes, Van Hede et al. [73] analyzed matrix geometry, and found that the gyroid geometry results in better outcomes when compared to the orthogonal one. Chang et al. [43] found that combining HA matrix with an oxidized RGD peptide in a high stiffness matrix may be advantageous for maxillofacial regeneration when compared to low stiffness matrices.

Table 2 summarizes the results of the in vivo studies included in the present systematic review.

Table 2.

Characteristics of in vivo studies.

3.3. Synthesis of Quantitative Evidence

In the various studies evaluated, many different biomaterials are described. The most referenced biomaterial was β-tricalcium phosphate (β -TCP), used in 16 in vitro studies and 27 in vivo studies. The second most referenced biomaterial was polycaprolactone (PCL), mentioned in 16 in vitro studies and 20 in vivo studies. Hydroxyapatite (HA) was the third most used biomaterial, in 7 in vitro and 16 in vivo studies. There are other biomaterials/biomolecules that were used in more than 3 studies, namely: decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM), human recombinant bone protein type 2 (RhBMP-2), collagen, polylactic acid (PLLA), polylactic acid-co-glycolic acid (PLGA), calcium sulfate (SC), and different types of hydrogel (e.g., bone-derived extracellular matrix, β-TCP, cell-laden, nanocomposite, MicroRNA). All other biomaterials are mentioned only in a few studies, generating a multitude of results, which makes them difficult to analyze, and, consequently, to draw conclusions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Biomaterials described in the included studies (in vitro and in vivo).

The most used evaluation method was different in in vitro and in vivo studies. In the first ones, the most frequent methods were the following: determination of osteogenesis-related gene expression by qRT-PCR (27 studies), and the evaluation of alkaline phosphatase activity, a mineralization precursor protein, by p-nitrophenol assay (9 studies), and by a staining assay with the AKT assay kit (7 studies). In in vivo studies, radiological methods such as micro-CT (57 studies) and histological methods (56 studies) are the most used (Table 4).

Table 4.

Analysis of evaluation methods in in vitro and in vivo studies.

The most used 3D printing technique mentioned in both types of studies is extrusion-based 3D printing (23 in vitro studies and 27 in vivo studies). However, there are other techniques used simultaneously in in vitro and in vivo studies, namely: fused deposition modeling (6 and 10, respectively), stereolithography (2 and 7, respectively), and laser sintering technique (3 in both). Other techniques are used, but only occasionally in 1 or 2 studies (Table 5).

Table 5.

Analysis of biomaterials 3D printing techniques in in vitro and in vivo studies.

3.4. Risk of Bias

The risk of bias of the in vitro and in vivo studies is summarized in Table 6 and Table 7, respectively. Regarding in vitro studies, none described the methodology to implementation sample. All in vivo studies also lacked information regarding sample allocation, allocation randomization process methodology, implementation, and protocol. All but three of the articles disclose information regarding study financing.

Table 6.

Risk of bias of in vitro studies.

Table 7.

Risk of bias of in vivo studies.

Regarding in vivo studies, most of the studies have serious methodological flaws, leaving out pivotal information such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, and blinding. Only six studies specify investigator blindness as a factor during outcome assessment. Lastly, seven other studies report no additional bias sources.

4. Discussion

The aim of the present systematic review was to report the current state of the art regarding the clinical efficiency of available 3D printed biomaterials for the correction of alveolar bone defects. Although the quantitative analysis of the results could not be executed due to the heterogeneity of the studies, the qualitative analysis allowed for a better understanding and evaluation of the published studies.

The conventional technique requires an autologous graft of cancellous bone and is considered the gold standard [13]. However, with the limited offer of donor bone as well as the bone reabsorption rate due to its adaptability to the defect site, a re-intervention may be necessary [15,16]. In an attempt to diminish these limitations, studies have been carried out in order to explore different approaches that can accelerate bone formation, reduce bone reabsorption and improve soft tissue scarring. 3D printed biomaterials can be specifically made to adapt to the bone defect site; this has led to an increase in studies regarding this topic over the last five years [27,28].

Out of the 75 in vivo studies included, 17 evaluated the efficiency of the PCL matrix [32,35,37,50,51,52,53,54,55,62,63,65,66,73,77,81,120]. This biomaterial is the most well reviewed biomaterial in literature due to its high biocompatibility, durability and subsequent extensive use [37]. Despite its low degradation rate, the PCL matrix is limited in terms of cellular adhesion and osteogenic differentiation, several authors [32,35,49,50,53,62] have suggested combining it with different polymers [37] and bioactive molecules such as rBMP-2, that promote proliferation and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into osteoblasts resulting in bone formation. Nonetheless, a recently published umbrella review regarding the efficiency of current approaches in regeneration of bone defects in non-syndromic patients with cleft palate concluded that rBMP2 seems to provide results similar to the iliac crest bone graft in terms of bone volume and vertical dimension [121]. Another limitation of the PCL matrix is its low hydrophilia [52], which can be amended when the matrix is combined with a hydrophilic material such as β -TCP [35,66,77] or polydopamine [37]. With the addition of graphene, the PCL matrix increases its capacity to induce the secretion of growth factors that boost angiogenesis [56].

The β-TCP matrix was reportedly used in 12 in vitro and 30 in vivo studies. This calcium phosphate bioceramic presents ideal biocompatibility and osteoconductivity [36,64,85]. In addition to those characteristics, the β-TCP matrix also contains components similar to the bone tissue apatite along with a good balance between reabsorption and degradation during bone formation. Despite all these attributes, the osteogenic abilities of this biomaterial showed subpar results when used in large bone defects [35,48,64] and thus falling short when compared to the autologous bone graft [70].

The hydroxyapatite matrix is one of the most referenced bioceramics in in vivo studies. When combined with β-TCP this matrix becomes highly biocompatible and with a great osteointegration rate [88,90,123]. However, more studies are required in order to fully understand the macro-design that can optimize bone regeneration [90]. Since the bone formation process involves the immune system, this can be modulated by biomaterials such as esphingosine-1-phosphate (S1O) which has been linked to the β-TCP matrix. This sphingolipid has been shown to increase the expression of genes related to osteogenesis, such as osteoporin (OPN), transcribing factor 2 related to a runt (RUNX2), and osteocalcin (OCN) [36]. In addition to this, the combination of β-TCP with strontium oxide (SrO), sillica (SiO2), magnesium (MgO), and zinc (ZnO) also proved to be effective in bone regeneration due to alterations in the physical and mechanical properties of the matrix [48].

