Abstract

The coexistence of heterogeneous congestion control algorithms causes network unfairness and performance degradation. However, existing solutions suffer from the following issues: poor isolation reduces the overall performance, while sensitivity to tuning complicates deployment. In this work, we propose Warbler, a machine learning-driven active queue management (AQM) framework. Warbler classifies flows based on traffic characteristics and utilizes machine learning to adaptively control the bandwidth allocation to improve fairness. We implemented and evaluated the Warbler prototype on a programmable switch. The experimental results show that Warbler significantly improves the network performance, achieving a near-optimal Jain’s fairness index of 0.99, while reducing the delay to 60% of the baseline, cutting jitter by half, and saving 43% of buffer usage. In terms of scalability, it supports 10,000 concurrent long flows with latency below 0.7 s. The Warbler has a low cost and strong adaptability with no need for precise tuning, demonstrating its potential in dealing with heterogeneous CCAs.

1. Introduction

The coexistence of heterogeneous congestion control algorithms (CCAs) is a significant feature of modern networks [1]. Historical evolution has led to the coexistence of multiple generations of CCAs, from classical loss-based schemes (e.g., Reno [2], CUBIC [3]) to modern model-based approaches (e.g., BBR [4,5]). In addition, different application requirements drive the adoption of CCAs with fundamentally different optimization priorities, such as low latency (e.g., Vegas [6]) for interactive services and high throughput for data transfer. When CCAs with different bandwidth probes and congestion responses compete at the bottleneck, they typically suffer from bandwidth inequality, latency spikes, and performance degradation [7,8,9].

To solve the above unfairness problem, existing in-network solutions can be divided into two categories, according to whether the type of CCA is distinguished or not.

CCA-aware differentiated control strives for precision but is hindered by high costs and deployment challenges. Active probing techniques, such as P4air [8], are intrusive and can threaten stability, while P4CCI [9] and per-CCA Queueing [10] are hindered by their reliance on flawed assumptions, such as symmetric routing or unrealistic system prerequisites.

CCA-agnostic uniform control aims for simplicity, but the associated one-size-fits-all approach lacks isolation. Due to the inability to distinguish between CCAs, these schemes (e.g., Cebinae [11] and AHAB [12]) are often highly sensitive to parameters and may lose bandwidth in order to achieve consistency.

Thus, a critical challenge arises: how to achieve robust fairness and isolation among heterogeneous CCAs without relying on complex manual configuration. In this study, we propose Warbler, a machine learning-driven AQM framework. Unlike traditional approaches, Warbler aims to automatically classify flows based on distinctive traffic characteristics (buffer fingerprints) and adaptively control bandwidth allocation to restore fairness.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Novel Isolation Paradigm: Warbler introduces a buffer fingerprint-based isolation mechanism that physically separates aggressive flows from conservative ones, solving the poor isolation issue in conventional queues.

- (2)

- Automated Classification: Warbler proposes an unsupervised machine learning algorithm that enables the precise identification of CCAs with different buffer behaviors, achieving the objective of tuning-free deployment.

- (3)

- Comprehensive Evaluation: Warbler features a comprehensive evaluation framework combining quantitative analysis and visualization to rigorously assess the isolation benefits.

- (4)

- Hardware Validation: We implement Warbler on P4 programmable switches, validating its practical hardware deployability and effectiveness in ensuring fair bandwidth allocation.

2. Related Work

This study primarily involves research on three aspects: in-network active queue management (in-network AQM), congestion control algorithm identification (CCA identification), and clustering algorithms. References in each of these areas provide valuable insights and practical foundations.

2.1. In-Network AQMs

Existing in-network solutions have significant limitations in addressing the problem of CCAs’ unfairness. Methods based on probabilistic penalties, such as Cebinae, are sensitive to a multitude of parameters. Threshold-based schemes, such as AHAB [12], risk incorrectly penalizing benign large flows (or elephant flows). Those employing backward control signaling, such as FlowSail [13], incur additional network overhead, latency, and deployment compatibility challenges. Moreover, approaches that depend on high-precision timestamps, such as ABM [14], require stringent hardware and clock synchronization capabilities. Gomez et al. [15] address RTT unfairness using Jenks natural breaks for flow classification, but this comes at the cost of copying all packets for passive RTT measurement. FQ-CoDel [16], Gearbox [17], and HCSFQ [18] represent a class of technical approaches that attempt to simulate fair queuing (FQ) using a small number of finite queues. The common bottleneck for these algorithms lies in their packet-level processing granularity and excessive reliance on preset static thresholds. Furthermore, their lack of consideration for isolation leads to severe interference when handling heterogeneous CCAs.

2.2. CCA Identification

Existing approaches for identifying congestion control algorithms within the switch data plane predominantly rely on online flow classification; they face a challenge in terms of accuracy, real-time performance, overhead, and deployability. While machine learning-based solutions (e.g., P4CCI [9], random forest-based classification methods [19]) can effectively extract features for flow classification, they suffer from feature overlap, high state-maintenance overhead, reliance on external servers, and poor adaptability due to their static model design. Active probing schemes (e.g., P4air [8]) use intrusive interventions to identify CCAs, but their accuracy against unknown algorithms is dubious, their scalability is constrained, and they pose a risk of inducing network oscillations. Other proposals either hinge on an unrealistic “perfect classifier” assumption (Per-CCA Queueing [10]) or depend on resource-intensive kernel-level data collection pipelines and platform programmability (Dragonfly [20]), restricting their practical applicability and deployment scope. Moreover, most methods that use in-flight byte statistics implicitly assume path symmetry, such as Flowtamer [21]—an assumption that is often invalid in contemporary multi-path networks.

