Why Critical Thinking Can and Often Does Fail Us in Solving Serious Real-World Problems: A Three-Track Model of Critical Thinking

Abstract

1. Introduction

What Is Critical Thinking?

2. Assumptions Underlying the Present Analysis

- The operations of critical thinking and analytical intelligence can be understood only in light of the tasks people need to solve and the environmental contexts in which they need to solve them (Sternberg 2021a, 2025a). Critical thinking occurs as a person x task x environmental context interaction. How intelligently people operate depends greatly on task: If your adaptation and life depended on your ability to hunt wild animals and forage for edible plants, how well would you do? And how intelligently people operate also depends on the environmental context: Your ability to hunt a wild animal might depend on whether the animal was fearfully running away from you or menacingly running toward you. But the importance of task and situation is not limited to hunting/gathering cultures. In life-threatening situations—such as natural disasters or human-created disasters such as war—whether one can rise to using one’s intelligence and critical thinking maximally under stress becomes a matter of life or death.

- Real-world problems are qualitatively different from test problems. The real tasks and problems we face in life look little like the problems we face on standardized tests. In particular, real problems:

- are for high and sometimes life-changing (or, in extreme cases, potentially life-ending) stakes,

- are emotionally complex and arousing, sometimes to the level that emotions cloud or utterly befuddle people’s better judgment, leading people to think in suboptimal ways,

- are highly driven by environmental context, requiring people to balance many conflicting interests, and sometimes forcing people to decide whether they will respond in suboptimal ways because their fellow humans want suboptimal solutions,

- do not typically have a single “correct” answer, but rather multiple answers, each of which is better in some ways and worse in other ways,

- are lacking a third party to tell us that we even have a problem in need of solution,

- often are unclear in their parameters, so that it is not certain what the problem is,

- are often in need of a collective solution, usually by people with different backgrounds, interests, and stakes in the solution,

- typically provide, at best, only vague paths to a solution, or seemingly no good paths at all, so that we have to create our own new path,

- often unfold over long periods of time, and sometimes, change as we are in the midst of solving them so that the course we have taken stops working, even if it worked before,

- often make it hard to figure out what information is needed for problem solution or where that needed information is to be located,

- are often riddled with numerous and diverse bits of false or misleading information, with the information deliberately inserted to lead the problem solver down a garden path (Sternberg 2025a).

- The rewarded solution to a problem often is not the best answer in any objective sense, but rather, the solution that those in power want to reach, even if it is wrong, pernicious, immoral, or the product of corrupted thinking. We live in a time when authorities are often driven by the demand for more power, more financial or other resources, more fame, or more revenge against those they view as having betrayed them. Human nature being what it is, many people succumb to authority, whatever its demands (Milgram 2009; Zimbardo 2008). In a world where there are so many strong and often contrary agendas, the idea that there are real-world problems to be solved that depend just on being given the problem explicitly, with a clear path to solution, and with a single “correct” solution that everyone accepts, seems almost quaint.

