1. Introduction

In recent years, skin cancer has become one of the most prevalent and serious diseases affecting human health worldwide. According to incomplete statistics, although the mortality rate of malignant skin cancer remains high, early diagnosis can reduce mortality in 95% of patients, which can improve the survival rate by an average of 5 years [

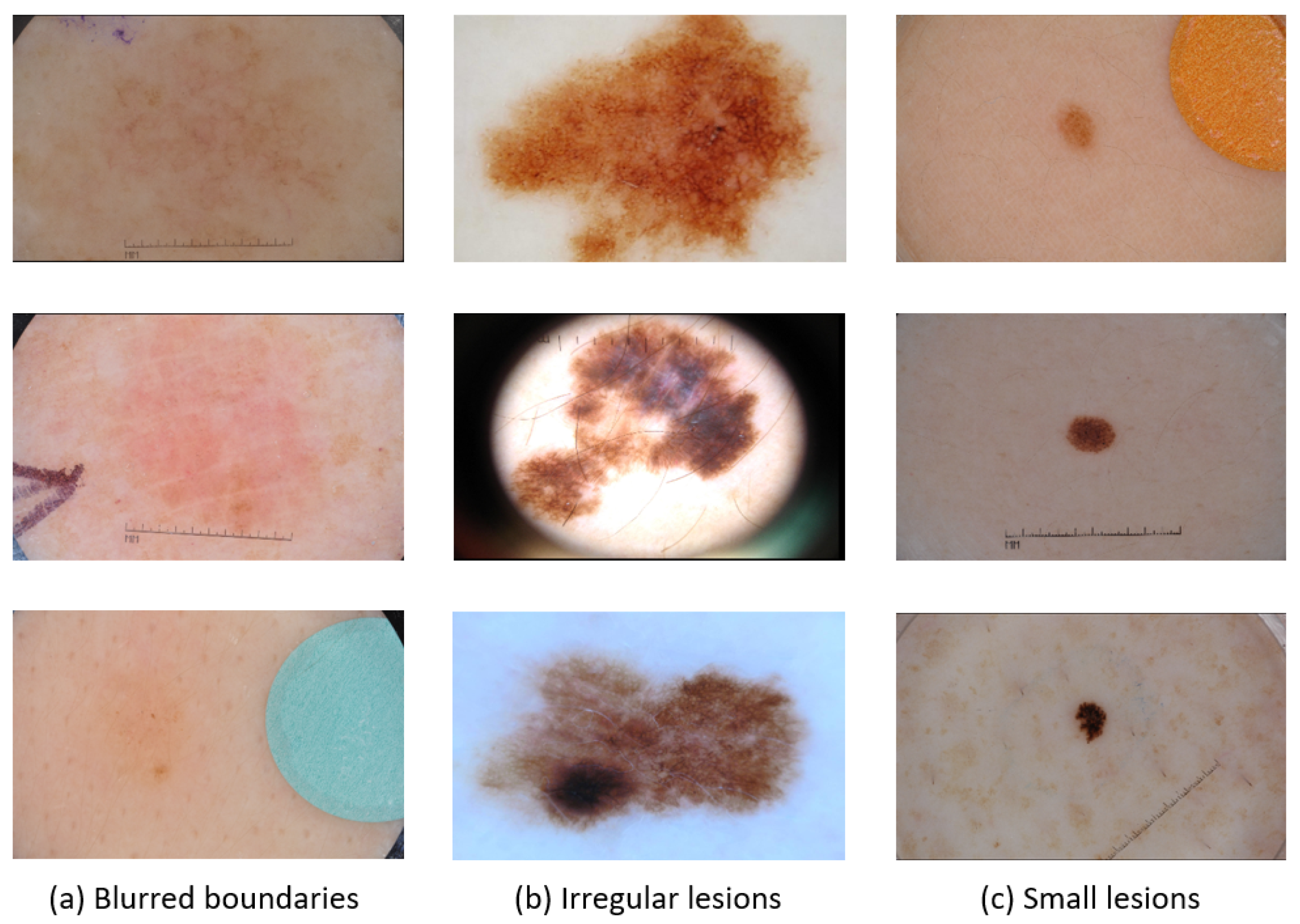

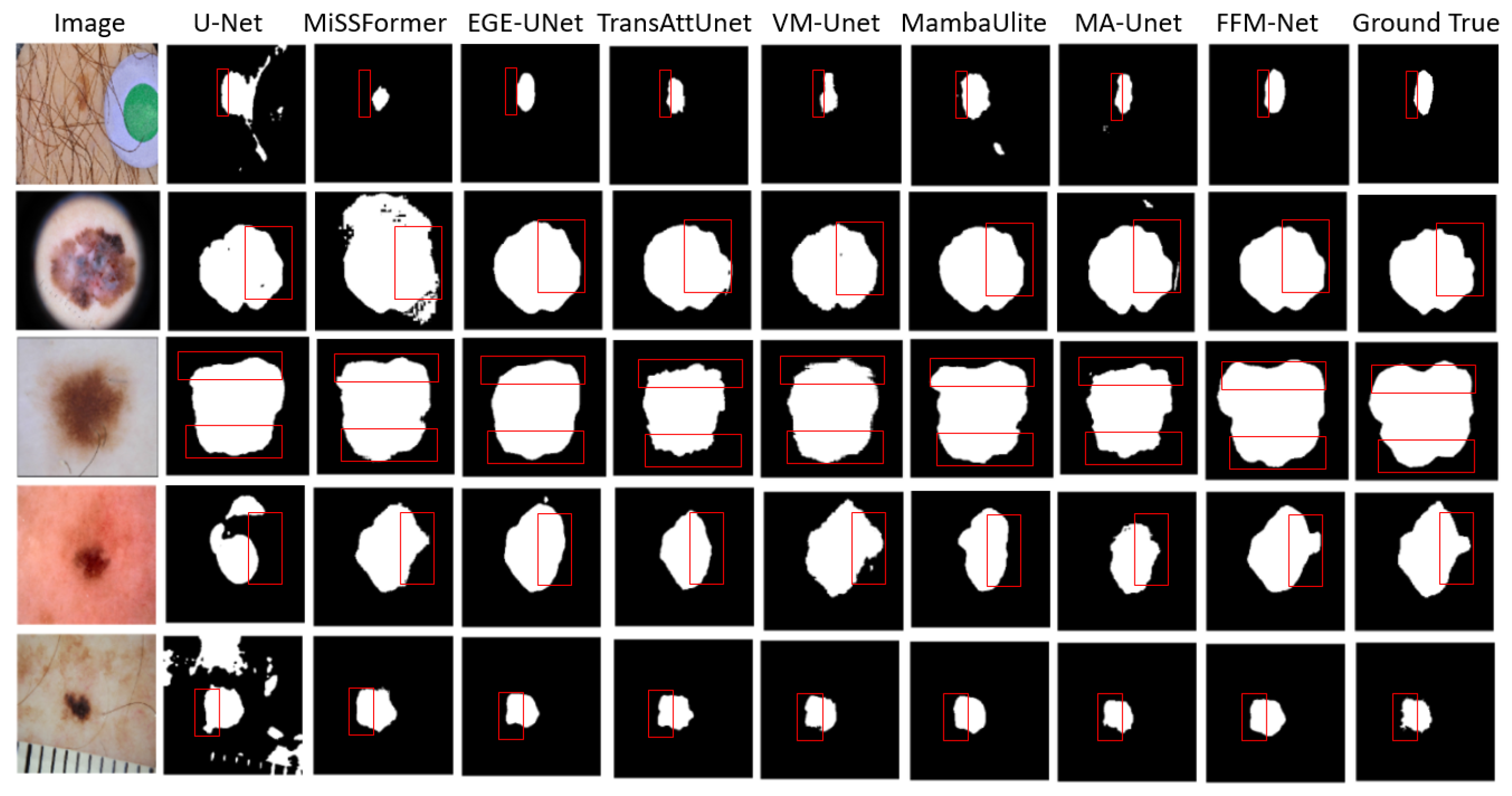

1]. Skin lesion image segmentation is crucial in medical diagnosis, as reliable medical image segmentation methods can help medical professionals quickly grasp the shape and detailed features of a patient’s lesion area, thereby laying the foundation for more accurate diagnostic and treatment decisions. However, accurately segmenting skin lesions remains challenging, with complex difficulties such as blurred skin lesion boundaries, irregular textured lesions, and lesion shapes of varying sizes, as shown in

Figure 1. These complexities make it difficult to distinguish them from normal skin tissues, and advanced segmentation techniques are needed to accurately identify and differentiate between various skin lesions.

Ronneberger et al. [

2] proposed the CNN-based U-Net architecture, which has emerged as one of the most extensively utilized networks for medical image segmentation tasks and maintains dominant status in the field of skin lesion segmentation. Zhou et al. introduced U-Net++ [

3], which utilizes dense skip connections between networks to resolve semantic differences between encoder and decoder paths, thus improving segmentation accuracy. Ruan et al. [

4] proposed an EGE-Unet network that integrates a multi-axis attention module to extract pathological information from different angles, which effectively enhances the recognition of irregularly shaped lesion regions and ensures the accuracy of segmentation. CMUNeXt [

5] is a lightweight skin lesion segmentation network based on large kernel convolution and inverted bottleneck design, which ensures segmentation accuracy while achieving lightweighting. Xu et al. [

6] proposed a DCSAU-Net network for melanoma segmentation, which effectively fuses low-level and high-level semantic information and enhances the network feature extraction by adopting a multipath approach with a different number of convolutions and a channel attention mechanism. Although CNN-based models possess excellent feature representation capabilities, they lack the ability to learn global information and long-term relationships due to the limitation of convolutional kernel size. Transformers [

7] employ multi-head self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies, enabling efficient global modeling and focusing on key regions of the image. TransUnet [

8] is a pioneer in medical image segmentation based on the Transformer model, integrating the Transformer into the final encoder layer of the widely used U-Net framework to explore its potential in medical image segmentation. TransAttUnet [

9] is a kind of attention-guided network based on the Transformer, which incorporates multi-level attention guidance and multi-scale skip connection methods, thereby enhancing the network’s capability to segment dermoscopic images of various shapes and sizes. Missformer [

