Abstract

Video games have become one of the most influential digital entertainment platforms. They offer advertisers new opportunities through in-game placements. This study examines the relationship between the socio-demographic characteristics of gamers (gender, age, education and income) and the placement of video game advertising. Specifically, it analyses the relationship between these variables on five key dimensions: the type of video games played, the choice of gaming hardware, awareness of advertising placement, the type of advertising perceived and the level of involvement with the brands advertised. Despite the growing relevance of in-game advertising as a non-intrusive and immersive strategy, empirical evidence in this field remains scarce. A non-probability sampling survey was conducted with 317 respondents. Data were analysed using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), Student’s t-tests and ANOVA. The results reveal statistically significant differences by gender, age and education in the types of video games played. Awareness of advertising placement is higher among young people with secondary education. Involvement with the brand increases with age, especially among millennials. No significant differences were found in relation to income, except for the choice of hardware. These findings advance understanding of how socio-demographics shape gamer involvement with in-game advertising. The study provides both theoretical contributions and practical implications for developers, 3D designers and marketers.

1. Introduction

Video games have emerged as one of the largest entertainment industries worldwide. They attract audiences across all ages and genders, establishing themselves as a mainstream medium [1]. Ref. [2] proposes analysing video games as a distinct medium. They recommend examining video games separately from economic or sociological frameworks by focusing on their unique temporal, spatial, and narrative dimensions. Systematic academic research on video games as a communication medium began in the 1980s. At that time, the first advergames and adverworlds were integrated into arcade machines. Arcade machines are recreational video game devices with integrated computers, typically installed in public venues and operated by coins or tokens [1,3,4]. Root Beer Tapper by Budweiser, beer brand, (launched in 1984) is an early example of advergaming. Developed by Marvin Glass and Associates and released by Bally Midway, this game features gamers acting as bartenders serving customers their beers and collecting empty mugs and tips [5].

Since the 1980s, brands have turned to video game advertising to position themselves discreetly. This comes amid the saturation of traditional channels such as television and radio. Video game advertising has become a solid marketing strategy, especially since it attracts younger and mobile audiences. This trend is driven by widespread internet and smart device use [6]. One of the first empirical studies [7] found that placements not only facilitated brand memory but also enhanced the perceived realism of the gaming experience. The field has evolved, shifting from cognitive outcomes, such as memory, towards more complex psychological and experiential mechanisms. For example, refs. [6,8] argue that gamers develop psychological ownership of the game. They also state that attitudes towards in-game advertising depend on the gameful experience and the perceived intrusiveness of ads. In-game placements seamlessly integrate brand messages into the narrative flow of video games, thereby enhancing brand acceptance, awareness and gamer involvement [9,10,11]. As a result, video games have become a strategic advertising channel with increasing impact on consumer involvement [12].

Despite its growing relevance, few empirical studies have explored how socio-demographic characteristics shape the effectiveness of in-game advertising. This gap motivates the present study. The main objective of this study is to analyse the relationship between gamers’ socio-demographic profiles (age, gender, educational level and income) and five key dimensions: (1) type of video games played, (2) choice of gaming hardware, (3) awareness of brand placements, (4) type of placement perceived and (5) involvement with advertised brands. To this end, the study aims to provide empirical insights that advance the literature on in-game advertising awareness and gamer involvement in digital environments. Furthermore, the findings are expected to offer practical implications for developers, 3D designers, and marketers seeking to optimise strategies.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews scientific literature on video game genres, hardware usage, brand awareness, advertising placement and brand involvement. Section 3 details the methodology, which employs non-probabilistic convenience sampling and the snowball effect. Section 4 reports results from exploratory factor analysis, Student’s t-tests and ANOVA. Section 5 and Section 6 discuss the findings, present the main conclusions and propose directions for future research.

2. Review of the Literature

Table 1 presents a bibliographic summary that organises key findings on the role of sociodemographic variables in game genres, hardware preferences, advertising awareness, perceived advertising formats and brand involvement. However, the evidence remains fragmented, as much of it focuses on individual variables rather than integrated profiles. This table also highlights the research gaps addressed by this study.

Table 1.

Literature on sociodemographic variables and in-game advertising: key findings and research gaps. Source: own design.

2.1. Game Genres and Gamer Profiles

The genre of video games available today is vast and diverse. This phenomenon is due to the continuous growth and advancement of society, which gives rise to new lifestyles and behaviours, reflected and explored in video games. There is a functional classification of the most played titles into six major genre categories: (1) action, focused on combat and skill; (2) strategy, based on planning and resource management to achieve objectives; (3) puzzle, which includes puzzles and riddles; (4) disciplines and real-world simulations, which recreate physical world activities; (5) arcade, characterised by simple and fast gameplay, with easy-to-understand controls; and (6) exploration, focused on adventure and discovery of open worlds [13]. Preferences vary by player profile: casual gamers prioritise accessible, low-demand games for relaxation, whereas hardcore gamers prefer higher difficulty and longer sessions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Game genre categories. Source: own design.

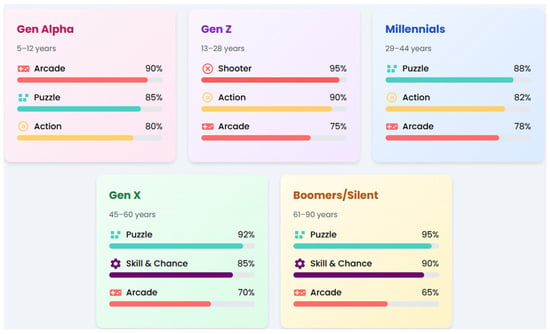

Recent systematic reviews have highlighted that the effectiveness of in-game advertising strategies is strongly influenced by gamer profiles, including age, motivations and gameplay preferences, with congruence between the game genre and the brand playing a crucial role. This suggests that socio-demographic variables not only influence the types of games gamers prefer, but also their responses to advertising within them [14,15]. Furthermore, ref. [16] reveals that video game genre preferences vary significantly by generation, identifying the following as the most played by each age group: Gen Alpha (5–12 years) prefers arcade, puzzle and action; Gen Z (13–28 years) goes for shooter, action and arcade; Millennials (29–44 years) prefer puzzle, action and arcade; Gen X (45–60 years) and Boomers/Silent (61–90 years) prioritise puzzle, skill & chance and arcade (Figure 2). In addition, ref. [17] observed that older adults show a clear preference for puzzle and strategy-type video games, especially those that are easy to learn, have challenging but straightforward mechanics and allow for short and accessible play sessions.

Figure 2.