3. The Costs and Benefits of Adaptive Behavior—Threats

4. Love and Hatred of Ideas Can Deflect or Even Utterly Decimate Critical Thinking

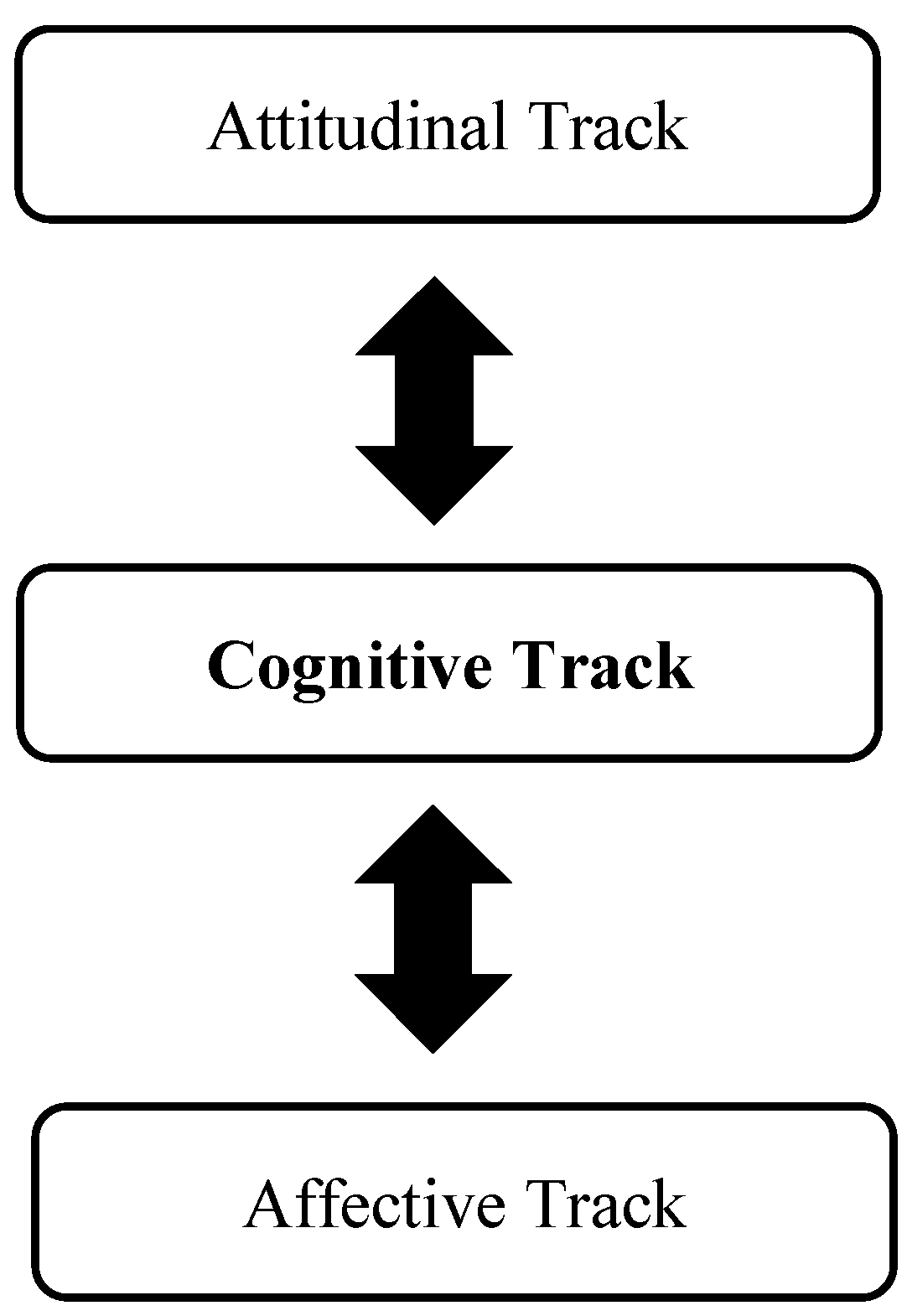

5. A Three-Track Model of Critical Thinking

6. Implications for Education

- Critical thinking does not come naturally. Critical thinking involves complex metacognitive and cognitive processes integrated with attitudinal and affective variables that can facilitate or impede it. Teachers cannot assume that students will just learn how to do it by being in school or by being on their own. Many students graduate from school and are nevertheless deficient critical thinkers.

- Critical thinking taught in the abstract as a set of metacognitive and cognitive processes is inadequate to meeting the demands of the everyday world. As soon as people have a vested interest in an outcome or a feeling of personal or ideological alignment with a certain viewpoint, their critical thinking will begin to be affected by the alignment. Part of instruction needs to be teaching students to be aware of their own biases and counteract them.

- Much of critical thinking is determined, just as the critical thinking gets seriously started, by what problems one recognizes and how one defines those problems. So much of problem solving is a matter of how one defines problems. That is why, say, Vladimir Putin refers to the invasion of Ukraine as a “special military operation” instead of, say, a genocide aimed at wiping out a separate Ukrainian identity. Or why people who view abortion as a matter of “right to life” usually come to conclusions different from those who define abortion as a matter of “women’s choice with their own bodies.”

