Illuminating Industry Evolution: Reframing Artificial Intelligence Through Transparent Machine Reasoning

Abstract

1. Introduction

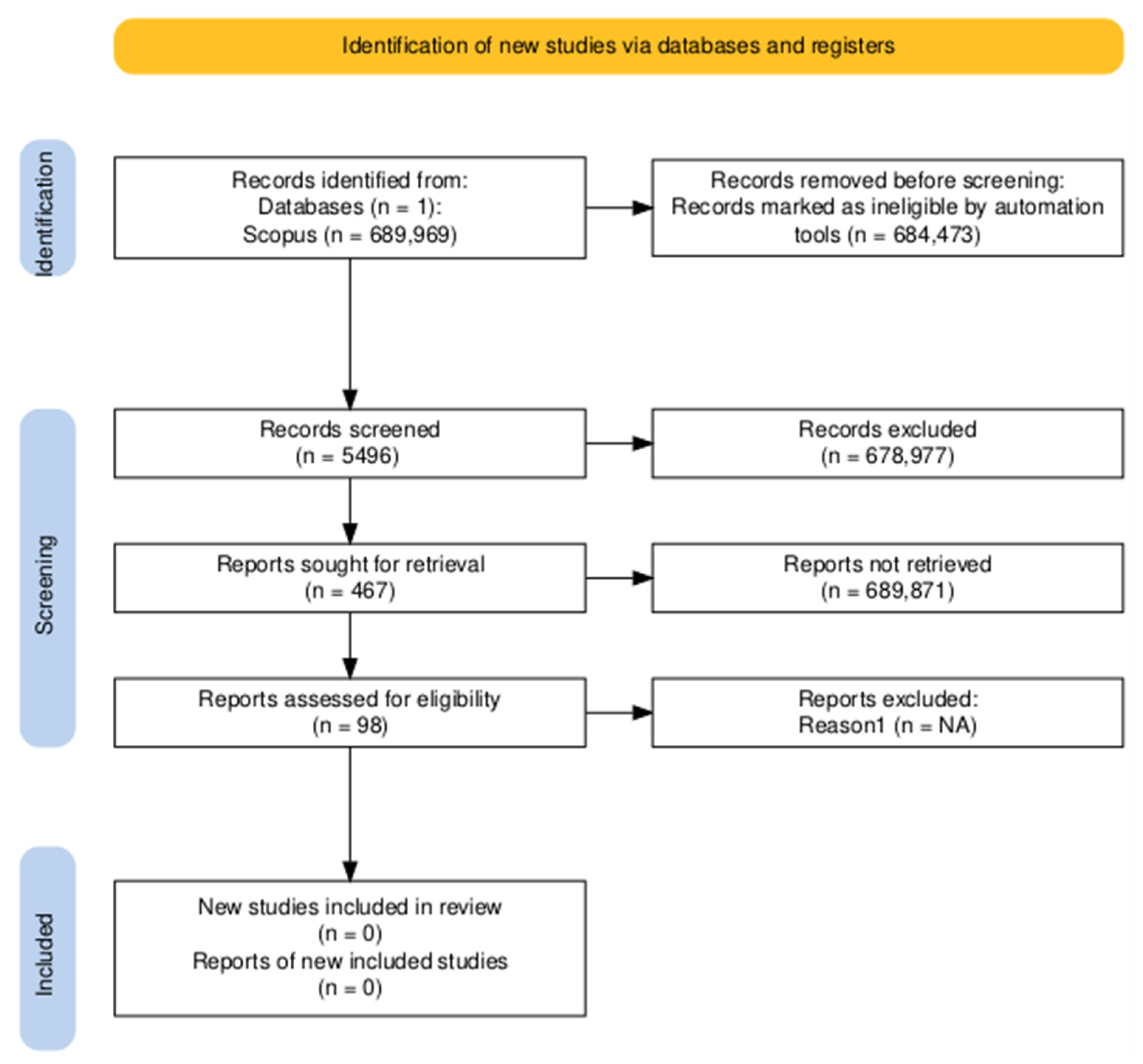

2. Materials and Methods

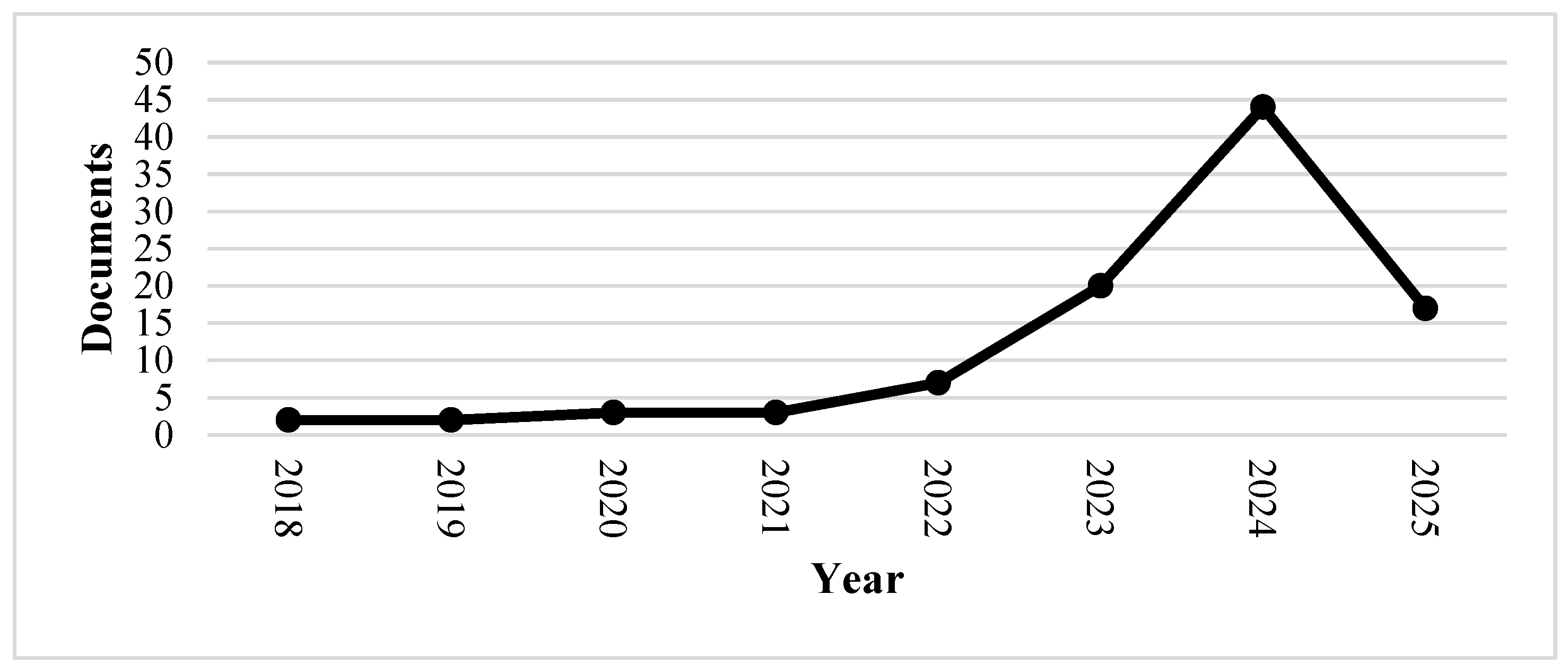

3. Publication Distribution

3.1. Search Parameters and Dataset Scope

- Source type: Peer-reviewed journal articles, books, book chapters, and conference papers;

- Language: English;

- Publication years: ≤June 2025;

- Subject areas: Computer Science, Engineering, Decision Sciences, Business, Management & Accounting;

- Inclusion criteria: Documents addressing explainability in industrial or decision-making contexts;

- Exclusion criteria: Preprints, theses, and grey literature were excluded to maintain quality; duplicates were removed through metadata comparison and manual verification.

