Abstract

The containment of misinformation diffusion on social media is a critical challenge in computational social science. However, prevailing intervention strategies predominantly rely on static topological metrics or time-agnostic learning models, thereby overlooking the profound impact of temporal–demographic heterogeneity. This oversight frequently results in a “spatio-temporal mismatch”, where limited intervention resources are misallocated to structurally central but temporarily inactive nodes, particularly during non-stationary propagation bursts driven by exogenous triggers. To bridge this gap, we propose a Spatio-Temporal Deep Reinforcement Learning (ST-DRL) framework for proactive misinformation defense. By seamlessly integrating continuous trigonometric time encoding with demographic-aware Graph Attention Networks, our model explicitly captures the coupling dynamics between group-specific circadian rhythms and event-driven transmission surges. Extensive simulations on heterogeneous networks demonstrate that ST-DRL achieves a Peak Prevalence Reduction of 93.2%, significantly outperforming static heuristics and approaching the theoretical upper bound of oracle-assisted baselines. Crucially, interpretability analysis reveals that the agent autonomously evolves a “Preemptive Strike” strategy—prioritizing the sanitization of high-risk bridge nodes, such as bots, prior to event onsets—thus establishing a new paradigm for predictive rather than reactive network governance.

1. Introduction

The hyper-connected digital era has fundamentally transformed the landscape of information dissemination, yielding a dual-edged reality in which unprecedented access to knowledge coexists with the rampant proliferation of misinformation and disinformation [1]. In financial markets [2], healthcare [3], and democratic processes [4], false narratives can trigger flash crashes, erode public trust, and incite social unrest—posing systemic risks that demand computationally scalable and temporally adaptive intervention strategies. In response to these escalating challenges, the development of scalable and adaptive computational frameworks for Influence Minimization (IM) and targeted intervention in large-scale networks has emerged as a critical frontier in computational social science. The overarching goal is no longer merely reactive containment but proactive mitigation: intercepting harmful diffusion processes before they achieve critical mass, while accounting for the dynamic, heterogeneous, and often adversarial nature of real-world information ecosystems [5].

To address this challenge, algorithmic approaches have evolved through three distinct phases. The first, rooted in Kempe et al.’s seminal work, framed IM on static graphs using greedy or heuristic centrality measures such as degree and PageRank [6]. While theoretically sound under diffusion models like Independent Cascade, these methods implicitly assume topological and behavioral stationarity—a condition rarely met in real-world networks where user activity is bursty, circadian, and event-driven. Empirical studies confirm that static strategies suffer significant performance degradation when applied to dynamic environments, as they ignore the temporal availability of users during critical cascade windows [7]. A critical limitation of conventional influence minimization approaches lies in their treatment of users as homogeneous agents, ignoring the profound behavioral and functional diversity that shapes information propagation. In reality, social networks comprise heterogeneous actor types, including ordinary users, coordinated inauthentic accounts, influencers, and fact-checkers—each exhibiting distinct roles, motivations, and susceptibility to manipulation. Recent empirical analyses confirm that automated accounts disproportionately drive the early-phase spread of misinformation, while human users determine long-term cascade survival [8,9]. Moreover, demographic factors such as age, political affiliation, and geographic location significantly modulate information consumption and sharing behaviors [10,11].

In response, a second wave of research integrated deep reinforcement learning (DRL) with graph neural networks (GNNs), recasting IM as a sequential decision-making problem. Frameworks such as GCOMB [12] and RL4IM [13] demonstrated that topology-aware policies could achieve near-optimal influence containment on large-scale graphs. Subsequent advances enhanced structural modeling through heterogeneous graph learning [14] and budget-aware reward design [15]. However, a unifying limitation persists across these studies: they operate on static or temporally aggregated snapshots, treating node influence as time-invariant. This assumption, while simplifying computation, leads to resource misallocation—intervening on nodes that are structurally central but temporally inactive during the actual propagation phase.

Concurrently, a third line of inquiry in temporal graph representation learning has rigorously established that influence is intrinsically time-dependent. Pioneering models like TGAT [16] and TGN [17] introduced continuous-time encoding and memory-augmented attention to capture dynamic user interactions. These advances were rapidly adopted in misinformation detection [18,19] and rumor control [20,21], where temporal patterns proved decisive. Surveys and empirical analyses further confirm that static centrality metrics frequently misidentify key users, as influence fluctuates with circadian rhythms, bot activity, and real-world events [22]. However, these models remain largely static and lack mechanisms to adapt intervention strategies to real-time shifts in user roles. Effective intervention thus demands not only topological awareness but also role-aware temporal reasoning that explicitly differentiates between transient amplifiers, persistent spreaders, and credible refuters.

