2.3. Description of the Proposed Applied Method

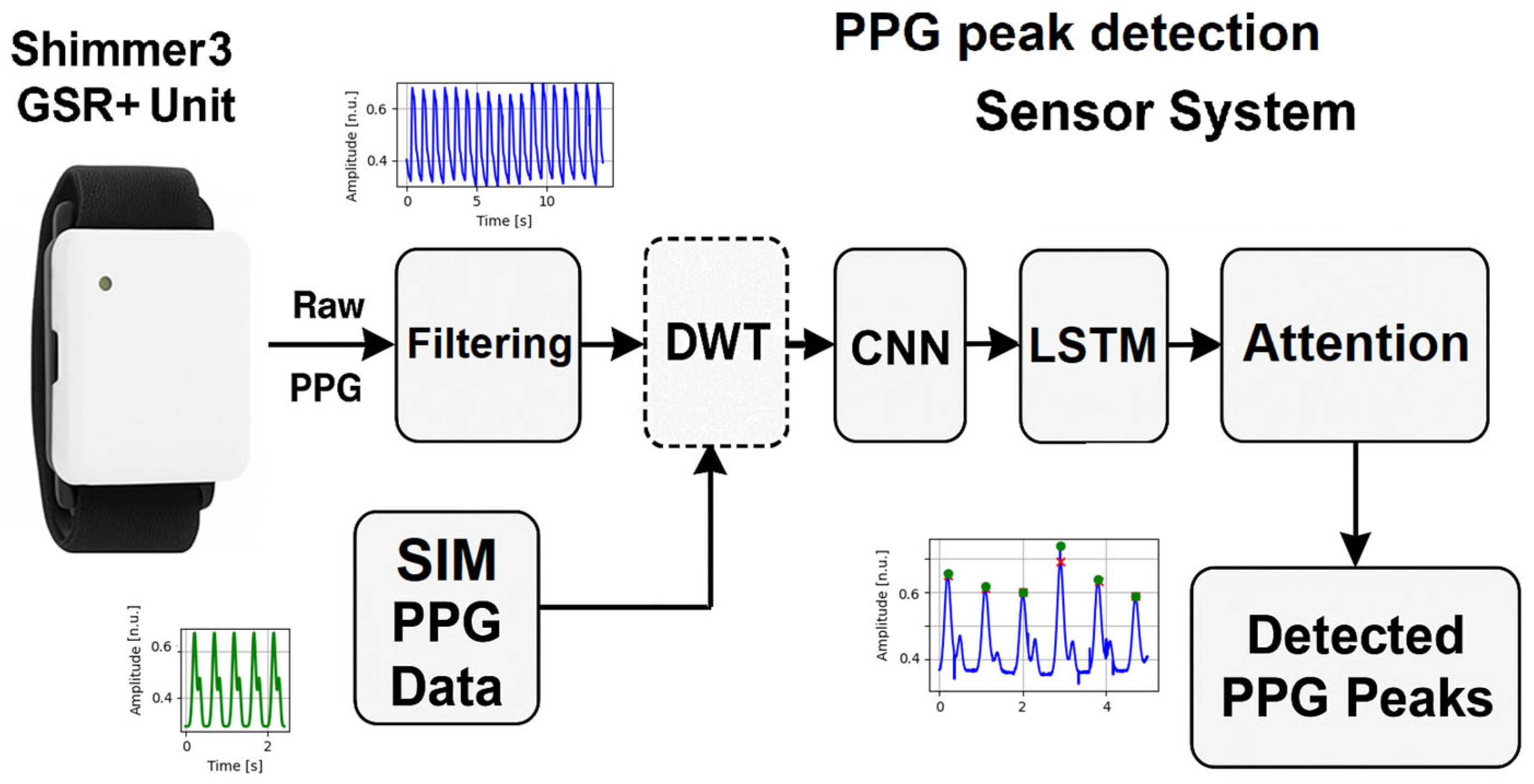

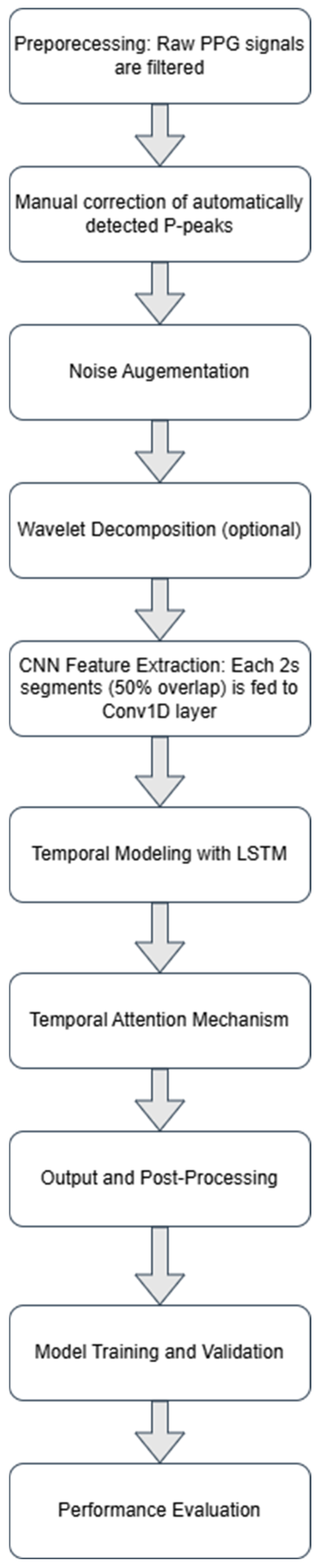

The methodological framework of the proposed approach is summarized in sequential steps to provide a conceptual overview (

Figure 2):

Preprocessing of Raw Data: Butterworth filters are applied, including a high-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 0.5 Hz to eliminate baseline wander and a band-pass filter with a frequency range of 0.5–10 Hz to isolate the PPG frequency spectrum, remove muscle artifacts, and filter out 50/60 Hz electrical noise. Filtering is performed to prevent incorrect annotations.

Manual correction of automatically detected P-Peaks: Manual validation of P-peaks is conducted on the training set to ensure maximum objectivity and accuracy.

