Abstract

To address the challenges of interdependent design parameters and reliance on empirical trial-and-error in ultrasonic cell levitation culture devices, this study proposes a top-down design framework integrating multi-physics modeling with complex network analysis. First, acoustic field simulations optimize transducer arrangement and define the cell manipulation field, establishing the Top-level Basic Structure (TBS). A skeleton model of the acoustofluidic coupled field is constructed based on the TBS. Core parameters are then determined by refining the TBS through multi-physics analysis. Second, a 24-node design change propagation network is constructed. Leveraging the TBS model coupled with multi-physics fields, a directed network model analyzes parameter interactions. The HITS algorithm is applied to prioritize the design sequence based on authority and hub scores, resolving parameter conflicts. Experimental validation demonstrates a device acoustic pressure of 1.3 × 104 Pa, stable cell levitation within the focused acoustic field, and a 40% reduction in design cycle time compared to traditional methods. This framework systematically sequences parameters, effectively determines the design order, enhances design efficiency, and significantly reduces dependence on empirical trial-and-error. It provides a novel approach for developing high-throughput organoid culture equipment.

1. Introduction

Cell culture is a fundamental technique crucial for biomedical research and cell therapy. However, conventional methods suffer from limitations such as uneven contact between cells and culture medium, and cell aggregation induced by gravity, which impede optimal cell growth and functional maintenance.

Ultrasonic levitation cell culture technology addresses these issues by utilizing acoustic radiation forces generated by ultrasound waves to stably suspend cells within a liquid medium. This approach provides a more uniform culture environment. The technology not only promotes cell growth, differentiation, and metabolism but also demonstrates broad application prospects. Moderate-intensity ultrasound exhibits excellent biocompatibility and multifunctionality, making it an ideal non-contact cell manipulation tool [1]. Specifically, ultrasonic standing waves create pressure nodes and antinodes within the liquid, enabling precise guidance for cell aggregation or separation. This capability facilitates high-density cell self-assembly [2] and induces the formation of specific three-dimensional (3D) structures such as brain-like cortices, cardiac tissues, or ring-shaped constructs [3]. Furthermore, the pressure gradients generated by ultrasound in the liquid phase can effectively simulate microgravity conditions, promoting the suspension culture of organoids to meet diverse cultivation requirements [4]. Phased-array ultrasound technology, based on piezoelectric ceramic arrays, can generate standing waves and pressure gradients through phase modulation. The biological efficacy and safety of ultrasonic manipulation are critically dependent on the operating parameters, such as frequency, pressure amplitude, and exposure time [5]. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound (LIPUS) regimes, typically characterized by low pressure amplitudes and controlled duty cycles, have been widely explored for therapeutic and biomodulatory applications due to their excellent biocompatibility. These parameters must be carefully selected to avoid adverse effects on cell viability, motility, or genetic integrity while achieving the desired physical manipulation. Recent advances in acoustofluidics further demonstrate the feasibility of using repeated low-intensity ultrasound pulses for sustained biological manipulation, such as maintaining sperm motility over extended periods without compromising cell health [6]. Therefore, defining an appropriate operating window that is both effective for levitation and biologically benign is paramount for cell culture applications. This allows for the construction of large-scale 3D cellular patterns to mimic complex tissue architectures.

Despite the significant potential of ultrasound technology in organoid culture, current research still faces several critical scientific challenges. The primary obstacle lies in the fact that the mechanisms underlying ultrasound’s effects on organoids have not been fully elucidated. Concurrently, the design parameters of levitation devices—such as acoustic field distribution, frequency, and power—significantly influence suspension performance, making the precise determination of their values crucial. Within mechanical products, complex interrelationships exist between components and subsystems, leading to intricate interdependencies among design parameters. During the initial design phase of a product developed from scratch, key design parameters are often undefined and must be progressively determined as the design evolves. This sequential definition can necessitate systemic adjustments later in the process, potentially delaying design progress.

The Top-Down Design (TDD) methodology, which supports innovative design, offers an effective approach to address this challenge. TDD begins with the overall system concept and progressively decomposes and refines the design down to fundamental components. This strategy facilitates the early identification and definition of key parameters, thereby preventing issues such as late-stage iterative modifications, system integration difficulties, reduced design efficiency, and poor controllability, robustness, and adaptability. Currently, TDD has found widespread application in the field of intelligent product design.

A key implementation of the TDD philosophy in mechanical design is the Top-level Basic Structure (TBS) model, which utilizes a central “skeleton” to control the entire assembly. This study adopts the TDD approach and employs the TBS model to first establish a top-level design framework. For instance, Liu et al. proposed a systematic framework supporting the top-down design of platforms and product families, enabling the generation and optimization of product configurations with appropriate commonality [7]. Shi et al. [8] introduced a stiffness modeling and stiffness matching design method for precision machine tools incorporating a skeleton model stage. This achieved a top-down stiffness design, and its reliability and versatility were validated through finite element analysis and experiments. He et al. [9] proposed an integrated design and analysis method based on parametric design principles, incorporating a skeleton model. Using the integrated design and analysis of an offshore crane as an example, they demonstrated that this method contributes to shortening the design cycle and improving design quality.

Adopting the TDD approach, this study first proposes a top-level design model for the fundamental structure (TBS), aiming to streamline the design process. Building upon this model, complex physical fields are subsequently introduced to simulate actual operating conditions, establishing a multi-physics improved TBS model. This refined model enables the determination of critical design parameters under specific environmental constraints. Crucially, interdependencies exist among different design parameters. To avoid interference during parameter value assignment, a clear design sequence must be established (e.g., bearing design typically requires shaft diameter determination first). However, systematically establishing this sequence across numerous parameters presents a significant challenge, and research in this area remains notably insufficient.

2. Establishment of the TBS Model for the Ultrasonic Levitation Device

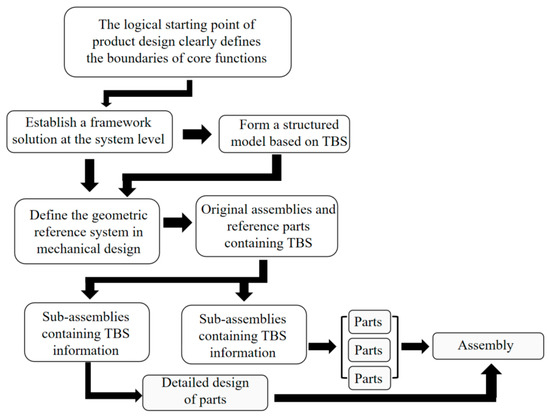

In the product design workflow based on the Top-Down By Skeleton (TBS) model, the top-down design philosophy permeates the entire process. During the initial design phase, the fundamental functional requirements of the product drive the construction of a top-level TBS skeleton model. This model defines the core spatial layout, morphology, and topological relationships between sub-modules [10]. Serving as the starting point for the entire design process, this TBS skeleton provides the foundational framework and reference datum for the subsequent design of sub-modules.

