Abstract

University website research to date tends to focus on conformity with technical standards. It rarely analyses the systemic nature of digital noise and its cognitive impacts. The study measures the intensity of digital noise on public websites of Polish universities (n = 65) and identifies its most common sources. The author investigates five dimensions: Distraction Intensity, Content Overload, Readability, Visual Balance, and Signal-to-Noise Ratio. The results are aggregated into a synthetic Noise Level Score (NLS) and analysed statistically. Four categories of digital noise have emerged from the observations: obligatory, compensated, ornamental, and habitual. This categorisation indicates that digital noise is not always random. It can be a supervised or even intentionally designed phenomenon when specific elements (such as disclaimers, system alerts, or consent layers) are not only expected but required by the user or the law. The study reveals a highly homogeneous sample and strong convergence of the results, indicating a systemic problem. Over 47% of the websites exhibited high NLS, while only 9% scored low. This means that content, visual, and interaction overloads are not incidental. Instead, it follows from the institutional and technological constraints on Polish higher education. The results ought to be interpreted in the context of the institutional communication imperative, defined as a constant pressure from legal obligations, standards, PR, market, and organisational factors towards constant publishing for multiple audiences through multiple channels.

1. Introduction

As the online ecosystem grows exponentially, users increasingly encounter an excess of content and interactive elements designed to attract their attention, which instead cause annoyance and disrupt website and web application use. Designs set to maximise user engagement blur the boundary between usability and visual overload, leading to form overwhelming the content []. Excess information, visuals, and interactive elements cause cognitive overload, hindering users’ cognitive abilities []. This leads to longer decision-making, increased user annoyance, poorer communication performance, and more frequent page abandonment []. The problem, commonly referred to as digital noise, is becoming a central challenge for user interface designers and organisations stewarding the performance, accessibility, and sustainable development of their websites.

Although researchers are eager to study the usability, accessibility, and sustainable development of digital services, digital noise remains under-researched and lacks a robust methodological framework. Website research to date has focused primarily on performance, SEO, perceptual accessibility, and web accessibility to people with disabilities [,,,,,]. Authors have also investigated interface ergonomics [] and website carbon footprint [], often refraining from systematically investigating user distractors and elements detrimental to browsing quality. Much less heed has been paid to a broader, systemic context of digital noise, covering organisational, legal, economic, market, cultural, and communication constraints. Moreover, a review of the available publications suggests that authors have yet to develop a standardised method for the qualitative and quantitative analysis of the problem, which makes it difficult to compare results across diverse contexts. This methodological gap hinders the precise diagnosis of the impact digital noise has on content perception, web system performance, and the environmental pressure they generate and prevents building any effective strategies for noise control.

Past attempts to assess website digital noise fail to depict the scale and complexity of the problem fully. The available tools focus on evaluating website quality through selected aspects, such as usability, performance, accessibility, and SEO (Lighthouse, GTmetrix, WAVE). Others, like Website Carbon and Ecograder, measure carbon footprint []. Each tool provides valuable information on specific dimensions. Still, there is no coherent methodology to integrate the results into a systematic umbrella audit that would yield an objective, comparable assessment of digital noise levels. It is a serious challenge to devise such a measurement tool and method because digital noise consists of both technical and cognitive components, such as pop-ups, autoplay, analytical scripts, and ‘visual noise and distortions’ that impact communication clarity. Digital noise is found in all user interface elements that are distracting, hinder cognitive concentration, and often cause annoyance []. Digital noise consists of content and functions of minuscule relevance to the user’s objectives and expectations. The practical impact of digital noise is excess code and interactions, reduced system performance, degraded usability, increased energy costs and carbon footprint, and lower conversion rates. The available analytical reports focus on selected aspects of the problem. Therefore, the analyses are fractional, and the tools could analyse only limited domains. This gap can be addressed by proposing an algorithmic index for aggregating measurement data, thereby facilitating systematic comparative audits across sectors.

University websites are not immune to digital noise, which can affect their clarity and accessibility. They are designed to respond to multiple user types, potentially leading to content overload, complex navigation, and profuse interactive elements. Multi-tier editorial hierarchies and distributed content management structures, typical of large institutions, can easily lead to visual and structural inconsistencies []. Users encounter various pop-ups, disclaimers, dynamic event announcements, and boxes with invitations to grants and conferences, which can be distracting and make it harder to reach the target piece of information. A large number of such elements can strain servers and increase the website’s carbon footprint. When traffic grows heavy (like during student enrolment), it becomes a technical as well as an environmental issue []. Digital noise can be detrimental to the perceived professional image of the institution and its search engine results page rank (duplicate content). The problem is particularly relevant to PR and effective online communication, where clarity and content availability emerge as critical competitive advantages.

The literature argues increasingly that digital noise is not just a matter of aesthetics or individual design decisions. It stems from a divergence between institutional communication restraints, such as pressure to comply with the law, accessibility standards, and security requirements, and the need to promote the institution and regularly expand content, as well as the needs of users who expect clarity and quick access to information []. University websites serve as a means of public communication. Hence, they have to cater for multiple stakeholder groups simultaneously, from candidates and students to staff and institutional partners. Combined with formal and technological limitations, this multipurpose design contributes to typical patterns of information overload and poor clarity. In light of the above, the author proposes a hypothesis (H1) that digital noise on university websites is systemic and caused by institutional and technological constraints of university operations rather than individual design decisions.

The study measures the intensity of digital noise on websites of Polish universities and identifies its most common sources. The analysis concentrates on identifying and measuring components of digital noise that may hinder the consumption of content and completion of basic tasks on university websites. The score covers such aspects as the prevalence of scripts, widgets, and interactive components. The results are interpreted to evaluate their potential impact on the comfort of use of the website and the consequences for sustainable development. The findings provide a background for devising a proposal for a systematic audit of digital noise, which could support universities in elevating the quality of their digital communication, optimising performance, and reducing their website carbon footprint. To this end, the author poses the following research questions:

- •

- RQ1: What components of university website structure and content contribute to digital noise the most?

This question’s purpose is to identify and classify elements considered digital noise, such as pop-ups, advertisements, notifications, widgets, autoplay, calls to action, and analytical and tracking scripts.

- •

- RQ2: Is digital noise on university websites systemic or incidental?

The answer to this question will help determine whether digital noise is a matter of unique, ‘random’ design errors or follows patterns driven by institutional and technological constraints that define how university websites function.

- •

- RQ3: Is it possible to objectively measure the intensity of digital noise on websites and present the result as a synthetic algorithmic indicator?

This question concerns the development of a tool to automatically and objectively quantify the intensity of digital noise using an algorithmic quality indicator. The indicator could synthesise various categories of digital noise components and represent the intensity with an aggregate score. This would help evaluate any optimisation efforts.