- People often use their analytical (IQ-based) intelligence not to improve their critical thinking but rather to garner support for their own prior position. High IQ can help critical thinking by improving metacognitive (metacomponential) functioning, but it is at least as likely merely to serve as a means for people to figure out ever more clever reasons to support their own position—much as in debate contests.

- Standardized testing could, but generally does not, help support critical thinking. Students growing up in a testing culture learn, very often, not how to think critically but rather how to provide authorities with the answers that the test-taker thinks the authorities want to hear. Thus, standardized testing may discourage critical thinking in favor of learning how to produce ingratiating responses.

- Critical thinking has both domain-general and domain-specific aspects. Because abilities, attitudes, and affects all influence critical thinking, the quality of critical thinking may vary greatly across domains as a function of one’s interests, ideologies, abilities, and efforts. At the same time, the metacomponential executive processes are largely the same across domains, so there is some domain-generality as well.

- One cannot improve critical thinking if one requires it of others but does not show it oneself. Students and everyone else acquire much of their tacit knowledge base by observational learning (Bandura 1986). Ultimately, as Bandura showed, people will model the behavior they observe far more than they will base their behavior on what they are told.

- Critical thinking is desperately needed in today’s world, but the current emphasis on knowledge acquisition often generates students who lack the critical thinking skills they need to succeed in the world and also to make the world a better place. Teaching for facts may lead to success on achievement tests that superficially measure school achievement, but it will not lead to success when students need to confront real problems in real-world contexts.

- Love can either fuel or detract from critical thinking. As educators, we need to ensure that students are aware of how an emotion such as love can yield critical thinking. Love, especially passionate love of an idea, can lead to great advances in creativity and knowledge. But it also can lead to the same kind of distorted or even obsessive thinking that people in love sometimes feel toward people with whom they fall in love, especially in the early stages of a romantic relationship.

- Recognizing the connection between the affective and attitudinal tracks of critical thinking is imperative to helping students understand that their ideas may not always remain unchanged. Critical thinking is a process that takes time, practice, patience, and care. One’s ideas may take on new meanings and evolve year to year or perhaps even day to day. Teaching students to understand that their critical thinking is impacted by the positive but also the negative effects of the attitudinal and affective tracks may fundamentally reshape their understanding of the idea at hand. This reshaping is not a phenomenon to fear but rather a testament to the continued pursuit of engaging in critical thinking.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albright, Madeline. 2018. Fascism: A Warning. New York: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Aron, Raymond. 2001. The Opium of the Intellectuals. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Balch, Robert W., and David Taylor. 2002. Making Sense of the Heaven’s Gate Suicides. In Cults, Religion, and Violence. Edited by David. G. Bromley and J. Gordon Melton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 209–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert. 1986. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert. 2015. Moral Disengagement: How People Do Harm and Live with Themselves. New York: Worth. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, Jonathan. 2023. Thinking and Deciding, 5th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, Barton J. 1982. In the matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 12: 195–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethe, Hans A. 1968. J. Robert Oppenheimer, 1904–1967. London: Royal Society. [Google Scholar]

- Bratsberg, Bernt, and Ole Rogeberg. 2018. Flynn effect and its reversal are both environmentally caused. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115: 6674–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 2000. Ecological systems theory. In Encyclopedia of Psychology. Edited by Alan E. Kazdin. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 3, pp. 129–33. [Google Scholar]

