Abstract

Because Internet of Things (IoT) networks are widely deployed, they have become attractive targets for botnet and distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, which require effective intrusion detection. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) can achieve strong detection performance, but their many hyperparameters are usually tuned manually, which is costly and time-consuming. This paper proposes a new hybrid metaheuristic optimizer, FW-CNN, that combines Grey Wolf Optimization and Red Fox Optimization to automatically tune the key hyperparameters of a one-dimensional CNN for IoT intrusion detection. The Red Fox component enhances exploration and helps the search escape local optima, while the Grey Wolf component strengthens exploitation and guides convergence toward high-quality solutions. The proposed model is evaluated using the N-BaIoT dataset and compared with a feedforward neural network as well as a metaheuristic-optimized model based on the Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization–Whale Optimization Algorithm-CNN. It achieves a final accuracy of 95.56%, improving on the feedforward network by 12.56 percentage points and outperforming the Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization–Whale Optimization Algorithm-based CNN model by 1.02 percentage points. It also yields higher average precision, Kappa coefficient, and Jaccard similarity, and significantly reduces Hamming loss. These results indicate that the proposed hybrid optimizer is stable and effective for multi-class IoT intrusion detection in real environments.

1. Introduction

As per Klaus Schwab’s Fourth Industrial Revolution thesis, the development of a more sophisticated and interconnected society is anticipated to be greatly aided by mobile technology, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things (IoT) [1,2,3]. The rapidly expanding field of the Internet of Things is estimated to have more than 50 billion devices running globally [4,5]. IoT devices have grown more susceptible to malicious attacks as a result of the lack of basic security procedures [6,7]. As stated by Statistica, 5200 attacks are made against IoT devices each month [8,9]. According to research conducted after the COVID-19 pandemic, 71% of security experts think that IoT network security flaws are getting worse [10,11]. Several studies [12,13,14] describe the security vulnerabilities and attacks that impact every Internet of Things layer and offer solutions for preserving privacy [15,16,17]. Several research efforts have resulted in intrusion detection systems as the number of attacks on Internet of Things devices has increased [18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

Following the examination of networks or systems for nefarious activities and infractions of established policies, an intrusion detection system (IDS) produces documentation and notifications concerning hostile behaviour [25,26]. The implementation of an advanced intrusion detection system is essential, as numerous systems may obscure dubious network behaviours. Intrusion detection systems (IDS) fall into two main categories: host intrusion detection systems (HIDS) and network intrusion detection systems (NIDS) [27]. Network traffic is examined and assessed by a network-based intrusion detection system (NIDS), which carefully examines data packets in order to quickly spot unusual or potentially dangerous patterns. On the other hand, an intrusion detection system (HIDS) that is host-based, functions on separate hosts or servers, monitoring system logs, config files, and local activity to capture unauthorized access or anomalous modifications at the host level. Together, these techniques provide additional layers of protection with NIDS addressing extrusion and network-borne threats and HIDS providing better visibility into host-based intrusions [28].

In this study, the N-BaIoT dataset was chosen as the primary dataset because, compared with alternatives such as KDDCUP99, NSL-KDD, and UNSW-NB15—which are widely used but limited by outdated traffic, duplicated records, and lack of IoT-specific attack scenarios—it offers more realistic and relevant data. Although more recent datasets like CICIDS2017 and BoT-IoT provide a broader range of attacks, they are either not specifically IoT-oriented or excessively large in scale, making feature extraction and training more complex. By contrast, N-BaIoT was generated from real IoT devices infected with Mirai and Bashlite botnets, yielding realistic traffic patterns and a rich set of statistical features. These characteristics not only make it well-suited for the evaluation of anomaly detection methods in IoT environments but also enable fair comparisons with other recent research works using the same dataset [29]. The identical botnet virus N-BaIoT dataset used in this work has been utilized by other researchers to test their own methods. Bahsi et al. [30] achieved better levels of accuracy using the feature selection method to minimize the overall count of features used in the process of IoT bot detection. Meidan et al. [31] built a deep autoencoder to detect DDoS assaults by extracting statistical features that characterize typical IoT traffic. The experimental findings suggest that anomaly detection methods could greatly improve attack traffic detection accuracy.

Intrusion detection systems actually make use of machine learning (ML) technology, as demonstrated in [32,33,34]; however, anomaly traffic detection and dataset pre-processing are laborious and complicated [35,36]. Deep learning (DL) methods, on the other hand, have the potential to map features more thoroughly and with more unique feature spaces [37,38,39,40]. Preprocessing time is decreased by combining DL technologies with a conventional ML model [41]. A multitude of algorithms, including k-nearest neighbours (KNN), support vector machines (SVM), and naïve Bayes, among others, have been used to identify Internet of Things (IoT) intrusions within networks, mitigate the incidence of false alarms, and enhance the overall detection rate [29,42,43,44,45,46,47]. A convolutional neural network (CNN) represents a sophisticated deep learning paradigm that autonomously delineates salient features from the feature space of empirical data through the utilization of a convolutional layer.

The hyperparameters necessitate modification throughout the training of neural networks and the process of weight optimization. Consequently, various researchers have employed optimization algorithms such as Adadelta, rmsprop, Adamax, Adagrad, and Adam to facilitate the adjustment of hyperparameters [48,49,50]. A multitude of hyperparameters, encompassing the quantity of neurons within the fully connected layer, the pooling layer, the convolutional layer, and the hidden layers, must be meticulously calibrated during the neural network development phase.

It makes sense to take into account optimization techniques for unknown hyperparameters if one wants to improve the performance of a CNN with unknown hyperparameters. An effective substitute for handling this intricate optimization environment is bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithms. Some of the methods that have been used with good results in ML model tuning include the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) [51], Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) [52], and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [53]. Recent studies, such as the hybrid Adaptive PSO and WOA (APSO-WOA-CNN) by Bahaa et al. [54], are highly successful but limited by computational cost and being prone to premature convergence. Other approaches, like GWO-ELM [55] and FS-ROA [56], are also highly promising but do not have a well-balanced means of global exploration and local exploitation, which is highly essential in finding resilient hyperparameter sets.

To address these limitations, the current study proposes a new hybrid FW-CNN model for IoT intrusion detection. The strategy successfully blends the Red Fox Optimization (RFO) algorithm’s powerful exploratory capabilities with the Grey Wolf Optimizer’s (GWO) superior exploitation qualities [57]. The social ordering of the GWO properly guides the search into potential regions, while RFO’s escaping behaviour to avoid local optima and evasive hunting strategies for local search ensure a complete exploration of the hyperparameter space. The hybrid method is designed to find an improved and accurate set of hyperparameters for a 1D-CNN model, which will enhance detection performance for a variety of IoT network attacks. The primary contribution of this work is to propose a new hybrid metaheuristic algorithm, namely FW-CNN, for fine-tuning 1D-CNN hyperparameters in IoT intrusion detection systems. The proposed strategy synergistically combines the strengths of GWO, well-known for effective exploitation, with the RFO algorithm, well recognized for its adaptive exploration, achieving a superior trade-off between global search and local refinement while preventing premature convergence. In addition, the performance of FW-CNN is thoroughly assessed through the benchmarking N-BaIoT dataset, and the superiority is demonstrated through its comparison with multiple state-of-the-art baseline models, such as FNN, APSO-CNN, and the APSO-WOA-CNN model introduced in [54].

The sections of this work that follow are organized as follows: The literature review is found in Section 2. Section 3 describes the dataset, how it was prepared, and the proposed methodology, which involves the hybridization of the GWO and RFO algorithms as well as the 1D-CNN architecture. Section 4 presents the set-up of the experiment, its outcomes, and comparisons of performance. Section 5 concludes the report with recommendations for further study.

2. Literature Review

The rapid growth of the Internet of Things (IoT) has increased the need for improved and effective intrusion detection systems (IDS) to combat the growing range of cyberattacks, such as wormhole vulnerabilities, Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks, and botnet intrusions. IDS is the most important defence barrier for IoT security, according to researchers, and research scales are moving toward the application of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) approaches to increase system resilience [29]. For instance, Bahaa et al. [29] combined 49 articles and determined that hybrid ML-based IDSs have better detection abilities against attacks targeting IoT. Their survey, though, emphasized underlying constraints, e.g., dataset bias—since most models are designed based on simulated IoT traffic rather than real traffic—and inadequate integration into production workflows such as DevSecOps. These highlight the primary research issue: the development of hybrid algorithms for intrusion detection systems compatible with IoT underpinning accuracy, efficiency, and scalability balance. While ML models were initially successful models, they remain handicapped by high preprocessing and low adaptability [58]. DL approaches, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), provide richer feature extraction [59] but are highly essential to hyperparameter tuning [60]. Hyperparameter optimization strategies are generally classified into two main categories: manual and automatic methods. In manual tuning, discovering an efficient network architecture is typically a laborious and frustrating task, and automatic approaches are unable to frequently properly fine-tune hyperparameters to achieve the best model configuration. Since traditional techniques, such as gradient descent, are not well-suited for handling this type of optimization problem [61], recent research has shifted toward biologically inspired metaheuristic algorithms—including PSO, WOA, GWO, and RFO—which offer more efficient search and tuning mechanisms, thereby enhancing the performance of intrusion detection systems (IDSs).