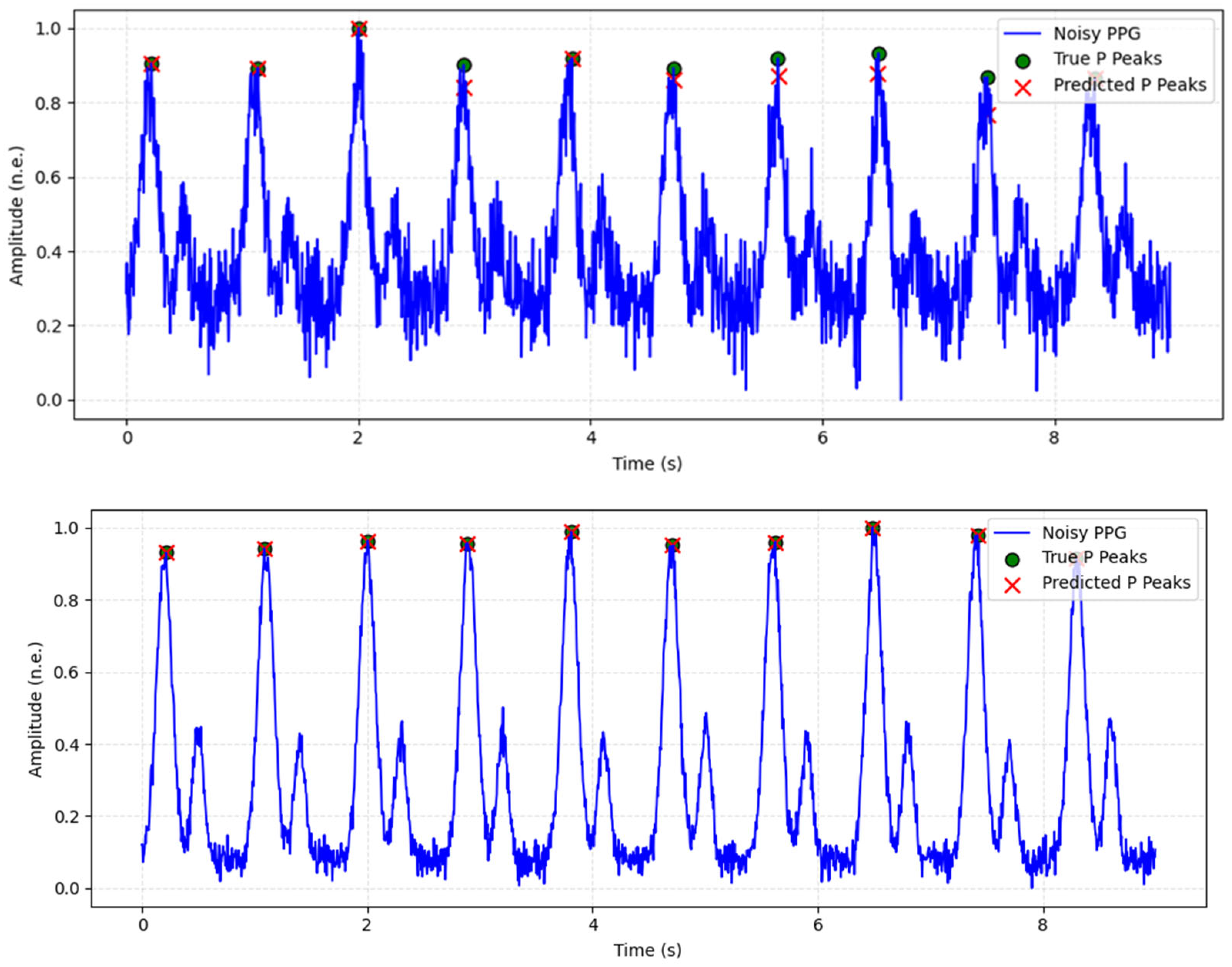

Noise Augmentation: Noise components such as baseline wander, muscle artifacts, and 50/60 Hz power line interference are added to improve the model’s robustness to real-world conditions.