- Buss, David M. 2016. The Evolution of Desire. rev. and updated. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Richard W., and Andrew Whiten. 1998. Machiavellian Intelligence: Social Expertise and the Evolution of Intellect in Monkeys, Apes, and Humans. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ceci, Stephen J., and Antonio Roazzi. 1994. The effects of context on cognition: Postcards from Brazil. In Mind in Context: Interactionist Perspectives on Human Intelligence. Edited by Robert J. Sternberg and Richard K. Wagner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Colombatto, Enrico. 2024. PISA Results: Poor Education Is No Recipe for Economic Brilliance. GIS Reports Online, February 22. Available online: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/worsening-2022-pisa-tests-results-oecd/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Coppes-Zantinga, Arty R., and Max J. Coppes. 1998. Madame Marie Curie (1867–1934): A giant connecting two centuries. AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology 171: 1453–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douthat, Ross. 2025. Steve Bannon on “Broligarchs” vs. Populism. New York Times, January 31. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/31/opinion/steve-bannon-on-broligarchs-vs-populism.html (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Elder, Linda, and Richard Paul. 2008. Critical thinking in a world of accelerated change and complexity. Social Education 72: 388–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ennis, Robert H. 1987. A taxonomy of critical thinking dispositions and abilities. In Teaching Thinking Skills: Theory and Practice. Edited by Jonathan Baron and Robert J. Sternberg. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman, pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ennis, Robert H. 1991. Critical thinking: A streamlined conception. Teaching Philosophy 14: 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, Robert H. 2011. The Nature of Critical Thinking: An Outline of Critical Thinking Dispositions and Abilities. Available online: https://education.illinois.edu/docs/default-source/faculty-documents/robert-ennis/thenatureofcriticalthinking_51711_000.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Flynn, James R. 1984. The mean IQ of Americans: Massive gains 1932 to 1978. Psychological Bulletin 95: 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, James R. 1987. Massive IQ gains in 14 nations: What IQ tests really measure. Psychological Bulletin 101: 171–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, James R. 2011. Secular changes in intelligence. In The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence. Edited by Robert J. Sternberg and Scott Barry Kaufman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 647–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, James R. 2020. Secular changes in intelligence: The “Flynn effect”. In The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence, 2nd ed. Edited by Robert J. Sternberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 940–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foundation for Critical Thinking. 2009. Defining Critical Thinking. Available online: http://www.criticalthinking.org/aboutCT/define_critical_thinking.cfm (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Free Press Unlimited. 2024. A Rise in Authoritarianism Puts Press Freedom Under Increasing Pressure. May 3. Available online: https://www.freepressunlimited.org/en/current/rise-authoritarianism-puts-press-freedom-under-increasing-pressure (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Gardner, Howard. 2011. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. exp. ed. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Geher, Glenn, Scott B. Kaufman, and Helen Fisher. 2013. Mating Intelligence Unleashed: The Role of the Mind in Sex, Dating, and Love. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gigerenzer, Gerd. 2023. The Intelligence of Intuition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Sydney, and Robert J. Sternberg. 2024. Loving our leaders: A triangular theory of love for political figures. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 54: 683–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, Sydney, and Robert J. Sternberg. 2025. Application of the triangular theory of love to food preferences. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorenko, Elena L., Linda Jarvin, and Robert J. Sternberg. 2002. School–based tests of the triarchic theory of intelligence: Three settings, three samples, three syllabi. Contemporary Educational Psychology 27: 167–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, Igor, Nic M. Weststrate, Monika Ardelt, Justin P. Brienza, Mengxi Dong, Michel Ferrari, Marc A. Fournier, Chao S. Hu, Howard C. Nusbaum, and John Vervaeke. 2020. The science of wisdom in a polarized world: Knowns and unknowns. Psychological Inquiry 31: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyote, Martin J., and Robert J. Sternberg. 1981. A transitive-chain theory of syllogistic reasoning. Cognitive Psychology 13: 461–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, Diane F., and Dana S. Dunn. 2022. Thought and Knowledge: An Introduction to Critical Thinking, 6th ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Aurora J. 2025. An Application of the Triangular Theory of Love to One’s Love of Their Academic Concentration. Master’s thesis, Department of Psychology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund, Jennifer. 2020. Practical intelligence. In Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence, 2nd ed. Edited by Robert J. Sternberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 736–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kihlstrom, John F., and Nancy Cantor. 2020. Social intelligence. In Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence, 2nd ed. Edited by Robert J. Sternberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 756–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kowal, Marta Piotr Sorokowski, Bojana M. Dinić, Katarzyna Pisanski, Biljana Gjoneska, David A. Frederick, Gerit Pfuhl, Taciano L. Milfont, Adam Bode, Leonardo Aguilar, Felipe García, and et al. 2023. Validation of the short version (TLS-15) of the Triangular Love Scale (TLS-45) across 37 languages. Archives of Sexual Behavior 53: 839–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langevin-Joliot, H. 1998. Radium, Marie Curie and modern science. Radiation Research 150: S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfitt, Frank. 2025. Hundreds of Scholars Say U.S. Is Swiftly Heading Toward Authoritarianism. NPR, April 22. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2025/04/22/nx-s1-5340753/trump-democracy-authoritarianism-competive-survey-political-scientist (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Langone, Michael D. (Ed.). 1993. Recovery from Cults: Help for Victims of Psychological and Spiritual Abuse. New York: W W Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, Charles. 2020. The Six Stages of Critical Thinking. September 20. Available online: https://www.charlesleon.uk/blog/the-6-stages-of-critical-thinking2092020 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Lipman-Blumen, Jean. 2006. The Allure of Toxic Leaders: Why We Follow Destructive Bosses and Corrupt Politicians—And How We Can Survive Them. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lipman, Matthew. 1995. Moral education, higher-order thinking and philosophy for children. Early Child Development and Care 107: 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipman, Matthew. 1998. Teaching students to think reasonably: Some findings of the Philosophy for Children Program. The Clearing House 71: 277–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipman, Matthew. 2003. Thinking in Education, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mahony, Dan. 2016. Sidis Archives. Available online: https://www.sidis.net/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. 2008. The Communist Manifesto, 3rd ed.Atlanta: Pathfinder Press. First published 1848. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram, Stanley. 2009. Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View. Harper Perennial Modern Classics. New York: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Geoffrey. 2001. The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of Human Nature. New York: Anchor. [Google Scholar]

