Abstract

A few countries have requested open IP locations of posters in order to combat rumors and strengthen management. Such policies intensify information surveillance of users, which may in turn influence their online behavior. In the context of multiple governments considering the implementation of this policy, it is essential to assess its impact. We examine the impact of IP location openness on posters’ behavior and patterns based on the empirical data of Sina Weibo, and analyze the heterogeneous impact on users of different genders. Regression discontinuity and short-run panel data regression results show that IP location openness reduces the frequency of users’ social media participation behavior; specifically, the frequency of reposting microblogs and posting geo-tagged microblogs is remarkably diminished, while the frequency of posting photos is not discernibly changed. Long-run panel data regression results indicate that the overall inhibitory effect on the frequency of social media participation behavior disappears, and it only has a negative effect on posting geo-tagged microblogs. The results of heterogeneity analysis suggest that the short-run negative impact of IP location openness on female users’ social media participation behavior is more remarkable than that of male users.

1. Introduction

The Regulations on the Management of Internet User Account Information, issued on 27 June 2022, propose that the Internet platform should prominently display the IP location information of the account on the Internet user account information page. All social media platforms in China have implemented the user location display function based on IP. Prior to this, the feature was first added by Weibo on 4 March 2022, to combat misinformation about the Russia–Ukraine crisis. Immediately after, Douyin, Xiaohongshu, Kuaishou, Zhihu, and other major platforms have also issued notices stating that they will open IP location functions. The reasons for displaying users’ IP locations vary among these platforms and mainly include maintaining a good communication order and combating rumor-spreading behavior. Currently, some countries require social media platforms to track and report IP location to some extent. For example, the Indian government is gradually implementing regulations on the IP location of platforms that provide illegal information, with the aim of curbing the spread of rumors. It can be seen that disclosing IP location may be adopted by other countries under specific circumstances. However, does this policy really affect posting? Currently, there is a lack of research into its policy impact. Drawing on the perspective of privacy cynicism, we examine whether IP location openness affects users’ posting behaviors.

The literature relevant to the IP location openness primarily focuses on two key areas. First, we consider the factors influencing social platform users’ location disclosure behavior. Numerous empirical studies have explored this topic; for example, the work of Chen [1], through questionnaires, found that perceived benefits positively impact users’ disclosure of location information, while privacy risks have a negative impact. Kim [2] found that users who had disclosed geo-tagged posts were more likely to repeat such behavior than other users. Wang [3] found that Facebook users’ “check-in” behavior is closely related to their characteristics, and users with a tendency to show off have a higher frequency of “check-in” behavior. Further, Sun [4] analyzed the heterogeneous impact of gender on address disclosure behavior and found that the impact of utilitarian benefits on men is more significant than that on women, while the impact of privacy risks on women’s disclosure intentions is more significant than that of men. Second, we examine the influence of information surveillance on social media participation behavior. People who are aware of surveillance behavior tend to be more cautious, discreet, and less willing to express their opinions [5]. When online users perceive surveillance, a chilling effect may occur and users may be reluctant to express their opinions on social media. Perceived surveillance has a significant negative impact on the willingness of Turkish social media users to express their views [6].

After the full openness of IP location, Sina Weibo users will have their homepages automatically updated with province (country) information according to where they update their newest post, and as a result, users lose spatial anonymity. On the one hand, a fully open IP address strengthens information surveillance on the user, with infringement of spatial anonymity. Information surveillance affects the information privacy boundary. Cavusoglu [7] studied the impact of privacy policy changes on Facebook users’ willingness to disclose information and found that giving users more privacy control rights could cause them to increase the amount of publicly shared content. On the other hand, the full openness of IP location will cause users to worry about privacy [8], such as revealing their traces, being inferred by people with ulterior motives, and exposing their identities [9], thus leading to “privacy turmoil”. According to the communication privacy management theory, “privacy turbulence” will prompt users to re-establish privacy rules in accordance with their privacy protection needs [10], such as reducing the number of posts. Previous studies have found that users with higher privacy concerns are less likely to disclose personal information and are less willing to use location-based services than other users [11,12,13].

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Media Participation and Location Disclosure

The social media participation behavior of online social network (OSN) users is their voluntary and purposeful self-presentation to other users. The information disclosed includes demographic information (gender, date of birth, education level, etc.), personal photos, personal interests, feelings, etc. [14,15]. The above information, undoubtedly, has high commercial value. OSNs explore users’ preferences through big data, artificial intelligence, and other technologies, to provide more targeted marketing strategies and drive business model innovations [16]. Therefore, it is of great significance for the sustainable development of OSN platforms to understand the dynamic process of users’ participation decisions.

“Check in” to specific locations is one of the essential functions of social platforms, which plays a vital role in improving the service level and marketing income of social platforms. For users, they can mark their footprints and upload location-related pictures or descriptions to share their feelings about the trip and activity with friends, and the percentage of female users utilizing location check-in is substantially higher than that of male users [17]. Correspondingly, users can also obtain valuable information by searching for geographical locations to drive interactive dissemination of information, although some geographical location information does not play a significant role. For example, the consistency between the user’s long-term residence and the poster’s IP location is not important for users to judge the credibility of information [18]. In addition, some platforms are connected with external maps, which can help users navigate to places of interest and enhance users’ sense of social platform experience [1]. For social platforms, geolocation information disclosed by users expands the potential for personalized services and marketing. For example, by collecting and processing users’ positioning information, social platforms can infer users’ characteristics (such as educational background, age, race), home address, activity scope, social relations, etc. [19], which helps improve their marketing strategies and enhance the targeting of advertisements.

Sina Weibo, one of the top ten OSN sites worldwide in terms of monthly active users, took the lead in launching the policy of mandatory IP location openness on 28 April 2022. Firstly, users were informed about the feature, but their consent was not obtained at the time of its launch. Secondly, the user cannot turn it off voluntarily; hence, users lose the right to control and make independent decisions on IP location information. This mandatory and non-consensual IP location openness substantially changes the way location information is disclosed on Weibo and provides a unique context to examine how users adjust their social media participation under strengthened information surveillance.

2.2. Information Surveillance, Privacy Cynicism, and Chilling Effects

2.2.1. Information Surveillance and Dataveillance

Information surveillance on social media refers to the monitoring and tracking of users’ online activities by platforms, often through data collection, algorithmic profiling, and the public display of certain personal attributes (e.g., IP location). Dataveillance extends this notion to the large-scale, continuous monitoring of users through digital traces [20]. When users become aware that their online behavior may be monitored in this way, they may engage in self-censorship and adjust their expression patterns. Building on this idea, Kappeler [21] introduced the concept of “dataveillance imaginaries”, arguing that users’ perceptions and imaginaries of being surveilled can lead to chilling effects, whereby individuals refrain from certain forms of speech or participation to avoid potential risks.

2.2.2. Privacy Cynicism and the Privacy Paradox

Hoffmann [22] first introduced the concept of privacy cynicism, defining it as a cognitive coping mechanism that deals with the uncertainty, powerlessness, and mistrust regarding how online services handle personal data, thereby undermining individuals’ privacy-protecting behaviors subjectively. In the same year, Hargittai and Marwick [23] found that when young people realize that their privacy may be violated and they are powerless to act, they exhibit a submissive pragmatism, accompanied by feelings of apathy and disillusionment—emotions associated with privacy cynicism.

Consistent with this research, the present study views privacy cynicism as a maladaptive coping style involving psychological detachment, disillusionment, and indifference, and as a self-protective reaction adopted by Internet users facing privacy threats [24,25]. Individuals with strong privacy cynicism sentiments may believe that there is no effective way to control personal information on the Internet and therefore are less likely to actively manage their data [25]. Privacy cynicism has been proposed as an important mechanism underlying the “privacy paradox”, whereby individuals simultaneously express high privacy concerns yet continue to use privacy-invasive online services [24].

2.2.3. Surveillance, Privacy Cynicism, and Social Media Participation

The impact of information surveillance on social media participation varies according to individual perceptions of monitoring and their coping strategies. The individual differences–surveillance perception–message response framework suggests that users’ responses to surveillance depend on their privacy-related dispositions, including privacy cynicism [20,26]. Privacy cynicism, as a cognitive coping mechanism, may enable individuals to overcome or ignore certain privacy concerns and rationalize their continued use of privacy-invasive online services [25]. This trait is typically associated with distrust of data collectors, feelings of privacy vulnerability, and a sense of powerlessness in online contexts [10].

