1. Introduction

The reading circle method was first introduced in 1982 by Karen Smith when the book club application was adapted to the school environment, and the name of this method was first given by Kathy Short and Gloria Kaufman in 1984 (

Tosun 2018). Developed to improve reading skills and provide in-depth comprehension of what is read (

Levy 2019), this method is a versatile and high-level reading method that offers individual and group reading opportunities and includes many reading techniques and strategies (

Amalia 2025;

Briggs 2010;

Mohamed 2023).

The reading circle, a student-centered reading method, is shaped according to constructivism theory (reader-response theory, schema theory) and socio-cultural theory (

McElvain 2010;

Schoonmaker 2014). In this method, which offers the opportunity to experience a multifaceted reading process around these theories, groups formed by the readers’ choices are provided with the opportunity to first read individually a text selected by the readers and then discuss it in groups (

Cloonan et al. 2020). Thus, it offers readers a collaborative reading experience that combines individual and group reading (

Tracey and Morrow 2006).

Reading circles, which are accepted as an effective reading tool in the education system today, enrich and shape personal learning experiences by increasing interpersonal interaction with this group-oriented perspective (

Goa and Wodai 2022;

Widodo 2016). This interactive experiential process should be structured according to certain principles regardless of the age group or applied environment. The principles that should be followed in the application process of the reading circle method are as follows (

Moeller and Moeller 2007;

Daniels 2002):

Students choose the materials they will read.

Small discussion groups are formed according to the book selection.

Group roles should be changed constantly.

Different groups read different books.

Groups meet regularly on specified dates.

Students take notes to guide their reading and discussion.

Discussion topics are determined by students.

Open-ended, natural discussion is aimed at group meetings.

The teacher’s role is guidance.

Teacher observation and self-assessment are used together in evaluation.

Fun should be part of the application.

When the books are finished, each group shares the books they have read with the class through presentations, dramas and other projects.

New groups are formed according to new books, and the cycle continues.

In reading circles, the main element that provides different perspectives, creates a suitable discussion environment and forms the basis of this method is the set of roles that students prefer in their reading experience (

Tomlinson and Strickland 2005). These roles are divided into two types: basic and optional roles (

Daniels 2002). The basic roles are connection maker, questioner, section expert and painter. The optional roles are summarizer, word hunter, action scout, character master and observer. In each circle, the distribution of roles is essential. Group members should each have a role during the discussion; the aim of these roles is to examine and analyze the reading material according to the role during the individual reading process. In accordance with the roles determined before the discussion process, carried out as a group within the framework of the reading circle principles, each group member participates in the discussion according to the role they have undertaken and shares the information they have acquired in this role axis with their group members (

Chung and Lee 2012). This system, which puts the individual at the center, offers readers new perspectives with constantly changing roles while also providing the opportunity to recognize the different perspectives of these roles through a collaborative learning experience in group discussions (

Calzada 2013;

Tracey and Morrow 2006).

In this method, readers actively participate in the reading process and are able to think deeply about the text, discuss it and examine it from an analytical perspective. In group discussions, readers exchange ideas on the text, and their interpretations of the text provide an opportunity to others to gain different perspectives (

McElvain 2010). At the same time, the social interaction created by these group discussions, which are structured within the framework of equality, respect and active participation, allows everyone to share their ideas freely and interpret the evaluated text from different perspectives (

Morris and Perlenfein 2002). In this way, it both supports individual learning and provides the opportunity to gain collective knowledge by allowing readers to contribute to the creation of a collective meaning by using group dynamics and bringing together different interpretations (

Hathaway 2011).

Reading circles are not only a reading method but also an effective reading platform that develops individuals’ social and emotional dimensions and offers them the opportunity to express themselves and participate. It is often used by educators to deepen the process of understanding the text and is also applied in terms of acquiring new strategies (

Certo et al. 2010). These reading activities, which are performed in groups, allow for the establishment of connections between readers and the strengthening of relationships between them while also turning this process into an enjoyable and educational experience (

Brownlie 2005). In this method, readers are given the opportunity to express themselves, listen to each other respectfully, understand each other and develop a social consciousness. Thus, it contributes to both personal and social development (

Calzada 2013).

