Abstract

The widespread application of Generative Artificial Intelligence (Gen-AI) is transforming educational practices and driving pedagogical innovation. While cultivating higher-order thinking (HOT) represents a central educational goal, its achievement remains an ongoing challenge. Current evidence regarding the impact of Gen-AI on HOT is relatively fragmented, lacking systematic integration, particularly in the analysis of moderating variables. To address this gap, a meta-analysis approach was employed, integrating data from 29 experimental and quasi-experimental studies to quantitatively assess the overall impact of Gen-AI on learners’ HOT and to examine potential moderating factors. The analysis revealed that Gen-AI exerts a moderate positive effect on HOT, with the most significant improvement observed in problem-solving abilities, followed by critical thinking, while its effect on creativity is relatively limited. Moderation analyses further indicated that the impact of Gen-AI is significantly influenced by experimental duration and learners’ self-regulated learning (SRL) abilities: effects were strongest when interventions lasted 8–16 weeks, and learners with higher SRL capacities benefited more substantially. Based on the research findings, this study proposed that Gen-AI should be systematically integrated as a targeted instructional tool to foster HOT. Medium- to long-term interventions (8–16 weeks) are recommended to enhance learners’ problem-solving and critical thinking abilities. At the same time, effective approaches should also be explored to promote creative thinking through Gen-AI within existing pedagogical frameworks. Furthermore, individual learner differences should be accounted for by adopting dynamic and personalized scaffolding strategies to foster SRL, thereby maximizing the educational potential of Gen-AI in cultivating innovative talents.

1. Introduction

Higher-Order Thinking (HOT), as a core competency of 21st-century skills, has been internationally recognized as a central objective for promoting students’ holistic development and fostering innovative capabilities. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD 2019) emphasizes that in an increasingly complex social environment, higher-order thinking skills, such as critical thinking and creativity, hold profound educational value and societal significance. Several countries, including the United States and Singapore, have formally incorporated HOT into their national education policy frameworks, establishing it as a strategic competency essential for future learners (OECD 2019; Ministry of Education Singapore 2021).

In recent years, the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly Generative Artificial Intelligence (Gen-AI), has ushered HOT cultivation into a new stage with disruptive potential. Since the launch of ChatGPT in late 2022, Gen-AI has profoundly reshaped the interactions between humans, knowledge, and technology through its advanced natural language processing and multimodal generation capabilities (Arista et al. 2023; Costa et al. 2024). This technology can instantaneously generate diverse learning resources, including text, images, and videos, significantly enhancing the accessibility of educational content and the personalization of learning support. Such advancements not only expand learners’ cognitive exploration possibilities but also drive a shift in educational paradigms from traditional knowledge transmission toward technology-enhanced deep learning.

Empirical evidence suggests that Gen-AI demonstrates considerable potential in fostering HOT. By providing rich, contextualized learning materials, Gen-AI can support the development of critical thinking and facilitate multi-path problem solving (Li et al. 2024b; Pujawan et al. 2022). Furthermore, its real-time feedback mechanisms stimulate creative thinking and encourage the exploration of diverse solutions. Leveraging highly interactive and dynamic support, Gen-AI can assist learners in engaging with more complex, higher-order cognitive processes, thereby effectively promoting the systematic development of HOT (Huang et al. 2024a).

However, the integration of Gen-AI in education also raises concerns. Studies indicate that excessive reliance on AI-generated content may weaken learners’ self-directed learning and self-regulation capabilities (Sun et al. 2025). Biases and factual inaccuracies embedded within algorithms may mislead judgment and hinder the development of critical thinking. Scholars further caution that inappropriate use of Gen-AI could constrain autonomous exploration, suppress creativity, and introduce ethical, privacy, and academic integrity risks (Costa et al. 2024). These issues underscore the urgency of carefully examining the mechanisms and boundaries of Gen-AI’s impact on HOT.

Overall, despite preliminary progress in research on the relationship between Gen-AI and HOT, existing findings remain fragmented and inconsistent. Some studies highlighted the positive effects of AI technologies on enhancing critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving skills, while others warn of potential cognitive dependency and associated risks. Most existing research is limited to small-scale experiments or case studies, lacking cross-disciplinary, multi-contextual integration, with insufficient attention to underlying mechanisms and moderating variables. Therefore, it is imperative to employ the meta-analysis method to synthesize existing empirical evidence quantitatively, systematically assess the overall effects of Gen-AI on HOT, and explore its mechanisms and boundary conditions, thereby providing robust theoretical and evidence-based guidance for educational practice and policy development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptualizing HOT

The theoretical origins of HOT can be traced back to Benjamin Bloom’s (1956) taxonomy of educational objectives. Bloom’s framework categorized cognitive goals into six hierarchical levels—knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation—marking the first systematic distinction between higher-order and lower-order cognitive processes. Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) later revised Bloom’s taxonomy, reorganizing cognitive processes into remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating, and notably emphasizing “creating” as the pinnacle of cognitive development. This revision further clarified the progression from foundational cognition toward critical evaluation and innovative thinking. From an information-processing perspective, Lewis and Smith (1993) proposed that HOT constitutes a systematic cognitive process through which individuals reorganize, extend, and deeply process information, integrating it with existing knowledge structures to achieve goals or solve complex problems. Despite variations in conceptual definitions across the literature, there is a broad consensus that HOT represents an integrated cognitive capacity, highly dependent on metacognitive awareness and complex cognitive functions, characterized by more profound, more complicated, and reflective thinking processes (including classic dimensions such as analysis, evaluation, and creation/synthesis) that demonstrate both cognitive sophistication and holistic integration (Wang et al. 2019; Ilgun Dibek et al. 2024).

To elucidate the multi-dimensional structure of HOT, scholars have examined its constituent elements from diverse disciplinary perspectives. Discipline-specific definitions have emerged as a primary research approach. Table 1 summarizes the core dimensional classifications of HOT in representative studies across disciplines.

Table 1.

Core Dimensions of Higher-Order Thinking Across Disciplines.

Although the specific classifications of HOT vary across disciplinary contexts, there is widespread agreement that its core components comprise critical thinking, creative thinking, and problem-solving ability-a consensus supported by cross-disciplinary studies (Yang 2015; Hwang et al. 2018; Alkhatib 2022). These three dimensions manifest distinct domain-specific characteristics and are the most frequently activated cognitive processes in twenty-first-century skills. King et al. (1998) early on highlighted that HOT is not isolated cognitive behavior but a dynamic, coordinated system of cognitive skills. When confronted with complex problem-solving situations, these skills are activated synergistically: critical thinking enables the analysis and evaluation of information and rapid identification of problem essence (Li et al. 2024b; Liu et al. 2024a); creative thinking facilitates the exploration of novel approaches and generation of diverse solutions (Li et al. 2024b; Pujawan et al. 2022); and problem-solving ability is responsible for constructing and implementing effective strategies (Li et al. 2024b; Adijaya et al. 2023). The integrated and contextually adaptive nature of these multidimensional capacities constitutes a defining feature that distinguishes HOT from lower-order cognitive processes.

2.2. The Positive Impact of Gen-AI on the Cultivation of HOT

Currently, research on the relationship between Gen-AI and students’ HOT development presents a diversity of theoretical perspectives. Although preliminary empirical studies have highlighted the potential value of Gen-AI in educational applications, significant debate remains regarding its functional positioning and actual effectiveness within instructional systems.

