Abstract

This paper proposes JADEGBO, a hybrid gradient-based metaheuristic for solving complex single- and multi-constraint engineering design problems as well as cost-sensitive security optimisation tasks. The method combines Adaptive Differential Evolution with Optional External Archive (JADE), which provides self-adaptive exploration through p-best mutation, an external archive, and success-based parameter learning, with the Gradient-Based Optimiser (GBO), which contributes Newton-inspired gradient search rules and a local escaping operator. In the proposed scheme, JADE is first employed to discover promising regions of the search space, after which GBO performs an intensified local refinement of the best individuals inherited from JADE. The performance of JADEGBO is assessed on the CEC2017 single-objective benchmark suite and compared against a broad set of classical and recent metaheuristics. Statistical indicators, convergence curves, box plots, histograms, sensitivity analyses, and scatter plots show that the hybrid typically attains the best or near-best mean fitness, exhibits low run-to-run variance, and maintains a favourable balance between exploration and exploitation across rotated, shifted, and composite landscapes. To demonstrate practical relevance, JADEGBO is further applied to the following four well-known constrained engineering design problems: welded beam, pressure vessel, speed reducer, and three-bar truss design. The algorithm consistently produces feasible high-quality designs and closely matches or improves upon the best reported results while keeping computation time competitive.

1. Introduction

Contemporary engineering design and optimisation tasks frequently entail vast and intricate search spaces, prompting the rise of advanced metaheuristic strategies that can handle high-dimensional and strongly nonconvex problems [1]. While classical gradient-driven techniques remain effective on smooth and modestly complex objectives, their reliance on local information makes them ill-suited to the rugged, multimodal landscapes encountered in disciplines such as structural engineering, control synthesis, and process tuning [2]. In contrast, algorithms that maintain and evolve a population of candidate solutions, particularly those rooted in evolutionary computation, have shown a distinct capacity to sample wider regions of the search space and to escape from local minima [3].

Within this class, JADE—an adaptive differential evolution variant—modifies its mutation and crossover parameters on the fly based on past successes [4]. Such self-tuning helps maintain an effective compromise between global exploration and local refinement and allows JADE to perform reliably across varied optimisation domains [5]. A different paradigm is represented by the Gradient-Based Optimiser (GBO) [6], which incorporates gradient-like search rules into a stochastic framework to intensify local search and accelerate convergence toward high-quality solutions [7].

This work introduces a hybrid JADE–GBO method that sequentially combines the broad search capabilities of JADE with the fine-grained improvement offered by GBO. In the first phase, JADE’s adaptive control of population diversity guides exploration; this is followed by a gradient-inspired refinement stage using GBO, which improves promising individuals. Such a combination is especially useful for challenging engineering tasks where swift exploration must be complemented by the careful optimisation of candidate designs. The resulting hybrid is designed to yield better solutions more rapidly and to reduce the likelihood of stagnation in suboptimal regions.

We test the proposed algorithm on a range of engineering benchmark problems, including truss topology optimisation, fluid dynamic design, and control parameter tuning. Metrics such as convergence rate, final objective value, and solution robustness indicate that the hybrid consistently outperforms JADE and GBO when used separately. Additionally, we show that automatic parameter adaptation enables the method to adjust to different problem characteristics, preserving its effectiveness across heterogeneous scenarios.

By fusing adaptive evolutionary mechanisms with gradient-informed local exploitation, the hybrid JADE–GBO approach advances the metaheuristic optimisation field. Its ability to balance wide-ranging search with precise improvement of promising regions makes it a strong tool for addressing large-scale, complex optimisation problems.

2. Literature Review

Real-world engineering design and network optimisation problems are typically nonlinear, multi-modal, and subject to complex constraints, so a single metaheuristic often struggles to obtain high-quality solutions consistently. This has motivated a large body of work on hybrid metaheuristic and matheuristic algorithms that combine complementary search mechanisms or couple population-based methods with deterministic local optimisation to improve robustness and convergence across diverse engineering applications [8,9,10,11,12].

Early contributions showed that hybridising metaheuristics with exact or gradient-based components can significantly enhance solution quality. Chagwiza et al. combined a Grötschel–Holland exact scheme with a Max–Min Ant System in a hybrid matheuristic for design and network engineering, exploiting global exploration while using exact methods to refine promising regions [8]. Fan et al. proposed a hybrid multi-objective algorithm that integrates a weighted-sum formulation with a quasi-Newton BFGS procedure for engineering applications, achieving rapid descent while maintaining the reasonable diversity of Pareto-optimal solutions [9]. Several works focus on coupling two population-based methods with complementary search dynamics. Zhang et al. coupled Cuckoo Search and Differential Evolution (CSDE) to exploit the global exploration of CS together with the strong local recombination of DE on constrained engineering benchmarks [10]. Yassin et al. introduced a GA–PSO–SQP framework in which genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimisation explore the search space, while sequential quadratic programming acts as a constraint-aware local solver for engineering design problems [11]. Khalilpourazari and Khalilpourazary combined the Water Cycle Algorithm with Moth–Flame Optimisation, using spiral movements and random walks to handle numerical and constrained engineering tasks more effectively [12].

Moreover, many hybrids were built around more recent swarm and physics-inspired optimisers. Han et al. enhanced the moth search algorithm with fireworks-inspired operators to obtain a hybrid scheme that preserves fast convergence while reducing the risk of premature stagnation on difficult numerical and constrained engineering problems [13]. Fakhouri et al. developed a three-component hybrid that couples particle swarm optimisation with the Sine Cosine Algorithm and the Nelder–Mead simplex method; PSO drives global exploration, SCA injects oscillatory search moves, and Nelder–Mead refines elite solutions for engineering design benchmarks [14]. Wang et al. integrated the Aquila Optimiser with the Harris Hawks Optimiser, yielding a hybrid hunting-inspired method that better balances exploration and exploitation on industrial engineering optimisation problems [15].

Other studies in this period explore hybridisation around particular base algorithms. Gurses et al. proposed a hybrid water wave optimisation algorithm in which the original wave-propagation phases are combined with Nelder–Mead local search to solve complex constrained engineering problems [16]. Brajevic et al. designed a hybrid Sine Cosine Algorithm that embeds additional search operators inspired by artificial bee colony behaviour, improving performance on engineering design instances with mixed discrete–continuous variables [17]. Dastan et al. merged teaching–learning-based optimisation with charged system search, using electrostatic interactions together with teacher–student dynamics to tackle engineering and mathematical problems [18]. Liu et al. hybridised the Arithmetic Optimisation Algorithm with a Golden Sine strategy and further diversity-enhancing mechanisms for industrial engineering design, addressing premature convergence in the original AOA [19]. Zhang et al. developed a Hybrid-Flash Butterfly Optimisation Algorithm with logistic mapping, in which additional operators and chaotic control improve the ability of the butterfly optimiser to escape local minima in constrained engineering designs [20].

More recent contributions emphasise multi-strategy ensembles built on top of swarm optimisers. Qiao et al. introduced a hybrid particle swarm optimisation algorithm that incorporates elite opposition-based initialisation, dynamic inertia weights, jump-out strategies, and elements from Whale Optimisation and Differential Evolution to reduce premature convergence and improve constraint handling on classical engineering problems [21]. Hou et al. proposed a variant of the Seagull Optimisation Algorithm equipped with several hybrid strategies to accelerate convergence and strengthen the balance between global and local search in engineering design [22]. Zhang and Xing presented a new hybrid improved Arithmetic Optimisation Algorithm, augmenting AOA with adaptive control parameters and local refinement operators to solve both global numerical and engineering optimisation problems more reliably [23].

Additional multi-strategy hybrids have been constructed by combining distinct swarm paradigms in a single framework. Tang et al. combined multi-strategy particle swarm optimisation with the Dandelion Optimisation Algorithm (PSODO), using dandelion-inspired dispersal to increase population diversity and strengthen constraint handling in engineering design [24]. Zitouni et al. proposed BHJO, a triple-hybrid metaheuristic that fuses Beluga Whale Optimisation, Honey Badger Optimisation, and Jellyfish Search in order to capture different exploration and exploitation behaviours within one algorithm [25]. Singh et al. constructed a hybrid Gazelle Optimisation Algorithm with Differential Evolution, embedding DE mutation and crossover into GOA’s herd-based movement rules to obtain more competitive solutions on engineering design benchmarks [26].

More recent work pushes hybridisation further by combining multiple optimisers or by integrating metaheuristics with advanced AI paradigms. Al Hwaitat et al. introduced JADEDO, a hybrid optimisation method for attack–response planning and engineering design that merges a differential evolution-style mechanism with another population-based optimiser to handle both benchmark and security-oriented scenarios [27]. Panigrahy and Samal proposed the ESO–DE–WHO algorithm, which probabilistically coordinates enhanced seagull optimisation, differential evolution, and wild horse optimisation through a learning matrix, and validated it on CEC 2021 benchmark functions and several real engineering problems [28]. Jonnalagadda et al. explored a quantum–AI hybrid framework in which quantum sampling and large language models are used together to guide search for large-scale engineering applications [29]. In the multi-objective domain, Chalabi et al. extended the Chef-Based Optimisation Algorithm to a multi-objective version (MOCBOA) and systematically compared several hybrid dominance relations to improve convergence and diversity on CEC 2021 benchmarks and real engineering design cases [30].