2.3. Clustering Algorithms

The core of Warbler is an online clustering mechanism designed to dynamically map network flows to available hardware queues. After a comprehensive evaluation of conventional clustering algorithms, we identified K-means [22] as the optimal foundational framework. Alternative methods were excluded based on specific performance constraints. Hierarchical [23] and spectral clustering [24] exhibit computational complexities of or higher, making them unfit for real-time network environments. Similarly, density-based solutions such as DBSCAN [25] cannot guarantee a fixed number of output clusters, violating our hardware-imposed requirements. Furthermore, probabilistic models (e.g., GMM [26]) and one-dimensional optimal partitioning algorithms (e.g., Ckmeans.1d.dp [27]) were deemed unsuitable due to their high computational costs, sensitivity to data distribution, and sorting dependencies, which limit their scalability. In contrast, K-means offers the low iterative overhead and direct implementation required for high-throughput low-latency applications, alongside the ability to enforce a predetermined cluster count (). Leveraging this efficiency, we reconfigured the centroid design and distance metrics to align specifically with the network flow characteristics, thereby establishing a mechanism that ensures scheduling fairness.

2.4. Comparison and Motivation

Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics and performance metrics of existing works in the field. Analyzing the data sources and core mechanisms reveals three key limitations in the existing technologies:

Table 1.

The key characteristics and performance metrics of existing AQMs.

- (1)

- High Overhead and Invalid Assumptions: Traditional algorithms rely on expensive per-packet measurements (e.g., RTT) and fragile “path symmetry” assumptions that often fail in multi-path networks.

- (2)

- Intrusiveness and Instability: Mechanisms such as probabilistic dropping or header modification (e.g., cwnd, ECN) compromise network transparency and risk inducing control loop oscillation.

- (3)

- Lack of Isolation: Current “one-size-fits-all” strategies lack awareness of CCAs, causing severe interference among heterogeneous flows.

In light of the limitations in existing AQM solutions and the critical need for isolation, a core question arises: can a low-overhead, tuning-free AQM be designed to ensure robust fairness and isolation for heterogeneous CCA flows?

In this study, we propose Warbler, a machine-learning-based AQM. Warbler employs an innovative unsupervised learning framework to analyze queuing behaviors, identifying flows to achieve dynamic isolation and fairness. Its key advantages include

- (1)

- Lightweight Feature Collection: This replaces expensive per-packet measurements with flow-based cumulative backlog—a core indicator of unfairness—significantly reducing the sampling and computational overhead.

- (2)

- Non-Intrusive Isolation: This avoids active dropping or header modification; instead, it classifies and maps heterogeneous flows to independent physical queues to minimize interference.

- (3)

- Fully Automated Operation: This operates solely on local data without assuming path symmetry; the unsupervised architecture minimizes the reliance on manual parameter tuning, enhancing the deployment flexibility and robustness.

3. The Warbler Scheme

This section details the system design of Warbler. Warbler includes a lightweight closed-loop mechanism comprising data collection, intelligent clustering, and adaptive scheduling to achieve the fair isolation of heterogeneous CCA flows. Specifically, Section 3.1 elucidates the strategies for traffic isolation and scheduling. Subsequently, Section 3.2 discusses how unsupervised algorithms are utilized to translate flow characteristics into scheduling instructions.

3.1. Queue Management and Scheduling Model

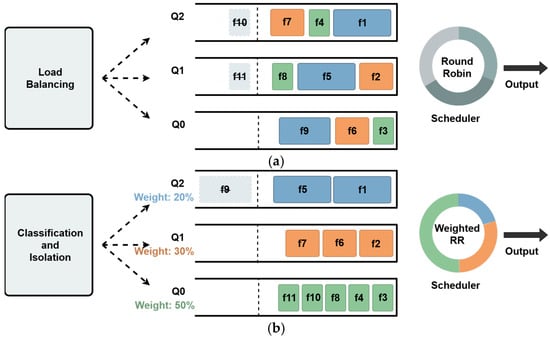

Figure 1 compares traditional load balancing with the Warbler mechanism. The traditional strategies use load balancing without differentiating the flow congestion. Consequently, bandwidth is dominated by backlog size; for instance, flow unfairly implicitly secures 60% of the bandwidth due to its high backlog.

Figure 1.

Schematic comparison of active queue management. (a) Traditional load balancing: oblivious queuing and Round-Robin scheduling. (b) Warbler: classification-based isolation and flow-count weighted scheduling.

In contrast, leveraging the classification results, Warbler isolates flows based on aggressiveness. Bandwidth is allocated based on active flow counts rather than simple Round-Robin. This restricts aggressive flows (, ) to a shared 20% limit, while protecting conservative flows (50% share) from starvation. This minimizes intra-queue variance and ensures fair bandwidth distribution.

Evidently, the effectiveness of Warbler depends on the flow classification accuracy. The critical challenge for Warbler is effectively translating the intrinsic patterns of backlog features into accurate classification decisions. To solve this, we propose an unsupervised learning-based flow identification algorithm that enables the automatic clustering of CCA types without human supervision.

3.2. Flow Identification via Unsupervised Learning

Warbler reconstructs the underlying clustering logic to deliver key innovations: it utilizes a relative error metric to eliminate the unfairness caused by flow scale disparities and employs a parallelized initialization mechanism to achieve rapid convergence and high stability.

3.2.1. Feature Definition and Extraction

Feature Vector: We denote the backlog of flow by (). The values of all target long-lived flows are collected to form a dataset . Given that the switch data plane manages buffers using fixed-size cells (80 bytes for Tofino 1 [28], 160 bytes for Tofino 2 [29]), is quantified in the implementation as the number of cells occupied by the flow’s packets.

The Number of Target Clusters: is fixed and equal to the number of physical queues at the bottleneck port.

Cluster: This corresponds to a physical queue, denoted as , where . It contains flows from the dataset.

Cluster Centroid: The weighted mean of the backlog values of all flows within cluster is denoted as .