In the downstream stages of the design workflow, assembly reference elements within the TBS skeleton—such as datum points, axes, and planes—directly guide the creation and assembly of components. Design parameters for each component are linked to the top-level TBS skeleton. This approach eliminates the complex cross-references, mutual fittings, and alignment operations often required in traditional component-based design [11]. Consequently, assembly is simplified, and component design and modification become more straightforward, facilitating component optimization and innovation throughout the process. Furthermore, since the TBS skeleton resides at the top level of the design hierarchy, adjustments to its assembly references during product innovation or subsequent iterations can drive design changes in the components (e.g., optimizing dimensions and positions). This skeleton-based change propagation imposes necessary constraints on the components, ensuring that the assembly model remains stable and avoids failure even during frequent design iterations. This mechanism guarantees the efficiency and flexibility of the overall design process [12]. Integrating the TBS design model into the workflow significantly enhances the efficiency and quality of product design, boosts flexibility and innovation, and provides robust support for complex product development.

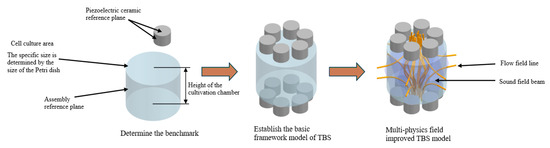

Applying the TBS methodology to design the ultrasonic levitator begins with establishing a top-level skeleton model tailored to the requirements of the ultrasonic transducers. Considering the influence of multi-physics fields, particularly the acoustic field, this study introduces a fundamental skeleton model at the top level that incorporates both the acoustic field and the mechanical structure. This model serves as the reference framework for optimizing the levitator design (the TBS design workflow is illustrated in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

TBS design process.

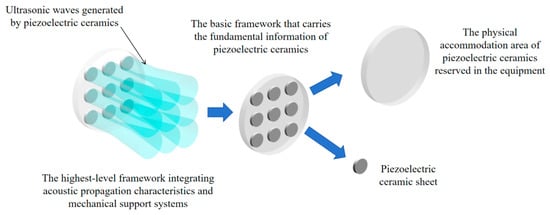

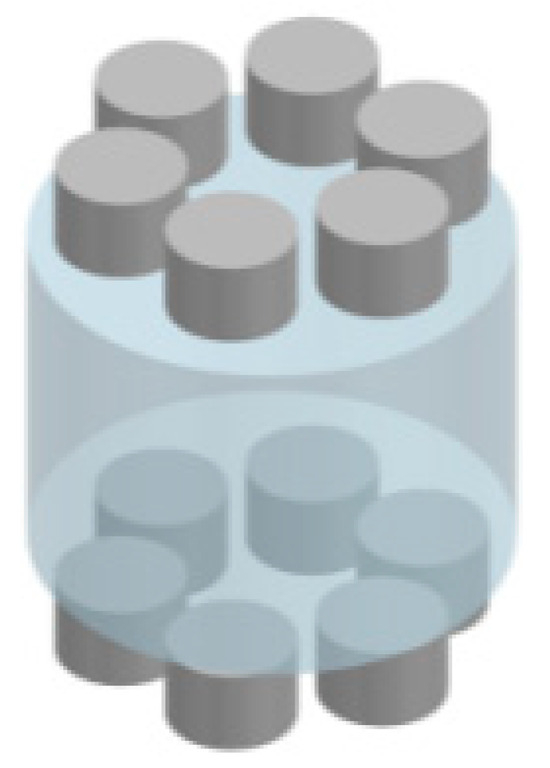

Following this workflow, a TBS model conforming to the design of the piezoelectric ultrasonic transducer must be established. The piezoelectric ceramic, as the core component of the transducer, generates the crucial ultrasonic waves. Therefore, the TBS skeleton must encapsulate fundamental information about the piezoelectric ceramics, including their dimensions, shape, installation positions, and array configuration. Furthermore, the characteristics of the ultrasonic beam generated by the piezoelectric ceramics are critical to transducer performance; hence, these beam characteristics must also be incorporated into the fundamental skeleton. Integrating the piezoelectric ceramic information and the ultrasonic beam characteristics enables the construction of a TBS model containing acoustic field information (as depicted in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the construction of the sound field TBS model.

Acoustic pressure is a key physical quantity characterizing the sound field; its distribution is determined by the configuration of the piezoelectric ceramic array. Consequently, the fundamental parameters of the piezoelectric ceramics (dimensions, positions, layout) must be determined based on the required acoustic pressure distribution for the specific application. Figure 2 schematically shows a model incorporating nine piezoelectric ceramics, including the ultrasonic beams they generate and their spatial installation positions. These parameters (dimensions, shape, position, layout) are adjustable according to practical requirements, endowing the TBS model with adaptability and flexibility. By comprehensively considering the coordination between acoustic field characteristics and geometric constraints, a unified design standard for the ultrasonic transducer is established within the skeleton. This standard facilitates efficient information transfer and change propagation during the subsequent detailed design stages.

Given that the product involves multiple component design parameters that may exhibit interdependencies, relying solely on orthogonal experimental testing for iterative parameter optimization would impede design efficiency and prolong the development cycle. The proposed method addresses this by establishing a foundational skeleton framework. Building upon this top-level architecture, it provides a clear design pathway and accelerates the subsequent parameter optimization process and the integration of the acoustic field model under coupled physical fields.

To establish the fundamental simulation model for the ultrasonic levitation skeleton, the initial step involved determining the piezoelectric ceramic array configuration. Piezoelectric ceramics with a frequency of 40 kHz, diameter of 10 mm, and thickness of 10 mm were employed. With acoustic radiation force as the optimization objective, the array arrangement for the ultrasonic levitator TBS was optimized.