The literature studies on the reading circle method, which is one of the effective methods that enable the reading process to be carried out consciously, have mainly focused on the development of reading habits, reading interest, reading motivation, reading comprehension strategies, reading comprehension skills and vocabulary (

Amalia 2025;

Avcı et al. 2013;

Avcı and Yüksel 2011;

Balantekin and Pilav 2017;

Briggs 2010;

Camp 2006;

Çağ 2024;

Goa and Wodai 2022;

Karatay 2015,

2017;

Tosun 2018;

Küçük 2024;

Mete 2020;

Monaghan 2016;

Mrak 2021;

Novasyari 2021;

Nurhadi 2017;

Olsen 2007;

Qie et al. 2023;

Pitton 2005;

Rahman 2022;

Rutherford et al. 2009;

Riswanto et al. 2023;

Rahayu and Suryanto 2021;

Sarı et al. 2017;

Suci et al. 2022;

Smith and Feng 2018;

Tekin 2019;

Topçam 2022;

Xu 2021;

Varita 2017;

Yardım 2021;

Yıldırım et al. 2019;

Zafar et al. 2021;

Zhang 2023). These studies have focused on the many different uses of reading circles in different areas, such as the role of fairy tales in reading circles (

Kitsanu et al. 2024), academic reading circles (

Vartola 2024), the use of reading circles in teaching reading and writing (

Yang 2023), the effect on speaking skills (

Kaowiwattanakul 2020;

King 2001;

Matmool and Kaowiwattanakul 2023), the effect of quality conversation in reading circles on thinking skills (

Kast 2024), the effect on speaking and pronunciation in foreign language teaching (

Liu 2022;

Su et al. 2019;

Sutrisno et al. 2019;

Yakut 2020), the effect on identity development (

Le 2021), the effect in the field of nursing (

Begoray and Banister 2008), the effect on developing social skills of engineers (

Pacheco and Cervantes 2022) and the effect on socio-emotional development (

Venegas 2019). The effect of this method in different areas can be evaluated because reading skills are one of the basic tools for acquiring knowledge in every field, as well as comprising multiple other skills that include different language skills and emotional skills.

Although various studies have been conducted in the literature on reading circles, which are one of the high-level reading methods with these qualities, studies conducted with teacher candidates, including the effect of reading circles on the reading process (

Çermik et al. 2019;

Çetinkaya and Topçam 2019;

Doğan et al. 2018,

2019,

2020;

Karatay 2017), its effect on internal reading (

Rutherford et al. 2009), its effect on critical literacy skills (

Baki 2022), its effect on reading culture (

Baki 2023), its effect on interaction and meaning-making (

Vijayarajoo 2015), its effect on teaching informative text structure (

Clark 2021;

Diego-Medrano et al. 2016), teacher candidates’ perceptions of reading circles (

Aytan 2018), their perceptions of their abilities (

Walker and Castillo 2023), social justice (

Madhuri et al. 2015) and their perception of social justice (

Wexler 2021), their upbringing as representatives of social justice (

Davis and Bush 2021), their teaching of the concept of equality (

Robertson and Sivia 2025), their social interactions (

Calzada 2013), their impact on cultural development (

Heineke 2014) and their impact on reflective practices (

Ahmed et al. 2024) have also been studied. These studies support the reading circle method as a remarkable reading method that stands out among contemporary educational approaches and offers opportunities for developing reading skills and different social skills in a multifaceted way.

However, the basic key to reading, learning and discovering new things is the sense of curiosity (

Yazıcı and Kartal 2020). The importance of the sense of curiosity in education is increasingly emphasized and is accepted as an important incentive element for individuals to actively participate in their own learning processes. Curiosity and discovery, which are key factors that increase individuals’ motivation to learn, also have a role in increasing reading comprehension (

Gurning and Siregar 2017). In the research of

Kırmızı and Kapıkıran (

2019), it was determined that there was a significant relationship at an average level between teacher candidates’ perceptions of curiosity and discovery and their reading habits. Although the reading circle method encourages the sharing of information among readers and provides the opportunity to discover different perspectives and develop original thoughts, it can be said that no research has been found in the literature on the effect of this method, which is woven with various reading strategies, on curiosity and discovery. In addition, the reading circle method encourages readers to approach the text from different perspectives, to reconstruct the text using critical and creative thinking skills and to create new meanings with this learning opportunity that is offered in groups at certain intervals (

Daniels 2002). According to

Nardelli (

2013), the reaction and integration phases of the reading process, which consists of four areas—perception, comprehension, reaction and integration—fall within the scope of creative reading skills. In reading circles, the environment provided for readers to discover different perspectives and create original thoughts is among the elements that support the creativity of readers. Creative reading skills, which are based on creativity and the ability to read between the lines, aim to look for what is different or new in the text and to notice what is not seen in the text, thus ensuring that the development of the sense of curiosity is constantly kept alive during the reading process and feeds the reading process (

Al Qahtani 2016;

Small and Arnone 2011;

Uysal and Coşkun 2023). This is because the active use of creative reading skills in the reading process serves to integrate the ideas and experiences in the texts, to discover hidden meanings and implicit relationships with symbols and signs in the texts, to develop new ideas and to integrate innovations with life (

Hızır 2014). The reading process, which can also be called a discovery experience (

Zhang and Sun 2011), has been described in two studies on the effects of reading circles on creative writing skills and writing motivations (

Helmy 2020) and creative reading skills (

Mohamed 2023) in relation to creativity in reading circles, which focus on the reconstruction and creation of the text. It can be said that studies on creativity are limited in the studies conducted on reading circles.