Hybrid-AI Trends in Structural and Mechanical Engineering

Beyond the development of standalone optimisers, structural and mechanical engineering research has increasingly adopted hybrid AI paradigms that intentionally combine complementary mechanisms (e.g., learning + optimisation, or multiple learners/ensembles) to improve robustness, generalisation, and convergence in challenging real-world settings. In particular, recent SHM and damage-identification studies are progressively moving from single-model solutions toward integrated workflows that couple data-driven inference with auxiliary optimisation stages (e.g., feature/sensor selection, model calibration, and hyperparameter tuning) to better handle noise, nonlinearity, and data scarcity. A recent comprehensive review by Khatir et al. synthesises these developments across mechanical and civil engineering applications and highlights hybridisation as a recurring strategy to enhance stability and convergence behaviour in SHM pipelines [31].

At the algorithmic level, hybridisation is also evident in the optimisation of learning models for damage assessment. Metaheuristic-assisted training/tuning has been explored to complement fast local updates with global stochastic search, thereby reducing sensitivity to local minima and improving predictive reliability. For example, Tran-Ngoc et al. integrate an artificial neural network with a hybrid stochastic optimisation strategy (combining particle swarm and genetic operators) for structural damage assessment, reporting improved training robustness relative to purely conventional training [32]. In parallel, modern gradient-boosting approaches—particularly gradient-boosted decision trees and their enhanced implementations such as XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost—have gained traction in structural applications (including durability and damage diagnosis) due to their strong performance on tabular/mixed-feature engineering data and their ability to capture nonlinear interactions [33]. These broader hybrid-AI advances share a clear conceptual parallel with the hybridisation strategy pursued in this manuscript: rather than relying on a single mechanism, hybrid methods deliberately combine complementary strengths (global exploration vs. local refinement, or diverse learners vs. a single learner) to achieve more reliable search/prediction and improved convergence. The proposed hybrid metaheuristic follows the same guiding principle by integrating distinct search dynamics within one optimiser to enhance robustness on complex engineering optimisation landscapes [34,35].

3. Overview of JADE

Adaptive Differential Evolution with Optional External Archive (JADE) [36] is an enhancement of the standard differential evolution paradigm. It employs self-tuning control of its key parameters and preserves an additional collection of discarded individuals to improve convergence behaviour. In particular, JADE learns suitable values for the mutation constant F and crossover probability from those offspring that lead to improvements and reintroduces diversity via an archive of replaced solutions. This measured coordination between exploration and exploitation enables JADE to attain more rapid and accurate convergence than classical DE.

The method begins with a set of candidate solutions , where each is a d-dimensional vector constrained by lower and upper bounds and . Each individual is evaluated with an objective function that assesses its quality. In each generation, a “current-to-p-best” mutation is applied. For a given target vector , a guiding vector is chosen from the top fraction of the population; a random peer is selected from the population, and a second vector is drawn from the finite archive. The mutant vector is computed by

where F denotes the mutation factor. This construction steers the search toward promising individuals while incorporating random variation and archival information to maintain diversity.

The algorithm then performs a binomial crossover between and to produce a trial vector . A crossover probability drawn from a mean value controls the inheritance of components from the mutant, and a random index ensures that at least one component originates from :

If the trial vector yields a lower objective value than the target, i.e., , it replaces , and the displaced individual is added to the archive to preserve genetic material for future mutations.

Typical ranges for the mutation factor F in JADE lie between and . The algorithm samples F around a running average , and empirical studies recommend an initial value near . Lower values of F can reduce search diversity, whereas higher values encourage broader exploration. The crossover rate is similarly sampled around and generally takes values in ; its exact choice depends on the problem being solved [37].

The running averages and play a central role in parameter adaptation. At the beginning of each generation, candidate values of F and are drawn from distributions centred on and , respectively. After the offspring are evaluated, only those F and values that produced improvements are stored in the sets and . These sets are then used to update and via a weighted moving average with learning rate c. This mechanism biases the sampling toward parameter values that have historically been successful, allowing JADE to automatically adjust its search behaviour to the landscape of the objective function [37]. Without such adaptation, the algorithm would depend on fixed parameter choices and might converge prematurely or stagnate on complex problems.

The external archive A stores individuals that have been replaced during selection. When forming the difference vector in the mutation step, one of the two vectors used in the difference is drawn from this archive rather than from the current population. Injecting these archived solutions introduces diversity by revisiting previously explored regions and can help the algorithm escape local optima [37]. The archived individuals are not directly reinserted into the population, but they influence the mutation and thereby encourage the exploration of directions that might otherwise be neglected.

To promote stable adaptation, JADE tracks the F and values that resulted in successful replacements during each generation. These sets of successful parameters, denoted by and , are used to update the running averages and with a learning rate c (commonly 0.1) as follows:

By basing these updates on empirical success, the algorithm continually adjusts its parameters in a data-driven manner rather than relying on fixed heuristics.

These design choices allow JADE to harmonise global exploration with local refinement. The p-best-driven mutation uses top performers without overfitting to a single best solution, the archive injects diversity by revisiting discarded individuals, and the adaptive rules for F and foster rapid and stable convergence. Consequently, JADE is a robust and efficient optimisation technique for challenging search problems.

3.1. Overview of Gradient-Based Optimiser (GBO)

The Gradient-Based Optimiser (GBO), inspired by the gradient-based Newton’s method, uses the following two main operators: the gradient search rule (GSR) and the local escaping operator (LEO). GBO also employs a set of vectors to explore the search space. The GSR utilises a gradient-like update strategy to enhance exploration and accelerate convergence, aiming to find better positions in the search domain. In this framework, the minimisation of an objective function is assumed.

GBO merges gradient and population-based techniques. In general, an optimisation problem is characterised by a set of decision variables, constraints, and an objective function to be minimised. The control parameters of GBO include a parameter (often denoted by a) to guide the transition from exploration to exploitation, as well as a probability rate for certain stochastic operations. The number of iterations M and the population size N are chosen based on problem complexity. Each member of the population is referred to as a “vector.” Suppose we have N such vectors in a D-dimensional space. As shown in Equation (4), a vector is represented by the following:

Usually, the initial vectors of GBO are randomly generated in the D-dimensional domain, as shown in Equation (5), expressed as follows:

where and are the lower and upper bounds of the decision variable X, and is a uniform random number in .

- Gradient Search Rule (GSR).

In the gradient search ru le, vectors are directed to move within the feasible domain to discover better positions. This component is motivated by Newton’s gradient-based method to enhance exploration and speed up convergence. Since many real-world problems are non-differentiable, GBO employs a numerical gradient approach instead of a direct derivative. One central differencing approximation, shown in Equation (6), is the following:

Equation (7) demonstrates a Newton-like update as follows:

Because GSR constitutes the core of the proposed algorithm, certain modifications are introduced to convert Equation (7) into a population-based mechanism. Specifically, in a minimisation problem, the positions and (with worse and better fitness values, respectively) are replaced by and . Moreover, substitutes for its own fitness for computational efficiency. The resulting GSR is shown in Equation (8), expressed as follows:

where randn is a normally distributed random number, and is a small constant (e.g., in ). To balance exploration and exploitation, a random parameter is introduced as shown in Equation (9), expressed as follows:

where m is the current iteration, M is the total number of iterations, and typical values for might be . Incorporating the random factor as a multiplicative scaling of the gradient search rule in Equation (8) yields the following expression:

Equation (11) shows how is determined so that it can change at every iteration, thus promoting population diversity as follows:

where are different indices randomly selected from .

Additionally, GBO introduces a direction of movement (DM) to further exploit the region near . Equation (12) defines DM, and Equation (13) shows the corresponding parameter as follows:

Thus, combining GSR and DM, we update the current vector according to Equations (14) and (15) (two forms are often used depending on the specific Newton-like variant) as follows:

A further modification yields another updated vector . As shown in Equation (16), is focused more on local exploitation as follows:

Finally, by combining and , GBO produces a new solution , as shown in Equation (17), expressed as follows:

where

and are random numbers in .

- Local Escaping Operator (LEO).

The LEO improves GBO’s ability to address complex problems by helping solutions escape local optima. It substantially modifies the newly updated position . The LEO generates from several vectors, including , and . This is shown in Equation (19), expressed as follows:

where is a uniform random number, follows a normal distribution (mean 0, std. 1), and are random numbers controlled by uniform or binary parameters. In Equation (20), the vector can be either a new random solution or a randomly selected vector from the population, thereby increasing diversity as follows:

3.2. Limitations of the Base Algorithms and Hybridisation Rationale

Although both JADE and GBO have demonstrated solid performance on a range of optimisation problems, each algorithm exhibits inherent shortcomings. JADE’s adaptive parameter control and external archive improve convergence, but these mechanisms increase complexity and memory overhead and its performance can be sensitive to the greediness parameter p [37]. Moreover, because it relies on differential mutations, JADE may require many generations to refine solutions in the vicinity of optima. Conversely, GBO uses gradient-inspired operators that can accelerate local convergence, yet its computational cost grows with the search-space dimensionality, and it requires significant resources for high-dimensional problems [7]. While its gradient search rule balances exploration and exploitation and its local escaping operator further intensifies exploitation, GBO depends on good starting points to perform effectively [7].

The hybrid JADEGBO algorithm combines these complementary strengths. JADE first performs broad exploration using adaptive control of F and and diversity injections from the archive. This stage locates promising regions in the search space. The search then transitions to GBO, which applies gradient-inspired updates and local escaping to intensively exploit these regions. By using JADE’s adaptive exploration to supply high-quality starting points and GBO’s gradient-based exploitation to refine them, the hybrid aims to overcome the individual limitations of its components. Theoretical research on hybrid swarm and gradient-based methods suggests that such combinations can accelerate convergence and improve solution quality [7].