Yet, despite these parallel advances, a fundamental disconnect remains: no existing framework unifies continuous-time graph representation, dynamic heterogeneous modeling, and proactive DRL-based decision-making into a single, end-to-end system for misinformation mitigation. Current dynamic IM methods are either heuristic, such as activity-weighted centrality or reactive—triggering actions only after trend detection in discrete snapshots [7]. Even recent attempts to combine DRL with temporal graphs rely on coarse time discretization and lack mechanisms to anticipate future transmission windows [23]. In addition, to enable truly anticipatory intervention, the temporal representation must support prospective reasoning—forecasting not just who is active now, but who will be active and connected during the next critical phase of a cascade.

A critical limitation in current misinformation intervention strategies lies not only in model architecture but in operational timing: without synchronizing interventions with the heterogeneous temporal activity patterns of user groups, even state-of-the-art approaches risk inefficient resource allocation—directing efforts toward nodes that are effectively inactive during the intervention window. This spatio-temporal misalignment undermines both the timeliness and cost-effectiveness of containment efforts in real-world social networks, where user engagement exhibits strong circadian rhythms [24] and event-driven surges [25]. We propose ST-DRL, a novel framework that dynamically aligns intervention decisions with the continuous, heterogeneous dynamics of online information ecosystems. ST-DRL integrates two methodological innovations. First, we introduce a Continuous Trigonometric Time Encoding (CTTE) module that maps absolute and relative timestamps into a high-dimensional periodic space. This enables the policy network to capture recurring temporal motifs—such as diurnal activity cycles and proximity to real-world events—without discretizing time or relying on handcrafted temporal features, thereby preserving temporal continuity and improving generalization. Second, we develop a Dynamic Heterogeneous Graph Attention (DHGA) mechanism that adaptively recalibrates edge weights in the influence graph based on real-time interaction intensity and node-type heterogeneity—such as that between organic users and automated bots—extending recent advances in heterogeneous graph representation learning.

Graph Neural Network–Deep Reinforcement Learning (GNN-DRL) approaches have achieved substantial progress, demonstrating that learning deep-level representations of user nodes can significantly enhance the efficacy of in-fluence interventions. However, existing literature primarily applies Temporal Graph Neural Networks (TGNNs) to passive predictive tasks, failing to account for population heterogeneity in physical time and the counterfactual nature of intervention. ST-DRL addresses two critical limitations: the “Observer vs. Actor” discrepancy, where standard smoothing overlooks sparse, high-frequency signals (e.g., botnet spikes), and the “Spatio-Temporal Mismatch” in action spaces, where static optimization targets dormant nodes. To overcome these, ST-DRL integrates Continuous Trigonometric Encoding to capture specific behavioral phases and employs a Gated Fusion Mechanism that enforces temporal constraints to invalidate temporally infeasible actions. By jointly modeling node temporal availability and context-dependent influence propagation, ST-DRL reframes the intervention paradigm from static, topology-driven node selection to proactive, time-constrained resource allocation. This paradigm shift facilitates the timely containment of misinformation cascades while simultaneously maximizing the utility of constrained intervention budgets—a central challenge within computational social science and public communication.

2. Methodology

In this section, we present the ST-DRL framework. Our approach is designed to resolve the critical “Spatio-Temporal Mismatch” in misinformation intervention by learning a proactive policy that aligns suppression efforts with the non-stationary dynamics of the social ecosystem.

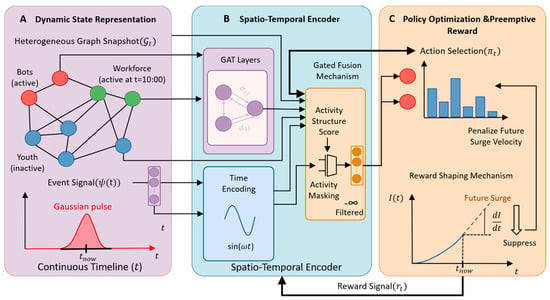

The overall architecture, illustrated in Figure 1, operates as a closed-loop system: Dynamic State Representation (Panel A): The agent perceives the heterogeneous graph snapshot and continuous environmental signals. Spatio-Temporal Encoder (Panel B): These multimodal inputs are processed via parallel streams—structural and temporal—and integrated via a Gated Fusion Mechanism that enforces physical activity constraints. Policy Optimization (Panel C): The agent executes actions based on the fused representation and optimizes its policy via a Reward Shaping Mechanism specifically designed to suppress the velocity of future infection surges.

Figure 1.

The Architecture of the ST-DRL Framework. (A) Dynamic State Representation: The agent observes a snapshot of the heterogeneous graph alongside a continuous timeline. Notably, high-risk Bot nodes (red) are active during the pre-event phase (indicated by on the rising edge of the Gaussian pulse), making them valid targets for intervention. (B) Spatio-Temporal Encoder: The neural architecture employs a dual-stream design. Structural features extracted via Graph Attention Networks (GAT) are fused with semantic time embeddings from the Trigonometric Encoder. Crucially, an Activity Masking mechanism is applied to filter out currently inactive nodes (setting their logits to ) to strictly enforce physical intervention constraints. (C) Policy Optimization: The agent generates an intervention policy . The reward function is shaped to penalize the future surge velocity of the infection curve, thereby training the agent to execute preemptive strikes before the outbreak peak occurs.