The recent research in IoT security can be categorized into four broad themes: (1) Hybrid Metaheuristic-CNN Models for intrusion detection, (2) Standalone Optimiz-er-CNN Models, (3) Non-CNN Hybrid Frameworks for Intrusion Detection, and (4) Lightweight and Resource-Efficient IDS Designs. This section will review and synthesize some key contributions within these categories, as summarized in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4, to clearly identify the research gap addressed by our proposed FW-CNN model.

2.1. Hybrid Metaheuristic-CNN Models for Intrusion Detection

Several studies have explored combining CNN architectures with hybrid metaheuristic algorithms. Bahaa Ahmed et al. [54] presented a hybrid, deep learning model dubbed APSO-WOA-CNN, which integrates two optimization methods, i.e., the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) and Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization (APSO), with deep learning-based convolutional neural networks to perform optimization in the detection of IoT attacks. The hybrid optimization provided 94.54% accuracy on the N-BaIoT dataset, which indicates the hybrid optimization was an effective means of optimizing parameters with stable classification. As a research direction, the authors highlighted reducing compute overhead and possibly additional hybrids that will continue to improve detection performance with optimization. Shan et al. [62] proposed a WOA–GWO hybrid IDS by incorporating the whale and grey wolf optimizers into a combination to enhance the exploration vs. exploitation trade-off. The model was able to achieve high accuracy for benchmark detection, but the evaluation was mainly performed over NSL-KDD and focused on binary classification, not incorporating a complete understanding of complex IoT attack scenarios. Future lines of work suggested by the authors are experimentation over IoT-specific datasets such as N-BaIoT and BoT-IoT to evaluate scalability. Wafi and Nickray [63] proposed a data-optimized CNN–GRU model with the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) to improve intrusion detection in IIoT systems. The method used GWO to hyperparameter-tune hyperparameters like convolutional layers, filter sizes, and learning rates to significantly improve performance over baseline CNN–GRU models. The optimized network achieved 99.3% accuracy, 97% F1-score, 97.8% precision, and 96.7% recall on the Edge-IIoTset dataset, outperforming more recent comparative benchmarks. Its most important contribution was reducing false alarms and improving reliability through effective hyperparameter fine-tuning. However, using only GWO led to the dangers of premature convergence as well as lack of exploration. Potential future work, the authors suggest, can involve hybrid optimization and federated learning for further scalability and real-time use in IoT security applications. Khan et al. [64] suggested an adaptive hybrid IDS model for IIoT based on artificial neural networks with genetic algorithm-based feature optimization. The approach achieved 99.7% accuracy and an AUC of 0.9969 with high precision (0.97) and recall (0.98). Its key strength is achieving a balance between high detection performance and low computational expense with optimized feature selection. The downside is, though, weaker performance against low-profile attacks such as Probe and R2L, when the subtle traffic patterns are harder to capture. There is even a potential for limited generalization to actual real-time dynamic IIoT situations. Directions for future work by the authors involved extending to multi-class attack cases, testing on larger IoT datasets, and considering federated learning for scalable deployment.

Table 1.

Hybrid Metaheuristic-CNN Models for Intrusion Detection.

Table 1.

Hybrid Metaheuristic-CNN Models for Intrusion Detection.

| Study | Model | Dataset | Key Result | Limitation/Future Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahaa Ahmed et al. [54] | APSO-WOA-CNN | N-BaIoT | 94.54% Accuracy | High computational overhead; need for more efficient hybrids. |

| Shan et al. [62] | WOA-GWO Hybrid IDS | NSL-KDD | Achieved high accuracy for binary classification, improving the exploration-exploitation trade-off. | Evaluated on a non-IoT dataset (NSL-KDD) and limited to binary classification. Future work includes testing on IoT-specific datasets (e.g., N-BaIoT, BoT-IoT). |

| Wafi and Nickray [63] | CNN-GRU with GWO | Edge-IIoTset | Achieved 99.3% accuracy, 97% F1-score, 97.8% precision, and 96.7% recall, significantly improving over baselines. | Using only GWO leads to risks of premature convergence and lack of exploration. Future work involves hybrid optimization and federated learning. |

| Khan et al. [64] | Adaptive Hybrid ANN (with GA) | IIoT-specific Dataset | Achieved 99.7% accuracy and an AUC of 0.9969, balancing high detection with low computational cost. | Weaker performance against low-profile attacks (e.g., Probe, R2L); limited generalization to dynamic IIoT environments. Future work includes multi-class testing and federated learning. |

2.2. Standalone Optimizer-CNN Models

A different area of research is to improve CNN-based IDS in a standalone optimization style of an optimizer. This means to optimize the model performance independently as opposed to focusing on a hybrid approach involving multiple optimizers. Sagu et al. [65] presented a GRU–CNN architecture SUCMO-optimized to recognize temporal and spatial traffic patterns. Their method was better than baseline CNN models, especially for complex datasets such as UNSW-NB15. The main constraint is high-computation requirements, and thus, it is not ideal for low-resource IoT devices. The authors’ ongoing work is developing more efficient versions for resource-constrained environments. Alashjaee [66] presented an Attention–CNN–LSTM model that uses CNN for spatial learning, LSTM for temporal learning, and attention to draw attention to significant patterns. Tested on NSL-KDD and Bot-IoT, it outperformed conventional baselines with accuracy rates of 97.5% and 94.8%, respectively, and good F1 and MCC scores. Its strength lies in its capability of extracting spatial as well as temporal features and having inference times that are very fast. But the approach was experimented with mostly on older or limited datasets, reducing its effectiveness in diverse IoT environments. The authors proposed future validation on newer datasets like CIC-IDS2017 and TON_IoT, in addition to adversarial training for enhanced robustness. Ankalaki et al. [67] developed a hierarchical PSO algorithm for optimizing 1D-CNN hyperparameters, a method that achieved a notable activity detection rate of 99.82%. The model’s potential computational cost and risk of local optima constrain its practical adoption, despite its high accuracy. Future work could explore hybrid optimization. Ferrag et al. [68] designed an IDS DL-based IDS (CNN) for DDoS attack detection in agriculture with 99.95% accuracy, but data imbalance impacts the detection of infrequent attacks, and FL/blockchain integration must be included for the future. Wu et al. [69] illustrated that BO surpasses hand tuning for CNNs and RFs but did not succeed when used to optimize neural architecture search, for which next-generation hybrid optimizers were required. Elmasry et al. [70] suggested feature/hyperparameter co-optimization by PSO, which produced 99.9% attack detection but fell short of real-time requirements because of low computation costs and offline processing. Hu et al. [71] examined PSO/GWO/GA for IDS and found that while hybrids perform better than singles, they fall short of real-time requirements, necessitating lightweight solutions.

Table 2.

Standalone Optimizer-CNN Models for Intrusion Detection.

Table 2.

Standalone Optimizer-CNN Models for Intrusion Detection.

| Study | Model | Dataset | Key Result | Limitation/Future Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sagu et al. [65] | GRU-CNN (SUCMO-optimized) | UNSW-NB15 | Outperformed baseline CNN models in recognizing spatiotemporal traffic patterns. | High computational requirements, unsuitable for low-resource IoT devices. Future work aims at more efficient versions for constrained environments. |

| Alashjaee [66] | Attention-CNN-LSTM | NSL-KDD, Bot-IoT | Achieved 97.5% and 94.8% accuracy on respective datasets, with fast inference times and strong spatiotemporal feature extraction. | Tested on older/limited datasets, reducing effectiveness for diverse IoT. Future validation on newer datasets (CIC-IDS2017, TON_IoT) and adversarial training. |

| Ankalaki et al. [67] | 1D-CNN with Hierarchical PSO | IoT-specific | Achieved a notable activity detection rate of 99.82%. | High computational cost and risk of local optima constrain adoption. Future work could explore hybrid optimization. |

| Ferrag et al. [68] | DL-based CNN for DDoS (Agriculture) | Agriculture-specific dataset | Achieved 99.95% accuracy for DDoS attack detection in agriculture. | Data imbalance affects detection of infrequent attacks. Future integration of Federated Learning (FL) and blockchain is needed. |

| Wu et al. [69] | Bayesian Optimization (BO) for tuning | General (CNNs, RFs) | Illustrated that BO surpasses manual tuning for CNN and Random Forest hyperparameters. | Failed when applied to Neural Architecture Search (NAS), indicating a need for next-generation hybrid optimizers. |

| Elmasry et al. [70] | Feature/Hyperparameter co-optimization via PSO | NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017 | Produced 99.9% attack detection accuracy. | Fell short of real-time requirements due to computational cost and reliance on offline processing. |

| Hu et al. [71] | Analysis of PSO/GWO/GA for IDS | IoT-specific | Found that hybrid optimizers perform better than single ones. | All approaches (single and hybrid) fell short of real-time requirements, necessitating development of lightweight solutions. |