10] is an effective and powerful medical image segmentation network that improves the performance of the model by redesigning the feedforward network to take full advantage of the multi-scale features generated from hierarchical Transformers. Li et al. [

11] proposed a medical image segmentation MA-UNet network based on U-Net, which designed two levels of encoders including rough ordinary extraction and multi-scale fine extraction to enhance the model feature extraction. CMLCNet [

12] introduces a capsule encoder to learn the relationship between parts and the whole in medical images, which helps the network to extract more local details and context information and reduces the problem of information loss caused by pooling in the process of downsampling. However, Transformer’s quadratic complexity also imposes a high computational burden, and the trade-off between global context modeling and computational efficiency remains unresolved.

Recently, state space models (SSMs) [

13] have attracted the interest of many researchers. Based on the traditional SSM, the modern SSM (Mamba [

14]) achieves a remarkable breakthrough by introducing an efficient selective scanning mechanism. This approach not only establishes long-range dependencies but also achieves five times higher throughput than Transformers. Moreover, its computational complexity scales linearly with input size, substantially improving computational efficiency. Ma et al. [

15] proposed a hybrid medical image segmentation model called U-Mamba based on SSMs. This model combines the local feature extraction capability of CNNs with SSM’s ability to capture long-range dependencies, effectively enhancing medical image segmentation capabilities while addressing the inherent issues of locality or computational complexity in both CNNs and Transformers. Vmamba [

16] employs a cross-scan module (SS2D) to process image blocks. It utilizes a quad-directional scanning strategy to achieve scanning in four directions, effectively capturing global features while reducing computational complexity. In addition, many researchers have applied Mamba to explore its potential in dermatoscopy image segmentation. Ruan et al. [

17] proposed a medical image segmentation model VM-UNet based on SSM, which captures a wide range of context information through visual state space blocks. MambaULite [

18] is a lightweight network model that efficiently segments skin lesion images with variable shapes by dynamically adjusting the fusion strategy of local and global features. Tang et al. [

19] proposed the RM-Unet network, which innovatively integrates the residual visual state space ResVSS block and the rotating SSM module to mitigate the network degradation problem caused by the reduced efficiency of information transmission from the shallow to the deep layers. Zou et al. [

20] introduced SkinMamba, a hybrid Mamba–CNN architecture for dermatologic image analysis. The model enhances segmentation precision by incorporating a frequency-boundary guided module at the bottleneck layer while leveraging retained information to assist the decoder during reconstruction.