Empirical evidence provides strong support for these claims. Costa et al. (2024) found that students who completed integrative learning tasks with the assistance of ChatGPT demonstrated significant improvements in higher-order cognitive abilities, particularly in text comprehension and critical thinking. In the context of interdisciplinary instruction, Lee et al. (2024) developed and validated a Gen-AI-based “Guided Chemistry Learning Assistant” (GCLA). By simulating expert-guided strategies, this tool effectively enhanced students’ critical thinking, multi-step problem-solving skills, and innovative application in chemistry. Furthermore, Li et al. (2024b) conducted experimental research using InquiryGPT, providing additional evidence that Gen-AI can facilitate HOT development. The study demonstrated that the tool, through a structured inquiry-based learning framework, effectively strengthened students’ systematic reasoning and metacognitive skills, offering empirical support for the role of Gen-AI in promoting HOT.

From the perspectives of cognitive and learning sciences, scholars have systematically examined the mechanisms through which Gen-AI influences the core dimensions of HOT—namely critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving ability-focusing on its instructional applications and cognitive empowerment pathways.

2.2.1. Critical Thinking

Research indicates that Gen-AI, leveraging its high interactivity and scaffolded learning features, can effectively foster students’ critical thinking. Guo et al. (2023) found that embedding AI chatbots in high school debate activities significantly enhanced students’ critical thinking, particularly in argument construction and evidence evaluation. Zheng et al. (2024) further reported that in collaborative learning environments, students strengthened their evaluative and reflective abilities by filtering and questioning AI-generated content and verifying information reliability. Bailey et al. (2021), drawing on cognitive development stage theory, emphasized that AI-generated prompts play a key role in guiding novice learners into critical reasoning processes.

2.2.2. Creativity

In the domain of creativity, Gen-AI extends both learning experiences and cognitive possibilities beyond traditional instructional frameworks. Compared with teacher-led question-and-answer modes, Gen-AI requires students to construct queries to obtain targeted feedback actively, thereby cultivating initiative in knowledge exploration and divergent thinking (Alzubi et al. 2025). By providing personalized support, real-time responsiveness, and multimodal content generation, Gen-AI offers a novel technological pathway for stimulating creativity. Huang et al. (2024a) integrated AI-generated content (AIGC) into educational product design to enhance students’ HOT, demonstrating that AIGC can effectively guide learners through advanced cognitive processes such as analogical reasoning and conceptual restructuring. Moreover, by offering open-ended and heuristic feedback, Gen-AI fosters a risk-tolerant and exploratory learning environment, further promoting the development of creative thinking.

2.2.3. Problem-Solving Ability

Regarding problem-solving ability, Gen-AI primarily supports students’ development of systematic problem-solving skills through mechanisms such as multi-path solution provision, response evaluation, and iterative feedback. Sun et al. (2024) found that ChatGPT not only offers alternative problem-solving strategies but also assists students in validating and optimizing solutions, significantly improving problem-solving efficiency and quality. Xu et al. (2024) introduced AI-based chatbots to facilitate gamified learning in information technology courses, demonstrating that such tools support the development of adaptive problem-solving skills in dynamic contexts. Additionally, Cam and Kiyici (2022) reported that AI-assisted learning environments in robotics programming effectively enhance students’ computational thinking and complex problem decomposition abilities, further consolidating the positive impact of Gen-AI in this domain.

2.3. Potential Risks and Challenges of Gen-AI in Fostering HOT

Although Gen-AI demonstrates considerable potential in fostering HOT skills, some scholars adopt a more cautious stance toward its application in education, emphasizing that without the guidance of sound pedagogical principles, its use may pose risks to students’ cognitive development. Several studies have underscored the limitations of Gen-AI’s actual effectiveness, noting that its impact is highly contingent on specific learning contexts and, in some instances, may even hinder the development of critical thinking and creativity.

Lu et al. (2024) reported that, under certain conditions, the use of Gen-AI exerted adverse effects on students’ HOT skills, suggesting that its integration does not always yield the anticipated cognitive benefits and may, in fact, impede intellectual growth. Similarly, Sun et al. (2024), in the context of programming education, observed that students often relied on ChatGPT-generated code without engaging in debugging or analysis. Such reliance not only weakened their problem-solving abilities but also reduced their depth of understanding of programming concepts. In a related vein, Putra et al. (2023) noted that students frequently accepted AI-generated content uncritically, lacking awareness of the need to question and verify its reliability and accuracy. This dependence risks further constraining the development of critical thinking and creative problem-solving abilities.

In addition, research by Kooli (2023) and Maniktala et al. (2023) has suggested that frequent reliance on Gen-AI-based dialogs may negatively impact students’ academic autonomy and capacity for knowledge internalization, fostering cognitive dependence and diminishing their ability to solve problems independently. Notably, Maniktala et al. (2023) also found that, in specific problem-solving tasks, university students who refrained from using Gen-AI outperformed their peers who did, further highlighting the dual-edged nature and potential risks of Gen-AI in educational applications. Therefore, it is imperative to strategically leverage moderating variables to mitigate these risks and ensure that Gen-AI actively contributes to the development of students’ HOT.

2.4. Potential Moderators

Empirical evidence indicates that the impact of Gen-AI on the development of learners’ HOT skills is highly context-dependent and conditional. Its facilitative effects are neither linear nor universally consistent but are instead constrained by multiple moderating factors. Zhou et al. (2024) identified self-regulated learning (SRL) as a critical mediating variable linking Gen-AI use to the enhancement of critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Ex-tending this line of inquiry, Xu et al. (2024) found that learners with weaker SRL capacities tend to rely more heavily on immediate feedback and external assistance, exhibiting tendencies toward unstructured inquiry and spontaneous dialog. These findings underscore the central role of individual differences in shaping Gen-AI–driven learning trajectories and outcomes, while simultaneously revealing potential educational challenges.

Beyond individual differences, temporal and group-level variations also influence how Gen-AI affects HOT development. Li et al. (2024a) and Li and Wang (2023) reported that the duration of Gen-AI use significantly conditions its impact on HOT, highlighting the importance of considering intervention length and continuity in instructional design. Similarly, Zhang and Zhu (2022) demonstrated that the effects of AI-driven conversational tools on creativity vary substantially across educational levels. Learners’ age also moderates the relationship between Gen-AI and the development of HOT. Owing to differences in cognitive structures and developmental needs across age groups, learners interact with AI in fundamentally distinct ways. These variations in interaction patterns directly shape the pathways through which Gen-AI facilitates HOT, as well as the magnitude of its eventual effects (Larson et al. 2024; Zhao et al. 2025).

In addition, instructional approaches critically shape the extent to which Gen-AI supports higher-order learning. Kimmel (2024) argued that embedding Gen-AI within project-based learning (PBL) environments can foster creative problem posing, integrative knowledge synthesis, and iterative design. Complementarily, the empirical study by Gonsalves (2024) found that in Socratic inquiry-based teaching, limiting the functions of Gen-AI to proposing counterexamples, challenging assumptions, and identifying weak evidence can significantly enhance learners’ metacognitive reflection and critical thinking skills.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the effectiveness of Gen-AI in fostering HOT is contingent upon a constellation of contextual and individual factors, underscoring the need for nuanced and context-sensitive strategies in both research and practice. At the same time, the conditional nature of its effects highlights the potential risks and challenges associated with unguided or poorly structured integration of Gen-AI into educational settings.

2.5. Related Reviews and Meta-Analyses on the Impact of Gen- AI on HOT

To date, several scholars have employed meta-analytic approaches to examine the impact of Gen-AI on learners, with most studies focusing on outcomes such as academic performance, learning engagement, and learning development (Deng et al. 2025; Wang and Fan 2025; Heung and Chiu 2025). Although HOT is occasionally mentioned in these discussions, the outcome variables are not differentiated based on cognitive levels, nor are HOT skills specifically assessed.