Regarding PRF, this biomaterial can improve the reconstruction of the alveolar cleft. It is prepared from centrifuged autologous blood formed by a fibrin matrix that contains platelets, white blood cells, growth factors and cytokines. These factors may promote the uniqueness and differentiation pathways of osteoblasts, endothelial cells, chondrocytes, and various sources of fibroblasts, stimulating the regenerative capacity of the periosteum. Furthermore, the fibrous structure of PRF acts as a three-dimensional fibrin scaffold for cell migration [16]. In this way, PRF can be used with a bone substitute, allowing wound sealing, homeostasis, bone union, and graft stability [16]. In contrast, BMP-2 is usually applied in alloplastic bone grafts or scaffolding and is an effective inducer of bone and cartilaginous formation. Its application avoids the limitation of autologous bone grafts, which may be related to the shorter operative and hospitalization time. However, it has some adverse effects, such as nasal stenosis and localized edema at the graft site [26].

Another promising candidate for bone regeneration is the pure Zn L-PBF porous scaffold [74]. It presented relatively adjusted deterioration rates and mechanical strength for bone implants. Furthermore, they also showed well in vitro cytocompatibility with MC3T3-E1 cells and osteogenic capacity for hBMMSCs. The in vivo implantation results showed that pure Zn scaffolds have potential for applications in large bone defects with osteogenic properties [74].

Additionally, the microstructure of the matrices such as porosity, pore size, and structure play a very important role in cell viability and bone growth [115]. In contrast to traditional methods, the development of three-dimensional printing allows for the control of the microstructure. Therefore, a wide variety of materials and techniques are available to optimize the matrix [124]. Shim et al. reported that porosity affects osteogenesis, with matrices with 30% porosity showing better osteogenic capacity than groups with 50% and 70% porosity [115]. Regarding pore size, the literature suggests that the ideal size should be between 400 to 600 μm [63,103,111]. Finally, the pore configuration should also be considered in terms of the dynamic stability of the matrix. Recently, matrices with hierarchical structures have been studied. Zhang et al. demonstrated that tantalum matrices with hierarchical structures exhibited excellent hydrophilicity, biocompatibility, and osteogenic properties [33]. However, in the future, additional in vivo studies are required as to understand what structure the matrix should present in order to find a balance between cell viability and mechanical properties of the biomaterial, optimizing bone regeneration.

This systematic review presents some limitations that may alter the interpretation of the results, namely: (1) some of the included studies present a small sample size with only three animals; (2) the included studies present high risk of bias; (3) lack of evaluation of variables that interfere with bone regeneration, such as the position of the teeth in the bone graft, the width of the defect, the volume of grafted bone and the experience of the clinician; (4) absence of clinical studies; (5) heterogeneity of the studies in terms of matrix typology and follow-up used may difficult outcome assessment. Due to the heterogeneity in the methodology of the included studies, most of the studies selected in this systematic review were classified as having a high risk of bias, which may decrease the certainty of the results. According to the risk of bias analysis, the analyzed parameters with the highest risk of bias were sample allocation, allocation randomization process methodology, implementation, and protocol. These factors must be considered when figuring out the results of this review. The methodology of the several studies evaluated is very different and is not described enough, which makes their effective comparison impossible. Since there are numerous types of biomaterials/biomolecules and various combinations between them, future studies should define the most appropriate methodology, creating guidelines for its implementation and subsequent comparison.

In addition, future studies should be calibrated in order to use similar parameters and protocols, providing stronger evidence, focusing on the most described materials, namely β-tricalcium phosphate, polycaprolactone, hydroxyapatite with decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM), human recombinant bone protein type 2 (RhBMP-2), collagen, polylactic acid (PLLA), poly(lactic acid-co-glycolic acid (PLGA), and calcium sulfate (CS). Moreover, these promising materials should be evaluated and compared to each other in a single study in order to obtain more effective and clinically applicable conclusions. In the future, additional studies should be performed, more specifically blinded randomized studies with increased control of possible bias sources namely, the randomization process, concealment of the investigators of the experimental groups and description of the limitations of the studies. Moreover, the cost-effectiveness of the proposed new regenerative strategies should be evaluated, as it plays a crucial role in clinical decision making in healthcare systems, especially public institutions.

Lastly, future systematic reviews focused on 3D biomaterials should include only the most referenced evaluation and printing techniques. Therefore, for in vitro systematic reviews, the authors should compare PCL, b-TCP, RhBMP-2, and HA biomaterials created by extrusion printing, fused deposition, stereolithography, or laser sintering techniques. The chosen evaluation methodology should be gene expression by qRT-PCR and alkaline phosphatase activity. On the other hand, for in vivo systematic reviews, the authors should analyze the same biomaterials and the same technique printing, but the evaluation methodology should be based on radiology imaging and histology.

5. Conclusions

The most reported three-dimensional biomaterials were the PCL matrix, β-TCP matrix, and hydroxyapatite matrix. Despite the advances in the research on new three-dimensionally printed biomaterials in bone regeneration, the existing results are not sufficient to justify the application of these biomaterials in routine clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.F. and F.V.; methodology, E.C., C.M.M. and A.B.P.; validation, C.N. and R.T.; formal analysis, F.M. and F.P.; investigation, Â.B. and I.F.; data curation, C.N. and R.T.; writing, Â.B. and M.P.R.; writing—review and editing, I.F., C.M.M. and A.B.P.; visualization, E.C., F.M. and F.P.; supervision, I.F. and F.V.; project administration, F.V. and E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Database | Search Phrase |

| Pubmed via Medline and Cochrane Library | (“Printing, Three-Dimensional” [Mesh] OR “Printing, Three Dimensional” OR “Printings, Three-Dimensional” OR “Three-Dimensional Printings” OR “3-Dimensional Printing*” OR “3 Dimensional Printing*” OR “Printing, 3-Dimensional” OR “Printings, 3-Dimensional” OR “3-D Printing*” OR “3 D Printing*” OR “Printing, 3-D” OR “Printings, 3-D” OR “Three-Dimensional Printing” OR “Three Dimensional Printing” OR “3D Printing*” OR “Printing, 3D” OR “Printings, 3D”) AND (“Bone Regeneration”[Mesh] OR “Bone Regenerations*” OR “Regeneration, Bone” OR “Regenerations, Bone” OR Osteoconduction OR “Alveolar Bone Grafting”[Mesh] OR “alveolar bone grafting*” OR “Alveolar Cleft Grafting” OR “bone graft*” OR “Bone Substitutes”[Mesh] OR “bone substitute*” OR “Replacement Material, Bone” OR “Replacement Materials, Bone” OR “Materials, Bone Replacement” OR “Substitute, Bone” OR “Substitutes, Bone” OR “Bone Replacement Material*” OR “Material, Bone Replacement” ) AND (Dentistry[Mesh] OR dentistry OR oral* OR orofacial OR dental* OR maxillofacial OR “Surgery, Oral”[Mesh] OR “surgery, oral” OR “Maxillofacial Surgery” OR “Surgery, Maxillofacial” OR “Oral Surgery” OR “Cleft Palate”[Mesh] OR “cleft palate*” OR “Palate, Cleft” OR “Palates, Cleft” OR “Cleft Palate, Isolated”) |