In addition to language skills, another element that supports creativity in the reading process is visuals (

Stokes 2005). Today, the cultural language that visuals create for themselves increasingly surrounds every aspect of life, so they come to the forefront as one of the skills that individuals must have (

Hattwig et al. 2012;

Parsa 2007). In addition, visuals, which are one of the increasingly important elements that support creativity and the reading process today, are important elements that contribute to the concretization of information in texts and the expansion of meaning, as well as the development of aesthetic understanding in readers (

Sarıkaya 2017). The skill pattern that enables the active use of visual skills is defined as visual literacy (

Elkins 2003;

Siegel 2006). The role of the painter (artist), which is among the main roles in reading circles, also focuses on the development of these skills in the reading process. However, when the studies on reading circles are examined, it can be said that no research has been conducted on the effect of visual literacy competencies. In addition, when studies on teacher candidates are examined, it is stated that they do not have the necessary knowledge regarding visual literacy competencies and that the professional development of teacher candidates should be contributed to with methods and techniques that will enable them to develop these skills (

Ateş et al. 2020;

Çelik and Çelik 2014;

Şakiroğlu 2021).

When the existing studies on reading circles are evaluated in terms of research methods, it can be said that the use of this method is surrounded by various experimental or qualitative studies on its effect on reading skills and social skills (

Baki 2022,

2023;

Çermik et al. 2019;

Doğan et al. 2018,

2019;

Karatay 2017) and that mixed studies conducted with prospective teachers are limited (

Sarı et al. 2017;

Tosun 2018).

Tavşanlı and Ulaş (

2023) stated that the reading circle method is defined by teachers as a fun and effective method, that its use is recommended by teachers and that interest in this method has increased especially after 2015. However, the studies so far focus more on reading comprehension skills and are more quantitative, and in addition to these results, it is emphasized that prospective teachers should also be introduced to the reading circle method. In the research, it was stated that there are limited studies on this method with prospective teachers and that a significant amount of research is still needed in this area; it would be of benefit to see how reading circles affect different skills as well as reading skills and the general framework (

Tavşanlı and Ulaş 2023). In the qualitative research conducted by

Çetinkaya and Topçam (

2019) with eight prospective teachers, the effect of reading circles on enriching the views of prospective teachers about the teaching profession was investigated, and as a result of the research, the participants stated that this method changed their views about the teaching profession positively. The use of the reading circle method in developing the reading skills of teachers and future prospective teachers is emphasized in numerous studies (

Allan et al. 2005;

Çetinkaya and Topçam 2019;

Daniels 2002;

Schoonmaker 2014). Based on the view that the reading circle is an important method for the professional development of teachers (

Çermik et al. 2019;

Çetinkaya and Topçam 2019;

Doğan et al. 2019), it can be said that there is a need to teach this method to both teachers and prospective teachers and to examine the effect of this method on their development.

It is anticipated that the examination of the reading circle method’s effect on Turkish teacher candidates’ curiosity and discovery, creative reading skills and visual literacy competencies will make significant contributions to the literature. It is believed that this study will provide teacher candidates with the opportunity to learn a new reading method during their pre-service education and that examining the effects of this method will make significant contributions to their personal development and their use of the method in their professional lives. Within the framework of these objectives, the following problems were sought in the current study:

Does the reading circle method create a significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores of Turkish teacher candidates in creative reading skills?

Does the reading circle method create a significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores of Turkish teacher candidates in curiosity and discovery perceptions?

Does the reading circle method create a significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores of Turkish teacher candidates in visual literacy competencies?

What are the views of Turkish teacher candidates regarding the effects of the reading circle method on creative reading skills, curiosity and discovery perceptions and visual literacy competencies?