4. Proposed Hybrid JADEGBO Model

The increasing complexity of real-world optimisation problems necessitates the use of robust and adaptive metaheuristic algorithms. In particular, the integration of Adaptive Differential Evolution with Optional External Archive (JADE) [36] and the Gradient-Based Optimiser (GBO) [7] has shown promise for efficiently searching large and multimodal solution spaces. Throughout this section, boldface symbols such as denote d-dimensional vectors, subscripts index individuals in the population (), and superscripts index iterations (). This section describes a hybrid JADEGBO model, including its mathematical formulations, pseudocode, and a flowchart illustrating its workflow.

4.1. Algorithmic Motivation and Overview

The JADE variant enhances standard differential evolution by learning its control parameters and by retaining an archive of previously discarded individuals. Updating the averages of the mutation scale and crossover probability based on successful trials allows the method to modulate the balance between global exploration and local exploitation over time. In contrast, the Gradient-Based Optimiser employs gradient-inspired moves and a local escape operator to intensify the search around promising solutions while still having mechanisms to break free from local minima. In the proposed hybrid scheme, these two ideas are applied in sequence as follows: JADE is first run for a fixed number of iterations to locate promising subregions of the search space, and the search then transitions to GBO, which performs a more focused refinement of the solutions identified by JADE to achieve greater precision.

4.2. JADE Phase

Consider a population of size , where each individual is a d-dimensional vector constrained by lower and upper bounds, and . In JADE, each individual undergoes mutation and crossover operations based on adapted parameters . The key innovation in JADE is the introduction of an archive to store replaced solutions and the use of p-best selection to guide mutation.

For an individual (the target vector), a p-best individual (selected from the top best solutions) helps build a mutated vector according to Equation (21)

where is a randomly chosen individual from the population (excluding i), and is selected randomly from the union of the population and the archive. The scalar F (mutation factor) is adaptively sampled around a running mean . Next, a binomial crossover is applied between and , as shown in Equation (22), expressed as follows:

The crossover rate is also drawn around a mean that is iteratively updated based on successful trials. The resulting offspring is evaluated; if it improves upon , then is replaced by , and the discarded solution is added to the archive. After sorting and recording the best solution, JADE repeats this process for generations.

4.3. Transition to GBO

Once JADE completes its iterations, the population is considered the final output of the JADE phase. Let be the best solution identified during JADE. We initialise GBO as follows:

In other words, GBO inherits a promising population and global best solution from the JADE phase, ensuring that the subsequent refinement begins in a high-quality region of the search space.

4.4. GBO Phase

GBO employs gradient-inspired updates to refine solutions, incorporating local escaping operators (LEOs) to maintain diversity. Let represent the i-th individual in at a particular iteration. The parameter is updated each iteration as shown in Equation (24), expressed as follows:

where t is the current GBO iteration index. An auxiliary parameter is given by Equation (25)

These coefficients modulate the stochastic search steps.

Two candidate moves, and , are typically generated for each individual via gradient-based components and differential terms. For instance, one move might be the one represented by Equation (26)

and another as shown in Equation (27)

where is a difference-based term (e.g., for some randomly chosen and ), and denotes a gradient search rule as seen in Equation (28), expressed as follows:

with controlling the search spread, related to , and avoiding division by zero. The two moves are combined to produce a new candidate solution via mixing operations. A local escaping operator is then applied with probability to further perturb .

Upon evaluating , if it outperforms the original , the update is accepted. The global best and worst solutions (, ) are also updated accordingly. This process runs for iterations, ultimately returning the best-discovered solution as the outcome of the hybrid JADEGBO framework.

4.5. Pseudocode of the Hybrid Approach

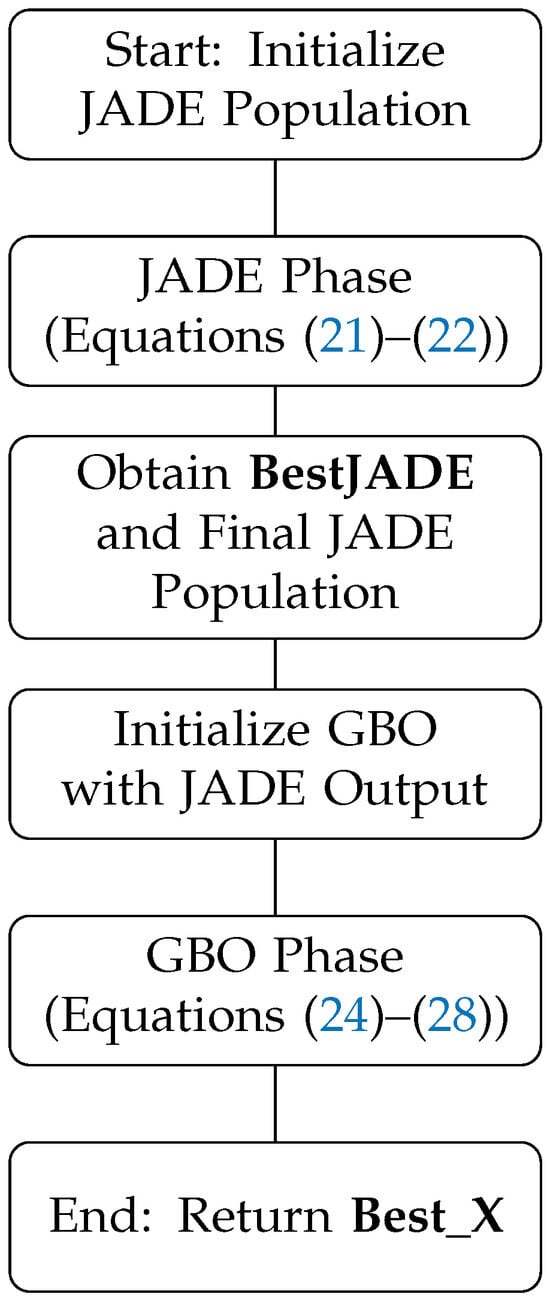

4.6. Flowchart of the Proposed Approach

The diagram in Figure 1 outlines the key stages of our hybrid algorithm. After an initialisation step, the process enters a JADE phase featuring the adaptive control of F and , selection of p-best individuals, and maintenance of an external archive. Once this stage is completed, the best individuals from JADE are passed to a GBO stage, which applies gradient-inspired operators for a final refinement of the solution.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the proposed Hybrid JADEGBO approach.

By integrating JADE’s adaptive exploration with GBO’s gradient-oriented refinement, the Hybrid JADEGBO algorithm can accelerate initial convergence and achieve more precise final solutions. JADE rapidly explores the search space and guides the population toward promising regions, which are then intensively exploited by GBO to further improve solution quality and avoid local optima through local escaping operators.

| Algorithm 1 Hybrid JADEGBO pseudocode |

|

4.7. Computational Complexity, Memory Footprint and Scalability

Let be the population size; d the problem dimensionality; and the iteration budgets of the JADE and GBO phases, respectively; and the archive size (in JADE, typically ). Let denote the time required to evaluate the objective function (and constraints, when present) for a single candidate solution; in simulation-driven engineering design, can dominate the total runtime, while for analytical benchmarks, it is usually much smaller than the search overhead.

Per generation, JADE performs mutation and crossover for each individual, both of which require a constant number of vector additions/subtractions and scalar multiplications. This yields a per-generation overhead of for creating trial vectors, plus for evaluating them. In addition, selecting the p-best set commonly relies on ranking the population. If the whole population is sorted once per generation, the ranking cost is ; if a partial selection (top-) is used, this can be reduced to in expected time. Parameter adaptation (building and and updating ) is linear in the number of successful offspring and is bounded by per generation. Therefore, the total JADE runtime satisfies

where the term corresponds to full sorting (it becomes with partial selection).

GBO updates each vector through the gradient search rule (GSR), a difference-based movement (DM), and a mixing step. Each update uses a constant number of vector operations, giving overhead per individual, i.e., per iteration, plus for evaluating the new candidates. The local escaping operator (LEO) is applied with probability , and its cost is also when triggered; hence it contributes an expected term. Overall,

- Hybrid JADEGBO (total time complexity).

Because the phases are executed sequentially, the total runtime is approximately additive as follows:

When objective evaluations are expensive (e.g., finite-element or CFD analyses), the dominant term is typically , and the algorithmic overhead becomes comparatively minor. For analytical benchmarks, the and ranking terms can be more visible.

The memory demand is mainly determined by storing the population and, in JADE, the external archive. Storing vectors of dimension d requires space, and the archive adds . Additional scalars (fitness values, samples, and a few temporary vectors) require only or memory. The peak memory of the hybrid is therefore

4.8. Scalability on High-Dimensional Problems

Scalability is primarily affected by how and grow with d as follows: (i) many differential evolution guidelines suggest is proportional to d (e.g., ), which implies memory; (ii) for rotated benchmark functions and other objectives involving dense linear transforms, can scale as , leading to a worst-case runtime growth on the order of when combined with . In practice, this means that beyond moderate dimensions, performance becomes increasingly limited by (a) the sheer number of decision variables and (b) the cost of evaluating and comparing many candidates.

4.9. Theoretical Consistency of the JADE Exploration and GBO Exploitation Interaction

The proposed JADEGBO framework is a sequential hybrid that is theoretically coherent with the classical diversification–intensification (exploration–exploitation) principle in metaheuristic design. The key idea is that JADE and GBO implement complementary search operators with compatible selection logic, so composing them in two phases yields a single, well-defined stochastic search process that transitions from global sampling to local refinement without disrupting solution quality.

- (i)

- Operator complementarity: global sampling vs. local refinement.

JADE is an adaptive differential evolution variant whose mutation strategy (current-to-p-best with an external archive) explicitly promotes diversification while still biasing the search toward high-quality regions [36]. The p-best guidance provides a controlled drift toward promising areas, whereas the difference term that involves an archived vector injects directions that are not available in the current population, counteracting premature loss of diversity. This makes JADE well-suited for locating multiple basins of attraction on rugged or rotated landscapes.