| Web of Science Core Collection (WOS) | TS = (“Print*, Three Dimensional” OR “Three-Dimensional Print*” OR “3-Dimensional Print*” OR “3 Dimensional Print*” OR “Print*, 3-Dimensional” OR “3-D Print*” OR “3D Print*” OR “Print*, 3-D” OR “ Print*, 3D”) AND TS = ( “Regenerati*, Bone” OR “Bone Regenerati*” OR osteoconduction OR “Alveolar Bone Graft*” OR “alveolar cleft grafting“ OR “bone graft*” OR “Replacement Material*, Bone” OR “Material*, Bone Replacement” OR “Substitute*, Bone” OR “Bone Replacement Material*” OR “ Material, Bone Replacement” OR “bone substitute*”) AND TS = (dent* OR oral* OR orofacial OR maxillofacial OR “Surgery, Oral” OR “oral surgery”) |

| EMBASE | (‘printing, three dimensional’/exp OR ‘printing, three dimensional’ OR ‘printings, three-dimensional’ OR ‘three-dimensional printings’ OR ‘3-dimensional printing*’ OR ‘3 dimensional printing*’ OR ‘printing, 3-dimensional’ OR ‘printings, 3-dimensional’ OR ‘3-d printing*’ OR ‘3 d printing*’ OR ‘printing, 3-d’ OR ‘printings, 3-d’ OR ‘three-dimensional printing’/exp OR ‘three-dimensional printing’ OR ‘three dimensional printing’/exp OR ‘three dimensional printing’ OR ‘3d printing*’ OR ‘printing, 3d’ OR ‘printings, 3d’) AND (‘bone regeneration’/exp OR ‘bone regeneration’ OR ‘regeneration, bone’/exp OR ‘regeneration, bone’ OR ‘regenerations, bone’ OR ’osteoconduction’/exp OR osteoconduction OR ‘alveolar bone grafting’/exp OR ‘alveolar bone grafting’ OR ‘alveolar cleft grafting’ OR ‘bone graft*’ OR ‘bone graft’/exp OR ‘bone graft’ OR ‘bone transplantation’/exp OR ‘bone transplantation’ OR ‘bone prosthesis’/exp OR ‘bone prosthesis’ OR ‘bone substitute*’ OR ‘replacement material, bone’ OR ‘replacement materials, bone’ OR ‘materials, bone replacement’ OR ‘substitute, bone’ OR ‘substitutes, bone’ OR ‘bone replacement material*’ OR ‘material, bone replacement’) AND (dentistry OR ‘dentistry’/exp OR ‘dentistry’ OR oral OR orofacial OR ‘dental’/exp OR dental OR maxillofacial OR ‘oral surgery’/exp OR ‘oral surgery’) |

