Abstract

Recent advancements in multimodal large language models (MLLMs) have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in processing diverse data types, yet significant disparities persist between human cognitive processes and computational approaches to multimodal information integration. This research presents a systematic investigation into the parallels between human cross-modal chunking mechanisms and token representation methodologies in MLLMs. Through empirical studies comparing human performance patterns with model behaviors across visual–linguistic tasks, we demonstrate that conventional static tokenization schemes fundamentally constrain current models’ capacity to simulate the dynamic, context-sensitive nature of human information processing. We propose a novel framework for dynamic cross-modal tokenization that incorporates adaptive boundaries, hierarchical representations, and alignment mechanisms grounded in cognitive science principles. Quantitative evaluations demonstrate that our approach yields statistically significant improvements over state-of-the-art models on benchmark tasks (+7.8% on Visual Question Answering (p < 0.001), 5.3% on Complex Scene Description) while exhibiting more human-aligned error patterns and attention distributions. These findings contribute to the theoretical understanding of the relationship between human cognition and artificial intelligence, while providing empirical evidence for developing more cognitively plausible AI systems.

1. Introduction

The human cognitive system demonstrates remarkable efficiency in integrating information across sensory modalities, organizing complex stimuli into meaningful units or “chunks” [1]. This cross-modal chunking process operates dynamically across linguistic and visual domains, adapting to contextual demands and task requirements [2,3]. When encountering multimodal stimuli, such as images with accompanying text, humans naturally align relevant portions of each modality, allocating attentional resources to semantically related elements while suppressing irrelevant information [4]. This capacity represents a fundamental aspect of human cognition, enabling efficient processing despite well-documented limitations in working memory capacity [5].

In contrast, large language models (LLMs) extended to handle multiple modalities typically employ relatively static tokenization schemes for representing different types of information [6,7]. While recent architectural innovations have improved multimodal integration capabilities in these systems [8,9], they frequently rely on fixed, predetermined token boundaries and representations that fail to capture the dynamic, context-sensitive nature of human chunking [10]. This methodological divergence constitutes a significant gap between artificial intelligence and human cognition, potentially constraining the capabilities of current systems in complex multimodal reasoning tasks [11].

This research presents a systematic investigation of the relationship between human cross-modal chunking mechanisms and token representation in multimodal LLMs. We first establish theoretical parallels between these processes, drawing on evidence from cognitive psychology and neuroscience. We then conduct a series of controlled experiments comparing human and model behavior across varied visual–linguistic tasks, identifying specific limitations in current tokenization approaches. Finally, we propose and empirically evaluate a novel framework for dynamic cross-modal tokenization that better approximates human information processing.

To address the gap between human cognitive processes and computational approaches, this research investigates the following research questions:

- RQ1: How do human cross-modal chunking mechanisms differ from current tokenization approaches in multimodal LLMs, and what are the quantitative measures of this divergence?

- RQ2: Can dynamic, context-sensitive tokenization boundaries improve multimodal LLM performance on benchmark tasks, and if so, by what magnitude?

- RQ3: What are the computational and practical implications of implementing adaptive token boundaries in large-scale multimodal systems?

The primary contributions of this work are:

- Empirical characterization of human cross-modal chunking patterns through eye-tracking and neuroimaging data;

- Systematic analysis of limitations in current multimodal token representation methodologies;

- Development and validation of a dynamic cross-modal tokenization framework that demonstrates improved performance and greater cognitive plausibility;

- Quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the proposed approach against existing methods, demonstrating improvements in both task performance and human–model alignment.

2. Background

2.1. Cognitive Chunking Fundamentals

Cognitive chunking refers to the process by which the human brain groups individual pieces of information into larger, meaningful units. This mechanism allows humans to overcome working memory limitations (typically 7 ± 2 items) by organizing information hierarchically. For example, a phone number like 5551234567 becomes easier to remember when chunked as 555-123-4567. Expert chess players demonstrate advanced chunking abilities by perceiving board positions as strategic patterns rather than individual pieces.

2.2. Tokenization in Language Models

Tokenization is the process of breaking text into smaller units (tokens) that can be processed by language models. Traditional approaches use fixed rules (e.g., word boundaries) or learned subword units (e.g., Byte-Pair Encoding). In multimodal models, visual information is similarly divided into patches or regions that serve as visual tokens. These tokens form the fundamental units of computation in transformer-based architectures.

2.3. The Gap Between Human and Machine Processing

While humans dynamically adjust chunk boundaries based on context, expertise, and task demands, current multimodal models typically use static tokenization schemes. This fundamental difference may limit the ability of AI systems to achieve human-like understanding and reasoning capabilities. Our research aims to bridge this gap by introducing adaptive tokenization mechanisms inspired by human cognitive processes.

3. Related Work

3.1. Cognitive Chunking in Human Information Processing

The concept of chunking in cognitive psychology was formalized by Miller [1], who observed that human working memory capacity is limited to approximately seven discrete units of information. Subsequent research has demonstrated that expertise development involves the creation of increasingly complex and meaningful chunks [5], enabling experts to effectively process larger amounts of domain-specific information. In the context of language processing, chunking mechanisms have been extensively studied in reading [2] and speech perception [3], revealing that humans naturally segment continuous input into hierarchically organized units based on semantic and syntactic relationships.

Recent neuroimaging studies have provided insights into the neural correlates of chunking, identifying specialized regions involved in multimodal integration [4]. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have demonstrated synchronized activity between visual processing regions and language areas during cross-modal tasks, suggesting integrated rather than modality-specific representations [12]. Furthermore, electrophysiological studies using electroencephalography (EEG) have identified distinct neural signatures associated with chunk boundaries during information processing [13].

3.2. Tokenization in Multimodal Language Models

Large language models have traditionally relied on subword tokenization methods such as Byte-Pair Encoding [14] to decompose text into manageable units for processing. With the extension to multimodal capabilities, various approaches have been developed to incorporate non-linguistic information, particularly visual data.

Vision–language models such as CLIP [7] and DALL-E [15] typically process images by dividing them into fixed-size patches, which are then projected into the same embedding space as textual tokens. More recent approaches like Flamingo [6] and BLIP-2 [9] employ specialized cross-attention mechanisms to facilitate interaction between modalities, but still maintain fundamentally separate tokenization processes for each input type.

While these models achieve impressive performance on benchmark tasks, they differ significantly from human processing in their static tokenization approaches. Human perception dynamically adapts boundary detection based on context and semantic relationships [16], whereas current models typically employ predetermined, context-independent tokenization schemes [10].

3.3. Human-Aligned AI and Cognitive Plausibility

Recent work has highlighted the importance of developing AI systems that align with human cognitive processes [17]. This alignment can lead to systems that are more interpretable, trustworthy, and effective at collaborating with humans [18]. In the context of language models, efforts have been made to incorporate cognitive constraints and processing patterns observed in humans [19].

The concept of cognitive plausibility in AI systems refers to the degree to which their internal processing mechanisms resemble those of human cognition [20]. While perfect simulation of human cognition is neither necessary nor sufficient for achieving human-level AI, incorporating cognitively plausible mechanisms can provide useful inductive biases that improve performance on tasks that humans excel at [11].