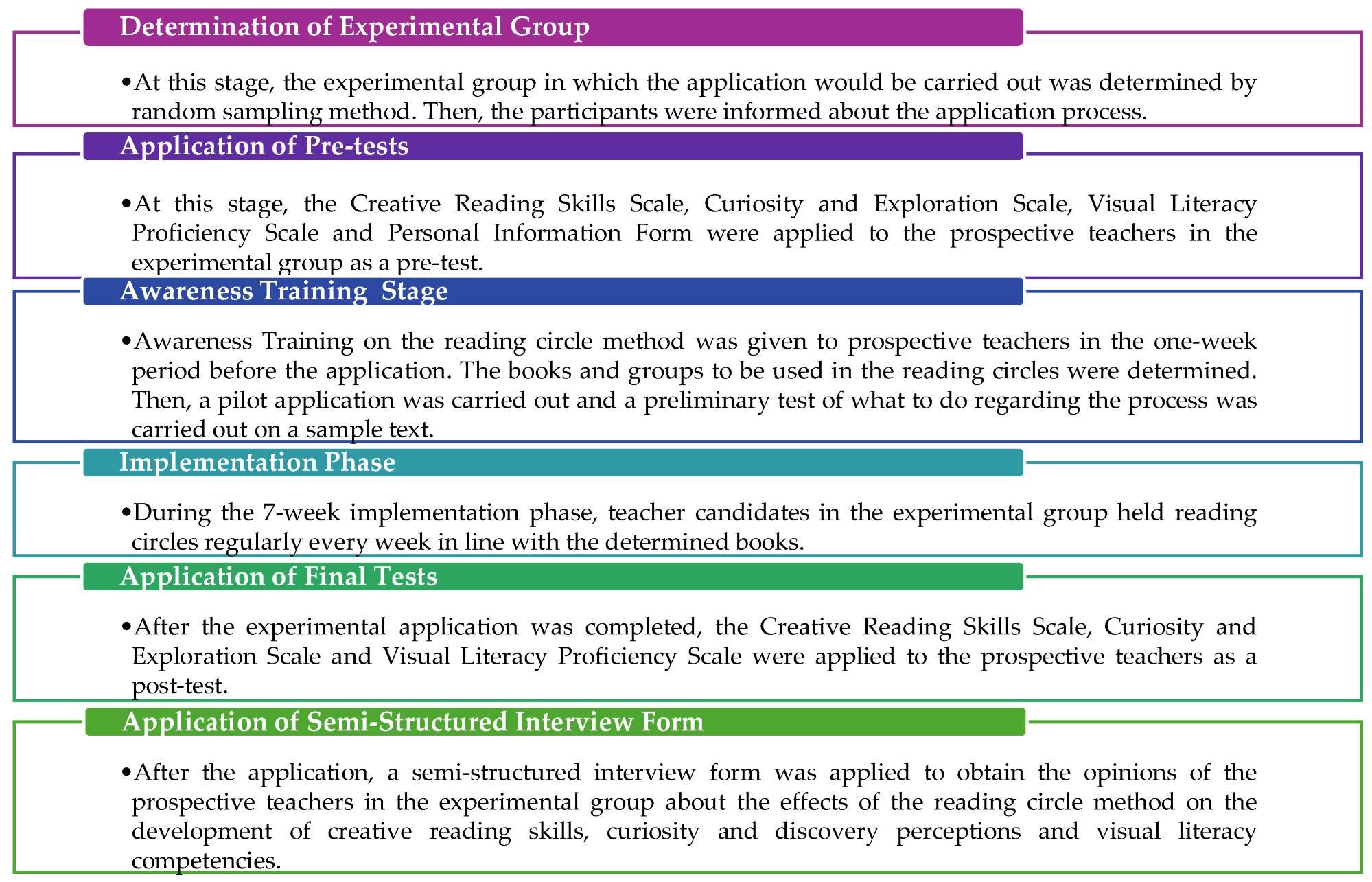

4. Discussion

This study examined the impact of the reading circle method on pre-service Turkish language teachers’ creative reading skills, perceptions of curiosity and exploration and visual literacy competencies. The findings revealed that the reading circle method significantly improved the participants’ creative reading skills. Similarly,

Mohamed’s (

2023) study with pre-service teachers also found that reading circles significantly enhanced creative reading abilities. Further analysis of the subdimensions of creative reading skills indicated that reading circles had a notable effect on structuring the text, identifying the purpose of the text and making predictions related to the text. The qualitative findings of this study revealed that the reading circle method contributed most significantly to recreating the text, creative thinking, generating new meanings and the development of imagination. Similarly, previous studies have shown that this method enhances pre-service teachers’ creative thinking skills (

Al Qahtani 2016;

Çermik et al. 2019) and imaginative abilities (

Baki 2023). Since creative reading is considered an outcome of the use of creative thinking skills (

Priyatni and Martutik 2020;

Yurdakal 2019), it can be argued that this method also fosters a variety of skills that support creative reading. Indeed, the qualitative data indicated that the method also contributes to the development of other skills such as critical thinking and flexible thinking. These findings are consistent with previous research indicating that discussions within reading circles significantly enhance critical thinking skills (

Baki 2022;

Çermik et al. 2019;

Karatay 2017;

Matmool and Kaowiwattanakul 2023;

Pambianchi 2017).