References

- Robey, P.G. Cell Sources for Bone Regeneration: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (But Promising). Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2011, 17, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhumiratana, S.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G. Concise Review: Personalized Human Bone Grafts for Reconstructing Head and Face. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2012, 1, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, M.D.; Xu, H.H.K. Culture Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells with Calcium Phosphate Cement Scaffolds for Bone Repair. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2010, 93B, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illich, D.J.; Demir, N.; Stojković, M.; Scheer, M.; Rothamel, D.; Neugebauer, J.; Hescheler, J.; Zöller, J.E. Concise Review: Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells and Lineage Reprogramming: Prospects for Bone Regeneration. Stem Cells 2011, 29, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagni, G.; Kaigler, D.; Rasperini, G.; Avila-Ortiz, G.; Bartel, R.; Giannobile, W.V. Bone Repair Cells for Craniofacial Regeneration. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 1310–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Dziak, R.; Mao, K.; Genco, R.; Swihart, M.; Li, C.; Yang, S. Integration of a Novel Injectable Nano Calcium Sulfate/Alginate Scaffold and BMP2 Gene-Modified Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Bone Regeneration. Tissue Eng. Part A 2013, 19, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo-Amaral, C.E.; Kobayashi, G.S.; Almeida, A.B.; Bueno, D.F.; de Souza e Freitas, F.R.; Vulcano, L.C.; Passos-Bueno, M.R.; Alonso, N. Alveolar Osseous Defect in Rat for Cell Therapy: Preliminary Report. Acta Cir. Bras. 2010, 25, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, M.; Tanimoto, K.; Tanne, Y.; Sumi, K.; Awada, T.; Oki, N.; Sugiyama, M.; Kato, Y.; Tanne, K. Bone Regeneration in Artificial Jaw Cleft by Use of Carbonated Hydroxyapatite Particles and Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Iliac Bone. Int. J. Dent. 2012, 2012, 352510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, M.A.; Reynolds, K.; Zhou, C.J. Environmental Mechanisms of Orofacial Clefts. Birth Defects Res. 2020, 112, 1660–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzolari, E.; Bianchi, F.; Rubini, M.; Ritvanen, A.; Neville, A.J. Epidemiology of Cleft Palate in Europe: Implications for Genetic Research. Cleft Palate-Craniofac. J. 2004, 41, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taib, B.G.; Taib, A.G.; Swift, A.C.; van Eeden, S. Cleft Lip and Palate: Diagnosis and Management. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2015, 76, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stal, S.; Chebret, L.; McElroy, C. The Team Approach in the Management of Congenital and Acquired Deformities. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1998, 25, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, I.N. Overview of Care in Cleft Lip and Palate for Orthodontic Treatment. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Graber, L.; Vanarsdall, R.L.; Vig, K.W.L. Orthodontics Current Principles & Techniques, 4th ed.; Elsevier Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rawashdeh, M.A.; Telfah, H. Secondary Alveolar Bone Grafting: The Dilemma of Donor Site Selection and Morbidity. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 46, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco, I.; Fernandes, M.H.; Vale, F. Platelet-Rich Fibrin in Bone Regenerative Strategies in Orthodontics: A Systematic Review. Materials 2020, 13, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, V.; Cassoni, A.; Marianetti, T.M.; Romano, F.; Terenzi, V.; Iannetti, G. Reconstruction of Craniofacial Bony Defects Using Autogenous Bone Grafts: A Retrospective Study on 233 Patients. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2007, 18, 953–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, G.; Lee, J.-S.; Yun, W.-S.; Shim, J.-H.; Lee, U.-L. Cleft Alveolus Reconstruction Using a Three-Dimensional Printed Bioresorbable Scaffold with Human Bone Marrow Cells. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2018, 29, 1880–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradel, W.; Lauer, G. Tissue-Engineered Bone Grafts for Osteoplasty in Patients with Cleft Alveolus. Ann. Anat.-Anat. Anz. 2012, 194, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luaces-Rey, R.; Arenaz-Bua, J.; Lopez-Cedrun-Cembranos, J.; Herrero-Patino, S.; Sironvalle-Soliva, S.; Iglesias-Candal, E.; Pombo-Castro, M. Is PRP Useful in Alveolar Cleft Reconstruction? Platelet-Rich Plasma in Secondary Alveoloplasty. Med. Oral 2010, 15, e619–e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morad, G.; Kheiri, L.; Khojasteh, A. Dental Pulp Stem Cells for in Vivo Bone Regeneration: A Systematic Review of Literature. Arch. Oral Biol. 2013, 58, 1818–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumarán, C.; Parra, M.; Olate, S.; Fernández, E.; Muñoz, F.; Haidar, Z. The 3 R’s for Platelet-Rich Fibrin: A “Super” Tri-Dimensional Biomaterial for Contemporary Naturally-Guided Oro-Maxillo-Facial Soft and Hard Tissue Repair, Reconstruction and Regeneration. Materials 2018, 11, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, M.; Zotti, F.; Lanaro, L.; Trojan, D.; Paolin, A.; Montagner, G.; Iannielli, A.; Rodella, L.F.; Nocini, P.F. Fresh-Frozen Homologous Bone in Sinus Lifting: Histological and Radiological Analysis. Minerva Stomatol. 2019, 68, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisci, G.; Fredianelli, L. Therapeutic Efficacy of Bromelain in Alveolar Ridge Preservation. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Pan, W.; Feng, C.; Su, Z.; Duan, Z.; Zheng, Q.; Hua, C.; Li, C. Grafting Materials for Alveolar Cleft Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Best-Evidence Synthesis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 47, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco, I.; Paula, A.B.; Oliveiros, B.; Fernandes, M.H.; Carrilho, E.; Marto, C.M.; Vale, F. Regenerative Strategies in Cleft Palate: An Umbrella Review. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrivikraman, G.; Athirasala, A.; Twohig, C.; Boda, S.K.; Bertassoni, L.E. Biomaterials for Craniofacial Bone Regeneration. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 61, 835–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, G.; Johnson, B.N.; Jia, X. Three-Dimensional (3D) Printed Scaffold and Material Selection for Bone Repair. Acta Biomater. 2019, 84, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, H.; Rieder, W.; Irsen, S.; Leukers, B.; Tille, C. Three-Dimensional Printing of Porous Ceramic Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2005, 74B, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggion, C.M. Guidelines for Reporting Pre-Clinical In Vitro Studies on Dental Materials. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2012, 12, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinand, C.; Pomerantseva, I.; Neville, C.M.; Gupta, R.; Weinberg, E.; Madisch, I.; Shapiro, F.; Abukawa, H.; Troulis, M.J.; Vacanti, J.P. Hydrogel-β-TCP Scaffolds and Stem Cells for Tissue Engineering Bone. Bone 2006, 38, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Shim, J.