Furthermore, although several literature reviews have attempted to synthesize evidence on the effectiveness of AI in educational contexts (e.g., Zawacki-Richter et al. 2019), recent meta-analyses (García-Martínez et al. 2023) in this domain exhibit notable limitations in their scope and coverage. Most of the literature reviewed was collected up to the end of 2024. For instance, Zheng et al. (2023) consolidated research from the past two decades on the impact of AI technologies on learning outcomes and learner cognition, while Hwang (2022) focused specifically on the effects of AI agents on elementary students’ mathematics achievement. Although Ilgun Dibek et al. (2024) systematically reviewed the influence of AI tools on HOT, their analysis was limited to literature published up to 2023, emphasized general AI tools, and did not specifically incorporate studies related to Gen-AI. Collectively, these studies fail to capture the most recent empirical evidence emerging from the rapid advancements in Gen-AI.

As a core cognitive competency of the twenty-first century, HOT warrants more dedicated and in-depth research attention, particularly in the context of Gen-AI’s increasing integration into educational environments. Therefore, a systematic review and synthesis of existing empirical studies on the impact of Gen-AI on learners’ HOT is both timely and necessary. Such research not only helps to distinguish HOT from other learning outcomes clearly but also elucidates the underlying mechanisms through which Gen-AI influences HOT and identifies potential moderating factors, thereby providing theoretical grounding for the effective and targeted application of Gen-AI in education.

2.6. The Present Study

In light of the inconsistencies observed in prior research, this study employs a meta-analysis approach, synthesizing data from 59 experiments and quasi-experiments reported across 29 sources. The primary objective is to ascertain both the direction and magnitude of Gen-AI’s impact on students’ HOT. Guided by this objective, the meta-analysis seeks to address the following core research questions:

- Q1. What is the overall effect size of Gen-AI on students’ HOT? Separately, what are the effect sizes of Gen-AI on the three levels of HOT (critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving skills)?

- Q2. Do moderating variables—such as intervention duration, educational level, instructional method, and self-regulated learning ability—impact the relationship between Gen-AI and the development of HOT? If so, how do they moderate the effect of Gen-AI on students’ HOT?

3. Methods

This study employs a meta-analysis approach to systematically synthesize existing empirical research on the impact of Gen-AI on students’ HOT. Further analyses were carried out using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) 3.7. This study adopts Hedges’s g as the effect size measure. The interpretation of effect sizes follows Cohen’s (1992) guidelines: values below 0.2 indicate a small effect, values between 0.2 and 0.5 represent a moderate effect, values between 0.5 and 0.8 suggest a significant effect, and values exceeding 0.8 denote a largely significant effect.

3.1. Data Sources and Search Strategies

To ensure a comprehensive and systematic collection of relevant research, this study conducted a structured literature search across multiple academic databases, including Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, Springer, Google Scholar, China Online Journals, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). The search terms included generative artificial intelligence, Gen-AI, ChatGPT, chatbot, higher-order thinking, HOT skills, creativity, creative thinking, critical thinking, problem solving, and problem-solving ability. Boolean operators “OR” and “AND” were used to refine the search, allowing for broad keyword matching and citation tracking. Additionally, a snowballing search strategy was employed, wherein references cited in the selected papers were further examined to enrich the dataset. Given that Gen-AI had not been widely applied before the release of ChatGPT in November 2022, this study includes only literature published after this date, in which the search ended in August 2025.

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

As a result, 400 relevant studies were initially identified. However, not all retrieved studies met the eligibility criteria for meta-analysis. Except for excluding gray literature, the following selection criteria were applied: (1) Repetitive articles should be excluded. (2) The research topic must analyze the correlation between Gen-AI and HOT (e.g., critical thinking, creativity, problem-solving). (3) The research method must be experimental or quasi-experimental. (4) It must possess sufficient quantitative data for statistical analysis, such as data like means and standard deviations. (5) The articles must be publicly published or accessible. (6) The articles must be in English or Chinese.

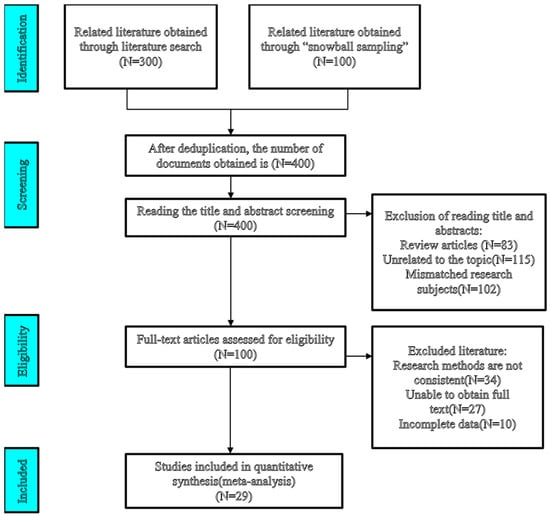

Following these selection criteria, a total of 29 studies, comprising 59 effect sizes, met the inclusion criteria and were retained for subsequent meta-analysis. The process of literature screening is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study search and selection process.

3.3. Literature Coding

To ensure coding reliability, two researchers independently conducted the coding process. First, the primary author performed the initial coding, followed by a secondary researcher who reviewed and validated the coded data, documenting the review date. Inter-coder reliability was assessed using Cohen’s k, which yielded a value of 0.84, indicating excellent agreement beyond chance. Any discrepancies in coding were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. The coding framework included the following dimensions: Descriptive information (author(s), and year of publication); Quantitative data (sample size, mean values, and standard deviations); Assessment dimensions (creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills), and Moderator variables. The detailed coding specifications for the moderator variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Code of moderator.

3.4. Publication Bias Test

Publication bias refers to the tendency for published studies to be preferentially included in literature reviews or meta-analyses, while unpublished studies—often with null or non-significant results—are overlooked. This can inflate the overall effect size and compromise the validity of the meta-analytic conclusions. To assess the presence of publication bias in the current study, we employed both funnel plot analysis and Egger’s regression test (Peters et al. 2008; Van der Willik et al. 2021).

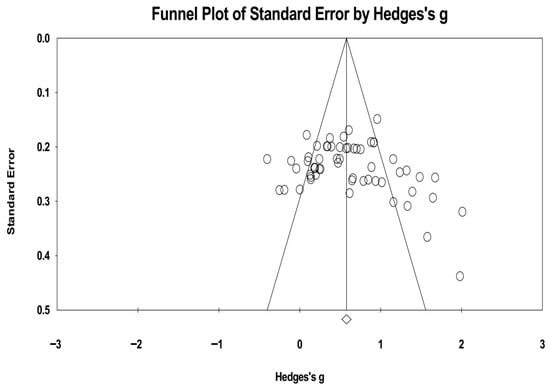

The assessment of publication bias revealed no strong evidence of severe distortion in the current meta-analysis. The funnel plot constructed from the 29 included studies showed that a total of 8 individual data points fell outside the slope lines, but a generally symmetrical distribution of data points around the mean effect size was observed (see Figure 2). However, visual inspection suggested a possible slight skew to the right, which corresponds with the findings of Egger’s test.

Figure 2.

Funnel plot of standard error by Hedges’s g.

To corroborate this visual assessment, Egger’s regression test was performed. The test produced a t-value of 1.871 with a corresponding p-value of 0.066, which approached but did not reach the threshold for statistical significance (t < 1.96, p > 0.05). This finding could indicate mild publication bias. Taken together, these results indicate that the meta-analytic findings are unlikely to be significantly affected by publication bias, thereby enhancing the robustness and credibility of the study’s conclusions.

3.5. Heterogeneity Test

In meta-analyses, heterogeneity may arise due to differences in study design, sample characteristics, and measurement approaches among the included studies. Such variability in effect sizes can result from random sampling errors or systematic differences across study groups. Therefore, it is essential to assess and quantify heterogeneity using appropriate statistical methods.