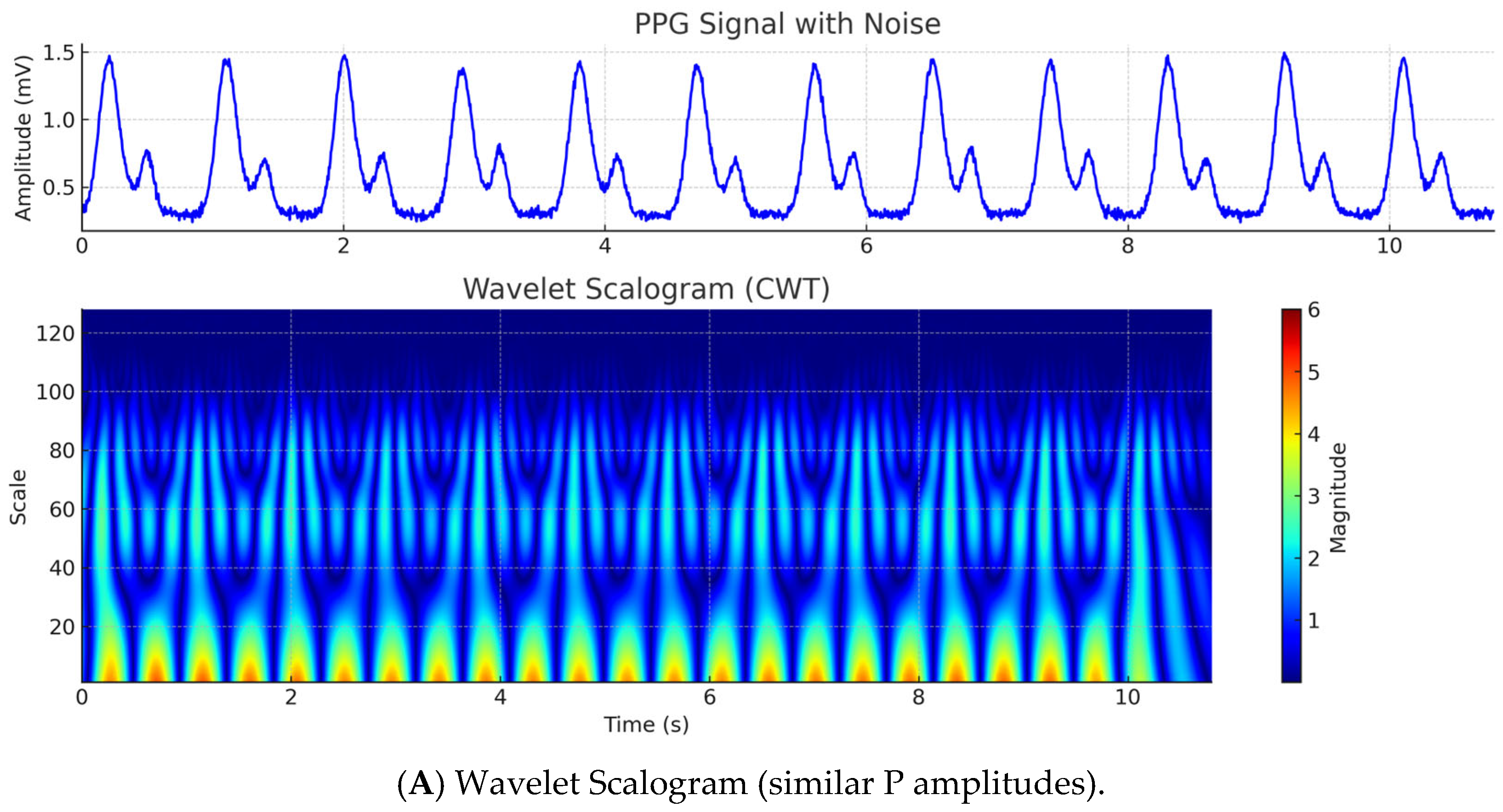

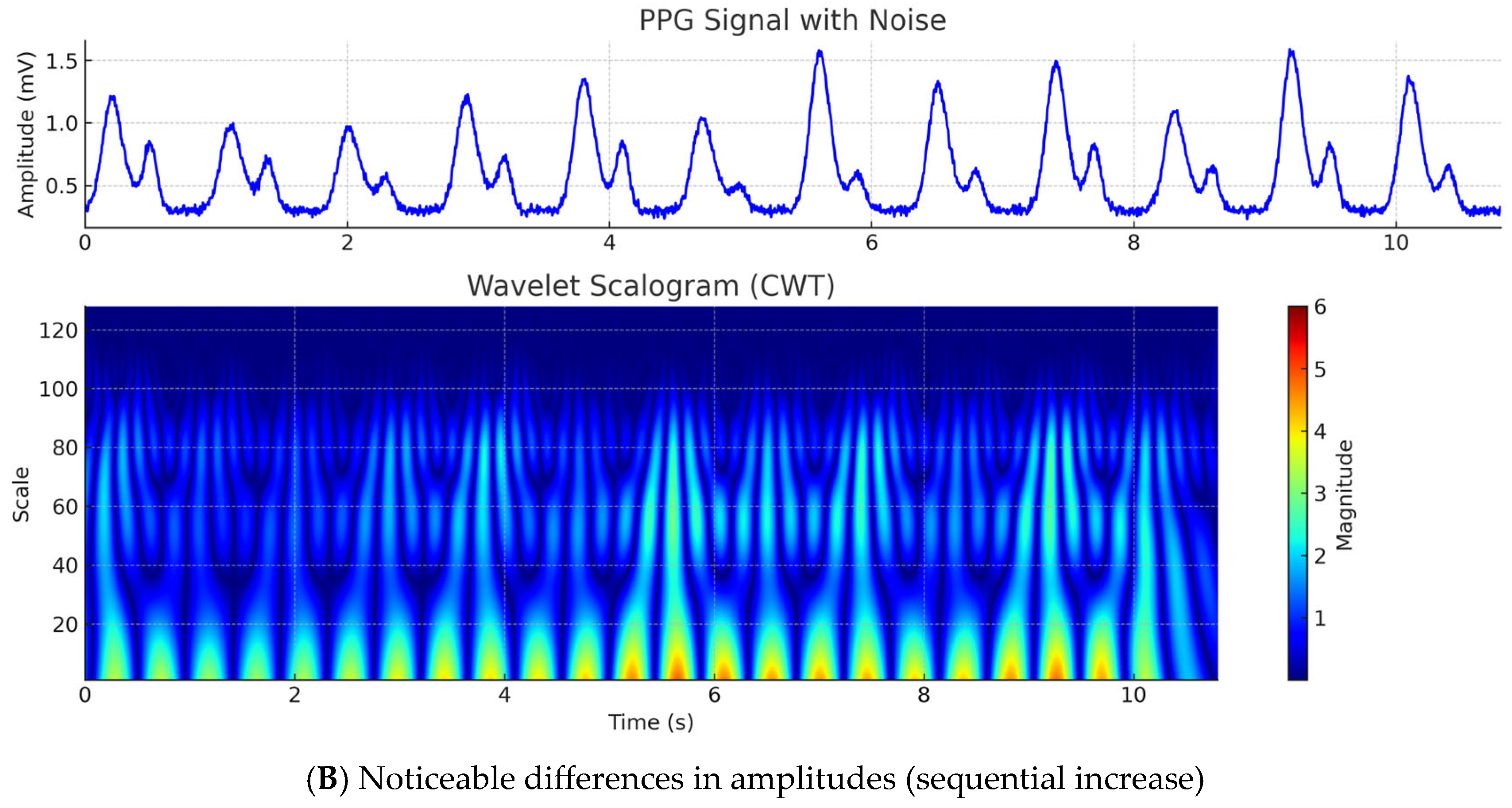

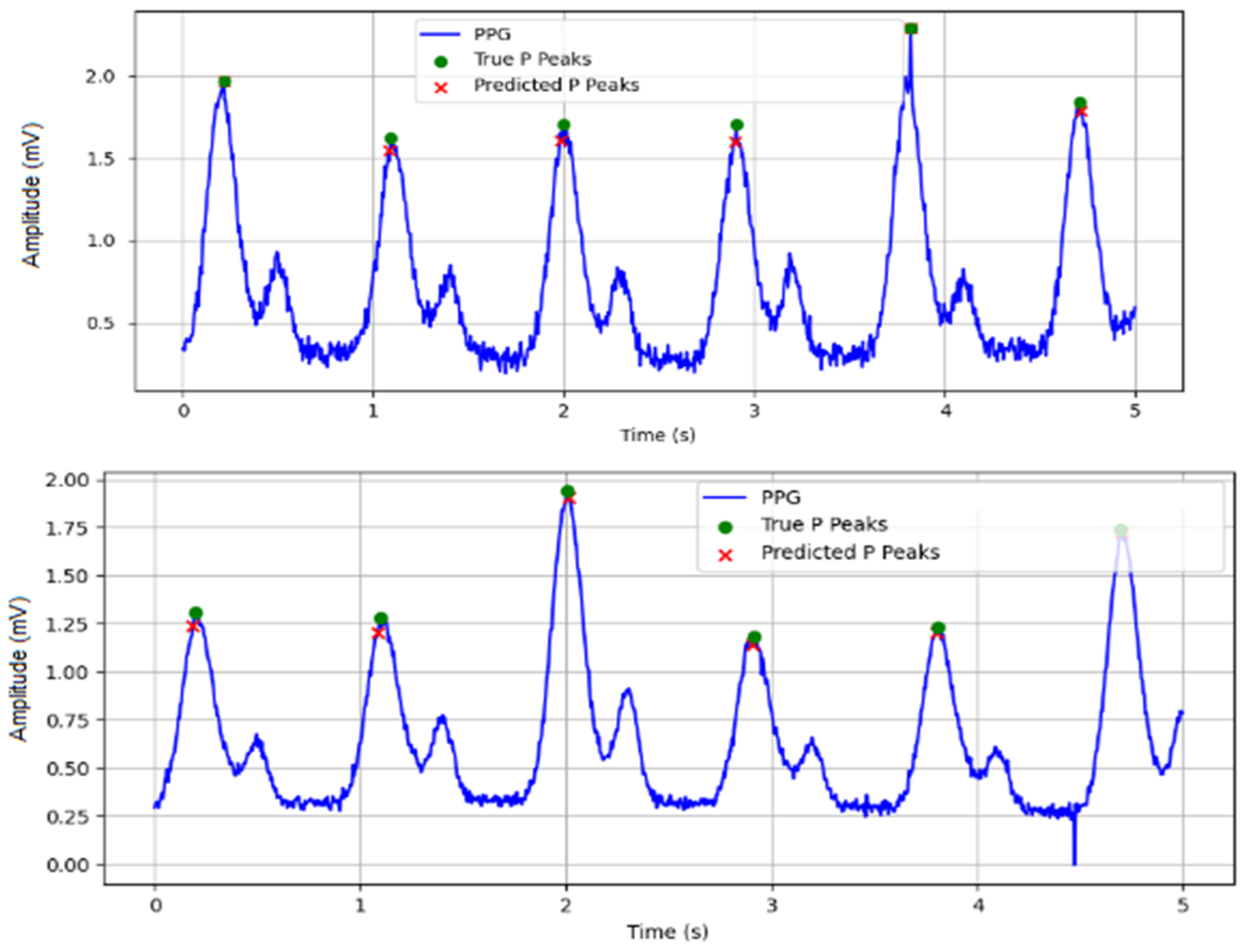

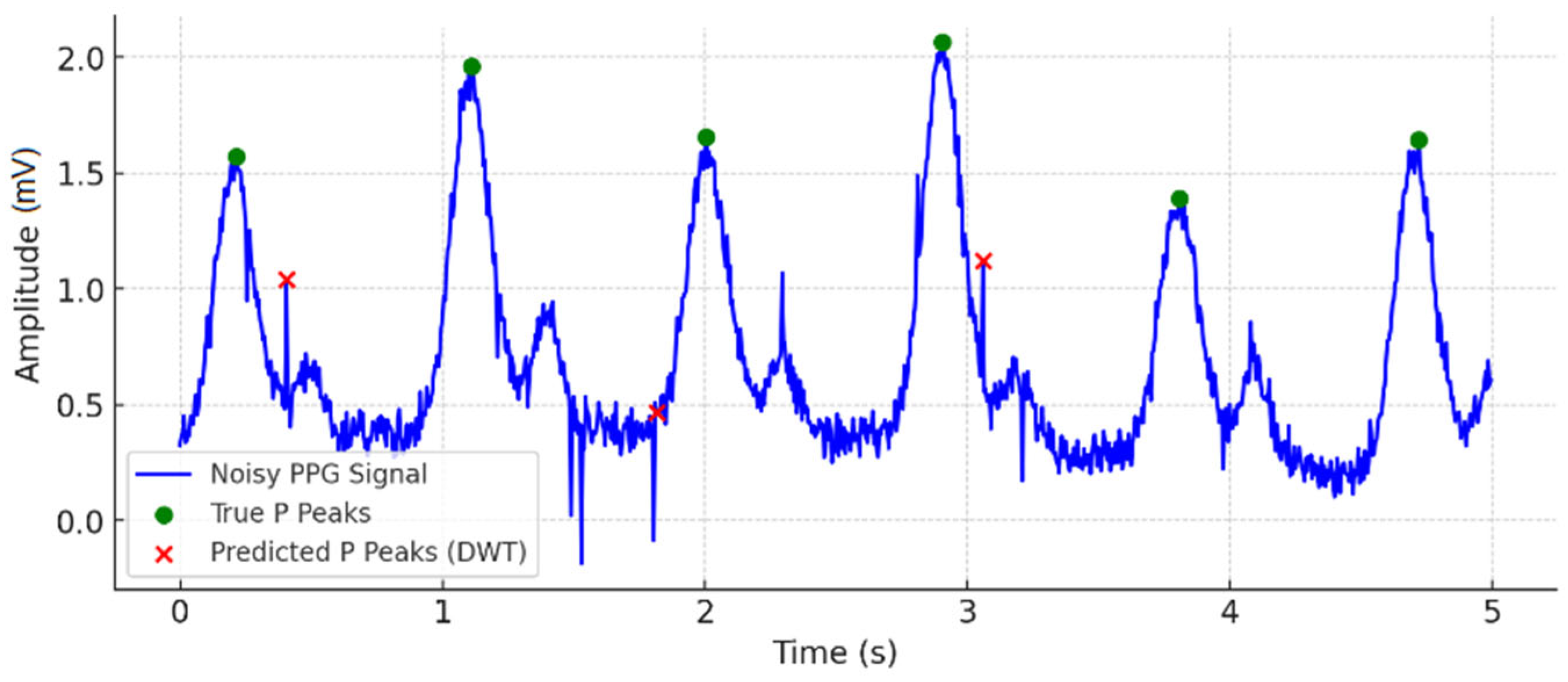

Application of DWT for Signal Decomposition and Feature Extraction: Wavelet coefficients are extracted using DWT, where detail coefficients from the first to the fourth level are utilized for better localization of P-peaks. In this study, the Daubechies-4 (Db4) wavelet basis was used, with the detailed coefficients being resized to the length of the original PPG segment by linear interpolation, which ensures compatibility along the time axis between channels. These coefficients are used as a second input channel to models that include wavelet decomposition, providing additional time-frequency information about the morphological structure of the P-peak. In models without DWT, only the original PPG signal is used.