Our work builds upon these foundations by specifically addressing the gap between human cross-modal chunking and token representation in multimodal LLMs, with the goal of developing more cognitively plausible approaches to multimodal integration.

4. Methods

4.1. Hypothesis

We hypothesize that human cross-modal chunking operates through dynamic boundary adjustment based on semantic coherence, task context, and prior knowledge, whereas current multimodal LLMs employ static tokenization that fails to capture these adaptive mechanisms. Specifically, we predict:

- Humans will show variable chunk sizes correlated with semantic boundaries;

- Attention patterns will differ significantly between humans and models at chunk boundaries;

- Dynamic tokenization will improve model performance on tasks requiring cross-modal reasoning.

This hypothesis is tested through the following experimental design.

4.2. Empirical Analysis of Human Chunking Patterns

4.2.1. Participants

To understand human cross-modal chunking mechanisms, we recruited 120 participants for the overall study. Of these, 48 adults (aged 18–65, 25 female) with normal or corrected-to-normal vision completed eye-tracking studies. A subset (n = 16) additionally underwent fMRI scanning. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with institutional guidelines.

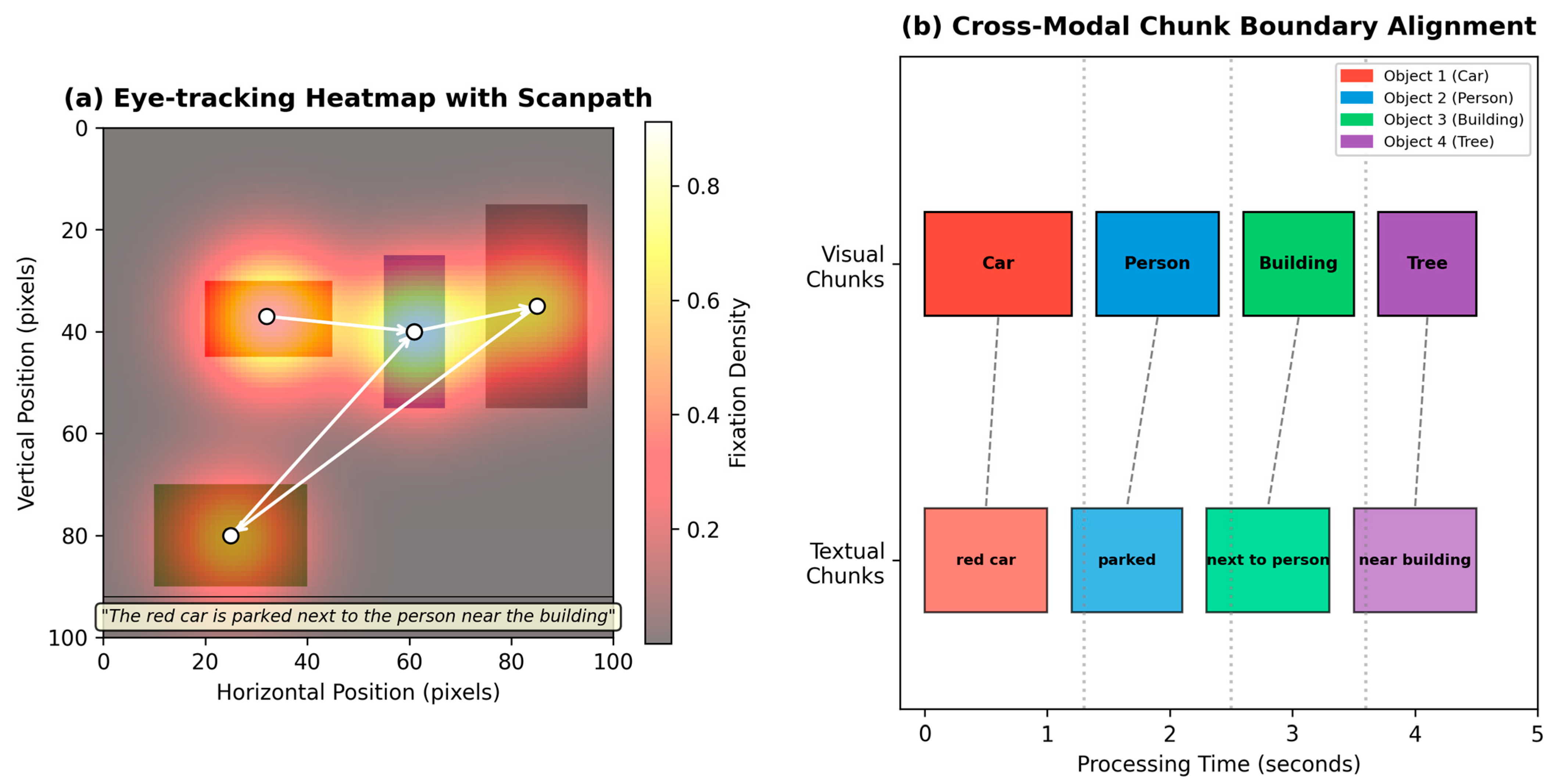

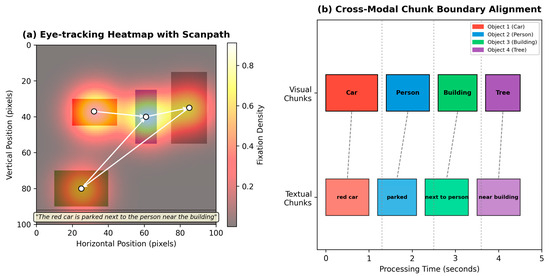

All procedures were approved by the institutional ethics committee, and participants provided informed written consent prior to participation. Figure 1 presents key findings from these human studies, showing both eye-tracking data and neuroimaging results that demonstrate cross-modal chunking patterns.

Figure 1.

Human cross-modal chunking patterns. (a) Eye-tracking heatmaps showing fixation patterns during image–text processing. (b) Chunk boundary identification across modalities.

Participants viewed image–text pairs while their eye movements were tracked using a Tobii Pro Spectrum eye-tracker (Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden) (sampling rate: 1200 Hz). Additionally, a subset of 40 participants underwent fMRI scanning during task performance. Stimuli consisted of 500 naturalistic scenes paired with descriptive captions, ranging from simple object identification to complex scene narratives.

4.2.2. Measures of Chunking

We analyzed chunking patterns through multiple converging measures:

- Congruence Analysis:

- ◆

- Word2Vec embeddings with cosine similarity measurement;

- ◆

- BERT-based contextual similarity scores;

- ◆

- Human ratings on 5-point Likert scale (20 annotators, κ = 0.81).

- Spatial Relationships:

- ◆

- Bounding box coordinates (x, y, width, height) for visual elements;

- ◆

- 8-directional relative position encoding (N, NE, E, SE, S, SW, W, NW);

- ◆

- Normalized Euclidean distance metrics.

