PLSSEM Comparison Study of Mobile Payment Usage in Hong Kong and Mainland China: Factors Affecting the Popularity of Mobile Payment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Apply Familiarity as a Variable

2.2. Apply Perceived Security as a Variable

2.3. Facilitating Factors Influencing User Acceptance

- (a)

- What are the factors influencing users’ actual use of a payment system, and how do they interact with each other?

2.4. Cultural and Regional Influence

- (b)

- How are TAM factors different between mainland China and Hong Kong?

- (c)

- What should be performed to improve mobile payment adoption in Hong Kong?

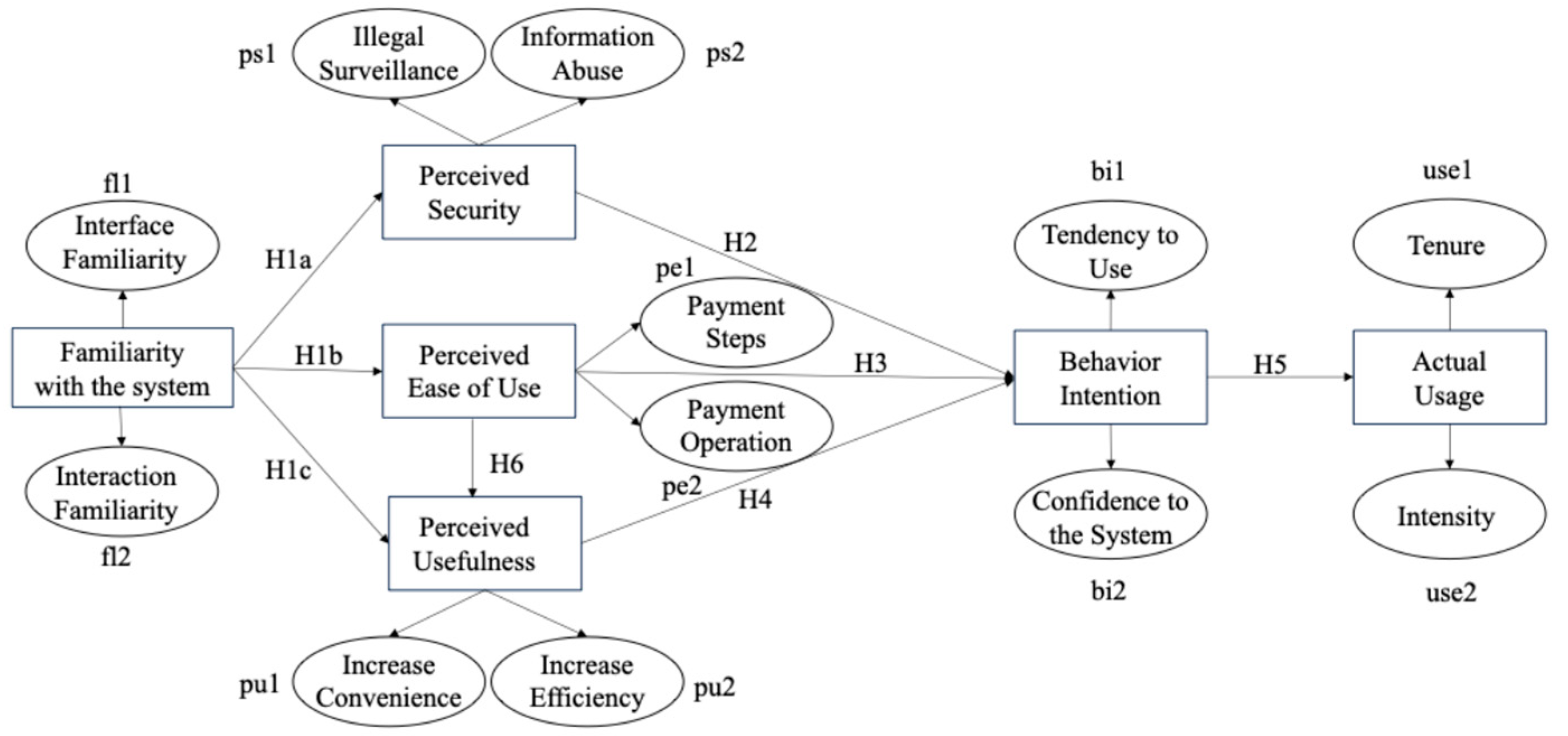

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

3.1.1. System (Sys)

3.1.2. Perceived Ease of Use (PE)

3.1.3. Perceived Usefulness (PU)

3.1.4. Behavior Intention (BI)

3.2. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLSSEM)