- Mounk, Yascha. 2018. The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How We Can Save It. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mounk, Yascha. 2023. The Great Experiment: Why Diverse Democracies Fall Apart and How They Can Endure. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Murse, Tom. 2018. Life of Robert McNamara, Architect of the Vietnam War. Thoughtco, September 25. Available online: https://www.thoughtco.com/robert-mcnamara-biography-4174414 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- NBC. 1965. The Decision to Drop the Bomb. NBC News, January 5. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, Ana-M., and Jorge Valenzuela. 2012. A study of the internal structure of critical thinking dispositions. Inquiry: Critical Thinking Across the Disciplines 27: 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noah, Timothy. 1998. Bill Clinton and the Meaning of “Is”. Slate, September 13. Available online: https://slate.com/news-and-politics/1998/09/bill-clinton-and-the-meaning-of-is.html (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Orwell, George. 1950. 1984. New York: Signet. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Richard. 2005. The state of critical thinking today. New Directions for Community Colleges 130: 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Richard, and Linda Elder. 2008. The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking: Concepts and Tools. The Foundation for Critical Thinking. Available online: https://www.criticalthinking.org/files/Concepts_Tools.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Pianin, Eric. 2017. North Korea Remains the Most Reviled Country Among Americans in New Poll. The Fiscal Times, February 21. Available online: https://www.thefiscaltimes.com/2017/02/21/North-Korea-Remains-Most-Reviled-Country-Among-Americans-New-Poll (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Pietschnig, Jakob, and Georg Gittler. 2015. A reversal of the Flynn effect for spatial perception in German-speaking countries: Evidence from a cross-temporal IRT-based meta-analysis (1977–2014). Intelligence 53: 145–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repucci, Sarah, and Amy Slipowitz. 2022. The Global Expansion of Authoritarian Rule. Freedom House. Available online: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2022/global-expansion-authoritarian-rule (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Rippenberger, Renée, Rachel B. Riedl, and Jonathan Katz. 2025. Targeting Higher Education Is an Essential Tool In the Autocratic Playbook. Brookings Institution, May 1. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/targeting-higher-education-is-an-essential-tool-in-the-autocratic-playbook/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Rivas, Silvia F., Carlos Saiz, and Carlos Ossa. 2022. Metacognitive strategies and development of critical thinking in higher education. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, Susan E., Isaac J. Handley-Miner, John D. Mayer, and David Caruso. 2020. Emotional intelligence. In Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence, 2nd ed. Edited by Robert J. Sternberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 709–35. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Paul H., and Lindsay Holcomb. 2020. Indoctrination and social influence as a defense to crime: Are we responsible for who we are? Missouri Law Review 85: 739–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwell, Sara. 2003. The life and legacy of Marie Curie. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 76: 167. [Google Scholar]