Meaning-making, the most crucial stage of the reading process, involves the unfolding of meaning from the surface structure (concrete level) to the deep structure (abstract level) (

Onan 2015). Creative reading, on the other hand, goes beyond simply connecting the surface and deep structures—it involves discovering new and different meanings within a text and reconstructing the text itself (

Litman 2017;

Priyatni and Martutik 2020). The qualitative findings of this study revealed that the reading circle method contributed to deep understanding of texts, analyzing the multi-layered structure of meaning and shifting from surface-level to in-depth reading. Previous studies have also shown that this method helps pre-service teachers identify the theme and main idea of a text (

Karatay 2017), enrich their vocabulary (

Aytan 2018;

Çermik et al. 2019) and improve their deep/inferential comprehension (

Avcı et al. 2013;

Baki 2023;

Levy 2019;

Mete 2020). Moreover, it can be stated that this method is a multifaceted approach that supports the development of text examination, comprehension, analysis and evaluation skills (

Clark 2021;

Karatay and Soysal 2021), as well as overall reading comprehension abilities (

Goa and Wodai 2022;

Liu 2022;

Novasyari 2021;

Nurhadi 2017;

Purifico 2015;

Rahman 2022;

Riswanto et al. 2023;

Varita 2017;

Vijayarajoo 2015).

In the creative reading process, the reader’s emotional responses, which emerge from connections established with characters in the text or with their own prior knowledge, are among the factors that can influence the reading process either positively or negatively (

Nardelli 2013). In this study, the evaluation of the subdimensions of creative reading skills revealed that reading circles had a significant impact in terms of focusing on values within the text and establishing connections with the characters. Studies have shown that active participation in reading circles enables readers to establish connections between the text and their prior knowledge (

Cloonan et al. 2020;

Mrak 2021;

Whittingham 2013), as well as between the text and their own experiences and lives (

Ahmed et al. 2024;

Baki 2023;

Tosun and Doğan 2020). It can be stated that this outcome is also influenced by the connecting role of the method, which helps readers interact with what they have learned by linking it to their personal lives. Indeed, the qualitative findings of this study indicate that the method contributes positively to the development of empathy with characters, multidimensional evaluation of characters, building connections between characters and real life, analyzing values in the text and recognizing the significance of those values. Studies in the literature have also shown that reading circles contribute positively to pre-service teachers’ respect for diversity (

Doğan et al. 2019), the development of their self-efficacy beliefs (

Özbay and Kaldırım 2015) and improvements in self-esteem, self-confidence, motivation and empathy (

Ahmed et al. 2024;

Aytan 2018;

Kim 2004;

Monaghan 2016). Additionally, reading circles have been found to enhance self-regulation (

Baki 2022;

Su et al. 2019), the multidimensional analysis of characters (

Çetinkaya and Topçam 2019) and the ability to adopt different perspectives (

Aytan 2018;

Çermik et al. 2019;

Çetinkaya and Topçam 2019;

Doğan et al. 2019;

Tracey and Morrow 2006). It can be stated that reading circles, through their positive contributions to the development of socio-emotional skills (

Brown 2015;

Venegas 2019), promote the emotional factors essential for creative reading by activating various emotions and modes of thinking (

King 2001;

Sarı et al. 2017). The internalization of the text and the emotionally supportive environment created for creative reading were found to enhance affective variables of reading, such as reading motivation (

Meredith 2015;

Smith and Feng 2018) and attitudes toward reading (

Qie et al. 2023).

In the qualitative findings obtained from this study, it was determined that half of the pre-service teachers showed improvement in interpreting the text in depth, whereas the quantitative findings revealed no statistically significant difference in the interpretation subdimension of the Creative Reading Scale. This discrepancy may stem from several reasons. One possible explanation is the divergent results produced by the quantitative and qualitative data obtained from this mixed-methods study. While the quantitative dimension of this study produced generalizable results based on specific scales, the qualitative analysis revealed participants’ experiences and perceptions. One probable reason for this discrepancy may be the differences in measurement tools and methods. Since scales are limited to specific items, they may fall short in fully capturing the cognitive and affective experiences that occur during the reading process (