Most played video game genres by age group data provided by [16]. Source: own design.

These choices are closely linked to individual and contextual variables that shape the gamer’s profile, including their needs, previous experiences and motivations. For example, ref. [18] demonstrated that apparent gender differences exist in video game participation and preference. In addition, ref. [19] found that gender moderated gamers’ attitudes toward in-game product placements, with male students showing more negative reactions than female students. Specifically, women, for example, tend to avoid highly competitive or violent genres, such as shooters or sports games, and prefer titles with minimal violence, such as real-life simulation games like The Sims or Animal Crossing. These differences are associated with psychological variables, such as lower competitive motivation, a lower need to win and lower self-efficacy in competitive game contexts. Consistently, refs. [20,21] show that men tend to prefer competitive, violent or strategy video games, such as shooters, fighting games, role-playing games or adventure games, while women tend to prefer genres more linked to casual entertainment, creativity or simulation, such as music and dance games, puzzle games, simulation games or educational games.

Similarly, ref. [22] demonstrates a relationship between educational level and the type of video game involvement. Building on this, ref. [23] have demonstrated a significant relationship between preferences for specific video game genres and the academic performance of university students who are gamers. According to [24], people with lower educational levels tend to exhibit motivations linked to competition or aggressiveness, leading them to favour genres, such as shooters or sports games. In addition, ref. [25] explains that those who study less frequently tend to choose video games focused on general entertainment, which have lower mechanical and cognitive demands. Furthermore, ref. [25] emphasises that the educational variable should be interpreted within the individual context of each gamer.

Ref. [26] found that the highest levels of education and income were observed among gamers in the sports and real-time strategy genres, while the lowest levels were found in gambling and platform games. Retired people mainly played games of chance and board games. Several studies indicate that belonging to a lower socioeconomic stratum is associated with a higher development of video game addiction and an increase in playing time, likely because these contexts have lower educational demands related to video game use [27]. Within this framework, the first hypotheses of the study are proposed:

H1.

(a–d) Type of video games played depends on the sociodemographic profile of the gamer (gender, age, education, income).

2.2. Gaming Hardware

In this sense, gameplay involves the active interaction of the gamer with the game through various electronic devices -whether through touch screens, hand controls or voice commands— which generates sensory responses (auditory and visual) that enrich the player’s experience and increase their level of immersion [28]. Video games can be played on various electronic devices, including computers (laptops and desktops), consoles, smartphones, tablets, smart TVs and virtual reality goggles. Each platform has important peculiarities to consider when designing and developing video games. Reference [29] states that the most used devices are smartphones (38%), consoles (30%), PCs (24%), tablets (17%) and laptops (11%). The latest reviews confirm that differences between platforms also influence how players view and process in-game advertising, suggesting that the type of hardware not only affects gameplay, but also the effectiveness of brand placement [15].

Moreover, studies have also shown that there are gender differences in the choice of gaming hardware. For example, it has been observed that women tend to use mobile devices more frequently for gaming, such as smartphones or tablets, due to their accessibility, portability and ease of use. In contrast, men tend to prefer consoles and PCs, which are associated with more technical, competitive, or immersive experiences [30,31,32,33]. These differences can be linked to both cultural factors and digital consumption habits. Ref. [16] states that 86% of men play on PC compared to 51% of women, 77% of women play on mobile while 55% of men do so, and finally, the console is used more by men (55%) than by women (38%).

Regarding gamer behaviour when using electronic devices, it should be considered that age has a significant impact on employment and preference for these devices. Older individuals often struggle with interfaces that require fine motor coordination or multitasking [33]. The groups most attuned to advanced or next-generation electronic devices are young people (especially Gen Z) [34]. Ref. [29] shows that there are apparent differences in the use of devices for playing video games by age group: Consoles are most popular among the younger age groups (73% of 6–10 year olds, a proportion that gradually declines to only 12% in the 45–64 age group), mobile devices and tablets from the age of 25 usage gradually drops to 20% in the 45–64 age group and the PC is especially popular among young adults (54% among 15–24 year olds), but usage drops significantly at the extremes of age, especially among those aged 44+ (12%).

Ref. [30] report that black and lower-income adolescents are more likely to use mobile phones as their primary gaming hardware, due to cost and accessibility. These findings are consistent with broader research on gaming platforms, which highlights how access to specific gaming devices is stratified by socio-economic factors and cultural contexts [35]. While direct evidence on in-game device choice by income is limited, broader ICT (Information and Communication Technologies) adoption research reveals a clear income–device stratification: lower-income groups rely more on mobile devices, whereas higher education and full-time employment predict broader hardware adoption [35,36,37]. Within this framework, the second hypotheses of the study are proposed:

H2.

(a–d) The choice of gaming hardware depends on the sociodemographic profile of the gamer (gender, age, education, income).

2.3. Awareness of Advertising Placement in Video Games

The primary function of advertising placement is to enhance brand awareness [5]. Awareness is crucial for purchase consideration because it reflects the extent to which consumers recognise and recall a brand. Effective placements strengthen recall—especially under repetition and emotionally congruent cues—thereby increasing purchase consideration [37]. Recent evidence also suggests that awareness is shaped by the platform on which advertisements are displayed. Ref. [11] demonstrated that users’ attention to advertisements on Instagram Stories was influenced by game involvement. This highlights the contextual nature of awareness.

Thus, a distinction can be made between high and low awareness: in high awareness, the consumer recognises the placement quickly and effortlessly, while low awareness requires more time and cognitive effort [38]. This distinction is particularly relevant among younger audiences, as ref. [8] found that understanding advertising intent moderated the relationship between recognition and problematic use of loot boxes.

Well-known and trusted brands are more likely to be considered in purchase decisions. Awareness plays a crucial role in purchase consideration, particularly in markets where there is no prior experience [39]. Recent evidence further suggests that gender moderates the relationship between awareness and attitudes towards in-game advertising. Male gamers tend to react more negatively to product placements than female gamers. Attitudes towards advertisements significantly predict purchase consideration [19]. Advertising placement is defined as the paid, non-intrusive inclusion of brands or products in audiovisual formats such as films, series, music videos, or social media platforms [5,40,41]. This technique fosters emotional connection, reinforces brand image and enhances recall in consumers’ memory [42,43]. The advertising placement is particularly relevant for users with no previous experience in purchasing that category of product or service [37,39]. On this basis, the third hypotheses of the study are proposed:

H3.

(a–d) The awareness of advertising placement in video games depends on the sociodemographic gamer’s profile (gender, age, education, income).

