Abstract

This paper presents SP-TeachLLM, a novel framework that leverages large language models (LLMs) to deliver intelligent tutoring for computer science education. SP-TeachLLM integrates advanced AI techniques with established educational theories to enable personalized and adaptive learning experiences. Its core innovation lies in a multi-module collaborative architecture that encompasses curriculum decomposition, multi-strategy generation, reflective learning, and memory augmentation. Comprehensive experiments are conducted to evaluate the system’s effectiveness in enhancing knowledge mastery, problem-solving ability, and teaching performance. The results demonstrate that SP-TeachLLM significantly outperforms conventional approaches, providing valuable insights into the application of AI in education and advancing the development of next-generation intelligent tutoring systems.

1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of educational technology (EdTech) is reshaping modern education. According to the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE), the global EdTech market reached $341 billion in 2023 and is expected to expand to $678 billion by 2028, representing an annual growth rate of 14.79% []. This accelerating growth underscores a global demand for innovative, data-driven solutions that enhance both teaching efficiency and learning outcomes. However, UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report indicates that approximately 258 million children and youth worldwide remain out of school, revealing persistent disparities in educational resource allocation. These challenges—such as the mismatch between personalized learning needs and limited instructional capacity, and the growing workload faced by teachers—highlight the urgent necessity for intelligent and scalable educational technologies.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become an essential driver of educational innovation. From early rule-based tutoring systems to recent adaptive learning platforms, AI-enabled approaches have increasingly enhanced personalization and automation in instruction [,,]. The emergence of large language models (LLMs), exemplified by GPT and LLaMA, has further expanded these possibilities by demonstrating strong abilities in reasoning, explanation, and content generation [,]. These models offer new opportunities to construct intelligent tutoring systems (ITS) that can engage in dialogue, provide formative feedback, and support individualized learning experiences.

Despite their promise, current LLM-based educational applications remain limited in scope. Most focus on knowledge-oriented question answering or basic tutoring tasks such as automated assessment and short-answer feedback. These systems generally lack systematic instructional planning and struggle to adapt dynamically to diverse learner profiles or long-term learning trajectories []. Traditional ITSs, while adaptive to some extent, still rely on handcrafted rules and shallow reasoning, making them unable to adjust teaching strategies in real time based on complex learner feedback []. Consequently, both paradigms fall short in meeting the demands of personalized, explainable, and adaptive learning in complex educational contexts.

To address these challenges, we propose an innovative framework called SP-TeachLLM—a multi-module, LLM-driven teaching assistant system designed to achieve intelligent instructional planning, adaptive feedback, and explainable decision support. SP-TeachLLM integrates LLMs with advanced prompting, reinforcement learning, and cognitive theories to build a comprehensive, self-optimizing teaching framework. The system is composed of four major modules: (1) a Task Decomposition Module that breaks complex educational goals into hierarchical subtasks; (2) a Multi-Strategy Generation Module that proposes diverse teaching plans; (3) a Reflective Learning Module that refines strategies through feedback analysis; and (4) a Memory Enhancement Module that maintains long-term contextual and knowledge support.

Distinct from prior data-driven systems, SP-TeachLLM is grounded in cognitive science and educational psychology. It employs Bloom’s Taxonomy to structure learning objectives [], Cognitive Load Theory to optimize content organization [], and Constructivist Learning Theory to enable interactive and learner-centered teaching []. Reinforcement learning further supports continuous optimization, enabling dynamic adaptation to diverse learners while maintaining pedagogical interpretability and transparency. Concretely, this work investigates how large language models can be systematically integrated into intelligent tutoring systems for programming education, and whether the proposed SP-TeachLLM framework can enhance knowledge mastery, problem-solving skills, and teaching performance compared with conventional LLM-based tutoring baselines.

The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- We propose SP-TeachLLM, a novel multi-module LLM-based teaching assistance framework that integrates cognitive theories with adaptive learning mechanisms.

- We design a comprehensive set of collaborative modules—including task decomposition, multi-strategy generation, reflective learning, and memory enhancement—to achieve dynamic, explainable, and context-aware instructional planning.

- We introduce a reinforcement learning-based optimization mechanism that continuously improves strategy selection and personalization over time.

- We validate the effectiveness of SP-TeachLLM through extensive experiments on multiple programming education benchmarks, demonstrating superior adaptability and pedagogical performance compared with existing LLM-based tutoring systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related studies and summarizes the advantages and limitations of current approaches. Section 3 describes the design and implementation of SP-TeachLLM in detail. Section 4 presents experimental results and discusses their implications for AI-assisted education. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITS)

The evolution of Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITS) has laid a solid foundation for adaptive and personalized learning research. Early rule-based systems, such as SCHOLAR and ACT, pioneered AI-driven instruction but suffered from limited flexibility and scalability [,]. Later data-driven approaches, including knowledge tracing and affective computing models, improved personalization yet still lacked deep semantic understanding and contextual reasoning [].