2.3. Non-CNN Hybrid Frameworks for Intrusion Detection

This category encompasses non-CNN models as well as alternative hybrid frameworks designed for IoT intrusion detection, along with applications in non-IoT domains that demonstrate comparable principles. Zada et al. [72] proposed a PSO–GA feature selection-based hybrid intrusion detection system for IoT combined with ensemble classification using ELM–BA. The model was formulated to reduce redundant features for swift detection and efficiency. The model attained a very high accuracy of 99.96% in the CICIDS-2017 dataset with flawless detection of critical attacks such as PortScan, SQL Injection, and Brute Force. The main strength of the research lies in balancing precision and efficiency, supplemented with visual analytics that improve interpretability. The limitation is reliance on a single dataset and the use of relatively more traditional classifiers, which compromises generalizability as well as the handling of more challenging, real-world IoT traffic. As the way forward, the authors suggested adopting Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL), testing on larger and more diverse datasets, and embedding Explainable AI (XAI) methodologies for boosting scalability, trust, and deployment in mission-critical IoT ecosystems. Pokhrel et al. [73] designed SMOTE-enhanced KNN, which is highly accurate in detecting IoT botnets, but it falls behind in tracing dynamic attack patterns. Gonçalves et al. [74] proposed GA-PSO-boosted CNNs, which require little tuning and obtain a 0.92 F1-score for cancer detection but are still too resource-hungry for use in hospitals. Alharbi et al. [75] suggested a hybrid inertia-weighted BA-NN method that detects 90% of N-BaIoT botnets; however, its real application is limited by its imbalance and computational requirements, which led to the use of hybrid algorithms. Nematzadeh et al. [76] suggested the GWO/GA metaheuristic framework for biomedical ML/DNN tuning, which achieved 99.5% diagnostic accuracy but lacked scale and real-time flexibility, calling for streaming optimizations. Brodzicki et al. [77] suggested whale-inspired 3D-WOA for DNN tuning achieved 89% accuracy; nevertheless, its poor speed and discretization hinder its practical application. Ali et al. [78] suggested ESCNN for IoT RAM attacks, which achieved 99.29% accuracy; nevertheless, it requires threat-scenario testing because it is not validated in dynamic IoT contexts. Alzaqeba et al. [55] suggested a GWO-ELM hybrid boosted by AI, which achieves 81% accuracy and surpasses PSO/GWO in convergence; nonetheless, enterprise security requires greater threat coverage. Abbasi et al. [79] illustrated that LR is more efficient than ANN/CNN for IoT NIDS (N-BaIoT) with 99% accuracy, but ANN scalability supports complicated installations requiring hybrid techniques. Daghighi et al. [80] created a hybrid DRL-metaheuristic that uses less energy and has an accuracy of 95.3% for IoT, but it needs to be validated in a real smart grid. Maazalahi et al. [81] created an IDS based on swarm intelligence that has 99.8% botnet detection (BOT-IoT); nevertheless, edge devices need DL acceleration due to computational overhead. Maazalahi et al. [82] designed a metaheuristic-ensemble IDS with a 99.9% DDoS accuracy rate; DL integration is necessary for IoT security in real-time. Rabie et al. [83] designed a feature-optimized IDS (DRF-DBRF) that requires FL update for distributed deployment and has a 99.8% detection rate of IoT threats. Alqahtany et al. [84] created EGWO-tuned RF, which has a 99.93% accuracy rate for IoT networks and needs public sector confirmation before being adopted in smart cities and hospitals. A framework proposed by Doshi et al. [85] demonstrates a high detection accuracy exceeding 99% for IoT DDoS attacks. However, the framework’s dependence on simulated data raises substantial concerns about its effectiveness in real-world IoT environments, where network conditions and attack vectors are significantly more complex and unpredictable. Anthi et al. [86] suggested Pulse (hybrid ML-IDS) performs well on IoT probe detection but badly on floods (UDP/SYN) due to low attack coverage in testing. Prachi Shukla [87] ML-IDS can detect wormhole attacks (K-means: 93% accuracy but high FPs; Hybrid: balanced), but Internet of Things real-world implementation is limited to simulation only.

Table 3.

Alternative & Non-CNN Hybrid Frameworks for Intrusion Detection.

Table 3.

Alternative & Non-CNN Hybrid Frameworks for Intrusion Detection.

| Study | Model | Dataset | Key Result | Limitation/Future Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zada et al. [72] | PSO-GA Feature Selection + ELM-BA Ensemble | IoT/CICIDS-2017 | 99.96% accuracy with perfect detection of critical attacks (PortScan, SQL Injection, Brute Force). | Reliance on a single dataset and traditional classifiers limits generalizability to real-world IoT traffic. Future: Adopt DRL, test on diverse datasets, embed XAI. |

| Pokhrel et al. [73] | SMOTE-enhanced KNN | IoT Botnet | Highly accurate in botnet detection. | Falls behind in tracing dynamic, evolving attack patterns. |

| Gonçalves et al. [74] | GA-PSO-boosted CNNs | Biomedical (Cancer Detection) | Achieved 0.92 F1-score with minimal tuning. | Too resource-intensive for practical hospital deployment. |

| Alharbi et al. [75] | Hybrid Inertia-weighted BA-NN | N-BaIoT | Detects 90% of N-BaIoT botnets. | Limited by data imbalance and high computational requirements, prompting the need for hybrid algorithms. |

| Nematzadeh et al. [76] | GWO/GA Metaheuristic Framework | Biomedical ML/DNN Tuning | 99.5% diagnostic accuracy. | Lacks scalability and real-time flexibility; requires streaming optimizations. |

| Brodzicki et al. [77] | Whale-inspired 3D-WOA for DNN Tuning | Fashion MNIST | 89% accuracy. | Poor speed and discretization issues hinder practical application. |

| Ali et al. [78] | ESCNN for IoT RAM Attacks | IoT RAM Attacks | 99.29% accuracy. | Not validated in dynamic IoT contexts; requires threat-scenario testing. |

| Alzaqeba et al. [55] | GWO-ELM Hybrid | UNSW-NB15 | 81% accuracy; surpasses PSO/GWO in convergence. | Enterprise security demands greater threat coverage. |

| Abbasi et al. [79] | LR vs. ANN/CNN for NIDS | N-BaIoT | LR achieved 99% accuracy, being more efficient than ANN/CNN for this dataset. | Highlights that ANN/CNN scalability is needed for complex installations, suggesting hybrid techniques. |

| Daghighi et al. [80] | Hybrid DRL-Metaheuristic | IoT-specific (Smart Grid) | 95.3% accuracy with reduced energy use. | Requires validation in a real smart grid environment. |

| Maazalahi et al. [81] | Swarm Intelligence-based IDS | BOT-IoT | 99.8% botnet detection accuracy. | Edge devices require DL acceleration due to computational overhead. |

| Maazalahi et al. [82] | Metaheuristic-Ensemble IDS | IoT DDoS | 99.9% DDoS accuracy. | DL integration is necessary for real-time IoT security. |

| Rabie et al. [83] | Feature-optimized IDS (DRF-DBRF) | IoTID20, NSL KDD, UNSW NB15 | 99.8% threat detection rate. | Requires Federated Learning (FL) updates for distributed deployment. |

| Alqahtany et al. [84] | EGWO-tuned Random Forest | NF-TOI | 99.93% accuracy. | Needs public sector validation before adoption in smart cities/hospitals. |

| Doshi et al. [85] | ML Framework for DDoS | IoT DDoS | >99% detection accuracy. | Dependence on simulated data raises concerns about effectiveness in complex, real-world IoT environments. |

| Anthi et al. [86] | Pulse (Hybrid ML-IDS) | IoT Probe/Flood Attacks | Performs well on probe detection but poorly on flood (UDP/SYN) attacks. | Low attack coverage in testing limits effectiveness. |

| Prachi Shukla [87] | ML-IDS for Wormhole Attacks | IoT Wormhole Attacks | K-means: 93% accuracy (high FPs); Hybrid: balanced performance. | Implementation is limited to simulation; lacks real-world deployment. |

2.4. Lightweight and Resource-Efficient IDS Designs

One major research direction is to create lightweight and resource-efficient IDS designs. The objective is to maximize detection accuracy while minimizing computational complexity, memory usage, and energy consumption to enable real-time deployment on edge devices. Deshmukh and Ravulakollu [88] proposed IIDNet, a lightweight CNN-based IDS for IoT that jointly involves feature engineering, dimensionality reduction, and hyperparameter adjustment to enhance detection. It outperformed the baseline CNN and MLP models with 95.47% accuracy, 97.98% precision, 93.86% recall, and an F1-score of 95.87%, as it is evaluated on the UNSW-NB15 dataset. Its major strength lies in its trade-off between very high detection and low computational overhead, thereby making it suitable for edge deployment. Though, restriction to a single dataset and lack of real-time validation limit its usage. To be used as future work, the authors propose integration of hybrid/ensemble deep models into the framework and testing with real IoT traffic for scalability and robustness. Marques Da Silva Cardoso et al. [89] suggested CEPIDS with 93–99% DDoS detection and minimal resource consumption (5.6 MB RAM), yet static rules render it hard to keep up with emerging novel threats. Idrissi et al. [90] built a CNN-based BotIDS that detects attacks 99.94% of the time in less than 1 MS, but it fails when faced with sequential threats and skewed data. Saba Tanzila et al. [91] created a CNN system that detects 99.5% of IoT attacks and has been tested in real-world settings with limited energy. De La Torre Parra et al. [92] suggested a distributed CNN (edge)-LSTM (cloud) framework that bridges device-cloud barriers and achieves 94.8% IoT threat detection accuracy but requires energy improvements for widespread adoption. Choudhary et al. [93] created bio-inspired CNN-AO that detects 95.36% of new IoT threats (blackhole/sinkhole), but FL integration is required for edge deployment. Alserhani [94] created a blockchain-IoT security solution using spiking neural networks that has a 98.94% accuracy rate; however, cross-device validation is necessary for enterprise deployment.