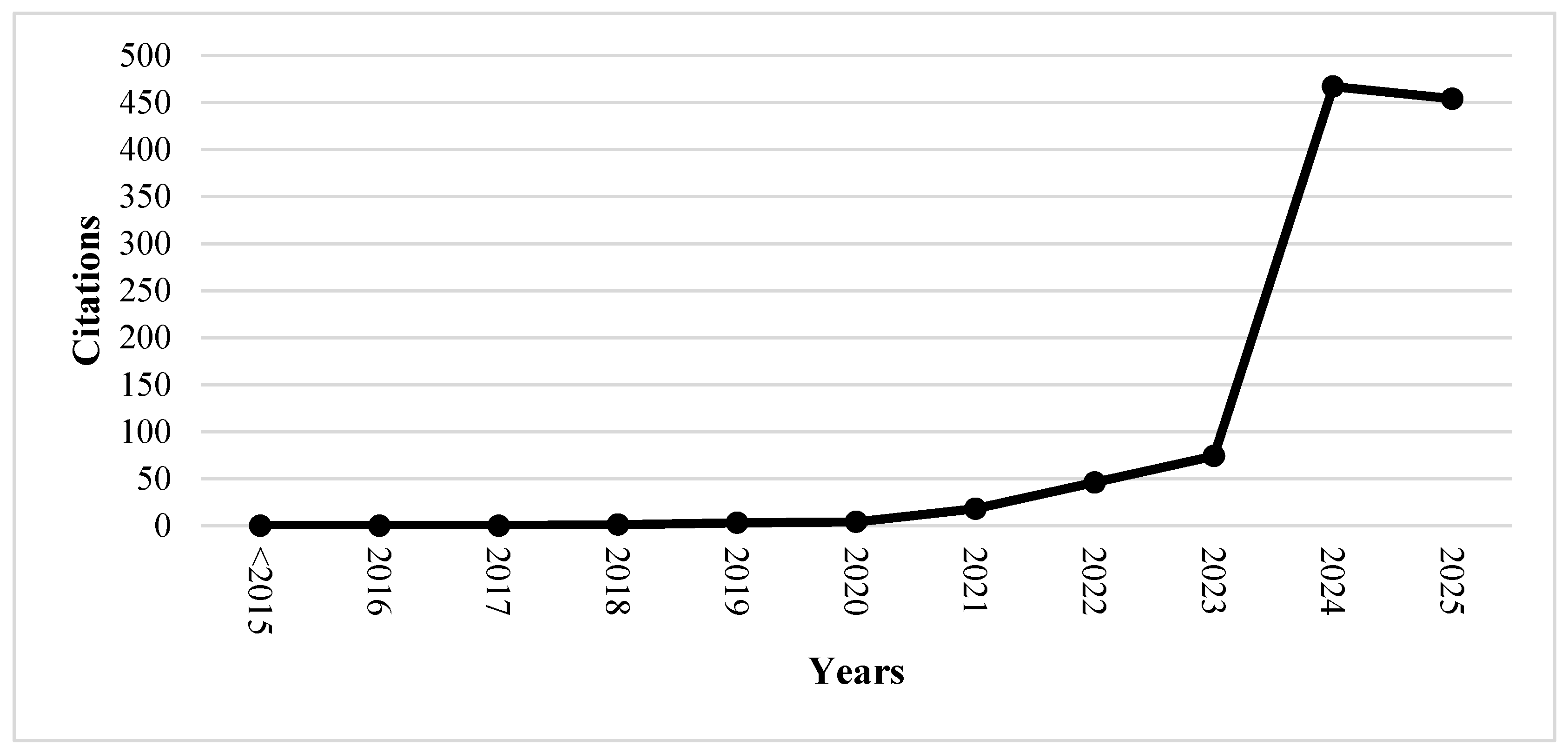

3.2. Temporal Evolution of Publications

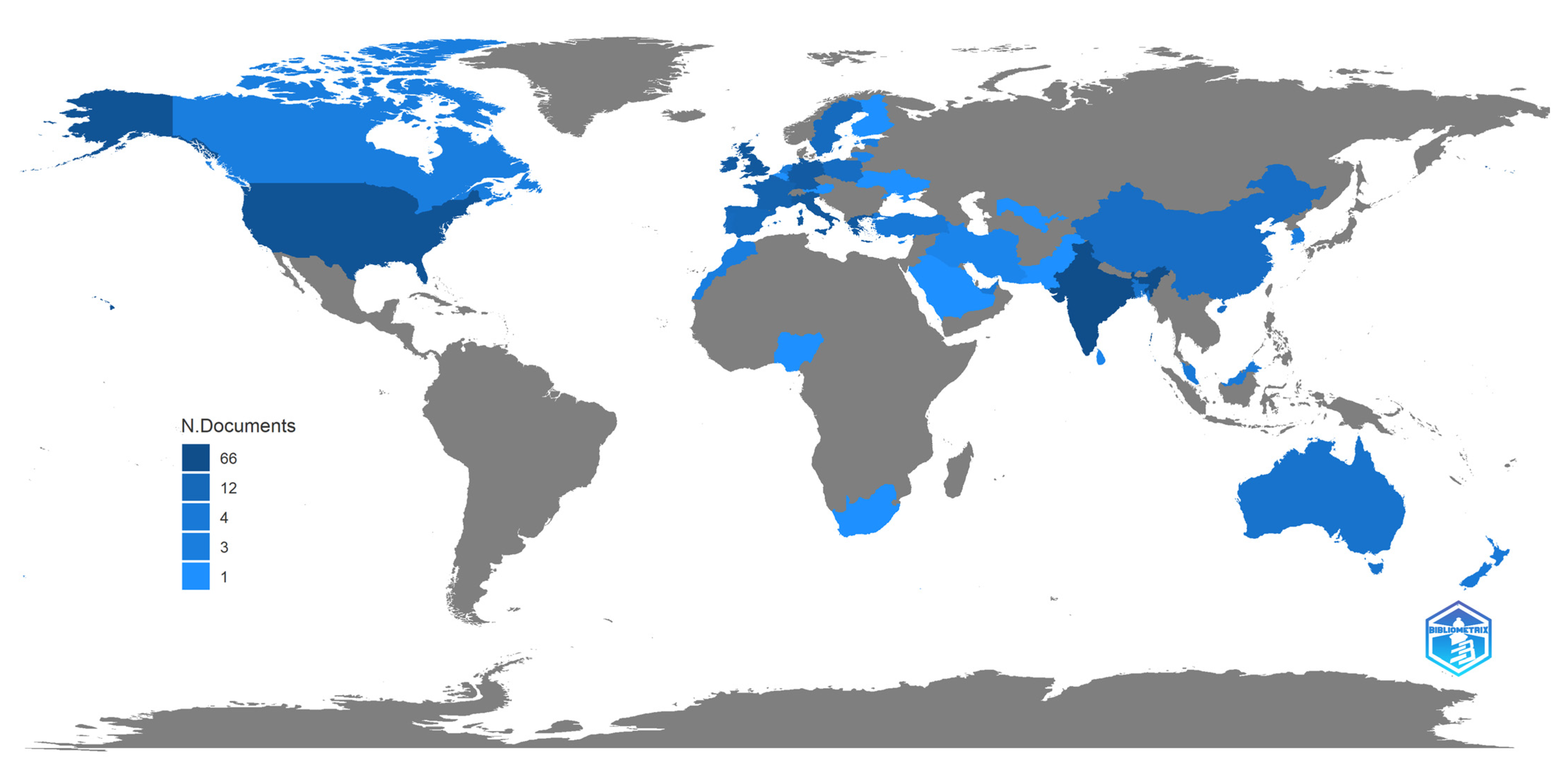

3.3. Geographic Distribution and Research Biases

3.4. Core Journals and Thematic Concentration

3.5. Disciplinary Landscape and Research Impact

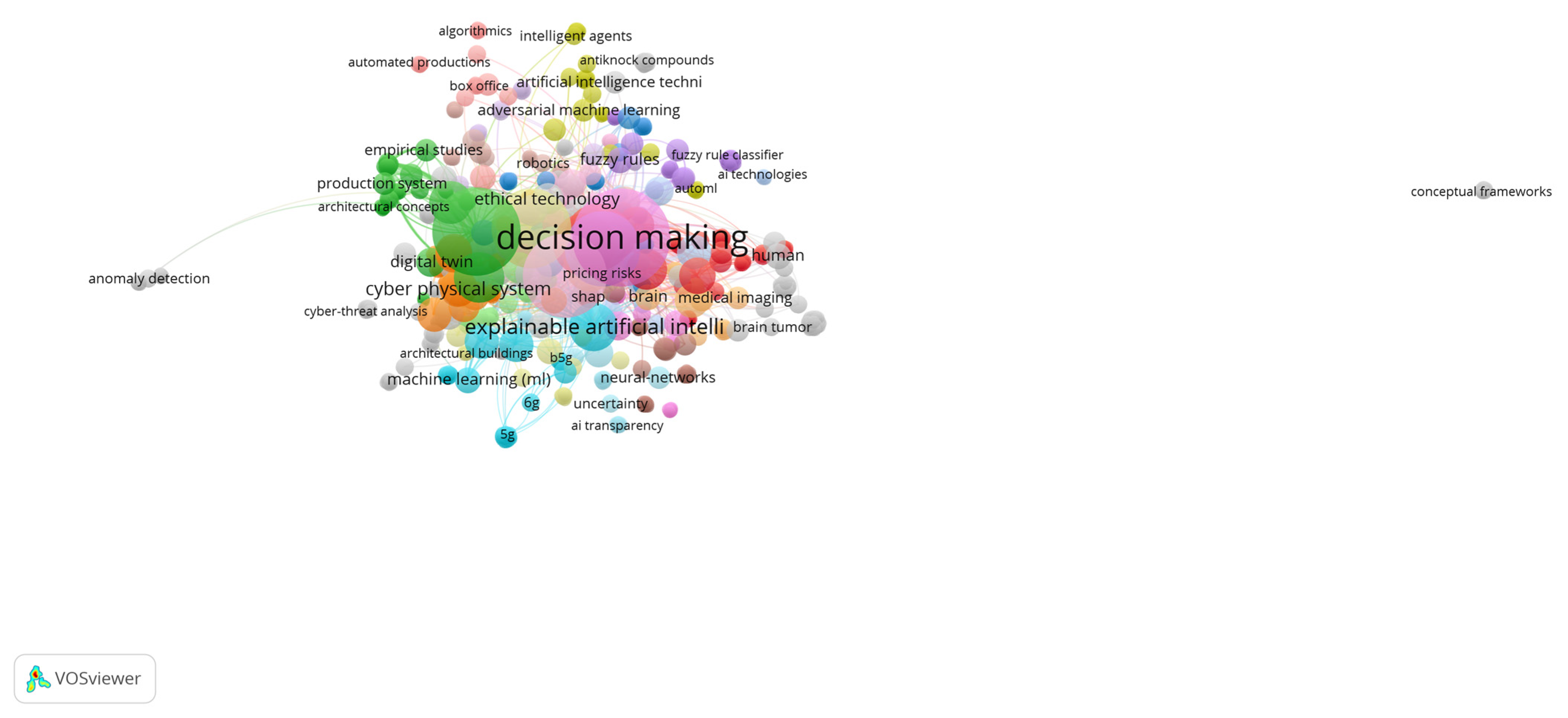

3.6. Keyword Co-Occurrence and Thematic Networks

- Technical explainability (machine learning, deep learning, neural networks);

- Industrial application (predictive maintenance, resource optimisation);

- Ethical and organisational dimensions (trust, transparency, accountability).