DWT with Daubechies wave function with 4 coefficients db4, which is suitable for biomedical signals, with 4 levels of decomposition, is applied. In a previous study by the author, it was experimentally and quantitatively demonstrated that the Db4 wavelet with decomposition level 4 provides optimal performance for PPG peak detection, balancing time–frequency resolution and noise sensitivity [

21].

The wavelet coefficients at level

j and position

k are calculated with the formula

where

—discrete time index;

—the input signal;

—decomposition level (scale index);

—translation index;

—wavelet function (acts as a filter for the corresponding level):

- 5.

Signal Processing with CNN:

- 5.1.

The signal (in single-channel models this is PPG; in dual-channel models—these are PPG and DWT detail coefficients) is divided into overlapping time windows (2 s with 50% overlap).

- 5.2.

Conv1D layers are applied to DWT coefficients to extract local features.

- 5.3.

A MaxPooling layer is incorporated to reduce dimensionality while preserving the most relevant features.

Signal Processing with CNN.

ReLU activation is applied to Convolutional layers:

Equation for the output signal:

where

—input sequence to the CNN layer, which comes from the detailed DWT coefficients at time t;

—convolutional layer filter (of size K).

—the bias term of the layer.

The included MaxPooling layer is with Pool Size = 2, formula for the output signal:

—the input signal from the previous Conv1D layer;

—pool size (MaxPooling layer window size).

A Dropout layer (0.25) has been added after the CNN to combat overfitting. At each iteration, 25% of the neurons in this layer will be randomly dropped, resulting in greater randomness and a more robust model.

The use of 2 s windows with 50% overlap can be interpreted as a form of temporal decomposition, akin to patch-based encoding in recent Transformer models. This strategy allows the model to capture both local waveform features and broader temporal dependencies between adjacent windows. Each window encapsulates a temporally coherent segment of the PPG signal, enabling the CNN layers to focus on high-resolution local features, as the subsequent LSTM and attention layers model the dynamics within the windows. For signal segments at the beginning and end of the recording that do not fully fit into a window, zero-padding is applied to maintain uniform input shape. The overlapping design also ensures smooth temporal coverage and robustness to boundary effects, especially near peak transitions.

- 6.

Incorporation of LSTM Layers: LSTM layers process sequences of extracted features to identify repetitive patterns in the PPG signal.

Forget Gate is described by the formula

where

—Input weight matrix

—Input vector for the current moment t;

—Weight matrix for the previous hidden state ;

—The hidden state from the previous moment;

—The Bias vector (added to compensate for the values);

—Sigmoid function that limits the output between 0 and 1.

Input Gate is described by the formula:

Candidate for new information:

is fed to the next layers for detection of P vertices;

—previous cell memory;

—learnable weight and biases;

—sigmoid activation;

—element-wise multiplication.

In binary classification, a single neuron with sigmoid activation is used:

At it is assumed that a localized peak (1) is present.

At it is not a peak.

Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) is used for the loss function, as the output is a probability (0 or 1):

where

N—number of parameters;

—true (labeled) value;

—predicted value obtained by the sigmoid function.

LSTM was selected over simpler recurrent units (e.g., GRU) or temporal convolutions due to its ability to retain long-range temporal dependencies, which is critical for distinguishing subtle rhythmic patterns in PPG morphology.

A second Dropout layer (rate = 0.3) is applied after the LSTM output, before the attention mechanism, to further regularize the temporal encoding and reduce overfitting of the recurrent layers.

- 7.

Temporal Attention Layer

The inclusion of a temporal attention layer allows the model to assign dynamic importance weights to different time steps in the input sequence. This mechanism improves the model’s ability to focus on temporally relevant segments that are more likely to contain P-peaks, while reducing the weight of less informative or noisy regions. Using the self-attention mechanism in Transformer-based architectures [

10], this attention strategy allows for improved peak localization by exploiting the different contributions of temporal context in each sliding window. Unlike static filters or convolutional kernels, attention weights are learned adaptively during training, providing a flexible mechanism for modeling temporal importance.

The context vector c is computed from the hidden states of the LSTM using a temporal attention mechanism that assigns a learned importance weight to each time step. This allows the model to focus on the most informative temporal regions within each time window, enhancing peak classification accuracy.

The attention mechanism is mathematically defined as follows. First, a raw attention score

is computed for each time step

t using a feedforward layer with trainable parameters:

These scores are then normalized using the softmax function to obtain attention weights:

The final context vector is calculated as the weighted sum of all hidden states:

where

—the hidden state vector at time t;

, and —trainable parameters of the attention layer;

—represents the normalized attention weight for each time step;

c—the weighted context vector passed to the output classifier.

The context vector is then forwarded to the classification layer for the final peak prediction. This mechanism ensures that attention is concentrated on segments surrounding true peaks, improving the precision of localization and reducing false positives near waveform transitions.

- 8.

Output Layer and Post-Processing:

- 8.1.

A Dense layer with Sigmoid activation is used to predict the probability of each sample being a P-peak.

- 8.2.

Threshold-Based Detection: An optimal adaptive threshold is determined for peak detection.

- 8.3.

Filtering of Results: Incorrectly detected peaks that do not correspond to local maxima in the signal are removed, and duplicate peaks are eliminated. The peak removal algorithm checks whether each predicted event corresponds to a true local maximum in the filtered PPG signal. If the predicted peak is not a local maximum or falls outside a ±50 ms window of an annotated or valid peak, it is rejected. Potential peak candidates within 200 ms are merged into a set, and the one with the highest amplitude is selected from this set.

- 9.

Model Training: The dataset is split into 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing. The Adam optimizer is used.

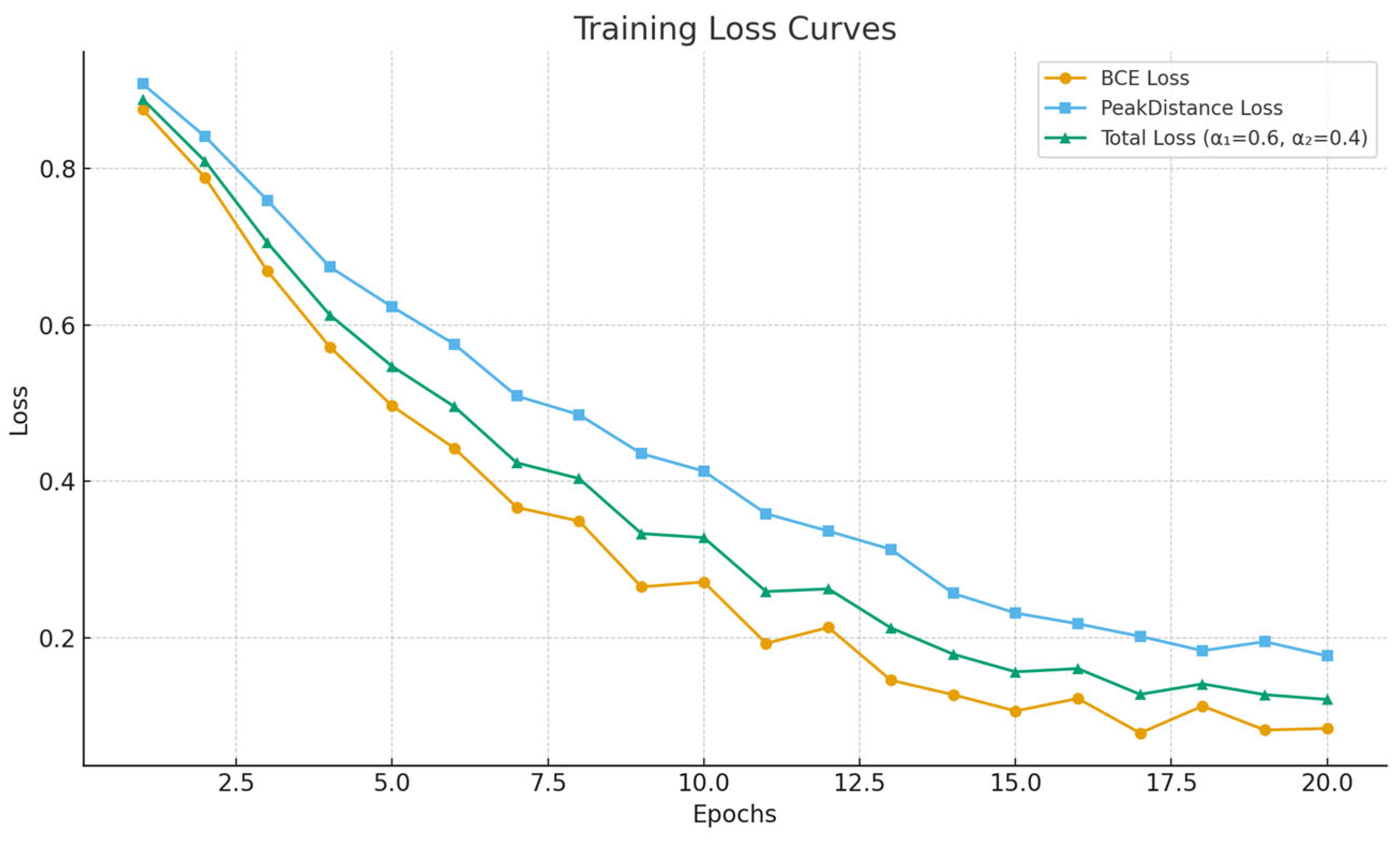

The network is trained using the BCE loss, which is suitable for binary classification tasks such as peak detection (Equation (14)).