Existing research has primarily examined how privacy cynicism and related privacy concerns influence users’ disclosure decisions on social platforms, focusing on attitudes, intentions, and self-reported behaviors. Prior studies have shown that social media participation can be assessed through various forms of interaction between an organization and its users, such as likes, shares, and comments, each of which can be considered a direct expression of users’ participation [27]. Sharing, including posting and reposting, is a particularly important form of participation [28]. Social media participation is affected by content factors [29], social factors [30], and platform factors [31]. However, relatively few studies have directly assessed changes in users’ actual social media participation behaviors under the influence of platform monitoring policies and long-term versus short-term surveillance. In particular, the consequences of mandatory IP location disclosure as a specific form of intensified information surveillance remain underexplored.

2.3. Empirical Evidence on IP Location Openness and Geo-Tagging Policies

Recent studies have significantly advanced our understanding of the impacts of IP location openness and geo-tagging policies. Kappeler [21] proposed the notion of “dataveillance imaginaries”, suggesting that awareness of being monitored can induce self-censorship and chilling effects in online communication. In the context of Chinese social media, Liu [8] conducted qualitative interviews with Weibo users and found that users generally perceive the “costs” of IP location openness to outweigh its “benefits”. As a result, they tend to reduce self-disclosure and adopt various privacy management strategies. Using a natural experiment design, Guo [32] exploited Weibo’s IP tagging policy and discovered that location openness increased the use of geographically inappropriate language in comments, indicating that location tags can amplify group identities and escalate conflicts. Li [33] examined the geographic tagging policy and found that while it increased topic engagement, it reduced the emotional tone of posts, implying that IP location disclosure not only changes the volume of posts but also reshapes how information spreads on social media. Yang and Xu [34] further showed that Weibo’s location disclosure policy did not significantly suppress overseas users, but it decreased the volume of comments from domestic users on cross-provincial issues, particularly critical speech, thereby providing additional evidence for chilling effects in highly surveilled online environments.

Taken together, these studies demonstrate that IP location openness and geo-tagging policies can reshape online expression, language use, and conflict dynamics. However, they pay relatively less attention to the dynamic adjustment of different forms of social media participation (e.g., posting, reposting, and geo-tagging) and to potential gender heterogeneity in behavioral responses to IP location policies.

2.4. Research Gaps

So, there are several research gaps to be filled. Firstly, existing studies have explored the decision-making process of users’ social media participation behavior from different perspectives, such as user personality, the balance between perceived benefits and perceived risks, etc. However, most studies have relied on questionnaires to gather data on users’ psychological cognition and intention expression, which may not accurately reflect their behavior change process [35]. Moreover, there might be a discrepancy between users’ social media participation intention and their actual behavior, known as the “privacy paradox” phenomenon. Therefore, this study focuses on analyzing users’ social media participation behavior in specific situations, using quasi-natural experiments and actual behavioral data, such as the dynamic changes in different types of microblogs posted by users. Secondly, while previous studies have shown that weakening users’ information surveillance can significantly promote their intention to participate in social media, the effect of heightened information surveillance on social media participation behavior requires further exploration.

Thirdly, gender is one of the most widely discussed individual characteristics in studies of information disclosure and privacy concerns [36,37,38], yet its role in shaping users’ actual participation behaviors on OSNs under intensified information surveillance remains underexplored. Prior work has largely concentrated on gender differences in disclosure intentions, privacy attitudes, or perceived risks, rather than on gendered behavioral responses to platform-level policy changes, such as mandatory IP location openness.

By leveraging a quasi-natural experiment created by Sina Weibo’s full openness of IP location and utilizing large-scale behavioral data, this study addresses these gaps by (1) tracing dynamic changes in different forms of social media participation, (2) distinguishing between short-run and long-run effects of heightened information surveillance, and (3) uncovering the heterogeneous impact of IP location openness on male and female users.

2.5. Hypotheses Development

2.5.1. Perceived Surveillance and the Chilling Effect

Surveillance theory posits that when individuals perceive that their actions are being monitored or can be easily attributed to their real-world identity, they tend to engage in self-censorship and reduce expressive behaviors [22,25]. Even subtle cues of observation—such as real-name prompts or identity-linked features—can trigger psychological discomfort and suppress participation in public communication.

The mandatory IP location openness policy heightens the visibility and traceability of users’ posts by publicly linking them to users’ geographic origin. This linkage increases concerns about social judgment, profiling, and potential offline consequences, thereby raising perceived surveillance. When individuals feel more exposed to monitoring, they tend to withdraw from public expression and reduce content production on social media.

Accordingly, we expect overall posting activity to decrease after the implementation of mandatory IP location openness.

H1.

IP location openness casts a negative impact on the frequency of social media participation behaviors.

2.5.2. Privacy Risk, Identifiability, and Identity-Revealing Behaviors

Users strategically manage self-disclosure online by evaluating the trade-off between benefits and privacy risks [39]. Privacy risk increases when content contains identifiable personal elements—such as photos showing one’s face, home environment, or companions—or precise location markers that disclose mobility patterns. Prior studies show that individuals restrict such identity-revealing behaviors when they perceive elevated risks of stalking, profiling, or misuse of personal information [40].

Mandatory IP location openness raises the baseline identifiability of all posts by automatically exposing users’ geographic region. Combining a visible IP location with identity-revealing content (e.g., photos or geo-tags) creates stronger links between online and offline identities, making users more identifiable and increasing potential privacy and safety risks. People therefore respond not by uniformly reducing all activity but by selectively avoiding content that heightens exposure [41].

Thus, users are likely to reduce identity-revealing behaviors more sharply than general posting.

H2.

Mandatory IP location openness leads to a larger reduction in identity-revealing behaviors, such as posting photos and geo-tagged microblogs.

2.5.3. Gendered Privacy Concerns and Differential Vulnerability

The extensive literature documents that women face greater risks of online harassment, doxxing, and targeted hostility than men [42]. As a result, women tend to adopt more conservative disclosure strategies and express stronger concerns about digital traceability [43]. When platforms introduce policies that increase identifiability—such as real-name verification or location exposure—women often react more strongly due to heightened perceived vulnerability and the desire for self-protection.

Mandatory IP location openness, by associating each post with a publicly visible geographic identifier, may disproportionately heighten safety concerns among female users. This is particularly relevant in contexts where regional identity carries social, cultural, or political implications.

Therefore, the behavioral response to the policy is expected to be stronger among women.

H3.

The negative effect of mandatory IP location openness on posting behavior is stronger for female users.

3. Materials and Methods

This study adopts an analytical framework that builds upon Cavusoglu [7], who examined how Facebook’s introduction of granular privacy controls affected user content sharing and disclosure patterns. Their quasi-experimental design using exogenous privacy policy changes provides a robust methodological foundation for analyzing how platform transparency policies influence user behavior. While Cavusoglu [7] focused on privacy control enhancements, our research extends this framework to examine the opposite scenario—increased transparency through IP location disclosure—thereby contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of privacy–transparency trade-offs in social media platforms.

3.1. Research Design

We exploit Sina Weibo’s introduction of a full openness in IP location display on 28 April 2022 as a quasi-natural experiment. Before this date, users’ IP locations were not shown on their profiles or under each post; afterwards, the platform automatically displays the province (or country) from which the latest post is made, and users cannot opt out of this feature. This exogenous platform-level policy change allows us to study how enhanced information surveillance affects users’ social media participation. We focus on the short-term and longer-term dynamic effects of the policy on different types of posting behaviors, and on the heterogeneous effects by gender. To do so, we first estimate a time-based sharp regression discontinuity design (RDD) around the policy introduction date, and then estimate panel regression models for the short-run and long-run periods.