In the present study, heterogeneity was evaluated using Cochran’s Q test and the I2 statistic. Cochran’s Q test is used to determine whether the variability in effect sizes across studies is greater than would be expected by chance. Conventionally, a non-significant Q value (p > 0.1) indicates low heterogeneity, suggesting that a fixed-effects model may be appropriate, whereas a significant Q value (p < 0.1) suggests that heterogeneity is present and that a random-effects model should be considered (Zhang and Hu 2019). To further quantify the extent of heterogeneity, the I² statistic is used. It ranges from 0% to 100%, with values below 25% typically regarded as low, between 25% and 50% as moderate, and above 75% as high (Higgins et al. 2003).

The analysis revealed significant heterogeneity among the included studies, as indicated by the Q statistic (Q = 255.208, p < 0.001; see Table 3). The I2 value was 77.273%, suggesting a moderate level of heterogeneity across studies. Accordingly, a random-effects model was employed to yield a more robust and generalizable estimation of the overall effect size.

Table 3.

Heterogeneity test results.

4. Results

4.1. The Analysis of the Overall Effect Size

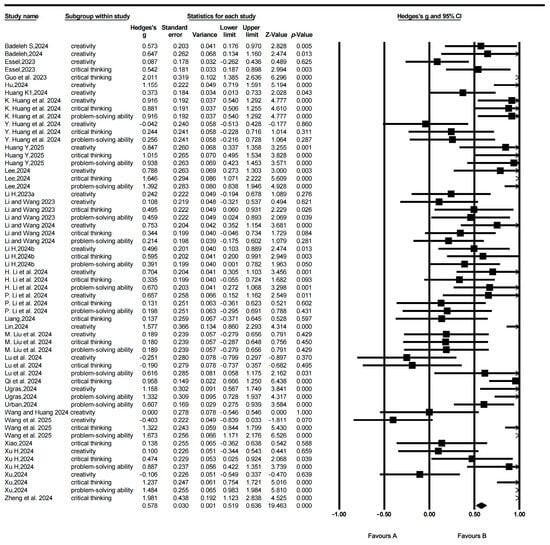

Based on established methodological practices, a random-effects model was employed in this study to account for heterogeneity among the included studies. Hedges’s g was selected as the measure of effect size to assess the impact of Gen-AI on students’ HOT. As presented in Table 3, the analysis yielded an overall effect size of 0.609, indicating that Gen-AI has a moderately significant and statistically meaningful impact on students’ HOT abilities. In other words, the findings support the conclusion that Gen-AI is effective in enhancing students’ HOT skills. The effect forest plot is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Forest plot.

This study further examined the effects of Gen-AI on the three core dimensions of students’ HOT: creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving, as presented in Table 4. The findings indicate that Gen-AI had the most pronounced impact on students’ problem-solving ability, with an effect size (ES) of 0.745, which falls within the moderately significant range (0.5 ≤ ES < 0.8) and is statistically significant (p < 0.001). This suggests that Gen-AI exerts a substantial positive influence on enhancing students’ problem-solving skills.

Table 4.

Test results for the effect of Gen-AI on three dimensions of HOT.

The second highest effect was observed in the domain of critical thinking, with an effect size of 0.691, which is also statistically significant (p < 0.001). This result highlights the constructive role of Gen-AI in fostering students’ critical thinking abilities.

Lastly, the effect size for creativity was 0.444, which, while lower than the other two dimensions, still represents a moderate and statistically significant effect (p < 0.001). This indicates that Gen-AI contributes positively to the development of students’ creative thinking, albeit to a lesser extent compared to problem-solving and critical thinking.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that Gen-AI exerts significant positive effects across all three core dimensions of HOT, with the most substantial impact observed on problem-solving, followed by critical thinking, and a moderate yet meaningful impact on creativity.

4.2. The Analysis of Moderator Effect Size

This study further examined the moderating effects of four potential moderator variables—intervention duration, education level, instructional method, and self-regulated learning (SRL) ability—on the relationship between Gen-AI and students’ HOT. The results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Tests of the moderating effect.

4.2.1. Intervention Duration

When intervention duration was examined as a moderating variable, a significant between-groups difference was observed (Q = 9.106, p = 0.011), indicating that the length of intervention significantly moderated the effectiveness of Gen-AI on students’ HOT. Subgroup analyses revealed that interventions lasting 0–8 weeks yielded a moderate effect (ES = 0.494, p < 0.001), interventions of 8–16 weeks produced the most significant effect (ES = 0.759, p < 0.001), and interventions exceeding 16 weeks showed a comparatively more minor effect (ES = 0.372, p < 0.001). These results demonstrate that the impact of Gen-AI on HOT varies substantially across different intervention durations, with the 8–16 weeks window generating the most pronounced benefits.

4.2.2. Educational Level

When educational level as a moderating variable indicated that the between-groups difference did not reach statistical significance (Q = 3.353, p = 0.067), suggesting that educational level did not constitute a statistically significant moderator in the relationship between Gen-AI and students’ HOT. Nevertheless, examination of the subgroup effect sizes revealed practically meaningful differences between K-12 and higher education contexts. Specifically, K-12 reflecting a highly significant large effect (ES = 0.857, p < 0.001), whereas higher education corresponding to a moderate effect (ES = 0.593, p < 0.001). These results imply potential differences in responsiveness or instructional context that merit further investigation.

4.2.3. Instructional Method

The meta-analysis revealed that instructional methods did not exert a statistically significant moderating effect at the between-groups level (Q = 2.918, p = 0.232). This indicates that, overall, the moderating role of pedagogy did not reach statistical significance. Nevertheless, subgroup analyses uncovered meaningful heterogeneity across different instructional strategies. Specifically, project-based learning yielded a moderately significant effect (ES = 0.717, p < 0.001), blended learning produced a moderate effect (ES = 0.525, p < 0.001), while lecture-based instruction yielded a small, non-significant effect (ES = 0.396). These results suggest that in traditional lecture-centered contexts, the potential of Gen-AI to foster students’ HOT remains comparatively constrained.

4.2.4. Self-Regulated Learning Ability

The final analysis revealed that SRL exerted a significant moderating effect on the relationship between Gen-AI and students’ HOT (Q = 40.962, p < 0.001). Subsequent subgroup analyses indicated marked differences in the effects of Gen-AI interventions across varying levels of SRL. Specifically, students with high SRL demonstrated a substantial positive effect (ES = 0.863, p < 0.001), whereas those with low SRL exhibited only a small to moderate effect (ES = 0.284, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that SRL constitutes a critical boundary condition shaping the educational impact of Gen-AI. The facilitative role of Gen-AI is particularly pronounced for students with strong SRL capacities, while its benefits appear comparatively limited for students with weaker SRL skills.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Effectiveness of Gen-AI on Students’ HOT

The results of this meta-analysis indicate that Gen-AI exerts a significant positive effect on students’ HOTS. The overall effect size (Hedges’s g = 0.609) represents a moderately large and statistically significant improvement, suggesting that Gen-AI plays a substantive role in supporting the development of HOTS and can serve as an effective tool for fostering students’ higher-order cognitive abilities. These findings are consistent with previous studies (Lee et al. 2024; Li et al. 2024b; Huang et al. 2024b; Ilgun Dibek et al. 2024), which collectively demonstrate that Gen-AI can function as a cognitive scaffold, provide guided prompts rather than direct answers, and create a learning environment conducive to the cultivation of HOTS. Specifically, Lee et al. (2024) developed a guidance-based ChatGPT-assisted learning tool that directs students through prompts to enhance reflective engagement, while Li and Huang further showed that teacher-mediated discussion and reflection on AI-generated feedback significantly support students’ HOT. In addition, Lu et al., using survey data from university students and structural equation modeling, found that both Gen-AI usage and evaluation directly influenced HOT, and also indirectly facilitated HOT development through behavioral engagement and peer interaction. Overall, these empirical results align with existing theoretical perspectives suggesting that technology-enhanced learning environments can provide dynamic, adaptive, and context-sensitive resources to scaffold complex cognitive processes (Bower and Vlachopoulos 2018).