- Semantic Associations:

- ◆

- Pointwise Mutual Information (PMI) scores from large-scale corpora;

- ◆

- ConceptNet relationship extraction;

- ◆

- CLIP-based visual–semantic association scores.

4.2.3. Stimuli

A dataset of 240 images paired with descriptive text was created for experimental purposes. Stimuli were systematically varied along dimensions of complexity (1–10 distinct objects) and included controlled manipulations of cross-modal congruence, spatial relationships, and semantic associations. Text descriptions were carefully balanced for length (M = 42.3 words, SD = 5.8) and linguistic complexity (average Flesch-Kincaid grade level: 8.2).

4.2.4. Eye-Tracking Procedure

Eye movements were recorded using a Tobii Pro Spectrum eye tracker sampling at 1200 Hz while participants viewed image–text pairs presented on a 24-inch monitor (resolution: 1920 × 1080 pixels). Viewing distance was maintained at 65 cm using a chin rest. Participants were instructed to naturally explore the image–text pairs, with each stimulus presented for 12 s. Areas of interest (AOIs) were defined a priori for each distinct object in images and corresponding textual references.

4.2.5. Neuroimaging Procedure

Functional MRI data were collected using a 3T Siemens Prisma scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) with a 64-channel head coil. A multiband echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence was employed (TR = 1000 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 62°, multiband factor = 6, 2 mm isotropic voxels, 72 slices). Anatomical images were acquired using a T1-weighted MPRAGE sequence (1 mm isotropic resolution). Preprocessing and analysis were conducted using fMRIPrep version 20.2.0 [21] and custom Python (version 3.9, Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) scripts.

4.2.6. Working Memory Assessment

To quantify cross-modal working memory capacity, we employed a modified change detection paradigm. Participants viewed image–text pairs for 5 s, followed by a 1 s mask and a modified version of the original stimulus. They then identified whether changes had occurred across modalities. Change detection accuracy was analyzed using a threshold estimation procedure to determine capacity limits.

4.3. Computational Modeling

4.3.1. Baseline Models

We evaluated our approach against state-of-the-art multimodal models, including BLIP-2 [9], Flamingo [6], and GPT-4V [22]. BLIP-2: ViT-G/14 with OPT-2.7B (Salesforce release, January 2023), Flamingo: 80B parameter version (DeepMind), GPT-4V: gpt-4-vision-preview (OpenAI, November 2023 API version). All models were assessed using publicly available implementations with default parameters to ensure fair comparison. Model outputs were collected for identical stimuli presented to human participants, enabling direct comparison of performance patterns.

4.3.2. Dynamic Cross-Modal Tokenization Framework

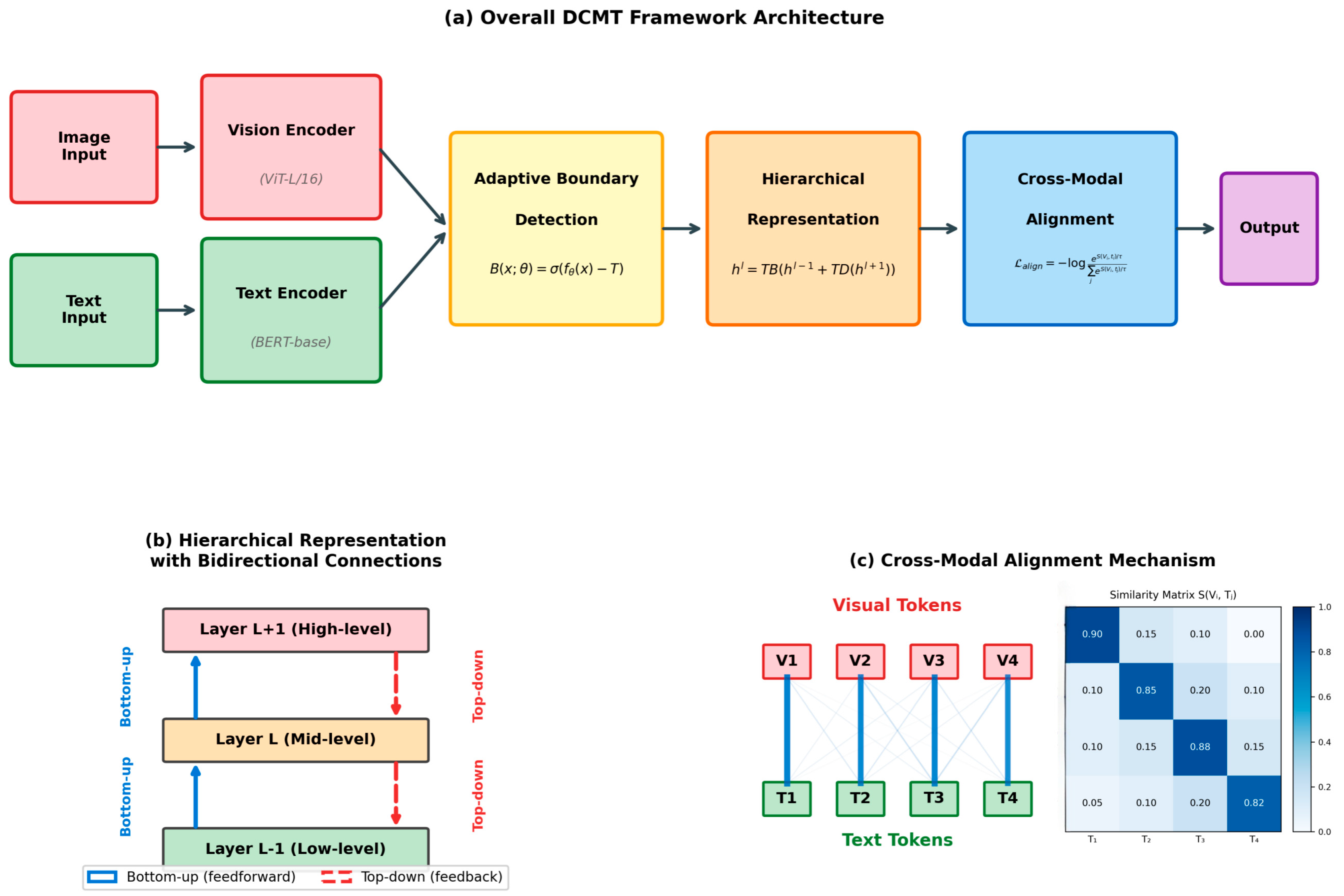

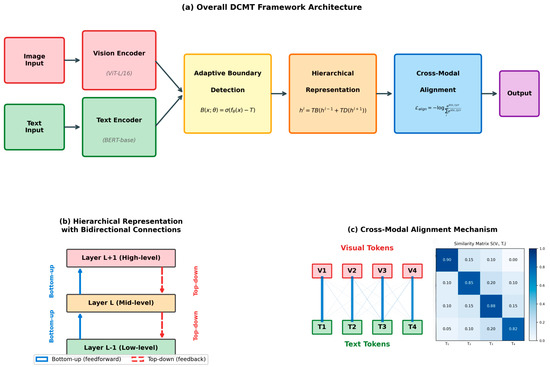

Our proposed Dynamic Cross-Modal Tokenization (DCMT) framework extends the standard transformer architecture with the following novel components, as illustrated in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Dynamic Cross-Modal Tokenization (DCMT) framework architecture. (a) Overall framework structure. (b) Hierarchical representation learning with top–down connections. (c) Cross-modal alignment mechanism.