Creswell and Clark 2011). Moreover, the items in the scale may have reflected only certain aspects of text-structuring skills, whereas the interviews with participants might have allowed them to explain how they structured the text from a broader perspective. Another possible reason could be the individual differences in perception and expression among the teacher candidates, as they may have preferred to express themselves in a more personal and contextual language. Additionally, it is possible that the development of text-structuring skills occurred indirectly, which may not have been fully captured by the scale. During the group discussions, activities were conducted to identify the main idea and supporting details of the text; however, the measurement tool used may not have assessed these elements explicitly. Nevertheless, the participants may have recognized and expressed this development themselves. In the interviews, the teacher candidates conveyed their metacognitive awareness, which may not have been directly captured by the measurement tool (

Patton 2015). Furthermore, reading circles create socially interactive learning environments, which differ from individual reading processes. In this context, the skill of structuring the text may have developed through social interaction; however, the measurement tool used in this study may not have directly captured the contribution of such interaction to individual learning. Additionally, the characteristics of the reading circle method itself may have influenced this outcome. Specifically, structuring a text requires the reader to construct a conceptual framework, establish intertextual connections and create a coherent structure (

Kintsch 1998). Although reading circles contribute to individual meaning-making processes, it can be argued that students may require more systematic guidance and structured reading strategies during the process of text construction. Secondly, in reading circles, students often focus on interpreting the text and providing emotion-based responses to what they have read. This is because one of the foundational principles of this method is reader-response theory (

Hsu 2004). While this process may support the development of other dimensions of creative reading skills, it may not sufficiently promote the development of text construction skills (

McElvain 2010). Since the development of text construction skills requires analytical and cognitive strategies, it can be suggested that incorporating specific reading strategies under teacher guidance into the process may contribute to the enhancement of this particular skill. Another reason may be that the reading process in reading circles is discussion-oriented rather than individual, which may limit the development of text construction skills. In order for reading circles to support text construction, it is recommended to use various tools to identify the structural schema of the text, including the main idea and supporting details, or to incorporate these elements into appropriate role sheets (

Duke and Pearson 2017). Based on these findings, it can be stated that reading circles indirectly contribute to the text construction dimension of creative reading skills, and that this contribution needs to be supported through different methods and strategies in order to be made explicit.

When the findings regarding the effect of reading circles on creative reading skills are evaluated, it is observed that this method has a moderate to moderately strong and significant effect on the overall creative reading skills, particularly in focusing on the values embedded in the text and identifying the purposes for which the text was constructed. In other words, reading circles can be considered an effective, noteworthy and applicable method that leads to significant improvement in overall creative reading skills—particularly in focusing on the values embedded in the text (i.e., understanding the emotions, values and messages) and identifying the purposes for which the text was constructed (i.e., making inferences about the author’s intent and the text’s purpose). However, the method appears to have a relatively small effect on restructuring the text, making predictions about the text and establishing connections with the characters. In other words, it can be stated that the pre-service teachers demonstrated improvement in skills such as organizing the text and establishing logical structure, as well as in making predictions related to the text; however, these improvements remained limited to small effect sizes. Regarding the ability to connect with characters in the text, the method yielded a low-to-moderate effect, approaching the medium level. In other words, it can be concluded that reading circles led to a meaningful but partial improvement in emotional interaction skills such as empathizing with characters, though this effect was not particularly strong. In summary, it can be stated that reading circles had a more limited effect in terms of these three skills. Therefore, in order to enhance the development of these specific skills and strengthen the overall effectiveness of the method, it is necessary to restructure the implementation process by incorporating supportive interventions that include different or additional strategies.

According to another finding of this study, reading circles significantly influenced teacher candidates’ overall perceptions of curiosity and exploration, particularly in the subdimension of flexibility and acceptance of uncertainty. Although no previous studies have been found in the relevant literature specifically examining the effect of this method on curiosity and exploration perceptions, the qualitative findings support these results. Data obtained from the interviews indicated that reading circles primarily enhanced teacher candidates’ desire to discover new things, increased their curiosity for learning and improved their skills in questioning and inquiry. Similarly, in the study conducted by

Doğan et al. (

2019), it was found that this method improved teacher candidates’ inquiry and thinking skills. According to

Avcı et al. (

2013), chapter discussions within reading circles, the rotation of roles in each session and the process of reaching conclusions through reflection are among the key factors contributing to this outcome. These effects can be interpreted as a result of the “inquirer” role and the impact of group discussions. In this method, three types of questions are used: recall/closed-ended, interpretive/open-ended and personal. It is particularly expected that the reader in the inquirer role will prefer interpretive questions (

Moeller and Moeller 2007). In this study, the development of curiosity and exploratory perception may be attributed to the fact that the reader in the inquirer role chose interpretive questions, which aim to foster multidimensional thinking and allow for multiple responses. Indeed, qualitative findings from this study highlight that this method supports the development of research and deep-thinking skills, as well as the discovery of the value of diverse perspectives. These findings are also supported by previous research suggesting that this method, composed of actions that promote research skills (

Daniels 2002), enhances willingness to gather information (

Baki 2022), contributes to the development of information acquisition skills (

Doğan et al. 2021) and improves research skills (

Amalia 2025).