At the same time, some studies have raised concerns regarding students’ overreliance on Gen-AI. Iskender (2023) and Johinke et al. (2023) reported that in writing courses, students may rely on AI not only for language refinement but also for idea generation, which could potentially undermine the development of HOT. Writing inherently integrates creative and critical processes across stages such as idea generation, argumentation, revision, and reflection; bypassing these essential processes reduces opportunities for independent reasoning and evaluative judgment. Moreover, the formulaic and homogenizing tendencies of AI-generated content may encourage “shortcut learning,” limiting originality and divergent thinking. These findings highlight the importance of discipline-sensitive instructional design: although Gen-AI holds substantial potential for enhancing HOTS, its pedagogical application must be carefully balanced. Instructional strategies should be deliberately structured—for example, by encouraging reflection, discussion, and phased use of Gen-AI—to maximize its benefits for HOT while minimizing potential adverse effects.

The analysis further revealed differential effects across the three core dimensions of HOT: problem-solving, critical thinking, and creativity. Gen-AI demonstrated the most substantial impact on problem-solving ability and critical thinking, while its effect on creativity, although positive, was relatively lower. These findings align with those reported by Lee et al. (2024), Huang et al. (2024b), and Xu et al. (2024). Specifically, Gen-AI can serve as a cognitive scaffold that guides learners through a structured process of problem identification, analysis, and resolution during interaction (Li and Wang 2023). Moreover, the real-time feedback and intelligent recommendation mechanisms embedded in Gen-AI tools can enhance learners’ metacognitive engagement during problem-solving, reduce cognitive interruptions, and promote deeper cognitive processing (Li and Wang 2024).

At the same time, the inherent limitations of Gen-AI, such as AI hallucinations, may catalyze critical thinking. The generation of inaccurate or misleading information compels students to scrutinize the validity and reliability of the outputs, thereby reinforcing their critical evaluation skills, reducing their reliance on Gen-AI, and increasing the likelihood of meaningful interactions with Gen-AI (Qi et al. 2024; Hou et al. 2025).

Although the short-term impact of Gen-AI on creativity appears to be relatively limited, its long-term potential may be significantly enhanced through systematic and intentional instructional design. First, educators can embed Gen-AI into extended, scaffolded creative tasks, encouraging students to use the tool across different stages of ideation, revision, and refinement. Such a progressive task structure provides the temporal and cognitive space necessary for iterative practice, gradually fostering creative competencies. Second, the trial-and-error process is essential for creative development. Creativity thrives in supportive, low-risk learning environments where students feel empowered to explore, experiment, and even fail. Gen-AI can facilitate this process by offering simulated environments, generating alternative ideas, or conducting data-based analysis, thus enabling students to innovate and test hypotheses with minimal risk. Through iterative experimentation and reflection, students can accumulate experiential knowledge and explore optimal creative solutions, leading to sustained development in creativity. Furthermore, Gen-AI does not directly enhance learners’ creativity but does so through mediating factors such as collective efficacy, making a collaborative environment built on mutual trust essential (Luo et al. 2025).

5.2. The Moderating Effects of Gen-AI on Students’ HOT

5.2.1. Intervention Duration

The results indicate that the application of Gen-AI produced moderate effect sizes on students’ HOT when the intervention period lasted 1–8 weeks and 8–16 weeks, with the latter yielding more pronounced effects. This pattern appears to be closely related to students’ acceptance of Gen-AI and the psychological adaptation processes they undergo over time.

In shorter interventions (1–8 weeks), students may not have fully adapted to or mastered the use of Gen-AI as a novel educational support tool, limiting its effectiveness in facilitating HOT skills (Ganesh et al. 2022). The abbreviated exposure also restricts opportunities for in-depth exploration of the technology’s potential, thereby weakening its impact on cognitive development.

In contrast, interventions exceeding 16 weeks may lead to diminishing returns, as prolonged exposure to Gen-AI tends to foster over-reliance among students. This dependence manifests in passive acceptance of AI-generated content without critical examination and a preference for efficiency over deep, self-driven inquiry when tackling complex tasks (Du et al. 2025). Consequently, learners’ intrinsic motivation gradually erodes, diminishing their sense of autonomy and sustained engagement in the cognitive process (Wang et al. 2025). These adverse effects can attenuate the initial cognitive benefits, ultimately impeding the development of HOT.

An inverted U-shaped relationship emerges between intervention duration and effectiveness: both short-term (1–8 weeks) and long-term (over 16 weeks) interventions yield relatively limited effects, whereas the 8–16-week intermediate duration demonstrates optimal outcomes. This pattern suggests that the mid-length intervention strikes a balance, allowing students adequate time to build proficiency in using Gen-AI while avoiding the negative consequences of extended use.

To mitigate the risks associated with long-term AI integration, some pedagogical strategies are recommended. First, a phased scaffolding should be adopted, whereby AI support is systematically faded to encourage the gradual development of independent problem-solving skills (Wang et al. 2025). Second, guided Gen-AI interaction should be implemented, using carefully designed prompts to steer AI toward providing conceptual frameworks or reasoning processes rather than direct answers, thereby fostering sustained active participation and deeper cognitive engagement (Lee et al. 2024).

5.2.2. Education Level

The results indicate that the educational stage does not serve as a significant moderating variable; however, the impact of Gen-AI varies across different educational stages. The analysis reveals that Gen-AI exerts a stronger influence on K-12 students than on university students. This discrepancy may stem from differences in usage patterns and instructional guidance across education levels.

In higher education, students tend to rely on Gen-AI primarily for text generation and information retrieval, often engaging in superficial interactions or delegating intellectual tasks to the technology—a phenomenon referred to as “knowledge outsourcing” (Li et al. 2024c). Many college students pose low-level questions to Gen-AI for tasks such as assignments, translations, and essay writing. Prior studies (Liu et al. 2024b) have shown that some students plagiarize AIGC, which hinders the development of deep learning and critical thinking. Similarly, in programming tasks, students often copy and paste faulty Gen-AI-generated code without verification, reflecting a lack of reflective engagement (Sun et al. 2024).

In contrast, K-12 students are more likely to use Gen-AI as a guided learning tool under teacher supervision. They employ Gen-AI in exploratory learning and problem-solving, suggesting that appropriate instructional scaffolding is critical to ensuring productive use. As Shi and Han (2024) have pointed out, in the absence of teacher guidance, students’ excessive reliance on AI-generated content may undermine their critical thinking skills and autonomy.

Regardless of the educational stage in which Gen-AI is applied, teachers play a pivotal role as facilitators of student learning. In classroom settings, their ability to strategically leverage Gen-AI technologies is essential for fostering HOT. Therefore, it is recommended that educators receive targeted professional development on how to integrate Gen-AI tools effectively into instructional design, ensuring that technological affordances are aligned with pedagogical goals to maximize cognitive engagement and thinking depth.

5.2.3. Instructional Method

Although the overall moderating effect of the instructional method was not statistically significant, substantial differences were observed in the effect sizes across pedagogical approaches. Notably, the combination of project-based learning (PBL) with Gen-AI yielded the most positive outcomes. This aligns with findings by Shahzad et al. (2024), who demonstrated that the integration of Gen-AI significantly enhances the effectiveness of PBL and supports the development of student creativity.