Recent advances in deep learning have expanded ITS capabilities. Deep Knowledge Tracing (DKT) [], for instance, models students’ learning dynamics using recurrent neural networks, substantially improving prediction accuracy and knowledge state modeling. Nevertheless, even these deep models struggle with integrating heterogeneous knowledge sources and capturing long-term learning trajectories []. These limitations highlight the need for explainable and cognitively grounded systems. In this paper, we address these challenges through SP-TeachLLM, a large language model-driven teaching framework that integrates cognitive theories, multi-module collaboration, and reinforcement learning to achieve adaptive and interpretable tutoring.

2.2. Large Language Models for Intelligent Tutoring Systems

Recent applications of large language models (LLMs) have demonstrated strong potential for enhancing various components of intelligent tutoring systems (ITS). Kasneci et al. [] provided a comprehensive analysis of how ChatGPT 4.0 and similar LLMs can support educational scenarios, highlighting opportunities in feedback generation, adaptive support, and learner engagement. Kikalishvili [] examined the pedagogical value of GPT-3 for personalized content delivery and outlined practical guidelines for integrating LLMs into real-world classrooms. Mazzullo et al. [] discussed the role of LLMs in learning analytics, emphasizing their capacity to process student-generated data and infer learning patterns relevant to ITS adaptation. Pilicita and Barra [] demonstrated that LLMs can effectively classify student comments and thus serve as analytical engines for formative assessment. Finally, Giannakos et al. [] reviewed the broader landscape of generative AI in education, identifying both the promise and challenges of employing LLMs as interactive educational agents. Together, these works motivate the development of LLM-driven ITS architectures such as SP-TeachLLM.

However, most existing LLM-based educational applications remain confined to short-term or isolated tasks, and their black-box nature limits interpretability and educational accountability. Despite ongoing efforts to improve model transparency, current approaches still fall short in supporting complex pedagogical reasoning and long-term instructional planning. Integrating LLMs with reinforcement learning presents a promising path for adaptive and goal-oriented educational AI. For example, InstructGPT employs reinforcement learning from human feedback to align model behavior with human intent [].

Despite such progress, current LLM-based systems still lack systematic instructional planning, cross-domain integration, and theory-guided adaptation. Our proposed SP-TeachLLM addresses these limitations by combining LLM reasoning with RL-based optimization and cognitive-theory-informed design to achieve adaptive and explainable teaching assistance.

2.3. Educational Data Mining and Learning Analytics Technologies

Advances in educational data mining (EDM) and learning analytics (LA) have enabled data-driven, individualized learning. Baker and Yacef [] developed early behavioral prediction models, while Yudelson et al. [] introduced knowledge tracing for modeling learners’ cognitive states. These methods extract meaningful patterns from large-scale data, allowing educators to better understand learners’ needs and progress.

For instance, Papamitsiou and Economides [] reviewed evidence from prior empirical studies showing that clickstream data and response-time analytics can be used to predict academic achievement and identify learning difficulties. Such work lays the foundation for dynamic learner modeling but rarely connects to teaching strategy generation. SP-TeachLLM bridges this gap by integrating data-driven learner modeling with adaptive instructional planning, enabling real-time feedback and pedagogical adjustment.

2.4. Reinforcement Learning and Knowledge Graph Technologies

Reinforcement learning (RL) has been applied to optimize adaptive teaching strategies. Narvekar et al. [] utilized RL for dynamic curriculum planning via Q-learning, which iteratively updates an action-value function to maximize long-term educational outcomes. This adaptive mechanism allows automatic adjustment of instructional strategies based on student performance.

In parallel, knowledge graphs (KGs) provide structured representations of complex domain knowledge. Recent studies combining KGs with neural networks [] enhance semantic understanding by aggregating relational information across concepts, enabling more context-aware educational support. Building on these advances, SP-TeachLLM integrates RL and KG reasoning with LLMs to construct a more comprehensive and adaptive teaching system. Specifically, our framework emphasizes three aspects:

- Systematic Instructional Planning: End-to-end support from learning objective decomposition to teaching strategy optimization ensures process coherence.

- Deep Personalization: By combining LLM-based reasoning with learner modeling, the system delivers adaptive and student-centered teaching.

- Theory-Driven AI Design: Grounded in Constructivist Learning [] and Cognitive Load Theory [], SP-TeachLLM prioritizes pedagogical interpretability over purely technical optimization.

Through this integrated approach, SP-TeachLLM bridges cutting-edge AI with educational theory to enhance teaching quality and promote learning equity.

2.5. Planning Capabilities of LLM Agents

Recent research on LLM agents’ planning capabilities provides key technical foundations for this work. Techniques such as Chain of Thought (CoT) [] and ReAct [] enable step-by-step reasoning and dynamic task decomposition, enhancing interpretability and control. Further extensions, such as Tree of Thoughts (ToT) [], introduce multi-path reasoning and decision exploration. Reflection-based mechanisms such as Self-Refine [] and Reflexion [] improve iterative self-correction, while memory-augmented models like [] strengthen long-term contextual learning.

Collectively, these advances form the technical underpinnings of SP-TeachLLM, which unifies task decomposition, multi-strategy generation, reflective learning, and memory enhancement to achieve adaptive, explainable, and cognitively grounded teaching support.

3. Method

3.1. Problem Formulation

Before introducing the proposed SP-TeachLLM framework, we first formalize the instructional planning problem. Let the learning state space, teaching activity space, and learning objective space be denoted as S, A, and G, respectively. The instructional planning task can be represented as a quintuple , where defines the state transition function, and denotes the initial learning state. The goal is to determine an optimal teaching policy that selects appropriate actions for a given learning state and objective . By executing this policy, the framework generates a sequence of instructional activities that guide the learner toward the desired goal. Formally, the optimization problem can be expressed as:

where denotes the reward measuring the degree of alignment between the final state and the desired objective g, and represents the expectation over trajectories induced by .

3.2. SP-TeachLLM Framework Overview

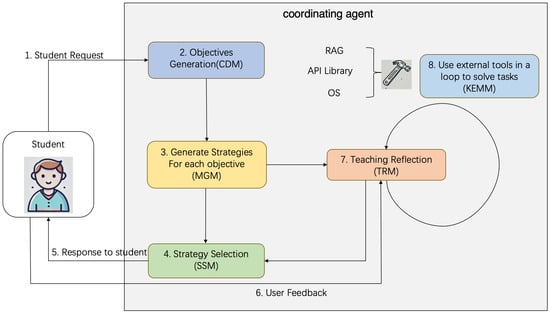

Building on this formulation, we propose SP-TeachLLM, a unified intelligent teaching assistant framework integrating large language models (LLMs), reinforcement learning, and educational theories. As shown in Figure 1, the system comprises five interconnected modules: the Curriculum Decomposition Module (CDM), Multi-Strategy Generation Module (MGM), Strategy Selection Module (SSM), Knowledge and Experience Memory Module (KEMM), and Teaching Reflection Module (TRM). Together, they form a closed-loop pipeline in which CDM decomposes learning goals, MGM generates instructional strategies, SSM adaptively selects the most suitable one, TRM evaluates outcomes, and KEMM maintains cumulative knowledge for continual refinement.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed SP-TeachLLM framework and the interactions among CDM, MGM, SSM, KEMM, and TRM.

The framework’s novelty lies in the deep integration of educational theory and AI reasoning. CDM employs Bloom’s Taxonomy [] with the semantic understanding of LLMs to hierarchically decompose learning objectives. MGM and SSM embed principles from Cognitive Load Theory [] and Constructivist Learning Theory [] to generate and adapt teaching strategies. TRM incorporates Metacognitive Theory to enable reflective self-assessment and continuous optimization. The modules operate iteratively, forming a self-improving loop of planning, reflection, and adaptation.

In future deployments with human learners, the Teaching Reflection Module (TRM) and Strategy Selection Module (SSM) can incorporate process-level signals (e.g., step-wise solution traces, time-on-task, and explanation quality) into their reward and diagnostic models, enabling the system to better distinguish genuine learning progress from over-reliance on external AI tools.

3.3. Pedagogical Foundations of SP-TeachLLM

SP-TeachLLM is grounded in three widely accepted educational theories that guide its instructional behaviors. First, Bloom’s Taxonomy informs the design of the Curriculum Decomposition Module (CDM), which structures learning objectives across hierarchical cognitive levels—from recall and understanding to application and creation—ensuring progressive skill development. Second, Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) motivates the Multi-Strategy Generation Module (MGM) and the Strategy Selection Module (SSM), which regulate informational complexity, reduce extraneous load, and select explanations or examples that match a learner’s estimated proficiency. Finally, Constructivist Learning Theory underpins the Knowledge and Experience Memory Module (KEMM) and the Teaching Reflection Module (TRM), enabling iterative knowledge construction through feedback, self-correction, and personalized scaffolding. Together, these theoretical principles shape the design and interaction patterns of SP-TeachLLM’s instructional architecture.

3.4. Curriculum Decomposition Module (CDM)

The CDM decomposes complex educational goals into structured, manageable sub-objectives by combining LLM-driven semantic reasoning with pedagogical theory. It conducts fine-grained semantic analysis to ensure accurate interpretation of learning objectives, applies Bloom’s Taxonomy to organize them across cognitive levels—from recall to synthesis and evaluation—and constructs a knowledge graph that captures inter-concept dependencies and prerequisite relations. Decomposition granularity is dynamically adjusted according to task complexity and learner proficiency: beginners receive finer-grained content, while advanced learners engage with broader conceptual groupings. For interdisciplinary courses, cross-domain mappings are also identified to promote integrative understanding.

Formally, if O denotes the set of learning objectives, and a specific objective, the decomposition function is:

where each represents a sub-objective. The hierarchical relationships are represented as a directed acyclic graph (DAG) , where V denotes all nodes (objectives and sub-objectives) and E denotes dependencies. This output establishes the foundation for personalized learning paths and adaptive strategy generation.

3.5. Multi-Strategy Generation Module (MGM)

The MGM generates diverse teaching strategies for each sub-objective identified by CDM. It leverages LLMs to design pedagogically sound and context-aware strategies across modalities such as direct instruction, inquiry-based learning, project-driven exercises, collaborative discussions, and gamified learning. Each strategy is customized based on subject difficulty, learner context, and available resources, while also accounting for different learning styles (visual, auditory, kinesthetic). MGM optimizes resource allocation, assigns suitable time spans, and scales difficulty to maintain learner engagement.

Mathematically, for sub-objective , the generation function is:

where m denotes the number of generated strategies and represents a suitability score computed as:

with denoting evaluation components (e.g., relevance, complexity, resource efficiency) and their corresponding weights. This process yields a ranked pool of adaptive strategies for the subsequent SSM module.

3.6. Strategy Selection Module (SSM)

The SSM selects the optimal teaching strategy from MGM’s candidates through reinforcement learning. The selection is modeled as a Markov Decision Process, where the state space represents learner progress and context, the action space corresponds to candidate strategies, and the reward reflects learning improvement and efficiency. The objective is to maximize the expected cumulative reward:

where is a discount factor and denotes the reward at time t.

Two approaches are adopted: (1) Deep Q-Network (DQN), which estimates the Q-value function using neural networks with experience replay and target networks to stabilize learning; and (2) Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), which directly updates the policy through a clipped surrogate objective:

ensuring stable policy refinement. DQN enables robust value estimation, while PPO ensures smooth policy adaptation, together achieving stable and adaptive instructional decision-making.

3.7. Knowledge and Experience Memory Module (KEMM)

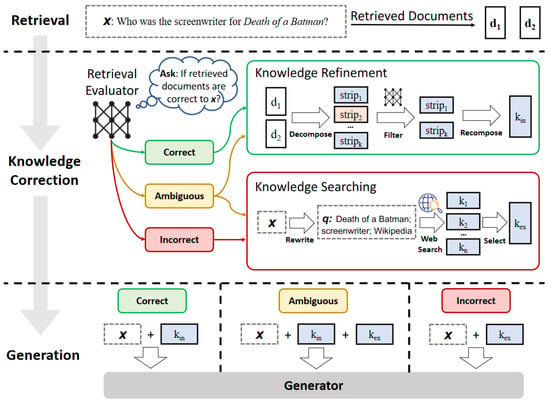

The KEMM serves as the long-term memory of the system, storing domain knowledge and prior experiences within a vector database for efficient retrieval and continuous learning. It adopts the Corrective Retrieval-Augmented Generation (CRAG) [] paradigm, which refines conventional RAG by evaluating retrieved information and filtering unreliable content before generation. As shown in Figure 2, this design ensures that only highly relevant and accurate information contributes to final outputs, improving both precision and trustworthiness.

Figure 2.

Overview of the Corrective Retrieval-Augmented Generation (CRAG) mechanism [].

CRAG first scores retrieved documents based on semantic relevance, then activates different corrective actions according to confidence levels: high-confidence results are directly used, low-confidence ones trigger extended searches, and ambiguous results combine initial and supplementary data. The refined knowledge is then decomposed into granular units, filtered, and recomposed to maximize contextual fidelity. Formally, the CRAG-enhanced generation process is:

where x is the query, the refined knowledge, and y the generated output. The module continuously updates its database with user feedback, ensuring progressive improvement and adaptability over time.

3.8. Framework Implementation for Computer Science Education

To demonstrate practical applicability, SP-TeachLLM is instantiated through three domain-specific agents: (1) the Programming Fundamentals Agent (PFA), which teaches coding syntax, logic, and debugging using interactive tools such as Repl.it and SonarQube; (2) the Data Structures and Algorithms Agent (DSA), which explains key algorithmic concepts using visualization tools like VisuAlgo and adaptive practice via LeetCode; and (3) the Machine Learning Agent (MLA), which introduces models such as decision trees and neural networks through Colab-based implementations and dataset-driven exercises on Kaggle. Each agent applies CDM for topic decomposition, MGM for strategy generation, SSM for adaptive selection, TRM for feedback evaluation, and KEMM for personalized content recommendations.

3.9. Integration of Educational Theories

The SP-TeachLLM framework is guided by educational theories through a coordinating LLM that synthesizes information from all modules and interacts with students. It integrates Bloom’s Taxonomy for hierarchical learning progression, Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development for scaffolded support, Cognitive Load Theory for managing information complexity, Constructivist Learning Theory for interactive engagement, and Self-Determination Theory for fostering motivation. By dynamically applying these principles, the coordinating LLM ensures that instructional strategies remain pedagogically sound while adapting to individual learner contexts.

The corresponding implementation details—including model configurations and interaction procedures—are provided in the following experiment section.

4. Experiments

4.1. Benchmarks for Code Generation

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed SP-TeachLLM framework in code generation and instructional reasoning, we employ two widely recognized programming benchmarks: HumanEval [] and MBPP []. Both datasets assess the ability of models to generate correct and functional code from natural language descriptions.

4.1.1. HumanEval

HumanEval, introduced by OpenAI, is a standard benchmark for assessing code generation models in Python 3.8. It consists of 164 programming tasks, each providing a natural language description, a Python function signature, and one or more unit tests. The model must generate a function implementation that satisfies the specification and passes all test cases. HumanEval primarily evaluates a model’s ability to perform algorithmic reasoning, implement logical control structures, and ensure syntactic and functional correctness.

4.1.2. MBPP (Mostly Basic Programming Problems)

The MBPP dataset comprises 974 Python programming problems drawn from real-world coding exercises. Each task includes a natural language prompt, a reference solution, and comprehensive test cases. Unlike HumanEval, MBPP emphasizes diversity in problem types—covering algorithm design, data manipulation, and computational logic—making it suitable for evaluating generalization and robustness in code synthesis. The inclusion of detailed test suites ensures that models are evaluated on both correctness and robustness, providing a more holistic assessment of practical code generation ability.

4.2. Experimental Setup

To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of AI tutors in programming education, we designed experiments involving a range of large language models (LLMs) serving as both tutors and simulated students.

4.2.1. AI Tutor Models

Five state-of-the-art LLMs are selected as AI tutors—GPT-4o, GPT-4, LLaMA-3-70B, Claude 3 Opus, and TeachLM []—each offering distinct reasoning and pedagogical characteristics. GPT-4o represents OpenAI’s latest multimodal model with enhanced reasoning and contextual understanding, while TeachLM is a recently introduced educational LLM fine-tuned on over 100,000 h of authentic human tutoring dialogues to improve multi-turn teaching quality and feedback coherence. Table 1 summarizes their architectures and training emphases.

Table 1.

Specifications of AI tutor models.

Each tutor was fine-tuned on a curated corpus of 100,000 programming-related question–answer pairs, encompassing topics from basic syntax to advanced algorithms. Fine-tuning employed supervised learning with a learning rate of , batch size of 32, and 3 epochs. Post-training, the models were validated on a held-out test set to ensure improved instructional coherence and accuracy in programming-related responses.

4.2.2. Student Models

To simulate learners with different knowledge levels, four LLMs of varying scales were chosen as student models: Claude 3 Haiku, Claude 3 Sonnet, GPT-3.5 Turbo, and LLaMA-3-8B. Their specifications are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Specifications of student models.

These models simulate students at different proficiency levels, allowing the assessment of tutor adaptability across beginner and advanced learning scenarios. Each student’s baseline ability in Python programming was measured before interacting with the tutors.

4.2.3. Experimental Procedure

The evaluation consisted of 50 Python programming topics, ranging from fundamental syntax to advanced concepts such as decorators and metaclasses. For each topic, ten rounds of tutor–student interaction were conducted, during which the AI tutor provided explanations, feedback, and corrective guidance.

Performance was quantified through the Code Generation Accuracy (CGA), which measures the percentage of student-generated code solutions that successfully pass all provided test cases:

This metric reflects both the syntactic correctness and functional reliability of the code produced by student models after interacting with different AI tutors.

4.3. Experimental Results

Table 3 and Table 4 summarize the code generation accuracy (%) of different student models under various AI tutor configurations on the HumanEval and MBPP benchmarks, respectively. The values in parentheses indicate relative improvements achieved by integrating the SP-TeachLLM framework.

Table 3.

Code generation accuracy on the HumanEval benchmark.

Table 4.

Code generation accuracy on the MBPP benchmark.

Overall, the results demonstrate consistent and substantial performance improvements across all teacher–student configurations when applying the SP-TeachLLM framework. Regardless of the tutor model, every student exhibits measurable gains in code generation accuracy, confirming the framework’s general effectiveness in enhancing LLM-based programming instruction.

Among teacher models, LLaMA-3-70B and GPT-4o consistently achieve the highest improvement margins across both datasets, suggesting stronger pedagogical alignment between their reasoning mechanisms and the student models. TeachLM, which is specifically optimized for educational dialogue generation, achieves competitive performance, validating that conversationally aligned teaching models can also benefit from SP-TeachLLM’s structured instructional reasoning process.

Notably, smaller student models—such as GPT-3.5-Turbo and LLaMA-3-8B—benefit most, achieving relative improvements of up to 19.1% on MBPP, indicating that SP-TeachLLM remains particularly effective in elevating the capabilities of lightweight models with limited reasoning capacity.

Task-specific trends reveal that the improvements on MBPP generally exceed those on HumanEval, implying that the framework is especially effective for diverse, concept-driven programming problems rather than highly structured algorithmic ones. Additionally, an inverse relationship is observed between model size and relative improvement, reinforcing that smaller models gain proportionally more from guided instruction.

In summary, these findings validate that the SP-TeachLLM framework not only enhances code generation accuracy but also performs competitively against specialized educational models such as TeachLM, while providing a scalable and cost-efficient approach for improving smaller, resource-constrained LLMs in programming education.

4.4. Ablation Study

To evaluate the contribution of each component within the SP-TeachLLM framework, we conducted an ablation study using a fixed teacher model (LLaMA-3-70B) and multiple student models. This study aims to quantify the relative importance of each module by measuring performance degradation when individual components are removed.

Five ablation configurations were examined:

- Without Strategy Selection Module (SSM): The reinforcement learning-based strategy selection mechanism was disabled, and a fixed non-adaptive strategy was applied to all students.

- Without Curriculum Decomposition Module (CDM): Learning objectives were not decomposed into sub-objectives, forcing the system to teach the entire concept in a single, monolithic session.

- Without Knowledge and Experience Memory Module (KEMM): The system did not retain knowledge from previous teaching sessions, eliminating adaptive behavior based on learning history.

- Without Multi-Strategy Generation Module (MGM): Only a single, predefined teaching strategy was generated for each sub-objective, removing strategic diversity.

- Without Teaching Reflection Module (TRM): No post-session reflection or adjustment was performed, preventing iterative improvement of teaching strategies.

The impact of these ablations on code generation accuracy (CGA) was evaluated using the HumanEval benchmark. Results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Ablation study results on the HumanEval benchmark using LLaMA-3-70B as the teacher model.

The results demonstrate that the Strategy Selection Module (SSM) has the largest impact, with a performance drop of approximately 6.1–6.2% across all student models. This confirms the critical role of adaptive strategy selection in optimizing learning outcomes. The Curriculum Decomposition Module (CDM) also proves essential; its removal causes a 4.0–4.7% reduction, highlighting the importance of decomposing complex objectives into manageable learning units.

The Knowledge and Experience Memory Module (KEMM) yields a 3.1–3.5% decline when removed, indicating that long-term memory and adaptive recall are key to effective personalization. In contrast, the Multi-Strategy Generation Module (MGM) shows smaller drops (2.0–2.5%), implying that while strategy diversity enhances engagement, it contributes less than dynamic adaptation. Finally, the Teaching Reflection Module (TRM) yields the smallest effect (1.0–1.5%), suggesting that reflective refinement primarily benefits long-term learning rather than immediate performance.

Overall, these findings emphasize that SSM, CDM, and KEMM are the most influential components driving adaptive and personalized learning within SP-TeachLLM, while MGM and TRM play supportive yet meaningful roles in sustaining overall system effectiveness.

It is noteworthy that the ablation experiments presented above were performed on HumanEval to isolate module-level effects under a controlled algorithmic environment where task homogeneity minimizes confounding factors. While this setup supports clean attribution of performance differences to individual modules, it does not capture how module importance may vary across more diverse, concept-driven benchmarks. Given that SP-TeachLLM exhibits consistently larger performance gains on MBPP, we expect components such as the Knowledge and Experience Memory Module (KEMM), which facilitate contextual integration and long-term knowledge reuse, to play a more pronounced role on MBPP. Extending the ablation study to MBPP is therefore an important direction for future work.

5. Discussion

Our results demonstrate that SP-TeachLLM consistently enhances the teaching effectiveness of a broad range of tutor models, including GPT-4o [], GPT-4 [], LLaMA-3-70B [], Claude 3 Opus [], and TeachLM []. Across both HumanEval and MBPP, every tutor model benefits from the framework, with the strongest gains observed for smaller or less capable student models such as GPT-3.5-Turbo [] and LLaMA-3-8B []. These findings indicate that SP-TeachLLM provides complementary pedagogical structure that is not present in conventional LLM tutors, enabling more coherent instructional planning and more targeted feedback.

When compared to existing LLM-based tutoring approaches such as TeachLM [], which improves teaching quality through large-scale educational fine-tuning, our SP-TeachLLM takes a different perspective by introducing a multi-module instructional architecture independent of the underlying LLM backbone. The observed improvements on top of TeachLM suggest that structured curriculum decomposition, multi-strategy generation, and reinforcement-based strategy selection contribute benefits that are orthogonal to model-centric fine-tuning. In this sense, our SP-TeachLLM does not replace prior LLM-tutor designs but provides a general pedagogical layer that can be applied to any tutor model.

From a sustainability perspective, a key advantage of our SP-TeachLLM lies in its ability to substantially boost the performance of lightweight student models. By reducing reliance on extremely large models during evaluation and practice, the framework supports more energy-efficient and cost-effective deployment in real educational environments.

6. Study Limitations and Scope

This study evaluates SP-TeachLLM using LLM-based simulated students, which enables controlled, scalable, and reproducible experiments focused on algorithmic instructional optimization. While this design effectively isolates the contributions of CDM, MGM, SSM, KEMM, and TRM, it also introduces a limitation in external validity. The findings should therefore be interpreted as evidence of policy-learning capability rather than direct validation of human learning outcomes. Extending the framework to real learners represents a crucial direction for future work.

Moreover, the current evaluation does not explicitly model the risk that human learners might rely on external AI tools (e.g., commercial code assistants) during assessment. Our primary metric, Code Generation Accuracy (CGA), captures task-level performance but not the provenance of a solution. Designing integrity-aware evaluation protocols and interfaces that distinguish genuine skill acquisition from AI-assisted shortcutting is therefore left as important future work.

Finally, the present evaluation focuses on outcome-based metrics using LLM-simulated learners and does not model process-level indicators of authentic learning, such as intermediate reasoning steps, self-explanations, or revision patterns. Although CGA measures task success, it does not capture the provenance or integrity of the solution process. Future extensions can leverage the TRM and SSM modules to incorporate process-oriented signals—e.g., step-wise solution traces, error-repair trajectories, and interaction logs—enabling the framework to assess and encourage authentic learning behaviors when deployed with human students.

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

In this paper, we presented SP-TeachLLM, a novel framework that integrates LLMs with established educational theories to create an intelligent tutoring system for programming education. The framework’s modular architecture—comprising the Curriculum Decomposition Module (CDM), Multi-strategy Generation Module (MGM), Strategy Selection Module (SSM), Knowledge and Experience Memory Module (KEMM), and Teaching Reflection Module (TRM)—enables adaptive and personalized learning experiences. Experimental results demonstrate that SP-TeachLLM significantly improves students’ learning outcomes, particularly in code generation accuracy and problem-solving capability, highlighting the potential of combining AI technologies with pedagogical principles.

A key strength of SP-TeachLLM lies in its dynamic adaptability. Through reinforcement learning within the SSM, the system continuously refines its teaching strategies in response to learners’ progress and feedback, ensuring personalized instructional paths aligned with individual needs. This adaptive mechanism underscores the framework’s ability to bridge real-time AI optimization with long-term educational objectives.

Looking forward, future research may focus on three primary directions. First, the reinforcement learning component can be enhanced through advanced algorithms such as model-based or hierarchical RL to further improve decision-making in complex educational scenarios. Second, incorporating refined learner modeling and insights from educational psychology could allow the system to better accommodate diverse cognitive styles, motivations, and engagement patterns. Finally, improving the scalability and interpretability of SP-TeachLLM will be essential for deployment in large-scale or classroom environments, enabling transparent and trustworthy AI-assisted teaching.

In conclusion, SP-TeachLLM represents a substantial step toward intelligent, personalized tutoring. Its synergy of deep learning and educational theory provides a strong foundation for the next generation of AI-driven education systems, paving the way for more adaptive, equitable, and effective learning experiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H. and X.Y.; methodology, S.H. and Y.S.; software, Y.S.; validation, S.H. and Y.S.; formal analysis, S.H.; investigation, S.H.; resources, X.Y.; data curation, Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.; writing—review and editing, S.H. and X.Y.; visualization, S.H.; supervision, X.Y.; project administration, S.H.; funding acquisition, X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are publicly available. The HumanEval dataset can be accessed at https://github.com/openai/human-eval (accessed on 20 November 2025), and the MBPP dataset is available at https://github.com/google-research/google-research/tree/master/mbpp (accessed on 20 November 2025). No new datasets were generated in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CDM | Curriculum Decomposition Module |

| CRAG | Corrective Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| CGA | Code Generation Accuracy |

| DSA | Data Structures and Algorithms Agent |

| KEMM | Knowledge and Experience Memory Module |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| MGM | Multi-Strategy Generation Module |

| MLA | Machine Learning Agent |

| PFA | Programming Fundamentals Agent |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| SSM | Strategy Selection Module |

| TRM | Teaching Reflection Module |

| SP-TeachLLM | Self-Planning Teaching Framework with Large Language Models |

References

- Timchenko, V.V.; Trapitsin, S.Y.; Apevalova, Z.V. Educational technology market analysis. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference Quality Management, Transport and Information Security, Information Technologies (IT&QM&IS), Yaroslavl, Russia, 7–11 September 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 612–617. [Google Scholar]

- Luckin, R.; Holmes, W.; Griffiths, M.; Forcier, L.B. Intelligence Unleashed: An Argument for AI in Education; Pearson Education: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.; Bi, T.; Wang, J.; Zeng, J.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, T.; Wu, Q.; Wu, S. Empowering the V2X network by integrated sensing and communications: Background, design, advances, and opportunities. IEEE Netw. 2022, 36, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, Q.; Dutkiewicz, E.; Jiang, T. Cost-effective foliage penetration human detection under severe weather conditions based on auto-encoder/decoder neural network. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 6, 6190–6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.B. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.14165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; Huang, X.; Wu, C.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, G.; Pu, Y.; Lei, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; et al. When large language models meet personalization: Perspectives of challenges and opportunities. World Wide Web 2024, 27, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koedinger, K.R.; D’Mello, S.; McLaughlin, E.A.; Pardos, Z.A.; Rosé, C.P. Data mining and education. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2013, 4, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, B.S.; Engelhart, M.D.; Furst, E.J.; Hill, W.H.; Krathwohl, D.R. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain; Longmans, Green and Co.: London, UK, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cogn. Sci. 1988, 12, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. Toward a Theory of Instruction; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell, J.R. AI in CAI: An artificial-intelligence approach to computer-assisted instruction. IEEE Trans. Man-Mach. Syst. 1970, 11, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R.; Corbett, A.T.; Koedinger, K.R.; Pelletier, R. Cognitive tutors: Lessons learned. J. Learn. Sci. 1995, 4, 167–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, A.T.; Anderson, J.R. Knowledge tracing: Modeling the acquisition of procedural knowledge. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 1994, 4, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piech, C.; Bassen, J.; Huang, J.; Ganguli, S.; Sahami, M.; Guibas, L.J.; Sohl-Dickstein, J. Deep knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; pp. 505–513. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, R.S. Stupid tutoring systems, intelligent humans. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2016, 26, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E.; Seßler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E.; et al. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikalishvili, S. Unlocking the potential of GPT-3 in education: Opportunities, limitations, and recommendations for effective integration. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2024, 32, 5587–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzullo, E.; Bulut, O.; Wongvorachan, T.; Tan, B. Learning analytics in the era of large language models. Analytics 2023, 2, 877–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilicita, A.; Barra, E. LLMs in Education: Evaluation GPT and BERT Models in Student Comment Classification. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakos, M.; Azevedo, R.; Brusilovsky, P.; Cukurova, M.; Dimitriadis, Y.; Hernandez-Leo, D.; Järvelä, S.; Mavrikis, M.; Rienties, B. The promise and challenges of generative AI in education. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2025, 44, 2518–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.02155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.S.; Yacef, K. The state of educational data mining in 2009: A review and future visions. J. Educ. Data Min. 2009, 1, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yudelson, M.V.; Koedinger, K.R.; Gordon, G.J. Individualized bayesian knowledge tracing models. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence in Education: 16th International Conference, AIED 2013, Memphis, TN, USA, 9–13 July 2013; Proceedings 16. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Papamitsiou, Z.; Economides, A.A. Learning analytics and educational data mining in practice: A systematic literature review of empirical evidence. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2014, 17, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Narvekar, S.; Stone, P. Learning curriculum policies for reinforcement learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.00285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Mao, C.; Luo, Y. KG-BERT: BERT for knowledge graph completion. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.03193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. Psychology and Epistemology: Towards a Theory of Knowledge; Grossman Publishers: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.H.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain of thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.11903. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Zhao, D.; Yu, Y.; Cao, S.; Narasimhan, K.; Cao, Y.; Huang, W. ReAct: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.03629. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Yu, D.; Zhao, J.; Shafran, I.; Griffiths, T.; Cao, Y.; Narasimhan, K. Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 11809–11822. [Google Scholar]

- Madaan, A.; Tsvetkov, Y.; Klein, D.; Abbeel, P. Self-Refine: Iterative Refinement with Self-Feedback. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.17651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinn, N.; Labash, O.; Madaan, A.; Tsvetkov, Y.; Klein, D.; Abbeel, P. Reflexion: Language agents with verbal reinforcement learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.11366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Bi, T.; Wang, J.; Zeng, J.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, T.; Wu, S. A climate adaptation device-free sensing approach for target recognition in foliage environments. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1003015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.Q.; Gu, J.C.; Zhu, Y.; Ling, Z.H. Corrective retrieval augmented generation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.15884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Tworek, J.; Jun, H.; Yuan, Q.; Pinto, H.P.D.O.; Kaplan, J.; Edwards, H.; Burda, Y.; Joseph, N.; Brockman, G.; et al. Evaluating large language models trained on code. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.03374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.; Odena, A.; Nye, M.; Bosma, M.; Michalewski, H.; Dohan, D.; Jiang, E.; Cai, C.; Terry, M.; Le, Q.; et al. Program synthesis with large language models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.07732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perczel, J.; Chow, J.; Demszky, D. TeachLM: Post-Training LLMs for Education Using Authentic Learning Data. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.05087. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, A.; Lerer, A.; Goucher, A.P.; Perelman, A.; Ramesh, A.; Clark, A.; Ostrow, A.; Welihinda, A.; Hayes, A.; Radford, A.; et al. Gpt-4o system card. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.21276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthropic. The Claude 3 Model Family: Opus, Sonnet, Haiku (Model Card). 2024. Available online: https://www-cdn.anthropic.com/de8ba9b01c9ab7cbabf5c33b80b7bbc618857627/Model_Card_Claude_3.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Ye, J.; Chen, X.; Xu, N.; Zu, C.; Shao, Z.; Liu, S.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Gong, C.; Shen, Y.; et al. A comprehensive capability analysis of gpt-3 and gpt-3.5 series models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.10420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Yang, A.; Fan, A.; et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.21783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).