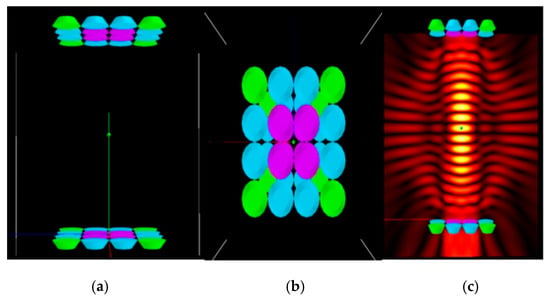

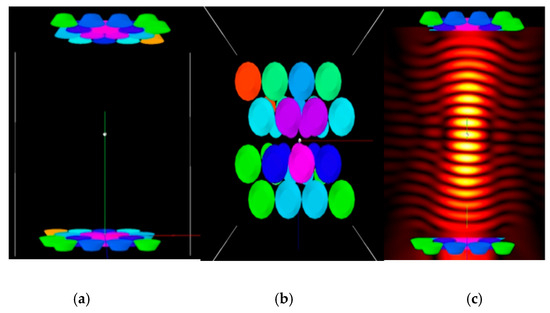

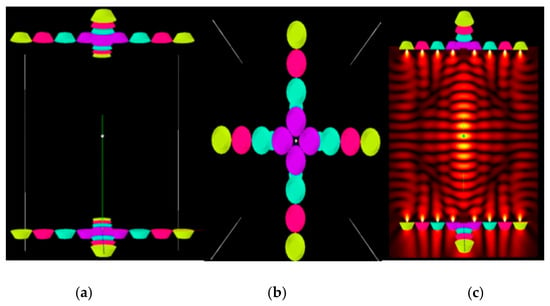

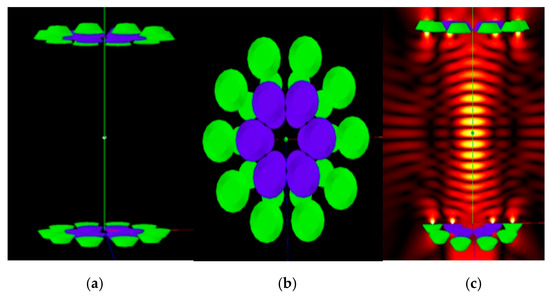

The main body of the TBS suspension device is a cylindrical culture zone that is 80 mm high. This study designed and simulated four different transducer array configurations: annular, square, honeycomb, and radial (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6). For each configuration, the acoustic radiation force at the target levitation point was calculated through acoustic field simulation to select the best array scheme based on the TBS levitation device.

Figure 3.

Square array and its sound field. (a) Square array front view; (b) Square array top view; (c) Square array sound field distribution cloud map.

Figure 4.

Cellular array and its sound field. (a) Cellular array front view; (b) Cellular array top view; (c) Cellular array sound field distribution cloud map.

Figure 5.

Radial array and its sound field. (a) Radial array front view; (b) Radial array top view; (c) Radial array sound field distribution cloud map.

Figure 6.

Circular array and its sound field. (a) Circular array front view; (b) Circular array top view; (c) Circular array sound field distribution cloud map.

Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6, respectively, show the detailed layout and sound field characteristics of four arrays: among them, subfigures (a) and (b) are the front view and top view of the arrays, respectively. The color of the transducer in the figure represents the driving phase required to generate constructive interference at the target focus point. Subgraph (c) is the cloud map of the sound field distribution generated by each array under the corresponding phase drive.

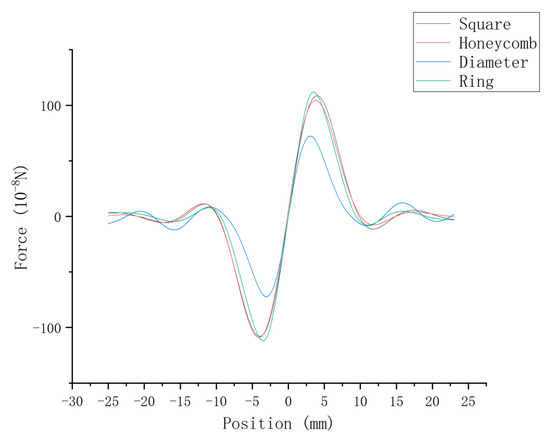

As shown in Figure 7, the ring-shaped array configuration yields the maximum acoustic levitation force along the X-axis. Furthermore, this configuration provides balanced forces along all three axes, resulting in more stable levitation performance. Therefore, the ring-shaped configuration was selected as one of the fundamental design parameters for the TBS.

Figure 7.

Acoustic radiation maps under the four arrangements.

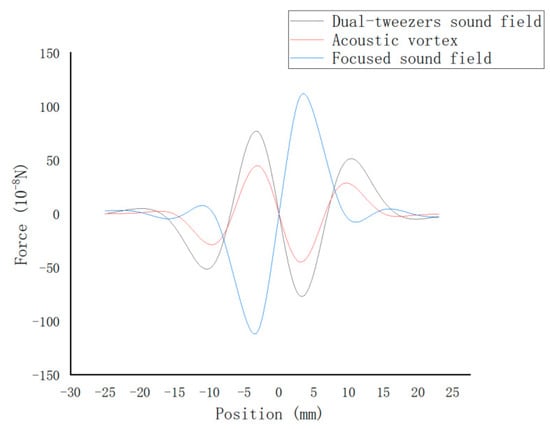

Building upon this TBS model, the study investigated four primary acoustic manipulation modes under this simulation framework: standing wave, focused beam, acoustic tweezers (dual-trap), and acoustic vortex with a topological charge of 1. While standing wave fields excel at stable levitation at pressure nodes—primarily advantageous for cell separation due to their stability—they are less suitable for aggregate culture and complex cell manipulation. Consequently, the acoustic levitation forces were compared only for the other three acoustic field types. The simulated acoustic fields for these three distinct manipulation modes are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Three different sound control sound fields.

As shown in Figure 9, the results indicate that acoustic focusing exerts the maximum suspending force on the particles. Therefore, the subsequent simulation adopts the focused suspension mode as the main acoustic manipulation scheme for optimizing the physical field parameters of liquid suspension.

Figure 9.

Acoustic radiation force under three acoustic control modes.

Based on the finalized top-level design described above, the schematic diagram of the fundamental TBS skeleton model is presented below (Figure 10). Note that the specific design parameters within this top-level skeleton will be determined in subsequent stages.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of the basic TBS model.