3.2.1. Factor Settings

3.2.2. Application Procedure

4. Hypotheses

5. Methodology

5.1. Subjects and Procedure

5.2. Reliability Analysis

5.3. Questionnaires

6. Results

6.1. PLSSEM Analysis

6.2. Complementary Results

7. Discussion

- Simplify the payment process. Make the payment steps easy to remember and understand. Make the user interface impressionable and function-highlighted;

- Disseminate your product. Interface with as many Hong Kong local merchants as possible so that Hong Kong citizens have chances to pay with your product. Integrate with the merchants’ current devices [44];

- Offer a little incentive like shopping coupons or credits. Reduce transaction costs;

- Enhance data security. Implement multiple information security methods to ensure users’ money security and customers’ rights. Cooperate with the Hong Kong government to stipulate your security and confidentiality laws according to Hong Kong’s local laws and clarify your security laws with Hong Kong users.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Overall Operation of the Payment System in 2023. Available online: https://www.pcac.org.cn/eportal/ui?pageId=598168&articleKey=620383&columnId=595055 (accessed on 9 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Penetration Rate of Leading Payment Methods in Hong Kong in 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1421057/hong-kong-leading-payment-methods/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Raina, V. Overview of Mobile Payment: Technologies and Security. Electron. Paym. Syst. Compet. Advant. E-Commer. 2014, 1, 180–217. [Google Scholar]

- The Digital Payments Landscape in Hong Kong. Available online: https://www.doc88.com/p-5798771524681.html (accessed on 9 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Shah, M.H. Mobile Working: Technologies and Business Strategies, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Edu, A.S. Paths to digital mobile payment platforms acceptance and usage: A topology for digital enthusiast consumers. Telemat. Inform. Rep. 2024, 15, 100–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2025 Global Payment Report. Available online: https://www.hkdca.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/gpr-2025-worldpay.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Wang Xun: How Does Mobile Payment Change Economics and Finance. Available online: http://nsd.pku.edu.cn/sylm/gd/502518.htm (accessed on 9 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.A.; Nelson, R.R.; Todd, P.A. Perceived Usefulness, Ease of Use, and Usage of Information Technology: A Replication. MIS Q. 1992, 16, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gahtani, S.S. Empirical investigation of e-learning acceptance and assimilation: A structural equation model. Appl. Comput. Inform. 2016, 12, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Hillol, B. Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a Research Agenda on Interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathema, N.; Shannon, D.; Ross, M. Expanding the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to examine faculty use of Learning Management Systems (LMS). J. Online Learn. Teach. 2015, 11, 210–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.; Kilders, V.; Widmar, N.; Ebner, P. Consumer acceptance of bacteriophage technology for microbial control. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupey, E.; Irwin, J.R.; Payne, J.W. Product Category Familiarity and Preference Construction. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W. Trust and TAM in Online Shopping: An Integrated Model. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, M.; Mattord, H. Principles of Information Security, 7th ed.; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2022; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Linck, K.; Pousttchi, K.; Wiedemann, D. Security issues in mobile payment from the customer viewpoint. In Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Information Systems, Tel Aviv, Israel, 9–11 June 2014; pp. 1085–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Pietro, L.D.; Mugion, R.G.; Mattia, G.; Renzi, M.F.; Toni, M. The integrated model on mobile payment acceptance (IMMPA): An empirical application to public transport. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2015, 56, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.; Mo, W. A Study of Consumer Intention of Mobile Payment in Hong Kong, Based on Perceived Risk, Perceived Trust, Perceived Security and Technological Acceptance Model. J. Adv. Manag. Sci. 2019, 7, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, R.; Zanna, M. Direct Experience and Attitude-Behavior Consistency. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 14, 161–202. [Google Scholar]