To enhance the temporal localization of peaks, we additionally propose a PeakDistanceLoss, which minimizes the distance between true and predicted peaks:

where

are the ground truth peak positions, and

are the predicted peak positions.

The proposed (Equation (19)) is formally defined as the average minimal temporal deviation between each reference peak and its nearest predicted counterpart . This formulation ensures that the loss is (1) non-negative, with if and only if all predicted peaks perfectly coincide with the ground-truth positions; (2) monotonically increasing with the temporal displacement , guaranteeing that larger localization errors contribute proportionally higher penalties; and (3) differentiable almost everywhere, allowing gradient-based optimization in end-to-end neural training. Compared to standard amplitude-based losses such as Binary Cross-Entropy or Mean-Squared Error (MSE), which only penalize classification errors at the sample level, measures temporal accuracy. By minimizing the spatial–temporal misalignment between predicted and true peaks, it provides a direct optimization target for localization tasks.

The total loss combines both terms:

with weighting factors

and

used to balance classification and localization performance.

Training data composition and partitioning

To ensure a robust and generalizable model, the dataset was constructed from three complementary sources:

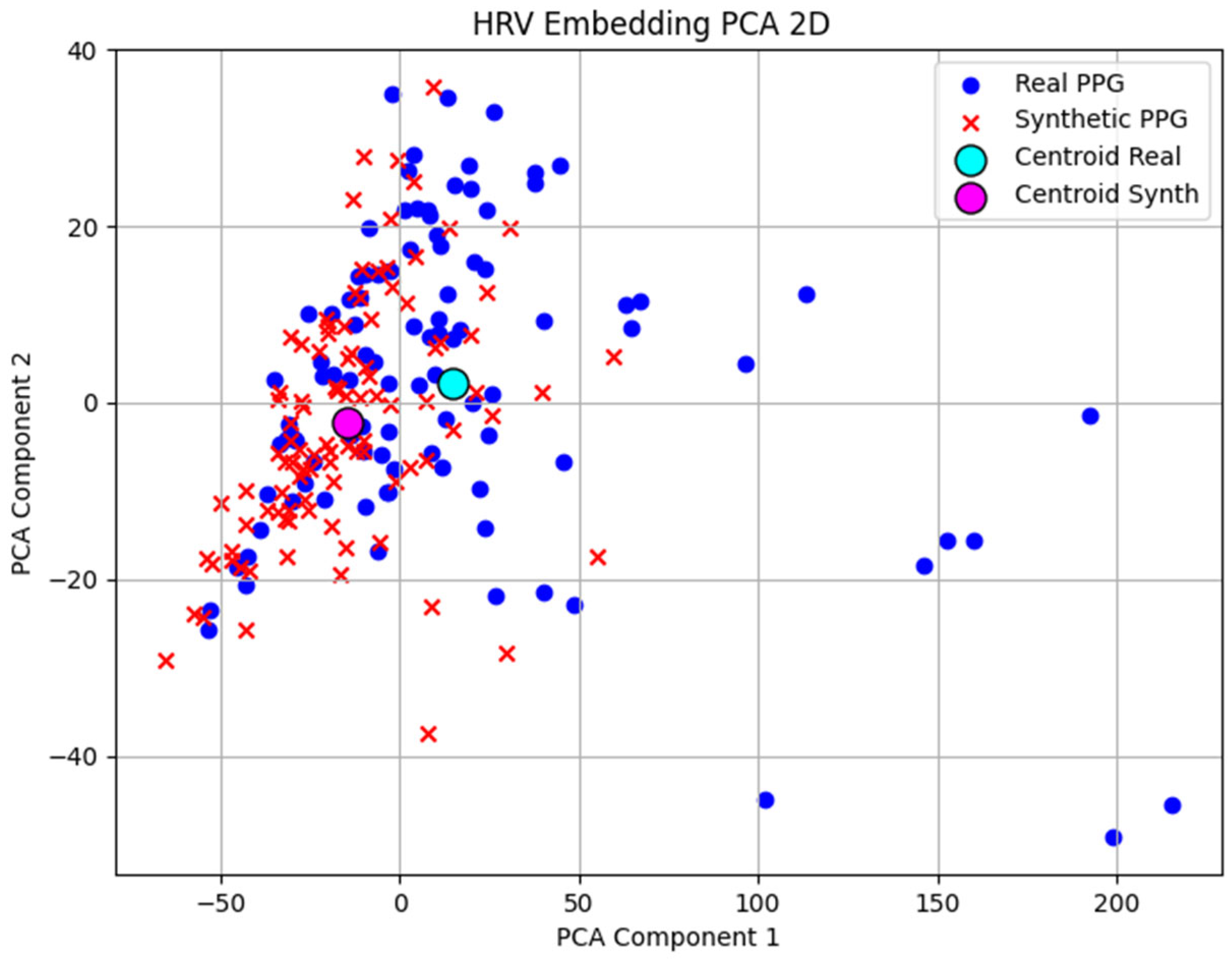

The Deep-SimPPG generator used combines mathematical modeling and generative neural networks implemented with a 1D CNN architecture. In the first stage, a baseline signal is created by summing two Gaussian functions that describe the basic morphology of the PPG pulse wave—the systolic wave, reflecting the direct blood flow from the heart contraction, and the diastolic (reflected) wave, caused by the reflected pulse waves from the peripheral vessels. This baseline signal is fed to the GAN generator, which, by adding noise, enriches its shape with realistic physiological variations and noise artifacts. The discriminator, which is fed both synthetic and real PPG segments, is trained to distinguish real from artificial signals, guiding the generator towards a more realistic synthesized output.

All PPG recordings were segmented into fixed-length 2 s windows with 50% overlap, resulting in a large number of training examples. Only complete segments were used, and zero-padding was applied when necessary. To prevent subject-related data leakage, all segments originating from the same participant or original recording were assigned exclusively to one of the three subsets—training, validation, or testing—ensuring no overlap between them.

Synthetic data were used only in the training and validation phases to improve model robustness to noise and morphological variability. The final testing subset included only unused real recordings from both BIDMC and Shimmer volunteers, ensuring unbiased evaluation of model generalization.

The total data (

Table 1) used is approximately 194,912 two-second recordings, corresponding to approximately 70% training (136,408), 15% validation (29,240), and 15% testing (29,264) (the exact ratio is 69.984%/15.002%/15.01%). Synthetic signals were excluded from the final testing set and to ensure that the model evaluation reflects its application on real PPG data.

A composition of the training, validation, and testing datasets used in the proposed PPG peak detection framework is shown in

Table 1. The table summarizes the origin of the data (real, synthetic, or public), their purpose in the training protocol, and the approximate number of 2 s windows (with 50% overlap) used in each subset.

Distribution of records by datasets:

BIDMC PPG and Respiration Dataset: 53 subjects (recordings), 8 min each (25,016 Approx. Segments 2 s. at 50% overlapping).

Shimmer: 26 volunteers × 10 recordings, 8 min each, (122,720 Approx. Segments 2 s. at 50% overlapping).

Synthetic signals: 100 recordings, 8 min each (47,200 Approx. Segments 2 s. at 50% overlapping).

To ensure the robustness of the results and to avoid dependence on a specific random partition, 5-fold cross-validation is applied within the training set: the data is divided into five equal subsets, with one used for validation and the remaining four for training at each iteration. The five results obtained are averaged to provide a statistically reliable estimate of the metrics.