-H.; Choi, S.-A.; Jang, J.; Kim, M.; Lee, S.H.; Cho, D.-W. 3D Printing Technology to Control BMP-2 and VEGF Delivery Spatially and Temporally to Promote Large-Volume Bone Regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 5415–5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; He, P.; Liu, F.; Li, L.; Zhang, H.; Ji, P.; Yang, S. Nanotube-Decorated Hierarchical Tantalum Scaffold Promoted Early Osseointegration. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2021, 35, 102390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alksne, M.; Kalvaityte, M.; Simoliunas, E.; Rinkunaite, I.; Gendviliene, I.; Locs, J.; Rutkunas, V.; Bukelskiene, V. In Vitro Comparison of 3D Printed Polylactic Acid/Hydroxyapatite and Polylactic Acid/Bioglass Composite Scaffolds: Insights into Materials for Bone Regeneration. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 104, 103641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, E.-B.; Park, K.-H.; Shim, J.-H.; Chung, H.-Y.; Choi, J.-W.; Lee, J.-J.; Kim, C.-H.; Jeon, H.-J.; Kang, S.-S.; Huh, J.-B. Efficacy of RhBMP-2 Loaded PCL/β -TCP/BdECM Scaffold Fabricated by 3D Printing Technology on Bone Regeneration. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 2876135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Xiao, L.; Cao, Y.; Nanda, A.; Xu, C.; Ye, Q. 3D Printed β-TCP Scaffold with Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Coating Promotes Osteogenesis and Inhibits Inflammation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 512, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-W.; Shen, Y.-F.; Ho, C.-C.; Yu, J.; Wu, Y.-H.A.; Wang, K.; Shih, C.-T.; Shie, M.-Y. Osteogenic and Angiogenic Potentials of the Cell-Laden Hydrogel/Mussel-Inspired Calcium Silicate Complex Hierarchical Porous Scaffold Fabricated by 3D Bioprinting. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 91, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-C.; Shie, M.-Y.; Lin, Y.-H.; Lee, A.K.-X.; Chen, Y.-W. Effect of Strontium Substitution on the Physicochemical Properties and Bone Regeneration Potential of 3D Printed Calcium Silicate Scaffolds. IJMS 2019, 20, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, M.E.; Ramirez-GarciaLuna, J.L.; Rangel-Berridi, K.; Park, H.; Nazhat, S.N.; Weber, M.H.; Henderson, J.E.; Rosenzweig, D.H. 3D Printed Polyurethane Scaffolds for the Repair of Bone Defects. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 557215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Li, Q.; Gao, H.; Yao, L.; Lin, Z.; Li, D.; Zhu, S.; Liu, C.; Yang, Z.; Wang, G.; et al. 3D Printing of Cu-Doped Bioactive Glass Composite Scaffolds Promotes Bone Regeneration through Activating the HIF-1α and TNF-α Pathway of HUVECs. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 5519–5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, N.; Ferreira, J.A.; Malda, J.; Bhaduri, S.B.; Bottino, M.C. Extracellular Matrix/Amorphous Magnesium Phosphate Bioink for 3D Bioprinting of Craniomaxillofacial Bone Tissue. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 23752–23763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimipour, F.; Dashtimoghadam, E.; Mahdi Hasani-Sadrabadi, M.; Vargas, J.; Vashaee, D.; Lobner, D.C.; Jafarzadeh Kashi, T.S.; Ghasemzadeh, B.; Tayebi, L. Enhancing Cell Seeding and Osteogenesis of MSCs on 3D Printed Scaffolds through Injectable BMP2 Immobilized ECM-Mimetic Gel. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 990–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Cerezo, M.N.; Lozano, D.; Arcos, D.; Vallet-Regí, M.; Vaquette, C. The Effect of Biomimetic Mineralization of 3D-Printed Mesoporous Bioglass Scaffolds on Physical Properties and in Vitro Osteogenicity. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 109, 110572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Guo, Y.; Jia, L.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, L.; Yang, Z.; Dai, Y.; Lou, Z.; Xia, Y. 3D Magnetic Nanocomposite Scaffolds Enhanced the Osteogenic Capacities of Rat Bone Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Vitro and in a Rat Calvarial Bone Defect Model by Promoting Cell Adhesion. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2021, 109, 1670–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-H.; Wang, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-Y.; Hsu, T.-T.; Lin, C.-P. Incorporation of Calcium Sulfate Dihydrate into a Mesoporous Calcium Silicate/Poly-ε-Caprolactone Scaffold to Regulate the Release of Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 and Accelerate Bone Regeneration. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.E.; Park, S.Y.; Shin, J.Y.; Seok, J.M.; Byun, J.H.; Oh, S.H.; Kim, W.D.; Lee, J.H.; Park, W.H.; Park, S.A. 3D Printing of Bone-Mimetic Scaffold Composed of Gelatin/Β-Tri-Calcium Phosphate for Bone Tissue Engineering. Macromol. Biosci. 2020, 20, 2000256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, C.-T.; Lin, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-W.; Yeh, C.-H.; Fang, H.-Y.; Shie, M.-Y. Poly(Dopamine) Coating of 3D Printed Poly(Lactic Acid) Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 56, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, D.; Tarafder, S.; Vahabzadeh, S.; Bose, S. Effects of MgO, ZnO, SrO, and SiO2 in Tricalcium Phosphate Scaffolds on in Vitro Gene Expression and in Vivo Osteogenesis. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 96, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.-S.; Yang, S.-S.; Kim, C.S. Incorporation of BMP-2 Nanoparticles on the Surface of a 3D-Printed Hydroxyapatite Scaffold Using an ε-Polycaprolactone Polymer Emulsion Coating Method for Bone Tissue Engineering. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 170, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.A.; Yun, H.; Choi, Y.-A.; Kim, J.-E.; Choi, S.-Y.; Kwon, T.-G.; Kim, Y.K.; Kwon, T.-Y.; Bae, M.A.; Kim, N.J.; et al. Magnesium Phosphate Ceramics Incorporating a Novel Indene Compound Promote Osteoblast Differentiation in Vitro and Bone Regeneration in Vivo. Biomaterials 2018, 157, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; Won, J.-E.; Han, C.; Yin, X.Y.; Kim, H.K.; Nah, H.; Kwon, I.K.; Min, B.-H.; Kim, C.-H.; Shin, Y.S.; et al. Development of a Three-Dimensionally Printed Scaffold Grafted with Bone Forming Peptide-1 for Enhanced Bone Regeneration with in Vitro and in Vivo Evaluations. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 539, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, M.; Wei, X.; Hao, Y.; Wang, J. Evaluation of 3D-Printed Polycaprolactone Scaffolds Coated with Freeze-Dried Platelet-Rich Plasma for Bone Regeneration. Materials 2017, 10, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, H.; Xu, X.; Fu, X.; Pan, J.; Wang, H.; Fuh, J.Y.H.; Bai, Y.; Wei, S. An Effective Dual-factor Modified 3D-printed PCL Scaffold for Bone Defect Repair. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2020, 108, 2167–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Umebayashi, M.; Abdallah, M.-N.; Dong, G.; Roskies, M.G.; Zhao, Y.F.; Murshed, M.; Zhang, Z.; Tran, S.D. Combination of Polyetherketoneketone Scaffold and Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Temporomandibular Joint Synovial Fluid Enhances Bone Regeneration. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Chiu, Y.