2.4. Types of Advertising Placements Perceived in Video Games

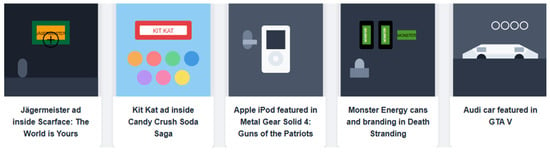

In the context of video games, there are several different degrees of brand integration, demonstrative, illustrative, associative, verbal, hyperactive, passive, static and dynamic [5,42,43,44]. Unlike other advertising formats, video game placements remain visible over time—unless included as Downloadable Content (DLC) [43]. Recent systematic reviews confirm that static formats often generate higher recall. Dynamic placements can increase involvement but may also be perceived as more intrusive, depending on the context [15]. For example, Figure 3 illustrates the options and locations available to advertisers for in-game advertising placements. It is worth noting that, in video games, it is not recommended to place a brand if there is no clear connection between the advertiser, the game’s narrative and the genre.

Figure 3.

Examples of options and locations of advertising placement available in video games. Source: own design.

Placements are more effective when there is congruence between the brand, the game narrative and the genre [19]. If the gamer is unaware of the advertised brand, they might think it is part of the props [45]. Similar effects have been observed in social media contexts. The effectiveness of ad formats in Instagram Stories depended on users’ game involvement, reinforcing that platform and format strongly mediate awareness and perception [11]. Recent findings suggest younger players are more receptive to dynamic, interactive formats, while older or less experienced gamers generally prefer static, less intrusive options. Gender also shapes acceptance, with women often responding more positively to subtle and congruent formats [19]. Overall, perceptions of ad formats are shaped by both technical and socio-demographic factors, supporting the following hypotheses:

H4.

(a–d) The types of advertising placements perceived depend on the sociodemographic profile of the gamer (gender, age, education, income).

2.5. Involvement with Brands Advertised in Video Games

The digital environment is characterised by a strong segmentation based on sociodemographic variables for advertising, a trend that is moving toward the hyper-personalisation of marketing [46]. Socio-demographic characteristics predict behavioural patterns and brand attitudes, directly shaping how advertising placements are perceived [47,48]. Several studies have shown that women, individuals with lower educational levels and those with lower incomes tend to exhibit more positive and receptive attitudes towards advertising placement, especially in digital entertainment contexts [49]. Generation Z (13–28 year olds) perceive advertising placement as a natural form of advertising communication, even preferring it to traditional advertising formats [50].

Recent research on advertising literacy among adolescents shows that as age increases, so does the ability to identify and critically question persuasive messages. Older adolescents show greater awareness of commercial intent and greater scepticism towards advertising than their younger peers [51]. Ref. [47] highlights that the placement of advertising in focal areas (close to the player’s field of vision) significantly improves adolescents’ recall, recognition and attitude towards the brand and the placed advertising strategy itself.

Involvement refers to the degree of perceived relevance of an object based on an individual’s inherent needs, values and interests [52,53]. Similarly, ref. [53] defines it as the degree to which consumers expect and recognise a branded product, based on attributes such as ease of use, quality, design, or functionality. For example, brand involvement is typically higher with luxury brands due to their symbolic and experiential value [54]. Moreover, a user’s level of involvement with a brand is conditioned by their awareness of it, which in turn is influenced by factors such as age, social context and socioeconomic status [47]. In the context of advertising placement in video games, the involvement of the brand in the game’s development is not as decisive as in the case of branded games [55]. Advergames—i.e., video games that incorporate advertising—can be classified according to the degree of involvement of the brand in their development and the relevance it acquires within the game environment [56].

Furthermore, recent research extends the concept of brand involvement to immersive and gamified environments. For instance, studies show that augmented and virtual reality technologies significantly improve brand recognition and emotional connection [57,58]. Building on this, gamification features such as immersion, achievement and social interaction further reinforce consumer involvement and foster brand loyalty [59,60]. Consistent with these observations, ref. [61] demonstrates that AR technologies, when applied in video games, enhance emotional and behavioural brand involvement. Taken together, these findings indicate that involvement with in-game advertising is multifaceted and shaped not only by technological contexts but also by socio-demographic factors, supporting the following hypotheses:

H5.

(a–d) The level of involvement with brands advertised in video games depends on the sociodemographic profile of the gamer (gender, age, education, income).

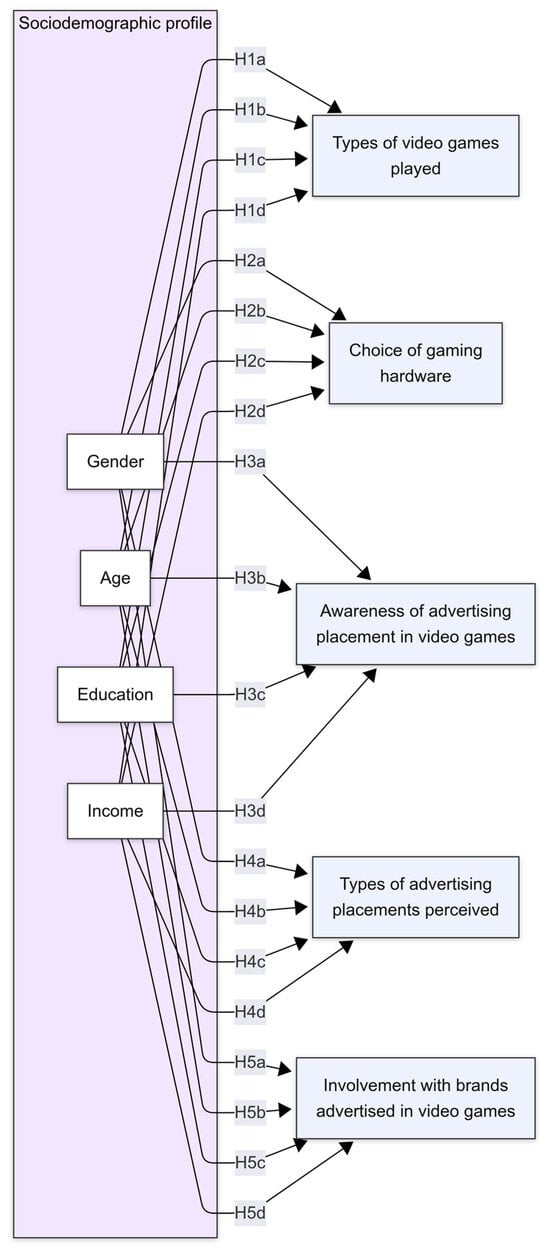

Figure 4 presents the conceptual framework of the study, which illustrates the hypothesised relationships between sociodemographic variables (gender, age, education and income) and five outcome constructs: types of video games played, choice of gaming hardware, awareness of advertising placement, types of advertising placements perceived and involvement with brands advertised in video games.