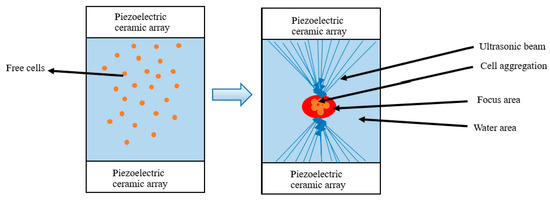

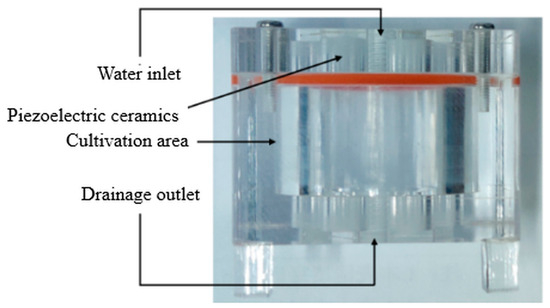

3. Establishment of the Multi-Physics Improved TBS Model

The levitation device utilizes ultrasound to enable container-free culture and manipulation of cellular particles within a liquid medium. Under the influence of the focused acoustic field, cells gradually converge and coalesce towards the focal point, ultimately achieving stable suspension within the focal region. During culture, nutrient-rich medium essential for cell growth is continuously perfused into the system via a fluidic pump, while cellular metabolites are concurrently removed via the outflow. A schematic diagram illustrating the typical structure and functionality of this device is presented below (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of ultrasound-focused suspension culture cells.

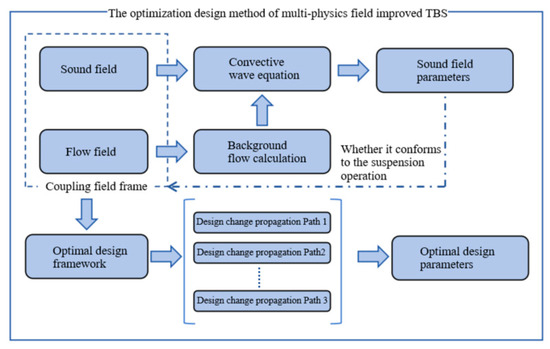

The fundamental skeleton model (TBS model) established previously provides an overarching framework that lays the groundwork for subsequent optimization. However, the introduction of multi-physics fields significantly increases the number of design parameters and their interrelationships, with some parameters exhibiting inherent constraints or conflicts. Consequently, the specific parameters within the top-level skeleton require further refinement, and interactions among different design parameters may lead to interference. To avoid iterative revisions or even complete redesigns due to design contradictions, it is crucial to analyze the propagation paths of design changes and rationally plan the overall design workflow within complex systems.

To address this challenge, this paper proposes an enhanced design path planning methodology. This approach builds upon the refined top-level architecture (i.e., the multi-physics enhanced TBS model) and incorporates design change propagation analysis. Its core principle is: By utilizing the enhanced TBS model to manage top-level parameters and constraints, while simultaneously employing change propagation analysis to identify dependencies and potential conflicts among parameters, the design steps can be scientifically planned. This ensures both efficiency and robustness throughout the design process. The framework of this enhanced optimization approach is depicted in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Overall multi-physics field optimization scheme of the improved TBS based on design change propagation.

Since the device is designed for cell culture in liquid media, its development must account for multi-physics coupling effects, particularly the interaction between the acoustic field and flow field. Therefore, we employ the multi-physics improved TBS model (Figure 13) to conduct comprehensive design analysis under these coupled operating conditions.

Figure 13.

Multi-physics field improved TBS model.

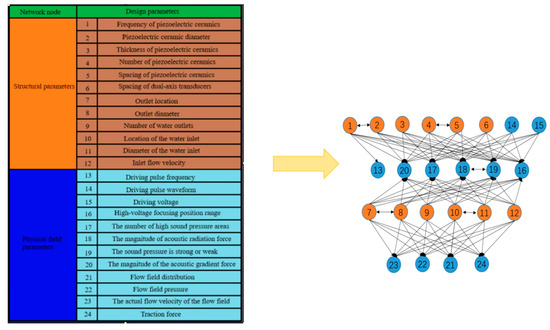

On this basis, the specific values of the final design parameters were determined. The original design parameters of the multi-physics field enhanced TBS model were combined with the new parameters introduced by the liquid environment to establish a complete set of the required design parameters, as shown in the table in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Design of network model for the propagation of parameter changes.

Given the large number of parameters, adhering to a rational design sequence is paramount. This approach not only enhances design efficiency but also ensures the achievement of a near-optimal solution while satisfying all requirements.

To quantitatively analyze the interdependencies among these parameters, this study constructed a directed design change propagation network model. In this network: Nodes represent the 24 critical design parameters identified from the multi-physics improved TBS model (as listed in the table in Figure 14). Directed Edges represent the propagation of design changes and constraints between parameters. Specifically, a directed edge from node A to node B is established if a change in the value of parameter A directly imposes a constraint on, or necessitates a re-calculation of, parameter B. These dependency relationships were rigorously derived from the coupled physical laws (acoustics, fluid dynamics) and geometric constraints embedded within our multi-physics TBS model. This resulted in a network comprising 24 nodes and 105 directed edges, whose structure is illustrated in Figure 14. For instance, ‘Driving Frequency’ (a high-hub parameter) influences ‘Acoustic Radiation Force’ and ‘Sound Pressure Magnitude’ (high-authority parameters). Using HITS, we prioritize setting the frequency first. This prevents a scenario where we first calculate a desired radiation force, only to find later that no available driving frequency can achieve it, thus avoiding a design conflict and iterative backtracking.

4. Path Planning for the Multi-Physics TBS Model with Design Change Propagation

The design of this device involves numerous components and multi-physics parameters exhibiting complex interdependencies. An ill-defined design sequence risks causing interference with previously determined parameters after their completion. This can trigger cascading modifications, severely compromising design efficiency. Therefore, rationally planning the parameter design sequence is paramount for enhancing overall design efficiency.

Furthermore, traditional design change propagation analysis typically operates on existing designs. To prevent triggering large-scale propagation (“avalanche effect”), paths with excessively broad impact (affecting numerous components) are often deliberately avoided [13]. However, in the TBS methodology applied to novel product development (from concept to realization), the inherent relationships between components dictate that design information propagates along predefined paths within the TBS skeleton [14]. Leveraging this intrinsic propagation mechanism enables the analysis of potential information flow routes during the initial design phase. This facilitates optimized workflow design, improved efficiency, and aids in screening optimal design solutions.