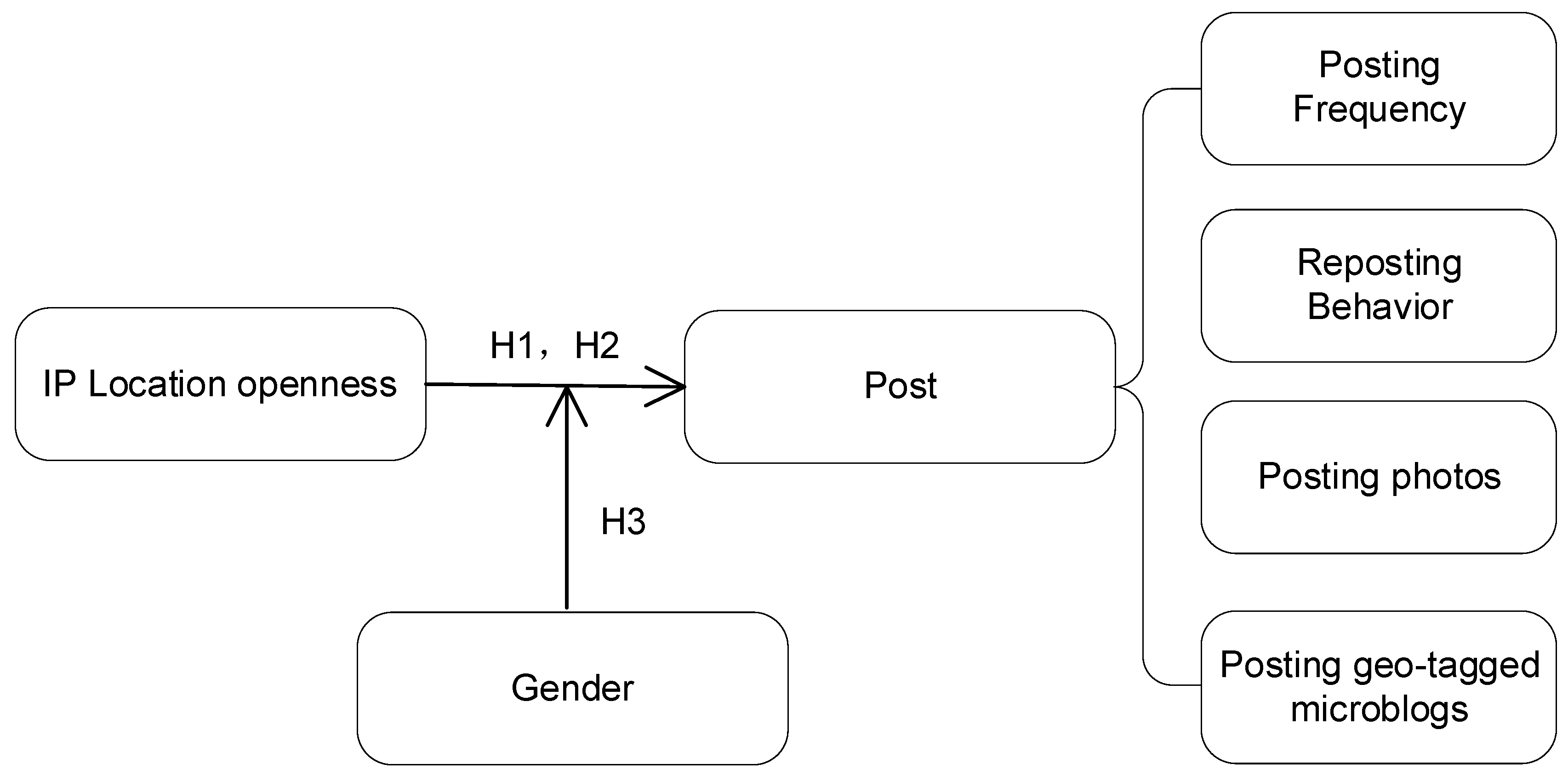

Figure 1 summarizes the theoretical framework of this study. IP location openness changes users’ social media participation behaviors, including posting microblogs, reposting microblogs, posting photos, and posting geo-tagged microblogs. The arrow labeled H1 represents the direct negative effect of IP location openness on users’ posting behavior, predicting that mandatory location disclosure reduces overall social media participation frequency. The arrow labeled H2 indicates the differential impact across behavior types, suggesting that identity-revealing behaviors (such as posting photos and geotagged microblogs) experience a larger reduction than general posting behaviors. The arrow labeled H3 depicts the heterogeneous effect, specifically hypothesizing that female users experience a stronger negative response to IP location openness compared to male users, particularly in the short term.Together, these arrows capture both the main effect (H1), the moderating mechanism (H2), and the differential impact across gender groups (H3) Drawing on the literature synthesized in Section 2.5 “Hypotheses Development”, we formulated three hypotheses (H1–H3). H1 posits that strengthening information surveillance through mandatory IP location openness reduces the overall frequency of users’ social media participation behaviors. H2 posits that the negative effect is stronger for identity-revealing behaviors such as photo posting and geo-tagging than for general posting. H3 posits that this negative effect is stronger for female users than for male users. To test H1, we estimate three types of models on the full sample: a time-based regression discontinuity design (RDD, Model 1), a short-run fixed-effects panel model (Model 2), and a long-run two-way fixed-effects panel model (Model 3). To test H2, we compare the policy impact across different forms of participation, with particular attention to identity-revealing behaviors (posting photos and geo-tagged microblogs) relative to general posting and reposting. To test H3, we re-estimate the panel models separately for male and female users and compare the estimated effects across gender groups.

Figure 1.

The mechanism of IP location openness on post behavior.

While H2 emphasizes stronger negative effects on identity-revealing behaviors (photo posting and geo-tagging), our empirical results suggest that this pattern holds more consistently for geo-tagged microblogs than for photo posts, especially in the long run.

3.2. Data Sources

Web scraping was carried out from 1 August to 14 August 2022. Considering that some users may set the public visibility time range as ‘within half a year’, the time range chosen to crawl is 8 weeks before and after the launch of the new function (i.e., 28 February to 26 June 2022; the week of 28 April is not counted). The specific process of obtaining and screening Sina Weibo users is as follows.

Use the Octopus Collector to capture random users and the basic information on their homepage, and obtain 11,290 Weibo accounts in total.

Remove inactive users through the following screening criteria: the account registration time should predate 28 February 2022 by at least one year; since registration, more than 100 microblogs should have been posted; and at least one microblog should have been posted between 28 February and 26 June 2022. Additionally, remove officially certified accounts, professional bloggers, and organization-operating accounts, leaving 5705 accounts.

Apply Python 3.9.x software to collect the text content, time, location and other information of microblogs posted by sample users from 28 February to 26 June 2022, screen out those who have not posted microblogs within 8 weeks before the full opening of IP location, and manually check the Weibo text content to ensure that the samples do not contain users who spread rumors. When it comes to Weibo accounts managed by professional organizations, it is important to note that the operator and the owner of the account may be different people located in different places. As such, the data provided by such accounts cannot accurately reveal the true response of the account owner to the full openness of IP location. To eliminate any confusion, officially certified or influential users, which include interest-certified, self-media-certified, and Weibo officially certified accounts, are not taken into consideration. Finally, obtain 2007 samples (see Table 1). The characteristics of the sample users are consistent with those of Weibo users overall. We have compared the demographics of the selected users with those in the 2020 Weibo Users Development Report and found them to be consistent, indicating that the samples have good representativeness.

Table 1.

Sample users’ features.

3.3. Variable Selection

Based on the web crawling process described above, we obtain the following two types of user-level data: (i) the users’ basic information data (nickname, gender, number of users they followed, number of followers, total number of microblogs, profile, address, IP location, birthday, registration time, etc.); and (ii) the user’s historical microblog data (text content and photo content of posted microblogs, location when posting microblogs, etc.).

Microblogging is the main service provided by the Sina Weibo platform. Thus, dynamic activities such as posting microblogs, reposting microblogs, and sharing photos and locations are concrete manifestations of social media participation behaviors. Social media participation is determined by the level of interaction of users on social networks and the total series of interactions (likes, shares, and comments), and it relates it to the number of posts they make and retweets. Based on the public microblog data captured by web crawler software, this paper uses the quantity of posted microblogs to measure the frequency of social media participation behavior and further subdivides microblogging into three categories: reposting microblogs, posting photos, and posting geo-tagged microblogs. To be specific, posting microblogs includes posting all types of microblogs, reposted and original, and original microblogs include photos as well as geo-tagged microblogs.

To test H2, we distinguish between general participation behaviors and identity-revealing behaviors. General participation is captured by the number of microblogs posted (including original posts and reposts) and the number of reposted microblogs. Identity-revealing behaviors are proxied by posting photos and posting geo-tagged microblogs. Photo posts often contain visual cues about users’ faces, social circles, or living environments, whereas geo-tagged microblogs directly disclose users’ real-time locations and mobility patterns. Comparing the policy impact across these behavior types allows us to assess whether mandatory IP location disclosure suppresses identity-revealing behaviors more strongly than general posting activity.

3.4. Model Settings

This study identifies the causal effect of the IP location disclosure policy using a time-based regression discontinuity design (RDD). The abrupt and platform-wide rollout of the policy provides an exogenous shock, enabling credible comparison of user behaviors immediately before and after implementation. To capture behavioral adjustments beyond the cutoff, we further estimate panel data regressions (PDRs). A user fixed-effects model is applied to the short-run window (±3 weeks), while a two-way fixed-effects model is used for the long-run window (±8 weeks) to account for both individual heterogeneity and time-specific shocks.