Figure 4.

Conceptual framework. Source: own design.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design, Participants and Procedure

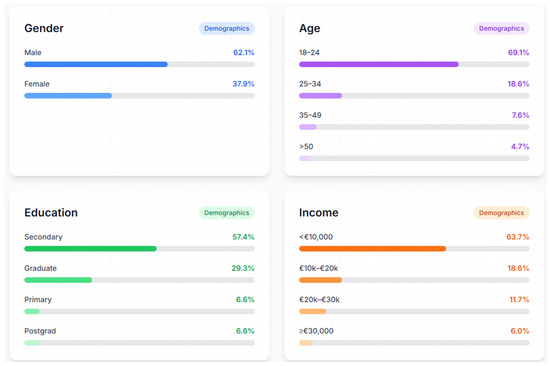

The research used a structured questionnaire conducted in Gran Canaria between March and April 2025 (Table 2). The initial population consisted of individuals with prior experience in video game consumption, specifically gamers residing in Spain during the data collection period. This sample provides useful exploratory evidence but cannot be generalised to all Spanish gamers. Only those over 18 years of age, regardless of their occupation, income, gender or degree of involvement with gaming, were included (Figure 5).

Table 2.

Technical sheet of the research. Source: own design.

Figure 5.

Sample profile. Source: own design.

The survey, available in Spanish, was administered in person by undergraduate students at the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (ULPGC) and by researchers. A non-probabilistic sampling method combining convenience and snowball techniques was used. Given the recruitment location (Gran Canaria) and non-probabilistic design, these findings should be interpreted as exploratory evidence rather than nationally representative data. All participants provided verbal informed consent, which was deemed sufficient given the minimal risk associated with the study and the anonymity of responses. No financial or material incentives were offered. The paper-and-pencil questionnaire was administered in various settings, including respondents’ homes, workplaces, educational institutions and social gatherings. Respondents were informed in advance about the study’s anonymity and told there were no right or wrong answers if they answered honestly. Screening questions ensured only respondents aged 18 or older with prior gaming experience were admitted. Participants first indicated their age and then answered a filter question (‘Have you ever played a video game? Yes/No’) to confirm their eligibility. Five invalid cases were excluded, yielding a final sample of 317 respondents.

3.2. Measures and Statistical Analysis

The instrument comprised three sections: (i) screening (age; ever played), (ii) in-game advertising blocks (genres and hardware; awareness, perceived placement types, brand involvement, purchase consideration, satisfaction, post-exposure behaviours), and (iii) sociodemographic (gender, age, education, nationality, income). All attitudinal items used 5-point Likert scales (1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree), with awareness and brand involvement items adapted from [52,61,62]. To ensure linguistic accuracy, the instrument was translated into Spanish and back-translated. Following this, a pilot test (n ≈ 5) assessed clarity and timing, leading to minor wording adjustments, removal of duplicate items and clarification of phrasing. Table 3 summarises the final items. For data analysis, IBM SPSS 28 was used. Specifically, we examined sociodemographic differences (gender, age cohorts, education, income) across five areas: (i) game genres, (ii) hardware choice, (iii) awareness, (iv) perceived placement types and (v) brand involvement. During the preliminary analyses, we verified that no cases had over 20% missing responses for key constructs. To validate construct structure, we used EFA, and applied ANOVAs and Student’s t-tests to evaluate group differences.

Table 3.

Summary of the items used in the questionnaire, excluding demographic data. Source: own design.

4. Results

The analysis involved two main types of data transformation prior to hypothesis testing. Specifically, we transformed the original values in two ways: standardisation and exploratory factor analysis. First, three variables related to gameplay (types of video games, gaming hardware and types of advertisements perceived) were grouped together by summing their original scores and then standardising them. As these variables had different ranges, we subsequently standardised their values (z-scores) to ensure comparability. Following this, two variables specifically associated with advertising in video games (awareness and involvement) were grouped for exploratory factor analysis (EFA), allowing us to reduce dimensionality and identify underlying constructs. After preparing these transformed variables, we proceeded to test the five sets of hypotheses using Student’s t-tests and ANOVA. The detailed statistical results are presented in the following sections.

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

Awareness refers to the extent to which consumers recognise and recall a brand integrated into a game environment. Table 4 displays the findings for the awareness scale. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.773, indicating solid internal consistency. The extracted factor explained 60.2% of variance, above the 50% threshold recommended for new or adapted scales. All items showed communalities above 0.47. The item with the highest communality (0.756) was ‘Brands integrated in video games attract my attention in a positive way,’ while the lowest (0.471) was ‘I have noticed the presence of real brands in the video games I play,’ indicating its lower contribution to the dimension. The results were satisfactory, confirming the adequacy of the correlation matrix. Overall, the results confirm the internal consistency of the scale and support its unidimensional structure for awareness of advertising placement.

Table 4.

Exploratory factor analysis of the statements about awareness.

Involvement is defined as the perceived relevance of a brand placement based on the gamer’s needs, values and interests. Table 5 presents the results for the involvement scale. The items showed communalities greater than 0.80, indicating adequate representativeness. The item with the highest communality (0.850) was related to ‘The use of branded characters increases my interest in the game,’ while the lowest (0.803) was related to ‘I find the placement of brands in video games interesting,’ reflecting its lower relative weight in the dimension. The values were adequate, confirming the adequacy of the correlation matrix. Overall, the results validate the internal consistency of the scale and its unidimensional structure.

Table 5.

Exploratory factor analysis of the involvement.

4.2. Main Analysis

4.2.1. Contrasting H1a–d: Type of Video Games Played Depends on the Sociodemographic Profile of the Gamer (Gender, Age, Education, Income)

The analysis reveals significant differences. First, gender shows a statistically significant difference (Table 6) in the mean number of video game genres played, with males reporting a mean of 0.1443 and females a mean of −0.2369. The Student’s t-test indicates a significant difference with a t-value of 3.345 (sig. < 0.001), confirming that males tend to play a greater variety of video game genres than females.

Table 6.

Student’s t-test difference in means: type of video games played depending on gender.

Secondly, in Table 7, age also shows significant differences, with the 18–24 age group being the most active, with a mean of 0.1245, followed by the 25–34 age group, with a mean of −0.1958, while the 35–49 age group shows a mean of −0.2478 and the 50+ age group shows the lowest mean of −0.6520. The ANOVA also confirms a significant difference (sig. < 0.003), indicating a progressive decrease in the variety of types of videogames played as age increases.