- Sackett, Paul R., Oren R. Shewach, and Jeffrey A. Dahlke. 2020. The predictive value of general intelligence. In Human Intelligence: An Introduction. Edited by Robert J. Sternberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 381–14. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokowski, Piotr, Agneiszka Sorokowska, Maciej Karwowski, Agata Groyecka, Toivo Aavik, Grace Akello, Charlotte Alm, Naumana Amjad, Afifa Anjum, Kelly Asao, and et al. 2020. Universality of the triangular theory of love: Adaptation and psychometric properties of the Triangular Love Scale in 25 countries. Journal of Sex Research 58: 106–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanovich, Keith E. 2009. What Intelligence Tests Miss. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanovich, Keith E. 2018. How to Think Straight About Psychology, 11th ed. London: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Stanovich, Keith E. 2021. The Bias That Divides Us: The Science and Politics of Myside Thinking. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 1997. Construct validation of a triangular love scale. European Journal of Social Psychology 27: 313–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 2000. Giftedness as developing expertise. In International Handbook of Giftedness and Talent. Edited by Kurt A. Heller, Franz J. Mönks, Robert J. Sternberg and Rena F. Subotnik. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 2003. A duplex theory of hate: Development and application to terrorism, massacres, and genocide. Review of General Psychology 7: 299–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 2004. What is wisdom and how can we develop it? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 591: 164–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 2021a. Adaptive intelligence: Intelligence is not a personal trait but rather a person x task x situation interaction. Journal of Intelligence 9: 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 2021b. AWOKE: A theory of representation and process in intelligence as adaptation to the environment. Personality and Individual Differences 182: 111108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 2022. The intelligent attitude: What is missing from intelligence tests. Journal of Intelligence 10: 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 2024. What is wisdom? Sketch of a TOP (tree of philosophy) theory. Review of General Psychology 28: 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 2025a. The other half of intelligence: An obstacle-racecourse performance-based model of intelligence in action. Intelligence 110: 10919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 2025b. PTSI: A person x task x situation interaction theory of creativity. Journal of Creative Behavior 59: e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 2025c. When we love (or hate) ideas too much: Love (or hate) of ideas as impediments to critical thinking. In Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking. Edited by Robert J. Sternberg and Weihua Niu. London: Palgrave-Macmillan, vol. 1, pp. 171–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, Robert J., Arezoo Soleimani-Dashtaki, and Banu Baydil. 2024a. An empirical test of the concept of the adaptively intelligent attitude. Journal of Intelligence 12: 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternberg, Robert J., Arezoo Soleimani-Dashtaki, and Seamus A. Power. 2024b. The Wonderland Model of toxic creativity in leadership: When the “Never Again” impossible becomes not only possible but actual. Possibility Studies and Society 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J., and Karin Sternberg. 2024. A RELIC theory of love: The role of interpersonal, intrapersonal, and extrapersonal elements in love. Theory and Psychology 34: 671–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J., and Weihua Niu, eds. 2025a. Critical Thinking Across Disciplines: Theory and Classroom Practice. London: Palgrave-Macmillan, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, Robert J., and Weihua Niu, eds. 2025b. Critical Thinking Across Disciplines: Applications in the Digital Age. London: Palgrave-Macmillan, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, Robert J., Emily R. Hurwitz, Angel H.-C. Hwang, and Melanie K. Kuhl. 2022. Love of one’s musical instrument as a predictor of happiness and satisfaction with musical experience. Psychology of Music 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J., Mahzad Hojjat, and Michael L. Barnes. 2001. Empirical aspects of a theory of love as a story. European Journal of Personality 15: 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, Robert J. 1987. Teaching for thinking: A developmental model for the infusion of thinking skills into mainstream instruction. In Teaching Thinking Skills: Theory and Practice. Edited by Joan B. Baron and Robert J. Sternberg. New York: W. H. Freeman and Co, pp. 106–26. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz, Robert J., Arthur L. Costa, Barry K. Beyer, Rebecca Reagan, and Bena Kallick. 2008. Thinking-Based Learning: Activating Students’ Potential. Norwood: Christopher-Gordon Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Tanenhaus, Sam. 1997. Whittaker Chambers. New York: Penguin Random House. [Google Scholar]