For a data point and the centroid of its corresponding cluster, the squared relative error (SRE) is defined as

The objective function of the sum of squared relative errors (SSRE) for the entire dataset is defined as

3.2.2. Optimization of Clustering Process

The process begins by selecting initial centroids and running K-means iterations in parallel and concludes with a constraint-aware decision arbitration.

Phase 1: Generating Initial Centroids with Multiple Strategies.

This step involves selecting data points from the dataset to serve as the initial centroids, denoted , where . different sets of these centroids are generated in parallel to enhance the robustness; here, .

Conservative: We adopt the current flow-to-queue mapping as the initial configuration, representing the case of minimal change.

Far centroid [30]: We initialize centroids far apart to start from a better distribution and reduce poor local optima.

Random: We employ random initialization to ensure diversity among starting points.

Phase 2: Running K-means Instances in Parallel.

For each of the initialization schemes generated in Step 1, the K-means iterative algorithm is executed independently.

Assignment Step: In this step, each data point is assigned to the cluster that minimizes its squared relative error (SRE):

Update Step: The centroid for each newly formed cluster is then recalculated as

The algorithm iterates between the assignment and update steps until the cluster assignments stabilize (i.e., no longer change) or a predefined maximum number of iterations is reached. The final stable cluster assignment result is denoted as .

Phase 3: Evaluating and Selecting the Best Cluster.

After all parallel K-means instances have converged, we calculate the final sum of squared relative error (SSRE) for each resulting partition , where .

The baseline SSRE, calculated under the current physical queue mapping, is denoted as . The partition scheme with the greatest improvement in SSRE is selected as the optimal solution .

This partition is then applied to the data plane’s physical queue mapping. If the parallel instances do not provide effective improvement, the current mapping is retained.

The periodic execution of these three phases forms a dynamic control loop. For a specified flow, its backlog needs to converge to the centroid of the queue; otherwise, it will be moved to other queues. Using classification and isolation, Warbler achieves the goal of reducing inter-CCA interference while providing bounded fairness within classes.

3.2.3. Comparative Analysis

The core distinction between Warbler and traditional K-means lies in their objective functions.

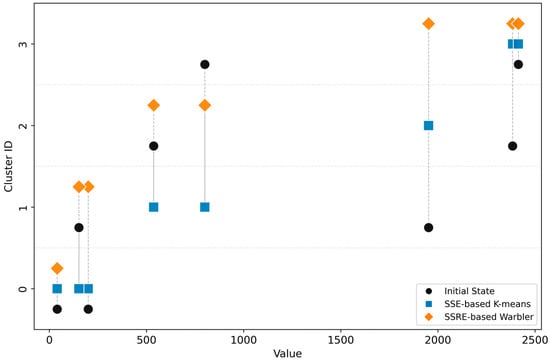

The traditional K-means algorithm adopts the sum of squared errors (SSE) as its metric, which is susceptible to scale effects, leading to defective clustering. For example, it may group data points (40, 152, 200) together due to their small absolute difference, while splitting data points (1952, 2384, 2414) into two clusters, as illustrated in Figure 2. This can produce clusters with, for instance, a fivefold scale difference between values such as 40 and 200.

Figure 2.

Comparison of clustering results: SSE-based K-means vs. SSRE-based Warbler.

In contrast, Warbler uses the relative value SSRE as its metric. It puts 1952, 2384, and 2414 together while separating outliers, such as 40. This clustering scheme minimizes the disparity in intra-cluster member values.

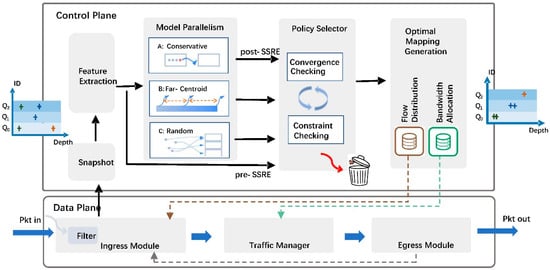

4. System Implementation

Warbler has been implemented on programmable switches [31] using a loop architecture based on perception, evaluation, and decision, as shown in Figure 3. The implementation is described in detail below.

Figure 3.

System architecture for the implementation of Warbler in a programmable switch.

- Step 1: Identify Long Flow.

In the data plane Ingress pipeline, the filter module continuously monitors the traffic to identify long flows. This process can utilize a mature and scalable data structure, such as Count Min Sketch (CMS [32]), to approximately track statistics. This study focuses on processing long flows.

- Step 2: Collect Data.

The control plane periodically collects long flows’ information: the distribution (i.e., the physical queue in which they are) and the backlog. The backlog of each flow refers to the number of cells that are buffered in the queue. A weighted moving average (WMA) scheme can be used to remove transient noise.

- Step 3: Run K-means in parallel.

In this step, the control plane executes the selection process as follows.

- Firstly, it constructs feature vectors for each long flow, including the scale of backlog packets and their respective queues.

- Next, it performs the various K-means strategies in parallel to generate candidate clustering schemes.

- Then, it evaluates each candidate clustering scheme based on its SSRE value and selects the one that meets the constraints and has the highest improvement. All others are discarded.

- Step 4: Generate Configuration Tables.

The control plane generates the following tables based on the optimal clustering strategy and distributes them to the data plane.

Flow Distribution Table: This implements new flow-to-queue mapping based on the clustering results.

Bandwidth Allocation Table: This sets the bandwidth of each queue proportionally based on the number of allocated flows.

- Step 5: Execute the New Strategy.

At the Ingress pipeline in the data plane, the arriving packets will enter their specified queues following the updated Flow Distribution Table.

Under the guidance of the Bandwidth Allocation Table, the TM module adopts scheduling algorithms such as Weighted Round-Robin (WRR) to forward packets from queues.

The Egress pipeline feeds back the digest packets based on the actual transmission to update real-time backlogged packet information at the Ingress module.