Table 4.

Lightweight and Resource-Efficient IDS Designs for IoT/Edge Deployment.

Table 4.

Lightweight and Resource-Efficient IDS Designs for IoT/Edge Deployment.

| Study | Model | Dataset | Key Result | Limitation/Future Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deshmukh and Ravulakollu [88] | IIDNet (Lightweight CNN-based IDS) | UNSW-NB15 | 95.47% accuracy, 95.87% F1-Score; designed for low computational overhead. | Evaluated on a single dataset; lacks real-time validation. Future: Integrate hybrid/ensemble models and test with real IoT traffic. |

| Marques Da Silva Cardoso et al. [89] | CEPIDS (Complex Event Processing-based IDS) | DDoS | 93–99% DDoS detection with minimal resource use (~5.6 MB RAM). | Relies on static rules, making it less adaptive to novel threats. |

| Idrissi et al. [90] | CNN-based BotIDS | IoT Botnet | 99.94% attack detection in <1 ms inference time. | Struggles with sequential threats and imbalanced data. |

| Saba Tanzila et al. [91] | CNN-based Anomaly Detection System | Real-world IoT | 99.5% attack detection; tested in real-world settings with limited energy. | Needs Energy Efficiency Improvements |

| De La Torre Parra et al. [92] | Distributed CNN (Edge)-LSTM (Cloud) Framework | IoT Threats | 94.8% threat detection accuracy; bridges device-cloud barrier. | Requires further energy optimization for widespread adoption. |

| Choudhary et al. [93] | Bio-inspired CNN-AO | Self-generated IoT dataset | 95.36% detection of new IoT threats (e.g., blackhole/sinkhole). | Requires Federated Learning (FL) integration for effective edge deployment. |

| Alserhani [94] | Blockchain-IoT with Spiking Neural Networks (SNN) | Simulated IoT | 98.94% accuracy; integrates blockchain for data assurance. | Needs cross-device validation for enterprise-level deployment. |

2.5. The Proposed Novel Hybrid Algorithm

Unlike previous studies, our research proposes a hybrid meta-heuristic algorithm (FW-CNN) as a novel technique for enhancing the hyperparameters of a convolutional neural network by combining the Red Fox Optimizer (RFO) and Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO). This combination enhances model robustness, reduces premature convergence, and promotes both exploration and exploitation. We then adjusted 10 CNN model hyperparameters employing the N-BaIoT dataset, which has significantly augmented the efficacy of intrusion detection mechanisms within the Internet of Things (IoT) framework.

3. Datasets and Methodology

3.1. Datasets

The dataset of N-BaIoT was developed by Meidan et al. [31] and comprises 115 characteristics in its data samples. To obtain the dataset, the ports of every Internet of Things device were mirrored. After the network was established, benign data was gathered right away to make sure the data included normal traffic. Every statistical value was extracted, including packet jitters, packet counts, and the period between packet arrivals for two various dimensions of packet sizes are considered for both incoming and outgoing data transmissions. A total of 23 distinct characteristics were recorded for each of the five specified temporal intervals: 1 min, 10 s, 100 milliseconds, 500 milliseconds, and 1.5 s, yielding 115 features in total. Utilizing all 115 features, our model was created. Twenty-three statistical features were calculated from each window, as displayed in Table 5.

Table 5.

The N-BaIoT dataset’s attributes [31].

3.2. Data Preprocessing

Using the dataset from Danmini Doorbell, the multiclassification tasks were completed. The 90,000 samples that comprised the original dataset utilized in this study were created by selecting 10,000 records at random from each category of the dataset. Different sample values for the same characteristic varied dramatically, and the model was deceived by certain abnormally large or small pieces of data. The training results were also impacted by distribution. 115 characteristic dimensions made up the dataset that was produced by this technique. To normalize each attribute in the dataset, A standard normal distribution characterized by a mean of zero and a variance of one was generated from the dataset.

The resultant data matrix exhibits Xnxp, wherein p and n correspond to the number of features and samples, respectively. The primary standardization methodology is delineated as follows:

Calculation of each feature’s mean, as shown below:

Here, i refers to a specific sample,

denotes the j-th feature value for that sample, n represents the total number of samples, and

signifies the computed average value for feature j.

Determine the variance of each feature.

where the variance of each feature is represented by

.

Determine the standardization characteristics of the feature for every sample.

The standardized features of the feature in each sample are represented by

.

Following feature standardization, 90,000 records were used to generate 81,001 training samples and 9000 validation samples.

3.3. Methodology

This section covers the structure of the GWO-RFO optimization methods and the one-dimensional CNN technique.

3.3.1. D CNN Algorithm

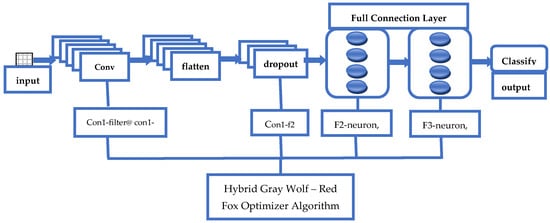

The CNN is a neural network with many layers, with each layer consisting of several two-dimensional planes [95]. The weighted sum of the components from the preceding layer can be used to calculate each neuron’s output and activity. To distinguish between the various kinds of IoT network assaults, we used a 1D CNN in this study, which was built with the help of the Keras library (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The detailed network structure model of the CNN one-dimensional framework.

Layer one from the characteristics of the N-BaIoT dataset across a quintet of temporal intervals, a total of 23 statistical attributes are extracted. In the present investigation, the input dimensionality corresponding to each sample was designated utilizing the 23 × 5 feature matrix.

Presented below is the output generated by the neuron on the feature matrix. The C1 layer neuron produces

, as can be seen below:

The weight of the convolution kernel is represented by

, the length of the filter is represented by f1, and the positional characteristic of the plane is denoted by

. The symbols

(.)(i = 1, 2, 3) signify the non-linear activation functions pertaining to tanh, sigmoid, and relu as utilized in this work, as shown below [52]:

The convolution layer extracts the deeper and more intricate elements from the original input. Before connecting one layer to the next, the feature plane is additionally flattened. When a network’s validation set is less accurate than its training set, overfitting takes place during the training phase. In order to improve the network’s ability to generalize in [96], Hinton suggested that 50% of feature detectors fail during training, a phenomenon known as dropout. As a result, different neuron nodes might be employed in different training cycles, and some neurons might not be utilized in other layers. As a result, network generalization is not enhanced when all neurons cooperate.

Layer two (F2 layer) this is the first layer that has a complete link. The amount and kind of neuron activity are controlled by the connective layer. Every connective neuron is connected to the layer beneath it in every training batch. The output of the m-th neuron in the second layer can be denoted as

, as formulated below:

Here,

refers to the total number of neurons that remain active following the dropout and flattening steps, The parameter

represents the synaptic connection weight between the neuron m in the second layer and the retained neuron n from the earlier layer, Similarly,

indicates the bias associated with the neuron m in this layer, while

denotes the neuron that has been preserved from the preceding layer.

The third layer (F3 layer) serves as the second fully connected stage within the network. In this layer, both the activation pattern and the number of neurons are defined. Each neuron in the F3 layer establishes full connectivity with the neurons of the preceding layer. These two final fully connected layers collectively strengthen the model’s ability to learn and represent the flattened feature maps effectively.

Layer four (layer of output) the fourth layer functions as the network’s output layer, where the information produced by the third layer is transmitted to the fourth layer, wherein the quantity of neurons in the fourth layer is contingent upon the classifications required for the multi-classification task. Layer four assigns the likelihood of each network assault using the softmax algorithm, as seen below:

The probability of the failure of the i-th neuron is denoted by the softmax function

, whereas the magnitude of various types of network assaults is indicated by the term ‘kind’. Cross-entropy quantifies the divergence between the two probability distributions corresponding to the observed and predicted values, as shown below:

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), a technique that alters the bias and connection weights of neurons, was utilized in this study to enhance the training process of the model and maximize detection accuracy.