Doğan et al. (

2019) found that this method, by providing opportunities for the use of higher-order thinking skills such as inquiry, contributed to the development of teacher candidates’ thinking skills through gaining and broadening different perspectives. These findings can be interpreted as a result of the theoretical foundations upon which reading circles are based—namely, reader-response theory, schema theory and inquiry-based learning theory (

Daniels 2002;

Hsu 2004;

McElvain 2010).

Although various methods are used to satisfy an individual’s curiosity and desire for exploration, one of the most practical tools for discovering oneself and existence is reading. Among the prominent themes identified in the qualitative findings of this study are teacher candidates’ discovery of the deep structure of the text, uncovering new meanings of words and transforming the reading process into an act of exploration. In other words, it can be said that teacher candidates described reading as both an enjoyable and meaningful experience while also perceiving it as a tool for exploration through this method.

Tosun and Doğan (

2020) also revealed that reading circles enhance aesthetic reading skills—that is, the ability to derive pleasure from reading. Indeed, several studies have found that this method positively influences reading enjoyment and curiosity (

Baki 2023), as well as increases interest in reading (

Amalia 2025;

Doğan et al. 2021). The significant relationship between teacher candidates’ sense of curiosity and exploration and their attitudes toward reading (

Kırmızı and Kapıkıran 2019) also supports this finding. Among the qualitative findings of the present study, it was further noted that the process guided participants toward discovering the unknown, as well as toward self-discovery and an exploration of existence. Similarly, the contributions of reading circles to teacher candidates in terms of uncovering hidden talents (

Aytan 2018) and enhancing attention to detail (

Pambianchi 2017) are also consistent with these findings. This may be attributed to the fact that reading circles are grounded in a reader-centered approach based on reader-response theory (

Daniels 2002). Taken together, these results suggest that reading circles have a positive impact on fostering individuals’ sense of curiosity and discovery and that they serve to enhance teacher candidates’ intrinsic motivation to explore and inquire through reading.

When the findings regarding the impact of reading circles on the perception of curiosity and exploration are evaluated, it can be stated that the method has a limited yet meaningful effect approaching a moderate level on the overall perception of curiosity and exploration. In other words, this method can be considered to have a significant but limited impact on teacher candidates’ willingness to inquire, ask questions and seek new knowledge. It can be suggested that this method has a small but significant effect on flexibility-related skills such as being open to different perspectives and restructuring one’s thinking. In terms of the dimension of tolerating uncertainty—namely, coping with ambiguity and accepting multiple meanings—it appears to provide a more limited contribution, and this effect can be considered to remain at a minimal level. Based on these findings, it can be concluded that reading circles can be used as a supportive tool that significantly enhances pre-service teachers’ sense of curiosity and exploration. However, in order to increase this effect, it is necessary to supplement the method with different strategies and practices.

Another finding obtained from the research indicates that the reading circle method produced a statistically significant difference in the overall visual literacy competencies of pre-service teachers, as well as in the subdimensions of defining printed visuals, distinguishing visual messages in daily life, producing visuals using tools and perceiving messages in visuals. According to the qualitative findings obtained from the research, it can be stated that this method positively contributes to the development of conscious visual literacy among pre-service teachers by enhancing their abilities to produce visuals, make sense of visuals, analyze and interpret visual messages and recognize the importance of visuals. When the qualitative and quantitative findings are evaluated together, it can be concluded that the contributions provided by reading circles enabled pre-service teachers to evaluate visuals as texts, because like texts, visuals possess a multi-layered structure, and reaching the true meaning in visuals requires a conscious decoding of these layers (

Parsa 2007). In this method, the acquisition of such gains may also be influenced by the role of the illustrator (artist), who is responsible for conveying what has been understood from the text through images, graphics, diagrams or charts (

Bernadowski and Morgano 2011). Similarly,

Doğan et al. (

2018) state that the illustrator role provides an opportunity to use visuals as an effective strategy for making sense of the texts being read, which in turn has a positive impact on the development of reading skills.