- Doney, P.M.; Cannon, J.P. An Examination of the Nature of Trust in Buyer–Seller Relationships. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.M.; Shin, B.; Lee, H.G. Understanding dynamics between initial trust and usage intentions of mobile banking. Inf. Syst. J. 2010, 19, 283–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narteh, B.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Amoh, S. Customer behavioural intentions towards mobile money services adoption in Ghana. Serv. Ind. J. 2017, 37, 426–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.W. Bon appétit for apps: Young American consumers’ acceptance of mobile applications. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2013, 53, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Straub, D.; Keil, M.; Brenner, W. Testing the technology acceptance model across cultures: A three country study. Inf. Manag. 1997, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saafi, M.A.; Gordillo, V.; Alharbi, O.; Mitschler, M. Investigating the Future of Freight Transport Low Carbon Technologies Market Acceptance across Different Regions. Energies 2024, 17, 4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technology Acceptance Model: A Review. Available online: https://open.ncl.ac.uk/theories/1/technology-acceptance-model (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: System characteristics, user perceptions and behavioral impacts. Int. J. Man-Mach. Stud. 1993, 38, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, S.; Mehmetoglu, M. Plssem: A Stata Package for Structural Equation Modeling with Partial Least Squares. J. Stat. Softw. 2019, 88, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 1st ed.; Sage: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D. E-commerce: The Role of Familiarity and Trust. Omega 2020, 28, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schierz, P.G.; Schilke, O.; Wirtz, B.W. Understanding consumer acceptance of mobile payment services: An empirical analysis. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. The assessment of reliability. Psychom. Theory 1994, 3, 248–292. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, P.; Neto, L.B.F.; Muñoz-Gallego, P.A.; Laukkanen, T. Mobile banking rollout in emerging markets: Evidence from Brazil. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2010, 28, 342–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G.; Evaristo, J.; Straub, D. Culture and Consumer Responses to Web Download Time: A Four-Continent Study of Mono and Polychronism. Eng. Manag. 2003, 50, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, G. PLS Path Modeling with R, 1st ed.; Trowchez Editions: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2013; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- What Are the Disadvantages of Hierarchical Regression Compared to SEM? Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/post/What-are-the-disadvantages-of-hierarchical-regression-compared-to-SEM/55c060b4614325a85e8b45a8/citation/download (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Kimes, S.E.; Collier, J. Customer-facing payment technology in the US restaurant industry. Cornell Hosp. Rep. 2014, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

| Label | Items | CA | AVE HK/Mainland | Number of Items | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FL | Familiarity | 0.862 | 0.860/0.939 | 2 | [35] |

| PE | Ease | 0.942 | 0.947/0.945 | 2 | [36] |

| PU | PU | 0.935 | 0.939/0.905 | 2 | [36] |

| PS | Security | 0.848 | 0.757/0.902 | 2 | [36] |

| BI | Intention | 0.899 | 0.885/0.838 | 2 | [12] |

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level of education | Primary school | 1 | 0.87% |

| High school | 9 | 7.83% | |

| Bachelor | 47 | 40.87% | |

| Post-graduate | 55 | 47.83% | |

| Doctor | 3 | 2.61% | |

| Current place of residence | Mainland | 65 | 56.52% |

| Hong Kong | 50 | 43.48% |

| Hong Kong | |||||

| Type | R_squared | R_squared_adj | Block_communality | Mean_redundancy | |

| BI | Endogenous | 0.636984 | 0.602951 | 0.884737 | 0.563564 |

| FL | Exogenous | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.859630 | 0.000000 |

| PE | Endogenous | 0.578308 | 0.565905 | 0.946911 | 0.547607 |

| PS | Endogenous | 0.112693 | 0.086596 | 0.757478 | 0.085363 |

| PU | Endogenous | 0.526480 | 0.497782 | 0.938838 | 0.494279 |

| USE | Endogenous | 0.641300 | 0.630750 | 0.571157 | 0.366283 |

| Mainland | |||||

| Type | R_squared | R_squared_adj | Block_communality | Mean_redundancy | |

| BI | Endogenous | 0.532406 | 0.505430 | 0.838408 | 0.446373 |

| FL | Exogenous | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.939104 | 0.000000 |