3.7. Three-Field Plot: Authors, Keywords, and References

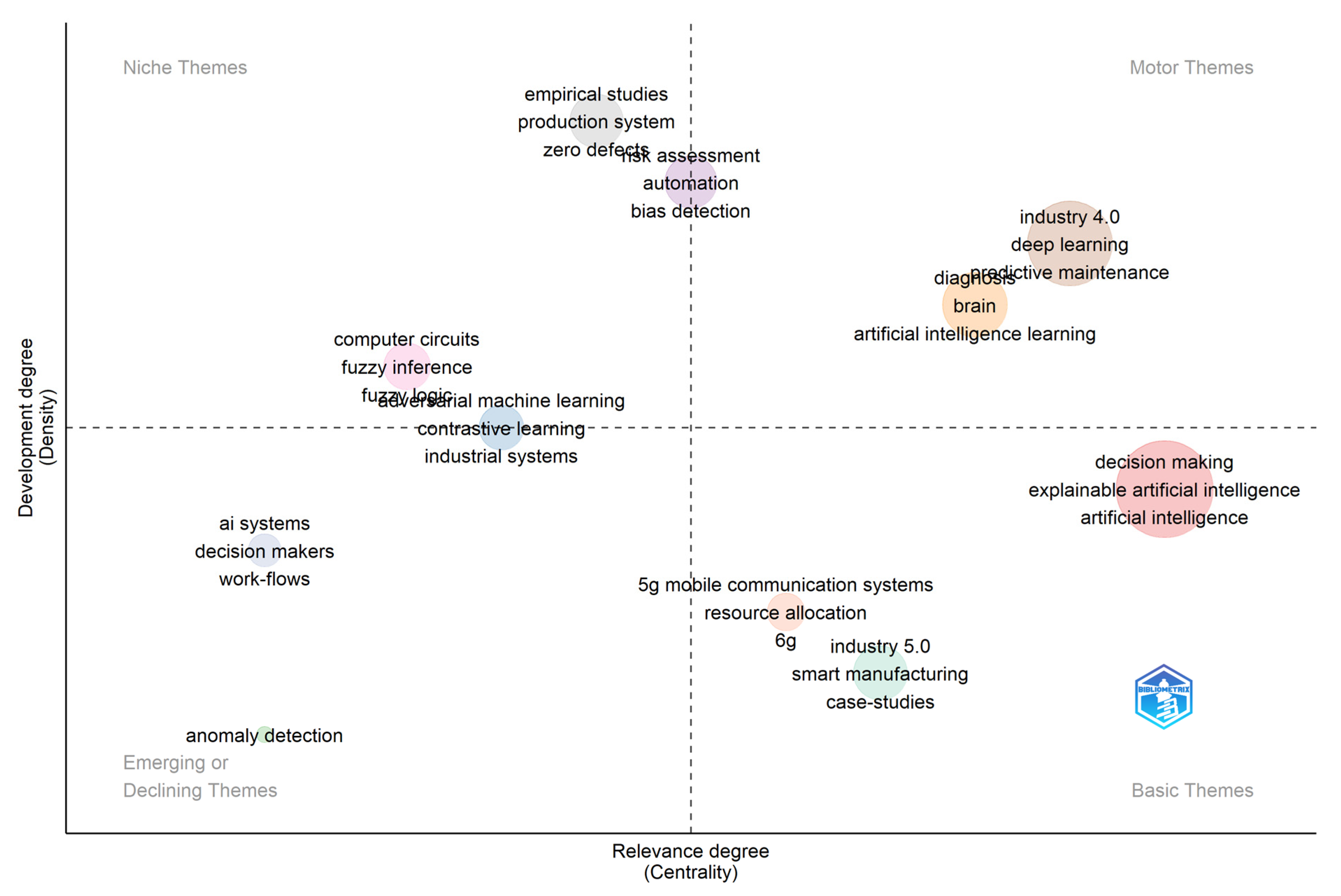

3.8. Thematic Map Analysis

3.9. Co-Citation Network Analysis

4. Theoretical Perspectives

4.1. Goals for Pursuing Explainability in XAI

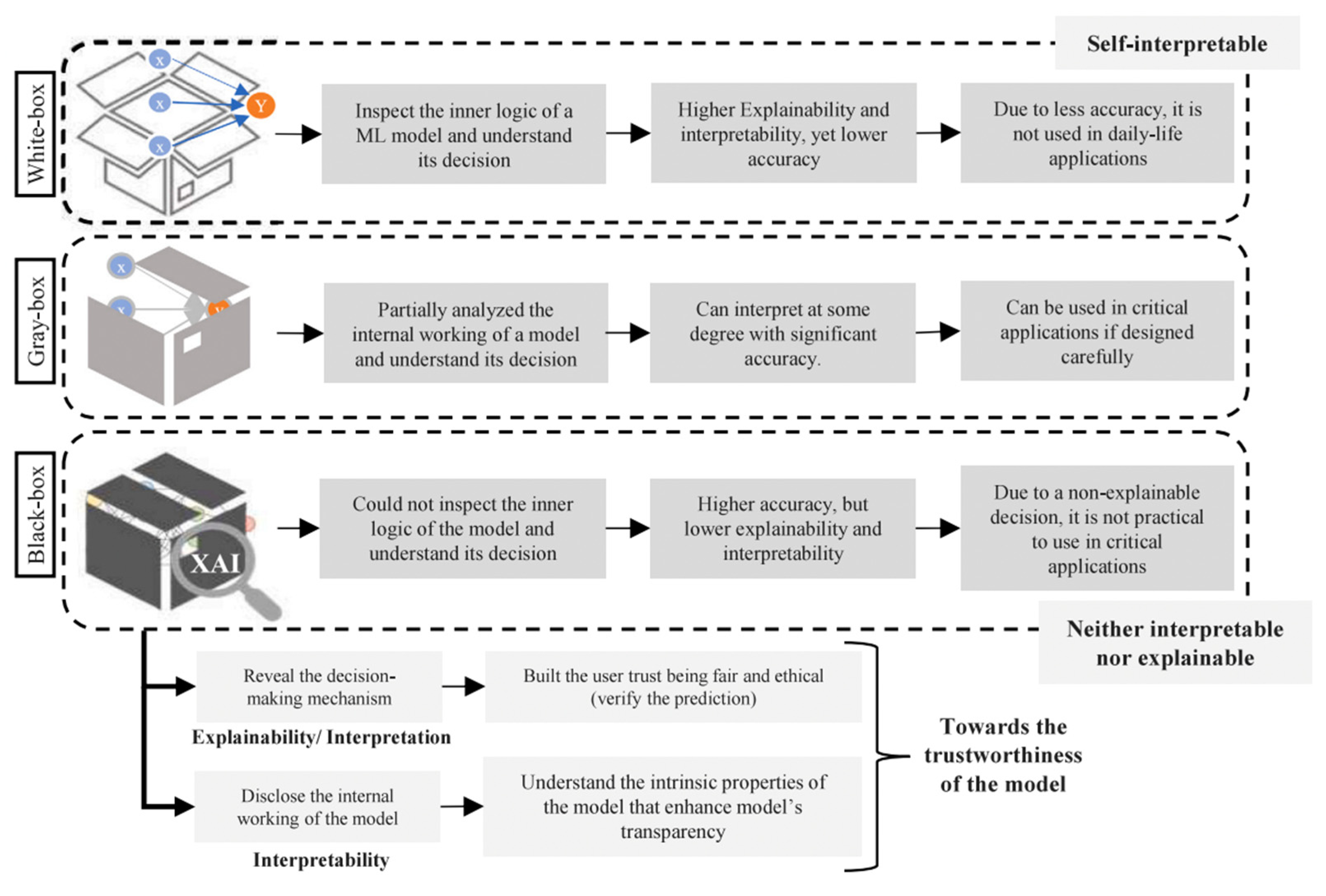

4.1.1. Trustworthiness

4.1.2. Intelligibility

4.1.3. Transparency

- Simulatability

- Decomposability

- Algorithmic Transparency

4.1.4. Comprehensibility

4.1.5. Causality

4.1.6. Transferability

4.1.7. Informativeness

4.1.8. Interactivity

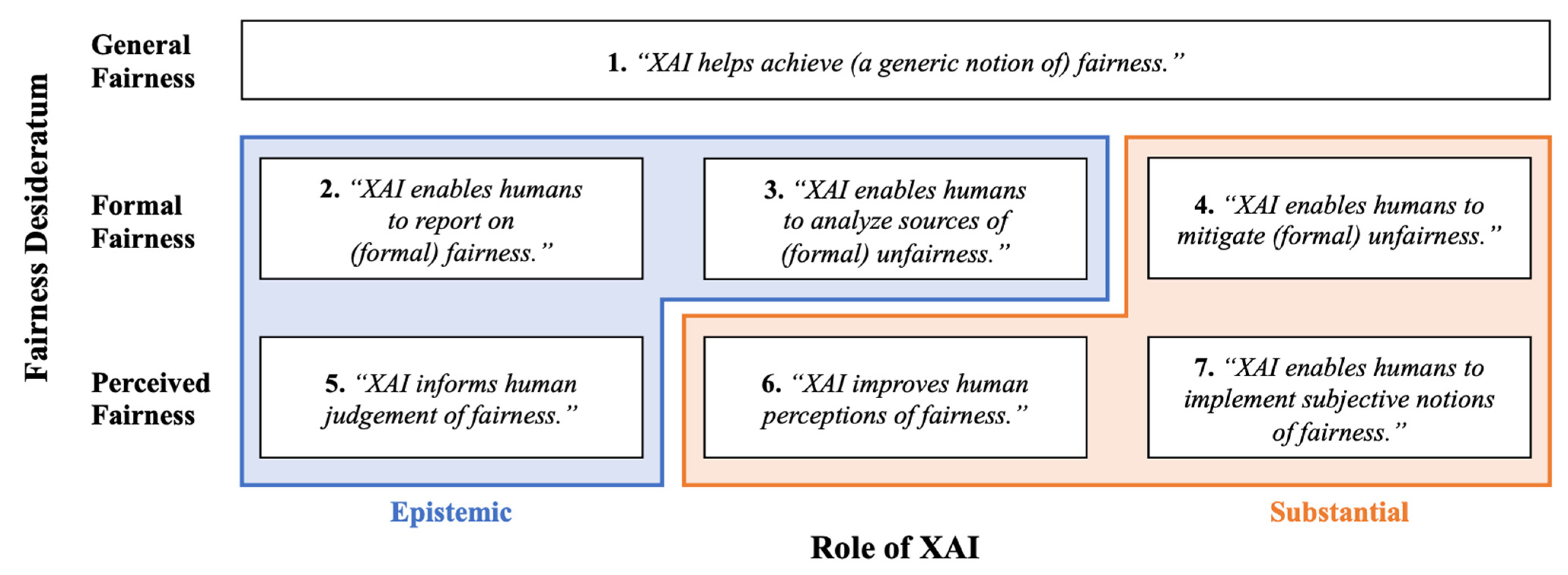

4.1.9. Improve Model Bias Understanding and Fairness

4.1.10. Accessibility

4.1.11. Privacy Awareness

4.1.12. Regulatory Compliance

4.2. XAI Techniques for Improving Explainability

4.2.1. Counterfactual Reasoning

Prolixity

Sparcity

Plausibility

4.2.2. Causal Modelling

4.2.3. Hybrid Neuro-Symbolic Frameworks

4.2.4. Natural Language Generation

4.2.5. Visual Analytics Tools

4.2.6. White-Box Modelling

4.2.7. Interpretable Learning Architectures

5. Conclusions

- Multi-Database Integration: Future systematic reviews should triangulate Scopus with databases such as Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, or Google Scholar to enhance coverage and reduce indexing bias.

- Longitudinal and Comparative Analyses: Investigations could track how XAI discourse evolves over time and across industrial sectors, mapping the diffusion of explainability practices between manufacturing, healthcare, finance, and logistics.