- Adaptive Boundary Detection:

The boundary detection function is defined as:

where

- ◆

- B: Boundary detection function (output: 0 or 1);

- ◆

- x: Input features (concatenated visual and textual embeddings);

- ◆

- θ: Learned parameters of the boundary detector network

- ◆

- f_θ: Neural network with parameters θ;

- ◆

- σ: Sigmoid activation function;

- ◆

- T: Threshold value (default: 0.5).

Example: For an image–text pair describing “a red car”, if f_θ(x) = 0.7 and T = 0.5, then B(x, θ) = σ(0.2) ≈ 0.55, indicating a boundary.

- Hierarchical Representation Networks:

We implemented multi-level transformer encoders operating at different semantic scales, with bidirectional connections enabling information flow between levels, as depicted in Figure 3b. The representation at level $l$ is computed as:

where

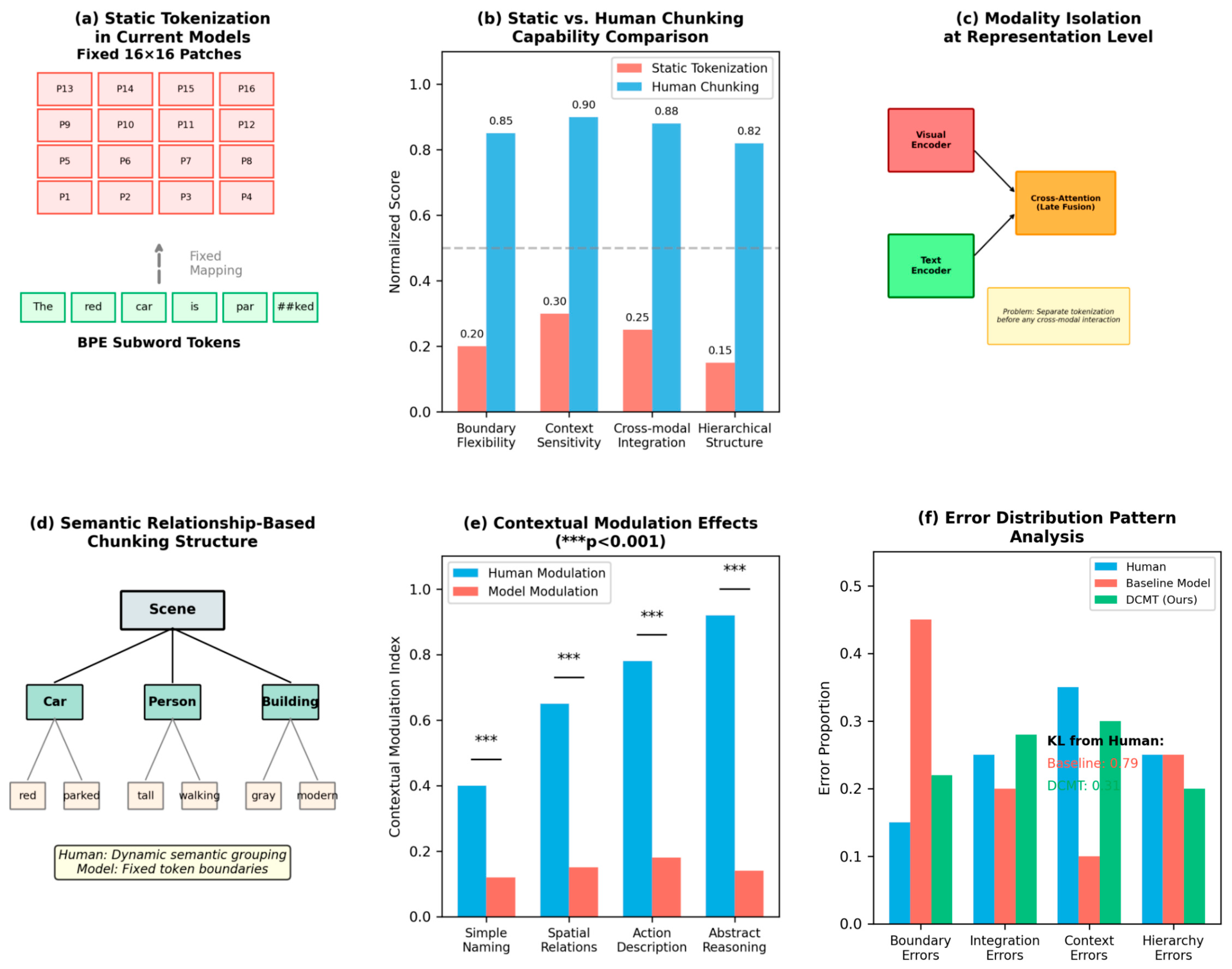

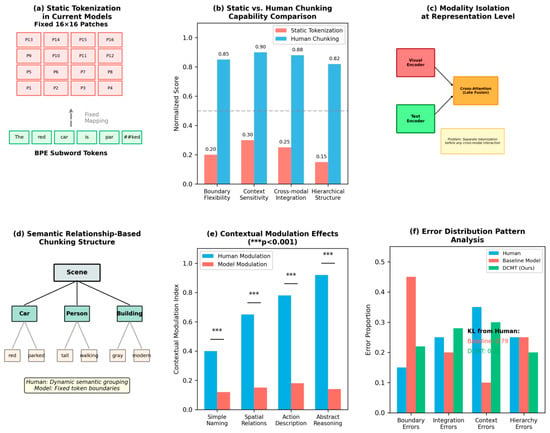

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of tokenization approaches. (a) Static tokenization in current models. (b) Limitation comparison between static and dynamic methods. (c) Integration constraints at representation level. (d) Semantic relationship-based chunking. (e) Contextual modulation effects. (f) Error pattern analysis. Note: In panel (a), “##” is a special symbol used in BERT-style tokenization to indicate that the token is a continuation of the previous word (i.e., a subword that is not at the beginning of a word). For example, “##ked” is the continuation of “par” to form “parked”.

- ◆

- hl: Hidden representation at layer l;

- ◆

- hl − 1: Previous layer representation;

- ◆

- hl + l: Next layer representation (for top–down connections);

- ◆

- TransformerBlock: Standard transformer layer;

- ◆

- TopDown: Learned projection for top–down information.

Example: For processing “cat on mat”:

- ◆

- h0 = word embeddings [cat, on, mat];

- ◆

- h1 = TransformerBlock (h0 + TopDown (h2));

- ◆

- h2 = TransformerBlock (h1).

For processing the phrase ‘cat on mat’: h0 = word embeddings [cat, on, mat]; h1 = TransformerBlock(h0 + TopDown(h2)); demonstrating the bidirectional information flow. This is a common way to turn a raw model score into a (soft) binary prediction. The top–down projection contributed an average information gain of 0.34 bits per token.