The primary theoretical contribution of the study is the empirical diagnosis of the extent and structure of digital noise on the websites of Polish universities, along with the development of a tool, an AI agent, for synthetic measurement of the noise. Another relevant contribution is the algorithmic Noise Level Score (NLS), which quantifies the intensity of digital noise to compare results across universities and sectors. In addition, the article offers proof that digital noise is a systemic problem and proposes a typology. The article follows a logical structure: Section 2 presents a theoretical background and a literature review concerning digital noise, including an analogy to spatial chaos, systemic conditions for its occurrence in higher education institutions, and research gaps. Section 3 characterises the material and research methods, including measurement procedures and design of the Noise Level Score. Section 4 presents the results of quantitative and qualitative analyses, with descriptive statistics, correlations, principal component analysis, and website clustering. Section 5 discusses the results in the international research context and offers their practical and theoretical implications, followed by research limitations. The Section 6 summarises the conclusions and potential future research agenda.

2. Background

2.1. From Spatial Disorder to Digital Disorder: Towards a Comparative Perspective

Similarly to urban space, where excess visual, acoustic, and informational stimuli are detrimental to the quality of life, the online environment increasingly often generates clutter, disturbing user activities []. The most common sources of urban chaos are profuse billboards, traffic signs and road surface markings, architectural diversity, and heavy traffic, along with the noise it produces. All these factors lead to cognitive overload, disrupt orientation, and disturb the comfort of using public spaces. In rural settings, spatial chaos typically emerges from the scattering of buildings, the accumulation of surface farming infrastructure, and incoherent aesthetics and architecture. All this is exacerbated by the high diversity of land uses and the limited openness of the space. The buildup of these issues leads to lower landscape aesthetic quality, poor visual coherence, and worse perception of the space by the community and visitors []. The same principles apply to the online ecosystem. Inflated content, banners, pop-ups, and interactive components add up to a digital landscape overgrown with stimuli, where information is overwhelmed by amassed communication []. Excessive advertising and ‘fancy’ widgets create information noise in the digital environment, preventing users from finding what they need. Digital noise is detrimental to website usability and response time. It can even discourage users from using a service, thereby hurting conversion rates []. The problem of digital noise or digital clutter can also affect individual devices, such as personal computers and mobile devices, as well as corporate networks, directly affecting data management efficiency [,].

Chaos in the natural and digital ecosystems can both be considered systemic problems driven by the logic of infrastructure growth, institutional and commercial pressures, and limited prioritisation of audience needs []. What is more, both cases have long-term systemic consequences. Real-life noise disturbs living organisms, while digital noise hinders conversion rate and leads to heavier use of resources, a larger carbon footprint, and poorer network performance. The problem of digital noise and its adverse impact has been recognised. Attempts are made to control it through design guidelines (such as WCAG and W3C specifications), code minification, and minimalist web design []. Natural environment clutter is resisted through regulations on spatial planning and management, road traffic, nature protection mechanisms, or designated vacant zones []. These efforts suggest that although it might be difficult to remove the ‘disturbances’ completely, it is possible to control them systematically to improve user and audience experience.

Natural ecosystem researchers have identified systemic causes of the disturbances, such as anthropogenic noise, land development pressure, light pollution, or habitat fragmentation []. Still, the matter has not yet been settled scientifically in the case of the digital ecosystem. University websites are particularly susceptible to the accumulation of diverse communication stimuli because they have multiple purposes: information, service, and promotion. Therefore, digital noise can be expected to emerge from synergistic institutional, technological, and organisational constraints rather than being incidental in this context. Hence, it is necessary to analyse the intensity of digital noise on university websites and identify its patterns.

2.2. Digital Noise on University Websites: From Communication Infrastructure to Systemic Burden

University websites have become part of a critical communication and service infrastructure of the education sector. They serve information, transactional, and regulatory functions, support domestic and international enrolment, provide student services, offer emergency communication, disseminate findings, and ensure compliance, including publication of notices with staff and administration job postings, public procurement procedures, and legally required documents regarding transparency of public institutions []. At the same time, they are used as a tool for brand building and to gain a competitive advantage in the education market, where the struggle for candidates, students, researchers, and institutional partners is intensifying. This convergence of roles may lead to tensions. Various stakeholder groups expect different types of content, formats, and lines of action. Additionally, webmaster teams work under various pressures: time, visibility and compliance indicators, and recently cyberthreats [].

This is where digital noise emerges. It is excessive and disorganised content combined with interactions that make it difficult for users to complete specific actions. Digital noise can be caused by design, organisational, and operational factors (including scattered editorial teams or no policy for content removal and archiving). Disturbances come from disruptors generated by technological, legal, or marketing forces, such as advertising banners, consent layers, pop-ups, or extensive widgets that can even overlap. Moreover, in real-world conditions, users often have multiple browser tabs and sources open simultaneously, which leads to the accumulation of stimuli, increased cognitive burden, and a lower success rate [].

The scale and systemic character of digital noise have socioeconomic and environmental consequences. Hindered access to information inflates the cost for candidates and students, intensifies digital inequalities in vulnerable groups, and reduces the efficiency of internal processes, such as administration, student and staff communication, publication of educational materials, and research project management. Excess programming libraries and resources published on websites put strain on the server infrastructure, affect performance, and may contribute to the website’s carbon footprint, which violates good sustainable design and Green SEO practices []. This is why digital noise should be considered a structural problem driven by technological, institutional, and communication constraints of higher education rather than a flaw of an individual website. In this sense, digital noise is not subjective ‘visual clutter’, but a quantifiable consequence of the tensions arising from the institution’s multiple roles and the needs and expectations of its users. It is operationalised through indicators of cognitive costs, including content density and redundancy, visual hierarchy, signal-to-noise ratio, and time and steps involved in the user path. Importantly, individual components of digital noise can be aggregated into synthetic scores to benchmark websites and analyse the origin of the load. This shifts the discussion from subjective aesthetics (‘websites don’t look nice’), which can hardly be unambiguously evaluated, to the level of system structure (‘websites are full of digital noise because this is how the current model of university communication moulds them’), which stresses editorial policies and organisational decisions more than technology. This understanding of digital noise demonstrates that the research perspective has to be expanded. Analyses involving solely technical parameters or formal compliance can offer only a fragmented picture of the cognitive and systemic costs of using academic websites. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the state of the art of university website research and identify areas in need of further exploration.

2.3. From Technical Compliance to Cognitive Burden: Research Gaps in University Website Studies

Campoverde-Molina et al. [] demonstrated that an overwhelming majority of studies of university websites focus on the formal assessment of technical compliance with standards such as the W3C’s WCAG and ISO/IEC 40500:2012 []. The advantage of this attitude is that researchers can apply uniform assessment criteria and perform comparative analyses. Still, it narrows down the perspective to solely technical aspects, disregarding user experience and sociocultural circumstances. Analyses of university websites by Kuppusamy and Balaji [] and Fakrudeen et al. [] focused on content accessibility according to the WCAG but did not consider perceptual accessibility, visual overload, or the intensity of graphic stimuli. Harper and DeWaters [] reported, over a dozen years ago, that universities faced substantial challenges when implementing even the most basic accessibility standards on their websites. Note that relevant legislation gained significant momentum in subsequent years. The study by Laamanen et al. [] analysed the impact of regulations on the accessibility of university websites in Finland concerning the WCAG. They demonstrated that despite binding regulations, many websites still posed significant accessibility barriers, like low text contrast, no alternative captions, or inaccurate links. Stasiak and Dzieńkowski [] investigated the accessibility of selected university websites in Poland. The authors employed a checklist and automated tools to identify the best- and worst-performing websites. Their findings revealed numerous shortcomings, including the absence of accessibility statements, poorly accessible PDFs, limited content personalisation options, and a lack of mobile versions. The authors emphasised that it is necessary to provide consistent organisational support, monitoring, and awareness-building for designers and webmasters to actually improve website accessibility, which can also be critical for preventing digital noise. Król and Zdonek [] reached similar conclusions in their study of public administration website accessibility.

The primary focus of university and public administration website quality studies between 2010 and 2020 was the assessment of compliance with the WCAG rather than analysing whether users are actually able to internalise the content and messages conveyed []. Campoverde-Molina et al. [] demonstrated that university website accessibility research tends to focus on automated tests of compliance with technical standards, disregarding broader user experience. As a result, even though many university websites score well in algorithmic evaluations, they still pose navigation, content-finding, and website structure usage issues. Vollenwyder et al. [] confirmed this asymmetry by proving empirically that better WCAG compliance does not have to mean better user experience, and may even hinder interaction in some cases. Therefore, the literature review clearly shows that technical shortcomings of university websites regarding WCAG compliance are better investigated than the actual user experience. As a result, there is not much insight into the mechanisms of digital noise generation by institutions, which can be considered complementary to accessibility.

Research on information overload and digital noise has grown more relevant in recent years, as reflected in the literature (Table 1). The comprehensive review by Arnold et al. [] demonstrates that information overload is primarily investigated from the user’s perspective, focusing on aspects such as attention-grabbing, cognitive abilities, and coping with overwhelming content. Shahrzadi et al. [] looked into the causes and effects of information overload and even took one more step further. Their study involved strategies to limit information overload, including day-to-day practices such as content filtering and time management.

Table 1.

Information overload and university website accessibility: assessment methods and findings.

Research on human–computer interaction contributed a theoretical and methodological foundation for cognitive overload and interface usability analysis, as well as analysing the effects of excess visual stimuli on the user, providing a foothold for further studies and in-depth analyses. Ma et al. [] demonstrated that browsing clutter, the problem of perceived ‘chaos in the web browser’ due to excessive and disorganised browser elements, adds to cognitive load and complicates information processing during browsing. Chen [] demonstrated that website structure perception and its usability improve when information load is reduced. Their conclusion is corroborated by guidelines proposed by the Nielsen Norman Group (NN/g). They emphasise the necessity to reduce cognitive load, which improves user experience [].

Website quality research indicates that poor accessibility, navigability, and control over distractors hurt the conversion rate. In the case of e-commerce, it means tangible financial loss. The Nielsen Norman Group demonstrated over two decades ago that a more usable web interface can improve the conversion rate by as much as 79%, which directly fuels income []. Empirical research in Indonesia revealed that better usability and optimisation of mobile e-commerce significantly improve customer satisfaction, driving sales []. Similar mechanisms can be applied to higher education, even though sales are not the goal there. Instead, universities aim for effective enrolment, promoting their courses, and securing partners or donors. Drivas et al. [] demonstrated that content management quality in CMS systems affects visibility and perception of institutional websites, supporting communication and organisational goals. Studies of the accessibility of university websites [] have highlighted the issues with accessing basic information due to technical barriers and structural complexity, resulting in a worse perception among candidates. This means that higher education, just like commercial settings, experiences ‘cognitive costs’ brought about by such factors as digital noise, excessive code, or lack of mobile optimisation, leading to lower user engagement and underperformance regarding strategic goals (Table 2).

Table 2.

Conversion in e-commerce and higher education.

Although there seems to be a consensus that controlled digital noise makes finding information easier, university websites rarely follow the relevant design recommendations. The potential reason is the domination of formal quality criteria, which shifts the institutional focus from user experience to compliance with standards [,]. The problem of digital noise on institutional websites remains under-researched, probably because it is more challenging to operationalise than an algorithmic verification of compliance with technical standards. To measure digital noise, one needs integrated tools capable of adopting a multidimensional approach, encompassing content density and structure, visual hierarchy, and signal-to-noise ratio. No methodology is available that combines the two: standard compliance and perceived usability. It could investigate digital noise structurally as a systemic problem arising from technological, institutional, and communication constraints. The present study addresses the situation by offering empirical evidence that digital noise arises from the dominant logic of university website design rather than from individual incidents.

3. Materials and Methods

The analysis covers all public universities in Poland (n = 65), as listed by the minister for higher education on 26 September 2025 []. The unit of analysis was the desktop version of the institutional website (top-level domain ccTLD), defined as the landing page with overlays (consent layers, pop-ups) and critical navigation elements above the fold. The sample was selected to ensure comparability and a uniform legal and organisational context. Note that the analysis did not involve the universities as such. The objective was to assess the quality of websites under this specific research design rather than rank the universities. This approach helps avoid bias to focus on the objective evaluation of websites rather than stigmatising the institution, focusing on its rank in the Polish higher education system. This neutrality promotes comparability of results and approaching the website as an object to analyse, disregarding the university’s reputation or status. A similar mode was followed in other studies [].

3.1. Tools and Procedure for Data Acquisition

The study adopts a unified definition of digital noise as a simultaneous profusion and disorganisation of content, visual elements, and interactive components that distract the user, reduce message clarity, and disturb the user path. This definition is the underpinning for operationalising the problem in five dimensions for quantification: (1) interaction (Distraction Intensity indicator, which is the magnitude of interrupters, such as banners, pop-ups, sliders, autoplay, and widgets), (2) content (Content Overload indicator, which is the saturation and simultaneous exposure to messages), (3) text (Readability indicator, which concerns the legibility and clarity of texts, including typography, paragraph length, and heading structure), (4) visual (Visual Balance indicator, which encompasses the compositional hierarchy and proportions and relationships among text, graphics, and margins), and (5) relation (Signal-to-Noise Ratio, which reflects the percentage ratio of user interface elements that are necessary to perform an operation, such as signing in and finding enrolment information or a schedule to all elements visible above the fold).

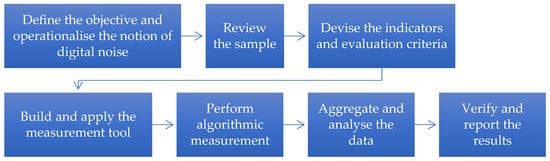

Each dimension has been converted into a component indicator expressed on a scale of 0 to 100 units (points). Next, the values were normalised and aggregated into the Noise Level Score (NLS, 0–100). All the component indicators (quantitative dimensions) are assumed to have equal weights to avoid weighting and ensure methodical neutrality. This way, the aggregate score is simpler, scores can be juxtaposed, and no subjective differences in the dimensions are introduced. The scores were obtained through analytical algorithms. No end users were involved in the process. Rather than constituting an objective snapshot, the resulting scores represent an AI-based automated heuristic evaluation of the current state of the websites, reflecting their structural level of cognitive load as defined by the operational criteria described in Appendix A. Similar approaches were employed in other studies on website quality []. Figure 1 summarises the stages of the research procedure.

Figure 1.

Stages of the research procedure.

The five dimensions of digital noise were evaluated in the ChatGPT environment (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA, vPlus, GPT-5), using a preconfigured agent (custom GPT) labelled ‘Digital Noise Evaluator’ (DNE v1.3, configuration snapshot of 10 September 2025) and created in ChatGPT Builder []. The agent has fixed instructions and uses a predefined input/output format. The model was fed a standardised input package, the website’s URL, with a short context for the job. The model generates a 0–100 score for Distraction Intensity, Content Overload, Readability, Visual Balance, and Signal-to-Noise Ratio, with a short explanation and a list of identified digital noise problems. The model configuration is intended to improve repeatability (low randomness), and the prompts and outcomes are archived. The evaluations generated by DNE v1.3 were deterministic, as the agent followed a fixed set of operational rules, low-randomness behaviour, and a standardised input/output structure. For this reason, each website was assessed once, and the stability of the results stemmed from the rule-based analytical procedure described in Appendix A. The resulting scores were subsequently normalised and aggregated into the Noise Level Score (NLS) according to the procedure presented in Section 3.2.

Digital Noise Evaluator (DNE v1.3) is based on a fixed set of prompts, predefined measurement dimensions, and a precise reporting format. It does not generate random content but performs a repetitive analysis following predefined rules that involve identifying specific categories of visuals on a website, such as pop-ups, banners, sections, and distorted visual hierarchy, and assigning each dimension a score of 0–100. This means that the evaluation process is predefined by the operational criteria, and the model is a classifier based on a set, repetitive evaluation scheme. Moreover, the input and output data formats are predefined and identical regardless of the website, which prevents arbitrary interpretations and supports reproducibility of the results. Configuration prompts, definitions of the indicators, and the response structure are provided in Appendix A.

Each URL was analysed based on a standardised input package, which includes the website address and a short description of the task activated with a predefined call-to-action (CTA), part of the DNE’s interface. The CTA activates the following prompt: ‘Evaluate the website in terms of digital noise’, which triggers a procedure based on predefined testing attributes. The tool’s responses have a fixed format with five predefined numerical scores and a short list of problems it detected. This additionally limits the potential for the model to deviate from the task and supports the replicability of the results. The fixed response format helped with automated extraction of the results for further processing as described in Section 3.2.

3.2. Analytical Procedures and Verification of the Measurement Tool

The results were statistically analysed in terms of the average, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, quartiles, and IQR. The coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated to verify the relative variation for the sample. The author applied Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ) with 95% confidence intervals determined through nonparametric bootstrap (5000 repeats) and tested the significance with Holm’s method. The dimensions were reduced, and the dominant axes of variability were interpreted using principal component analysis (PCA). The websites were categorised by noise level (low/medium/high) using k-means clustering (k = 3). The PCA involved a matrix of five standardised components. The PCA did not include the NLS. The results are reported in tables and figures. Only correlations between the five components were reported (Content Overload, Distraction Intensity, Readability, Visual Balance, and Signal-to-Noise Ratio). Each component was correlated with the composite indicator calculated after excluding that component through leave-one-out. This eliminated false high correlations between variables and their sum.

The NLS’s reliability was verified with three procedures: (1) analysis of component indicator convergence, (2) reduction in the dimensions with PCA, which confirmed a dominant axis interpreted as digital noise level, and (3) stability of the results for the sample measured with the coefficient of variation. The risk of subjective drift of the heuristic evaluations was limited with the consensus procedure, and indicator normalisation made the scores comparable.

4. Results

The quantitative results suggest a relatively highly uniform sample, especially in terms of Distraction Intensity and Content Overload. The mean Distraction Intensity value is 49.1 at a standard deviation of 5.1. The range is between 30 and 55 points, while the quartile values (45–55) indicate a stable and compact distribution of the scores. Content Overload reached the average of 56.4 at a standard deviation of 4.1 and a range of 40–60. Also, in this case, the results are concentrated in a relatively narrow range of 55 to 60 points, confirming the repeatability and the lack of significant outliers in the set (Table 3).

Table 3.

Averages, ranges, and quartiles of digital noise dimensions in the sample.

The average Readability is 69.7 (SD = 4.0; min.–max.: 65–80; IQR: 65–70), indicating that the texts are relatively easy to perceive, with minor differences across websites. For most websites, text typography was evaluated as correct, but the range suggests that optimisation is needed in some cases. The average Visual Balance was 58.3 (SD = 3.9; min.–max.: 55–70; IQR: 55–60), which reflects a moderate compositional harmony. The text and graphics layouts make up an overall acceptable visual hierarchy. Still, the lack of clear differences suggests that some websites seem overloaded or lack a clear structure.

The interquartile range (IQR) for the digital noise dimensions does not exceed several points (Content Overload: 55–60, Readability: 65–70, Visual Balance: 55–60, etc.), indicating that 50% of the observations are concentrated near the median. This finding suggests a fairly uniform sample and recurring design practices evident in the websites. Additionally, CVs range from 4.3% to 10.5%, which confirms the small relative differences between the indicators. The synthetic NLS is the most stable (CV = 4.3%), while Distraction Intensity is the most varied (CV = 10.5%). Hence, the results confirm that the sample was largely uniform.

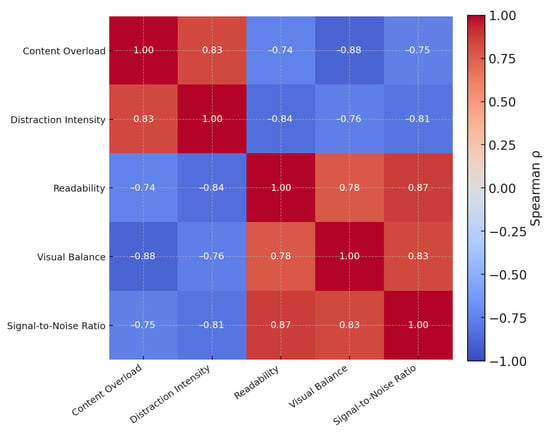

4.1. Correlations Among Digital Noise Dimensions

The correlation matrix reveals strong and consistent relationships among all the investigated indicators, which points to a convergence towards a common factor interpreted as the overall intensity of digital noise. This means that excessive content and distractors usually co-occur with lower readability and disturbed visual hierarchy, damaging the signal-to-noise ratio. Although the dimensions represent distinct aspects of digital noise, they remain highly correlated, forming a coherent fabric.

Content Overload and Distraction Intensity have a strong positive correlation (ρ ≈ 0.83), which indicates that excess content co-occurs with interruptions. Both the component indicators are very negatively correlated with Readability (ρ ≈ −0.74…−0.84) and Visual Balance (ρ ≈ −0.76…−0.88), and Signal-to-Noise Ratio is negatively correlated with Content Overload and Distraction Intensity (ρ ≈ −0.75…−0.81) and positively correlated with Readability and Visual Balance (ρ ≈ 0.83…0.87), which confirms that a better structure and readability increase the share of ‘signal’ compared to ‘noise’ (Figure 2). This means that websites that are clear and well designed have a more powerful message, more ‘signal’, while websites burdened by content overload and distractors lose key information in the digital noise.

Figure 2.

Relationships among digital noise dimensions: Spearman’s correlation matrix (N = 65). Source: generated with the DNE.

The pattern of high absolute values (typically |ρ| ≥ 0.75) suggests that the indicators are convergent on a common factor, i.e., digital noise intensity. Still, the lack of full collinearity (ρ < 1) indicates that each component contributes its own information. In terms of methodology, this situation confirms the construct’s cohesion and discernibility of the dimensions (no complete redundancy). This means that design interventions to limit Content Overload and Distraction Intensity should improve Readability and Visual Balance, leading to a better Signal-to-Noise Ratio, and help the user perform operations, which in turn boosts conversion rate. The relationships among the indicators demonstrate strong positive and negative links. For example, an increase in Content Overload and Distraction Intensity is correlated with a decline in Readability and Visual Balance. Still, this does not imply that any single factor is a direct cause of another. It is a case of correlation but not causation. The variables co-occur in line with a common pattern of digital noise, but there is no telling which is the cause and which is the effect of the dependence.

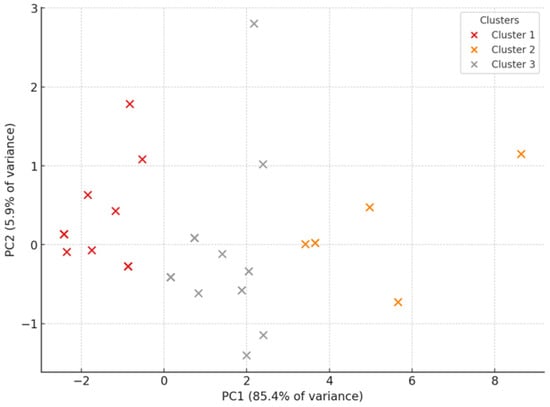

4.2. Results of Principal Component Analysis and Website Clustering

The principal component analysis (PCA) reduced the dimensions to two axes that explain over 91% of the total variance (PC1: 85.4%; PC2: 5.9%). This high degree of explained variance reflects the strong interdependence of the indicators and demonstrates that digital noise can be described synthetically with a single dominant dimension.

The first component (PC1) manifests the overall level of digital noise by combining high Content Overload and Distraction Intensity with low Readability and Visual Balance. The other component (PC2) is of lesser importance. It underscores the differences in Readability and Visual Balance. These PCA findings corroborate the previous observations based on the correlation matrix that the variables are not independent. On the contrary, they are associated and depict diverse aspects of the same phenomenon. Therefore, a reduction in dimensions drives data visualisation and emphasises the systemic nature of the problem rather than incidental cases (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Principal component analysis Source: generated with the DNE.

K-means clustering identified three clusters in the dataset. Despite the significant homogeneity, the clustering revealed subtle differences in digital noise intensity and information structure quality. The distribution of the websites in the PCA space shows that individual clusters lie along PC1, which reflects the general level of digital noise. Therefore, the clusters categorise websites into three types based on digital noise intensity: high (Cluster 1), low (Cluster 2), and medium (Cluster 3).

The distribution of the websites across the clusters indicates a dominance of high-intensity digital noise. Cluster 1, with 31 websites (47.7%), has the lowest Distraction Intensity and Content Overload, which shows that most university websites are overloaded with content and visual stimuli (Table 4). Cluster 3 holds 28 websites (43.1%) of medium digital noise intensity. It represents typical university websites in Poland. Cluster 2 has only six websites (9.2%), which are relatively the most lucid, with high Readability and Visual Balance. The small size of the group suggests that practices aimed at limiting digital noise are the exception rather than the rule.

Table 4.

Profiles of clusters delineated with digital noise indicators.

Cluster 1 comprises websites with the highest digital noise level, characterised by the highest stimulus intensity and excessive content. These problems are accompanied by reduced balance and readability, which increases the risk of distorted communication. Cluster 2 represents the other extreme of the spectrum. Its websites are relatively the clearest, with low Distraction Intensity and Content Overload, while the legibility and visual harmony are high (under the employed research design). The websites in Cluster 3 scored moderately. All their digital noise indicators reached medium values. These websites represent the quintessence of university websites, where, although content overload occurs, it is not as acute as in Cluster 1. This categorisation identified websites in urgent need of optimisation and those that showcase good practices.

5. Discussion

Digital noise should be analysed from an interdisciplinary perspective because it encompasses at least five intertwined areas of website quality assessment: usability, performance, accessibility, SEO, and sustainable development []. The proposed method can investigate them across cognitive, technical, environmental, socioeconomic, and cultural aspects simultaneously (Table 5). It is critical to integrate these outlooks to fully comprehend digital noise and its impact on user experience, institutional and environmental constraints, website performance, and search engine results page visibility.

Table 5.

Perspectives for interpreting digital noise.

The study answered the research questions. Regarding RQ1, the results indicate that profusion of content and accumulation of visual and interactive elements have the greatest impact on digital noise on university websites, specifically through various CTAs such as icons and buttons. High values of Content Overload and Distraction Intensity, together with low Readability and disturbed Visual Balance, confirm that structural content overload and intensive interactivity are the main drivers of digital noise. As a result, websites are no longer intuitive, and users have to learn specific procedures to use them. They have to remember access paths and where particular types of information can be found, rather than locating them organically and effortlessly. Thus, the effective use of such websites is not a result of their transparency, but of the mechanical paths, shortcuts, and navigation strategies that users have learned. This is how digital noise harms user-friendliness, turning an interactive experience into a memory exercise and replacing reasoned, smooth operation.

The analysis has confirmed that digital noise is a systemic problem (RQ2). The high sample homogeneity, strong correlations between the indicators, and PCA findings demonstrate that digital noise is an effect of institutional and technological constraints imposed on universities rather than individual design decisions. The hypothesis (H1) that digital noise on university websites is systemic and caused by institutional and technological constraints has been confirmed. This means that systemic effort—far beyond mere aesthetics and individual design practices—is necessary to control digital noise. It is imperative to deploy consistent organisational guidelines that clearly delineate roles between editors and administrators. Another solution is to popularise tools for comparative auditing of digital noise levels among institutions. Furthermore, the study shows that integrating the five dimensions (Distraction Intensity, Content Overload, Readability, Visual Balance, and Signal-to-Noise Ratio) into the synthetic Noise Level Score (NLS) facilitates a comparative assessment of digital noise (RQ3). The score has been demonstrated to be a useful tool for website classification and identifying groups of high and low digital noise. It should be noted at this point that the homogeneity (significant similarities) of the results should be interpreted considering the characteristics of LLM-based measurement tools. When websites’ structures are similar, as is the case with university websites, which often use similar templates and content structures, an AI model with a set palette of heuristics may reduce score variability and generate results that approach the average. Such a ‘regression towards the mean’ can potentially cause distortions and offer an alternative explanation for the low variance of the results. Therefore, both factors need to be considered when interpreting the results: on the one hand, the websites can actually be similar, but on the other hand, the tool’s design can amplify homogeneity. This observation is discussed in detail in Section 6.2.

5.1. Digital Noise on University Websites: Systemic Constraints

The review of literature and publications to date has shown that the research gap related to digital noise is mainly due to the lack of a common definition and operationalisation of the problem, combined with the dominance of the technical approach over the structural perspective in website quality evaluation. The literature often appreciates the links between the impact of digital noise on users and operational performance and goal attainment [,]. Still, researchers typically focus on the technical aspects, such as HTML, CSS, WCAG, programming libraries and scripts, while overlooking the actual user and organisational environment. There are no cross-sectional studies of vulnerable user groups, such as older people, children, and youth, that use multiple devices and assistive technologies. The studies can hardly be replicated because there are no open tools, benchmarks, or data that combine automated, expert, and telemetric audits. Moreover, disregard for managerial limitations, including content publishing policies or division of administrative and editorial competencies, hampers conclusions and the establishment of design standards. Note further that researchers have yet to tackle the relationship between digital noise and Green SEO []. They should particularly address the question of the extent to which a reduction in digital noise through control of content, script, and interaction profusion, for example, affects performance and environmental metrics (such as Core Web Vitals and carbon footprint) and organic visibility, along with potential tradeoffs. Research to date concerns how to measure digital noise accurately as an index combining semantics, information value, visuals, interaction, and temporal aspects, what is its connection to key UX metrics, how institutional factors modulate digital noise, and to what extent browsing clutter amplifies its effect [,,,]. Some researchers proposed that a higher level of digital noise is correlated with lower conversion rates, higher bounce rates, and greater cognitive load, while interventions to reduce digital noise improve user success []. Note that optimisation efforts are not made easier, considering that digital noise is mostly treated as a subjective issue. This would mean that users can perceive a given interface differently. A component considered attractive and dynamic by some can be seen as a distraction and a source of cognitive overload by others. Because of this subjective perception, digital noise controls cannot be fuelled by technical indicators alone. They must consider diversified user expectations, preferences, and competencies []. As a result, a corrective action can be appreciated or rejected at the same time, which makes it a challenge to devise a universal standard for digital noise controls. All this shows how complex and under-researched digital noise is and that it requires an interdisciplinary perspective to be fully understood.

The findings clearly indicate sample homogeneity, embodied by small ranges of the quantitative indicators. It can be considered a result of overlapping institutional, technological, and organisational constraints, which affect Polish university website design at the systemic level. The relatively small differences in results values indicate that digital noise on university websites is a systemic rather than incidental problem. Therefore, content overload and excessive visual intensity should be considered inherent to the university website design approaches in Poland. Moreover, the similarity of the results stems largely from standardised design practices. Universities employ similar technologies that follow comparable logics of information and visual structures. Also, university consortia implement jointly devised, identical information and communications technologies []. Another relevant factor is common guidelines for digital accessibility and data security that put restrictions on custom aesthetics and functionalities. The results can also be driven by the multipurpose nature of university websites. They have to address the needs of multiple audiences simultaneously, from candidates and students to staff and institutional partners. This causes a wide content spectrum, which contributes to similar patterns of information overflow and reduced communication clarity. Also, the fact that universities tend to be highly formalised environments, and so is their communication, perpetuates specific paradigms found on almost every website. The limited competitive pressure in the public sector promotes conservative design approaches and reinforces the homogeneity identified in the study. In light of the above, it is reasonable to conclude that digital noise on university websites is structural and caused by systemic constraints rather than individual design decisions.

Another potential reason for the relatively homogeneous results is the limitation of the research method. The indicators are based on averages and may fail to reflect subtle quality differences between the websites. Hence, the measurement method’s limitations can amplify similarities as it, in a way, reduces the complex problem into several generalised dimensions. Still, such reductions and simplifications of multidimensional phenomena with synthetic models are common in empirical studies, especially when the problems are complex and samples are large [,].

Furthermore, the findings can indicate that university websites in Poland are at a similar level of structural development. This uniformity may be due to a similar point in time when the websites were upgraded to offer elevated accessibility, mobile experience, unified visual identity, and security protocols, followed by the same time frame for adapting to regulations on content accessibility, personal data protection, and cybersecurity. In this context, similar levels of digital noise do not have to be a sign of systemic problems only. They may also reflect a transition where all universities move towards a specific standard. The design practices may diverge later when institutions start to look for more individualised solutions.

5.2. Causes of Digital Noise on University Websites

Websites of higher education institutions inherently cater for multiple audiences, such as candidates, students, graduates, researchers, and institutional partners. Each of them expects a different set of functionalities and information. This leads to website overload with numerous sections and parallel notices that absorb the user’s attention. There is no single ‘main objective’, so the message is diluted and the Signal-To-Noise Ratio drops. Typically, the user receives no clear-cut path to action. Sliders, banners, multi-level menus, and additional tools like corporate email, WCAG icons, social media icons, multimedia, name days, weather, air quality, celebrations, cookie consents, intranet links, staff search engines, and regulations and documents lead to a high Distraction Intensity. These elements often divert attention from valuable content, generating additional ‘communication noise’. The present analysis has demonstrated that similar problems are systemic; nearly every tested website had content overload and a low level of visual hierarchy. This confirms that digital noise on university websites is not an exception but a standard.

Therefore, the findings ought to be interpreted in the context of the institutional communication imperative, defined as a constant pressure from legal obligations, standards, PR, market, and organisational factors towards constant publishing to multiple audiences through multiple channels. In higher education, the imperative emerges from disclosure obligations (GDPR, e-privacy, accessibility, transparency, security), enrolment and promotion, grant financial reporting, and internal performance indicators. This leads to the accumulation of stimuli in the user interface: content density and redundancy grow, distractors multiply (consent management platforms, banners, pop-ups, widgets, etc.), and visual hierarchy becomes blurred. The problem is structural rather than aesthetic. Digital noise should be considered a quantifiable effect of tensions between the institution’s roles and user needs, not merely a ‘visual clutter’. This is detrimental to user success rate (conversion rate), longer searches for information, and increased cognitive load, which can be augmented by browsing clutter []. At the same time, the structural approach is overwhelmed by technical compliance, which shifts the focus from user experience to consistency with requirements and standards [,]. Distributed responsibility for content and lack of centralised CMS additionally lead to simultaneous publications in multiple locations, hindering consistency, removal of duplicates, and control of link rot [].

6. Conclusions

The study sheds new light on digital noise on university websites, providing empirical proof of its structural origin. The findings demonstrate that digital noise is not a collection of incidental design flaws, but a consequence of systemic institutional and technological constraints. The analysis quantified the scale of the problem and identified three categories of university websites with different intensities of digital noise. This new outlook can offer practical recommendations that, in general, boil down to reducing excess content, minimising distracting components, and enhancing visual harmony and readability. Universities that deploy digital noise controls today provide inspiring examples of good practices, paving the path for digital communication in higher education.

6.1. Practical Implications

The critical point to limit content overload is to reduce excess messages by prioritising key information and limiting the number of elements exposed simultaneously on the landing page. Digital noise could also be controlled by targeting the landing page to a specific user group, such as candidates or students. It is just as important to reduce the number of distractors, including banners and pop-ups, which should be saved for special circumstances only. Improved visual composition, with a coherent identity and correct text, graphics, and neutral space ratios, enhances communication. Another important consideration is to improve readability by hierarchical arrangement of thematic sections, clear typography, and proper colour contrast. Finally, universities should conduct comprehensive quality audits of their websites, including carbon footprint, WCAG compliance, SEO, performance, links, and content. Synthetic indices and comparisons with other institutions would help gradually remove sources of digital noise.

University websites have to reconcile functions related to compliance, catering to various stakeholders, promotion, and information. The higher stimuli density is, in this case, caused by the struggle to ensure transparency and a wide reach of communications. Considering this, the objective is not to eliminate digital noise completely, but to trim it to ensure efficient operation and quick access to information. The four-fold typology of digital noise helps with content management and noise control. This categorisation indicates that digital noise is not always random. It can be a supervised or even intentionally designed phenomenon when specific elements are expected or required by the user or the law:

- •

- Obligatory noise is caused by regulatory and legal obligations, including notifications from the consent management platform, technical alerts, and security messages. It should be as little intrusive as possible by design. It should not be superimposed on navigation components or key content, and should be minimised or otherwise hidden automatically after the user performs the action.

- •

- Compensated noise emerges from numerous roles and functions of the university. It originates from the multiplicity of channels, modules, and information sections. The problem can be reduced if the content is displayed in layers and revealed progressively according to the user’s type, role, or function (role-aware interface). Elements that are not important should be hidden by default.

- •

- Ornamental noise comes from redundant content, fancy widgets, and autoplay. It should be eliminated because it lacks information value and harms usability.

This typology can be complemented with so-called habitual noise. It is a result of perpetuated aesthetic conventions and dominant design trends. It includes elements such as banners, navigation icons, and dynamic visuals that users expect, even though they add to cognitive load. Paradoxically, if these components are not used, the website may be perceived as unprofessional or outdated, underscoring the ambiguous nature of this type of digital noise.

Rather than introducing arbitrary design changes, it is recommended to focus on managing the cognitive load budget (attention budget) by following limits and rules for controlling the user’s cognitive load. It involves defining acceptability thresholds, such as the maximum number of interruptions of a single user path, the minimum signal-to-noise ratio, or the number of interactive elements above the fold. This approach can better balance the communication imperative and usability and accessibility requirements, while supporting both sustainable design and conversion rate. Each approach should be verified empirically through split testing (A/B) and user exploratory testing. This philosophy is challenging in terms of methodology, cost, and organisation, but it can confirm that a specific level of digital noise is not detrimental to website functionality and user experience quality.

6.2. Limitations and Further Research

The presented analysis is a cross-sectional assessment of the above-the-fold area of university website landing pages, disregarding full user paths or user testing. By aggregating the results into the NLS, the author reduced the problem’s complexity for easier comparison. Still, it could blur some subtle differences. Future research should include triangulation across the NLS, performance and accessibility metrics, environmental measures (such as carbon footprint), and usability tests (such as time to complete or success rate).

DNE is based on a published GPT model, a known set of prompts, an archived configuration snapshot, and standardised input and output formats, which ensures measurement replicability in an identical environment. However, the closed regime of the core language model (GPT-5) and the lack of access to the source code mechanics remain a limitation. This means that, despite the complete transparency of the tool’s operational layer, the technology of the generative model itself offers limited clarity, which is not unusual in research using commercial AI models.

The results indicate a relatively high homogeneity of digital noise levels across the sample. It may confirm the assumption that the problem is systemic for university websites. It is also possible that the homogeneity is a consequence of the properties of the measurement tool, which performs the evaluation using a set of common, predefined operational criteria. This operational principle can limit variance and support the ‘levelling out’ of results for websites with similar content structures. Therefore, the homogeneity of the NLS levels should be interpreted considering the characteristics of the analysed websites and the measurement procedure. Therefore, further research is necessary, employing methodological triangulation, such as comparison of DNE’s results with an expert judgement or results of other AI tools to confirm the systemic nature of digital noise in this case. Note also that the employed research design has equal weights for all five dimensions of digital noise to ensure methodological neutrality and avoid overestimating any factor. This is in line with the general practice of designing composite quality indices when the absence of unambiguous theoretical or empirical grounds for using diverse weights justifies equal weighting. Note, however, that equal weights can reduce dimension diversification in an aggregate score. Therefore, future research on the NLS could involve considering alternative aggregation strategies, including expert judgement, analysis of variance, or PCA methods.

The analysis involved only desktop websites, limiting the ability to extrapolate the results to mobile devices and various screen configurations. It also does not take into account seasonal factors, such as the enrolment period, which can affect the number of banners, notices, or information overlays. The study does not account for geolocation and any personalisation effects it may have (country/IP, language, cultural characteristics), which means that the website’s layout may differ depending on the country. The measurement was also conducted for a single consent status. No differences between full decline and full acceptance (or intermediary statuses) were investigated. Therefore, the findings should be considered an image of a single input layer of the websites (a snapshot of the basic, default state). Future research should include tests on mobile devices, sampling at various times of year, tests in different geographical locations, and measurements in at least two extreme CMP states.

Funding

Funded by a subsidy from the Ministry of Education and Science for the University of Agriculture in Krakow, Poland, for the year 2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ccTLD | country code Top-Level Domain |

| CMP | Consent Management Platform |

| CSS | Cascading Style Sheets |

| CTA | Call to Action |

| DNE | Digital Noise Evaluator |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| HTML | HyperText Markup Language |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| NLS | Noise Level Score |

| NN/g | Nielsen Norman Group |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SEO | Search Engine Optimisation |

| W3C | World Wide Web Consortium |

| WAVE | WAVE Web Accessibility Evaluation Tools |

| WCAG | Web Content Accessibility Guidelines |

Appendix A

These specifications contain the configuration of Digital Noise Evaluator (DNE v1.3), including definitions of the metrics, evaluation rules, algorithm structure, and data format, for easy replication of the measurement procedure: 10.6084/m9.figshare.30640289.

References

- Arnold, M.; Goldschmitt, M.; Rigotti, T. Dealing with Information Overload: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1122200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrzadi, L.; Mansouri, A.; Alavi, M.; Shabani, A. Causes, Consequences, and Strategies to Deal with Information Overload: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2024, 4, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belabbes, M.A.; Ruthven, I.; Moshfeghi, Y.; Rasmussen Pennington, D. Information Overload: A Concept Analysis. J. Doc. 2023, 79, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakoulopoulos, A.; Konstantinou, N.; Koutsompolis, D.; Pergantis, M.; Varlamis, I. Academic Excellence, Website Quality, SEO Performance: Is There a Correlation? Future Internet 2019, 11, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgül, Y. Accessibility, Usability, Quality Performance, and Readability Evaluation of University Websites of Turkey: A Comparative Study of State and Private Universities. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2021, 20, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Kuppusamy, K.S. Web Accessibility Investigation and Identification of Major Issues of Higher Education Websites with Statistical Measures: A Case Study of College Websites. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, K.; Sroka, W. Internet in the Middle of Nowhere: Performance of Geoportals in Rural Areas According to Core Web Vitals. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoverde-Molina, M.; Luján-Mora, S.; Valverde, L. Accessibility of University Websites Worldwide: A Systematic Literature Review. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2023, 22, 133–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, Y.; Kulakli, A. Evaluation of Open and Distance Education Websites: A Hybrid Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Approach. Systems 2023, 11, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri, L.; Fraboni, F.; Brendel, H.; Pietrantoni, L.; Vidoni, R.; Dallasega, P. Updating Design Guidelines for Cognitive Ergonomics in Human-Centred Collaborative Robotics Applications: An Expert Survey. Appl. Ergon. 2024, 117, 104246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Masurkar, S.; Pathade, G.R. An Overview of Digital Transformation and Environmental Sustainability: Threats, Opportunities, and Solutions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, K. Sustainability Audit of University Websites in Poland: Analysing Carbon Footprint and Sustainable Design Conformity. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.R.; Sauro, J. Measuring the Perceived Clutter of Websites. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 5260–5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louraço, D.; Marques, C.G. CMS in Public Administration: A Comparative Analysis. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. Manag. 2022, 7, 11688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moacdieh, N.; Sarter, N. Display Clutter: A Review of Definitions and Measurement Techniques. Hum. Factors 2015, 57, 61–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagtendonk, A.J.; Vermaat, J.E. Visual Perception of Cluttering in Landscapes: Developing a Low Resolution GIS-Evaluation Method. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 124, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Lassila, H.; Nurgalieva, L.; Lindqvist, J. When Browsing Gets Cluttered: Exploring and Modeling Interactions of Browsing Clutter, Browsing Habits, and Coping. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 19 April 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, R.; Auinger, A. Developing a Conversion Rate Optimization Framework for Digital Retailers—Case Study. J. Mark. Anal. 2023, 11, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, S.; Lanzeni, D.; Horst, H. Data Anxieties: Finding Trust in Everyday Digital Mess. Big Data Soc. 2018, 5, 2053951718756685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğur, N.G.; Çalışkan, K. Time for De-Cluttering: Digital Clutter Scaling for Individuals and Enterprises. Comput. Secur. 2022, 119, 102751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuch, A.N.; Presslaber, E.E.; Stöcklin, M.; Opwis, K.; Bargas-Avila, J.A. The Role of Visual Complexity and Prototypicality Regarding First Impression of Websites: Working towards Understanding Aesthetic Judgments. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2012, 70, 794–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, G. Urban Spatial Order: Street Network Orientation, Configuration, and Entropy. Appl. Netw. Sci. 2019, 4, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordello, R.; Ratel, O.; Flamerie De Lachapelle, F.; Leger, C.; Dambry, A.; Vanpeene, S. Evidence of the Impact of Noise Pollution on Biodiversity: A Systematic Map. Environ. Evid. 2020, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallie, H.S.; Thompson, A.; Titis, E.; Stephens, P. Analysing Cyber Attacks and Cyber Security Vulnerabilities in the University Sector. Computers 2025, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 40500:2012; Information Technology—W3C Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/58625.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Kuppusamy, K.S.; Balaji, V. Evaluating Web Accessibility of Educational Institutions Websites Using a Variable Magnitude Approach. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2023, 22, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakrudeen, M.; Rajan, A.; Alameri, A.H.M.; Almheiri, A.M.L.O. Assessing Higher Education Websites in the Middle East: A Comparative Analysis of UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. In Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Conference on Information Technology Trends (ITT), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 24–25 May 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, K.A.; DeWaters, J. A Quest for Website Accessibility in Higher Education Institutions. Internet High. Educ. 2008, 11, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laamanen, M.; Ladonlahti, T.; Puupponen, H.; Kärkkäinen, T. Does the Law Matter? An Empirical Study on the Accessibility of Finnish Higher Education Institutions’ Web Pages. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2024, 23, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiak, W.; Dzieńkowski, M. Accessibility Assessment of Selected University Websites. J. Comput. Sci. Inst. 2021, 19, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, K.; Zdonek, D. Local Government Website Accessibility—Evidence from Poland. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollenwyder, B.; Petralito, S.; Iten, G.H.; Brühlmann, F.; Opwis, K.; Mekler, E.D. How Compliance with Web Accessibility Standards Shapes the Experiences of Users with and without Disabilities. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2023, 170, 102956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. Improving Website Structure through Reducing Information Overload. Decis. Support Syst. 2018, 110, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitenton, K. Minimize Cognitive Load to Maximize Usability. Nielsen Norman Group (NN/g). Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/minimize-cognitive-load/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Nielsen, J. Is Poor Usability Killing E-Commerce? Nielsen Norman Group (NN/g). Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/did-poor-usability-kill-e-commerce/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Nawir, F.; Hendrawan, S.A. The Impact of Website Usability and Mobile Optimization on Customer Satisfaction and Sales Conversion Rates in E-Commerce Businesses in Indonesia. Eastasouth J. Inf. Syst. Comput. Sci. 2024, 2, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drivas, I.; Kouis, D.; Kyriaki-Manessi, D.; Giannakopoulos, G. Content Management Systems Performance and Compliance Assessment Based on a Data-Driven Search Engine Optimization Methodology. Information 2021, 12, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List of Public Universities Supervised by the Minister Responsible for Higher Education and Science—Public Academic Universities. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/nauka/wykaz-uczelni-publicznych-nadzorowanych-przez-ministra-wlasciwego-ds-szkolnictwa-wyzszego-i-nauki-publiczne-uczelnie-akademickie (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Digital Noise Evaluator. ChatGPT OpenAI. Available online: https://chatgpt.com/g/g-68bd154a296c819185ea8f0bff029792-digital-noise-evaluator (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Shaban, A.; Pearson, E.; Chang, V. Evaluation of User Experience, Cognitive Load, and Training Performance of a Gamified Cognitive Training Application for Children With Learning Disabilities. Front. Comput. Sci. 2021, 3, 617056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Liu, D.; Kwan, M.-P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Machine-Based Understanding of Noise Perception in Urban Environments Using Mobility-Based Sensing Data. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2024, 114, 102204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincer-Daszkiewicz, J. Success story—25 years of digitalization of higher education institutions in Poland. In Proceedings of the EUNIS 2024 Annual Congress in Athens, Athens, Greece, 5–7 June 2024; Volume 105, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, K. Average UX Improvements Are Shrinking over Time. Nielsen Norman Group (NN/g). Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/ux-gains-shrinking (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Macías, J.A.; Borges, C.R. Monitoring and Forecasting Usability Indicators: A Business Intelligence Approach for Leveraging User-Centered Evaluation Data. Sci. Comput. Program. 2024, 234, 103077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garett, R.; Chiu, J.; Zhang, L.; Young, S.D. A Literature Review: Website Design and User Engagement. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 2016, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Król, K.; Zdonek, D. Peculiarity of the Bit Rot and Link Rot Phenomena. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2019, 69, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).