- Empirical Validation of the TMR Framework: Quantitative studies could operationalize and test the proposed Transparent Machine Reasoning framework through surveys, case studies, or mixed-method approaches.

- Cross-Cultural and Ethical Perspectives: Future work should examine how cultural, institutional, and legal contexts shape perceptions of explainability, fairness, and accountability in AI systems.

- Human-AI Interaction Metrics: Experimental research could measure the behavioural and cognitive effects of explainability tools (e.g., dashboards, visual analytics, or natural language explanations) on user trust, decision accuracy, and satisfaction.

- Policy and Governance Studies: Further exploration is needed into how explainability mechanisms can inform regulatory compliance and organisational governance, particularly within the broader transition toward Industry 5.0.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Documents | ≤2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2021 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counterfactual explanations for remaining useful life estimation within a Bayesian framework | 2025 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| An extensive bibliometric analysis of artificial intelligence techniques from 2013 to 2023 | 2025 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Generative AI in AI-Based Digital Twins for Fault Diagnosis for Predictive Maintenance in Industry 4.0/5.0 | 2025 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Enhancing transparency and trust in AI-powered manufacturing: A survey of explainable AI (XAI) applications in smart manufacturing in the era of industry 4.0/5.0 | 2025 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| How do ML practitioners perceive explainability? an interview study of practices and challenges | 2025 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| A cognitive digital twin for process chain anomaly detection and bottleneck analysis | 2025 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| A Comparative Analysis of LIME and SHAP Interpreters With Explainable ML-Based Diabetes Predictions | 2025 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 11 | 17 |

| Artificial Intelligence and Smart Technologies in Safety Management: A Comprehensive Analysis Across Multiple Industries | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Explainable artificial intelligence to increase transparency for revolutionizing healthcare ecosystem and the road ahead | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| On the Application of Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML) in Late-Stage Clinical Development | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Evaluative Item-Contrastive Explanations in Rankings | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Barriers to adopting artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies in nuclear power | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Intelligent decision support systems in construction engineering: An artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 15 | 24 |

| Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in finance: a systematic literature review | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 30 | 32 |

| Leveraging artificial intelligence for enhanced risk management in banking: A systematic literature review | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| An Interrogative Survey of Explainable AI in Manufacturing | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 9 | 15 |

| An explanation framework and method for AI-based text emotion analysis and visualisation | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 11 | 20 |

| Artificial intelligence in manufacturing: Enabling intelligent, flexible and cost-effective production through AI | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Recent trends and advances in machine learning challenges and applications for industry 4.0 | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Harnessing Deep Learning for Fault Detection in Industry 4.0: A Multimodal Approach | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| A Conceptual Framework for Predictive Digital Dairy Twins: Integrating Explainable AI and Hybrid Modeling | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Advancing Manufacturing Through Artificial Intelligence: Current Landscape, Perspectives, Best Practices, Challenges, and Future Direction | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Leveraging Information Flow-Based Fuzzy Cognitive Maps for Interpretable Fault Diagnosis in Industrial Robotics | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Potential Technological Advancements in the Future of Process Control and Automation | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Explainability of Brain Tumor Classification Based on Region | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Explainable AI for Industry 5.0: Vision, Architecture, and Potential Directions | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 9 | 15 |

| Insightful Clinical Assistance for Anemia Prediction with Data Analysis and Explainable AI | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Explainable AI for Cyber-Physical Systems: Issues and Challenges | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| Impact of social media posts’ characteristics on movie performance prior to release: an explainable machine learning approach | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Trustworthiness of the AI | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Explainable Predictive Maintenance: A Survey of Current Methods, Challenges and Opportunities | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 15 | 25 |

| Explainable AI for 6G Use Cases: Technical Aspects and Research Challenges | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 18 | 28 |

| Toward Transparent AI for Neurological Disorders: A Feature Extraction and Relevance Analysis Framework | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Translating Image XAI to Multivariate Time Series | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Explainable Predictive Maintenance of Rotating Machines Using LIME, SHAP, PDP, ICE | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 20 | 29 |

| AI-Based Task Classification with Pressure Insoles for Occupational Safety | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Moving Towards Explainable Artificial Intelligence Using Fuzzy Rule-Based Networks in Decision-Making Process | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Deep Learning in Industry 4.0: Transforming Manufacturing Through Data-Driven Innovation | 2024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 12 |

| Expl(AI)ned: The Impact of Explainable Artificial Intelligence on Users’ Information Processing | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 37 | 39 | 81 |

| ENIGMA: An explainable digital twin security solution for cyber–physical systems | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 22 | 21 | 46 |

| TEA-EKHO-IDS: An intrusion detection system for industrial CPS with trustworthy explainable AI and enhanced krill herd optimization | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 15 | 5 | 22 |

| An optimized model for network intrusion detection systems in industry 4.0 using XAI based Bi-LSTM framework | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 29 | 22 | 57 |

| An Explainable AI Framework for Artificial Intelligence of Medical Things | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Explainable AI for Breast Cancer Detection: A LIME-Driven Approach | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Explainable Artificial Intelligence: A Study of Current State-of-the-Art Techniques for Making ML Models Interpretable and Transparent | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| AI-enabled IoT Applications: Towards a Transparent Governance Framework | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Towards Explainable AI Validation in Industry 4.0: A Fuzzy Cognitive Map-based Evaluation Framework for Assessing Business Value | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| A novel Explainable Artificial Intelligence and secure Artificial Intelligence asset sharing platform for the manufacturing industry | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| XAI Requirements in Smart Production Processes: A Case Study | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| Introduction to artificial intelligence and current trends | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) for the Prediction of Diabetes Management: An Ensemble Approach | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 9 |

| Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) Based Analysis of Stress Among Tech Workers Amidst COVID-19 Pandemic | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 8 |

| A Review of Trustworthy and Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 61 | 48 | 114 |

| 6G-BRICKS: Developing a Modern Experimentation Facility for Validation, Testing and Showcasing of 6G Breakthrough Technologies and Devices | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Application of explainable artificial intelligence in medical health: A systematic review of interpretability methods | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 54 | 41 | 96 |

| Transparent Artificial Intelligence and Human Resource Management: A Systematic Literature Review | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| CHAIKMAT 4.0—Commonsense Knowledge and Hybrid Artificial Intelligence for Trusted Flexible Manufacturing | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Human-in-Loop: A Review of Smart Manufacturing Deployments | 2023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 15 | 4 | 21 |

| Towards big industrial data mining through explainable automated machine learning | 2022 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 18 | 12 | 48 |

| Internet-of-Explainable-Digital-Twins: A Case Study of Versatile Corn Production Ecosystem | 2022 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| Using an Explainable Machine Learning Approach to Minimize Opportunistic Maintenance Interventions | 2022 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| Resource Reservation in Sliced Networks: An Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) Approach | 2022 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 17 |

| Information Model to Advance Explainable AI-Based Decision Support Systems in Manufacturing System Design | 2022 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 9 |

| On the Intersection of Explainable and Reliable AI for Physical Fatigue Prediction | 2022 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 14 |

| Explainable AI for Industry 4.0: Semantic Representation of Deep Learning Models | 2022 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 12 | 5 | 26 |

| XAI for operations in the process industry—Applications, theses, and research directions | 2021 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| IEC 61499 Device Management Model through the lenses of RMAS | 2021 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 10 |

| A human cyber physical system framework for operator 4.0—artificial intelligence symbiosis | 2020 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 15 | 12 | 15 | 5 | 57 |

| Choose for AI and for explainability | 2020 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Depicting Decision-Making: A Type-2 Fuzzy Logic Based Explainable Artificial Intelligence System for Goal-Driven Simulation in the Workforce Allocation Domain | 2019 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 15 |

| A fuzzy linguistic supported framework to increase Artificial Intelligence intelligibility for subject matter experts | 2019 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Interval type-2 fuzzy logic based stacked autoencoder deep neural network for generating explainable AI models in workforce optimization | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 10 |

| Working with beliefs: AI transparency in the enterprise | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 19 |

| Total | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 18 | 46 | 74 | 467 | 454 | 1068 |