Table 7.

ANOVA analysis to test the difference in type of video games played depending on age.

In terms of educational level, significant differences were detected, as shown by ANOVA (F = 3.167, sig = 0.025), Table 8, with participants with secondary education obtaining the highest mean of 0.1397, followed by those with postgraduate studies (0.0036), primary education (−0.1826) and, finally, university studies (−0.2331). This result suggests that people with an average level of education exhibit a greater diversity in the types of video games they play. Finally, the income variable does not show statistically significant differences (F = 1.251, sig. = 0.291), although it is observed that participants with an income of less than 10,000 € per year have the highest mean (0.0716), without these differences being statistically significant. By contrast, income did not yield significant effects, suggesting that economic status does not systematically explain genre diversity in this sample.

Table 8.

ANOVA analysis to test the difference in type of video games played depending on education.

4.2.2. Contrasting H2a–d: The Choice of Gaming Hardware Depends on the Sociodemographic Profile of the Gamer (Gender, Age, Education, Income)

There is no statistically significant difference (sig.= 0.335) in the mean choice of gaming hardware based on gender: males report a mean of 0.0778, compared to females, whose mean is −0.1277. The Student’s t-test indicates no significant difference, with a t-value of 1.781. Moreover, in Table 9, age also shows significant differences, with the 18–24 age group being the most active, with a mean of 0.0977, followed by the 35–49 age group, with a mean of −0.0667, while the 25–34 age group shows a mean of −0.1801 and the 50+ age group shows the lowest mean of −0.6114. The ANOVA also confirms a significant difference (sig. < 0.020), indicating that age is a determinant in selecting gaming hardware.

Table 9.

ANOVA analysis to test the difference in choice of gaming hardware depending on age.

No significant differences were detected according to educational level, as shown by the ANOVA results (F = 0.149, sig = 0.931). Participants with secondary education reported the highest mean (0.0225), followed by those with university education (−0.0041) and postgraduate education (−0.6363); those with primary education showed the lowest mean (−0.1134). In addition, Table 10 shows statistically significant differences (sig. = 0.041); it is observed that participants with an income of >20,000 € per year have the highest mean (0.1140), followed by those with an income of <10,000 € (0.0831), which is also statistically significant. This result suggests that people with an average level of income have a wider range of choices in terms of devices.

Table 10.

ANOVA analysis to test the difference in choice of gaming hardware depending on income.

4.2.3. Contrasting H3a–d: The Awareness of Advertising Placement in Video Games Depends on the Sociodemographic Gamer’s Profile (Gender, Age, Education, Income)

There are statistically significant differences in the notoriety of video game advertising placement according to some socio-demographic variables. In relation to gender, men (−0.03751) have a higher average level of awareness than women (M = 4.591). Although this difference does not reach the threshold of statistical significance (sig.= 0.503). With respect to age, no significant difference is observed (F = 1.965, sig. = 0.119), with the 25–34 age group having the highest mean (M = 0.221), while those over 35 have the lowest means (M = −0.490), indicating that salience decreases with age. Also, the income variable shows no statistically significant differences (sig. = 0.498), although individuals with an income of >10,000 € have a slightly higher mean (M = 0.151). Regarding educational level, Table 11 shows significant differences (sig. = 0.022). People with primary (M = 0.421) and secondary (M = 0.074) education show a greater preference for devices compared to those with university (M = −0.227) or postgraduate (M = −0.050) education. This suggests that hardware preference decreases with increasing educational level.

Table 11.

ANOVA analysis to test the difference in awareness of advertising placement in videogames depending on education.

4.2.4. Contrasting H4a–d: The Types of Advertising Placements Perceived Depend on the Sociodemographic Profile of the Gamer (Gender, Age, Education, Income)

The results (Table 12) reveal that there are significant differences in the types of advertising placements perceived according to gender, as Student’s t-test shows a significant difference (sig. = 0.003), with males (0.11952) perceiving a greater variety of placement types than females (−0.19621). This difference, in addition to being statistically significant, has a notable magnitude in terms of mean, suggesting a wider or more diversified perception of the type of advertising placement among male players.

Table 12.

Student’s t-test difference in means: types of advertising placements perceived depending on gender.

In relation to educational level, no significant differences are found either (sig. = 0.190). Similarly, in terms of income level, the ANOVA reveals no significant differences (sig. = 0.188). In contrast, regarding age (Table 13), the ANOVA reveals significant differences (sig. = 0.002), gamers between 18 to 24 (0.08196) and 35 to 49 (−0.00999) show a higher perception of variety in advertising practices than those 50 or more (−0.093810), although this does not reach statistical significance.

Table 13.

ANOVA: types of advertising placements perceived depending on age.

4.2.5. Contrasting H5a–d: The Level of Involvement with Brands Advertised in Video Games Depends on the Sociodemographic Profile of the Gamer (Gender, Age, Education, Income)

Firstly, according to Student’s t-test, no significant differences were found between men and women in terms of brand involvement (sig. = 0.941), with nearly identical mean scores: 0.003 for men and −0.005 for women, indicating homogeneous levels of engagement across genders. Secondly, age appears to have a notable impact on involvement (sig. = 0.306). Participants aged 35–49 demonstrated the highest engagement (M = 0.291), followed by young adults aged 25–34 (M = 0.097). In contrast, the 18–24 (M = −0.064) and 50+ (M = −0.088) age groups exhibited lower levels of engagement. This suggests that individuals in middle adulthood show the strongest engagement with advertised brands, potentially due to a more developed emotional attachment to the medium. Regarding educational level, no significant differences were observed (sig. = 0.247). Finally, income did not significantly relate to brand involvement (sig. = 0.244).

Results show heterogeneous impacts of sociodemographic factors across outcomes. Specifically, the type of video games played is related to gender, age and educational level (H1a–H1c), but not to income (H1d). In terms of hardware choice, only age (H2b) and income (H2d) are significant; gender and education show no relation. Turning to advertising, awareness in video games is significantly associated with educational level (H3c), but not with gender, age or income. Regarding the types of advertising placements perceived, only gender (H4a) and age (H4b) show significant relationships. Finally, involvement with advertised brands shows no significant associations. These results highlight the differential role of sociodemographic variables on user profile characteristics (Table 14).

Table 14.

Hypotheses results. Source: own design.