For robustness, we conduct placebo cutoff tests and bandwidth sensitivity checks for the RDD, and re-estimate the PDR models using alternative sample windows and sample sizes. Standard errors are clustered at the weekly level for RDD and at the user level for panel regressions to correct for within-user correlation caused by repeated observations over time.

3.4.1. Regression Discontinuity Design

Following the works of Cavusoglu [7], we estimate the standard parametric RDD equations of the form.

The RDD model in this paper is shown in Formula (1):

In Formula (1), is the relevant outcome variable of the unobserved effects, including posting microblogs, reposting microblogs, posting photos, and posting geo-tagged microblogs. is a dummy variable equal to 1 if falls after the introduction of the new function (28 April 2022), and 0 otherwise. is the index coefficient after the function change, which mainly reflects the discontinuity effect size of the outcome variable after the launch of the new function. indicates the time period, where the time period is the number of weeks relative to the 9th week (cutoff week). indicates the time (week) when user i registers a Sina Weibo account in . is the total number of microblogs posted by user i since registration. is a dummy variable representing the gender of the user i: 1 if male and 0 otherwise.

3.4.2. Short-Run Panel Fixed-Effects Model

To determine if the new function immediately and directly affects users’ social media participation behaviors and patterns, we conduct a short-term PDR analysis. Considering that the optimal bandwidth of the regression discontinuity report is 3 (weeks), we select 3 weeks before and after the launch of the new function as the short-run time window, and establish the econometric model shown in Equation (2) for short-run fixed-effects regression:

In Equation (2), represents the users’ social media participation behavior in , specifically including posting microblogs, reposting microblogs, posting photos, and posting geo-tagged microblogs; and have the same meaning as in Formula (1).

3.4.3. Long-Run Two-Way Fixed-Effects Model

To assess longer-term dynamics, we extend the time window to eight weeks before and after the policy and estimate a two-way fixed-effects model:

In Equation (3), represents the users’ social media participation behavior in , specifically including posting microblogs, reposting microblogs, posting photos, and posting geo-tagged microblogs; has the same meaning as in Formula (1). We adopt the time window of 8 weeks before and after the launch of the new function to represent the long-run.

3.4.4. Extension: Interaction with Regional Information and Clustered Errors

In an extension, we explore whether the effect of the policy depends on whether posts contain explicit regional information. We estimate the following interaction model:

Here, is the user’s social media participation behavior in (e.g., posting, reposting, photo sharing, geo-tagging), and the other variables retain the same meaning as in Equation (1). is a binary indicator variable denoting whether a post includes geographical data (such as location tags). The interaction term assesses whether the policy’s impact varies when regional information is disclosed.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

We summarize the data generated by each user on a weekly basis, taking 28 February 2022 to 6 March 2022 as the first week, while the new function was launched on 28 April 2022 (the ninth week). Table 1 shows the key features of the sample users obtained by Python crawling. Of the total sample users, 76% were female, and 71% had been registered for more than five years. Additionally, 1332 users provided their address information, and 731 of them accurately revealed their addresses up to the prefecture-level cities. By comparing with IP locations, we found that 835 sample users’ IP location information is consistent with their filled address information.

We performed a descriptive statistical analysis on four social media participation behaviors during two periods—before and after the full openness of IP location. Table 2 summarizes our findings. On average, the number of microblogs posted, microblogs reposted, and photos posted all slightly increased after the new function was launched. The standard deviation of the number of posted photos was the smallest, implying that there were no significant fluctuations before or after the change. In contrast, the average value of posted geo-tagged microblogs dropped slightly after the full openness of IP location. However, due to the rough calculation indicators and methods and a lack of regression analysis, we cannot conclude any notable causal relationship between the full openness of IP location and social media participation behavior.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistical analysis.

4.2. Regression Discontinuity Analysis

RDD models are generally divided into two types: sharp RDD and fuzzy RDD. The full openness of the IP location studied in this paper fully covers the research samples, so sharp RDD is suitable to be applied. This study aims to examine the impact of the new function after it was launched; thus, it is appropriate to use time (week) as the driving variable, and the launch week (week 9) is the cutoff point. Taking the social media participation-related data before the launch of the new function (i.e., the pre-processing observation results) as a reference group, if the disclosure patterns after the launch of the new function are different from those before the cutoff, then we can assume that the full openness of IP location has a real impact on users’ social media participation behavior.

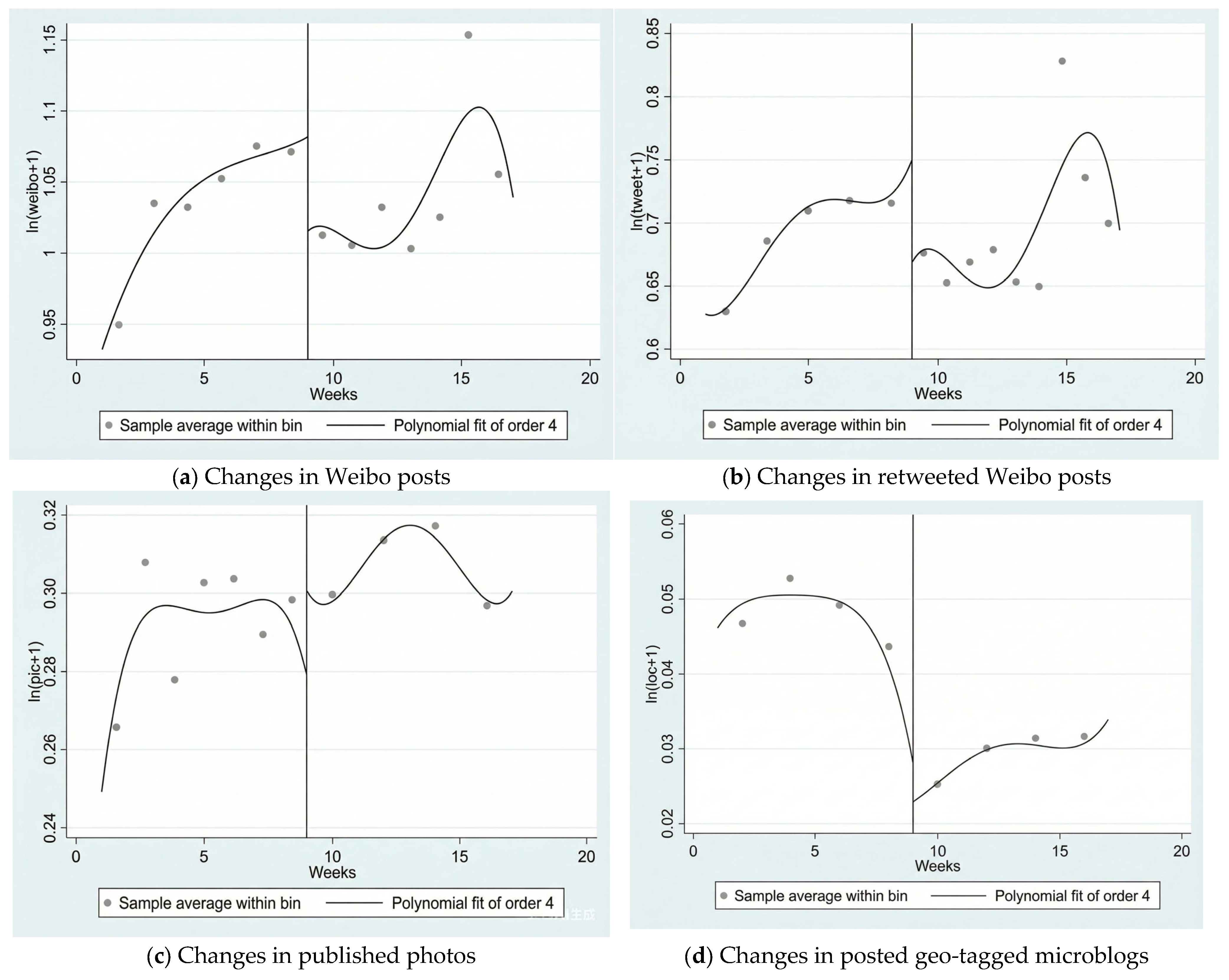

We first visualize changes in social media participation behavior by graphs, as shown in Figure 2. The vertical line in the figure indicates the time when the new function was launched (week 9). From Figure 2, we can intuitively see that the number of posting microblogs, reposting microblogs, and posting geo-tagged microblogs had a negative jump after the new function was launched, and the graphic change trends of the number of posting and reposting microblogs are similar, both declining first and then rising in fluctuations. Only the number of photos had a positive jump after the function was launched.