Conversely, GBO is designed to intensify the search by using gradient-inspired update rules and Newton-like step constructions that are locally informative even when explicit derivatives are unavailable. The gradient search rule (GSR) and direction of movement (DM) generate steps that exploit the current best/worst structure of the population, accelerating convergence once the population is already near a good region. Importantly, the local escaping operator (LEO) retains a stochastic escape mechanism, so exploitation does not degenerate into a purely local, easily trapped descent [6,7]. Therefore, the JADE → GBO handoff is consistent with the following two-stage design: JADE increases the probability of entering a good basin, and GBO increases the probability of efficiently reaching a high-quality minimum inside that basin.

- (ii)

- Consistent selection and monotone best-so-far preservation.

Both phases employ the following improvement-based acceptance rule: a newly generated candidate replaces its parent only if it improves the objective (or the penalised objective in constrained cases). As a consequence, the best-so-far fitness is non-increasing throughout the entire hybrid run. If we denote by the best solution found up to iteration t (across both phases), then the elitist replacement implies

because no accepted update can worsen the incumbent best. This property guarantees that the phase transition cannot degrade the best solution already obtained by JADE; switching to GBO can only maintain or improve the current best. Hence, the interaction is theoretically consistent in the sense that it preserves solution quality while changing the search bias from global to local.

- (iii)

- Coherent composition as a single stochastic process.

The hybrid can be viewed as the composition of two stochastic transition operators acting on the population state. Let denote the population at iteration t. The JADE phase defines a transition kernel (mutation/crossover/selection with success-history adaptation and archive), and the GBO phase defines (GSR/DM/mixing with optional LEO and selection). Executing iterations followed by iterations corresponds to the composed operator

which is a standard and well-posed construction in hybrid metaheuristics, outlined as follows: the output distribution of the first operator becomes the input distribution of the second. This composition is particularly natural here because (i) both operators are population-based and operate on the same bounded domain, and (ii) both use randomised difference-based moves, so the state representation and the feasibility handling (bounds/penalties) remain consistent across phases.

In addition, GBO is empirically strongest when initialised in a region where the best/worst structure already provides a meaningful directional signal; otherwise, its gradient-inspired steps may spend iterations forming a useful search geometry [7]. JADE addresses this by rapidly allocating probability mass toward promising regions through p-best guidance and adaptive parameter learning [36]. In basin-of-attraction terms, JADE increases the likelihood that at least one individual lies inside (or near) the basin of a high-quality minimum; the subsequent GBO phase then behaves as an efficient local improver that tightens the solution around that basin. The LEO further ensures that, even during exploitation, the process retains a nonzero chance of escaping local stagnation. Therefore, the interaction is consistent with the following theoretical role assignment: JADE improves the reachability of good basins, while GBO improves convergence efficiency within those basins.

5. Experiments and Discussion

In this section, we evaluate the performance of the proposed Hybrid JADEGBO algorithm across a series of benchmark functions and a real-world engineering optimisation problem. The subsequent sections first outline the benchmark suites used in the study and the associated experimental parameters. This is followed by a comparative evaluation of the hybrid algorithm’s performance against several existing methods. To demonstrate the practical benefits of Hybrid JADE–GBO, a detailed case study on the design and optimisation of a cantilever beam is then presented.

5.1. Benchmark Description (CEC2017)

The CEC2017 test suite consists of a diverse array of single-objective optimisation tasks devised to evaluate how well an algorithm copes with different landscape features. It includes unimodal and multimodal functions as well as hybrid and composite problems, and many of these are subjected to shifts or rotations in the decision variables. Such transformations emulate real-world complications—like misaligned coordinate systems or displaced global optima—that can make an optimisation problem substantially more difficult.

5.2. Experimental Setup

To ensure an equitable comparison, all methods are tested under identical conditions. They are started with the same population size and are allowed to run for no more than 30 iterations. Initial populations are sampled uniformly from the prescribed domain for each CEC2017 problem so that each algorithm begins with comparable diversity. The search is halted either when the iteration cap is reached or when the termination criterion recommended for the benchmark is satisfied. Because these algorithms are stochastic, each test function is solved many times—typically 30 independent runs—and summary statistics such as the average objective value and its standard deviation are reported. All implementations are executed within the same computational environment to ensure that any differences in outcome are attributable to the algorithms themselves rather than to variations in hardware or software.

6. Evaluated Algorithms

The experimental comparison encompasses twenty-one distinct optimisation methods, which are listed in Table 1. The selection ranges from well-known heuristics—such as genetic algorithms, simulated annealing, and particle swarm optimisation—to more recent bio-inspired and swarm-intelligence approaches including the Aquila Optimiser, Chinese Pangolin Optimiser, Frilled Lizard Optimisation, and the Synergistic Swarm Optimisation Algorithm. By incorporating techniques introduced from the early 1960s through to 2024, the testbed spans both mature and contemporary approaches, providing a broad foundation for evaluating performance across varied problem domains.

Table 1.

Optimisation algorithms.

6.1. Discussion of the CEC2017 Comparative Results

Table 2 and Table 3 report the CEC2017 results (30 independent runs, 1000 iterations) in terms of the mean, standard deviation, and the overall rank among all compared optimisers. The results demonstrate the clear and consistent superiority of JADEGBO across the suite as follows: it achieves rank 1 on 28 out of 30 functions (F1–F23 and F26–F30), yielding an average rank of approximately over all functions. On the unimodal functions (F1–F3), JADEGBO reaches the shifted optima exactly (100, 200, and 300) with zero variance, while the competing methods often remain several orders of magnitude worse, which confirms both fast convergence and high reliability. The same behaviour is observed on several multimodal cases (e.g., F4, F6, and F9), where JADEGBO attains (or nearly attains) the known optima with negligible standard deviations, whereas the majority of baselines exhibit larger errors and noticeably higher run-to-run dispersion. For the hybrid and composite functions (F11–F23 and F26–F30), the proposed algorithm remains the top-ranked method and maintains comparatively small standard deviations on many functions (e.g., F11 and F17), indicating robust performance on highly rugged, rotated, and composite landscapes. Only two exceptions are observed as follows: on F24 and F25, JADEGBO is not the best performer (rank 3 and rank 6, respectively), where SHIO/MFO (F24) and TSO (F25) obtain better mean values; nevertheless, JADEGBO remains competitive on these cases and preserves a stable variance profile. Overall, although a few optimisers can outperform the hybrid on isolated functions, the two tables collectively confirm that JADEGBO provides the most consistent and dominant performance over the full CEC2017 benchmark set.

Table 2.

Comparison results of JADEGBO with other optimisers over CEC2017 Part 1, run = 30, iterations = 1000.

Table 3.

Comparison results of JADEGBO with other optimisers over CEC2017 Part 2, run = 30, iterations = 1000.

6.2. Wilcoxon Sum-Rank Test Results

The Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann–Whitney U) test (See Table A1 and Table A2) (at ) confirms that the improvements achieved by JADEGBO are statistically meaningful rather than random. Across the tested functions (F1–F12), the reported p-values are overwhelmingly small (typically in the range from to ), and the outcome indicator is predominantly “+”, showing that JADEGBO significantly outperforms most competitors on nearly all cases. In particular, JADEGBO records a complete set of wins () against several optimisers (e.g., GBO, FLO, RSO, SHO, RIME, SCSO, DOA, ZOA, and also TSO, SSOA, GWO, WOA, SHIO, OHO, and AOA), demonstrating strong and consistent dominance. Only the following few exceptions appear: CMAES and MFO exhibit isolated ties (one function each), while AO shows a small number of non-significant differences and an occasional loss, and HLOA is the most competitive with two losses and two ties (notably on F9 and F10), indicating that it can match or surpass JADEGBO on a limited subset of functions. The Wilcoxon results strongly support that JADEGBO delivers statistically significant superiority over the comparison set on the vast majority of benchmark problems.

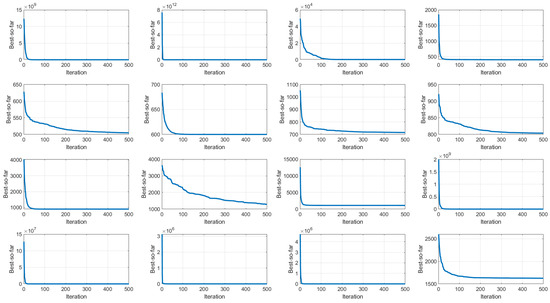

6.3. Convergence Curve Analysis

Figure 2 plots the evolution of the best objective value found by JADEGBO over 500 iterations for each of the CEC2017 functions (F1–F16). In most cases the curves drop sharply at the beginning, suggesting that the hybrid quickly traverses the search space and escapes poor local optima. As the run proceeds, the trajectories become more gradual, indicating a shift from broad exploration to focused refinement. The rate of improvement varies across problems—functions such as F1–F3 show rapid progress, whereas others like F10 and F12 improve more slowly—reflecting differences in landscape complexity. The final values attained across all functions demonstrate that the method consistently identifies high-quality solutions. Overall, the convergence profiles suggest that JADEGBO couples strong early exploration with steady convergence, although additional tuning could further improve performance on the more challenging problems.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the JADEGBO convergence curve over CEC2017 (F1–F16).