Contrary to traditional change avoidance strategies, the goal during the initial TBS design phase is to maximize the coverage of design information propagation paths within a single design activity (i.e., determining more interrelated parameters simultaneously). This strategy aims to minimize iterative workload. Achieving this requires identifying and prioritizing design steps capable of covering broader propagation paths.

To analyze this design change propagation network and plan the design sequence, this study employs the HITS algorithm (Hyperlink-Induced Topic Search) [15]. As a core algorithm for network node importance assessment, HITS offers a unique advantage through its dual-weighting model (Authority score and Hub score), making it particularly suitable for design parameter prioritization analysis [16].

Assuming matrix M represents the stabilized adjacency matrix of nodes in the network, A denotes the column vector composed of Authority scores for all nodes, and H denotes the column vector composed of Hub scores, each iteration cycle strictly follows the computational sequence: Authority scores are calculated prior to Hub scores.

Following each iteration, calculating hub and authority scores, the hub and authority vectors undergo normalization to unit length (typically using the L2-norm). This normalization serves a dual purpose: Firstly, it eliminates scale differences across dimensions, ensuring equitable computation. Secondly, it significantly accelerates algorithm convergence. The process of updating the scores (weight computation) followed by normalization is then repeated iteratively.

Algorithm convergence is assessed by measuring the difference between the weight vectors from the previous iteration and the newly computed vectors. This is typically quantified using metrics such as the Euclidean distance or the norm of the difference vector. If the overall change in weights falls below a predefined threshold, the system is considered stable, indicating that the weights have converged. At this point, the iteration process terminates.

The final output of the algorithm is generated by ranking all nodes in descending order based on their converged authority scores. The top-ranked nodes (those with the highest authority scores) are then returned as the key design parameters [17].

Following the definition of nodes and edges for the multi-physics TBS model in Figure 12, the HITS algorithm was employed for design path planning. Node importance within the network was evaluated based on dual metrics: Authority and Hub scores. Link weights between nodes were calculated using the Depth-First Search (DFS) algorithm. The computational results are presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Node authority values.

Table 2.

Hub values of nodes.

High-authority parameters (Authority score > 0.12) identified include piezoelectric ceramic thickness, piezoelectric ceramic diameter, driving voltage, and acoustic radiation force magnitude. These parameters constitute the core structural framework of the system and were prioritized for initial determination. Piezoelectric Ceramic Thickness and Diameter: These parameters required co-optimization. Constrained by the physical dimensions of the cultivation device, the piezoelectric ceramic diameter was set to 10 mm. Finite element analysis of piezoelectric disk vibration modes [18] indicates an optimal thickness-to-diameter ratio range of 0.1–0.3. Consequently, a thickness of 2 mm was selected (ratio = 0.2). Driving Voltage: Experimental analysis revealed that a 10 V increase in driving voltage enhances sound pressure by 15% but concurrently increases power consumption by 25%. Balancing these effects, a driving voltage of 20 V was selected for the device. Acoustic Radiation Force: Directly influencing levitation capability, this parameter serves as a key performance metric and was designated for calculation in subsequent simulation stages. Consequently, nodes 3, 2, 15, and 18 were determined based on these selections.

In the subsequent design phase for high-hub parameters (Hub Score > 0.10)—namely, flow configuration, driving frequency, and domain-wide flow velocity—the flow configuration was primarily determined by inlet and outlet parameters; adhering to the inherent symmetry of the TBS device, these were designed symmetrically with identical parameters. To compensate for diminished lateral acoustic control due to the top/bottom piezoelectric ceramic arrangement and optimize acoustic field coupling, inlets were positioned centrally on the top and bottom end faces, with a diameter of 4 mm selected to minimize spatial footprint, while the inlet flow velocity for cell cultivation was set to 0.15 μL/s [19]. Accounting for acoustic field coupling, domain-wide flow velocity was computed using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) to determine the complete velocity distribution and associated physical parameters. Optimal resonant operation required matching the driving frequency to the inherent resonant frequency of the piezoelectric ceramics, which was consequently determined concurrently; comparative COMSOL(6.2) Multiphysics simulations under coupled acoustic-fluid conditions evaluated elements operating at 0.5 MHz and 275 kHz, with final frequency selection based on performance metrics, thereby establishing nodes 1, 21, 23, and 7–13.

Balanced parameters (scoring 0.08–0.12) include the number of high-pressure zones, sound pressure magnitude, and inlet flow velocity. The number of high-pressure zones is jointly influenced by piezoelectric ceramic spacing and operating frequency. Given the frequency was previously established, the literature [20] indicates that minimizing piezoelectric spacing is optimal to maximize the number of elements. Considering the annular piezoelectric arrangement in the TBS model and practical cultivation area constraints, a three-concentric-ring configuration was adopted with an inter-ring spacing of 15 mm, resulting in 56 piezoelectric elements (28 per layer). The inlet flow velocity was concurrently determined during the preceding inlet design phase. Both high-pressure zones and sound pressure magnitude are computationally derived from final acoustic field contour plots, thereby establishing nodes 4, 5, 17, and 19.