PBL emphasizes learner-centered, inquiry-driven activities, where students engage in real-world projects to construct knowledge (Kimberly 2023). In this context, Gen-AI acts as a valuable cognitive partner, offering diverse resources and perspectives, and enabling students to explore and solve complex problems autonomously (Khan et al. 2023).

In contrast, blended learning outcomes depend heavily on students’ self-regulation and digital literacy. Learners with low adaptability or limited support may misuse Gen-AI, leading to unstructured engagement and reduced learning quality. This is consistent with Means et al. (2013), who noted that less adaptive learners often struggle in blended environments.

Under lecture-based instruction, students typically engage in passive learning, relying on teacher-led knowledge transmission. Gen-AI is often relegated to a peripheral role as a supplementary information source, with limited impact on students’ active engagement or cognitive transformation.

In light of these findings, educators are encouraged to expand the use of PBL and provide structured guidance on Gen-AI integration. Furthermore, educators should place greater emphasis on instructional design and the deliberate selection of pedagogical approaches. Instructional planning should be informed by a careful analysis of learner characteristics, enabling the design of targeted learning activities and provision of appropriate resources to meet students’ needs in AI-enhanced environments (Chiu et al. 2023). By scaffolding students’ engagement with Gen-AI tools for self-directed inquiry and problem-solving, educators can better leverage the affordances of Gen-AI to support the development of HOT skills.

5.2.4. Self-Regulated Learning Ability

Self-regulated learning (SRL) plays a critical role in enabling students to establish learning goals, select appropriate strategies, and monitor their cognitive processes, thereby laying a foundational framework for the development of HOT. As emphasized by Wang and Liu (2024), students’ SRL capabilities may directly and significantly enhance their HOT competencies. Conversely, engagement in HOT tasks, such as analyzing complex problems, constructing reasoned arguments, or evaluating evidence, requires continuous goal-setting, strategic planning, and metacognitive reflection. This dynamic process, in turn, reinforces and further develops students’ self-regulatory abilities.

This study, through empirical analysis, confirms that SRL exerts a significant moderating effect on the relationship between Gen-AI and HOT skills. This finding resonates with the results of Xu et al. (2024), Rusandi et al. (2023), and Wang and Huang (2024), further reinforcing the notion that SRL, as a critical individual difference variable, plays a central role in determining whether external intelligent tools can be effectively leveraged to promote learners’ cognitive development (Xu et al. 2024; Rusandi et al. 2023). Specifically, Wang and Huang (2024) emphasizes that SRL functions as a “key regulatory mechanism” that can effectively “neutralize” the potential cognitive risks associated with the use of Gen-AI in fostering HOT.

The results indicate that students with higher levels of SRL are capable of proactively planning their learning trajectories rather than passively relying on or directly replicating Gen-AI–generated outputs. Such students tend to critically reflect on the generated content, seeking to integrate it with their existing knowledge structures rather than adopting it uncritically (Zhou et al. 2024; Borge et al. 2024). Moreover, students with high SRL demonstrate a heightened capacity to recognize the educational value of Gen-AI tools, actively incorporating them into their learning processes. By employing critical thinking and evaluative skills, they can extract valuable information, thereby enhancing problem-solving abilities and fostering creative thinking.

In contrast, students with lower levels of SRL often struggle to assess the accuracy and relevance of AI-generated content, making them more susceptible to uncritically accepting information, including errors or misleading outputs (Xu et al. 2024). They also face difficulties in aligning Gen-AI tools with their learning objectives and lack the flexibility to adapt strategies when confronted with challenges (Wang and Huang 2024). Consequently, their use of intelligent tools remains inefficient, hindering their engagement in effective knowledge construction.

Taken together, these findings underscore the pressing need for educational practice to prioritize and systematically strengthen students’ SRL capacities. By designing targeted instructional interventions and adopting tiered strategies for Gen-AI integration, educators can support the development of adaptive learning behaviors. In particular, fostering students’ metacognitive awareness, strategic planning, and reflective learning practices can enhance their ability to critically and autonomously engage with Gen-AI. Ultimately, such efforts can maximize the educational potential of Gen-AI in advancing HOT skills.

6. Conclusions and Limitations

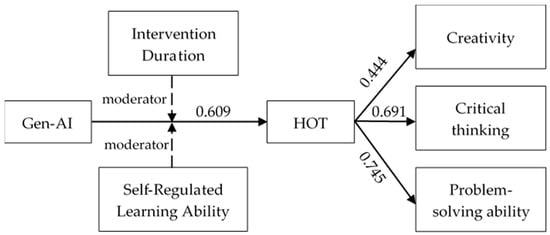

The present meta-analysis reveals that Gen-AI exerts a moderate positive influence on the development of students’ HOT, with a moderately significant positive impact on problem-solving ability and critical thinking, yet a relatively more minor effect on creativity. However, its effectiveness is significantly moderated by factors such as intervention duration and students’ self-regulated learning abilities (see Figure 4). Specifically, the impact of Gen-AI is most pronounced when the intervention lasts between 8 and 16 weeks, whereas interventions shorter or longer than this duration yield comparatively weaker effects. Moreover, students with higher self-regulated learning abilities benefit more substantially from Gen-AI than those with lower self-regulation skills, underscoring the critical role of learner agency in technology-enhanced learning environments. These findings underscore the importance of tailoring Gen-AI implementation to intervention duration and learner differences, notably SRL. This study offers theoretical and practical guidance for integrating Gen-AI, highlighting its potential to foster HOT, a core component of innovation.

Figure 4.

Model of findings.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations that warrant further exploration. First, the scope and diversity of the sample and research designs limit the generalizability of the findings. The inclusion of a relatively narrow range of educational contexts and learner populations may restrict the external validity of the results. Moreover, this meta-analysis was limited to studies published in Chinese and English. Such a language restriction could introduce potential bias by omitting literature in other linguistic contexts, which in turn undermines the generalizability of the findings. Future investigations ought to encompass more diverse educational contexts and student populations to enhance the robustness and applicability of the conclusions, while employing more inclusive methodologies to cover a wider spectrum of research literature.

Second, the study may not fully capture the rapidly evolving nature of Gen-AI technologies and their expanding roles in educational practice. The current meta-analysis is based on existing literature, which may lag behind the most recent developments and emerging applications. To address this, future studies should employ longitudinal designs, cross-cultural comparisons, and multi-dimensional analytical models and incorporate broader dimensions of HOT (e.g., decision-making and evaluation) to understand better the complex and dynamic effects of Gen-AI on HOT. Such approaches will provide more nuanced and context-sensitive insights, thereby offering more targeted guidance for the integration of Gen-AI in educational practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z., Y.Y., Q.J. and G.L.; methodology, Q.J. and G.L.; formal analysis, Q.J. and G.L.; literature cording, Y.Z. and Y.Y.; literature search, Y.Y.; data analysis, Y.Z. and Y.Y.; writing—original draft, Y.Z. and Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z., Y.Y., Z.S., Q.J. and G.L.; supervision, Z.S. and G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Planning Project for Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education, grant number 23YJA880023; and the Jilin Province Educational Science Project, grant number GH25412; and the Project of the Jilin Provincial Higher Education Society, grant number JGJX2025C107; and the Social Science Foundation Projects of CCNU, grant number CSJJ2022019SK; and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) grant number 62577018.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Readers can request the data from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Gen-AI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| HOT | Higher-order Thinking |

| SRL | Self-regulated Learning |

| PBL | Project-based Learning |

References

- Adijaya, Made Aryawan, I Wayan Widiana, I Gusti Lanang Agung Parwata, and I Gede Wahyu Suwela Antara. 2023. Bloom’s taxonomy revision-oriented learning activities to improve procedural capabilities and learning outcomes. International Journal of Educational Methodology 9: 261–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhatib, Omar J. 2022. An Effective Assessment Method of Higher-Order Thinking Skills (Problem-Solving, Critical Thinking, Creative Thinking, and Decision-Making) in Engineering and Humanities. Paper presented at 2022 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, February 21–24; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubi, Ali Abbas Falah, Mohd Nazim, and Naji Alyami. 2025. Do AI-generative tools kill or nurture creativity in EFL teaching and learning? Education and Information Technologies 30: 15147–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Lorin W., and David R. Krathwohl. 2001. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Complete Edition. Albany: Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. Available online: http://eduq.info/xmlui/handle/11515/18824 (accessed on 6 November 2015).