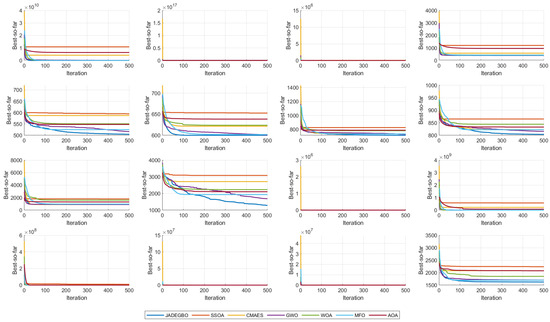

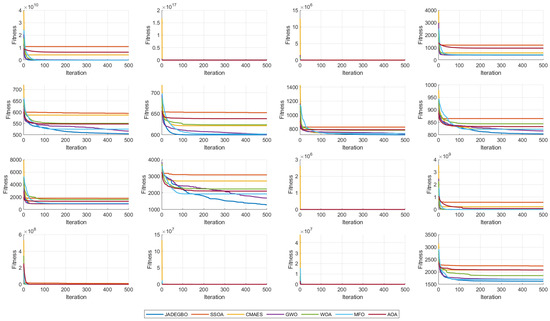

Figure 3 presents the convergence curves of JADEGBO in comparison with several other optimisation algorithms, including SSOA, CMAES, GWO, WOA, MFO, and AOA, across the CEC2017 benchmark functions (F1–F16). The results reveal that JADEGBO consistently achieves superior convergence behaviour compared to the other optimisers. In the initial iterations, all algorithms exhibit a steep decline in function values, indicating strong exploratory capabilities. However, JADEGBO demonstrates a more rapid reduction in function values and continues to improve solutions over iterations, highlighting its superior balance between exploration and exploitation. Notably, algorithms such as CMAES and AOA often stagnate early, failing to reach lower objective function values compared to JADEGBO. Similarly, some optimisers like SSOA and MFO display slower convergence, suggesting weaker adaptability to complex problem landscapes. In functions with high complexity, JADEGBO maintains a significant advantage, with lower final function values, demonstrating its robustness and efficiency. Overall, the comparison confirms that JADEGBO outperforms its counterparts in terms of convergence speed and solution quality, making it a more effective choice for complex optimisation problems.

Figure 3.

Convergence curve analysis of the compared optimisers over CEC2017 (F1–F16).

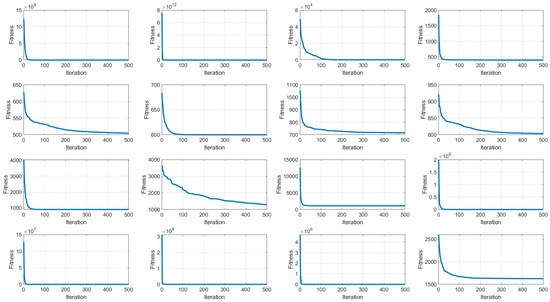

6.4. Average Fitness Analysis

In Figure 4, the mean objective values obtained by JADEGBO over the course of the run are plotted for the CEC2017 problems F1–F16. The curves show that the hybrid quickly reduces the objective values, with a pronounced drop in the early stages that reflects strong exploratory behaviour and an ability to move away from poor local minima. As the run continues, the pace of improvement becomes more gradual, indicating a transition to a more exploitative phase in which existing solutions are fine-tuned. Regardless of the specific test function, the algorithm consistently attains low average fitness by the end of the run, illustrating its robustness across different landscape types. The final averages confirm that JADEGBO reliably produces high-quality solutions and is competitive for challenging optimisation tasks. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the algorithm maintains a good balance between exploration and exploitation while steadily converging toward optimal solutions.

Figure 4.

JADEGBO average fitness over CEC2017 (F1–F16).

Figure 5 presents the average fitness performance of JADEGBO in comparison with other optimisation algorithms, including SSOA, CMAES, GWO, WOA, MFO, and AOA, over the CEC2017 benchmark functions (F1–F16). The results indicate that JADEGBO consistently achieves superior fitness values, demonstrating its strong optimisation capability. In the early iterations, all algorithms exhibit a rapid decline in fitness, indicating effective initial exploration. However, JADEGBO maintains a more aggressive descent and continues improving solutions over iterations, showcasing its ability to balance exploration and exploitation effectively.

Figure 5.

Average fitness of the compared optimisers over CEC2017 (F1–F16).

Notably, some algorithms, such as CMAES and AOA, stagnate at higher fitness values, indicating weaker adaptability to complex problem landscapes. Similarly, SSOA and MFO show slower convergence trends, suggesting a less effective search mechanism. JADEGBO, on the other hand, converges to significantly lower fitness values across most test functions, highlighting its robustness and efficiency in handling diverse optimisation challenges. The comparison confirms that JADEGBO outperforms its counterparts in terms of solution quality and convergence speed, making it a more competitive choice for complex optimisation problems.

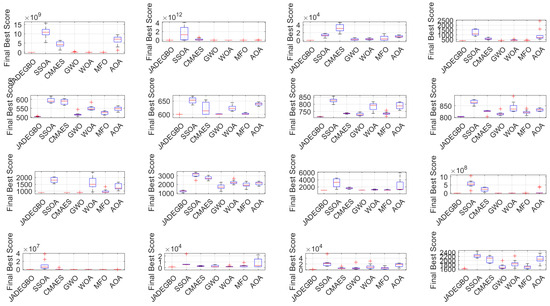

6.5. Box Plot Analysis

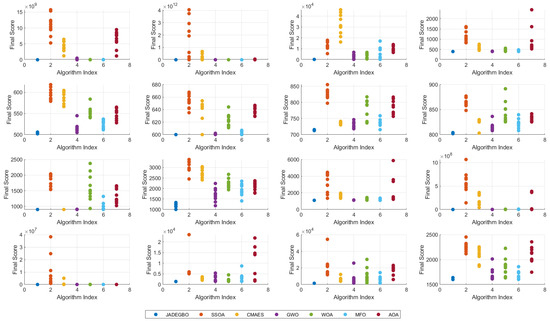

Figure 6 compares JADEGBO with several other optimisers—SSOA, CMAES, GWO, WOA, MFO and AOA—by showing box plots of the final best scores on the CEC2017 problems F1–F16. These diagrams summarise the spread and central tendency of the final objective values and thus reveal how consistent and robust each algorithm is.

Figure 6.

BoxPlot analysis of the compared optimisers over CEC2017 (F1–F16).

Across the test set, JADEGBO not only attains lower final scores than the competing methods but also exhibits tighter interquartile ranges, indicating smaller run-to-run variability. In contrast, techniques such as CMAES and MFO show wider box plots, signalling a greater dispersion in their results and hence less reliable convergence. Some algorithms, including AOA and GWO, also have higher median scores, implying that their typical solutions are less competitive than those of JADEGBO.

Taken together, the box-plot comparisons underscore JADEGBO’s strong convergence, robustness and stability across a wide range of benchmark functions, reinforcing its suitability for challenging optimisation problems.

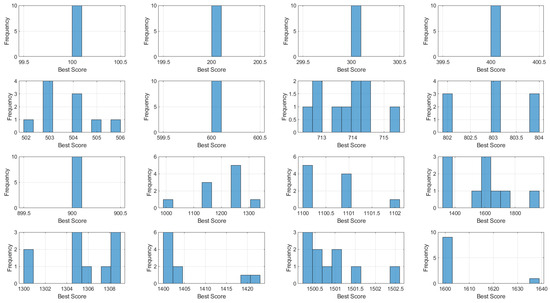

6.6. Histogram Analysis

The histograms in Figure 7 depict the distribution of the final best objective values found by JADEGBO over multiple runs on the CEC2017 test problems (F1–F16). By examining how often different scores occur, these plots shed light on the algorithm’s stability and repeatability.

Figure 7.

Histogram analysis over CEC2017 (F1–F16).

For many functions the scores are tightly clustered around a particular value, indicating that the hybrid reliably converges to the same high-quality solution from different initial conditions. In these cases the range of variation is narrow, suggesting minimal run-to-run deviation and thus a robust search process. A few problems show broader distributions, which may point to landscapes with multiple local minima or a greater sensitivity to initial starting points.

Taken as a whole, the histogram data reinforce that JADEGBO balances exploration and exploitation effectively, producing consistent outcomes across repeated trials. The observed frequency patterns demonstrate its capacity to handle complex optimisation tasks while maintaining stable performance from run to run.

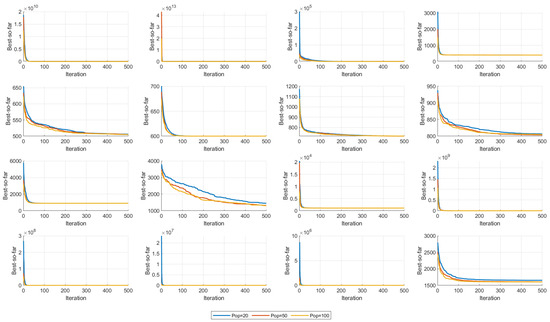

6.7. Parameter Sensitivity and Population Size

Figure 8 examines how the choice of population size affects JADEGBO’s performance on the CEC2017 functions F1–F16. The plots compare convergence behaviour for populations of 20, 50 and 100 individuals.

Figure 8.

Sensitivity analysis plot over different population size over CEC2017 (F1–F16).

Larger populations generally yield better outcomes: with 100 members, the algorithm attains lower final objective values, indicating that a broader search helps to avoid premature convergence. At the other extreme, a population of 20 converges rapidly early on but lacks the diversity needed to continue improving in later iterations. A population of 50 provides a middle ground, offering a reasonable balance between rapid progress and sufficient diversity to maintain solution quality. Moreover the Sensitivity parameter p and Pr tests are studied and the results are shown in Table 4 and Table 5 respectively.

Table 4.

Sensitivity parameter p test results.

Table 5.

Sensitivity parameter Pr test results.

6.8. Scatter Plot Analysis

Figure 9 compares the distribution of final objective values produced by JADEGBO and six other optimisers—SSOA, CMAES, GWO, WOA, MFO and AOA—on the CEC2017 problems F1–F16. By plotting each run’s final score, the scatter diagrams highlight both performance and variability.