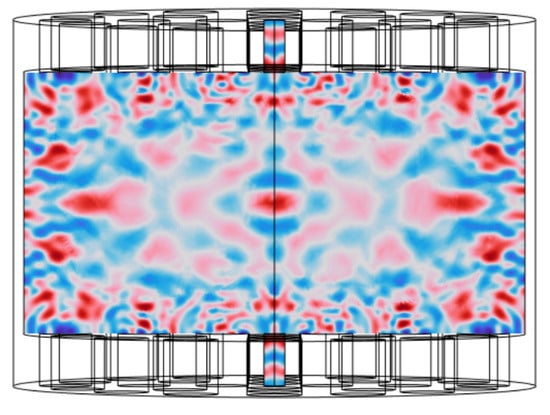

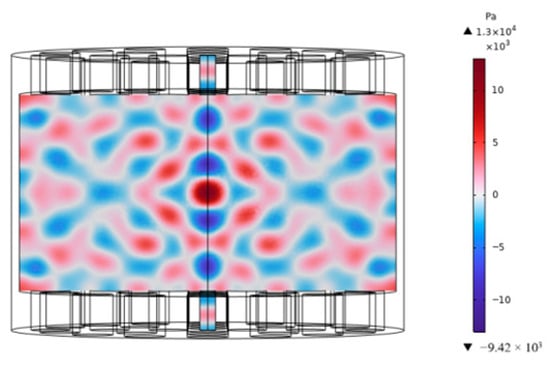

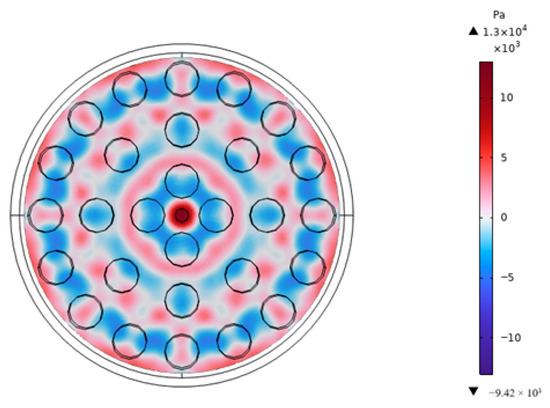

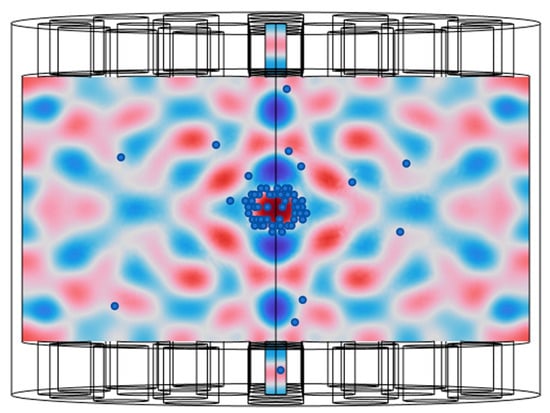

The remaining parameters (nodes 6, 14, 16, 20, 22, 24) require confirmation. Transducer spacing (node 6) was determined as 50 mm, identified as optimal through acoustic propagation formulae [21] considering wavelength and liquid density. A Gaussian pulse waveform was employed for the driving pulse (node 16). Acoustic gradient force (node 20) was derived from the simulated acoustic field, while acoustic radiation force (node 22) and acoustic streaming force (node 24) were obtained through Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations. The finite element analysis was performed using COMSOL Multiphysics® software to simulate the coupled acoustic-structure-piezoelectric phenomena within the levitation device. The model incorporated the key components of the practical system: the piezoelectric transducers, the fluid culture medium, and the solid plastic walls of the culture chamber. The following physics interfaces were used in a fully coupled manner: The Pressure Acoustics, Frequency Domain interface modeled the propagation of ultrasound in the culture medium. The Solid Mechanics interface modeled the deformation of the piezoelectric transducers and the plastic culture chamber. The Electrostatics interface, coupled with Solid Mechanics via the Piezoelectric Effect multiphysics node, modeled the actuation of the transducers. Multiphysics coupling was defined at all fluid-solid boundaries using the Acoustic-Structure Boundary node. The exterior boundaries of the computational domain were surrounded by Perfectly Matched Layers (PMLs) to simulate an open space and absorb outgoing waves, thus preventing spurious reflections. The walls of the culture chamber were modeled as Hard Sound Walls. The piezoelectric transducers were driven by a prescribed voltage boundary condition. A frequency-domain study was conducted at the operating frequency of 275 kHz to obtain the steady-state acoustic pressure field. Utilizing the finalized design parameters, COMSOL Multiphysics simulations generated acoustic field contour plots for the model at both 0.5 MHz and 275 kHz (Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17). Analysis of these plots—evaluating sound pressure distribution, acoustic radiation force patterns, field characteristics, and focal regions—demonstrated superior ultrasound propagation within the liquid medium using the 275 kHz configuration. This model achieved a maximum sound pressure of 1.3 × 104 Pa, with computed acoustic radiation forces on cells meeting stable levitation requirements. Consequently, all cultivation device parameters were finalized, yielding the complete design specification.

Figure 15.

Front view of the 0.5 MHz sound pressure field.

Figure 16.

Frontal view of the 275 kHz sound pressure field.

Figure 17.

Top view of the 275 kHz sound pressure field.

According to the sequential thinking of this design, the main structural schematic diagram of the ultrasonic suspension equipment finally designed is shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Structure of the ultrasonic suspension culture device.

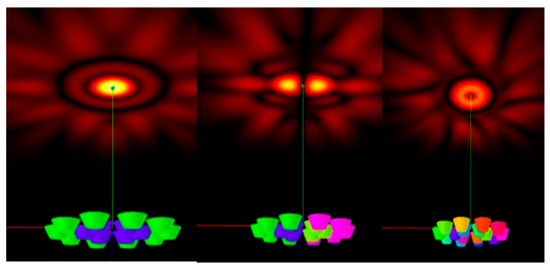

Particle-based simulation results in Figure 19 demonstrate that cells concentrate at the focal point where both the acoustic gradient force and acoustic radiation force reach their maxima. This confirms the device’s capability to stably suspend cell particles within the liquid medium, meeting operational requirements.

Figure 19.

Cell suspension effect diagram.

However, traditional mechanical design methodologies face significant limitations when applied to complex devices like this levitator, characterized by numerous interdependent design parameters. These approaches often rely heavily on designer experience and iterative trial-and-error. A critical limitation arises when parameter values are assigned without fully understanding their mutual constraints. This frequently leads to conflicts between subsequently assigned parameters and earlier choices, necessitating time-consuming design iterations to revisit and modify prior decisions, thereby substantially prolonging the development cycle.

Beyond the stable levitation achieved, the acoustic field in our device defines a specific microenvironment with inherent curvature and confinement, analogous to the physical geometries found in microfluidic channels. It is well-established in mechanobiology that microscale curvature can significantly influence cell behavior, including trajectory, alignment, and migration speed [22,23]. In our system, the curved isopotential lines of the focused acoustic field act as a form of “functional curvature,” guiding and concentrating cells toward the focal point. The observed rapid accumulation and stable residence of cells at the acoustic focus are consistent with such curvature-dependent trapping and accumulation effects reported in the literature. While the current study primarily validates the device’s levitation capability, future work will explicitly investigate how different acoustic field geometries (e.g., varying focal spot size and shape) can be engineered to mimic specific in vivo curved microenvironments, thereby offering a powerful tool for directing more complex cell behaviors such as organized migration or patterned tissue formation.

In contrast, the design methodology proposed in this work addresses these challenges systematically. By establishing a multi-physics enhanced TBS model, we explicitly analyzed the constraint relationships between design parameters. Based on these constraints, a design change propagation network model was constructed. Applying the HITS algorithm to this network provided a dual-metric ranking (Authority and Hub scores) for each node (parameter), enabling optimal sequencing of the design process. This structured sequence allows for the efficient and conflict-free determination of all parameter values, effectively eliminating the need for backtracking and modifications. Consequently, the methodology significantly reduces reliance on empirical judgment and extensive trial-and-error while concurrently shortening the design timeline.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Acoustic Field Measurement and Validation

The acoustic pressure field within the levitation chamber was measured to validate the simulation results. The measurement setup consisted of a needle hydrophone (Precision Acoustics NH-0.5-1.0 mm, Dorchester, UK) connected to a digital oscilloscope(Tektronix, Beaverton, OR, USA). The hydrophone was calibrated by the manufacturer prior to use, with a sensitivity of 0.10 V/MPa. It was mounted on a three-axis micro-positioning stage to allow for precise spatial mapping. The transducer excitation is driven by the ZYNQ7020(Xilinx, San Jose, CA, USA) main control and amplified by the power amplification chip TC4427 (Microchip Technology, Chandler, AZ, USA). The driving signal was a 275 kHz continuous wave at a driving voltage of 20 Vpp. The hydrophone was scanned through the region of interest, particularly through the acoustic focus, and the peak-to-peak voltage was recorded and converted to pressure. The maximum acoustic pressure of 1.3 × 104 Pa reported in this study is the peak negative pressure measured at the focal point.

5.2. Cell Levitation Experiment

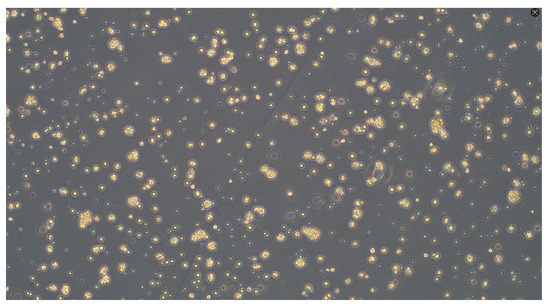

To experimentally validate the levitation and culture capability of the device, a biological experiment was conducted using Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (HUC-MSCs).

Cell Preparation and Loading: HUC-MSCs were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Upon reaching 80–90% confluence, cells were harvested. Briefly, the culture medium was aspirated, and the cell layer was rinsed with PBS. The cells were then detached using 0.25% trypsin for approximately 1 min, and the digestion was neutralized with complete medium. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min, and the pellet was resuspended in fresh complete medium to a final density of 1 × 106 cells/mL. A 50 μL aliquot of this cell suspension was carefully injected into the central culture chamber of the pre-sterilized acoustic levitation device.

Acoustic Levitation Protocol: The device was immediately activated after cell loading. The piezoelectric transducers were driven at the predetermined optimal frequency of 275 kHz and a voltage of 20 Vpp to generate the focused acoustic field. The entire device was placed on the stage of an inverted optical microscope (Olympus IX73,Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) for real-time observation. The levitation process was monitored and recorded using a high-speed camera (Photron FASTCAM Mini AX, Tokyo, Japan).

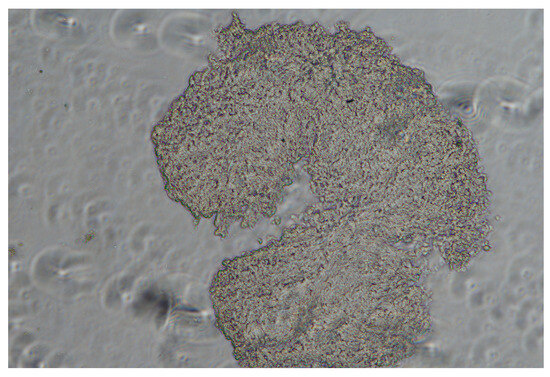

Observation and Results: The dynamic process of cell assembly under the acoustic field was captured. As shown in Figure 20, immediately upon activation of the ultrasound, the cells, initially dispersed in the medium, began to migrate and assemble. Within minutes, the cells were successfully gathered and stably confined at the acoustic focal point, forming a dense, three-dimensional cellular aggregate, as clearly depicted in Figure 21. This transition from a dispersed state to a stable aggregate demonstrates the effective levitation and manipulation capability of the device.

Figure 20.

Initial ultrasound suspension cells under the microscope.

Figure 21.

Ultrasonically focused suspension culture of agglomerated cells.

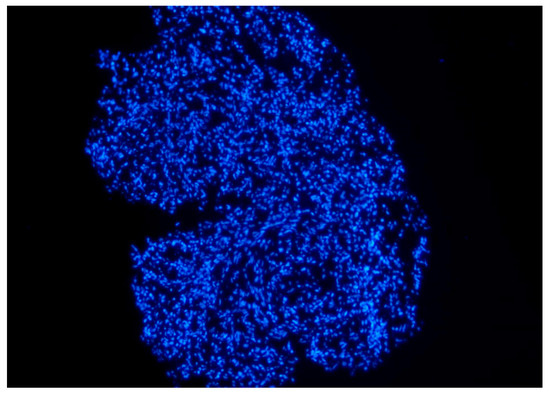

The stained cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope, as shown in Figure 22. It can be seen that many cell nuclei were aggregated on the matrix, indicating that the acoustic field parameters (275 kHz, 1.3 × 104 Pa) used in this study can achieve cell agglomeration culture, avoiding adherent culture and providing a mild biocompatible environment. Increase the cell survival rate throughout the suspension culture process.

Figure 22.

Staining after cell agglomeration in ultrasonic suspension culture.

5.3. Quantification of Design Cycle Time Reduction

The claimed 40% reduction in design cycle time was quantified by comparing the current TBS-based design process against a traditional, experience-based, trial-and-error design process for a device of similar complexity. The traditional process was reconstructed based on historical project data and interviews with senior engineers. The key phases compared included: concept finalization, parameter definition and iteration, detailed design, and prototype simulation validation.