-C.; Shen, Y.-F.; Wu, Y.-H.A.; Shie, M.-Y. Bioactive Calcium Silicate/Poly-ε-Caprolactone Composite Scaffolds 3D Printed under Mild Conditions for Bone Tissue Engineering. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2018, 29, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Chuang, T.-Y.; Chiang, W.-H.; Chen, I.-W.P.; Wang, K.; Shie, M.-Y.; Chen, Y.-W. The Synergistic Effects of Graphene-Contained 3D-Printed Calcium Silicate/Poly-ε-Caprolactone Scaffolds Promote FGFR-Induced Osteogenic/Angiogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 104, 109887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, V.; Ribeiro, I.A.; Alves, M.M.; Gonçalves, L.; Claudio, R.A.; Grenho, L.; Fernandes, M.H.; Gomes, P.; Santos, C.F.; Bettencourt, A.F. Engineering a Multifunctional 3D-Printed PLA-Collagen-Minocycline-NanoHydroxyapatite Scaffold with Combined Antimicrobial and Osteogenic Effects for Bone Regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 101, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, X.; Su, Z.; Fu, Y.; Li, S.; Mo, A. 3D Printing of Ti3C2-MXene-Incorporated Composite Scaffolds for Accelerated Bone Regeneration. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 17, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, Q.; Hao, L.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y. Engineering Natural Matrices with Black Phosphorus Nanosheets to Generate Multi-Functional Therapeutic Nanocomposite Hydrogels. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 4046–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midha, S.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, A.; Kaur, K.; Shi, X.; Naruphontjirakul, P.; Jones, J.R.; Ghosh, S. Silk Fibroin-Bioactive Glass Based Advanced Biomaterials: Towards Patient-Specific Bone Grafts. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 13, 055012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.; Song, W.; Xin, H.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.; Ma, D.; Cao, X.; Wang, Y. MicroRNA-Activated Hydrogel Scaffold Generated by 3D Printing Accelerates Bone Regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.A.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, K.; Jo, D.; Park, S. Three-dimensionally Printed Polycaprolactone/Beta-tricalcium Phosphate Scaffold Was More Effective as an rhBMP-2 Carrier for New Bone Formation than Polycaprolactone Alone. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2021, 109, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratheesh, G.; Shi, M.; Lau, P.; Xiao, Y.; Vaquette, C. Effect of Dual Pore Size Architecture on In Vitro Osteogenic Differentiation in Additively Manufactured Hierarchical Scaffolds. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 2615–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remy, M.T.; Akkouch, A.; He, L.; Eliason, S.; Sweat, M.E.; Krongbaramee, T.; Fei, F.; Qian, F.; Amendt, B.A.; Song, X.; et al. Rat Calvarial Bone Regeneration by 3D-Printed β-Tricalcium Phosphate Incorporating MicroRNA-200c. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 4521–4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, H.-S.; Lee, C.-M.; Hwang, Y.-H.; Kook, M.-S.; Yang, S.-W.; Lee, D.; Kim, B.-H. Addition of MgO Nanoparticles and Plasma Surface Treatment of Three-Dimensional Printed Polycaprolactone/Hydroxyapatite Scaffolds for Improving Bone Regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 74, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.-H.; Won, J.-Y.; Park, J.-H.; Bae, J.-H.; Ahn, G.; Kim, C.-H.; Lim, D.-H.; Cho, D.-W.; Yun, W.-S.; Bae, E.-B.; et al. Effects of 3D-Printed Polycaprolactone/β-Tricalcium Phosphate Membranes on Guided Bone Regeneration. IJMS 2017, 18, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, C.; Yang, W.; Feng, P.; Peng, S.; Pan, H. Accelerated Degradation of HAP/PLLA Bone Scaffold by PGA Blending Facilitates Bioactivity and Osteoconductivity. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tcacencu, I.; Rodrigues, N.; Alharbi, N.; Benning, M.; Toumpaniari, S.; Mancuso, E.; Marshall, M.; Bretcanu, O.; Birch, M.; McCaskie, A.; et al. Osseointegration of Porous Apatite-Wollastonite and Poly(Lactic Acid) Composite Structures Created Using 3D Printing Techniques. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 90, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-H.; Hung, C.-H.; Kuo, C.-N.; Chen, C.-Y.; Peng, Y.-N.; Shie, M.-Y. Improved Bioactivity of 3D Printed Porous Titanium Alloy Scaffold with Chitosan/Magnesium-Calcium Silicate Composite for Orthopaedic Applications. Materials 2019, 12, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeyama, R.; Yamawaki, T.; Liu, D.; Kanazawa, S.; Takato, T.; Hoshi, K.; Hikita, A. Optimization of Culture Duration of Bone Marrow Cells before Transplantation with a β-Tricalcium Phosphate/Recombinant Collagen Peptide Hybrid Scaffold. Regen. Ther. 2020, 14, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Yin, H.-M.; Li, X.; Liu, W.; Chu, Y.-X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.-Z.; Li, Z.-M.; Li, J.-H. Simultaneously Constructing Nanotopographical and Chemical Cues in 3D-Printed Polylactic Acid Scaffolds to Promote Bone Regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 118, 111457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Li, R.; Xu, Y.; Xia, D.; Zhu, Y.; Yoon, J.; Gu, R.; Liu, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, X.; et al. Fabrication and Application of a 3D-Printed Poly-ε-Caprolactone Cage Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-H.; Chiu, Y.-C.; Lin, Y.-H.; Ho, C.-C.; Shie, M.-Y.; Chen, Y.-W. 3D-Printed Bioactive Calcium Silicate/Poly-ε-Caprolactone Bioscaffolds Modified with Biomimetic Extracellular Matrices for Bone Regeneration. IJMS 2019, 20, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, D.; Qin, Y.; Guo, H.; Wen, P.; Lin, H.; Voshage, M.; Schleifenbaum, J.H.; Cheng, Y.; Zheng, Y. Additively Manufactured Pure Zinc Porous Scaffolds for Critical-Sized Bone Defects of Rabbit Femur. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 19, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, N.; Liu, P.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fei, F.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, J.; Han, B. Poly(Dopamine) Coating on 3D-Printed Poly-Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid/β-Tricalcium Phosphate Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Molecules 2019, 24, 4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, N.; Ma, Y.; Dai, H.; Han, B. Preparation and Study of 3D Printed Dipyridamole/β-Tricalcium Phosphate/ Polyvinyl Alcohol Composite Scaffolds in Bone Tissue Engineering. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 68, 103053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Choi, D.; Choi, D.-J.; Jin, S.; Yun, W.-S.; Huh, J.-B.; Shim, J.-H. Bone Fracture-Treatment Method: Fixing 3D-Printed Polycaprolactone Scaffolds with Hydrogel Type Bone-Derived Extracellular Matrix and β-Tricalcium Phosphate as an Osteogenic Promoter. IJMS 2021, 22, 9084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamani, Y.; Amoabediny, G.; Mohammadi, J.; Zandieh-Doulabi, B.; Klein-Nulend, J.; Helder, M.N. Increased Osteogenic Potential of Pre-Osteoblasts on Three-Dimensional Printed Scaffolds Compared to Porous Scaffolds for Bone Regeneration. Iran. Biomed. J. 2021, 25, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Fu, L.; Ye, S.