In summary, although segmentation models based on CNNs, Transformers, and Mamba have made significant progress in medical imaging, CNNs struggle with limited local modeling capabilities, making it difficult to handle blurred boundaries and capture global structures. Transformers face challenges in effectively balancing complexity and accuracy. Existing Mamba models, constrained by fixed feature scanning methods, have yet to fully realize their potential. Furthermore, skin lesion segmentation continues to face challenges such as blurred lesion boundaries, varying lesion sizes, and information loss due to subsampling.

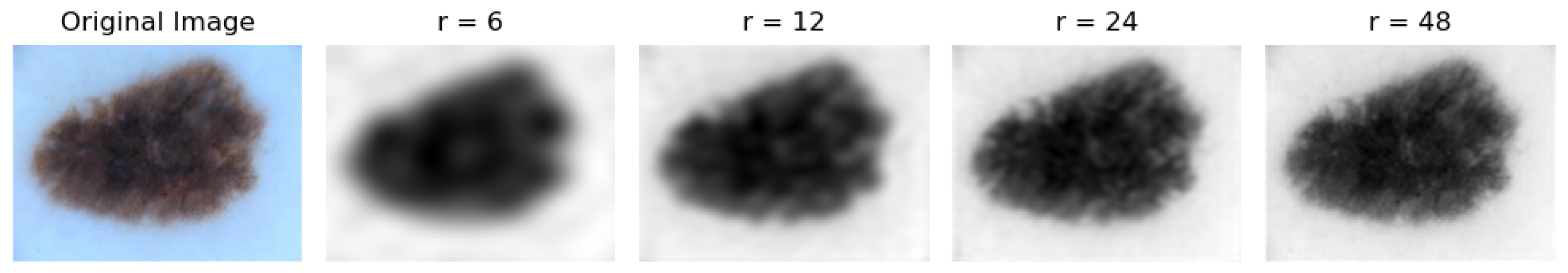

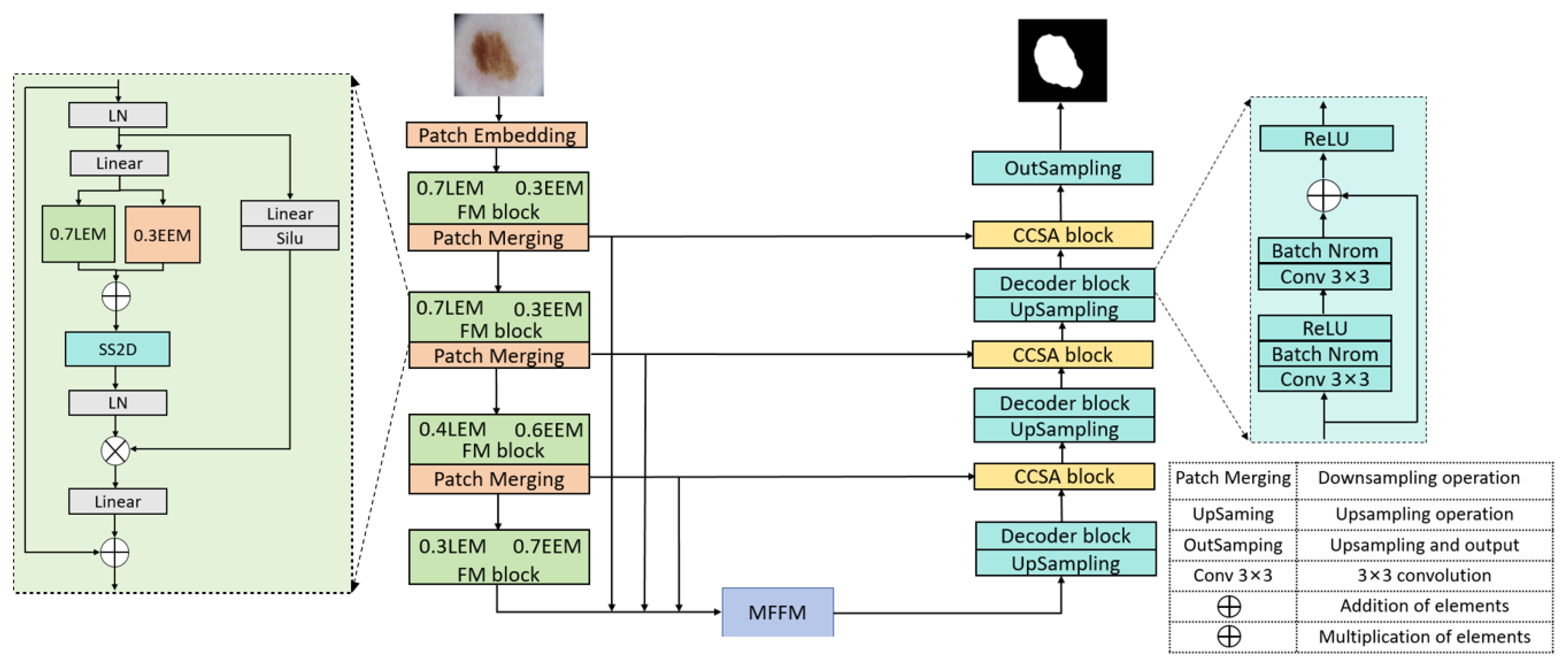

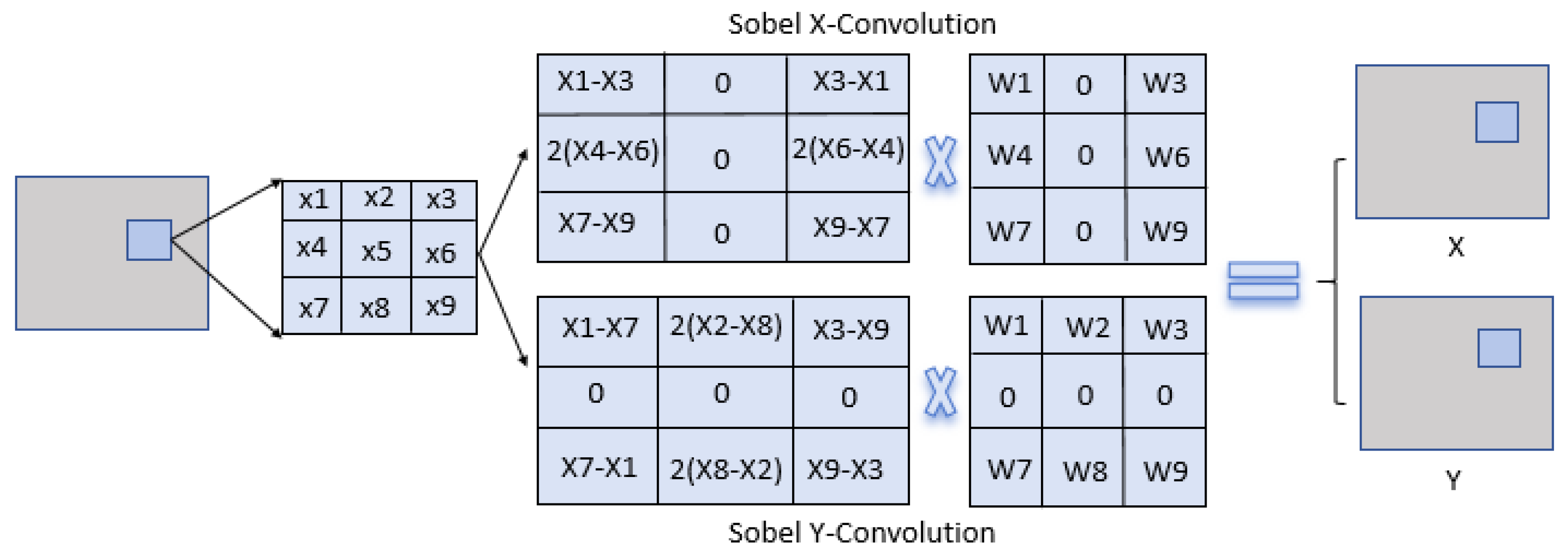

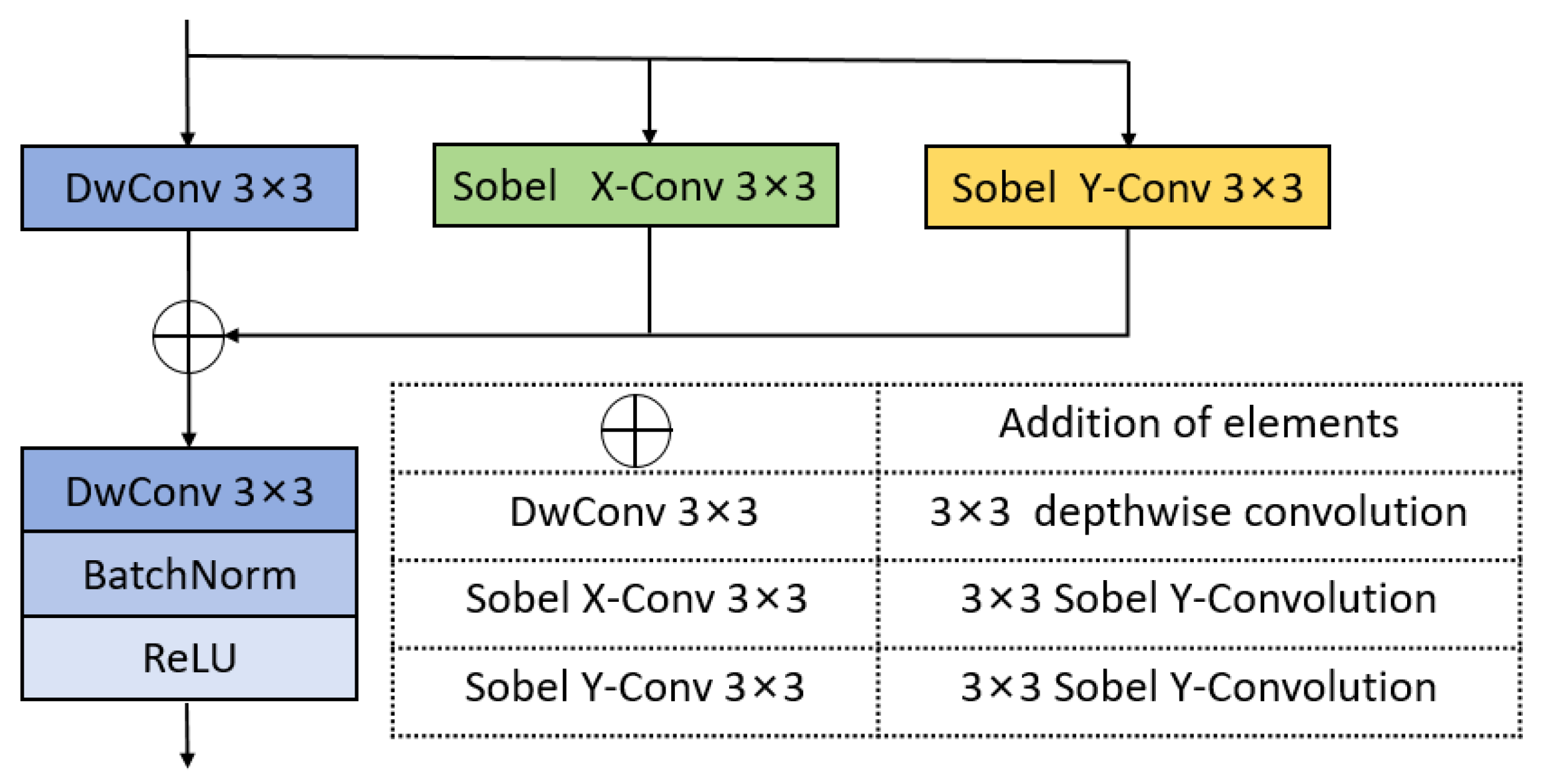

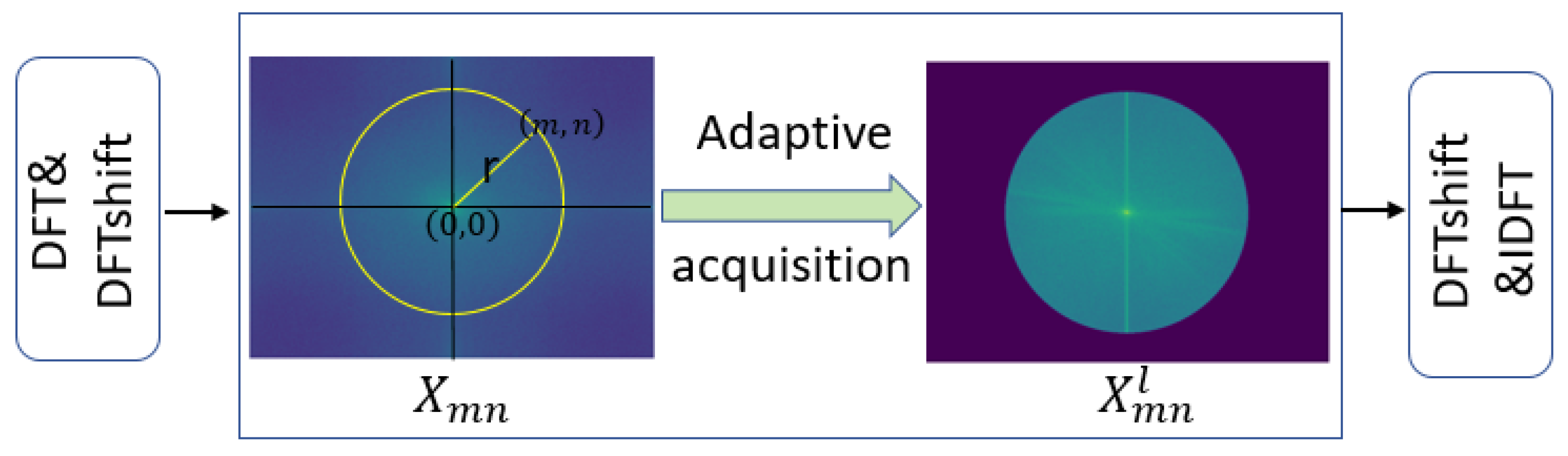

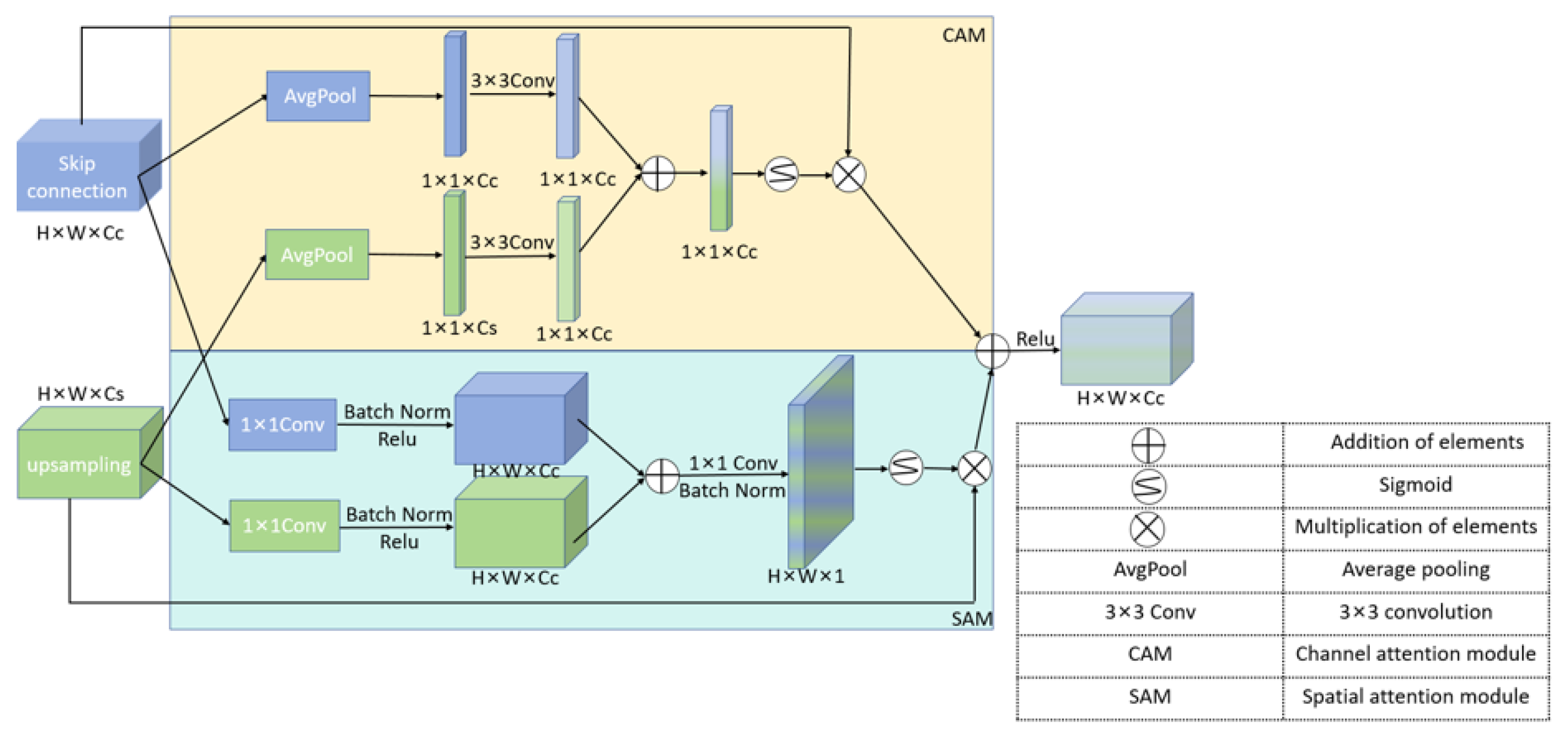

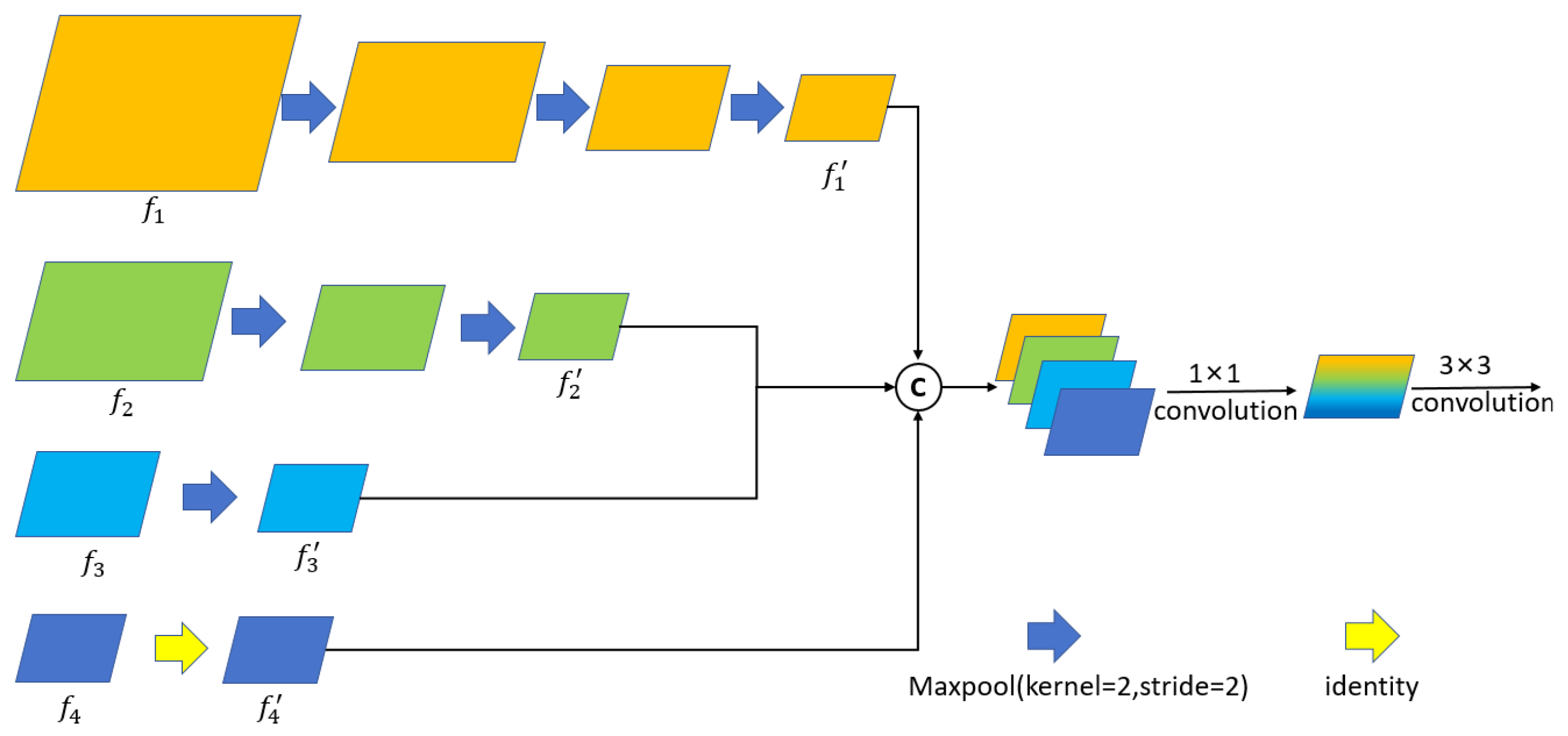

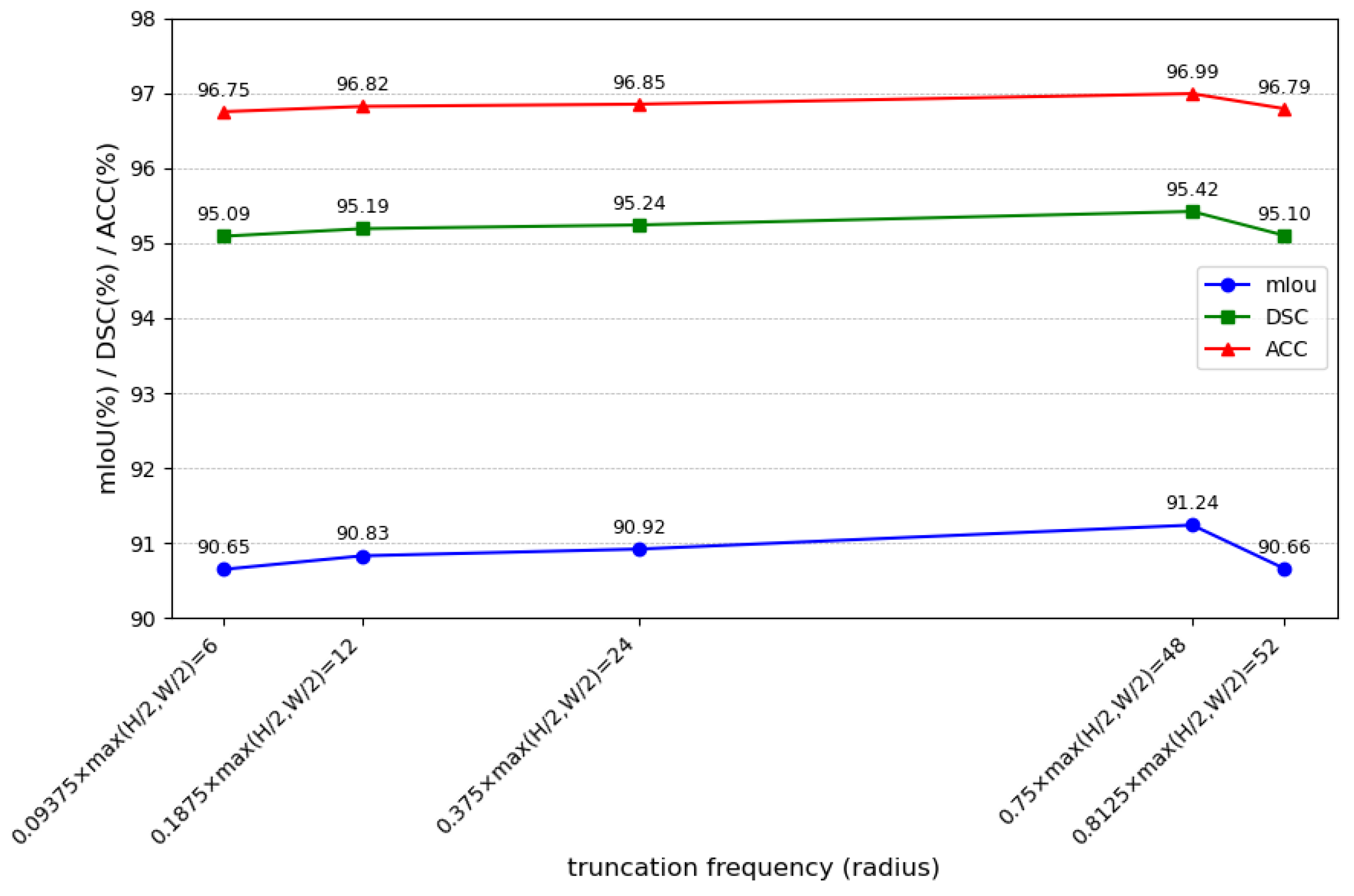

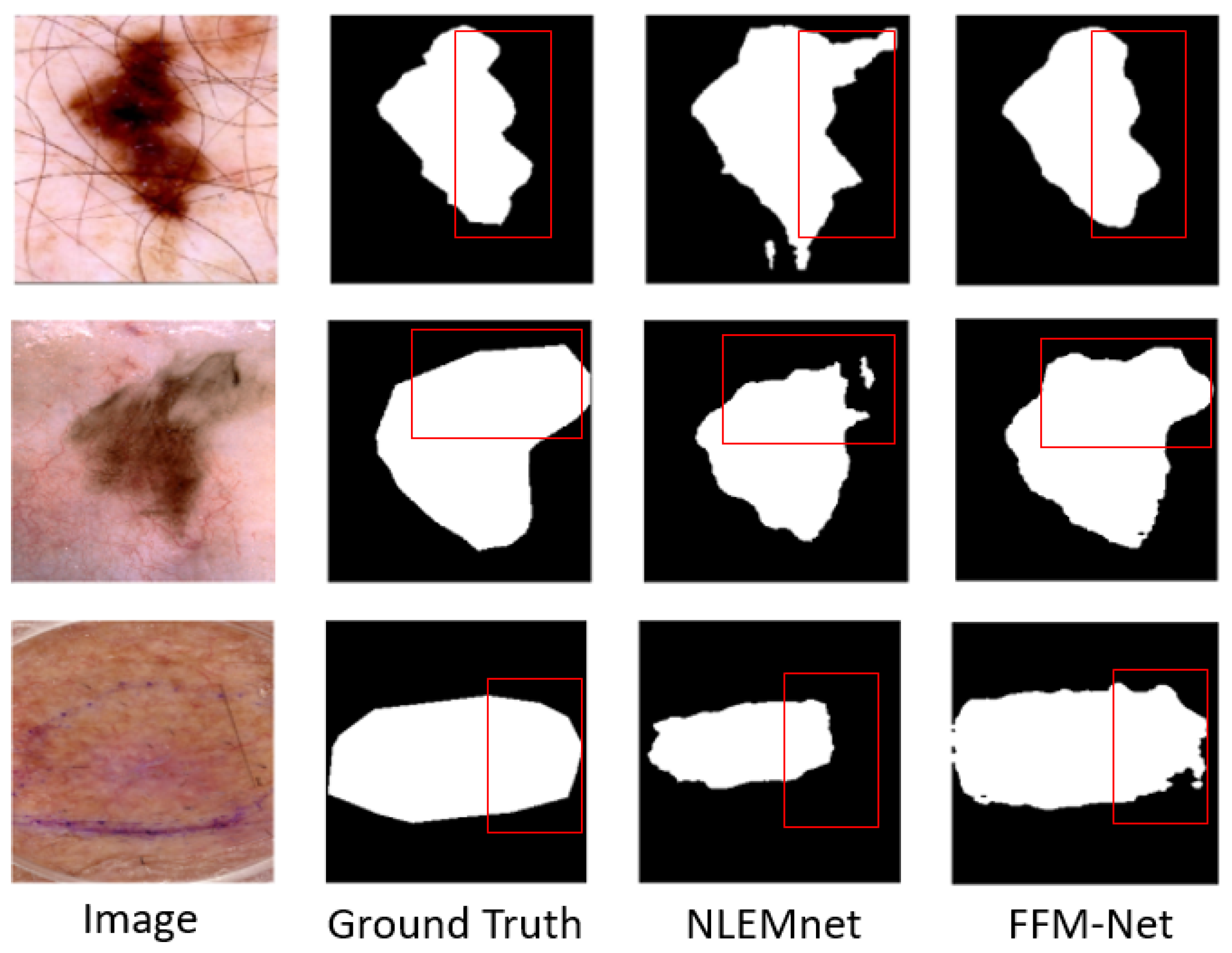

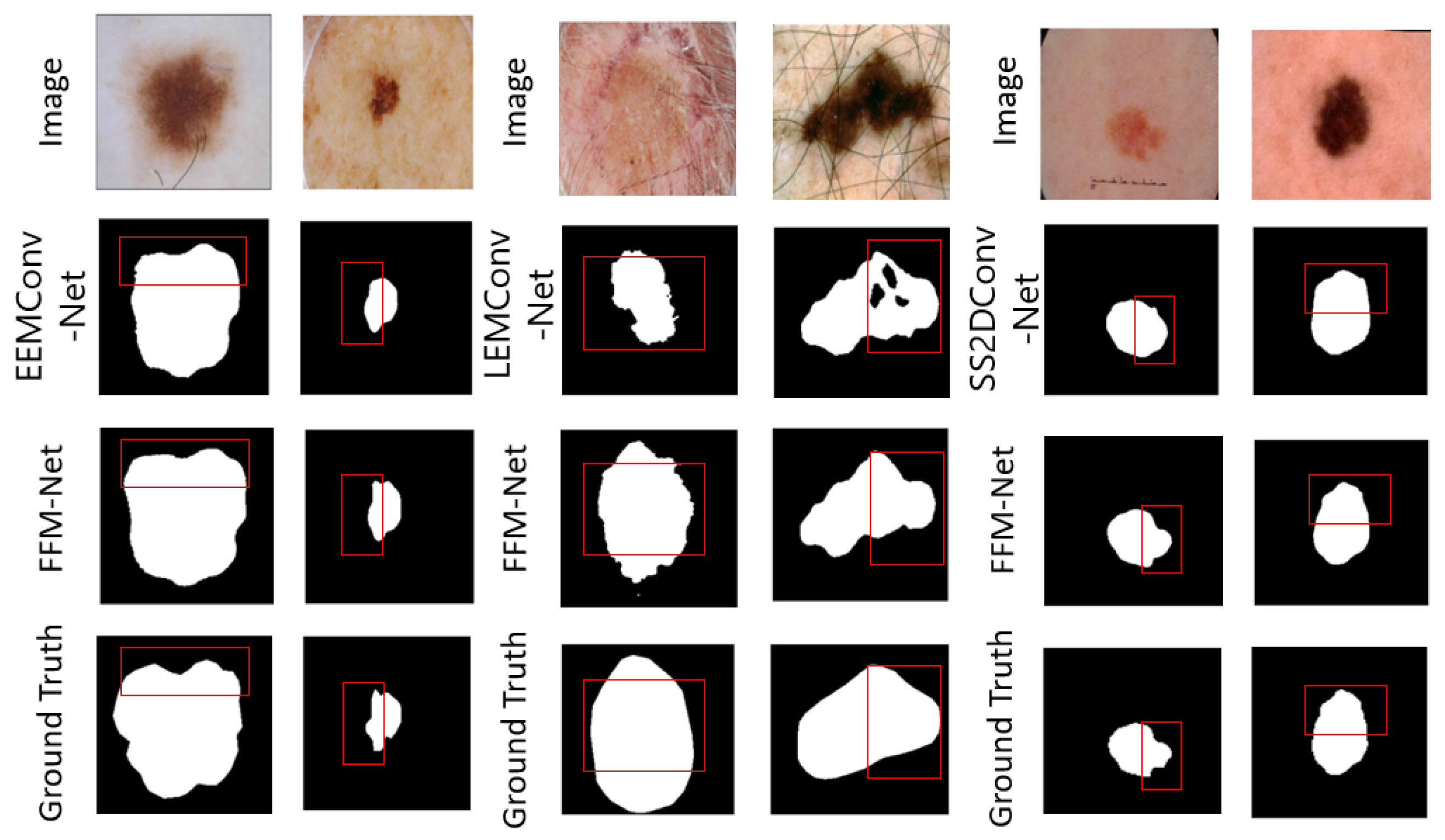

We propose FFM-Net, a novel architecture for lesion segmentation to extract more extensive feature information. In medical image segmentation, low-frequency information