5. Performance Evaluation

The testbed for evaluating Warbler uses the EdgeCore AS9516-32D programmable switch with Tofino2 ASIC and servers equipped with Mellanox ConnectX-4 NICs. The experiment aimed to verify the functionality, quantify the comprehensive performance gains, and analyze the time complexity.

To evaluate the robustness, we selected three representative algorithms covering the primary congestion control categories, which exhibit distinct backlog dynamics.

CUBIC (Loss-based): CUBIC increases its window cubically until packet loss occurs. This aggressive probing saturates the bottleneck buffer, resulting in high and oscillating queue backlogs. NewReno employs a linear “Additive Increase” approach, resulting in slower window growth.

Vegas (Delay-based): Vegas monitors RTT to maintain a small fixed number of packets in the queue. By adjusting its rate when delay increases, it sustains a low and stable queue backlog.

BBR (Model-based): BBR estimates the Bandwidth-Delay Product (BDP) to pace packets near the optimal operating point. While it avoids buffer filling, its probing phases can still generate moderate or fluctuating backlogs.

Fairness is measured using Jain’s Fairness Index (JFI) [33]. Given a set of flows, where represents the average throughput of flow , the index is defined as

As the cluster number in K-means is naturally dictated by the switch’s physical queue count, the control plane automatically obtains this value by reading the data plane registers.

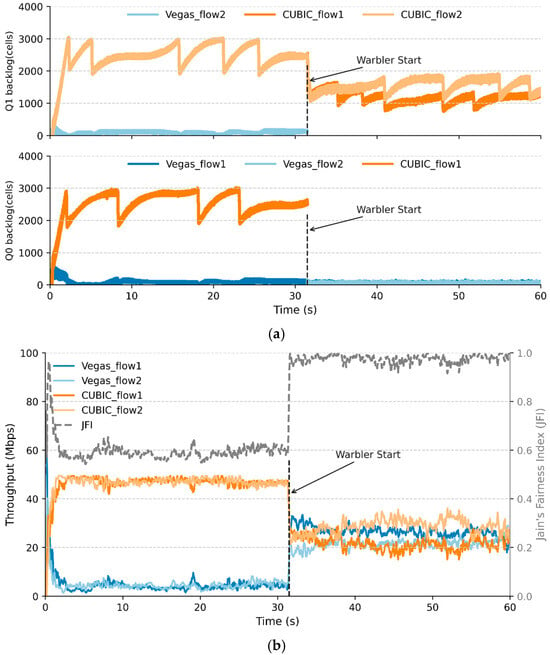

5.1. Functionality Validation

As shown in Figure 4, two queues (Q0, Q1) share a 100 Mbps bottleneck port, with each queue initially containing a CUBIC flow and a Vegas flow. The RTT for both CUBIC and Vegas flows is 10 ms, and the buffer size for each queue is set to 3000 cells. The backlog of each flow is counted as the number of “cells”.

Figure 4.

Warbler intervention in a 2 CUBIC + 2 Vegas flow scenario. (a) Backlog over time. (b) Throughput and fairness (JFI) over time.

Before = 30 s, CUBIC occupies the vast majority of its queue buffer and correspondingly obtains a bandwidth that far exceeds its share, resulting in an extremely low JFI. The activation of Warbler immediately corrects CUBIC’s bandwidth suppression on Vegas, increasing the system’s JFI from 0.6 to nearly 1, without the need for per-packet scheduling or marking. The result indicates that the Warbler classification and isolation strategy based on backlog is effective in improving fairness.

5.2. Handling Heterogeneous CCA Flows

In order to systematically evaluate the benefits of adopting Warbler, two parallel configurations, one “without Warbler” and the other “with Warbler”, are established under the same traffic distribution. Three physical queues (Q0, Q1, Q2) share a single 100 Mbps bottleneck port. Six independent flows participate in the competition, with two each for CUBIC, BBR, and Vegas. The RTT for each flow is 10 ms, and the buffer size for each queue is 5680 cells.

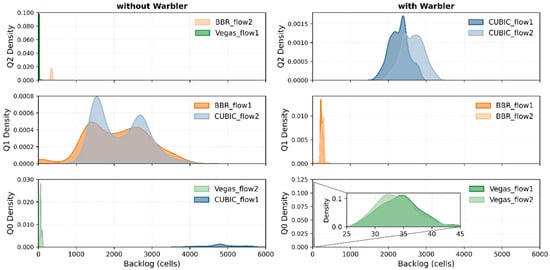

Figure 5 shows the kernel density estimation (KDE) of the backlog for each flow in queues Q0, Q1, and Q2. The plot on the left shows a baseline system (“without Warbler”), where load-balancing alone leads to severe resource contention among heterogeneous flows. The aggressive CUBIC flow saturates the Q0 buffer, while a competing BBR flow inflates Q1’s buffer to a comparable excessive level.

Figure 5.

The KDE of per-flow backlog for a mix of CUBIC, BBR, and Vegas flows, without and with Warbler.

The plot on the right shows the converged state with Warbler. Warbler automatically classifies and segregates flows by congestion control algorithms: it assigns low-buffer Vegas flows to Q0 and confines aggressive CUBIC flows to Q2. In particular, the buffer-prone BBR flows are isolated in Q1 and maintain a minimal stable buffer occupancy.

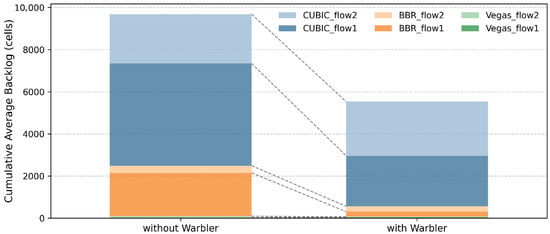

Warbler reduces the total buffer usage by approximately 40% by isolating aggressive flows and protecting well-behaved ones. Specifically, this mechanism decreases the buffer occupation of CUBIC_flow1 by 50% and eliminates BBR’s defensive inflation, which in turn leads to an 87.5% drop in buffer usage for BBR_flow1, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The cumulative average backlog of each flow, without and with Warbler.