- Arista, Artika, Liyana Shuib, and Maizatul Akmar Ismail. 2023. A glimpse of ChatGPT: An introduction to features, challenges, and threats in higher education. Paper presented at Informatics, Multimedia, Cyber and Information Systems Conference, Jakarta Selatan, Indonesia, November 7–8; pp. 694–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Daniel, Norah Almusharraf, and Ryan Hatcher. 2021. Finding satisfaction: Intrinsic motivation for synchronous and asynchronous communication in the online language learning context. Education and Information Technologies 26: 2563–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, Benjamin S. 1956. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. Boynton Beach: Susan Fauer Company. [Google Scholar]

- Borge, M., B. K. Smith, and T. Aldemir. 2024. Using generative AI as a simulation to support higher-order thinking. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning 19: 479–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, Matt, and Panos Vlachopoulos. 2018. A critical analysis of technology—Enhanced learning design frameworks. British Journal of Educational Technology 49: 981–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cam, Emre, and Mübin Kiyici. 2022. The impact of robotics-assisted programming education on academic success, problem-solving skills, and motivation. Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning 5: 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Thomas K. F., Benjamin Luke Moorhouse, Ching Sing Chai, and Murod Ismailov. 2023. Teacher support and student motivation to learn with Artificial Intelligence (AI) based chatbot. Interactive Learning Environments 32: 3240–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1992. Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science 1: 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Alexandra R., Natércia Lima, Clara Viegas, and Amélia Caldeira. 2024. Critical minds: Enhancing education with ChatGPT. Cogent Education 11: 2415286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Ruiqi, Maoli Jiang, Xinlu Yu, Yuyan Lu, and Shasha Liu. 2025. Does ChatGPT enhance student learning? A systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental studies. Computers & Education 227: 105224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Xing, Mingcheng Du, Zihan Zhou, and Yiming Bai. 2025. Facilitator or hindrance? The impact of AI on university students’ higher-order thinking skills in complex problem solving. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 22: 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, D., M. Sunil Kumar, P. Venkateswarlu Reddy, Kavitha Sadam, and D. Sudarsana Murthy. 2022. Implementation of AI pop bots and its allied applications for designing efficient curriculum in early childhood education. International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education 14: 2282–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, Inmaculada, José María Fernández-Batanero, José Fernández-Cerero, and Samuel P. León. 2023. Analysing the impact of artificial intelligence and computational sciences on student performance: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research 12: 171–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonsalves, Chahna. 2024. Generative AI’s Impact on Critical Thinking: Revisiting Bloom’s Taxonomy. Journal of Marketing Education 1: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Kai, Yuchun Zhong, Danling Li, and Samuel Kai Wah Chu. 2023. Effects of chatbot-assisted in-class debates on students’ argumentation skills and task motivation. Computers & Education 10: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heung, Yuk Mui Elly, and Thomas K.F. Chiu. 2025. How ChatGPT impacts student engagement from a systematic review and meta-analysis study. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 8: 100361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Julian P. T., Simon G. Thompson, Jonathan J. Deeks, and Douglas G. Altman. 2003. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. The BMJ 327: 557–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Chenyu, Gaoxia Zhu, and Vidya Sudarshan. 2025. The role of critical thinking on undergraduates’ reliance behaviours on generative AI in problem-solving. British Journal of Educational Technology 56: 1919–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Kuo-Liang, Yi-Chen Liu, and Ming-Qing Dong. 2024a. Incorporating AIGC into design ideation: A study on self-efficacy and learning experience acceptance under higher-order thinking. Thinking Skills and Creativity 52: 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Yueh-Min, Wei-Sheng Wang, Hsin-Yu Lee, Chia-Ju Lin, and Ting-Ting Wu. 2024b. Empowering virtual reality with feedback and reflection in hands-on learning: Effect of learning engagement and higher-order thinking. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 40: 1413–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Gwo-Jen, Chiu-Lin Lai, Jyh-Chong Liang, Hui-Chun Chu, and Chin-Chung Tsai. 2018. A long-term experiment to investigate the relationships between high school students’ perceptions of mobile learning and peer interaction and higher-order thinking tendencies. Educational Technology Research and Development 66: 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Sunghwan. 2022. Examining the effects of artificial intelligence on elementary students’ mathematics achievement: A meta-Analysis. Sustainability 14: 13185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilgun Dibek, Munevver, Merve Sahin Kursad, and Tolga Erdogan. 2024. Influence of artificial intelligence tools on higher order thinking skills: A meta-analysis. Interactive Learning Environments 33: 2216–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskender, Ali. 2023. Holy or unholy? Interview with open AI’s ChatGPT. European Journal of Tourism Research 34: 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johinke, Rebecca, Robert Cummings, and Frances Di Lauro. 2023. Reclaiming the technology of higher education for teaching digital writing in a post—Pandemic world. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice 20: 01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Talha Ahmed, Muhammad Alam, Safdar Ali Rizvi, Zeeshan Shahid, and M. S. Mazliham. 2023. Introducing AI applications in engineering education (PBL): An implemen-tation of power generation at minimum wind velocity and turbine faults classification using AI. Computer Applications in Engineering Education 32: 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberly, A. Riegel. 2023. Project-based learning (PBL): Less project, more problem. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 152: 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, Sara. 2024. AI Facilitated Critical Thinking in an Undergraduate Project Based Service-Learning Course. Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management 24: 123–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, F. J., Ludwika Goodson, and Faranak Rohani. 1998. Higher Order Thinking Skills: Definitions, Strategies, Assessment. Center for Advancement of Learning and Assessment. Tallahassee: Florida State University. [Google Scholar]