3.3.2. Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO)

The tactics used in the hunting modes and social hierarchies of wild grey wolves served as the primary inspiration for the Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO), a contemporary nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm first published by Mirjalili et al. (2014) [51]. In terms of tackling real-world optimization problems, the Genetic Algorithm (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) have demonstrated to be more effective than other methods [80,81].

- Social Hierarchy of Grey Wolves

Grey wolves possess a rigid social structure in their packs with four layers:

- •

- Alpha (α): High-ranking wolves who make the decisions (e.g., where to hunt, when and where to relocate).

- •

- Beta (β): Lower-ranking wolves who assist the alpha to impose decisions.

- •

- Delta (δ): Specialist wolves (e.g., scouts, hunters, caregivers).

- •

- Omega (ω): The subordinate wolves who follow members of higher rank.

In GWO, alpha, beta, and delta represent the optimum three solutions, and omega wolves are used to represent all other solutions.

- GWO Mathematical Model

Grey wolf hunting behaviour is simulated via the three main processes of the GWO algorithm: encircling, hunting, and attacking prey.

- Encircling the Prey:

The following equations simulate how the wolves would approach the prey:

where

- •

- : Prey position vector.

- •

- : Grey wolf position vector.

- •

- and : determined the coefficient vectors as follows:

In this case, the random coefficient vectors

and

are generated within the range [0,1], while the control parameter

gradually decreases in a linear manner from 2 to 0 as the iterations progress.

- 2.

- Hunting Prey:

In this stage, the subordinate wolves update their positions according to the directional guidance and positional evaluation of the prey performed by the alpha, beta, and delta wolves:

- 3.

- Attacking the Prey:

The wolves attack when the prey is not moving

. This is simulated by decreasing the range of fluctuation of

by linearly reducing the value of

over iterations.

- Exploration and Exploitation

The GWO algorithm balances exploration and exploitation using the adaptive parameters

and

:

- •

- Exploration: When , wolves leave their prey to look for better options around the world.

- •

- Exploitation: When , wolves converge to the prey to locally update the solution.

Random weights in

(ranging [0,2]) also enhance exploration by amplifying or reducing the effect of the prey during position updates.

3.3.3. Red Fox Optimization (RFO) Algorithm

Polap and Woźniak (2021) [57] developed the Red Fox Optimization (RFO) algorithm, which is a nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm. RFO mimics red foxes’ hunting activities, movement in their environment, and population growth control. It is motivated by the hunting strategy and social behaviour of these animals. The algorithm solves problems by reaching a compromise between local exploitation (stalkingly moving towards the prey) and global exploration (ranging for the prey across landscapes). RFO has been effective in engineering problems and benchmark tests, outperforming traditional algorithms like GA and PSO [57].

- Mathematical Model of RFO

RFO has three main phases: global search, local search, and population management. Below are the main mathematical formulations:

- Global Search Phase (Exploration)

Foxes go into the field to search for food. The alpha fox leads others:

- •

- Distance Calculation:

The Euclidean distance between the alpha fox

and the rest of the foxes

is calculated:

- •

- Movement Update:

Foxes move toward the alpha fox with a random scaling factor α ∈ (0,d):

If the new position improves fitness, the fox stays; otherwise, it returns to its previous position (simulating failed hunts).

- 2.

- Local Search Phase (Exploitation)

Foxes stalk their prey using an adopted cochleoid equation to mimic circling behaviour:

- •

- Action Decision:

The probability of the fox drawing near (μ > 0.75) or staying hidden (μ ≤ 0.75) depends on a random parameter μ ∈ (0, 1).

- •

- Position Update:

If μ > 0.75, the new location of the fox is calculated with vision radius parameters a ∈ (0,0.2) and

∈ (0,2π):

where θ is a random weather influence factor. The coordinates are updated as:

Wherein each angular value is randomized for each point according to ϕ, ϕ2, …ϕn−1 ∈ ⟨0,2π). This model represents the behaviour of a fox after he notices a victim and tries to approach as close as possible to attack, and if he fails when discovered, he tries to approach another one similarly.

- 3.

- Population Management (Reproduction and Replacement)

To avoid local optima, the weakest 5% of foxes are replaced:

- •

- Alpha Couple Selection

The two best foxes

and

define the habitat centre and diameter:

- •

- Replacement MechanismA random parameter κ ∈ (0, 1) decides whether to:

- •

- Reproduce: Create offspring near the alpha couple (κ < 0.45):

- •

- Introduce Nomadic Foxes: Place new foxes randomly outside the habitat (κ≥0.45).

3.3.4. Hybrid GWO-RFO Algorithm

Conventional metaheuristic strategies typically share a fundamental compromise between exploration (global seeking within the search space) and exploitation (local solution improvement). Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) boasts powerful exploitation capability due to its social hierarchy paradigm as well as its cooperative hunting strategies, which guide the population towards the optimal solution discovered. This can lead to premature convergence in highly complex, multi-modal search spaces in certain situations. On the contrary, the Red Fox Optimization (RFO) algorithm has strong global exploration mechanisms via its nomadic population handling and a novel local search approach aimed at preventing being trapped in local optima. Its potential weakness is often a less aggressive convergence than that of GWO. To make the best use of the strengths of both algorithms without their weaknesses, this study proposes a new hybrid metaheuristic algorithm named FW-CNN (Fox-Wolf Convolutional Neural Network Optimizer). The most innovative aspect of Hybrid is its synergistic combination of the social organization and cooperative hunting of the grey wolf and the adaptive exploration and intelligent survival tactic of the red fox. This synthesis is proposed to achieve an improved balance between global search (browsing the entire hyperparameter space) and local tuning (tuning the best-found parameters exactly), ultimately leading to more powerful and robust hyperparameter settings for the CNN-based IDS.

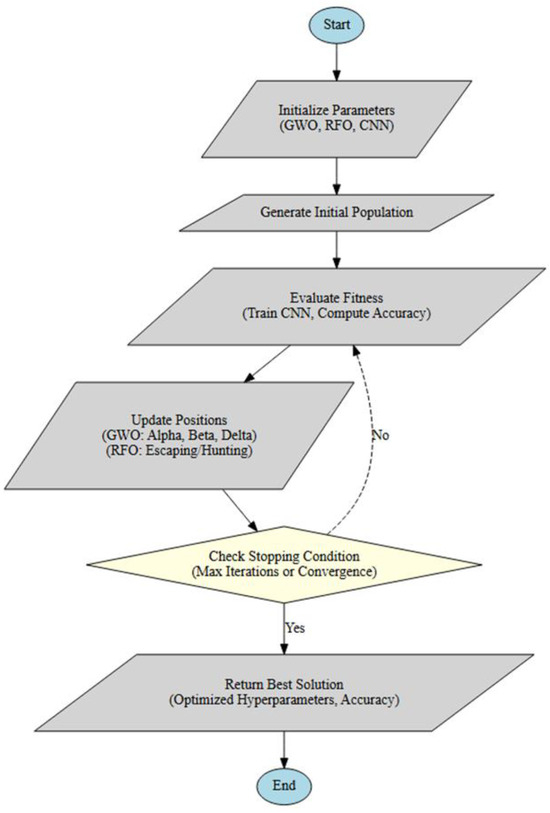

The execution process of the hybrid algorithm, presented in Figure 2, is achieved by the following step-by-step procedure:

Figure 2.

The suggested hybrid FW-CNN algorithm’s operational flow chart for CNN hyperparameter optimization.

Step 1: Initialization

The algorithm begins with the initialization of a population of N candidate solutions (fox-wolves), and every candidate solution is a representative collection of hyperparameters of the CNN model (number of filters, kernel size, dropout value, learning rate, etc.). Search boundaries for each hyperparameter are defined. The initial population is generated randomly within these boundaries. Maximum iterations (

) are defined. The hyperparameters considered in this work, along with their value ranges and data types, are summarized in Table 6 [54]:

Table 6.

The search ranges of CNN hyperparameters [54].

Step 2: Fitness Evaluation

Each candidate solution

in the population is evaluated. This involves configuring the 1D-CNN model with the hyperparameters encoded in the solution, training it on a subset of the training data, and then assessing its performance on a validation set. The classification accuracy is used as the primary fitness function F(

) to be maximized. The candidate that achieves the best fitness score is chosen as the optimal solution, referred to as alpha (α).

Step 3: Hybrid Position Update Mechanism

This phase represents the core of the hybridization strategy. The population is dynamically partitioned, with a proportion of agents updating their positions using the GWO strategy and the remainder using the RFO strategy. A switching parameter ρ ∈ [0,1] can be used to control this ratio, often starting with a higher proportion for RFO (exploration) early on and shifting towards GWO (exploitation) in later iterations.

- •

- GWO-based Update (Exploitation-Leaning): For solutions assigned to the GWO strategy, the standard GWO social hierarchy is enforced. The (α), beta (β), and delta (δ) wolves are the three best solutions. The locations of the alternative solutions (omega wolves, ω) are updated using the standard GWO equations:

This mechanism allows the population to closely and efficiently converge around the most promising regions located by the leaders.