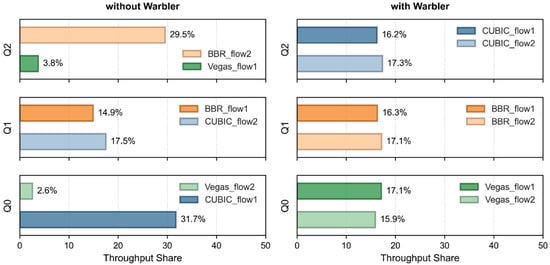

Furthermore, we compare each flow’s share of total throughput with its queue’s backlog distribution. As shown in Figure 7, in the baseline scenario (without Warbler), a significant throughput inequality appears in Q0 and Q2, consistent with their unbalanced backlogs. Once Warbler is enabled, and the system has converged, the JFI jumps from 0.69 to 0.99. Although the absolute buffer levels vary by CCA type, flows within the same category begin to share bandwidth equally in their respective queues. The observed alignment between throughput share and buffer distribution indicates that classifying and isolating flows by backlog is effective and well-founded.

Figure 7.

Per-flow share of the total throughput for a mix of CUBIC, BBR, and Vegas flows, without and with Warbler.

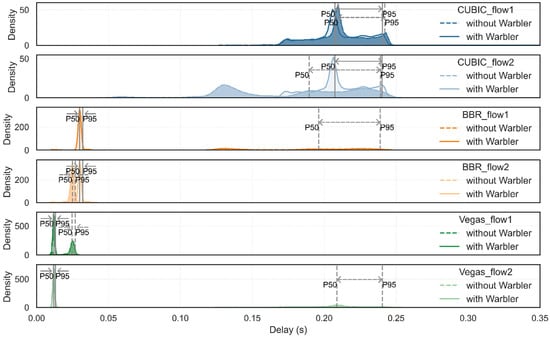

Figure 8 presents the per-flow delay distributions under conditions with and without Warbler, along with the median (P50) and the 95th percentile (P95) latencies. In the baseline, the BBR and Vegas flows coexisting with CUBIC exhibited a high-latency state with elevated P50 values. With Warbler enabled, the delay distributions for all algorithms became more concentrated, with tighter tails. The spread between P50 and P95 narrowed significantly, indicating a marked improvement in delay jitter.

Figure 8.

The KDE of per-flow latency for a mix of CUBIC, BBR, and Vegas flows, without and with Warbler.

As summarized in Table 2, the overall performance of the system shows a significant improvement after the introduction of Warbler. The jitter metric is calculated using a robust quantile-based method, defined as the average difference between P95 and P50 across all flows. The results demonstrate that Warbler effectively constrains the excessive aggressiveness of dominant flows, isolates and protects mild flows, and thereby mitigates cross flow interference. Consequently, buffer occupancy, average latency, and jitter are substantially reduced, while the JFI shows a notable enhancement.

Table 2.

Overall performance improvements after introducing Warbler.

5.3. Compare with Other AQMs

Existing AQM solutions for CCA unfairness typically use the statistical average of JFI as the evaluation metric. However, this metric can obscure a critical issue: flow isolation allows inter-flow interference to persist, which manifests as significant instantaneous fluctuations in throughput and delay. To highlight the isolation capacity of the Warbler, we compare the performance of FQ-CoDel, Cebinae, and our proposed Warbler algorithm when handling NewReno flows with different RTTs.

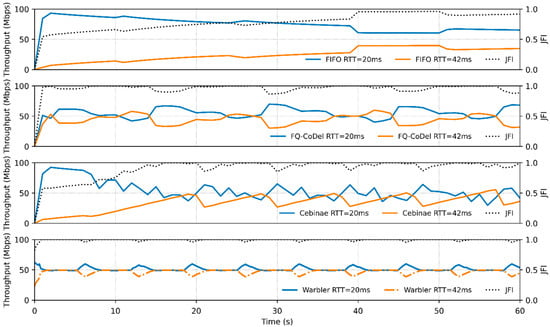

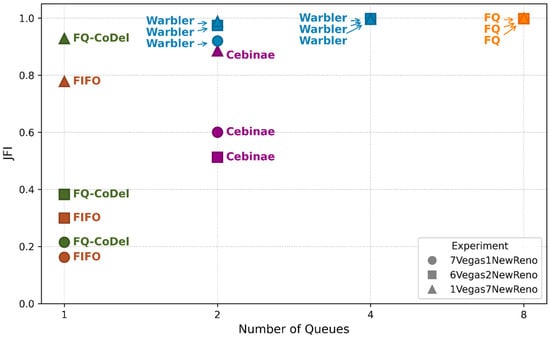

Figure 9 and Figure 10, respectively, illustrate the throughput/JFI and the delay over time for two flows with RTTs of 20 ms and 42 ms under different AQMs. At 100 Mbps bottleneck capacity, Warbler and Cebinae use dual queues (~1500 cells/queue), whereas FIFO and FQ-CoDel use a single 3000-cell queue. The analysis of the results is as follows.

Figure 9.

Throughput and JFI over time for various AQMs handling NewReno flows with different RTTs.

Figure 10.

Delay over time for various AQMs handling NewReno flows with different RTTs.

As a baseline, the FIFO queue exhibits pronounced RTT unfairness: the lower-RTT flow (20 ms) nearly monopolizes the bandwidth. Its delay trajectory is highly correlated with that of the other flow, indicating strong coupling and interference within the single queue.

FQ-CoDel improves the fairness to some extent but introduces significant throughput oscillations due to its single-queue architecture. To control the queuing delay, FQ-CoDel induces more frequent packet drops, resulting in more volatile sawtooth-like delay fluctuations compared to FIFO.