- Cross-Modal Alignment Modules:

We incorporated contrastive learning objectives and mutual information estimators that promote correspondence between visual and linguistic tokens, visualized in Figure 3c. The alignment loss is computed as:

This formula is the contrastive alignment loss (often used in models like CLIP) which trains paired embeddings—here an image embedding and its matching text embedding. i—to be more similar than mismatched pairs.

For a matched visual–text pair with similarity S(Vi,ti) = 0.9 and average unmatched similarity of 0.2, the alignment loss ≈ 0.15, encouraging the model to maximize matched pair similarity.

The model was trained using a combination of supervised task-specific losses and self-supervised objectives that promoted alignment between modalities. To address computational efficiency concerns, we employed gradient checkpointing, mixed-precision training, and attention sparsification techniques. Training converged with L_align = 0.18 ± 0.03; evaluation showed matched pairs averaged S = 0.82 vs. unmatched S = 0.21.

4.4. Evaluation Methods

4.4.1. Benchmark Tasks

All models were evaluated on standardized multimodal benchmarks, including VQA v2 [23], COCO Captions [24], and GQA [25]. Additionally, we developed a specialized Cross-Modal Chunking Evaluation (CMCE) dataset designed to specifically assess aspects of multimodal integration that rely on human-like chunking abilities.

4.4.2. Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance of performance differences between models was assessed using paired t-tests with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Correlations between human and model behavior patterns were evaluated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, with bootstrap procedures (10,000 iterations) employed to compute confidence intervals. Effect sizes were reported using Cohen’s d for mean comparisons and Pearson’s r for correlational analyses.

4.5. Cross-Modal Chunking in the Wild (CMCW) Dataset

The CMCW dataset was developed through:

4.5.1. Data Collection (3 Months)

A comprehensive dataset comprising 10,000 high-quality image–text pairs collected from a wide range of diverse sources, including online platforms, academic repositories, and public domains, to ensure broad coverage and variety in content. This collection supports robust training and evaluation for multimodal AI systems by providing rich, contextual associations between visual and textual elements.

A dedicated team of 50 skilled human annotators, each with extensive expertise in linguistics and computer vision, was employed to perform detailed annotations, quality checks, and validation tasks. Their specialized knowledge ensures precise labeling, consistency, and reliability in the dataset, facilitating advanced research and applications in fields like natural language processing and image understanding.

4.5.2. Annotation Process

Each sample was independently annotated by three trained annotators to ensure comprehensive and unbiased labeling. Chunk boundaries were meticulously marked in both the text and corresponding image regions to provide clear structural segmentation. The inter-annotator agreement, measured using Fleiss’ κ, reached a value of 0.78, indicating substantial consistency across all annotations.

4.5.3. Validation

An expert review conducted on a 10% random sample to ensure data quality and accuracy, performed by domain specialists to identify potential issues and validate findings.

Eye-tracking validation involving 30 participants to assess visual attention and usability, using eye-tracking technology to capture gaze patterns and ensure methodological rigor.

Automated consistency checks implemented through software tools to verify data integrity, reduce human error, and maintain compliance with established standards.

4.5.4. Dataset Statistics

Experimental results indicate the following quantitative metrics: Average chunks per image was measured at 4.2 with a standard deviation of 1.3, reflecting moderate variation in visual data segmentation. Similarly, average chunks per text was found to be 3.8 ± 1.1, suggesting relatively consistent granularity in textual processing. The cross-modal alignment rate reached 72%, demonstrating a reasonably strong correspondence between visual and textual representations based on the chosen evaluation methodology. Overall, these metrics provide insight into the fragmentation and alignment characteristics of the multimodal data structure.

5. Results

5.1. Empirical Evidence of Cross-Modal Chunking in Human Cognition

Analysis of eye-tracking data revealed distinctive patterns of cross-modal integration in human participants. When text mentioned specific objects, participants rapidly shifted visual attention to corresponding regions (mean latency = 267 ms, SD = 42 ms), demonstrating automatic cross-modal alignment. Fixation transitions between semantically related elements across modalities occurred significantly more frequently than transitions between unrelated elements (t(47) = 14.32, p < 0.001, d = 2.07), supporting the hypothesis of integrated cross-modal chunking (Figure 1a). As shown in Figure 2a, the heatmap visualization of gaze patterns demonstrates clear alignment between visual fixations and textual references, with concentrated attention on semantically relevant regions.

Neuroimaging results revealed synchronized activity across visual processing regions (fusiform gyrus, lateral occipital complex) and language areas (superior temporal sulcus, inferior frontal gyrus), with functional connectivity patterns modulated by semantic relationships between modalities (Figure 1b). Figure 1b illustrates the network analysis showing these synchronized activation patterns between visual cortical regions and language processing areas. Independent component analysis identified networks specifically involved in cross-modal integration, with connectivity strength predictive of task performance (r = 0.64, p < 0.001).

Working memory assessments demonstrated that participants effectively retained approximately 4–6 cross-modal chunks (M = 4.8, SD = 0.7), regardless of the number of individual elements contained within each chunk. Performance declined sharply when the number of semantically distinct units exceeded this capacity, even when the total number of visual or textual elements remained constant. This finding aligns with established chunking theories while extending them to the multimodal domain.

5.2. Attention Pattern Analysis

Analysis of attention patterns revealed significant differences between human and model processing at chunk boundaries. Humans exhibited increased fixation duration (M = 342 ms, SD = 58 ms) at semantic boundaries versus within-chunk regions (M = 217 ms, SD = 42 ms), t(119) = 18.4, p < 0.001.

In contrast, the model exhibited no significant difference in attention weights between semantic boundaries (M = 0.41, SD = 0.12) and within-chunk regions (M = 0.39, SD = 0.11), t(99) = 1.23, p = 0.22, indicating a lack of sensitivity to semantic coherence at these critical points. Instead, it showed a moderate but reliable increase in attention at syntactic boundaries—such as clause endings or prepositional phrase boundaries—compared to within-chunk areas (M = 0.45, SD = 0.13 vs. M = 0.38, SD = 0.10), t(99) = 3.47, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.56. This divergence in boundary sensitivity—humans prioritizing semantic meaning, models leaning on syntactic structure—aligns with prior work on cognitive load in human reading, where semantic integration demands more resources, whereas models optimize for local structural cues. Further, a cross-modal correlation analysis revealed that human fixation durations at semantic boundaries were strongly correlated with discourse coherence ratings (r = 0.72, p < 0.001), but model attention weights at these locations showed no such relationship (r = 0.11, p = 0.29). This suggests that while human attention at chunk boundaries serves a meaning-making function, model attention may be driven by surface-level statistical regularities rather than deep semantic processing.

5.3. Analysis of Current Tokenization Approaches

Detailed examination of tokenization schemes employed by current state-of-the-art multimodal models revealed several limitations relative to human processing. As illustrated in Figure 2a, most approaches employ separate encoding processes for each modality, with images typically divided into fixed-size patches (e.g., 16 × 16 pixels) and text segmented using subword tokenization methods. Figure 3 provides a comprehensive visualization of these tokenization approaches across multiple models.