Figure 2.

Discontinuity diagram of social media participation behavior before/after the launch of new functions.

Note: ln(post + 1) means posting microblogs, ln(repost + 1) means reposting microblogs, ln(pho + 1) means posting photos, and ln(loc + 1) means posting geo-tagged microblogs. Bin-scatter plot with equal-width bins (1 week) and local linear fit on each side of the cutoff (week 9). Shaded area indicates 95% confidence intervals.

However, graphical observations are not sufficient to verify our hypotheses. Referring to the econometric model of Cavusoglu [7], we select users’ registration date, total number of microblogs, and gender as control variables.

We estimate the RDD specification given in Equation (1). Table 3 and Figure 2 report the regression discontinuity results, from which we draw the following conclusions: ① The regression coefficients of the number of posted microblogs, reposted microblogs, and posted geo-tagged microblogs are significantly negative in statistics, i.e., they have a discontinuous negative jump around the cutoff, consistent with results in Figure 2a,b,d. ② Although Figure 2c shows a positive jump in posting photo microblogs around the cutoff, its estimated coefficient is not significant at the 10% statistical level. We conclude that the mandatory disclosure of users’ IP locations does not have an impact on the number of posted photos. A possible explanation might be that plog (recording life via photos) has become a social sharing trend among young people in recent years; thus, though users might perceive the privacy issues brought about by the public disclosure of IP location, they still continue to share photos for reasons such as maintaining and expanding social relationships and following trends. ③ Since the new function casts inconsistent impacts on users regarding different types of posts, we suggest that it has changed users’ social media participation patterns. Although most sample users have filled in their address information in their profiles, some of them are not consistent with the revealed IP location, which means that the users have options to manipulate the authenticity of the information disclosed. However, the policy of mandatory IP location openness does not only require mandatory disclosure but also dynamic updates of locations, which has weakened users’ control of personal information. The above changes in disclosure behavior reflect that users may establish new privacy rules to manage and protect their privacy in the trade-off between benefits and risks of social media participation.

Table 3.

Regression discontinuity results.

4.3. Short-Run Panel Data Regression Analysis

We estimate the panel data regression (PDR) given in Equation (2). The short-run regression results reported in Table 4 imply the following: ① The regression coefficients of posting microblogs, reposting microblogs, and posting geo-tagged microblogs are all negative and significant at the 1% statistical level; i.e., the launch of the new function has an immediate negative impact on the above three behaviors, consistent with the research hypothesis H1 proposed above. ② The regression coefficient of users’ posting photos is not significant at the 10% statistical level. It is reasonable to conclude that the launch of the new function has no prominent effect on posting photos. The short-run regression results are basically consistent with the regression discontinuity results. ③ Overall, IP location openness in the short run has an inhibiting effect on the frequency of social media participation behaviors. In addition, the short-run panel results provide partial support for H2: posting, reposting, and geo-tagged microblogs decline significantly after the policy, whereas photo posting does not.

Table 4.

Short-run fixed-effects regression results.

4.4. Long-Run Panel Data Regression Analysis

Although the full openness of IP location has a negative impact on users’ social media participation behavior in the short run, it remains unclear whether this impact changes over time. Therefore, we build the econometric model given in Formula (3) to examine the long-run impact of full openness of IP location on social media participation behavior. In the baseline long-run specification, we use a symmetric window of eight weeks before and eight weeks after the implementation of full IP location disclosure. This window is the longest interval for which we can observe a complete panel of weekly behavior for our sampled users, given the six-month visibility setting on Sina Weibo, and it provides a good trade-off between capturing persistent behavioral adjustments and avoiding confounding later policy changes. To assess whether our findings depend on this particular choice, we conduct a series of step-length (bandwidth-sensitivity) tests by re-estimating the RDD and panel models on narrower windows. As reported in Table 3 and in the robustness checks (Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9, column (7)), when we reduce the window to five weeks on each side of the intervention, the sign and statistical significance of the coefficient on AfterPolicyt remain unchanged across all four participation measures, and the estimated magnitudes differ only slightly. These results indicate that the eight-week window is empirically reasonable and that our conclusions are not sensitive to the exact long-run window length.

Using the two-way fixed-effects model specified in Equation (3), the regression results in Table 5 show the following: ① In a relatively long time interval, the regression coefficients of posting and reposting microblogs change from negative to positive, indicating that as time goes by, the negative impact of the full openness of IP location on both disappears in the long run. ② The regression coefficient of posting photos is positive and significant at the 1% statistic level, indicating that after a long period, the number of posting photos increases with time. In addition to the popularity of photo sharing among young people mentioned above, it is also likely that although users’ control over disclosed information has weakened, and privacy risks have increased accordingly, photo posts are more secret than the plain and straight text posts, as a result, posting photos has become a new way for users to protect personal information and avoid platforms’ censorship of sensitive topics. ③ Only the regression coefficient of posting geo-tagged microblogs is still significantly negative in the long run; in other words, the short-run negative impact of IP location openness only continues in the disclosure behavior of posting geo-tagged microblogs. The possible reason is that the full openness of IP location made users sensitive to location-related information, causing them to perceive the increased privacy risks of disclosing location information. At the same time, Sina Weibo does not provide personalized services in terms of location; thus, users are not stimulated to continuously disclose location-related information. ④ Taken together, compared with the short-run, the negative impact of IP location openness on the frequency of social media participation behaviors disappears in general, and the impact diverges on users’ social media participation behavior patterns. It can be expected that users’ disclosure of geographic location will decline in the future. ⑤ The change in short-run and long-run impact effects verifies the hypothesis in CPM theory; i.e., the privacy rules that determine users’ social media participation are dynamically changeable. As shown in Appendix A, additional robustness checks using alternative model specifications and clustering methods support the main findings reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Long-run fixed-effects regression results.

Table 5.

Long-run fixed-effects regression results.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Posting Microblogs | Reposting Microblogs | Posting Photos | Posting Geo-Tagged Microblogs |

| Launch of new function () | 0.109 *** | 0.0688 *** | 0.0549 *** | −0.0123 ** |

| (0.0193) | (0.0170) | (0.0116) | (0.00486) | |

| Constant | 0.937 *** | 0.630 *** | 0.249 *** | 0.0470 *** |

| (0.0136) | (0.0121) | (0.00823) | (0.00344) | |

| Individual fixed-effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed-effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 34,051 | 34,051 | 34,051 | 34,051 |

| R2 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.005 |

| Sample size | 2003 | 2003 | 2003 | 2003 |

Note: Robust standard errors are reported in brackets; *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05. Rates (points) were calculated using the unstandardized coefficients.

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

The aforementioned empirical results showed that in the short run, strengthening users’ information surveillance has a negative impact on the frequency of social media participation behaviors. Furthermore, female users are more concerned about their privacy; thus, the open sharing of IP location information may make them feel like they have lost control of their personal information. As a result, they are more likely to limit their social media participation to avoid the risk of privacy breaches. To further investigate the impact of gender on the results, we conducted subgroup regression analyses on both male and female users. The short-term PDR was measured using the econometric model in Formula (2), while the long-term PDR was measured using the econometric model in Formula (3). The results are presented in columns (1)–(4) of Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9.

The short-run PDR results in columns (1) and (2) of Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 indicate that in the male and female samples, the regression coefficient signs of posting microblogs, reposting microblogs, and posting geo-tagged microblogs are precisely the same. However, these three content-sharing activities are not statistically significant in the male samples, while they are significant at the 1% level in the female samples. Neither male nor female samples show considerable regression coefficients for posting photos. These findings suggest that, in the short term, male users are less affected by the strengthened information surveillance resulting from the full openness of IP location, whereas female users are significantly affected by this exogenous shock. The difference in response between the two user groups could be because, although female users are more active on OSN platforms, they face higher privacy risks, resulting in females paying more attention to privacy issues. Therefore, their immediate response to exogenous shocks is more intense. The long-run PDR results in columns (3) and (4) of Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 show that the regression coefficient signs and significance levels of both male and female users regarding posting microblogs, photos, and geo-tagged microblogs are exactly the same. The impact difference caused by genders mainly reflects in the short run.