- •

- RFO-based Update (Adaptive Exploration & Exploitation): This is where the Escaping and Hunting mechanism explicitly stated in the flow chart is executed for each agent assigned to the RFO strategy to avoid local optima. a stochastic parameter μ ∈ (0, 1) dictates its tactical behavior:

- •

- Hunting (Local Exploitation): If μ > 0.75, then the agent enters hunting mode, a stealthy, exploitative local search. It takes the present global best solution as prey and moves around it using a complicated movement model based on the Cochleoid equation. It generates a new position spirally, allowing an intensive and refined search in the very close vicinity of the best-known solution.

- •

- Escaping (Global Exploration): If μ ≤ 0.75, the agent is deemed to have been discovered and must escape to avoid stagnation. It calculates a movement vector towards with a random step size: . The key to ‘escaping’ is the rejection criterion: if this new position does not improve fitness, the agent discards it and reverts to its previous position. This forces the agent to effectively abandon an unsuccessful hunt and encourages exploration in a different, potentially more fruitful, region of the search area, preventing premature convergence.

Step 4: Verification of Termination

In every iteration, the algorithm verifies that the halting condition has been satisfied. obtaining as many iterations as possible could be the cause of this circumstance (t = tmax) or observing that improvements in the fitness value have become negligible, dropping below a chosen threshold. If neither of these conditions is met, the procedure loops back to the first step and continues.

Step 5: Output

When the optimization phase comes to an end, the algorithm chooses the best candidate solution (Xα). This solution contains the tuned hyperparameters for the 1D-CNN model and reflects the highest validation accuracy recorded during training. After selecting these parameters, the CNN is retrained on the full training dataset. Its performance is then tested on an independent dataset, providing a balanced and trustworthy evaluation of how well the model can detect IoT intrusions (Algorithm 1).

| Algorithm 1. The FW-CNN Algorithm to Optimize Hyperparameters Pseudocode |

| Input: N = Total populations, d, t_max 1. Initialize parameters for GWO, RFO, and CNN. 2. Generate the initial population. 3. While (t < tmax) 4. Evaluate the fitness for each individual by training CNN and computing accuracy. 5. Update best solutions (alpha, beta, delta for GWO; escaping/hunting strategies for RFO). 6. Update positions of individuals using: - GWO: Alpha, Beta, Delta influence. - RFO: Random escaping and hunting strategies. 7. Check stopping condition (max iterations or convergence). 8. If stopping condition met: Return best solution (optimized hyperparameters, accuracy). 9. Else: Continue to next iteration. 10. t = t + 1. 11. End while. 12. Return best optimized solution. |

4. Experiments

4.1. Software and Hardware

All experiments were carried out using Python 3.12.12, TensorFlow 2.19.0, Keras 3.10.0, NumPy 2.0.2, scikit-learn 1.6.1, and pandas 2.2.2. The models received training in a high-memory runtime environment on Google Colab to meet the computational demands. This setup provided access to an NVIDIA L4 GPU with 24 GB of dedicated memory and was supported by a virtual machine equipped with roughly 53 GB of system RAM and 112 GB of disk storage.

4.2. Simulation and Discussion

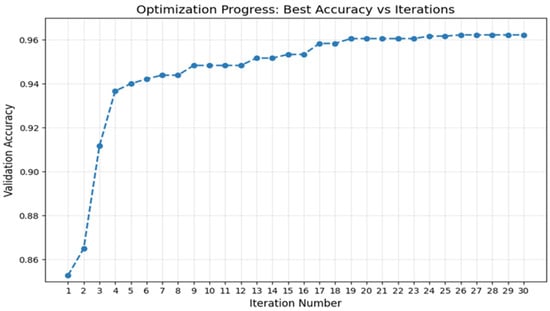

In this research, the hyperparameters of the suggested Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for IoT network intrusion detection have been optimized through a hybrid metaheuristic strategy by the integration of Red Fox Optimization (RFO) and Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) algorithms. Through obtaining an equilibrium point between exploitation and exploration, the hybrid algorithm’s parameter settings were tuned as follows: 50 population size, 30 iteration max, and a parameter linearly decreasing from 2 to 0 with each following iteration, and a probability of escape of 0.2. As can be seen in Figure 3, the minimum fitness value of the hybrid algorithm, which was defined as the negative validation accuracy, was varied across iterations, converging to the optimal value. The optimal highest particle fitness value achieved by FW-CNN Hybrid Algorithm was 0.9622222185134888 (validation accuracy of 96.22%) using iterative optimization. The optimal hyperparameters are represented in Table 7. The parameters were designed into a CNN model of one convolutional layer and max-pooling, followed by a dropout layer, two fully connected layers, and an output layer designed for multi-class classification of IoT attacks. To speed up the training procedure, an early stopping criterion was also used, stopping training and storing the best model when the loss on the validation set failed to drop for five epochs in a row.

Figure 3.

FW-CNN Validation Accuracy.

Table 7.

CNN’s optimal hyperparameters utilizing the FW-CNN optimization algorithm.

The proposed FW-CNN model was simulated and its performance compared to a baseline Feedforward Neural Network (FNN). The two models were both trained for six epochs, and their training accuracy, validation accuracy, and validation loss at every epoch were noted. The proposed model was optimized using the hybrid Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) and Red Fox Optimizer (RFO), whereas the FNN utilized manually selected hyperparameters.

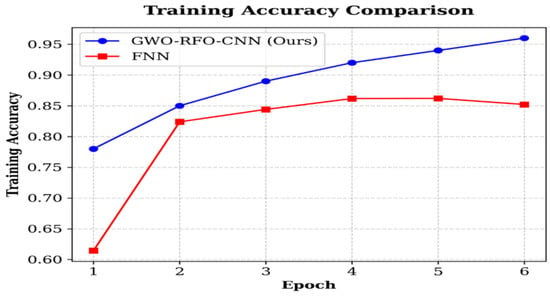

4.2.1. Training Accuracy

As shown in Figure 4, the training accuracy of the proposed FW-CNN increased steadily from 78% in the first epoch to 96% in the sixth epoch. In contrast, the FNN only achieved 85% accuracy and stabilized after the third epoch. This implies that not only does the hybrid-optimized CNN learn faster, but it continues to enhance the training accuracy consistently as well.

Figure 4.

Accuracy training sets for the FW-CNN and FNN algorithms.

4.2.2. Validation Accuracy

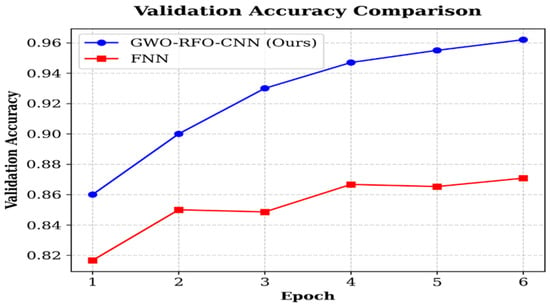

The validation accuracy comparison is illustrated in Figure 5. The proposed model performed better than the FNN consistently, with 96.2% at epoch 6 compared to 87% for the FNN. The gap grew as the epochs progressed, indicating the greater generalization ability of the FW-CNN on unseen data.

Figure 5.

Accuracy validation sets for the FW-CNN and FNN algorithms.

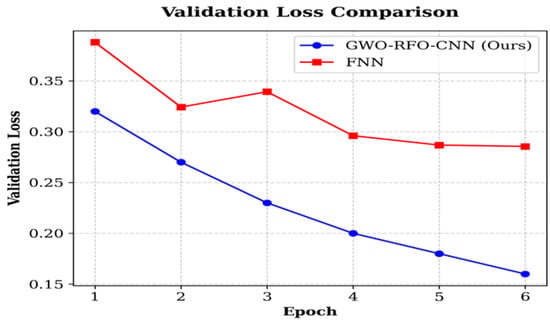

4.2.3. Validation Loss

Figure 6 illustrates the trend of validation loss. The FW-CNN achieved a steady decline of validation loss from 0.32 to 0.16 across epochs, whereas the FNN only declined to around ~0.28 and became stagnant. The lower validation loss of the proposed model confirms its ability not to overfit yet achieve stable convergence.

Figure 6.

Validation of the loss function of the FW-CNN and FNN algorithms.

In brief, the simulation results graphically show that FW-CNN surpasses the baseline FNN in optimization, learning efficiency, and generalization.

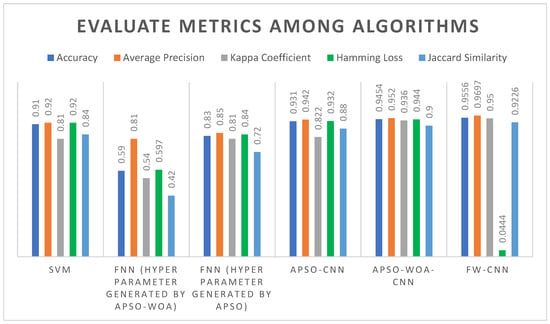

4.3. Results and Performance Analysis

To compare the performance of the proposed FW-CNN model with models proposed by Bahaa et al. [54], who utilized the N-BaIoT dataset and a hybrid optimization approach to tune the CNN hyperparameters, we followed five evaluation metrics: accuracy, average precision, kappa coefficient, Hamming loss, and Jaccard similarity coefficient. Accuracy reflects overall classification accuracy, average precision accounts for weighted class precision, Kappa coefficient measures greater than chance agreement, Hamming loss indicates the percentage of misclassified labels, and Jaccard similarity indicates the intersection of predicted and actual labels.