Brabham and Villaume (

2000) also found that the illustrator role positively influences participants’ ability to create visual imagery, comprehend textual meanings and construct personal interpretations. Furthermore, it can be stated that teacher candidates’ use of the visual strategy of creating images with visual tools and designing promotional posters for each book in the reading circles contributed significantly to the effectiveness of the implementation. Indeed,

Doğan et al. (

2019) found that discussions about visuals in books and the use of visuals enhanced teacher candidates’ concretization skills and imagination, thereby creating a more effective reading environment and contributing to more permanent learning. In fact, proficient readers often use various strategies to comprehend texts, such as visualizing the content and making connections between the text and real-life experiences (

Brabham and Villaume 2000;

Brownlie 2005). Similarly, studies conducted with teacher candidates have shown that reading circles contribute to various visual literacy gains, such as enhancing visual thinking, interpreting and analyzing visuals and structuring visual information (

Baki 2023), as well as improving photography skills (

Çermik et al. 2019). The qualitative findings of this study also revealed that this method fosters the ability to interpret visual images and symbols and supports the development of visual creativity and aesthetic appreciation. These findings can also be interpreted as an indication of an increased awareness among participants regarding the figurative and symbolic power of visuals. Previous studies have shown that this method enhances teacher candidates’ imagery abilities (

Baki 2023) and aesthetic appreciation (

Aytan 2018). Based on these findings, it can be stated that reading circles contribute not only to the cognitive dimension of visual literacy skills but also to the development of their affective dimension.

Bernadowski and Morgano (

2011) also emphasize that the rotation of roles in each session enables readers to experience every role, thereby fostering the development of all reading-related skills, including verbal, written and visual literacy.

According to the quantitative findings of this study, this method did not yield a statistically significant difference in the dimensions of “valuing visuals through Office software” and “interpreting visuals” within the Visual Literacy Proficiency Scale. However, the qualitative findings revealed that more than half of the prospective teachers expressed that the method contributed to their ability to analyze and interpret visuals in printed texts. In

Baki’s (

2023) study, it was found that this method contributed most significantly to the development of prospective teachers’ ability to interpret and make meaning of visuals among the various visual reading skills. In reading circles, not only drawing but also digital designs can be used to visually convey the meaning derived from the texts (

Bernadowski and Morgano 2011). This may be due to the fact that, in the current study, prospective teachers preferred to use Web 2.0 tools rather than Office software while designing posters. Moreover, this may also be attributed to the fact that, in addition to Web 2.0 tools, artificial intelligence tools are more suitable than Office software for designing more effective visuals. Additionally, this situation may have resulted from the research methodology itself. As a matter of fact, in mixed-method research, it is possible for quantitative and qualitative findings to yield contradictory or non-overlapping results; however, such discrepancies offer an opportunity for a deeper understanding of the findings (

Teddlie and Tashakkori 2009). This situation may also stem from the limitations of the measurement instrument, which might have been insufficient in capturing the participants’ experiences in depth. In this context, the visual interpretation dimension being assessed consists of abstract and multi-layered skills that are subjective and vary across individuals; therefore, the scale items may have been inadequate in reflecting these aspects (

Mertens 2019). Another possible reason is that participants may not have been aware of these skills prior to the implementation, and as a result, this might not have been reflected in the scale responses. However, during the interviews, when they had the opportunity to reflect on these concepts and share their experiences, these skills may have become more visible. Additionally, considering that visual literacy is an interpretive and creative skill, the use of open-ended questions and reflective expressions might have been more functional for its assessment compared to the existing scale. When the current inconsistency is considered in terms of reading circles, it may be that the socially interactive environment provided by this method fostered greater development in the interpretation and comprehension of visuals; however, the scale used might not have been sufficiently sensitive to capture this change.

When the results regarding the effects of reading circles on visual literacy competencies are evaluated, it can be stated that this method had a large effect and led to a remarkably high level of improvement particularly in distinguishing visual messages and in visual production skills. In other words, it can be stated that this method is effective and applicable in terms of providing significant improvement in the skills of analyzing and interpreting visual messages as well as producing visuals using digital tools. On the other hand, the method appears to have a low but meaningful effect on recognizing printed visuals, perceiving the messages in visuals and overall visual literacy competencies. Furthermore, it was found that reading circles did not have a significant impact on presenting visuals using Office software or on visual interpretation. Based on this, it can be concluded that while the method influences certain dimensions of visual literacy competencies, its impact on other dimensions is insignificant. Overall, the method exerts a low-level yet meaningful and limited effect on general visual literacy competencies. To enhance this limited effect and contribute more significantly to the development of these competencies, it is recommended that the method be supported with various visual strategies and digital tools.