Employing an aggressive queue-management strategy—dropping packets immediately after detecting that a flow exceeds its fair share—Cebinae maintains a queuing delay near zero, causing its delay curve to align closely with the base RTT. However, this frequent-loss mechanism forces the sender to repeatedly shrink its congestion window, preventing full link utilization. Consequently, while the JFI is close to 1, the aggregate throughput stabilizes at approximately 88.3 Mbps, leading to over 10% bandwidth underutilization.

Warbler achieves effective flow isolation with two queues. The two flows maintain nearly equal throughput shares, and their delay trajectories are largely independent, demonstrating that the inter-flow coupling is effectively weakened. The throughput oscillations observed are transient effects caused by the lower-RTT flow that recovers faster from packet loss and temporarily captures more bandwidth. Overall, the corresponding JFI curve and the decoupled delay trajectories confirm that Warbler reduces interference, delivering superior fairness and scheduling performance.

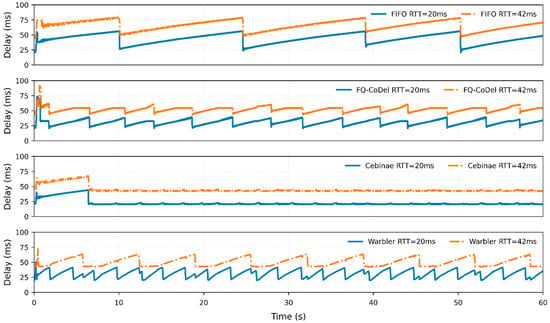

Furthermore, we ran three experiments (7 Vegas/1 NewReno, 6 Vegas/2 NewReno, 1 Vegas/7 NewReno) to evaluate each AQM’s ability to manage inter-flow contention under varying mixes of “aggressive” and “conservative” flows. Each CCA‘s RTT was 10 ms. The bandwidth at the bottleneck port was 100 Mbps. We fixed the total buffer size to ensure a fair comparison despite varying queue counts. Specifically, the per-queue buffer was set to 1, 2, 4, and 8 BDP for configurations with eight, four, two, and one queues, respectively (where 1 BDP ≈ 780 cells).

The baseline system using a single FIFO queue exhibited a low JFI. In comparison, while the FQ-CoDel mechanism improved the fairness to some extent, its effect was still limited, as shown in Figure 11. When aggressive traffic was a minority, Cebinae increased the JFI value by 0.43 compared to FIFO. However, when aggressive traffic was a majority, Cebinae could not accurately distinguish flows that exceeded the bandwidth fair share and could starve conservative traffic, thus resulting in a worse improvement effect than FQ-CoDel. In contrast, even with only two queues, Warbler could effectively isolate flows and significantly improve the fairness. Its performance expanded with the increase in queues, smoothly approaching the ideal fairness of the fair queuing (FQ) scheme.

Figure 11.

JFI of queue management algorithms across various traffic mixes.

5.4. Time Complexity

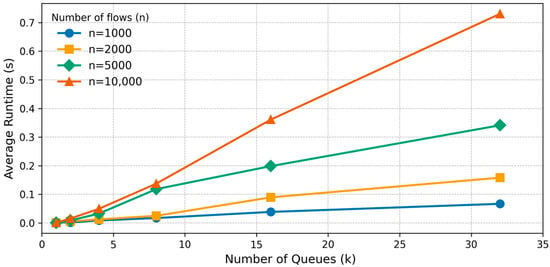

To evaluate the time complexity of Warbler’s machine learning algorithm, we measured its average runtime delay on the control plane of the programmable switch. This parameter reflects the processing overhead per-iteration, and the total number of iterations and is primarily governed by the number of queues , the number of long flows , and the hardware capabilities.

The results show that the delay in the control plane grows roughly linearly with the number of queues () and the number of flows (), with exerting the stronger influence. For typical scales (, ), the delay ranges from milliseconds to a few hundred milliseconds, sufficient for a second-level control cadence. At larger scales (, ), the delay is about 0.3–0.7 s, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

K-means runtime scaling with clusters () and sample size ().

As established by previous work [21,34], long-lived flows (lasting 10–20 s) are a minority by count (1–5%) but a majority by volume. After being identified by mechanisms such as Count Min Sketch, their number is relatively sparse. For a network carrying hundreds of thousands of flows, this translates to a typical long-flow scale of 1 to 10 k. The results indicate that Warbler has the potential for practical deployment.

6. Discussion and Limitations

Based on the experimental outcomes, this section provides a discussion on the implications of our findings. We proceed by evaluating Warbler’s scalability and robustness mechanisms in detail, followed by a critical reflection on the study’s limitations.

6.1. Discussion on Adaptability

First, regarding system overhead and scalability, Warbler is designed for data-intensive scenarios such as distributed machine learning training clusters or bulk data migration networks. In these environments, traffic is dominated by long-lived, high-bandwidth flows, making the management of elephant flows the critical determinant of system performance. This design strategy aligns with the well-documented heavy-tailed nature of data center traffic [34], where a small fraction of flows contributes to the vast majority of the load. Similar strategies prioritizing elephant flow management have been widely adopted in recent works [11,17,18] to optimize network throughput and latency. Warbler selectively applies granular management only to these high-impact flows. Consequently, the system eliminates the high overhead associated with maintaining state registers for every flow; instead, all newly arriving data—predominantly short-lived “mice” flows—are transmitted through a default queue with minimal processing. State recording for control plane retrieval is triggered only when the data plane filter (e.g., CMS) identifies elephant flow characteristics (such as exceeding 10 packets [21]). This on-demand processing mechanism significantly reduces the resource consumption, thereby enhancing system scalability. Unlike P4CCI and AHAB, which rely on costly per-packet monitoring, or ABM, which maintains per-flow states, our approach minimizes the data plane overhead. This reduction is critical, as it makes it computationally feasible for the control plane to apply machine learning algorithms across a massive number of concurrent flows.