5. Discussion

Game genre diversity is shaped by factors such as gender, age and educational background. Income shows no systematic effect. In agreement with [17,18], our data indicate that gender and age are determinants in the choice of video game genre. Similarly, refs. [23,24,25] highlighted educational level as an additional determinant. An original finding revealed that gamers with a high school education play a greater variety of games compared to those with a university education. Men play a greater variety of genres than women, but this does not mean women prefer different genres. The distinction is in the range (quantity), not the type (genre). Gender was reported by the original count of genres, while age and education results were expressed as group means in ANOVA. This ensures comparability but requires careful interpretation of differences in scale. In doing so, our findings challenge prior assumptions suggested by [20,21], who argued that adults prefer different genres, whereas our evidence indicates that the variation lies primarily in the breadth rather than the type of genres played. In line with this, younger individuals (18–24 years old) play a wider range of genres, while those aged 50 and over tend to play fewer. ANOVA confirmed a significant age effect with a moderate effect size. However, unlike [7], income showed no significant relationship, offering a new perspective by contradicting earlier assumptions of economic influence on game preferences.

Gaming hardware choices are primarily influenced by age and income, while gender and education have no significant effects. Consistent with prior research [34], the preference of 18–24-year-olds for specific devices highlights the generational dimension of hardware choice. Similarly, ref. [35] suggested a link between income and device use; our evidence reinforces this relationship by showing that players with incomes below 10,000 € rely on a wider range of hardware. Together, these results complement earlier studies [34,35], highlighting that hardware preferences are not only generational but also conditioned by economic constraints. This was supported by ANOVA results for both age and income, although post hoc tests did not reveal pairwise differences. By contrast, age and income results were reported in raw counts (i.e., number of devices used), facilitating interpretation in absolute terms.

Awareness of advertising placement is higher among younger and less-educated gamers, while gender and income have little effect. In contrast with [47], our results confirm that younger individuals and those with secondary education exhibit greater awareness of advertising placement. Moreover, young adults appear more inclined to engage in brand-related behaviours such as seeking further information or considering a purchase, as detailed by [63]. Those with primary/secondary education scored above the sample mean, extending the findings of [47] by specifying the age and education categories most associated with higher awareness. Moreover, gender appears to have a minor and inconsistent influence on advertising awareness, rather than a robust effect. These results challenge persistent gender stereotypes and support the development of more inclusive strategies as seen in [64]; for instance, aligning brand placements according to age—such as PEGI categories—rather than relying on gender-based assumptions. Moreover, YouTube, a common platform in the gaming industry for sharing, for example, gameplay content, continues to categorise products by gender, thereby reinforcing stereotypical patterns as noted in [65].

Perceptions of advertising placements differ by gender and age but not by education or income. For example, ref. [66] reported that male teen gamers exhibit significantly higher cognitive, affective and behavioural engagement compared to female gamers, a pattern that resonates with our findings. Specifically, the analysis showed that male gamers aged 18 to 24 reported a higher perception of in-game advertising placements than female gamers and those aged 50 or older, suggesting young men are more likely to notice and recognise diverse advertising in games. These findings suggest important implications for audience segmentation in the gaming industry. Our results highlight that Gen Z (1995–2012) are particularly engaged with a broader variety of video game genres. Growing up during the console boom of the 2000s, this generation may have developed a deeper bond with the medium, which could explain their higher levels of gaming engagement compared to older cohorts. As shown in [67], Gen Z not only spends more leisure time gaming than any other generation (7 h 20 min per week on average), but also engages with a wider variety of genres and platforms, supporting the idea that growing up during the console boom fostered a deeper and more diverse bond with video games compared to older cohorts. By contrast, education and income did not show significant effects, which is consistent with [68]’s and [69] findings that no significant differences exist in player perceptions of online advertising across these demographics.

Variables including age, income, education and gender were not significantly associated with the level of involvement with advertised brands in video games. This finding challenges the prevailing assumption that advertising involvement in video games primarily targets specific demographic groups, such as young people or millennials, as indicated by [47,63].

These findings indicate that sociodemographic factors shape multiple aspects of gamer behaviour, underscoring the need for tailored advertising strategies. They also contribute to the broader understanding of demographic influences on video game involvement. In agreement with [70], the results offer one of the first integrated perspectives on how sociodemographic factors selectively influence responses to advertising in video games, underscoring the importance of moving beyond one-size-fits-all approaches in both research and practice.

6. Conclusions

Sociodemographic variables play a crucial role in shaping gamer profiles and responses to in-game advertising. However, this area has received limited academic attention. This study demonstrates how these characteristics shape the effectiveness of in-game advertising across multiple dimensions. The findings refine the understanding of gamer behaviour. Results show a selective pattern: gender, age and education affect genre diversity. Age and income determine hardware choices. Age and education are predictive of awareness of advertising placements. Gender and age shape perceptions of placements. None of these variables significantly influences brand involvement.

From a practical perspective, the results provide actionable guidance for developers, designers and marketers. Advertising strategies can be tailored to specific gamer segments. For example, developers can increase awareness among younger and less-educated players. Collectively, these contributions strengthen both academic understanding and industry practice. They help to close the evidence gap concerning sociodemographics in in-game advertising.

Future research should expand to a broader range of games and sub-genres and include minors (6–17 years old) to examine developmental differences. Limitations of this study must be acknowledged: the convenience-plus-snowball sampling strategy within a single-island context constrains external validity; the sample size of 317 Spanish adults, while informative, is not fully representative; the absence of a lifespan design limits conclusions about changes across life stages; and reliance on self-reported measures introduces potential biases such as social desirability and recall effects. These issues underscore the need for complementary approaches in future research, including behavioural tracking, cross-cultural validation and the use of larger and more diverse samples. By directly addressing these limitations and employing more comprehensive methodologies, future studies can significantly advance understanding of socio-demographic influences on in-game advertising.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.-M. and G.D.-M.; methodology, M.A.-M. and G.D.-M.; validation, M.A.-M. and G.D.-M.; formal analysis, M.A.-M.; investigation, M.A.-M.; resources, M.A.-M.; data curation, M.A.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.-M.; writing—review and editing, M.A.-M. and G.D.-M.; visualization, M.A.-M. and G.D.-M.; supervision, G.D.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In accordance with Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (GDPR) and Organic Law 3/2018 on Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights, a truly anonymous survey—i.e., one that does not collect personal data or allow participants to be identified directly or indirectly—falls outside the scope of data protection regulations and therefore does not require specific authorisation or procedures in this area. On the other hand, within the Spanish ethical framework, the obligation to submit a study for review by a Research Ethics Committee (CEI/CEIm) focuses primarily on projects with biomedical implications, involving sensitive personal data or with potential risks for participants. Therefore, an anonymous survey of adults is not usually subject to such review, unless the institution promoting it imposes this requirement as a matter of internal policy.