| PE | Endogenous | 0.510849 | 0.501790 | 0.945439 | 0.482976 |

| PS | Endogenous | 0.054275 | 0.036761 | 0.901713 | 0.048940 |

| PU | Endogenous | 0.534106 | 0.516526 | 0.905408 | 0.483584 |

| USE | Endogenous | 0.043457 | 0.025743 | 0.549891 | 0.023896 |

| Hong Kong | ||||||

| FL | PS | PE | PU | BI | USE | |

| fl1 | 0.920715 | 0.355244 | 0.670833 | 0.552143 | 0.466246 | 0.307172 |

| fl2 | 0.933565 | 0.271000 | 0.736890 | 0.653236 | 0.584711 | 0.562607 |

| ps1 | 0.335213 | 0.917118 | 0.455058 | 0.299466 | 0.375997 | 0.334447 |

| ps2 | 0.236403 | 0.820885 | 0.232932 | 0.108384 | 0.260256 | 0.040772 |

| pe1 | 0.722251 | 0.429338 | 0.974339 | 0.735629 | 0.557203 | 0.515607 |

| pe2 | 0.758632 | 0.376167 | 0.971847 | 0.629137 | 0.531451 | 0.513998 |

| pu1 | 0.650611 | 0.249734 | 0.702988 | 0.969508 | 0.742747 | 0.706780 |

| pu2 | 0.612892 | 0.238007 | 0.657931 | 0.968365 | 0.759326 | 0.765387 |

| bi1 | 0.549963 | 0.323864 | 0.479203 | 0.708205 | 0.941990 | 0.793391 |

| bi2 | 0.520737 | 0.380819 | 0.574739 | 0.750293 | 0.939217 | 0.712209 |

| use1 | 0.365330 | 0.105924 | 0.256279 | 0.391452 | 0.262953 | 0.474311 |

| use2 | 0.408973 | 0.236397 | 0.504958 | 0.717134 | 0.805172 | 0.957780 |

| Mainland | ||||||

| FL | PS | PE | PU | BI | USE | |

| fl1 | 0.967718 | 0.220042 | 0.692653 | 0.569348 | 0.406049 | 0.171784 |

| fl2 | 0.970428 | 0.231257 | 0.692653 | 0.629162 | 0.457385 | 0.093576 |

| ps1 | 0.228871 | 0.955266 | 0.347866 | 0.289745 | 0.615009 | 0.051502 |

| ps2 | 0.212830 | 0.943871 | 0.338219 | 0.202484 | 0.547648 | 0.196598 |

| pe1 | 0.686779 | 0.357545 | 0.970638 | 0.677690 | 0.444782 | 0.225568 |

| pe2 | 0.702739 | 0.345699 | 0.974033 | 0.710163 | 0.525122 | 0.258234 |

| pu1 | 0.585485 | 0.264697 | 0.759950 | 0.957902 | 0.520026 | 0.005391 |

| pu2 | 0.593566 | 0.231257 | 0.588588 | 0.945114 | 0.505888 | −0.110704 |

| bi1 | 0.434044 | 0.563181 | 0.414436 | 0.472486 | 0.917088 | 0.258681 |

| bi2 | 0.382396 | 0.561152 | 0.501888 | 0.515576 | 0.914201 | 0.121961 |

| use1 | −0.175436 | −0.115988 | −0.271709 | 0.049159 | −0.181451 | −0.848985 |

| use2 | −0.005639 | 0.064837 | 0.063875 | −0.023368 | 0.121672 | 0.615635 |

| Hong Kong | ||||||

| FL | PS | PE | PU | BI | USE | |

| FL | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| PS | 0.335698 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| PE | 0.760466 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| PU | 0.279742 | 0.000000 | 0.489747 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| BI | 0.000000 | 0.208447 | −0.067758 | 0.770157 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| USE | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.800812 | 0.000000 |

| Mainland | ||||||

| FL | PS | PE | PU | BI | USE | |

| FL | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| PS | 0.232969 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| PE | 0.714737 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| PU | 0.222030 | 0.000000 | 0.555444 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| BI | 0.000000 | 0.496858 | 0.057279 | 0.368444 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| USE | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.208463 | 0.000000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tse, W.; Liu, P.; Ouyang, Z.; Li, M.; Wen, H. PLSSEM Comparison Study of Mobile Payment Usage in Hong Kong and Mainland China: Factors Affecting the Popularity of Mobile Payment. Information 2025, 16, 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121104

Tse W, Liu P, Ouyang Z, Li M, Wen H. PLSSEM Comparison Study of Mobile Payment Usage in Hong Kong and Mainland China: Factors Affecting the Popularity of Mobile Payment. Information. 2025; 16(12):1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121104

Chicago/Turabian StyleTse, Woonkwan, Pulei Liu, Zongbin Ouyang, Mingshan Li, and Haoming Wen. 2025. "PLSSEM Comparison Study of Mobile Payment Usage in Hong Kong and Mainland China: Factors Affecting the Popularity of Mobile Payment" Information 16, no. 12: 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121104

APA StyleTse, W., Liu, P., Ouyang, Z., Li, M., & Wen, H. (2025). PLSSEM Comparison Study of Mobile Payment Usage in Hong Kong and Mainland China: Factors Affecting the Popularity of Mobile Payment. Information, 16(12), 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121104