Second, Warbler demonstrates inherent robustness against the unfairness caused by RTT heterogeneity. In traditional algorithms, unfairness stemming from RTT discrepancies ultimately manifests as variations in buffer occupancy at the switch level. Warbler’s core mechanism performs dynamic isolation and processing by directly anchoring on the actual backlog size of the flows (as shown in Figure 4), thereby shielding the system from the specific causes of the backlog (whether due to the aggressiveness of the congestion control algorithm or physical RTT differences). Experiments omitted from this work show that Warbler is effective in identifying and restricting flows which, due to RTT advantages, excessively occupy buffer resources.

6.2. Robustness Analysis Under Anomalous Interference

To address network traffic burstiness, the system leverages data- and control-plane collaboration within a multi-time-scale mechanism to ensure robustness.

State Retention and Smoothing within Sampling Cycles. At the implementation level, to accurately maintain the count of active flows, we introduced a counter to track the number of received packets within a cycle. The system employs a “double-check” mechanism: a flow is determined to have ended only when both the reception counter and the queue backlog counter return to zero simultaneously. This design not only maintains accurate flow states but also produces an engineering “smoothing effect.” This effectively masks high-frequency jitter within a sampling cycle caused by application flows (such as video stream ON/OFF cycles), thereby preventing erroneous flow termination judgments.

Control Plane-Based Periodic Re-mapping. If a flow exhibits a significantly higher throughput rate than other flows in the same queue after entry, the control plane will detect this anomaly and re-map it to a more appropriate queue at next cycle. Although this mechanism involves a lag of one sampling cycle, it strictly confines the impact of congestion to a single queue within a single cycle, thus effectively blocking high-throughput flows from continuously occupying resources meant for low-throughput flows over the long term.

Future Extension. Isolation strategy for abnormal traffic. The P4-based data plane ensures the architecture’s scalability, allowing for future enhancements against abnormal traffic. Upcoming extensions will integrate robust isolation strategies to counter ultra-high-speed TCP, unresponsive UDP, and malicious flows. By identifying and redirecting aggressive traffic to separate queues with Strict Bandwidth Policing, the system can fundamentally eliminate the starvation of normal TCP flows. This capability highlights the architecture’s potential to evolve and effectively manage complex heterogeneous traffic environments.

6.3. Limitations and Future Work

The proposed Warbler algorithm has shown strong capability in identifying and managing heterogeneous congestion control flows. However, its reliance on the control plane for data processing and machine learning tasks introduces inherent performance bottlenecks. Consequently, the system suffers from second-level processing delays, limiting its ability to handle transient traffic bursts effectively.

Future work will focus on exploring the feasibility of offloading Warbler to the programmable data plane. This direction poses two main challenges: first, redesigning the algorithm under hardware constraints (e.g., the lack of floating-point operations in P4); second, efficiently managing per-flow states within the switch’s limited resources. The ultimate goal is to achieve a balanced trade-off between maintaining classification accuracy and minimizing hardware resource usage, enabling a high-efficiency autonomous decision system capable of operating at line rate.