Figure 9.

Scatter plot analysis of the compared optimisers over CEC2017 (F1–F16).

On most functions, the data points for JADEGBO lie at the lower end of the scale and are tightly grouped, signalling that the hybrid reliably finds good solutions. In contrast, methods such as CMAES and AOA show a broader spread of results, suggesting less consistent convergence behaviour. Likewise, SSOA and MFO display a wide range of final scores, indicating difficulty in maintaining stable optimisation across different problems.

These patterns support the conclusion that JADEGBO is both robust and effective across a diverse set of problems, as it consistently produces lower and more tightly clustered final scores than the competing algorithms.

6.9. JADEGBO Ablation Study on CEC2017

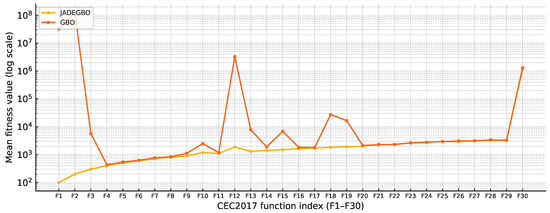

We performed an ablation by removing the JADE component from the proposed hybrid. In this setting, the method reduces to the baseline GBO, and we compare JADEGBO against GBO using CEC2017 F1–F30, 30 independent runs, 1000 iterations. Figure 10 summarises the mean fitness values across all functions (F1–F30) using a logarithmic y-axis (lower is better).

Figure 10.

Ablation study on CEC2017: Mean fitness values of JADEGBO vs. GBO over F1–F30 (30 runs, 1000 iterations). Lower is better; the y-axis is logarithmic.

The ablation results clearly show that removing JADE degrades performance across the entire benchmark set. Specifically, JADEGBOachieves lower mean fitness than GBO on all 30 functions(F1–F30), indicating that the JADE mechanism is a consistently beneficial component of the hybrid design. In terms of magnitude, the ratio of mean fitness values () ranges from approximately 1.004 on F25 (nearly tied) up to 6.24 on F2, demonstrating that the contribution of JADE is not only consistent but can be decisive on the most challenging cases.

The most pronounced improvements appear on several early and hybrid functions, where GBO exhibits severe stagnation or premature convergence relative to JADEGBO. For example, on F1 and F2, the mean fitness of GBO is orders of magnitude higher than JADEGBO (approximately times worse on F1 and times worse on F2). A similar pattern is visible on F12, where GBO is about times worse than JADEGBO. These gaps explain the strong vertical separations in Figure 10 under log scaling and highlight the importance of JADE for robust convergence on difficult landscapes.

On the remaining functions, the improvement is generally smaller but still systematic: the two curves often become closer (e.g., many composition functions), yet JADEGBO remains consistently below GBO. For instance, even on F30, where both methods yield large values, JADEGBO still reduces the mean fitness by about 12% compared with GBO. Overall, this ablation confirms that JADE plays a critical role in stabilising the search dynamir cs of the hybrid, improving both robustness and solution quality, while its removal causes the optimiser to lose these advantages and revert to the weaker behaviour of plain GBO.

7. Solving Engineering Design Problems Using JADEGBO

Efficient design in engineering often entails reducing cost, weight or material consumption while still meeting stringent structural and functional requirements. In this section, we apply the JADEGBO algorithm to four classical design optimisation problems—the welded beam, the pressure vessel, the cantilever beam, and the three-bar truss. Across these case studies, JADEGBO consistently identifies high-quality solutions with good precision and robustness and does so with a level of computational effort that is competitive with other advanced optimisation techniques.

7.1. Welded Beam Design Problem

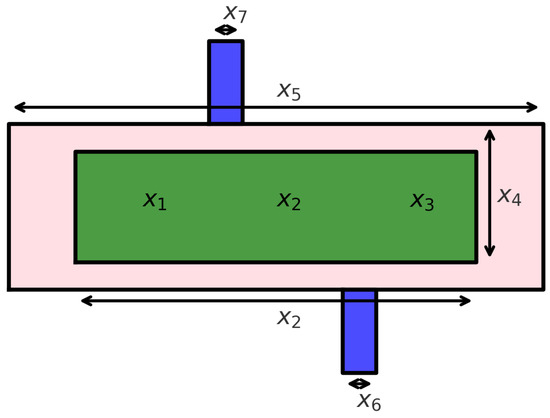

As depicted in Figure 11, this problem involves a cantilevered beam welded to a rigid support and loaded at its free end. The task is to choose the weld size and beam dimensions that use as little material as possible while still satisfying the strength and deflection constraints imposed by the applied load.

Figure 11.

Welded beam design problem.

In Table 6, the welded beam design problem results are summarised for all methods. The weighted-sum optimisation (WSO) achieves the lowest mean objective value (1.732239) and the best single run (1.681932), placing it at the top of the ranking. JADEGBO comes second, with a mean objective of 1.754827 and a best value of 1.671821; its small standard deviation (0.114762) indicates that it consistently finds high-quality solutions. The MFO algorithm follows in third place, producing a best value of 1.671448 but with greater variability across runs. Methods such as CSA, AVOA and MVO yield higher objective values, pointing to less effective optimisation. Several others—including WOA, FOX, HHO and SCA—display considerably larger averages and standard deviations, signalling unreliable convergence. Overall, the hybrid JADEGBO approach performs strongly, delivering near-optimal results with good robustness and ranking just behind WSO on this problem.

Table 6.

Welded beam design results.

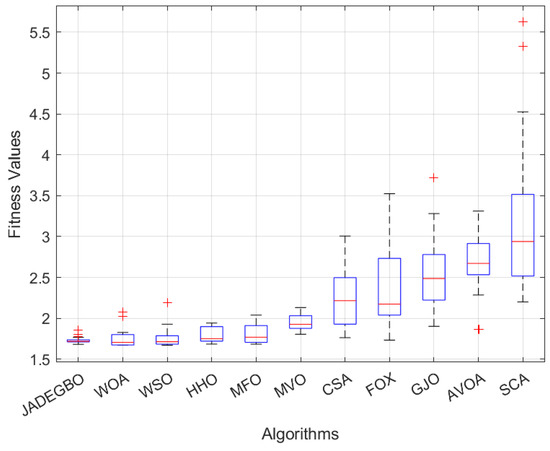

Figure 12 compares the distributions of the final fitness values for each optimiser after 100 iterations. JADEGBO stands out with the lowest median score and a very narrow spread, which implies both efficiency and stability in reaching near-optimal solutions. WOA, WSO and HHO also achieve fairly low medians, though their results vary more from run to run. At the other extreme, SCA, AVOA, and GJO produce box plots with wide interquartile ranges and numerous outliers, indicating inconsistent performance and weaker convergence.

Figure 12.

Welded beam design Boxplot results of fitness values, iterations = 100.

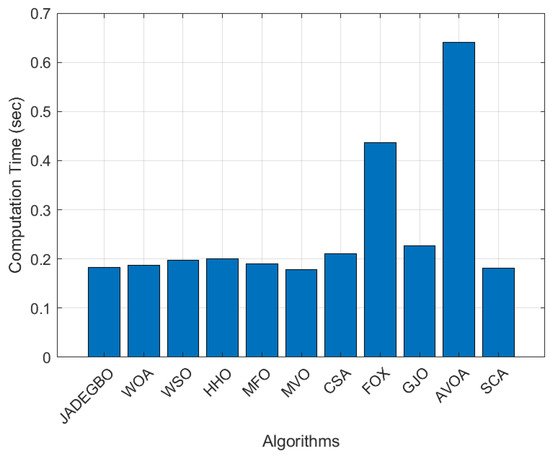

Figure 13 compares the runtime of each method over 100 iterations. JADEGBO ranks among the most efficient, taking far less time than AVOA and FOX, which are the slowest in the set. Other algorithms such as WOA, WSO, and HHO have run times comparable to JADEGBO, whereas GJO and CSA incur a modestly higher computational cost. These measurements indicate that the hybrid not only delivers strong optimisation results but does so with low overhead, making it a highly efficient choice.

Figure 13.

Welded beam design Computation time results, iterations = 100.

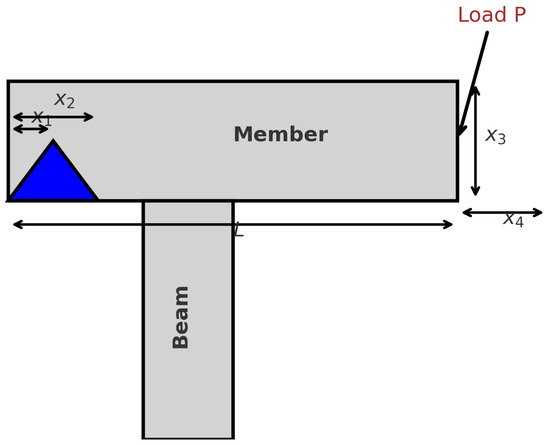

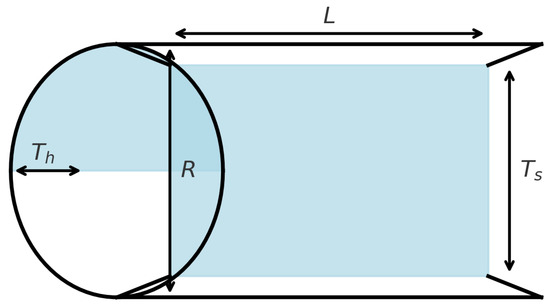

7.2. Pressure Vessel Engineering Design Problem

This classical benchmark problem seeks to minimise the total fabrication cost of a cylindrical pressure vessel capped with hemispherical heads. The design is defined by the following four variables: the shell thickness , head thickness , internal radius R, and cylindrical length L. The objective function combines material, forming and welding costs, so both the size and proportions of the vessel influence the overall expense. Because the vessel must safely contain a given volume under pressure, the optimisation must satisfy strength and capacity constraints rather than simply minimise dimensions.