Traditional Method Duration: The traditional process was estimated to require 2 weeks, with a significant portion of time (1 week) spent in the parameter definition and iteration loop. Proposed TBS Method Duration: The proposed method, with its systematic parameter sequencing, completed the same phases in 1.2 weeks. This comparison highlights the efficiency gain primarily achieved by eliminating the extensive iterative loops through pre-emptive conflict resolution via the HITS algorithm.

6. Conclusions

This study addresses the challenge of defining all design parameters and establishing their sequencing during the conceptual design phase of novel mechanical products. A top-down modeling approach incorporating coupled multi-physics was employed to identify and characterize the requisite design parameters for the new product. Complex network theory was then applied to analyze the propagation of design constraints among these parameters. Each parameter was represented as a node within a directed network model.

Leveraging the actual interdependencies between parameters, the design sequence was systematically determined by referencing the Authority and Hub rankings derived from the HITS algorithm. An illustrative case study validates the methodology, yielding the following key conclusions:

Enhanced Multi-Physics TBS Model Capability: The refined multi-physics TBS model facilitates analysis not only of a product’s mechanical structure but also its associated physical fields.

Parameter Identification in Conceptual Design: This model effectively identifies specific design parameters requiring analysis during the abstract, conceptual stages of mechanical product development.

Network-Based Design Sequencing: Design parameters can be structured as nodes within a complex network. Utilizing the HITS algorithm to rank node importance provides a robust basis for establishing the design sequence. This approach significantly reduces reliance on designer experience and iterative trial-and-error, thereby shortening the overall design cycle compared to conventional methodologies.

Author Contributions

Y.L. (Yuchao Liu): Conducted the simulation modeling, designed the hardware and software for the ultrasonic device, designed the experiments, organized the data, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. Y.G.: Revised the manuscript and handled communication and feedback with the editor. F.S.: Designed the experimental procedures and provided the experimental setup and equipment. Y.L. (Yuping Long): Assisted with the simulation and mechanical structure design, and provided guidance on acoustic field simulation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China: Research on the Evolution Mechanism of Product Manufacturing Information Gap in Cloud Manufacturing (Project No. 51375314).

Data Availability Statement

The paper contains adequate details on the methodology and implementation. All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this paper. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Cai, H.; Wu, Z.; Ao, Z.; Nunez, A.; Chen, B.; Jiang, L.; Bondesson, M.; Guo, F. Trap cell spheroids and organoids using digital acoustofluidics. Biofabrication 2020, 12, 035025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.; Jeong, S.; Kang, Y.J. Ultrasound standing wave-based cell-to-liquid separation for measuring viscosity and aggregation of blood sample. Sensors 2020, 20, 2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, F.; Guimarães, C.F.; Reis, R.L.; Franco, W.; Rizvi, I.; Demirci, U. Emerging biofabrication approaches for gastrointestinal organoids towards patient specific cancer models. Cancer Lett. 2021, 504, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vafaie, A.; Shahali, S.; Raveshi, M.R.; Nosrati, R.; Neild, A. Repeated pulses of ultrasound maintain sperm motility. Lab A Chip 2024, 25, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Savchenko, O.; Li, Y.; Qi, S.; Yang, T.; Zhang, W.; Chen, J. A Review of Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound for Therapeutic Applications. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 66, 2704–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, H.; Pang, M. Direct Numerical Simulation of Quasispherical Bubble Motion in Ultrasonic Standing Wave Fields. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 19274–19288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wong, Y.S.; Lee, K.S. Modularity analysis and commonality design: A framework for the top-down platform and product family design. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2010, 48, 3657–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.; Nie, Y.; Zhang, D. A new top-down design method for the stiffness of precision machine tools. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 83, 1887–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, N.; Cao, J.; Huang, S.; Tang, W. Skeleton model-based approach to integrated engineering design and analysis. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 85, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; He, Y.; Gao, L.; Li, B. Vector Space Reconstruction Model Based on Product Characteristic Linkage and Design Change Propagation. J. Mech. Eng. 2022, 58, 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X. Information State and Information Measurement for Modeling Design Based on TBS. J. Mech. Eng. 2013, 24, 2131. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.; Jia, W. Research on Information Representation and Model Reorganization Methods for Assembly Models Supporting Variant Design. J. Mech. Eng. 2004, 40, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, J. Complex network–based change propagation path optimization in mechanical product development. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 17389–17399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shijie, W.; Xueliang, Z.; Jingya, L.; Yingfeng, Z. Adaptive design change considering making small impact on the original manufacturing process. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 59, 102303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Wu, B.; Yuan, M. The Vulnerable Line Identification based on the Hyperlink-Induced Topic Search Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024—50th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Chicago, IL, USA, 3–6 November 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.Q.; Li, X.R.; Dong, J.C. A survey on network node ranking algorithms: Representative methods, extensions, and applications. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2021, 64, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, H. PageRank Algorithm and HITS Algorithm in Web Page Ranking. In Proceedings of the Application of Intelligent Systems in Multi-Modal Information Analytics: 2021 International Conference on Multi-Modal Information Analytics (MMIA 2021), Cham, Switzerland, 21 April 2021; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, D.; Xue, L.; Chen, L. A piezoelectric heart sound sensor for wearable healthcare monitoring devices. In Proceedings of the Body Area Networks: Smart IoT and Big Data for Intelligent Health Management: 14th EAI International Conference, BODYNETS 2019, Florence, Italy, 2–3 October 2019; Proceedings 14. Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Gao, H.; Liu, K.; Lei, D.; Pei, K.; Hu, G. A review on particle assembly in standing wave acoustic field. J. Nanopart. Res. 2022, 24, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Crivoi, A.; Peng, X.; Shen, L.; Pu, Y.; Fan, Z.; Cummer, S.A. Three dimensional acoustic tweezers with vortex streaming. Commun. Phys. 2021, 4, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.X.; Jung, D.; Lee, H.S.; Du Nguyen, V.; Choi, E.; Kang, B.; Park, J.-O.; Kim, C.-S. Holographic acoustic tweezers for 5-DoF manipulation of nanocarrier clusters toward targeted drug delivery. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazalan, M.B.; Ramlan, M.A.; Shin, J.H.; Ohashi, T. Effect of Geometric Curvature on Collective Cell Migration in Tortuous Microchannel Devices. Micromachines 2020, 11, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raveshi, M.R.; Halim, M.S.A.; Agnihotri, S.N.; O’bRyan, M.K.; Neild, A.; Nosrati, R. Curvature in the reproductive tract alters sperm–surface interactions. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).