The simulation employed a dataset of 90,000 examples with 115 network traffic features for different types of IoT devices having benign and malicious instances of botnet attacks [31]. The data was preprocessed with MinMaxScaler to normalize features to range [0,1], and then divided into training (72,000 examples) and validation (18,000 examples) sets. Preprocessing was performed with filling missing values using mean imputation and encoding labels for multi-class classification using one-hot encoding. The last model was evaluated on a test set, The performance metrics in Table 8 are as follows:

Table 8.

Results of the proposed model according to evaluation metrics.

The performance indicators are given in Table 5. The top-performing FW-CNN had the maximum accuracy (95.56%), mean precision (0.9697), and Kappa score (0.95) with the lowest Hamming loss (0.0444). Its Jaccard similarity index was 0.9226, again establishing high classification stability. The baseline FNN, however, achieved a mere 83% accuracy, a Kappa score of 0.81, and considerably higher Hamming loss (0.84) indicating lower predictive reliability. APSO-CNN and APSO-WOA-CNN also outperformed the FNN but were still inferior to the proposed hybrid model. The SVM baseline was 91%, which was still lower than that of FW-CNN (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Compare and Assess Algorithms Metrics.

The total superiority of the FW-CNN across epoch-wise comparisons (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6) and final evaluation metrics (Table 9) demonstrates the strength of the combination of GWO and RFO in hyperparameter optimization. The results confirm that the developed model produces superior, stable, and generalizable IoT network intrusion detection solutions compared to conventional and meta-heuristic-optimized baselines.

Table 9.

Algorithm results based on evaluation matrices.

4.4. Study Limitations

There are limits to our research article. The computational expense of the 30-iteration optimization procedure, which takes a long time to improve the hyperparameters of the convolutional neural network.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we propose FW-CNN, a novel hybrid metaheuristic-driven tuning mechanism to enhance 1D-CNN-based intrusion detection for IoT environments. The proposed framework attains a balanced search dynamic that reduces premature convergence and improves generalization by incorporating the Grey Wolf Optimizer’s exploitation behaviour along with the Red Fox Optimizer’s adaptive exploration capability. This synergy yielded superior hyperparameter adaptation capable of detecting diverse IoT attacks—especially DDoS and botnet traffic—with much better reliability.

The experimental evaluation demonstrated that FW-CNN consistently outperformed the baseline models in all phases of training and validation. At the sixth epoch, the model achieved 96.2% validation accuracy with 0.16 loss, in comparison with the 87% and 0.29 for the conventional FNN. Measured against full-scale evaluation metrics, the FW-CNN achieved overall accuracy of 95.56%, 0.9697 precision, 0.95 Kappa, 0.9226 Jaccard similarity, and considerably reduced the Hamming loss to 0.0444, outperforming APSO-CNN, APSO-WOA-CNN, and FNN. This indeed confirms that the hybrid optimization design is effective in building robust and scalable IDS solutions for IoT ecosystems.