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Y. Fabrication and Application of Novel Porous Scaffold in Situ-Loaded Graphene Oxide and Osteogenic Peptide by Cryogenic 3D Printing for Repairing Critical-Sized Bone Defect. Molecules 2019, 24, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Wang, Y.; Qin, L.; Guo, Z.; Li, D. Effect of Composition and Macropore Percentage on Mechanical and in Vitro Cell Proliferation and Differentiation Properties of 3D Printed HA/β-TCP Scaffolds. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 43186–43196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Chen, J.; Ma, Z.; Feng, H.; Chen, S.; Cai, H.; Xue, Y.; Pei, X.; Wang, J.; Wan, Q. 3D Printing of Metal–Organic Framework Incorporated Porous Scaffolds to Promote Osteogenic Differentiation and Bone Regeneration. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 24437–24449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hout, W.M.M.T.; Mink van der Molen, A.B.; Breugem, C.C.; Koole, R.; Van Cann, E.M. Reconstruction of the Alveolar Cleft: Can Growth Factor-Aided Tissue Engineering Replace Autologous Bone Grafting? A Literature Review and Systematic Review of Results Obtained with Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2011, 15, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojasteh, A.; Kheiri, L.; Motamedian, S.R.; Nadjmi, N. Regenerative Medicine in the Treatment of Alveolar Cleft Defect: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 1608–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, M.; Ziyab, A.H.; Bartella, A.; Mitchell, D.; Al-Asfour, A.; Hölzle, F.; Kessler, P.; Lethaus, B. Volumetric Comparison of Autogenous Bone and Tissue-Engineered Bone Replacement Materials in Alveolar Cleft Repair: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 56, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, S.; Sarkar, N.; Banerjee, D. Effects of PCL, PEG and PLGA Polymers on Curcumin Release from Calcium Phosphate Matrix for in Vitro and in Vivo Bone Regeneration. Mater. Today Chem. 2018, 8, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Park, T.H.; Ryu, J.Y.; Kim, D.K.; Oh, E.J.; Kim, H.M.; Shim, J.-H.; Yun, W.-S.; Huh, J.B.; Moon, S.H.; et al. Osteogenesis of 3D-Printed PCL/TCP/BdECM Scaffold Using Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Aggregates; An Experimental Study in the Canine Mandible. IJMS 2021, 22, 5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-H.; Lee, K.-G.; Hwang, J.-H.; Cho, Y.S.; Lee, K.-S.; Jeong, H.-J.; Park, S.-H.; Park, Y.; Cho, Y.-S.; Lee, B.-K. Evaluation of Mechanical Strength and Bone Regeneration Ability of 3D Printed Kagome-Structure Scaffold Using Rabbit Calvarial Defect Model. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 98, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishack, S.; Mediero, A.; Wilder, T.; Ricci, J.L.; Cronstein, B.N. Bone Regeneration in Critical Bone Defects Using Three-Dimensionally Printed β-Tricalcium Phosphate/Hydroxyapatite Scaffolds Is Enhanced by Coating Scaffolds with Either Dipyridamole or BMP-2: AGENTS THAT STIMULATE A2A RECEPTORS FURTHER ENHANCE HA/Β-TCP SCAFFOLDS BONE REGENERATION. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2017, 105, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Heo, S.; Lee, M.; Lee, H. Evaluation of a Poly(Lactic-Acid) Scaffold Filled with Poly(Lactide-Co-Glycolide)/Hydroxyapatite Nanofibres for Reconstruction of a Segmental Bone Defect in a Canine Model. Vet. Med. 2019, 64, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Guéhennec, L.; Van Hede, D.; Plougonven, E.; Nolens, G.; Verlée, B.; De Pauw, M.; Lambert, F. In Vitro and in Vivo Biocompatibility of Calcium-phosphate Scaffolds Three-dimensional Printed by Stereolithography for Bone Regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2020, 108, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.-I.; Yang, B.-E.; Yi, S.-M.; Choi, H.-G.; On, S.-W.; Hong, S.-J.; Lim, H.-K.; Byun, S.-H. Bone Regeneration of a 3D-Printed Alloplastic and Particulate Xenogenic Graft with RhBMP-2. IJMS 2021, 22, 12518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.-Y.; Park, C.-Y.; Bae, J.-H.; Ahn, G.; Kim, C.; Lim, D.-H.; Cho, D.-W.; Yun, W.-S.; Shim, J.-H.; Huh, J.-B. Evaluation of 3D Printed PCL/PLGA/ β -TCP versus Collagen Membranes for Guided Bone Regeneration in a Beagle Implant Model. Biomed. Mater. 2016, 11, 055013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekisz, J.M.; Flores, R.L.; Witek, L.; Lopez, C.D.; Runyan, C.M.; Torroni, A.; Cronstein, B.N.; Coelho, P.G. Dipyridamole Enhances Osteogenesis of Three-Dimensionally Printed Bioactive Ceramic Scaffolds in Calvarial Defects. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 46, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.-C.; Lin, Z.-J.; Luo, H.-T.; Tu, C.-C.; Tai, W.-C.; Chang, C.-H.; Chang, Y.-C. Degradable RGD-Functionalized 3D-Printed Scaffold Promotes Osteogenesis. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.-C.; Chiu, H.-C.; Kuo, P.-J.; Chiang, C.-Y.; Fu, M.M.; Fu, E. Bone Formation with Functionalized 3D Printed Poly-ε-Caprolactone Scaffold with Plasma-Rich-Fibrin Implanted in Critical-Sized Calvaria Defect of Rat. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 16, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diomede, F.; Gugliandolo, A.; Cardelli, P.; Merciaro, I.; Ettorre, V.; Traini, T.; Bedini, R.; Scionti, D.; Bramanti, A.; Nanci, A.; et al. Three-Dimensional Printed PLA Scaffold and Human Gingival Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: A New Tool for Bone Defect Repair. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Habashy, S.E.; El-Kamel, A.H.; Essawy, M.M.; Abdelfattah, E.-Z.A.; Eltaher, H.M. Engineering 3D-Printed Core–Shell Hydrogel Scaffolds Reinforced with Hybrid Hydroxyapatite/Polycaprolactone Nanoparticles for in Vivo Bone Regeneration. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 4019–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fama, C.; Kaye, G.J.; Flores, R.; Lopez, C.D.; Bekisz, J.M.; Torroni, A.; Tovar, N.; Coelho, P.G.; Witek, L. Three-Dimensionally-Printed Bioactive Ceramic Scaffolds: Construct Effects on Bone Regeneration. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2021, 32, 1177–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Hou, Y.; Zhu, C.; He, M.; Jiang, Y.; Feng, G.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, L. 3D-Printing Biodegradable PU/PAAM/Gel Hydrogel Scaffold with High Flexibility and Self-Adaptibility to Irregular Defects for Nonload-Bearing Bone Regeneration. Bioconjug. Chem. 2021, 32, 1915–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Yang, Z.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Dai, Y.; Xia, Y. A Three-Dimensional-Printed SPION/PLGA Scaffold for Enhanced Palate-Bone Regeneration and Concurrent Alteration of the Oral Microbiota in Rats. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 126, 112173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Z.M.; Yuan, Y.; Li, X.; Jashashvili, T.; Jamieson, M.; Urata, M.; Chen, Y.; Chai, Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Three-Dimensional-Osteoconductive Scaffold Regenerate Calvarial Bone in Critical Size Defects in Swine. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2021, 10, 1170–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-W.; Yang, B.-E.; Hong, S.-J.; Choi, H.-G.; Byeon, S.-J.; Lim, H.-K.; Chung, S.-M.; Lee, J.-H.; Byun, S.-H. Bone Regeneration Capability of 3D Printed Ceramic Scaffolds. IJMS 2020, 21, 4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.; Kwon, J.; Kim, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, T.; Lee, Y.; Kim, S.; Miguez, P.; Ko, C. Effect of Pore Size in Bone Regeneration Using Polydopamine-laced Hydroxyapatite Collagen Calcium Silicate Scaffolds Fabricated by 3D Mould Printing Technology. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2019, 22, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, T.; Wu, J.; Li, F.; Huang, Z.; Pi, Y.; Miao, G.; Ren, W.; Liu, T.; Jiang, Q.; Guo, L. Drug-loading Three-dimensional Scaffolds Based on Hydroxyapatite-sodium Alginate for Bone Regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2021, 109, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.-K.; Hong, S.-J.; Byeon, S.-J.; Chung, S.-M.; On, S.-W.; Yang, B.-E.; Lee, J.-H.; Byun, S.-H. 3D-Printed Ceramic Bone Scaffolds with Variable Pore Architectures. IJMS 2020, 21, 6942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Sun, M.; Yang, X.; Ma, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Yan, S.; Gou, Z. Three-Dimensional Printing Akermanite Porous Scaffolds for Load-Bearing Bone Defect Repair: An Investigation of Osteogenic Capability and Mechanical Evolution. J. Biomater. Appl. 2016, 31, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.D.; Diaz-Siso, J.R.; Witek, L.; Bekisz, J.M.; Gil, L.F.; Cronstein, B.N.; Flores, R.L.; Torroni, A.; Rodriguez, E.D.; Coelho, P.G. Dipyridamole Augments Three-Dimensionally Printed Bioactive Ceramic Scaffolds to Regenerate Craniofacial Bone: Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 143, 1408–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naudot, M.; Garcia Garcia, A.; Jankovsky, N.; Barre, A.; Zabijak, L.; Azdad, S.Z.; Collet, L.; Bedoui, F.; Hébraud, A.; Schlatter, G.; et al. The Combination of a Poly-caprolactone/Nano-hydroxyapatite Honeycomb Scaffold and Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promotes Bone Regeneration in Rat Calvarial Defects. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2020, 14, 1570–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pae, H.; Kang, J.; Cha, J.; Lee, J.; Paik, J.; Jung, U.; Kim, B.; Choi, S. 3D-printed Polycaprolactone Scaffold Mixed with Β-tricalcium Phosphate as a Bone Regenerative Material in Rabbit Calvarial Defects. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2019, 107, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Wu, D.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhan, F.; Lai, H.; Gu, Y. The Combination of Multi-Functional Ingredients-Loaded Hydrogels and Three-Dimensional Printed Porous Titanium Alloys for Infective Bone Defect Treatment. J. Tissue Eng. 2020, 11, 204173142096579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Wei, Y.; Han, J.; Jiang, X.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Gou, Z.; Chen, L. 3D Printed Bioceramic Scaffolds: Adjusting Pore Dimension Is Beneficial for Mandibular Bone Defects Repair. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2022, 16, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Liu, A.; Guo, H.; Shen, Y.; Wen, P.; Lin, H.; Xia, D.; Voshage, M.; Tian, Y.; Zheng, Y. Additive Manufacturing of Zn-Mg Alloy Porous Scaffolds with Enhanced Osseointegration: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Acta Biomater. 2022, 145, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowska-Tylman, J.; Locs, J.; Salma, I.; Woźniak, B.; Pilmane, M.; Zalite, V.; Wojnarowicz, J.; Kędzierska-Sar, A.; Chudoba, T.; Szlązak, K.; et al. In Vivo and in Vitro Study of a Novel Nanohydroxyapatite Sonocoated Scaffolds for Enhanced Bone Regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 99, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, Y.-W.; Park, J.-Y.; Lee, D.-N.; Jin, X.; Cha, J.-K.; Paik, J.-W.; Choi, S.-H. Three-Dimensionally Printed Biphasic Calcium Phosphate Blocks with Different Pore Diameters for Regeneration in Rabbit Calvarial Defects. Biomater. Res. 2022, 26, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, J.-H.; Jeong, J.; Won, J.-Y.; Bae, J.-H.; Ahn, G.; Jeon, H.; Yun, W.-S.; Bae, E.-B.; Choi, J.-W.; Lee, S.-H.; et al. Porosity Effect of 3D-Printed Polycaprolactone Membranes on Calvarial Defect Model for Guided Bone Regeneration. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 13, 015014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tovar, N.; Witek, L.; Atria, P.; Sobieraj, M.; Bowers, M.; Lopez, C.D.; Cronstein, B.N.; Coelho, P.G. Form and Functional Repair of Long Bone Using 3D-printed Bioactive Scaffolds. J. Tissue Eng Regen. Med. 2018, 12, 1986–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulyaganov, D.U.; Fiume, E.; Akbarov, A.; Ziyadullaeva, N.; Murtazaev, S.; Rahdar, A.; Massera, J.; Verné, E.; Baino, F. In Vivo Evaluation of 3D-Printed Silica-Based Bioactive Glass Scaffolds for Bone Regeneration. JFB 2022, 13, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, L.M.; de Souza Balbinot, G.; Brotto, G.L.; Leitune, V.C.B.; Soares, R.M.D.; Collares, F.M.; Ponzoni, D. 3D Printing of Poly(Butylene Adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT)/Niobium Containing Bioactive Glasses (BAGNb) Scaffolds: Characterization of Composites, in Vitro Bioactivity, and in Vivo Bone Repair. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2022, 16, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hede, D.; Liang, B.; Anania, S.; Barzegari, M.; Verlée, B.; Nolens, G.; Pirson, J.; Geris, L.; Lambert, F. 3D-Printed Synthetic Hydroxyapatite Scaffold With In Silico Optimized Macrostructure Enhances Bone Formation In Vivo. Adv. Funct Materials 2022, 32, 2105002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.M.; Flores, R.L.; Witek, L.; Torroni, A.; Ibrahim, A.; Wang, Z.; Liss, H.A.; Cronstein, B.N.; Lopez, C.D.; Maliha, S.G.; et al. Dipyridamole-Loaded 3D-Printed Bioceramic Scaffolds Stimulate Pediatric Bone Regeneration in Vivo without Disruption of Craniofacial Growth through Facial Maturity. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Bai, X.; Fei, Q.; Zhang, L. Rapid Human-derived IPSC Osteogenesis Combined with Three-dimensionally Printed Ti6Al4V Scaffolds for the Repair of Bone Defects. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 9763–9772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Feng, C.; Yang, G.; Li, G.; Ding, X.; Wang, S.; Dou, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chang, J.; Wu, C.; et al. 3D-Printed Scaffolds with Synergistic Effect of Hollow-Pipe Structure and Bioactive Ions for Vascularized Bone Regeneration. Biomaterials 2017, 135, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekisz, J.M.; Fryml, E.; Flores, R.L. A Review of Randomized Controlled Trials in Cleft and Craniofacial Surgery. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2018, 29, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghayor, C.; Chen, T.-H.; Bhattacharya, I.; Özcan, M.; Weber, F.E. Microporosities in 3D-Printed Tricalcium-Phosphate-Based Bone Substitutes Enhance Osteoconduction and Affect Osteoclastic Resorption. IJMS 2020, 21, 9270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).