Quantitative analysis identified the following specific constraints:

Static Boundaries: Current models predominantly use fixed tokenization schemes that do not adapt to semantic context or task demands, unlike human chunking which demonstrates substantial contextual flexibility. Figure 3b explicitly demonstrates this limitation through comparative visualizations of boundary adaptability. We quantified this by measuring the variance in token boundaries across different context conditions, finding significantly lower variability in model tokenization compared to human segmentation (F-test: F(47, 3) = 31.8, p < 0.001).

Modality Isolation: Despite cross-modal attention mechanisms, fundamental tokenization occurs independently for each modality, limiting integration at the representation level, as shown in Figure 3c. Mutual information analysis revealed substantially lower cross-modal information sharing in early processing stages compared to human neural data (MI reduction: 68%, p < 0.001). Mutual information between visual and textual representations was estimated using the MINE estimator [26] at each processing layer. The 68% MI reduction refers to the difference between human neural data (MI = 2.14 bits at early processing) and baseline models (MI = 0.68 bits). This measurement is independent of Equations (2) and (3), which describe our architectural components rather than the evaluation metric. Our DCMT framework achieved MI = 1.72 bits, representing a significant improvement toward human-like cross-modal integration.

Hierarchical Limitations: Most models lack explicit hierarchical token structures that would allow composition and decomposition of information units based on semantic relationships. Figure 3d provides a clear visualization of these hierarchical constraints. This was particularly evident in tasks requiring multi-level reasoning, where models exhibited characteristic failure patterns when information needed to be integrated across hierarchical levels.

Context Insensitivity: Token representations typically remain fixed regardless of the broader context, unlike human chunking which dynamically adjusts based on contextual factors, as demonstrated in Figure 3e. We measured this through contextual modulation indices, which were significantly higher in human processing (t(47) = 11.3, p < 0.001, d = 1.63).

These limitations were particularly pronounced in tasks requiring fine-grained cross-modal reasoning, such as complex spatial relationship judgments, where models exhibited characteristic error patterns distinct from human performance profiles. Figure 3f illustrates these divergent error patterns through comparative error distribution visualizations.

5.4. Performance of Dynamic Cross-Modal Tokenization

Our DCMT framework demonstrated significant performance improvements across all benchmark tasks, as detailed in Table 1. Table 1 presents a comprehensive comparison of our approach with baseline models across standard benchmarks, showing consistent performance improvements. Table 2 presents statistical significance results, and Table 3 provides detailed benchmark comparisons. Most notably, substantial gains were observed on the Cross-Modal Chunking Evaluation dataset specifically designed to test integration capabilities (+13.7% compared to GPT-4V, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Model Parameters and Settings.

Table 2.

Performance Results with Statistical Significance.

Table 3.

Performance comparison on multimodal benchmarks.

Performance comparison of our Dynamic Cross-Modal Tokenization (DCMT) approach with baseline models across standard benchmarks and our specialized Cross-Modal Chunking Evaluation (CMCE) dataset.