Several nonlinear constraints are imposed. Stress limits on the shell and head ensure that hoop and longitudinal stresses from the internal pressure remain within allowable limits, which translates into lower bounds on and that depend on the radius. A minimum-volume requirement links R and L to guarantee the vessel can hold a specified volume. Manufacturing practice typically restricts the thicknesses to discrete increments (e.g., multiples of 0.0625 in), so the problem becomes a mixed-integer, nonlinear optimisation. This combination of cost minimisation, stress and volume constraints and discrete variables has made the pressure vessel design problem a standard benchmark for evaluating optimisation techniques in engineering.

As shown in Figure 14, the problem concerns a cylindrical shell with a hemispherical end cap used to store pressurised fluids. The key design choices involve selecting the shell and head thicknesses so that the structure safely withstands the internal stresses while keeping material and fabrication costs as low as possible.

Figure 14.

Illustration of Pressure vessel designproblem.

Table 7 compares the performance of several optimisation methods on the pressure vessel design task. JADEGBO delivers the best outcome, with a minimum objective value of 5886.65 and a low mean (6359.574) and standard deviation (392.1766), indicating both high quality and consistent solutions. AVOA and MVO place second and third, but their minima (5897.791 and 5919.194) and larger variations show they are slightly less reliable. WSO and GJO achieve respectable results yet still post higher minimum values (5941.397 and 5993.15) and greater variability. By contrast, algorithms such as HHO, CSA, SCA, FOX and WOA display much higher averages and spreads, reflecting weak convergence and poor robustness; FOX and WOA in particular show extreme variability with mean objective values exceeding 10,000. Overall, JADEGBO stands out as the most effective and stable optimiser for this pressure vessel problem.

Table 7.

Pressure vessel design comparison results.

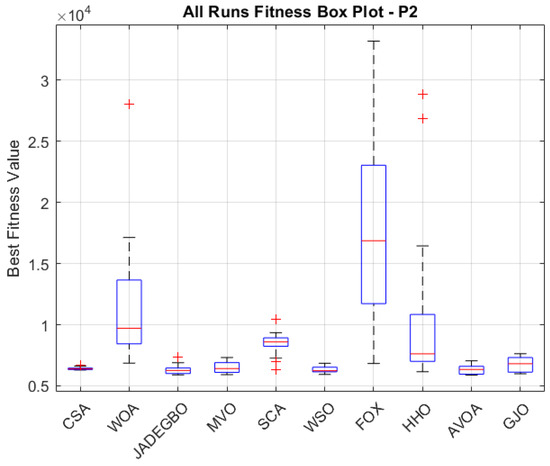

Figure 15 compares the distributions of final fitness values among the various algorithms after 100 iterations. JADEGBO is among the best performers, with a low median and a tight spread that indicate both effectiveness and robustness. CSA, MVO, and WSO also deliver respectable results, although their medians and variability are slightly higher. By contrast, FOX and HHO exhibit broad interquartile ranges and numerous outliers, pointing to erratic convergence and less reliable optimisation. WOA shows particularly large variation, underscoring its instability in achieving consistent outcomes.

Figure 15.

Pressure vessel design Boxplot results of fitness values, iterations = 100.

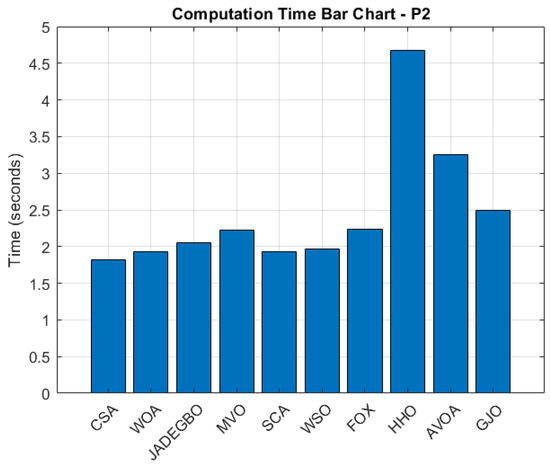

Figure 16 reports the execution time for each method. JADEGBO completes its runs in roughly the same time as CSA, WOA, and WSO, underscoring its efficiency. In comparison, HHO and AVOA require substantially more time, and both FOX and GJO also incur heavier computational costs, making them less suitable where time is limited. Taken together, these results demonstrate that JADEGBO not only produces near-optimal solutions with small variation but does so with low computational overhead, making it a reliable and efficient choice.

Figure 16.

Pressure vessel design Computation time results, iterations = 100.

7.3. Speed Reducer Design Problem

This problem involves designing a speed reducer to be as light as possible while meeting a set of structural and functional constraints. The objective function expresses the unit’s mass as a function of several design parameters: denotes the gear’s face width; the tooth module; and the number of pinion teeth. The remaining variables and are the lengths of the first and second shafts, respectively, while and are the diameters of those shafts. All dimensions are given in inches.

As shown in Figure 17, this design task involves a gearbox containing shafts that transmit torque while reducing rotational speed. Speed reducers are employed in mechanical systems to achieve lower output speeds and higher torque. Key design goals include choosing the dimensions of the housing and shafts so that the unit is durable and efficient yet economical to produce.

Figure 17.

Speed reducer design problem.

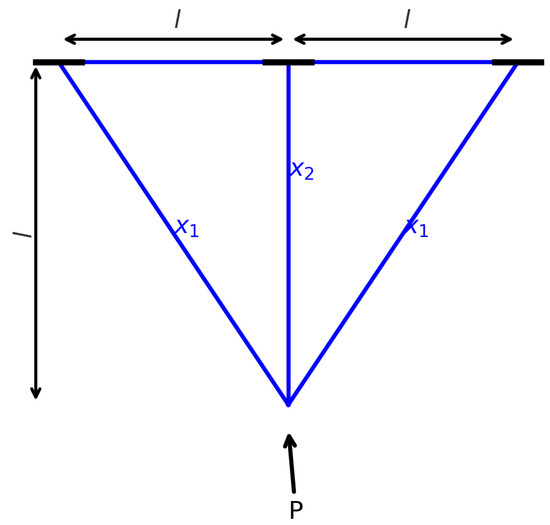

7.4. Three-Bar Truss Design

In this canonical structural optimisation task the aim is to minimise the mass of a simple three-member truss while ensuring that it can safely carry the imposed loads. The truss comprises two diagonal members and a single vertical member; the variables to be chosen are typically the cross-sectional areas (and possibly lengths) of these elements so that the structure is as light as possible without compromising stability or strength.

Engineers treat this problem as a benchmark for applying mathematical modelling and numerical optimisation to achieve a design that uses the least material for the required load-carrying capacity. As illustrated in Figure 18, the configuration consists of a triangular arrangement pinned at the apex, with an external force (P) applied at the base. By optimally selecting the dimensions and cross-sectional properties of the diagonal and vertical members, the designer seeks a balance between weight reduction and structural integrity.

Figure 18.

Three-bar truss design problem.

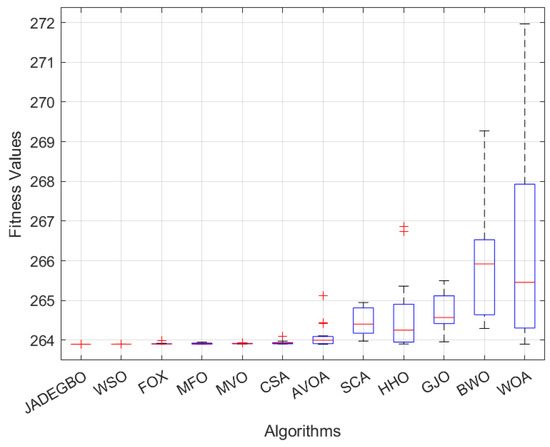

The results summarised in Table 8 show that JADEGBO achieves the lowest mean objective value (263.8959) and an almost identical best value (263.8958), with an exceptionally small standard deviation of . This indicates that it consistently finds the optimum solution. WSO produces a comparable best value but with slightly higher variability. FOX, MFO, and MVO return reasonable solutions but with greater fluctuations between runs, suggesting less stable convergence. GWO and AVOA perform worse still, exhibiting higher mean values and standard deviations. At the lower end of the ranking, SCA, HHO, GJO, BWO, and WOA show much larger mean values and wider dispersions, indicating inconsistent and unreliable behaviour. Overall, JADEGBO emerges as the most effective and robust approach for this structural optimisation problem.

Table 8.

Three-bar truss design.

Figure 19 presents the box plot analysis of the final fitness values for each optimiser after 100 iterations. The plots show that JADEGBO yields the lowest median fitness with minimal variance, indicating strong convergence and stability. WSO, FOX, and MFO also perform well, but their slightly higher medians and wider interquartile ranges point to reduced consistency. In contrast, methods such as WOA and GJO exhibit considerably higher fitness values and variability, suggesting weaker optimisation performance and a greater tendency toward suboptimal solutions.

Figure 19.

Three-bar truss design Boxplot results of fitness values, iterations = 100.