Informed Consent Statement

Data were collected through an anonymous survey, and participants were clearly informed about the anonymity and purpose of the research. Specifically, the paper version of the survey included a brief explanatory text stating the academic nature of the study and guaranteeing full anonymity. Furthermore, when the survey was handed out, the anonymity and purpose of the research were reiterated verbally. Therefore, by voluntarily completing the questionnaire, all participants confirmed their informed consent under these conditions.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they are part of the author’s unpublished doctoral dissertation.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used Grammarly for the purposes of language proofreading. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Herrewijn, L.; Poels, K. Recall and recognition of brand placements in digital games: The effect of brand prominence and game repetition. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 231–243. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M.J.P. The Medium of the Video Game; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Belli, S.; López, C. Breve historia de los videojuegos. Athenea Digit. 2008, 14, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, B. Un análisis Del Advergaming Como Herramienta Publicitaria; Trabajo Fin de Grado; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sikus. Tapper. Museo del Videojuego. 2011. Available online: https://gamemuseum.es/tapper/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Mishra, S.; Malhotra, G. The gamification of in-game advertising: Examining the role of psychological ownership and advertisement intrusiveness. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 61, 102245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, M.R. Recall of brand placements in computer/video games. J. Advert. Res. 2002, 42, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cabrera, J.; Caba-Machado, V.; Feijóo, B.; Díaz-López, A.; Escortell, R.; Machimbarrena, J.M. The moderating effect of understanding advertising intent on the relation between advertising recognition and problematic use of loot boxes among minors: An exploratory study. Acta Psychol. 2024, 249, 104476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M. Cuando la marca ofrece entretenimiento: Aproximación al concepto de advertainment. Quest. Public. 2016, 11, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gispert, B. El Videojuego Crece Un 12% en España Impulsado Por la Modalidad Online. La Vanguardia, 29 May 2023. Available online: https://www.lavanguardia.com/economia/20230529/9001331/videojuego-crece-12-espana-impulsado-modalidad-online.html (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Huang, Y.-T.; Gong, A.-D. The role of game involvement on attention to ads: Exploring influencing factors of visual attention to game ads on Instagram Stories. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 2024, 3706590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliagas Ocaña, I. Análisis Neuropsicofisiológico de la Eficacia del Emplazamiento de Producto en Videojuegos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Valve Corporation. Steam. Available online: https://store.steampowered.com/?l=spanish (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Zagni, A.; Baima, G.; Do, Q.-A.; Nguyen, B. Convergence and divergence in digital game-based advertising. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 172, 114295. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, J.; De Pelsmacker, P. The impact of in-game advertising: A systematic review. J. Advert. 2022, 51, 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Entertainment Software Association. 2025 Essential Facts About the U.S. Video Game Industry. Available online: https://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/2025-Essential-Facts-Booklet-05-30-25-RGB.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Salmon, J.P.; Dolan, S.M.; Drake, R.S.; Wilson, G.C.; Klein, R.M.; Eskes, G.A. A survey of video game preferences in adults: Building better games for older adults. Entertain. Comput. 2017, 21, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, T.; Klimmt, C. Gender and computer games: Exploring females’ dislikes. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2006, 11, 910–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhan, C.E.; Özdemir, E. The effect of in-game product placement on attitude towards in-game advertisements and in-game purchase intention: A study on young consumers. Erciyes Üniv. İktisadi İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Derg. 2022, 61, 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, B.P.; Wühr, P.; Schwarz, S. Of time gals and mega men: Empirical findings on gender differences in digital game genre preferences and the accuracy of respective gender stereotypes. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 657430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, F.J.; Mezquita, L.; Griffiths, M.D.; Ortet, G.; Ibáñez, M.I. The role of personality on disordered gaming and game genre preferences in adolescence: Gender differences and person-environment transactions. Adicciones 2021, 33, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Männikkö, N.; Billieux, J.; Kääriäinen, M. Problematic digital gaming behavior and its relation to the psychological, social and physical health of Finnish adolescents and young adults. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prena, K.; Weaver, A.J. Grades on games: Gaming preferences and weekly studying on college GPAs. Game Stud. 2020, 23, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.Y. Four Studies on Video Game Genre Preferences: A Review of Four Studies Examining Preferences for Video Games and Video Game Genres. Game Developer. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230329191717/https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/four-studies-on-videogame-genre-preferences (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Martín-Rodríguez, I.; Pellejero Silva, M.; Ramos Montesdeoca, M.; Martín-Quintana, J.C.; Lomba Pérez, A. Relación entre tipologías de videojuego y variables del contexto educativo. In IX Jornadas Iberoamericanas de Innovación Educativa en el Ámbito de las TIC y las TAC; Universidad del Atlántico Medio y Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Las Palmas, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, L.; Golub, A.; Ream, G.; Dunlap, E. Video game genre as a predictor of problem use. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, L.; Abadie, P.; Herba, C.; Emond, M.; Gingras, M.P.; Amor, L.B. Video games in ADHD and non-ADHD children: Modalities of use and association with ADHD symptoms. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 632272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancán Lapo, M.; Sancán Lapo, B. Narrativa, mecánicas de videojuegos y animación como fortalezas interactivas para videojuegos en móviles. Rev. Politécnica 2023, 51, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación Española de Videojuegos. AEVI—Asociación Española de Videojuegos. Available online: https://www.aevi.org.es/web/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Lenhart, A.; Kahne, J.; Middaugh, E.; Macgill, A.R.; Evans, C.; Vitak, J. Teens’ Gaming Experiences Are Diverse and Include Significant Social Interaction and Civic Engagement. Pew Internet & American Life Project. 2008. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/media/Files/Reports/2008/PIP_Teens_Games_and_Civics_Report_FINAL.pdf.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Hassan, H.; Mailok, M.; Hashim, M. Gender and game genres differences in playing online games. J. ICT Educ. 2019, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Miguel, A.; Calderón Gómez, D. Videojuegos y jóvenes: Lugares, experiencias y tensiones. Zenodo 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.E.; Yoon, W.C. Age-and experience-related user behavior differences in the use of complicated electronic devices. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2008, 66, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuswandi, Y.; Musri, M.; Resiani, B.; Gustryanti, K. Association between duration of gadget use and social development in school-age children. Malahayati Int. J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2024, 7, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieborg, D.B.; Poell, T. The platformization of cultural production: Theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media Soc. 2020, 22, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noah, A.O.; David, O.O.; Osakwe, C.N. Electronic waste effects of ICT: Does income level matter? Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalova, M.; Constantinovits, M. Smart for development: Income level as the element of smartphone diffusion. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 10, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.J.G. El papel de la notoriedad de marca en las decisiones del consumidor. In Proceedings of the La gestión de la diversidad: XIII Congreso Nacional, IX Congreso Hispano-Francés, Universidad de La Rioja, Logroño, La Rioja, Spain, 16–18 June 1999; pp. 355–358. [Google Scholar]