- Kooli, Chokri. 2023. Chatbots in education and research: A critical examination of ethical implications and solutions. Sustainability 15: 5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, Barbara Z., Christine Moser, Arran Caza, Katrin Muehlfeld, and Laura A. Colombo. 2024. Critical thinking in the age of generative AI. Academy of Management Learning & Education 23: 373–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Hsin-Yu, Pei-Hua Chen, Wei-Sheng Wang, Yueh-Min Huang, and Ting-Ting Wu. 2024. Empowering ChatGPT with guidance mechanism in blended learning: Effect of self-regulated learning, higher-order thinking skills, and knowledge construction. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 21: 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Arthur, and David Smith. 1993. Defining higher order thinking. Theory into Practice 32: 131–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Haifeng, and Wei Wang. 2023. Human-machine collaborative in-depth inquiry teaching model: The case of ChatGPT and QQ-based collaborative inquiry learning system. Open Education Research 29: 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Haifeng, and Wei Wang. 2024. Human-machine debate inquiry method: A study on using debate-style intelligent dialogue robots to foster students’ higher-order thinking skills. E-education Research 45: 106–12+128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Haifeng, Wei Wang, Guangxin Li, and Yuan Wang. 2024a. Smart midwifery teaching method: The practice of “smart Socratic dialogue robot” teaching. Open Education Research 30: 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Pin-Hui, Hsin-Yu Lee, Chia-Ju Lin, Wei-Sheng Wang, and Yueh-Min Huang. 2024b. InquiryGPT: Augmenting ChatGPT for enhancing inquiry-based learning in STEM education. Journal of Educational Computing Research 62: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yan, Jie Xu, Chengyuan Jia, and Xuesong Zhai. 2024c. The current status and reflections on the application of generative artificial intelligence among university students: A case study from Zhejiang University. Open Education Research 30: 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Jun, Zile Liu, Cong Wang, Yanhua Xu, Jiayu Chen, and Yichun Cheng. 2024a. K-12 students’ higher-order thinking skills: Conceptualization, components, and evaluation indicators. Thinking Skills and Creativity 52: 101551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Ming, Shuo Guo, Zhongming Wu, and Jian Liao. 2024b. Generative artificial intelligence reshaping the landscape of higher education: Content, cases, and pathways. E-educational Research 45: 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yangxia. 2022. Connotation and cultivation of mathematical advanced thinking ability. Creative Education Studies 10: 1294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Kaili, Jianrong Zhu, Feng Pang, and Rustam Shadiev. 2024. Understanding the relationship between college students’ artificial intelligence literacy and higher-order thinking skills using the 3P model: The mediating roles of behavioral engagement and peer interaction. Educational Technology Research and Development 72: 10434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Gongbo, Changsong Niu, Lu Lu, Ling Wu, and Lin Huang. 2025. Empirical study on the double-edged effects of generative artificial intelligence on team creativity among university students. Education and Information Technologies 30: 18853–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniktala, Mehak, Min Chi, and Tiffany Barnes. 2023. Enhancing a student productivity model for adaptive problemsolving assistance. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction 33: 159–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, Barbara, Yukie Toyama, Robert Murphy, and Marianne Baki. 2013. The effectiveness of online and blended learning: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Teachers College Record 115: 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education Singapore. 2021. Framework for 21st-Century Competencies and Student Outcomes. Available online: https://www.moe.gov.sg/education-in-sg/21st-century-competencies (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- OECD. 2019. Fostering Students’ Creativity and Critical Thinking: What it Means in School. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/fostering-students-creativity-and-critical-thinking_62212c37-en (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Peters, Jaime L., Alex J. Sutton, David R. Jones, Keith R. Abrams, and Lesley Rushton. 2008. Contour-enhanced meta-analysis funnel plots help distinguish publication bias from other causes of asymmetry. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 61: 991–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujawan, I. G. N., N. N. Rediani, I. G. W. S. Antara, N. N. C. A. Putri, and G. W. Bayu. 2022. Revised Bloom taxonomy-oriented learning activities to develop scientific literacy and creative thinking skills. Jurnal Pendidikan IPA Indonesia 11: 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, Febri W., Itsar B. Rangka, Siti Aminah, and Mint. H. R. Aditama. 2023. ChatGPT in the higher education environment: Perspectives from the theory of higher-order thinking skills. Journal of Public Health 45: 840–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Jia, Yanru Xu, Ji’an Liu, and Kai Xue. 2024. The impact of generative AI tools on critical thinking and independent learning ability in university students. E-Education Research 45: 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusandi, M Arli, Ahman, Ipah Saripah, Deasy Yunika Khairun, and Mutmainnah. 2023. No worries with ChatGPT: Building bridges between artificial intelligence and education with critical thinking soft skills. Journal of Public Health 45: 602–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, Muhammad Farrukh, Shuo Xu, and Hira Zahid. 2024. Exploring the impact of generative AI-based technologies on learning performance through self-efficacy, fairness & ethics, creativity, and trust in higher education. Education and Information Technologies 30: 3691–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Wanruo, and Xibin Han. 2024. The impact of generative artificial intelligence on learning analytics research: Current status and future directions—A review of LAK24. E-Educational Research 45: 113–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Dan, Chengcong Zhu, Zuodong Xu, and Guangtao Xu. 2024. Analysis of college students’ programming learning behavior based on generative AI. E-Education Research 45: 113–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Shuhua, Zhuyi Angelina Li, Maw-Der Foo, Jing Zhou, and Jackson G. Lu. 2025. How and for whom using generative AI affects creativity: A field experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Shuxin, and Young Woo Cho. 2021. Towards a higher order thinking skills—Oriented translation competence model. Translation, Cognition & Behavior 4: 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Willik, Esmee M., Erik W. van Zwet, Tiny Hoekstra, Frans J. van Ittersum, Marc H. Hemmelder, Carmine Zoccali, Kitty J. Jager, Friedo W. Dekker, and Yvette Meuleman. 2021. Funnel plots of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) to evaluate healthcare quality: Basic principles, pitfalls and considerations. Nephrology 26: 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Jin, and Wenxiang Fan. 2025. The effect of ChatGPT on students’ learning performance, learning perception, and higher-order thinking: Insights from a meta-analysis. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 12: 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Siyao, and Yating Huang. 2024. Facilitation or Inhibition: The Impact of Generative Artificial Intelligence on College Students’ Creativity. China Higher Education Research 11: 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Wei-Sheng, Chia-Ju Lin, Hsin-Yu Lee, Yueh-Min Huang, and Ting-Ting Wu. 2025. Enhancing self-regulated learning and higher-order thinking skills in virtual reality: The impact of ChatGPT-integrated feedback aids. Education and Information Technologies 30: 19419–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yanbei, and Liping Liu. 2024. Learning elements for developing higher-order thinking in a blended learning environment: A comprehensive survey of Chinese vocational high school students. Education and Information Technologies 29: 19443–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yan, Jari Lavonen, and Kirsi Tirri. 2019. Twenty-first century competencies in the Chinese science curriculum. In Nordic-Chinese Intersections Within Education. Palgrave Studies on Chinese Education in a Global Perspective. Edited by Haiqin Liu, Fred Dervin and Xiangyun Du. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 151–71. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Yeqing, Jingdong Zhu, Minkai Wang, Fang Qian, Yiling Yang, and Jie Zhang. 2024. The impact of a digital game-based AI chatbot on students’ academic performance, higher-order thinking, and behavioral patterns in an information technology curriculum. Applied Sciences 14: 6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Ya-Ting Carolyn. 2015. Virtual CEOs: A blended approach to digital gaming for enhancing higher-order thinking and academic achievement among vocational high school students. Computers & Education 81: 281–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawacki-Richter, Olaf, Victoria I. Marín, Melissa Bond, and Franziska Gouverneur. 2019. Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education—Where are the educators? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 16: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Wenlan, and Jiao Hu. 2019. Has project-based learning taken effect? A meta-analysis based on 46 experimental and quasi-experimental studies. Audio-Visual Education Research 2: 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yanjun, and Yijin Zhu. 2022. Effects of educational robotics on the creativity and problem-solving skills of K-12 students: A meta-analysis. Educational Studies 50: 1539–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Guoqing, Haixi Sheng, Yaxuan Wang, Xiaohui Cai, and Taotao Long. 2025. Generative artificial intelligence amplifies the role of critical thinking skills and reduces reliance on prior knowledge while promoting in-depth learning. Education Sciences 15: 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Lanqin, Jiayu Niu, Lu Zhong, and Juliana Fosua Gyasi. 2023. The effectiveness of artificial intelligence on learning achievement and learning perception: A meta-analysis. Interactive Learning Environments 31: 5650–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Lanqin, Lei Gao, and Zichen Huang. 2024. Can generative AI-powered dialogue robots promote online collaborative learning performance? E-Education Research 45: 70–76+84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Xue, Da Teng, and Hosam Al-Samarraie. 2024. The mediating role of generative AI self-regulation on students’ critical thinking and problem-solving. Education Sciences 14: 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).