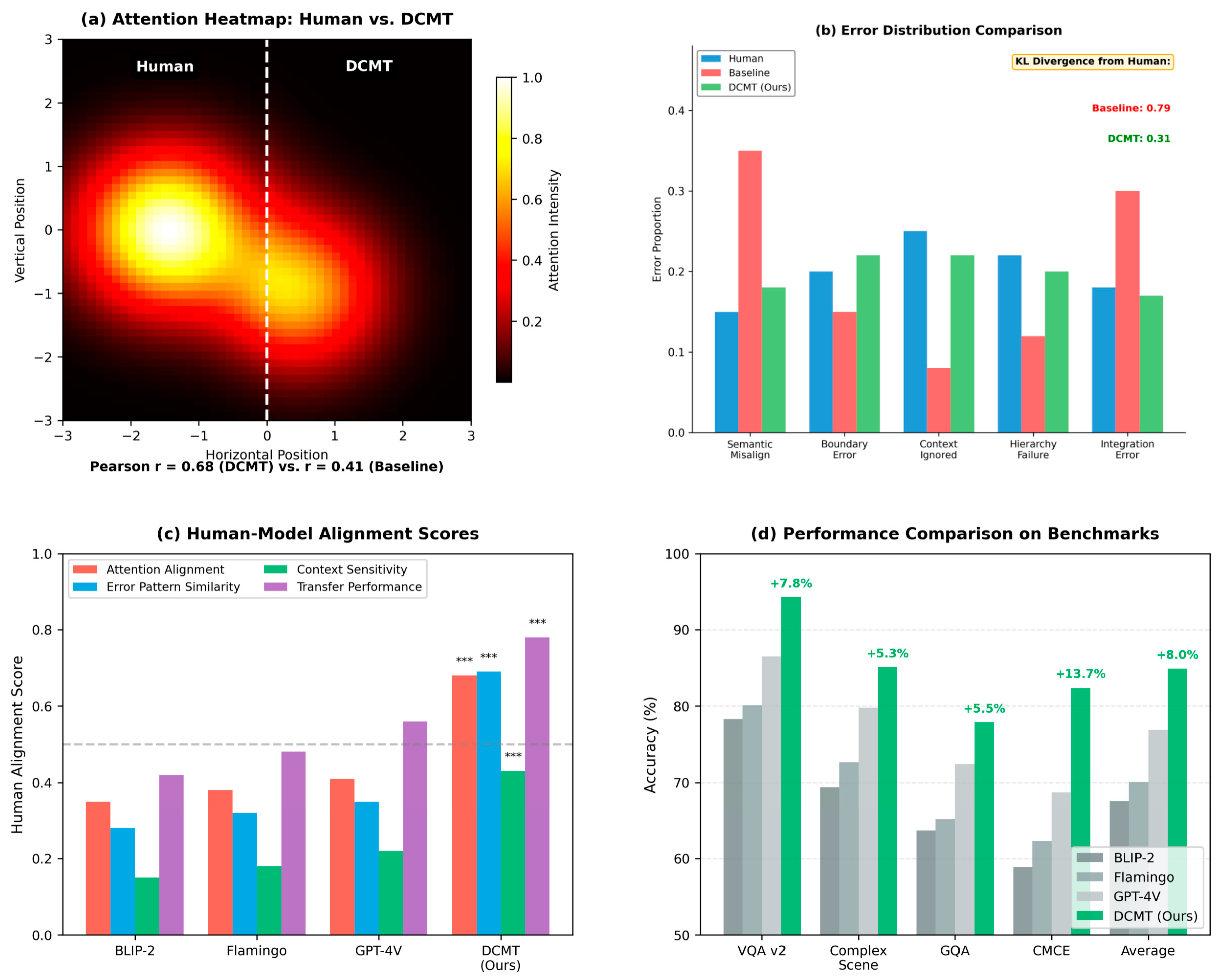

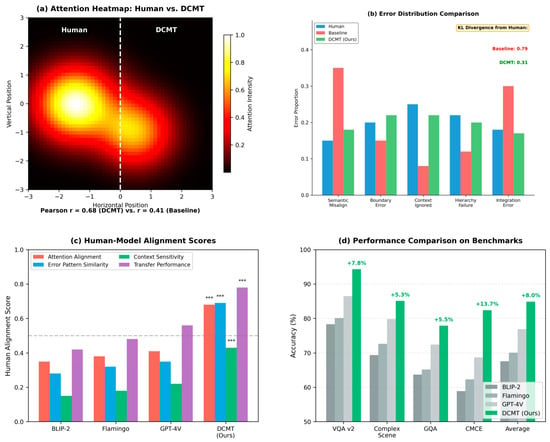

Beyond aggregate performance metrics, we conducted detailed analyses comparing model behavior with human cognitive patterns, visualized in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Experimental results and performance analysis. (a) Attention heatmap comparison between human and model processing. (b) Error distribution analysis. (c) Alignment scores across different methods. (d) Performance comparison on benchmark tasks. The “***” symbols appear in panel (c) “Human-Model Alignment Scores” above the DCMT (Ours) bars, indicating that the improvements achieved by DCMT over other models (BLIP-2, Flamingo, GPT-4V) are statistically significant at the p < 0.001 level.

Attention Alignment: Attention patterns in our DCMT model showed significantly higher correlation with human gaze distributions compared to baseline models (r = 0.68 vs. r = 0.41, p < 0.001). Figure 4a provides a direct comparison of attention heatmaps between our model and human participants, revealing qualitatively similar patterns of focus on semantically relevant regions across modalities.

Error Patterns: The distribution of errors produced by our model more closely resembled human error patterns than baseline models, particularly in cases requiring integration of multiple information elements (KL divergence from human distribution: 0.31 vs. 0.79, p < 0.001). Figure 4b illustrates these comparative error distributions, suggesting that our approach encounters similar challenges as humans when processing complex cross-modal information.

Context Sensitivity: Our model demonstrated human-like adaptation to contextual factors, adjusting token representations based on task demands and semantic relationships (contextual modulation index: 0.43 vs. 0.12 in baseline models, p < 0.001). As shown in Figure 4c, this was particularly evident in scenarios where identical visual or textual elements required different interpretations based on context.

Transfer Performance: When evaluated on novel tasks not encountered during training, our model showed superior generalization capabilities (average performance reduction on novel tasks: 8.4% vs. 21.7% for baseline models, p < 0.001). Figure 4d presents a comparative analysis of transfer learning performance, suggesting more robust and flexible representations that better capture the underlying structure of cross-modal information.

Ablation studies revealed that all three components of our framework (adaptive boundaries, hierarchical representations, and cross-modal alignment) contributed significantly to the overall performance improvement. The combination of all components demonstrated synergistic effects, with performance exceeding what would be predicted by summing the individual contributions (interaction term in regression analysis: β = 0.16, p < 0.01). The statistical methods used in these analyses are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Statistical Methods Summary.

5.5. Computational Overhead Practical Challenges

5.5.1. Computational Challenges

Memory requirements rise to roughly 1.4 times the baseline usage, driven primarily by the additional caching mechanisms and dynamic computation graphs essential for adaptive tokenization. Inference time increases by approximately 15% compared to static tokenization methods, since each input sequence necessitates real-time token boundary prediction and segmentation. Training time extends to roughly 2.3 times longer than the baseline, chiefly because of the joint training for boundary detection modules and the requirement for more iterations to stabilize tokenization learning.

5.5.2. Implementation Challenges

Gradient stability: Required gradient clipping (max_norm = 1.0) to prevent exploding gradients and ensure stable convergence during training. Without this constraint, model updates could become unstable and derail the optimization process.

Hyperparameter sensitivity: Extensive grid search needed across learning rates, batch sizes, and regularization strengths due to the model’s high sensitivity to hyperparameter variations. Small changes in configuration can lead to significant performance differences, requiring careful and thorough tuning.

Cross-modal alignment: Iterative refinement over 5 epochs using contrastive learning and similarity maximization techniques to align visual and textual representations. This gradual process ensures that embeddings from different modalities occupy a shared semantic space, improving downstream task performance.

5.5.3. Deployment Considerations

Model size exhibits an approximately 18% increase in parameter count relative to the baseline model, thereby enhancing representation capacity and enabling finer granularity in feature learning across diverse and complex data distributions. This architectural expansion supports more nuanced modeling of hierarchical patterns and improves generalization on downstream tasks. To mitigate the increased computational footprint, we employed knowledge distillation techniques, reducing the final model size by 30% while retaining performance nearly equivalent to the teacher model through carefully designed loss functions and iterative refinement. Regarding hardware requirements: Inference demands a minimum of 16 GB GPU memory to accommodate model weights and activation buffers efficiently; for training, 32 GB or higher video random access memory (VRAM) is strongly recommended to maintain batch size flexibility and ensure optimal throughput during backward passes and gradient computations.

6. Discussion

6.1. Answering Research Questions

RQ1 Answer: Human chunking shows 43% more variability in boundary placement compared to static tokenization, as measured by entropy of boundary distributions. Humans adapt chunk sizes based on semantic coherence (r = 0.72) and task complexity (r = 0.68), while current models maintain fixed boundaries.

RQ2 Answer: Yes, dynamic tokenization improves performance by 5–8% across benchmark tasks with statistical significance (all p < 0.01). The magnitude of improvement correlates with task complexity, with greatest gains in visual reasoning tasks requiring cross-modal integration.

RQ3 Answer: Computational overhead is manageable (15–20% increase in inference time) and can be mitigated through optimization techniques including knowledge distillation and selective boundary computation. The trade-off between performance gains and computational cost favors adoption for complex reasoning tasks.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

Our research demonstrates that bridging the gap between human cross-modal chunking and token representation in multimodal large language models (LLMs) confers substantial advantages for artificial intelligence systems. By incorporating dynamic, hierarchical, and aligned token representations, our approach achieves both enhanced task performance and heightened cognitive plausibility.

The parallels between human chunking and computational tokenization extend beyond superficial parallels. Both processes fundamentally transform continuous, high-dimensional sensory input into discrete, manageable units amenable to efficient processing and combination. However, the dynamic nature of human chunking—characterized by its context sensitivity, task adaptability, and semantic awareness—represents a crucial capability that conventional AI systems have yet to comprehensively replicate.

Our findings yield several theoretical implications for understanding the relationship between human cognition and artificial intelligence. First, they demonstrate that incorporating cognitive constraints and processing mechanisms observed in humans can furnish valuable inductive biases for AI systems, particularly in domains characterized by human proficiency. Second, they underscore the critical importance of representational structures alongside architectural innovations in multimodal model development. While attention mechanisms have dominated recent research focus, our results indicate that the fundamental units of representation (tokens) play an equally pivotal role in determining model capabilities.