References

- Felzmann, H.; Fosch-Villaronga, E.; Lutz, C.; Tamò-Larrieux, A. Towards transparency by design for artificial intelligence. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2020, 26, 3333–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.; Hoffmann, A.L.; Stark, L. Better, Nicer, Clearer, Fairer: A Critical Assessment of the Movement for Ethical Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 2019, Maui, HI, USA, 8–11 January 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollanek, T. AI transparency: A matter of reconciling design with critique. Ai Soc. 2023, 38, 2071–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Rad, P. Opportunities and challenges in explainable artificial intelligence (xai): A survey. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.11371. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2006.11371 (accessed on 30 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chesterman, S. Through a glass, darkly: Artificial intelligence and the problem of opacity. Am. J. Comp. Law. 2021, 69, 271–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, D.; Baum, K.; Gros, T.P.; Wolf, V. XAI Requirements in Smart Production Processes: A Case Study. In World Conference on Explainable Artificial Intelligence; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Marzi, G.; Balzano, M.; Caputo, A.; Pellegrini, M.M. Guidelines for Bibliometric-Systematic Literature Reviews: 10 steps to combine analysis, synthesis and theory development. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2025, 27, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA 2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimized digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Dias, J.C. The New Digital Economy and Sustainability: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Raimundo, R. Sustainable Entrepreneurship Education: A Systematic Bibliometric Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Lopes, P.; Rosário, F.S. Sustainability and the Circular Economy Business Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchini, A.; Termine, A. Towards a taxonomy for the opacity of AI systems. In Conference on Philosophy and Theory of Artificial Intelligence; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Chamola, V.; Hassija, V.; Sulthana, A.R.; Ghosh, D.; Dhingra, D.; Sikdar, B. A Review of Trustworthy and Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). IEEE Access 2023, 11, 78994–79015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, R.; Singh, D. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) for the Prediction of Diabetes Management: An Ensemble Approach. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltiadou, D.; Perakis, K.; Sesana, M.; Calabresi, M.; Lampathaki, F.; Biliri, E. A novel Explainable Artificial Intelligence and secure Artificial Intelligence asset sharing platform for the manufacturing industry. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Engineering, Technology, and Innovation: Shaping the Future, ICE, Edinburgh, UK, 19–22 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Salloum, S.A. Trustworthiness of the AI. In Studies in Big Data; Springer Science and Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 144, pp. 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforidis, K.; Kyrtsoglou, A.; Vafeiadis, T.; Kotsiopoulos, T.; Nizamis, A.; Ioannidis, D.; Sarigiannidis, P. Enhancing transparency and trust in AI-powered manufacturing: A survey of explainable AI (XAI) applications in smart manufacturing in the era of industry 4.0/5.0. ICT Express 2025, 11, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgir Kabir, M.; Islam, M.M.M.; Chakraborty, N.R.; Noori, S.R.H. Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence for Industrial Operations and Manufacturing: Principles and Challenges; Springer Series in Advanced Manufacturing; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; Volume Part F138, pp. 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benguessoum, K.; Lourenço, R.; Bourel, V.; Kubler, S. Through the Lens of Explainability: Enhancing Trust in Remaining Useful Life Prognosis Models; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, P.; Obaidat, M.S.; Sanghavi, S.; Sakariya, V.; Tanwar, S.; Hsiao, K.F. Internet-of-Explainable-Digital-Twins: A Case Study of Versatile Corn Production Ecosystem. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Computing, Cybersecurity and Informatics, CCCI, Dalian, China, 17–19 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bonci, A.; Longhi, S.; Pirani, M. IEC 61499 Device Management Model through the lenses of RMAS. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 180, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, A.B.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Del Ser, J.; Bennetot, A.; Tabik, S.; Barbado, A.; Tabik, S.; Barbado, A.; Garcia, S.; Gil-Lopez, S.; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Inf. Fusion 2020, 58, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabé-Moreno, J.; Wildberger, K. A fuzzy linguistic supported framework to increase Artificial Intelligence intelligibility for subject matter experts. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 162, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousdekis, A.; Apostolou, D.; Mentzas, G. A human cyber physical system framework for operator 4.0—Artificial intelligence symbiosis. Manuf. Lett. 2020, 25, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Penica, M.; O’Connell, E.; Southern, M.; Hayes, M. Human-in-Loop: A Review of Smart Manufacturing Deployments. Systems 2023, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, L.K.; Khanna, M. Introduction to artificial intelligence and current trends. In Innovations in Artificial Intelligence and Human-Computer Interaction in the Digital Era; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 31–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.; Gajjar, Y. Evolution, Need, and Application of Explainable AI in Supply Chain Management. In Explainable AI and Blockchain for Secure and Agile Supply Chains: Enhancing Transparency, Traceability, and Accountability; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshaw, F.G.; Atyia, T.H.; Salleh, M.F.M.; Ishak, M.K.; Din, A.S. Utilizing Machine Learning and SHAP Values for Improved and Transparent Energy Usage Predictions. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 83, 3553–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, Z.; Chau, D.H.; Saldana, C. An Interrogative Survey of Explainable AI in Manufacturing. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 7069–7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, A.; Srinivasan, R.; Chelian, S.; Wang, J.; Uchino, K. Working with beliefs: AI transparency in the enterprise. In Proceedings of the IUI Workshops, Tokyo, Japan, 7–11 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bajpai, A.; Yadav, S.; Nagwani, N.K. An extensive bibliometric analysis of artificial intelligence techniques from 2013 to 2023. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, N.Y.; Nedeljkovic, D.; Jammal, M. AI-enabled IoT Applications: Towards a Transparent Governance Framework. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Global Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things, GCAIoT, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 10–11 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S.; Pal, D.; Meena, T. Explainable artificial intelligence to increase transparency for revolutionizing healthcare ecosystem and the road ahead. Netw. Model. Anal. Health Inform. Bioinform. 2024, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Vashisth, R.; Tripathi, S. Explainable Artificial Intelligence: A Study of Current State-of-the-Art Techniques for Making ML Models Interpretable and Transparent. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technological Advancements in Computational Sciences, ICTACS, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 1–3 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Votto, A.M.; Liu, C.Z. Transparent Artificial Intelligence and Human Resource Management: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Online, 3–7 January 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Woodbright, M.D.; Morshed, A.; Browne, M.; Ray, B.; Moore, S. Toward Transparent AI for Neurological Disorders: A Feature Extraction and Relevance Analysis Framework. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 37731–37743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, A. Pricing Risk: An XAI Analysis of Irish Car Insurance Premiums. In World Conference on Explainable Artificial Intelligence; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Kang, D. Artificial Intelligence and Smart Technologies in Safety Management: A Comprehensive Analysis Across Multiple Industries. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, P.; Menolotto, M.; Visentin, A.; O’Flynn, B.; Komaris, D.S. AI-Based Task Classification with Pressure Insoles for Occupational Safety. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 21347–21357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carloni, G.; Berti, A.; Colantonio, S. The role of causality in explainable artificial intelligence. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2025, 15, e70015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, S. Causal explanations and XAI. In Proceedings of the Conference on Causal Learning and Reasoning, Eureka, CA, USA, 11–13 April 2022; Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v177/beckers22a/beckers22a.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Warren, G.; Keane, M.T.; Byrne, R.M. Features of Explainability: How users understand counterfactual and causal explanations for categorical and continuous features in XAI. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.10152. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2204.10152 (accessed on 30 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Černevičienė, J.; Kabašinskas, A. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in finance: A systematic literature review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 8–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalicchio, E.; Gaudenzi, P.; Mancini, L.V. CriSEs: Cybersecurity for small-Satellite Ecosystem-state-of-the-art and open challenge. In Proceedings of the International Astronautical Congress, IAC, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 12–14 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Castelnovo, A.; Crupi, R.; Mombelli, N.; Nanino, G.; Regoli, D. Evaluative Item-Contrastive Explanations in Rankings. Cogn. Comput. 2024, 16, 3035–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andringa, J.; Baptista, M.L.; Santos, B.F. Counterfactual explanations for remaining useful life estimation within a Bayesian framework. Inf. Fusion. 2025, 118, 102972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, D.S.; Smith, J.; Mark, B.G.; Rauch, E. Information Model to Advance Explainable AI-Based Decision Support Systems in Manufacturing System Design. In International Symposium on Industrial Engineering and Automation; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmykov, V.L.; Kalmykov, L.V. Towards eXplicitly eXplainable Artificial Intelligence. Inf. Fusion. 2025, 123, 103352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, A.; Fernandes, M.; Canito, A.; Almeida, A.; Marreiros, G. Using an Explainable Machine Learning Approach to Minimize Opportunistic Maintenance Interventions. In International Conference on Practical Applications of Agents and Multi-Agent Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, J.S.; Chakraborty, A.; Mahmud, M.; Kar, U.; Lahby, M.; Saha, G. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) Based Analysis of Stress Among Tech Workers Amidst COVID-19 Pandemic. In Advanced AI and Internet of Health Things for Combating Pandemics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catti, P.; Bakopoulos, E.; Stipankov, A.; Cardona, N.; Nikolakis, N.; Alexopoulos, K. Human-Centric Proactive Quality Control in Industry 5.0: The Critical Role of Explainable AI. In Proceedings of the 30th ICE IEEE/ITMC Conference on Engineering, Technology, and Innovation: Digital Transformation on Engineering, Technology and Innovation, ICE, Funchal, Portugal, 24–28 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tronchin, L.; Cordelli, E.; Celsi, L.R.; MacCagnola, D.; Natale, M.; Soda, P.; Sicilia, R. Translating Image XAI to Multivariate Time Series. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 27484–27500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chochliouros, I.P.; Vardakas, J.; Ramantas, K.; Pollin, S.; Mayrargue, S.; Ksentini, A.; Nitzold, W.; Rahman, M.A.; O’Meara, J.; Chawla, A.; et al. 6G-BRICKS: Developing a Modern Experimentation Facility for Validation, Testing and Showcasing of 6G Breakthrough Technologies and Devices. In IFIP International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- González-Sendino, R.; Serrano, E.; Bajo, J.; Novais, P. A review of bias and fairness in artificial intelligence. Int. J. Interact. Multimed. Artif. Intell. 2024, 9, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, P.; MacAluso, I.; Marchetti, N.; Dasilva, L.A. Resource Reservation in Sliced Networks: An Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) Approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Communications, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 16–20 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Deck, L.; Schoeffer, J.; De-Arteaga, M.; Kuehl, N. A critical survey on fairness benefits of XAI. XAI in Action: Past, Present, and Future Applications. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.13007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanikou, V.; Karidi, D.P.; Pitoura, E.; Panagiotou, E.; Ntoutsi, E. Explanations as Bias Detectors: A Critical Study of Local Post-hoc XAI Methods for Fairness Exploration. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.00802. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2505.00802? (accessed on 30 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cummins, L.; Sommers, A.; Ramezani, S.B.; Mittal, S.; Jabour, J.; Seale, M.; Rahimi, S. Explainable Predictive Maintenance: A Survey of Current Methods, Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 57574–57602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewasiri, N.J.; Dharmarathna, D.G.; Choudhary, M. Leveraging artificial intelligence for enhanced risk management in banking: A systematic literature review. In Artificial Intelligence Enabled Management: An Emerging Economy Perspective; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2024; pp. 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyan Chakravarthi, M.; Pavan Kumar, Y.V.; Pradeep Reddy, G. Potential Technological Advancements in the Future of Process Control and Automation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Open Conference of Electrical, Electronic and Information Sciences, eStream, Vilnius, Lithuania, 25 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sivamohan, S.; Sridhar, S.S. An optimized model for network intrusion detection systems in industry 4.0 using XAI based Bi-LSTM framework. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 11459–11475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayanand Lal, N.; Adnan, M.M.; Sutha Merlin, J.; Ramyasree, K.; Palanivel, R. Intrusion Detection System using Improved Wild Horse Optimizer-Based DenseNet for Cognitive Cyber-Physical System in Industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Distributed Computing and Optimization Techniques, ICDCOT, Bengaluru, India, 15–16 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan, G.; Elango, E.; Soman, S.; Bai, S.C.P.A. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence and IoT for Healthcare 5.0: Use Cases, Applications, and Challenges. In Edge AI for Industry 5.0 and Healthcare 5.0 Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laux, J.; Wachter, S.; Mittelstadt, B. Trustworthy artificial intelligence and the European Union AI act: On the conflation of trustworthiness and acceptability of risk. Regul. Gov. 2024, 18, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikopoulou, Z.; Lavasa, E.; Perez-Castanos, S.; Monzo, D.; Moustakidis, S. Towards Explainable AI Validation in Industry 4.0: A Fuzzy Cognitive Map-based Evaluation Framework for Assessing Business Value. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Engineering, Technology, and Innovation: Shaping the Future, ICE, Edinburgh, UK, 19–22 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Moorthy, U.M.K.; Muthukumaran, A.M.J.; Kaliyaperumal, V.; Jayakumar, S.; Vijayaraghavan, K.A. Explainability and Regulatory Compliance in Healthcare: Bridging the Gap for Ethical XAI Implementation. Explain. Artif. Intell. Healthc. Ind. 2025, 521–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonani, R. Hybrid XAI Framework with Regulatory Alignment Metric for Adaptive Compliance Enforcement by Government in Financial Systems. Acad. Nexus J. 2024, 3. Available online: https://academianexusjournal.com/index.php/anj/article/view/20 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Puthanveettil Madathil, A.; Luo, X.; Liu, Q.; Walker, C.; Madarkar, R.; Qin, Y. A review of explainable artificial intelligence in smart manufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2025, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotriwala, A.; Kloepper, B.; Dix, M.; Gopalakrishnan, G.; Ziobro, D.; Potschka, A. XAI for operations in the process industry-Applications, theses, and research directions. In Proceedings of the AAAI Spring Symposium: Combining Machine Learning with Knowledge Engineering, Virtual Event, 22–24 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X.; Keane, M.T.; Shalloo, L.; Ruelle, E.; Byrne, R.M. Counterfactual explanations for prediction and diagnosis in XAI. In Proceedings of the 2022 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, Oxford, UK, 1–3 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, M.T.; Kenny, E.M.; Delaney, E.; Smyth, B. If only we had better counterfactual explanations: Five key deficits to rectify in the evaluation of counterfactual XAI techniques. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.01035. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2103.01035 (accessed on 30 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Keane, M.T.; Smyth, B. Good counterfactuals and where to find them: A case-based technique for generating counterfactuals for explainable AI (XAI). In Case-Based Reasoning Research and Development: 28th International Conference, ICCBR 2020, Salamanca, Spain, 8–12 June 2020, Proceedings 28; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2005.13997 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Bauer, K.; von Zahn, M.; Hinz, O. Expl(AI)ned: The Impact of Explainable Artificial Intelligence on Users’ Information Processing. Inf. Syst. Res. 2023, 34, 1582–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.M. Counterfactuals in explainable artificial intelligence (XAI): Evidence from human reasoning. In Proceedings of the 28th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Macao, China, 10–16 August 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccininni, M.; Konigorski, S.; Rohmann, J.L.; Kurth, T. Directed acyclic graphs and causal thinking in clinical risk prediction modeling. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fitzgibbon, B.; Garofolo, D.; Kota, A.; Papenhausen, E.; Mueller, K. An explainable AI approach to large language model assisted causal model auditing and development. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.16211. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2312.16211 (accessed on 30 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Arabikhan, F.; Gegov, A.; Taheri, R.; Akbari, N.; Bader-Ei-Den, M. Moving Towards Explainable Artificial Intelligence Using Fuzzy Rule-Based Networks in Decision-Making Process; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chimatapu, R.; Hagras, H.; Starkey, A.; Owusu, G. Interval type-2 fuzzy logic based stacked autoencoder deep neural network for generating explainable AI models in workforce optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 8–13 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Löhr, T. Identifying a Trial Population for Clinical Studies on Diabetes Drug Testing with Neural Networks; Lecture Notes in Informatics (LNI); Gesellschaft für Informatik (GI): Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fumanal-Idocin, J.; Andreu-Perez, J. Ex-Fuzzy: A library for symbolic explainable AI through fuzzy logic programming. Neurocomputing 2024, 599, 128048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Naqvi, M.R.; Elmhadhbi, L.; Sormaz, D.; Archimede, B.; Karray, M.H. CHAIKMAT 4.0—Commonsense Knowledge and Hybrid Artificial Intelligence for Trusted Flexible Manufacturing; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Morrison, M.; Miao, H.; Gu, F. Harnessing Deep Learning for Fault Detection in Industry 4.0: A Multimodal Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 6th International Conference on Cognitive Machine Intelligence (CogMI), Washington, DC, USA, 28–31 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wojak-Strzelecka, N.; Bobek, S.; Nalepa, G.J.; Stefanowski, J. Towards Differentiating Between Failures and Domain Shifts in Industrial Data Streams. In Proceedings of the CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Kyiv, Ukraine, 24–27 January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Baaj, I.; Poli, J.P. Natural language generation of explanations of fuzzy inference decisions. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ-IEEE), New Orleans, LA, USA, 23–26 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilevsky, M.; Qian, K.; Aharonov, R.; Katsis, Y.; Kawas, B.; Sen, P. A survey of the state of explainable AI for natural language processing. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.00711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Assady, M. Challenges and Opportunities in Text Generation Explainability. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.08468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, E.; Alonso, J.M.; Gatt, A. Towards harnessing natural language generation to explain black-box models. In 2nd Workshop on Interactive Natural Language Technology for Explainable Artificial Intelligence; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Narteni, S.; Orani, V.; Cambiaso, E.; Rucco, M.; Mongelli, M. On the Intersection of Explainable and Reliable AI for Physical Fatigue Prediction. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 76243–76260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chan, J.; Peko, G.; Sundaram, D. An explanation framework and method for AI-based text emotion analysis and visualisation. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 178, 114121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Maghsoudi, M. Bridging perspectives on artificial intelligence: A comparative analysis of hopes and concerns in developed and developing countries. AI Soc. 2025, 40, 5713–5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ding, Y.; Lei, Y.; Oliveira, F.J.M.S.; Neto, M.J.P.; Kong, M.S.M. Integrating artificial intelligence in industrial design: Evolution, applications, and future prospects. Int. J. Arts Technol. 2024, 15, 139–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Kaiser, M.S.; Shahadat Hossain, M.; Andersson, K. A Comparative Analysis of LIME and SHAP Interpreters with Explainable ML-Based Diabetes Predictions. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 37370–37388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazim, S.; Alam, M.M.; Rizvi, S.S.; Mustapha, J.C.; Hussain, S.S.; Suud, M.M. Advancing malware imagery classification with explainable deep learning: A state-of-the-art approach using SHAP, LIME and Grad-CAM. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narkhede, J. Comparative Evaluation of Post-Hoc Explainability Methods in AI: LIME, SHAP, and Grad-CAM. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Sustainable Expert Systems (ICSES), Kaski, Nepal, 15–17 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, K.; Nargund, N. Deep Learning in Industry 4.0: Transforming Manufacturing Through Data-Driven Innovation. In International Conference on Distributed Computing and Intelligent Technology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bhati, D.; Neha, F.; Amiruzzaman, M. A survey on explainable artificial intelligence (xai) techniques for visualizing deep learning models in medical imaging. J. Imaging 2024, 10, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldughayfiq, B.; Ashfaq, F.; Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Humayun, M. Explainable AI for retinoblastoma diagnosis: Interpreting deep learning models with LIME and SHAP. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Abuhmed, T.; El-Sappagh, S.; Muhammad, K.; Alonso-Moral, J.M.; Confalonieri, R.; Guidotti, R.; Del Ser, J.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Herrera, F. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): What we know and what is left to attain Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence. Inf. Fusion 2023, 99, 101805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, A.M.; Wang, Y. Are Linear Regression Models White Box and Interpretable? arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.12177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, C.; Chou, Y.L.; Hsieh, C.; Ouyang, C.; Pereira, J.; Jorge, J. Benchmarking instance-centric counterfactual algorithms for XAI: From white box to black box. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrashid, I.; Ahmad, I.S.; Musa, A.; Khalafalla, M. Impact of social media posts’ characteristics on movie performance prior to release: An explainable machine learning approach. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garouani, M.; Ahmad, A.; Bouneffa, M.; Hamlich, M.; Bourguin, G.; Lewandowski, A. Towards big industrial data mining through explainable automated machine learning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 120, 1169–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, D.; Pandolfo, L.; Pulina, L. A Systematic Literature Review of Supervised Machine Learning Techniques for Predictive Maintenance in Industry 4.0. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 102479–102504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqar, A. Intelligent decision support systems in construction engineering: An artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.; Agarwal, V. Barriers to adopting artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies in nuclear power. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2024, 175, 105295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köchert, K.; Friede, T.; Kunz, M.; Pang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Rantou, E. On the Application of Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML) in Late-Stage Clinical Development. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2024, 58, 1080–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Fernandez, V.; Camacho, D. Recent trends and advances in machine learning challenges and applications for industry 4.0. Expert Syst. 2024, 41, e13506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terziyan, V.; Vitko, O. Explainable AI for Industry 4.0: Semantic Representation of Deep Learning Models. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 200, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fase | Step | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Exploration | Step 1 | formulating the research problem |