corresponds to regions with gradual image changes, characterizing the overall structural features of skin lesions. Edge detail information is associated with regions undergoing rapid and abrupt changes, delineating the sharp boundary transitions between lesions and normal skin. The FFM-Net effectively addresses skin lesion segmentation in images with blurred boundaries by dynamically adjusting the channel ratio between overall structure and edge details, and further improves the segmentation accuracy by leveraging the long-distance capture capability of the Mamba model. Given the higher image resolution and richer detail information in the shallow layer of the network, increasing the proportion of overall structural information channels helps preserve overall structural information. In the deeper layers of the network, with the decrease in image resolution and the abstraction of feature information, the proportion of edge information can be appropriately increased to capture more edge detail features. The low-frequency information extraction module (LEM) enhances overall structural feature extraction while suppressing interference from texture irregularities, while the edge detail extraction module (EEM) captures fine edge details. We design the cross-channel spatial attention module (CCSA) to effectively narrow the semantic gap between the encoder and decoder feature maps and enhance the sensitivity to the channel spatial dimension. In addition, we apply a multi-level feature fusion module (MFFM) at the bottleneck layer to fuse different levels of information, producing a feature map as an input to the first layer decoder. This ensures effective segmentation of lesions of varying sizes.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

We propose the FFM-Net model for the segmentation of skin lesions. FFM-Net uses a parallel two-branches architecture to extract the overall structure and edge detail information respectively. In addition, it dynamically adjusts channel-wise ratios between the two information streams at different network depths to adequately extract the information in the image.

We propose the CCSA module to enhance the model’s sensitivity to both channel and spatial dimensions, reducing the semantic gap between the encoder and decoder feature maps.

We propose the MFFM, which can effectively fuse multi-scale information to enhance the ability to learn feature representation.