4.6. Robustness Checks

First, we conduct a ‘placebo test’ to estimate our regression discontinuity analyses. We assume that the new cutoff point is in the 5th week, about a month prior to the real event, when Sina Weibo has not implemented the function of full openness of users’ IP location. Results in column (5) suggest that the ‘pseudo-cutoff’ does not have a significant impact on users’ four disclosure behaviors; hence, the original analyses are reliable. Second, we perform a ‘bandwidth sensitivity test’. We replace the optimal bandwidth with the time window of 5 weeks (before and after) and use the alternative time window to repeat the regression discontinuity analyses. Results reported in column (6) imply that the qualitative nature of the results is the same regarding the impact of the new function on the four social media participation behaviors. To estimate the panel regression analyses, we first repeat the analyses with a modified short-run time window of 5 weeks (before and after). Due to the availability of data, the long-run time window cannot be modified. Results in column (7) are consistent with the original results. Second, although our dependent variables capture the individual-level heterogeneity, the results may still be influenced by users who are more active and disclose more information. Therefore, we eliminate the observations where the number of posted mircroblogs during the sample period (17 weeks in total) is more than two standard variations above the mean and repeat the short-run and long-run panel regression analyses. Results reported in columns (8) and (9) indicate that the regression coefficients do not change qualitatively.

Based on the comparative experiments at different time periods within the group, this study addresses the majority of internal validity threats, such as reciprocal causation. However, there still exist some challenges to the internal validity, mainly including the following three aspects: time trend/seasonal effect (i.e., were the changes in the dependent variable caused by the time effect or seasonal trend?), statistical regression (i.e., did the sample individuals specifically come from the low- or high-performance groups?), and history (i.e., did other current events affect the change in the dependent variables?).

Firstly, one can argue that the frequency and activeness of users’ use of Sina Weibo is likely to be affected by seasonal changes, and therefore, users’ disclosure behavior might fluctuate over time. We deal with this challenge with the use of week fixed-effects in the long-run panel analyses to eliminate time-related variation from the regression results. Meanwhile, we adopt a small time window in the short-run panel analyses; hence the time trend or seasonal effect is unlikely to influence the empirical outcomes. Secondly, we use the random sampling method. The sample source is random and broad, and there is no specific selection of highly active or inactive users; thus, our statistical results do not suffer from sample selection bias. Third, it is possible that the change in disclosure behavior might be due to an event that takes place during the study period. To rule out alternative explanations, we look for relevant events online and confirm that Sina Weibo did not publish any news related to privacy settings during the study period. Overall, seasonal effects, sample selection bias, and history effects do not have a substantial impact on the regression result.

Table 6.

Heterogeneity analyses and robust checks (dependent variable: posting microblogs).

Table 6.

Heterogeneity analyses and robust checks (dependent variable: posting microblogs).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Male Users | Female Users | Male Users | Female Users | Cutoff- (5th Week) | Bandwidth-5 Weeks | Time Window- 5 Weeks (Before/After) | Removing Outliers | Removing Outliers |

| Launch of new function () | −0.0513 | −0.0751 *** | 0.1120 *** | 0.1082 *** | −0.0674 *** | −0.0739 *** | 0.1073 *** | ||

| (0.0393) | (0.0216) | (0.0400) | (0.0220) | (0.0156) | (0.0191) | (0.0193) | |||

| Registration time period () | 0.0000 | 0.0065 | —— | —— | 0.0047 * | 0.0066 | —— | ||

| (0.0097) | (0.0053) | —— | —— | (0.0025) | (0.0047) | —— | |||

| Average treatment effect of RDD | 0.00665 | −0.0940 ** | |||||||

| (0.0342) | (0.0406) | ||||||||

| Constant | 1.1264 | −1.3694 | 1.0110 *** | 0.9143 *** | −0.6808 | −1.4439 | 0.8868 *** | ||

| (3.4756) | (1.9955) | (0.0283) | (0.0155) | (0.9063) | (1.7480) | (0.0137) | |||

| Term | Short run | Short run | Long run | Long run | —— | —— | Short run | Short run | Long run |

| Observations | 3381 | 10,640 | 8211 | 25,823 | 24,671 | 24,671 | 22,033 | 13,748 | 33,388 |

| R2 | 0.0023 | 0.0026 | 0.0042 | 0.0073 | 0.0016 | 0.0026 | 0.0060 | ||

| Sample size | 483 | 1520 | 483 | 1519 | 2003 | 1964 | 1964 |

Note: Robust standard errors are reported in brackets; *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, and * p < 0.1. Rates (points) were calculated using the unstandardized coefficients.

Table 7.

Heterogeneity analyses and robust checks (dependent variable: reposting microblogs).

Table 7.

Heterogeneity analyses and robust checks (dependent variable: reposting microblogs).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Male Users | Female Users | Male Users | Female Users | Cutoff- (5th Week) | Bandwidth-5 Weeks | Time Window- 5 Weeks(Before/After) | Removing Outliers | Removing Outliers |

| Launch of new function () | −0.0460 | −0.0642 *** | 0.0408 | 0.0777 *** | −0.0465 *** | −0.0668 *** | 0.0684 *** | ||

| (0.0357) | (0.0191) | (0.0359) | (0.0194) | (0.0139) | (0.0169) | (0.0170) | |||

| Registration time period () | −0.00319 | 0.0055 | —— | —— | −0.0006 | 0.0062 | —— | ||

| (0.00885) | (0.0047) | —— | —— | (0.0022) | (0.0042) | —— | |||

| Average treatment effect of RDD | 0.00873 | −0.0894 *** | |||||||

| (0.0269) | (0.0318) | ||||||||

| Constant | 1.985 | −1.3732 | 0.7610 *** | 0.5894 *** | 0.9462 | −1.6308 | 0.5808 *** | ||

| (3.164) | (1.7673) | (0.0254) | (0.0137) | (0.8078) | (1.5498) | (0.0120) | |||

| Term | Short run | Short run | Long run | Long run | —— | —— | Short run | Short run | Long run |

| Observations | 3381 | 10,640 | 8211 | 25,823 | 27,574 | 27,574 | 22,033 | 13,748 | 33,388 |

| R2 | 0.004 | 0.0026 | 0.0045 | 0.0098 | 0.0026 | 0.0026 | 0.0080 | ||

| Sample size | 483 | 1520 | 483 | 1519 | 2003 | 1964 | 1964 |

Note: Robust standard errors are reported in brackets; *** p < 0.01. Rates (points) were calculated using the unstandardized coefficients.

Table 8.

Heterogeneity analyses and robust checks (dependent variable: posting photos).

Table 8.

Heterogeneity analyses and robust checks (dependent variable: posting photos).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Male Users | Female Users | Male Users | Female Users | Cutoff- (5th Week) | Bandwidth-5 Weeks | Time Window- 5 Weeks(Before/After) | Removing Outliers | Removing Outliers |

| Launch of new function () | 0.00306 | −0.0036 | 0.0490 ** | 0.0569 *** | −0.0040 | 0.0005 | 0.0539 *** | ||

| (0.0223) | (0.0143) | (0.0217) | (0.0137) | (0.0099) | (0.0121) | (0.0116) | |||

| Registration time period () | 0.00245 | 0.0028 | —— | —— | 0.0046 *** | 0.0023 | —— | ||

| (0.00552) | (0.0035) | —— | —— | (0.0016) | (0.0030) | —— | |||

| Average treatment effect of RDD | 0.0159 | −0.0122 | |||||||

| (0.0170) | (0.0192) | ||||||||

| Constant | −0.635 | −0.7498 | 0.2011 *** | 0.2643 *** | −1.3883 ** | −0.5834 | 0.2339 *** | ||

| (1.975) | (1.3194) | (0.0153) | (0.0097) | (0.5694) | (1.1074) | (0.0082) | |||

| Term | Short run | Short run | Long run | Long run | —— | —— | Short run | Short run | Long run |

| Observations | 3381 | 10,640 | 8211 | 25,823 | 31,552 | 31,552 | 21,703 | 13,748 | 33,388 |

| R2 | 0.000 | 0.0002 | 0.0020 | 0.0028 | 0.0014 | 0.0002 | 0.0024 | ||

| Sample size | 483 | 1520 | 483 | 1519 | 1973 | 1964 | 1964 |

Note: Robust standard errors are reported in brackets; *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05. Rates (points) were calculated using the unstandardized coefficients.

Table 9.

Heterogeneity analyses and robust checks (dependent variable: posting geo-tagged microblogs).

Table 9.