| Step 2 | searching for appropriate literature | |

| Step 3 | critical appraisal of the selected studies | |

| Step 4 | data synthesis from individual sources | |

| Interpretation | Step 5 | reporting findings and recommendations |

| Communication | Step 6 | Presentation of the LRSB report |

| Database Scopus | Screening | Publications |

|---|---|---|

| Meta-search | Keyword: artificial intelligence | 689,969 |

| First Inclusion Criterion | Keyword: artificial intelligence, explainable AI | 5496 |

| Inclusion Criteria | Keyword: artificial intelligence, explainable AI, Industry | 467 |

| Keyword: artificial intelligence, explainable AI, Industry, Industry 4.0 | 45 | |

| Keyword: artificial intelligence, explainable AI, Industry, Industry 4.0, Industry 5.0 | 49 | |

| Keyword: artificial intelligence, explainable AI, Industry, Industry 4.0, Industry 5.0, Decision Making | 98 | |

| Screening | Keyword: artificial intelligence, explainable AI, Industry, Industry 4.0, Industry 5.0, Decision Making Until June 2025 | 98 |

| Country | Number of Publications |

|---|---|

| India | 66 |

| USA | 44 |

| UK | 33 |

| Italy | 32 |

| Greece | 31 |

| Germany | 28 |

| Ireland | 26 |

| France | 17 |

| Spain | 12 |

| Portugal | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rosário, A.T.; Dias, J.C. Illuminating Industry Evolution: Reframing Artificial Intelligence Through Transparent Machine Reasoning. Information 2025, 16, 1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121044

Rosário AT, Dias JC. Illuminating Industry Evolution: Reframing Artificial Intelligence Through Transparent Machine Reasoning. Information. 2025; 16(12):1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121044

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosário, Albérico Travassos, and Joana Carmo Dias. 2025. "Illuminating Industry Evolution: Reframing Artificial Intelligence Through Transparent Machine Reasoning" Information 16, no. 12: 1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121044

APA StyleRosário, A. T., & Dias, J. C. (2025). Illuminating Industry Evolution: Reframing Artificial Intelligence Through Transparent Machine Reasoning. Information, 16(12), 1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121044