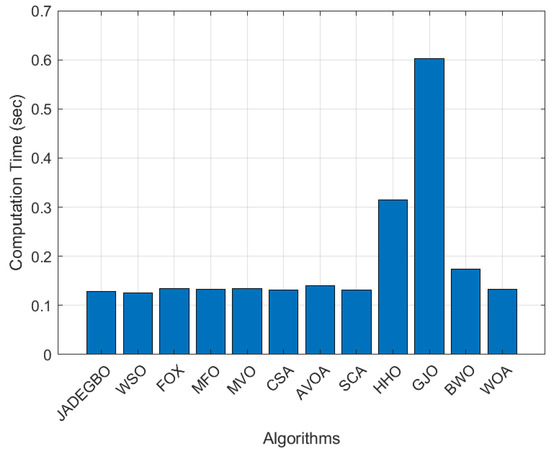

Figure 20 illustrates the computation time required by each algorithm. JADEGBO runs in roughly the same time as WSO, FOX, and MFO, demonstrating its computational efficiency. However, algorithms like HHO and GJO require substantially more time, making them less attractive for practical use. Most of the remaining methods demand only moderate computational effort, but the results clearly highlight that JADEGBO attains high-quality solutions with low variance while keeping computation costs minimal. Overall, JADEGBO proves to be a highly effective and efficient optimiser for complex optimisation problems.

Figure 20.

Three-bar truss design Computation time results, iterations = 100.

8. Conclusions

This paper introduced JADEGBO, a hybrid optimisation algorithm that combines the adaptive, population-based search of JADE with the gradient-inspired refinement mechanisms of the Gradient-Based Optimiser (GBO). In the proposed framework, JADE first explores the decision space using p-best mutation, external archiving, and success-based parameter adaptation, thereby locating promising regions and preserving population diversity. GBO is then invoked as a second phase to intensify the search around these regions using gradient-like search rules and a local escaping operator, which helps to accelerate convergence and avoid stagnation in local minima.

Extensive experiments on the CEC2017 benchmark suite demonstrate that the hybrid approach is highly competitive. Across thirty functions and a wide range of landscape characteristics, JADEGBO generally achieves the best or near-best mean objective values and exhibits small standard deviations when compared with a diverse portfolio of classical and state-of-the-art metaheuristics. Convergence curves show fast initial descent followed by stable refinement, box plots and histograms highlight strong robustness and low variability, and sensitivity analysis with respect to population size confirms that the algorithm maintains good performance over a broad range of configurations. These observations support the claim that the sequential combination of JADE’s adaptive exploration with GBO’s gradient-based exploitation yields a well-balanced search dynamics.

The applicability of JADEGBO was further examined on several constrained engineering design benchmarks, including welded beam, pressure vessel, speed reducer, and three-bar truss problems. In these case studies, the hybrid optimiser consistently produced high-quality feasible designs, closely matching or improving upon the best-known solutions reported for these problems, while maintaining competitive computation times. The results on welded beam and three-bar truss design in particular underline the algorithm’s ability to handle tightly constrained structural problems without excessive parameter tuning.

Several avenues for future work emerge from this study. On the algorithmic side, it would be interesting to investigate adaptive or problem-dependent switching policies between JADE and GBO, multi-strategy pools that select variation operators online, and extensions to multi-objective, dynamic, and discrete optimisation. On the application side, larger-scale industrial case studies, reliability-based design, and more complex cyber-security scenarios (such as joint attack–response planning or multi-threshold IDS calibration) could further test and refine the method. Overall, the results obtained so far suggest that JADEGBO is a promising, general-purpose optimiser for challenging engineering and security-oriented optimisation problems, offering a favourable combination of solution quality, robustness, and computational efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z., R.A., Z.K., F.H., N.H. and H.F.; Methodology, J.Z., F.H., N.H. and H.F.; Software, J.Z., R.A., F.H., N.H. and H.F.; Validation, Z.K.; Formal analysis, R.A., Z.K. and F.H.; Investigation, R.A., Z.K., N.H. and H.F.; Resources, R.A., Z.K. and N.H.; Data curation, F.H.; Writing—original draft, J.Z., R.A., Z.K., F.H., N.H. and Hussam Fakhouri; Writing—review and editing, J.Z., F.H., N.H. and H.F.; Visualization, J.Z., F.H. and H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Engineering Design Optimization Equations

- Weld beam engineering design equations

In this optimization problem, the aim is to minimise the fabrication cost of a welded beam subject to structural and geometric constraints. The design vector consists of the weld thickness , the weld length , the height of the beam’s cross-section , and the thickness of that cross-section , all in inches. The total cost to be minimised is defined by Equation (A1), expressed as follows:

where the first term corresponds to the cost of welding, and the second term represents the cost of the beam material. The problem involves the following parameters: applied load lb, beam length in, Young’s modulus psi, shear modulus psi, maximum shear stress = 13,600 psi, maximum normal stress 30,000 psi, and maximum deflection in.

The constraints are derived from stress, deflection, and geometric considerations. The shear stress at the weld is defined as seen in Equation (A2), expressed as follows:

where the following hold:

The normal stress is calculated as shown in Equation (A3), expressed as follows:

and the deflection is given by Equation (A4), expressed as follows:

Additionally, the buckling load constraint is as seen in Equation (A5), expressed as follows:

The constraints include the following:

Each constraint is evaluated, and penalty terms are applied to the objective function when constraints are violated. The penalised objective function is as seen in Equation (A6), expressed as follows:

where if , and otherwise. This ensures that constraint violations heavily penalise the objective function.

- Pressure Vessel Design Problem

The objective function quantifies the total cost of constructing the pressure vessel, which encompasses material and welding costs. It is expressed as Equation (A7), expressed as follows:

where the decision variables are defined as seen in Equation (A7), expressed as follows:

- x1: Thickness of the shell (integer multiple of 0.0625 inches),

- x2: Thickness of the head (integer multiple of 0.0625 inches),

- x3: Inner radius of the pressure vessel (inches),

- x4: Length of the cylindrical section of the vessel (inches, excluding the head).

To address constraint violations, a penalty-based optimisation approach is adopted. The penalised objective function incorporates penalties for infeasible solutions and is defined as shown in Equation (A16), expressed as follows:

where is a binary variable indicating the violation of the i-th constraint, expressed as follows:

- Speed Reducer Design Problem

The objective function is mathematically expressed as seen in Equation (A18) as follows:

This design problem is governed by a set of eleven constraints, ensuring that the solution adheres to design and safety standards. These constraints are expressed as shown in Equations (A19)–(A22), expressed as follows:

A penalty-based optimisation approach is utilised to handle constraint violations, where a penalty term is added to the objective function for infeasible solutions. The penalised objective function is defined as seen in Equation (A23), expressed as follows:

where is a binary indicator variable that equals 1 if (i.e., the constraint is violated) and 0 otherwise. This ensures that the optimisation process discourages infeasible solutions by imposing a high penalty cost for each violated constraint.

- Three-bar truss design

The three-bar truss is a classic structural optimisation problem in which the aim is to minimise the mass of a simple three-member truss while ensuring it can safely carry the prescribed loads. The structure is composed of two diagonal members (with cross-sectional area ) and one vertical member (with area ). The task is to choose these cross-sectional areas so that the truss is as light as possible without compromising its structural integrity.

The objective function for this problem represents the total weight of the truss and is given by Equation (A24), expressed as follows:

where represents the cross-sectional area of the two diagonal members, and represents the cross-sectional area of the vertical member. The goal is to minimise , which corresponds to reducing the material used in constructing the truss.

To ensure structural integrity and stability, the design must satisfy the following constraints, as expressed Equations (A25)–(A27):

These constraints ensure that the stress in each truss member remains within allowable limits. The optimisation process involves finding values for and that minimise the objective function while satisfying all constraints. If any constraint is violated, a penalty is applied to enforce feasibility. By adjusting the cross-sectional areas, the truss can be designed to be both lightweight and structurally sound.

Appendix B. Wilcoxon Sum Rank Test

Table A1.

Wilcoxon sum rank test results part 1.

Table A1.

Wilcoxon sum rank test results part 1.

| Fun | GBO | FLO | AO | RSO | SHO | RIME | SCSO | DOA | ZOA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 2.36E-12 | 2.36E-12 | 2.91E-07 | 2.36E-12 | 2.36E-12 | 2.36E-12 | 2.36E-12 | 2.36E-12 | 2.36E-12 |

| U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 611.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | |

| + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| F2 | 1.58E-11 | 1.58E-11 | 0.178254 | 1.58E-11 | 1.09E-09 | 1.58E-11 | 1.25E-07 | 1.58E-11 | 0.000804 |

| U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 837.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 508.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 562.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 691.0000 | |

| + | + | = | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| F3 | 1.24E-11 | 1.24E-11 | 1.24E-11 | 1.24E-11 | 1.24E-11 | 1.24E-11 | 1.24E-11 | 1.24E-11 | 1.24E-11 |

| U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | |

| + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| F4 | 2.84E-11 | 2.84E-11 | 0.00061 | 2.84E-11 | 2.84E-11 | 2.84E-11 | 2.84E-11 | 2.84E-11 | 2.84E-11 |

| U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 683.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | |

| + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| F5 | 1.21E-12 | 1.21E-12 | 0.001365 | 1.21E-12 | 1.21E-12 | 1.21E-12 | 1.21E-12 | 1.21E-12 | 1.21E-12 |

| U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 780.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | |

| + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| F6 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 | 0.53951 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 |

| U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 873.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | |

| + | + | = | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| F7 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 | 2.67E-09 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 |

| U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 512.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | |

| + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| F8 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 | 0.000587 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 | 3.02E-11 |

| U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 682.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | |

| + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| F9 | 1.21E-12 | 1.21E-12 | 0.333711 | 1.21E-12 | 1.21E-12 | 1.21E-12 | 1.21E-12 | 1.21E-12 | 1.21E-12 |

| U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 900.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | U: 465.0000 | |

| + | + | = | + | + | + | + | + | + | |