Future work will concentrate on extending FW-CNN by the use of other metaheuristics, such as Ant Colony Optimization, Artificial Bee Colony, and Genetic Algorithms, aiming at further robustness in case of more dynamic attack conditions. Additionally, the reduction in computational overhead will remain an important priority to enable real-time deployment on resource-limited edge platforms. Another direction involves integrating the optimized IDS into a DevSecOps-driven smart monitoring pipeline that enables automated response and continuous threat mitigation in IoT environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B.E. and A.S.Y.; methodology, E.B.E.; software, E.B.E.; validation, A.S.Y.; formal analysis, E.B.E. and A.S.Y.; investigation, E.B.E.; writing—original draft preparation, E.B.E.; writing—review and editing, A.S.Y. and H.F.; supervision, H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets used and analyzed during this study are publicly available. The experiments were conducted using the N-BaIoT dataset, which can be accessed at https://ieee-dataport.org/documents/n-baiot, accessed on 1 January 2025 and all derived data and model configurations are described in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Fourth Industrial Revolution. World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/focus/fourth-industrial-revolution/ (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Fallahpour, A.; Wong, K.Y.; Rajoo, S.; Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Antucheviciene, J.; Nayeri, S. An integrated approach for a sustainable supplier selection based on Industry 4.0 concept. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, N.A.; Parekh, D.A.; Shah, Y.A.; Mangrulkar, R. In Cyber Security and Digital Forensics, Ghonge, M.M., Pramanik, S., Mangrulkar, R., Le, D., Eds.; 4S Framework: A Practical CPS Design Security Assessment & Benchmarking Framework, 1st ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 163–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaran, M. The Internet Of Things: Limitless Opportunities For Business And Society. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 831–841. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, F.; González-Prieto, Á.; Bobadilla, J.; Gutiérrez, A. Collaborative Filtering to Predict Sensor Array Values in Large IoT Networks. Sensors 2020, 20, 4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bout, E.; Loscri, V.; Gallais, A. Evolution of IoT Security: The Era of Smart Attacks. IEEE Internet Things M. 2022, 5, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memos, V.A.; Psannis, K.E. NFV-Based Scheme for Effective Protection against Bot Attacks in AI-Enabled IoT. IEEE Internet Things M. 2022, 5, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symantec Internet Security Threat Report. Volume 24: Executive Summary. 2019. Available online: https://docs.broadcom.com/doc/istr-24-2019-en (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Alsheikh, M.; Konieczny, L.; Prater, M.; Smith, G.; Uludag, S. The State of IoT Security: Unequivocal Appeal to Cybercriminals, Onerous to Defenders. IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag. 2022, 11, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmcdouga. A Perfect Storm: The Security Challenges of Coronavirus Threats and Mass Remote Working. Check Point Blog 2020. Available online: https://blog.checkpoint.com/security/a-perfect-storm-the-security-challenges-of-coronavirus-threats-and-mass-remote-working/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Raponi, S.; Sciancalepore, S.; Oligeri, G.; Di Pietro, R. Road Traffic Poisoning of Navigation Apps: Threats and Countermeasures. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2022, 20, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, G.; Mehmood, A.; Carsten, M.; Epiphaniou, G.; Lloret, J. Safety, Security and Privacy in Machine Learning Based Internet of Things. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2022, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hireche, R.; Mansouri, H.; Pathan, A.-S.K. Security and Privacy Management in Internet of Medical Things (IoMT): A Synthesis. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2022, 2, 640–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, A.; Ghayoor, F.; Waseem, M.; Fahad, S.; Traore, I. A Survey on IoT-Enabled Smart Grids: Emerging, Applications, Challenges, and Outlook. Energies 2022, 15, 6984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zuo, W.; Yang, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. Outsourced privacy-preserving anomaly detection in time series of multi-party. China Commun. 2022, 19, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Wang, S.; Shahzad, M.; Hu, J. An IoT-Oriented Privacy-Preserving Fingerprint Authentication System. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 11760–11771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, L.; Xu, C. BPAF: Blockchain-Enabled Reliable and Privacy-Preserving Authentication for Fog-Based IoT Devices. IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag. 2022, 11, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.; Huber, B.; Kandah, F. Towards feasibility of Deep-Learning based Intrusion Detection System for IoT Embedded Devices. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 19th Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 8–11 January 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 947–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.; Fraihat, S.; Salameh, K.; Al Redhaei, A. Examining the Suitability of NetFlow Features in Detecting IoT Network Intrusions. Sensors 2022, 22, 6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alani, M.M.; Miri, A. Towards an Explainable Universal Feature Set for IoT Intrusion Detection. Sensors 2022, 22, 5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-rawashdeh, M.; Keikhosrokiani, P.; Belaton, B.; Alawida, M.; Zwiri, A. IoT Adoption and Application for Smart Healthcare: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitenbacher, D.; Homoliak, I.; Aung, Y.L.; Elovici, Y.; Tippenhauer, N.O. HADES-IoT: A Practical and Effective Host-Based Anomaly Detection System for IoT Devices (Extended Version). IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 9640–9658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, V.; Choraś, M.; Pawlicki, M.; Kozik, R. A Deep Learning Ensemble for Network Anomaly and Cyber-Attack Detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthanna, M.S.A.; Alkanhel, R.; Muthanna, A.; Rafiq, A.; Abdullah, W.A.M. Towards SDN-Enabled, Intelligent Intrusion Detection System for Internet of Things (IoT). IEEE Access 2022, 10, 22756–22768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Bu, B.; Zhang, W.; Li, X. An Intrusion Detection Method Based on Machine Learning and State Observer for Train-Ground Communication Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 2022, 23, 6608–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Moustafa, N.; Hawash, H.; Razzak, I.; Sallam, K.M.; Elkomy, O.M. Federated Intrusion Detection in Blockchain-Based Smart Transportation Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 2022, 23, 2523–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aribisala, A.; Khan, M.S.; Husari, G. Feed-Forward Intrusion Detection and Classification on a Smart Grid Network. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 12th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26–29 January 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efe, A.; Abaci, İ.N. Comparison of the Host Based Intrusion Detection Systems and Network Based Intrusion Detection Systems. Celal Bayar Üniversitesi Fen Bilim. Derg. 2022, 18, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahaa, A.; Abdelaziz, A.; Sayed, A.; Elfangary, L.; Fahmy, H. Monitoring Real Time Security Attacks for IoT Systems Using DevSecOps: A Systematic Literature Review. Information 2021, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahsi, H.; Nomm, S.; La Torre, F.B. Dimensionality Reduction for Machine Learning Based IoT Botnet Detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 15th International Conference on Control, Automation, Robotics and Vision (ICARCV), Singapore, 18–21 November 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1857–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meidan, Y.; Bohadana, M.; Mathov, Y.; Mirsky, Y.; Breitenbacher, D.; Shabtai, A.; Elovici, Y. N-BaIoT: Network-based Detection of IoT Botnet Attacks Using Deep Autoencoders. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2018, 17, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattari, F.; Farooqi, A.H.; Qadir, Z.; Raza, B.; Nazari, H.; Almutiry, M. A Hybrid Deep Learning Approach for Bottleneck Detection in IoT. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 77039–77053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Ngo, Q.-D.; Nguyen, H.-T.; Nguyen, G.L. An Advanced Computing Approach for IoT-Botnet Detection in Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2022, 18, 8298–8306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Firouzi, F.; Chakrabarty, K.; Elbogen, E.B. A Resilient and Hierarchical IoT-Based Solution for Stress Monitoring in Everyday Settings. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 10224–10243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalipour, A.; Murali, S. A Taxonomy of Machine-Learning-Based Intrusion Detection Systems for the Internet of Things: A Survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 9444–9466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liang, W.; Li, W.; Yan, K.; Shimizu, S.; Wang, K.I.-K. Hierarchical Adversarial Attacks Against Graph-Neural-Network-Based IoT Network Intrusion Detection System. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 9310–9319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaeidy, A.A.; Jamalipour, A.; Munasinghe, K.S. A Hybrid Deep Learning Approach for Replay and DDoS Attack Detection in a Smart City. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 154864–154875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Qiao, X.; Dustdar, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. Toward Decentralized and Collaborative Deep Learning Inference for Intelligent IoT Devices. IEEE Netw. 2022, 36, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, G.; Ding, H.; Mumtaz, S.; Guizani, M. Blockchain and Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Secure Cloud-Edge-End Collaboration in Power IoT. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2022, 29, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Gupta, G.P.; Tripathi, R. PEFL: Deep Privacy-Encoding-Based Federated Learning Framework for Smart Agriculture. IEEE Micro 2022, 42, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Tjortjis, C. Machine Learning based IoT-BotNet Attack Detection Using Real-time Heterogeneous Data. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Energy Technologies (ICECET), Prague, Czech Republic, 20–22 July 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.; Ye, D.; Tariq, A.; Asad, M.; Hanif, M.; Ndzi, D.; Chelloug, S.A.; Elaziz, M.A.; Al-Qaness, M.A.A.; Jilani, S.F. Adaptive Machine Learning Based Distributed Denial-of-Services Attacks Detection and Mitigation System for SDN-Enabled IoT. Sensors 2022, 22, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan, M.; Riaz, Q.; Bilal, M.A.; Shahzad, M.K.; Jabeen, H.; Haider, S.A.; Rahim, A. Protocol-Based Deep Intrusion Detection for DoS and DDoS Attacks Using UNSW-NB15 and Bot-IoT Data-Sets. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 2269–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alothman, Z.; Alkasassbeh, M.; Al-Haj Baddar, S. An efficient approach to detect IoT botnet attacks using machine learning. J. High Speed Netw. 2020, 26, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, S.I.; Ande, R.; Adebisi, B.; Gui, G.; Hammoudeh, M.; Jogunola, O. Federated Deep Learning for Zero-Day Botnet Attack Detection in IoT-Edge Devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 3930–3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booij, T.M.; Chiscop, I.; Meeuwissen, E.; Moustafa, N.; Hartog, F.T.H.D. ToN_IoT: The Role of Heterogeneity and the Need for Standardization of Features and Attack Types in IoT Network Intrusion Data Sets. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huancayo Ramos, K.S.; Sotelo Monge, M.A.; Maestre Vidal, J. Benchmark-Based Reference Model for Evaluating Botnet Detection Tools Driven by Traffic-Flow Analytics. Sensors 2020, 20, 4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, S.Y.; Ozkurt, N. Convolutional Neural Network Hyperparameter Tuning with Adam Optimizer for ECG Classification. In Proceedings of the 2020 Innovations in Intelligent Systems and Applications Conference (ASYU), Istanbul, Turkey, 15–17 October 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Yuan, S.; Chi, R.; Chang, L.; Zhao, L. Genetic Optimization Method of Pantograph and Catenary Comprehensive Monitor Status Prediction Model Based on Adadelta Deep Neural Network. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 23210–23221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, C.; Lin, Q. Distributed Evolution Strategies for Black-box Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.04450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey Wolf Optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The Whale Optimization Algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, X.; Fan, Y.; Fang, Z.; Cao, L.; Xiong, N.N.; Yang, D.; Li, X. A novel IoT network intrusion detection approach based on Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization Convolutional Neural Network. Inf. Sci. 2021, 568, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahaa, A.; Sayed, A.; Elfangary, L.; Fahmy, H. A novel hybrid optimization enabled robust CNN algorithm for an IoT network intrusion detection approach. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0278493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzaqebah, A.; Aljarah, I.; Al-Kadi, O.; Damaševičius, R. A Modified Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithm for an Intrusion Detection System. Mathematics 2022, 10, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokku, G.; Reddy, G.H.; Prasad, M.N.G. OPFaceNet: OPtimized Face Recognition Network for noise and occlusion affected face images using Hyperparameters tuned Convolutional Neural Network. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 117, 108365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Połap, D.; Woźniak, M. Red fox optimization algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 166, 114107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, N.; Liu, Z.; Shaver, A.; Esterline, A.; Gokaraju, B.; Roy, K. Secure Cyber Defense: An Analysis of Network Intrusion-Based Dataset CCD-IDSv1 with Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models. Electronics 2021, 10, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Ngadi, A.B.; Sharif, J.M.; Hussain, S.; Uddin, M.; Rathore, M.S.; Iqbal, J.; Abdelhaq, M.; Alsaqour, R.; Ullah, S.S.; et al. Network Threat Detection Using Machine/Deep Learning in SDN-Based Platforms: A Comprehensive Analysis of State-of-the-Art Solutions, Discussion, Challenges, and Future Research Direction. Sensors 2022, 22, 7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoumin, G.; Rawat, D.B.; Rahman, A. On the Performance of Machine Learning Models for Anomaly-Based Intelligent Intrusion Detection Systems for the Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 4280–4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-H.; Wang, P.; Chao, K.-M.; Lin, H.-C.; Yang, Z.-Y.; Lai, Y.-H. Deep-Learning Model Selection and Parameter Estimation from a Wind Power Farm in Taiwan. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L. (IoT) Network intrusion detection system using optimization algorithms. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wafi, M.N.A.Z. CNN-RGU Hyperparameter Tuning for Improving Cybersecurity Intrusion Detection in Industrial IOT Environment. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. Manag. 2025, 10, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Reshi, A.A.; Shafi, S.; Aljubayri, I. An adaptive hybrid framework for IIoT intrusion detection using neural networks and feature optimization using genetic algorithms. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagu, A.; Gill, N.S.; Gulia, P.; Alduaiji, N.; Shukla, P.K.; Shah, M.A. Advances to IoT security using a GRU-CNN deep learning model trained on SUCMO algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alashjaee, A.M. Deep learning for network security: An Attention-CNN-LSTM model for accurate intrusion detection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankalaki, S.; Thippeswamy, M.N. Optimized Convolutional Neural Network Using Hierarchical Particle Swarm Optimization for Sensor Based Human Activity Recognition. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrag, M.A.; Shu, L.; Djallel, H.; Choo, K.-K.R. Deep Learning-Based Intrusion Detection for Distributed Denial of Service Attack in Agriculture 4.0. Electronics 2021, 10, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, X.-Y.; Zhang, H.; Xiong, L.-D.; Lei, H.; Deng, S.-H. Hyperparameter Optimization for Machine Learning Models Based on Bayesian Optimization. J. Electron. Sci. Technol. 2019, 17, 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Elmasry, W.; Akbulut, A.; Zaim, A.H. Evolving deep learning architectures for network intrusion detection using a double PSO metaheuristic. Comput. Netw. 2020, 168, 107042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]