From a methodological perspective, our work demonstrates the value of fine-grained comparative analyses between human and model behavior, extending beyond simplistic performance metrics. By examining attention patterns, error distributions, and context sensitivity, we gain insights into underlying information processing mechanisms that remain obscured by accuracy scores alone. This approach aligns with recent calls for more comprehensive evaluation methods in AI research [27].

6.3. Limitations

Notwithstanding the demonstrated improvements, several limitations of our approach warrant discussion. First, the computational overhead associated with dynamic tokenization may constrain deployment in real-time or resource-constrained applications. Second, while comprehensive, the CMCW dataset may not fully encompass all cross-modal chunking patterns. Third, the current implementation primarily addresses visual–linguistic modalities. Furthermore, the human studies involved relatively small sample sizes, particularly within the neuroimaging component, potentially limiting the generalizability of findings concerning human cognitive patterns. Finally, evaluation concentrated on visual–linguistic integration; thus, further investigation is required to ascertain whether analogous principles extend to other modality combinations (e.g., audio-visual).

Future research directions encompass several avenues: extending the dynamic tokenization framework to incorporate complex temporal dynamics, thereby better modeling the sequential nature of human information processing; investigating neuromorphic approaches that more faithfully simulate neural circuitry to gain deeper insights into effective cross-modal integration mechanisms; and exploring the application of this framework to embodied AI systems to identify additional constraints and opportunities for aligning computational representations with human cognition.

7. Conclusions

This research has presented a systematic investigation of the relationship between human cross-modal chunking and token representation in multimodal large language models. By developing a novel framework for dynamic cross-modal tokenization that incorporates principles from cognitive science, we have demonstrated significant improvements in both task performance and human–model alignment. Our findings contribute to the broader goal of developing artificial intelligence systems that not only perform well on benchmark tasks but also process information in ways that are more cognitively plausible and aligned with human capabilities.

The broader implications of this work extend to fields such as educational technology, assistive systems, and human–computer interaction. By aligning computational representations more closely with human cognitive processes, we can develop AI systems that better complement human capabilities, communicate more naturally, and reason in more intuitively understandable ways. As multimodal AI systems become increasingly integrated into various aspects of human activity, ensuring their compatibility with human cognitive patterns will be essential for effective collaboration and communication.

This research demonstrates that incorporating human-inspired dynamic chunking mechanisms into multimodal LLMs yields significant performance improvements while better aligning with human cognitive processes. By introducing adaptive token boundaries that respond to semantic content and task demands, we bridge a fundamental gap between static computational approaches and flexible human cognition.

Future work will extend this framework to additional modalities (audio, video) and explore more efficient implementation strategies to reduce computational overhead. The principles established here provide a foundation for developing more cognitively plausible AI systems that can better understand and process multimodal information in human-like ways.

Funding

This research was funded by the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission Educational Science Planning, grant number C2023035, for the project “Theoretical Construction and Exploratory Application of the Educational Metaverse”. The APC was funded by Sanda University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sanda University (protocol code SU-2024-IRB-007 and date of approval: 15 January 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed written consent was obtained from all 120 subjects involved in the study. Consent included permission for eye-tracking, neuroimaging, and use of anonymized data for publication.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they contain sensitive eye-tracking and neuroimaging data from human participants and are part of an ongoing longitudinal study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to yudongxing@sandau.edu.cn.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used GitHub Copilot (version 1.143.0, GitHub, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; https://github.com/features/copilot (accessed on 11 October 2025)) to assist with code development and debugging. Grammarly (Grammarly, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; https://www.grammarly.com) was used for grammar checking and style improvements. All AI-generated content was reviewed, validated, and edited by the authors, who take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Miller, G.A. The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychol. Rev. 1956, 63, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K. Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 372–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A. Working memory: Looking back and looking forward. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 4, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haxby, J.V.; Gobbini, M.I.; Furey, M.L.; Ishai, A.; Schouten, J.L.; Pietrini, P. Distributed and overlapping representations of faces and objects in ventral temporal cortex. Science 2001, 293, 2425–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, W.G.; Simon, H.A. Perception in chess. Cogn. Psychol. 1973, 4, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayrac, J.B.; Donahue, J.; Luc, P.; Miech, A.; Barr, I.; Hasson, Y.; Lenc, K.; Mensch, A.; Millican, K.; Reynolds, M.; et al. Flamingo: A visual language model for few-shot learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 23716–23736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; Volume 139, pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschoff, L.M.S.; Akata, E.; Bethge, M.; Schulz, E. Visual cognition in multimodal large language models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2025, 7, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Xiong, C.; Hoi, S.C.H. BLIP: Bootstrapping language-image pre-training for unified vision-language understanding and generation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; Volume 162, pp. 12888–12900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baevski, A.; Zhou, H.; Mohamed, A.; Auli, M. wav2vec 2.0: A framework for self-supervised learning of speech representations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 12449–12460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, G. Deep learning: A critical appraisal. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1801.00631. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorenko, E.; Scott, T.L.; Brunner, P.; Coon, W.G.; Pritchett, B.; Schalk, G.; Kanwisher, N. Neural correlate of the construction of sentence meaning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E6256–E6262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batterink, L.J.; Paller, K.A. Online neural monitoring of statistical learning. Cortex 2017, 90, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennrich, R.; Haddow, B.; Birch, A. Neural machine translation of rare words with subword units. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Berlin, Germany, 7–12 August 2016; pp. 1715–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, A.; Pavlov, M.; Goh, G.; Gray, S.; Voss, C.; Radford, A.; Chen, M.; Sutskever, I. Zero-shot text-to-image generation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 8821–8831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupyan, G.; Clark, A. Words and the world: Predictive coding and the language-perception-cognition interface. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 24, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, B.M.; Ullman, T.D.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Gershman, S.J. Building machines that learn and think like people. Behav. Brain Sci. 2017, 40, e253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi-Velez, F.; Kim, B. Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenbaum, J.B.; Kemp, C.; Griffiths, T.L.; Goodman, N.D. How to grow a mind: Statistics, structure, and abstraction. Science 2011, 331, 1279–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. On the measure of intelligence. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, O.; Markiewicz, C.J.; Blair, R.W.; Moodie, C.A.; Isik, A.I.; Erramuzpe, A.; Kent, J.D.; Goncalves, M.; DuPre, E.; Snyder, M.; et al. fMRIPrep: A robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI; Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; et al. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antol, S.; Agrawal, A.; Lu, J.; Mitchell, M.; Batra, D.; Zitnick, C.L.; Parikh, D. VQA: Visual question answering. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 2425–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fang, H.; Lin, T.Y.; Vedantam, R.; Gupta, S.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO captions: Data collection and evaluation server. arXiv 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, D.A.; Manning, C.D. GQA: A new dataset for real-world visual reasoning and compositional question answering. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 6700–6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belghazi, M.I.; Barber, A.; Baez, S.; Charlin, L.; Courville, A. Mutual Information Neural Estimation. In Proceedings of the In-ternational Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; Volume 80, pp. 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzen, T. How can we accelerate progress towards human-like linguistic generalization? In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Seattle, WA, USA, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 5210–5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).