7. Conclusions

Adopting a classify-and-isolate paradigm, Warbler utilizes an improved K-means algorithm to cluster flows based on backlog indicators, constrain aggressive and conservative flows to their respective queues, and thus reduce inter-CCA interference. The continuous monitoring and migration control process provides long-term stability support. Hardware experiments confirm that Warbler significantly outperforms traditional mechanisms, particularly in complex mixed-traffic scenarios. In contrast to the severe JFI fluctuations (0.2–0.9) observed in FIFO and FQ-CoDel, Warbler leverages accurate identification and isolation to maintain a JFI exceeding 0.98 with few physical queues. Furthermore, Warbler breaks the fairness–performance trade-off: it improves fairness, while simultaneously reducing the latency by 39.5% and the buffer occupancy by 42.9%, proving itself to be a robust solution for heterogeneous CCA unfairness. In summary, compared with methods that rely on invasive intervention or complex parameter tuning, Warbler has the advantages of a low sampling cost, no need for precise parameter tuning, and adaptability to multiple scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G.; methodology, C.D.; software, Y.G.; validation, Y.L.; formal analysis, C.D.; data curation, Y.L.; writing, Y.G.; funding acquisition, Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “333” project of Jiangsu Province, grant number 2022096, the Future Network Scientific Research Fund Project, grant number FNSRFP-2021-YB-55, and the Outstanding Scientific and Technological Innovation Team of Colleges and Universities in Jiangsu Province.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mishra, A.; Rastogi, L.; Joshi, R.; Leong, B. Keeping an eye on congestion control in the wild with nebby. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM 2024 Conference, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 5–9 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, V. Berkeley TCP evolution from 4.3-tahoe to 4.3-reno. In Proceedings of the 18th Internet Engineering Task Force, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1–3 August 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, S.; Rhee, I.; Xu, L. CUBIC: A new TCP-friendly high-speed TCP variant. ACM SIGOPS Oper. Syst. Rev. 2008, 42, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardwell, N.; Cheng, Y.; Gunn, C.S.; Yeganeh, S.H.; Jacobson, V. BBR: Congestion-based congestion control. Queue 2016, 14, 20–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliev, V.; Wu, B.; Hsiao, L.; Cardwell, N.; Cheng, Y.; Yeganeh, S.H.; Jacobson, V. BBRv2: A model-based congestion control. In Proceedings of the IETF 106th Meeting, Singapore, 16–22 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brakmo, L.S.; O’Malley, S.W.; Peterson, L.L. TCP Vegas: New techniques for congestion detection and avoidance. In Proceedings of the Conference on Communications Architectures, Protocols and Applications (SIGCOMM ’94), London, UK, 31 August–2 September 1994; pp. 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, R.; Mukerjee, M.K.; Seshan, S.; Sherry, J. Modeling BBR’s interactions with loss-based congestion control. In Proceedings of the Internet Measurement Conference (IMC ’19), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 21–23 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Turkovic, B.; Kuipers, F. P4air: Increasing fairness among competing congestion control algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 28th International Conference on Network Protocols (ICNP), Madrid, Spain, 13–16 October 2020; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kfoury, E.; Crichigno, J.; Bou-Harb, E. P4CCI: P4-based online TCP congestion control algorithm identification for traffic separation. In Proceedings of the ICC 2023—IEEE International Conference on Communications, Rome, Italy, 28 May–1 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mulla, Y.; Keslassy, I. Per-CCA Queueing. In Proceedings of the 2024 20th International Conference on Network and Service Management (CNSM), Arcaichon, France, 28 October–1 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Sonchack, J.; Liu, V. Cebinae: Scalable in-network fairness augmentation. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM 2022 Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 22–26 August 2022; pp. 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- MacDavid, R.; Chen, X.; Rexford, J. Scalable real-time bandwidth fairness in switches. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2024, 32, 1423–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zeng, C.; Hu, J.; Chen, K. Towards Fine-Grained and Practical Flow Control for Datacenter Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 31st International Conference on Network Protocols (ICNP), Reykjavik, Iceland, 10–13 October 2023; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Addanki, V.; Apostolaki, M.; Ghobadi, M.; Schmid, S.; Vanbever, L. ABM: Active Buffer Management in Datacenters. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM 2022 Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 22–26 August 2022; pp. 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, J.; Kfoury, E.F.; Mazloum, A.; Crichigno, J. Improving flow fairness in non-programmable networks using P4-programmable Data Planes. Comput. Netw. 2025, 266, 111339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeiland-Joergensen, T.; McKenney, P.; Taht, D.; Gettys, J.; Dumazet, E. The flow queue codel packet scheduler and active queue management algorithm (No. rfc8290), 2018. Available online: https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc8290.html (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Gao, P.; Dalleggio, A.; Xu, Y.; Chao, H.J. Gearbox: A hierarchical packet scheduler for approximate weighted fair queuing. In Proceedings of the 19th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 22), Renton, WA, USA, 4–6 April 2022; pp. 551–565. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Wu, J.; Braverman, V.; Stoica, I.; Jin, X. Twenty years after: Hierarchical {Core-Stateless} fair queueing. In Proceedings of the 18th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 21), Boston, MA, USA, 12–14 April 2021; pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- García-López, A.; Kfoury, E.F.; Gomez, J.; Crichigno, J.; Galán-Jiménez, J. Real-Time Congestion Control Algorithm Identification with P4 Programmable Switches. In Proceedings of the NOMS 2025 IEEE Network Operations and Management Symposium, Honolulu, HI, USA, 12–16 May 2025; pp. 1–6. 437. [Google Scholar]

- Carmel, D.; Keslassy, I. Dragonfly: In-flight CCA identification. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2024, 21, 2675–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Gondaliya, H.; Kumaar, L.; Bhatnagar, A.; Joshi, R.; Leong, B. Expanding the Design Space for in-Network Congestion Control on the Internet. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM 2024 Conference Posters and Demos, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 5–9 August 2024; pp. 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.; Seraj, R.; Islam, S.M.S. The k-means algorithm: A comprehensive survey and performance evaluation. Electronics 2020, 9, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, F.; Contreras, P. Algorithms for hierarchical clustering: An overview, ii. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2017, 7, e1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Zhou, S.; Xiong, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Zhu, E.; Cai, Z.; Xu, X. Multi-view spectral clustering with high-order optimal neighborhood laplacian matrix. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 34, 3418–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahsler, M.; Piekenbrock, M.; Doran, D. dbscan: Fast density-based clustering with r. J. Stat. Softw. 2019, 91, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Han, J. Probabilistic models for clustering. In Data Clustering; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 61–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Song, M. Ckmeans.1d.dp: Optimal k-means clustering in one dimension by dynamic programming. R J. 2011, 3, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljoby, W.A.; Wang, X.; Divakaran, D.M.; Fu, T.Z.; Ma, R.T.; Harras, K.A. DiffPerf: Toward Performance Differentiation and Optimization With SDN Implementation. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2023, 21, 1012–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshinaka, Y.; Koizumi, Y.; Takemasa, J.; Hasegawa, T. High-throughput stateless-but-complex packet processing within a tbps programmable switch. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 32nd International Conference on Network Protocols (ICNP), Charleroi, Belgium, 29–31 October 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Arther, D.; Vassilvitskii, S. k-means++: The advantages of careful seeding. In Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, New Orleans, LA, USA, 7–9 January 2007; pp. 1027–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Bosshart, P.; Daly, D.; Gibb, G.; Izzard, M.; McKeown, N.; Rexford, J.; Schlesinger, C.; Talayco, D.; Vahdat, A.; Varghese, G.; et al. P4: Programming protocol-independent packet processors. ACM SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev. 2014, 44, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Jiang, J.; Liu, P.; Huang, Q.; Gong, J.; Zhou, Y.; Miao, R.; Li, X.; Uhlig, S. Elastic sketch: Adaptive and fast network-wide measurements. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the ACM Special Interest Group on Data Communication (SIGCOMM ’18), Budapest, Hungary, 20–25 August 2018; pp. 561–575. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, R.K.; Chiu, D.M.W.; Hawe, W.R. A quantitative measure of fairness and discrimination. J. High Speed Netw. 1998, 7, 2022–2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kandula, S.; Sengupta, S.; Greenberg, A.; Patel, P.; Chaiken, R. The nature of data center traffic: Measurements and analysis. In Proceedings of the 9th ACM SIGCOMM Conference on Internet Measurement, Chicago, IL, USA, 4–6 November 2009; pp. 202–208. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.