Heterogeneity analyses and robust checks (dependent variable: posting geo-tagged microblogs).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Male Users | Female Users | Male Users | Female Users | Cutoff- (5th Week) | Bandwidth- 5 Weeks | Time Window- 5 Weeks(Before/After) | Removing Outliers | Removing Outliers |

| Launch of new function () | −0.0127 | −0.0219 *** | −0.0221 ** | −0.0091 * | −0.0211 *** | −0.0193 *** | −0.0129 *** | ||

| (0.0116) | (0.0052) | (0.0113) | (0.0053) | (0.0040) | (0.0049) | (0.0049) | |||

| Registration time period () | −0.00431 | 0.0011 | —— | —— | 0.0003 | −0.0004 | —— | ||

| (0.00286) | (0.0013) | —— | —— | (0.0006) | (0.0012) | —— | |||

| Average treatment effect of RDD | −0.00428 | −0.0139 * | |||||||

| (0.00679) | (0.00723) | ||||||||

| Constant | 1.600 | −0.3664 | 0.0605 *** | 0.0427 *** | −0.0459 | 0.1961 | 0.0467 *** | ||

| (1.023) | (0.4838) | (0.0080) | (0.0038) | (0.2315) | (0.4503) | (0.0035) | |||

| Term | Short run | Short run | Long run | Long run | —— | —— | Short run | Short run | Long run |

| Observations | 3381 | 10,640 | 8211 | 25,823 | 33,620 | 33,620 | 22,033 | 13,748 | 33,388 |

| R2 | 0.009 | 0.0053 | 0.0092 | 0.0039 | 0.0049 | 0.0060 | 0.0050 | ||

| Sample size | 483 | 1520 | 483 | 1519 | 2003 | 1964 | 1964 |

Note: Robust standard errors are reported in brackets; *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, and * p < 0.1. Rates (points) were calculated using the unstandardized coefficients.

4.7. Clustered Standard Errors

To further assess the robustness of our findings, we re-estimate the interaction models in Equations (4) and (5) using standard errors clustered at the week level. This adjustment accounts for within-week correlation in the error terms and yields more reliable inference.

Table 10 reports the estimates for the interaction between the launch of the new function and regional information (i.e., whether a post contains geographical data). The coefficient of the interaction term is positive and significant for posting photos (0.0262, p < 0.05) and negative and significant for geo-tagged microblogs (−0.0147, p < 0.01), while the effect on posting microblogs is not statistically significant. These results indicate that IP location disclosure continues to suppress geo-tagging even when posts already contain geographic information, whereas photo posting exhibits a modest increase.

Table 10.

Interaction effects with regional information (standard errors clustered at the week level).

Table 11 presents the baseline policy effect with week-clustered standard errors. The coefficients for posting microblogs, reposting microblogs, and posting photos are all positive and statistically significant, whereas the coefficient for geo-tagged microblogs remains negative and significant. This pattern is consistent with our main results and confirms that the long-run chilling effect of IP location openness is concentrated on geo-tagging behavior.

Table 11.

Baseline policy effects (standard errors clustered at the week level).

5. Discussion

The empirical results above indicate that full openness of IP location have a short-term inhibitory effect on users’ social media participation behavior, such as reducing the frequency of posting and reposting microblogs and posting geo-tagged microblogs, whereas photo posting is not significantly affected in the short run, and the overall inhibitory effect disappears in the long term. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that social platforms did not obtain users’ consent before updating the full open IP location function. As a result, users’ information surveillance over IP location strengthened, and they became concerned about their privacy in the short term, leading to a reduction in public social media participation behavior. In the social network, it may cause frequent phenomena such as regional discrimination. However, in the long run, the benefits users gain from social media participation (such as establishing and maintaining social relationships, personalized services, etc.) might outweigh the privacy risks, resulting in the disclosure of more personal information. Many users lack a deep understanding of the business models of social platforms and how these platforms manage their personal data, which leads to their inability to protect their privacy effectively. Even if users have high privacy awareness, they rarely translate it into actual privacy protection behaviors. Therefore, it is essential to educate users about the potential risks of social media participation and the importance of privacy protection.

From the point of view of specific social media participation behavior, whether in the short or long term, the full openness of IP location has a negative effect on users’ posting geo-tagged microblogs. The possible reasons for this phenomenon are as follows: the full opening of IP location leads to the public real-time display of users’ whereabouts and trajectories to all, and the improvement in the visibility of sensitive information will significantly increase users’ privacy concerns, thus leading users to continuously reduce the disclosure of location information. At the same time, it is worth noting that full open IP addresses have no significant effect on users’ behavior of posting pictures in the short term. The reasons for this phenomenon may be as follows: When users share pictures on social platforms, it helps to show their “highlight moment”, share activities, and shape their own personality and image on network media, etc. In particular, tagging the co-owners with the photos plays an important role in maintaining social relations. These unique roles make users willing to post pictures on Weibo even when they face privacy risks. In addition, posting text information in the form of pictures makes it difficult for other users to use keywords to retrieve the message to a certain extent, which is a means to protect private information, which may lead users to prefer posting photos.

These findings speak directly to H2. The policy does not uniformly suppress all identity-revealing behaviors. Instead, it imposes a persistent chilling effect on location-based disclosures—geo-tagged microblogs—while leaving photo posting largely unaffected in the short run and even encouraging more photo sharing in the long run. In this sense, H2 receives partial support: mandatory IP location openness most strongly discourages those identity-revealing behaviors that directly and explicitly expose users’ whereabouts.

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

Our study contributes to the theoretical and practical understanding of the relationship between users’ information surveillance and social media participation behavior. Theoretically speaking, first, unlike the prior studies that obtained static data through questionnaire surveys, we examine changes in users’ social media participation behavior by crawling the dynamic data generated by users on the OSN platform and conduct empirical analyses to confirm that heightened information surveillance has a negative impact on social media participation in the short run, and this negative impact largely disappears in the long run, except for geo-tagged microblogs. These findings enrich the empirical support for privacy cynicism theory. Second, photo sharing has become a more common and significant component of OSN platforms. This study expands the influencing factors of photo-sharing activities in the existing research, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the decision-making process of photo-sharing behavior. In addition, strengthening information surveillance has a negative impact on posting geo-tagged microblogs in both the short and long term; this empirical result is consistent with previous research. Finally, we reveal that heightened information surveillance has different impacts on different disclosure behaviors and users of different genders, which enriches the research on social media participation behavior in the context of China. In terms of practice, the research results of our study provide theoretical guidance for major OSN platforms to design new privacy functions and make business innovations. Specifically, the short-run inhibitory effect shows that when OSN platforms launch new privacy settings and functions, they should obtain users’ informed consent, and allow users to have voluntary choices so as to protect users’ privacy and, at the same time, foster users’ social media participation. The outcome that posting photos increases while posting geo-tagged microblogs decreases over time indicates that the Sina Weibo platform can carry out business innovations based on photo-post-related activities, which may bring in new profit growth points. Secondly, our study provides a valuable reference for further improving the Internet platform management legislation in the future to balance the relationship between personal privacy and network order.

This study enriches privacy theories by considering information surveillance as a dynamic variable, offering new insights into how surveillance policies shape social media behaviors. The study also expands the scope of privacy cynicism in the context of actual user behavior, moving beyond privacy concerns to focus on tangible engagement patterns.

5.2. Limitation

The research limitations of this study mainly include the following: ① Due to the limited user information and data obtained through web crawlers, more types of users’ social media participation behaviors (such as liking, commenting, etc.) remain to be further researched. Future studies can broaden the types of social media participation behavior and deepen the depth and breadth of the disclosed contents. ② For the sake of reducing missing values, this paper obtained users who were relatively highly active, so the empirical results cannot represent the overall users’ response to the full openness of IP location. Therefore, the observed behavioral adjustments to IP location openness may be more pronounced among active users than among the general Weibo population.

6. Conclusions

Users’ social media participation is of great significance for OSN platforms whose major businesses rely on users’ content generation. Based on the exogenous shock of Sina Weibo’s full openness of IP location, this study examines the impact of strengthening users’ information surveillance on different social media participation behaviors from a dynamic perspective. Using RDD, PDR, and other methods, our empirical results show that heightened information surveillance has an inhibitory effect on social media participation behavior in the short run, but the negative impact only lasts for posting geo-tagged microblogs in the long run. In addition, this study reveals that female users, compared with male users, significantly diminish the frequency of participation behaviors in the short term. Theoretically, this study expands the analyses of the actual impact of changes caused by heightened information surveillance. In practice, this study provides guidance for OSN platforms to understand users’ behavior better and further optimize services. For other countries, this paper serves as a valuable reference for countries seeking to strike a balance between personal privacy and maintaining order in network security legislation, and has important guiding significance for the formulation of policies to curb the spread of network false information without causing substantial long-term negative effects on overall participation, although geo-tagged microblogs remain persistently suppressed.

This research offers critical insights for policymakers and platform designers. Our findings indicate that users, especially female users, are sensitive to changes in privacy policies, which could lead to reduced engagement. Platforms should consider this when implementing location-based features, ensuring that such policies do not inadvertently diminish user participation. Moreover, understanding the gendered impact of these policies can help platforms better tailor their privacy management strategies, ensuring more inclusive and effective user engagement.