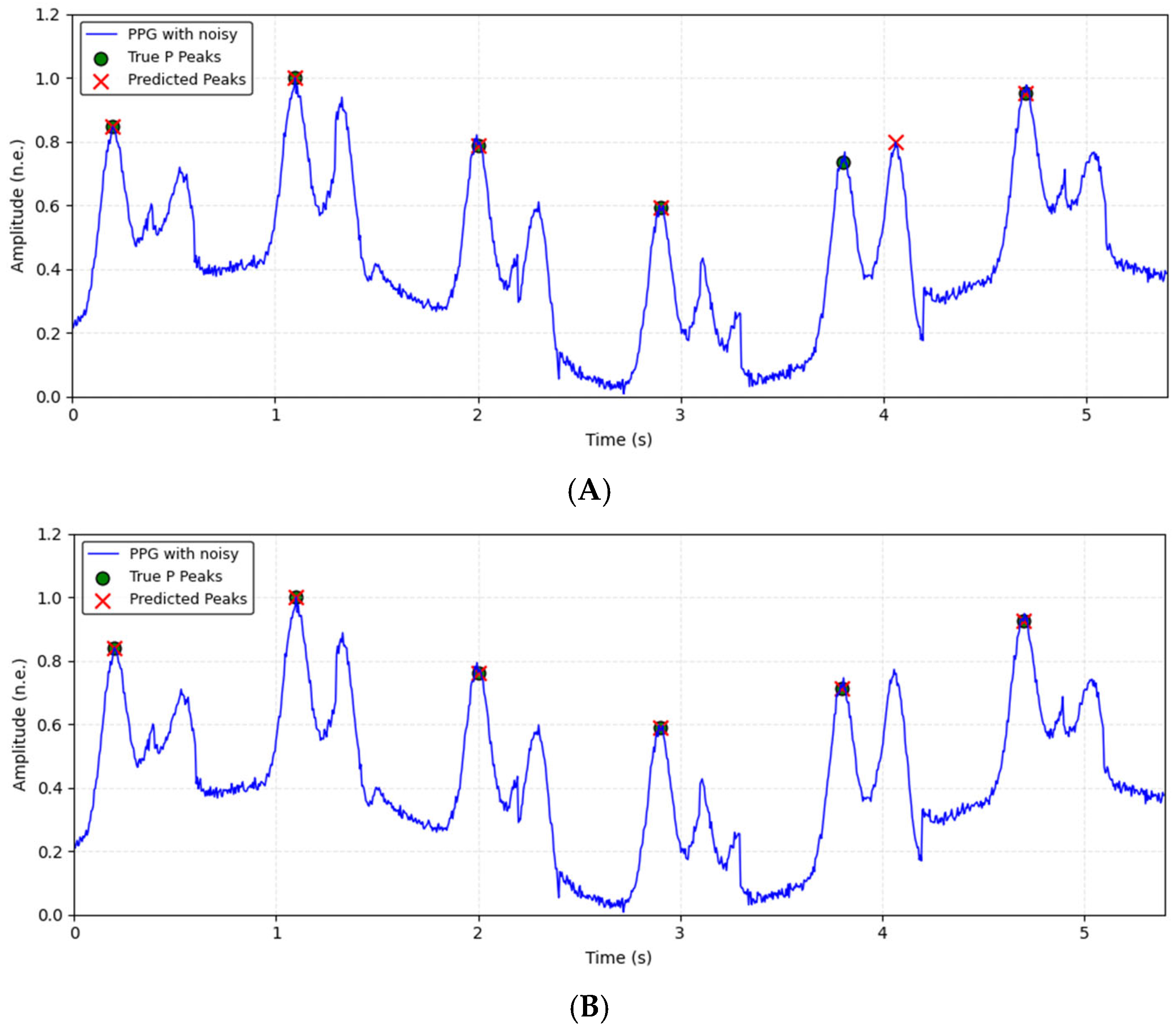

Model Architectures

For analysis and testing of the presented algorithm, a custom Python 3.10 framework was developed to enable the evaluation of multiple model configurations. The models were trained using the Adam optimizer with a fixed learning rate η = 0.001 and 20 epochs. Two commonly used activation functions were explored—Sigmoid and Tanh—to assess their impact on training convergence and prediction accuracy. The architectural configurations of the proposed 30 models are summarized in

Table 2, including the type of neural network, input signal transformation, activation functions, and the number of neurons per layer.

The models differ by type of network (CNN, LSTM, CNN + LSTM, and CNN + LSTM + Attention), input data format (raw PPG or DWT-transformed signals at different decomposition levels), activation function, and the number of neurons in the hidden layers (16/32/16 and 32/64/32). The goal was to systematically compare simpler and more complex topologies, as well as the influence of including DWT (detailed coefficients, second or third level) and attention mechanisms, on P-peak detection performance.

This systematic exploration allowed for identifying the optimal configuration in terms of robustness to noise, computational efficiency, and detection accuracy, as further discussed below.

The number of neurons per layer in each model was determined empirically based on preliminary experiments and architectural symmetry considerations.

Two main configurations were finally evaluated: (16/32/16) for lighter models and (32/64/32) for deeper architectures.

These values were chosen to achieve balanced feature extraction and compression while maintaining an appropriate total number of trainable parameters relative to the size of the available dataset and avoiding overfitting.

The symmetric structure (e.g., 16–32–16) was adopted to allow for progressive feature abstraction in the intermediate layer, followed by dimensionality reduction—similar to encoder–decoder designs.

The larger configurations (e.g., 32–64–32) were used in the CNN + LSTM + Attention models to evaluate the effect of higher representational capacity.

The final number of neurons listed in

Table 1 corresponds to the configurations that achieved the highest F1-score on the validation set.

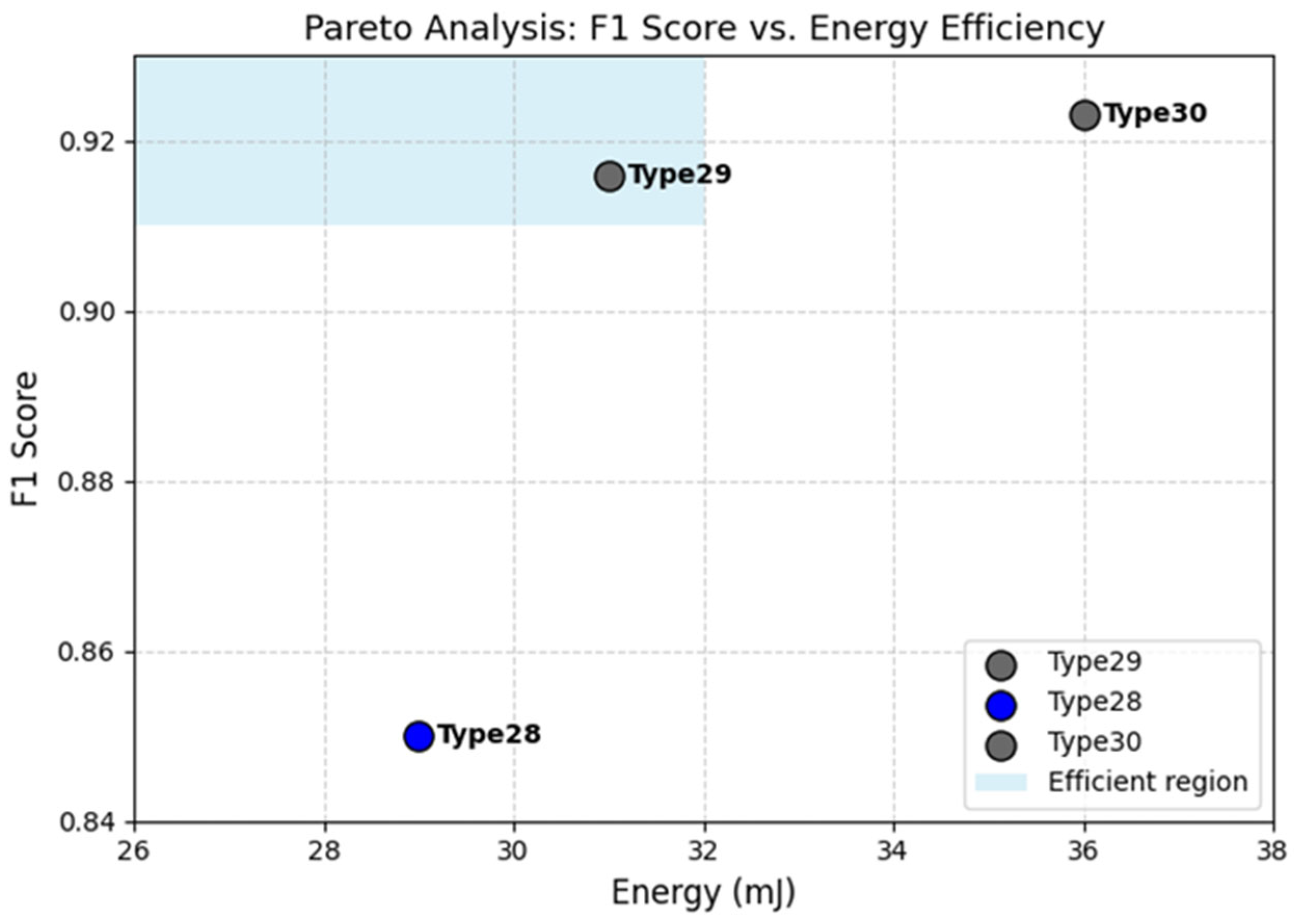

Full Architecture of the Proposed CNN–LSTM–Attention Model

The complete architecture of the model Type30 (

Table 3) integrates convolutional, recurrent, and attention layers in a sequential hybrid configuration designed for robust P-peak detection from PPG signals. The model receives as input either a 2 s PPG window with DWT coefficients level 3.