2.1. Modeling Non-Stationary Information Diffusion

We conceptualize the online social ecosystem as a dynamic heterogeneous graph, denoted as . Here, represents the set of users, denotes the static social backbone, contains time-invariant node attributes, specifically demographic group identities, and represents the time-varying activity status of the network. A fundamental premise of our work is that topological connectivity is a necessary but insufficient condition for information propagation; effective transmission is contingent upon temporal synchronization, where both the source and the target must be active simultaneously.

To capture this, we model the Activity Probability, , not as a stochastic Poisson process, but as a deterministic function governed by two coupled forces: endogenous circadian rhythms and exogenous event drivers. For any given node belonging to demographic group , its baseline activity is dictated by a superposition of harmonic functions representing group-specific behavioral phases, such as the distinct wake—sleep cycles of “Youth” and “Workforce”. Simultaneously, the system is subject to exogenous shocks, such as “breaking news” events. We model the impact of these events as a Gaussian pulse, , modulated by a group-specific sensitivity coefficient . This coefficient captures heterogeneous reactions; for instance, automated bots may maintain constant throughput regardless of external events, whereas real users exhibit sharp spikes in activity. Combining these factors, the unified activity probability is formalized in Equation (1).

In this formulation, the endogenous circadian rhythm is approximated via a Fourier series of order . The angular frequencies are set to and to capture diurnal which is 24 h and semi-diurnal cycles, respectively, such as the bimodal commute peaks characteristic of the “Workforce” group. Crucially, the phase shift parameter defines the temporal offset of peak activity; for instance, we assign to shift activity to late-night hours . The amplitude weight controls the intensity of these rhythmic fluctuations. Notably, automated accounts such as Bots are modeled with negligible amplitudes, reflecting their algorithmic, constant-throughput nature. Finally, to account for aleatoric uncertainty, we introduce a Gaussian noise term to adjust baseline sparsity. This formulation mathematically encapsulates the spatio-temporal mismatch, as a structurally central node may possess a near-zero activity probability during its dormant phase, rendering it an inefficient target for intervention.

Building upon this activity model, we adopt a modified Susceptible-Infected-Recovered (SIR) process to simulate the information cascade [26]. To reflect the “infodemic” nature of misinformation, the state transition from Susceptible to Infected is governed by a time-varying transmission rate, . We define as a function of the event intensity, , implying that during critical event windows, the cost of inaction increases exponentially as the virus spreads significantly faster than in dormant periods. Here, represents the baseline infectivity. The term serves as the amplification factor, implying that during the critical event window defined by the effective reproduction number surges significantly faster than during dormant periods.

2.2. Problem Formulation as a Budgeted MDP

To rigorously formalize the decision-making process, we model the intervention task as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) [27], defined by the tuple . In this framework, the is constructed not merely as a graph snapshot, but as a composite tuple available to the model at the beginning of each discrete time step . Here, represents the static topological structure; denotes the dynamic infection status of all nodes (where 1 indicates infected); is the observable activity mask indicating which nodes are currently active participants in the network; and is the continuous trigonometric time encoding that provides temporal context.

Based on this observation, the model generates an action defined as a binary vector . Mathematically, setting translates to a “Temporary Immunization” or “Filtering” operation: the selected node is functionally isolated from the diffusion process for the duration of the current time step , preventing it from sending or receiving information regardless of its infection status. Crucially, these actions are executed simultaneously across the selected subset of nodes before the state transition occurs. To ensure physical feasibility, the action space is restricted by a hard activity masking mechanism: the model is mathematically prohibited from selecting inactive nodes, ensuring resources are not wasted on dormant users. Additionally, the action is subject to a strict budget constraint, .

A critical innovation in our formulation lies in the reward function design. Standard objectives that solely penalize the cumulative infection count often lead to myopic, reactive policies. To induce proactive behavior, we propose a rate-penalized reward function that incorporates the velocity of the spread. Specifically, the reward is defined in Equation (2).

The inclusion of the derivative term during the event window serves as a strong gradient signal. Since the simulation operates in discrete time steps, the continuous derivative lacks a direct operational definition. Therefore, we operationalize this term using a first-order backward difference approximation. To maximize this reward, the model is mathematically compelled to intervene before the event window begins, effectively pruning the network’s “bridge nodes” to prevent the derivative from spiking when the event triggers.

2.3. The ST-DRL Neural Architecture

To solve the defined MDP, we propose the ST-DRL architecture, which decouples temporal perception from structural reasoning and subsequently fuses them into a unified decision policy.