Author Contributions

Z.W.: Determined the framework of the paper, revised the paper and finalized the paper; W.H.: Revised research ideas, Data collection and analysis, paper writing; X.P.: Data collection and analysis, paper writing; W.X.: Revised research ideas. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 25AJY007.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Additional Robustness Checks

To verify the robustness of the main research results, this appendix reports the supplementary analysis results using different model Settings, bandwidth selections, and clustering methods. All analyses are consistent with the conclusions of the main text report.

Table A1.

Conditional Fixed-Effects Poisson Regression Results.

Table A1.

Conditional Fixed-Effects Poisson Regression Results.

| Variable | (1) Posting Microblogs | (2) Reposting Microblogs | (3) Posting Photos | (4) Geo-Tagged Microblogs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Launch of new function () | 0.1453 *** | 0.1344 *** | 0.2295 *** | −0.2745 ** |

| (0.0228) | (0.0297) | (0.0463) | (0.1344) | |

| Registration time period () | −0.0001 ** | −0.0002 *** | −0.0000 | 0.0002 |

| (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0004) | |

| Individual Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Week Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 33,541 | 30,702 | 24,548 | 7055 |

| Number of Groups | 1973 | 1806 | 1444 | 415 |

| Wald χ2 | 189.12 | 270.44 | 77.41 | 51.90 |

| Log Pseudolikelihood | −30,565.62 | −22,534.73 | −13,215.55 | −2178.06 |

Notes: Robust standard errors clustered at the user level are reported in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05. Week fixed effects are included (week 17 omitted due to collinearity). The dependent variables are ln(variable + 1) transformed counts of each posting behavior.

The Poisson fixed-effects results are consistent with our main findings reported in Table 5. In the long-run specification: (1) The coefficient on AfterPolicyt for posting microblogs is 0.1453 (p < 0.01), indicating that after the IP location disclosure policy, posting frequency increased by approximately 15.6% (exp(0.1453)-1). (2) Similarly, reposting microblogs and posting photos show significant positive coefficients (0.1344 and 0.2295, respectively), suggesting increased activity in the long run. (3) Crucially, the coefficient for geo-tagged microblogs remains significantly negative (−0.2745, p < 0.05), implying a 24.0% decrease in geo-tagging behavior—consistent with our hypothesis that users reduce location-sensitive disclosures under heightened surveillance. These results confirm that our main conclusions are robust to alternative count data specifications.

References

- Chen, J.V.; Nguyen, H.V.V.; Ha, Q.A. Understanding Location Disclosure Behaviour via Social Networks Sites: A Perspective of Communication Privacy Management Theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 18, 690–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S. What Drives You to Check in on Facebook? Motivations, Privacy Concerns, and Mobile Phone Involvement for Location-Based Information Sharing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Stefanone, M. Showing off? Human mobility and the interplay of traits, self-disclosure, and Facebook check-ins. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2013, 31, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, N.; Shen, X.; Zhang, J.X. Location Information Disclosure in Location-Based Social Network Services: Privacy Calculus, Benefit Structure, and Gender Differences. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 52, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, S.J.; Krueger, B.S.; Ladewig, J. Privacy in the Information Age. Public Opin. Q. 2006, 70, 375–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oz, M.; Yanik, A. Fear of Surveillance: Examining Turkish Social Media Users’ Perception of Surveillance and Willingness to Express Opinions on Social Media. Mediterr. Polit 2024, 29, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusoglu, H.; Phan, T.Q.; Cavusoglu, H.; Airoldi, E.M. Assessing the Impact of Granular Privacy Controls on Content Sharing and Disclosure on Facebook. Inf. Syst. Res. 2016, 27, 848–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-L.; Wu, Y.; Li, C.; Song, C.; Hsu, W.-Y. Does Displaying One’s IP Location Influence Users’ Privacy Behavior on Social Media? Evidence from China’s Weibo. Telecommun. Policy 2024, 48, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozani, M.; Ayaburi, E.; Ko, M.; Choo, K.-K.R. Privacy Concerns and Benefits of Engagement with Social Media-Enabled Apps: A Privacy Calculus Perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 107, 106–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. Privacy Cynicism and Diminishing Utility of State Surveillance: A Natural Experiment of Mandatory Location Disclosure on China’s Weibo. Big Data Soc. 2024, 11, 20539517241242450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec Zlatolas, L.; Welzer, T.; Heričko, M.; Hölbl, M. Privacy Antecedents for SNS Self-Disclosure: The Case of Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.L.; Quan-Haase, A. Information revelation and Internet privacy concerns on social network sites: A case study of Facebook. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Communities and Technologies; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 265–274. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Lu, Y.; Gupta, S. Disclosure intention of location-related information in location-based social network services. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2012, 16, 53–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siahaan, M.N.; Handayan, P.W.; Azzahro, F. Self-Disclosure of Social Media Users in Indonesia: The Influence of Personal and Social Media Factors. Inf. Technol. People 2021, 34, 1721–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Peter, J. Social consequences of the Internet for adolescents: A decade of research. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleier, A.; Goldfarb, A.; Tucker, C. Consumer Privacy and the Future of Data-Based Innovation and Marketing. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2020, 37, 466–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wei, G.; Lu, Y. Evaluating Gender Representativeness of Location-Based Social Media: A Case Study of Weibo. Ann. GIS 2018, 24, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Liu, J.; Yang, T.; Xu, J. Combating Disinformation or Reinforcing Cognitive Bias: Effect of Weibo Poster’s Location Disclosure. Media Commun. 2023, 11, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrayes, F.S.; Abdelmoty, A.I.; El-Geresy, W.B.; Theodorakopoulos, G. Modelling Perceived Risks to Personal Privacy from Location Disclosure on Online Social Networks. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2020, 34, 150–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strycharz, J.; Segijn, C.M. The future of dataveillancein advertising theory and practice. J. Advert. 2022, 51, 574–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappeler, K.; Festic, N.; Latzer, M. Dataveillance imaginaries and their role in chilling effects online. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2023, 179, 103120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C.P.; Lutz, C.; Ranzini, G. Privacy Cynicism: A New Approach to the Privacy Paradox. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2016, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargittai, E.; Marwick, A. “What Can I Really Do?” Explaining the Privacy Paradox with Online Apathy. Int. J. Commun. 2016, 10, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Jung, Y. Online Users’ Cynical Attitudes towards Privacy Protection: Examining Privacy Cynicism. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 30, 547–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; He, L.; Du, J.; Wu, X. Protection or cynicism? Dual strategies for coping with privacy threats. Inf. Syst. Front. 2024, 27, 1507–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wu, Y.; Deng, F.; Zhi, K. How Does Ad Relevance Affect Consumers’ Attitudes toward Personalized Advertisements and Social Media Platforms? The Role of Information Co-Ownership, Vulnerability, and Privacy Cynicism. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros Herencia, C.A. El Índice de Engagement en Redes Sociales, una Medición Emergente en la Comunicación Académica y Organizacional. Razón Palabra 2018, 22, 96–124. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Xiao, W.; Zhang, C. Data Security Crisis in Universities: Identification of Key Factors Affecting Data Breach Incidents. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvijikj, I.P.; Michahelles, F. Online engagement factors on Facebook brand pages. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2013, 3, 843–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rishika, R.; Kumar, A.; Janakiraman, R.; Bezawada, R. The effect of customers’ social media participation on customer visit frequency and profitability: An empirical investigation. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claussen, J.; Kretschmer, T.; Mayrhofer, P. The Effects of Rewarding User Engagement: The Case of Facebook Apps. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, T. Civilizing social media: The effect of geolocation on the incivility of news comments. New Media Soc. 2023, 27, 14614448231218989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xue, H.; Du, Q. Tagged by region: How IP labels affect people in social media. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xu, Y. User location disclosure fails to deter overseas criticism but amplifies regional divisions on Chinese social media. SSRN Electron. J. [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Ding, F.; Cai, K. The Influence of Self-Efficacy of College Students in Privacy Protection and Behavior in Social Networking Context. Sci. Soc. Res. 2024, 6, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandtzaeg, P.B. Facebook Is No “Great Equalizer”: A Big Data Approach to Gender Differences in Civic Engagement across Countries. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2017, 35, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Hiekkanen, K.; Nieminen, M. Privacy and Trust in Facebook Photo Sharing: Age and Gender Differences. Program Electron. Libr. Inf. Syst. 2016, 50, 462–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]