The CNN block extracts local morphological features, while the LSTM block captures temporal dependencies between consecutive waveform patterns. Finally, the attention layer adaptively weights the most informative time steps, emphasizing those likely to contain P-peaks and suppressing noisy regions.

Training Procedure

All models were implemented and trained using Python (TensorFlow environment). The training dataset consisted of annotated PPG signals, preprocessed with optional DWT up to level 3. Each signal window was annotated by marking the time points that fall within the local maximum around the real P-peak (±25 ms). A detected P-peak was considered correct if it occurred within ±25 ms of the reference annotation. The models were trained for 20 epochs using the Adam optimizer with default parameters (learning rate α = 0.001, β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999). The binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss function was used, as the task was formulated as a binary classification problem (peak vs. no peak). Mini-batch training was employed with a batch size of 64, and early stopping was monitored based on the validation loss with a patience of 5 epochs to prevent overfitting. All signals were normalized to the range [0, 1] before training. Two activation functions were tested: Sigmoid and Tanh. Dropout (rate = 0.2) was applied after each hidden layer to improve generalization. For hybrid models with attention (Type25–Type30), the layer was placed after the LSTM block, before the output dense layer.

Table 4 summarizes the key hyperparameters and training settings used for all CNN–LSTM–Attention model variants in the proposed framework.

The selected hyperparameters and training configuration were chosen to ensure both robust learning and good generalization across heterogeneous PPG data. The use of bandpass filtering (0.5–8 Hz) and normalization was motivated by the need to suppress baseline drift and amplitude variability while preserving morphological characteristics essential for peak localization. The 2 s sliding windows with 50% overlap ensure that each training segment contains at least one complete PPG cycle, enabling the network to learn characteristic temporal patterns. The CNN layers extract local shape-based features (e.g., systolic rise and dicrotic notch), whereas the LSTM units capture longer temporal dependencies across cycles. The dropout rates were set separately for the convolutional (0.25) and recurrent (0.3) blocks, reflecting the higher tendency of LSTM layers to overfit temporal structure. Batch Normalization was included to stabilize training and reduce internal covariate shift, improving convergence stability.

The Adam optimizer with a fixed learning rate of 0.001 was selected due to its strong performance in physiological signal modeling tasks, where gradients are often small and noisy. Early stopping with validation monitoring prevents unnecessary overfitting, while the choice of binary cross-entropy reflects the binary decision nature of peak vs. non-peak detection. For hybrid models (Type25–Type30), a temporal attention mechanism was incorporated to dynamically assign importance weights to time steps, improving robustness in noisy or morphologically variable segments. The use of DWT decomposition (2–3 levels) provides multi-resolution feature representation, enhancing peak salience even at low SNR. Collectively, these design decisions form a training pipeline optimized not only for classification accuracy, but also for precise and reliable temporal localization of P-peaks in realistic PPG recordings.

- 10.

Validation and Testing: Performance evaluation metrics are computed, including Precision—accuracy of detected P-peaks; Recall—ability to detect all true P-peaks; F1 Score—balance between Precision and Recall.

The metrics are calculated based on: True Positives (TP)—cases in which the model correctly recognized P-peaks; False Positives (FP)—errors in which the model found vertices where there are none; False Negatives (FN)—missed real P-peaks.

Precision shows how many of the detected vertices are real:

Recall measures how many of the actual P-peaks are correctly detected:

F1 score gives a balanced assessment of the model’s performance:

The accuracy of the detected R-peak location is evaluated by the annotated-detected error:

—the moment of the annotated (reference) P-peak;

—the moment of the detected P-peak;

—the time step (sampling period).

These metrics are particularly important in biomedical contexts, where both missed detections (false negatives) and false alarms (false positives) can have clinical consequences.