- Bohara, S.; Bisht, V.; Suri, P.; Panwar, D.; Sharma, J. Online marketing and brand awareness for HEI: A review and bibliometric analysis. F1000Research 2024, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, W.D.; Brown, S.P. Effects of brand awareness on choice for a common, repeat-purchase product. J. Consum. Res. 1990, 17, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, V.; Sánchez, N.; Torrano, J. Actitud Hacia El Product Placement en Los Videojuegos Para Móviles. Anuario De Jóvenes Investigadores. 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277007061_Actitud_hacia_el_Product_Placement_en_los_videojuegos_para_moviles (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Rodríguez-Rey, R.; Cantero-García, M. Albert Bandura. Padres Y Maest./J. Parents Teach. 2020, 384, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, Z. Contenidos Digitales Y Publicidad Emocional: Nuevas Formas de Comunicación Entre Marcas Y Usuarios. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Seoane Nolasco, A.; San Juan Pérez, A.; Martínez Costa, S. Visibilidad y recuerdo del product placement en videojuegos. AdComunica. Rev. Científica De Estrateg. Tend. E Innovación En Comun. 2015, 9, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, J.; Currás, R.; Sánchez, I. Nuevas fórmulas publicitarias: Los advergames como herramienta de las comunicaciones de marketin. Cuad. De Gestión 2012, 12, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- García, G. Marketing y videojuegos: Product placement, in-game advertising y advergaming reseña por Enrique García Pérez. Quest. Public. 2010, 1, 155–158. Available online: https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/quepub/quepub_a2010n15/quepub_a2010n15p155.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Feijoo, B.; Sádaba, C. Publicidad a medida. Impacto de las variables sociodemográficas en los contenidos comerciales que los menores reciben en el móvil. Index Comun. 2022, 12, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, N.A. Realidad Virtual, videojuegos y publicidad in-game: Un estudio experimental en el colectivo adolescente con implicaciones empresariales para la industria del entretenimiento. Prism. Soc. Rev. De Investig. Soc. 2021, 34, 106–123. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, Z.; Wu, X.; Chen, C.; Nak-Hwan, C. What makes female players pay for female mobile games? SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241265322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insight Trends. Insight of the Day: How Gen Z Thinks Brands Should Show up in Video Games. Insight Trends. 2023. Available online: https://www.insighttrendsworld.com/post/insight-of-the-day-how-gen-z-thinks-brands-should-show-up-in-video-games (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Popovic Sevic, N.; Ilić, M.P.; Sevic, A. The impact of advertising messages on school children through age, branded products and trust. Res. Pedagog. 2022, 12, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the involvement construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.-L.; Chao, C.-M.; Lin, C.-H. Impact of social media marketing activities and ESG green brand involvement on green product repurchase [Preprint]. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Činjarević, M.; Alić, A.; Hašimović, N. Can you feel the luxe? exploring consumer-brand relationships with luxury and neo-luxury brands. South East Eur. J. Econ. Bus. 2025, 20, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristancho-Triana, G.J.; Cardozo-Morales, Y.C.; Camacho-Gómez, A.S. Tipos de centennials en la red social TikTok y su percepción hacia la publicidad. Revista CEA 2022, 8, e1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, E.P. Advergames: Tipología y elementos narrativos del videojuego en la publicidad. Rev. Alea Jacta Est 2019, 1, 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Maheswari, S.; Balakrishnan, J. Immersive marketing: The impact of augmented and virtual reality technologies on brand recognition and emotional involvement. J. Mark. Futures 2025, 3, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Tunnufus, A.; Rahman, M.; Iskandar, D. The impact of augmented reality on consumer involvement and brand loyalty. J. Media Futur. 2024, 14, 112–128. [Google Scholar]

- Shoubashy, H. Empirical study on gamification effect on brand involvement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6542. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. How gamification features drive brand loyalty: The roles of immersion, achievement, and social interaction. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.B.; Gould, S.J. Consumers’ perceptions of the ethics and acceptability of product placements in movies: Product category and individual differences. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 1997, 19, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.A. Investigating the effectiveness of product placements in television shows: The role of modality and plot connection congruence on brand memory and attitude. J. Consum. Res. 2002, 29, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adıgüzel, S. The effect of in-game advertising as a marketing technique on the purchasing behavior of generation z in turkey. Airlangga Int. J. Islam. Econ. Financ. 2024, 7, 133–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Torre-Sierra, A.M.; Guichot-Reina, V. Women in video games: An analysis of the biased representation of female characters in current video games. Sex. Cult. 2025, 29, 532–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consell de l’Audiovisual de Catalunya. Representation of Gender Stereotypes in Toy and Game Advertising (Linear Television and Video-Sharing Platforms) During the Christmas Campaign 2019–2020; Report 5/2020; Consell de l’Audiovisual de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sedek Abdul Jamak, A.B.; Abbasi, A.Z.; Fayyaz, M.S. Gender differences and consumer videogame engagement. SHS Web Conf. 2018, 56, 01002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newzoo. How Different Generations Engage with Games: Newzoo’s Generations Report 2021. Strive Sponsorship. 2021. Available online: https://strivesponsorship.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/How-Different-Generations-Engage-with-Games-Report.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Amra & Elma. Nostalgia Marketing Statistics: How Nostalgia Drives Brand Engagement. Amra & Elma. 2023. Available online: https://www.amraandelma.com/nostalgia-marketing-statistics/ (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Lewis, B. Measuring Player Perceptions of Advertising in Online Games. Master’s Thesis, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2006. Available online: https://repository.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/793 (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Çadırcı, T.O.; Güngör, A.S. Segmenting the gamers to understand the effectiveness of in-game advertisement. In Proceedings of the 1st Annual International Conference on Social Sciences (AICSS), Istanbul, Turkey, 21–23 May 2015; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/278025126_Segmenting_the_Gamers_to_Understand_the_Effectiveness_of_In_Game_Advertisement (accessed on 4 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).