Temporal encoding. Standard neural networks struggle to extrapolate patterns from raw scalar timestamps. To address this, we introduce a Continuous Trigonometric Time Encoding mechanism that projects the scalar time into a high-dimensional Hilbert space via a learnable Fourier feature mapping. This encoding, which is described in Equation (3), incorporates multiple frequency components to capture periodicities ranging from hourly fluctuations to daily cycles, and explicitly appends the event signal . This module effectively provides the agent with a “sense of time” using multilayer perceptron (MLP), enabling it to anticipate periodic wake-up cycles and the onset of scheduled events.

Structural embedding. In parallel, we utilize GAT to capture topological importance. Unlike static centrality metrics, GAT learns dynamic attention weights between neighbors based on their current states. This allows the model to differentiate between a “high-degree node that is Recovered” (low risk) and a “medium-degree node that is active and Infected” (high risk), generating a robust structural embedding .

Spatio-temporal fusion. The core mechanism for resolving the Spatio-Temporal Mismatch is the gated fusion layer. Simple concatenation of time and space features is insufficient; the model requires a mechanism to modulate structural importance based on temporal context. We achieve this by projecting the concatenated embeddings into a latent decision space and applying an activity-based mask. For each node , the final representation is computed in Equation (4).

where zeroes out currently inactive nodes. This fusion operation allows the network to learn conditional logic, such as enhancing the priority of “Workforce” nodes during the day while shifting focus to “Youth” nodes at night. Finally, the policy is optimized using proximal policy optimization [28] with generalized advantage Estimation, ensuring stable convergence in this high-variance stochastic environment.

To facilitate reproducibility and precise architectural reconstruction, we specify the implementation details as follows. The Continuous Trigonometric Time Encoding module utilizes frequency components to capture periodicities ranging from 6 to 24 h, processed by a two-layer MLP with 64 hidden units to generate the temporal embedding. Parallelly, the structural reasoning module employs a two-layer GAT with attention heads; to stabilize training within the deep graph network, we apply Layer Normalization (LayerNorm) followed by ELU activation after each graph convolution operation, projecting node features into a 64-dimensional embedding space. In the fusion stage, the concatenated spatio-temporal vector (128 dimensions) is compressed via a linear projection layer to match the hidden dimension () before being passed to the output head. The specific hyperparameters governing the optimization process and network dimensions are comprehensively listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Hyperparameter Configuration for ST-DRL.

3. Experiment

In this section, we detail the experimental protocols designed to rigorously evaluate the efficacy, interpretability, and robustness of the ST-DRL framework. Given the counterfactual nature of intervention tasks—where intervening in historical timelines to observe alternate outcomes is impossible—we employ a high-fidelity synthetic simulation environment grounded in empirical network science and social dynamics theories.

3.1. Synthetic Environment Construction

To faithfully reproduce the “Spatio-Temporal Mismatch” observed in real-world platforms, we model the social ecosystem with three coupled components: topology, demographic activity, and exogenous triggers.

Network Topology: We generate synthetic networks using the Holme–Kim power-law clustering algorithm with parameters , which jointly reproduce the scale-free degree distribution and small-world clustering coefficient characteristic of real-world online communities.

Demographic Dynamics (Data Generation): Nodes are stratified into four distinct demographic groups , comprising 30%, 40%, 20%, and 10% of the population, respectively. Their temporal availability is governed by Gaussian mixture models to simulate phase-shifted circadian rhythms: Bots which mean automated accounts: High baseline activity , low circadian variance , acting as persistent “kindling”. Workforce: Bimodal activity pattern (peaks at 08:00 and 19:00), high event sensitivity . Youth: Night-active (peak at 23:00), delayed phase shift . Elderly: Morning-active (peak at 07:00), low event sensitivity .

Non-Stationary Event Trigger: To simulate the bursty nature of misinformation, we introduce an exogenous “Breaking News” signal . This is modeled as a Gaussian pulse centered at 35 h. During this window, the base transmission rate surges non-linearly, by a factor of up to 3.0×, challenging the agent’s ability to handle extreme non-stationary dynamics.

3.2. Baseline Strategies

We benchmark ST-DRL against a tiered set of strategies representing different levels of information accessibility and temporal awareness:

- No Intervention: The control condition in which misinformation spreads according to the natural SIR dynamics without any mitigation.

- Static Heuristics (Static Degree/PageRank): Strategies that select intervention targets based on global structural centrality computed from a static graph snapshot. These baselines quantify the performance loss caused by spatio-temporal mismatch, as they disregard the time-varying activity states of nodes.

- Dynamic Degree: A strong baseline that selects the most connected nodes among those currently active at each time step. This represents the theoretical upper bound of “reactive” strategies, assuming perfect real-time knowledge of global activity.

- Ablation Variant (ST-DRL w/o Time): A model ablation in which the continuous trigonometric time encoding module is removed. This comparison isolates the contribution of temporal perception to the agent’s decision-making process.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

We establish a multi-dimensional metric system to evaluate effectiveness, mechanism, and robustness.

- Efficacy Metrics (Outcome):

- Cumulative Infection Load (AUC): The total area under the infection curve . Represents total social harm.

- Peak Prevalence Reduction (PPR): The percentage reduction in the maximum infection count compared to the “No Intervention” baseline. Measures the capacity to “flatten the curve”.

- Interpretability Metrics (Mechanism):

- Preemptive Efficiency (PE): In Equation (5), a novel metric quantifying the proactive nature of the policy. It is defined as the proportion of the budget allocated to “bridge nodes”, such as Bots, before the event peak .where denotes the set of intervened nodes at time . A high PE indicates that the agent has learned to perform “source pruning” in anticipation of the event.

- Effective Intervention Rate (EIR): The ratio of interventions applied to nodes that are actually active. Low EIR indicates “Spatio-Temporal Mismatch”.

- Robustness Metrics: Parameter Sensitivity: Evaluating performance stability across varying Base Infection Rates and Budget Constraints .

4. Results and Analysis

In this section, we conduct a multi-faceted empirical evaluation of the ST-DRL framework. We begin by quantifying its overall efficacy in suppressing misinformation compared to varied baselines. Subsequently, we open the “black box” of the neural network to decode its learned decision-making logic, providing rigorous evidence for the “Preemptive Defense” hypothesis. Finally, we assess the economic viability and robustness of the model across a spectrum of environmental constraints.

As summarized in Table 2, the proposed ST-DRL framework achieves a superior balance between suppression efficacy and resource efficiency. While the “Dynamic Degree” strategy—which serves as an ideal “Oracle” baseline assuming perfect real-time knowledge—achieves a marginally higher Peak Prevalence Reduction (94.5%), ST-DRL delivers a highly competitive performance of 93.2%. Crucially, it attains this without requiring the computationally prohibitive global monitoring inherent to the oracle, yielding a comparable Return on Investment (ROI) of 7.71. While ST-DRL and its ablation variant yield identical macroscopic AUC (116), the Preemptive Efficiency (PE) metric reveals a fundamental mechanistic divergence (0.38 vs. 0.01). Lacking temporal perception, the variant degenerates into a reactive policy. In contrast, ST-DRL leverages time encoding to strategically sanitize latent threats (such as Bots) prior to outbreaks. This confirms a paradigm shift from reactive suppression to proactive defense, offering superior robustness against real-world latency.

Table 2.

Comparative Evaluation of Mitigation Efficacy and Resource Efficiency Across Different Intervention Strategies. Note: Results are reported as mean “±” standard deviation over 20 independent runs.

4.1. Overall Efficacy: Approaching the Theoretical Limit

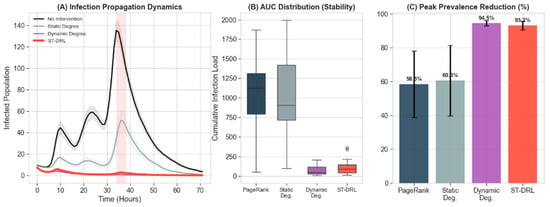

Figure 2A visualizes the temporal evolution of infection under different interventions. The “No Intervention” trajectory (black curve) reveals the inherent volatility of the ecosystem, characterized by a catastrophic surge during the event window where infection counts peak at about 140. The “Static Degree” baseline (gray curve), restricted by its reliance on time-invariant topology, fails to adapt to the sudden activity shift, resulting in a delayed and insufficient response. In sharp contrast, ST-DRL (red curve) effectively “flattens the curve”, maintaining the infection count near zero throughout the entire simulation horizon. Its trajectory closely mirrors that of the Oracle baseline, demonstrating that the agent has successfully learned to approximate the optimal reactive upper bound through end-to-end training.

Figure 2.

Spatiotemporal Efficacy and Statistical Stability of the ST-DRL Framework under Non-Stationary Dynamics. (A) Infection Propagation Dynamics: Temporal evolution of the infected population. The shaded regions represent the 95% confidence interval. The red vertical band indicates the “Breaking News” event window. Note that ST-DRL (red curve) suppresses the event-driven surge significantly earlier than static baselines. (B) AUC: Boxplots comparing the distribution of total social harm across stochastic episodes. ST-DRL exhibits a tight interquartile range, confirming its robustness against initialization noise. (C) Peak Prevalence Reduction: Bar chart quantifying the capacity to “flatten the curve.” ST-DRL achieves a reduction rate comparable to the oracle-assisted Dynamic Degree baseline, vastly outperforming static heuristics.

Furthermore, Figure 2B (Boxplot of AUC) and Figure 2C (Peak Reduction Bar Chart) provide statistical confirmation of the model’s stability. Across stochastic episodes, ST-DRL exhibits a tight interquartile range and a high mean reduction rate. This indicates that the learned policy is not merely overfitting to specific seeds but has generalized to the underlying dynamics, consistently preventing system collapse even under high-variance conditions.

4.2. Mechanism Interpretation: Decoding the Preemptive Strike

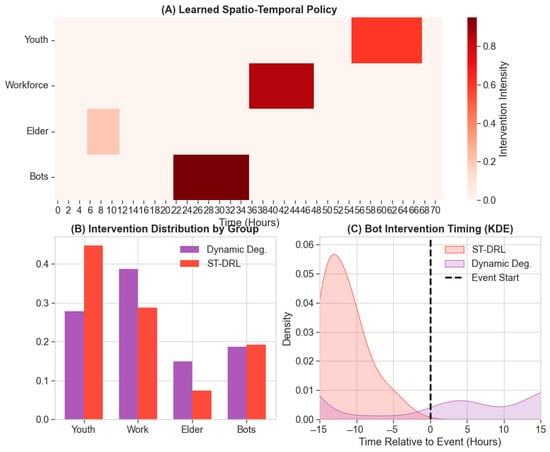

A critical contribution of this work is unboxing the decision-making logic. While the Oracle baseline (Dynamic Degree) achieves high suppression via reactive greedy selection, ST-DRL operates through a fundamentally different mechanism. This divergence is quantified by the Preemptive Efficiency (PE) metric in Table 1. ST-DRL yields a PE of 0.38, whereas the Oracle baseline is negligible (0.01). This indicates that ST-DRL allocates nearly 40% of its pre-event budget to high-risk bridge nodes (specifically Bots). Figure 3 provides visual evidence for this strategy:

Figure 3.

Unveiling the learned “Preemptive Strike” mechanism. (A) Spatio-temporal policy heatmap revealing a strategic focus on high-risk Bots (bottom row) during the pre-event window, followed by an adaptive shift to Workforce hubs. (B) Intervention distribution by group, highlighting ST-DRL’s disproportionate investment in bridge nodes compared to the uniform reaction of baselines. (C) Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) of intervention timing relative to event onset. The ST-DRL distribution (red) exhibits significant anticipatory mass in the negative time domain, validating the transition from reactive to proactive defense.

- Pre-Event Phase : As shown in Figure 3A,B, ST-DRL concentrates high-intensity intervention on Bots (dark red block in the bottom row). This is counter-intuitive from a static centrality perspective, as Bots often have lower degrees than Workforce hubs. However, the agent identifies them as the “kindling” for the impending event.

- Event Phase : As the event unfolds, the focus adaptively shifts to Workforce (middle row) and eventually Youth (top row). This transition proves that the Time Encoder successfully imparts a sense of “phase”, allowing the agent to switch targets dynamically as the risk landscape evolves.

- Statistical Evidence of Preemption (Figure 3C): The Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) plot of intervention timing offers the most compelling evidence for our hypothesis. The distribution of ST-DRL interventions (red area) shows significant probability mass in the negative time domain (, relative to event onset). This indicates that the agent is acting anticipatorily. In contrast, the Dynamic Degree baseline (purple area) reacts almost exclusively in the positive domain (), lagging behind the diffusion curve. This temporal lead—the “Preemptive Gap”—is the key mechanism that allows ST-DRL to dismantle the propagation backbone before the transmission rate surges non-linearly.

To verify that the “Preemptive Strike” is a robust policy feature rather than a stochastic artifact of specific initialization seeds, we analyzed the distribution of intervention actions across 20 independent episodes. Despite aleatoric variations in individual node activity , the agent exhibits a highly converged preference for high-risk demographics, allocating an average of actions to the Bot group per episode. Crucially, the variance in strategic timing is minimal; the proportion of interventions targeting Bots during the critical pre-event window remains extremely stable at . This low coefficient of variation confirms that the agent has learned a deterministic invariant: prioritizing the sanitization of the Bot category is the optimal strategy for minimizing future regret, ensuring that the preemptive effect is consistently maintained regardless of environmental noise.

4.3. Efficiency and Robustness Landscape

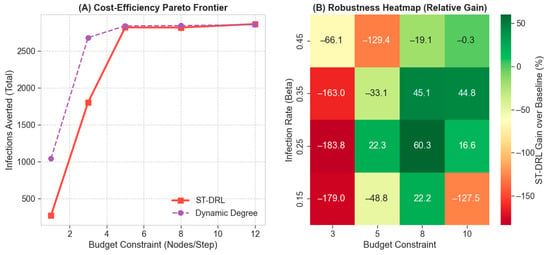

As show in Figure 4B, the Robustness Heatmap analyzes the relative performance gain of ST-DRL over the strong Dynamic Degree baseline across varying Infection Rates () and Budgets. High-Complexity Regimes: We observe distinct positive gains (green zones) in scenarios characterized by moderate-to-high infection rates (e.g., ). In these volatile environments, the complexity of diffusion dynamics exceeds the capacity of simple greedy heuristics, and the long-term planning capability of RL becomes the deciding factor [29].

Figure 4.

Economic efficiency and robustness landscape under varying constraints. (A) Pareto Frontier of infections averted versus budget. ST-DRL (red) demonstrates superior marginal utility, particularly in critical low-budget regimes. (B) Robustness heatmap displaying the relative performance gain over the strong greedy baseline. Positive gains (green zones) are maximized in high-complexity scenarios, confirming the value of long-term planning under stress.

In specific low-complexity regimes, for example, low , and low budget, the greedy baseline performs slightly better (red zones). This is expected, as greedy strategies are often optimal for simple, short-horizon tasks. However, the robust performance of ST-DRL across the majority of the parameter space, combined with its unique preemptive capability, makes it a more reliable candidate for real-world applications where “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” [30].

5. Conclusions and Future Work

5.1. Conclusions

In this work, we identified and addressed the “Spatio-Temporal Mismatch” in misinformation intervention, demonstrating that traditional static heuristics fail to contain non-stationary outbreaks driven by circadian rhythms and exogenous triggers. To resolve this, we proposed the Spatio-Temporal Deep Reinforcement Learning framework, which fuses continuous trigonometric time encoding with demographic-aware structural reasoning.

Our rigorous empirical evaluation yields three critical insights:

- Efficacy: Under the specific constraints and assumptions of our simulation environment, ST-DRL effectively “flattens the curve”, achieving a Peak Prevalence Reduction of 93.2%. It significantly outperforms static baselines and operates on par with “oracle-assisted” dynamic heuristics, proving that end-to-end learning can approximate theoretical upper bounds without requiring prohibitive real-time global monitoring.

- Mechanism: Interpretability analysis confirms that the agent autonomously evolves a “Preemptive Strike” strategy. Driven by velocity-suppressing rewards, the agent learns to sanitize high-risk bridge nodes, such as bots, prior to event triggers , validating that temporal perception is the cornerstone of proactive defense.

- Efficiency: The framework demonstrates exceptional economic viability, achieving the highest Return on Investment in resource-constrained scenarios. This establishes ST-DRL as a robust solution for real-world platforms where “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”.

Collectively, this work establishes a new theoretical paradigm for network governance: shifting from reactive suppression—which often lags behind the diffusion curve—to predictive and proactive defense. However, translating these simulation-based findings to real-world deployment warrants cautious optimism. Practical application faces the “Sim-to-Real” gap, encompassing challenges such as noisy demographic data, adversarial adaptation by misinformation actors, and the computational scalability required for billion-scale graphs. Furthermore, the deployment of “preemptive” algorithmic interventions necessitates rigorous ethical governance; such mechanisms must be coupled with transparency protocols and human-in-the-loop oversight to mitigate the risks of over-blocking and safeguard the integrity of legitimate public discourse.

5.2. Future Work

Future work will focus on three AI-centric challenges. First, scaling ST-DRL to billion-node graphs demands efficient architectures—such as decentralized MARL or subgraph sampling—that preserve spatio-temporal reasoning while reducing computation, building on recent advances in scalable graph representation learning [31]. Second, to enable sim-to-real transfer, we will integrate domain-invariant representation learning to handle noisy node attributes and partial observability in real-world social graphs [32]. Finally, we aim to formalize the interaction between the defender and adaptive misinformation sources as a partially observable stochastic game, where adversaries dynamically alter activity patterns to evade intervention—opening a path toward robust, game-theoretic defense in non-stationary environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.Y. and Z.Z.; Methodology, F.Y. and Z.Z.; Writing—original draft, Z.Z. and Z.Y.; Writing—review and editing, Y.W.; Validation, Z.Z. and C.W.; Visualization, C.W. and J.C.; Formal analysis, C.W.; Data Curation, J.C.; Supervision, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62372418); University Students’ Science and Technology Association Support Program Project (ZG25004, China Association for Science and Technology); the State Key Laboratory of Media Convergence and Communication, Communication University of China; the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (CUCZD2503); Liaoning Collaboration Innovation Center For CSLE; and The High-quality and Cutting-edge Disciplines Construction Project for Universities in Beijing (Internet Information, Communication University of China).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. The code is available at: https://github.com/zhangzhiqiangccm/ST-DRL (accessed on 29 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cinelli, M.; Gesualdo, F. Infodemic Versus Viral Information Spread: Key Differences and Open Challenges. JMIR Infodemiol. 2025, 5, e57455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petratos, P.N. Misinformation, disinformation, and fake news: Cyber risks to business. Bus. Horiz. 2021, 64, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, J.R.; Zhang, Y.; Gwizdka, J. Healthcare professionals’ acts of correcting health misinformation on social media. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2021, 148, 104375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, S.; Tenove, C. Disinformation as a threat to deliberative democracy. Political Res. Q. 2021, 74, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Guo, L.; Zhong, Y. Efficient algorithms for maximizing group influence in social networks. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2022, 27, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempe, D.; Kleinberg, J.; Tardos, É. Maximizing the spread of influence through a social network. In Proceedings of the KDD03: The Ninth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Washington, DC, USA, 24–27 August 2003; pp. 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Jaouadi, M.; Romdhane, L.B. A survey on influence maximization models. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 248, 123429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plepi, J.; Sakketou, F.; Geiss, H.-J.; Flek, L. Temporal graph analysis of misinformation spreaders in social media. In Proceedings of the TextGraphs-16: Graph-Based Methods for Natural Language Processing, Gyeongju, Republic of Korea, 16 October 2022; pp. 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, C.; Ciampaglia, G.L.; Varol, O.; Yang, K.-C.; Flammini, A.; Menczer, F. The spread of low-credibility content by social bots. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.C.; Dahlke, R.; Hancock, J.T. Exposure to untrustworthy websites in the 2020 US election. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 1096–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.; Tump, A.N.; Ehmann, N.; Lorenz-Spreen, P.; Hertwig, R.; Gollwitzer, A.; Kurvers, R.H.J.M. Susceptibility to online misinformation: A systematic meta-analysis of demographic and psychological factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2409329121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchanda, S.; Mittal, A.; Dhawan, A.; Medya, S.; Ranu, S.; Singh, A. Gcomb: Learning budget-constrained combinatorial algorithms over billion-sized graphs. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 20000–20011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Qiu, W.; Ou, H.C.; An, B.; Tambe, M. Contingency-aware influence maximization: A reinforcement learning approach. In Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1535–1545. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q. Influence maximization for heterogeneous networks based on self-supervised clustered heterogeneous graph transformer. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 154, 110595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Song, Y.; Yang, W.; Yuan, K.; Li, Y.; Kong, M.; Fathollahi-Fard, A.M. Budget-aware local influence iterative algorithm for efficient influence maximization in social networks. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.; Tang, Q.; Ding, H. TGAT: Temporal graph attention network for blockchain phishing scams detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Computer, Information and Telecommunication Systems (CITS), Girona, Spain, 17–19 July 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, A.; Mesquita, D.; Kaski, S.; Garg, V. Provably expressive temporal graph networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 32257–32269. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, D.; Kim, E.; Cho, Y.-S. Topological and sequential neural network model for detecting fake news. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 143925–143935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-T.; Hu, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Jiang, J.; Sun, N. Dihan: A novel dynamic hierarchical graph attention network for fake news detection. In Proceedings of the CIKM ’24: The 33rd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Boise, ID, USA, 21–25 October 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Lin, X.; Xu, L.; Sun, Y. Bi-directional temporal graph attention networks for rumor detection in online social networks. Computing 2025, 107, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, L.; Peng, Z. Proactive Rumor Control Using Graph Neural Networks and Evolutionary Optimization. Data Sci. Eng. 2025, 10, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, H.; Gao, Y.; Guo, J.; Wu, W. A survey on influence maximization: From an ml-based combinatorial optimization. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2023, 17, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Yan, S.; Guo, J.; Wu, W. ToupleGDD: A fine-designed solution of influence maximization by deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2023, 11, 2210–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Constantinides, M.; Quercia, D.; Šćepanović, S. How circadian rhythms extracted from social media relate to physical activity and sleep. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Limassol, Cyprus, 5–8 June 2023; pp. 948–959. [Google Scholar]

- Vosoughi, S.; Roy, D.; Aral, S. The spread of true and false news online. Science 2018, 359, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, W.J.; Zong, L.; Wang, T.; Yang, D. Influence maximization with limit cost in social network. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2013, 56, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrara, N.; Leurent, E.; Laroche, R.; Urvoy, T.; Maillard, O.-A.; Pietquin, O. Budgeted reinforcement learning in continuous state space. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.G.; Kim, D.H. Autonomous flying of drone based on PPO reinforcement learning algorithm. J. Inst. Control. Robot. Syst. 2020, 26, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, K.; Zhou, J.; Tsianikas, S.; Coit, D.W.; Ma, Y. Long-term microgrid expansion planning with resilience and environmental benefits using deep reinforcement learning. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 191, 114068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoagland, A. An ounce of prevention or a pound of cure? The value of health risk information. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2025, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, X.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y. Scalable and effective temporal graph representation learning with hyperbolic geometry. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 36, 6080–6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, R.; Guo, D.; Qi, D.; Chu, Z.; Yu, X.; Li, S. A survey of trustworthy representation learning across domains. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2024, 18, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.