- The Nobel Prize. 2018. Women Who Changed Science: Marie Curie. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/womenwhochangedscience/stories/marie-curie (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Wagner, Richard K., and Robert J. Sternberg. 1984. Alternative conceptions of intelligence and their implications for education. Review of Educational Research 54: 179–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Well, Tara. 2023. The Decline of Critical Thinking Skills. Psychology Today, July 5. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-clarity/202306/the-decline-of-critical-thinking-skills (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Zajonc, Robert B. 2001. Mere exposure: A gateway to the subliminal. Current Directions in Psychological Science 10: 224–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziblatt, Stephen, and David Levitsky. 2018. How Democracies Die. New York: Crown. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbardo, Philip. 2008. The Lucifer Effect: How Good People Turn Evil. New York: Penguin Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Zubok, Vladislav M. 2009. A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

| I. Cognitive Track (Metacomponents) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition of Problem Definition/Analysis of Problem Acceptance of Problem Mental Representation of Problem Allocation of Resources for Problem Solution Formulation of Strategy for Problem Solution Monitoring of Solution Strategy Evaluation of Solution | |||

| II. Attitudinal/Dispositional Track | |||

| Positive Effects | Negative Effects | ||

| Information Seeking | Adequate Information | Inadequate Information | |

| Desire to Think Analytically/Critically | Deep Analysis | Superficial Analysis | |

| Willingness to Adopt Multiple/Alternative Perspective | Multi-Perspective Analysis | Uni-Perspective Analysis | |

| Willingness to Question One’s Own or Others’ Solutions | Questioning of Solution | Uncritical Acceptance of Solution | |

| Caring If Solution Is Optimal | Optimizing | Satisficing | |

| Willingness to Think “Outside the Box” | Creative Solution | Pedestrian Solution | |

| Asking: Optimality for Whom? | Common-Good Solution | Egocentric-Good Solution | |

| III. Affective Track | |||

| Positive Effects | Negative Effects | ||

| Love | |||

| Intimacy | Familiarity with Problem and Requirements | Entrenchment in Solving Problem | |

| Passion | Burning Desire for a Solution | Positively Motivated Distortion | |

| Commitment | Will See Problem through to the End | Cognitive Commitment to Positive Distortion | |

| Hate | |||

| Negation of Intimacy | Desire to Distance/Separate from Agents | ||

| Passion | Negatively Distorted Motivations | ||

| Commitment | Cognitive Commitment to Negative Distortion | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sternberg, R.J.; Hayes, A.J. Why Critical Thinking Can and Often Does Fail Us in Solving Serious Real-World Problems: A Three-Track Model of Critical Thinking. J. Intell. 2025, 13, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13070073

Sternberg RJ, Hayes AJ. Why Critical Thinking Can and Often Does Fail Us in Solving Serious Real-World Problems: A Three-Track Model of Critical Thinking. Journal of Intelligence. 2025; 13(7):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13070073

Chicago/Turabian StyleSternberg, Robert J., and Aurora Jo Hayes. 2025. "Why Critical Thinking Can and Often Does Fail Us in Solving Serious Real-World Problems: A Three-Track Model of Critical Thinking" Journal of Intelligence 13, no. 7: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13070073

APA StyleSternberg, R. J., & Hayes, A. J. (2025). Why Critical Thinking Can and Often Does Fail Us in Solving Serious Real-World Problems: A Three-Track Model of Critical Thinking. Journal of Intelligence, 13(7), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13070073