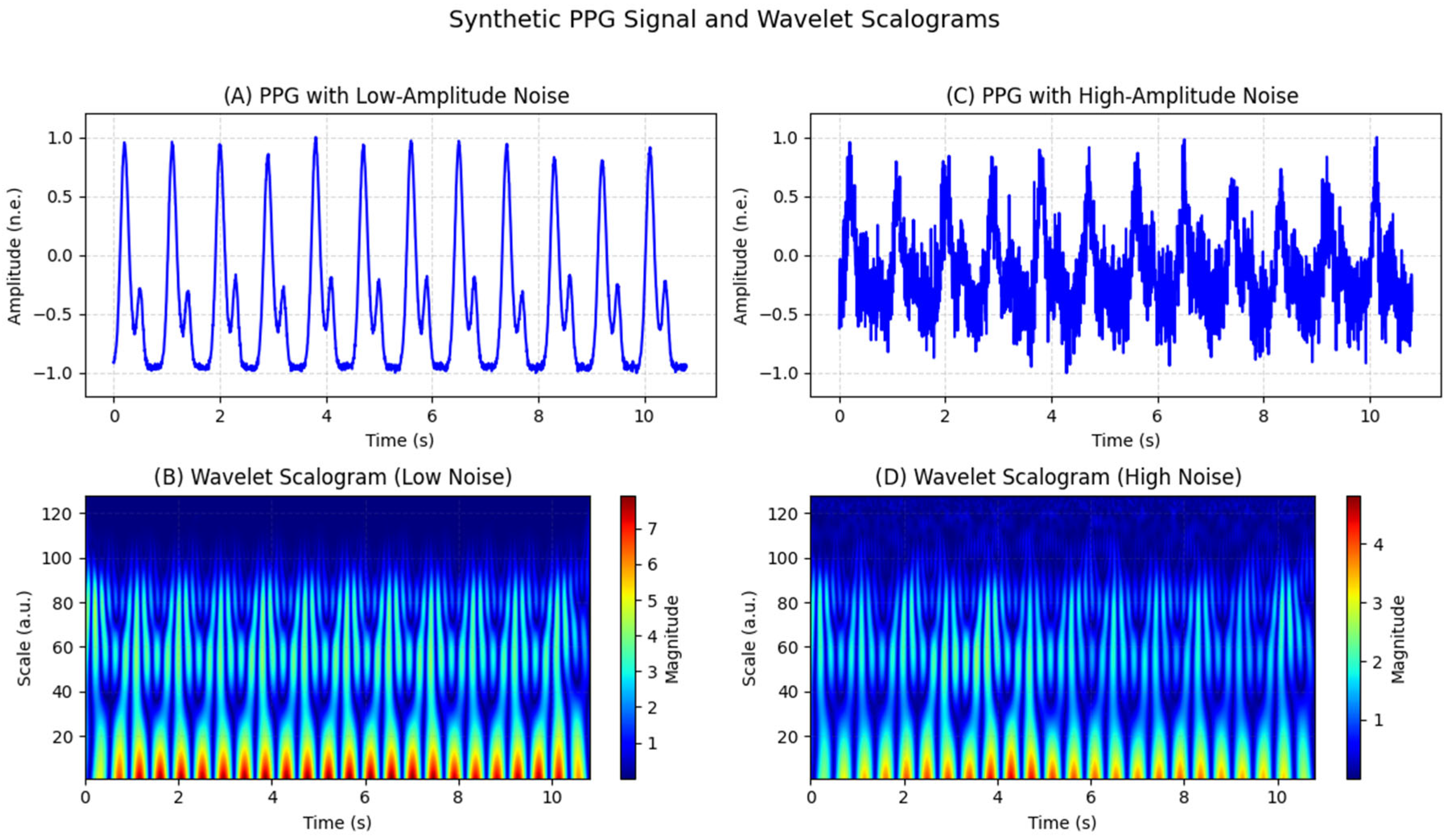

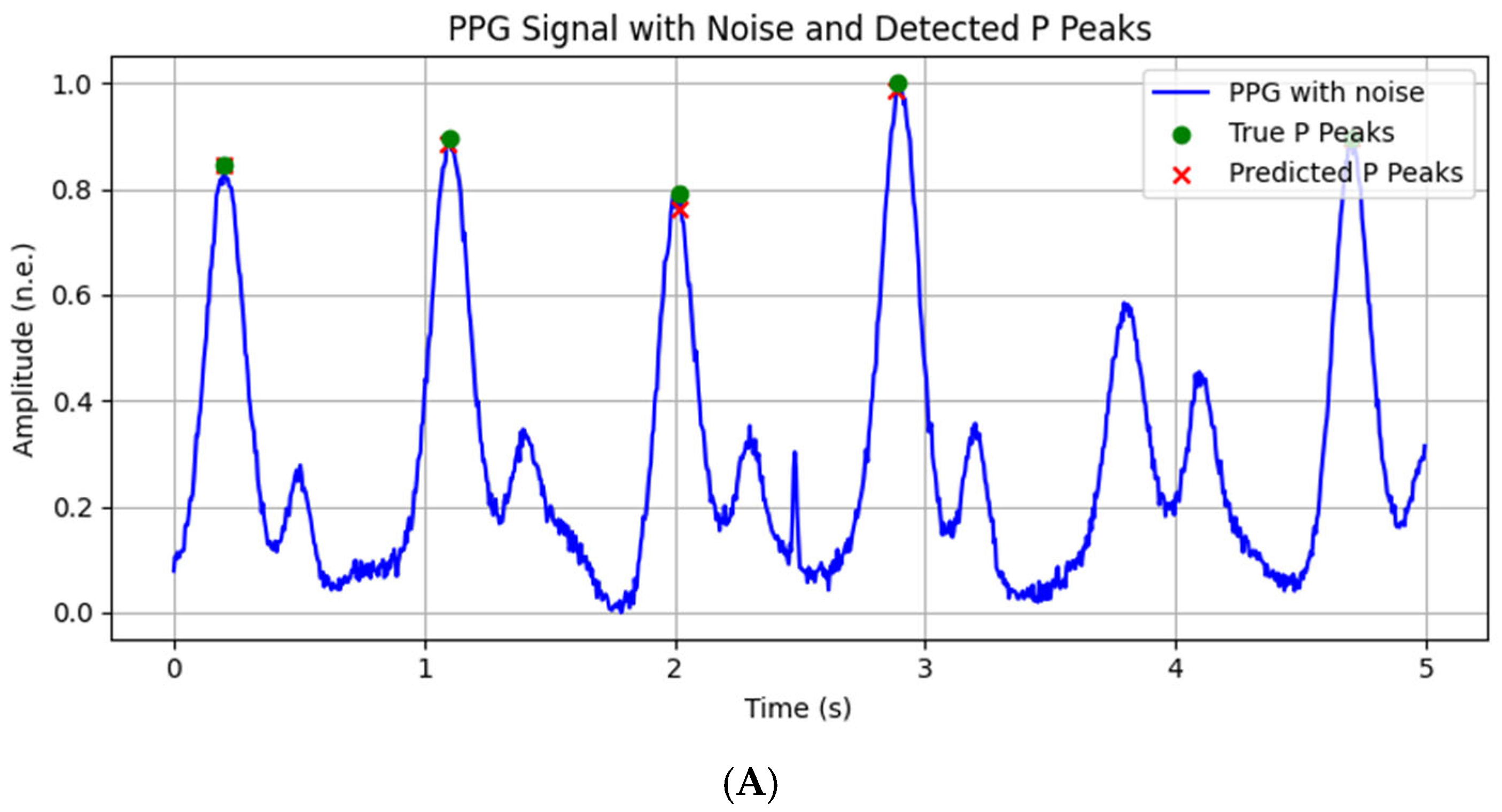

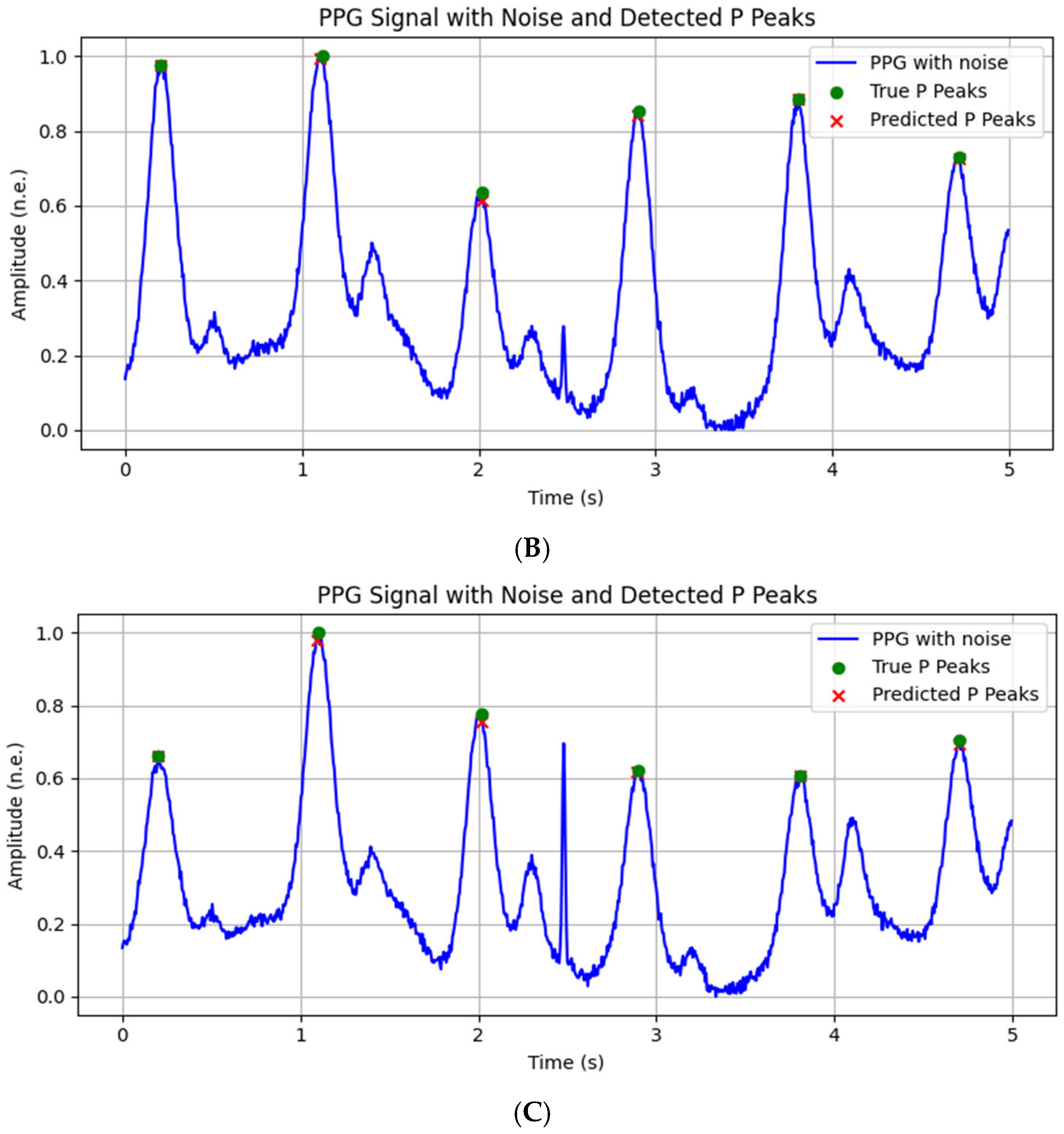

Simulation and noise addition

For the purpose of testing and evaluating the proposed neural architectures, the study used both real and simulated PPG signals, generated by the author through a previously developed algorithm for synthesis of pulse cycles with adjustable parameters such as amplitude, frequency and morphology [

22]. In order to mimic real measurement conditions, different types of noise were added to the simulated signals:

- (1)

Gaussian noise, simulating electronic noise from the sensor:

where

σ is the standard deviation that determines the intensity of the noise;

- (2)

Baseline drift was added through a sinusoidal component, mimicking the effects of breathing and positional changes:

where

is the amplitude of the drift,

—its frequency,

t—time, and

φ—initial phase.

- (3)

Motion artifacts are often impulsive or large amplitude displacements:

where

—standard deviation, determines the noise intensity and effective width of each pulse;

—amplitude of the

i-th motion atifact;

—its temporal position;

The final noisy PPG signal is thus expressed as: