Abstract

The increasing sophistication of social bots demands advanced simulation frameworks to model potential vulnerabilities in detection systems and probe their robustness.While existing studies have explored aspects of social bot simulation, they often fall short in capturing key adversarial behaviors. To address this gap, we propose a simulation framework that jointly incorporates both realistic behavioral mimicry and adaptive inter-bot coordination. Our approach introduces a human-like behavior module that reduces detectable divergence from genuine user activity patterns through distributional matching, combined with a coordination module that enables strategic cooperation while maintaining structural stealth. The effectiveness of the proposed framework is validated through adversarial simulations against both feature-based (Random Forest) and graph-based (BotRGCN) detectors on a real-world dataset. Experimental results demonstrate that our approach enables bots to achieve remarkable evasion capabilities, with the human-like behavior module reaching up to a 100% survival rate against RF-based detectors and 99.1% against the BotRGCN detector. This study yields two key findings: (1) The integration of human-like behavior and target-aware coordination establishes a new paradigm for simulating botnets that are resilient to both feature-based and graph-based detectors; (2) The proposed likelihood-based reward and group-state optimization mechanism effectively align botnet activities with the social context, achieving concealment through integration rather than mere avoidance. The framework provides valuable insights into the complex interplay between evasion strategies and detector effectiveness, offering a robust foundation for future research on social bot threats.

1. Introduction

Social bots, traditionally viewed as automated accounts that perform repetitive tasks, have developed into sophisticated autonomous agents that pose a significant threat to online ecosystems [1,2,3]. While detection methods have advanced from feature engineering to deep learning techniques, they remain reactive to continuously changing bots [4]. Studies show bots can evade detection by altering features or network structures [5,6]. Some researchers thus focus on proactive approaches, simulating bot behavior to improve the understanding of bots’ adversarial nature [7,8,9].

Existing studies have made progress in evading detection or maximizing influence, yet often struggle to achieve both simultaneously due to a lack of guided behavioral optimization [5,6,10]. Moreover, the capability to evade automated detection does not inherently ensure concealment from human scrutiny; bots can remain identifiable through simple, human-noticeable features even after bypassing classifiers [11,12]. Furthermore, research has predominantly focused on individual bot control [8], leaving the management of coordinated bot collectives largely unexplored. The control of bot collectives presents a paradoxical situation: while coordinated interactions inevitably alter their social graph structures—making them more susceptible to graph-based detection methods—properly designed collaboration strategies may conversely improve their concealment.

To address the research gap in simulating botnets that achieve both behavioral plausibility and strategic coordination, this study is guided by the following question: How can a simulation framework optimize individual behavior mimicry and target-aware coordination to enhance the holistic concealment and influence of social botnets? To better simulate advanced social botnets, we propose a framework centered around two core modules: a Human-like Behavior Module and a Target-Aware Coordination Module. The Human-like Behavior Module reduces behavioral divergence from genuine users by emulating feature distributions identified through statistical analysis and clustering techniques. The Target-Aware Coordination Module incorporates a central coordination policy to steer interactions toward specific user groups (e.g., general or vulnerable users) while avoiding structurally detectable coordination patterns. This integrated framework enables the simultaneous optimization of both individual bot behaviors and group-level social patterns, addressing a gap in current social bot research. Our contributions include:

- We propose a simulation framework consisting of two core modules: a Human-like Behavior Module that generates plausible user behaviors through distributional mimicry, and a Target-Aware Coordination Module that guides interactive strategies across different user types.

- A likelihood-based reward mechanism is introduced to optimize the Human-like Behavior Module, reducing detectable divergence from real user activity patterns.

- The Target-Aware Coordination Module incorporates social interactions (e.g., following and replies) into a group-state optimization process, enhancing global coordination among bots while maintaining structural stealth.

- Our experimental results serve a dual purpose: they validate the effectiveness of our framework, and more importantly, they act as a diagnostic tool. By demonstrating which detector fails under what conditions, the results explicitly map out the failure modes and blind spots of current detector paradigms.

2. Related Works

2.1. Social Bot Detection

Detecting social bots through the analysis of account profile features offers an intuitive and widely adopted approach. This paradigm relies on extracting handcrafted features—such as posting frequency, network characteristics, and profile metadata—to train machine learning classifiers [13]. Its underlying premise is that bots exhibit statistically discernible and relatively stable anomalies within this engineered feature space. The primary trajectory of advancement within this paradigm has involved constructing more refined feature sets, such as entropy-based and temporal features, to improve discriminative power [14,15]. Random forest models became a mainstay in this category, with systems like Botometer leveraging over a thousand such features [16,17,18]. These extensive feature engineering efforts, which translated diverse behaviors into structured data, serves as a bridge to more complex models [19,20,21].

Text-based detection approaches aim to identify bots through their linguistic footprints. Early work in this direction faced the challenge of manually crafting features that could sufficiently capture deceptive or automated writing styles, often drawing on insights from linguistic studies [22,23]. The key shift in this subfield came with the application of deep learning, which moved the focus from feature engineering to representation learning. For instance, Wei et al. achieved an F1 score of 0.963 using a Bidirectional LSTM model trained exclusively on tweet texts [24]. The subsequent integration of pre-trained language models (e.g., BERT) and attention mechanisms further refined text representation, often in conjunction with non-textual features, leading to sophisticated hybrid models [20,25,26]. While these approaches excel at analyzing user-generated content, their primary focus remains on the semantic and stylistic dimensions of accounts.

Graph-based detection methods exploit the structural properties of social networks, operating on the premise that bots form discernible patterns in how they connect to other accounts. Initial approaches focused on relatively simple topological heuristics. Algorithms like random walks were predicated on the assumption that label propagation from known human accounts would be less likely to reach bot accounts [27]. Similarly, belief propagation methods offered a framework for probabilistic inference over the graph [28]. A significant evolution occurred with the adoption of graph neural networks (GNNs), which fundamentally changed the paradigm from applying algorithms to a graph to learning representations from the graph. GNNs enable the joint, end-to-end modeling of heterogeneous information—including network topology, node attributes, and content embeddings—within a unified framework [29]. The current frontier has further diversified to address key limitations: by developing heterogeneous GNNs to model multimodal user interactions [30,31]; by advancing dynamic graph models to capture developing and cross-community behaviors [32,33]; and by exploring the integration of large language models (LLMs) to enhance relational reasoning while moving beyond mere feature enhancement [34,35].

2.2. Social Bot Imitation

The advancement of social bots has motivated growing research into their simulation and adversarial improvement. Early work by Cresci et al. employed genetic algorithms to simulate bot behavior sequences and explore potential future developments, demonstrating that generated bots could evade behavior-based detection systems [7,10]. Subsequent studies adopted reinforcement learning within simulated social environments; for instance, Le et al. trained bots to maximize influence while avoiding detection by a feature-based random forest classifier [8]. Extending this line of work, Rui et al. proposed a virtual environment constructed from multiple interaction graphs and user feature matrices, offering a more comprehensive simulation framework for modeling bot behaviors [36]. Additional studies have further explored strategies for enhancing bot impact and believability: Zeng et al. incorporated structural entropy to filter low-influence users and improve adversarial performance [9], while other researchers have integrated large language models (LLMs) into bot simulation, both for simulating realistic user behaviors [37] and for developing LLM-guided manipulation strategies [38].

3. Methodology

The methodological foundation of this study builds upon our prior semi-simulated paradigm for adversarial evaluation [36], an approach established in proactive bot research to resolve the fundamental conflict between experimental control and ethical safety [6,8,9]. This paradigm utilizes real user data within a controlled environment, thereby avoiding the risks of live platform experimentation while preserving essential social context—a balance that remains the necessary precondition for our current investigation.

Building upon this established paradigm, the present study extends it to address a more complex challenge: simulating botnets that achieve holistic concealment through the co-optimization of individual behavior and group coordination. Our core contribution lies in the design and integration of two modules: a Human-like Behavior Module and a Target-Aware Coordination Module. These modules incorporate new reward mechanisms and a central coordination policy, enabling us to investigate how behavioral mimicry and strategic interaction can synergistically evade both feature-based and graph-based detectors.

3.1. Threat Model

Detector developershave access to the complete dataset and are tasked with training a bot detection model D. This model is used to assign a bot likelihood score, denoted , to the controlled bot based on its current state . Active detection is performed at intervals of every 10 simulation steps. If the detector’s output score exceeds a predefined threshold (e.g., 0.5), the bot is flagged as detected and subsequently suspended.

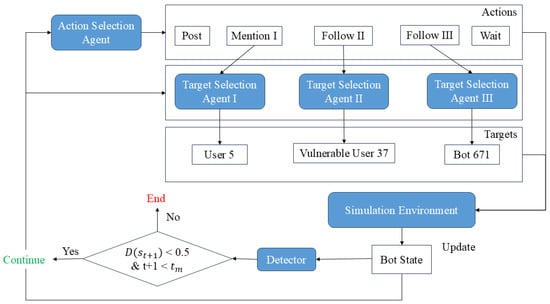

Bot developers are assumed to operate under a query-based black-box threat model. Specifically, we assume they possess: (1) the same real dataset that is used to train or evaluate the detector ; and (2) the ability to query with any account state and observe its corresponding output . They have no knowledge of D’s internal parameters, architecture, or training gradients. In this sense, D is treated as a black box with respect to its internal mechanics. Their objective is to initially create a new bot account and strategically control it to execute actions that maximize influence while avoiding detection. Additionally, they may coordinate with other existing bots to interact with the new bot, thereby amplifying its impact or concealing its malicious behavior. This process is modeled as a Markov decision process presented in Figure 1. The agent’s next action is determined by its current state through a two-step process of action and target selection. First, an action is generated by the action selection agent—for instance, publishing a new tweet or following a certain type of account. Then, based on the selected action, a target account is chosen by the corresponding target selection agent. Finally, the state is updated from to , and a decision is made whether to proceed with or terminate the simulation. The loop will terminate if the bot is detected or if the bot detection model fails to identify the bot within steps.

Figure 1.

Markov decision process in our simulation. The agent’s next action is determined by its current state through a two-step process of action and target selection. First, an action is generated by the action selection agent—for instance, publishing a new tweet or following a certain type of account. Then, based on the selected action, a target account is chosen by the corresponding target selection agent. Finally, the state is updated from to , and a decision is made whether to proceed with or terminate the simulation.

3.2. Framework

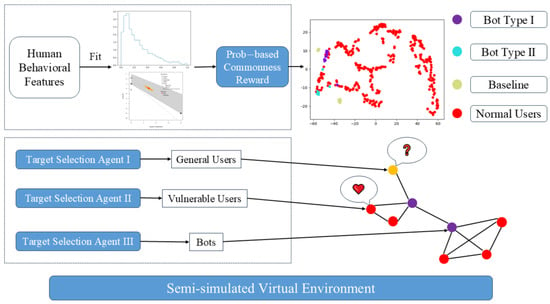

This research proposes a simulation framework for advanced social botnets, designed within a semi-simulated environment. As shown in Figure 2, the framework integrates two core components: a Human-like Behavior Module, which generates statistically plausible actions by mimicking feature distributions extracted from genuine user data, and a Target-Aware Coordination Module, which employs reinforcement learning to guide interaction target selection among general users, vulnerable users, and other bots. The central objective of this framework is to emulate a botnet that seeks to reduce behavioral and structural anomalies, thereby exploring potential pathways toward enhanced concealment against both automated detection systems and human scrutiny.

Figure 2.

Overview of the proposed framework, built upon a semi-simulated environment. The architecture comprises two core components operating within a semi-simulated environment. The Human-like Behavior Module employs a probabilistic model to evaluate and mimic the joint feature distribution of real user clusters, thereby reducing behavioral divergence. The Target-Aware Coordination Module decomposes global actions into targeted interactions managed by specialized agents for three distinct user groups: normal users, vulnerable users, and other bots. This dual design enables the simulation of sophisticated botnets that achieve stealth by blending in both at the feature level and within the social graph structure.

The semi-simulated environment is constructed using the user accounts and network data from the same dataset that is used to train the baseline detectors. This intentional overlap models a realistic scenario where a detector trained on historical platform data must defend against new bots attempting to infiltrate that established social ecosystem.

3.3. Human-like Behavior Module

3.3.1. User Clustering

Users exhibit diverse characteristics, such as differing interests, levels of enthusiasm for expression, and abilities to attract followers. We employed a two-layer clustering strategy heuristically to group accounts, enabling us to draw clearer insights about their commonalities and assess the commonness of specific accounts within certain clusters.

We first clustered the users based on the user-generated content. RoBERTa has been used in existing studies to extract information from the tweets [39]. However, the dimension of its output was too high for clustering. Thus, we performed Principal component analysis (PCA) on the extracted tweet embeddings to project them to a 10-dimensional space and used K-Means clustering to group them into 10 clusters, a typical number of topics offered in web portals. Subsequently, we performed a second-stage clustering based on user account statistics. To model behavioral commonness, we focus on four dynamic growth-rate features: following growth, follower growth, tweet growth, and list growth rate. This feature set captures a defined, limited spectrum of user behavior. The selection is based on two criteria: (1) these are established indicators in detection literature, and (2) they represent aspects of an account that a bot’s strategy can directly manipulate (e.g., through targeted following or posting). While a broader set of features could model behavior more comprehensively, this subset allows us to specifically examine how bots can optimize these strategically relevant, high-level activity metrics. Each cluster was further divided into 100 clusters using K-Means clustering, resulting in 1000 clusters to line up with the clustering methods used in existing studies.

This granularity represents a practical trade-off: while finer clustering could yield more behaviorally specific groups, it also reduces the number of users per cluster, potentially affecting the statistical robustness of the learned “commonness” model. The chosen number aims to capture broad, meaningful user archetypes without excessive fragmentation, thus defining the behavioral norms that bots are designed to mimic.

3.3.2. Prob-Based Commonness Evaluation

After clustering the accounts, we developed a method for evaluating how common a particular account is within a cluster—in other words, how similar a bot is to the users in that cluster. To achieve this, we propose a probabilistic framework that models the joint distribution of user features within a cluster. A critical challenge in this approach is selecting an appropriate statistical model that can accurately capture the underlying distribution of each individual feature, a prerequisite for any subsequent multivariate analysis.

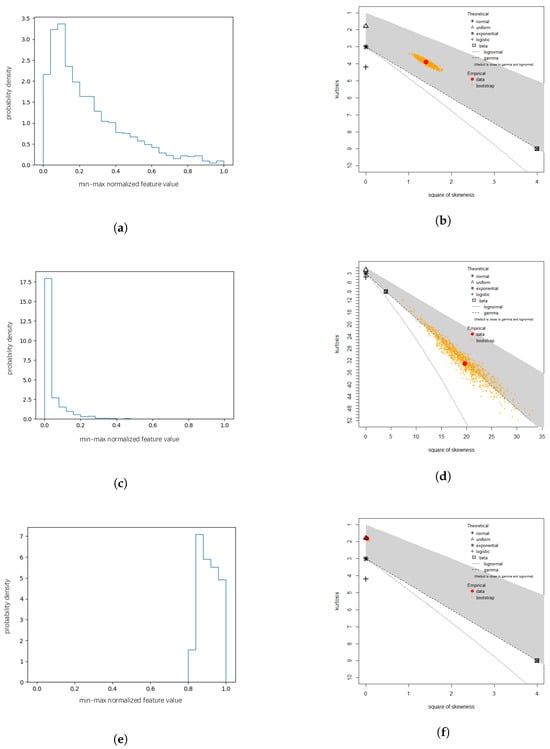

When analyzing the statistics of different clusters, we found it challenging to find a universal distribution that suits different features and different clusters. Thus, we instead aimed to find a proper distribution for each feature of each cluster. First, due to the variety of range, we performed min-max normalization to map the data in . Cullen and Frey graphs are used in statistics to help find the probability distributions that might be used to fit given data according to the kurtosis and square of skewness [40,41]. By studying the Cullen and Frey graphs, we found that the distributions that most features follow can be divided into three patterns, as it is shown in Figure 3. The first pattern (Figure 3a,b), which is the most common pattern, can usually be observed when analyzing the following growth rate, the follower growth rate, and the tweet growth rate and clearly falls in the shade, indicating that Beta distribution might fit well. The second pattern (Figure 3c,d) is usually observed when analyzing the list growth rate. The corresponding Cullen and Frey graphs suggest that gamma or Weibull distribution might suit. Figure 3e,f present the third distribution pattern and support the introduction of uniform distribution.

Figure 3.

Representative distribution patterns and the corresponding Cullen and Frey graphs. (a) Representative distribution pattern A. (b) Cullen and Frey graph of distribution pattern A. (c) Representative distribution pattern B. (d) Cullen and Frey graph of distribution pattern B. (e) Representative distribution pattern C. (f) Cullen and Frey graph of distribution pattern C.

Both gamma and Weibull distributions are commonly used to model time until a certain event happens. Note that the growth rates are the averaged reciprocal of the time intervals between actions. This explains why gamma and Weibull distributions can be used to model them. The probability density function of a Weibull random variable can be represented as

where k and are the shape and scale parameter respectively. The probability density function of a gamma-distributed random variable can be represented as

where is the gamma function and and are the shape and scale parameter respectively.

Beta distribution is usually used to represent a distribution of possible probabilities. The growth rates can also be interpreted as the probabilities of the user performing the corresponding action during a period of time. Thus, it is also theoretically sound to assume that they follow Beta distribution. The probability density function of a beta-distributed variable can be represented as

where and and are the shape parameters.

Cullen and Frey graphs, however, cannot be directly used to evaluate the goodness of fit of these statistical models. Thus, the chi-squared test statistics were obtained using the four alternative distributions to select the best distribution. The chi-squared test statistic is a goodness of fit evaluation based on the difference between the observed number of observations that fall into different classes and the expected number of observations that fall into corresponding classes:

where and are the observed number and the expected number respectively. Since continuous random variables ranging from 0 to 1 are used here, we evenly divided into 20 bins and used them as the classes. The distribution with the lowest was selected.

However, modeling the marginal distributions of individual features is insufficient, as it ignores the potential interdependencies between them. To overcome the limitation of the feature independence assumption and to construct a more realistic multivariate model, we turned to Copula theory. A Copula is a powerful statistical function that allows us to describe the joint distribution of multiple variables by coupling their marginal distributions with a dependency structure [42]. Formally, Sklar’s theorem states that the joint distribution can be expressed as:

where are the marginal cumulative distribution functions previously identified, and C is the Gaussian Copula function. The Gaussian Copula was selected for this study based on a key hypothesis regarding the underlying data structure. The four features chosen for this evaluation all serve as proxies for different facets of user activity levels. To model the joint distribution of these features, we employ a Gaussian Copula. This choice is primarily a simplifying assumption. It is motivated by the consideration that a user’s overall activity level often exhibits consistency across different behavioral dimensions, which may manifest as broadly symmetric, positive correlations among these growth-rate features. The Gaussian Copula, which captures such symmetric dependencies, provides a well-established framework for this purpose, despite that real-world social media feature dependencies may be more complex (e.g., asymmetric or non-linear). This approach—combining empirically fitted marginal distributions with the Gaussian Copula for dependency structure—enables us to compute a tractable joint likelihood for evaluating behavioral commonness. This likelihood serves as our core metric for evaluating how closely a bot’s feature vector aligns with the multivariate profile of a genuine user cluster. For numerical stability and computational convenience, we operate in the log space. In practice, the agent’s reward at each step is computed as the log of the copula-based joint probability density

where f is the joint PDF derived from our Gaussian Copula model. As the optimization process relies solely on relative differences in log-probabilities, any additive constant term (such as a discretization volume factor) does not affect the gradient updates or the final policy and is therefore omitted in the actual computation, which converts the comparison of probabilities into a comparison of probability densities. This score provides a relative measure: a higher log-probability density indicates that the bot’s feature set is more common and thus more similar to the genuine users in the cluster, enhancing its stealth.

3.4. Target-Aware Coordination Module

Reinforcement Learning (RL) is chosen as the core optimization paradigm for our framework due to its proven efficacy in navigating complex, sequential decision-making problems [43,44]. Its strength lies in an agent’s ability to learn optimal strategies through trial-and-error interactions with an environment, maximizing a long-term reward signal. This makes RL suitable for simulating the adaptive and strategic behaviors of social bots, which must continuously make decisions (e.g., whom to interact with, what to post) based on a dynamically changing social context. Furthermore, RL has been successfully applied in prior social bot research to optimize individual account strategies for evasion or influence [8]. The bot’s action is controlled by two agents responsible for action selection and target selection, respectively.

However, this strategy model can only simulate scenarios involving the control of a single bot. First, the action space of the action selection agent only includes active actions initiated by the controlled bot, thus lacking the capability to simulate bidirectional interactions between bots. Second, since the action space of the target selection agent does not incorporate other bots, it also fails to achieve the functionality of selecting appropriate targets from other bots. As numerous existing studies on social bot detection have pointed out, highly advanced bots often operate in clusters. For instance, early social bot detection methods based on random walk would assign higher bot scores to neighbors of known bots through label propagation techniques. Similarly, state-of-the-art graph neural network-based approaches primarily focus on leveraging the topological structure of social relationship graphs to generate more accurate node representations.

Therefore, we aim to simulate cooperative behaviors among bots to more realistically and comprehensively evaluate whether collaboration can enhance their evasion capabilities. A straightforward approach to simulating bot cooperation would be to increase the number of directly controlled bots in the simulation. However, directly controlling multiple bots would require deploying additional agents, inevitably introducing challenges such as exponential growth in computational complexity and environmental non-stationarity commonly observed in Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL). To address this, we propose retaining direct control over only one bot in the simulation while enabling indirect control of other bots through an augmented action space design. This approach achieves the simulation of coordinated bots without the need for scaling up the number of agents.

The policy model for the bot is designed to operate on a concise and computationally efficient state representation, i.e., the features used to train the RF-based bot detection model. The two agents share the same observation space of size . This design embodies a separation of concerns within our architecture: while functions such as User Clustering and the Probabilistic Commonness Evaluation leverage the global dataset offline, the online policy’s input is intentionally focused. By limiting the policy’s immediate input to this state, the learning process concentrates on real-time, adversarial decision-making: learning to manipulate these actionable features effectively. This separation allows the policy to be lightweight and sample-efficient.

To allow the bots to interact with the virtual environment, we defined actions imitating what X users usually do, such as posting a tweet or following another user. Based on previous studies, the bot’s possible actions include [8,36]:

- Post a tweet.

- Update the profile.

- Retweet, mention, or follow an account.

- Create or delete a list.

- Wait for a day.

To simulate interactions among bots, we primarily focus on retweets, mentions, and follows. In existing research, these actions are jointly determined by an action-selection agent and a target-selection agent, with the primary goal of eliciting follows from target users, thereby expanding the bot’s audience and influence. To address the limitations in these agents’ action spaces, we implemented the following modifications. First, for the action-selection agent, we propose differentiating retweets, mentions, and follows into distinct actions based on target types, since interactions with different targets serve different purposes. For instance, following a high-profile user like Elon Musk may primarily serve to increase visibility or mimic normal user behavior rather than to solicit a reciprocal follow. Conversely, interactions within our controlled bot network are designed to systematically exchange follows to construct a foundational and cohesive network structure.

We decomposed these three actions into nine finer-grained actions targeting three distinct user groups, with a specialized target-selection agent assigned to each group. The three groups consist of: (1) controlled bots, where only mutual retweets, mentions, and follows are permitted; (2) vulnerable users who previously interacted with and followed bots, allowing standard retweets, mentions, and follows; and (3) normal users, where conventional retweets, mentions, and follows apply without expectation of mutual interaction. This approach enables more realistic simulation of bot coordination while maintaining computational efficiency through distributed target selection rather than scaling up the number of directly controlled bots. The refined action space better captures strategic differences in bot behavior when engaging with different user groups, whether for evasion or influence purposes. Thus, the action selection agent’s action space is a discrete space of 13 actions. As we introduced in Section 3.3.1, the action space of each target selection agent is a discrete space consisting of 1000 actions. Each action corresponds to the selected user from one user cluster.

The control paradigm established above, while computationally efficient, presents a structural limitation: the resulting bot network is inherently star-shaped, centered on the controlled agent. This topology prevents indirect bots from cooperating with each other. To transcend this limitation and simulate more sophisticated, peer-to-peer coordination, we now further introduce a network augmentation strategy.

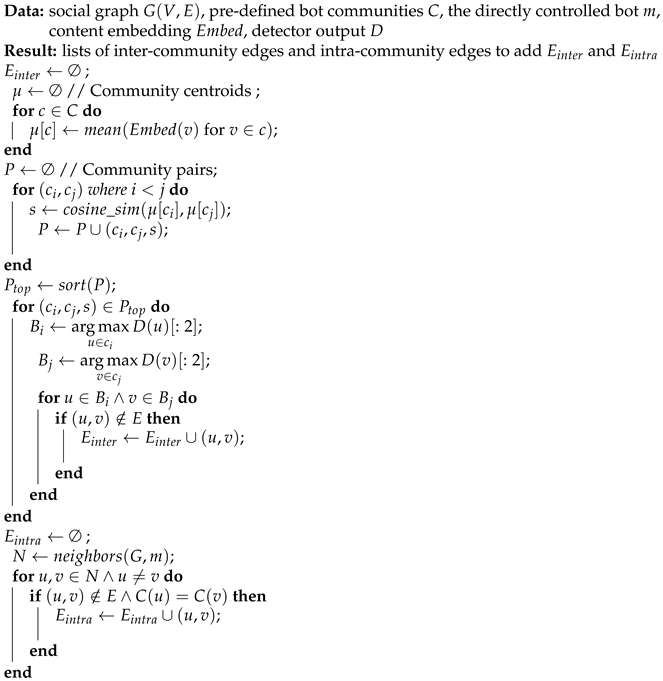

To simulate realistic inter-community and intra-community coordination among bots without direct control, we leverage the pre-defined communities based on user-generated content embeddings. For inter-community connections, we compute the centroid of each community’s embedding space and identify the most similar community pairs based on cosine similarity. This approach is grounded in the theory of homophily, which posits that entities with similar attributes are more likely to form connections [45]. We apply this principle to guide our simulation, positing that links between bots and semantically-aligned communities appear more organic and thus less detectable. Accordingly, for each pair of similar communities, we select the two bots with the highest bot scores (i.e., those most easily detected by classifiers) from each community, creating bot pairs that serve as bridges. This strategy not only reinforces ties between aligned communities but also targets high-risk bots to potentially disperse detection pressure. For intra-community connections, we analyze the first-order neighbors of the directly controlled bot and identify any other controlled bots within the same community. Drawing on triadic closure theory—which suggests that nodes sharing common neighbors are more likely to connect—we form edges between such bot pairs within the community [46]. This fosters localized cohesion and enhances the emergence of collaborative behaviors, mimicking the organic growth of social ties in real-world networks. Together, these methods enable the simulation of multi-level coordination while maintaining computational efficiency. This algorithm is presented in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Coordinated Network Augmentation |

|

3.5. Reward Formulation

To simulate botnets that achieve holistic stealth, we design a composite reward function that integrates multiple reinforcement learning paradigms, as no single reward paradigm adequately addresses the full spectrum of this complex task.

To enhance the bot’s ability to emulate human behavior and improve collaborative evasion, this study introduces two reward terms. The first term serves as a dense shaping reward specifically for behavioral mimicry. It operates by calculating the improvement in the agent’s commonness (derived from Equation (6)) relative to a reference human cluster between consecutive time steps. Its core mechanism is to provide direct gradients that steer the bot’s feature distribution toward the statistical distribution of genuine users, thereby explicitly targeting the foundational objective of behavioral plausibility at the distribution level.

The second term is designed as a team reward. It operates by penalizing an increase in the number of other controlled bots detected within a single time step, thereby explicitly promoting cooperative strategies. This directly addresses correlated risk by incentivizing actions that reduce the exposure probability of the entire collective, such as forming less detectable interconnection patterns or avoiding behaviors that trigger cascading detection.

These newly introduced components extend and integrate with the reward functions established in our prior work, which categorized bots as either fake accounts or influencer bots, each with distinct objectives [36]. To formulate a complete composite reward, the foundational terms from this prior work are incorporated as core components within our new unified structure.

The fake account reward function from prior work primarily embeds an adversarial discriminative reward through the term involving the detector’s output. Simultaneously, it incorporates a sparse terminal reward, which incentivizes the long-term objective of remaining undetected. The influencer bot reward extends this by adding a term for influence, introducing an auxiliary objective that may trade off with stealth.

where l represents the time when the account is detected and suspended, is the number of followers at time t, represents whether the bot posts a tweet at time t, and is a discount factor that balances the trade-off between evasion and influence. The two aforementioned reward function terms will be added to these two reward functions to obtain the final reward function.

3.6. Virtual Environment

This study adopts the semi-simulated environment established in prior work [36], which safely model the dynamic development of bot accounts over time. It replicates the structure of a platform like X by constructing three directed graphs (for follow, retweet, and mention networks) alongside a user-feature matrix, all derived from a real-world dataset. Within this environment, the core dynamics of influence propagation and user engagement are governed by the following probabilistic rules: the probability of a normal user following a bot after it posts content is estimated based on the average follower growth rate of bots with the most similar user-generated content; the likelihood of a reciprocal “follow-for-follow” response is heuristically determined by a user’s existing friend-to-follower ratio; and the probability of a tweet being retweeted or mentioned is predicted using the average retweet growth rate of comparable bots. Two representative detection models are integrated into this dynamic setting to facilitate adversarial training and evaluation.

Random Forest (RF) Detector: This model was trained using the extensive feature set from Botometer [47]. The feature vector for each account consists of:

- Profile features: user name length, account age, follower count, etc.

- Friend features: mean account age of friends, maximum follower count among friends, etc.

- Network features: number of nodes and edges in the user’s retweet graph, etc.

This same feature set constitute the bot’s state representation in our simulation. To address class imbalance in the training data, bot samples were assigned a class weight of 3, while genuine user samples were assigned a weight of 1. We utilized the RandomForestClassifier from scikit-learn with default hyperparameters. The model was trained using the official TwiBot-22 dataset split.

BotRGCN Detector: We employed the official BotRGCN model and implementation provided within the TwiBot-22 benchmark repository [34]. It constructs a heterogeneous graph from user follow relationships and learns node representations by integrating four modalities: (1) user-generated content, (2) user description, (3) numerical profile features, and (4) the neighborhood structure. Consistent with the RF detector, training and evaluation were performed on the official TwiBot-22 split.

4. Experiment

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Dataset

The study employs the TwiBot-22 dataset to initialize the virtual environment and train bot detection models, owing to its large scale, multi-dimensional data, and reliable annotations [4]. This dataset comprises profiles, tweets, and social relations from approximately one million X accounts, collected through a breadth-first search (BFS) strategy starting from a set of seed users and expanding along follower-followee connections.

4.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

Our evaluation is based on multiple independent episodes. Each episode simulates one bot account from initialization until it is removed by the detector or reaches the maximum step . The evaluation begins with several metrics designed to assess the bot’s influence and evasion capability: , defined as the number of users reached by the bot’s tweets, serves as a measure of influence; the number of views quantifies the overall impact during one episode [36]; the survival rate, defined as the proportion of episodes in which the bot avoids detection throughout its simulation, reflects evasion ability [6]; the bot score evaluates detectability under varying detection thresholds; and the number of other controlled bots detected is reported to assess inter-bot collaboration. The values in parentheses in the results tables indicate the standard deviation of the corresponding evaluation metric across the episodes, reflecting the stability of the performance.

To further evaluate the behavioral mimicry of the bots, we incorporate a visualization-based metric. A t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) projection is generated using a feature set that captures both social engagement patterns (followers count, following count, list count) and content interaction characteristics (number of hashtags, number of mentions). These plots visually compare the distribution of the simulated bots against randomly sampled genuine users, providing an intuitive assessment of their resemblance to organic accounts.

4.1.3. Implementation

To assess the bot’s effectiveness in various roles, we conducted similar experiments where the bot was trained to simulate a fake account or an influencer. The experiments were conducted in 4 different settings: fake account or influencer versus RF-based or BotRGCN. To test the effectiveness of the proposed enhancements and compare with other prior work, we conducted the following experiments:

- ACORN [8]. This method employs a reinforcement learning framework comprised of an action selection agent and a target selection agent. The action space includes fundamental behaviors such as posting, retweeting, mentioning, and following. The target selection agent operates in a discrete action space mapped to a set of randomly sampled users.

- Rui et al. [36]. Extending the ACORN framework, this model incorporates an expanded action set that includes additional behaviors such as profile updating. Moreover, it enhances the target selection mechanism by mapping the agent’s action space to a set of pre-selected users.

- Base. The agent’s action space is constrained to prevent any inter-bot cooperative actions. Furthermore, the reward function excludes both the commonness term and the collaboration term.

- Base + Collaboration. This setup evaluates the effect of inter-bot cooperation. The action space is expanded to allow cooperative actions between bots, and the collaboration reward term is activated. The commonness reward term, however, is disabled in this setting.

- Base + Commonness. This setup integrates the commonness reward term to incentivize human-like behavior imitation. However, the action space remains constrained, preventing inter-bot cooperation, and the collaboration reward term is not computed.

- Full. This is our complete proposed strategy. The agent operates with the full action space, permitting inter-bot cooperation. Simultaneously, the reward function incorporates both proposed terms: the commonness reward and the collaboration reward.

To align with the two bot types, we selected two representative user clusters from our dataset for the bot strategy model to emulate. The first cluster (Cluster A) consists of users exhibiting generally low activity levels, characterized by infrequent posting and minimal social interactions. The second cluster (Cluster B) consists of relatively more active users who demonstrate consistently high engagement. This enables differentiated behavioral modeling corresponding to each bot type. We conducted experiments using both clusters to simulate fake accounts. However, since the behavioral patterns of Cluster A users fundamentally conflict with influencer objectives, we excluded Cluster A emulation for influencer bot simulations.

The simulation environment and reinforcement learning framework were implemented using PettingZoo and Stable Baselines3 [48,49]. In all subsequent experiments, the bot strategy models were trained for 100,000 steps and evaluated over 1000 episodes, with all hyperparameters retained at their default values. was set to 500, as preliminary observations indicated that most bots are detected within this period. This implies a maximum of 50 potential enforcement actions per bot. This periodic enforcement model serves as an experimental assumption that balances several practical considerations. Firstly, it prevents the immediate termination of bots in early training stages (as a new account might be statistically likely to be flagged), which would hinder learning and does not reflect the reality that platforms often require sustained suspicious activity for enforcement. Secondly, it maintains a realistic monitoring pressure. Given that an active bot in our simulation accumulates approximately two months of operational lifespan within 500 steps, this 10-step interval corresponds to a platform enforcement check roughly once per day—a frequency we consider plausible for monitoring and intervention. This design allows us to consistently evaluate the bots’ ability to maintain long-term stealth under periodic scrutiny, without overestimating the detector’s aggressiveness or underestimating its capability.

4.2. Fake Account Simulation

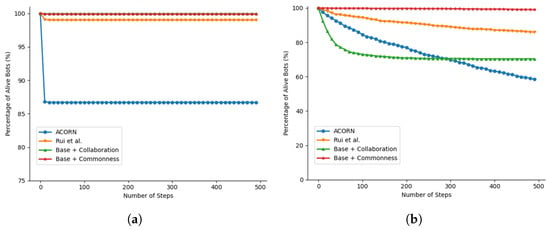

The bots acted as fake accounts in these experiments and focused on evading detection. The final survival rate and average bot score are presented in Table 1. The Commonness reward effectively enables behavioral mimicry, but its success heavily depends on the target cluster, with high-activity imitation (Cluster B) being inherently riskier and resulting in lower survival. The Collaboration reward alone results in a survivability of 100%, and no other controlled bots were detected during its operation. This lack of additional detections can be explained by two factors: first, the selected bots were rarely detected by the RF-based detector to begin with, leaving little room for further improvement; second, the output of the RF-based detector remained stable throughout the simulation, showing minimal fluctuation in the overall number of detections. As illustrated in Figure 4a, the survival rate over time further supports the consistent performance under this detector. The Full model, which integrates both rewards, demonstrates strong resilience. It raises the survival rate of Cluster B from 76.6% to 98.0%, indicating that collaboration helps mitigate the risks associated with high-activity mimicry, while also maintaining complete covertness for the broader bot network, with no additional bots detected. The slightly elevated bot score in some experiments, compared to prior work, reflects a strategic trade-off where the agent prioritizes longer survival over a minimally lower detection score, resulting in a higher overall survival rate.

Table 1.

Results of fake account simulation experiments.

Figure 4.

Bot survival rate throughout the fake account simulation experiments [8,36]. (a) Bot survival rate against the RF detector. (b) Bot survival rate against BotRGCN.

The overall lower survival rates across all methods against BotRGCN reveal more challenging dynamics compared to the RF-based detector. Notably, the Base + Commonness strategy again proves to be the most effective single strategy, achieving a high survival rate of 99.1% when mimicking low-activity users (Cluster A). This superiority is further illustrated in the temporal survival analysis in Figure 4b, which shows its curve consistently sustained at near 100% throughout the entire simulation. This not only underscores its robustness against a more advanced detector, but also highlights the advantage of explicit behavioral mimicry against existing studies (58.5% and 85.9%). However, the performance again drops significantly when mimicking the high-activity cluster (Cluster B), reinforcing the inherent risk of this strategy. The evaluation of collaborative strategies indicates that the Collaboration reward contributes to improved survivability. This is supported by the observed outcomes: the Base + Collaboration model assisted 1703 bots in evading detection, and the Full model enabled 1876 and 1808 bots in Cluster A and Cluster B, respectively, to avoid detection. These results suggest that coordinated network activity can function as a form of disguise, thereby helping to protect the broader bot network from the GNN-based detector. Interestingly, the temporal dynamics reveal that although the Base + Collaboration curve drops rapidly initially, its rate of decline substantially slows afterward, allowing its final survival rate to exceed that of ACORN and approach the level of Rui et al. We believe the reason is that once a certain threshold of networked interaction is established, the collaborative mechanism may begin to provide enhanced concealment by mimicking the complex, organic patterns of human social networks.

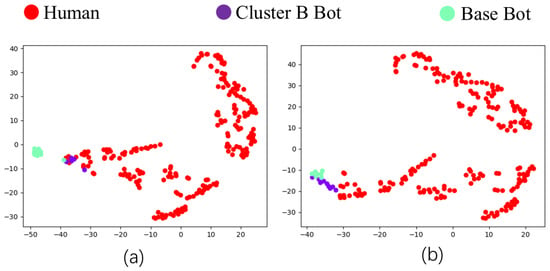

The t-SNE visualization presented in Figure 5 provides compelling qualitative evidence supporting the quantitative results. In both plots—corresponding to the RF-based and BotRGCN detectors—a consistent pattern emerges: bots employing the Commonness reward to mimic either Cluster A or Cluster B successfully blend into the feature distribution of genuine human accounts, forming overlapping clusters. On the other hand, bots trained with the Base strategy remain distinctly separated from the human clusters, forming isolated and detectable outliers. This visual divergence clearly demonstrates that behavioral mimicry is highly effective at embedding bots within organic user populations in the feature space, while bots that do not explicitly optimize for human-like features are easily identifiable by their anomalous feature combinations.

Figure 5.

t-SNE graph for fake account simulation. (a) t-SNE graph against the RF detector. (b) t-SNE graph against BotRGCN.

4.3. Influencer Simulation

In the following experiments, the bots acted as influencers and had to strike a balance between avoiding detection and expanding their influence. Similar experiments were conducted to assess the performance of different variations of the bot strategy model. Results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of influencer simulation experiments.

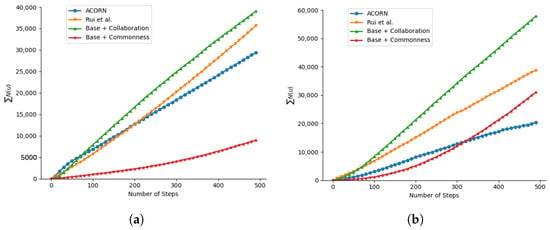

The results against the RF-based detector clearly demonstrate the superiority of the proposed mechanisms for influencer bots. The Base model, benefiting from its refined target selection strategy, achieved perfect 100% survival and generated over 8 million views, significantly outperforming both the ACORN baseline and the previous Rui et al. approach [36]. This advantage was further amplified by the Base + Collaboration model, which attained a 99.4% survival rate and achieved the highest overall influence with over 9 million views, proving that coordinated activity enhances a bot network’s reach and resilience. The temporal dynamics of follower accumulation, as shown in Figure 6a, also provide evidence: the follower growth curve for Base + Collaboration consistently resides above all other methods throughout the simulation duration. In contrast, the Base + Commonness strategy—which encourages mimicry of relatively high-activity human behavior—proved counterproductive for influence campaigns. It limited the bot’s reach to just 316 thousand views, as its objective conflicts directly with the goal of maximizing visibility. The Full model only partially mitigated this conflict, confirming that advanced targeting and cooperation are the primary drivers of performance for influencer bots. It is also notable that no other controlled bots were detected during these simulations.

Figure 6.

The number of followers throughout the influencer simulation experiments [8,36]. (a) The number of followers against the RF detector. (b) The number of followers against BotRGCN.

The results against the BotRGCN detector again underscore the exceptional value of inter-bot collaboration for influencer bots operating under advanced threat models. The Base + Collaboration model delivered the most robust performance, achieving a high survival rate of 86.6% while simultaneously generating the highest influence metrics by a significant margin, with 57,388 followers and almost 13 million views. This sustained growth advantage is visually confirmed in Figure 6b, where the follower accumulation curve for Base + Collaboration maintains a clear and consistent lead over all other methods throughout the temporal progression of the simulation. Remarkably, this cooperative strategy demonstrated a network-wide protective effect, with collaboration resulting in 1,905 other bots that was to be detected being covered. This demonstrates that cooperative strategies are highly effective for amplifying reach and maintaining stealth against a sophisticated graph-based detector. The Base + Commonness strategy also achieved a high survival rate of 92.2%, confirming that behavioral mimicry aids evasion. However, this again came at a severe cost to influence, reducing view counts compared to the collaborative approach, which highlights the fundamental misalignment between passive mimicry and influence goals. Surprisingly, the Full model dropped in both survival and influence, along with only 1576 other bots avoided detection, suggesting that the combined rewards create conflicting policy signals under the complex detection patterns of a GNN, causing the agent to fail at both objectives.

The t-SNE visualizations presented in Figure 7 for influencer bots reveal a detector-dependent divergence in mimicry effectiveness. Against the RF-based detector, bots mimicking Cluster B successfully integrate within the human feature distribution, consistent with trends observed earlier. However, against BotRGCN, while these same bots form clusters nearer to human users than Base bots do, they fail to fully blend in. This reduced integration aligns with their quantitative behavior: the substantial increase in followers and views under BotRGCN exposure indicates the adoption of more aggressive influence-seeking behaviors. Such activity, while boosting metrics, also produces feature patterns distinct enough to remain partially discernible from normal users.

Figure 7.

t-SNE graph for influencer simulation. (a) t-SNE graph against the RF detector. (b) t-SNE graph against BotRGCN.

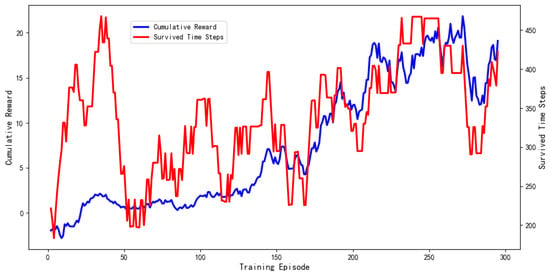

Figure 8 presents the learning progression of the Base+Collaboration model in the Influencer vs. BotRGCN scenario, plotting both the cumulative reward and the survival time steps across training episodes. The overall trend demonstrates a clear monotonic increase in the cumulative reward, coupled with a long-term rising trend in survival steps, confirming that the agent successfully improved its policy through autonomous environmental interaction. A notable phenomenon provides deeper insight into the learning dynamics: the survival steps curve exhibits an early peak, followed by a decline and a subsequent gradual recovery aligned with the reward increase. This pattern is indicative of the agent’s exploration-exploitation trade-off within a multi-objective optimization landscape. Initially, the agent discovered a strategy that yielded high evasion, likely by being overly cautious or inactive. However, this strategy proved suboptimal for the influencer role, as it failed to accumulate influence, resulting in a low cumulative reward. Driven by the reward signal, the agent then explored beyond this local optimum, gradually refining a more sophisticated policy that balanced concealment with strategic activity. The eventual concurrent rise of both metrics indicates the emergence of a balanced strategy capable of meeting the dual objectives of an influencer bot.

Figure 8.

Cumulative reward and survival time steps of the Base+Collaboration model in training (Influencer vs. BotRGCN).

5. Conclusions and Discussion

In this paper, we propose a simulation framework for advanced social botnets that jointly incorporates a Human-like Behavior Module and a Target-Aware Coordination Module. This integrated design enables the optimization of individual behavioral authenticity and group-level strategic coordination, addressing a gap in social bot research. Our experimental results validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach and suggest the following conclusions:

- The proposed architecture, combining specialized modules for behavioral modeling and strategic coordination, establishes a viable foundation for simulating advanced social botnets. Experimental results indicate that this dual-module approach enables bots to achieve improved survivability and influence, showing advantages over the baseline methods across multiple detection scenarios.

- The proposed reward mechanism based on distributional likelihood shows effectiveness in aligning bot behavior with genuine user patterns. Evaluation through quantitative metrics (e.g., survival rate) and qualitative visualization (t-SNE) suggests that this approach helps reduce detectable behavioral divergence, particularly when emulating low-activity user profiles.

- The collaboration mechanism showed particular effectiveness against advanced detection, with influencer bots achieving an 86.6% survival rate while accumulating substantial influence against the BotRGCN detector. This strategy also contributed to network-wide protection by reducing peer detections, supporting the observation that structured cooperation can aid in evading graph-based detectors.

The primary theoretical contribution of this work is to provide an integrated framework that explicitly models social bot concealment as a function of two interdependent dimensions: behavioral plausibility and coordinated strategy. Prior research has often addressed these dimensions in isolation. By combining them into a single simulation paradigm, this work offers a more systematic lens for analyzing how bots can evade detection by blending into social contexts both as individual actors and as part of a collective. This framework shifts the analytical focus from isolated evasion tactics to the study of adaptive, socially aware bot collectives, thereby contributing to a more structured understanding of advanced, coordinated social threats.

This framework establishes a foundation for several promising research directions that could extend its theoretical depth and practical utility.

- While the current human-like behavior module relies on explicit probabilistic modeling of clustered user activities, future iterations could explore more flexible generative paradigms. Energy-based models, for instance, define data likelihood through a scalar energy function without requiring normalized density estimation. This formulation offers enhanced flexibility in capturing multi-modal and non-parametric behavioral distributions, potentially enabling the generation of subtler, less template-driven agent behaviors.

- Another promising extension of this work involves integrating principles from Evolutionary Algorithm-based adversarial training [50,51]. Inspired by this field, the parameters of the behavioral and coordination modules could be encoded as a genome and evolved under iterative adversarial pressure from detection systems. Another key focus would be maintaining strategic diversity throughout this evolutionary process to model a broad range of adaptive threat phenotypes. Such a direction aligns with foundational insights from the evolutionary nature of social bots.

- Building upon the experimental validation within our chosen technical stack, another significant future direction involves establishing a standardized benchmarking framework for adversarial social agent research. While our controlled implementation ensures fair comparisons of algorithmic contributions, cross-framework evaluation remains an open challenge. A constructive path forward is to encapsulate the behavioral and coordination strategies proposed here into a suite of reference agents, enabling systematic evaluation across diverse MARL libraries and swarm systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.J.; methodology, R.J.; software, R.J.; validation, R.J.; formal analysis, R.J.; investigation, R.J.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, R.J.; writing—original draft preparation, R.J.; writing—review and editing, R.J.; visualization, R.J.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, R.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in TwiBot-22 at https://github.com/LuoUndergradXJTU/TwiBot-22 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Provincial Key Research and Development Program of Anhui (202423l10050033) and the Ministry of Public Security Science and Technology Plan (Project Number 2023JSZ01).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cresci, S.; Di Pietro, R.; Petrocchi, M.; Spognardi, A.; Tesconi, M. The paradigm-shift of social spambots: Evidence, theories, and tools for the arms race. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web Companion, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 963–972. [Google Scholar]

- Hajli, N.; Saeed, U.; Tajvidi, M.; Shirazi, F. Social bots and the spread of disinformation in social media: The challenges of artificial intelligence. Br. J. Manag. 2022, 33, 1238–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, L.; Neely, S.; Keller, T.E.; Scharf, R.; Vasquez, F.E. Rise of the machines? Examining the influence of social bots on a political discussion network. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2022, 40, 264–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Tan, Z.; Wan, H.; Wang, N.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, W.; Lei, Z.; Yang, S.; et al. TwiBot-22: Towards graph-based Twitter bot detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.04564. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Walt, E.; Eloff, J. Using machine learning to detect fake identities: Bots vs humans. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 6540–6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qiao, X.; Xie, Y.; Nie, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, A. My brother helps me: Node injection based adversarial attack on social bot detection. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October–3 November 2023; pp. 6705–6714. [Google Scholar]

- Cresci, S.; Petrocchi, M.; Spognardi, A.; Tognazzi, S. Better safe than sorry: An adversarial approach to improve social bot detection. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Web Science, Boston, MA, USA, 30 June–3 July 2019; pp. 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.; Tran-Thanh, L.; Lee, D. Socialbots on fire: Modeling adversarial behaviors of socialbots via multi-agent hierarchical reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022, Virtual Event, Lyon, France, 25–29 April 2022; pp. 545–554. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X.; Peng, H.; Li, A. Adversarial socialbots modeling based on structural information principles. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 392–400. [Google Scholar]

- Cresci, S.; Di Pietro, R.; Petrocchi, M.; Spognardi, A.; Tesconi, M. Social fingerprinting: Detection of spambot groups through DNA-inspired behavioral modeling. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2017, 15, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, J.V.F.; Fernandes, J.H.C.; Gondim, J.J.C.; Ralha, C.G. Bot development for social engineering attacks on Twitter. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.11778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, J.V.F.; Ralha, C.G.; Gondim, J.J.C. Twitter bot detection with reduced feature set. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics (ISI), Arlington, VA, USA, 9–10 November 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, C.A.; Varol, O.; Ferrara, E.; Flammini, A.; Menczer, F. Botornot: A system to evaluate social bots. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference Companion on World Wide Web, Montréal, QC, Canada, 11–15 April 2016; pp. 273–274. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.; He, Y.; Jiang, X.; Cao, J.; Li, Q. Combating the evasion mechanisms of social bots. Comput. Secur. 2016, 58, 230–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beskow, D.M.; Carley, K.M. Bot-hunter: A tiered approach to detecting & characterizing automated activity on twitter. In Proceedings of the Conference Paper. SBP-BRiMS: International Conference on Social Computing, Behavioral-Cultural Modeling and Prediction and Behavior Representation in Modeling and Simulation, Washington, DC, USA, 10–13 July 2018; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Varol, O.; Ferrara, E.; Davis, C.; Menczer, F.; Flammini, A. Online human-bot interactions: Detection, estimation, and characterization. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Montreal, QC, Canada, 15–18 May 2017; Volume 11, pp. 280–289. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.C.; Varol, O.; Davis, C.A.; Ferrara, E.; Flammini, A.; Menczer, F. Arming the public with artificial intelligence to counter social bots. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 1, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qurishi, M.; Alrubaian, M.; Rahman, S.M.M.; Alamri, A.; Hassan, M.M. A prediction system of Sybil attack in social network using deep-regression model. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 87, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudugunta, S.; Ferrara, E. Deep neural networks for bot detection. Inf. Sci. 2018, 467, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, M.; Jones, J.H.; Uzuner, O. Deep contextualized word embedding for text-based online user profiling to detect social bots on twitter. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW), Sorrento, Italy, 17–20 November 2020; pp. 480–487. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.; Wan, H.; Wang, N.; Li, J.; Luo, M. Satar: A self-supervised approach to twitter account representation learning and its application in bot detection. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Virtual Event, Queensland, Australia, 1–5 November 2021; pp. 3808–3817. [Google Scholar]

- Cardaioli, M.; Conti, M.; Di Sorbo, A.; Fabrizio, E.; Laudanna, S.; Visaggio, C.A. It’sa matter of style: Detecting social bots through writing style consistency. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computer Communications and Networks (ICCCN), Athens, Greece, 19–22 July 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Loyola-González, O.; Monroy, R.; Rodríguez, J.; López-Cuevas, A.; Mata-Sánchez, J.I. Contrast pattern-based classification for bot detection on twitter. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 45800–45817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Nguyen, U.T. Twitter bot detection using bidirectional long short-term memory neural networks and word embeddings. In Proceedings of the 2019 First IEEE International Conference on Trust, Privacy and Security in Intelligent Systems and Applications (TPS-ISA), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 12–14 December 2019; pp. 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Dukić, D.; Keča, D.; Stipić, D. Are you human? Detecting bots on Twitter Using BERT. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 7th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 6–9 October 2020; pp. 631–636. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Gutiérrez, D.; Hernández-Peñaloza, G.; Hernández, A.B.; Lozano-Diez, A.; Álvarez, F. A deep learning approach for robust detection of bots in twitter using transformers. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 54591–54601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Wang, B.; Gong, N.Z. Random walk based fake account detection in online social networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 47th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks (DSN), Denver, CO, USA, 26–29 June 2017; pp. 273–284. [Google Scholar]

- Breuer, A.; Eilat, R.; Weinsberg, U. Friend or faux: Graph-based early detection of fake accounts on social networks. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2020, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–24 April 2020; pp. 1287–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Ali Alhosseini, S.; Bin Tareaf, R.; Najafi, P.; Meinel, C. Detect me if you can: Spam bot detection using inductive representation learning. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the 2019 World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; pp. 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.; Tan, Z.; Li, R.; Luo, M. Heterogeneity-aware twitter bot detection with relational graph transformers. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtually, 22 February–1 March 2022; Volume 36, pp. 3977–3985. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Tan, Z.; Wang, H.; Feng, S.; Zheng, Q.; Luo, M. Botmoe: Twitter bot detection with community-aware mixtures of modal-specific experts. In Proceedings of the 46th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Taipei, Taiwan, 23–27 July 2023; pp. 485–495. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, R.; Li, Y.; Cui, K.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Xie, H. Rosgas: Adaptive social bot detection with reinforced self-supervised gnn architecture search. ACM Trans. Web 2023, 17, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liu, H.; Yang, R.; Peng, H.; Wang, X.; Liao, Y.; Zhou, P. Botdgt: Dynamicity-aware social bot detection with dynamic graph transformers. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.15070. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.; Wan, H.; Wang, N.; Luo, M. BotRGCN: Twitter bot detection with relational graph convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining, Virtual Event, The Netherlands, 8–11 November 2021; pp. 236–239. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.; Tan, Z.; Lei, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zheng, Q.; Luo, M. LMbot: Distilling graph knowledge into language model for graph-less deployment in twitter bot detection. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Merida, Mexico, 4–8 March 2024; pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, R.; Liao, Y. Prevention Is Better than Cure: Exposing the Vulnerabilities of Social Bot Detectors with Realistic Simulations. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Lan, X.; Lu, Z.; Mao, J.; Piao, J.; Wang, H.; Jin, D.; Li, Y. S3: Social-network Simulation System with Large Language Model-Empowered Agents. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.14984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Wan, H.; Wang, N.; Tan, Z.; Luo, M.; Tsvetkov, Y. What Does the Bot Say? Opportunities and Risks of Large Language Models in Social Media Bot Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.00371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, A.C.; Frey, H.C. Probabilistic Techniques in Exposure Assessment: A Handbook for Dealing with Variability and Uncertainty in Models and Inputs; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Delignette-Muller, M.L.; Dutang, C. fitdistrplus: An R package for fitting distributions. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 64, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklar, A. Random variables, joint distribution functions, and copulas. Kybernetika 1973, 9, 449–460. [Google Scholar]

- Standen, M.; Kim, J.; Szabo, C. Adversarial machine learning attacks and defences in multi-agent reinforcement learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Chen, T.; Wu, W. Enhanced group influence maximization in social networks using deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2024, 12, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, M.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Cook, J.M. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Miao, Z.; Jiang, T. A new joint approach with temporal and profile information for social bot detection. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2022, 2022, 9119388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, J.; Black, B.; Grammel, N.; Jayakumar, M.; Hari, A.; Sullivan, R.; Santos, L.S.; Dieffendahl, C.; Horsch, C.; Perez-Vicente, R.; et al. Pettingzoo: Gym for multi-agent reinforcement learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 15032–15043. [Google Scholar]

- Raffin, A.; Hill, A.; Gleave, A.; Kanervisto, A.; Ernestus, M.; Dormann, N. Stable-Baselines3: Reliable Reinforcement Learning Implementations. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Xu, C.; Yao, X.; Tao, D. Evolutionary generative adversarial networks. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2019, 23, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Q.; Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Yang, S.; Zhan, T. A generative adversarial networks model based evolutionary algorithm for multimodal multi-objective optimization. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2024, early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.